The crystal structure of a soluble family I inorganic pyrophosphatase from L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 was determined to a resolution of 2.0 Å. Inorganic pyrophosphatases play a central role in regulating cellular pyrophosphate concentration, which is important for many biosynthetic pathways. L. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 causes a rare but severe respiratory infection known as Legionnaires’ disease.

Keywords: structural genomics, inorganic pyrophosphatases, Legionella pneumophila, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, SSGCID, Legionnaires’ disease

Abstract

Inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) is generated as an intermediate or byproduct of many fundamental metabolic pathways, including DNA/RNA synthesis. The intracellular concentration of PPi must be regulated as buildup can inhibit many critical cellular processes. Inorganic pyrophosphatases (PPases) hydrolyze PPi into two orthophosphates (Pi), preventing the toxic accumulation of the PPi byproduct in cells and making Pi available for use in biosynthetic pathways. Here, the crystal structure of a family I inorganic pyrophosphatase from Legionella pneumophila is reported at 2.0 Å resolution. L. pneumophila PPase (LpPPase) adopts a homohexameric assembly and shares the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB) β-barrel core fold common to many other bacterial family I PPases. LpPPase demonstrated hydrolytic activity against a general substrate, with Mg2+ being the preferred metal cofactor for catalysis. Legionnaires’ disease is a severe respiratory infection caused primarily by L. pneumophila, and thus increased characterization of the L. pneumophila proteome is of interest.

1. Introduction

Legionella are Gram-negative, aerobic bacteria that naturally inhabit freshwater environments but can sometimes be found in manmade water systems including large plumbing systems, hot water tanks, hot tubs, fountains, showerheads and faucets (Muder & Yu, 2002 ▸; Newton et al., 2010 ▸; Winn, 1996 ▸). When Legionella are present in a water system, aerosolized bacteria-containing droplets can infect exposed individuals when inhaled (Winn, 1996 ▸). Although more than 25 species of Legionella can cause human infection, L. pneumophila causes ∼90% of cases (Muder & Yu, 2002 ▸).

L. pneumophilia is a human opportunistic pathogen that is the major causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease (Muder & Yu, 2002 ▸; Newton et al., 2010 ▸; Winn, 1996 ▸). First identified after an outbreak at a 1977 American Legion convention in Philadelphia, Legionnaires’ disease is a severe form of pneumonia with symptoms including cough, shortness of breath, muscle ache, headache and fever (Chien et al., 2004 ▸; Muder & Yu, 2002 ▸; Winn, 1996 ▸). Most infections due to Legionella species manifest as pneumonia; however, exposure can also cause Pontiac fever, a milder form of infection characterized by fever and muscle aches similar to Legionnaires’ disease without pneumonia (Muder & Yu, 2002 ▸; Newton et al., 2010 ▸; Pang et al., 2016 ▸). In rare cases, extrapulmonary infections such as pericarditis or endocarditis are observed (Winn, 1996 ▸). In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control reported over 10 000 cases of Legionnaires’ disease, although the disease is likely to be underdiagnosed and underreported (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022 ▸).

While most cases of Legionnaires’ disease can successfully be treated with antibiotics, infections can be fatal for immunocompromised patients or those with pre-existing respiratory conditions (Newton et al., 2010 ▸; Winn, 1996 ▸). Targeting basic metabolic pathways is an attractive alternative for antimicrobial drug development; for example, inhibiting iron-uptake pathways is being explored as it is essential for many bacterial pathogens including Legionella (Cianciotto, 2015 ▸). Roughly 20% of the L. pneumophilia genome encodes metabolic proteins; however, most have not yet been characterized (Chien et al., 2004 ▸). One key metabolic process is regulation of the cellular concentration of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi), which is largely maintained by the enzyme inorganic pyrophosphatase (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸).

Inorganic pyrophosphatases (PPases; EC 3.6.1.1) catalyze the metal-dependent hydrolysis of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) into two orthophosphates (Pi) (KEGG reaction R00004),

PPi is generated as an intermediate or byproduct in many fundamental metabolic pathways, including DNA/RNA synthesis and protein synthesis (Farquharson, 2018 ▸; Heinonen, 2001 ▸). PPases are critical for regulating the intracellular PPi concentration, as PPi levels influence the intracellular equilibria of essential cellular reactions and the accumulation of PPi can also be toxic to cells (Farquharson, 2018 ▸; Heinonen, 2001 ▸; Newton et al., 2010 ▸). PPases are also known to play a role in cell growth and maintenance, and previous studies have correlated PPase inhibition with inhibited cell growth (Winn, 1996 ▸).

Four nonhomologous families of PPases exist: integral membrane H+/Na+-pumping PPases (M-PPases) and three soluble families (I, II and III) (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). Family I PPases are found in all three domains of life, with eukaryotic family I PPases forming homodimers, while archaeal and bacterial family I PPases are typically homohexameric (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). Other structural differences have been observed; for example, eukaryotic family I PPases are often larger by ∼100 amino acids (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸; Liu et al., 2004 ▸).

Family I PPases share a conserved active site composed of 14–16 amino-acid residues where, in addition to the PPi substrate, four four divalent cations are bound (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). The metal cofactors, most often Mg2+, play a central role in catalysis of the hydrolysis reaction through the stabilization of PPi and the coordination of a nucleophilic water molecule (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). Inhibition of family I PPases by fluoride ions has been demonstrated through interference of water coordination in the active site (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). The competing interaction between the fluoride ion and the divalent metal is stronger than that between the water and the metal, inhibiting hydrolysis by blocking the water from entering the active site (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸; Wu et al., 2021 ▸).

The majority of L. pneumophila infections which lead to Legionnaires’ disease are caused by serogroup 1, the original 1976 Philadelphia 1 strain isolate (Chien et al., 2004 ▸; Zhang et al., 2014 ▸). Only 7% of the proteome of the Philadelphia 1 strain has been structurally characterized in the Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000 ▸). Further characterization of Legionella proteomes may aid in the development of novel therapies. Here, we present the crystal structure of a family I inorganic pyrophosphatase from L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila strain Philadelphia 1 (serogroup 1) (LpPPase) at 2.0 Å resolution, which was solved as part of structural genomic studies at the Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease (SSGCID). In addition, LpPPase demonstrated the expected enzymatic activity in the presence of Mg2+.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

Inorganic pyrophosphatase from L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila Philadelphia 1 (serogroup 1) (LpPPase) was cloned, purified and crystallized by the Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Diseases (SSGCID; Myler et al., 2009 ▸; Stacy et al., 2011 ▸) as described previously (Rodarte et al., 2021 ▸). Briefly, the 178-residue sequence (UniProt ID Q5ZRW2, GenBank ID WP_061467506.1) was cloned into the pBG1861 vector to produce a construct with a noncleavable 6×His tag (Table 1 ▸) and was then transformed into Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) cells and auto-induced (Bryan et al., 2011 ▸; Choi et al., 2011 ▸). The pellet was lysed using BugBuster Master Mix and purification was accomplished via Ni2+-affinity chromatography (HisTrap FF, Cytiva) followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC; HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column, Cytiva) in SEC buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP). Purified LpPPase was concentrated to 42.55 mg ml−1 and flash-frozen. The purified protein and/or the clone can be obtained at https://targetstatus.ssgcid.org/Target/LepnA.00023.a.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | Legionella pneumophila subsp. pneumophila (strain Philadelphia 1/ATCC 33152/DSM 7513) |

| DNA source | NCBI txid66976 |

| Cloning vector | pBG1861 |

| Expression vector | pBG1861 |

| Expression host | E. coli Rosetta (DE3) |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced | MAHHHHHHMSLMEIQSGRDVPNEVNVIIEIPMHGEPVKYEVDKKTGALFVDRFMTTAMFYPTNYGYIPNTLSEDGDPVDVLVITPVPLISGAVISCRAVGMLKMTDESGVDAKILAVPTTKLSKMYQSMQTYQDIPQHLLLSIEHFFKHYKDLEEGKWVKVEGWVGPDAAREEITSSINRYNHTKK |

Purified LpPPase was acquired from the SSGCID and run over an SEC column (HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg; Cytiva) at two concentrations: 0.5 and 7.0 mg ml−1. A calibration curve for the SEC column was generated separately using a Gel Filtration HMW Calibration Kit (Cytiva) to verify the native migration size as described previously (Rodarte et al., 2021 ▸). The calibration curve was obtained by plotting the partition coefficient (K av), which was calculated using individual elution volumes (V e), versus the log relative molecular weight (M r) of the known protein standards in the kit.

2.2. Crystallization and data collection

Purified LpPPase was crystallized at 21.3 mg ml−1 by a previously described standardized SSGCID approach using a sparse-matrix screen (Subramanian et al., 2011 ▸). Briefly, equal amounts of protein solution and well solution were mixed to form 0.8 µl drops. Drops were equilibrated using vapor diffusion against 100 µl reservoir solution in 96-well Compact Jr crystallization plates (Emerald BioSystems). Single crystals were obtained in sitting drops at 285 K using Molecular Dimensions Morpheus Screen condition H12: 12.5% PEG 1000, 12.5% PEG 3350, 12.5% MPD, 20 mM sodium l-glutamate, 20 mM dl-alanine, 20 mM glycine, 20 mM dl-lysine·HCl, 20 mM dl-serine, 100 mM Bicine and 100 mM Trizma pH 8.5. The crystals did not need additional cryoprotection and were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Crystallization details are summarized in Table 2 ▸. A 2.0 Å resolution data set was collected on a Rigaku FR-E+ SuperBright rotating-anode generator at 100 K using a wavelength of 1.5418 Å. Diffraction data were processed with XDS/XSCALE (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). Data-collection details are summarized in Table 3 ▸.

Table 2. Crystallization.

| Method | Vapor diffusion, sitting drop |

| Temperature (K) | 285 |

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 21.3 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM TCEP |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 12.5% PEG 1000, 12.5% PEG 3350, 12.5% MPD, 20 mM sodium L-glutamate, 20 mM DL-alanine, 20 mM glycine, 20 mM DL-lysine·HCl, 20 mM DL-serine, 100 mM Bicine, 100 mM Trizma base pH 8.5 |

| Volume ratio of drop | 1:1 |

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 80 |

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

| Diffraction source | Rigaku FR-E+ SuperBright rotating anode |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | Rigaku Saturn 944+ CCD |

| Space group | P21 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 64.1, 119.9, 74.9 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 109.59, 90 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 40.97–2.00 (2.05–2.00) |

| No. of unique reflections | 71646 (7137) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (99.9) |

| Multiplicity | 6.02 (3.99) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 19.3 (2.25) |

| R r.i.m. | 0.053 (0.71) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.785) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 43.6 |

2.3. Structure solution and refinement

The initial model was generated via molecular replacement with MoRDa in CCP4 (Agirre et al., 2023 ▸; Vagin & Lebedev, 2015 ▸) using PDB entry 4xel (Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, unpublished work) as the search model. The structure was further built in CCP4 (Agirre et al., 2023 ▸) with Buccaneer (Cowtan, 2006 ▸, 2012 ▸) and ARP/wARP (Langer et al., 2008 ▸). Iterative refinement and model building were then completed with Phenix (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸) and Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸; Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▸), respectively. The crystal structure was deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession number 6n1c. Final refinement statistics are provided in Table 4 ▸. All molecular graphics were created with UCSF ChimeraX (Pettersen et al., 2021 ▸).

Table 4. Structure refinement.

| Resolution range (Å) | 40.97–2.00 (2.05–2.00) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 |

| σ Cutoff | F > 1.340σ(F) |

| No. of reflections, working set | 71619 (4956) |

| No. of reflections, test set | 1980 (123) |

| Final R cryst | 0.193 (0.260) |

| Final R free | 0.232 (0.299) |

| No. of non-H atoms | |

| Protein | 7923 |

| Ion | 4 |

| Ligand | 68 |

| Water | 480 |

| Total | 8386 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 |

| Angles (°) | 0.880 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 49.0 |

| Ion | 57.3 |

| Ligand | 59.5 |

| Water | 46.8 |

| Clashscore | 3.06 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored (%) | 98.33 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.57 |

2.4. Enzyme-activity assay

The reaction mixture for the determination of enzyme activity consisted of 1 µM LpPPase, 200 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2, 1 mM MgCl2 and substrate (pNPP) in a 1 ml volume. The p-nitrophenol phosphate (pNPP) substrate concentration was varied from 2 to 200 mM. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm in cuvettes using a Genesys 10 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) over 30 s. A molar absorptivity of 16.2 µmol−1 cm−1 ml−1 was used to determine the amount of p-nitrophenol produced following hydrolysis of the phosphate group (Roberts & Chlebowski, 1985 ▸). The reaction velocities calculated from the A 405 were plotted against the pNPP concentration and the resulting curve was fitted to obtain Michaelis–Menten parameters in GraphPad Prism version 9.5.1. The effect of metal cofactors on enzyme activity was determined using 160 mM pNPP in the same reaction conditions and substituting MgCl2 with either ZnCl2, CoCl2, CaCl2 or MnCl2. Fluoride-ion inhibition was investigated by adding 0.6 mM sodium fluoride to the reaction conditions with Mg2+ as the metal cofactor. Reactions were performed in duplicate at room temperature. Blank readings were determined by substituting SEC buffer for the enzyme.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural overview

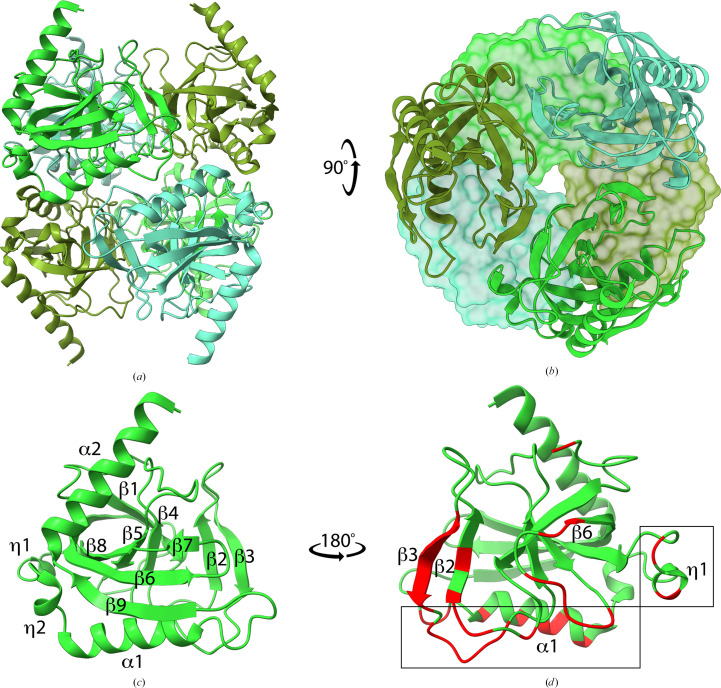

L. pneumophila inorganic pyrophosphatase (LpPPase) adopts the characteristic fold and oligomeric structure of many soluble family I inorganic pyrophosphatases. Bacterial family I inorganic pyrophosphatases are known to have homohexameric assemblies of dimers of trimers, which is what is seen in the asymmetric unit of LpPPase (Figs. 1 ▸ a and 1 ▸ b; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). PDBePISA supports the hexameric assembly of LpPPase, with a total buried surface area of 15 800 Å2 (Krissinel & Henrick, 2004 ▸). The LpPPase monomer adopts a conserved five-stranded oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding (OB) fold β-barrel, which contains the active site (Fig. 1 ▸ c; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). The overall monomer fold contains nine β-sheets, two α-helices and two 310-helices (Figs. 1 ▸ c and 2 ▸ a), although β7 and β8 are fused in two of the monomers.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of L. pneumophila PPase (LpPPase). (a) The homohexameric structure of LpPPase, which is a dimer of trimers, is shown. Individual monomers of the upper and lower trimer are colored in three different shades of green. All subunits are shown as ribbons. (b) One trimer is shown in surface representation, while the other is shown as ribbons. Individual subunits colored as in (a) demonstrating symmetry. (c) Representative monomer of LpPPase annotated with secondary-structure elements including β-sheets (β), α-helices (α) and 310-helices (η). (d) Secondary-structure elements involved in the quaternary-structure interfaces for each monomer are colored red and labeled, with the trimer–trimer interface boxed.

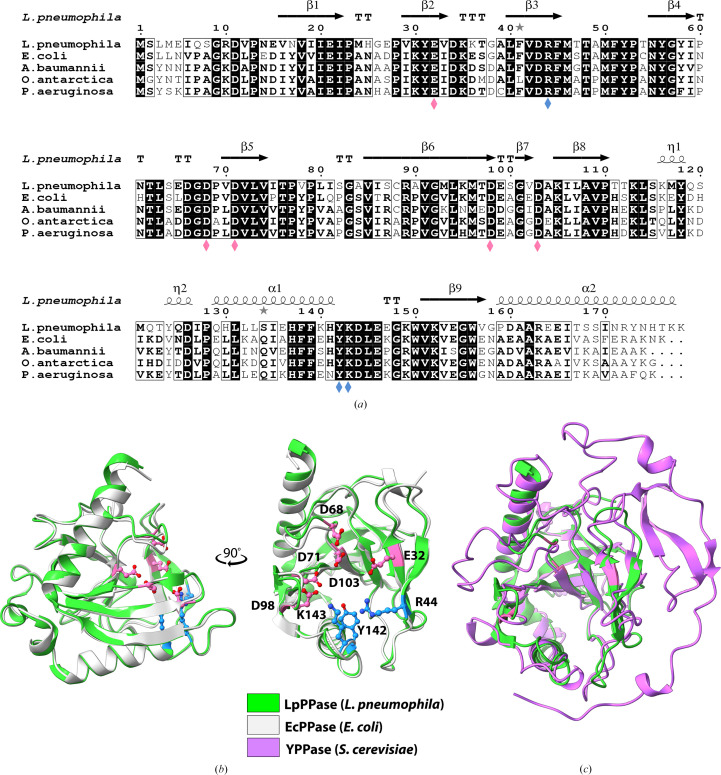

Figure 2.

Sequence and structural alignments of LpPPase. (a) Primary-sequence alignment of L. pneumophila PPase (LpPPase; PDB entry 6n1c) with PPases from A. baumannii (PDB entry 6k21), E. coli (PDB entry 1obw), O. antarctica (PDB entry 3i4q) and P. aeruginosa (PDB entry 4xel). Secondary-structure elements of LpPPase are shown: β-sheets (β), α-helices (α), 310-helices (η), β-turns (TT) and α-turns (TTT). Identical residues are shown in white on a black background, while conserved residues are shown in bold and related residues are boxed. Pink diamonds indicate catalytically significant residues and blue diamonds indicate residues that bind the substrate. (b) LpPPase (green) aligned with EcPPase from E. coli (gray; PDB entry 1obw). Labeled residues shown as sticks are important for catalysis (pink) or for substrate binding (blue), corresponding to the diamonds in (a). (c) LpPPase (green) aligned with YPPase from S. cerevisiae (purple; PDB entry 1e6a), a eukaryotic family I PPase.

LpPPase crystallized with six monomers in the asymmetric unit arranged as one hexameric unit (Figs. 1 ▸ a and 1 ▸ b). This hexameric arrangement adopted by prokaryotic family I inorganic pyrophosphatases is a dimer of trimers, as first described in the structure of E. coli PPase (EcPPase; Kankare et al., 1996 ▸). The r.m.s.d. between individual LpPPase monomer subunits was ∼0.268 Å or lower. Every monomer directly contacts three others, two from its trimer and one from the opposite trimer, burying at least 300 Å2 at each interface, which involves β2, β3, β6, α1 and η1 (Fig. 1 ▸ d). At the trimer–trimer interface (Fig. 1 ▸ d, boxed) α1 contains two conserved histidines, His136 and His140, that have previously been shown through mutational analysis to be key to stabilizing the hexamer (Baykov et al., 1995 ▸; Velichko et al., 1998 ▸).

A nine-residue consensus sequence defines the active site of bacterial family 1 inorganic pyrophosphatases: D-(S/G/N)-D-P-ali-D-ali-ali (where ali = C/I/L/M/V; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). In LpPPase this motif extends from residue 66 to residue 74, with the sequence 66DGDPVDVLV74, in the β5 strand and its surrounding loops (Fig. 2 ▸ a). Two key conserved aspartic acid residues in this motif that are essential for catalysis are Asp71, which is thought to bind two of the activating metal ions prior to substrate binding (M1 and M2), and Asp68, which is thought to help to activate the water molecule for hydrolysis (Figs. 2 ▸ a and 2 ▸ b; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). Other catalytically important residues include Glu32 (β2), Asp98 (β6) and Asp103 (β7–β8 loop), which bind three of the four required metals ions (M1, M3 and M4) (Figs. 2 ▸ a and 2 ▸ b). One proposed mechanism for PPase catalysis is that a water molecule, activated by M1, M2 and Asp68, acts as a nucleophile to attack the electrophilic phosphate moiety of PPi (Heikinheimo et al., 2001 ▸; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). The binding of PPi is also mediated by metal ions and several conserved residues, including Arg44, Tyr142 and Lys143 (Figs. 2 ▸ a and 2 ▸ b; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸).

The metal-binding sites are unoccupied in this apo LpPPase structure; however, three water molecules fill the pyrophosphate-binding position. Two sodium ions from the crystallization condition are bound to LpPPase, but not in the active site. One sodium ion is coordinated by two water molecules and the backbone carbonyls of Asp144, Glu146 and Lys149. The second sodium is bound by the side chain of Glu146 and three water molecules. Two other ligands present in the crystallization condition are bound to LpPPase: alanine and 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), both of which bind in pockets near His130 and/or His25, often from adjacent subunits. His25 is in the β-turn (TT) between β1 and β2 and His130 is in α1, both of which are part of the trimer–trimer interface (Figs. 1 ▸ d, boxed, and 2 ▸ a). Interestingly, neither His25 nor His130 is found in the other family 1 PPases shown; however, these positions are conserved in the other PPases as Asn and Leu, respectively (Fig. 2 ▸ a). This suggests that these histidine binding pockets may be unique to LpPPase.

3.2. Comparison with structurally similar proteins

Structural homologs of LpPPase were identified through the DALI Protein Structure Comparison Server and were compared via multiple sequence alignment using Clustal Omega (Fig. 2 ▸ a; Holm et al., 2023 ▸; Madeira et al., 2022 ▸). The structures that were most similar to LpPPase were those of other bacterial family I inorganic pyrophosphatases, with the most similar protein being EcPPase from E. coli (PDB entry 1obw), with an r.m.s.d. of 0.493 Å over 154 residues (Fig. 2 ▸ b; Harutyunyan et al., 1997 ▸). Other similar proteins included PPases from Acinetobacter baumannii (PDB entry 6k21, r.m.s.d. = 0.495 Å over 141 residues; Si et al., 2019 ▸) and Oleispira antarctica (PDB entry 3i4q, r.m.s.d. = 0.508 Å over 151 residues; Kube et al., 2013 ▸). The sequence identity between LpPPase and the PPases from E. coli, A. baumannii and O. antarctica was 59%, 58% and 56%, respectively. This is not uncommon as many PPases do not have high sequence identity outside the regions involved in the active site, substrate binding and oligomeric interfaces (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). A PPase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PDB entry 4xel) also had a similar sequence identity (57%) but a slightly larger r.m.s.d. of 0.532 Å over 120 residues, so while it was not a top hit in DALI it was similar enough be used successfully as a molecular-replacement search model (Fig. 2 ▸ a).

High sequence conservation was observed in the nine-residue consensus sequence, the residues important for catalysis and those involved in substrate binding in all four proteins (Fig. 2 ▸ a). Despite the larger size and homodimeric assembly of eukaryotic family 1 inorganic pyrophosphatases, such as YPPase from S. cerevisiae, which is 109 amino acids longer, the core OB-fold β-barrel is conserved (Fig. 2 ▸ c; Heikinheimo et al., 1996 ▸). Major structural differences occur outside the OB-fold β-barrel and many of the catalytically significant residues are identical (Heikinheimo et al., 1996 ▸, 2001 ▸; Lahti et al., 1990 ▸; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). In addition to high structural conservation between the bacterial monomers, the oligomeric architecture is also likely to be conserved as the PPases from E. coli and A. baumannii are confirmed to be hexamers (Harutyunyan et al., 1997 ▸; Si et al., 2019 ▸).

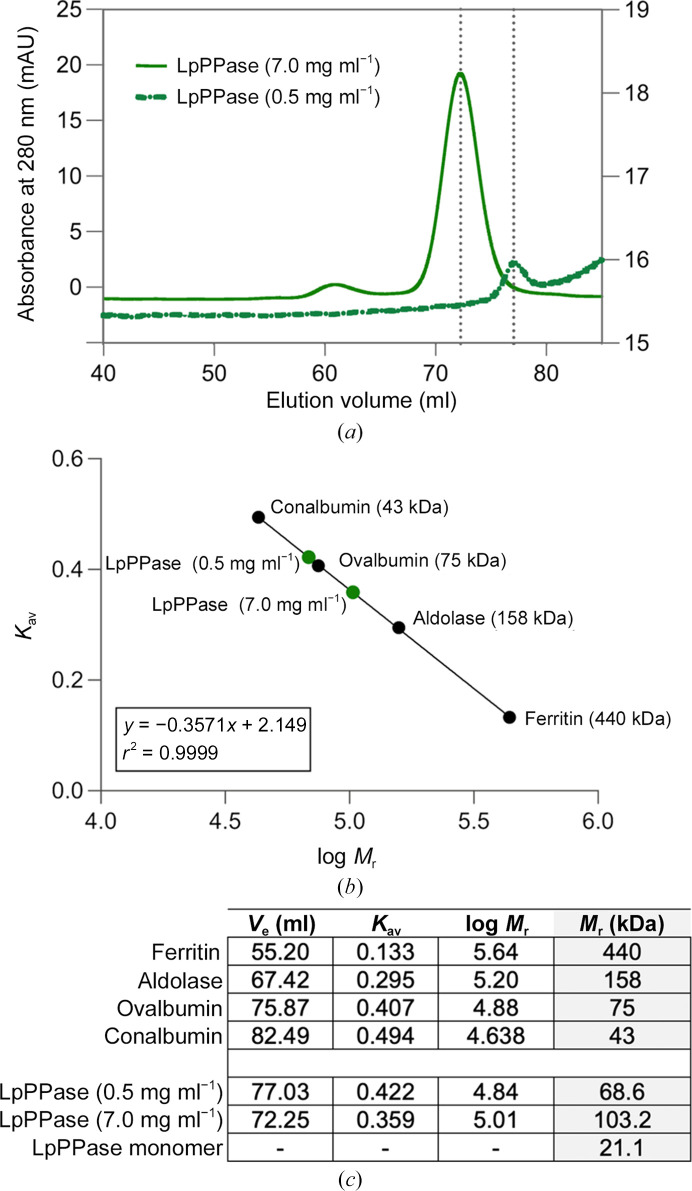

3.3. Oligomeric state of LpPPase

To confirm the oligomeric state of LpPPase experimentally, SEC was used (HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg; Fig. 3 ▸ a) A SEC calibration curve was used to calculate the relative molecular weight (M r) of the protein (Fig. 3 ▸ b). Two concentrations of LpPPase were tested, 0.5 and 7.0 mg ml−1. LpPPase resolved as a single peak in each case, with elution volumes of 77.03 and 72.23 ml, respectively. The corresponding partition coefficients (K av) were 0.422 at 0.5 mg ml−1 and 0.358 at 7.0 mg ml−1, resulting in an M r of 68.6 and 103.2 kDa, respectively (Fig. 3 ▸ c).

Figure 3.

SEC analysis of LpPPase. (a) Two concentrations of LpPPase were investigated using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), with elution volumes (V e) indicated by the dotted gray lines. LpPPase had a V e of 77.03 ml at 0.5 mg ml−1 (solid green line) and 72.25 ml at 7.0 mg ml−1 (dashed green line) from a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg SEC column. (b) The native molecular weights (M r) at each concentration (green circles) were estimated using a calibration curve (black circles). (c) The table shows the partition coefficients (K av), individual elution volumes (V e) and the known or calculated molecular weights (M r) of each protein. The calculated M r of LpPPase indicates likely trimeric (0.5 mg ml−1) and hexameric (7.0 mg ml−1) forms. The predicted monomeric weight of LpPPase is given in the last row for reference.

At low concentration (0.5 mg ml−1), the data indicate that LpPPase is likely to be trimeric, given that its monomeric weight is 21.1 kDa (Fig. 3 ▸ c). The higher concentration (7.0 mg ml−1) elution points to a hexameric assembly or a dimer of trimers, which would correspond to what is seen in the crystal structure and is common in other bacterial family I PPases. Although the calculated M r of 103.2 kDa at 7.0 mg ml−1 is slightly lower than that expected for a hexamer, no bacterial family I PPases have been found to form a pentamer, so the difference is most likely to be caused by the shape adopted by the hexameric form. A trimeric form is not typically seen for family I PPases in the absence of mutations at the trimer–trimer interface. However, the presence of Mg2+ ions has been demonstrated to stabilize the hexamer (Velichko et al., 1998 ▸) and the SEC buffer used does not contain Mg2+, providing a possible explanation of our observations at lower LpPPase concentrations.

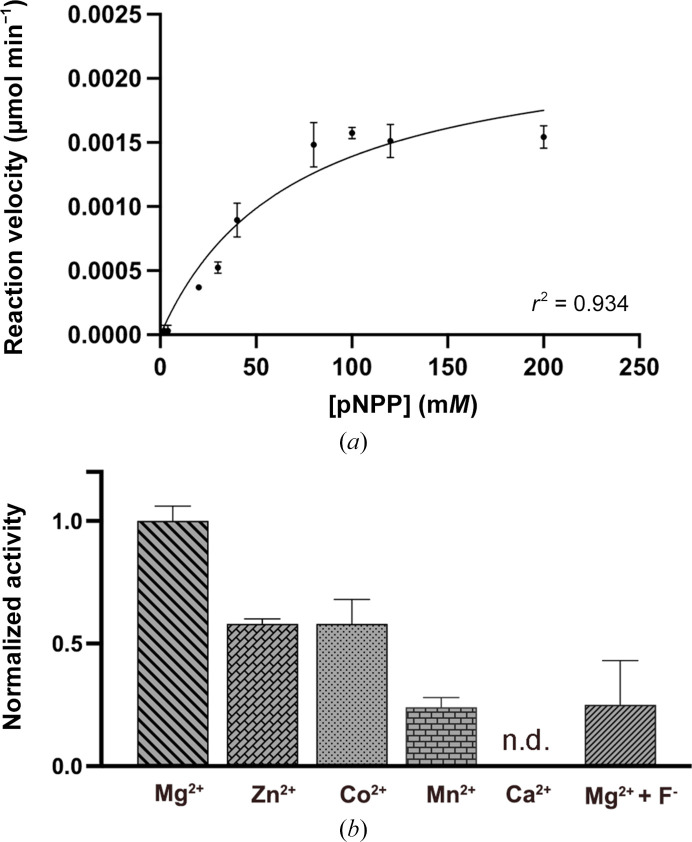

3.4. Activity assays

The enzymatic activity of LpPPase was evaluated using the general hydrolase substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) (Fig. 4 ▸ a). Most family I PPases use Mg2+ as a metal cofactor, so the initial enzyme assays were conducted in the presence of Mg2+. The curve was fitted with Michaelis–Menten kinetics, yielding a V max of 2.36 ± 0.27 nmol ml−1 min−1 and a K m of 69.7 ± 18.8 mM.

Figure 4.

LpPPase enzymatic activity. (a) LpPPase enzymatic activity on p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) using Mg2+ as a metal cofactor. The curve was fitted with the Michaelis–Menten equation, which gave a K m of 69.7 ± 18.8 mM and a V max of 2.36 ± 0.27 nmol ml−1 min−1. (b) LpPPase activity was investigated with four alternative metal cofactors, Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+ and Ca2+, using the pNPP concentration where V max was previously reached. Inhibition by F− in the presence of Mg2+ was also tested using sodium fluoride as a source of fluoride ions. The reaction velocities shown in (b) were normalized to V max in (a), which was measured with Mg2+ as the metal cofactor. Error bars show standard deviations. Reactions were run in duplicate. n.d., not detected.

Next, the metal cofactor was varied and reaction velocities were measured at the pNPP concentration where V max was previously achieved. All of the divalent cation cofactors tested (Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+ and Ca2+) resulted in a lower enzymatic activity for LpPPase towards pNPP compared with Mg2+, with effectively zero activity observed with Ca2+ (Fig. 4 ▸ b). Based on previous studies citing fluoride ions as a known PPase inhibitor, we predicted that they would also inhibit LpPPase activity (Kajander et al., 2013 ▸; Wu et al., 2021 ▸). At the pNPP concentration at which V max was achieved, using Mg2+ as the metal cofactor, sodium fluoride was also added as a source of fluoride ions (Fig. 4 ▸ b). With sodium fluoride, a similar decrease in reaction velocity was observed to the effect of Mn2+, Zn2+ and Co2+, although not as drastic as Ca2+ (Fig. 4 ▸ b).

Our results indicate that the optimal metal cofactor for LpPPase is indeed Mg2+, as predicted by the trends observed in family I inorganic pyrophosphatases (Parfenyev et al., 2001 ▸; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). These findings are similar to those observed for EcPPase, as Zn2+, Co2+ and Mn2+ have been shown to catalyze the PPi hydrolysis reaction, although at lower rates compared with Mg2+, while Ca2+ was shown to be a potent inhibitor of EcPPase (Samygina et al., 2001 ▸, 2007 ▸). Although the exact inhibition mechanism remains unknown, it is hypothesized that Ca2+ occupies improper positions within the active site that impair PPi anchorage and nucleophile generation (Samygina et al., 2001 ▸). Additionally, hydrolytic activity of LpPPase on pNPP only began when the substrate:enzyme ratio reached 10 000:1, indicating that pNPP might be a relatively poor substrate for LpPPase. The k cat for PPi reported for other bacterial family I PPases ranges between 200 and 2000 s−1, while the measured k cat of LpPPase for pNPP was 6.58 × 10−3 s−1 (Lahti, 1983 ▸; Kajander et al., 2013 ▸). Further studies could use an assay in which PPi hydrolysis can be measured, such as one incorporating malachite green to detect phosphates (Rumsfeld et al., 2000 ▸).

3.5. Potential for inhibitors

PPases are also known to be inhibited by bisphosphonates, an important class of drugs that have been in use for over 50 years to treat conditions associated with loss of bone density such as osteoporosis or Paget’s disease, as well as some cancers such as myeloma (Thompson & Rogers, 2007 ▸). Similar to PPi, bisphosphonates contain two phosphates; however, instead of a phosphoanhydride bond they are joined by a phosphoether bond with a central, nonhydrolysable C atom, which is responsible for their inhibitory effect in PPases. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate derivatives have been shown to inhibit the growth of several human pathogens, including Plasmodium falciparum and Trypanosoma cruzi, which cause malaria and Chagas disease, respectively (Martin et al., 2001 ▸). In their current usage, significant side effects have mostly been observed on long-term administration, which could make them a good candidate for treating short-term bacterial infections such as Legionnaires’ disease (Thompson & Rogers, 2007 ▸).

Targeting M-PPases, the family of integral membrane PPases, with bisphosphonate derivatives has also been proposed as a microbial therapeutic (Shah et al., 2016 ▸). Differential inhibitory effects have been observed between soluble PPases and M-PPases. For example, aminomethylenediphosphonate (AMDP) has a higher inhibitory effect than imidodiphosphate (IDP) on M-PPase activity, while soluble YPPase from S. cerevisiae is inhibited more strongly by IDP than by AMDP (Zhen et al., 1994 ▸). Structural analysis of each protein revealed differences in the size of the binding pocket, pointing to a possible basis for the observed inhibitory effects (Heikinheimo et al., 2001 ▸). As more structures of PPases, such as LpPPase, become available these identified differences may aid structure-based drug design. For example, our apo LpPPase structure revealed binding sites containing histidines at the oligomer interfaces which do not seem to be conserved in similar family I PPases. Using local structural features to help to design novel drugs, such as new bisphosphonate derivatives, could allow inhibitors with greater selectivity between PPase family members.

4. Conclusion

Soluble inorganic pyrophosphatases catalyze an essential reaction for cell survival: the hydrolysis of pyrophosphate (PPi) to inorganic phosphate (Pi). This mechanism prevents the toxic accumulation of PPi in cells, as well as producing Pi for use in key cellular functions such as ATP and nucleic acid synthesis. Here, we reported the crystal structure of LpPPase, an inorganic pyrophosphatase from L. pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease. The structure revealed a hexameric structure similar to many other bacterial family I PPases. Nine residues that are conserved among family I PPases were identified as part of the LpPPase active site. Through enzyme-activity assays, we also found that Mg2+ is the preferred divalent cation for LpPPase, with Ca2+ and F− identified as potential inhibitors. Given that only 7% of the proteome of the L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strain has been investigated structurally, this study both increases our understanding of L. pneumophila and adds to the body of research on family I PPases. Broadening our understanding of enzymes in these key biosynthetic pathways may allow us to identify new potential drug targets for various bacterial infections. Continuing to characterize pathogenic proteomes structurally and functionally is an invaluable resource for structure-based drug design and advancing our microbial therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF ChimeraX developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco with support from National Institutes of Health R01-GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Funding Statement

This project has been funded in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under Contract Nos. HHSN272201700059C and 75N93022C00036. Additional financial support for this research comes from Cottrell Scholar Award No. 28277 sponsored by Research Corporation for Science Advancement.

References

- Agirre, J., Atanasova, M., Bagdonas, H., Ballard, C. B., Baslé, A., Beilsten-Edmands, J., Borges, R. J., Brown, D. G., Burgos-Mármol, J. J., Berrisford, J. M., Bond, P. S., Caballero, I., Catapano, L., Chojnowski, G., Cook, A. G., Cowtan, K. D., Croll, T. I., Debreczeni, J. É., Devenish, N. E., Dodson, E. J., Drevon, T. R., Emsley, P., Evans, G., Evans, P. R., Fando, M., Foadi, J., Fuentes-Montero, L., Garman, E. F., Gerstel, M., Gildea, R. J., Hatti, K., Hekkelman, M. L., Heuser, P., Hoh, S. W., Hough, M. A., Jenkins, H. T., Jiménez, E., Joosten, R. P., Keegan, R. M., Keep, N., Krissinel, E. B., Kolenko, P., Kovalevskiy, O., Lamzin, V. S., Lawson, D. M., Lebedev, A. A., Leslie, A. G. W., Lohkamp, B., Long, F., Malý, M., McCoy, A. J., McNicholas, S. J., Medina, A., Millán, C., Murray, J. W., Murshudov, G. N., Nicholls, R. A., Noble, M. E. M., Oeffner, R., Pannu, N. S., Parkhurst, J. M., Pearce, N., Pereira, J., Perrakis, A., Powell, H. R., Read, R. J., Rigden, D. J., Rochira, W., Sammito, M., Sánchez Rodríguez, F., Sheldrick, G. M., Shelley, K. L., Simkovic, F., Simpkin, A. J., Skubak, P., Sobolev, E., Steiner, R. A., Stevenson, K., Tews, I., Thomas, J. M. H., Thorn, A., Valls, J. T., Uski, V., Usón, I., Vagin, A., Velankar, S., Vollmar, M., Walden, H., Waterman, D., Wilson, K. S., Winn, M. D., Winter, G., Wojdyr, M. & Yamashita, K. (2023). Acta Cryst. D79, 449–461.

- Baykov, A. A., Dudarenkov, V. Y., Käpylä, J., Salminen, T., Hyytiä, T., Kasho, V. N., Husgafvel, S., Cooperman, B. S., Goldman, A. & Lahti, R. (1995). J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30804–30812. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bryan, C. M., Bhandari, J., Napuli, A. J., Leibly, D. J., Choi, R., Kelley, A., Van Voorhis, W. C., Edwards, T. E. & Stewart, L. J. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 1010–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Legionnaires’ Disease and Pontiac Fever. https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/index.html.

- Chien, M., Morozova, I., Shi, S., Sheng, H., Chen, J., Gomez, S. M., Asamani, G., Hill, K., Nuara, J., Feder, M., Rineer, J., Greenberg, J. J., Steshenko, V., Park, S. H., Zhao, B., Teplitskaya, E., Edwards, J. R., Pampou, S., Georghiou, A., Chou, I. C., Iannuccilli, W., Ulz, M. E., Kim, D. H., Geringer-Sameth, A., Goldsberry, C., Morozov, P., Fischer, S. G., Segal, G., Qu, X., Rzhetsky, A., Zhang, P., Cayanis, E., De Jong, P. J., Ju, J., Kalachikov, S., Shuman, H. A. & Russo, J. J. (2004). Science, 305, 1966–1968. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choi, R., Kelley, A., Leibly, D., Nakazawa Hewitt, S., Napuli, A. & Van Voorhis, W. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 998–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cianciotto, N. P. (2015). Future Microbiol. 10, 841–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cowtan, K. (2006). Acta Cryst. D62, 1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cowtan, K. (2012). Acta Cryst. D68, 328–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Farquharson, K. L. (2018). Plant Cell, 30, 951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harutyunyan, E. H., Oganessyan, V. Y., Oganessyan, N. N., Avaeva, S. M., Nazarova, T. I., Vorobyeva, N. N., Kurilova, S. A., Huber, R. & Mather, T. (1997). Biochemistry, 36, 7754–7760. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Heikinheimo, P., Lehtonen, J., Baykov, A., Lahti, R., Cooperman, B. S. & Goldman, A. (1996). Structure, 4, 1491–1508. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Heikinheimo, P., Tuominen, V., Ahonen, A. K., Teplyakov, A., Cooperman, B. S., Baykov, A. A., Lahti, R. & Goldman, A. (2001). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 3121–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, J. K. (2001). Biological Role of Inorganic Pyrophosphate. New York: Springer.

- Holm, L., Laiho, A., Törönen, P. & Salgado, M. (2023). Protein Sci. 32, e4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 133–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kajander, T., Kellosalo, J. & Goldman, A. (2013). FEBS Lett. 587, 1863–1869. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kankare, J., Salminen, T., Lahti, R., Cooperman, B. S., Baykov, A. A. & Goldman, A. (1996). Acta Cryst. D52, 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kube, M., Chernikova, T. N., Al-Ramahi, Y., Beloqui, A., Lopez-Cortez, N., Guazzaroni, M.-E., Heipieper, H. J., Klages, S., Kotsyurbenko, O. R., Langer, I., Nechitaylo, T. Y., Lünsdorf, H., Fernández, M., Juárez, S., Ciordia, S., Singer, A., Kagan, O., Egorova, O., Alain Petit, P., Stogios, P., Kim, Y., Tchigvintsev, A., Flick, R., Denaro, R., Genovese, M., Albar, J. P., Reva, O. N., Martínez-Gomariz, M., Tran, H., Ferrer, M., Savchenko, A., Yakunin, A. F., Yakimov, M. M., Golyshina, O. V., Reinhardt, R. & Golyshin, P. N. (2013). Nat. Commun. 4, 2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lahti, R. (1983). Microbiol. Rev. 47, 169–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lahti, R., Kolakowski, L. F., Heinonen, J., Vihinen, M., Pohjanoksa, K. & Cooperman, B. S. (1990). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1038, 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Langer, G., Cohen, S. X., Lamzin, V. S. & Perrakis, A. (2008). Nat. Protoc. 3, 1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu, B., Bartlam, M., Gao, R., Zhou, W., Pang, H., Liu, Y., Feng, Y. & Rao, Z. (2004). Biophys. J. 86, 420–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Madeira, F., Pearce, M., Tivey, A. R. N., Basutkar, P., Lee, J., Edbali, O., Madhusoodanan, N., Kolesnikov, A. & Lopez, R. (2022). Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W276–W279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. B., Grimley, J. S., Lewis, J. C., Heath, H. T., Bailey, B. N., Kendrick, H., Yardley, V., Caldera, A., Lira, R., Urbina, J. A., Moreno, S. N., Docampo, R., Croft, S. L. & Oldfield, E. (2001). J. Med. Chem. 44, 909–916. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Muder, R. R. & Yu, V. L. (2002). Clin. Infect. Dis. 35, 990–998. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Myler, P., Stacy, R., Stewart, L., Staker, B., Van Voorhis, W., Varani, G. & Buchko, G. (2009). Infect. Disord. Drug Targets, 9, 493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Newton, H. J., Ang, D. K. Y., van Driel, I. R. & Hartland, E. L. (2010). Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 274–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pang, A. H., Garzan, A., Larsen, M. J., McQuade, T. J., Garneau-Tsodikova, S. & Tsodikov, O. V. (2016). Chem. Biol. 11, 3084–3092. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parfenyev, A. N., Salminen, A., Halonen, P., Hachimori, A., Baykov, A. A. & Lahti, R. (2001). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24511–24518. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Meng, E. C., Couch, G. S., Croll, T. I., Morris, J. H. & Ferrin, T. E. (2021). Protein Sci. 30, 70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C. H. & Chlebowski, J. F. (1985). J. Biol. Chem. 260, 7557–7561. [PubMed]

- Rodarte, J. V., Abendroth, J., Edwards, T. E., Lorimer, D. D., Staker, B. L., Zhang, S., Myler, P. J. & McLaughlin, K. J. (2021). Acta Cryst. F77, 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rumsfeld, J., Ziegelbauer, K. & Spaltmann, F. (2000). Protein Expr. Purif. 18, 303–309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Samygina, V. R., Moiseev, V. M., Rodina, E. V., Vorobyeva, N. N., Popov, A. N., Kurilova, S. A., Nazarova, T. I., Avaeva, S. M. & Bartunik, H. D. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 366, 1305–1317. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Samygina, V. R., Popov, A. N., Rodina, E. V., Vorobyeva, N. N., Lamzin, V. S., Polyakov, K. M., Kurilova, S. A., Nazarova, T. I. & Avaeva, S. M. (2001). J. Mol. Biol. 314, 633–645. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shah, N. R., Vidilaseris, K., Xhaard, H. & Goldman, A. (2016). AIMS Biophys, 3, 171–194.

- Si, Y., Wang, X., Yang, G., Yang, T., Li, Y., Ayala, G. J., Li, X., Wang, H. & Su, J. (2019). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stacy, R., Begley, D. W., Phan, I., Staker, B. L., Van Voorhis, W. C., Varani, G., Buchko, G. W., Stewart, L. J. & Myler, P. J. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, S., Abendroth, J., Phan, I. Q. H., Olsen, C., Staker, B. L., Napuli, A., Van Voorhis, W. C., Stacy, R. & Myler, P. J. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 1118–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thompson, K. & Rogers, M. J. (2007). Clin. Rev. Bone Miner. Metab. 5, 130–144.

- Vagin, A. & Lebedev, A. (2015). Acta Cryst. A71, s19.

- Velichko, I. S., Mikalahti, K., Kasho, V. N., Dudarenkov, V. Y., Hyytiä, T., Goldman, A., Cooperman, B. S., Lahti, R. & Baykov, A. A. (1998). Biochemistry, 37, 734–740. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, W. C. Jr (1996). Medical Microbiology, 4th ed., edited by S. Baron, ch. 40. Galveston: University of Texas Medical Branch. [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.-F., Wang, W.-S., Chen, S.-B., Xu, B., Li, Y.-D. & Chen, J.-H. (2021). Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 712328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q., Zhou, H., Chen, R., Qin, T., Ren, H., Liu, B., Ding, X., Sha, D. & Zhou, W. (2014). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1242–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhen, R. G., Baykov, A. A., Bakuleva, N. P. & Rea, P. A. (1994). Plant Physiol. 104, 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.