Abstract

Corneal blindness ranks third among the causes of blindness worldwide, after cataract and glaucoma. Corneal transplantation offers us a means to address this, and is currently the most commonly performed transplantation procedure worldwide – restoring the gift of sight to many an eye. Eye banks play a very important role in these procedures. India was quick to develop its own eye bank in 1945 soon after the launch of world’s first eye bank in 1944. The evolution over the past six decades has been tremendous, placing India on the top, with one of the largest eye-banking system in the world. As of 2023, around 740 members are registered under the Eye Bank Association of India. The highest-ever collection of 71,700 donor eyes was achieved in 2017-2018. The overall tissue utilisation rate ranged between 22 - 28 % for voluntary donations and 50% for hospital-based corneal retrieval programs. Though India has an excellent infrastructure and readiness for corneal transplantation surgery, the need of the hour is to create a strong and independent nodal system. It shall take care of the logistics and factor in technological advances – surgical and otherwise. Public awareness, a national corneal grid, and reducing the red-tape barriers, shall improve availability of grafts nationwide. This review aims to detail the evolution of eye banking in India, to provide a comprehensive understanding, and help the stakeholders focus on the road ahead to attain our targets faster.

Keywords: EBAI, evolution, eye banking, India, national cornea grid, tissue utilization

Corneal blindness ranks third among the causes of blindness worldwide, with nearly 10 million people having bilateral corneal blindness.[1] Interestingly, in India, corneal conditions are the most common cause (37.5%) of blindness in 0 to 49-year olds and the second most common cause (7.4%) in >50-year olds, as per the recent Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) survey.[2] Most of this burden comes under the ambit of preventable blindness, and what we cannot prevent, we can treat today thanks to advances in surgical technology. Corneal transplantation is currently the most commonly performed transplant procedure worldwide.[1]

India has a robust system of eye-banking set up over the years, ever since the inception of its first eye bank in 1945.[3] In 2012, Gain et al. estimated that 82 countries have set up eye banks and procured about 284,000 corneas, of which 185,000 corneal transplants were performed in over 116 countries.[1] Yet, there is a considerable shortage in the availability of donor corneas, with only one cornea available for every 70 required.[4] With a population of over 1.42 billion and an estimated 90% of global corneal blindness attributed to developing nations, the estimated need in India is escalating every year.[5] We need to reach a minimum collection of 200,000 tissues to perform 100,000 corneal transplants annually.[4,6,7] Despite the consistent growth in tissue procurement due to the collective efforts of many ophthalmologists and other advocates, we still need to catch up to address our current needs.

The concept of eye donation is not something foreign to our collective psyche. The noble and selfless practice is one that has been covered in our ancient texts. The legend of Kannapa Nayanar is widely narrated in southern India – the innocent and selfless nature in which the Shaivite saint prepared to offer both his eyes to Lord Shiva, whom he dearly worshipped [Fig. 1].[8]

Figure 1.

The Shaivaite saint Kannapa Nayanar, offering his eyes to the lingam of Lord Shiva

To reach the status of self-sufficiency, one must look at the road we have taken over the years, the challenges faced, and what lies ahead of us. This review aims to detail the evolution of eye banking in India, provide a comprehensive understanding, and help the stakeholders focus on the road ahead to attain our targets faster.

History

Eye banks (EBs) are institutions responsible for collecting/harvesting and processing donor corneas and distributing them to trained corneal surgeons to tackle corneal pathologies.[9,10] The first successful corneal transplant was performed by Edward Zirm in 1905 [Fig. 2a], and the first eye bank was founded in 1944 by Townley Paton in New York [Fig. 2b and c]. The first eye bank in India was started in 1945 at the Madras Eye Infirmary (currently known as the Regional Institute of Ophthalmology, Chennai) by Dr. R.E.S Muthiah, who also performed the first corneal transplant in 1948 [Fig. 3a and b].[11] The first recorded successful corneal transplant was in 1960 by Prof. R.P. Dhanda in Indore.[7,12] Before the 1970s, most of the transplant work was performed in Gujarat by Dr. Dhanda and Dr. Kalevar at the Civil Hospital in Ahmedabad [Fig. 4a-c].[13,14,15]

Figure 2.

(a) Edward Konrad Zirm, who performed the first successful corneal transplant in 1905. (b) Dr Townley Paton, performing one of the first corneal transplants in New York (1937). (c) A donor eye in a moist-chamber storage, an early practice. Source: Moffatt SL, Cartwright VA, Stumpf TH. Centennial review of corneal transplantation. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005 Dec; 33(6):642-57

Figure 3.

(a) Dr. R.E.S. Muthiah. (b) The Regional Institute of Ophthalmology, Chennai – the oldest eye hospital in Asia and the second worldwide

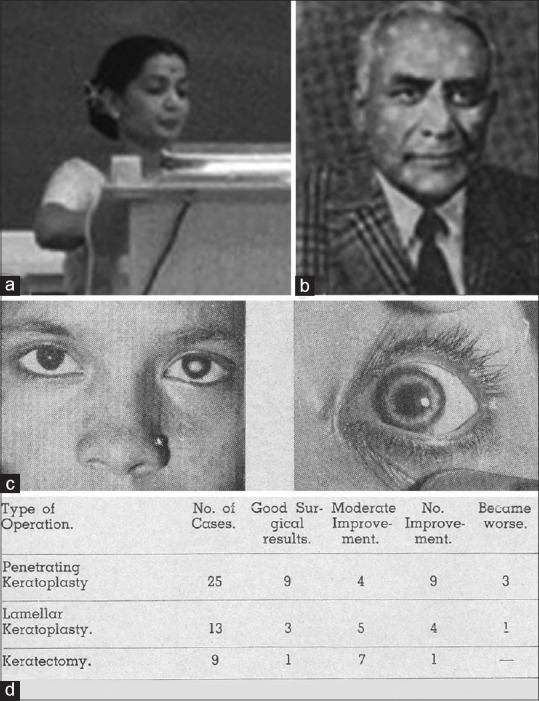

Figure 4.

(a) Dr. Vasundhara Kalevar. (b) Professor R.P. Dhanda. (c) One of the first few corneal transplants performed in India. (d) Case details of the first set of corneal transplants performed by Dr.R.P.Dhanda. Sources: Dhanda RP. Keratoplasty--recent experiences. J All India Ophthalmol Soc. 1961 Oct; 9:43–50. Dhanda RP, Kalevar VK. HAZARDS IN KERATOPLASTY. J All India Ophthalmol Soc. 1964 Oct; 12:99–106. Bansal R, Sharma M, Spivey BE, Honavar SG. A walk down the memory lane with Vasundhara Kalevar. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(12):4104-4106

Evolution over the years [Fig. 5]

Figure 5.

Timeline showing the evolution of Indian eye-banking over the years

The Ministry of Health (now recognized as the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare or the MoHFW) launched the National Programme for Control of Blindness (NPCB) in the year 1976.[16] It was the first program in the world tackling blindness and visual impairment, set up by the constant efforts of stalwarts such as Dr. Govindappa Venkataswamy, Dr. Lalit Prakash Agarwal, and Sir John Wilson.[17,18] This motivated several ophthalmologists nationwide to promote eye donation, establish EBs, and perform corneal transplantation. Envisaged under the 5-year plan model, the NPCB was a 100% centrally sponsored scheme with the aim of reducing the prevalence of blindness in India from 1.4% to 0.3% by 2020.[16,19]

The National Eye Donation Fortnight, held from the 26th of August to the 8th of September, was inaugurated in 1985 by the MoHFW as an annual event to create awareness on eye donation.[20] The umbrella organization, the Eye Bank Association of India (EBAI), was set up in 1989.[7] It aimed to increase public awareness to improve eye donations and establish uniform eye banking standards. The Transplantation of Human Organs Act was passed by the Indian Parliament in 1994, repealing the Corneal Transplant Act of 1983, thereby enabling harvest of eyes anywhere by a registered medical practitioner. Further inputs from corneal surgeons and experts in related aspects led to amendments to make the legislation favorable for eye-banking and eye-donation activities.[21]

In 2004, the Indian Government (NPCB) and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) collaborated to formulate a National Plan to tackle corneal blindness, setting a goal of 1 lakh (100,000) transplants each year by 2020.[4] The NPCB strengthened 82 EBs and 177 Eye Donation Centres (EDCs) in the XIth Five-Year Plan by providing financial assistance (15 lakhs and 1 lakh, respectively, to EB and EDC).[22] The XIIth Five-Year Plan (2012–17) had earmarked a significant portion of the NPCB budget to eye banking. A sum of twenty-five lakh rupess/INR each were allotted for all established Government EBs. Full assistance was given to develop new EBs, conforming to accepted quality standards. Funds for recruitment and training of EB staff, grief counsellors, and doctors were also provided under the program. NPCB currently reimburses Rs 2000/- for every pair of eyeballs collected by any EB, both governmental and voluntary/private.[16,20]

The adoption of lamellar transplantation techniques in 2007 (DALK, DSEK, DMEK) expanded availability by allowing one cornea to restore sight in up to two recipients. A few eye banks helped in the uptake of the same by providing pre-cut specimens for corneal surgeons to work with. The numbers of transplants employing the same have seen a steady uptick since 2012.[7]

In 2012, the EBAI partnered with the United States (US)-based SightLife to create a network between EBs and surgeons, to enable adequate tissue availability/improve tissue accessibility at a national level. Through this unique program, the corneal distribution system saw a 30% year-on-year growth since its inception and successfully connected seven EBs directly to surgeons in 50 Indian cities.[23,24] The EBAI and their connections helped India scale up eye donations and harvesting to over 50,000 eyes annually.

In the legislative aspect, feedback was provided by experts from the National Eye Bank (NEB) at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS, New Delhi) and the EBAI for processing amendment requests so as to facilitate better awareness measures and to ensure prompt harvesting of donor corneas. The Act was amended to include tissues in 2011 and was published in the National Gazette as Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues Rules 2014 (THOTA).[25] Corneas were explicitly clarified to be tissues and were not to be treated as organs. Consent for donation from the legal next-of-kin was extended to include more relations with possible legal responsibility for the deceased.[25] Trained technicians, who were not registered medical practitioners, were authorized to harvest corneas. Other aspects included a provision for mandatory required requests in all cases of intensive care mortality. The Act also advocated widespread availability of transplant coordinators and counsellors to strengthen the HRCP further. Overall, the legal framework in the country was made conducive to facilitate eye donation and corneal transplantation activities.[21]

Recommendations for eye banking and elimination of corneal blindness were developed at the National Expert Group meeting in November 2017 at the nation’s apex, tertiary eye-care center of Dr. R. P. Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences, AIIMS, New Delhi. Corneal experts and representatives from the NPCB and WHO (World Health Organization) worked together to develop the action plan.[20] It recommended exhaustive capacity building and training of all ophthalmologists in Regional Institutes of Ophthalmology and medical colleges in corneal transplantation and related practices. At the secondary level of healthcare delivery, maintenance of corneal blindness registries and details of transplantation referral were stressed upon. Training of district ophthalmic surgeons in post-operative management of patients who have undergone keratoplasty and effective networking with health workers and optometrists were recommended. Training of optometrists was initiated to ensure a wide area of coverage for tissue retrieval.[4] At the primary level, village-level health volunteers’ involvement in mediating between relatives and the nearest EB soon after death was proposed. Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) from the local community were involved in promoting awareness on eye donation.[20]

From 2017 onward, the NPCB was strengthened and expanded to cover all kinds of visual impairments. It was renamed as the National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) and is implemented all over the country uniformly. It primarily aims to reduce the prevalence of avoidable blindness to 0.25% by 2025.[26]

In 2018, the Indian Parliament passed an amendment to the Central Motor Vehicles Act, which ensured the recording of the donor status of the license holders.[27] This is currently enforced in a few states and has helped in the harvesting of healthy donor corneas.

Eye donations in India also have huge community support and acceptance in recent times, mostly due to the efforts of many philanthropists and social workers and through NGOs like the Lions Club International and the Rotary Club, to name a few (authors’ experience). Their support, although largely unrecognized in the public domain, helps us move closer to the target of achieving speedy transplantations for those in need.

Eye banking in India has taken a swift route to a strong network and communal acceptance. We now look into a few aspects that merit special mention, as to shaping our system over the years. They shed light on what has enabled us to get back on our feet past coronavirus disease (COVID), what our future challenges are, and what roads lie ahead of us.

Voluntary eye donation

Voluntary eye donation is an act where a person realizes a social responsibility toward people with corneal blindness and willingly comes forward to donate the eyes.[28] This is directly proportional to the general public’s awareness level. As a result of numerous efforts to improve awareness, India is witnessing an increasing pledge rate among donors. But this is not enough! Unlike blood donation, a pledge to donate eyes does not actively result in an eye donation as this can happen only after a person’s death. In a country with a lack of ‘presumed consent’ and a mandatory requirement for the next of kin to consent to eye donation, the very meaning of voluntary donation has to be revised. It essentially requires the timely decision of next of kin, who are grieving, to voluntarily donate the eyes of their beloved. Common barriers in voluntary donations are a) difficulty in deciding at a time of grief, b) lack of awareness about donation, and c) absence of a motivator to coordinate donation with an EB. This major setback could be addressed by collaborating with the local NGOs, who can play a pivotal role as catalysts in promoting voluntary eye donations. NGO volunteers/field workers are self-trained grief counsellors who can connect better with the local community and the EB.[29]

Hospital Cornea Retrieval Program

This was a robust program that was initiated in 1990, aiming to target hospital-based eye donations.[20] In India, a significant proportion of deaths occur in major teaching hospitals. The undeniable advantage of easy accessibility to potential donors was realized, and thus, the hospital cornea retrieval program (HCRP) was conceived.[28] In this program, the EB partners with secondary/tertiary care hospitals around them to catalyze eye donation among pathologic and accidental deaths. It involves an eye donation/grief counsellor whose main role is to share the grief with the bereaved family. They assist/motivate the family to take a positive step toward eye donation.[7]

The advantages of this program are availability of young donors, the ready availability of the donor’s medical history, quicker retrieval, and easy access to medical contraindications and causes of death.

The pointers for a successful HCRP program would be the following:[27,30,31,32]

Good partnership with local tertiary/secondary care hospitals having mortality rates of >2000/year

A primed hospital team that includes physicians, casualty nurses, staff, and other technicians

An automated system in place to alert the eye donation counsellor of all deaths

A mandatory request system to be followed before certifying death

Eye donation awareness boards in the hospital premises like casualty units and mortuary

A well-trained grief counsellor who can connect with the bereaved family and offer simple assistance like speeding medicolegal formalities

Slightly prolonged death-to-request intervals to allow the family to cope up with grief

Insist on the benefit to a blind person and reassure on anatomical restitution post eye donation

Eye bank infrastructure/workforce development

The eye banking model in India follows a three-tier, integrated system to ensure effective, efficient, and financially relevant functioning. Its main objective is to ensure safe and high-quality corneal tissues, accessible to everyone in a fair and equitable manner.[6] Creating uniform/standardized practices in eye banking was a challenge in a highly populated country with diverse cultures as ours. Collaborations with non-profit global health organizations like Orbis, SightLife, and Eyesight International have helped streamline the eye banking system.[24] Presently, the EBAI has developed strict regulatory guidelines, safety standards in eye banking, workforce training, and infrastructure development requirements and set up quality assurance protocols to ensure maintenance of uniform standard practices across the country.[33] The roles and functioning of the three-tier eye banking system are explained in Fig. 6. The EBs are now accredited by the National Accreditation Board of Hospitals (NABH) and are regularly reviewed.[7]

Figure 6.

The three-tier eye-banking system

EBs and EDCs are required to register and communicate with the State Health authorities as mentioned under the THOTA 2014. Retrieval centers do not need a THOTA registration but need to meet stringent criteria as defined by the governing bodies and have a memorandum-of-understanding with an accredited eye bank. After registration, an eye bank has under a year to prove compliance to all regulations during an appraisal by the Accreditation Authority to be declared fully operational. They should ideally prove processing of a minimum of 25 surgical grade corneas per year.[33]

Concurrently, training of corneal transplant surgeons is also ensured to ultimately reach the goal of curing corneal blindness. India is marching toward creating high-standard, high-volume eye banks with a robust corneal distribution system.

Preservation techniques

The success of corneal transplantation can largely be attributed to the evolution in preservation techniques. An ideal preservation technique will require indefinite storage of corneal tissues, with the best retention of endothelial cell viability. We have come a long way from the 48-hour moist chamber preservation technique to the routine use of Cornisol, which allows for up to 2 weeks of storage time.[6,34] In 1994, the development of in-house McCarey-Kaufman (MK) medium was initiated by Ramayamma International Eye Bank (RIEB)[7] and later by the NEB and Rotary Aravind International Eye Bank, Madurai (authors’ experience). They ensured that cost-effective, short-term hypothermic preservation was media supplied to most of the EBs in India. Cornisol (Aurolab, Madurai, India) was developed as an affordable alternative to Optisol GS as an intermediate storage medium. It had similar composition to Optisol with a few added components such as recombinant human insulin as a metabolic enhancer, vitamins, coenzymes, and trace elements. It was proved to be as effective as Optisol-GS in preserving donor corneal tissues for 14 days.[35]

As a tropical country, India has huge challenges in minimizing the death-to-retrieval time as endothelial viability worsens exponentially with delayed enucleation. The use of 5% povidone–iodine with Amikacin and Gatifloxacin eye drops largely helped in minimizing the risk of donor corneal infection during transplantation.[21] Recent days have seen a shift toward corneoscleral rim excision (in situ) from whole globe retrieval. This has helped decrease the death-to-preservation time, ensuring quicker tissue processing and good endothelial cell viability.[21]

Strict protocols for sterile tissue retrieval and processing techniques, quicker preservation time – preferably with an intermediate storage media – and good networking with transplant centers to enable early utilization will greatly add value to the core purpose of eye donation.[36]

Trends in tissue procurement and utilization

Indian eye banking has seen a steady rise in tissue collection and utilization ever since the EBAI was established in 1989.[6] As of 2023, around 740 members (EBs and EDCs) are registered under EBAI.[23] However, only 2% of those are responsible for nearly 70% of the nation’s transplants in a year, and only 14% of the overall EBs have an active reporting system.[23,37] Table 1 shows a consistent increase in tissue collection, correlating with improved eye donation awareness among the general public and the active involvement of the Government and NGOs. Nevertheless, the overall tissue utilization rate ranges between 22 and 28% for voluntary donations and 50% for HCRP donations.[38] Much better utilization rates are reported in certain EBs (RIEB, NEB) of India due to the targeted and dedicated approach of the team involved in tissue processing and distribution.[7,21]

Table 1.

Tissue collection trends in India (2010–2022)

| Year | Target | Achievement | Percentage achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-2011 | 60,000 | 44,900 | 74.9 |

| 2011-2012 | 60,000 | 49,400 | 82.4 |

| 2012-2013 | 50,000 | 53,500 | 107.1 |

| 2013-2014 | 50,000 | 49,600 | 99.1 |

| 2014-2015 | 50,000 | 58,800 | 117.5 |

| 2015-2016 | 50,000 | 59,800 | 119.6 |

| 2016-2017 | 50,000 | 65,100 | 1303 |

| 2017-2018 | 50,000 | 71,700 | 143.4 |

| 2018-2019 | 55,000 | 68,400 | 124.4 |

| 2019-2020 | 70,000 | 65,400 | 93.5 |

| 2020-2021 | 71,000 | 17,400 | 24.5 |

| 2021-2022 | 60,000 | 45,294 | 75.5 |

| 2022-2023 | 71,000 | 32414* | - |

*Until October 2022. (Source: ‘An Evaluation of the National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment, COVID-19 Disruptions and the Way Ahead for Universal Eye Health’. Available from https://www.impriindia.com/insights/national-programme-eye-health/(Last accessed on 9 August 2023)

While most EBs in India follow the voluntary donation program, which is dependent on general public awareness and largely acquires elderly donor tissues, successful EBs in India primarily focus on HCRP, increasing the tissue utilization rate tremendously.[4] Studies have shown that the HCRP model leads to a better conversion rate to successful donations and increases tissue utilization rates by up to 72%.[4] This has to be recognized, and similar changes must be enacted across the system to meet our targets earlier and provide high-quality tissues to all who require transplantation procedures.

Furthermore, increased utilization rates in recent years are largely attributed to the better utilization of non-optical grade donor corneal tissues, apart from the increasing need for therapeutic/tectonic transplants.[21] This was possible with the rapid adoption of lamellar transplantation techniques in 2007 (DALK, DSEK, DMEK), which expanded the corneal supply by allowing one cornea to restore sight in two recipients.[7] In addition, therapeutic-grade tissues are used for translational research and in improving keratoplasty training. Nevertheless, poor utilization is still a major drawback in our eye banking system. The common reasons for non-utilization include inadequate donor screening, absent or positive serology, bad handling/unsuitable tissues, and infection/culture growth.[34]

Corneal transplantation trends

India, a developing country, contributes to around 90% of global cases of ocular trauma and corneal ulceration.[5] Naturally, the leading indication for keratoplasty has always been corneal scarring and acute infectious keratitis. In addition, corneal infections are the reason behind an astounding 63.6% of people suffering from bilateral corneal blindness.[21] Followed by corneal infections, re-grafts are the next common indication of keratoplasty. As therapeutic transplants are usually done on an emergent basis, donor endothelial quality is often compromised, resulting in a huge amount of graft failure. Other common causes of failure include graft infection.[20] An irregular ocular surface, misuse of topical steroids, and patients’ non-compliance to follow-up and therapy due to financial burden can all be considered as additional risk factors that these patients with failed grafts constantly endure.

Although India has a strong infrastructural readiness to perform corneal transplantation, the transplant surgery rate is a meager 15 per million population, in comparison to the cataract surgical rate of 4000. Despite having over 740 EBs registered under EBAI, the overall average collection is a dismal 25 annually.[4] Successful large-scale keratoplasty programs ensuring regular training of cornea surgeons, increasing the operational efficiency of the existing EBs, and establishing a national cornea grid for equitable tissue distribution can help us move forward toward eliminating needless corneal blindness.[39]

COVID and eye banking

COVID directly impacted eye banking by halting all activities related to organ procurement, preparation, and distribution worldwide. India has the second-highest number of corneal collections and transplantation after the United States.[1] The sudden halt of eye banking activities resulted in many unprecedented issues.[40] Once the country resumed normal activities in June 2020, emergency cases were prioritized and the elective cases were further postponed. Voluntary donations were hit the hardest, and HCRP was initiated with strict precautionary measures. Therapeutic keratoplasties were prioritized, and keratoplasties for bilaterally blind were semi-prioritized.[41] Alternate procedures, like conjunctival flaps, partial thickness scleral grafts, tenon’s patch graft, and tarsorrhaphy, were commonly performed to preserve globe tectonicity.[42,43] In situ corneoscleral rim excisions and usage of intermediate storage media were mandated. In addition, COVID also saw an increase of 125.4% in the use of glycerin-preserved corneal tissues, which had reliable therapeutic outcomes.[44] The pool of eligible donors decreased because patients who had COVID or were suspected positive at the time of death were not eligible for organ donation, despite the lack of evidence demonstrating possible transmission of COVID-19 through corneal transplantation. For organ procurement, the handling and harvesting procedures changed. For instance, the recovery team members obtaining the tissue were required to wear personal protective equipment (PPE). Additionally, there was mandatory testing for the SARS-CoV-2 RNA virus before recovery of the corneas. The COVID pandemic highlighted an obvious need within eye banking – exploring long-term corneal storage techniques like cryopreservation, glycerol preservation, lyophilization, and gamma irradiation. Although all these techniques had a common drawback in that they resulted in an acellular corneal tissue devoid of endothelial cells, cryopreservation and lyophilization required complex and expensive technology.[45] Gamma irradiation technique provided a 2-year-long shelf-life in room storage, albeit with a patented technology available only in USA. Glycerol preservation was found to be an easily replicable and inexpensive alternative that could be utilized for emergencies, when the EBs are not open or available.[46]

Challenges in eye banking – Present scenario in India

• Socio-cultural Perceptions

One of the major obstacles to the eye donation process is the socio-cultural perceptions of society on the concept of organ/eye donation, which needs to be addressed consistently at intermittent intervals throughout the year by effective social awareness programs.[4]

• Tissue Supply

As of 2019, India collected just under 60,000 corneas per annum. Less than 28,000 were transplanted when the estimated demand was as high as 100,000 per annum or up to 70 per million.[4,7,33] This number has taken a further dip during and post-COVID, accentuating the existing need. The biggest challenge lies in the unequal EB infrastructure across the country.

• Tissue Retrieval

Poor retrieval rates of EBs with low procurement primarily center around ill-trained/poorly committed EB staff, inefficient operation protocols in EB functioning, recovery technicians, and grief counsellors, affecting the first step in approaching potential donor families.[23]

• Workforce

Training of corneal surgeons becomes crucial to sustain the improved utilization because keratoplasty has a longer learning curve and lesser monetary benefits and requires special infrastructure compared with the commonly performed cataract surgery.

No uniform workforce training is available across the country, nor does a statutory body back the training, leading to significant differences in capabilities across regions and EBs. Moreover, the trained workforce also juggles multiple clinical and non-clinical roles at the places of work, leaving little time for the targeted development of eye-banking activities and services.[4]

• Tissue Distribution

Tissue distribution is still plagued by the lack of an effectively functioning network that inter-connects regions with good donor tissue recovery to those with higher demand. It hampers the distribution of surplus donor corneas to the areas of need, thereby depriving those in need of the tissue and decreasing the utilization rates of the procuring EBs.

• Policy Support

The lack of policy support to increase access to donors, such as mandatory death notification by high-mortality hospitals to EBs, has severely impacted the ability of EBs to grow their numbers. National-level legislation allows recovery of tissue processing fees. However, due to poor implementation, many EBs do not receive timely reimbursements for collections.

• Financial Constraints

Although the Indian Government does incentivise EB infrastructure development as a one-time cash benefit for equipment and cornea collections, no ongoing benefit promotes the quality and utilization of collected corneas. There is no viable method of financial sustainability in an environment where the collection of processing fees is still frowned upon, and the cost of collections almost always outstrips the revenue (author experience).

Further, a Parliamentary Standing Committee (126th Report on Demands for Grants) on Health and Family Welfare in March 2021 noted that there had been under-utilization of funds earmarked for capacity building of personnel, which merits serious attention.[47] Thus, we see that a fight exists on two fronts – gathering funds for furthering eye care and eye donation, and utilizing the existing funds properly to maximally target the burden of disease. Detailed evaluations to address the factors behind the same are the need of the hour so that the noble intentions of the programs are not stifled.

• Maintaining Quality Standards

Although India boasts of having nearly 740 eye banking bodies, more than three-fourths maintain the bare minimum annual tissue collection of 25, as stressed upon earlier.[4] This is mainly due to the inefficient functioning of these retrieval centers. There needs to be a single auditing body for certifying EBs against updated eye banking standards, in addition to regular monitoring/review.

Road ahead: Need in India

Corneal transplantation requires far greater resources than other ophthalmic surgeries because of the need for suitable donor tissues, appropriate surgical facilities, and skilled surgeons. Although the limitation in corneal transplantation surgeries is multi-factorial, the crucial part is the insufficient availability of donor tissues of a suitable nature to meet our demands.[6]

• Socio-cultural Perception

The overall socio-cultural outlook of our population needs to be aligned toward eye donation. This can be made possible with government-supported yearlong public awareness programs aiming to reach a larger community, in addition to the existing efforts by NGOs.

• Tissue Collection and Utilization

With the maximum number of EBs in place and rising demands, India needs to reach a maximum utilization target. Effective donor screening at the retrieval level and strengthening of HCRP programs can help us achieve this. For tissue processing, well-trained EB personnel and better equipment are needed to efficiently screen eligible tissues and perform lamellar cuts for endothelial keratoplasty (EK). Only a few EBs in India are now prepared to supply pre-cut tissues for EK, which is likely a major limiting factor to greater adoption of performing DSAEK or DMEK instead of full-thickness penetrating keratoplasty.[23]

• Tissue Distribution

There is disproportionate access to EBs depending on the region. Although the EBAI reports over 740 registered centers, roughly 100 consistently report data, and only 21 are responsible for 70% of the transplants.[23] We see a need for the smaller EBs in India to reconsider their functioning and improve tissue collection. There should be a better network linking the different regions within India in terms of communication and means of transportation to distribute tissues to under-served areas. A nodal agency can be formed with the support of the EBAI, National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (NOTTO), and NPCB to create a ‘National Waitlist Registry’ that can ensure equitable distribution and maximum tissue utilization.[27]

• Quality Assurance

The EBAI should come up with strict regulatory standards for eye bank infrastructure, continuous monitoring board, standardization of serology kits, and EB workforce training that is uniformly followed across the country. The adverse event reporting system should be strengthened at the central level to manage transmissible diseases post corneal transplantation. A more hands-on approach to regulation is the need of the hour – with emphasis on standards to be maintained. An active role in communicating with the government has to be ensured to enable swift decisions backed by evidence-based medicine.

• Research and Development

EBs too have to evolve with time, staying abreast of the latest development, and swiftly introduce the latest in cutting-edge, evidence-based medicine. We see a need for the top tier EBs in India to expand their horizons and move toward functioning as tissue banking centers. This would involve working on amniotic grafts for ocular reconstruction, scleral tissues for grafts and reconstructive surgeries, and limbal allograft harvesting over time.[36] India should look forward to pioneer research involving bioengineered corneas and long-term preservation techniques retaining endothelial viability.

• Policy and Advocacy

While several steps have been taken toward training corneal specialists to tackle corneal blindness, there is still an under-utilization of this trained workforce. Corneal transplant centers, which function at the level of tissue transplantation, are still shackled by draconian restrictions catering to full-sized organ transplantation facilities. Liberalizing registration of corneal transplantation centers, thereby ensuring good coverage across all geographic locations, can help maximize the skills of several young trained corneal surgeons (author experience).

Some of the laws that can be of tremendous help to eye donation are “required request” (mandatory request to the family for eye donation during death declaration) or “required referral” laws (mandatory information to the nearest EB during death declaration). These shall ensure that all hospitals, trauma care centers, and mortuaries work hand in hand with EBs to increase eye donations. A ray of hope in this direction was the appreciable step taken by the Indian Parliament during the Central Motor Vehicle Rules amendment in 2018.[27] The information of pledged organ donors was included on the driving license and is successfully implemented in a few states like Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Chandigarh. These efforts and an efficient eye banking team can greatly improve utilizable donations.

Innovations to look forward in the future

Although there is certainly a discrepancy between the number of corneal transplants being performed and the number of patients with corneal blindness in India, there is more innovation taking place than ever before. First, much research is being performed to extend the shelf-life of suitable fresh tissues, including sterile cornea or glycerin-preserved cornea. Japan has led research studies utilizing cultured corneal endothelial cells for patients with endothelial dysfunction, which have yielded promising results.[48] This innovation will spread worldwide within the next few years.

There are also multiple prototypes of artificial corneas, which are being refined and improved worldwide. If an alternative to human tissues could be successfully utilized in a cost-efficient manner, with similar or better outcomes compared to fresh tissues, this would significantly close the gap that exists today.[49]

Early genomic studies appear to be promising in the field of corneal transplantation as well to 1) better identify patients who are at risk for disease progression and implement early intervention as well as 2) regenerative therapies to alter the expression of certain genes affecting the corneal epithelium and endothelium.[50]

Conclusion

India has a large number of individuals affected by corneal blindness. Simultaneously, it has excellent infrastructure and ‘readiness’ for corneal transplantation surgery. What is left is to match the valuable sacrifices from our kind-hearted donors to the people in need. This necessitates creating a strong and independent system to take care of the logistics and factor in advances in technology – surgical and otherwise. Such a network would ensure that each link in the chain can continue with their work, without concerns regarding menial tasks and regulatory matters. Several steps are being taken at a national level toward the same. Therefore, India is positioned to be a global leader in developing and promoting corneal innovations in the future years to come.

Financial support and sponsorship

Aravind Eye Hospital, Pondicherry.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gain P, Jullienne R, He Z, Aldossary M, Acquart S, Cognasse F, et al. Global survey of corneal transplantation and eye banking. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:167. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vashist P, Senjam SS, Gupta V, et al. Blindness and visual impairment and their causes in India:Results of a nationally representative survey. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0271736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saini JS, Reddy MK, Jain AK, Ravindra MS, Jhaveria S, Raghuram L. Perspectives in eye banking. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1996;44:47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliva MS, Schottman T, Gulati M. Turning the tide of corneal blindness. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60:423–7. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.100540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta N, Tandon R, Gupta SK, Sreenivas V, Vashist P. Burden of corneal blindness in India. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:198–206. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.120153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sangwan V, Gopinathan U, Garg P, Rao G. Eye banking in India:A road ahead. JIMSA. 2010;23:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaurasia S, Mohamed A, Garg P, Balasubramanian D, Rao GN. Thirty years of eye bank experience at a single centre in India. Int Ophthalmol. 2020;40:81–8. doi: 10.1007/s10792-019-01164-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Setty ED. The Valayar of South India. New Delhi, India: Inter-India Publications; 1990. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao GN. What is eye banking?Indian J Ophthalmol. 1996;44:1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao GN, Gopinathan U. Eye banking:An introduction. Community Eye Health. 2009;22:46–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kannan KA. Eye donation movement in India. J Indian Med Assoc. 1999;97:318–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jose R, Sachdeva S. Eye banking in India. J Postgrad Med Educ Train Res. 2008;3:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhanda RP. Keratoplasty--recent experiences. J All India Ophthalmol Soc. 1961;9:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhanda RP, Kalevar VK. Hazards in keratoplasty. J All India Ophthalmol Soc. 1964;12:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bansal R, Sharma M, Spivey BE, Honavar SG. A walk down the memory lane with Vasundhara Kalevar. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:4104–6. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2159_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma R, Khanna P, Prinja S, Rajput M, Arora V. The national programme for control of blindness in India. Australas Med J. 2011;4:1–3. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2011.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripathy K. Prof Lalit Prakash Agarwal (1922–2004)—The planner of the first-ever national blindness control program of the world. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2017;9:1179172117701742. doi: 10.1177/1179172117701742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta PK, Shenoy S. Infinite Vision:How Aravind became the World's Greatest Business Case for Compassion. Berret-Koehler Publishers. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vemparala R. National Programme for Control of Blindness (NPCB) in the 12th Five year plan:An Overview. DJO. 2017;27:290–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta N, Vashist P, Ganger A, Tandon R, Gupta SK. Eye donation and eye banking in India. Natl Med J India. 2018;31:283–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-258X.261189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tandon R, Singh A, Gupta N, Vanathi M, Gupta V. Upgradation and modernization of eye banking services:Integrating tradition with innovative policies and current best practices. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:109–15. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_862_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jose R, Rathore AS, Rajshekar V, Sachdeva S. Salient features of the National Program for Control of Blindness during the XIth five-year plan period. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57:339–40. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.55064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taneja A, Vanathi M, Kishore A, Noah J, Sood S, Emery P, et al. Corneal blindness and eye banking in South-East Asia. In: Das T, Nayar PD, editors. South-East Asia Eye Health. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2021. [Last accessedon 2023 Jul 11]. pp. 255–66. Available from:https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-16-3787-2_15 . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bureau EN. 'SightLife is on a mission to eliminate corneal blindness globally'. Express Healthcare. 2017. [cited 2023 Jul 11]. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 09]. Available from:https://www.expresshealthcare.in/features/sightlife-is-on-a-mission-to-eliminate-corneal-blindness-globally/381795/

- 25.Act and Rules of THOA:NOTTO. [cited 2023 Jul 11]. [Last accessed on 9 August 2023]. Available from:https://notto.mohfw.gov.in/act-end-rules-of-thoa.htm .

- 26.Annual Report 2021 - 22 - Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [Last accessed on 9 August 2023]. Available from:https://main.mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/FinalforNetEnglishMoHFW040222.pdf .

- 27.Sharma N, Nathawat R, Parihar JKS. Policy framework for advancing eye banking and cornea transplantation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:2563–4. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2341_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aggarwal H, Gupta N, Garg P, Sharma M, Mittal S, Kant R. Hospital cornea retrieval programme in a startup eye bank - A retrospective analysis and lessons learned. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1517–21. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2455_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christy JS, Ramulu PK, Priya TV, Nair M, Venkatesh R. Analysis of motivating factors for eye donation among families of eye donors in South India - A questionnaire-based study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:3284–8. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3136_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma B. Eye donation awareness and conversion rate in hospital cornea retrieval programme in a tertiary hospital of central India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:NC12–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/27287.10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tandon R, Verma K, Vanathi M, Pandey RM, Vajpayee RB. Factors affecting eye donation from postmortem cases in a tertiary care hospital. Cornea. 2004;23:597–601. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000121706.58571.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muraine M, Menguy E, Martin J, Sabatier P, Watt L, Brasseur G. The interview with the donor's family before postmortem cornea procurement. Cornea. 2000;19:12–6. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joint Review of Eye Bank Standards of India 2013. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 14]. Available from:https://www.ebai.org/Eye%20bank%20standards%20of%20India.pdf .

- 34.Wilson SE, Bourne WM. Corneal preservation. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989;33:237–59. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(82)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basak S, Prajna NV. A prospective, in vitro, randomized study to compare two media for donor corneal storage. Cornea. 2016;35:1151–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanathi M, Tandon R, Panda A, Vengayil S, Kai S. Challenges of eye banking in a developing world. Exp Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;2:923–30. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma N, Arora T, Singhal D, Maharana PK, Garg P, Nagpal R, et al. Procurement, storage and utilization trends of eye banks in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:1056–9. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1551_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farazdaghi M. World's largest eye bank has served a nation for three decades. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2020;15:126–7. doi: 10.18502/jovr.v15i2.6728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Honavar SG. The Barcelona principles:Relevance to eye banking in India and the way ahead. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:1055–7. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1213_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karkhur S, Singh P, Mittal P, Banerjee L, Sharma B. Commentary:Eye banking, corneal transplantation and the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2023;71:502–3. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2270_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guidelines for Cornea and Eye Banking During COVID Era Version 1.0. [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 14]. Available from:https://www.ebai.org/pdf/EyeBankingGuidelines1105202V.1.pdf .

- 42.Agarwal R, Sharma N. Commentary:A review of long-term corneal preservation techniques:Relevance and renewed interests in the COVID-19 era. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1365. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1877_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaurasia S, Sharma N, Das S. COVID-19 and eye banking. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1215. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1033_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nathawat R, Sharma N, Sachdev M, Sinha R, Mukherjee G. Immediate impact of COVID-19 on eye banking in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:3653. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1171_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaurasia S, Das S, Roy A. A review of long-term corneal preservation techniques:Relevance and renewed interests in the COVID-19 era. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:1357. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1505_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thakkar J, Jeria S, Thakkar A. A review of corneal transplantation:An insight on the overall global post-COVID-19 impact. Cureus. 2022;14:e29160. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centre NI. Digital Sansad. Digital Sansad. [Last accessed on 2023 Jul 11]. Available from:https://sansad.in/rs .

- 48.Numa K, Imai K, Ueno M, Kitazawa K, Tanaka H, Bush JD, et al. Five-year follow-up of first 11 patients undergoing injection of cultured corneal endothelial cells for corneal endothelial failure. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:504–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holland G, Pandit A, Sánchez-Abella L, Haiek A, Loinaz I, Dupin D, et al. Artificial cornea:Past, current, and future directions. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:770780. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.770780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishida K. [Future Innovative Medicine for Corneal Diseases. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 2016;120:226–44. discussion 245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]