Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between quantitative epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) based on coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) and coronary slow flow (CSF).

Methods

A total of 85 patients with < 40% coronary stenosis on diagnostic coronary angiography were included in this retrospective study between January 2020 and December 2021. A semi-automatic method was developed for EAT quantification on CCTA images. According to the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade, the patients were divided into CSF group (n = 39) and normal coronary flow group (n = 46). Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore the relationship between EAT and CSF. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to evaluate the diagnostic value of EAT in CSF.

Results

EAT volume in the CSF group was significantly higher than that of the normal coronary flow group (128.83± 21.59 mL vs. 101.87± 18.56 mL, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in epicardial fat attenuation index between the two groups (P > 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that EAT volume was independently related to CSF [odds ratio (OR) = 4.82, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.06–7.27, P < 0.001]. The area under ROC curve for EAT volume in identifying CSF was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77–0.95). The optimal cutoff value of 118.46 mL yielded a sensitivity of 0.80 and a specificity of 0.94.

Conclusions

Increased EAT volume based on CCTA is strongly associated with CSF. This preliminary finding paves the way for future and larger studies aimed to definitively recognize the diagnostic value of EAT in CSF.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-023-03541-z.

Keywords: Coronary slow flow, Epicardial adipose tissue, Coronary computed tomography angiography

Background

Contrast agent flow in coronary angiography acts like coronary blood flow, and the distal vessel opacification may be delayed despite the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. This phenomenon of coronary angiography is commonly referred to as primary coronary slow flow (CSF) phenomenon. It has been considered a specific disease entity, however, whether it should be considered a specific coronary syndrome or a stage in the development of coronary microvascular dysfunction remains undefined [1, 2]. CSF was first proposed by Tambe et al. [3] in 1972, and its diagnosis was based on the results of coronary angiography. At present, the most applicable diagnostic standard was proposed by Beltrame [4]. CSF is characterized by normal or near normal epicardial coronary arteries (stenosis < 40%) with delayed distal vessel contrast opacification as evidenced by either thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 2 flow or corrected TIMI frame count > 27 frames (30 frames/s) in at least one epicardial vessel. The incidence of CSF is about 1-7% in patients with suspected coronary heart disease undergoing coronary angiography [5]. Angina pectoris is the most common clinical presentation of CSF patients, which affects their quality of life and even leads to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or cardiac death [6–8]. The aetiology and pathogenesis of CSF are not clearly defined, and there is no effective non-invasive examination.

Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is a visceral fat deposit between the myocardium and the visceral pericardium. EAT has paracrine effects. Released cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α diffusing and accumulating in the epicardial vascular wall may induce local inflammatory reactions that potentially result in endothelial dysfunction [9]. The latter leads to the increase of coronary vascular resistance and thus reduces coronary blood flow [10, 11]. Fat attenuation index (FAI) is an AI-driven quantitation of adipose tissue radiodensity which is computationally adjusted for a range of additional factors, such as CT technical parameters and adipocyte morphology [12, 13]. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is a commonly used non-invasive imaging modality to identify and measure EAT. Presently, no research evaluating EAT of CSF patients based on CCTA has been reported. In this study, we used CCTA for measuring the EAT volume (EATV) and FAI to investigate the relationship between EAT and CSF.

Methods

Study population

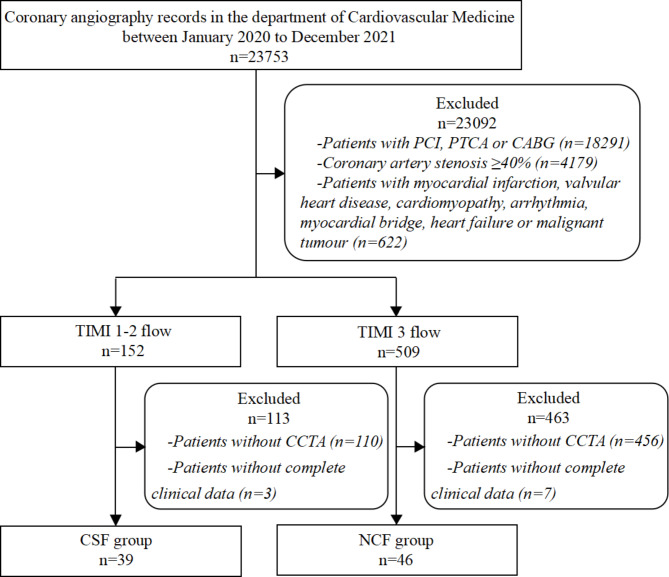

All coronary angiography records (n = 23,753) at the Department of Cardiology in General Hospital of Northern Theater Command between January 2020 and December 2021 were retrospectively collected. All patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography for suspected coronary artery disease. Patients with percutaneous coronary intervention (n = 16,648), percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (n = 1,584) or coronary artery bypass grafting (n = 59), coronary artery stenosis ≥ 40% (n = 4,179), myocardial infarction, heart valve disease, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, myocardial bridge, heart failure and malignant tumor (n = 622) were excluded. According to TIMI coronary flow grade, all patients were divided into two groups: CSF group (n = 152) with TIMI 1–2 flow and normal coronary flow group (NCF group, n = 509) with TIMI 3 flow. Both groups excluded patients who had not undergone CCTA or CCTA time distance coronary angiography more than 1 month (n = 110 in CSF group, n = 456 in NCF group) and had incomplete clinical information (n = 3 in CSF group, n = 7 in NCF group). We finally enrolled 39 subjects in CSF group and 46 subjects in NCF group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the participants. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, PTCA percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, TIMI thrombolysis in myocardial infarction, CCTA coronary computed tomography angiography, CSF coronary slow flow, NCF normal coronary flow

Clinical data

General data of patients were collected, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), previous history and laboratory test results within 3 days before coronary angiography. In addition, left ventricular (LV) function assessed by transthoracic echocardiography within 24 h before coronary angiography was obtained from hospital records, including LV end-diastolic diameter, LV ejection fraction (LVEF), and the ratio of diastolic mitral inflow velocity E peak and A peak (E/A).

CCTA data acquisition

CCTA was performed on a 256-slice CT scanner (Brilliance iCT, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, USA). Prospective ECG-gated scan was performed and all images were reconstructed using iterative reconstruction method. About 60–70 mL of iodine contrast agent was intravenously injected through the cubital vein at a rate of 4.5–5.5 mL/s using a high-pressure injector, followed by 20–30 mL of saline flushing at the same flow rate. A bolus tracking technique was used with a trigger threshold of 100 Hounsfeld units (HU) at the descending aorta. The scan parameters were set as follows: tube voltage 120 kV, tube current modulation technique, detector collimation 128 × 0.625 mm, pitch 0.16, slice thickness 0.9 mm, section increment 0.45 mm, rotation time 0.27 s, field of view 180 × 180 mm, matrix 512 × 512.

EATV and epicardial FAI measurement

EAT was quantitatively measured on axial CCTA images at 75% of the R-R interval. Pericardium was semi-automatically segmented and EAT was measured with a software tool as reported previously [14] from our group. Without knowledge of the trial design and clinical data, a radiologist with 5 years’ experience in coronary imaging diagnosis automatically segmented the pericardial contour with software and manually small scale enlarged or reduced the image annotation range to ensure a good match with the anatomical structure. Then a radiologist with more than 10 years’ experience in coronary imaging diagnosis checked and modified the segmentation result, and EAT parameters were extracted. The upper boundary of the pericardium was the bifurcation of pulmonary trunk, and the lower boundary was the apex cordis.

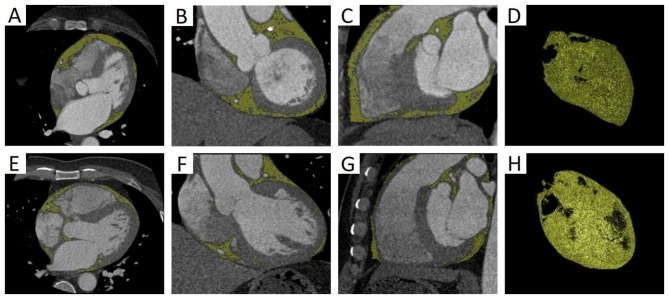

EAT was defined as all voxels with attenuation between − 190 HU and − 30 HU, and epicardial FAI was defined as the average CT attenuation of the adipose tissue within the pre-specified attenuation window of -190 HU to -30 HU. Our software was used to identify EAT and quantify its parameters (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Semi-automatic quantitative measurement of EAT on CCTA images. (A-D) EAT on axial, coronal, sagittal and three-dimensional reconstruction images in CSF group. EATV was 155.45 mL. (E-H) EAT on axial, coronal, sagittal and three-dimensional reconstruction images in NCF group. EATV was 104.29 mL

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)]. Categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages. Continuous variables were compared by independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared by chi-square test. The variables with significant differences in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression to determine the independent factors. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated to evaluate the diagnostic value. The optimal cutoff value was determined by the maximum Youden index. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics v.26 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Two-sided tests were used and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Basic clinical data

There were no statistically significant differences in age, gender, BMI, history of hypertension and smoking between CSF group and NCF group (P > 0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical data comparison of patients in CSF and NCF groups

| Variables | CSF group (n = 39) | NCF group (n = 46) | t/χ2/Z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Age (years) | 59.82 ± 9.67 | 57.54 ± 10.85 | −1.01a | 0.314 |

| Male, n (%) | 28 (71.79) | 29 (63.04) | 0.73b | 0.392 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.52 ± 3.49 | 24.65 ± 3.58 | −1.13a | 0.261 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 5.80 [5.20–7.70] | 6.50 [5.65–8.25] | −1.77c | 0.078 |

| NEU (×109/L) | 3.59 [3.07–4.70] | 3.93 [3.19–5.56] | −1.77c | 0.077 |

| HCY (umol/L) | 10.88 [10.07–13.46] | 9.43 [8.06–11.84] | −2.74c | 0.006 |

| CHOL (mmol/L) | 4.36 ± 1.14 | 3.78 ± 0.90 | −2.66a | 0.009 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.20 ± 0.30 | 1.14 ± 0.25 | −0.93a | 0.354 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.39 ± 0.77 | 2.03 ± 0.71 | −2.26a | 0.026 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 23 (58.97) | 21 (45.65) | 1.50b | 0.221 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 24 (61.54) | 20 (43.48) | 2.76b | 0.097 |

| CCTA | ||||

| EATV (mL) | 128.83 ± 21.59 | 101.87 ± 18.56 | −6.83a | < 0.001 |

| Epicardial FAI (HU) | −84.79 ± 5.96 | −83.48 ± 6.53 | 0.96a | 0.342 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LV diameter (mm) | 49.04 ± 4.53 | 47.47 ± 3.14 | −1.60a | 0.115 |

| LVEF | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.04 | 2.68a | 0.269 |

| E/A | 0.84 ± 0.29 | 0.92 ± 0.33 | 0.95a | 0.345 |

The data are expressed as n (%) or mean± SD or median [Q1-Q3]

CSF coronary slow flow, NCF normal coronary flow, BMI body mass index, WBC white blood cells, NEU neutrophils, HCY homocysteine, CHOL serum total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, CCTA coronary computed tomography angiography, EATV epicardial adipose tissue volume, FAI fat attenuation index, LV left ventricular, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, E/A the ratio of diastolic mitral inflow velocity E peak and A peak

a indicates t-value; b indicates χ2-value; c indicates Z-value

Coronary angiographic characteristics

In 20 of 39 CSF patients, coronary angiography revealed three vessels including left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex (LCx), and right coronary artery (RCA) with delayed distal vessel contrast opacification. TIMI 2 was present in 12 of the 20 patients, and TIMI 1–2 was present in 8 patients. In 19 of 39 CSF patients, coronary angiography revealed single vessel with delayed distal vessel contrast opacification, including LAD affected in 15 patients (TIMI 2 in 13 patients, TIMI 1–2 in 2 patients), LCx affected in 1 patient (TIMI 2), and RCA affected in 3 patients (TIMI 2 in all patients).

EAT, echocardiographic, and laboratory parameters

EATV in CSF group was greater than that in NCF group with statistical significance (Z = -6.83, P < 0.001), whereas there was no significant difference in epicardial FAI between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1). The levels of homocysteine, serum total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein in CSF group were higher than those in NCF group with statistical significance (t/Z = -2.74, -2.66, -2.26, P = 0.006, 0.009, 0.026), whereas other laboratory indicators and echocardiographic parameters showed no significant differences (all P > 0.05) (Table 1).

The association between EATV and CSF

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that EATV was independently related to CSF (OR 4.82, 95% CI 3.06–7.27, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors for CSF

| Variables |

Univariable analysis Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis (univariable P < 0.05) (univariable P < 0.05) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.97 (0.90; 1.06) | 0.512 | ||

| Gender | 1.02 (0.91; 1.44) | 0.093 | ||

| BMI | 0.96 (0.77; 1.21) | 0.235 | ||

| WBC | 1.47 (0.83; 2.02) | 0.539 | ||

| NEU | 0.54 (0.24; 1.99) | 0.354 | ||

| HCY | 1.13 (1.01; 1.26) | 0.006 | 1.10 (0.97; 1.24) | 0.154 |

| CHOL | 1.95 (1.00; 3.62) | 0.014 | 1.93 (0.92; 3.57) | 0.206 |

| HDL-C | 1.13 (0.93; 2.25) | 0.302 | ||

| LDL-C | 0.76 (0.28; 0.97) | 0.049 | 0.80 (0.33; 1.96) | 0.810 |

| Hypertension | 1.08 (0.79; 1.85) | 0.931 | ||

| Smoking | 1.70 (0.96; 2.83) | 0.63 | ||

| EATV | 4.80 (3.07; 7.24) | < 0.001 | 4.82 (3.06; 7.27) | < 0.001 |

| Epicardial FAI | 1.07 (0.93; 1.23) | 0.319 | ||

| LV diameter | 1.08 (0.84; 1.38) | 0.149 | ||

| LVEF | 0.83 (0.67; 1.20) | 0.175 | ||

| E/A | 1.22 (0.68; 2.29) | 0.383 | ||

BMI body mass index, WBC white blood cells, NEU neutrophils, HCY homocysteine, CHOL serum total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, EATV epicardial adipose tissue volume, FAI fat attenuation index, LV left ventricular, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, E/A the ratio of diastolic mitral inflow velocity E peak and A peak, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

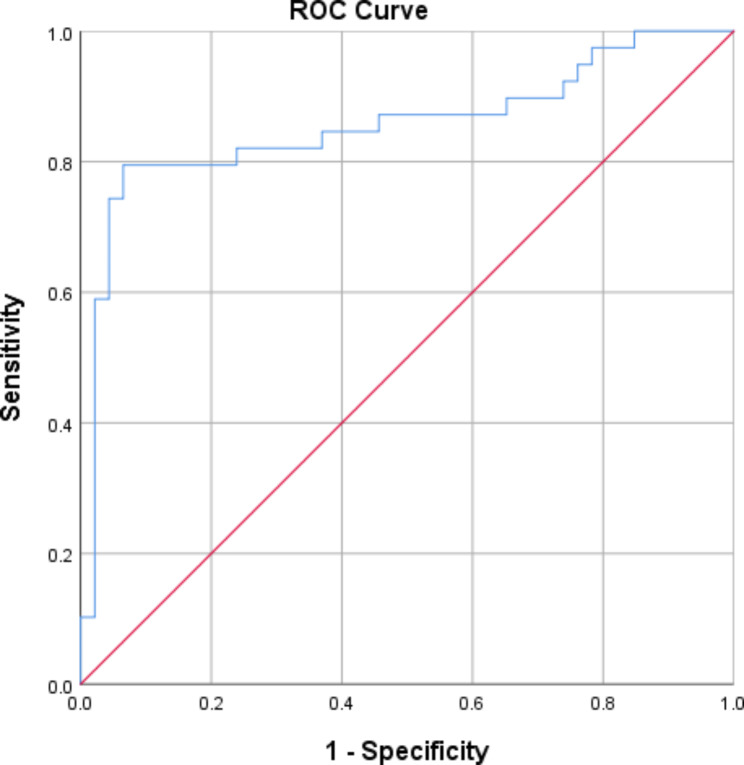

Diagnostic performance of EATV for identifying CSF

The ROC curve of EATV for identifying CSF was shown in Fig. 3. The AUC for EATV in identifying CSF was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.77–0.95), indicating a moderate diagnostic performance. The optimal cutoff value of 118.46 mL yielded a sensitivity of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.72–0.92) and a specificity of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.77–0.97).

Fig. 3.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of EATV for identifying CSF

Discussion

This study revealed the relationship between EAT and CSF. EATV in CSF group was greater than that in NCF group with statistical significance and multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that EATV was independently related to CSF. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between EAT based on CCTA and CSF. There are several previous studies on the relationship between EAT thickness based on two-dimensional echocardiography and CSF [15–18]. Erdogan et al. [15] and Comert et al. [16] analyzed 20 and 33 CSF patients respectively, and found that echocardiographic EAT thickness was positively associated with CSF. Wu et al. [17] analyzed 16 CSF patients and found that echocardiographic EAT thickness was an independent predictor for CSF and was negatively associated with coronary TIMI flow grade. Weferling et al. [18] analyzed 48 CSF patients over a 10-year time period and found that echocardiographic EAT thickness in CSF patients was significantly higher than that in patients with normal coronary flow, but this appeared to have no effect on the long-term prognosis. Two-dimensional echocardiography provided a single linear measurement, but was unable to provide EATV data. Nerlekar et al. [19] found that the intra- and inter-observer repeatabilities were better for CT measurement of EAT than for echocardiography measurement. FAI is an index associated with vascular inflammation [13]. We found that there was no significant difference in epicardial FAI between CSF group and NCF group. This was possibly because the paracrine inflammatory signals from the epicardial vascular walls in CSF were not sufficient to cause a significant increase in the density of EAT. In this study, the LAD was the most commonly involved vessel in CSF patients, which was consistent with the most of previous studies [20, 21]. However, Hawkins et al. [22] found that the LAD was not the main vessel involved in CSF patients, and the involvement of three vessels was evenly distributed. They explained this finding with the higher burden of cardiovascular risk in their population, which might lead to a more diffuse vessel involvement.

Several studies have found that EAT was correlated with the occurrence and severity of coronary artery disease [23, 24]. It remains controversial, however, whether CSF could be considered as the primary stage of coronary artery disease [22, 25]. At present, the pathogenesis of CSF is not clearly defined. Multiple studies have shown high levels of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α in CSF patients and a strong positive correlation with coronary TIMI flow grade [26–28], indicating that inflammatory mechanisms may be involved in the development of CSF. EAT secretes a large amount of bioactive molecules that affect energy metabolism and vascular inflammation, including inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α [9]. In physiological state, EAT mediates positive effects, keeps the balance of anti- and pro-inflammatory, and maintains normal structure and function of the myocardium and coronary arteries. While in pathological state, EAT releases a large amount of inflammatory cytokines, shifts the balance toward pro-inflammatory state, and interacts with myocardium and coronary arteries via paracrine and vasocrine pathways, thereby interfering with the metabolism and function of coronary arteries [29, 30]. Whether inflammatory cytokines released by EAT lead to CSF via certain pathological mechanisms requires further confirmation.

In addition, this study found that the level of homocysteine in CSF group was higher than that in NCF group with statistical significance. Homocysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid. Studies showed that elevated homocysteine level can lead to vascular endothelial injury, resulting in CSF [31, 32]. Demirci et al. [33] found that the level of homocysteine was significantly elevated in CSF group. They suggested that hyperhomocysteinemia may induce CSF endothelial dysfunction via direct toxic effects on endothelial cells, and may also indirectly induce endothelial dysfunction via inhibiting the activity of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase and reducing the synthesis of nitric oxide. Moreover, hyperhomocysteinemia may damage endothelial cells via oxidative stress induction, thereby causing CSF [34]. In this study, the levels of serum total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein in CSF group were higher than those in NCF group with statistical significance, which were consistent with the previous research results [35, 36].

There were certain limitations in this study. First, this was a single-center retrospective study with a relatively small sample size. The single-center nature of the study limited the ability to generalize findings to a broader population. The retrospective nature of the study limited the establishment of causality. Since the study was cross-sectional, it couldn’t establish a temporal relationship between EAT and the onset of CSF. Secondly, the medication of patients was not taken into account. Statins have been reported to be associated with a reduction in epicardial fat accumulation, especially when given in high doses [37]. However, in this study, CSF patients were given moderate doses. Finally, this study did not provide follow-up data. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to improve statistical power. We will further assess how EAT could be used for early diagnosis, mechanism research, treatment and prognosis in CSF patients.

Conclusions

EATV based on CCTA is strongly associated with CSF, and further studies are necessary to determine the role of EAT in the genesis and development of CSF.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CSF

Coronary slow flow

- TIMI

Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

- EAT

Epicardial adipose tissue

- IL

Interleukin

- TNF

Tumour necrosis factor

- CCTA

Coronary computed tomography angiography

- EATV

Epicardial adipose tissue volume

- FAI

Fat attenuation index

- NCF

Normal coronary flow

- BMI

Body mass index

- LV

Left ventricular

- LVEF

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- E/A

The ratio of diastolic mitral inflow velocity E peak and A peak

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- LCx

Left circumflex

- RCA

Right coronary artery

Author contributions

All authors have made a substantial intellectual contribution to this study. JT designed the study together. BQY and GGB contributed to administrative support. LBZ and YS contributed to data collection. JT and MQ contributed to data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Doctoral Scientific Research Start-Up Foundation of Liaoning Province (No. 2022010609-JH3/101), and the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (No. 2018225024 and No. 2020JH2/10300119). The funders play an important role in study design, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (Y[2022]013) and the study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command because of the retrospective nature of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ong P, Safdar B, Seitz A, Hubert A, Beltrame JF, Prescott E. Diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in the clinic. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:841–55. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henein MY, Vancheri F. Defining coronary slow flow. Angiology. 2021;72:805–7. doi: 10.1177/00033197211007702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tambe AA, Demany MA, Zimmerman HA, Mascarenhas E. Angina pectoris and slow flow velocity of dye in coronary arteries–a new angiographic finding. Am Heart J. 1972;84:66–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(72)90307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltrame JF. Defining the slow flow phenomenon. Circ J. 2012;76:818–20. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Z, Ren Y, Liu J. Low serum adropin levels are associated with coronary slow flow phenomenon. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2018;34:307–12. doi: 10.6515/ACS.201807_34(4).20180306B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aparicio A, Cuevas J, Morís C, Martín M. Slow coronary blood flow: pathogenesis and clinical implications. Eur Cardiol. 2022;17:e08. doi: 10.15420/ecr.2021.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aksoy S, Öz D, Öz M, Agirbasli M. Predictors of long-term mortality in patients with stable angina pectoris and coronary slow flow. Med (Kaunas) 2023;59:763. doi: 10.3390/medicina59040763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalikias G, Tziakas D. Slow coronary flow: pathophysiology, clinical implications, and therapeutic management. Angiology. 2021;72:808–18. doi: 10.1177/00033197211004390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:363–71. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fricke ACV, Iacobellis G. Epicardial adipose tissue: clinical biomarker of cardio-metabolic risk. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5989. doi: 10.3390/ijms20235989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutluer FO, Ural D, Güngör B, Bolca O, Aksu T. Association of Interleukin-1 gene cluster polymorphisms with coronary slow flow phenomenon. Anatol J Cardiol. 2018;19:34–41. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2017.8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oikonomou EK, Marwan M, Desai MY, Mancio J, Alashi A, Hutt Centeno E, et al. Non-invasive detection of coronary inflammation using computed tomography and prediction of residual cardiovascular risk (the CRISP CT study): a post-hoc analysis of prospective outcome data. Lancet. 2018;392:929–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuvaraj J, Cheng K, Lin A, Psaltis PJ, Nicholls SJ, Wong DTL. The emerging role of CT-based imaging in adipose tissue and coronary inflammation. Cells. 2021;10:1196. doi: 10.3390/cells10051196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Sun Y, Xu L, Greenwald SE, Zhang L, Zhang R, et al. Automatic quantifcation of epicardial adipose tissue volume. Med Phys. 2021;48:4279–90. doi: 10.1002/mp.15012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erdogan T, Canga A, Kocaman SA, Cetin M, Durakoglugil ME, Cicek Y, et al. Increased epicardial adipose tissue in patients with slow coronary flow phenomenon. Kardiol Pol. 2012;70:903–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comert N, Yucel O, Ege MR, Yaylak B, Erdogan G, Yilmaz MB. Echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue predicts subclinical atherosclerosis: epicardial adipose tissue and atherosclerosis. Angiology. 2012;63:586–90. doi: 10.1177/0003319711432452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Q, Yang B. Correlation between epicardial adipose tissue thickness and slow flow of non-obstructive coronary artery. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi [Chinese Journal] 2016;44:956–60. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weferling M, Vietheer J, Keller T, Fischer-Rasokat U, Hamm CW, Liebetrau C. Association between primary coronary slow-flow phenomenon and epicardial fat tissue. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33:E59–E64. doi: 10.25270/jic/20.00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nerlekar N, Baey YW, Brown AJ, Muthalaly RG, Dey D, Tamarappoo B, et al. Poor correlation, reproducibility, and agreement between volumetric versus linear epicardial adipose tissue measurement: a 3D computed tomography versus 2D echocardiography comparison. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:1035–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouzbahani M, Farajolahi S, Montazeri N, Janjani P, Salehi N, Rai A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of slow coronary flow phenomenon in Kermanshah province. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2021;13:37–42. doi: 10.34172/jcvtr.2021.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanghvi S, Mathur R, Baroopal A, Kumar A. Clinical, demographic, risk factor and angiographic profile of coronary slow flow phenomenon: a single centre experience. Indian Heart J. 2018;70(Suppl 3):290–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkins BM, Stavrakis S, Rousan TA, Abu-Fadel M, Schechter E. Coronary slow flow–prevalence and clinical correlations. Circ J. 2012;76:936–42. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma B, Katyal D, Patel A, Singh VR, Kumar S. Relation of systolic and diastolic epicardial adipose tissue thickness with presence and severity of coronary artery disease (the EAT CAD study) J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1470–5. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_194_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Li XG, Xu K, Hou J, You HR, Zhang RR, et al. Relationship between epicardial fat volume on cardiac CT and atherosclerosis severity in three-vessel coronary artery disease: a single-center cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22:76. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-02527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadr-Ameli MA, Saedi S, Saedi T, Madani M, Esmaeili M, Ghardoost B. Coronary slow flow: Benign or ominous? Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:531–5. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danaii S, Shiri S, Dolati S, Ahmadi M, Ghahremani-Nasab L, Amiri A, et al. The association between inflammatory cytokines and miRNAs with slow coronary flow phenomenon. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;19:56–64. doi: 10.18502/ijaai.v19i1.2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li JJ, Qin XW, Li ZC, Zeng HS, Gao Z, Xu B, et al. Increased plasma C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 concentrations in patients with slow coronary flow. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;385:43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roshanravan N, Shabestari AN, Alamdari NM, Ostadrahimi A, Separham A, Parvizi R, et al. A novel inflammatory signaling pathway in patients with slow coronary flow: NF-κB/IL-1β/nitric oxide. Cytokine. 2021;143:155511. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen Z, Li J, Fu Y, Zheng Y, Ma M, Wang C. Hypertrophic adipocyte-derived exosomal miR-802–5p contributes to insulin resistance in cardiac myocytes through targeting HSP60. Obes (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1932–40. doi: 10.1002/oby.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antoniades C, Kotanidis CP, Berman DS. State-of-the-art review article. Atherosclerosis affecting fat: what can we learn by imaging perivascular adipose tissue? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13:288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanriverdi H, Evrengul H, Enli Y, Kuru O, Seleci D, Tanriverdi S, et al. Effect of homocysteine-induced oxidative stress on endothelial function in coronary slow-flow. Cardiology. 2007;107:313–20. doi: 10.1159/000099068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N, Tian L, Ren J, Li Y, Liu Y. Evaluation of homocysteine in the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary slow flow syndrome. Biomark Med. 2019;13:1439–46. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2018-0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demirci E, Çelik O, Kalçık M, Bekar L, Yetim M, Doğan T. Evaluation of homocystein and asymmetric dimethyl arginine levels in patients with coronary slow flow phenomenon. Interv Med Appl Sci. 2019;11:89–94. doi: 10.1556/1646.11.2019.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rehman T, Shabbir MA, Inam-Ur-Raheem M, Manzoor MF, Ahmad N, Liu ZW, et al. Cysteine and homocysteine as biomarker of various diseases. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:4696–707. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elamragy AA, Abdelhalim AA, Arafa ME, Baghdady YM. Anxiety and depression relationship with coronary slow flow. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0221918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diah M, Lelo A, Lindarto D, Mukhtar Z. Plasma concentrations of adiponectin in patients with coronary artery disease and coronary slow flow. Acta Med Indones. 2019;51:290–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexopoulos N, Melek BH, Arepalli CD, Hartlage GR, Chen Z, Kim S, et al. Effect of intensive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy on epicardial adipose tissue in hyperlipidemic post-menopausal women: a substudy of the BELLES trial (beyond endorsed lipid lowering with EBT scanning) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1956–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.