Abstract

Antiherpetic activity of (1′S,2′R)-9-{[1′,2′-bis(hydroxymethyl)cycloprop-1′-yl]methyl}guanine (A-5021) was compared with those of acyclovir (ACV) and penciclovir (PCV) in cell cultures. In a plaque reduction assay using a selection of human cells, A-5021 showed the most potent activity in all cells. Against clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1, n = 5) and type 2 (HSV-2, n = 6), mean 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for A-5021 were 0.013 and 0.15 μg/ml, respectively, in MRC-5 cells. Corresponding IC50s for ACV were 0.22 and 0.30 μg/ml, and those for PCV were 0.84 and 1.5 μg/ml, respectively. Against clinical isolates of varicella-zoster virus (VZV, n = 5), mean IC50s for A-5021, ACV, and PCV were 0.77, 5.2, and 14 μg/ml, respectively, in human embryonic lung (HEL) cells. A-5021 showed considerably more prolonged antiviral activity than ACV when infected cells were treated for a short time. The selectivity index, the ratio of 50% cytotoxic concentration to IC50, of A-5021 was superior to those of ACV and PCV for HSV-1 and almost comparable for HSV-2 and VZV. In a growth inhibition assay of murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells, A-5021 showed the least inhibitory effect of the three compounds. These results show that A-5021 is a potent and selective antiviral agent against HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV.

Nucleoside analogs have been extensively investigated in the search for effective antiherpesvirus agents (6). Among those, acyclovir (ACV) is widely used for the systemic treatment of herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections. Recently, famciclovir and valaciclovir, the oral forms of penciclovir (PCV) and ACV, respectively, have also been approved for the treatment of HSV- and VZV-related diseases. Both ACV and PCV are acyclic guanosine analogs having potent activities against human herpesviruses in cell culture (2, 4, 9, 16). They also have good therapeutic efficacies in HSV-infected animals (3, 9, 16, 19). They are highly selective antiviral agents because they are specifically phosphorylated by viral thymidine kinase in infected cells and their triphosphate forms inhibit viral DNA polymerase at concentrations which do not affect cell replication (1, 7, 8, 10, 20).

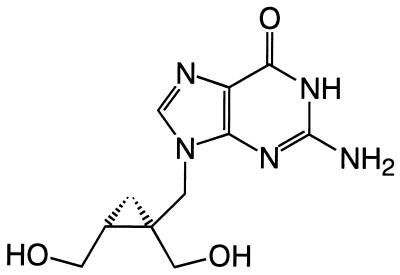

We have been preparing a series of novel nucleoside analogs. Of those analogs, (1′S,2′R)-9-{[1′,2′-bis(hydroxymethyl)cycloprop-1′-yl]methyl}guanine (A-5021) (Fig. 1) showed the most potent activity against HSV type 1 (HSV-1) (17). In the present study, the activity of A-5021 was compared with those of ACV and PCV in plaque reduction assays against HSV-1, HSV type 2 (HSV-2), VZV, and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in a range of human cells. Persistence of antiviral activity of A-5021 was compared with those of ACV and PCV. The cytotoxic effects of A-5021, ACV, and PCV were also evaluated in proliferating human cells and murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells.

FIG. 1.

Structure of A-5021.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

A-5021 was prepared by coupling (1S,2R)-[1,2-bis(benzoyloxymethyl)cycloprop-1-yl]methyl p-toluenesulfonate with 2-amino-6-chloropurine followed by deprotection (17). ACV and PCV were prepared at Ajinomoto Co., Inc., Kawasaki, Japan (11, 18).

Cell cultures.

MRC-5 cells (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and human embryonic lung (HEL) cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 100 U of penicillin G/ml, and 1 μg of amphotericin B/ml. Vero C1008 cells (Dainippon) were grown in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% FBS and the antibiotics at the concentrations mentioned above. HFL1 cells (Dainippon) were grown in Ham’s F-12K medium supplemented with 10% FBS and the antibiotics at the concentrations mentioned above. Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) were purchased from Kurabo Industries Ltd., Neyagawa, Japan, as an EpiPack Kit, which was supplied with appropriate medium, and cells were used for plaque reduction assays after one passage.

Viruses.

Stocks of HSV-1 and HSV-2 strains were prepared in Vero C1008 cells. Stocks of HCMV and cell-free preparations of VZV were prepared in MRC-5 cells and HEL cells, respectively. Clinical isolates of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV were isolated at Osaka University Medical School, Osaka, Japan, and working stocks of cell-free viruses were produced by limited passage.

Plaque reduction assays.

Confluent cell monolayers in six-well plates were infected with approximately 100 PFU of virus in medium. After adsorption at 37°C for 1 h, residual inoculum was replaced with 3 ml of medium containing test compound, 10% FBS, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 100 U of penicillin G/ml, 1 μg of amphotericin B/ml, and 0.8% methyl cellulose, except for VZV and NHEK. For VZV, the medium did not contain methyl cellulose and was supplemented with 3% FBS. For NHEK, serum-free medium supplied by the manufacturer (Kurabo) was used by adding methyl cellulose to a final concentration of 0.8%. Infected cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air until plaques were clearly visible. Cell monolayers were fixed and stained simultaneously with 0.13% crystal violet in 5% formalin solution, and plaques were counted under a stereoscopic microscope. The concentration of test compound which conferred 50% inhibition of plaque formation compared to virus control (untreated control) was interpolated from the observed data and defined as the IC50. In the experiment to investigate the effect of treatment duration on the inhibition of VZV replication in HEL cells, cell monolayers infected with VZV Kawaguchi were treated with A-5021, ACV, or PCV for 1 or 2 days, subsequently washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and reincubated in drug-free medium or they were treated continuously for 4 days. Plaques were counted on day 4 after infection.

Virus yield reduction assays.

Monolayers of MRC-5 cells in 96-well plates were infected with HSV-1 KOS or HSV-2 UW268 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2 PFU per cell in 50 μl per well of medium. After adsorption for 2 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air, residual inoculum was removed and cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS. Test compounds diluted in assay medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 100 U of penicillin G/ml, and 1 μg of amphotericin B/ml) were added to give 0.2 ml per well. Cell cultures were treated with the test compounds for 5 h, washed twice with PBS, and subsequently reincubated in drug-free medium, or they were treated with the test compounds continuously for 23 h. Supernatants were collected at 23 h after infection and stored at −80°C. Supernatants were titrated on Vero cells. By reference to the amount of virus produced by virus control monolayers (untreated cultures), the concentration of compound required to inhibit the virus control yield by 99% (IC99) was calculated.

Growth inhibition assay of HEL and MRC-5 cells.

A suspension of HEL or MRC-5 cells was seeded onto 24-well plates at 1 × 104 to 1.5 × 104 and 1.3 × 104 cells per well, respectively, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air. Medium was replaced with 1 ml of medium containing the test compound, and the cells were further incubated for 72 h. The cells were dispersed by trypsin, and the number of viable cells was counted under a microscope with a hemocytometer after trypan blue staining. By reference to the number of cells immediately before the addition of test compound as 0% and that after further incubation in control (untreated cultures) as 100%, the concentration of test compound which conferred 50% inhibition of cell proliferation was interpolated from the observed data and defined as the CD50. The selectivity index was determined by the ratio of the CD50 to the IC50.

Growth inhibition assay of murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells.

Colony formation assay of murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells was performed in accordance with the method of Okano et al. (14) with modifications. In brief, murine bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs of 10-week-old female C57BL/6NCrj mice (Charles River Japan, Inc., Kanagawa, Japan). A suspension of bone marrow cells, containing 4 × 104 cells per ml, was prepared in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium containing 0.8% methyl cellulose, 20% FBS, 200 U of murine interleukin 3 per ml, and test compound and seeded onto a 35-mm-diameter petri dish at a volume of 1 ml. After 7 days of incubation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air, the number of colonies formed was counted microscopically. The concentration of test compound which conferred 50% inhibition of colony formation compared to untreated control was interpolated from the observed data.

Statistical analysis.

A paired t test was used to compare the IC50s between A-5021 and ACV or PCV for clinical isolates of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV. A P value of <0.05/2 was considered statistically significant by Bonferroni’s adjustment for the multiplicity of test.

RESULTS

Antiherpesvirus activity of A-5021 in cell culture.

The antiviral activities of A-5021, ACV, and PCV in human cells were evaluated against several laboratory strains of herpesviruses by the plaque reduction assay (Table 1). Although the activities of the three antiviral compounds were influenced by the cells used, A-5021 proved to be the most potent against wild-type strains of the herpesviruses tested. A-5021 was >25-, >2-, 5-, and 2-fold more active than ACV and >50-, 10-, 3- to 8-, and 5-fold more active than PCV against HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, and HCMV, respectively. Particularly in NHEK, A-5021 was 150- and 8-fold more active than ACV against HSV-1 KOS and HSV-2 186, respectively. Interestingly, against VZV Kawaguchi, PCV was more potent than ACV in MRC-5 cells while it was less potent than ACV in HEL cells.

TABLE 1.

Antiherpesvirus activity of A-5021, ACV, and PCV in human cells

| Virus and strain | Cell | IC50 (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-5021 | ACV | PCV | ||

| HSV-1 KOS | HEL | 0.023 | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| MRC-5 | 0.011 | 0.27 | 0.70 | |

| HFL1 | 0.035 | 0.90 | 2.0 | |

| NHEKb | 0.014 | 2.1 | NDc | |

| HSV-1 Tomioka | MRC-5 | 0.0093 | 0.29 | 0.54 |

| HSV-2 186 | HEL | 0.24 | 0.60 | 2.7 |

| MRC-5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 1.2 | |

| HFL1 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 2.1 | |

| NHEK | 0.17 | 1.3 | ND | |

| HSV-2 UW268 | MRC-5 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 2.2 |

| VZV Kawaguchi | HEL | 0.67 | 3.4 | 5.6 |

| MRC-5 | 0.26 | 1.2 | 0.69 | |

| HCMV AD169 | MRC-5 | 9.2 | 19 | 45 |

Measured by the plaque reduction assay. All values listed are the average results of three to five experiments except for NHEK cells. For NHEK cells, the values listed are the results of one experiment.

NHEK were derived from foreskin.

ND, not done.

Clinical isolates of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV were also screened for susceptibility to A-5021, ACV, and PCV by the plaque reduction assay (Table 2). A-5021 was significantly more active than ACV and PCV against these clinical isolates tested. In a comparison of IC50s, A-5021 was 17- and 2-fold more active than ACV and 65- and 10-fold more active than PCV against HSV-1 (n = 5) and HSV-2 (n = 6), respectively, in MRC-5 cells. Against VZV, A-5021 was 7- and 18-fold more active than ACV and PCV, respectively, in HEL cells.

TABLE 2.

Activity of A-5021, ACV, and PCV against clinical isolates of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV

| Virus | No. of isolatesb | Cell | IC50 (μg/ml [mean ± SD])a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-5021 | ACV | PCV | |||

| HSV-1 | 5 | MRC-5 | 0.013 ± 0.0039 | 0.22 ± 0.077c | 0.84 ± 0.16d |

| HSV-2 | 6 | MRC-5 | 0.15 ± 0.050 | 0.30 ± 0.16e | 1.5 ± 0.69c |

| VZV | 5 | HEL | 0.77 ± 0.25 | 5.2 ± 1.7c | 14 ± 5.1c |

Measured by the plaque reduction assay.

Clinical isolates of HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV were isolated at Osaka University Medical School.

Significantly different from value for A-5021 at P < 0.005 (by paired t test).

Significantly different from value for A-5021 at P < 0.0005 (by paired t test).

Significantly different from value for A-5021 at P < 0.025 (by paired t test).

Like ACV and PCV, the activity of A-5021 against thymidine kinase-deficient strains of HSV-1 and HSV-2 was much lower than that for the corresponding thymidine kinase-positive strains (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Activity of A-5021, ACV, and PCV against thymidine kinase-deficient strains of HSV in MRC-5 cells

TK−, thymidine kinase deficient.

Measured by the plaque reduction assay. All values listed are the average results of three experiments.

Effect of treatment time on the antiviral activity of A-5021.

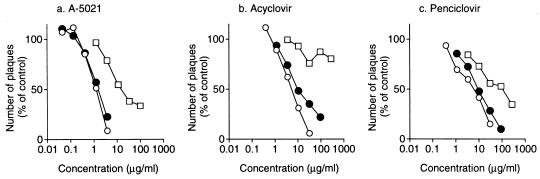

To investigate the effect of treatment time on the antiviral activity of A-5021, a virus yield reduction assay using HSV-1 and HSV-2 was performed (Fig. 2). MRC-5 cells were infected with HSV-1 or HSV-2 at 2 PFU per cell, and the cells were exposed to A-5021, ACV, or PCV for 5 or 23 h beginning after the completion of virus adsorption. Virus titers in culture supernatants were measured 23 h after infection. The IC99s derived from the data observed in the experiments shown in Fig. 2 are summarized in Table 4. The ratio of IC99 for 5 h of treatment to that for 23 h (continuous) of treatment is an index of persistence of antiviral activity. The closer the ratio is to 1, the greater the persistence of the antiviral activity after the removal of antiviral compound from the culture medium. Against both HSV-1 and HSV-2, A-5021 showed considerably more prolonged antiviral activity than ACV but less prolonged activity than PCV. However, irrespective of the treatment duration and extent of the persistence of antiviral activity, of the compounds tested, A-5021 showed the most potent antiviral activity against HSV-1 and HSV-2.

FIG. 2.

Effect of treatment time on the inhibition of HSV-1 and HSV-2 replication in MRC-5 cells. MRC-5 cells infected with HSV-1 KOS (a and c) or HSV-2 UW268 (b and d) at an MOI of 2 PFU per cell were treated with the test compounds after adsorption of the inoculum. The test compound was either incubated with cells until 23 h after infection (a and b) or removed by washing after 5 h of incubation and replaced by drug-free medium (c and d). Culture supernatants were harvested 23 h after infection, and cell-free virus titers of the supernatants were determined by plaque assay in Vero cells. Each point represents the mean titer of three to four cultures. Symbols: ○, A-5021; ▵, ACV; •, PCV; ◊, virus control yield.

TABLE 4.

Effect of treatment time on the inhibition of HSV-1 and HSV-2 replication in MRC-5 cells

| Virus and strain | Compound | IC99 (μg/ml)a when treated for:

|

5 h/23 h IC99 ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 h | 23 h | |||

| HSV-1 KOS | A-5021 | 0.027 | 0.0033 | 8.2 |

| ACV | 370 | 0.096 | 3,900 | |

| PCV | 0.65 | 0.17 | 3.8 | |

| HSV-2 UW268 | A-5021 | 1.2 | 0.062 | 19 |

| ACV | 74 | 0.14 | 530 | |

| PCV | 2.0 | 0.92 | 2.2 | |

IC99s shown were calculated from the data of the experiments illustrated in Fig. 2.

Against VZV, the plaque reduction assay was performed (Fig. 3). HEL cells infected with VZV were exposed to A-5021, ACV, or PCV for 1, 2, or 4 days beginning after infection and the numbers of plaques formed were counted on day 4 after infection. When the infected cells were exposed to A-5021, ACV, or PCV for 2 days, all the compounds showed antiviral activities almost equal to those observed after 4 days of treatment. The ratios of the IC50 for 2 days of treatment to that for 4 days (continuous) of treatment for A-5021, ACV, and PCV were 1.5, 4.1, and 1.8, respectively. However, when the cells were exposed to antiviral compounds for 1 day, ACV did not show enough antiviral activity even at a concentration of 280 μg/ml. The ratios of the IC50 for 1 day of treatment to that for 4 days (continuous) of treatment for A-5021, ACV, and PCV were 26, >72, and 15, respectively. Therefore, A-5021 showed more prolonged activity than ACV but less than PCV. However, as in the cases of HSV-1 and -2, A-5021 was the most active of the three compounds against VZV even with a short treatment duration.

FIG. 3.

Effect of treatment time on the inhibition of VZV plaque formation in HEL cells. HEL cells were infected with VZV Kawaguchi (cell-free virus) and treated with the test compounds for 1 (□), 2 (•), or 4 (○) days after adsorption of the inoculum. For 1- and 2-day treatments, the drug in the medium was removed by washing after the appropriate treatment time and replaced by drug-free medium. Four days after infection, plaques were counted. Each point represents the mean percentage of triplicate cultures.

Selectivity in HEL and MRC-5 cells.

To show the selectivity for HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV in HEL and MRC-5 cells, the cytotoxicities of A-5021, ACV, and PCV to replicating cells were examined (Table 5). Both cells were grown for 72 h with various concentrations of the compounds, and viable cell numbers were counted. The CD50s of A-5021, ACV, and PCV in HEL cells were 37, 87, and 290 μg/ml, respectively, and those in MRC-5 cells were 29, 100, and 160 μg/ml, respectively. Although the cytotoxicity of A-5021 was stronger than those of ACV and PCV in both cells, the selectivity index of A-5021 determined as the ratio of CD50 to IC50 for plaque formation for HSV-1 was higher than those of ACV and PCV. For HSV-2 and VZV, the selectivity indexes of A-5021 were almost comparable to those of ACV and PCV.

TABLE 5.

Cytotoxicity and selectivity of A-5021, ACV, and PCV in HEL and MRC-5 cells

| Cell type | Compound | CD50 (μg/ml)a | Selectivity indexb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 KOS | HSV-2 186 | VZV Kawaguchi | |||

| HEL | A-5021 | 37 | 1,600 | 150 | 55 |

| ACV | 87 | 87 | 150 | 26 | |

| PCV | 290 | 190 | 110 | 52 | |

| MRC-5 | A-5021 | 29 | 2,600 | 240 | 110 |

| ACV | 100 | 370 | 400 | 83 | |

| PCV | 160 | 230 | 130 | 230 | |

Values listed are the average results of two experiments.

Ratio of the CD50 to the IC50 (Table 1) in each cell.

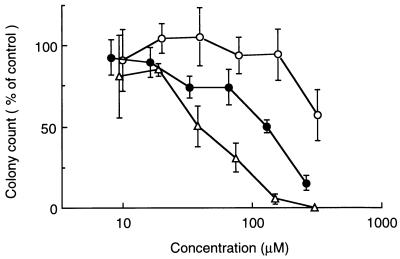

Effect on the growth of murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells.

The effect of A-5021 on the growth of murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells was measured and compared with those of ACV and PCV (Fig. 4). Murine bone marrow cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of compounds at a range of concentrations, and the number of colonies formed was counted microscopically. The inhibitory effect of A-5021 was the lowest of the three compounds, A-5021, ACV, and PCV. The 50% inhibitory concentrations for colony formation were >320, 39, and 90 μM for A-5021, ACV, and PCV, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Effect on the growth of murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells in vitro. The data are expressed as the percentage of granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cell growth compared to cultures that were not exposed to antiviral compound. Each point represents the mean percentage of triplicate cultures; error bars represent 1 standard deviation of the mean. Symbols: ○, A-5021; ▵, ACV; •, PCV.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the antiviral activity of A-5021 with those of ACV and PCV against HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, and HCMV by a plaque reduction assay with a selection of human cells, because antiviral activity is influenced by the cells used (5, 13). The results show that whichever the cells used, A-5021 was the most potent of the three compounds against all wild-type herpesviruses tested (Table 1). Especially in NHEK, the activities of A-5021 against HSV-1 and HSV-2 were 150- and 8-fold more potent than those of ACV. Since HSV replicates in epidermal cells, including keratinocytes (12), and causes cutaneous diseases in humans, evaluation with this cell may give a more precise prediction of the clinical efficacy of antiherpesvirus compounds.

The activity of PCV against VZV Kawaguchi was superior to that of ACV in MRC-5 cells but inferior in HEL cells, while A-5021 was the most potent in both cells. Similar results were reported for the antiviral activity of PCV against VZV Ellen, which is superior to that of ACV in MRC-5 cells but inferior in human foreskin fibroblast cells (2). It is not clear, however, which cells reflect the clinical efficacies of the compounds in human.

The fact that A-5021 had reduced antiviral activity against thymidine kinase-deficient strains of HSV-1 and HSV-2 (Table 3) suggests that the phosphorylation of A-5021 by viral thymidine kinase is important for its potent antiviral activity. Like ACV and PCV, the mode of action of A-5021 is revealed to be the inhibition of viral DNA synthesis by its triphosphate formed in virus-infected cells by viral and presumably cellular enzymes including viral thymidine kinase (15). At least partially, the potency of the antiviral activity of the nucleoside analog, which has such a mode of action, reflects the properties of its triphosphate—amount formed, stability, and inhibitory potency against viral DNA polymerases. It was reported that PCV causes more prolonged inhibition of HSV replication than ACV in cell culture (4), and this property of PCV was explained to be due to the high stability of intracellular PCV triphosphate (1, 7, 20). In our study, irrespective of the treatment duration, A-5021 showed a potent antiviral activity (Fig. 2 and 3; Table 4) and the persistence of antiviral activity of A-5021 was much greater than that of ACV but inferior to that of PCV. These findings are consistent with the results of Ono et al. that showed that in infected cells, the formation speed, the amount, and the stability of A-5021 triphosphate are superior or comparable to those of ACV triphosphate but inferior to those of PCV triphosphate and that the inhibitory activity of A-5021 triphosphate against viral DNA polymerase is considerably superior to that of PCV triphosphate and comparable to that of ACV triphosphate in a cell-free system (15).

When measured in exponentially growing HEL and MRC-5 cells, the cytotoxicity of A-5021 was stronger than those of ACV and PCV in both cells. However, in those cells, the selectivity indexes of A-5021 were almost comparable or were superior to those of ACV and PCV (Table 5). In animals, these nucleoside analogs often show cytotoxicity against bone marrow, where myelocytes proliferate actively. For an index of myelotoxicity, we measured growth inhibition against murine granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells in vitro. The inhibitory effect of A-5021 against colony formation was less than those of ACV and PCV (Fig. 4). Therefore, A-5021 has the potential to be used as safely as ACV and PCV.

In vivo evaluation of the activity of A-5021 against HSV infection is in progress, and the detailed results will be reported elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Suzuki and A. Okano for expert technical assistance, T. Sekiyama, T. Ohnishi, M. Yatagai, and T. Tsuji for supplying antiviral compounds, and R. Muraoka for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacon T H, Gilbart J, Howard B A, Standring-Cox R. Inhibition of varicella-zoster virus by penciclovir in cell culture and mechanism of action. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1996;7:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd, M. R., S. Safrin, and E. R. Kern. 1993. Penciclovir: a review of its spectrum of activity, selectivity, and cross-resistance pattern. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 4(Suppl. 1):3–11.

- 3.Boyd M R, Bacon T H, Sutton D. Antiherpesvirus activity of 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine (BRL 39123) in animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:358–363. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.3.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd M R, Bacon T H, Sutton D, Cole M. Antiherpesvirus activity of 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine (BRL 39123) in cell culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1238–1242. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.8.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins P, Bauer D J. The activity in vitro against herpes virus of 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine (acycloguanosine), a new antiviral agent. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1979;5:431–436. doi: 10.1093/jac/5.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darby, G. 1994. A history of antiherpes research. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 5(Suppl. 1):3–9.

- 7.Earnshaw D L, Bacon T H, Darlison S J, Edmonds K, Perkins R M, Vere Hodge R A. Mode of antiviral action of penciclovir in MRC-5 cells infected with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, and varicella-zoster virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2747–2757. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.12.2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elion G B, Furman P A, Fyfe J A, de Miranda P, Beauchamp L, Schaeffer H J. Selectivity of action of an antiherpetic agent, 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5716–5720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ertl P, Snowden W, Lowe D, Miller W, Collins P, Littler E. A comparative study of the in vitro and in vivo antiviral activities of acyclovir and penciclovir. Antivir Chem Chemother. 1995;6:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furman P A, St. Clair M H, Fyfe J A, Rideout J L, Keller P M, Elion G B. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus-induced DNA polymerase activity and viral DNA replication by 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine and its triphosphate. J Virol. 1979;32:72–77. doi: 10.1128/jvi.32.1.72-77.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geen G R, Grinter T J, Kincey P M, Jarvest R L. The effect of the C-6 substituent on the regioselectivity of N-alkylation of 2-aminopurines. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:6903–6914. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huff J C, Krueger G G, Overall J C, Jr, Copeland J, Spruance S L. The histopathologic evolution of recurrent herpes simplex labialis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:550–557. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machida H, Nishitani M, Suzutani T, Hayashi K. Different antiviral potencies of BV-araU and related nucleoside analogues against herpes simplex virus type 1 in human cell lines and Vero cells. Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35:963–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1991.tb01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okano A, Suzuki C, Takatsuki F, Akiyama Y, Koike K, Ozawa K, Hirano T, Kishimoto T, Nakahata T, Asano S. In vitro expansion of the murine pluripotent hemopoietic stem cell population in response to interleukin 3 and interleukin 6. Transplantation. 1989;48:495–498. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198909000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ono, N., S. Iwayama, K. Suzuki, T. Sekiyama, H. Nakazawa, T. Tsuji, M. Okunishi, T. Daikoku, and Y. Nishiyama. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Schaeffer H J, Beauchamp L, de Miranda P, Elion G B, Bauer D J, Collins P. 9-(2-Hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine activity against viruses of the herpes group. Nature (London) 1978;272:583–585. doi: 10.1038/272583a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekiyama T, Hatsuya S, Tanaka Y, Uchiyama M, Ono N, Iwayama S, Oikawa M, Suzuki K, Okunishi M, Tsuji T. Synthesis and antiviral activity of novel acyclic nucleosides: discovery of a cyclopropyl nucleoside with potent inhibitory activity against herpesviruses. J Med Chem. 1998;41:1284–1298. doi: 10.1021/jm9705869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiragami H, Koguchi Y, Tanaka Y, Takamatsu S, Uchida Y, Ineyama T, Izawa K. Synthesis of 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine (acyclovir) from guanosine. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1995;14:337–340. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sutton, D., and E. R. Kern. 1993. Activity of famciclovir and penciclovir in HSV-infected animals: a review. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 4(Suppl. 1):37–46.

- 20.Vere Hodge R A, Perkins R M. Mode of action of 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine (BRL 39123) against herpes simplex virus in MRC-5 cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:223–229. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]