Abstract

Background

Opioids are a mainstay for acute pain management, but their side effects can adversely impact patient recovery. Multimodal analgesia (MMA) is recommended for treatment of postoperative pain and has been incorporated in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. The objective of this quality improvement study was to implement an MMA care pathway as part of an ERAS program for colorectal surgery and to measure the effect of this intervention on patient outcomes and costs.

Methods

This pre-post study included 856 adult inpatients who underwent an elective colorectal surgery at three hospitals within an integrated healthcare system. The impact of ERAS program implementation on opioid prescribing practices, outcomes, and costs was examined after adjusting for clinical and demographic confounders.

Results

Improvements were seen in MMA compliance (34.0% vs 65.5%, P < 0.0001) and ERAS compliance (50.4% vs 57.6%, P < 0.0001). Reductions in mean days on opioids (4.2 vs 3.2), daily (51.6 vs 33.4 mg) and total (228.8 vs 112.7 mg) morphine milligram equivalents given during hospitalization, and risk-adjusted length of stay (4.3 vs 3.6 days, P < 0.05) were also observed.

Conclusions

Implementing ERAS programs that include MMA care pathways as standard of care may result in more judicious use of opioids and reduce patient recovery time.

Keywords: Colorectal surgery, enhanced recovery after surgery, multimodal analgesia, opioid use

Opioid analgesics are a mainstay for acute pain management, but their side effects adversely impact patient recovery. A recent study conducted at Baylor Scott & White Health (BSWH) revealed that opioid-related adverse drug events (ORADEs) occurred commonly following surgery and were associated with worse patient outcomes, including longer length of stay (LOS), reduced likelihood of being discharged home, higher rates of inpatient mortality, and higher costs of care.1 Concerns over the potential short- and long-term harm associated with opioids have prompted guidelines calling for use of other analgesics and judicious use of opioids.2 The American Pain Society recommends multimodal analgesia (MMA), the use of a variety of analgesic medications and techniques that target different mechanisms of action in the peripheral and/or central nervous system in combination with nonpharmacological interventions, for the treatment of postoperative pain.2 Components of MMA often include regional anesthesia, ketamine, gabapentinoids, acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The concurrent use of primarily nonopioid analgesics takes advantage of the additive, if not synergistic, effects that produce superior analgesia while decreasing opioid use and related side effects.3,4

MMA has been associated with superior pain relief and decreased opioid consumption compared with use of a single medication in randomized trials.5–7 MMA has also been associated with increased recovery speed and reductions in LOS and has been included as a foundational component of bundled surgical approaches such as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols.8 ERAS protocols are designed to reduce the stress of surgery and maximize recovery by focusing on several core areas of care, including optimizing pain control, nutrition and fluid management, and mobility.9 ERAS pathways generally promote opioids only on an as-needed basis when nonopioid analgesics fail and, as a result, have been shown to reduce opioid use in the postoperative hospital setting.2,3 There is evidence linking ERAS protocols with significant reductions in hospital LOS and costs and increases in patient satisfaction.10

Although several studies have provided evidence linking MMA and ERAS pathways to better pain control and reduced opioid use as well as improved clinical outcomes and reduced costs, these pathways have not yet been systematically implemented as standard of care for surgical patients. Additional studies are needed to determine how best to deploy MMA and ERAS protocols in real-world health care delivery systems and to provide supporting evidence of their ability to improve patient outcomes and reduce costs, as most of the current evidence was acquired from small studies with few sites and modest sample sizes.10 This study sought to address this gap in knowledge and foster widespread adoption of MMA and ERAS pathways by implementing an MMA care pathway as a part of an ERAS program for colorectal surgery in a large integrated health care system and evaluating the impact of the MMA care pathway on clinical outcomes and cost.

Methods

This study was approved by the BSWH Research Institute institutional review board. The study examined adherence to care processes and differences in opioid use and health outcomes before and after the implementation of an MMA care pathway as part of an ERAS program for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery in three BSWH hospitals.

Program implementation

MMA and ERAS measures were defined by the clinical teams as part of the implementation process. MMA compliance measures included the prescription of two or more nonopioid pain medications pre- and postoperatively and at discharge as well as the use of regional anesthesia during surgery. ERAS program components included 16 pre-, intra-, and postoperative measures for colorectal surgery focused on nutrition, infection prevention, and ambulation.

Implementation of the ERAS program was a standardized, system-level initiative with oversight and support from BSWH executive leaders that involved creating a system-level ERAS steering committee, engaging site clinical champions, developing ERAS order sets, modifying the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate capture of process measures, developing patient and provider educational materials, training clinical staff on ERAS/MMA documentation, creating dashboards to track compliance, and providing monthly feedback on compliance rates to executive and clinical site leaders. The postimplementation period began on June 1, 2018, with the deployment of a revised colorectal ERAS order set and EHR modifications to facilitate documentation of ERAS and MMA performance measures.

Study design

We used a pre-post study design to compare changes in adherence to MMA and ERAS process measures and in opioid use and health outcomes in the 2 years prior to and the 9 months following the implementation of the ERAS program with the MMA component. After observing a sharp increase in MMA adherence approximately 18 months prior to program implementation, we conducted a subanalysis limiting the pre-period to the year prior to implementation. We also performed a subanalysis to examine the impact of the reduced opioid use on patient outcomes. Low opioid use was defined as receiving ≤112.7 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) during hospitalization, the mean MME dose for the post-period.

Study population

The study population included patients 18 years of age or older admitted for a qualifying elective colorectal procedure at one of three BSWH community hospitals from June 1, 2016, through February 28, 2019. We identified patients who received colorectal surgery using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) procedure codes. Patients were excluded if they were not assigned an MS-DRG for colorectal surgery (329-334). We also excluded patients with costs and/or LOS above the 99th percentile as extreme outliers.

Measures

We collected patient demographics including age, race, ethnicity, income, and payer type. Clinical variables included body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, and Charlson Comorbidity Index score. We examined overall ERAS and MMA process measure adherence as well as adherence to individual measures. We also examined opioid type, dosage, and duration for opioids given before and after the procedure for the duration of the hospitalization. Opioid doses were converted to MME based on a conversion formula from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for nonintravenous doses and the Epocrates calculator for intravenous doses.11,12 Outcome measures included LOS, 30-day readmission, inpatient mortality, discharge to home, ORADEs, and cost of hospitalization. Readmissions within 30 days were defined according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services criteria for unplanned admissions13 and only included readmissions to acute care hospitals within our system. ORADEs were defined as the occurrence of one or more well-known side effects of opioids. These events included respiratory, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system complications identified by ICD-10 diagnosis codes or documented use of an opioid antagonist. Costs included all hospital costs for the index hospital visit and were adjusted to 2016 dollars.

Data sources

The majority of data for the colorectal surgery ERAS program were electronically extracted from the BSWH EHR and administrative and financial databases. Some ERAS process measures for colorectal surgery were not documented in a structured format prior to the EHR modification during program implementation and were abstracted by experienced chart auditors.

Statistical analysis

We conducted a univariate analysis to examine unadjusted differences in patient characteristics, ERAS and MMA process measure adherence, opioid use, and outcomes between the pre- and post-periods. Differences in categorical variables were compared using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Differences in continuous variables that did not violate normality assumptions were analyzed with independent Student’s t test and those with other distributions with Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests. We also used an interrupted time series model approach to examine rates of change in ERAS and MMA process measure adherence following ERAS program implementation.

Next, we conducted multivariable analyses to estimate risk-adjusted differences in patient outcomes. For binary outcomes, random intercept logistic regression models were used to assess differences in odds of in-hospital mortality, 30-day readmission, discharge to home, and ORADE. For continuous outcomes, a random intercept log-gamma regression model was used to determine risk-adjusted differences in LOS and costs. Age, sex, race, ethnicity, body mass index, ASA score, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and payer type were included as fixed effect covariates in all regression models. Hospital facility was included as a random intercept to account for within hospital clustering. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® (Enterprise Guide 7.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). We considered two-sided P < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

The study included a total of 856 patients (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between patients in the pre- and post-periods in terms of mean age (60.7 vs 61.8 years), body mass index (28.6 vs 28.6 kg/m2), or Charlson Comorbidity Index (3.3 vs 3.0). Most patients in the pre- and post-periods were white, had commercial insurance or Medicare, and had an ASA score of 2 or 3. There was a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of female patients (55.3% vs 47.5%, P = 0.04) and increase in the percentage of Hispanic patients (7.9% vs 11.3%, P = 0.03) between the pre- and post-periods.

Table 1.

Demographics of study patients

| Variable | Elective colorectal surgeries |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre (N = 618) | Post (N = 238) | P value | |

| Age (years): mean (SD) | 60.7 (13.7) | 61.8 (13.0) | 0.28 |

| Sex (female): n (%) | 342 (55.3%) | 113 (47.5%) | 0.04* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): mean (SD) | 28.6 (6.5) | 28.6 (5.9) | 0.94 |

| Race: n (%) | |||

| White | 555 (89.8%) | 227 (95.4%) | 0.08 |

| Black | 35 (5.7%) | 6 (2.5%) | |

| Asian | 6 (1.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Other | 22 (3.6%) | 4 (1.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 49 (7.9%) | 27 (11.3%) | 0.03* |

| Payer type: n (%) | |||

| Commercial | 349 (56.5%) | 120 (50.4%) | 0.17 |

| Medicare | 257 (41.5%) | 111 (46.6%) | |

| Others | 2 (0.3%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Self/uninsured | 10 (1.6%) | 3 (2.1%) | |

| ASA score: n (%) | |||

| 1 | 10 (1.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | 0.50 |

| 2 | 293 (47.4%) | 129 (54.2%) | |

| 3 | 291 (47.1%) | 96 (40.3%) | |

| ≥4 | 21 (3.4%) | 10 (4.2%) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.50%) | 1 (0.42%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index: mean (SD) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.0 (2.2) | 0.07 |

ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists; SD, standard deviation.

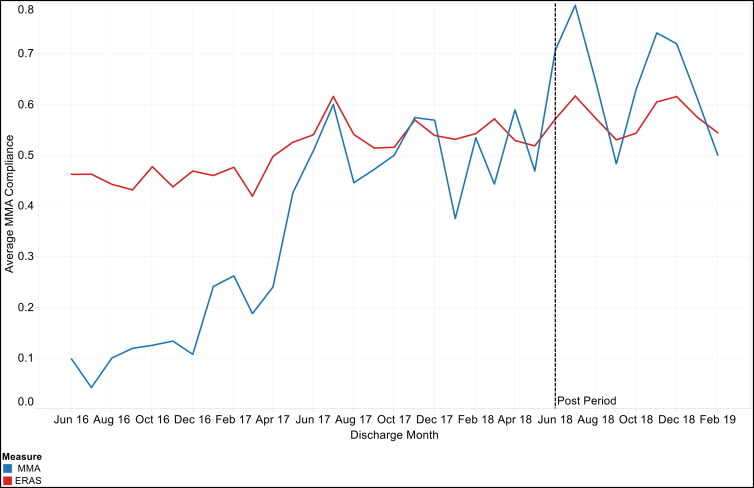

We observed a significant (P < 0.0001) increase in overall MMA and ERAS process measure compliance following program implementation (Table 2). Overall MMA compliance improved from 34.0% to 65.5% and ERAS compliance improved from 50.4% to 57.6%. The trends in MMA and ERAS process measure adherence as well as opioid doses over the study period are depicted in Figure 1. The estimates obtained from the time series analysis indicated a statistically significant upward trend in MMA (0.03, P < 0.0001) and ERAS (0.01, P < 0.0001) process measure adherence for colorectal surgery prior to program implementation (Table 3). ERAS and MMA process measure adherence increased immediately following program implementation, but these increases were not statistically significant. After an initial increase, ERAS and MMA measure adherence fluctuated during the period following program implementation, resulting in observed decreases in adherence trends.

Table 2.

Process measure compliance for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery before and after implementation of a multimodal analgesia care pathway as part of an enhanced recovery after surgery program

| Measure | Prea: 2 years (N = 618) |

Preb: 1 year (N = 309) |

Post (N = 238) |

P valuec (2 years) |

P valued (1 year) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall MMA compliance | 34.0% | 50.7% | 65.5% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| Preop | ≥ 2 nonopioid pain medications given 6 h before surgery | 27.5% | 45.6% | 62.6% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

| Intraop | Regional anesthesia used | 43.6% | 56.0% | 53.0% | 0.02* | 0.421 |

| Postop | ≥ 2 nonopioid pain medications given after surgery | 48.5% | 71.8% | 82.7% | <0.0001* | <0.002* |

| Discharged on ≥ 2 nonopioid pain medications | 15.9% | 29.1% | 64.3% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| Overall ERAS compliance | 50.4% | 54.4% | 57.6% | <0.0001* | <0.005* | |

| Preop | Clear liquids given up to 2 h before surgery | 14.1% | 21.7% | 32.0% | <0.0001* | <0.008* |

| Chlorhexidine bath or wipes used prior to surgery | 40.3% | 55.0% | 76.1% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| Bowel preparation completed | 77.4% | 79.9% | 79.4% | 0.51 | 0.88 | |

| Venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis administered | 3.1% | 4.9% | 4.2% | 0.45 | 0.72 | |

| Mu receptor antagonist for ileus prevention administered | 69.7% | 68.6% | 77.3% | 0.03* | 0.02* | |

| Glucose testing administered | 34.0% | 46.9% | 41.1% | 0.05* | 0.18 | |

| Intraop | No surgical drains placed prior to surgery | 78.5% | 75.7% | 84.8% | 0.03* | 0.007* |

| No nastrogastric tubes remaining after surgery or placed in the 24 h following | 97.9% | 99.0% | 98.7% | 0.36 | 0.75 | |

| Temperature remained >36°C | 38.8% | 43.4% | 48.7% | 0.008* | 0.21 | |

| Antiemetic prophylaxis administered | 92.1% | 92.1% | 52.5% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| Postop | Clear or full liquid diet within 6 h of surgery | 16.5% | 18.7% | 21.0% | 0.12 | 0.52 |

| Diet advanced past clear liquid diet within 24 h of surgery | 74.1% | 80.9% | 87.8% | <0.0001* | <0.026* | |

| Ambulated day of surgery | 14.4% | 17.5% | 35.7% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| Incentive spirometer used within 6 h of surgery | 0.8% | 1.6% | 4.2% | 0.01* | 0.08 | |

| Foley catheter removed within 24 h of surgery | 66.0% | 70.9% | 80.3% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| Avoidance of patient-controlled analgesia | 88.2% | 93.2% | 98.3% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

| MMA + ERAS compliance | 47.1% | 53.6% | 59.2% | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | |

aIncludes patients receiving care in the 2 years prior to implementation of the MMA care pathway (June 2016–May 2018).

bIncludes patients receiving care in the 1 year prior to implementation of the MMA care pathway (June 2017–May 2018).

cP value for difference between 2-year pre-period and post-period.

dP value for difference between 1-year pre-period and post-period.

*P < 0.05.

ERAS indicates enhanced recovery after surgery; MMA, multimodal analgesia.

Figure 1.

Overall multimodal analgesia (MMA) and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) compliance rates and opioid doses for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery from June 2016 to February 2019.

Table 3.

Interrupted time series analysis of changes in multimodal analgesia and enhanced recovery after surgery process measures before and after ERAS program implementation

| Variable | Pre-period slope |

P value | Pre to post difference |

P value | Post-period slope |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 year pre-perioda | ||||||

| MMA | 0.03 | <0.0001* | 0.08 | 0.22 | −0.06 | <0.0001* |

| ERAS | 0.01 | <0.0001* | 0.01 | 0.73 | −0.01 | 0.12 |

| 1 year pre-periodb | ||||||

| MMA | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.13 | 0.38 | −0.01 | 0.27 |

| ERAS | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.62 |

aIncludes patients receiving care in the 2 years prior to implementation of the MMA care pathway (June 2016–May 2018).

bIncludes patients receiving care in the 1 year prior to implementation of the MMA care pathway (June 2017–May 2018).

ERAS indicates enhanced recovery after surgery; MMA, multimodal analgesia.

We also observed significant changes in opioid prescribing practices between the pre- and post-periods (Table 4). The percentage of patients who received opioids before or after surgery decreased from 95.4% to 88.7% (P = 0.0002). The mean number of days that patients were on opioids decreased from 4.2 to 3.2 (P < 0.0001). We also observed statistically significant (P < 0.0001) reductions in the mean maximum daily MME (73.4 vs 46.7 mg), daily MME (51.6 vs 33.4 mg), and total MME given during hospitalization (125.5 vs 64.5 mg). The trends in opioid prescribing practices were similar for the 2-year pre-period (primary analysis) and the 1-year pre-period.

Table 4.

Differences in opioid utilization before and after enhanced recovery after surgery program implementation

| Variable | Prea: 2 years (N = 618) |

Preb: 1 year (N = 309) |

Post (N = 238) |

P valuec (2 years) |

P valued (1 year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients receiving opioids: n (%) | 590 (95.4%) | 293 (94.8%) | 211 (88.7%) | 0.0002* | 0.0002* |

| Number of days on opioids: mean (SD)e | 4.2 (3.1) | 3.9 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.3) | <0.0001* | <0.0013* |

| Number of days on opioids: median (IQR)e | 4 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | <0.0001* | 0.0002* |

| Maximum daily MME doses: mean (SD)e |

73.4 (60.6) | 61.5 (52.5) | 46.7 (35.9) | <0.0001* | 0.0002* |

| Maximum daily MME doses: median (IQR)e |

60 (30–100) | 48.5 (25–80) | 37.5 (20–67.5) | <0.0001* | 0.0022* |

| Daily MME dose: mean (SD)e | 51.6 (45.0) | 43.2 (39.1) | 33.4 (28.7) | <0.0001* | 0.0011* |

| Daily MME doses, median (IQR)e | 36.7 (20.0–74.0) | 31.0 (16.7–61.8) | 25.0 (11.9–47.1) | <0.0001* | 0.0064* |

| Total MME doses during hospitalization: mean (SD)e |

228.8 (352.1) | 172.9 (234.3) | 112.7 (152.5) | <0.0001* | 0.0005* |

| Total MME doses during hospitalization: median (IQR)e |

125.5 (55–270) | 104 (45–200) | 64.5 (27.5–132.5) | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

aIncludes patients receiving care in the 2 years prior to implementation of the multimodal analgesia care pathway (June 2016–May 2018).

bIncludes patients receiving care in the 1 year prior to implementation of the multimodal analgesia care pathway (June 2017–May 2018).

cP value for difference between 2-year pre-period and post-period.

dP value for difference between 1-year pre-period and post-period.

eFor patients receiving opioids.

* P < 0.05.

IQR indicates interquartile range; MME, morphine milligram equivalents; SD, standard deviation.

Unadjusted and risk-adjusted outcomes are displayed in Table 5. We observed a significant decrease in risk-adjusted LOS (4.3 vs 3.6 days, P < 0.05) following implementation of the ERAS program. We also found that ERAS program implementation was associated with a slight increase in the percentage of patients who were discharged home instead of to other care facilities (94.8% vs 95.5%) and a slight decrease in the percentage of patients experiencing ORADE (14.9% vs 13.0%). There was a slight increase in the percentage of patients who were readmitted within 30 days (8.9% vs 10.2%) The risk-adjusted mean cost of hospitalization decreased from $8357 to $8232. However, these differences were not statistically significant. Although we did not observe a statistically significant decrease in the mean cost of hospitalization, we observed statistically significant reductions in laboratory, pharmaceutical, and room costs. The trends in the unadjusted and risk-adjusted outcomes from the 1-year pre-period were similar to those in the primary analysis.

Table 5.

Unadjusted and risk-adjusted outcome measures before and after implementation of a multimodal analgesia care pathway as part of an enhanced recovery after surgery program

| Measure | Unadjusted outcomes |

Risk-adjusted outcomes |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prea: 2 years (N = 618) |

Preb: 1 year (N = 309) |

Post (N = 238) |

P valuec (2 years) |

P valued (1 year) |

Prea: 2 years (N = 618) |

Preb: 1 year (N = 309) |

Post (N = 238) |

Differencee (2 years) |

Differencef (1 year) |

|

| Length of stay (days)g | 4.3 (3.2) | 4.1 (3.1) | 3.4 (2.5) | <0.0001* | 0.003* | 4.3 (4.0–4.6) |

3.9 (3.7–4.2) |

3.6 (3.5–3.7) |

–0.7* | –0.3* |

| 30-day readmissionh | 56 (9.1) | 30 (9.7) | 23 (9.6) | 0.79 | 0.99 | 8.9 (6.7–11.6) |

9.4 (6.4–15.3) |

10.2 (6.5–15.3) |

1.3 | 0.8 |

| Inpatient mortalityh | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.2 (0.0–1.4) |

0 (0.0–0.0) |

0.2 (0.0–1.4) |

0 | 0.2 |

| Discharged homeh | 583 (94.3) | 583 (92.2) | 227 (95.4) | 0.55 | 0.12 | 94.8 (87.3–100.0) |

93.2 (82.8–100.0) |

95.5 (83.5–100.0) |

0.7 | 2.3 |

| ORADEh | 91 (14.7) | 91 (16.8) | 31 (13.0) | 0.52 | 0.21 | 14.9 (12.0–18.3) |

17.2 (12.8–22.5) |

13.0 (8.8–18.5) |

–1.9 | –4.2 |

| Total cost of hospitalization ($)g | 8426 (4269) | 8481 (4145) | 8112 (3602) | 0.28 | 0.27 | 8357 (8035–8665) | 8384 (8187–8765) | 8232 (7813–8549) | –125 | –152 |

| Lab costsg | 361 (431) | 350 (431) | 275 (230) | 0.003* | 0.02* | 356 (326–385) |

339 (293–399) |

293 (269–312) |

–63* | –46* |

| Pharmaceutical costsg | 476 (466) | 424 (464) | 357 (374) | 0.0001* | 0.03* | 468 (452–517) |

394 (364–417) |

371 (343–408) |

–97* | –23* |

| Room costsg | 1710 (1833) | 1531 (1554) | 1227 (1398) | <0.0001* | 0.01* | 1675 (1556–1767) |

1428 (1369–1544) |

1302 (1238–1348) |

–373* | –126* |

aIncludes patients receiving care in the 2 years prior to implementation of the multimodal analgesia care pathway (June 2016–May 2018).

bIncludes patients receiving care in the 1 year prior to implementation of the multimodal analgesia care pathway (June 2017–May 2018).

cP value for difference between 2-year pre-period and post-period.

dP value for difference between 1-year pre-period and post-period.

eDifference between 2-year pre-period and post-period.

fDifference between 1-year pre-period and post-period.

gData are presented as mean (standard deviation) for unadjusted outcomes and mean (95% confidence interval) for risk-adjusted outcomes.

hData are presented as n (%) for unadjusted outcomes and mean (95% confidence interval) for risk-adjusted outcomes.

*P < 0.05.

ORADE indicates opioid-related adverse drug events.

Patients who received a lower dose of opioids during their hospitalization were significantly more likely to be older (64.6 vs 56.3 years, P < 0.0001), female (56.3% vs 49.2%, P = 0.04), and have a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score (3.5 vs 2.9, P = 0.0009) (Table 6). They were significantly more likely (P < 0.0001) to be on Medicare (41.5% vs 28.5%) and less likely to be commercially insured (44.1% vs 68.3%). Patients who received lower doses of opioids had a significantly (P < 0.0001) higher mean compliance rate for MMA (47.8% vs 36.2%) and ERAS (53.3% vs 46.8%) measures and significantly shorter risk-adjusted LOS (3.7 vs 4.3 days, P < 0.05). Fewer patients with lower opioid doses experienced more ORADEs (11.1% vs 19.1%, P < 0.05) than patients with higher doses (Table 7). Patients who received a lower dose of opioids had a lower 30-day readmission rate (6.5% vs 12.2%), but this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 6.

Demographics and multimodal analgesia and enhanced recovery after surgery compliance rates of patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery by level of opioid use

| Variable | Opioid use |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lowa (N = 478) | Highb (N = 378) | P value | |

| Age (years): mean (SD) | 64.6 (12.3) | 56.3 (13.5) | <0.0001* |

| Sex (female): n (%) | 269 (56.3%) | 186 (49.21%) | 0.04* |

| BMI (kg/m2): mean (SD) | 28.9 (6.3) | 28.3 (6.3) | 0.15 |

| Race: n (%) | |||

| White | 443 (92.6%) | 339 (89.7%) | 0.08 |

| Black | 18 (3.7%) | 23 (6.1%) | |

| Asian | 4 (0.8%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Other | 13 (2.7%) | 13 (3.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 40 (8.3%) | 27 (9.5%) | 0.15 |

| Payer type: n (%) | |||

| Commercial | 211(44.1%) | 258 (68.3%) | <0.0001* |

| Medicare | 257 (41.5%) | 108 (28.5%) | |

| Others | 1 (0.2%) | 3 (0.8%) | |

| Self/uninsured | 6 (1.3%) | 9 (2.4%) | |

| ASA score: n (%) | |||

| 1 | 6 (1.3%) | 6 (1.6%) | 0.15 |

| 2 | 233 (48.7%) | 189 (50.0%) | |

| 3 | 213 (44.6%) | 174 (46.0%) | |

| ≥4 | 24 (5.0%) | 7 (1.9%) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| CCI: mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.7) | 0.0009* |

| Compliance: % | |||

| Overall MMA | 47.8% | 36.2% | <0.0001* |

| Overall ERAS | 54.7% | 49.4% | <0.0001* |

| MMA + ERAS | 53.3% | 46.8% | <0.0001* |

a≤112.7 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) during hospital stay, based on mean post-period opioid dose.

b>112.7 MME during hospital stay.

*P < 0.05.

ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ERAS, enhanced recovery after surgery; MMA, multimodal analgesia; SD, standard deviation.

Table 7.

Risk-adjusted outcomes by level of opioid use for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery

| Variable | Elective colorectal surgeries |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-adjusted mean (95% CI) |

Difference | ||

| Low opioid usea (N = 478) | High opioid useb (N = 378) | ||

| Length of stay (days) | 3.7 (3.6–3.9) | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 0.6* |

| 30-day readmission (%) | 6.5% (4.4–9.3) | 12.2% (9.1–16.1) | 5.7 |

| Inpatient mortality (%) | 0.2% (0.0–1.3) | 0.2% (0.0–1.3) | 0 |

| Discharged home (%) | 96.2% (87.5–100.0) | 93.6% (84.2–100.0) | 2.6 |

| ORADE (%) | 11.1% (8.3–14.4) | 19.1% (14.7–24.2) | 8.0* |

| Cost of hospitalization ($) | $8314 (8194–8494) | $8440 (8233–8649) | 126 |

| Lab costs | $301 (276–334) | $361 (265–327) | 60 |

| Pharmaceutical costs | $385 (351–410) | $478 (454–534) | 93* |

| Room costs | $1335 (1304–1368) | $1677 (1576–1795) | 342* |

a≤112.7 morphine milligram equivalents during hospital stay, based on mean post-period opioid dose.

b>112.7 morphine milligram equivalents during hospital stay.

*P < 0.05.

Discussion

We found that MMA and ERAS process measure adherence for colorectal surgery improved in the period following ERAS program implementation. Overall MMA compliance improved from 34.0% to 65.5%, and ERAS compliance improved from 50.4% to 57.6% in the 2-year preimplementation period compared to the 9-month post-implementation period. While overall compliance rates for these measures remained relatively low at the end of the study period, particularly for ERAS, the observed increases were statistically significant and were associated with improvements in some outcomes. The smaller increase in ERAS compliance relative to the increase in MMA compliance could be attributed to the greater number of measures contained with the ERAS bundle (16 vs 4) and the fact that the ERAS measures require adherence across a spectrum of care and health care providers, including nurses, surgeons, anesthesiologists, nutritionists, and physical therapists, while the four MMA measures focused on prescribing and use of regional anesthesia. Also, large improvements in MMA compliance were observed in the 2 years prior to study implementation as average adherence rates increased from 34.0% to 50.7%, likely due to various quality improvement efforts around opioid reduction. Given that adherence to these measures required a change in or standardization of practice for many care providers and compliance rates were only observed for 9 months following implementation, the relatively low increases in compliance are not surprising.

Program implementation was associated with significant changes in opioid prescribing practices, including reductions in the percentage of patients receiving opioids and mean number of days on opioids, maximum daily MME, and total MME during hospitalization. We also observed improvements in some outcomes, such as a statistically significant decrease in risk-adjusted LOS and nonsignificant reductions in ORADEs. We did not see a significant difference in total hospital costs; however, we did observe statistically significant reductions in risk-adjusted laboratory, pharmaceutical, and room costs. No significant differences in inpatient mortality or the percentage of patients discharged home instead of to other care facilities were observed.

The observed association between implementation of an ERAS program with an MMA component and significant reductions in opioid use is an important finding. While opioids are commonly used for postsurgical pain control, in-hospital opioid use has been linked to patient harm within hospitals and as a contributor to opioid addiction following hospitalization. In a previous study, we found that 10.6% of patients undergoing selected surgeries in our health care system experienced ORADEs, and ORADEs were associated with significantly worse clinical outcomes and higher costs of care.1 In the current study, we found that the risk-adjusted rate of ORADEs decreased from 14.9% to 13.0% in the post-period. Although this decrease was not statistically significant, the downward trend is encouraging, especially given that average MMA compliance only improved to 65.5%. Greater improvements in MMA compliance could help reduce ORADEs by statistically significant levels. We did find that patients who received lower opioid doses were significantly less likely to experience an ORADE (11.1% vs 19.1%, P < 0.05) compared to patients who received higher doses. In addition, patients who received lower opioid doses may have reduced risk of developing opioid addiction and future complications.

The implementation of the ERAS program also was associated with a significant decrease in risk-adjusted LOS, which likely contributed to observed decreases in laboratory, pharmaceutical, and room costs. The observed reductions in opioid prescribing may have also resulted in decreased pharmaceutical costs. Risk-adjusted overall costs of patient care did not change significantly, but this finding may be attributed to increases in other costs of care that were not related to ERAS and MMA implementation. The lack of observed improvements in inpatient mortality and the percentage of patients discharged home was not surprising given the extremely low rates of mortality and discharge to other care facilities. The lack of improvement in readmission rates is consistent with previous studies of ERAS for colorectal surgery, as most studies have found that readmission rates remained stable despite observed reductions in LOS.14–16 Other measures such as patient pain scores and nonsurgical complication rates may be better markers of effectiveness of MMA and ERAS programs. We did not have access to these measures.

Although MMA components are often included as part of ERAS bundles, few studies have examined the impact of adding MMA components to ERAS programs and how these types of programs may be implemented as part of routine care. A study conducted by Liu et al found that implementation of ERAS programs for elective colorectal surgery and hip fracture repair in 20 medical centers within the Kaiser Permanente Northern California integrated healthcare delivery system was associated with significantly greater adherence to most process measures and was associated with significant reductions in total MME, LOS, and postoperative complications for patients undergoing both types of procedures.17 Several other studies of ERAS implementation for elective colorectal surgeries have observed reductions in LOS and complications.15,18–21 This study provides further evidence that a system-level implementation of an ERAS program with a MMA component can improve adherence to these measures and may reduce opioid use and LOS.

This study has several limitations. It was not a randomized trial; implementation sites were selected based on readiness for implementation. We utilized a pre-post study design but did not have concurrent control groups. There were some improvements in colorectal MMA and ERAS process measures in the 18 months prior to ERAS program implementation likely due to the launch of a draft of an ERAS order set and various quality improvement efforts around opioid reduction. The effects of these and other unknown initiatives may have contaminated study findings, but we did see MMA and ERAS compliance improve following full-scale ERAS program implementation. The follow-up period was limited to 9 months due to a change in EHR systems, which likely prevented the observation of the full effects of implementation. We were unable to capture readmissions outside our health system, which may have caused readmission rates to be underestimated. We had a relatively small monthly sample size and were not able to account for differences in unobserved covariates. Improvements in measure adherence could be due to improvements in documentation rather than process adherence. Because the study population was limited to a few hospitals within a single health system, our results may not be generalizable.

Conclusion

Implementation of an ERAS program with an MMA component in a real-world health care delivery system was associated with improved adherence to MMA and ERAS process measures for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgeries. Although improvements in MMA and ERAS were observed prior to ERAS program implementation, likely due to the release of a draft of an ERAS order set and informal efforts to reduce opioid use, additional improvements in MMA and ERAS process measure adherence were achieved for patients undergoing colorectal surgery by using a structured, system-level strategy for driving uptake and improvement, including system and site champions, modifications to order sets and EHR documentation fields, patient and provider education, compliance dashboards, and monthly feedback on compliance rates to executive and clinical site leaders. Moderate improvements in ERAS and MMA compliance were associated with reductions in opioid use and LOS. Implementing ERAS programs that include MMA components can promote uptake of evidence-based practices and judicious opioid use and also improve recovery time, thus improving the safety and effectiveness of patient care. A structured, system-level approach may facilitate uptake of these programs. The reduction of in-hospital opioid use may also reduce patients’ risk of chronic opioid use and associated negative health outcomes.

Disclosure statement/Funding

Dr. Wan is the Global Head of Evidence Generation and Data Sciences at Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. Ms. Böing previously served as the Senior Manager for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (HEOR) and Real-World Evidence at Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals and is currently the Director of Global HEOR for Rare Disease at Ipsen. Dr. Collinsworth is currently a Senior Research Scientist at 3M. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shafi S, Collinsworth AW, Copeland LA, et al. Association of opioid-related adverse drug events with clinical and cost outcomes among surgical patients in a large integrated health care delivery system. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):757–763. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wick EC, Grant MC, Wu CL.. Postoperative multimodal analgesia pain management with nonopioid analgesics and techniques: a review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):691–697. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wardhan R, Chelly J.. Recent advances in acute pain management: understanding the mechanisms of acute pain, the prescription of opioids, and the role of multimodal pain therapy. F1000Res. 2017;6:2065. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12286.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elia N, Lysakowski C, Tramer MR.. Does multimodal analgesia with acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, or selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and patient-controlled analgesia morphine offer advantages over morphine alone? Meta-analyses of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(6):1296–1304. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDaid C, Maund E, Rice S, et al. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the reduction of morphine-related side effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. (Winchester, England). 2010;14(17):1–153. doi: 10.3310/hta14170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gritsenko K, Khelemsky Y, Kaye AD, et al. Multimodal therapy in perioperative analgesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2014;28(1):59–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelson JD, Addante RA, Charlson MD.. Multimodal analgesia therapy reduces length of hospitalization in patients undergoing fusions of the ankle and hindfoot. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(11):1526–1534. doi: 10.1177/1071100713496224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu VX, Rosas E, Hwang J, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery program implementation in 2 surgical populations in an integrated health care delivery system. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):e171032. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan M, Law LS, Gan TJ.. Optimizing pain management to facilitate enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. Can J Anaesthesia. 2015;62(2):203–218. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- 12.Epocrates . Opioid medication dose conversions. https://online.epocrates.com/medCalc/Opioid.htm?activeMedCalcName=Opioid%20Medication%20Dose%20Conversions%20(Epocrates%20data). Published 2019. Accessed May 2, 2019.

- 13.Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. Condition-specific measures updates and specifications report: hospital-level 30-day risk-standardized readmission measures. 2016.

- 14.Adamina M, Kehlet H, Tomlinson GA, et al. Enhanced recovery pathways optimize health outcomes and resource utilization: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in colorectal surgery. Surgery. 2011;149(6):830–840. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ban KA, Berian JR, Ko CY.. Does implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (eras) protocols in colorectal surgery improve patient outcomes? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(2):109–113. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv L, Shao YF, Zhou YB.. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing colorectal surgery: an update of meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(12):1549–1554. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu VX, Rosas E, Hwang JC, et al. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California enhanced recovery after surgery program: design, development, and implementation. Perm J. 2017;21:17–003. doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, et al. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1531–1541. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller TE, Thacker JK, White WD, et al. Reduced length of hospital stay in colorectal surgery after implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol. Anesthesia Analgesia. 2014;118(5):1052–1061. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teeuwen PH, Bleichrodt RP, Strik C, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) versus conventional postoperative care in colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(1):88–95. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiele RH, Rea KM, Turrentine FE, et al. Standardization of care: impact of an enhanced recovery protocol on length of stay, complications, and direct costs after colorectal surgery. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2015;220(4):430–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]