Abstract

Leishmania tarentolae promastigotes were selected step by step for resistance to sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam). Mutants resistant to antimony-containing drugs and cross-resistant to arsenite were therefore obtained. Amplification of one common locus was observed in several independent sodium stibogluconate-resistant mutants, and the locus amplified was novel. The copy number of the amplified locus was related to the level of resistance to pentavalent antimony. The gene responsible for antimony resistance was isolated by transfection and was shown to correspond to an open reading frame coding for 770 amino acids. The putative gene product did not exhibit significant homology with sequences present in data banks, and the putative role of this protein in antimony resistance is discussed.

The protozoan parasite Leishmania sp. is transmitted to humans by the sandfly. This parasite is found as a motile promastigote in the sandfly, and it transforms into an amastigote when engulfed by host macrophages. Leishmania is the causative agent of a group of diseases known as leishmaniasis. Chemotherapy is the only effective way to control infections, and the pentavalent antimony-carbohydrate complexes sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) and meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) are the mainstays against all forms of Leishmania infections (22). Although unresponsiveness to antimonial drugs has not always been attributed to drug resistance of the parasite, resistant parasites from patients who did not respond to therapy have been isolated (13, 16, 19, 20, 36).

Pentavalent antimony [Sb(V)] is likely to be a prodrug that is converted to a more toxic trivalent species (33). Although antimonial drugs have been used since approximately 1945, data on their chemical structures and biochemical targets are limited. Interaction of antimony with key sulfhydryl groups may be a major mechanism of action and/or toxicity. As pentavalent antimony drugs bind to several Leishmania proteins (1), it is indeed possible that Sb(V) has several targets. The available evidence does not exclude, however, binding to one main target (3). The systematic analysis of drug-resistant mutants should be useful in trying to delineate the drug target(s).

In order to try to understand metal metabolism and resistance mechanisms in Leishmania, we have selected several Leishmania species for resistance to sodium stibogluconate, to trivalent antimony, and to the related metal arsenite (28). The availability of arsenite (but not antimony) in a radioactive form has led to a more thorough analysis of arsenite-resistant mutants. The analysis of the arsenite-resistant mutant has revealed the importance of transport systems recognizing metals conjugated to glutathione or trypanothione (reviewed in reference 27). Mutants selected for resistance to arsenite were cross-resistant to antimony-containing drugs, and mutants selected for resistance to Sb(III) or Sb(V) were cross-resistant to arsenite (10). Mutants selected for antimony resistance exhibited an active efflux of arsenite (10), and sodium stibogluconate conjugated to glutathione was shown to compete the transport of arsenite-thiol conjugates in transport studies of everted membrane vesicles (9). There are, therefore, several similarities between arsenite and antimony resistance mechanisms in Leishmania. Nevertheless, some differences were apparent, such as amplification of the ABC transporter gene pgpA in arsenite-resistant L. tarentolae mutants but not in antimony-resistant mutants (10, 28). The characterization of L. tarentolae Sb(V)-resistant mutants has indicated the presence of a novel amplicon which was not observed in our arsenite-resistant mutants. This report deals with the analysis of the role of this novel amplicon in metal resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cultures.

The parental cell line L. tarentolae (TarIIWT) has been described previously (39). SbV200.1 to SbV200.10 are sodium stibogluconate-resistant mutants generated from the TarIIWT cell line in a step-by-step selection procedure involving sodium stibogluconate concentrations from 0.17 to 12 mM. SbV200.4rev is a revertant obtained by growing the mutant SbV200.4 in SDM-79 medium without sodium stibogluconate for several passages. Cells were grown in SDM-79 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 29°C. Growth curves of control strains and transfectants in the presence of drugs were obtained as described previously (23), with absorbance measured at 600 nm by using an automated microplate reader (Organon Teknica Microwell System [Reader 510]). Statistical analysis was performed by using Stat-View SE + Graphics 1988 (Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, Calif.). Statistical analysis of the difference between groups was performed by analysis of variance using a least-squares method. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant, and a group comparison was performed by using Fisher’s protected least-significant difference test.

DNA work.

Gel electrophoresis, chromosome separation using transverse alternating field electrophoresis (TAFE), and Southern blotting were done as described previously (18). Isolation of plasmid DNAs from Leishmania was done as described in detail elsewhere (24). DNA sequencing was performed on an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA automated sequencer. Sequence analysis was performed by using the Genetics Computer Group software package (1994 release). Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper are available in the EMBL GenBank and DDJB databases under accession no. AF047351. L. tarentolae promastigotes were transfected by electroporation as reported previously (32). Selection was done with 40 μg of G418 (GIBCO/BRL) ml−1 or with 100 μg of hygromycin (Calbiochem) ml−1.

RESULTS

Selection for sodium stibogluconate-resistant L. tarentolae mutants.

Resistance to Sb(V) has been induced in several Leishmania species in a step-by-step manner (10, 12, 14, 15, 37). Although Sb(V) is active against both stages in the life cycle of the parasite (33), Leishmania amastigotes are more sensitive to Sb(V) drugs (5, 19, 33). Sodium stibogluconate contains the preservative chlorocresol, and this compound seems to account for some of the activity of sodium stibogluconate against Leishmania promastigotes (12, 34). In this study, 10 L. tarentolae clones were selected in a step-by-step fashion for increased resistance to Sb(V) in the form of sodium stibogluconate. The growth of TarIIWT cells was inhibited by 50% at an Sb(V) concentration of 0.17 mM. The mutants were 70-fold more resistant than wild-type cells to the action of Sb(V) (Table 1 and data not shown). Mutants selected for resistance to sodium stibogluconate may be cross-resistant to chlorocresol (12, 34). However, none of our mutants were cross-resistant to chlorocresol (Table 1; data not shown). The mutants selected for sodium stibogluconate resistance were also cross-resistant to meglumine antimoniate, to antimony tartrate [Sb(III)], and to arsenite but not to cadmium (Table 1). Preservatives were absent in the latter drugs, showing that L. tarentolae mutants studied here were indeed resistant to related metals.

TABLE 1.

Resistance to metals in mutants and transfectants

| Cell line | Resistance toa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium stibogluconate (μg/ml) | Meglumine antimoniate (μg/ml) | Sb(III) (nM) | As (nM) | Cresol (‰) | Cd (μM) | |

| TarIIWT | 37 ± 3 (1) | 266 ± 11 (1) | 166 ± 6 (1) | 418 ± 18 (1) | 5 ± 0.1 (1) | 100 ± 4 (1) |

| TarIISbV200.4 | 2,600 ± 45 (70) | 25,000 ± 35 (100) | 25,000 ± 59 (150) | 12,000 ± 67 (30) | 5 ± 0.2 (1) | 100 ± 6 (1) |

| TarIISbV200.4rev | 169 ± 9 (5) | NDb | ND | ND | 5 ± 0.2 (1) | 100 ± 8 (1) |

| TarIISbV200.7 | 2,600 ± 71 (70) | 25,000 ± 55 (100) | 25,000 ± 69 (150) | 12,000 ± 76 (30) | ND | ND |

| TarII-Ω-Bam | 92 ± 2 (2.5)c | 710 ± 36 (2.7)c | 333 ± 20 (2)c | 830 ± 17 (2)c | 5 ± 0.2 (1) | 100 ± 5 (1) |

| TarII-Ω-Kpn | 97 ± 1 (2.6)c | 730 ± 10 (2.7)c | 371 ± 10 (2.2)c | 855 ± 21 (2)c | 5 ± 0.3 (1) | 100 ± 6 (1) |

EC50s are given as means ± standard deviations. Fold increases compared to TarIIWT are given in parentheses.

ND, not determined.

Resistance level observed in this transfectant is statistically different from that in wild-type cells (P < 0.01).

Gene amplification in Sb(V)-resistant mutants.

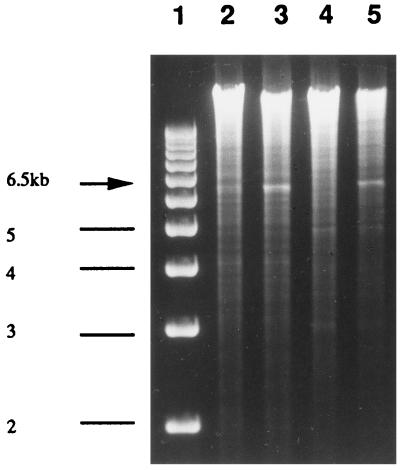

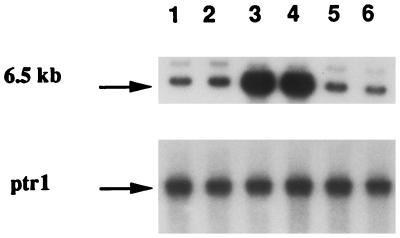

Gene amplification is a frequent mechanism by which Leishmania resists the action of cytotoxic drugs (2, 3), and several amplicons have been observed in arsenite-resistant mutants (8, 18, 21, 25, 35). The detection of amplicons in Leishmania is facilitated by the low complexity of its genome, and this can usually be achieved by comparing digested DNA run on agarose gel stained by ethidium bromide (6, 24). Comparison of DNA derived from a wild-type cell and TarIISbV200.4 digested with BglII revealed an amplified band of 6.5 kb in the mutant that was absent in the wild-type cell (Fig. 1). This amplified band was cloned and used as a probe to look at amplification of this locus in other mutants. Out of 10 mutants selected for Sb(V) resistance, 6 had the same locus amplified (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4, and data not shown). In some mutants, like TarIISbV200.7 (Fig. 2, lane 2), this locus was not amplified. Amplification of this novel locus was also not observed in mutants selected for resistance to arsenite or to trivalent antimony (Fig. 2, lanes 5 and 6). The arsenite-resistant mutant TarIIAs20.3 contains two amplicons encoding pgpA and the γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase gene gsh1, respectively (17), but the probe derived from the amplicon present in TarIISbV200.4 did not recognize these two amplicons (Fig. 2, lane 5), suggesting that the locus amplified in several Sb(V)-resistant mutants is unrelated to the amplified regions already characterized.

FIG. 1.

Detection of gene amplification in TarSbV200.4. Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel containing molecular weight markers (lane 1), TarIIWT total DNA digested by BamHI (lane 2), TarIISbV200.4 total DNA digested by BamHI (lane 3), TarIIWT total DNA digested by BglII (lane 4), and TarIISbV200.4 total DNA digested by BglII (lane 5). The 6.5-kb amplified band in lanes 3 and 5 is indicated by an arrow.

FIG. 2.

Novel gene amplification in L. tarentolae sodium stibogluconate resistant mutants. DNAs were digested with BamHI, run on an agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized to the amplified fragment isolated from TarIISbV200.4. Lanes: 1, TarIIWT; 2, TarIISbV200.7; 3, TarIISbV200.3; 4, TarIISbV200.4; 5, TarIIAs20.3; and 6, TarSbIII20.3.

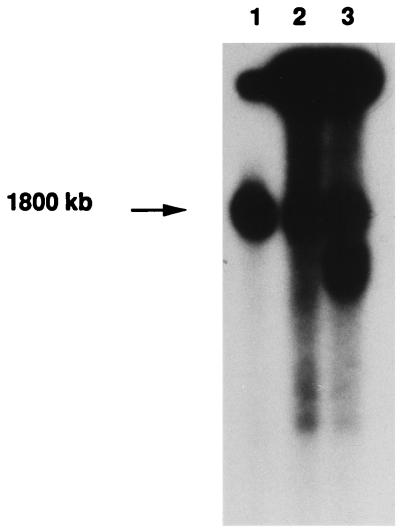

The novelty of this amplicon was further confirmed by hybridization of a TAFE blot, on which Leishmania chromosomes were resolved. The novel locus amplified is derived from a large chromosome (Fig. 3, lane 1), which differs from the pgpA (800 kb)- and gsh1 (760 kb)-containing chromosomes. The locus was amplified as part of extrachromosomal circles in mutants TarIISbV200.3 and TarIISbV200.4 (Fig. 3, lanes 2 and 3) as indicated by their characteristic migration in TAFE gels, with the long smears corresponding to various topoisomers (39). The circular nature of the amplicons was further demonstrated by our ability to isolate them by standard alkaline lysis procedures (24). The isolated circle was estimated to be more than 100 kb by its migration in agarose gel, but its digestion with BglII (or BamHI) consistently yielded a prominent 6.5-kb fragment, suggesting that the amplicon is constituted mainly of several tandem repeats of a short genomic region.

FIG. 3.

Chromosome localization of the resistance gene present on the novel amplicon. Leishmania chromosomes were separated on 1% agarose gel by TAFE, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized to the probe localized between the BglII-XhoI restriction sites (see Fig. 5). Lanes: 1, TarIIWT; 2, TarSbV200.3; and 3, TarSbV200.4.

Role of amplicon in resistance.

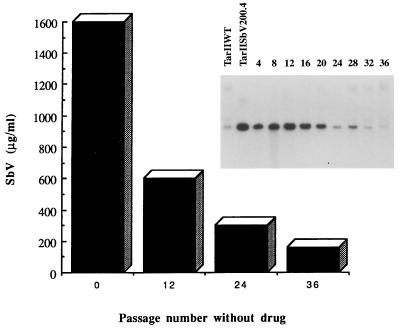

The mutant TarIISbV200.4 was grown in the absence of Sb(V) for several passages, with the copy number of the amplicon decreasing steadily (Fig. 4), and after 36 passages gene amplification could not be detected by hybridization. Concomitant with the loss of the amplicon there was a marked decrease in the resistance level to Sb(V) (Fig. 4), hence circumstantially linking the amplicon to resistance. Resistance did not, however, revert to wild-type levels (Table 1), showing that a stable mutation, unrelated to the described amplicon, also contributes to resistance. The role of this amplicon in resistance was tested more directly by cloning the 6.5-kb BamHI-BamHI fragment into the Leishmania expression vector pSPYneo (31). Transfection of this construct in Leishmania wild-type cells, leading to TarII-Ω-Bam cells, was sufficient to confer resistance to antimony-containing drugs and arsenite but not to cadmium (Table 1). The increase in the 50% effective concentration (EC50) was two- to threefold, depending on the metal (Table 1), and similarly, the 90% inhibitory concentrations were two- to threefold higher in the transfectants than in the wild-type cells (not shown). However, the construct could not yield the resistance levels found in mutants, suggesting that this amplicon contributes to resistance, but other (unstable) mutations are also present in the same mutant and are lost during reversion.

FIG. 4.

Reversion of drug resistance in TarIISbV200.4. The mutant was grown in the absence of Sb(V) for up to 36 passages. The copy number of the amplicon was measured by Southern blot analysis at every four passages (inset) by using the probe localized between the BglII-XhoI restriction sites (see Fig. 5). The hybridization signal was normalized by hybridization to the unrelated probe ptr1 (not shown). Resistance to sodium stibogluconate was measured at selected passages. The bars represent EC50s.

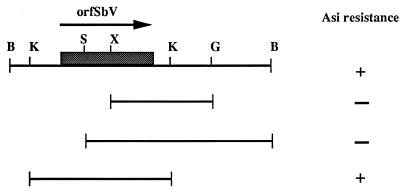

Restriction mapping of the fragment was performed, but by standard subcloning we did not succeed in reducing the size of the fragment involved in resistance (Fig. 5). Nucleotide sequencing of the 6.5-kb DNA fragment (accession no. AF047351) was undertaken. Sequence analysis revealed several putative open reading frames encoding more than 200 amino acids, but none of these had significant similarities with sequences present in data banks (data not shown). The longest open reading frame encoded 770 amino acids (Fig. 6) and is called orfSbV in this work. Sequence analysis has indicated that orfSbV is located between two KpnI sites (Fig. 5). Subcloning of this KpnI-KpnI fragment into a Leishmania expression vector and its transfection to lead to TarII-Ω-Kpn led to the same level of resistance as transfection of the whole 6.5-kb fragment (Table 1), indicating that orfSbV is the gene involved in metal resistance. The putative gene product of orfSbV does not exhibit significant homology with any sequence present in data banks, and its analysis did not convincingly support the presence of putative transmembrane domains or of any other structural features that may suggest how it confers resistance.

FIG. 5.

Restriction map and subcloning of the amplified 6.5-kb BamHI fragment. A restriction map was made and subclones were transfected in Leishmania cells to delimit the resistance gene. The KpnI sites were mapped after sequence analysis. The presence (+) or absence (−) of resistance to arsenite (Asi) was determined. Abbreviations for restriction sites: B, BamHI; G, BglII; K, KpnI; S, SmaI; and X, XhoI.

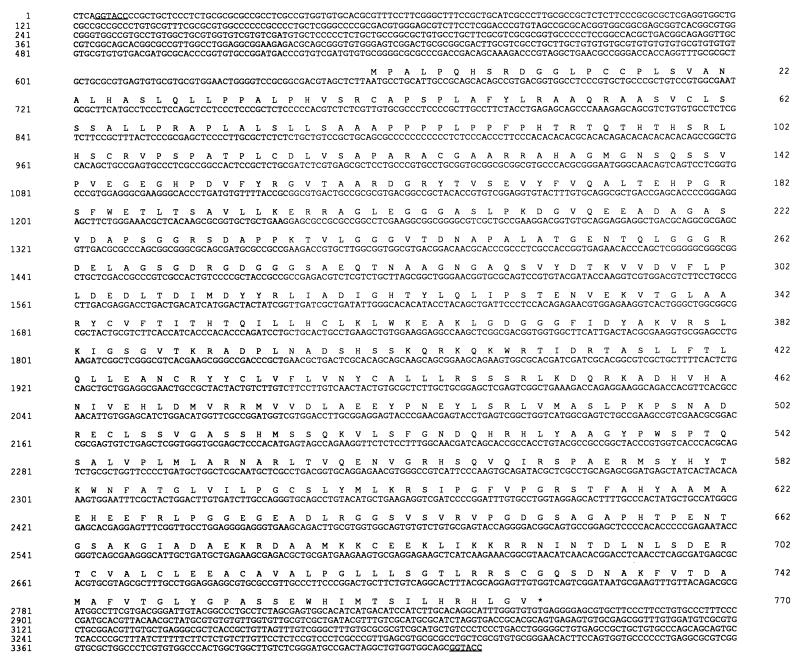

FIG. 6.

Nucleotide sequence of OrfSbV. The nucleotide sequence of the KpnI-KpnI fragment is shown (restriction sites are underlined). The amino acids corresponding to the open reading frame are indicated in single-letter code. The sequence can be found in the data bank under accession no. AF047351.

DISCUSSION

Sb(V) is the drug of choice against Leishmania, and resistance to it has fortunately been slow to arise. This is consistent with the hypothesis that several mutations are required for the emergence of resistance (21). However, several resistant strains have now been documented (13, 16, 19, 20, 36), and it is anticipated that resistance will increase further (26), especially in L. donovani, for which humans are a significant reservoir of the parasite. An increase in resistance to Sb(V) may lead to therapeutic failure, and few alternatives are available, hence the importance of understanding mechanisms of resistance. Several investigators have selected Leishmania mutants for studies of resistance to antimonial drugs (10, 12, 14, 15, 19, 37). Amplification of the ABC transporter gene pgpA has been reported in one Sb(V) resistant mutant (14). The role of PgpA in metal resistance has been studied by gene transfection (4, 17, 30). Depending on the species into which pgpA is transfected, resistance to Sb(V) could be detected (21). Although pgpA amplification is frequent in arsenite-resistant mutants (18), it was not observed in our L. tarentolae Sb(V) mutant. Instead a novel amplicon was characterized.

A novel resistance gene present on this amplicon was isolated by gene transfection. The gene product of orfSbV does not show significant homology to other proteins in the data banks. This is not unexpected, as ongoing genome projects are revealing that nearly 50% of the parasite genes will not match homologs in other kingdoms (7, 11, 38). Unfortunately, this lack of homology does not provide insights on the mechanism of resistance. Efflux seems unlikely, since no clear transmembrane domains are present in orfSbV, but we cannot exclude the possibility that orfSbV associates with a membrane protein. Binding of antimony by vicinal thiols (Fig. 6, amino acids 15 and 16) is also unlikely, as cross-resistance to cadmium would be anticipated and neither the mutants nor the transfectants are cadmium cross-resistant (Table 1). Clearly, further work is required to establish the biochemical mechanism of resistance. Nevertheless, amplification of orfSbV has been observed in several independent mutants, suggesting that its gene product is part of an important pathway leading to resistance. Transfection of orfSbV does not yield the resistance levels found in mutants, suggesting that several genes are involved in resistance. This is consistent with the step-by-step selection procedure used to generate the mutants. Our analysis of arsenite resistant mutants has indeed indicated that several genes, some of which act in synergy, are involved in resistance (27). It remains to be seen whether the orfSbV product, along with other gene products, is capable of conferring resistance in an additive or synergistic fashion.

The lack of cross-resistance to cresol in L. tarentolae mutants (Table 1) is also worth discussing. L. donovani and L. mexicana promastigotes selected for Sb(V) resistance were found to be cross-resistant to cresol, and part of the activity of Sb(V) against Leishmania parasites was attributed to cresol (34). It has been shown, however, that amastigotes are more sensitive to Sb(V) than promastigotes, although the fold difference varied from 5 to 200, depending on the species (5, 12, 33). L. tarentolae is hypersensitive to metals, being 10- to 100-fold more sensitive than pathogenic species (21). This differential susceptibility may be explained in part by a less active endogenous efflux system in L. tarentolae (21). The natural host of L. tarentolae is the lizard, and the parasites likely circulate mainly as promastigotes in the bloodstream (40). This parasite has the capacity to transform into an amastigote, but it is not capable of surviving within mammalian macrophages (29, 40). Although highly speculative, it is possible that L. tarentolae, due to its life cycle, has acquired some amastigote-like characteristics. This may explain its hypersensitivity to metals and why Sb(V)-selected mutants are resistant to metal and not to cresol. Alternatively, the concentration of cresol present in our Sb(V) preparation may be detoxified more readily in L. tarentolae than in other species. In summary, antimony-resistant Leishmania was generated and a novel gene contributing to resistance was isolated. Further work is required to understand the biochemical mechanism of this resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a group grant in Infectious Diseases from the Medical Research Council to M.O. M.O. was a Chercheur Boursier Junior II of the FRSQ, is now supported by an MRC Scientist award, and is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Fund New Investigator Award in Molecular Parasitology.

We thank M. Grögl (Walter Reed) and J.-P. Papin (Rhône-Poulenc Rorer) for the generous gift of sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate, respectively. We thank B. Papadopoulou (CHUL) for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berman J D, Grogl M. Leishmania mexicana: chemistry and biochemistry of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) Exp Parasitol. 1988;67:96–103. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(88)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beverley S M. Gene amplification in Leishmania. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:417–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borst P, Ouellette M. New mechanisms of drug resistance in parasitic protozoa. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:427–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan H L, Beverley S M. Heavy metal resistance: a new role for P-glycoproteins in Leishmania. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18427–18430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callahan H L, Portal A C, Devereaux R, Grogl M. An axenic amastigote system for drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:818–822. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coderre J A, Beverley S M, Schimke R T, Santi D V. Overproduction of a bifunctional thymidylate synthetase-dihydrofolate reductase and DNA amplification in methotrexate-resistant Leishmania tropica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2132–2136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dame J B, Arnot D E, Bourke P F, Chakrabarti D, Christodoulou Z, Coppel R L, Cowman A F, Craig A G, Fischer K, Foster J, Goodman N, Hinterberg K, Holder A A, Holt D C, Kemp D J, Lanzer M, Lim A, Newbold C I, Ravetch J V, Reddy G R, Rubio J, Schuster S M, Su X Z, Thompson J K, Werner E B, et al. Current status of the Plasmodium falciparum genome project. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;79:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detke S, Katakura K, Chang K P. DNA amplification in arsenite-resistant Leishmania. Exp Cell Res. 1989;180:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey S, Ouellette M, Lightbody J, Papadopoulou B, Rosen B P. An ATP-dependent As(III)-glutathione transport system in membrane vesicles of Leishmania tarentolae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2192–2197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dey S, Papadopoulou B, Haimeur A, Roy G, Grondin K, Dou D, Rosen B P, Ouellette M. High level arsenite resistance in Leishmania tarentolae is mediated by an active extrusion system. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;67:49–57. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.el-Sayed N M, Alarcon C M, Beck J C, Sheffield V C, Donelson J E. cDna expressed sequence tags of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense provide new insights into the biology of the parasite. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;73:75–90. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00098-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ephros M, Waldman E, Zilberstein D. Pentostam induces resistance to antimony and the preservative chlorocresol in Leishmania donovani promastigotes and axenically grown amastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1064–1068. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraut-Gambarelli F, Piarroux R, Deniau M, Giusiano B, Marty P, Michel G, Faugere B, Dumon H. In vitro and in vivo resistance of Leishmania infantum to meglumine antimoniate: a study of 37 strains collected from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:827–830. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira-Pinto K C, Miranda-Vilela A L, Anacleto C, Fernandes A P, Abdo M C, Petrillo-Peixoto M L, Moreira E S. Leishmania (V.) guyanensis: isolation and characterization of glucantime-resistant cell lines. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:944–949. doi: 10.1139/m96-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grogl M, Oduola A M, Cordero L D, Kyle D E. Leishmania spp.: development of pentostam-resistant clones in vitro by discontinuous drug exposure. Exp Parasitol. 1989;69:78–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grogl M, Thomason T N, Franke E D. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis: its implication in systemic chemotherapy of cutaneous and mucocutaneous disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:117–126. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grondin K, Haimeur A, Mukhopadhyay R, Rosen B P, Ouellette M. Co-amplification of the gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase gene gsh1 and of the ABC transporter gene pgpA in arsenite-resistant Leishmania tarentolae. EMBO J. 1997;16:3057–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grondin K, Papadopoulou B, Ouellette M. Homologous recombination between direct repeat sequences yields P-glycoprotein containing amplicons in arsenite resistant Leishmania. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1895–1901. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.8.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibrahim M E, Hag-Ali M, el-Hassan A M, Theander T G, Kharazmi A. Leishmania resistant to sodium stibogluconate: drug-associated macrophage-dependent killing. Parasitol Res. 1994;80:569–574. doi: 10.1007/BF00933004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson J E, Tally J D, Ellis W Y, Mebrahtu Y B, Lawyer P G, Were J B, Reed S G, Panisko D M, Limmer B L. Quantitative in vitro drug potency and drug susceptibility evaluation of Leishmania spp. from patients unresponsive to pentavalent antimony therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:464–480. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Légaré D, Papadopoulou B, Roy G, Mukhopadhyay R, Haimeur A, Dey S, Grondin K, Brochu C, Rosen B P, Ouellette M. Efflux systems and increased trypanothione levels in arsenite-resistant Leishmania. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:275–282. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olliaro P L, Bryceson A D M. Practical progress and new drugs for changing patterns of leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:323–328. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouellette M, Fase-Fowler F, Borst P. The amplified H circle of methotrexate-resistant leishmania tarentolae contains a novel P-glycoprotein gene. EMBO J. 1990;9:1027–1033. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouellette, M., A. Haimeur, K. Grondin, D. Légaré, and B. Papadopoulou. Amplification of the ABC transporter gene pgpA and of other metal resistance genes in leishmania tarentolae and their study by gene transfection and gene disruption. In S. V. Ambudkar and M. M. Gottesman (ed.), Methods in enzymology. ABC transporters: biochemical, cellular, and molecular aspects, in press. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ouellette M, Hettema E, Wust D, Fase-Fowler F, Borst P. Direct and inverted DNA repeats associated with P-glycoprotein gene amplification in drug resistant Leishmania. EMBO J. 1991;10:1009–1016. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouellette M, Kündig C. Microbial multidrug resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1997;8:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(96)00370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouellette M, Légaré D, Haimeur A, Grondin K, Roy G, Brochu C, Papadopoulou B. ABC transporters in Leishmania and their role in drug resistance. Drug Res Updates. 1998;1:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(98)80213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellette M, Papadopoulou B, Haimeur A, Grondin K, Leblanc É, Légaré D, Roy G. Transport of antifolates and antimonials in drug-resistant Leishmania. In: Georgopapadakou N, editor. Drug transport and resistance in antimicrobial and anticancer chemotherapy. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1995. pp. 377–402. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papadopoulou B, Roy G, Dey S, Rosen B P, Olivier M, Ouellette M. Gene disruption of the P-glycoprotein related gene pgpa of Leishmania tarentolae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:772–778. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papadopoulou B, Roy G, Dey S, Rosen B P, Ouellette M. Contribution of the Leishmania P-glycoprotein-related gene ltpgpA to oxyanion resistance. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11980–11986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papadopoulou B, Roy G, Ouellette M. Autonomous replication of bacterial DNA plasmid oligomers in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;65:39–49. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadopoulou B, Roy G, Ouellette M. A novel antifolate resistance gene on the amplified H circle of Leishmania. EMBO J. 1992;11:3601–3608. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts W L, Berman J D, Rainey P M. In vitro antileishmanial properties of tri- and pentavalent antimonial preparations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1234–1239. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts W L, Rainey P M. Antileishmanial activity of sodium stibogluconate fractions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1842–1846. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.9.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh A K, Liu H Y, Lee S T. Atomic absorption spectrophotometric measurement of intracellular arsenite in arsenite-resistant Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;66:161–164. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundar S, Singh V P, Sharma S, Makharia M K, Murray H W. Response to interferon-gamma plus pentavalent antimony in Indian visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1117–1119. doi: 10.1086/516526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ullman B, Carrero-Valenzuela E, Coons T. Leishmania donovani: isolation and characterization of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam)-resistant cell lines. Exp Parasitol. 1989;69:157–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan K L, Blackwell J M, Ajioka J W. Toxoplasma gondii expressed sequence tags: insight into tachyzoite gene expression. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;75:179–186. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White T C, Fase-Fowler F, van Luenen H, Calafat J, Borst P. The H circles of Leishmania tarentolae are a unique amplifiable system of oligomeric DNAs associated with drug resistance. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16977–16983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson V C L C, Southgate B A. Lizard leishmania. In: Lumsden W H, Evans D A, editors. Biology of the Kinetoplastida. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 244–268. [Google Scholar]