Abstract

Objectives

The presentation and outcomes of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) during COVID times (June 2020 to Dec 2020) were compared with the historical control during the same period in 2019.

Methods

Data of 4806 consecutive patients of acute HF admitted in 22 centres in the country were collected during this period. The admission patterns, aetiology, outcomes, prescription of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) and interventions were analysed in this retrospective study.

Results

Admissions for acute heart failure during the pandemic period in 2020 decreased by 20% compared to the corresponding six-month period in 2019, with numbers dropping from 2675 to 2131. However, no difference in the epidemiology was seen. The mean age of presentation in 2019 was 61.75 (±13.7) years, and 59.97 (±14.6) years in 2020. There was a significant decrease in the mean age of presentation (p = 0.001). Also. the proportion of male patients decreased significantly from 68.67% to 65.84% (p = 0.037). The in-hospital mortality for acute heart failure did not differ significantly between 2019 and 2020 (4.19% and 4.,97%) respectively (p = 0.19). The proportion of patients with HFrEF did not change in 2020 compared to 2019 (76.82% vs 75.74%, respectively). The average duration of hospital stay was 6.5 days.

Conclusion

The outcomes of ADHF patients admitted during the Covid pandemic did not differ significantly. The length of hospital stay remained the same. The study highlighted the sub-optimal use of GDMT, though slightly improving over the last few years.

Keywords: COVID-19, Acute heart failure, Acute decompensated heart failure, GDMT in heart failure

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged as a global health emergency and adversely affected the healthcare systems. Multiple measures were adopted to curtail the spread of the virus, including implementing stringent lockdowns, and the focus of health care shifted to limit the direct effects of the virus. During this period, the non-covid health care facilities, including acute cardiovascular care, were adversely affected in India and across the globe.1,2 Acute heart failure is a medical emergency requiring urgent recognition, hospital admission, relevant investigations, and necessary management. Patients with heart failure hospitalised with COVID-19 infection had worse outcomes, with studies showing up to 25% mortality.3,4 COVID-19 pandemic also affected the admission patterns and outcomes of patients with acute cardiovascular emergencies, especially acute myocardial infarction all over the world including India.2 During the pandemic, heart failure services were significantly affected across the globe, with developed nations showing a decrease in heart failure hospitalisations and some studies suggesting worse outcomes.5, 6, 7, 8 Previous studies from our country in the non-COVID times have shown several deficiencies in acute heart failure care with sub-optimal use of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) and higher mortality compared to Western countries.9,10

The knowledge of the impact of COVID-19 on heart failure management in low- and middle-income countries, including India, is limited. An earlier study from South India showed a significant reduction in hospitalisations but no overall change in demographics, aetiology, and outcomes.16 However, only a limited number of centres were in that study. Moreover, this was conducted during the early phase of the pandemic. We hypothesised that access to care and quality of heart failure management may have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to an increase in morbidity and mortality. With this background, the Cardiological Society of India (CSI) initiated a study to quantify the impact of COVID-19 on heart failure hospitalisation and outcome across the country.

2. Methods

In this multicentric, retrospective, cross-sectional registry, we included consecutive patients (aged>18 years) presenting with acute HF at various participating hospitals across the country during a 6 months period in 2020 (1st of July to 31st of December 2020). All cases of acute HF admitted during the corresponding period in 2019 served as historical controls. Only the patients who tested Covid negative were included in the study. The 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria were used to define HF.11 Patients with acute myocardial infarction in the preceding two weeks were excluded. Patients with alternative diagnoses causative of symptoms were also excluded. The parameters studied included demographics, type of HF, lab investigations, echocardiography management strategy and outcomes (Appendix 1).

A steering committee designed the study and prepared the proforma. Dedicated software was used to capture the data. All the leading hospitals in the government and private set-up were invited to participate through the state chapters of CSI. Only those centres which gave an institutional ethics committee clearance were included. All centres were given training through the virtual platform. The individual site investigators entered the data into a dedicated electronic case record form, which was password protected and thus, privacy was ensured. Corrections of the data by the site investigator were allowed only for 1 week after entry. A coordinating centre in Kerala monitored the study. Periodic meetings of the investigators were done for clarifications of data entry. The source monitoring was randomly done to ensure the quality of the entered data.

The study was prospectively registered with the Clinical Trial Registry of India CTRI/2021/04/032864 [Registered on: 16/04/2021] The study was conducted as per the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) collaborative study- and Good Clinical Practice (GCP)- guidelines. All the state coordinators were encouraged to complete the GCP certification process.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical as numbers and percentages. To compare the COVID and non-COVID years, a two-sample test with equal variance was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-Square was used for categorical variables.

3. Results

We included 4806 patients of acute HF in our study from 22 centres and 11 states. The majority 3240 (67.4%)] were male, and the mean age was 60.96 ± 14.1 years. The proportion of HFrEF was 76.2%,. (Table 1). 9.3% of patients had atrial fibrillation at presentation. The in-hospital mortality was 4.5%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Total patients | 2019 | 2020 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 60.96 (14.1) | 61.75 (13.7) | 59.97 (14.6) | 0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 3240 (67.42) | 1837 (68.67) | 1403 (65.84) | 0.037 |

| HF classification at admission, n (%) | 0.382 | |||

| HFrEF | 3663 (76.22) | 2026 (75.74) | 1637 (76.82) | |

| HFpEF | 1143 (23.78) | 649 (24.26) | 494 (23.18) |

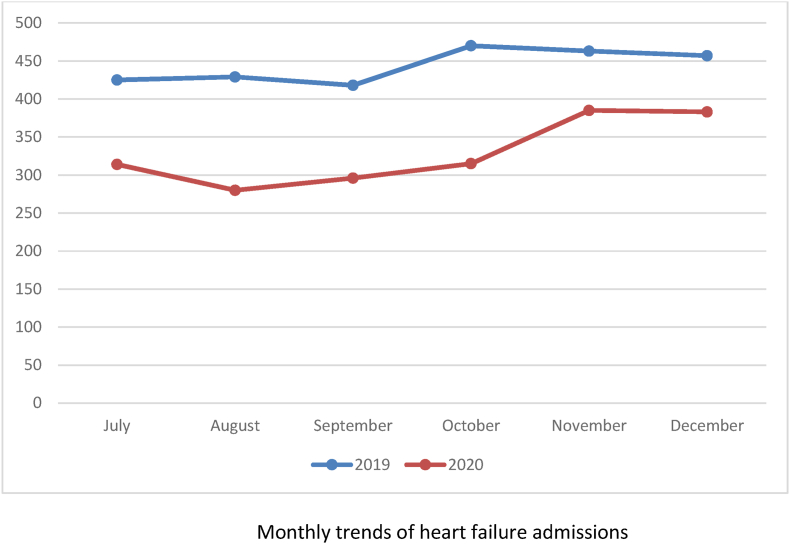

Admissions for acute heart failure during the pandemic period in 2020 decreased by 20% compared to the corresponding six-month period in 2019, with numbers dropping from 2675 to 2131 (Fig. 1). There was a significant decrease in the mean age of presentation during the pandemic period (59.97 ± 14.6 years in 2020 versus 61.75 + 13.7 years in 2019 (p = 0.001). Also, the proportion of male patients decreased significantly from 68.67% to 65.84% (p = 0.037). The in-hospital mortality for acute heart failure did not differ significantly between 2019 and 2020 (4.19% and 4.97%) respectively (p = 0.19). The proportion of patients with HFrEF did not change in 2020 compared to 2019 (76.82% vs 75.74%, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Monthly trends of Heart failure cases.

Coronary artery disease remained the most important aetiological factor for heart failure with 63% of patients. Dilated cardiomyopathy (20%) and valvular heart disease (10%) were the other aetiologies of heart failure. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Aetiology of heart failure in 2019 & 2020.

| Total n (%) | 2019 n (%) | 2020 n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary Artery Disease | 2447 (51.14) | 1392 (52.25) | 1055 (49.74) | |

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy | 832 (17.39) | 492 (16.03) | 340 (17.39) | |

| Valvular Heart Disease | 299 (6.25) | |||

| Hypertensive Heart Disease | 58 (1.21) | 38 (0.94) | 20 (1.21) | |

| Congenital Heart Disease | 34 (0.71) | 22 (0.57) | 12 (0.71) | |

| Myocarditis | 24 (0.50) | 18 (0.68) | 6 (0.28) |

The aetiological factors for heart failure over the two years did not differ significantly and the relative proportions remained nearly the same despite the decrease in overall number.

The average number of days in the hospital did not differ significantly during the two time periods (6.6 days vs 6.5 days).

Nearly 30% of patients had a history of recent ACS, and a diagnostic coronary angiogram was performed in 40.4% of patients and a PCI in 19.2%. The proportion of patients with recent ACS did not differ in the two time periods (29.35% in 2019 vs 29.14% in 2020) p = 0.87. Also, there was no significant difference in the number of diagnostic coronary angiograms performed (40.07% vs 40.78%). Surprisingly, the proportion of patients undergoing a PCI increased in 2020 (20.7%) as compared to 2019 (17.9%; p = 0.018). The number of coronary artery bypass surgeries performed was 5.72%, which did not differ significantly between the two periods (Fig. 2). The proportion of patients presenting with cardiogenic shock was 7.41% which also remained the same during the pandemic year (7.03% vs 7.88%) p = 0.26. (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of different interventions in 2019 vs 2020.

Table 3.

Outcomes, complications and interventions in heart failure.

| Length of stay (days) | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 0.09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In hospital mortality, n (%) | 218 (4.54%) | 112 (4.19%) | 106 (4.97%) | 0.19 |

| Recent ACS | 1406 (29.26) | 785 (29.35) | 621 (29.14) | 0.877 |

| Coronary Angiography | 1941 (40.39) | 1072 (40.07) | 869 (40.78) | 0.621 |

| PTCA | 992 (19.18) | 481 (17.98) | 441 (20.69) | 0.018 |

| CABG | 275 (5.72) | 160 (5.98) | 115 (5.40) | 0.386 |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 356 (7.41) | 188 (7.03) | 168 (7.88) | 0.261 |

| Malignant Ventricular Arrhythmia | 226 (4.70) | 128 (4.79) | 98 (4.60) | 0.762 |

3.1. Treatment patterns

The GDMT prescribed included loop diuretics (81.48%), ACEI (41.03%), ARNI(6.99%), ARB (11.53%), beta-blockers (64.69%) MRA (63.73%), SGLT2 inhibitors (3.18%), Ivabradine (15.96%), Digoxin (16.06%) and Inotropes (30.34%).

During the COVID pandemic, there was a decrease in the use of loop diuretics from 82.54% in 2019 to 80.15% in 2020 (p = 0.034) and ACE I [from 42.58% to 39.09% (p = 0.015)] and increase in the use of SGLT2 Inhibitors from 2.73% to 3.75%. There was no significant variation in the use of ARB, MRA, ARNI, Ivabradine, Digoxin and Inotropes. (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of heart failure medications in 2019 vs 2020.

| Medication/Intervention | Total n (%) | 2019 n (%) | 2020 n (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loop Diuretic | 3916 (81.48) | 2208 (82.54) | 1708 (80.15) | 0.034 |

| ACEI | 1972 (41.03) | 1139 (42.58) | 833 (39.09) | 0.015 |

| Beta Blocker | 3109 (64.69) | 1733 (64.69) | 1376 (64.57) | 0.877 |

| ARB | 554 (11.53) | 329 (12.30) | 225 (10.56) | 0.060 |

| MRA | 3063 (63.73) | 1679 (62.77) | 1384 (65.95) | 0.118 |

| ARNI | 336 (6.99) | 204 (7.63) | 132 (6.19) | 0.053 |

| SGLT2 | 153 (3.18) | 73 (2.73) | 80 (3.75) | 0.044 |

| Ivabradine | 767 (15.96) | 424 (15.85) | 343 (16.10) | 0.818 |

| Digoxin | 772 (16.06) | 408 (15.25) | 364 (17.08) | 0.086 |

| Inotropes | 1458 (30.34) | 840 (31.40) | 618 (29.00) | 0.072 |

| Referred/Planned for ICD | 130 (2.7) | 73 (2.73) | 57 (2.67) | 0.908 |

| CRT | 124 (2.58) | 70 (2.62) | 54 (2.58) | |

| LVAD | 4 (0.08) | 3 (0.11) | 1 (0.05) | |

| Transplant | 6 (0.12) | 3 (0.11) | 3 (0.14) |

The consideration for ICD and CRT was low at 2.7% and 2.58%, respectively. LVAD and transplant were done in only 4 and 6 patients, respectively. The use of ICD and CRT did not differ significantly over the two years 2.73%–2.67% (p = 0.9) and 2.62%–2.52% respectively.

4. Discussion

In our analysis of 4806 patients admitted with acute heart failure during the COVID pandemic and the corresponding period during the previous year as reference, we observed a 20% decrease in the admission rates. The reduction was more evident during the initial phase. Similar, reductions have been observed for heart failure and other acute cardiac illnesses across the globe.1,2,5, 6, 7, 8 A similar observation was seen from the Indian College of Cardiology data published from South India during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.17 This is most likely due to the collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic leading to a decrease in the number of patients seeking medical care for acute illness because of the fear of infection with COVID-19. It is also plausible that due to lack of public transport, many patients were managed at local hospitals. The decrease in hospital admissions during COVID times was possibly related to the reluctance of the patients to come to the hospital because of the fear of contracting COVID, as many cardiac centres were converted to dedicated COVID units. The availability of telemedicine may have averted some of the admissions for less severe forms of heart failure. Also, a decrease in the air pollution level may have led to a lesser number of patients decompensating into acute heart failure.12

There were some differences in the resource utilization for HF. However, the mortality rates did not differ between the two cohorts. This was also observed in an earlier study from South India and another study from a single centre in Rajasthan17,18 In-hospital mortality of acute heart failure in our study population was 4.54%, which was higher as compared to Western studies8,13 likely due to limited availability of health services in a developing country. However, in-hospital mortality has improved in the past decade in our country, possibly highlighting improved healthcare services.9,10

The predominant form of heart failure was HFrEF in three-quarters of the patients which remained similar over the two years. The proportion of patients with HFpEF was comparable to earlier studies in the Indian population9, 10, 11 and lesser than in the Western population. This may be due to missing a proportion of patients with HFpEF due to the lack of widespread biomarker testing in India. Ischaemic heart disease was the predominant aetiological factor for acute heart failure presentation followed by dilated cardiomyopathy and valvular heart disease. Valvular heart disease continued to be a major cause of acute heart failure in previous studies.9,10 Comparison over the two years did not show any significant difference in the proportion of any aetiological factor.

In-hospital management was similar in the study population with respect to the use of medical therapy including beta blockers, MRAs, Ivabradine, Digoxin and Inotrope use. However, there was a significant decrease in the use of loop diuretics during the COVID period along with a significant decrease in the use of ACEI. The decrease in the use of ACEI is likely due to the initial concerns about the usage of ACEI in COVID patients.14 There was a significant increase in the use of SGLT2 Inhibitors consistent with the newer studies for heart failure treatment. The overall use of ARNI and SGLT 2 inhibitors continued to be low with cost likely being a major limiting factor. As seen in the previous studies there was overall sub-optimal use of GDMT with lesser use of beta blockers, (ACI/ARB/ARNI) and SGLT2 Inhibitors.10 The use of appropriate medical therapy has increased over the past years with beta-blockers being prescribed in 64.69% of patients which is comparable to the recent data published in the country10,12 This has improved from the earlier 58% in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry. Encouragingly, the use of ACI/ARB/ARNI has increased from 46% to 59.55% and the use of the MRA increased from 45.89% to 63.73% of patients as in the other large data from the country.9,11 Compared with the Western registries the rate of GDMT at discharge is still sub-optimal in our study with AECI/ARB (77%), beta-blockers (77%), MRAs (53.9) and diuretics (83.9%) being prescribed at discharge in the ESC-HF Registry.15

Although the number of intervention procedures decreased during the COVID period, 40% of the patients underwent coronary angiogram in the study population with no significant difference between the study cohorts. However, there were statistically significant increased rates of percutaneous revascularization. This contrasts with another study during the pandemic period in ACS patients where there was a significant decrease in the utilization of interventional procedures.2 It may be due to a rebound increase in the rate of revascularization for ischaemic heart disease patients who could not be revascularized timely. CRT and ICD were offered in about 2–3% of patients.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This is one of the largest data for acute heart failure in India and enrolled patients from multiple centres from different regions of the country. However, the study had the inherent limitations of a retrospective study with an underrepresentation of mortality and other clinical outcomes. Also, the study enrolled patients mostly from tertiary health care centres this might not be a true representation of the actual Indian population. Some relevant data including NYHA class at presentation, readmission rates and 30-day outcome were lacking. Another limitation is that the study was conducted during July to December 2020 period when the COVID lockdown was less intense, and it is possible that if this study was conducted in the earlier period (March 2020 onwards) or during the later period (second wave of COVID) results might have been different.

5. Conclusions

We observed a significant decrease in acute heart failure hospitalisation during the COVID pandemic. However, the outcomes of the admitted patients did not differ significantly with respect to mortality, length of hospital stay, and resource utilisation, barring a few parameters. The study highlighted the sub-optimal use of GDMT, though slightly improving over the last few years. In future pandemics, access to health care and management of acute illnesses should be maintained so that these deserving patients do not suffer preventable complications.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: ALL PARTICIPATING CENTRE CO INVESTIGATORS reports financial support was provided by Cardiological Society of India.

References

- 1.Bhatt A.S., Moscone A., McElrath E.E., et al. Fewer hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jul;76(3):280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zachariah G., Ramakrishnan S., Das M.K., et al. Changing pattern of admissions for acute myocardial infarction in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Heart J. 2021 Jul;73(4):413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt A.S., Jering K.S., Vaduganathan M., et al. Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure Hospitalized With COVID-19. JACC: Heart Fail. 2021;9(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal P., Reshetnyak E., Khan S., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of adults with a history of heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19. Circ Heart Fail. 2021 Sep;14(9) doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.121.008354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox Z.L., Lai P., Lindenfeld J. Decreases in acute heart failure hospitalizations during COVID -19. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 Jun;22(6):1045–1046. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babapoor-Farrokhran S., Alzubi J., Port Z., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on heart failure hospitalizations. SN Compr Clin Med. 2021 Oct;3(10):2088–2092. doi: 10.1007/s42399-021-01005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankfurter C., Buchan T.A., Kobulnik J., et al. Reduced rate of hospital presentations for heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic in Toronto, Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Oct;36(10):1680–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannatà A., Bromage D.I., Rind I.A., et al. Temporal trends in decompensated heart failure and outcomes during COVID -19: a multisite report from heart failure referral centres in London. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 Dec;22(12):2219–2224. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayagopal P.B., Sastry S.L., Nanjappa V., et al. Clinical characteristics and 30-day outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure: results from Indian College of Cardiology national heart failure registry (ICCNHFR) Int J Cardiol. 2022 Jun;356:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harikrishnan S., Sanjay G., Anees T., et al. Clinical presentation, management, in-hospital and 90-day outcomes of heart failure patients in Trivandrum, Kerala, India: the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry: Trivandrum heart failure registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015 Aug;17(8):794–800. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph Stigi, Panniyammakal Jeemon, Abdullakutty Jabir, Sujithkumar S., Jayaprakash Vaikathuseril L., Joseph Johny. The Cardiology society of India-Kerala acute heart failure registry: poor adherence to guideline-directed medical therapy. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:908–915. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponikowski P., Voors A.A., Anker S.D., et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. 2016 Jul 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh R.P., Chauhan A. Impact of lockdown on air quality in India during COVID-19 pandemic. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2020 Aug;13(8):921–928. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00863-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bromage D.I., Cannatà A., Rind I.A., et al. The impact of COVID -19 on heart failure hospitalization and management: report from a Heart Failure Unit in London during the peak of the pandemic. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020 Jun;22(6):978–984. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaduganathan M., Vardeny O., Michel T., McMurray J.J.V., Pfeffer M.A., Solomon S.D. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crespo-Leiro M.G., Anker S.D., Maggioni A.P., et al. European society of Cardiology heart failure long-term registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016 Jun;18(6):613–625. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayagopal P.B., Abdullakutty Jabir, Sridhar L., et al. Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) during COVID-19 pandemic-insights from South India. Indian Heart J. 2021;73:464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhary Rahul, Mathur Rohit, Sharma Jai Bharat, Sanghvi Sanjeev, Deora Surender, Kaushik Atul. Impact of Covid-19 outbreak on the clinical presentation of patients admitted for acute heart failure in India. AJEM (Am J Emerg Med) 2021;39:162–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]