Abstract

Introduction

Retained intraocular foreign body (IOFB) remains an important cause of acquired visual impairment. The visual prognosis following treatments for eyes with retained IOFB was observed to be distinct from other mechanisms of open globe injury due to the specific nature and associated circumstances. This study evaluated the risk behaviors, visual results, and predictive values of Ocular Trauma Score (OTS) in determining visual outcomes in patients with IOFB that were not related to terrorism.

Methods

Medical records of patients who underwent surgical interventions between January 2015 and December 2020 were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

A total of one hundred and sixty-one patients (162 eyes) were recruited. The patients had a mean (standard deviation) age of 47.6 (14.0) years with working male predominance (93.2%). The majority of patients were injured by activities related to grass trimming (63.4%) and metallic objects were the main materials causing injuries (75.7%). Following treatments, the proportion of eyes having vision worse than 20/400 decreased from 126 eyes (77.8%) to 55 eyes (33.9%) at final visit. Ocular trauma score (OTS) had a high potential prediction for final vision in eyes in OTS categories 4 and 5. However, the discordance of final visual acuity distribution was observed in some subgroups of eyes in OTS categories 1 to 3.

Conclusion

This study highlights the significance of IOFB related eye injuries in a tertiary care setting. Decision making on treatments should be carefully considered, particularly in eyes in lower OTS categories, in light of a rise in the proportion of patients who experience improved vision after IOFB removal.

Keywords: Intraocular foreign body, Visual outcomes, Characteristics, Ocular trauma score

1. Introduction

Eye injury with retained intraocular foreign body (IOFB) remains one of the important causes of acquired visual impairment across all age ranges. In previous reports, an incidence of IOFB-related injury accounted from 6% up to 42% among open globe injury (OGI) patients [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. Additionally, a recent study that analyzed the incidence of IOFBs in 204 countries from 1990 to 2019 reported a global increase in age standardized incident rate and incident cases of IOFB since 2008, particularly in the elderly subgroup. The authors also noted variations in incidence of IOFB according to socio-demographic index, age, and gender patterns between geographical locations [7].

With the distinct nature of IOFB injury and related circumstances, visual prognosis following treatments for eyes with retained IOFB was reported to be different from other OGI mechanisms, especially globe rupture and perforation [[8], [9], [10]].

This study, then, aims to explore the distribution of final vision as well as the proportions of final vision compared to the Ocular Trauma Score (OTS) study [11]. Additionally, the current characteristics and visual outcomes of eye injuries with retained IOFB were also assessed. The information regarding visual outcomes and prognosis will help the physician in making decisions for surgical interventions, counselling patients and their families, and assessing any essential psychological supports.

2. Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All data was collected in Microsoft Excel Spread Sheets and deidentified to protect patients’ confidentiality.

The operation lists were used to retrieve consecutive OGI patients admitted and treated between January 2015 and December 2020. After categorized by the Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology Classification [12], medical records of patients were included in this study if retained IOFB was confirmed, either by clinical examination or by other investigations including B-scan ultrasonography and computerized tomography, and had at least one follow-up visit after hospital discharge. Patients who had prior surgical interventions for eye injuries were excluded. The collected data were demographics (age, gender), setting of injury, presenting visual acuity (VA) and ocular characteristics, location of IOFB, managements, and outcomes. The entry wound location was defined according to the Ocular Trauma Classification Group into zone I (an open wound limiting within the cornea and limbal area), zone II (a wound involving the anterior 5 mm of the sclera), and zone III (a wound extending more than 5 mm posterior to the corneoscleral area). Endophthalmitis at presentation was diagnosed based on clinical signs and symptoms. The result of intraocular fluid culture was not required. Final vision was determined at the last follow-up visit.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The categorical data was described by percentage whereas the continuous data by mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (range) when appropriate. Snellen VA was converted to a logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution (logMAR) and assigned a value of 2.3 for hand movement, 2.7 for light perception, and 3.0 for no light perception for analysis [13]. Poor final vision was determined as Snellen final VA worse than 20/400. Multivariable logistic regression analysis with robust estimation was performed to explore factors associated with poor final vision. Based on their size, the entry wounds were divided into two groups: less than 3 mm, and 3 mm and larger. Macular injury was defined as the presence of retinal damage within one disc diameter of the foveal center. The locations of Intraocular foreign bodies were classified as retina-embedded or non-retina embedded. Vitreous hemorrhage was assumed if the fundus could be assessed but the characteristics of the small retinal arteries or retinal nerve fiber were obscured. In addition, the distribution of final vision in each OTS category compared to the estimated values from the OTS study was assessed by testing for equality of proportions [11]. Statistical calculation was performed using the STATA® program. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

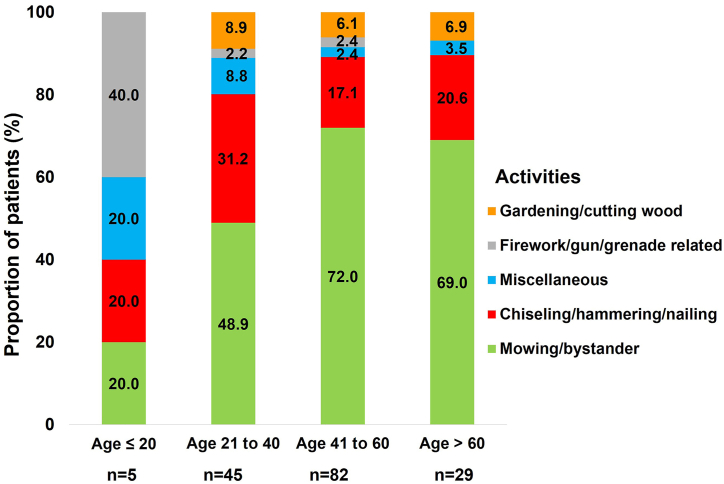

Overall, there were 371 OGI patients during the study period. Among these, there were 161 patients (43.4%) sustaining IOFB and included in this analysis. The mean (SD) age of patients was 47.6 (14.0) years (range; 10–81 years) and the mean (SD) follow-up was 11.5 (13.4) months (range; 1–57 months). Males were predominant (150/161 patients, 93.2%). Of note, a similar distribution of gender between age groups was observed (p = 0.558) (Fig. 1). Most injuries occurred at the workplace (144/161 patients, 89.4%), followed by outdoor and recreational places (12/161 patients, 7.4%), and transportation-related places (2/161 patients, 1.2%). The most common causative activity was using a grass trimmer/mower (102/161 patients, 63.4%) and the metal was the main causative object (122/161 patients, 75.7%) (Table 1). Three patients (3/161, 1.9%) were bystanders. The proportions of activities and objects related to the occurrence of IOFB by age group are illustrated in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, respectively. All patients attained unilateral eye injury (Fig. 4B and C) except one with bilateral eyes injured by a firework explosion. Additionally, all eyes were injured by a single IOFB. Documentation of eye protection use/non-use was recorded in 45/161 patients (28%). Only six patients reported using eye protective devices when injured (four using head nets and two using their corrective eyeglasses). The median (interquartile range, IQR) time interval from injury to the primary hospital was 48 (24–96) hours in patients with active wound leakage. However, patients with self-sealed wounds (78/161, 48.5%) had a median (IQR) time interval from injury to primary hospital of 81 (24–192) hours. A delayed presentation of more than one month was observed in 11/161 (6.8%) patients.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients with intraocular foreign body by age group and gender.

Table 1.

Circumstances associated with occurrences of intraocular foreign body in patients.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Activities | |

| Mowing/bystander | 102 (63.4) |

| Chiseling/hammering/nailing | 35 (21.7) |

| Gardening/cutting wood | 11 (6.8) |

| Firework/gun/grenade-related activities | 5 (3.1) |

| Miscellaneous | 8 (4.9) |

| Objects | |

| Metallic objects | 122 (75.7) |

| Stone | 13 (8.1) |

| Wood branch/wood stick | 5 (3.1) |

| Glass | 3 (1.9) |

| Objects related to explosion | 6 (3.7) |

| Miscellaneous | 12 (7.4) |

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients with intraocular foreign body by age group and related activities.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients with intraocular foreign body by age group and causative object.

Fig. 4.

Images of a 43-year-old man who was struck by a projectile object while cutting grass 10 h prior to the presentation showing penetrating corneal wound with traumatic cataract and hypopyon in the anterior chamber (A), a hyperdense metallic foreign body in the posterior segment on a CT scan (B), and a 2-mm long metallic foreign body following removal (C).

For ocular presentations, the locations of the lacerated entry wound were in the cornea in 119 eyes (73.5%) (Fig. 4, Fig. 5A), the cornea including limbus in 16 eyes (9.9%), the anterior sclera limited within 5 mm from the limbus in 15 eyes (9.3%), the limbus to sclera extending posteriorly beyond 5 mm from limbus in 8 eyes (4.9%), and the cornea to sclera extending posteriorly beyond 5 mm from limbus in 4 eyes (2.5%). A mean (SD) presenting VA was 2.0 (0.8) logMAR and a mean (SD) OTS was 65.3 (19.7) points. Most eyes (126/162, 77.8%) had presenting VA worse than 20/400. Other ocular characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Notably, 3 eyes (3/162, 1.9%) were clinically diagnosed with ocular siderosis based on the appearance of brownish pigment deposits in the corneal stroma and anterior lens capsule, without having undergone electroretinogram testing. Of 162 eyes, the majority of the IOFBs (104 (64.20%) eyes) were embedded in the retina (including 12 (7.4%) eyes were in the central macula, compared to 92 (56.8%) outside the macula (Fig. 5B and C)), followed by 36 (22.2%) eyes in vitreous cavity, 9 (5.6%) eyes in lens, and 13 (8.0%) eyes in other locations.

Fig. 5.

Images of a 65-year-old man who had been hit by a flying object while cutting grass 3 weeks earlier showing a self-sealing corneal laceration with peripheral iris defect (A), a hyperdense metallic foreign body embedded in the retina with surrounded subretinal fluid beneath major vascular arcade on fundus examination (B), chorioretinal scar at the impact site at six months after IOFB removal (C).

Table 2.

Characteristics of eyes with retained intraocular foreign body at presentation by final vision.

| Characteristics | Total, n (%) (n = 162) |

Final Vision, n (%) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worse than 20/400 (n = 55) | 20/400 and better (n = 107) | |||

| Presenting VA (logMAR) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Entry wound location | 0.053 | |||

| Zone I | 135 (83.3) | 42 (76.3) | 93 (86.9) | |

| Zone II | 15 (9.3) | 5 (9.1) | 10 (9.4) | |

| Zone III | 12 (7.4) | 8 (14.6) | 4 (3.7) | |

| Wound size <3 mm | 73 (45.1) | 37 (67.3) | 36 (33.6) | <0.001 |

| RAPD | <0.001 | |||

| Presence | 27 (16.7) | 23 (41.8) | 4 (3.7) | |

| Absence | 133 (82.1) | 30 (54.6) | 103 (96.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.2) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Hyphema | 21 (13.0) | 10 (18.2) | 11 (10.3) | 0.216 |

| Lens injury | 128 (79.0) | 38 (69.1) | 90 (84.1) | 0.040 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 12 (7.4) | 7 (12.7) | 5 (4.6) | 0.109 |

| Retinal detachment | 38 (23.5) | 32 (58.2) | 6 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Endophthalmitis | 51 (31.5) | 32 (58.2) | 19 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Macular injury | 12 (7.6) | 7 (12.7) | 5 (4.8) | 0.111 |

Note: VA = visual acuity, logMAR = logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution, HM = hand movement, RAPD = relative afferent pupillary defect, IOFB = intraocular foreign body.

3.1. Management

Overall, 86/162 (53.1%) eyes had IOFB removed during primary surgical interventions, in which the standard 3-port 23-gauge (G) pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) was performed in 79/162 eyes (in conjunction with phacoemulsification in 38 eyes, pars plana lensectomy (PPL) in 27 eyes, and alone in 14 eyes). The remaining 76/162 (46.9%) eyes had primary globe repair (73 eyes), and combined primary globe repair with phacoemulsification and IOL implantation (3 eyes), with subsequent surgeries to remove IOFB in which 64/162 eyes underwent 23G PPV (in combination with phacoemulsification in 20 eyes, PPL in 38 eyes, and alone in 6 eyes). All IOFBs were removed using intraocular forceps and or in combination with external magnet upon the decision of physicians.

Thirty-eight eyes (38/162, 23.5%) had RD at presentation, and 10 more eyes (10/162, 6.2%) developed RD during treatments (20 eyes of which also had presenting endophthalmitis). Following surgical treatments, the retina was successfully re-attached in 20 eyes (5 eyes with presenting endophthalmitis and 15 eyes without). Additionally, intravitreal injections of ceftazidime 2.25 mg in 0.1 ml and vancomycin 1 mg in 0.1 ml were given upon admission in 36 eyes with presenting endophthalmitis without RD, and during the surgeries in all 51 eyes with presenting endophthalmitis.

During the course of treatment, there were no new infections detected in any eyes. Intraocular tamponade was used in 107/162 (66.0%) eyes (silicone oil in 74 eyes, sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) gas in 19 eyes, and octafluoropropane (C3F8) gas in 14 eyes). Because of severe ocular injuries, 33/162 (20.4%) eyes retained silicone oil at the final visits. No primary globe removal procedure was performed, but secondary globe removal procedures were indicated in 12 eyes (2 eyes for uncontrolled panophthalmitis, 6 eyes for severe endophthalmitis, and 4 eyes for painful blind eyes.

3.2. Visual prognosis

Following treatments, a mean (SD) final VA improved to 1.1 (0.9) logMAR. A proportion of final VA worse than 20/400 significantly decreased to 55 eyes (33.9%), p value < 0.001. An exploratory multivariable analysis reported poor presenting VA (p < 0.001), a larger wound size (p = 0.026), retinal detachment (RD) (p < 0.001), and endophthalmitis (p < 0.001) were associated with poor final VA (Table 3). The distribution of final vision between this study compared to the OTS study is shown in Table 4. Of note, the concordance of final VA distribution to the OTS study was observed for eyes in OTS categories 4 and 5. However, the discordance of final VA distribution was noted in some subgroups of eyes in OTS categories 1 to 3. For other complications, secondary glaucoma developed in 20/162 (12.5%) eyes and none of the patients developed sympathetic ophthalmia.

Table 3.

Exploratory multivariable analysis for factors associated with final vision worse than 20/400 in eyes having retained intraocular foreign body.

| Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95 to 1.02 | 0.487 |

| Male | 0.22 | 0.04 to 1.27 | 0.060 |

| Presenting VA (logMAR) | 6.56 | 2.79 to 15.43 | <0.001 |

| Zone III injury | 1.24 | 0.23 to 6.63 | 0.805 |

| Entrance wound ≥3 mm | 4.44 | 1.19 to 16.56 | 0.026 |

| Lens injury | 0.23 | 0.04 to 1.92 | 0.176 |

| RAPD | 0.80 | 0.10 to 6.42 | 0.836 |

| Retinal detachment | 23.31 | 4.46 to 108.05 | <0.001 |

| Vitreous hemorrhage | 1.54 | 0.43 to 5.58 | 0.508 |

| Endophthalmitis | 19.56 | 4.53 to 84.51 | <0.001 |

| Macular injury | 1.50 | 0.35 to 6.55 | 0.586 |

| Time to primary hospital (hour) | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 0.437 |

| Time to IOFB removal (hour) | 1.01 | 0.98 to 1.02 | 0.683 |

| IOFB embedded in retina | 1.04 | 0.26 to 4.21 | 0.945 |

Note: CI = confidence interval, VA = visual acuity, HM = hand movement, RAPD = relative afferent pupillary defect, IOFB = intraocular foreign body.

Table 4.

Distribution of final vision following treatments in eyes sustaining intraocular foreign body compared to the Ocular Trauma Score study.

| OTS Category |

Data Set (N) |

Final Visual Acuity Group |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPL |

HM/PL |

1/200 to 19/200 |

20/200 to 20/50 |

20/40 and better |

||||||||

|

OTS |

(%) |

P Value |

(%) |

P Value |

(%) |

P Value |

(%) |

P Value |

(%) |

P Value |

Total |

|

| This study | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||||||

| 1 | OTS | (73) | 0.001 | (17) | 0.023 | (7) | 0.051 | (2) | 0.421 | (1) | 0.629 | 0.001 |

| This Study (23) | 10 (43.5) | 8 (34.8) | 4 (17.4) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | |||||||

| 2 | OTS | (28) | 0.001 | (26) | 0.493 | (18) | 0.003 | (13) | 0.185 | (15) | 0.231 | <0.001 |

| This Study (46) | 3 (6.5) | 14 (30.4) | 16 (34.8) | 9 (19.6) | 4 (8.7) | |||||||

| 3 | OTS | (2) | 0.257 | (11) | 0.113 | (15) | 0.055 | (28) | 0.039 | (44) | 0.405 | 0.033 |

| This Study (63) | 0 (0) | 3 (4.8) | 4 (6.3) | 25 (39.7) | 31 (49.2) | |||||||

| 4 | OTS | (1) | 0.645 | (2) | 0.513 | (2) | 0.513 | (21) | 0.394 | (74) | 0.788 | 0.175 |

| This Study (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (28.6) | 15 (71.4) | |||||||

| 5 | OTS | (0) | NA | (1) | 0.763 | (2) | 0.668 | (5) | 0.400 | (92) | 0.731 | 0.151 |

| This Study (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) | |||||||

Abbreviations: OTS, ocular trauma score; NPL, no perception of light; HM, hand movement; PL, perception of light.

4. Discussion

Retained IOFB remained a significant subtype of OGI causing visual impairment. In this non-industrial area, most injuries occurred in males performing personal or self-employed tasks. The risk activities mostly were related to grass trimming/cutting followed by work related to metal-on-metal activities including nailing/hammering. OTS had a high accuracy for predicting final vision in IOFB-related eye injuries with better prognoses (eyes in OTS categories 4 and 5).

Consistent with previous studies, most of the patients with retained IOFB were males [[14], [15], [16], [17]]. However, variation in the incidence of eye injuries by gender, age, and mechanisms has been previously described. In a study of eye injuries requiring hospitalization, females in elderly age and males in middle-age were at risk [18]. In addition, patients injured by globe rupture tended to be older and more likely to be female compared to other mechanisms. The difference in gender distribution was related to a higher chance of falling in elderly females [5,19].

For IOFB, a study that collected data in children aged <18 years found a nearly similar proportion of females to males in young children; however, a decrease in proportion of females in older children was noted. More active lifestyles of growing males potentially contributed to this difference [20].

Another study that analyzed data of IOFB-related eye injuries of all age ranges from Southern China revealed a higher proportion of males than females for patients in primary school age range, adolescence, and older adult [21]. In this study, even though the working age groups were the high-risk populations for having IOFB similar to other studies, a difference in distribution of males and females across age group was not observed. Nevertheless, there were a relatively small number of females in this study, so the relationship between age and gender in IOFB may require further studies.

Regarding activities causing IOFB, inconsistent results between regions were reported [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]]. In Hong Kong, China, and Chile, hammering was the leading cause of IOFB. However, in this study lawnmower/trimmer-related and construction-related activities were found to be major at-risk activities. The differences may be partly attributed to differences in native culture, socioeconomic status, and lifestyles of populations in each region. Grass-trimmer-related injuries and projectile impacts have also been described in previous reports [[27], [28], [29]]. Eye injuries were frequently documented in the incidences related to these devices [28]. Therefore, further education on the potential risk of IOFB while engaging in activities such as using metal-on-metal equipment or others that could generate high velocity projectile objects should be emphasized.

The incidence of eye injuries, especially those associated with retained IOFB can be reduced by following the safety recommendations. In this study, the use of eye protection was documented in only one-fourth of cases and most of those reported not wearing the devices or using inappropriate devices. Therefore, while performing any high-risk activity, people should be encouraged to regularly wear wrap-around or side-shield safety eye protective devices at all times and places, both at home and at work. The use of safety glasses, either alone or in combination with a face shield, should be properly fitted to the face. Also, it is important to emphasize the use of appropriate safety eyewear devices which have a high impact-resistant property rather than their personal corrective eyeglasses [30,31]. As barriers for not using eye protections may differ across activities, knowing the main barriers in each setting is essential for establishing prevention measures. In this retrospective study, the major reason for not using eye protection could not be traced. Therefore, it should be explored in future prospective studies. Additionally, the safety of the surrounding bystanders or coworkers should be considered. Education regarding a safe distance from areas with potentially hazardous activities should also be emphasized. The safety pitfalls should be reviewed to enhance the effectiveness of eye injury-related prevention.

Following treatments, several studies reported that eyes with retained IOFB achieved more favorable visual outcomes than eyes with rupture and perforation [5,6]. Besides, the determination of predictive factors for different visual end points, such as globe survival, in eyes having IOFB were inconsistent [15,23,26,32]. In previous studies, the significant predictors implicated for final vision included age, initial VA, wound size, lens injury, presence of RAPD, vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, macular injury, time to primary repair, and time to IOFB removal. Additionally, various foreign body-related characteristics including location, size, and mass were variously defined as factors related to final vision in IOFB [2,[33], [34], [35]]. In this study, after adjusting the effect of each parameter, the associated factors with a poor final vision (including poor presenting vision, a larger wound size, RD, and endophthalmitis) were consistent with several previous studies. Of note, the correlation between final vision and size of IOFB was not analyzed in a statistical model due to limited information.

In literature, controversial associations between final vision and time to primary repair or time to removal of IOFB were not elucidated [6,17,36,37]. In a large study from China, even though a negative impact of delayed primary repair to the development of infection was observed; time interval from injury to IOFB removal showed no impact on visual outcomes [17]. Similarly, final vision in this study was not affected by either time interval to primary hospital or time interval before IOFB removal. Due to a number of patients in this study sustained injuries by small high-velocity objects, it was hypothesized that the injuries likely resulted in small self-sealed wounds. Therefore, many of them were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms in the acute stage and delayed the initial presentation. Consequently, a larger wound size, due to larger high-velocity objects, were associated with poor vision, even though patients with severely injured eyes tended to seek earlier treatments. Additionally, in a tertiary eye care center, time interval of IOFB removal interventions may be confounded by referral systems. Therefore, these associations should be interpreted with caution.

Location of opened wound was another prognostic indicator for vision in other OGI mechanisms. Nevertheless, this association was not observed in this study. Even though IOFB with entry wound located in posterior sclera could lead to severe posterior segment damage, a significant central corneal scar and severe astigmatism caused by the entry wound could also greatly affect the vision and may partly interfere with the analysis of final vision. During the study period, none of the patients underwent penetrating keratoplasty (PKP), so the impact of wound location on final vision may be confounded.

In daily practice, eye injuries are usually complicated by extensive ocular tissue damage. Final visual estimation by predictive models would provide more useful insight for patients and physicians rather than considering each individual factor. Currently, OTS is the most commonly used predictive model to estimate probability of vision following eye injury. Independent baseline risk characteristics incorporated into OTS calculation are presenting vision, mechanism of injury (rupture or perforation), presence of endophthalmitis, RD, and RAPD. The predictive value of OTS for IOFB-related injuries has only been validated in some nature of injuries. In a study that analyzed IOFB-related to deadly weapons and IOFB-related to metallic objects, the likelihood of their final visions was similar to the OTS study. However, these two studies contained small study populations of 20 and 25 patients, respectively and no patients were in OTS category 5 [38,39]. In another study of IOFB-related injuries presenting with siderosis bulbi, the distribution of final visions of 24 patients were comparable to the OTS study. Also, it was noted that there were no patients in OTS categories 4 and 5 [40]. On the contrary, results from a large study population that analyzed IOFB injuries related to lethal weapons showed that OTS had a high accuracy to predict final VA for eyes in OTS categories 4 and 5; while weaker correlations were shown for eyes in OTS categories 1 to 3 [41]. Consistent with the aforementioned study, the final visions for eyes having IOFB in OTS categories 4 and 5 were highly correlated to the OTS study, whereas some disparities of final visions were observed for eyes in OTS categories 1 to 3. The reason may be possibly attributed to the advancement of current microsurgical instruments that could better alleviate severe ocular complications. However, an analysis in a larger sample size with prospective data collection may provide more robust evidence.

This study assessed patients having eye injuries with retained IOFB who had been treated over a limited recruiting period. Therefore, an impact of time, in terms of shifting lifestyle and/or medical management trends, on visual outcomes would be minimized. However, limited data regarding IOFB characteristics due to a retrospective review and a small sample size in some presenting vision subgroups, might constraint final visual prediction. In addition, in a tertiary center setting, a number of patients were referred back to their primary care hospitals; therefore, long-term ocular complications could not be estimated. Nevertheless, the results signify important characteristics and trends of visual prognoses in patients having retained IOFB in non-industrial and non-terror related settings.

In conclusion, this study reported a predominance of working males and grass trimming/mowing activities as a major relevance of IOFB injury. Following treatments, the majority of patients achieved visual improvement, with approximately sixty percent of patients attaining vision of 20/200 and better. Overall, for visual estimation, the highly predictive values of OTS were indicated in IOFB-related OGI in the higher OTS categories.

Ethical and waiver of informed consent approval

The study and the request for waiver of informed consent were approved by the Research and Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand (Approval number: OPT 2564–07933). This retrospective study was conducted using anonymous data collection and analysis and didn't involve personal privacy and commercial interests. Waiver of informed consent will not adversely affect the rights and interests of the subjects.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Data availability statement

The datasets used for analysis in this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nawat Watanachai: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Janejit Choovuthayakorn: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Onnisa Nanegrungsunk: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Phichayut Phinyo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Susama Chokesuwattanaskul: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Krittai Tanasombatkul: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Linda Hansapinyo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Phit Upaphong: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Tuangprot Porapaktham: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Apisara Sangkaew: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Atitaya Apivatthakakul: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Paradee Kunavisarut: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Voraporn Chaikitmongkol: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Direk Patikulsila: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Barbara Metzler, a director of the Chiang Mai University English Language Team, for help editing this manuscript.

References

- 1.Li E.Y., Chan T.C., Liu A.T., Yuen H.K. Epidemiology of open-globe injuries in Hong Kong. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2017;6:54–58. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicoară S.D., Irimescu I., Călinici T., Cristian C. Intraocular foreign bodies extracted by pars plana vitrectomy: clinical characteristics, management, outcomes and prognostic factors. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15:151. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0128-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujikawa A., Mohamed Y.H., Kinoshita H., Matsumoto M., Uematsu M., Tsuiki E., Suzuma K., Kitaoka T. Visual outcomes and prognostic factors in open-globe injuries. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:138. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0804-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kıvanç S.A., Akova Budak B., Skrijelj E., Tok Çevik M. Demographic characteristics and clinical outcome of work-related open globe injuries in the most industrialised region of Turkey. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2017;47:18–23. doi: 10.4274/tjo.81598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beshay N., Keay L., Dunn H., Kamalden T.A., Hoskin A.K., Watson S.L. The epidemiology of open globe injuries presenting to a tertiary referral eye hospital in Australia. Injury. 2017;48:1348–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guven S., Durukan A.H., Erdurman C., Kucukevcilioglu M. Prognostic factors for open-globe injuries: variables for poor visual outcome. Eye (Lond) 2019;33:392–397. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0218-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan M., Lu Q. Trends and disparities in the incidence of intraocular foreign bodies 1990-2019: a global analysis. Front. Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.858455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung H.C., Lee S.Y., Yoon C.K., Park U.C., Heo J.W., Lee E.K. Intraocular foreign body: diagnostic protocols and treatment strategies in ocular trauma patients. J. Clin. Med. 2021;10:1861. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman I., Maino A., Devadason D., Leatherbarrow B. Open globe injuries: factors predictive of poor outcome. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:1336–1341. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabian I.D., Eliashiv S., Moisseiev J., Tryfonides C., Alhalel A. Prognostic factors and visual outcomes of ruptured and lacerated globe injuries. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2014;24:273–278. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn F., Maisiak R., Mann L., Mester V., Morris R., Witherspoon C.D. The ocular trauma score (OTS) Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15(2):163–165. doi: 10.1016/s0896-1549(02)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn F., Morris R., Witherspoon C.D., Mester V. The Birmingham eye trauma Terminology system (BETT) J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2004;27:206–210. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(04)96122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulze-Bonsel K., Feltgen N., Burau H., Hansen L., Bach M. Visual acuities "hand motion" and "counting fingers" can be quantified with the freiburg visual acuity test. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:1236–1240. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C.C., Tong J.M., Li P.S., Li K.K. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of intraocular foreign bodies in Hong Kong: a 13-year review. Int. Ophthalmol. 2017;37:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ehlers J.P., Kunimoto D.Y., Ittoop S., Maguire J.I., Ho A.C., Regillo C.D. Metallic intraocular foreign bodies: characteristics, interventions, and prognostic factors for visual outcome and globe survival. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008;146:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai H.Q., Yao L., Meng X.X., Wang Y.X., Wang D.B. Visual outcome following intraocular foreign bodies: a retrospective review of 5-year clinical experience. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2011;21:98–103. doi: 10.5301/ejo.2010.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y., Zhang M., Jiang C., Qiu H.Y. Intraocular foreign bodies in China: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and visual outcomes in 1,421 eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2011;152(1):66–73.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raymond S., Jenkins M., Favilla I., Rajeswaran D. Hospital-admitted eye injury in Victoria, Australia. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010;38:566–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto Y., Morikawa S., Okamoto F., Inomoto N., Ishikawa H., Ueda T., Sakamoto T., Sugitani K., Oshika T. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of open globe injuries in Japan. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2019;63:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s10384-018-0638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y., Yang C., Zhao R., Lin L., Duan F., Lou B., Yuan Z., Lin X. Intraocular foreign body injury in children: clinical characteristics and factors associated with endophthalmitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020;104:780–784. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-314913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang T., Zhang Y., Liu L., Zhang K., Zhang X., Wang M., Zeng Y., Zhang M. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and visual outcomes of patients with intraocular foreign bodies in southwest China: a 10-year review. Ophthalmic Res. 2021;64:494–502. doi: 10.1159/000513043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anguita R., Moya R., Saez V., Bhardwaj G., Salinas A., Kobus R., Nazar C., Manriquez R., Charteris D.G. Clinical presentations and surgical outcomes of intraocular foreign body presenting to an ocular trauma unit. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021;259:263–268. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04859-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma J., Wang Y., Zhang L., Chen M., Ai J., Fang X. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of posterior segment intraocular foreign body in a tertiary hospital. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19:17. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-1026-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greven C.M., Engelbrecht N.E., Slusher M.M., Nagy S.S. Intraocular foreign bodies: management, prognostic factors, and visual outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:608–612. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valmaggia C., Baty F., Lang C., Helbig H. Ocular injuries with a metallic foreign body in the posterior segment as a result of hammering: the visual outcome and prognostic factors. Retina. 2014;34:1116–1122. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratanapakorn T., Kongmalai P., Sinawat S., Sanguansak T., Bhoomibunchoo C., Laovirojjanakul W., Yospaiboon Y. Predictors for visual outcomes in eye injuries with intraocular foreign body. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021;14:4587–4593. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S290619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J.R., Hsieh T.C., Chang F.L., He M.S. Lawn trimmer-related open-globe injuries in Taiwan. Retina. 2022;42:973–980. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leinert J., Griffin R., Blackburn J., McGwin G., Jr. The epidemiology of lawn trimmer injuries in the United States: 2000-2009. J. Saf. Res. 2012;43:137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scanzera A.C., Leiderman Y.I., Cortina M.S., Shorter E.S. Open globe injuries from projectile impact: initial presentation and outcomes. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022;70:860–864. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_797_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee S., Agrawal D. Primary prevention of ocular injury in agricultural workers with safety eyewear. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017;65:859–864. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_334_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monaghan P.F., Bryant C.A., McDermott R.J., Forst L.S., Luque J.S., Contreras R.B. Adoption of safety eyewear among citrus harvesters in rural Florida. J. Immigr. Minority Health. 2012;14:460–466. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9484-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hapca M.C., Muntean G.A., Drăgan I.A.N., Vesa Ș.C., Nicoară S.D. Outcomes and prognostic factors following pars plana vitrectomy for intraocular foreign bodies-11-Year retrospective analysis in a tertiary care center. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:4482. doi: 10.3390/jcm11154482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodcock M.G., Scott R.A., Huntbach J., Kirkby G.R. Mass and shape as factors in intraocular foreign body injuries. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2262–2269. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonas J.B., Knorr H.L., Budde W.M. Prognostic factors in ocular injuries caused by intraocular or retrobulbar foreign bodies. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:823–828. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiquet C., Zech J.C., Denis P., Adeleine P., Trepsat C. Intraocular foreign bodies. Factors influencing final visual outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 1999;77:321–325. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhry I.A., Shamsi F.A., Al-Harthi E., Al-Theeb A., Elzaridi E., Riley F.C. Incidence and visual outcome of endophthalmitis associated with intraocular foreign bodies. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008;246:181–186. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colyer M.H., Weber E.D., Weichel E.D., Dick J.S.B., Bower K.S., Ward T.P., Haller J.A. Delayed intraocular foreign body removal without endophthalmitis during operations Iraqi freedom and enduring freedom. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1439–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unal M.H., Aydin A., Sonmez M., Ayata A., Ersanli D. Validation of the ocular trauma score for intraocular foreign bodies in deadly weapon-related open-globe injuries. Ophthalmic Surg. Laser. Imag. 2008;39:121–124. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20080301-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yaşa D., Erdem Z.G., Demircan A., Demir G., Alkın Z. Prognostic value of ocular trauma score for open globe injuries associated with metallic intraocular foreign bodies. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:194. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0874-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu L., Shen P., Lu H., Du C., Shen J., Gu Y. Ocular Trauma Score in siderosis bulbi with retained intraocular foreign body. Medicine (Baltim.) 2015;94:e1533. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guven S. Verification of Ocular Trauma Score for intraocular foreign bodies in lethal-weapon-related ocular injuries. Mil. Med. 2020;185:e1101–e1105. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usaa042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for analysis in this work are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.