Key Points

Question

What factors are associated with postoperative delirium (POD) after noncardiac surgery?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 21 studies that enrolled 8382 patients, male sex, older age, being underweight, lower educational level, smoking, history of delirium, living under care or being institutionalized, greater number of comorbidities, polypharmacy, higher preoperative C-reactive protein serum level, American Society of Anesthesiologists status III or IV, and longer duration of surgery/anesthesia were independently associated with delirium.

Meaning

Results of this study suggest that the factors discussed may be used to explain the expected risk of developing POD and help clinicians to consider perioperative preventive strategies to optimize patient outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Postoperative delirium (POD) is a common and serious complication after surgery. Various predisposing factors are associated with POD, but their magnitude and importance using an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis have not been assessed.

Objective

To identify perioperative factors associated with POD and assess their relative prognostic value among adults undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL from inception to May 2020.

Study Selection

Studies were included that (1) enrolled adult patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, (2) assessed perioperative risk factors for POD, and (3) measured the incidence of delirium (measured using a validated approach). Data were analyzed in 2020.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Individual patient data were pooled from 21 studies and 1-stage meta-analysis was performed using multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression after a multivariable imputation via chained equations model to impute missing data.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The end point of interest was POD diagnosed up to 10 days after a procedure. A wide range of perioperative risk factors was considered as potentially associated with POD.

Results

A total of 192 studies met the eligibility criteria, and IPD were acquired from 21 studies that enrolled 8382 patients. Almost 1 in 5 patients developed POD (18%), and an increased risk of POD was associated with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status 4 (odds ratio [OR], 2.43; 95% CI, 1.42-4.14), older age (OR for 65-85 years, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.16-3.29; OR for >85 years, 6.24; 95% CI, 4.65-8.37), low body mass index (OR for body mass index <18.5, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.64-3.09), history of delirium (OR, 3.9; 95% CI, 2.69-5.66), preoperative cognitive impairment (OR, 3.99; 95% CI, 2.94-5.43), and preoperative C-reactive protein levels (OR for 5-10 mg/dL, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.59-3.50; OR for >10 mg/dL, 3.56; 95% CI, 2.46-5.17). Completing a college degree or higher was associated with a decreased likelihood of developing POD (OR 0.45; 95% CI, 0.28-0.72).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data, several important factors associated with POD were found that may help identify patients at high risk and may have utility in clinical practice to inform patients and caregivers about the expected risk of developing delirium after surgery. Future studies should explore strategies to reduce delirium after surgery.

This individual patient data meta-analysis assesses perioperative factors associated with postoperative delirium after noncardiac surgery.

Introduction

Delirium is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by acute and fluctuating impairment in attention, memory, perception, and consciousness. Postoperative delirium (POD) affects up to 50% of hospitalized surgical patients and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality,1,2 postoperative cognitive decline, poor functional recovery, prolonged hospitalization, higher rates of hospital readmission, and increased health care resource expenditures.3,4,5 Prevention and treatment of POD may be achievable through pharmacological, psychological, and nonpharmacological interventions.6

It is essential to identify patients at risk for POD because adequate and well-timed interventions may reduce POD and its associated complications.6,7 Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have explored factors associated with POD, often with conflicting results.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Furthermore, meta-analysis of aggregate data to identify factors have important limitations, some of which can be addressed by individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis.18,19 The advantages of using IPD for meta-analyses of factors include standardizing statistical analyses across included studies, improved statistical modeling, reduced risk of overfitting, and the ability to investigate more complex associations and interactions.20,21 We performed a systematic review of clinical studies and conducted an IPD meta-analysis to identify factors associated with POD after noncardiac surgery, that addresses limitations of prior reviews.

Methods

We registered our protocol in PROSPERO, published a detailed protocol,22 and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Individual Participant Data (PRISMA-IPD) guidance for reporting the results of this review.23 The original protocol considered both cardiac and noncardiac surgical procedures. We made the post hoc decision to separate these procedures because of major differences in factors and the risk of delirium after surgery.24

Information Sources

We performed systematic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL from inception to May 2020, and reviewed the gray literature using Google Scholar. We screened reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews to find additional studies that met our inclusion criteria. An experienced librarian refined the searches for individual databases. Our search strategy is available in our published protocol.22

Study Selection

Details of our eligibility criteria and study selection process are provided in our published protocol.22 In brief, we included studies that (1) enrolled adults (>16 years) undergoing noncardiac surgery, (2) assessed perioperative factors associated with delirium, and (3) assessed delirium (up to 10 days after surgery) using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition), or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) (collectively, DSM) criteria by a trained individual or a validated delirium assessment tool. We excluded studies conducted in the intensive care unit setting, and studies that addressed delirium tremens, emergence delirium, delirium that occurred outside of the context of surgery, and studies where delirium was not systematically assessed for at least 2 days post surgery. We also excluded studies of patients who had intracranial surgery, since these types of surgery can affect the pathophysiology of POD.24,25

Pairs of reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full-text articles of records retrieved through the searches using standardized, pilot-tested forms in Covidence, an online systematic review software,26 and a crowdsourcing platform.27 Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, involvement of a third reviewer.

Collection of Individual Patient Data

We emailed the corresponding author of each study eligible for our review to gauge interest in sharing IPD. We provided the study protocol and discussed the requirements for data sharing with those interested in collaboration. The data custodian/representative of each respective institution was invited to sign a data sharing agreement, which specified the data (variables) requested, obligations, and ownership of data. The ethics of obtaining data collected from multiple sources across international boundaries and different legal systems were considered as part of the data sharing agreement.

Encrypted data received from study authors was stored in password-protected files on a secure McMaster University computer and only accessed by 2 of us (B.S. and L.M.). Data files were inspected for missing data and unusual outliers via range check for all included variables, and all identified issues were discussed and resolved (if possible) with the original study investigators. We excluded data from patients with preoperative delirium, and patients for which their POD status was not available.

Outcome Definition and Factors

Our primary outcome was POD diagnosed up to 10 days after a procedure or until discharge, whichever was earlier. Included studies used different validated tools to diagnose POD (Table 1).28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 We included the diagnostic tool as an independent factor in our final analysis model, to account for the variability in sensitivity and specificity of different tools.

Table 1. Description of Included Studies.

| Source | Country | Study design | POD diagnostic tool | Type of surgery | POD, % | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasilian et al,28 2018 | Romania | Prospective cohort | CAM | Femoral fracture caused by unintentional fall | 66.3 | 98 |

| Andreozzi et al,29 2020 | Italy | Case-control | CAM | TKA patients | 8.3 | 206 |

| McAlpine et al,30 2008 | Canada | Prospective cohort | CAM & MMSE | Gynecologic malignant tumor | 17.5 | 103 |

| Honda et al,31 2018 | Japan | Case-control | DSM criteria, or diagnosis by attending physician or nurse | Patients with gastric cancer | 4.8 | 1057 |

| Dworkin et al,32 2016 | USA | Prospective cohort | CAM | Any elective surgery | 13.2 | 115 |

| Sato et al,33 2016 | Japan | Prospective cohort | DSM-V | Urologic surgery | 4.7 | 215 |

| Martinez et al,34 2012 | Chile | Randomized trial | CAM | Any elective surgery | 9.4 | 287 |

| Kim et al,35 2016 | South Korea | Prospective cohort | Nu-DESC & CAM | Major general surgery | 20.0 | 1114 |

| Mosk et al,36 2018 | Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | DOSS & DSM-IV | Elective colorectal surgery | 13.2 | 251 |

| Thomson Mangnall et al,37 2011 | Australia | Prospective cohort | CAM | Major elective colorectal .surgery | 34.8 | 118 |

| Van Grootven et al,38 2016 | Belgium | Prospective cohort | CAM | Hip fracture undergoing surgery | 43.3 | 164 |

| Hight et al,39 2018 | New Zealand | Prospective cohort | CAM-ICU | Any elective surgery | 14.4 | 229 |

| Sampson et al,40 2007 | United Kingdom | Randomized trial | DSI | Elective total hip replacement | 21.2 | 33 |

| Dezube et al,41 2020 | USA | Retrospective cohort | DSM criteria | Elective esophagectomy | 16.9 | 378 |

| Chuan et al,42 2020 | Australia | before-after longitudinal] | 3D-CAM | Isolated primary hip fracture | 27.4 | 300 |

| Watne et al,43 2014 | Norway | Randomized trial | CAM | Hip fracture undergoing surgery | 19.2 | 324 |

| Visser et al,44 2015 | Netherlands | Prospective cohort | DOSS | Vascular surgery | 5.5 | 1294 |

| Denhaerynck et al (unpublished) | Switzerland | Prospective cohort | DOSS | Any elective surgery | 14.2 | 900 |

| Brattinga et al,45 2022 | Netherlands | Prospective cohort | DOSS | Any elective surgery | 9.6 | 1019 |

| Dhakharia et al,46 2017 | India | Retrospective cohort | DSM criteria, or diagnosis by attending physician or nurse | Oncologic abdominal surgery | 40.7 | 81 |

| Zywiel et al,47 2015 | Canada | Retrospective cohort | CAM | Hip fracture undergoing surgery | 47.9 | 242 |

Abbreviations: CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; DOSS, Delirium Observational Screening Scale; DSI, Delirium Symptom Interview; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (eligibility based on DSM versions II, IV, or V); MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; Nu-DESC, Nursing Delirium Screening Scale; POD, postoperative delirium; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

We considered a wide range of perioperative factors such as age, sex, level of education, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, number of preoperative medications and polypharmacy, surgical procedure and its duration, cognitive function, number of comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, being institutionalized, history of delirium, and preoperative serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Pairs of reviewers independently evaluated the reporting quality of included studies using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool.48 We assessed the study risk of bias using 5 domains: (1) study participation, (2) study attrition (≥20% missing data was considered high risk of bias), (3) exposure measurement, (4) outcome measurement, and (5) study confounding. We used a modified QUIPS tool to rate each domain as low or high risk of bias as opposed to the original low, medium, and high risk of bias and used the individual domains, rated as low or high risk of bias, to inform the overall risk of bias in each study. Studies with 4 or 5 low-risk domains were considered at overall low risk of bias, studies with 3 or more high-risk domains were considered at overall high risk of bias, and studies with 3 low risk domains were considered at overall medium risk of bias.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The methods of IPD meta-analysis in prognostic research are relatively new compared with those of randomized clinical trials.20,49 We addressed 2 methodologic issues regarding the analysis for our review: (1) method of meta-analysis (1-stage or 2-stage) and (2) management of missing data, where data were missing for some but not all patients in a single study (within-study missingness) or where data were missing for a factor for all patients in a given study (between-study missingness).

In a 2-stage model, data are pooled from each study separately and then aggregated estimates are combined across studies using conventional meta-analytic models.50,51 Using a 1-stage method, only 1 model is fitted to all studies in a hierarchical approach by adding a term to indicate which patient belongs to which study–to account for clustering of patients within studies. Evidence from simulation and empirical studies has shown both approaches produce similar results.50,51 We therefore followed our a priori plan to run the 1-stage approach as described in our protocol.

The strategy to handle missing data within and between studies was based on the extent and mechanism of missingness. We performed multiple-variable imputation using chained equations (MICE) and assumed data were missing at random–ie, conditional on the observed data, the probability of missingness does not depend on the missing values themselves, but it might depend on the observed variables. MICE is a flexible and practical approach with no distributional assumptions and can accommodate imputation for categorical and binary variables.52,53 We applied multiple imputations to the set of variables selected in our final prognostic model when missingness was less than 40%.54 For each variable with missing data, an indicator variable that takes 0 when data were available and 1 when missing data were created. We explored associations between the indicator variable and the rest of variables, as well as the outcome variable, to inform the mechanism of missingness. Variables associated with missingness and the outcome variable were included in the imputation model. Binary logistic, multinomial logistic, and linear regression models were used to impute missing data for binary, categorical, and continuous variables. Missing data were imputed 10 times resulting in 10 complete data sets. Each data set was analyzed separately, and results were combined using Rubin rules. Imputations were performed in Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp) using the mi impute chained command set.

We included all a priori factors in univariate analysis if (1) they were available in at least 3 studies, and (2) had less than 70% missingness. Both cutoff points were based on consensus among our group and previous IPD meta-analyses of prognostic studies and simulation studies.55,56,57,58 For variables with a missing rate between 40% to 70%, missing category was generated and used for regression modeling. We used a backward stepwise approach for multivariable regression to establish a reduced model that best explained the data. We used a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression to perform 1-stage IPD meta-analysis using melogit in Stata. The mi predict and roctab commands were used to assess model performance using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve value. The probability of experiencing POD across studies was calculated using the constant value from the multilevel model without factors (ie, marginal probability). This estimate then was used as the baseline risk to calculate absolute risk estimates for all factors using the following formula: baseline risk – [(odds ratio × baseline risk)/(1-baseline+(odds ratio × baseline risk))].59 The 95% CI for risk differences were calculated using the same formula and by applying lower and upper bounds of odds ratios (ORs) to the baseline risk. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Description of Included Studies

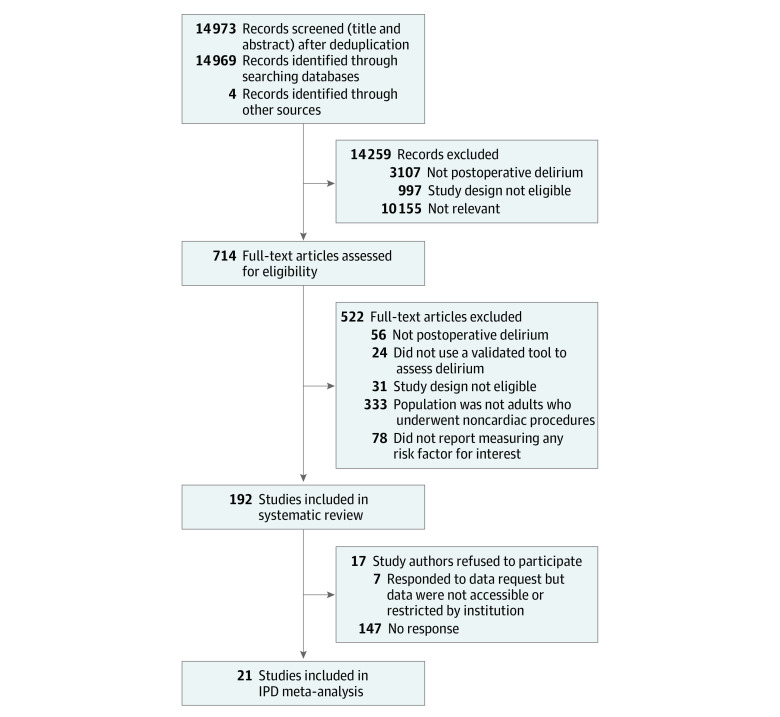

Our searches yielded 14 973 records, of which 192 full-text studies were judged as eligible. We were unable to identify contact information for authors of 17 studies. We contacted study authors of the remaining 175 studies and received IPD data from authors of 21 studies (8528 patients) comprising 20 publications28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 and 1 unpublished study by K.D. et al. We excluded 146 patients for whom their POD status was not available, leaving 8382 patients for analyses (Figure).

Figure. Flow Diagram for Study Selection.

IPD indicates individual patient data.

Most included studies were cohort studies (n = 15). Study populations were acquired from 15 countries, including Europe (9 studies [43%]), Asia (4 studies [19%]), North America (4 studies [19%), Australia and New Zealand (3 studies [14%]), and 1 study (5%) from South America. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and CAM-ICU (intensive care unit) were the most frequently used diagnostic tools for POD assessment (12 studies [57%]), followed by the Delirium Observation Screening Scale (DOSS) (4 studies [19%]), and DSM criteria (4 studies [19%]) (Table 1).

Most patients underwent elective procedures (85%), including abdominal surgery (35%), orthopedic surgery (26%), and vascular surgery (17%). The median duration of surgery across studies was 203 minutes (interquartile range [IQR], 122-292 minutes). Approximately half (58%) of patients were male and the median age was 71 years (IQR, 63-78 years); only 8% of patients were 85 years of age or older. The characteristics of included patients are described in Table 2. eFigure in Supplement 1 provides the risk of bias assessments among the included studies.

Table 2. Characteristics of 8382 Included Patients.

| Preoperative factor | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No delirium | With delirium | Total patients, No. | |

| Postoperative delirium diagnosis method | |||

| DSM & ICD-10 | 48 (59.3) | 33 (40.7) | 81 |

| CAM | 1493 (74.2) | 518 (25.8) | 2011 |

| DSI | 26 (78.8) | 7 (21.2) | 33 |

| CAM & Nu-DESC | 902 (81.0) | 211 (19.0) | 1113 |

| CAM & MMSE | 85 (82.5) | 18 (17.5) | 103 |

| DOSS & DSM-IV | 218 (86.8) | 33 (13.1) | 251 |

| DOSS | 2852 (90.8) | 288 (9.2) | 3140 |

| DSM criteria | 1525 (92.4) | 125 (7.6) | 1650 |

| Surgical procedure type | |||

| Orthopedic | 1672 (75.7) | 536 (24.3) | 2208 |

| Liver | 92 (80.7) | 22 (19.3) | 114 |

| Thoracic | 317 (82.1) | 69 (17.9) | 386 |

| Abdominal | 2573 (87.7) | 362 (12.3) | 2935 |

| Gynecologic | 263 (89.2) | 32 (10.9) | 295 |

| Vascular | 1318 (91.7) | 120 (8.3) | 1438 |

| Laparoscopic | 389 (92.0) | 34 (8.0) | 423 |

| Other | 525 (90.1) | 58 (10.0) | 583 |

| Procedure type | 7791 | ||

| Elective | 5857 (88.7) | 750 (11.4) | 6607 |

| Emergency | 635 (76.7) | 193 (23.3) | 828 |

| Urgent | 206 (57.9) | 150 (42.1) | 356 |

| Sex | 7264 | ||

| Female | 2557 (83.0) | 525 (17.0) | 3082 |

| Male | 3620 (86.6) | 562 (13.4) | 4182 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 70 (62-77) | 78 (71-85) | 8232 |

| ≤65 y | 2481 (94.0) | 158 (6.0) | 2639 |

| 65-85 y | 4137 (84.0) | 787 (16.0) | 4924 |

| >85 y | 407 (60.8) | 262 (39.2) | 669 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 25.0 (22.3-28.0) | 24.4 (21.2-27.8) | 7378 |

| <25 | 3155 (85.3) | 544 (14.7) | 3699 |

| 25-30 | 2173 (87.6) | 307 (12.4) | 2480 |

| >30-35 | 768 (87.8) | 107 (12.2) | 875 |

| >35 | 282 (87.0) | 42 (13.0) | 324 |

| Smoking status | 4064 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 1828 (83.9) | 351 (16.1) | 2179 |

| Ex-smoker | 694 (89.9) | 78 (10.1) | 772 |

| Smoker | 945 (84.9) | 168 (15.1) | 1113 |

| Operation time, median (IQR), minutes | 209 (133-293) | 148 (71-264) | 3578 |

| ASA physical status | 5567 | ||

| 1 | 329 (92.9) | 25 (7.1) | 354 |

| 2 | 2352 (89.9) | 263 (10.1) | 2615 |

| 3 | 1912 (79.8) | 483 (20.2) | 2395 |

| 4 | 124 (61.1) | 79 (38.9) | 203 |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; DOSS, Delirium Observation Screening Scale; DSI, Delirium Symptom Interview; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (eligibility based on DSM versions II, IV, or V); ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; Nu-DESC, Nursing Delirium Screening Scale.

Univariate Multilevel Mixed Model

The probability of experiencing POD across studies was 17.7%, calculated from an intercept-only model with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.21 (95% CI, 0.13-0.34). The results of univariate analyses without imputation (complete case analysis) and after performing MICE imputation were similar to estimates for factors. Older age, being underweight (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared] <18.5), male sex, less educated, being institutionalized, preoperative cognitive impairment, being prescribed 5 or more medications, having a history of delirium, elevated preoperative serum CRP level, type of surgical procedure, higher ASA status, longer duration of surgery/anesthesia, and having more comorbidities as well as a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index were associated with greater risk of developing POD. The results of univariate multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Estimated Associations for Factors of Postoperative Delirium From Univariate and Multivariable Multilevel Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression With and Without MICE Imputation.

| Variablea | Unadjusted without imputation | Unadjusted with MICE | Adjusted with MICE | Risk difference, % (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Procedure or surgery (n = 8382) | |||||||

| Orthopedic | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Abdominal | 0.61 (0.39 to 0.96) | .03 | 0.61 (0.39 to 0.96) | .03 | 1.08 (0.68 to 1.71) | .75 | 1.15 (−4.94 to 9.19) |

| Vascular | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.92) | .02 | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.92) | .02 | 0.71 (0.44 to 1.15) | .16 | −4.45 (−9.06 to 2.13) |

| Laparoscopic | 0.36 (0.19 to 0.68) | .002 | 0.36 (0.19 to 0.68) | .002 | 0.64 (0.33 to 1.26) | .20 | −5.60 (−11.07 to 3.62) |

| Thoracic | 1.50 (0.44 to 5.06) | .51 | 1.50 (0.44 to 5.06) | .51 | 3.21 (0.98 to 10.56) | .06 | 23.14 (−0.29 to 51.73) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 0.34 (0.18 to 0.67) | .002 | 0.34 (0.18 to 0.67) | .002 | 0.66 (0.30 to 1.46) | .31 | −5.27 (−11.64 to 6.2) |

| Liver | 0.72 (0.37 to 1.37) | .31 | 0.72 (0.37 to 1.37) | .31 | 1.37 (0.68 to 2.78) | .38 | 5.06 (−4.94 to 19.72) |

| Other elective | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.77) | .003 | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.77) | .003 | 0.65 (0.39 to 1.08) | <.99 | −5.44 (−9.96 to 1.15) |

| Procedure type (n = 5567) | |||||||

| Elective | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Urgent | 1.61 (0.84 to 3.05) | .15 | 2.13 (1.06 to 4.26) | .04 | NA | NA | NA |

| Emergency | 2.76 (1.83 to 4.15) | <.001 | 1.88 (1.34 to 2.65) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| ASA status (n = 7791) | |||||||

| 1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| 2 | 1.86 (1.20 to 2.88) | .01 | 1.69 (1.04 to 2.73) | .03 | 1.09 (0.66 to 1.81) | .72 | 1.29 (−5.27 to 10.32) |

| 3 | 4.42 (2.84 to 6.86) | <.001 | 3.77 (2.35 to 6.05) | <.001 | 1.76 (1.05 to 2.95) | .03 | 9.76 (0.72 to 21.12) |

| 4 | 7.33 (4.24 to 12.66) | <.001 | 6.61 (3.75 to 11.64) | <.001 | 2.43 (1.42 to 4.14) | .001 | 16.62 (5.69 to 29.4) |

| Operation time, h (n = 3578) | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15) | .004 | 1.08 (1.02 to 1.14) | .01 | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.17) | .001 | 1.57 (0.72 to 2.4) |

| Sex (n = 7264) | |||||||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Male | 1.24 (1.45 to 1.07) | .01 | 1.23 (1.43 to 1.05) | .01 | 1.28 (1.08 to 1.5) | .004 | 3.89 (1.15 to 6.69) |

| Age, y (n = 8232) | |||||||

| ≤65 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| 66-85 y | 3.36 (2.76 to 4.10) | <.001 | 3.31 (2.72 to 4.02) | <.001 | 2.67 (2.16 to 3.29) | <.001 | 18.78 (14.02 to 23.74) |

| >85 y | 8.79 (6.70 to 11.52) | <.001 | 8.61 (6.57 to 11.28) | <.001 | 6.24 (4.65 to 8.37) | <.001 | 39.60 (32.30 to 46.59) |

| BMI (n = 7378) | |||||||

| Normal (18.5-25) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 2.30 (1.73 to 3.06) | <.001 | 2.28 (1.73 to 3.01) | <.001 | 2.25 (1.64 to 3.09) | <.001 | 14.91 (8.37 to 22.22) |

| Preobesity (25-30) | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.09) | .33 | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | .29 | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.09) | .30 | −1.33 (−3.81 to 1.29) |

| Obesity class I (>30-35) | 0.92 (0.72 to 1.17) | .50 | 0.9 (0.71 to 1.14) | .36 | 0.85 (0.65 to 1.11) | .24 | −2.24 (−5.44 to 1.57) |

| Obesity class II (>35) | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.26) | .49 | 0.84 (0.6 to 1.19) | .33 | 0.77 (0.53 to 1.12) | .17 | −3.49 (−7.47 to 1.71) |

| Educational level (n = 1773) | |||||||

| Less than diploma (<12 y) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Diploma (12 y) | 0.62 (0.46 to 0.83) | .001 | 0.62 (0.46 to 0.83) | .002 | 0.71 (0.51 to 0.99) | .04 | −4.45 (−7.82 to −0.15) |

| College degree or more (>12 y) | 0.37 (0.24 to 0.58) | <.001 | 0.39 (0.26 to 0.60) | <.001 | 0.45 (0.28 to 0.72) | .001 | −8.88 (−12.02 to −4.29) |

| Smoking (n = 4064) | |||||||

| Nonsmoker | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Ex-smoker | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.30) | .81 | 1.01 (0.75 to 1.36) | .93 | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.21) | .43 | −1.79 (−5.77 to 2.95) |

| Smoker | 1.20 (0.97 to 1.48) | .09 | 1.21 (0.98 to 1.50) | .07 | 1.37 (1.09 to 1.72) | .01 | 5.06 (1.29 to 9.3) |

| Alcohol consumption (n = 3793) | |||||||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Any use | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.20) | .85 | 0.97 (0.80 to 1.19) | .80 | NA | NA | NA |

| Institutionalized (n = 3359) | |||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Yes | 2.86 (2.03 to 4.02) | <.001 | 2.83 (2.01 to 3.98) | <.001 | 1.54 (1.07 to 2.23) | .02 | 7.18 (1.01 to 14.71) |

| History of delirium (n = 3356) | |||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Yes | 5.95 (4.28 to 8.27) | <.001 | 6.34 (4.56 to 8.82) | <.001 | 3.9 (2.69 to 5.66) | <.001 | 27.92 (18.95 to 37.2) |

| Preoperative cognitive impairment (n = 4312) | |||||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| Yes | 5.55 (4.20 to 7.34) | <.001 | 5.74 (4.34 to 7.60) | <.001 | 3.99 (2.94 to 5.43) | <.001 | 28.48 (21.04 to 36.17) |

| Preoperative CRP serum level (n = 4150) | |||||||

| <1 mg/dL | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| 1-5 mg/dL | 2.09 (1.58 to 2.76) | <.001 | 2.04 (1.54 to 2.69) | <.001 | 1.74 (1.29 to 2.34) | <.001 | 9.53 (4.02 to 15.78) |

| >5-10 mg/dL | 2.77 (1.91 to 4.02) | <.001 | 2.67 (1.85 to 3.85) | <.001 | 2.35 (1.59 to 3.5) | <.001 | 15.87 (7.78 to 25.25) |

| >10 mg/dL | 5.05 (3.58 to 7.12) | <.001 | 4.69 (3.35 to 6.56) | <.001 | 3.56 (2.46 to 5.17) | <.001 | 25.66 (16.9 to 34.95) |

| No. of preoperative comorbidities (n = 8102) | |||||||

| None | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| 1 | 1.89 (1.32 to 2.46) | <.001 | 1.88 (1.46 to 2.42) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.02 to 1.76) | .03 | 4.67 (0.29 to 9.76) |

| 2 | 2.33 (1.57 to 3.09) | <.001 | 2.30 (1.77 to 2.98) | <.001 | 1.37 (1.02 to 1.83) | .04 | 5.06 (0.29 to 10.54) |

| 3 | 3.38 (2.13 to 4.63) | <.001 | 3.35 (2.54 to 4.43) | <.001 | 1.61 (1.16 to 2.23) | .01 | 8.02 (2.27 to 14.71) |

| ≥4 | 4.89 (2.99 to 6.79) | <.001 | 4.81 (3.59 to 6.46) | <.001 | 1.86 (1.28 to 2.71) | .001 | 10.87 (3.89 to 19.12) |

| Polypharmacy (preoperative) (n = 3158) | |||||||

| <5 Medications | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | NA | ||

| ≥5 Medications | 2.69 (2.21 to 3.28) | <.001 | 2.68 (2.20 to 3.26) | <.001 | 1.83 (1.47 to 2.29) | <.001 | 10.54 (6.32 to 15.3) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (not adjusted for age) (n = 8232) | 1.27 (1.20 to 1.34) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.19 to 1.34) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.18) | .03 | 1.29 (0.15 to 2.54) |

Abbreviations: ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CRP, C-reactive protein; MICE, multiple-variable imputation using chained equations; NA, not applicable.

SI conversion factor: To convert CRP to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524.

Sample size for the unadjusted model without imputation. The final model is adjusted for delirium diagnostic tool. We used a backward stepwise approach for multivariable regression to find a reduced model that best explained the data. Model performance: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.81 (95% CI, 0.79-0.82).

Multivariable Multilevel Mixed-Effects Model With MICE

In our final adjusted model, factors that had a statistically significant association with POD were male sex (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.08-1.50), older age (OR for age 65-85 years, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.16-3.29, OR for age older than 85 years: 6.24; 95% CI, 4.65-8.37), being underweight (BMI <18.5) (OR, 2.25; 95% CI, 1.64-3.09), less education (OR for having a diploma [at least 12 years of education], 0.71; 95% CI, 0.51-0.99, OR for having a college degree or more [>12 years of education], 0.45; 95% CI, 0.28-0.72), being a smoker (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.09-1.72), having a history of delirium (OR, 3.90; 95% CI, 2.69-5.66), being institutionalized (OR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.07-2.23), comorbidities (OR for 1 comorbid condition, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76, OR for 2 comorbid conditions, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.02-1.83, OR for 3 comorbid conditions: 1.61; 95% CI, 1.16-2.23, OR for 4 or more comorbid conditions, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.28-2.71), receiving 5 or more medications (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.47-2.29), having a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index (OR for 1-unit increase, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01-1.18), higher preoperative serum CRP level (OR for 1-5 mg/dL, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.29-2.34, OR for 5-10 mg/dL: 2.35; 95% CI, 1.59-3.50, OR for >10 mg/dL, 3.56; 95% CI, 2.46-5.17), ASA status of 3 (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.05-2.95), ASA status of 4 (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.42-4.14), and longer duration of surgery/anesthesia (OR for each 1 hour increase, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.05-1.17).

Table 3 shows the factors independently associated with POD from the multivariable multilevel mixed-effects model. The model performance assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.79-0.82), indicating a good prognostic model; however, we did not perform any statistical validation or evaluated the calibration curve. We did not find any significant interaction between the independent factors. eTable in Supplement 1 provides the results of sensitivity analysis excluding Dhakharia et al,46 (at high risk of bias), which showed no important differences in results.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first IPD meta-analysis of factors associated with POD after noncardiac surgery. In pooled analysis of 8382 patients from 21 studies, we found that patients older than 65 years were at high risk of developing POD with the risk in patients older than 85 years being 6.2 times higher than those younger than 65 years old. Preoperative cognitive impairment and history of delirium were associated with nearly 4 times greater risk of experiencing delirium after surgery. Every hour increase in duration of surgery was associated with up to 11% greater risk of POD. In addition, having a low BMI (<18.5), with more comorbidities, a higher ASA status, and higher CRP serum level considerably increased the associated risk of POD. Other independent risk factors for POD included receiving more medications, smoking, being institutionalized, and being a male, while having higher level of education was associated with up to 55% lower risk of POD.

While there are several reviews on risk factors of POD, almost all focus on specific surgical procedure.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 There are 3 systematic reviews that investigated factors associated with POD after elective surgical procedures.8,17,60 All reviews combined cardiac and noncardiac surgical procedures and reported a nearly similar POD incidence rate to our finding. Watt et al60 reported history of delirium, frailty, cognitive impairment, psychotropic medication use, smoking, older age, and ASA status as important factors. Abate et al17 and Liu et al8 only assessed the association of a limited risk factors with POD and reported type of anesthesia, hypotension, alcohol consumption, CRP, and interleukin 6 as important factors. We did not have enough information to assess the prognostic value of interleukin 6 and our findings showed alcohol consumption was not associated with an increased risk of POD.

We only included studies and data in which POD was assessed systematically using a validated tool. We also adjusted our model for different diagnostic tools used across the included studies. The performance of our final model was high (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve = 0.81), which attests to the robustness of the adjusted model. We did not formally assess the model validity or evaluate the calibration curve in the current report; however, we report details of the prediction model development process and the associated results in a separate publication.61 We used advanced statistical modeling to handle missing participant data when appropriate.

Implication for Practice and Future Research

Given the high rates of POD among different noncardiac surgical procedures, extenuating strategies are required by different stakeholders for effective prevention and management of POD. Adequate preoperative evaluation and preparation of patients, caregivers, and physicians to appropriately manage treatment for patients at high risk, and create awareness toward modifiable risk factors, can be important steps toward mitigating the risk of POD. Developing bedside tools to help identify patients at risk and target modifiable risk factors in patient at higher risk of POD can improve patient care, reduce delirium-associated hospital costs, and help with defining appropriate populations to perform multicenter trials of interventions.

Limitations

The main limitation was low response rate to our requests for sharing IPD, and many investigators declined to participate in our study. The start of the project coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, and requests were sent while many critical care physicians were dealing with the first peak of the pandemic and many nonclinician researchers were in lockdown with no access to their study data. The second limitation is the high rate of between-study missingness and that we were unable to study several important clinical variables (such as opioid use, pain, type of anesthesia and drugs used to induce anesthesia, and use of psychoactive drugs and benzodiazepines) because of inconsistencies or absence among the included studies. We used a flexible and practical approach with no distributional assumption to handle imputations under the missing at random assumption and only applied it to variables with less than 40% missingness.

The third limitation relates to the inherent limitation of multiple logistic regression modeling. We needed to dichotomize or categorize some characteristics because they did not meet the distributional requisites. Despite using postestimations and predictive margins, it is possible that the choice of thresholds may have affected the results in a way that cannot be predicted. Finally, while we managed to include a number of risk factors in our model, because of the nature of observational studies residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Conclusions

We found that sex, age, BMI, education, smoking, history of delirium, being institutionalized, having comorbidities, polypharmacy, serum CRP level, ASA status, and duration of surgery/anesthesia were independently associated with POD. These factors can be used in clinical practice to inform patients and caregivers about the expected risk of developing delirium after surgery and to explain which features should prompt clinicians to consider perioperative preventive strategies to optimize patient care.

eTable. The Estimated Associations for Prognostic Factors of Post-Operative Delirium From Multivariable Multilevel Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression With MICE Imputation From Sensitivity Analysis Excluding High Risk of Bias Study

eFigure. Risk of Bias Assessments Among the Included Studies Using QUIPS Tool

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Witlox J, Eurelings LSM, de Jonghe JFM, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443-451. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raats JW, van Eijsden WA, Crolla RM, Steyerberg EW, van der Laan L. Risk factors and outcomes for postoperative delirium after major surgery in elderly patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickel H, Gradinger R, Kochs E, Förstl H. High risk of cognitive and functional decline after postoperative delirium. A three-year prospective study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26(1):26-31. doi: 10.1159/000140804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):30-39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Z, Hu J, Ma D. Postoperative delirium: perioperative assessment, risk reduction, and management. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(4):492-504. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton JK, Craig LE, Yong SQ, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;7(7):CD013307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Yu Y, Zhu S. Inflammatory markers in postoperative delirium (POD) and cognitive dysfunction (POCD): a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholz AF, Oldroyd C, McCarthy K, Quinn TJ, Hewitt J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postoperative delirium among older patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103(2):e21-e28. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TO, Cooper A, Peryer G, Griffiths R, Fox C, Cross J. Factors predicting incidence of post-operative delirium in older people following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(4):386-396. doi: 10.1002/gps.4655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Y, Wang G, Liu S, et al. Risk factors for postoperative delirium in patients undergoing major head and neck cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47(6):505-511. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanyaolu L, Scholz AFM, Mayo I, et al. Risk factors for incident delirium among urological patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis with GRADE summary of findings. BMC Urol. 2020;20(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12894-020-00743-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z, Wang XF, Yang LF, Fang C, Gu XK, Guo HW. Prevalence and risk factors for postoperative delirium in patients with colorectal carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35(3):547-557. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03505-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Q, Zhou X, Zhang Y, et al. Predictors of postoperative delirium in elderly patients following total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):945. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04825-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noah AM, Almghairbi D, Evley R, Moppett IK. Preoperative inflammatory mediators and postoperative delirium: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127(3):424-434. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aitken SJ, Blyth FM, Naganathan V. Incidence, prognostic factors and impact of postoperative delirium after major vascular surgery: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Vasc Med. 2017;22(5):387-397. doi: 10.1177/1358863X17721639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abate SM, Checkole YA, Mantedafro B, Basu B, Aynalem AE. Global prevalence and predictors of postoperative delirium among non-cardiac surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg Open. 2021;32:100334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijso.2021.100334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trivella M, Pezzella F, Pastorino U, Harris AL, Altman DG; Prognosis In Lung Cancer (PILC) Collaborative Study Group . Microvessel density as a prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung carcinoma: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(6):488-499. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70145-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riley RD, Sauerbrei W, Altman DG. Prognostic markers in cancer: the evolution of evidence from single studies to meta-analysis, and beyond. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(8):1219-1229. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abo-Zaid G, Sauerbrei W, Riley RD. Individual participant data meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies: state of the art? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchan TA, Sadeghirad B, Schmutz N, et al. Preoperative prognostic factors associated with postoperative delirium in older people undergoing surgery: protocol for a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):261. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01518-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, et al. ; PRISMA-IPD Development Group . Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1657-1665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Harten AE, Scheeren TW, Absalom AR. A review of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation associated with cardiac surgery and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):280-293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.07008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Viderman D, Brotfain E, Bilotta F, Zhumadilov A. Risk factors and mechanisms of postoperative delirium after intracranial neurosurgical procedures. Asian J Anesthesiol. 2020;58(1):5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Covidence. Better systematic review management. Accessed September 8, 2023. https://www.covidence.org

- 27.insightScope. The future of systematic reviews. Accessed September 8, 2023. https://insightscope.ca

- 28.Vasilian CC, Tamasan SC, Lungeanu D, Poenaru DV. Clock-drawing test as a bedside assessment of post-operative delirium risk in elderly patients with accidental hip fracture. World J Surg. 2018;42(5):1340-1345. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4294-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andreozzi V, Conteduca F, Iorio R, et al. Comorbidities rather than age affect medium-term outcome in octogenarian patients after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(10):3142-3148. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05788-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAlpine JN, Hodgson EJ, Abramowitz S, et al. The incidence and risk factors associated with postoperative delirium in geriatric patients undergoing surgery for suspected gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(2):296-302. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honda S, Furukawa K, Nishiwaki N, et al. Risk factors for postoperative delirium after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients. World J Surg. 2018;42(11):3669-3675. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4682-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dworkin A, Lee DS, An AR, Goodlin SJ. A simple tool to predict development of delirium after elective surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e149-e153. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato T, Hatakeyama S, Okamoto T, et al. Slow gait speed and rapid renal function decline are risk factors for postoperative delirium after urological surgery. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0153961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez FT, Tobar C, Beddings CI, Vallejo G, Fuentes P. Preventing delirium in an acute hospital using a non-pharmacological intervention. Age Ageing. 2012;41(5):629-634. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim MY, Park UJ, Kim HT, Cho WH. Delirium prediction based on hospital information (Delphi) in general surgery patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(12):e3072. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosk CA, van Vugt JLA, de Jonge H, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass as a risk factor for postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:2097-2106. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S175945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mangnall LT, Gallagher R, Stein-Parbury J. Postoperative delirium after colorectal surgery in older patients. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(1):45-55. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Grootven B, Detroyer E, Devriendt E, et al. Is preoperative state anxiety a risk factor for postoperative delirium among elderly hip fracture patients? Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(8):948-955. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hight DF, Sleigh J, Winders JD, et al. Inattentive delirium vs disorganized thinking: a new axis to subcategorize PACU delirium. Front Syst Neurosci. 2018;12:22. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2018.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sampson EL, Raven PR, Ndhlovu PN, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil hydrochloride (Aricept) for reducing the incidence of postoperative delirium after elective total hip replacement. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):343-349. doi: 10.1002/gps.1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dezube AR, Bravo-Iñiguez CE, Yelamanchili N, et al. Risk factors for delirium after esophagectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2020;121(4):645-653. doi: 10.1002/jso.25835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuan A, Zhao L, Tillekeratne N, et al. The effect of a multidisciplinary care bundle on the incidence of delirium .after hip fracture surgery: a quality improvement study. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(1):63-71. doi: 10.1111/anae.14840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watne LO, Torbergsen AC, Conroy S, et al. The effect of a pre- and postoperative orthogeriatric service on cognitive function in patients with hip fracture: randomized controlled trial (Oslo Orthogeriatric Trial). BMC Med. 2014;12:63. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visser L, Prent A, van der Laan MJ, et al. Predicting postoperative delirium after vascular surgical procedures. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(1):183-189. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brattinga B, Plas M, Spikman JM, et al. The association between the inflammatory response following surgery and post-operative delirium in older oncological patients: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2022;51(2):afab237. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dhakharia V, Sinha S, Bhaumik J. Postoperative delirium in Indian patients following major abdominal surgery for cancer: risk factors and associations. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2017;8(4):567-572. doi: 10.1007/s13193-017-0691-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zywiel MG, Hurley RT, Perruccio AV, Hancock-Howard RL, Coyte PC, Rampersaud YR. Health economic implications of perioperative delirium in older patients after surgery for a fragility hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(10):829-836. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280-286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Debray TPA, de Jong VMT, Moons KGM, Riley RD. Evidence synthesis in prognosis research. Diagn Progn Res. 2019;3:13. doi: 10.1186/s41512-019-0059-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burke DL, Ensor J, Riley RD. Meta-analysis using individual participant data: one-stage and two-stage approaches, and why they may differ. Stat Med. 2017;36(5):855-875. doi: 10.1002/sim.7141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas D, Platt R, Benedetti A. A comparison of analytic approaches for individual patient data meta-analyses with binary outcomes. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0307-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377-399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(1):40-49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clark TG, Altman DG. Developing a prognostic model in the presence of missing data: an ovarian cancer case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(1):28-37. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00539-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burgess S, White IR, Resche-Rigon M, Wood AM. Combining multiple imputation and meta-analysis with individual participant data. Stat Med. 2013;32(26):4499-4514. doi: 10.1002/sim.5844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JH, Huber JC Jr. Evaluation of multiple imputation with large proportions of missing data: how much is too much? Iran J Public Health. 2021;50(7):1372-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5(8):e165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackson D, White I, Kostis JB, et al. ; Fibrinogen Studies Collaboration . Systematically missing confounders in individual participant data meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. Stat Med. 2009;28(8):1218-1237. doi: 10.1002/sim.3540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Santesso N, et al. GRADE guidelines: 12. Preparing summary of findings tables—binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(2):158-172. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watt J, Tricco AC, Talbot-Hamon C, et al. Identifying older adults at risk of delirium following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):500-509. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4204-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dodsworth BT, Reeve K, Falco L, et al. Development and validation of an international preoperative risk assessment model for postoperative delirium. Age Ageing. 2023;52(6):afad086. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afad086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. The Estimated Associations for Prognostic Factors of Post-Operative Delirium From Multivariable Multilevel Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression With MICE Imputation From Sensitivity Analysis Excluding High Risk of Bias Study

eFigure. Risk of Bias Assessments Among the Included Studies Using QUIPS Tool

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement