Key Points

Question

Is equal access to health care associated with reduced racial and ethnic disparities in the clinical outcomes of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer?

Findings

A cohort study of 12 992 veterans with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated in an equal-access health care setting found improved survival outcomes in self-identified Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that the availability of equal-access care may reduce and even reverse racial and ethnic disparities in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer are poorly understood. A given disparity-related factor may affect outcomes differently at each point along the highly variable trajectory of the disease.

Objective

To examine clinical outcomes by race and ethnicity in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) within the US Veterans Health Administration.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective, observational cohort study using electronic health care records (January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2021) in a nationwide equal-access health care system was conducted. Mean (SD) follow-up time was 4.3 (3.3) years. Patients included in the analysis were diagnosed with prostate cancer from January 1, 2006, to December 30, 2020, that progressed to nmCRPC defined by (1) increasing prostate-specific antigen levels, (2) ongoing androgen deprivation, and (3) no evidence of metastatic disease. Patients with metastatic disease or death within the landmark period (3 months after the first nmCRPC evidence) were excluded.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was time from the landmark period to death or metastasis; the secondary outcome was overall survival. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, Kaplan-Meier estimates, and adjusted survival curves were used to evaluate outcome differences by race and ethnicity.

Results

Of 12 992 patients in the cohort, 826 patients identified as Hispanic (6%), 3671 as non-Hispanic Black (28%; henceforth Black), 7323 as non-Hispanic White (56%; henceforth White), and 1172 of other race and ethnicity (9%; henceforth other, including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer). Median time elapsed from nmCRPC to metastasis or death was 5.96 (95% CI, 5.58-6.34) years for Black patients, 5.62 (95% CI, 5.11-6.67) years for Hispanic patients, 4.11 (95% CI, 3.96–4.25) years for White patients, and 3.59 (95% CI, 3.23-3.97) years for other patients. Median unadjusted overall survival was 6.26 (95% CI, 6.03-6.46) years among all patients, 8.36 (95% CI, 8.0-8.8) years for Black patients, 8.56 (95% CI, 7.3-9.7) years for Hispanic patients, 5.48 (95% CI, 5.2-5.7) years for White patients, and 4.48 (95% CI, 4.1-5.0) years for other patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study of patients with nmCRPC suggest that differences in outcomes by race and ethnicity exist; in addition, Black and Hispanic men may have considerably improved outcomes when treated in an equal-access setting.

This cohort study examines clinical outcomes by race and ethnicity in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in an equal access health care setting.

Introduction

Health disparities by race and ethnicity are well documented in the US. Discrimination, adverse social determinants of health, and structural racism all contribute to such disparities,1,2,3 and members of historically marginalized groups can face many barriers to equitable health services, such as inadequate insurance and poor access to care, including culturally appropriate care.1,4,5 Minoritized racial and ethnic groups may also have different rates of prevalence of clinical and genetic prognostic and predictive markers compared with the general population but lack access to comparable marker information due to historic and ongoing underrepresentation in clinical trials.6

Racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer (PC) have been widely observed but are poorly understood. Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer among men in the US, accounting for an estimated 27% of new cancer diagnoses in this population; 1 in 8 men in the US will be diagnosed with PC during his lifetime, and PC is second only to lung cancer in cancer-related mortality among men in the US.7 Black men are more than twice as likely to die of PC-related causes than White men, and mortality rates among Black men treated for PC remain higher than in men of other races even after adjusting for age, stage at diagnosis, insurance status, educational level, household income, comorbidities, and other clinical and nonclinical factors.7,8,9 Black men are more likely than men of other races and ethnicities to be diagnosed with PC, are diagnosed at a younger age, and have a higher incidence of distant-stage disease at diagnosis.10,11 In addition, Black men with local-stage disease face a higher risk of progression after treatment.12 Many explanations have been proposed, with various molecular, genetic, environmental, and even psychological factors suggested as causes of these disparities.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23

Prostate cancer is a notably heterogeneous disease, with the implications for a patient’s quality of life, survival, and need and type of treatment all depending on the disease stage and biological characteristics. Patients with newly diagnosed low-risk disease can be simply monitored for disease progression; this approach spares them from the adverse effects of treatment without affecting their survival.24 Patients with higher risk but localized disease can be treated with local therapy, such as surgery or radiotherapy. In a subset of patients, the disease relapses after local therapy.24 It is typically then treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) until it becomes resistant (ie, castration resistance). At this point, the disease progresses in about half of patients,25,26 metastasizing to involve other organs, such as bone, and leading ultimately to death. Each of these phases requires different diagnostic, surveillance, and treatment modalities, all designed to calibrate treatment to disease risk and improve survival and quality of life while minimizing treatment toxic effects.24

Given this heterogeneity, it is likely that a given disparity-related factor may affect outcomes differently at each point along the disease’s highly variable trajectory. The factors determining whether a patient is screened for PC may well differ from those determining whether they safely undergo active surveillance and differ from the factors leading to the choice to receive second-generation hormonal therapy in the event that they progress to high-risk, castration-resistant disease. Thus, we argue that it is appropriate—and indeed, necessary—to investigate potential disparities at each key milestone of the disease rather than solely at diagnosis.

Studies that have examined racial and/or ethnic disparities in PC in the equal-access Veterans Health Administration (VHA) support this view. Equal-access health care systems strive to address financial barriers to health care and are generally thought to mitigate, although not eliminate, health disparities.1,27,28 Operated by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the VHA provides low-cost care to veterans of the US armed forces and offers services to facilitate access, such as transportation and extended clinic hours.3 More than one-quarter of veterans identify as belonging to racial and/or ethnic minority groups, and the VHA is the largest equal-access system in the US.29 Thus, it serves as a suitable model for studying disparities in the presence of mitigated access barriers, but examinations of PC disparities within the VHA provide no definitive answers. Some studies have documented disparities in diagnosis rate, treatment, and/or outcomes (including mortality),30,31,32 while others have found no such disparities33; one investigation reported that Black men treated with radiotherapy within the VHA had a lower risk of PC-related mortality than men of other races.34 A synthesis of evidence on racial and ethnic disparities in the VA identified 3 studies of disparities related to PC that met inclusion criteria, concluding that there was no evidence of disparities in veterans with PC.5,35,36,37 However, nearly all of the studies focused on disparities in survival from the time of diagnosis, underscoring the need for research on disparities at different stages and states of this highly variable disease.

Thus, we sought to describe outcomes by race and ethnicity in PC in the VHA at the first major milestone, after diagnosis, in the trajectory of advanced PC, that is, the state of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). With nmCRPC, the disease has developed resistance to ADT but has not yet progressed to metastasis, which is lethal. Observation with continued ADT has long been the mainstay of nmCRPC management for patients with stable disease, but progression to metastasis is common, occurring in approximately half of the patients.25,26 Treatment recommendations and the therapeutic landscape of nmCRPC have changed substantially following clinical trials demonstrating the benefits of second-generation hormonal therapy (eg, enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide).38,39,40,41,42,43 However, patients with nmCRPC are often older adults with multiple comorbidities; managing this critical state of PC requires carefully weighing the risks of the disease and the competing potential risks and benefits of available treatments for each individual.44,45 An evidence-based understanding of racial and ethnic disparities in nmCRPC could provide invaluable data to inform these crucial treatment decisions.

Study Objectives

To examine potential racial and/or ethnic disparities in clinical practice, we performed a retrospective, observational cohort study using data from the electronic health care records of a cohort of patients diagnosed with nmCRPC in the VHA. We sought to identify differences in patients’ outcomes by self-identified race and ethnicity within this cohort of patients with nmCRPC in the largest equal-access health care system in the US.

Methods

Cohort Definition

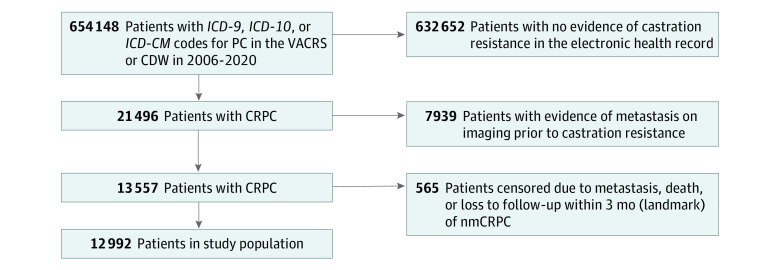

To form the patient population (Figure 1) for this retrospective, observational cohort study, we used validated methods45 to extract electronic health care record data from the VA Cancer Registry System and the VA Corporate Data Warehouse for patients diagnosed with PC between January 1, 2006, and December 30, 2020 (inclusive), and who had progressed to nmCRPC defined by 3 criteria: (1) prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, as defined by the Prostate Cancer Working Group or the American Urological Association45,46,47,48; (2) ongoing androgen deprivation (a serum testosterone level ≤50 ng/dL [to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 0.0347] within the preceding 3 months or receipt of ADT before the next dispensation was due); and (3) no evidence of metastatic disease (eg, in imaging reports).45 We performed a landmark analysis and excluded all patients who progressed to metastatic disease and/or death during a 3-month landmark period following the initial date of evidence of nmCRPC. Individuals were followed up until metastasis, death, or the end of the study observation period (June 30, 2021; electronic health records from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2021, were reviewed). This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. It was deemed exempt and granted a waiver of informed consent by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board because the research meets the specific criteria outlined in 45 CFR 46.116 and is no greater than minimal risk.

Figure 1. Patient Cohort Flow Diagram.

CDW indicates Corporate Data Warehouse; CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision; ICD-10-CM, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification; nmCRPC, nonmetastatic CRPC; and VACRS, Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry System.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was time to either death or metastasis. The secondary outcome was overall survival. To understand practices for the first line of treatment dispensed for nmCRPC and account for sometimes-delayed treatment initiation under community setting conditions, we performed a landmark analysis wherein patients were assigned to groups matching the first treatment they received within 3 months of meeting criteria for nmCRPC. Patients who received only ADT during that period were assigned to the ADT group. Patients without evidence of any treatment were assigned to the nontreated group. To account for any potential immortal time bias, patients who died, had metastatic disease, or were censored within the landmark period were excluded from our analysis.

We evaluated outcomes starting from the landmark time (ie, from 3 months after the nmCRPC date). Summary statistics were obtained after the landmark analysis: descriptive statistics were calculated using mean (SD) or median (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Differences were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance tests. We assessed statistical significance using 2-sided, unpaired testing at a significance level of P = .01.

We used a stratified multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to evaluate outcome differences by race and ethnicity. Covariates that best represented patient, disease, and treatment characteristics at the time of nmCRPC diagnosis and that were available and feasibly extracted from electronic health care records were selected. We included only 1 variable associated with each category to avoid collinearity and potential backdoor confounding. Covariates included age, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and PSA doubling time (PSADT), calculated using established methods.49 We stratified the model by treatment, as patients receiving different treatments would have nonproportional hazards. Missing values were imputed using missForest, a random forest-based model for missing data imputation.50

We used Kaplan-Meier estimates to compare raw (unadjusted) survival differences and adjusted survival curves to estimate differences by race and ethnicity, applying the marginal adjustment approach ggadjustedcurves.51 Median survival times were obtained for the estimates. Data cleaning and analysis were performed in R, version 4.12 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).52

Results

Patients, Disease Characteristics, and Treatment Practices

We identified 12 992 patients who met inclusion criteria. Mean (SD) follow-up time was 4.3 (3.3) years. From a fixed set of categories, 826 patients identified as Hispanic (6%), 3671 as non-Hispanic Black (28%; henceforth Black), 7323 as non-Hispanic White (56%; henceforth White), and 1172 as other race or ethnicity (9%; henceforth other, including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer) (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient Demographic Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 12 992) | Hispanic (n = 826) | Non-Hispanic Black (n = 3671) | Non-Hispanic White (n = 7323) | Other (n = 1172)a | ||

| Age at nmCRPC diagnosis, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 73.0 (9.42) | 74.7 (9.07) | 69.9 (9.57) | 74.0 (9.02) | 74.8 (9.46) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 72 (14) | 75 (14) | 69 (14) | 73 (14) | 74 (14) | |

| Age category at nmCRPC diagnosis, y | ||||||

| <70 | 5217 (39) | 238 (29) | 1970 (54) | 2551 (35) | 364 (31) | <.001 |

| ≥70 | 7869 (61) | 588 (71) | 1701 (46) | 4772 (65) | 808 (69) | |

| Last CCI prior to nmCRPC diagnosis | ||||||

| Mild | 10 353 (80) | 681 (82) | 2898 (79) | 5856 (80) | 918 (78) | .33 |

| Moderate/severe | 2291 (18) | 137 (17) | 681 (19) | 1257 (17) | 216 (19) | |

| Missing | 348 (3) | 8 (1) | 92 (2) | 210 (3) | 38 (3) | |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| Midwest | 3184 (25) | 27 (3) | 662 (18) | 2221 (30) | 274 (23) | <.001 |

| Northeast | 1328 (10) | 36 (4) | 329 (9) | 883 (12) | 80 (7) | |

| South | 5326 (41) | 191 (23) | 2242 (61) | 2470 (34) | 423 (36) | |

| West | 2494 (19) | 164 (20) | 384 (10) | 1592 (22) | 354 (30) | |

| Puerto Rico/Virgin Islands | 463 (4) | 402 (49) | 9 (0.2) | 30 (0.4) | 22 (2) | |

| Missing | 197 (2) | 6 (1) | 45 (1) | 127 (2) | 19 (2) | |

| Prostate-specific antigen doubling time | ||||||

| Unknown | 7447 (57) | 479 (58) | 2164 (59) | 4119 (56) | 685 (58) | .004 |

| Available | 5545 (43) | 347 (42) | 1507 (41) | 3204 (44) | 487 (42) | |

| >10 mo | 3338 (60) | 237 (68) | 932 (62) | 1888 (59) | 281 (58) | |

| ≤10 mo | 2207 (40) | 110 (32) | 575 (38) | 1316 (41) | 206 (42) | |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; nmCRPC, nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer.

Overall, patients’ median age on meeting criteria for nmCRPC was 72 (IQR, 14) years. Black patients were younger (median, 69; IQR, 14 years) than Hispanic (median, 75; IQR, 14 years) or White (median, 73; IQR, 14 years) patients. The population of Black patients was higher in the South (61%) compared with the Midwest (18%), West (10%), and Northeast (9%) regions (P < .001). There were no significant differences in CCI. Black and Hispanic patients were less likely to have high-risk nmCRPC, as defined by a PSADT less than or equal to 10 months. The median time elapsed from the initial PC diagnosis to nmCRPC status was 2.1 (IQR, 3.7) years among all patients, 2.0 (IQR, 3.9) years in Black patients, 2.5 (IQR, 3.7) years in Hispanic patients, and 2.2 (IQR, 3.7) years in White patients. Most patients (60%) were treated in 2013 or thereafter; the eTable in Supplement 1 summarizes treatments received for nmCRPC.

Primary Outcome: Time to Metastasis or Death

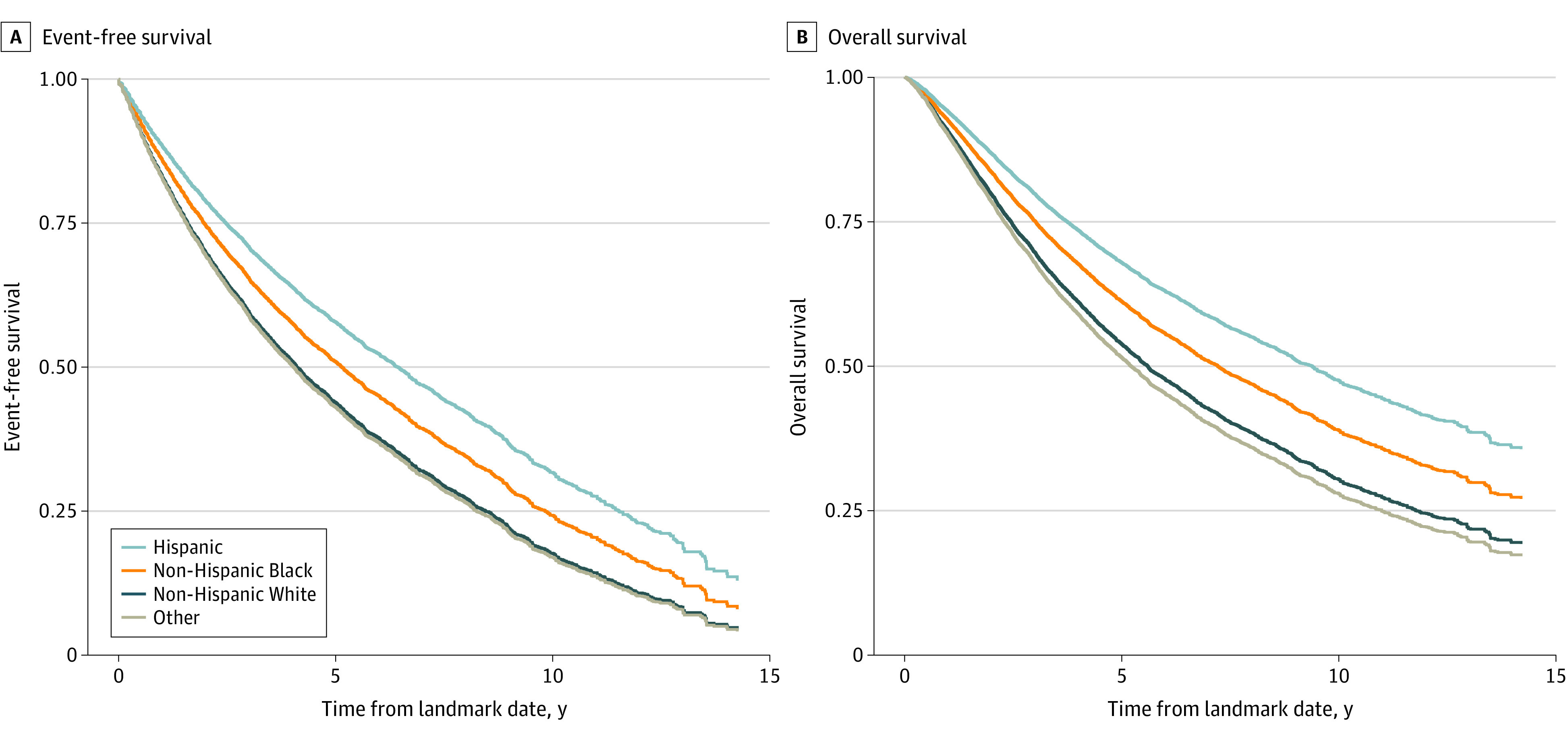

The median time elapsed from nmCRPC to metastasis or death was 5.96 (95% CI, 5.58-6.34; P < .001) years for Black patients, 5.62 (95% CI, 5.11-6.67; P < .001) years for Hispanic patients, 4.11 (95% CI, 3.96-4.25; P < .00) years for White patients, and 3.59 (95% CI, 3.23-3.97; P < .001) years for other patients. Figure 2 shows adjusted survival curves. In a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis (Table 2) adjusting for patient factors (age, CCI) and disease severity (PSADT), Black patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.80-0.90) and Hispanic patients (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.62-0.78) had a reduced risk of metastatic disease or death compared with White patients. In the same analysis, age (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.05), moderate or severe CCI (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.26-1.41), and PSADT less than or equal to 10 months (HR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.53-1.77) were also associated with increased risk of metastasis or death.

Figure 2. Adjusted Survival Curves for Survival by Race and Ethnicity.

Metastasis-free (A) and overall (B) survival. The numbers at risk are not available for adjusted survival curves, because the survival curves are adjusted proportionally with the confounders. The original numbers at risk would not correctly reflect the curves. The same algorithm we used to create survival curves does not provide numbers at risk, because the scaling is working on survival probabilities. To our knowledge, there are no existing algorithms to scale the number of people in such cases. Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer.

Table 2. Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model for Progression to Metastatic Disease or Death.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 0.70 (0.62-0.78) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.85 (0.80-0.90) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | |

| Othera | 1.07 (0.99-1.16) | .09 |

| Age at nmCRPC | ||

| Years | 1.05 (1.04-1.05) | <.001 |

| Last CCI prior to nmCRPC diagnosis | ||

| Mild | 1 [Reference] | |

| Moderate/severe | 1.34 (1.26-1.41) | <.001 |

| PSA doubling time | ||

| >10 mo | 1 [Reference] | |

| ≤10 mo | 1.64 (1.53-1.77) | <.001 |

| Unavailable | 1.24 (1.17-1.32) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; nmCRPC, nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer.

Secondary Outcome: Overall Survival

Median unadjusted overall survival was 6.26 (95% CI, 6.03-6.46; P < .001) years among all patients, 8.36 (95% CI, 8.0-8.8; P < .001) years for Black patients, 8.56 (95% CI, 7.3-9.7; P < .001) years for Hispanic patients, 5.48 (95% CI, 5.2-5.7; P < .001) years for White patients, and 4.48 (95% CI, 4.1-5.0; P < .001) years for other patients. In the VHA, an equal-access health care system, the HR for death among Black individuals compared with White individuals was 0.80 (95% CI, 0.76-0.86; P < .001) (Table 3). For Hispanic individuals, the HR was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.57-0.72; P < .001). Moderate or severe CCI conferred an increased risk of death (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.41-1.58; P < .001), as did PSADT less than or equal to 10 months (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.43-1.67; P < .001).

Table 3. Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model for Overall Survival.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| Hispanic | 0.64 (0.57-0.72) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.80 (0.76-0.86) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | |

| Othera | 1.11 (1.03-1.21) | .01 |

| Age at nmCRPC | ||

| Years | 1.07 (1.06-1.07) | <.001 |

| Last CCI prior to nmCRPC diagnosis | ||

| Mild | 1 [Reference] | |

| Moderate/severe | 1.49 (1.41-1.58) | <.001 |

| PSA doubling time | ||

| >10 mo | 1 [Reference] | |

| ≤10 mo | 1.55 (1.43-1.67) | <.001 |

| Unavailable | 1.18 (1.11-1.25) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; HR, hazard ratio; nmCRPC, nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer.

Discussion

In this study, among patients with nmCRPC in an equal-access system, self-identified Black and Hispanic individuals had better clinical outcomes than White or other patients, including time to metastasis and overall survival. These results expand our understanding of the racial disparities observed in PC. Our comprehensive analysis aimed to identify any existing differences in outcomes by self-identified race or ethnicity at the key disease state of nmCRPC in an equal-access health care system. This analysis differs from previous studies by focusing on nmCRPC, a critical point in the trajectory of PC. It also adjusted for key clinical factors that may act as confounders: patient characteristics, comorbidities, disease risk as captured by a PSADT at the time of castration resistance, and treatment received. In addition, our outcomes included both overall and event-free survival (ie, time to metastasis or death).

The results of our analysis not only add to evidence that differences in PC outcomes by self-identified race and ethnicity exist, they suggest that Black and Hispanic men may actually have considerably improved outcomes compared with men of other races or ethnicities when treated in an equal-access setting. Concordant with that finding, Black men had a significantly lower incidence of high-risk disease as defined by a PSADT less than or equal to 10 months. Black men in the cohort were also younger compared with other groups, in line with established literature.10,11 These findings add to the growing body of evidence that suggests that treatment in an equal-access health care system may eliminate—or even reverse—some of the higher risks of poor outcomes long observed in Black men with PC. Our findings are consistent with other recent studies that found a lack of increased hazard or even a reduced hazard, under certain circumstances, in Black men treated for PC in the VHA.31,33,34 However, our study expands on these reports: our adjusted analyses accounted for treatment, age, CCI, and PSADT, suggesting that Black and Hispanic patients had more favorable outcomes in nmCRPC than did White patients or patients of other races and/or ethnicities in an equal-access setting.

Recent studies, including those by McKay et al34 and Yamoah et al,31 found that Black men in the VHA derived greater benefit from certain types of treatment compared with men of other races. An examination of practice patterns in PC in the VHA identified significant racial disparities in treatment received in the VHA, depending on potential treatment benefit as defined by 10-year life expectancy and disease-specific characteristics; Black patients were more likely than other patients to receive treatment in moderate treatment benefit circumstances, and less likely to be treated in high-benefit situations.32 McKay et al34 and Yamoah et al31 both reported that Black men treated with radiotherapy had more favorable outcomes than White patients whereas Sartor et al53 reported that Black men who received the immunotherapeutic agent sipuleucel-T had improved overall survival compared with White men. Weiner et al13 proposed an explanation for this latter phenomenon, reporting increased plasma cell content and immunoglobulin G expression associated with improved event-free and overall survival in Black men. All therapies examined in this study were National Comprehensive Cancer Network–approved treatments for nmCRPC24; not all were immunotherapies.

In any case, what this study helps clarify is the need to investigate disparities at each of the different stages and states of the heterogeneous disease that is PC, both within and outside equal-access systems. Patient- and disease-specific factors interact with disparities that may manifest and affect outcomes differently at different time points. Thus, focusing studies of disparities and outcomes on the populations of patients at certain crucial points in the disease trajectory will likely yield more illuminating and actionable results than studying disparities across all patients with the disease.

Strengths and Limitations

This study’s strengths include the large demographically representative patient population and its context within an equal-access health care system. Most community setting evidence on nmCRPC comes from studies outside the US54,55,56,57; the few US-based studies have focused on patients treated with apalutamide, and thus may not represent all patients with nmCRPC, but only those with high-risk disease.58,59,60 Evidence from clinical trials is also subject to the latter weakness, in addition to underrepresenting patients who identify as racial and/or ethnic minorities.38,40,42,61,62 The overall time from PC to castration resistance in the cohort in this study was concordant with previous reports.55,63,64 Time to metastasis or death in patients with nmCRPC in community setting studies65,66,67 tends to be longer than those reported in clinical trials due to the higher stringency of follow-up in clinical trial settings, in both the nature and frequency of surveillance for metastasis.

Because some of the study’s findings were unexpected, data extraction and statistical analyses were performed more than once, from start to finish, and were reviewed by multiple qualified researchers, resulting in rigorous data handling and analytical processes. All of these characteristics support the conclusions drawn from the study’s results.

The study also has some limitations. The study population was confined to veterans; although the population of male US veterans is demographically representative of the male US population at large, results from this study may not be generalizable to the full population. In addition, it is possible that there could be patients who were diagnosed but unaccounted for in this study. Finally, notwithstanding their rigor, data extraction and analytical processes were restricted to the data available in the electronic health care records, and thus subject to the limitations of those data.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study of patients with nmCRPC treated in an equal-access setting found that men of self-reported Black race and/or Hispanic ethnicity had significantly improved overall survival compared with patients of other races and ethnicities. In addition, Black patients and Hispanic patients with nmCRPC had notably longer time to metastasis than White and other populations. Our findings provide evidence that the racial and ethnic disparities long observed in PC may arise from systemic socioeconomic inequity rather than molecular or genetic factors.

eTable. Treatments for nmCRPC by Race, Ethnicity, and Epoch

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong MS, Hoggatt KJ, Steers WN, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in mortality across the Veterans Health Administration. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):99-108. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler M, McCreedy E, Schwer N, et al. Improving Cultural Competence to Reduce Health Disparities. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson K, Anderson J, Boundy E, Ferguson L, McCleery E, Waldrip K. Mortality disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups in the Veterans Health Administration: an evidence review and map. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):e1-e11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldrighetti CM, Niemierko A, Van Allen E, Willers H, Kamran SC. Racial and ethnic disparities among participants in precision oncology clinical studies. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2133205. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, et al. Association of Black race with prostate cancer–specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):975-983. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen W, Luckenbaugh AN, Bayley CE, Penson DF, Shu XO. Racial disparities in mortality for patients with prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2021;127(9):1517-1528. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African American/Black people 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(3):202-229. doi: 10.3322/caac.21718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel DA, O’Neil ME, Richards TB, Dowling NF, Weir HK. Prostate cancer incidence and survival, by stage and race/ethnicity—United States, 2001-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(41):1473-1480. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6941a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundi D, Ross AE, Humphreys EB, et al. African American men with very low-risk prostate cancer exhibit adverse oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy: should active surveillance still be an option for them? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(24):2991-2997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.0302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner AB, Vidotto T, Liu Y, et al. Plasma cells are enriched in localized prostate cancer in Black men and are associated with improved outcomes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):935. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21245-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gong T, Jaratlerdsiri W, Jiang J, et al. Genome-wide interrogation of structural variation reveals novel African-specific prostate cancer oncogenic drivers. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s13073-022-01096-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavura MY, Huang FW. How cancer risk SNPs may contribute to prostate cancer disparities. Cancer Res. 2021;81(14):3764-3765. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith ZL, Eggener SE, Murphy AB. African-American prostate cancer disparities. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18(10):81. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0724-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebbeck TR. Prostate cancer genetics: variation by race, ethnicity, and geography. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2017;27(1):3-10. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SK, Lillard JW Jr, Singh R. Molecular basis for prostate cancer racial disparities. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2017;22(3):428-450. doi: 10.2741/4493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhary AK, O’Malley J, Kumar S, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and prostate cancer racial disparities among American men. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2017;9(1):154-164. doi: 10.2741/s479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham-Miranda J, Awasthi S, Yamoah K. Immunologic disparities in prostate cancer between American men of African and European descent. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;164:103426. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhardwaj A, Srivastava SK, Khan MA, et al. Racial disparities in prostate cancer: a molecular perspective. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2017;22(5):772-782. doi: 10.2741/4515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hur J, Giovannucci E. Racial differences in prostate cancer: does timing of puberty play a role? Br J Cancer. 2020;123(3):349-354. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0897-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuevas AG, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Cofie L, Zaitsu M, Allen J, Williams DR. Placing prostate cancer disparities within a psychosocial context: challenges and opportunities for future research. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(5):443-456. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01159-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: prostate cancer, version 1.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20(12):1288-1298. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2022.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amling CL, Bergstralh EJ, Blute ML, Slezak JM, Zincke H. Defining prostate specific antigen progression after radical prostatectomy: what is the most appropriate cut point? J Urol. 2001;165(4):1146-1151. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66452-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WR, Hanks GE, Hanlon A. Increasing prostate-specific antigen profile following definitive radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: clinical observations. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(1):230-238. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danaei G, Rimm EB, Oza S, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJ, Ezzati M. The promise of prevention: the effects of four preventable risk factors on national life expectancy and life expectancy disparities by race and county in the United States. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kullgren JT, McLaughlin CG, Mitra N, Armstrong K. Nonfinancial barriers and access to care for U.S. adults. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1, pt 2):462-485. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01308.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes P. Diversity, equity, inclusion—VA goals. US Dept of Veterans Affairs. July 22, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://news.va.gov/92022/diversity-equity-inclusion-va-goals/

- 30.Hudson MA, Luo S, Chrusciel T, et al. Do racial disparities exist in the use of prostate cancer screening and detection tools in veterans? Urol Oncol. 2014;32(1):34.e9-34.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamoah K, Lee KM, Awasthi S, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer outcomes in the Veterans Affairs health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2144027. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rude T, Walter D, Ciprut S, et al. Interaction between race and prostate cancer treatment benefit in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2021;127(21):3985-3990. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Survival of African American and non-Hispanic White men with prostate cancer in an equal-access health care system. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1683-1690. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKay RR, Sarkar RR, Kumar A, et al. Outcomes of Black men with prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2021;127(3):403-411. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daskivich TJ, Kwan L, Dash A, Litwin MS. Racial parity in tumor burden, treatment choice and survival outcomes in men with prostate cancer in the VA healthcare system. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015;18(2):104-109. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman VL, Durazo-Arvizu R, Arozullah AM, Keys LC. Determinants of mortality following a diagnosis of prostate cancer in Veterans Affairs and private sector health care systems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1706-1712. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham-Steed T, Uchio E, Wells CK, Aslan M, Ko J, Concato J. “Race” and prostate cancer mortality in equal-access healthcare systems. Am J Med. 2013;126(12):1084-1088. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hussain M, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Enzalutamide in men with nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2465-2474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sternberg CN, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. ; PROSPER Investigators . Enzalutamide and survival in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2197-2206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2003892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. ; SPARTAN Investigators . Apalutamide treatment and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1408-1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith MR, Saad F, Chowdhury S, et al. Apalutamide and overall survival in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79(1):150-158. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fizazi K, Shore N, Tammela TL, et al. ; ARAMIS Investigators . Darolutamide in nonmetastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(13):1235-1246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1815671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fizazi K, Shore ND, Tammela T, et al. Overall survival results of phase III ARAMIS study of darolutamide added to ADT for nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(suppl):5514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.5514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gul A, Garcia JA, Barata PC. Treatment of non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: focus on apalutamide. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:7253-7262. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S165706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halwani AS, Rasmussen KM, Patil V, et al. Real-world practice patterns in veterans with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2020;38(1):1.e1-1.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rasmussen KM, Patil V, Morreall D, et al. Castration-resistant prostate cancer—not only challenging to treat, but difficult to define. Fed Pract. 2022;39(4):S17. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowrance WT, Murad MH, Oh WK, Jarrard DF, Resnick MJ, Cookson MS. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: AUA guideline amendment 2018. J Urol. 2018;200(6):1264-1272. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.07.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scher HI, Morris MJ, Stadler WM, et al. ; Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3 . Trial design and objectives for castration-resistant prostate cancer: updated recommendations from the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 3. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1402-1418. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, et al. Death in patients with recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: prostate-specific antigen doubling time subgroups and their associated contributions to all-cause mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(13):1765-1771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. missForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112-118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adjusted survival curves for Cox proportional hazards model. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://search.r-project.org/CRAN/refmans/survminer/html/ggadjustedcurves.html

- 52.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2022. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.R-project.org/

- 53.Sartor O, Armstrong AJ, Ahaghotu C, et al. Survival of African-American and Caucasian men after sipuleucel-T immunotherapy: outcomes from the PROCEED registry. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23(3):517-526. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-0213-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aly M, Leval A, Schain F, et al. Survival in patients diagnosed with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a population-based observational study in Sweden. Scand J Urol. 2020;54(2):115-121. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2020.1739139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arnold P, Penaloza-Ramos MC, Adedokun L, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes for patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22151. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-01042-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Afshar M, Evison F, James ND, Patel P. Shifting paradigms in the estimation of survival for castration-resistant prostate cancer: a tertiary academic center experience. Urol Oncol. 2015;33(8):338.e1-338.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malone S, Wallis CJD, Lee-Ying R, et al. Patterns of care for non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a population-based study. BJUI Compass. 2022;3(5):383-391. doi: 10.1002/bco2.158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hussain A, Jiang S, Varghese D, et al. Real-world burden of adverse events for apalutamide- or enzalutamide-treated non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients in the United States. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09364-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lowentritt B, Brown G, Pilon D, et al. Real-world prostate-specific antigen response and treatment adherence of apalutamide in patients with non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urology. 2022;166:182-188. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2022.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bivins VM, Durkin M, Khilfeh I, et al. Early prostate-specific antigen response among Black and non-Black patients with advanced prostate cancer treated with apalutamide. Future Oncol. 2022;18(32):3595-3607. doi: 10.2217/fon-2022-0791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paller CJ, Olatoye D, Xie S, et al. The effect of the frequency and duration of PSA measurement on PSA doubling time calculations in men with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17(1):28-33. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lillard JW Jr, Moses KA, Mahal BA, George DJ. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: a literature review. Cancer. 2022;128(21):3787-3795. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6(2):76-85. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharifi N, Dahut WL, Steinberg SM, et al. A retrospective study of the time to clinical endpoints for advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2005;96(7):985-989. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05798.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Banefelt J, Liede A, Mesterton J, et al. Survival and clinical metastases among prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(4):442-447. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.D’Amico AV, Moul J, Carroll PR, Sun L, Lubeck D, Chen MH. Surrogate end point for prostate cancer specific mortality in patients with nonmetastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;173(5):1572-1576. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000157569.59229.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Metwalli AR, Rosner IL, Cullen J, et al. Elevated alkaline phosphatase velocity strongly predicts overall survival and the risk of bone metastases in castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(6):761-768. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Treatments for nmCRPC by Race, Ethnicity, and Epoch

Data Sharing Statement