Abstract

Depression is highly prevalent during the menopause transition (perimenopause), and often presents with anxious and anhedonic features. This increased vulnerability for mood symptoms is likely driven in part by the dramatic hormonal changes that are characteristic of the menopause transition, as prior research has linked fluctuations in estradiol (E2) to emergence of depressed mood in at risk perimenopausal women. Transdermal estradiol (TE2) has been shown to reduce the severity of depression in clinically symptomatic women, particularly in those with recent stressful life events. This research extends prior work by examining the relation between E2 and reward seeking behaviors, a precise behavioral indicator of depression. Specifically, the current study utilizes a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled design to investigate whether mood sensitivity to E2 flux (“hormone sensitivity”) predicts the beneficial effects of TE2 interventions on reward seeking behaviors in perimenopausal women, and whether recent stressful life events moderate any observed associations.

Method:

Participants were 66 women who met standardized criteria for being early or late perimenopausal based on bleeding patterns. Participants were recruited from a community sample; therefore, mood symptoms varied across the continuum and the majority of participants did not meet diagnostic criteria for a depressive or anxiety disorder at the time of enrollment. Hormone sensitivity was quantified over an 8-week baseline period, using within-subjects correlations between repeated weekly measures of E2 serum concentrations and weekly anxiety (State Trait Anxiety Inventory) and anhedonia ratings (Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale). Women were then randomized to receive 8 weeks of TE2 (0.1mg) or transdermal placebo, and reward-seeking behaviors were assessed using the Effort-Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT).

Results:

Participants who were randomized to receive transdermal estradiol and who demonstrated greater anxiety sensitivity to E2 fluctuations at baseline, demonstrated more reward seeking behaviors on the EEfRT task. Notably, the strength of the association between E2-anxiety sensitivity and post-randomization EEfRT for TE2 participants increased when women experienced more recent stressful life events and rated those events as more stressful. E2-anhedonia sensitivity was not associated with reward-seeking behaviors.

Conclusion:

Perimenopausal women who are more sensitive to E2 fluctuations and experienced more recent life stress may experience a greater benefit of TE2 as evidenced by an increase in reward seeking behaviors.

Keywords: perimenopause, estradiol, hormone sensitivity, reward seeking behaviors, anxiety, anhedonia

1. Introduction

Depression is highly prevalent during the menopause transition (perimenopause), with up to 25 percent of women reporting clinically impairing symptoms (Gallicchio et al., 2007). Despite receiving far less attention than depressed mood in perimenopausal research, anxiety and anhedonia are also common complaints in midlife women and often present alongside depressed mood in perimenopausal depressive disorders (Bromberger et al., 2013; Glazer et al., 2002; Gordon & Girdler, 2014; Strauss, 2011). Notably, risk for both depression and anxiety are elevated in perimenopausal women, with rates higher compared to premenopausal women (Bromberger et al., 2013; Freeman et al., 2007; Mulhall et al., 2018). This increased vulnerability for mood disorders is hypothesized to be driven in part by the dramatic hormonal changes that are characteristic of the menopause transition (Gordon et al., 2021; McKinlay et al., 1992; Schmidt et al., 2015). During the 5-to-7-years leading up to the last menstrual period, estradiol (E2) levels become more erratic (fluctuating from hypo-to hyper-gonadal levels) within the context of an overall decline in E2 levels (Burger et al., 1999; Burger et al., 2002; Grub et al., 2021; McKinlay et al., 1992; Metcalf et al., 1982; Metcalf, 1983). Recent data have linked these normative changes in E2 variability to the emergence of depression symptoms in women who are highly sensitive to hormonal fluctuations. A seminal study by Schmidt and colleagues (2015) found that experimentally induced E2 withdrawal, mimicking the decline in E2, triggers depression onset in women with a history of depression, but not healthy controls. Gordon and colleagues (2021) expanded upon this work by utilizing observational methods to demonstrate that there are individual differences in mood sensitivity to hormone flux or “hormone sensitivity”, quantified as within-subjects correlations between weekly E2 levels and mood symptoms, predicts the onset of depression. Notably, this vulnerability to experience elevated mood symptoms as E2 levels fluctuate is also amplified when women experienced recent stressful life events (Gordon et al., 2015; Gordon et al., 2016; Gordon et al., 2018). The role of E2 in the pathogenesis of perimenopausal mood disorders is further underscored by studies finding that administration of transdermal estradiol (TE2) reduces the severity of depression in clinically symptomatic women and prevents the emergence of depressive episodes in women in the menopause transition (Rubinow et al., 2015; Gordon et al., 2018). However, a paucity of research has investigated possible pathways that may underly the relationship between TE2 administration and depression in perimenopausal women.

Impairment in reward seeking behaviors is one candidate pathway that has been implicated in the emergence of perimenopausal depression (Diekhof, 2018; Thomas et al., 2014). Reductions in reward seeking behaviors are a core component of anhedonia, reflecting a decreased motivation to seek out rewarding stimuli, especially when reward is contingent on effort expenditure (Treadway & Zald, 2011). These motivational deficits can be distinguished from other consummatory aspects of reward behavior, including hedonic capacity, which refers to experiencing typically enjoyable stimuli as less pleasurable (Treadway & Zald, 2011). Although both features of anhedonia are commonly observed in depression and confer transdiagnostic risk for internalizing mood disorders (Grillo, 2016; Nusslock & Alloy, 2017; Winer et al., 2017), they are supported by unique underlying neural circuitry (Treadway & Zald, 2013). Changes in reward seeking behaviors are of particular interest during the menopause transition because evidence from human and preclinical literatures suggests that reward processing is modulated by E2 (Diekhof, 2018). E2 acts upon numerous receptors throughout the brain, including dopamine receptors in the ventral striatum and other brain regions implicated in the neural circuitry of reward processing and motivation (Diekof, 2018; Treadway & Zald, 2011; Nusslock & Alloy, 2017). The impact of E2 signaling on reward processing may therefore contribute to emergence or exacerbation of depression symptomatology in perimenopause.

Research on the influence of estradiol on reward motivation in perimenopause, however, is critically lacking. One study has investigated the influence of exogenous E2 on reward processing in perimenopausal women (Thomas et al., 2014). In a double blind, crossover placebo-controlled, randomized study of 13 perimenopausal women, Thomas and colleagues (2014) found that 21 days of hormone therapy (oral 17β-estradiol plus intermittent oral progestin) increased activity in the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, relative to placebo, during reward anticipation. Women were also faster to respond for reward outcomes when receiving hormone therapy, demonstrating an increase in reward seeking behaviors. An important next step in this line of research is to advance our understanding of the influence of endogenous E2 fluctuations on reward processing in perimenopausal women, and to build upon the work of Thomas and colleagues (2014) by identifying predictors of the beneficial effects of TE2 on reward seeking behaviors in larger samples of women. Additionally, the majority of past studies have measured hormone sensitivity by investigating incidents of major depression disorder or global ratings of depression in relation to E2 in perimenopausal women (Freeman et al., 2007, Gordon et al., 2015; Gordon et al., 2021). However, depression in the menopause transition is heterogenous and often presents clinically with anxious and anhedonic features (Bromberger et al., 2013; Glazer et al., 2002; Gordon & Girdler, 2014; Strauss, 2011). More work is thus needed to consider a broader range of symptoms, including anxiety and anhedonia, when investigating the influence of E2 on perimenopausal mood changes.

1.1. The Current Study

The current study addresses these key gaps in the literature by assessing the degree to which baseline hormone sensitivity (i.e., individual differences in anxiety and anhedonia symptom vulnerability to endogenous E2 flux) predicts reward seeking behaviors in perimenopausal women, and whether this association differs between participants randomized to a TE2 condition versus a placebo condition. Because recent stressful life events are a potent moderator of hormone sensitivity and the efficacy of TE2 (Lozza-Fiacco et al., 2022; Gordon et al., 2016), as a secondary aim of the study we examine whether stressful experiences moderate observed associations between hormone sensitivity and reward seeking behaviors.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

One hundred and seven medically healthy, perimenopausal women were recruited as part of a randomized clinical trial (NCT03003949). The primary aim of the randomized clinical trial was to test the effects of individual differences to endogenous E2 fluctuations and TE2 administration (versus placebo) on anxiety and anhedonia symptoms (primary outcomes). Results are reported in Lozza-Fiacco et al., (2022). In the current report we examine the effects of sensitivity to E2 fluctuations and TE2 administration on reward seeking behavior assessed by performance on the Effort Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT) (secondary outcome), and whether recent stressful life events moderated these relationships.

Women who were 46 to 60 years of age, meeting Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW+10) reproductive staging criteria for early or late menopause transition (Harlow et al., 2012) and were eligible to receive transdermal estradiol, were recruited through advertisements, university email announcements, and flyers. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in the Supplement. All data were collected at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill School of Medicine. Study protocols were reviewed and approved by the UNC Biomedical Institutional Review Board (IRB 16-1731) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Recruitment began in January 2017 and ended March 2020, after which the study was terminated prematurely due to COVID-19 restrictions on clinical research. Despite the premature termination of the study, power analyses (sensitivity analyses in G*Power) confirmed that power was maintained to detect small-to-medium effects of anxiety and anhedonia (tested as continuous predictors) and medium-to-large effects of treatment condition (tested as a dichotomous predictor) when testing the primary aims of the parent grant (reported in Lozza-Fiacco et al., 2022). Sensitivity analyses were based on intraclass correlation (ICC) for repeated outcome measures and a design-corrected sample size. Eighty-two women began the randomization phase and 67 completed the 16-week study protocol. One participant did not complete the assessment of reward seeking behaviors during the post-randomization study visit, thus 66 participants were included in the current analyses.

Participants included in the current report were an average of 49.3 years of age at the time of recruitment (SD = 2.8 years). Additional descriptive information on participant characteristics is available in Table 1. Participants in the placebo condition on average were slightly older than participants in the active TE2 condition although STRAW reproductive stage did not differ between groups. Baseline sample characteristics did not significantly differ between the randomized groups on any other factors (all p’s > .05) (see Supplementary Table 1 for additional details).

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics

| TE2 Group (n = 32) |

Placebo Group (n = 34) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| Age (in years) | 48.6 | 2.9 | 50.0 | 2.5 | 2.17 | .034 |

| Number of children | 1.7 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.84 | .404 |

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | p | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | 3.60 | .166 | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 22 | 68.8 | 29 | 85.3 | ||

| Black | 8 | 25.0 | 5 | 14.7 | ||

| Asian | 2 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ethnicity | 0.29 | .591 | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 | 3.1 | 2 | 5.9 | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 31 | 96.9 | 32 | 94.1 | ||

| Household income (gross family income over the past year in USD) | 1.29 | .201 | ||||

| $39,999 or less | 3 | 9.4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| $40,000 to $79,999 | 10 | 31.3 | 8 | 23.5 | ||

| $80,000 to $99,999 | 3 | 9.4 | 7 | 20.9 | ||

| $100,000 to $159,999 | 9 | 28.1 | 12 | 35.3 | ||

| $160,000 or more | 5 | 15.6 | 7 | 20.6 | ||

| Missing | 2 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Education | 2.34 | .505 | ||||

| High school diploma | 2 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Some college/associate degree/trade school | 7 | 21.9 | 8 | 23.5 | ||

| 4-year college degree | 12 | 37.5 | 15 | 44.1 | ||

| Post-graduate degree | 11 | 34.4 | 11 | 32.4 | ||

| STRAW+10 Stage | 1.18 | .556 | ||||

| Early perimenopause (STRAW −2) | 12 | 37.5 | 9 | 26.5 | ||

| Late perimenopause (STRAW −1) | 13 | 40.6 | 18 | 52.9 | ||

| Partial hysterectomy or ablation | 7 | 21.9 | 7 | 20.6 | ||

| Current depression disorder | 2 | 6.3 | 4 | 11.8 | 0.61 | .436 |

| Past depression disorder | 9 | 28.1 | 8 | 23.5 | 0.18 | .670 |

| Current anxiety disorder | 7 | 21.9 | 8 | 23.5 | 0.03 | .873 |

| Past anxiety disorder | 3 | 9.4 | 2 | 5.9 | 0.29 | .592 |

2.2. Procedure

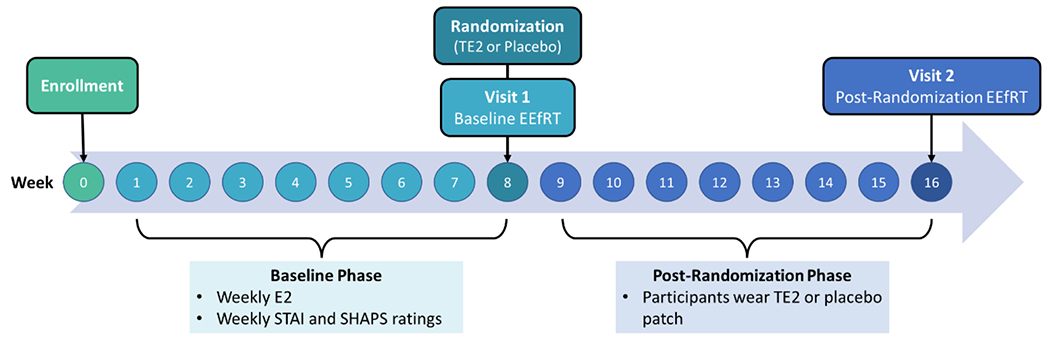

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design was employed. Participants were randomized into either a TE2 arm (0.1 mg E2/24 hours) or a transdermal placebo arm, with parallel allocation between study groups. The study consisted of several sequential study phases: 1) a screening and enrollment period, 2) an 8-week baseline period (referred to as the “baseline phase”), at the end of which women were randomized using a 1:1 allocation to the active, TE2, or placebo arm, and 3) an 8-week post-randomization period (referred to as the “post-randomization phase”). Over the course of the 16-week protocol, staff visited participants’ homes weekly to collect blood samples and administer questionnaires assessing anxiety and anhedonia. At 8- and 16-weeks, women attended a study visit where they completed the EEfRT task (see Figure 1). All participants underwent medical screening, including vitals and history, a gynecological exam, and a screening mammogram.

Figure 1.

Overview of study design.

Note. STAI = State Trait Anxiety Inventory. SHAPS = Snaith Hamilton Pleasure Scale. TE2 = transdermal estradiol. E2 = estradiol. EEfRT = Effort-Expenditure for Rewards Task.

2.2.1. Intervention

Following the 8-week baseline phase, women who were randomized to the active treatment condition (n = 32) applied a weekly TE2 patch (Alvogen) [0.1mg E2/24 hours for 8 weeks] and took oral micronized progesterone after the 8-week post-randomization period and asynchronous with any study assessments in order to prevent endometrial hyperplasia (200mg/day of Prometrium for 12 days). Women randomized to the placebo condition (n = 34) followed the same regimen using placebo patches that were similar in appearance to the TE2 patches, and took placebo capsules (Capsugel Orange, Size AA, DB Capsules). Patches were dispensed in a blinded fashion in individually wrapped packages without manufacturer branding. Pills were dispensed in blinded capsules.

To monitor adherence, study personnel confirmed patch use at each weekly visit. Participants recorded dates of patch placement and removal and returned all used and unused patches at the week 16 laboratory session. At each visit, side effects and adverse events were monitored (see Lozza-Fiacco et al., 2022 for additional details).

2.2.2. Randomization

The study biostatistician created the randomization scheme and assigned participants to intervention conditions. The Investigational Drug Services of UNC managed the randomization and blinded dispensing of patches and capsules. The first author performed analyses and was unblinded after study discontinuation. The first author did not have contact with participants, nor access to identifiable information. All outcome assessors remained blinded throughout the protocol.

Participants randomized to the placebo condition and included in the current study analyses on average were older (t = 2.2, p = .034) and reported experiencing a greater number of severe stressful life events (t = 2.10, p = .041) than participants in the active TE2 condition. Sample characteristics and study measures collected during the baseline phase of the study did not differ between the randomized groups on any other factors, including baseline anxiety and anhedonia scores, baseline hormone sensitivity strength, baseline EEfRT, or total number or impact ratings of recent stressful life events (all p’s > .05) (see Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2 for additional details).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for weekly mood ratings, hormone sensitivity strength, and EEfRT performance at baseline and post-randomization timepoints.

| Study Measures | TE2 Group (n = 32) |

Placebo Group (n = 34) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | ||||||

| Baseline STAI | 30.66 | 8.05 | 33.79 | 9.49 | 1.44 | .155 |

| Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) | ||||||

| Baseline SHAPS | 19.86 | 5.71 | 21.50 | 5.83 | 1.16 | .252 |

| Hormone Sensitivity Strength | ||||||

| Baseline E2-STAI sensitivity | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.24 | −1.53 | .132 |

| Baseline E2-SHAPS sensitivity | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.20 | −0.87 | .388 |

| Effort-Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT) | ||||||

| Baseline EEfRT | 0.35 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.16 | .872 |

| Post-randomization EEfRT | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.21 | 0.29 | .770 |

| Recent Stressful Life Events (SLEs) | ||||||

| Number of SLEs | 1.50 | 1.10 | 1.82 | 1.71 | 0.91 | .369 |

| Number of severe SLEs | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 2.10 | .041 |

| SLE impact score | 3.06 | 1.13 | 3.27 | 1.05 | 0.68 | .498 |

Note. STAI and SHAPS scores reflect average ratings during the baseline phase of the study (weeks 0-8). EEfRT scores are the proportion of trials in which a participant selected the hard choice.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Factors

Sociodemographic characteristics, including participant age, years of education, household income, race/ethnicity, and number of children, were assessed during structured interviews. Selected modules of the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID-RV) for DSM-5 disorders were administered to assess whether women met criteria for current and past anxiety or depression disorders.

2.3.2. Weekly Mood Ratings

2.3.2.1. Anxiety Symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms were assessed weekly using the state version of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a 20-item, self-report measure of current, general anxiety symptoms (Spielberger et al., 1970). Participants were instructed to rate items (e.g., “I feel tense”, “I feel nervous”) on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so), indicating how they feel “right now”. Anxiety absent items were reverse coded. Final sum scores could range from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater levels of anxiety symptoms (see Table 2 for descriptive information on STAI scores in the current study sample). The STAI is a reliable and well validated measure of anxiety symptoms (Spielberger, 1983).

2.3.2.2. Anhedonia Symptoms.

Anhedonia symptoms were assessed weekly using the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS), a 14-item, self-report measure of hedonic capacity or positive valence (Snaith et al., 1995). Participants rated measure items (e.g., “I would enjoy being with my family or close friends”, “I would find pleasure in my hobbies and pastimes”) using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). Anhedonia absent items were reverse coded. The ordinal scoring of Franken and colleagues (2007) was applied, and final sum scores could range from 14 to 56, with higher scores indicating greater levels of anhedonia (see Table 2 for descriptive information on SHAPS scores in the current study sample).

2.3.3. Recent Stressful Life Events

Recent stressful life events (SLEs) were assessed using a modified, 30-item version of the Life Experiences Survey (LES) (Sarason et al., 1978). Participants were asked to rate whether specific life events (e.g., marital separation, death of family member) occurred over the past 6 months. The list of stressful life events was modified to only include events that are considered moderately to severely stressful based on previous studies (Leserman et al., 2002; Leserman et al., 1997; Leserman et al., 2008). A sum score was calculated, reflecting the total number of recent stressful life events (see Table 2 for descriptive information on LES scores in the current study sample). A subset of these items are considered to be very stressful life events (e.g., being physically attacked or having one’s life threatened, being sexually abused or assaulted), and were used to generate a sum score of the number of severely stressful life events. Participants also provided ratings of how stressful each stressful life event was when it occurred using a 5-point Likert scale, rating from not stressful (1) to extremely stressful (5). Ratings of the perceived stress of each event were averaged to create an impact score. The LES is a reliable measure of anxiety symptoms (Spielberger, 1983), and has been previously utilized in studies of perimenopausal mood disorders and hormone sensitivity (Gordon et al., 2016).

2.3.4. Estradiol Assessment

Blood samples were collected during home visits and were immediately transported to the study laboratory, were blood clotted at room temperature and were then centrifuged and aliquoted. Serum samples were stored at −80°C. E2 was analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute San Juan Capistrano, CA). Intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for E2 were < 3.41% and inter-assay CV’s < 4.06%. The lower limit of quantitation (LOD) was 2 pg/ml and levels below LOD were set at half the detection limit (Nave et al., 2018).

2.3.5. Baseline Hormone Sensitivity

E2-STAI sensitivity strength and E2-SHAPS sensitivity strength were computed during the baseline phase (i.e., prior to randomization to TE2 or placebo groups) utilizing existing methods for measuring E2 hormone sensitivity strength in the perimenopausal period (Gordon et al., 2020). Weekly E2 levels were person-centered (i.e., an individual’s average E2 level was subtracted from each weekly E2 measurement). A positive value thus indicates that at that timepoint, E2 was higher than the participant’s mean E2 concentration, and a negative value indicates that the weekly E2 value fell below the participant’s mean. Variability in person-centered E2 values across the baseline phase are presented visually in Supplementary Figure S1. We additionally calculated the absolute value of each person centered E2 variables to reflect only the magnitude at which an E2 value deviated from a participant’s average E2 concentrations. Both the person-centered E2 values and absolute person-centered E2 values were then correlated with the eight respective, weekly mood ratings (i.e., STAI and SHAPS) across the baseline phase. These calculations thus yielded four within-subject correlation coefficients for each participant: 1) an E2-STAI correlation, 2) an absolute E2-STAI correlation, 3) an E2-SHAPS correlation, and 4) an absolute E2-SHAPS correlation. For each mood measure, the correlation coefficient with the largest magnitude was selected. For example, a participant with an E2-STAI correlation of −.5 and an absolute E2-STAI correlation of .7 would have an E2-STAI sensitivity strength of .7. The rationale for this approach is based in prior experimental and observational work which demonstrate that some individuals are sensitive to increases or decreases in E2 whereas others are sensitive to change regardless of direction (Andersen et al., 2022; Gordon et al., 2020; Schmidt et al., 2015). E2-STAI sensitivity strength and E2-SHAPS sensitivity strength are thus defined as the absolute value of a person’s largest E2-anxiety and E2-anhedonia correlation coefficient respectively and describe an individual’s maximum anxiety and anhedonia sensitivity to E2 concentrations (ranging from 0 to 1).

2.3.6. Behavioral Assessment of Reward Motivation

Participants completed the Effort-Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT) (Treadway et al., 2009) during the baseline and post-randomization visit. The EEfRT task is a behavioral assessment of reward motivation and effort-based decision making that indexes willingness to expend effort to obtain monetary rewards under varying conditions of reward probability and magnitude (see Treadway et al., 2009 for full task description). At the start of each trial, participants were presented with a choice. They could either complete a “hard” version of the task (make 100 button presses with their non-dominant little finger within 21 seconds) or an “easy” version of the task (make 30 button presses using their dominant index finger within 7 seconds). If a participant successfully completed an easy trial, they were eligible to win $1. If a participant successfully completed a hard trial, they were eligible to win between $1.24 and $4.30. Monetary rewards were only given for some, designated “win” trials. In order to help participants anticipate which trials may be win trials, one of the following accurate probability cues were presented on-screen at the beginning of each trial: “88%” probability of a win trial, “50%”, or “12%”. These probability levels applied to both easy and hard trials, and there were equal proportions of each probability level across the experiment. All subjects received trials presented in the same randomized order. On average, participants completed 47 trials at the baseline assessment (M = 47.1, SD = 9.1) and 49 trials at the post-randomization assessment (M = 48.7, SD = 4.8). The proportion of hard task choices was used as the measure of reward motivation in study analyses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Pearson’s correlations and t-tests were used to identify factors that might influence post-randomization EEfRT outcomes. Tested variables included household income, vasomotor motor symptoms at baseline and at the post-randomization assessment timepoint (assessed via the vasomotor symptoms scale of the Greene Climacteric Scale; Greene, 2008), and baseline EEfRT performance. Variables were included in subsequent analyses if they were associated with EEfRT at the p < .10 level of significance. As shown in Table S1 only baseline EEfRT performance met inclusion criteria as a covariate and was included in all linear regression models in order to account for individual differences in baseline performance on the task.

Preliminary analyses were conducted using bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients, assessing the associations between study variables. Linear regression models were run to test the primary hypothesis that hormone sensitivity predicted post-randomization EEfRT for women randomized to the TE2 condition. First, linear regression models were run with the anxiety and anhedonia hormone sensitivity variables (E2-STAI sensitivity and E2-SHAPS sensitivity respectively) tested as predictors in separate models. Analyses were first stratified by randomized group (i.e., regression models were run separately for the TE2 and placebo conditions). Results from stratified analyses were then further probed by testing whether the interaction between randomized group and hormone sensitivity (i.e., E2-STAI sensitivity or E2-SHAPS sensitivity) predicted EEfRT outcomes in the full sample. Finally, for stratified linear regression models in which hormone sensitivity significantly predicted post-randomization EEfRT, we also tested whether the number of experienced stressful life events or the subjective impact rating of the stressful life events moderate this association in secondary, exploratory analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate Correlations

Average STAI and SHAPS scores across the 8-week baseline period were moderately correlated (r = .54, p < .001). E2-STAI sensitivity and E2-SHAPS sensitivity during the baseline period were weakly correlated (r = .37, p = .007). The proportion of hard choices on the baseline EEfRT task was strongly associated with the proportion of total hard choices at the post-randomization visit for participants in the placebo group (r = .85, p < .001) and the TE2 group (r = .78, p < .001). Bivariate correlations between the hormone sensitivity variables and EEfRT scores are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

3.2. Testing of Study Aims

3.2.1. E2-STAI Sensitivity Strength and Post-Randomization EEfRT

Greater E2-STAI sensitivity strength predicted a higher proportion of hard choice trials on the EEfRT task at the post-randomization visit for participants randomized to the TE2 group (see Table 3, Model 1 and Figure 2B). Notably, this association persisted even after controlling for baseline EEfRT performance. E2-STAI sensitivity strength however was not associated with performance on the EEfRT task at the post-randomization visit for participants in the placebo condition (see Table 3, Model 2 and Figure 2A). Further, randomized treatment group significantly moderated the association between E2-STAI sensitivity strength and EEfRT performance in the full study sample (see Supplementary Table S3, Model 1).

Table 3.

Regression models of E2-STAI hormone sensitivity and post-randomization EEfRT among participants randomized to the transdermal estradiol and placebo conditions.

| Model | Predictors | B | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: TE2 Group | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| E2-STAI hormone sensitivity strength | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 5.07 | <.001 | |

| Baseline EEfRT | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.68 | 7.60 | <.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Model 2: Placebo Group | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| E2-STAI hormone sensitivity strength | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.62 | .538 | |

| Baseline EEfRT | 0.92 | 0.11 | 0.85 | 8.64 | <.001 | |

Note. Model 1 includes only participants who were randomized to the transdermal estradiol group; F(2,27) = 53.03, p < .001, R2 = .794. Model 2 includes only participants who were randomized to the placebo group; F(2,31) = 37.98, p < .001, R2 = .724; see Table 3, Model 2 and Figure 2A. B = Unstandardized beta. β = Standardized beta. EEfRT = proportion of trials in which participants selected the hard choice.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of Bivariate Associations between Baseline Hormone Sensitivity and Post-Randomization EEfRT for Placebo and Active TE2 Groups.

Note. A = Scatterplot of the bivariate association between E2-STAI sensitivity for participants within the placebo group (n = 34). B = Scatterplot of bivariate association between E2-STAI sensitivity for participants in the active TE2 group (n = 32)

3.2.2. E2-SHAPS Sensitivity Strength and Post-Randomization EEfRT

E2-SHAPS sensitivity was not associated with post-randomization EEfRT scores for participants who were randomized to the TE2 condition (see Table 4, Model 1) or for participants in the placebo group (see Table 4, Model 2), and no moderation effects were observed (see Supplementary Table S3, Model 2).

Table 4.

Regression models of hormone sensitivity based on SHAPS scores and post-randomization EEfRT among participants randomized to the transdermal estradiol and placebo conditions.

| Model | Predictors | B | SE | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: TE2 Group | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| E2-SHAPS hormone sensitivity strength | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.08 | .935 | |

| Baseline EEfRT | 0.84 | 0.14 | 0.78 | 5.88 | <.001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Model 2: Placebo Group | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| E2-SHAPS hormone sensitivity strength | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.07 | −0.70 | .492 | |

| Baseline EEfRT | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.85 | 8.12 | <.001 | |

Note. Model 1 includes only participants who were randomized to the transdermal estradiol group; F(2,22) = 17.45, p < .001, R2 = .613. Model 2 includes only participants who were randomized to the placebo group; F(2,25) = 33.01, p < .001, R2 = .725. B = Unstandardized beta. β = Standardized beta. EEfRT = proportion of trials in which participants selected the hard choice.

3.2.3. Moderation Analyses with Recent Stressful Life Events

The interaction between E2-STAI sensitivity strength and the number of recent stressful life events was significant for participants randomized to the TE2 group, suggesting that the association between hormone sensitivity and post-randomization EEfRT within the TE2 group is stronger for women who experienced a greater number of recent stressful life events (see Supplementary Table S4, Model 2). In follow-up exploratory analyses, we also tested this interaction utilizing only the number of severely stressful life events. Similarly, we found that the number of severe stressful life events also moderated the association between E2-STAI hormone sensitivity and post-randomization EEfRT for women who received TE2 (see Supplementary Table S5, Model 2). Similarly, the interaction between E2-STAI sensitivity strength and the subjective stress rating of recent stressful life events was also significant for participants in the TE2 group, indicating that the association between E2-STAI hormone sensitivity and post-randomization EEfRT within the TE2 group is stronger for women who rated recent stressful life events as being more stressful (see Supplementary Table S6, Model 2).

4. Discussion

The current study utilized a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design to investigate the relation between sensitivity to endogenous E2 fluctuations and reward seeking behaviors in perimenopausal women, and whether that sensitivity predicted the beneficial effects of exogenous TE2 on reward seeking behaviors. Findings demonstrate that a greater degree of concordance between fluctuating E2 levels and anxiety symptoms (i.e., greater E2-STAI sensitivity) predicted more reward seeking behaviors, but only for women who also received active TE2 treatment and not for participants in the placebo condition. In other words, TE2 treatment modified reward seeking behavior, a key behavioral output implicated in etiology perimenopausal depression, but only for participants who demonstrated greater anxiety sensitivity to endogenous E2 fluctuations at baseline. This suggests that individual differences in baseline E2-anxiety sensitivity could be an important predictor of TE2 efficacy in increasing reward motivation and reducing anhedonic behaviors.

Notably, hormone sensitivity based on the SHAPS, a measure of hedonic capacity (defined as experiencing typically enjoyable stimuli as less pleasurable), did not predict post-randomization reward seeking behaviors for participants either in the active TE2 treatment or placebo conditions, despite TE2 significantly reducing SHAPS scores relative to placebo (see Lozza-Fiacco et al., 2022 for significant main effects of TE2 on reducing anxiety and anhedonia symptoms in this sample). Although hedonic capacity and reward motivation are both key components of anhedonia, theoretical models of anhedonia and evidence from human and animal literatures suggest that these factors are distinct and may be supported by unique underlying neural circuitry (Treadway & Zald, 2013). For example, both human and pre-clinical studies demonstrate that the mesolimbic dopamine system, which is also modulated by E2, is implicated in reward motivation, but not hedonic response (Treadway & Zald, 2013). Given these distinctions, it is plausible that the hedonic capacity is not involved in the hormonal pathways by which TE2 increases reward motivation.

The current study builds upon extant literature in several meaningful ways. First, we utilized a novel approach to quantify individual differences in mood susceptibility to E2 flux (modified from Gordon et al., 2021). We extend this work by, 1) expanding our assessment of mood symptoms to include anxiety and hedonic capacity, and 2) by investigating how the relation between E2 variability and anxiety and hedonic capacity may relate to reward seeking behaviors. Notably, only one known study has previously explored the relation between E2 and reward processing in perimenopausal women. Thomas et al. (2014) found that in a small sample of perimenopausal women (n = 13), administration of estradiol and progesterone increased neural activity in brain regions associated with reward processing (i.e., the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex) during conditions of reward anticipation, and increased reward motivation (i.e., faster reward response times) relative to placebo. We expand upon this study by not only considering the impact of exogenous estradiol on reward seeking behaviors, but also testing whether individual differences in hormone sensitivity at baseline predict reward processing related outcomes within a larger sample of women (n = 66). Our findings suggest that both endogenous E2 flux and exogenous TE2 administration may be relevant to understanding the relation between E2 signaling and reward seeking behavior.

Importantly, we also found that stressful life experiences moderated the relation between E2-anxiety hormone sensitivity and reward seeking behavior measured by the EEfRT task for participants who received active TE2 treatment. Specifically, for participants in the TE2 condition, hormone sensitivity strength based on anxiety ratings more strongly predicted reward seeking behavior when participants experienced a greater number of recent stressful life events. A similar effect was observed for subjective ratings of perceived stress of these life events. This suggests that both exposure to stressful life events as well as subjective evaluations of their psychological impact are key predictors of the beneficial effects of TE2 on reward processing. Additionally, we found a similar moderation effect when we only looked at the number of severe SLEs, suggesting that the experience of potentially traumatic events also amplifies the association between hormone sensitivity and reward seeking. Results directly align with past work demonstrating that recent stressful life events moderate the association between E2 (i.e., E2 variability and TE2) and perimenopausal depression (Gordon et al., 20016; Gordon et al., 2018). For example, Gordon and colleagues (2018) similarly report that TE2 is more efficacious in decreasing depression symptoms in perimenopausal women when women experienced a greater number of recent stressful life events. The relation between stress and E2 is further underscored by evidence from human and preclinical literatures which demonstrates that recent stressful life events dampen reward motivation via dopaminergic mesolimbic pathways, which are associated with reward processing and are also implicated in E2 signaling (Diekhof, 2018; Ironside et al., 2018; Treadway & Zald, 2011; Nusslock & Alloy, 2017). It is therefore possible that the potential beneficial effects of TE2 on the neural circuitry of reward motivation are amplified within the context of stress, because women who experienced more recent life stressors are more likely to exhibit disrupted neural responses to reward at baseline. Current study findings also extend prior work by showing that women who both experienced recent stressful life events and are also highly sensitivity to hormone fluctuations, may experience the greatest benefit from TE2 administration. Collectively, results of the current investigation thus underscore the importance of considering the role of recent stressors in potentiating the impact TE2 in perimenopausal women.

4.1. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

The current study has several key strengths. As previously stated, we investigated individual differences in E2 hormone sensitivity and TE2 using a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Additionally, we utilized the EEfRT task, a precise behavioral indicator of reward seeking (Treadway et al., 2009), to test the effects E2 flux and TE2 on willingness to expend effort in pursuit of reward. A robust literature has utilized this paradigm to map out the neural pathways underlying reward-based decision making. Specifically, the EEfRT task has been used to document the key role of dopaminergic signaling in the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in dampening or amplifying reward motivated behaviors (Treadway et al., 2012). Findings of this study could therefore inform future work seeking to further elucidate the neurobiological mechanisms underlying TE2 efficacy, suggesting that the effort-based decision making and related neural pathways supporting these behaviors may be particularly sensitive to E2 signaling during the menopause transition. Another key strength of the study design is the frequency of assessment timepoints. Both E2 levels and mood symptoms were measured on a weekly basis, allowing for a more precise measurement of E2 fluctuations than has been done in most prior perimenopausal research (Bromberger et al., 2011; Freeman et al., 2006). Lastly, the current study quantified hormone sensitivity using measures of anxiety and hedonic capacity. This is a key strength as most prior studies have focused on the occurrence of depressive episodes or have measured global changes in depression symptoms in perimenopausal women.

Despite these strengths, there are also several limitations of the current study and identified areas for future research. First, the study was stopped prematurely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Power analyses were completed prior to study termination to ensure that the current study sample size was adequately powered to detect small-to-medium effects of anxiety and anhedonia and medium-to-large effects of treatment condition. Even with this smaller sample size, it is notable that significant effects of E2-STAI sensitivity and SLEs emerged, consistent with our a-priori hypotheses and findings of the extant literature. However, given unanticipated reductions in power, results and particularly null findings and exploratory moderation analyses should be interpreted with caution and future studies should replicate results in larger samples that correct for multiple comparisons. Another limitation is that we did not include a global measure of depression symptoms in our study design. Future work may assess depression, anxiety, and anhedonia symptoms simultaneously to facilitate more direct comparisons with results of the extant literature, which focuses primarily on perimenopausal depression. Because participants were recruited from a community sample, another important next step in future research is to test whether study findings extend to women experiencing clinically elevated depression during the menopause transition. Future studies should also continue to probe other potential moderators of EEfRT outcomes, including fatigue and difficulty concentrating, as well as other predictors of task performance (e.g., probability of reward receipt, magnitude of reward). Additionally, future research should also build upon study findings by integrating neural measures of reward processing into study designs to explore the neural underpinnings of observed behavioral effects. Finally, more work is needed to investigate the mechanisms by which sensitivity to E2 flux predicts the beneficial effects of TE2 on patient outcomes. Findings from post-hoc analyses reported in Lozza-Fiacco et al. (2023) suggest that somatic symptoms may be one plausible pathway by which TE2 improves anxiety outcomes for hormone sensitive women. Specifically, we found that TE2 reduced both anxiety and somatic symptoms among women with high baseline E2-anxiety sensitivity, but not for women with low baseline E2-anxiety sensitivity (Lozza-Fiacco et al., 2023). Notably, somatic symptoms, such as dizziness, body aches, and tingling in extremities, also correlate with high anxiety states in perimenopausal women (Terauchi et al., 2013). It is therefore possible that somatic symptoms may play a role in explaining the anxiolytic effects of TE2. These and other plausible mechanisms should continue to be investigated in future research.

5. Conclusions

These findings have important implications for understanding the etiology of perimenopausal mood disorders. Better understanding the hormonal mechanisms of symptom emergence in the menopause transition may lead to early identification of hormone sensitive women who may experience the greatest benefit from treatments such as TE2. Increasing reward seeking behaviors is of particular interest as reward motivation is closely related to behavioral activation and predicts reductions in depression severity and functional impairment (Cuijpers et al., 2007; Nagy et al., 2020). Although robust replication studies are needed, the current study provides evidence that the degree of anxiety related hormone sensitivity and experience of stressful life events predict the efficacy of TE2 treatment in modifying specific behaviors implicated in the etiology of perimenopausal depression. The identification of such baseline factors that predict TE2 treatment efficacy and could therefore facilitate the delivery of precision medicine.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Hormones fluctuate dramatically during the menopause transition (perimenopause).

Concordance between weekly E2 changes and mood symptoms were computed at baseline.

This degree of concordance (sensitivity) was calculated for anxiety and anhedonia.

E2-anxiety sensitivity predicted the beneficial effects of TE2 on reward seeking.

Exposure to recent stressful life events further augmented this association.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the women who participated in this project. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01 MH108690; PI: Girdler). Author D. A. S. is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH T32 MH093315) as is author J. A. C. (NIMH K01 MH126308).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

In the past 3 years, MTT has served as a paid consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim and Blackthorn Therapeutics. MTT is a co-inventor of the EEfRT, which was used in this study. Emory University and Vanderbilt University licensed this software to BlackThorn Therapeutics. Under the IP Policies of both universities, Dr. Treadway receives licensing fees and royalties from BlackThorn Therapeutics. Additionally, Dr. Treadway has previously been a paid consulting relationship with BlackThorn. The terms of these arrangements have been reviewed and approved by Emory University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. No funding from these entities was used to support the current work, and all views expressed are solely those of the authors. The authors declare that they have no known additional competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Andersen E, Fiacco S, Gordon J, Kozik R, Baresich K, Rubinow D, & Girdler S (2022). Methods for characterizing ovarian and adrenal hormone variability and mood relationships in peripubertal females. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 141, 105747. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, & Robinson TE (2003). Parsing reward. Trends in Neurosciences, 26(9), 507–513. 10.1016/s0166-2236(03)00233-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang YF, Cyranowski JM, Brown C, & Matthews KA (2011). Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1879–1888. 10.1017/s003329171100016x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang Y, Randolph JF Jr, Avis NE, Gold EB, & Matthews KA (2013). Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Menopause, 20(5), 488–495. 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182730599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger HG, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Groome N, Guthrie JR, Green A, & Dennerstein L (1999). Prospectively measured levels of serum follicle-stimulating hormone, estradiol, and the dimeric inhibins during the menopausal transition in a population-based cohort of women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 84(11), 4025–4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger HG, Dudley EC, Robertson DM, & Dennerstein L (2002). Hormonal changes in the menopause transition. Recent Progress in Hormone Research, 57, 257–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, & Warmerdam L (2007). Behavioral activation treatments of depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(3), 318–326. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekhof EK (2018). Estradiol and the reward system in humans. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 23, 58–64. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.03.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lozza-Fiacco S, Gordon JL, Andersen EH, Kozik RG, Neely O, Schiller C, … & Girdler SS (2022). Baseline anxiety-sensitivity to estradiol fluctuations predicts anxiety symptom response to transdermal estradiol treatment in perimenopausal women-A randomized clinical trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 105851. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken IH, Rassin E, & Muris P (2007). The assessment of anhedonia in clinical and non-clinical populations: Further validation of the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 99(1-3), 83–89. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, & Nelson DB (2006). Associations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(4), 375–382. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR, Pien GW, Nelson DB, & Sheng L (2007). Symptoms associated with menopausal transition and reproductive hormones in midlife women. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 110(2), 230–240. 10.1097/01.aog.0000270153.59102.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallicchio L, Schilling C, Miller SR, Zacur H, & Flaws JA (2007). Correlates of depressive symptoms among women undergoing the menopausal transition. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63(3), 263–268. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs Z, Lee S, & Kulkarni J (2013). Factors associated with depression during the perimenopausal transition. Women’s Health Issues, 23(5), e301–e307. 10.1016/j.whi.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer G, Zeller R, Delumba L, Kalinyak C, Hobfoll S, Winchell J, & Hartman P (2002). The Ohio midlife women’s study. Health Care for Women International, 23(6-7), 612–630. 10.1080/07399330290107377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, & Girdler SS (2014). Hormone replacement therapy in the treatment of perimenopausal depression. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16(12), 1–7. 10.1007/s11920-014-0517-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, Girdler SS, Meltzer-Brody SE, Stika CS, Thurston RC, Clark CT, … & Wisner KL (2015). Ovarian hormone fluctuation, neurosteroids, and HPA axis dysregulation in perimenopausal depression: a novel heuristic model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(3), 227–236. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Leserman J, & Girdler SS (2016). Estradiol variability, stressful life events and the emergence of depressive symptomatology during the Menopause Transition. Menopause, 23(3), 257–266. 10.1097/gme.0000000000000528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Xia K, Schmidt PJ, & Girdler SS (2018). Efficacy of transdermal estradiol and micronized progesterone in the prevention of depressive symptoms in the menopause transition: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(2), 149–157. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JL, Sander B, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, & Tottenham LS (2021). Mood sensitivity to estradiol predicts depressive symptoms in the menopause transition. Psychological Medicine, 51(10), 1733–1741. 10.1017/s0033291720000483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JG (2008). Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas, 61, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo L (2016). A possible role of anhedonia as common substrate for depression and anxiety. Depression Research and Treatment. 1–8. 10.1155/2016/1598130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grub J, Süss H, Willi J, & Ehlert U (2021). Steroid hormone secretion over the course of the perimenopause: Findings from the Swiss Perimenopause Study. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 2. 10.3389/fgwh.2021.774308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironside M, Kumar P, Kang MS, & Pizzagalli DA (2018). Brain mechanisms mediating effects of stress on reward sensitivity. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 22, 106–113. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Petitto JM, Gu H, Gaynes BN, Barroso J, Golden RN, … & Evans DL (2002). Progression to AIDS, a clinical AIDS condition and mortality: Psychosocial and physiological predictors. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 1059–1073. 10.1017/s0033291702005949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Petitto JM, Perkins DO, Folds JD, Golden RN, & Evans DL (1997). Severe stress, depressive symptoms, and changes in lymphocyte subsets in human immunodeficiency virus—infected men: A 2-year follow-up study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(3), 279–285. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830150105015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, & Posner JG (1992). The normal menopause transition. Maturitas, 14(2), 103–115. 10.1016/0378-5122(92)90003-m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf MG, Donald RA, & Livesey JH (1982). Pituitary-ovarian function before, during and after the menopause: a longitudinal study. Clinical Endocrinology, 17(5), 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf MG (1983). Incidence of ovulation from the menarche to the menopause: observations of 622 New Zealand women. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 96(738), 645–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall S, Andel R, & Anstey KJ (2018). Variation in symptoms of depression and anxiety in midlife women by menopausal status. Maturitas, 108, 7–12. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy GA, Cemasov P, Pisoni A, Walsh E, Dichter GS, & Smoski MJ (2020). Reward network modulation as a mechanism of change in behavioral activation. Behavior Modification, 44(2), 186–213. 10.1177/0145445518805682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, & Alloy LB (2017). Reward processing and mood-related symptoms: An RDoC and translational neuroscience perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders, 216, 3–16. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow DR, Johnson SL, Schmidt PJ, Girdler S, & Gaynes B (2015). Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: So much promise and so few answers. Depression and Anxiety, 32(8), 539–549. 10.1002/da.22391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Johnson JH, & Siegel JM (1978). Assessing the impact of life changes: Development of the Life Experiences Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46(5), 932–946. 10.1037/0022-006x.46.5.932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PJ, Dor RB, Martinez PE, Guerrieri GM, Harsh VL, Thompson K, … & Rubinow DR (2015). Effects of estradiol withdrawal on mood in women with past perimenopausal depression: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(7), 714–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley S, Humayan A, Hargreaves D, & Trigwell P (1995). A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 99–103. 10.1192/bjp.167.1.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychogyists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss JR (2011). The reciprocal relationship between menopausal symptoms and depressive symptoms: A 9-year longitudinal study of American women in midlife. Maturitas, 70(3), 302–306. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terauchi M, Hiramitsu S, Akiyoshi M, Owa Y, Kato K, Obayashi S, … & Kubota T (2013). Associations among depression, anxiety and somatic symptoms in peri-and postmenopausal women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 39(5), 1007–1013. 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.02064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Météreau E, Déchaud H, Pugeat M, & Dreher JC (2014). Hormonal treatment increases the response of the reward system at the menopause transition: A counterbalanced randomized placebo-controlled fMRI study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 167–180. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Cowan RL, Woodward ND, Li R, Ansari MS, … & Zald DH (2012). Dopaminergic mechanisms of individual differences in human effort-based decision-making. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(18), 6170–6176. 10.1523/jneurosci.6459-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Schwartzman AN, Lambert WE, & Zald DH (2009). Worth the ‘EEfRT’? The effort expenditure for rewards task as an objective measure of motivation and anhedonia. PloS One, 4(8), e6598. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, & Zald DH (2011). Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: lessons from translational neuroscience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(3), 537–555. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadway MT, & Zald DH (2013). Parsing anhedonia: Translational models of reward-processing deficits in psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 244–249. 10.1177/0963721412474460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.