Abstract

Background and Aims:

Chimeric antigen receptor engineered T cells (CARTs) for HCC and other solid tumors are not as effective as they are for blood cancers. CARTs may lose function inside tumors due to persistent antigen engagement. The aims of this study are to develop low-affinity monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and low-avidity CARTs for HCC and to test the hypothesis that low-avidity CARTs can resist exhaustion and maintain functions in solid tumors, generating durable antitumor effects.

Methods and Results:

New human glypican-3 (hGPC3) mAbs were developed from immunized mice. We obtained three hGPC3-specific mAbs that stained HCC tumors, but not the adjacent normal liver tissues. One of them, 8F8, bound an epitope close to that of GC33, the frequently used high-affinity mAb, but with approximately 17-fold lower affinity. We then compared the 8F8 CARTs to GC33 CARTs for their in vitro function and in vivo antitumor effects. In vitro, low-avidity 8F8 CARTs killed both hGPC3high and hGPC3low HCC tumor cells to the same extent as high-avidity GC33 CARTs. 8F8 CARTs expanded and persisted to a greater extent than GC33 CARTs, resulting in durable responses against HCC xenografts. Importantly, compared with GC33 CARTs, there were 5-fold more of 8F8-BBz CARTs in the tumor mass for a longer period of time. Remarkably, the tumor-infiltrating 8F8 CARTs were less exhausted and apoptotic, and more functional than GC33 CARTs.

Conclusion:

The low-avidity 8F8-BBz CART resists exhaustion and apoptosis inside tumor lesions, demonstrating a greater therapeutic potential than high-avidity CARTs.

INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer, most being HCC, is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death in the world,[1] underscoring the need to develop novel therapies. Immunotherapy has become a mainstream treatment, which relies on the antigen-specific T cells that, unfortunately, do not always exist in solid tumors.[2] Redirecting patient’s T cells with T-cell receptors[3] or chimeric antigen receptors (CARs)[4] can provide tumor-specific T cells. The success of CAR-modified T cells (CARTs) in blood cancers has sparked tremendous effort to develop CARTs for solid tumors.[5] Different from blood cancer, solid tumor mass creates a barrier to T-cell infiltration and a suppressive tumor microenvironment. In addition, after T cells manage to infiltrate into tumors, they submerge into a tumor antigen swamp that constantly stimulate and drive them into exhaustion and death.[6,7] Approaches have been studied to reduce CART exhaustion, such as modification of the spacer,[8] use of 4-1BB domain,[9] and combination with checkpoint blockade.[10] However, despite intensive effort, CART therapy has not yet proved effective for solid tumors.[11,12]

The affinity (strength between a single pair of molecules) of the antigen-binding domain can affect CART’s avidity (strength of multiple pairs of molecules) and the ensuing T-cell activation and antitumor effects.[5,13] Conventionally, high-affinity antigen-binding domains are preferred because they induce strong activation and can detect low levels of antigens.[14-16] For example, the FMC63 monoclonal antibody (mAb) in CD19 CAR is high-affinity (KD = 0.32 nm).[17] The CARs[18-20] targeting human glypican-3 (hGPC3) of HCC[21] are also from high-affinity mAbs (ie, GC33 [EC50 = 0.24 nm],[22] YP7 [EC50 = 0.3 nm],[23] and 32A9 [EC50 = 1.24 nm]).[20] A phase 1 trial of GC33 CART generated weak antitumor efficacy at best.[24] While the high-avidity CARTs may generate strong engagement and tumor killing effect, they may be prone to activation-induced exhaustion and death, especially in the presence of persistent antigens of solid tumors. For example, high level of anti-GD2 CAR resulted in exhaustion and depletion of CARTs after in vitro stimulation.[25] Recently, studies suggest that low-avidity CARs are beneficial. (1) Low-avidity CART could distinguish antigenhigh tumor from antigenlow normal cells to avoid off-tumor toxicity.[26] (2) Low-avidity lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) CART resisted to activation-induced death and generated better effects with reduced toxicity.[27] (3) Lowering GD2 CAR expression and avidity could better retain CART’s killing activity.[25] (4) Low-avidity CD19 CART had more expansion and longer persistence in blood cancers.[17] (5) Low-affinity antigen-binding domain may enable the control of CAR avidity via dimerization by small molecules to adjust T-cell activation.[28] However, it remains unknown whether low-avidity CARTs can persist and maintain better effector function inside solid tumors, and thus generate durable effects.

In this study, we developed low-avidity hGPC3 CARTs and studied their antitumor effects against HCC xenografts. We developed three hGPC3 mAbs (6G11, 8F8, and 12D7) with distinct epitopes and affinity. 8F8 mAb binds to an epitope close to that of GC33, but has 17-times lower affinity. The low-avidity engagement of 8F8 CARTs is sufficient to kill both hGPC3high HepG2 and hGPC3low Huh7 and Hep3B tumor cells to the same extent as GC33 CART. Importantly, 8F8 CART generated enhanced in vivo expansion, persistence, and durable antitumor effects. Analysis of CARTs in tumor mass showed that the 8F8-BBz CART had 5 times more infiltration, was less apoptotic and exhausted, and maintained better function for a longer period of time. In vitro co-culture with tumor cells also showed that 8F8 CARTs were less apoptotic and exhausted while containing more central memory T cells than GC33 CARTs. In conclusion, the low-avidity hGPC3 8F8 CARTs resist exhaustion and maintain function in tumor lesions, and thus will likely generate potent therapeutic effects in treating HCC and other GPC3+ solid tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

Human T cells were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by negative isolation (Stemcell Technologies). Jurkat, HEK293T, HepG2, and Hep3B cells were from ATCC (Manassas). Huh7 were from Dr. Ande, Augusta University. HepG2 cells expressing luciferase (HepG2-Luc), Hep3B-Luc, and HepG2-GFP cells were developed in lab. Cells with no more than 10 passages were used in the study to assure authenticity.

Mice and tumor models

Animal protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. BalB/C and NSG mice were from the Jackson Laboratory. Subcutaneous (SC) and intraperitoneal (IP) tumors were established. Tumor size was measured by caliber, and the volume was calculated by the following formula: ½(LxWxH). HepG2-Luc and Hep3B-Luc tumors were measured by bioluminescent intensity (BLI).

hGPC3-specific mAbs

hGPC3-specific mAbs were generated by immunizing BALB/c mice with hGPC3 protein (AA25-560) (Creative Biomart). Splenocytes were fused with Sp2/0 myeloma cells to create hybridomas, which were screened by ELISA.

Immune fluorescent staining

Immune fluorescent staining was performed to study mAbs binding of HCC cells. The fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti-mouse Igκ chain antibody (BioLegend) was used as secondary antibody.

Immunohistochemical staining

The specificity of mAbs were further characterized by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

mAb’s complementary DNA sequences

The technique of 5′ rapid amplification of complementary DNA (cDNA) ends (5’ RACE)[3] to identify the cDNA sequences of mAb.

Recombinant antibodies

Recombinant mAbs were created by fusing their VH (variable region of heavy chain) or VL (light chain variable region) with constant region of human Igγ1 or Igκ.[29] The L and H chain genes were co-transfected into 293 cells. The mAbs were purified by Protein-G column.

Epitope and affinity of mAbs

The epitopes recognized by mAbs were mapped with overlapping peptides. The affinities of recombinant mAbs to hGPC3 were determined using Biolayer interferometry.[30]

CARTs

The second-generation CARs consist of the CD8 leader, VL, glycine and serine linker, VH, hinge, transmembrane domain of CD28, and 4-1BB and CD3ζ signaling domains. In some cases, mCherry is fused to C-terminal of CD3ζ to tag CAR. The entire gene was behind elongation factor 1α (EF1α) promoter. Lentivector production was done as described.[31] Isolated T cells were activated by CD3/CD28 beads (Fisher Scientific) at 1:1 ratio and transduced by lentivectors at 20 multiplicity of infection.[3] The CAR was detected by anti-mouse Fab antibody (Jackson ImmunoReseach Lab) or by mCherry.

Adoptive cell transfer

Ten days after transduction, CARTs were transferred into tumor-bearing NSG mice.

Monitoring of CARTs in the blood

The CARTs in mouse blood were monitored by staining the hCD45 and mCherry. hCD45 staining was used because it has better separation than CD3. hCD45+ represents human T cells. mCD45 staining was used as a reference for comparison.

Cytotoxicity assay

The in vitro cytotoxicity was analyzed by lactate dehydrogenase assay according to manufacturer (Promega) or by using IncuCyte S1 real-time cell analyzer (Sartorius).

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Single-cell suspension of tumor lesion was prepared.[32] The number of CARTs in tumor lesions and their exhaustion and apoptosis were analyzed by immunological staining.

Bulk RNA sequencing

CARTs were sorted from tumor lesions and total RNA was isolated. The bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was done by Novogene.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done as described in figure legends.

RESULTS

hGPC3-specific mAbs are developed and characterized

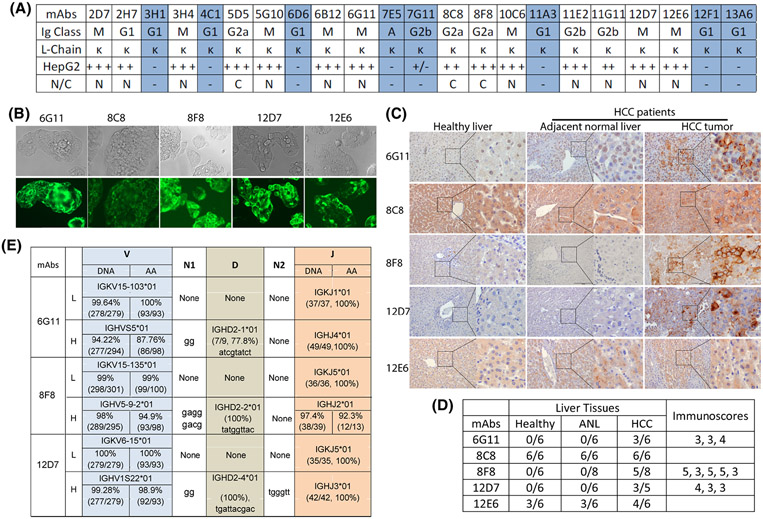

First, we developed hGPC3 mAbs that could specifically stain HCC tumor cells and tissues. Hybridomas were generated from the hGPC3-immunized mice. After screening by ELISA, 22 mAbs were found to bind hGPC3 protein (Figure 1A). Among them, 14 mAbs-stained HepG2 cells (Figure 1B and Figure S1), and 7 of the 14 mAbs also stained hGPC3lo Huh7 cells, albeit with lower intensity (Figure S2). Because hGPC3 might be naturally cleaved into hGPC3-N (AA1-358) and hGPC3-C (AA359-580) fragments, we examined the new mAbs bound to which fragment. To this end, the 293T cells transfected with hGPC3-N or hGPC3-C plasmid (Figure S3A) were intracellularly stained with the new mAbs. The data show that, of the 14 mAbs that stained HepG2 cells, 11 bound to the hGPC3-N and 3 bound to the hGPC3-C (Figure S3B).

FIGURE 1.

Generation and characterization of human glypican-3 (hGPC3)–specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). (A) Summary of the 22 new hGPC3 mAbs. The Ig class, staining of HepG2 cells, and binding of hGPC3 N-fragment or C-fragment were identified. The mAbs in blue shade did not stain HepG2 cells. (B) Representative images of immunofluorescence (IF) staining of HepG2 cells. The fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled anti-mouse Igκ chain was used as the secondary antibody. (C) Representative images of immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of HCC and paired adjacent normal liver tissues (ANL), and the healthy donor liver tissue. Secondary antibody was the biotinylated anti-mouse IgM or anti-mouse IgG. Detection was done by VECTASTAIN ABC (horseradish peroxidase [HRP]) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate. (D) Summary of IHC staining of multiple tissue samples by five mAbs. The immunoscores (8, highest; 0, lowest) were determined as described in the Supporting Materials and Methods, and each number indicated one positive staining. (E) The V, D, and J genes of the 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7 complementary DNA (cDNA) were presented. Nucleotides added between V and D (N1) or D and J (N2) in the VH were also shown. The percentage and number in the parentheses indicate the percent identity and the length of nucleotides of indicated genes

To further characterize the specificity, we purified five mAbs (6G11, 8C8, 8F8, 12D7, and 12E6) and conducted IHC staining of HCC and paired adjacent normal tissues. Healthy livers were also included as control. We found that three mAbs (6G11, 8F8, and 12D7) specifically stained the HCC tissues but not the adjacent normal and healthy liver tissues (Figure 1C,D and Figure S4). However, the other two mAbs had high nonspecific staining of normal liver tissues. Thus, only 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7 were used in further studies. The cDNA of the VH and the VL of 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7 were sequenced and compared with the Ig in the ImMunoGeneTics databank.[33] The results were summarized in Figure 1E.

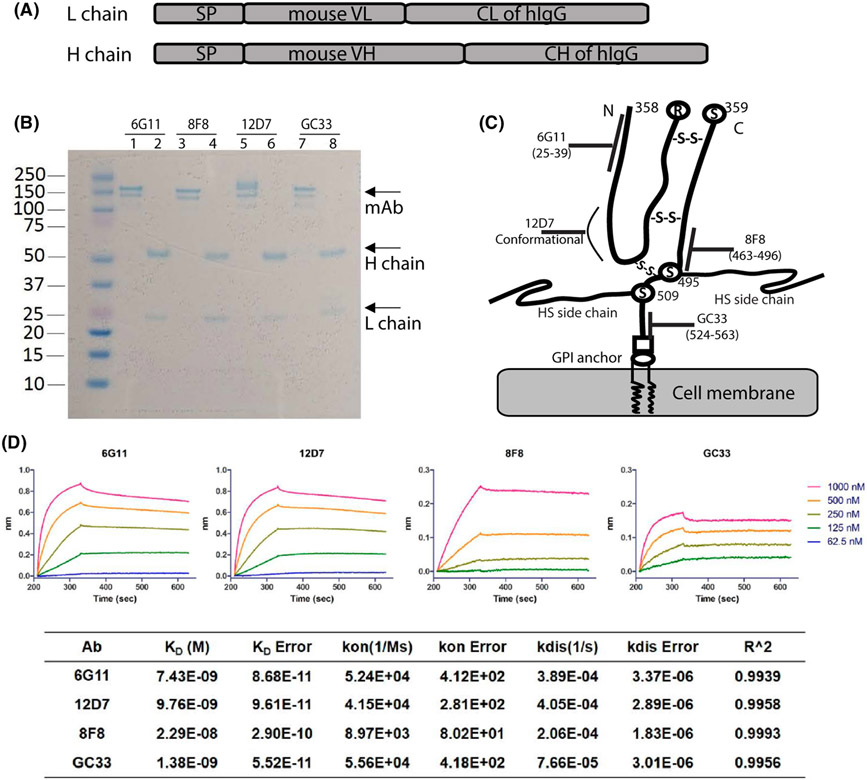

6G11, 8F8, and 12D7 mAbs bind to distinct hGPC3 epitopes with different affinities

To search for low-affinity mAbs, we determined the binding affinity and epitopes of 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7, and compared them with GC33, a commonly used mAb in CAR design.[34] As the four mAbs belong to different Ig classes (6G11 and 12D7 are IgM; 8F8 is IgG2a; GC33 is IgG1), recombinant mAbs using VL and VH and a same human IgG H and L constant region were generated for fair comparison (Figure 2A). The recombinant mAbs were produced and purified from 293 cells (Figure 2B). The epitopes were mapped by western blot and ELISA with overlapping peptides (Figure S5). The data showed that 6G11 and 8F8 bound to AA25-39 and AA463-496, respectively. The epitope of 8F8 is next to that of GC33 (30AA apart). No specific epitope was mapped for 12D7, although it bound to hGPC3-N fragment. 12D7 may recognize a conformational epitope. The epitopes recognized by the mAbs were illustrated on the hGPC3 protein diagram (Figure 2C).[35] Next, we determined the affinity of mAbs using BioLayer Interferometry. The KD of mAbs binding to hGPC3 were measured as 7.4 nm for 6G11, 9.8 nm for 12D7, 22.9 nm for 8F8, and 1.38 nm for GC33 (Figure 2D). The value of the KD of 8F8 is approximately 17 times higher than that of GC33. The kon (association rate constant) of 8F8 and GC33 mAb binding hGPC3 are 8.97 × 103/M−1S−1 and 5.56 × 104/M−1S−1, respectively, indicating that 8F8 mAb binds to hGPC3 is 6.2 times slower than GC33 mAb. The kdis (dissociation rate constant or koff) of 8F8 and GC33 are 2.06 × 10−4/S−1 and 7.66 × 10−5/S−1, respectively, suggesting that 8F8-hGPC3 complex dissociate 2.7 times faster than GC33-hGPC3. Overall, compared with GC33, 8F8 mAb has a slow and unstable (Slow-on and Fast-off) engagement with hGPC3.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of the binding epitopes and affinity of 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7 recombinant mAbs. (A) The schematic structure of the recombinant mAbs. (B) PAGE analysis of the purified recombinant mAbs under nonreduced (line 1, 3, 5, 7) and reduced (2, 4, 6, 8) condition. mAbs were purified from the 293T cells after co-transfection of the L and H expressing plasmids. Gel was stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain. (C) The binding epitopes of mAbs are illustrated on a schematic structure of hGPC3 derived from Haruyama and Kataoka (ref 37). GC33 mAb’s epitope was also indicated. The disulfide bonds between N-fragment and C-fragment of hGPC3 are shown. (D) The KD, Kon, and Koff value of each mAbs were determined by Biolayer interferometry. The data from one representative experiment is shown. The error refers to the deviation between the fitting curve and the test curve. The measurement was repeated 3 times with similar data. CH, constant region of human IgG heavy chain; CL, constant region of human IgG light chain; SP, signal peptide of human IgG; VH, variable region of heavy chain; VL, variable region of light chain

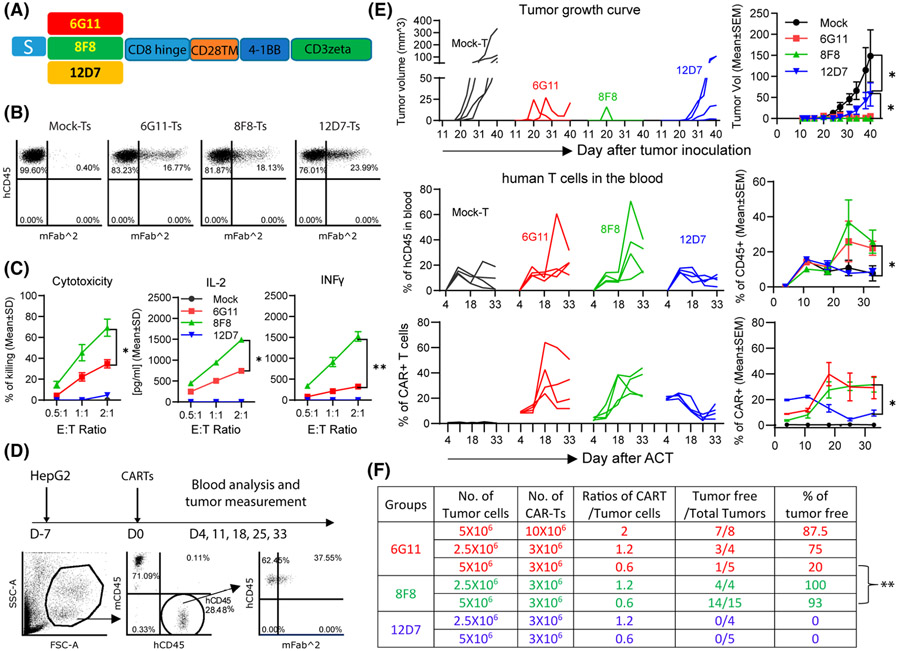

8F8 CART generates stronger antitumor effects than 6G11 and 12D7 CARTs

We hypothesized that 8F8 CART would generate stronger effects than 6G11 and 12D7 based on previous reports that CARTs targeting membrane-proximal epitopes were more effective.[36,37] We built CARs using the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) of 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7 and 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain (Figure 3A). Human T cells were isolated from the human blood buffy coat (Figure S6) and transduced by lentivectors to generate CARTs for in vitro and in vivo studies. The CARTs were detected by anti-Fab antibody (Figure 3B). All three CARTs could be expanded by HepG2 cells (Figure S7A). However, only 6G11 and 8F8 CARTs killed HepG2 cells and produced interferon-γ (IFNγ) and IL-2 (Figure 3C). 6G11 and 8F8 CARTs were also able to kill hGPC3lo Huh7 tumor cells (Figure S7B). 12D7 CART had no detectable cytotoxicity and cytokines. Second, compared with 6G11, 8F8 CART had stronger killing activity and produced more IL-2 and IFNγ (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

8F8 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)–modified T cells (CARTs) generate the strongest antitumor effects among three new CARTs. (A) Schematic structure of the second generation CARs built from 6G11, 8F8, and 12D7. Human T cells were isolated from donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and activated by CD3/CD28 beads on D-1. T cells were transduced on D0, and beads were depleted on D1. CAR was detected on D7 by anti-Fab, and the in vitro function was assayed between D7 and D10. (B) Representative dot plots of CARTs. (C) Cytotoxicity and cytokine production of CARTs against HepG2 cells. Statistics were performed with two-way ANOVA. Experiment was repeated 3 times with similar observations. (D) In vivo experiment plan and gating strategy of analyzing CARTs in the blood. Mouse endogenous mCD45 was stained as internal reference. (E) Tumor growth curve, the percentage of hCD45+, and percentage of CARTs after adoptive cell transfer (ACT). Four mice were in each group. No human T cells were detected in blood on Day 4; thus, the percentage of CAR+ before ACT was used. The kinetic curve of individual mouse and a summary of each group are presented. Statistics were performed with two-way ANOVA. (F) Summary of the antitumor data from three experiments of treating HCC xenografts with different doses of CARTs. The numbers of tumor cells and CARTs were the initial numbers when they were injected into mice. The statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. IFNγ, interferon-γ; S, CD8 signal peptide

To study in vivo antitumor effects, SC HCC xenografts in NSG mice were treated (Figure 3D). 6G11 and 8F8 CARTs generated potent antitumor effects (Figure 3E and Figure S8). Consistent with in vitro data, no obvious antitumor effect was found in 12D7 CART. The antitumor effects of 6G11 and 8F8 CARTs were dose-dependent (Figure 3F). Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of 1.2–2-fold of 6G11 CART (compared with the initial number of inoculated HepG2 cells) resulted in complete tumor eradication in 75%–90% of treated mice, but transfer of 0.6-fold of 6G11 CART yielded only 20% of tumor-free mice. In contrast, 8F8 CART resulted in complete eradication in more than 90% of the mice even when 0.6-fold of 8F8 CARTs was transferred. Correlating to their antitumor effects, 6G11 and 8F8 CARTs expanded in the treated mice (Figure 3D,E). In contrast, the mice treated with 12D7 CARTs showed no increase of human T cells and CARTs. In summary, our data show that 8F8 CART targeting the membrane-proximal epitope generated the most potent antitumor effects, correlating with its in vivo expansion.

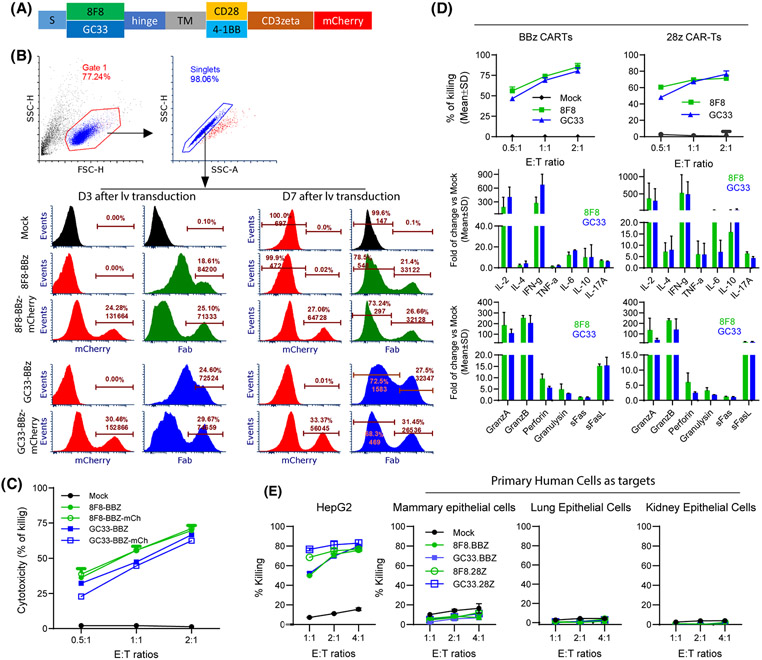

8F8 CARTs mediate similar in vitro effector functions as GC33 CARTs despite low avidity

As 8F8 and GC33 mAbs bind the epitopes close to each other, but with 17-fold different affinity, we did comparative studies between 8F8 and GC33 CARTs in the following experiments. First, we conducted an in vitro study. Because different affinity scFv may require different intracellular domain (ICD) for optimal activation,[38] we constructed the 8F8 and GC33 CARs with CD28-CD3ζ (28z) or 4-1BB-CD3ζ (BBz) (Figure 4A). As anti-Fab staining did not clearly separate CARTs (Figure 3B), we tagged CARs with mCherry to reliably detect them and compare their level and hGPC3 binding avidity. Indeed, mCherry tag could clearly identify the CARTs (Figure 4B). The mCherry also allows better anti-Fab staining to separate the CART population. Multiple donor T cells were comparably transduced, and the CARTs with mCherry tag is functional (Figure S9). Importantly, mCherry tag did not affect CART’S effector function (Figure 4C). A comparative study showed that, in both 28z and BBz ICD settings, 8F8 and GC33 CARTs had similar cytotoxicity and cytokine production (Figure 4D). The cytotoxicity was also assayed by Real-Time Cell Analyzer, and a similar result was observed (Figure S10).

FIGURE 4.

8F8 CARTs have similar in vitro function as GC33 CARTs despite low avidity. (A) Schematic illustration of CARs with mCherry tag. The hinge is from CD8, and the transmembrane domain (TM) is from CD28. (B) mCherry tag enabled clear identification of CAR+ cells. Cells were stained with anti-Fab antibody on D3 and D7 after transduction. Representative histogram of BBz CARs are shown. (C) Comparison of the cytotoxicity of CARs with and without mCherry tag. The experiment was repeated 3 times with similar observation. (D) Cytotoxicity and cytokine production of different CARTs. The fold of increase over mock T cells are presented. Data were from the combined media of triplicate wells. Two Luminex testing repeats were conducted. (E) 8F8 and GC33 CARTs do not kill normal primary human cells. Primary human cells were co-cultured with CARTs for 24 h before lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. HepG2 cells were used as positive control. FasL, Fas ligand

Next, to examine the CART’s off-tumor toxicity, we studied whether the 8F8 and GC33 CARTs could kill primary human mammary, lung, and kidney epithelial cells, as they have low level of hGPC3 RNA (http://www.proteinatlas.org). The data showed that both 8F8 and GC33 CARTs did not kill those primary human cells (Figure 4E).

Furthermore, the mCherry tag enabled us to compare CART’s antigen binding avidity. First, by mCherry intensity, we showed similar levels of 8F8 and GC33 CARs, although 28z CAR was slightly (1.3 times) higher than BBz CAR (Figure S11). Second, 8F8 CARTs with BBz or 28z ICD bound 4–5 times less hGPC3 protein than the counterpart GC33 CARTs. Third, 28z CARTs bound more than 2 times more hGPC3 than BBz CARTs, even though their CAR level was only slightly (1.3 times) higher. Our data indicate that the 8F8 CAR is indeed low-avidity compared with GC33 CAR, and that BBz CAR binds less hGPC3 than 28z CAR.

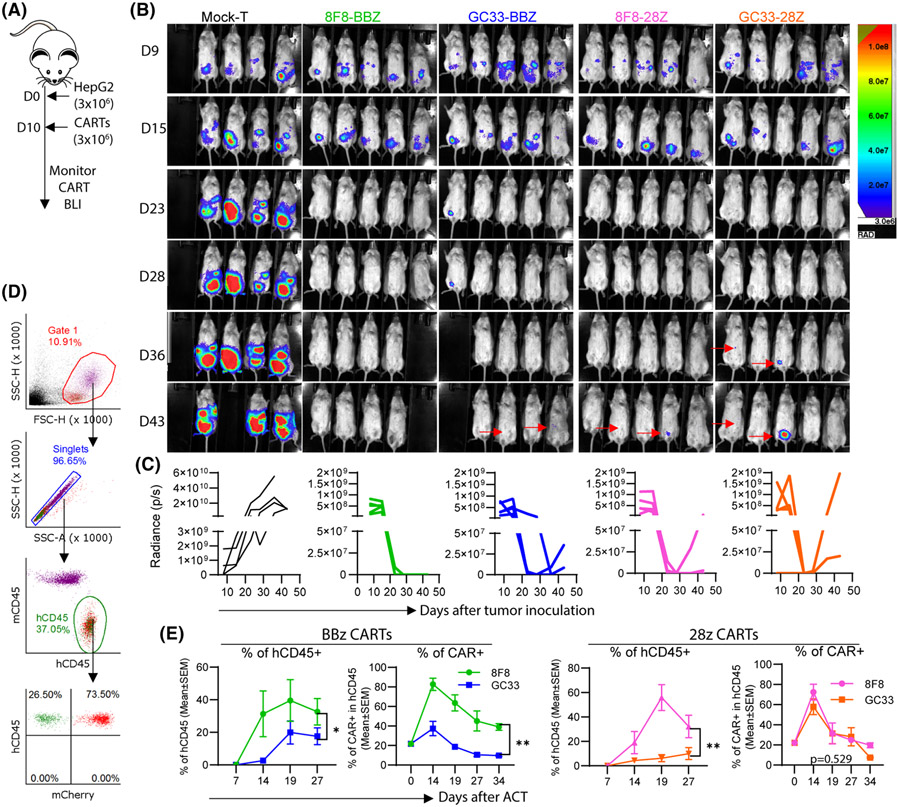

8F8-BBz CART mediates durable antitumor effect with enhanced in vivo expansion

To study whether low-avidity CART is superior to high-avidity CARTs in vivo, we used the IP HCC xenografts to study the in vivo expansion and antitumor effects of 8F8 and GC33 CARTs with BBz or 28z ICD. HepG2-Luc were generated. Three million of HepG2-Luc cells were inoculated into peritoneal cavity to establish IP tumors for 10 days before treatment (Figure 5A). Two weeks after ACT, nearly every tumor in all CART-treated groups was eliminated (Figure 5B,C). However, 40% of the mice in the GC33-28z, 8F8-28z, and GC33-BBz treated groups showed tumor regrowth 4–5 weeks after ACT. In contrast, no tumor regrowth was observed in the 8F8-BBz group. Importantly, significantly more human T cells and CARTs were found in the 8F8 CART-treated mice, especially in the 8F8-BBz CART group (Figure 5D,E).

FIGURE 5.

8F8-BBz CART generates durable antitumor effect with enhanced expansion and persistence. (A) Experimental plan. There were four (mock) or five (CART) mice in each group. (B) Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) of the intraperitoneal (IP) tumors. All images at different time points and from different groups were adjusted to the same scale. (C) Tumor BLI kinetics of each individual mouse. Different y-axis scales were used due to the high BLI of the Mock group. (D,E) Gating strategy and detection of hCD45 T cells and CARTs in the blood. Endogenous mCD45+ cells were the internal reference. Statistics were performed with two-way ANOVA

To compare the antitumor effects of 8F8 and GC33 CARTs further, we treated larger (22-day) tumors and investigated CART’s in vivo expansion (Figure S12A). Although CARTs were unable to eradicate such large tumors (Figure S12B), the survival of the mice treated with 8F8-BBz CART was significantly longer than other groups (Figure S12C). Again, the percentage of human T cells and percentage of CARTs were significantly higher and persisted longer in the 8F8-BBz CART group than the other groups (Figure S12D). These data suggest that, compared with GC33 and 8F8-28z CARTs, 8F8-BBz CART generates enhanced expansion and persistence, especially in the presence of large tumor burden, resulting in durable antitumor effects and extending survival.

Low-avidity 8F8 CARTs are able to kill hGPC3low tumor cells

One possible disadvantage of low-avidity CARTs is that they may not have sufficient engagement with antigenlow tumor cells. Thus, we studied the cytotoxicity of 8F8 CARTs on hGPC3low Hep3B and Huh7 HCC cells. As the hGPC3 level on these HCC cells was reported with great discrepancy,[19,39] we first determined their level. The data showed that hGPC3 was high on HepG2 and low on Huh7 and Hep3B (Figure S13A). In fact, Hep3B was about 2.4 times lower than HepG2 cells. However, 8F8 and GC33 CARTs killed hGPC3low Huh7 and Hep3B with similar efficacy (Figure S13B). Compared with Huh7 and Hep3B, HepG2 cells were more effectively killed by both 8F8 and GC33 CARTs at lower E/T ratio. The 8F8 and GC33 CARTs produced similar IL-2 and IFNγ in response to hGPC3hi HepG2 cells (Figure S13C,D). However, 8F8 CARTs produced less IL-2 and IFNγ than GC33 CARTs when targeting Huh7 and Hep3B cells. We conclude that low-avidity 8F8 CARTs generate sufficient engagement to kill hGPC3low tumor cells without losing efficiency, but may produce lower amount of cytokines. This is in agreement with previous report that, compared with cytokine production, a lower level of antigen density was sufficient for CARTs to kill tumor cells.[40]

We then studied whether low-avidity 8F8 CARTs could effectively control hGPC3low Hep3B tumor growth. Our data showed that both 8F8 and GC33 CARTs were effective in controlling SC (Figure S14) and IP tumors (Figure S15). In the IP tumor model, similar to HepG2 tumors (Figure 5), GC33 CART-treated mice showed obvious tumor regrowth, suggesting that the low-avidity CART may also generate durable effects even in hGPC3low tumors. In addition, compared with hGPC3high HepG2 tumors (Figure 5E and Figure S12D), the percentage of human T cells in the mice bearing Hep3B tumors is much lower in all groups after ACT (Figure S15D), possibly due to lower antigen level. Even in the hGPC3low tumor model, hCD45+ T cells were higher in the mouse treated with 8F8 CARTs (Figure S15D), further suggesting that low-avidity CARTs have survival advantages.

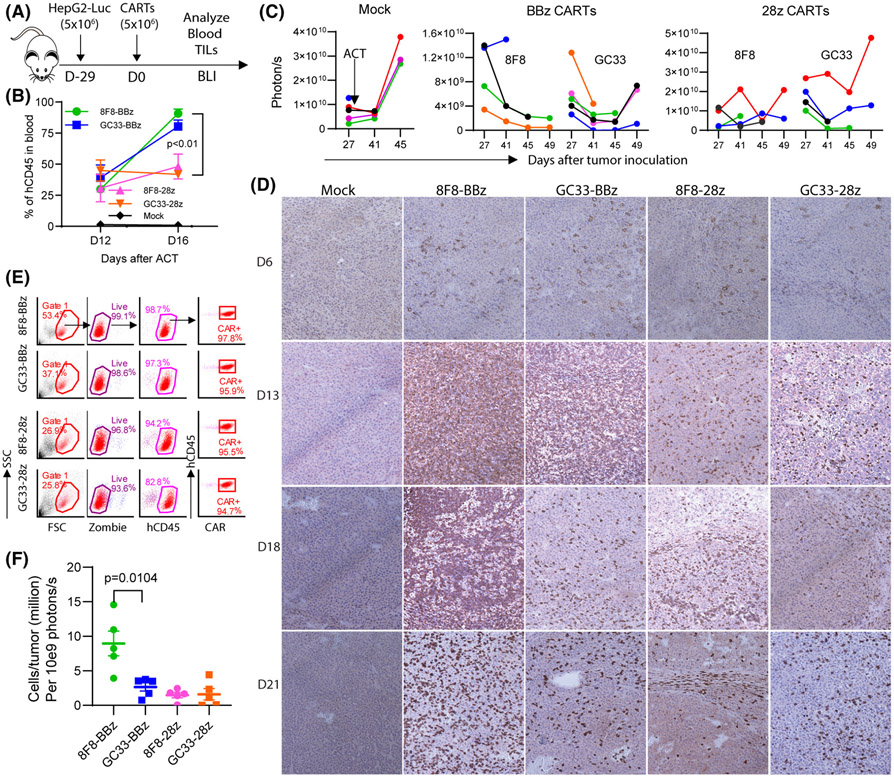

More 8F8-BBz CARTs infiltrate and persist in the tumor mass than GC33 CARTs

We next examined tumor-infiltrating CARTs to test the hypothesis that low-avidity 8F8 CART persists longer in solid tumors. To obtain sufficient tumor-infiltrating CARTs, we established large SC tumors (4 weeks, 1 cm in diameter) before ACT (Figure 6A). First, the hCD45 T cells in blood were similar (30%–50%) on Day 12 after ACT in all groups. On Day 16, the hCD45 T cells in 8F8-BBz and GC33-BBz CART groups increased three-fold (30%–90%) and two-fold (from 40% to 80%), respectively (Figure 6B). However, while the hCD45+ T cells in the 8F8-28z CART group modestly increased (30%–48%), it slightly decreased in the GC33-28z group (45%–42%). Secondly, BLI measurement showed that 8F8-BBz CART generated more durable tumor control compared with other CARTs (Figure 6C), similar to the antitumor effects observed in smaller IP tumors (Figure 5). Remarkably, there were far more tumor-infiltrating 8F8-BBz CARTs than any other CARTs, especially at later time points (Figure 6D).

FIGURE 6.

More 8F8-BBz CARTs are detected in the tumor mass than other CARTs. (A) Experimental plan. Four to five mice were in each group. (B) Change of hCD45+ T cells in the blood after ACT. (C) Tumor BLI kinetics after CART treatment. Each line represents an individual tumor. (D) Representative IHC staining of tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells at indicated time points after ACT. To cover more area, small magnification (×10) was used. The data show that more CARTs were found in the 8F8-BBz CART-treated tumors, especially at a later time point. (E) Gating strategy for enumerating the tumor-infiltrating CARTs. The viable cells from the tumor single-cell suspension were counted by Trypan blue and further determined by Zoombie staining. The CART number in the tumor was calculated by the total viable cells in the tumor times the percentage of hCD45 times the percentage of CAR+ times the volume. (F) Summary of the tumor-infiltrating CARTs from three time points (D13, D18, and D21). The number was normalized by dividing the total tumor-infiltrating CARTs by the corresponding tumor BLI. The experiment was repeated twice with similar observation

Nearly all live cells in the single-cell suspension of the BBz CART–treated tumor were CAR+ (Figure 6E). On the other hand, the single-cell suspension of the GC33-28z-treated group contained more non-hCD45 T cells (likely HepG2 tumor cells). The CART enumeration in the tumor lesion showed that there were 5 times more 8F8-BBz CARTs than any other CART groups (Figure 6F).

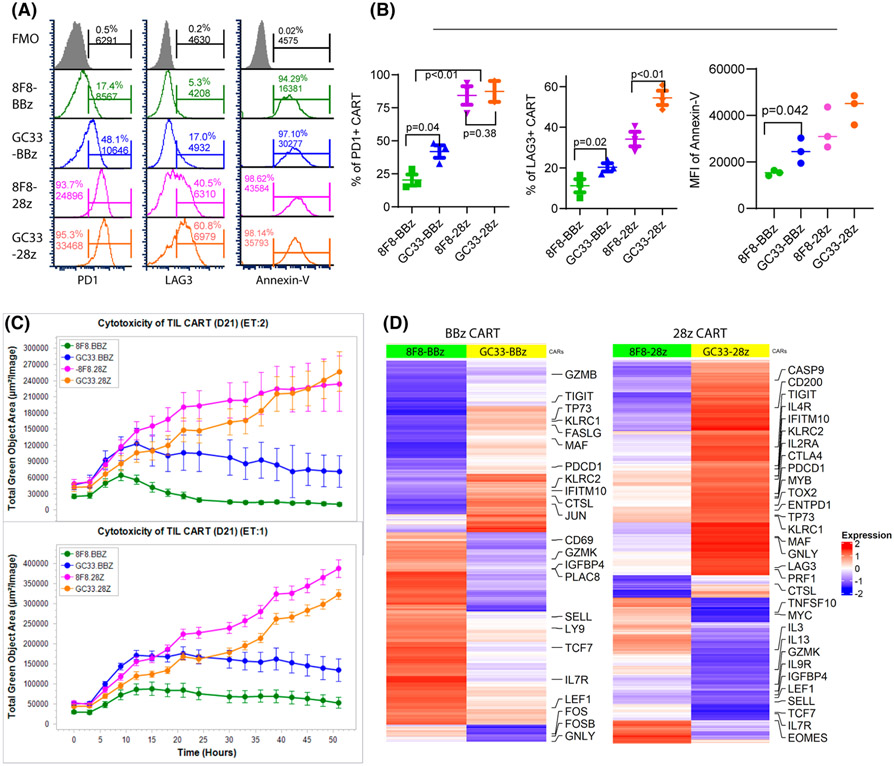

8F8-BBz CARTs resist exhaustion and maintain better function in tumors

In this experiment, we tested the hypothesis that low-avidity CARTs were more resistant to exhaustion and apoptosis, and maintained better effector function in solid tumors. To this end, we studied the exhaustion, apoptosis, and effector function of the tumor-infiltrating CARTs. The PD1, LAG3, and Annexin-V staining showed that BBz CARTs were less exhausted and apoptotic than 28z CARTs and that low-avidity 8F8 CARTs were less exhausted and apoptotic than high-avidity GC33 CARTs (Figure 7A,B and Figure S16A). The 8F8-BBz and GC33-28z CART were the least and the most exhausted and apoptotic CARTs, respectively (Figure 7B). The loss of cytotoxicity function in the tumor was CART-dependent and time-dependent (Figure 7C and Figure S16B). In agreement with their high exhaustion and apoptosis, 28z CARTs in tumor lost their killing activity faster than BBz CARTs. The low-affinity 8F8 CARTs retained effector function longer than GC33 CARTs. The tumor-infiltrating 8F8-BBz CART maintained substantial cytotoxicity at Day 21 after treatment, when other CART’s function were completely lost or severely compromised (Figure 7C). In addition, the tumor-infiltrating CARTs were sorted and their gene-expression profile was analyzed by bulk RNA-seq. The gene-expression profile was in agreement with immunological data. Differential gene expression between 8F8 and GC33 CARTs was observed (Figure 7D and Figure S16C). The genes related to T-cell exhaustion are lower in 8F8 than in GC33 CARTs. In contrast, expression of genes related to effector function, memory, and stem-like memory were higher in 8F8 CARTs than in GC33 CARTs. In conclusion, tumor-infiltrating 8F8-BBz CARTs are less exhausted and apoptotic while maintaining better effector function than 8F8-28z and high-avidity GC33 CARTs.

FIGURE 7.

8F8-BBz CARTs in tumors are less exhausted and more functional. (A) The exhaustion and apoptosis of tumor-infiltrating CARTs at D21 after ACT. The CARTs from the tumor single-cell suspensions were stained and gated as in Figure 6E and analyzed for program death receptor 1 (PD1), lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3), or Annexin-V. Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) was used to set up the gate. (B) Summary of the exhaustion and apoptosis of tumor-infiltrating CARTs. Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t test. (C) Cytotoxicity of CARTs isolated from tumors on D21 after ACT. Each data point was calculated from 10 data sets of the HepG2-GFP area from two repeating wells. The lower tumor area indicates more killing by CARTs. The experiment was repeated twice with similar observation. (D) Heatmaps show differentially expressed genes between 8F8 and GC33 CART cells. Genes coordinately up-regulated or down-regulated at least 1.2-fold between 8F8 and GC33 CART cells are plotted in the heatmaps. Labels highlight genes involved in memory and effector differentiation or exhaustion, and apoptosis pathways

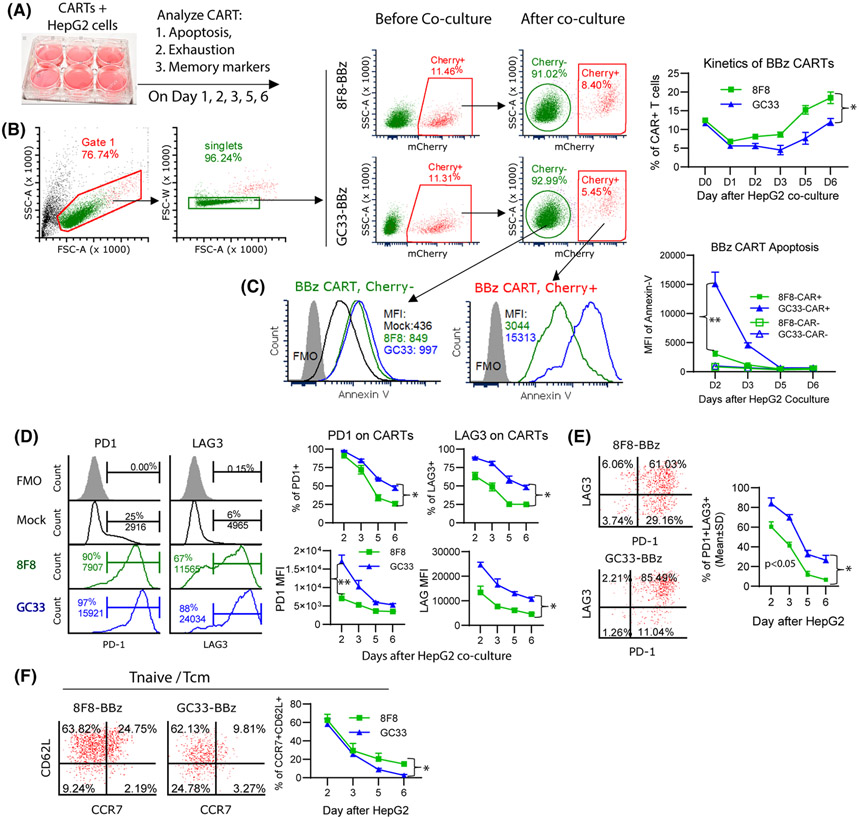

8F8 CARTs are less exhausted and apoptotic after in vitro co-culture with tumor cells

We then conducted in vitro co-culture experiments to further study whether low-avidity 8F8 CART is less exhausted than GC33 CART after engaging with target tumor cells (Figure 8A). First, our data showed that the percentage of CART decreased during their initial 1–3 days’ co-culture with HepG2 cells (Figure 8B). The decrease of 8F8 CART was mild compared with GC33 CART. This observation is in agreement with a previous report that CART could be depleted by tumor cells.[25] After 2–3 days, the percentage of CARTs began to recover and the 8F8 CART came back faster than GC33 CART. Second, compared with GC33, the 8F8 CART was much less apoptotic after interacting with HepG2 cells (Figure 8C). The MFI of Annexin V on 8F8-BBz CART was 5 times lower than GC33-BBz CART. Third, the 8F8 CART also expressed less PD1 and LAG3. Both the percentage and MFI of PD1 and LAG3 were lower on 8F8 CART than on GC33 CART (Figure 8D). The LAG3 and PD1 double-positive cells were less in 8F8 CART than GC33 CART (Figure 8E). Fourth, the 8F8 CART contained more CCR7 and CD62L double-positive central memory cells and naïve-like T cells after interacting with tumor cells (Figure 8F). The same pattern of less apoptosis and exhaustion was also observed in 8F8-28z CART than GC33-28z CART (Figure S17). The CART’s exhaustion and apoptosis were more severe when more tumor cells are present (Figure S17), further suggesting that the CART apoptosis and exhaustion are driven by antigen engagement and stimulation. In summary, the in vitro study supports in vivo findings and suggests that low-avidity CARTs are less prone to apoptosis and exhaustion while preserving memory-like properties, and thus will persist in solid tumors to achieve stronger and durable antitumor effect.

FIGURE 8.

8F8 CARTs are less exhausted and apoptotic, and contain more Tnaive/Tcm cells. (A) Experimental scheme. HepG2 cells and CAR-Ts were co-cultured at 2:1 ratio in triplicate wells. Cells were analyzed for apoptosis, exhaustion, and memory markers at indicated time points. (B) Gating strategy and kinetics of CAR+ changes. (C) Apoptosis staining of CAR− and CAR+ T cells after HepG2. The dynamic change of apoptosis are also summarized. (D,E) Percentage and MFI of exhaustion markers, and the percentage of PD1 and LAG3 double-positive cells after HepG2 stimulation. (F) Percentage of Tnaive/Tcm in the CAR+ cells after HepG2 co-culture. Each data point represents mean ± SD of triplicate wells. The experiments were repeated 3 times with similar observation. Statistics were performed with ANOVA. *p < 05; **p < 0.01. FSC-A, forward scatter–area; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PD1, programmed death 1

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed a low-affinity 8F8 mAb and created low-avidity CARTs. We found that, compared with high-avidity GC33 CARTs, the low-avidity 8F8-BBz CART generated enhanced expansion and persistence in vivo. Importantly, more 8F8-BBz CARTs infiltrated into tumor lesions, which resisted exhaustion and maintained better effector function, resulting in durable antitumor effects. GPC3 is detected in about 70% of HCC and 50% of squamous lung cancers, but not in normal tissues.[41] The low-avidity 8F8-BBz CART should have a better therapeutic potential in treating HCC and other hGPC3+ solid tumors. In addition, as loss of effector function is one of the main obstacles to solid tumor immunotherapy, the findings made in this study may encourage more investigations to developing CARTs of proper avidity for other solid tumors.

Several factors can influence CART’s avidity. Obviously, the affinity of scFv and CAR expression level will affect CART’s avidity. 8F8 mAb has 17 times lower affinity than GC33. Not surprisingly, 8F8 CAR binds 4 times less of hGPC3 compared with GC33 CAR (Figure S11). In addition, our study showed that the ICD also affected CAR’s avidity even though they were only known to affect CART’s activation by different signaling strength.[38] We showed that 28z CARs bound 2 times more of the antigen hGPC3 than BBz CARs, partly due to higher CAR expression (28z CAR is 1.3 times higher than BBz CAR). The higher avidity of 28z CAR, together with its stronger signaling, generates faster and stronger activation to kill tumor cells. However, it will also result in more severe exhaustion, apoptosis, and loss of function than BBz CART when the antigen is persistent—a likely scenario in solid tumor. Consistent with this reasoning, among the four CARTs, GC33-28z CART has the highest avidity, exhaustion, apoptosis, and the fastest loss of effector function. These data may also explain why the antitumor efficacy of GC33-28z CART in clinical trials is low.[24] In contrast, although the antitumor effects of low-avidity CARTs may be slow, their long survival and maintenance of function in tumor lesions produces durable effects. The affinity/avidity thresholds are likely not universal and depend on interconnected factors such as antigen densities on target cells, CAR expression levels, binding epitope location, and ICD.[42] As CAR signaling strength above a certain threshold may not be beneficial but rather detrimental,[43] CARs should be optimized by finely balancing the desired avidity, signaling strength, antitumor response, and potential off-tumor toxicity. Such efforts may lead to the development of CARTs that have stronger resistance to exhaustion and apoptosis while maintaining better function to treat solid tumors.

Mechanistically, the low-avidity CAR may likely shorten the duration of engagement with tumor cells. The low-avidity CART with faster dissociation rate will easily disengage from tumor cells. The “fly-kiss” style engagement is typical in treating blood cancers, as the CARTs will enjoy a break after each individual killing before finding the next target, which avoids exhaustion. This is inconsistent with recent studies showing that the controlled CAR expression by synthetic Notch circuit only after engaging with tumor cells[44] or transient inducible shut-off of CAR expression[45] enhanced CART’s persistence and antitumor effects. In both cases, CARTs have a break time by disengaging with tumor cells to avoid exhaustion.

Other than CART’s avidity, the antigen heterogeneity of tumor cells and suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) also contribute to the low efficacy of solid tumor CART therapy. We found that, although the low-avidity 8F8-BBz CART extended survival, it did not eradicate large tumors (> 2-day IP tumors) (Figure S12). The exhaustion-resistant low-avidity CARTs alone may be insufficient to exert strong antitumor effects because of the suppressive TME in well-established tumors.[46] Additional measures to counteract immune suppression are needed to fully enable the CART function even when they are available and persistent in tumor mass. Our data showed that tumor-infiltrating 8F8 CARTs are PD1 and LAG3 positive, but are 2–3 times less exhausted than GC33 CARTs. The low-avidity CARTs stay in a “lightly exhausted” state (PD1lo), rather than entering a “deeply exhausted” state (PDhi)[47] in the tumor, likely due to the weak engagement. Recent study showed that the effector function of this PDlo, but not PDhi T cells, was reversible by checkpoint blockade.[48] These function-reversible lightly exhausted (PD1lo) low-avidity CARTs will create an opportunity for combination therapy. It will be interesting to study whether the combination of checkpoint blockades will further enhance the antitumor effects of low-avidity CARTs, which may eventually lead to successful solid tumor therapy.

Supplementary Material

Funding information

Supported by Augusta University start-up fund

Abbreviations:

- ACT

adoptive cell transfer

- BLI

bioluminescent intensity

- CAR

chimeric antigen receptor

- CART

CAR-modified T cell

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- HepG2-luc

HepG2 cells expressing luciferase

- hGPC3

human glyppican-3

- IFNγ

interferon-γ

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- ICD

intracellular domain

- IP

intraperitoneal

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- SC

subcutaneous

- scFv

single-chain variable fragment

- VH

variable region of heavy chain

- VL

light chain variable region

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. A. Ruth He is on the speakers’ bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eisai. She received grants from Merck and Genentech.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pico de Coana Y, Choudhury A, Kiessling R. Checkpoint blockade for cancer therapy: revitalizing a suppressed immune system. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:482–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu W, Peng Y, Wang L, Hong Y, Jiang X, Li Q, et al. Identification of alpha-fetoprotein-specific T-cell receptors for hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Hepatology. 2018;68:574–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caraballo Galva LD, Cai L, Shao Y, He Y. Engineering T cells for immunotherapy of primary human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Genet Genomics. 2020;47:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thommen DS, Schumacher TN. T cell dysfunction in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:547–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hombach A, Hombach AA, Abken H. Adoptive immunotherapy with genetically engineered T cells: modification of the IgG1 Fc ‘spacer’ domain in the extracellular moiety of chimeric antigen receptors avoids ‘off-target’ activation and unintended initiation of an innate immune response. Gene Ther. 2010;17:1206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long AH, Haso WM, Shern JF, Wanhainen KM, Murgai M, Ingaramo M, et al. 4–1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Med. 2015;21:581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gargett T, Yu W, Dotti G, Yvon ES, Christo SN, Hayball JD, et al. GD2-specific CAR T cells undergo potent activation and deletion following antigen encounter but can be protected from activation-induced cell death by PD-1 blockade. Mol Ther. 2016;24:1135–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Aloia MM, Zizzari IG, Sacchetti B, Pierelli L, Alimandi M. CAR-T cells: the long and winding road to solid tumors. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majzner RG, Mackall CL. Clinical lessons learned from the first leg of the CAR T cell journey. Nat Med. 2019;25:1341–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayaraman J, Mellody MP, Hou AJ, Desai RP, Fung AW, Pham AHT, et al. CAR-T design: elements and their synergistic function. EBioMedicine. 2020;58:102931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudecek M, Lupo-Stanghellini MT, Kosasih PL, Sommermeyer D, Jensen MC, Rader C, et al. Receptor affinity and extracellular domain modifications affect tumor recognition by ROR1-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:3153–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynn RC, Feng Y, Schutsky K, Poussin M, Kalota A, Dimitrov DS, et al. High-affinity FRβ-specific CAR T cells eradicate AML and normal myeloid lineage without HSC toxicity. Leukemia. 2016;30:1355–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richman SA, Nunez-Cruz S, Moghimi B, Li LZ, Gershenson ZT, Mourelatos Z, et al. High-affinity GD2-specific CAR T cells induce fatal encephalitis in a preclinical neuroblastoma model. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghorashian S, Kramer AM, Onuoha S, Wright G, Bartram J, Richardson R, et al. Enhanced CAR T cell expansion and prolonged persistence in pediatric patients with ALL treated with a low-affinity CD19 CAR. Nat Med. 2019;25:1408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao H, Li K, Tu H, Pan X, Jiang H, Shi B, et al. Development of T cells redirected to glypican-3 for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li D, Li N, Zhang Y-F, Fu H, Feng M, Schneider D, et al. Persistent polyfunctional chimeric antigen receptor T cells that target glypican 3 eliminate orthotopic hepatocellular carcinomas in mice. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2250–65.e2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Gao F, Jiang L, Jia M, Ao L, Lu M, et al. 32A9, a novel human antibody for designing an immunotoxin and CAR-T cells against glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2020;18:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumhoer D, Tornillo L, Stadlmann S, Roncalli M, Diamantis EK, Terracciano LM. Glypican 3 expression in human non-neoplastic, preneoplastic, and neoplastic tissues: a tissue microarray analysis of 4387 tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano K, Orita T, Nezu J, Yoshino T, Ohizumi I, Sugimoto M, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibodies cause ADCC against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phung Y, Gao W, Man YG, Nagata S, Ho M. High-affinity monoclonal antibodies to cell surface tumor antigen glypican-3 generated through a combination of peptide immunization and flow cytometry screening. MAbs. 2012;4:592–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi D, Shi Y, Kaseb AO, Qi X, Zhang Y, Chi J, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-glypican-3 T-cell therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: results of phase I trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:3979–3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoseini SS, Dobrenkov K, Pankov D, Xu XL, Cheung NK. Bispecific antibody does not induce T-cell death mediated by chimeric antigen receptor against disialoganglioside GD2. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1320625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Jiang S, Fang C, Yang S, Olalere D, Pequignot EC, et al. Affinity-tuned ErbB2 or EGFR chimeric antigen receptor T cells exhibit an increased therapeutic index against tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3596–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park S, Shevlin E, Vedvyas Y, Zaman M, Park S, Hsu Y-M, et al. Micromolar affinity CAR T cells to ICAM-1 achieves rapid tumor elimination while avoiding systemic toxicity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salzer B, Schueller CM, Zajc CU, Peters T, Schoeber MA, Kovacic B, et al. Engineering AvidCARs for combinatorial antigen recognition and reversible control of CAR function. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329:112–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chi X, Yan R, Zhang J, Zhang G, Zhang Y, Hao M, et al. A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369:650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Y, Zhang J, Mi Z, Robbins P, Falo LD Jr. Immunization with lentiviral vector-transduced dendritic cells induces strong and long-lasting T cell responses and therapeutic immunity. J Immunol. 2005;174:3808–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong Y, Peng Y, Guo ZS, Guevara-Patino J, Pang J, Butterfield LH, et al. Epitope-optimized alpha-fetoprotein genetic vaccines prevent carcinogen-induced murine autochthonous hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59:1448–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V, Duroux P, Jabado-Michaloud J, Folch G, Aouinti S, et al. IMGT(R), the international ImMunoGeneTics information system(R) 25 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D413–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishiguro T, Sugimoto M, Kinoshita Y, Miyazaki Y, Nakano K, Tsunoda H, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibody as a potential antitumor agent for human liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9832–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haruyama Y, Kataoka H. Glypican-3 is a prognostic factor and an immunotherapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:275–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hombach AA, Schildgen V, Heuser C, Finnern R, Gilham DE, Abken H. T cell activation by antibody-like immunoreceptors: the position of the binding epitope within the target molecule determines the efficiency of activation of redirected T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James SE, Greenberg PD, Jensen MC, Lin Y, Wang J, Till BG, et al. Antigen sensitivity of CD22-specific chimeric TCR is modulated by target epitope distance from the cell membrane. J Immunol. 2008;180:7028–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drent E, Poels R, Ruiter R, van de Donk NWCJ, Zweegman S, Yuan H, et al. Combined CD28 and 4–1BB costimulation potentiates affinity-tuned chimeric antigen receptor-engineered T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:4014–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao W, Tang Z, Zhang YF, Feng M, Qian M, Dimitrov DS, et al. Immunotoxin targeting glypican-3 regresses liver cancer via dual inhibition of Wnt signalling and protein synthesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe K, Terakura S, Martens AC, van Meerten T, Uchiyama S, Imai M, et al. Target antigen density governs the efficacy of anti-CD20-CD28-CD3 zeta chimeric antigen receptor-modified effector CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2015;194:911–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamauchi N, Watanabe A, Hishinuma M, Ohashi K-I, Midorikawa Y, Morishita Y, et al. The glypican 3 oncofetal protein is a promising diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1591–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arcangeli S, Rotiroti MC, Bardelli M, Simonelli L, Magnani CF, Biondi A, et al. Balance of anti-CD123 chimeric antigen receptor binding affinity and density for the targeting of acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1933–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Künkele A, Johnson AJ, Rolczynski LS, Chang CA, Hoglund V, Kelly-Spratt KS, et al. Functional tuning of CARs reveals signaling threshold above which CD8+ CTL antitumor potency is attenuated due to cell Fas–FasL-dependent AICD. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:368–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyrenius-Wittsten A, Su Y, Park M, Garcia JM, Alavi J, Perry N, et al. SynNotch CAR circuits enhance solid tumor recognition and promote persistent antitumor activity in mouse models. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabd8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weber EW, Parker KR, Sotillo E, Lynn RC, Anbunathan H, Lattin J, et al. Transient rest restores functionality in exhausted CAR-T cells through epigenetic remodeling. Science. 2021;372:eaba1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fuca G, Reppel L, Landoni E, Savoldo B, Dotti G. Enhancing chimeric antigen receptor T-cell efficacy in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu-Monette ZY, Zhang M, Li J, Young KH. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: have we found the key to unleash the antitumor immune response? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Philip M, Fairchild L, Sun L, Horste EL, Camara S, Shakiba M, et al. Chromatin states define tumour-specific T cell dysfunction and reprogramming. Nature. 2017;545:452–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.