Abstract

Acting on the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are mechanisms of some of the most prescribed medications in the world. In addition to their routine use for the treatment of hypertension, such agents have gained attention for their influence on the angiotensin receptor pathway in fibrotic skin disorders, including scars and keloids. To evaluate the current level of evidence supporting the use of these agents, a systematic review related to ACE-Is/ARBs and cutaneous scarring was conducted. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus from database inception through January 26, 2022. Two independent reviewers identified eligible studies for inclusion and extracted data. Data were insufficient for meta-analysis and are presented narratively. Of 461 citations identified, seven studies were included (199 patients). The studies included two randomized clinical trials, one comparative observation study, and four case reports. All the included studies reported statistically significant improvement in cutaneous scarring in patients using ACE-Is/ARBs compared with that in those treated with placebo/control using various outcome measures such as scar size and scar scales. However, much of the literature on this subject to date is limited by study design.

Introduction

Cutaneous scarring, including keloids and hypertrophic scarring, is associated with morbidity in the form of physical symptoms such as pruritus and pain but can also have an equally debilitating psychological burden on the individual (Brown et al., 2008; Sobanko et al., 2015). Fibrosis also plays a critical role in skin disorders such as venous stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, diabetic foot wounds, and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (Elliott and Hamilton, 2011; Liu et al., 2017; Miteva et al., 2010; Rosenbloom et al., 2017; Sundaresan et al., 2017). Moreover, cutaneous fibrosis can provide an understanding of fibrotic processes affecting the liver, kidneys, and heart. For classic hypertrophic cutaneous scars, commonly employed treatments include intralesional corticosteroid injection, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) injection, cryotherapy, laser therapy, topical tretinoin, and surgical excision (Ojeh et al., 2020). However, the clinical effectiveness of many of these treatments is suboptimal with frequent recurrences, especially in populations commonly afflicted with hypertrophic scars such as people of Black African or East Asian descent (Brown et al., 2008; Glass, 2017; Kassi et al., 2020; Shaffer et al., 2002). Furthermore, many treatment options are painful and time consuming because they require multiple treatment sessions. These factors can exacerbate patient dissatisfaction and lead to premature cessation of therapy (Ledon et al., 2013). The lack of universally accepted standardized guidelines or treatment protocols for pathologic scarring reflects the paucity of available high-quality evidence for their effectiveness (Betarbet and Blalock, 2020; Ledon et al., 2013).

Pathologic scarring and fibrosis can be defined at the tissue level by over-exuberant deposition of extracellular matrix components, primarily collagen, due to dysregulation of various cytokines such as TGF-β and PDGF. These chemical messengers cause increased activation of fibroblasts and lead to excess collagen deposition and development of the clinical signs of keloidal/hypertrophic scarring (Andrews et al., 2016; Baker et al., 2009). In addition, the ratios of subtypes of collagen present in pathologic scars can differ from those of normal skin. Hypertrophic scars have been shown to contain mostly collagen type III, whereas keloids contain both disorganized type I and type III collagen. Both types of scars involve overproduction of fibroblast products due to aberrant persistence of fibrotic cytokines and/or failure to downregulate fibroblasts, in contrast to scarless mucosal or fetal wound healing, which is often a lower inflammatory state (Slemp and Kirschner, 2006). An observation of patients developing nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after gadolinium exposure noted that none had received angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy, hinting at a potential preventative mechanism (Fazeli et al., 2004).

ACE inhibitors (ACE-Is) and ARBs are some of the most prescribed pharmacologic agents in the world. The renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and especially angiotensin II have recently been shown to play a prominent role in a variety of fibrotic diseases (Wynn, 2008). Angiotensin II is involved in the fibrotic remodeling of cardiac tissue and the development of hypertensive heart disease (Porter and Turner, 2009). ACE-Is are therefore often used as first-choice agents for essential hypertension, although of note, they are teratogenic and are avoided in childbearing females (Unger et al., 2020). ACE-Is have also been shown to reduce the effect of fibrotic diseases in other tissues such as in diabetic kidney disease and are first line for the treatment of hypertension in patients with comorbid diabetes (Mezzano et al., 2001; Unger et al., 2020).

Although angiotensin II is highly profibrotic and proinflammatory, conversion of angiotensin II to angiotensin 1–7 by ACE2 causes a vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, and antifibrotic tendency (Figure 1) (Pagliaro and Penna, 2020). Angiotensin II receptors are also found in skin fibroblasts and likely play a role in fibrosis/scarring of cutaneous wounds owing to the upregulation of fibrogenic factors, including TGF-β isotypes, which activate SMAD and Wnt pathways, thereby activating fibroblasts (Fang et al., 2018; Hedayatyanfard et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020). Thus, the RAAS may be of greater relevance to cutaneous fibrosis than previously realized.

Figure 1.

Graphical overview of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ACE-1, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; Ang 1-7, angiotensin 1–7; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Multiple animal studies have demonstrated a role for the RAAS in cutaneous fibrosis and scar formation, suggesting that regulation of the RAAS may be an effective treatment for these conditions in humans. Five studies (Demir et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2019; Rha et al., 2021; Tan et al., 2018; Uzun et al., 2013) explored the effect of systemic (oral) ACE-I/ARB in mice, rats, and rabbits. All of these studies showed favorable outcomes in the ACE-I/ARB groups, manifesting smaller, softer, less erythematous, and flatter scars in mature scars. Pathological findings were significant for decreased fibroblasts, diminished collagen type III and total collagen density with decreased activation of α-smooth muscle actin, and increased type I collagen fiber density. Three studies (Kim et al., 2012; Safaee Ardekani et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2019) studied the effect of topical ACE/ARB in rabbits and mice, showing decreased scar width and scar elevation index (Table 1). On the basis of the promise of these preclinical animal studies, a systematic review was conducted to examine the current evidence suggesting the use of ACE-I/ARB agents in the treatment of cutaneous scarring in humans and to highlight areas in need of further research.

Table 1.

Summary of Animal Studies Investigating the Use of ACE-I/ARBs in Wound Healing

| Reference | Methods | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Animal studies, oral ACE/ARB | ||

| Rha et al., 2021 | Subjects A total of 16 hypertensive and 16 normotensive rats with punch biopsy wounds. Intervention Half of the rats began on a regimen of 100 mg/kg of oral captopril starting on day 21 after wounding. Evaluation was conducted on day 36. |

Clinical Median scar area was smaller in treated rats (P < 0.0001). Pathologic Median capillary counts were lower in the wounds of treated rats. α-SMA had decreased expression in treated hypertensive and normotensive rats (P = 0.0000). |

| Uzun et al., 2013 | Subjects A total of 16 rabbits with ear punch biopsy wounds. Intervention Four treatment groups consisting of 0.75 mg/kg/day oral enalapril immediately upon wounding, enalapril treatment at day 28 after wounding, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, 40 mg/ml on days 28 and 35, and control. Evaluation was conducted on day 21. |

Clinical Both enalapril-treated groups had scars that were softer, less erythematous, and less elevated (P < 0.005). Pathologic Median fibroblast count was lower in both enalapril-treated groups (P < 0.005)—lowest in the steroid group. Collagen type I immunoreactivity was higher, and collagen type III immunoreactivity was lower in the early enalapril-treated group than in the late enalapril-treated and control groups. |

| Demir et al., 2018 | Subjects A total of 20 rabbits with ear punch biopsy wounds. Intervention Five groups consisting of sham procedure, control, oral enalapril (0.75 mg/kg/day starting at day 0), oral candesartan (1 mg/kg/day starting at day 0), and intralesional corticosteroids (0.8 mg/1ml triamcinolone acetonide to ear scar on days 28 and 35). Evaluation was conducted on day 40. |

Clinical ACE-I–, ARB-, and steroid-treated groups had scars that were less hyperemic, more flattened, and softer (P = 0.001)—greatest effect in the steroid-treated group. Pathologic Fibroblast numbers were lower in ACE-I– and steroid-treated groups (P = 0.001)—lowest in sham-treated group Total collagen density was lower in all treatment groups (P = 0.001). Type I collagen fiber density was higher in treatment groups, whereas type III collagen fiber density was lower (P = 0.001). |

| Murphy et al., 2019 | Subjects A total of 12 mice with mechanically induced hypertrophic scars. Intervention Mice were randomized to receive 1 mg/kg losartan versus normal drinking water starting on day 0. Evaluation was conducted on day 28. |

Clinical Scars in losartan-treated mice had decreased scar area (P = 0.002) and decreased elevation index (P = 0.003). Pathologic Decreased activation of α-SMA by immunostaining quantification (P < 0.0001), fewer CD68+ monocyte/macrophage lineage cells (P < 0.001), and lower density of thick mature collagen I fibers (P = 0.02). |

| Tan et al., 2018 | Subjects A total of 24 ACE wild-type mice with excision wounds. Intervention Four treatment groups consisting of oral ramipril (10 mg/kg/day), losartan (10 mg/kg/day), hydralazine (40 mg/kg/day), or water alone starting on day 0. An additional group of six ACE knockout mice were treated with water alone. Evaluation was conducted on day 14. |

Clinical Ramipril-treated, losartan-treated, and ACE-knockout mice all had decreased scar width, more loosely arranged collagen fibers, fewer fibroblasts, enhanced re-epithelialization, as well as more organized granulation tissue and neovascularization (P < 0.05). Pathologic Expression of TGF-β1 was lower in scar tissue of knockout, ramipril-, and losartan-treated mice. |

| Animal studies, topical ACE/ARB | ||

| Zheng et al., 2019 | Subjects A total of 50 mice with excision wounds. Intervention Multiple groups of varying concentrations of ramipril and losartan along with a triamcinolone urea cream group starting on day 14 and a no-treatment group. Evaluation was conducted on day 30. |

Clinical 0.2% losartan urea cream–treated group, 0.1% ramipril urea cream–treated group, and triamcinolone urea cream–treated group had a reduction in scar width (P < 0.05)—no significant difference between these groups. 0.1% losartan, 0.1% ramipril-urea, 0.1% losartan-urea, 0.1% ramipril-urea with azone, and 0.1% losartan-urea with azone showed no significant difference from no treatment in scar width. |

| Safaee Ardekani et al., 2008 | Subjects Six rabbits with bilateral ear excision wounds. Intervention Left ear wounds were treated with daily application of topical 5% captopril starting on day 0. Right ear wounds were treated with vehicle alone. Evaluation was conducted on day 28. |

Clinical Treated wounds had a decreased scar elevation index (P < 0.05). |

| Kim et al., 2012 | Subjects A total of 18 rabbits with bilateral ear punch biopsy wounds. Intervention Three groups: topical celecoxib alone, topical captopril alone, and both agents. The contralateral ear was treated with vehicle alone as a control. |

Clinical Scar elevation index of the captopril alone group was lower (P = 0.008). The group with both agents had the greatest decrease in scar elevation (P = 0.008). Pathologic Decreased collagen deposition in the group with both agents (P = 0.035). |

Abbreviations: α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

Results

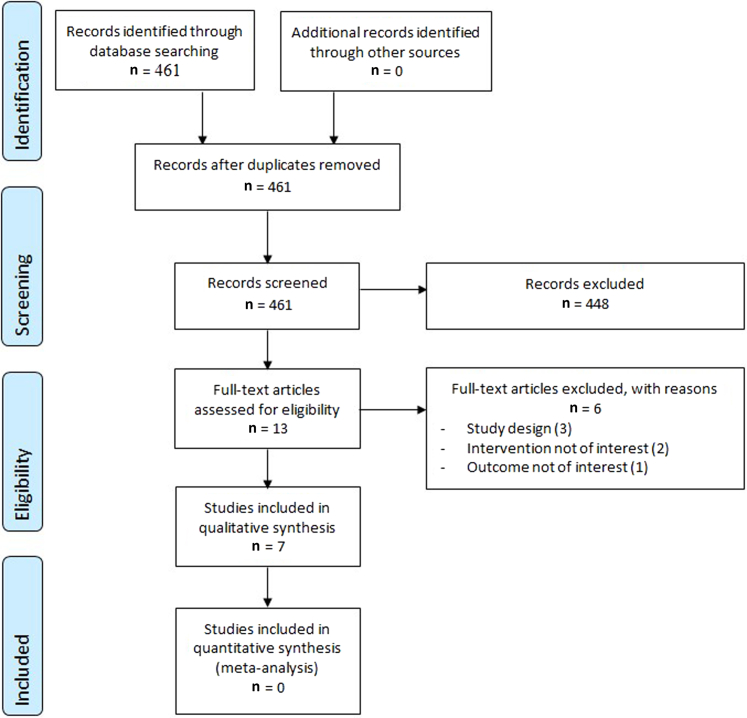

The literature search identified 461 citations, of which seven studies met the inclusion criteria, including a total of 199 patients (Figure 2). There were two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Hedayatyanfard et al., 2018; Mohammadi et al., 2018), one comparative observational study (Hu et al., 2020), and four case reports including five total patients (Ardekani et al., 2009; Alexandrescu et al., 2016; Iannello et al., 2006; Ogawa et al., 2013). The RCTs were conducted in Iran; the observational study was conducted in China; and the case reports were conducted in each of United States, Iran, Italy, and Japan (Table 2). The risk of bias in the included RCTs and the observational study was high (Tables 3 and 4). None of the human-based studies included a primary outcome-based power calculation.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review

| Author, y | Country, Institution, Study Period |

Methods | Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Number of Patients | Mean Age (y) | Male% | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al., 2020 | China, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, June 2015–June 2018 |

134 patients with thyroidectomy scars divided into four groups: ACE-I–treated group, ARB-treated group, other antihypertensive drugs control–treated group, and blank control–treated group | Post-thyroidectomy scars, without hypertension or with well-controlled hypertension (<140/90 mm Hg). | All (134) ACE-I (22) ARB (24) Other antihypertensive drugs (34) Blank control (54) |

55 51 58 58 53 |

19% 36% 17% 9% 19% |

Width, length, SCAR score |

| Hedayatyanfard et al., 2018 | Iran, Shahid Beheshti University and Modarres Hospital, 2015–2016 |

Subjects 37 patients each with keloid or hypertrophic scarring >2 cm in length. Intervention Patients were randomized to receive either topical 5% losartan cream or placebo twice daily for 3 months. |

Scars >2 cm in length for <6 months. Not taking antihypertensive drugs, not pregnant, no malignancy, no allergy history, no bleeding and discharge in scar tissue, and no scar treatment in the past 2 months. | All (30) Losartan (20) Placebo (17 with 10 included in the analysis) |

31.7 47.6 | 50% 30% |

Vancouver Scar Scale |

| Mohammadi et al., 2018 | Iran, Shiraz Burn and Wound Healing Research Center |

Subjects 30 patients each with two same-degree hypertrophic scars on symmetrical body sites. Intervention Scar sites in each subject were randomized to receive 1% enalapril ointment or placebo twice daily for 6 months. |

Hypertrophic scars and itching after second- or third-degree burns with same-degree scars on symmetrical anatomic body sites. | 30 1% enalapril ointment and Placebo |

NA | 50% | Scar size |

| Alexandrescu et al., 2016 | US, University of San Diego |

Male aged 30 years with five chest keloids: one received intralesional 5-FU/TMC, one received intralesional 5-FU/verapamil, one received intralesional enalapril alone, one received intralesional verapamil alone, and the last one underwent fractional carbon dioxide laser. Each injection was done at 1-week intervals for a total of 17 treatments. | Male aged 30 years with five chest keloids. | 1 | 30 | 100% | Diameter change, softening, height, pain, itching. |

| Ardekani et al., 2009 | Iran, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences |

Case report of a female aged 18 years with a burn injury–induced keloid treated with topical 5% captopril cream twice daily for 4 months. | Female aged 18 years with a left dorsal hand burn injury–induced keloid treated with topical 5% captopril cream twice daily. | 1 | 18 | 0% | Keloid height and redness |

| Iannello et al., 2006 | Italy, University of Catania |

Case study of two patients with keloid scarring after abdominal surgery who were subsequently started on oral antihypertensive therapy containing enalapril for 3–4 months and 6 months of treatment, respectively. | Two patients with postsurgical keloidal scarring who were initiated on oral antihypertensive therapy containing the ACE-I enalapril | 2 | 62 | 0% | Keloid improvement |

| Ogawa et al., 2013 | Japan, Nippon Medical School |

Case report of a female aged 63 years with right arm keloids who received treatment with surgical excision and postoperative radiation therapy, which was supplemented with amlodipine and candesartan systemically for 2 years. | Woman aged 63 years with hypertension and right arm keloids, treated with surgery, radiation therapy, amlodipine, and candesartan cilexetil. | 1 | 63 | 0% | Symptom improvement |

Abbreviations: 5-FU, fluorouracil; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; NA, not applicable; SCAR, Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating; TMC, triamcinolone; US, United States.

Table 3.

Methodological Quality of Observational Studies Using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

| Author, y | Representativeness of the Study Population |

Ascertainment of Exposure | Comparability | Assessment of Outcome | Adequacy of Follow-Up | Conflict of Interest | Overall ROB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu et al., 2020 | High ROB | High ROB | High ROB | Low ROB | Low ROB | Low ROB | High ROB |

Abbreviation: ROB, risk of bias.

Table 4.

Methodological Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials Using Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias 2 tool

| Author, y | Bias Arising from the Randomization Process | Bias Due to Deviations from Intended Interventions | Bias Due to Missing Outcome Data | Bias in Measurement of the Outcome | Bias in Selection of the Reported Result | Risk of Bias Judgement Low/High/Some Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedayatyanfard et al., 2018 | High | High | High | Low | Low | High risk |

| Mohammadi et al., 2018 | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | High | High risk |

One double-blinded RCT compared the effect of 1% topical enalapril on hypertrophic scars with that of placebo. A total of 30 subjects were selected among patients who had two same-degree scars on symmetrical anatomic sites so that medication and placebo could be administered simultaneously, with each patient acting as their own control. The trial ointment and placebo were transferred into unlabeled containers with varying colors to blind both trial participants and coordinators. ACE-I–treated scars were significantly smaller in mean thickness than the placebo-treated ones (2.02 ± 0.55 vs. 2.3 ± 0.64 cm), and mean itching score was significantly lower (1.73 ± 0.69 vs. 2.43 ± 0.67) (Mohammadi et al., 2018). A single-blind RCT compared topical cream of losartan with placebo, assessing scars according to the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) (Sullivan et al., 1990). VSS scores dropped significantly for both keloids and hypertrophic scars in the losartan-treated group (n = 20) compared with that in the placebo-treated group (n = 17). Of the original 37 recruited patients, 7 patients from the placebo group ended participation owing to perceived lack of effect and were not included in the final analysis (Hedayatyanfard et al., 2018). The observational study found that scars from the ARB-treated group (n = 24) were narrower than scars in the other antihypertensive-treated (n = 34) and control (n = 54) groups (1.57 ± 0.45 mm, 2.09 ± 0.79 mm, 2.00 ± 0.93 mm, respectively). Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (SCAR) scale assessment (Kantor, 2017) showed improved ratings of scar spread, hypertrophy/atrophy, overall impression, and total score in the ACE-I–treated group compared with that in the other antihypertensive-treated and control groups. In this study, there was no significant statistical difference between the ACE-I–treated group and the ARB-treated group in terms of scar width or SCAR scale measurement (Hu et al., 2020).

Case reports

Four studies including five case reports were included. Iannello et al. (2006) described two patients: females aged 54 and 70 years each with postsurgical keloidal scarring who were initiated on oral antihypertensive therapy with 10 mg enalapril daily. The first patient witnessed a keloidal improvement of a 4-month postsurgical abdominal scar with near-complete resolution after 15 days and complete resolution of other chronic hypertrophic scars from remote surgical procedures after 3–4 months. In the second patient, chronic postsurgical abdominal keloids improved over the course of 6 months with the same enalapril regimen.

Successful topical therapy was reported by Ardekani et al. (2009) who described a female patient aged 18 years with a burn injury–induced keloid on the dorsum of her left hand treated with topical 5% captopril cream twice daily. The lesion decreased in height and improved in redness after 6 weeks.

Alexandrescu et al. (2016) described a male aged 30 years with five chest keloids, each uniquely treated with intralesional injections: one received 5-FU/triamcinolone (TMC) (50 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, mixed as 0.9 cc 5-FU/0.1 cc TMC), one received 5-FU/verapamil (50 mg/ml, 2.5 mg/ml, mixed as 0.5 cc 5-FU/0.5 cc verapamil), one received enalapril alone (0.125 mg/ml), one received verapamil alone (2.5 mg/ml), and the last one underwent fractional carbon dioxide laser. Enalapril showed the largest diameter change than the other treatment regimens. Furthermore, the enalapril-treated scar demonstrated a 30% improvement in scar softness and a 20% decrease in height. All scars treated in the study had resolution of pain and itching after 4 months.

One additional case was reported by Ogawa et al. (2013) detailing a woman aged 63 years with hypertension who had extensive keloids covering her right arm. Multimodal treatment with surgical excision and postoperative radiation therapy was supplemented with amlodipine as well as oral candesartan cilexetil (dose not specified), resulting in improvement in symptoms.

Discussion

There have been very limited studies on using ACE-Is/ARBs for cutaneous scarring and keloids. Although all included studies in our systematic review showed an effect that favors the use of the ACE-Is/ARBs, the risk of bias in these studies is high, and the certainty of evidence derived from them is very low, which highlights a number of areas in need of further research.

The small number of human studies available have limitations in their methodology (limited statistical power, lack of appropriate control, skewed male-to-female population, deviations from intended interventions/subject attrition, etc.). Important questions concerning the timing of the response to an ACE-I or ARB in the scarring process need to be delineated on the basis of the results of the human and animal studies discussed earlier. Specifically, some animal studies demonstrate increased efficacy with prophylactic application of ACE-Is and ARBs immediately after wounding versus delayed application of agents after pathologic scarring had already developed. None of the human-based studies examined in this review evaluated the use of ACE-I or ARB therapies immediately after wounding and instead examined the use of these agents exclusively after the prior development of pathologic scarring. Because limited therapeutic options currently exist for prophylactic scar minimization through the application of agents immediately prior to or after wounding, ACE-Is and ARBs offer the promise of a new therapeutic avenue as primary preventative agents, especially given their already established extensive use in clinical medicine and their favorable safety profile at customary dosage. Further RCTs investigating the application of ACE-Is and ARBs starting immediately after skin injury or periprocedurally are recommended, especially in populations prone to developing pathologic scarring (e.g., keloidal scarring in patients with skin of color). Moreover, the easy availability of topical formulations of ACE-Is and ARBs allows for regionally directed therapy, thereby limiting unintentional systemic effects. The favorable side effect profile of these agents as topical formulations makes them especially amenable for use as primary preventative agents and underscores the recommended precedence in investigating topical ACE-Is/ARBs in further RCTs. In addition, there may be a role for utilizing ACE-Is/ARBs in combination with intralesional steroids to achieve a potential additive or synergistic benefit in keloidal treatment.

Overall, the efficacy of ACE-Is compared with that of ARBs in improving the clinical appearance of pathologic scarring appears to be equivocal. However, ACE-Is were more commonly used as study agents than ARBs in both human and animal studies. Given the initial lead of data using ACE-Is, along with the prior recommendation to focus study on topical agents, it may be prudent to focus further investigation on ACE-Is to facilitate concordance of data and interstudy comparison.

Furthermore, outcome measures reported among human studies were too heterogeneous to allow for reliable interstudy comparison. Several outcome measures of scarring currently exist, both subjective and objective in nature. Measurements of scar dimensions, color, and pliability offer objective comparisons between scars. Currently, the VSS is the most commonly cited subjective scale used to quantify scar appearance. However, the VSS does not include the patient’s own perception of the scar as does the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS). One human-based study described above noted a high degree of attrition due to subjects’ perceived lack of effect, highlighting the importance of a patient’s own assessment of the scar as a clinically relevant endpoint. Despite this, there is a current lack of established validity of subjective scar scales due to limited study (Fearmonti et al., 2010). The included human studies did not investigate outcome measures accounting for the patient’s subjective perception of scarring appearance, and we suggest that further studies include tools such as the POSAS in their analysis. Beyond this, further investigation into clinically relevant and valid outcome measures is necessary to establish a more standardized analysis of scarring, which would allow for more reliable interstudy comparison and validation.

Despite the limited number of human studies to date, numerous animal studies bolster the potential utility of ACE-I and ARB agents in scar treatment. Animal studies (murine, rabbit) involving trials of ACE/ARB agents (captopril, enalapril, ramapril, or losartan) including both systemic (oral) and topical routes of administration after intentional wounding have shown promising results. Limitations on the current research notwithstanding, the promise of angiotensin pathway targeting in cutaneous fibrosing states merits future high-quality RCTs and exploration.

Materials and Methods

The reporting of the systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statements (Moher et al., 2009).

Data sources and search strategies

A comprehensive search of several databases from each database’s inception to January 26, 2022, in any language, was conducted. The databases included Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily; Ovid Embase; Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from the study's principal investigator. Controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords was used to search for ACE-Is and ARBs for fibrotic skin disorders in patients. The actual strategy listing all search terms used and how they are combined is available in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were articles that described the use of topical or oral preparations of ACE-I/ARBs for the treatment of cutaneous scarring and keloids. We included RCTs, observational studies, case series, and case reports. We included human studies only. We did not restrict publication language, time, or location.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (TG and MA) screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies. Two independent reviewers reviewed the full texts of potentially included studies. Discrepancies between the reviewers were solved by discussions and consensus.

Data extraction and methodological quality assessment

A pilot-tested standardized data extraction form was used to extract data. The same two independent reviewers who performed the study selection then extracted data. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by consensus. To assess the risk of bias in included studies, we used the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias 2 tool for RCTs and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies (Sterne et al., 2019; Wells et al., 2000).

Outcome measures and analysis

Outcomes of interest were scar width and length, scar scales, and symptom improvement. Outcome data were insufficient for meta-analysis and were reported narratively.

Data availability statement

No large datasets were generated or analyzed during this study. Minimal datasets necessary to interpret and/or replicate data in this paper are available upon request to the corresponding author.

ORCIDs

Trenton Greif: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8259-9886

Mouaz Alsawas: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0814-4098

Alexander T. Reid: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8400-9042

Vincent Liu: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1987-9521

Larry Prokop: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7197-7260

M. Hassan Murad: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5502-5975

Jennifer G. Powers: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2202-6589

Conflict of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: TG, JGP; Formal Analysis: MA; Investigation: TG, MA; Methodology: MA, LP, MHM; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: TG, MA; Writing – Review and Editing; ATR, VL, JGP

corrected proof published online XXX

Footnotes

Cite this article as: JID Innovations 2023.100231

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.jidonline.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2023.100231.

Supplementary Materials and Methods

Search strategy

Ovid

Database(s): EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials December 2021, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 to January 20, 2022, Embase 1974 to 2022 January 25, Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily (1946) to January 25, 2022. The search strategy is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Scopus

TITLE-ABS-KEY ([skin or cutaneous or hypertrophic or surg∗ or wound∗] W/4 [cicatrices OR cicatrix OR cicatrization OR fibrosis OR fibrotic OR scar OR scarring OR scars] OR keloid OR keloidal OR keloide OR keloides OR keloids]).

TITLE-ABS-KEY("ACE inhibitor∗" OR alacepril OR altiopril OR amlodipine OR ancovenin OR "angiotensin converting enzyme antagonist∗" OR "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting agent∗" OR "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting drug∗" OR "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting medication∗" OR "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting therap∗" OR "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting treatment∗" OR "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor∗" OR "angiotensin i converting enzyme inhibitor∗" OR "angiotensin i-converting enzyme inhibitor∗" OR "angiotensin-converting enzyme antagonist∗" OR "Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor∗" OR "atorvastatin plus ramipril" OR benazepril OR benazeprilat OR Captopril OR ceranapril OR Cilazapril OR cilazaprilat OR "converting enzyme inhibitor∗" OR deacetylalacepril OR delapril OR "diltiazem plus enalapril maleate" OR "dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase i inhibitor∗" OR "dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase inhibitor∗" OR Enalapril OR Enalaprilat OR epicaptopril OR fasidotril OR fasidotrilat OR "felodipine plus ramipril" OR foroxymithine OR Fosinopril OR fosinoprilat OR gemopatrilat OR "hydrochlorothiazide plus lisinopril" OR "hydrochlorothiazide plus moexipril" OR "hydrochlorothiazide plus quinapril" OR "hydrochlorothiazide plus ramipril" OR idrapril OR ilepatril OR imidapril OR imidaprilat OR "indapamide plus perindopril" OR indolapril OR "kininase ii antagonist∗" OR "kininase ii inhibitor∗" OR libenzapril OR Lisinopril OR "lisinopril plus torasemdie" OR moexipril OR moexiprilat OR omapatrilat OR pentopril OR pentoprilat OR "peptidyl dipeptidase inhibitor∗" OR "peptidyldipeptide hydrolase inhibitor∗" OR Perindopril OR perindoprilat OR pivopril OR Quinapril OR quinaprilat OR Ramipril OR ramiprilat OR rentiapril OR "s nitrosocaptopril" OR sampatrilat OR spirapril OR spiraprilat OR temocapril OR temocaprilat OR Teprotide OR trandolapril OR "trandolapril plus verapamil" OR trandolaprilat OR utibapril OR utibaprilat OR "vasopeptidase inhibitor∗" OR zabicipril OR zabiciprilat OR zofenopril OR zofenoprilat)

TITLE-ABS-KEY("Angiotensin 2 agonist∗" OR "Angiotensin 2 block∗" OR "angiotensin 2 receptor agonist∗" OR "angiotensin 2 receptor antagonist∗" OR "angiotensin 2 receptor block∗" OR "angiotensin AT2 agonist∗" OR "angiotensin AT2 antagonist∗" OR "angiotensin AT2 block∗" OR "angiotensin AT2 receptor agonist∗" OR "angiotensin AT2 receptor antagonist∗" OR "angiotensin AT2 receptor block∗" OR "Angiotensin II agonist∗" OR "Angiotensin II block∗" OR "angiotensin II type 2 receptor agonist∗" OR "angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist∗" OR "angiotensin II type 2 receptor block∗" OR "AT2 agonist∗" OR "AT2 antagonist∗" OR "AT2 block∗" OR "AT2 receptor agonist∗" OR "AT2 receptor antagonist∗" OR "AT2 receptor block∗" OR Azilsartan OR Candesartan OR Eprosartan OR Irbesartan OR Losartan OR Olmesartan OR Telmisartan OR Valsartan)

1 and (2 or 3)

TITLE-ABS-KEY((alpaca OR alpacas OR amphibian OR amphibians OR animal OR animals OR antelope OR armadillo OR armadillos OR avian OR baboon OR baboons OR beagle OR beagles OR bee OR bees OR bird OR birds OR bison OR bovine OR buffalo OR buffaloes OR buffalos OR "c elegans" OR "Caenorhabditis elegans" OR camel OR camels OR canine OR canines OR carp OR cats OR cattle OR chick OR chicken OR chickens OR chicks OR chimp OR chimpanze OR chimpanzees OR chimps OR cow OR cows OR "D melanogaster" OR "dairy calf" OR "dairy calves" OR deer OR dog OR dogs OR donkey OR donkeys OR drosophila OR "Drosophila melanogaster" OR duck OR duckling OR ducklings OR ducks OR equid OR equids OR equine OR equines OR feline OR felines OR ferret OR ferrets OR finch OR finches OR fish OR flatworm OR flatworms OR fox OR foxes OR frog OR frogs OR "fruit flies" OR "fruit fly" OR "G mellonella" OR "Galleria mellonella" OR geese OR gerbil OR gerbils OR goat OR goats OR goose OR gorilla OR gorillas OR hamster OR hamsters OR hare OR hares OR heifer OR heifers OR horse OR horses OR insect OR insects OR jellyfish OR kangaroo OR kangaroos OR kitten OR kittens OR lagomorph OR lagomorphs OR lamb OR lambs OR llama OR llamas OR macaque OR macaques OR macaw OR macaws OR marmoset OR marmosets OR mice OR minipig OR minipigs OR mink OR minks OR monkey OR monkeys OR mouse OR mule OR mules OR nematode OR nematodes OR octopus OR octopuses OR orangutan OR "orang-utan" OR orangutans OR "orang-utans" OR oxen OR parrot OR parrots OR pig OR pigeon OR pigeons OR piglet OR piglets OR pigs OR porcine OR primate OR primates OR quail OR rabbit OR rabbits OR rat OR rats OR reptile OR reptiles OR rodent OR rodents OR ruminant OR ruminants OR salmon OR sheep OR shrimp OR slug OR slugs OR swine OR tamarin OR tamarins OR toad OR toads OR trout OR urchin OR urchins OR vole OR voles OR waxworm OR waxworms OR worm OR worms OR xenopus OR "zebra fish" OR zebrafish) AND NOT (human OR humans or patient or patients))

4 and not 5

DOCTYPE(ed) OR DOCTYPE(bk) OR DOCTYPE(er) OR DOCTYPE(no) OR DOCTYPE(sh)

6 and not 7

INDEX(Embase) OR INDEX(Medline) OR PMID(0∗ OR 1∗ OR 2∗ OR 3∗ OR 4∗ OR 5∗ OR 6∗ OR 7∗ OR 8∗ OR 9∗)

8 and not 9

Supplementary Table S1.

Search Strategy

| Number | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Cicatrix/ and (skin or cutaneous or hypertrophic or surg∗ or wound∗).ti,ab,hw,kw. | 84,121 |

| 2 | (((skin or cutaneous or hypertrophic or surg∗ or wound∗) adj4 (cicatrices or cicatrix or cicatrization or fibrosis or fibrotic or scar or scarring or scars)) or keloid or keloidal or keloide or keloides or keloids).ti,ab,hw,kw. | 65,327 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 120,220 |

| 4 | exp Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors/ | 239,514 |

| 5 | ("ACE inhibitor∗" or alacepril or altiopril or amlodipine or ancovenin or "angiotensin converting enzyme antagonist∗" or "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting agent∗" or "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting drug∗" or "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting medication∗" or "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting therap∗" or "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibiting treatment∗" or "angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor∗" or "angiotensin i converting enzyme inhibitor∗" or "angiotensin i-converting enzyme inhibitor∗" or "angiotensin-converting enzyme antagonist∗" or "Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor∗" or "atorvastatin plus ramipril" or benazepril or benazeprilat or Captopril or ceranapril or Cilazapril or cilazaprilat or "converting enzyme inhibitor∗" or deacetylalacepril or delapril or "diltiazem plus enalapril maleate" or "dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase i inhibitor∗" or "dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase inhibitor∗" or Enalapril or Enalaprilat or epicaptopril or fasidotril or fasidotrilat or "felodipine plus ramipril" or foroxymithine or Fosinopril or fosinoprilat or gemopatrilat or "hydrochlorothiazide plus lisinopril" or "hydrochlorothiazide plus moexipril" or "hydrochlorothiazide plus quinapril" or "hydrochlorothiazide plus ramipril" or idrapril or ilepatril or imidapril or imidaprilat or "indapamide plus perindopril" or indolapril or "kininase ii antagonist∗" or "kininase ii inhibitor∗" or libenzapril or Lisinopril or "lisinopril plus torasemdie" or moexipril or moexiprilat or omapatrilat or pentopril or pentoprilat or "peptidyl dipeptidase inhibitor∗" or "peptidyldipeptide hydrolase inhibitor∗" or Perindopril or perindoprilat or pivopril or Quinapril or quinaprilat or Ramipril or ramiprilat or rentiapril or "s nitrosocaptopril" or sampatrilat or spirapril or spiraprilat or temocapril or temocaprilat or Teprotide or trandolapril or "trandolapril plus verapamil" or trandolaprilat or utibapril or utibaprilat or "vasopeptidase inhibitor∗" or zabicipril or zabiciprilat or zofenopril or zofenoprilat).ti,ab,hw,kw. | 300,918 |

| 6 | exp Angiotensin II/ag [Agonists] | 31 |

| 7 | exp angiotensin 2 receptor antagonist/ | 7,877 |

| 8 | ("Angiotensin 2 agonist∗" or "Angiotensin 2 block∗" or "angiotensin 2 receptor agonist∗" or "angiotensin 2 receptor antagonist∗" or "angiotensin 2 receptor block∗" or "angiotensin AT2 agonist∗" or "angiotensin AT2 antagonist∗" or "angiotensin AT2 block∗" or "angiotensin AT2 receptor agonist∗" or "angiotensin AT2 receptor antagonist∗" or "angiotensin AT2 receptor block∗" or "Angiotensin II agonist∗" or "Angiotensin II block∗" or "angiotensin II type 2 receptor agonist∗" or "angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist∗" or "angiotensin II type 2 receptor block∗" or "AT2 agonist∗" or "AT2 antagonist∗" or "AT2 block∗" or "AT2 receptor agonist∗" or "AT2 receptor antagonist∗" or "AT2 receptor block∗" or Azilsartan or Candesartan or Eprosartan or Irbesartan or Losartan or Olmesartan or Telmisartan or Valsartan).ti,ab,hw,kw. | 96,387 |

| 9 | or/4-8 | 356,594 |

| 10 | 3 and 9 | 629 |

| 11 | (exp animals/ or exp nonhuman/) not exp humans/ | 11,678,555 |

| 12 | ((alpaca or alpacas or amphibian or amphibians or animal or animals or antelope or armadillo or armadillos or avian or baboon or baboons or beagle or beagles or bee or bees or bird or birds or bison or bovine or buffalo or buffaloes or buffalos or "c elegans" or "Caenorhabditis elegans" or camel or camels or canine or canines or carp or cats or cattle or chick or chicken or chickens or chicks or chimp or chimpanze or chimpanzees or chimps or cow or cows or "D melanogaster" or "dairy calf" or "dairy calves" or deer or dog or dogs or donkey or donkeys or drosophila or "Drosophila melanogaster" or duck or duckling or ducklings or ducks or equid or equids or equine or equines or feline or felines or ferret or ferrets or finch or finches or fish or flatworm or flatworms or fox or foxes or frog or frogs or "fruit flies" or "fruit fly" or "G mellonella" or "Galleria mellonella" or geese or gerbil or gerbils or goat or goats or goose or gorilla or gorillas or hamster or hamsters or hare or hares or heifer or heifers or horse or horses or insect or insects or jellyfish or kangaroo or kangaroos or kitten or kittens or lagomorph or lagomorphs or lamb or lambs or llama or llamas or macaque or macaques or macaw or macaws or marmoset or marmosets or mice or minipig or minipigs or mink or minks or monkey or monkeys or mouse or mule or mules or nematode or nematodes or octopus or octopuses or orangutan or "orang-utan" or orangutans or "orang-utans" or oxen or parrot or parrots or pig or pigeon or pigeons or piglet or piglets or pigs or porcine or primate or primates or quail or rabbit or rabbits or rat or rats or reptile or reptiles or rodent or rodents or ruminant or ruminants or salmon or sheep or shrimp or slug or slugs or swine or tamarin or tamarins or toad or toads or trout or urchin or urchins or vole or voles or waxworm or waxworms or worm or worms or xenopus or "zebra fish" or zebrafish) not (human or humans or patient or patients)).ti,ab,hw,kw. | 9,999,103 |

| 13 | 10 not (11 or 12) | 536 |

| 14 | limit 13 to (editorial or erratum or note or addresses or autobiography or bibliography or biography or blogs or comment or dictionary or directory or interactive tutorial or interview or lectures or legal cases or legislation or news or newspaper article or overall or patient education handout or periodical index or portraits or published erratum or video-audio media or webcasts) [Limit not valid in CCTR,CDSR,Embase,Ovid MEDLINE(R),Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily Update,Ovid MEDLINE(R) PubMed not MEDLINE,Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process,Ovid MEDLINE(R) Publisher; records were retained] | 12 |

| 15 | 13 not 14 | 524 |

| 16 | remove duplicates from 15 | 461 |

References

- Alexandrescu D., Fabi S., Yeh L.C., Fitzpatrick R.E., Goldman M.P. Comparative results in treatment of keloids with intralesional 5-FU/Kenalog, 5-FU/verapamil, enalapril alone,verapamil alone, and laser: a case report and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1442–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J.P., Marttala J., Macarak E., Rosenbloom J., Uitto J. Keloids: the paradigm of skin fibrosis - pathomechanisms and treatment. Matrix Biol. 2016;51:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardekani G.S., Aghaie S., Nemati M.H., Handjani F., Kasraee B. Treatment of a postburn keloid scar with topical captopril: report of the first case. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:112e–113e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819a34db. [published correction appears in Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123:1898] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R., Urso-Baiarda F., Linge C., Grobbelaar A. Cutaneous scarring: a clinical review. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/625376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet U., Blalock T.W. Keloids: a review of etiology, prevention, and treatment. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:33–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.C., McKenna S.P., Siddhi K., McGrouther D.A., Bayat A. The hidden cost of skin scars: quality of life after skin scarring. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demir C.Y., Ersoz M.E., Erten R., Kocak O.F., Sultanoglu Y., Basbugan Y. Comparison of enalapril, candesartan and intralesional triamcinolone in reducing hypertrophic scar development: an experimental study. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42:352–361. doi: 10.1007/s00266-018-1073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott C.G., Hamilton D.W. Deconstructing fibrosis research: do pro-fibrotic signals point the way for chronic dermal wound regeneration? J Cell Commun Signal. 2011;5:301–315. doi: 10.1007/s12079-011-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Q.Q., Wang X.F., Zhao W.Y., Ding S.L., Shi B.H., Xia Y., et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor reduces scar formation by inhibiting both canonical and noncanonical TGF-β1 pathways. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3332. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21600-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli A., Lio P.A., Liu V. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: are ACE inhibitors the missing link? Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1401. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.11.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearmonti R., Bond J., Erdmann D., Levinson H. A review of scar scales and scar measuring devices. EPlasty. 2010;10:e43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass D.A. Current understanding of the genetic causes of keloid formation. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S50–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedayatyanfard K., Haddadi N.S., Ziai S.A., Karim H., Niazi F., Steckelings U.M., et al. The renin-angiotensin system in cutaneous hypertrophic scar and keloid formation. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:902–909. doi: 10.1111/exd.14154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedayatyanfard K., Ziai S.A., Niazi F., Habibi I., Habibi B., Moravvej H. Losartan ointment relieves hypertrophic scars and keloid: a pilot study. Wound Repair Regen. 2018;26:340–343. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.Y., Fang Q.Q., Wang X.F., Zhao W.Y., Zheng B., Zhang D.D., et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker: potential agents to reduce post-surgical scar formation in humans. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2020;127:488–494. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannello S., Milazzo P., Bordonaro F., Belfiore F. Low-dose enalapril in the treatment of surgical cutaneous hypertrophic scar and keloid--two case reports and literature review. MedGenMed. 2006;8:60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor J. Reliability and photographic equivalency of the Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (Scar) scale, an outcome measure for postoperative scars. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:55–60. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassi K., Kouame K., Kouassi A., Allou A., Kouassi I., Kourouma S., et al. Quality of life in black African patients with keloid scars. Dermatol Reports. 2020;12:8312. doi: 10.4081/dr.2020.8312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.Y., Han Y.S., Kim S.R., Chun B.K., Park J.H. Effects of a topical angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a selective cox-2 inhibitor on the prevention of hypertrophic scarring in the skin of a rabbit ear. Wounds. 2012;24:356–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledon J.A., Savas J., Franca K., Chacon A., Nouri K. Intralesional treatment for keloids and hypertrophic scars: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1745–1757. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Ma K., Kwon S.H., Garg R., Patta Y.R., Fujiwara T., et al. The abnormal architecture of healed diabetic ulcers is the result of FAK degradation by calpain 1. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1155–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzano S.A., Ruiz-Ortega M., Egido J. Angiotensin II and renal fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38:635–638. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.094234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miteva M., Romanelli P., Kirsner R.S. Lipodermatosclerosis. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:375–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi A.A., Parand A., Kardeh S., Janati M., Mohammadi S. Efficacy of topical enalapril in treatment of hypertrophic scars. World J Plast Surg. 2018;7:326–331. doi: 10.29252/wjps.7.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PloS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy A., LeVatte T., Boudreau C., Midgen C., Gratzer P., Marshall J., et al. Angiotensin II type I receptor blockade is associated with decreased cutaneous scar formation in a rat model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:803e–813e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa R., Arima J., Ono S., Hyakusoku H. CASE REPORT total management of a severe case of systemic keloids associated with high blood pressure (hypertension): clinical symptoms of keloids may be aggravated by hypertension. Eplasty. 2013;13:e25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeh N., Bharatha A., Gaur U., Forde A.L. Keloids: current and emerging therapies. Scars Burn Heal. 2020;6 doi: 10.1177/2059513120940499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliaro P., Penna C. ACE/ACE2 Ratio: a Key Also in 2019 Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19)? Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:335. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K.E., Turner N.A. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rha E.Y., Kim J.W., Kim J.H., Yoo G. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, captopril, improves scar healing in hypertensive rats. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:975–983. doi: 10.7150/ijms.50197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom J., Macarak E., Piera-Velazquez S., Jimenez S.A. Human fibrotic diseases: current challenges in fibrosis research. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1627:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7113-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaee Ardekani G., Ebrahimi S., Amini M., Sari Aslani F., Handjani F., Ranjbar Omrani G., et al. Topical captopril as a novel agent against hypertrophic scar formation in New Zealand white rabbit skin. Wounds. 2008;20:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer J.J., Taylor S.C., Cook-Bolden F. Keloidal scars: a review with a critical look at therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S63–S97. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva I.M.S., Assersen K.B., Willadsen N.N., Jepsen J., Artuc M., Steckelings U.M. The role of the renin-angiotensin system in skin physiology and pathophysiology. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:891–901. doi: 10.1111/exd.14159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slemp A.E., Kirschner R.E. Keloids and scars: a review of keloids and scars, their pathogenesis, risk factors, and management. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:396–402. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000236389.41462.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobanko J.F., Sarwer D.B., Zvargulis Z., Miller C.J. Importance of physical appearance in patients with skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:183–188. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., Elbers R.G., Blencowe N.S., Boutron I., et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan T., Smith J., Kermode J., McIver E., Courtemanche D.J. Rating the burn scar. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1990;11:256–260. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan S., Migden M.R., Silapunt S. Stasis dermatitis: pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:383–390. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W.Q., Fang Q.Q., Shen X.Z., Giani J.F., Zhao T.V., Shi P., et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor works as a scar formation inhibitor by down-regulating Smad and TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (Tak1) pathways in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:4239–4252. doi: 10.1111/bph.14489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger T., Borghi C., Charchar F., Khan N.A., Poulter N.R., Prabhakaran D., et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–1357. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzun H., Bitik O., Hekimoğlu R., Atilla P., Kaykçoğlu A.U. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor enalapril reduces formation of hypertrophic scars in a rabbit ear wounding model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:361e–371e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829acf0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G.A., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Wynn T.A. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Fang Q.Q., Wang X.F., Shi B.H., Zhao W.Y., Chen C.Y., et al. The effect of topical ramipril and losartan cream in inhibiting scar formation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No large datasets were generated or analyzed during this study. Minimal datasets necessary to interpret and/or replicate data in this paper are available upon request to the corresponding author.