Abstract

Aims

Many historical and recent reports showed that post-infarction ventricular septal rupture (VSR) represents a life-threatening condition and the strategy to optimally manage it remains undefined. Therefore, disparate treatment policies among different centres with variable results are often described. We analysed data from European centres to capture the current clinical practice in VSR management.

Methods and results

Thirty-nine centres belonging to eight European countries participated in a survey, filling a digital form of 38 questions from April to October 2022, to collect information about all the aspects of VSR treatment. Most centres encounter 1–5 VSR cases/year. Surgery remains the treatment of choice over percutaneous closure (71.8% vs. 28.2%). A delayed repair represents the preferred approach (87.2%). Haemodynamic conditions influence the management in almost all centres, although some try to achieve patients stabilization and delayed surgery even in cardiogenic shock. Although 33.3% of centres do not perform coronarography in unstable patients, revascularization approaches are widely variable. Most centres adopt mechanical circulatory support (MCS), mostly extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, especially pre-operatively to stabilize patients and achieve delayed repair. Post-operatively, such MCS are more often adopted in patients with ventricular dysfunction.

Conclusion

In real-life, delayed surgery, regardless of the haemodynamic conditions, is the preferred strategy for VSR management in Europe. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is becoming the most frequently adopted MCS as bridge-to-operation. This survey provides a useful background to develop dedicated, prospective studies to strengthen the current evidence on VSR treatment and to help improving its currently unsatisfactory outcomes.

Keywords: Ventricular septal rupture, Acute myocardial infarction, Mechanical complication, Mechanical circulatory support, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, Cardiogenic shock

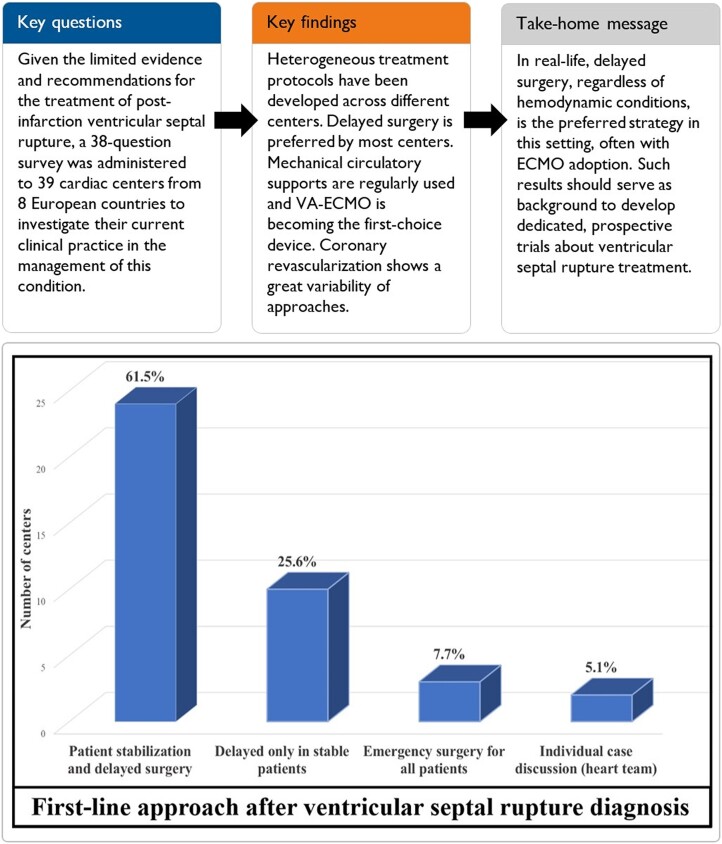

Graphical Abstract

Graphical abstract.

First-line approach for management of post-acute myocardial infarction ventricular septal rupture according to interviewed centres.

Introduction

Ventricular septal rupture (VSR) represents a life-threatening complication occurring in about 0.5% of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) cases.1 Even with prompt treatment, either surgical or percutaneous, it is characterized by an in-hospital mortality approaching 40%, which is even higher in patients presenting with cardiogenic shock (CS).1,2

Given its low incidence and high mortality, evidence about VSR treatment is limited to small, single-centre experiences or national registries, probably justifying the weak and, sometimes, controversial recommendations provided by the current guidelines.2–5 The Mechanical Complications of Acute Myocardial Infarction: an International Multicenter Cohort (CAUTION) study has provided further insights about VSR.6 Nevertheless, such limits have led to highly heterogeneous management protocols across different centres, especially concerning the timing of repair and possible adoption of mechanical circulatory support (MCS).7,8

We sought to investigate the modern clinical practice about VSR management by running a survey across European centres.

Methods

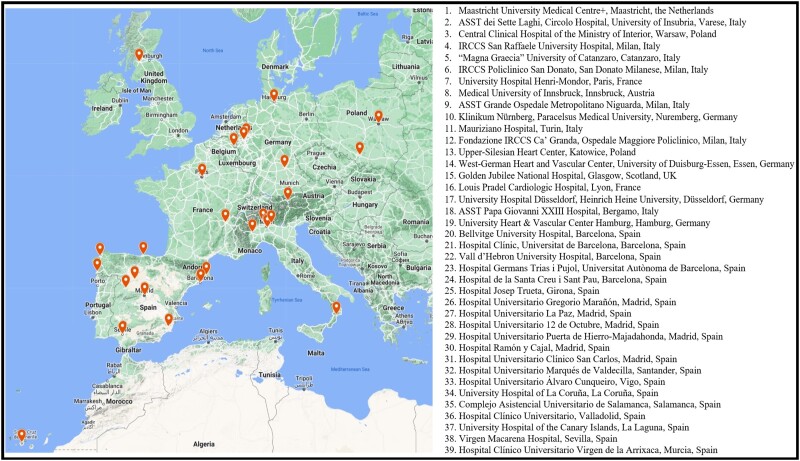

From April to October 2022, we invited 46 cardiac centres to conduct a descriptive survey on their clinical practice for post-infarction VSR management. Centres were identified from the CAUTION database and extended to a large group of Spanish centres coordinated by A.A.S. Thirty-nine (84.8%) centres from 8 countries responded (Figure 1). Thirty-eight questions have been administered through a web form, automatically collecting the replies regarding general information about the centres, and any aspect of their current treatment protocols for VSR. Questions referred to all patients aged >18 years admitted with a post-AMI VSR diagnosis, independently from the treatment provided. Moreover, we sought to investigate the willingness of each centre to participate to a prospective trial, addressing key, controversial aspects of VSR management.

Figure 1.

Distribution of European centres participating to the survey.

Given the nature of the survey and the lack of individual patient data, neither ethical committee approval nor patient informed consent was required.

Results

The answers were 100% complete from all centres. Most centres were Spanish (51.3%) and Italian (20.5%). Table 1 enlists the main questions of the survey. Although most involved centres had large patients referral, the vast majority steadily managed 1–5 VSR cases/year. The shock team was involved in 41.0% of centres.

Table 1.

Main questions about the management of ventricular septal rupture patients

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| General management | |

| How many cases do you usually encounter per year? | |

|

28 (71.8%) |

|

9 (23.1%) |

|

2 (5.1%) |

| What is your opinion about the trend of incidence in the last years? | |

|

10 (25.6%) |

|

23 (59.0%) |

|

6 (15.4%) |

| Do you always involve the Shock Team? | |

|

16 (41.0%) |

|

10 (25.6%) |

|

13 (33.3%) |

| If the patient is awake, where do you hospitalize him/her? | |

|

19 (48.7%) |

|

19 (48.7%) |

|

1 (2.6%) |

| Which is your approach for a patient with VSR diagnosis? | |

|

24 (61.5%) |

|

10 (25.6%) |

|

3 (7.7%) |

|

2 (5.1%) |

| Which is the first-line treatment you offer to VSR patients? | |

|

28 (71.8%) |

|

7 (17.9%) |

|

4 (10.3%) |

| In case of delayed surgery, which is the timing by which you operate? | |

|

9 (23.1%) |

|

12 (30.8%) |

|

6 (15.4%) |

|

2 (5.1%) |

|

3 (7.7%) |

|

5 (12.8%) |

|

2 (5.1%) |

| Which do you think is the ideal timing for surgery? | |

|

28 (71.8%) |

|

7 (17.9%) |

|

4 (10.3%) |

| Do you perform coronary angiography in all patients? | |

|

26 (66.7%) |

|

13 (33.3%) |

| Patients subgroups | |

| Does haemodynamic stability impact on the timing of surgery? | |

|

33 (84.6%) |

|

6 (15.4%) |

| Which is your preferred approach for stable patients? | |

|

19 (48.7%) |

|

16 (41.0%) |

|

1 (2.6%) |

|

3 (7.7%) |

| Which is your preferred approach for patients with impending haemodynamic instability? | |

|

26 (66.7%) |

|

9 (23.1%) |

|

3 (7.7%) |

|

1 (2.6%) |

| Which is your preferred approach for patients with cardiogenic shock? | |

|

29 (74.4%) |

|

6 (15.4%) |

|

4 (10.3%) |

| Pre-operative MCS | |

| Do you routinely use IABP? | |

|

26 (66.7%) |

|

7 (17.9%) |

|

5 (12.8%) |

|

1 (2.6%) |

| Do you routinely adopt other MCS devices? | |

|

19 (48.7%) |

|

20 (51.3%) |

| Do you routinely adopt MCS devices as bridge to surgery? | |

|

28 (71.8%) |

|

11 (28.2%) |

| For which patients? | |

|

9 (23.1%) |

|

21 (53.8%) |

|

9 (23.1%) |

| Which is your first aim of pre-operative MCS?a | |

|

34 (87.2%) |

|

17 (43.6%) |

|

13 (33.3%) |

| Do you prefer some MCS combination? | |

|

34 (87.2%) |

|

5 (12.8%) |

| Which type of MCS combination do you adopt preferentially? | |

|

21 (53.8%) |

|

11 (28.2%) |

|

7 (17.9%) |

| During MCS support, which is the general setting you routinely choose? | |

|

23 (59.0%) |

|

15 (38.4%) |

|

1 (2.6%) |

| Which is your preferred approach for VA-ECMO implantation? | |

|

26 (66.7%) |

|

13 (33.3%) |

| For Impella, which is your preferred device? | |

|

24 (61.5%) |

|

4 (10.3%) |

|

6 (15.4%) |

|

1 (2.6%) |

|

4 (10.3%) |

| Post-operative MCS | |

| Do you generally adopt MC post-operatively? | |

|

26 (66.7%) |

|

13 (33.3%) |

| Which is your indication?a | |

|

15 (38.5%) |

|

15 (38.5%) |

|

25 (64.1%) |

| Do you consider inappropriate the routine adoption of post-operative MCS as prophylactic support? | |

|

12 (30.8%) |

|

27 (69.2%) |

| How long should MCS be continued? | |

|

20 (51.3%) |

|

13 (33.3%) |

|

6 (15.4%) |

| Do you sometimes consider selective right ventricular support? | |

|

19 (48.7%) |

|

20 (51.3%) |

More than one answer allowed.

CCU, coronary care unit; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; VA-ECMO, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VSR, ventricular septal rupture.

Once admitted, patients were almost equally transferred either into intensive care or coronary care units. As a general policy, most centres preferred an initial patient stabilization followed by delayed surgery (61.5%). In >70% of centres, surgery represented the first-line treatment for all patients, although the remaining considered percutaneous closure, when feasible. The timing of surgery was widely variable, although most centres agreed that a 7–10-day delay to schedule VSR repair would be ideal.

In most centres, haemodynamic stability impacted on timing of surgery. Indeed, while stable patients underwent delayed surgery in almost all centres, in subjects presenting with impending haemodynamic instability, still two-thirds of centres generally instituted MCS to reach patients stabilization and delay surgery anyway. Moreover, even with CS, almost 75% of centres preferred a first attempt of MCS to revert CS and reach delayed repair.

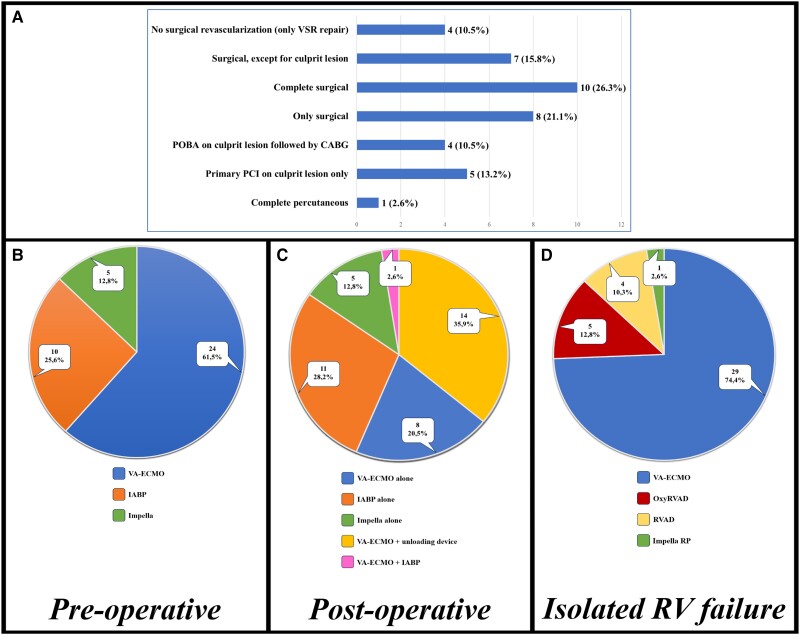

Coronarography was performed routinely in two-thirds of the centres, regardless of haemodynamic conditions. Figure 2A shows the widely variable preferences concerning coronary revascularization in this setting.

Figure 2.

(A) Preferred approach for coronary revascularization. (B) Pre-operative MCS of choice. (C) Post-operative MCS of choice. (D) MCS for isolated right ventricular failure. Numbers and percentages of interviewed centres are presented. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; POBA, plain old balloon angioplasty; RVAD, right ventricular assist device; VA-ECMO, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; VSR, ventricular septal rupture; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump.

Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was routinely adopted before intervention in two-thirds of centres. Moreover, most centres regularly used other MCS devices as a bridge to surgery, although >50% of them only in case of impending haemodynamic instability. The rationale of pre-operative MCS were shared by most centres, especially concerning haemodynamic stabilization and recovery from CS. Figure 2B shows the preferences of pre-operative MCS devices, with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) representing the most diffused one.

Post-operative VSR management showed a wider variability of protocols, starting from the routine adoption of MCS, considered inappropriate by almost one-third of centres, if not necessarily due to failed cardiopulmonary bypass weaning. Figure 2C shows the preferences of post-operative MCS devices. Selective right ventricular MCS in case of need was chosen in about half of centres; the preferred devices are shown in Figure 2D.

All centres declared their interest for a prospective randomized controlled trial aimed at evaluating pre-operative VSR management, albeit with some distinctions in patients’ inclusion criteria.

Discussion

The low incidence and high mortality of post-AMI VSR have limited the possibilities to develop dedicated trials, reducing the evidence to single-centre experiences or national registries.1,2 This was mirrored by the weak recommendations provided by the current guidelines.4,5 Recent data provided insights about the preferential choice of delayed VSR repair, whenever possible, the adoption of various MCS devices, pre- and post-operatively, and the role of percutaneous closure as an alternative strategy, as shown in the recent American Heart Association statement on the management of post-AMI mechanical complications and UK national registry.2,3,6–9 The CAUTION study has contributed to increase the evidence on the surgical treatment of VSR, by analysing 475 patients collected from >25 centres worldwide, albeit with the limits of retrospective studies.6

Due to the weak recommendations available, most centres have developed updated, dedicated protocols to manage these patients. The present survey represents a further step to investigate VSR, capturing the real-life clinical practice and providing useful insights on how it is treated nowadays in most European centres, involving cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, and intensivists.

Almost all the centres declared to prefer a delayed treatment, supporting the advantages of such planning over emergent surgery, almost unanimously described by the recent literature.2,4,6,9 The different types of presentation deserve great consideration, since most patients are admitted in labile haemodynamic conditions or in CS and a risk profile-based approach could be advisable.1,2,6 Nevertheless, some centres still try to achieve patient stabilization and delayed repair, possibly with MCS adoption, even in most critical subjects.7,8

Although evidence is currently lacking to support such wide pre-operative adoption of advanced MCS other than IABP, as in the current survey, progressively more reports showed the central role of MCS to achieve haemodynamic stabilization or prevent deterioration in such a delicate setting, partially justifying their growing adoption.4,5,7–9 Thus, it seems reasonable that large European centres who are confident with certain supports developed updated protocols including MCS (especially ECMO) in VSR management. However, it is also important to balance the advantages of MCS utilization to temporize surgery and the potential MCS-related complications that have also been described.8 Differently, relatively few centres systematically adopt MCS post-operatively. However, it should be noted that most in-hospital deaths in VSR are due to low cardiac output syndrome, and this may represent a rationale to promote an MCS-based protected peri-operative course, at least in more delicate patients.6–8

Although VSR is traditionally considered a surgical-only condition, percutaneous closure is gaining credits, both for patients deemed inoperable and as first choice in technically feasible cases.3,9 The UK national registry has recently shown for percutaneous VSR closure results sometimes comparable to surgery in selected patients.3,9 However, data are still limited in this regard, and further investigations are advised to identify the ideal conditions for the percutaneous approach. Unfortunately, we could not retrieve information about whether all centres of this survey have availability to perform percutaneous VSR closure.

Despite the shock team has been shown to be important in this setting, <50% of centres involve such organization, probably because the limited number of VSR cases/year might underscore the importance of structured, multidisciplinary treatment pathways for these patients.9

It is also interesting to notice that one-third of centres do not perform coronarography unless patients are haemodynamically stable.10 This approach inevitably impacts the possibility of planning revascularization in this AMI-related complication and analysing its potential impact on early and late survival.10 Nevertheless, the revascularization approaches widely vary across the centres.

Given the current evidence and heterogeneous, real-life management of this condition, the present survey represents a first step towards a more comprehensive understanding of applied strategies in post-AMI VSR treatment.4,5,9 Its relevance also relies on the number and extension of participating centres.

Finally, this survey may serve as a useful background to develop prospective studies, taking into consideration the most advanced technologies available nowadays, possibly contributing to strengthen evidence and improve the still unacceptably unfavourable outcomes of VSR.

Limitations

This survey presents the limitations of retrospective data collection. Relying on self-reporting and collecting generalized information from each centre, the results may not represent the exact procedures applied to all patients, but rather provide a hint of their preferred approach. Although involving 39 European centres provided useful insights on the current VSR treatment, the uneven centres distribution (mostly from Spain and Italy) limits the generalizability of the results. Moreover, most centres manage 1–5 VSR cases/year, thereby limiting the validity and efficacy testing of management protocols. Therefore, the current results should be only considered as hypothesis-generating, despite providing a relevant report about real-life VSR management across Europe.

Conclusions

The present survey shows an updated picture of the heterogeneous clinical practice characterizing post-AMI VSR management among 39 European centres. Such data provide interesting insights about the ongoing adoption of advanced technologies and treatment protocols to optimize the outcomes of VSR, independently from the current guidelines recommendations, which still rely on outdated data and weak evidence. This study represents a useful background to develop dedicated, prospective studies to better understand the most effective management options for VSR patients, to possibly support an update in the international recommendations, and hopefully improve the currently unsatisfactory survival.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following collaborators who have contributed to the completion of the survey as follows: Marta Alonso Fernández de Gatta; Eduardo Armada Romero; Massimiliano Carrozzini; Juan Caro Codón; Marisa Crespo Leiro; José J. Cuenca Castillo; Marek A. Deja; Juan Manuel Escudier-Villa; Carlos Ferrera Durán; Carlo Francesco Fino; Martin J. García González; Federica Jiritano; Francisco Javier Noriega; Sandra O. Rosillo Rodríguez; Piotr Suwalski; and Cinzia Trumello.

Contributor Information

Daniele Ronco, Congenital Cardiac Surgery Department, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, San Donato Milanese, Italy; Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart and Vascular Centre, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Thoracic Research Centre, Collegium Medicum Nicolaus Copernicus University, Innovative Medical Forum, Bydgoszcz, Poland.

Albert Ariza-Solé, Cardiology Department, Bellvitge University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain.

Mariusz Kowalewski, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart and Vascular Centre, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Thoracic Research Centre, Collegium Medicum Nicolaus Copernicus University, Innovative Medical Forum, Bydgoszcz, Poland; Department of Cardiac Surgery and Transplantology, Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Interior, Centre of Postgraduate Medical Education, Warsaw, Poland.

Matteo Matteucci, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart and Vascular Centre, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Thoracic Research Centre, Collegium Medicum Nicolaus Copernicus University, Innovative Medical Forum, Bydgoszcz, Poland; Cardiac Surgery Unit, ASST dei Sette Laghi, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy.

Michele Di Mauro, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart and Vascular Centre, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Esteban López-de-Sá, Department of Cardiology, IDIPAZ, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain.

Marco Ranucci, Department of Cardiovascular Anesthesia and Intensive Care, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, San Donato Milanese, Italy.

Alessandro Sionis, Intensive Cardiac Care Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Biomedical Research Institute Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

Nikolaos Bonaros, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria.

Michele De Bonis, Department of Cardiac Surgery, San Raffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy.

Claudio Francesco Russo, Cardiac Surgery Unit, Cardio-Thoraco-Vascular Department, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy.

Aitor Uribarri, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain; Department of Cardiology, Instituto de Ciencias del Corazón (ICICOR), Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain.

Santiago Montero, Acute Cardiovascular Care Unit, Cardiology, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain.

Theodor Fischlein, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Cardiovascular Center, Klinikum Nürnberg, Paracelsus Medical University, Nuremberg, Germany.

Adam Kowalówka, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Medical University of Silesia, School of Medicine in Katowice, Katowice, Poland.

Shiho Naito, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, University Heart & Vascular Center Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Jean-François Obadia, Department of Cardiac Surgery, Louis Pradel Cardiologic Hospital, Lyon, France.

Roberto Martín-Asenjo, Intensive Cardiac Care Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain.

Jaime Aboal, Cardiology Department, Hospital Josep Trueta, Girona, Spain.

Matthias Thielmann, Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, West-German Heart and Vascular Center Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, Germany.

Caterina Simon, Cardiovascular and Transplant Department, Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital, Bergamo, Italy.

Rut Andrea-Riba, Acute Cardiac Care Unit, Cardiology Department, Hospital Clínic, IDIBAPS, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Carolina Parra, Cardiology Department, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain.

Thierry Folliguet, Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, University Hospital Henri-Mondor, Assistance Publique–Hopitaux de Paris Créteil, Paris, France.

Manuel Martínez-Sellés, Department of Cardiology, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon, CIBERCV, and Universidad Europea, Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain.

Marcelo Sanmartín Fernández, Cardiology Department, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain.

Nawwar Al-Attar, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Glasgow, UK.

Ana Viana Tejedor, Department of Cardiology, Instituto Cardiovascular, Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain.

Giuseppe Filiberto Serraino, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, ‘Magna Graecia’ University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy.

Virginia Burgos Palacios, Department of Cardiology, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain.

Udo Boeken, Department of Cardiac Surgery, University Hospital Düsseldorf, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany.

Sergio Raposeiras Roubin, Department of Cardiology, Hospital Universitario Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo, Spain.

Miguel Antonio Solla Buceta, Cardiac Intensive Care Unit, University Hospital of La Coruña, La Coruña, Spain.

Pedro Luis Sánchez Fernández, Department of Cardiology, Complejo Asistencial Universitario Salamanca, CIBER-CV, IBSAL, Salamanca, Spain.

Roberto Scrofani, Cardiac Surgery Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy.

Gemma Pastor Báez, Department of Cardiology, Instituto de Ciencias del Corazón (ICICOR), Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain.

Pablo Jorge Pérez, Cardiology Unit, University Hospital of the Canary Islands, La Laguna, Spain.

Guglielmo Actis Dato, Cardiac Surgery Department, Mauriziano Hospital, Turin, Italy.

Juan Carlos Garcia-Rubira, Department of Cardiology, Virgen Macarena Hospital, Sevilla, Spain.

Jose H de Gea Garcia, Coronary Care Unit, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia, Spain.

Giulio Massimi, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart and Vascular Centre, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Thoracic Research Centre, Collegium Medicum Nicolaus Copernicus University, Innovative Medical Forum, Bydgoszcz, Poland.

Andrea Musazzi, Cardiac Surgery Unit, ASST dei Sette Laghi, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy.

Roberto Lorusso, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Heart and Vascular Centre, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Cardiovascular Research Institute Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Lead author biography

Daniele Ronco is a cardiac surgeon at the Congenital Cardiac Surgery Unit, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Milan. He is also PhD fellow at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Centre+, Maastricht, working in the research group of Prof. Dr Roberto Lorusso, focusing on post-acute myocardial infarction mechanical complications, and specifically on ventricular septal rupture. He is also member of the Thoracic Research Centre, headed in Poland, of the Italian Society for Cardiac Surgery, of the ESC Working Group on Cardiovascular Surgery, and is founding member of the INTEGRITTY (International Evidence Grading Initiative Towards Transparency and Quality) group.

Daniele Ronco is a cardiac surgeon at the Congenital Cardiac Surgery Unit, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, Milan. He is also PhD fellow at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Centre+, Maastricht, working in the research group of Prof. Dr Roberto Lorusso, focusing on post-acute myocardial infarction mechanical complications, and specifically on ventricular septal rupture. He is also member of the Thoracic Research Centre, headed in Poland, of the Italian Society for Cardiac Surgery, of the ESC Working Group on Cardiovascular Surgery, and is founding member of the INTEGRITTY (International Evidence Grading Initiative Towards Transparency and Quality) group.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article.

Funding

No funding was provided for the current study.

References

- 1. Matteucci M, Ronco D, Corazzari C, Fina D, Jiritano F, Meani P, Kowalewski M, Beghi C, Lorusso R. Surgical repair of postinfarction ventricular septal rupture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2021;112:326–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnaoutakis GJ, Zhao Y, George TJ, Sciortino CM, McCarthy PM, Conte JV. Surgical repair of ventricular septal defect after myocardial infarction: outcomes from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:436–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giblett JP, Matetic A, Jenkins D, Ng CY, Venuraju S, MacCarthy T, Vibhishanan J, O'Neill JP, Kirmani BH, Pullan DM, Stables RH, Andrews J, Buttinger N, Kim WC, Kanyal R, Butler MA, Butler R, George S, Khurana A, Crossland DS, Marczak J, Smith WHT, Thomson JDR, Bentham JR, Clapp BR, Buch M, Hayes N, Byrne J, MacCarthy P, Aggarwal SK, Shapiro LM, Turner MS, de Giovanni J, Northridge DB, Hildick-Smith D, Mamas MA, Calvert PA. Post-infarction ventricular septal defect: percutaneous or surgical management in the UK national registry. Eur Heart J 2022;43:5020–5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:e78–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ronco D, Matteucci M, Kowalewski M, De Bonis M, Formica F, Jiritano F, Fina D, Folliguet T, Bonaros N, Russo CF, Sponga S, Vendramin I, De Vincentiis C, Ranucci M, Suwalski P, Falcetta G, Fischlein T, Troise G, Villa E, Dato GA, Carrozzini M, Serraino GF, Shah SH, Scrofani R, Fiore A, Kalisnik JM, D'Alessandro S, Lodo V, Kowalówka AR, Deja MA, Almobayedh S, Massimi G, Thielmann M, Meyns B, Khouqeer FA, Al-Attar N, Pozzi M, Obadia JF, Boeken U, Kalampokas N, Fino C, Simon C, Naito S, Beghi C, Lorusso R. Surgical treatment of postinfarction ventricular septal rupture. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2128309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ariza-Solé A, Sánchez-Salado JC, Sbraga F, Ortiz D, González-Costello J, Blasco-Lucas A, Alegre O, Toral D, Lorente V, Santafosta E, Toscano J, Izquierdo A, Miralles A, Cequier Á. The role of perioperative cardiorespiratory support in post infarction ventricular septal rupture-related cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020;9:128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ronco D, Matteucci M, Ravaux JM, Marra S, Torchio F, Corazzari C, Massimi G, Beghi C, Maessen J, Lorusso R. Mechanical circulatory support as a bridge to definitive treatment in post-infarction ventricular septal rupture. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:1053–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Damluji AA, Van Diepen S, Katz JN, Menon V, Tamis-Holland JE, Bakitas M, Cohen MG, Balsam LB, Chikwe J; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing . Mechanical complications of acute myocardial infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144:e16–e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ronco D, Corazzari C, Matteucci M, Massimi G, Di Mauro M, Ravaux JM, Beghi C, Lorusso R. Effects of concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting on early and late mortality in the treatment of post-infarction mechanical complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2022;11:210–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article.