Summary

Undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P) is an essential lipid carrier that ferries cell wall intermediates across the cytoplasmic membrane in bacteria. Und-P is generated by dephosphorylating undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (Und-PP). In Escherichia coli, BacA, PgpB, YbjG, and LpxT dephosphorylate Und-PP and are conditionally essential. To identify vulnerabilities that arise when Und-P metabolism is defective, we developed a genetic screen for synthetic interactions which, in combination with ΔybjG ΔlpxT ΔbacA, are lethal or reduce fitness. The screen uncovered novel connections to cell division, DNA replication/repair, signal transduction, and glutathione metabolism. Further analysis revealed several new morphogenes; loss of one of these, qseC, caused cells to enlarge and lyse. QseC is the sensor kinase component of the QseBC two-component system. Loss of QseC causes overactivation of the QseB response regulator by PmrB cross-phosphorylation. Here, we show that deleting qseB completely reverses the shape defect of ΔqseC cells, as does overexpressing rprA (a small RNA). Surprisingly, deleting pmrB only partially suppressed qseC-related shape defects. Thus, QseB is activated by multiple factors in QseC’s absence and prior functions ascribed to QseBC may originate from cell wall defects. Altogether, our findings provide a framework for identifying new determinants of cell integrity that could be targeted in future therapies.

Keywords: BacA, bactoprenol, lysis, morphology, peptidoglycan, QseC

Graphical Abstract

“Bacteria are protected by sugary layers that resist antimicrobials and the immune system. These layers are produced from precursors assembled on undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P), an essential lipid carrier. Here, we report pathways required to maintain cell integrity when Und-P metabolism is compromised.”

Introduction

Most glycan layers that surround and protect bacteria are assembled from monomers linked to a polyisoprene lipid carrier (Manat et al., 2014); for the majority of bacteria, this is undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P), a 55-carbon isoprene commonly referred to as bactoprenol. Und-P is essential by virtue of its requirement to synthesize a stress-bearing structure known as the peptidoglycan (PG) sacculus (Kato et al., 1999, Bouhss et al., 2008, Manat et al., 2014), a net-like macromolecule that surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane and shapes bacteria (Vollmer et al., 2008, Typas et al., 2011). Nucleotide activated precursors UDP-N-acetylglucosamine and UDP-N-acetylmuramyl pentapeptide are synthesized in the cytoplasm and are assembled on Und-P to form the PG precursor lipid II (Egan et al., 2020). Lipid II is then translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane by a flippase (Sham et al., 2014, Meeske et al., 2015) and polymerized by PG glycosyltransferases into glycan chains, which are then cross-linked by PG transpeptidases (Egan et al., 2020). The cellular pool of Und-P is generated from the dephosphorylation of Und-PP (undecaprenyl pyrophosphate) to Und-P by integral membrane pyrophosphatases. The BacA and PAP2 protein families produce the monophosphate linkage from Und-PP synthesized in the cytoplasm via the non-mevalonate pathway (Hunter, 2007, Manat et al., 2014) or from Und-PP released on the outer side of the cytoplasmic membrane during glycan polymerization (El Ghachi et al., 2004, El Ghachi et al., 2005). In the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, BacA provides the majority of phosphatase activity (El Ghachi et al., 2004), with smaller contributions provided by the PAP2 enzymes PgpB, YbjG, and LpxT (formerly YeiU) (El Ghachi et al., 2005).

Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that ongoing Und-PP dephosphorylation is essential to maintain a sufficient supply of Und-P acceptor molecules to properly expand the PG sacculus without fatal breaches. For example, depleting BacA from an E. coli mutant lacking YbjG and PgpB causes cells to lyse (El Ghachi et al., 2005). Similarly, depleting BcrC (a PAP2 enzyme) from a Bacillus subtilis mutant lacking BacA induces cells to grow with gross morphological distortions and, in some cases, lyse (Zhao et al., 2016). Simultaneous inactivation of LpxE and HupA (PAP2 enzymes) in Helicobacter pylori is also lethal (Gasiorowski et al., 2019). Finally, treating cells (particularly Gram-positive bacteria) with bacitracin, which interferes with Und-PP dephosphorylation through competitive inhibition, is also lethal (Smith & Weinberg, 1962). Disrupting Und-PP synthesis or Und-P-utilizing pathways has the same net effect as inhibiting Und-PP dephosphorylation. Mutants harboring temperature sensitive alleles of the Und-PP synthase UppS grow misshapen and lyse (Kato et al., 1999, MacCain et al., 2018), as do mutants that trap Und-P in dead-end intermediates (Bhavsar et al., 2001, Cuthbertson et al., 2005, Tatar et al., 2007, Jorgenson et al., 2016, Jorgenson & Young, 2016, Elhenawy et al., 2016).

While E. coli cells can normally tolerate reductions in Und-PP phosphatase activity (El Ghachi et al., 2004), low Und-P levels provoke strong negative (i.e., deleterious) interactions in combination with PG synthase inhibitors. For example, E. coli cells induced to grow with low Und-P readily lyse in media containing aztreonam or mecillinam, β-lactam antibiotics that inhibit the PG synthesizing activity of penicillin binding proteins (PBPs) (Jorgenson et al., 2019). Similarly, deleting pgpB sensitizes cells to cefsulodin, another β-lactam antibiotic (Hernandez-Rocamora et al., 2018). β-lactam antibiotics also synergize with the UppS inhibitor (and fertility drug) clomiphene to kill methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Farha et al., 2015). Finally, low Und-P levels sensitize B. subtilis cells to cell wall targeting antibiotics (Lee & Helmann, 2013, Czarny et al., 2014, Peters et al., 2016). Apart from these findings, though, little is known about the connection between Und-P and other metabolic pathways. This is due, in part, because most bacteria harbor multiple Und-PP phosphatases. Thus, large-scale genetic interaction studies have likely missed relationships between Und-P metabolism and other pathways due to functional overlap. We therefore conducted a genetic screen to reproduce known Und-P synthetic interactions and to identify new interactions in an E. coli mutant lacking multiple Und-PP phosphatases. As expected, the screen identified pathways that directly affect Und-PP dephosphorylation but also pathways with no prior connection to Und-P metabolism. These included cell division, DNA replication, signal transduction, and glutathione metabolism. Importantly, some of these connections may prove useful starting points toward developing new combination therapies. The results from the screen also suggest that mutations that decrease surface area to volume (i.e., grow bigger) could compensate for defects in Und-P(P) metabolism when demand for cell wall expansion is high. An unexpected finding from the screen was the identification of envZ, gor, ompR, and qseC as novel morphogenes (i.e., genes required to maintain normal cell shape). Further characterization of qseC suggests that phenotypes related to this gene likely result from PG defects.

Results

The Δ3PP screen.

To identify Und-P synthetic interactions, we designed a screen based on pTB25 (Figure 1A), a derivative of the unstable mini-F plasmid that carries β-galactosidase (lacZ) (Bernhardt & de Boer, 2004). In strains that lack the lac operon, LacZ produced from pTB25 hydrolyzes X-Gal to form a blue pigment that results in blue colonies on agar plates. Conversely, plasmid-free cells cannot degrade X-Gal and produce white colonies. The plasmid pMAJ95 [Plac::bacA lacZYA] is a derivative of pTB25 that expresses lacZ and the Und-PP phosphatase bacA under the control of the lac promoter (Plac). Hereafter, pMAJ95 is referred to as pbacA. In MAJ815, an E. coli strain lacking three Und-PP phosphatases (LpxT, YbjG, and BacA; Δ3PP) and the lac operon, pbacA is readily lost (because PgpB is still active) as evidenced by the formation of equally sized solid-white and sectored-blue colonies on LB agar containing IPTG and X-Gal (LB-IX) (Figure 1B). Δ3PP cells rely on PgpB for Und-PP phosphatase activity, and a mutant combination lacking all four Und-PP phosphatases (Δ4PP) is not viable (El Ghachi et al., 2005). Indeed, we could only construct Δ4PP cells in the presence of pbacA, whose colonies grew solid-blue when plated on LB-IX agar (Figure 1B). This confirms that bacA is required for growth in this background.

Figure 1. Strategy to screen for Δ3PP synthetic interactions.

(A) Δ3PP screen workflow. E. coli cells lacking three Und-PP phosphatases (ΔlpxT ΔybjG ΔbacA) and the lac operon (Lac -) harbor pbacA (i.e., pMAJ95), a derivative of the unstable mini-F plasmid expressing the lac operon and bacA in the presence of IPTG. pbacA is readily lost in this background and cells form white or sectored-blue colonies on media containing X-gal. Conversely, introducing synthetically sick or lethal mutant combinations (i.e., λ1098) leads to the retention of pbacA and formation of blue colonies on media containing X-gal. (B) Images depicting white colonies and sectored-blue colonies (left panel) or solid-blue colonies (right panel). The strains tested were MAJ876 (Δ3PP [parent]) and MAJ974 (Δ3PP ΔpgpB).

We next mutagenized MAJ815/pbacA by infecting with λ1098 (Way et al., 1984), a λ phage that contains a tetracycline-resistant derivative of Tn10 (mini-Tn10), using a standard λ hop procedure (Way et al., 1984). The mutagenesis yielded approximately 5 × 104 tetracycline resistant mutants that were screened for solid-blue colony formation on LB-IX agar. Since demand for Und-P increases with higher temperature (MacCain et al., 2018), we reasoned we might obtain different mutations by plating at different temperatures. Thus, we screened the mutant library at 30°C (~151,000 colonies), 37°C (~70,000 colonies), and 42°C (~83,000 colonies) for solid-blue colony formation. From these, we identified 37 blue colonies that were purified on LB-IX agar. We tested every mutant for solid-blue colony formation at 30°C, 37°C, and 42°C. Upon further characterization, only one of these mutants gave rise to solid-blue colonies on LB-IX agar at every temperature, whose insertion was later mapped to pgpB (Table 1). Unexpectedly, for the remaining mutants, we observed the formation of unequally sized solid-blue and solid-white colonies, which we later confirmed (see below). In each case, the blue colonies were significantly larger than the white colonies, and the difference in size between the two became more apparent at higher temperatures. These results demonstrate that ongoing Und-PP phosphatase activity is an important fitness factor.

Table 1.

E. coli genes identified as synthetically sick or lethal in combination with ΔlpxT ΔbacA ΔybjG

| Gene name or region | No. of inserts | Location | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall biogenesis | |||

| dacA | 1 | IM | PG, D,D-carboxypeptidase |

| ldcA | 1 | C | PG L,D-carboxypeptidase |

| mltG | 1 | IM | PG lytic transglycosylase |

| PmreB | 1 | C-IM | Cytoskeletal protein |

| mrcB* | 1 | IM | PG bifunctional synthase |

| pgpB* | 1 | IM | Und-PP phosphatase |

| pal | 2 | OM | PG associated OM lipoprotein |

| tolA | 1 | IM | Cell envelope integrity IM protein |

| tolB | 1 | PS | Cell envelope integrity protein |

| Cell division | |||

| ftsK | 1 | IM | Cell division DNA translocase |

| minD | 1 | C-IM | FtsZ ring positioning protein |

| TminE | 1 | C-IM | FtsZ ring positioning protein |

| Disulfide bond formation | |||

| gor, Pgor | 2 | C | Glutathione reductase |

| ECA synthesis | |||

| wecD | 1 | C | dTDP-fucosamine acetyltransferase |

| wecE | 1 | C | dTDP-4-dehydro-6-deoxy-D-glucose transaminase |

| wzxE | 4 | IM | ECA lipid III flippase |

| Replication and Repair | |||

| rep | 1 | C | DNA helicase |

| seqA | 1 | C | Negative regulator DNA replication |

| topA | 1 | C | DNA topoisomerase 1 |

| Signal transduction | |||

| cpxR | 1 | C | Response regulator for CpxA |

| envZ | 1 | IM | Sensor protein for OmpR |

| ompR | 1 | C | Response regulator for EnvZ |

| qseC | 2 | IM | Sensor protein for QseB |

| Other | |||

| lon | 1 | C | Protease |

Abbreviations: C, cytosol; IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane; PS, periplasmic space; ECA, enterobacterial common antigen; P, promoter; T, terminator.

Synthetic lethal. All other gene combinations are synthetic sick.

Mapping transposon insertions by arbitrary polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (O’Toole & Kolter, 1998) uncovered 30 unique insertions in 22 genes and 3 intergenic regions (Table 1). Categorizing these genes and loci (Table 1) by function revealed that the majority of insertions (33%) were in genes that directly affect cell wall metabolism. These included insertions in cell wall hydrolases (dacA, ldcA, and mltG), cell wall synthases (mrcB), the Tol-Pal system (tolA, tolB, and pal), and the Und-PP encoding phosphatase pgpB, whose identification served as a positive proof-of-principle for the Δ3PP screen. We also isolated an insertion in the promoter of the actin homolog mreB (PmreB) (Table S1) that decreases mreB expression by approximately 40% (Figure S1). Since mreBCD are operonic (Wachi et al., 2006), we expect expression is decreased across the entire locus. Genes required for the late stages of enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) synthesis were also identified (wecD, wecE, and wzxE). Since disruptions in the ECA pathway sequester Und-PP-linked intermediates (Jorgenson et al., 2016), thus preventing Und-P(P) recycling, we expected to uncover this class of mutants. The remaining insertions were in genes or regions with no obvious connection to Und-P metabolism. These included genes required for cell division (ftsK, minD, TminE), glutathione formation (gor), DNA replication and repair (rep, seqA, and topA), and signal transduction (cpxR, envZ/ompR, and qseC). The insertion downstream of minE is situated in the middle of the first (of two) transcription termination sequence (de Boer et al., 1989). We also note that insertions in ftsK and topA were outside the essential region of these genes (Table S1) (Goodall et al., 2018).

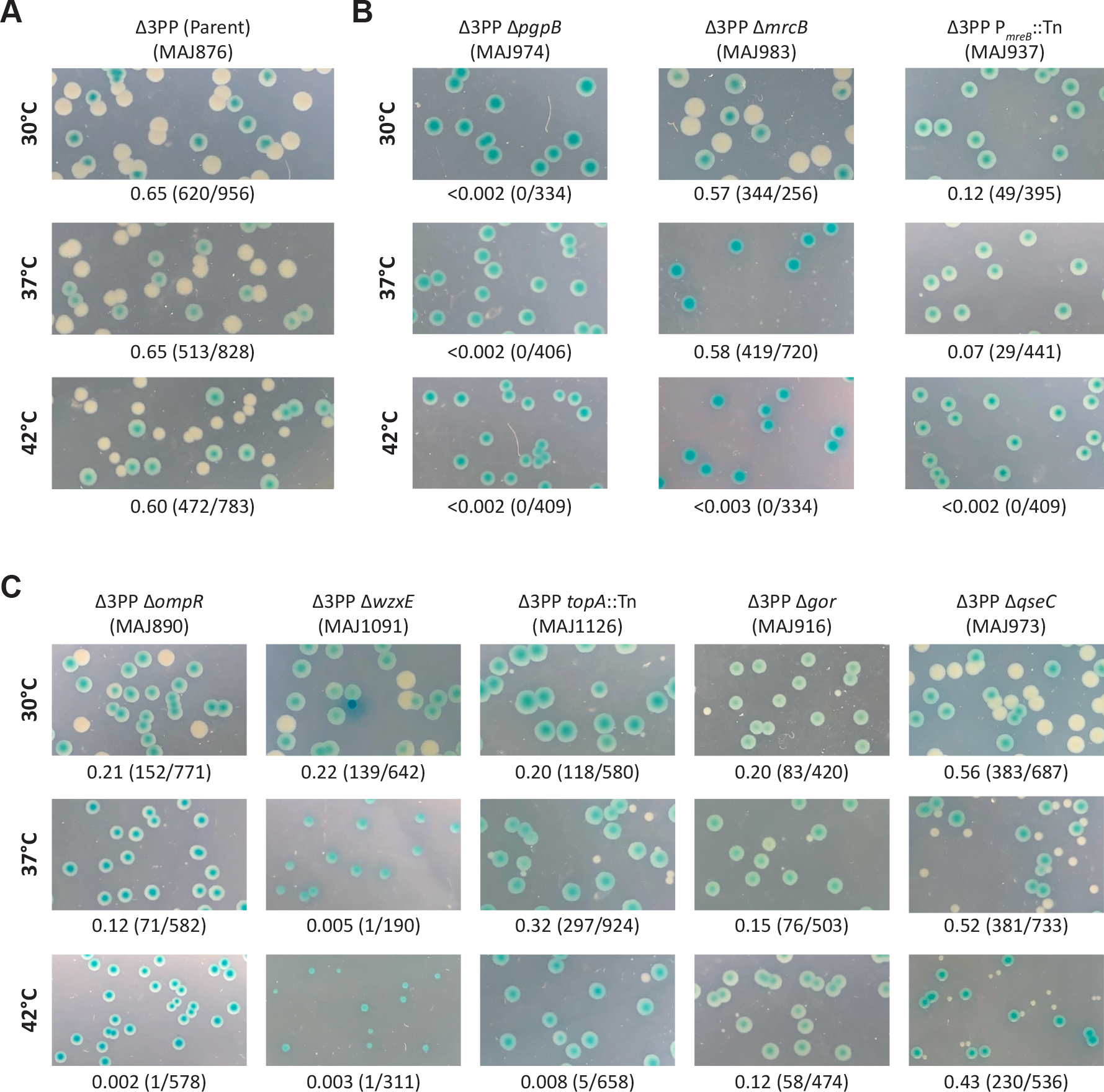

To verify that the colony phenotypes were due to the inactivation of these genes alone, we generated null mutations for most non-essential genes identified in the Δ3PP screen in the MAJ815/pbacA background. A representative mutant was picked for the ECA biosynthesis (ΔwzxE) and Tol-Pal (Δpal) pathways. In every case, the null mutants mirrored the colony phenotypes of their corresponding transposon mutant. Therefore, the null mutants were used in all subsequent studies. We also reintroduced the transposon insertion in PmreB into MAJ815/pbacA by P1 transduction and confirmed the colony phenotype (Figure 2B). As stated previously, only loss of PgpB resulted in solid-blue colonies at all temperatures (Figure 2), an indication of synthetic lethality. Alternatively, we observed that PBP1B (ΔmrcB) and PmreB mutants gave rise to exclusively solid-blue colonies at 42°C (Figure 2B). The outer membrane lipoprotein LpoB is required to activate PBP1B (Typas et al., 2010, Paradis-Bleau et al., 2010), but was not identified in the Δ3PP screen. Therefore, we determined whether a mutant lacking LpoB mirrors the phenotype a PBP1B-null mutant in the Δ3PP background. As expected, Δ3PP ΔlpoB cells produced solid-blue colonies only at 42°C (Figure S2). These results demonstrate that the screen was not saturating at 42°C. Removing ompR or wzxE, as well as disrupting topA in Δ3PP cells was also deleterious at high temperature, resulting in vanishingly few white colonies at 42°C (Figure 2C), indicating a mostly lethal interaction. Since mutants lacking Lon or Min filament/produce minicells, we confirmed their transposon mutants by microscopy (see below). In total, the Δ3PP screen identified system wide connections to Und-P metabolism.

Figure 2. Viability of Δ3PP mutant derivatives.

(A) pbacA readily segregates in the Δ3PP parent, resulting in white or sectored-blue colonies at 30°C, 37°C, and 42°C. (B and C) pbacA is retained in mutants that are synthetically lethal in the Δ3PP background and colonies appear solid-blue. Alternatively, the frequency of pbacA segregation is reduced in mutants that are synthetically sick in the Δ3PP background because pbacA confers a growth advantage. Above photographs: genotype and strain designation. Below photographs: fraction of white colonies to the total number of colonies. Additional Δ3PP mutant derivatives are shown in Figure S2 in the supplemental material.

The Δ3PP screen uncovers known and novel morphological determinants.

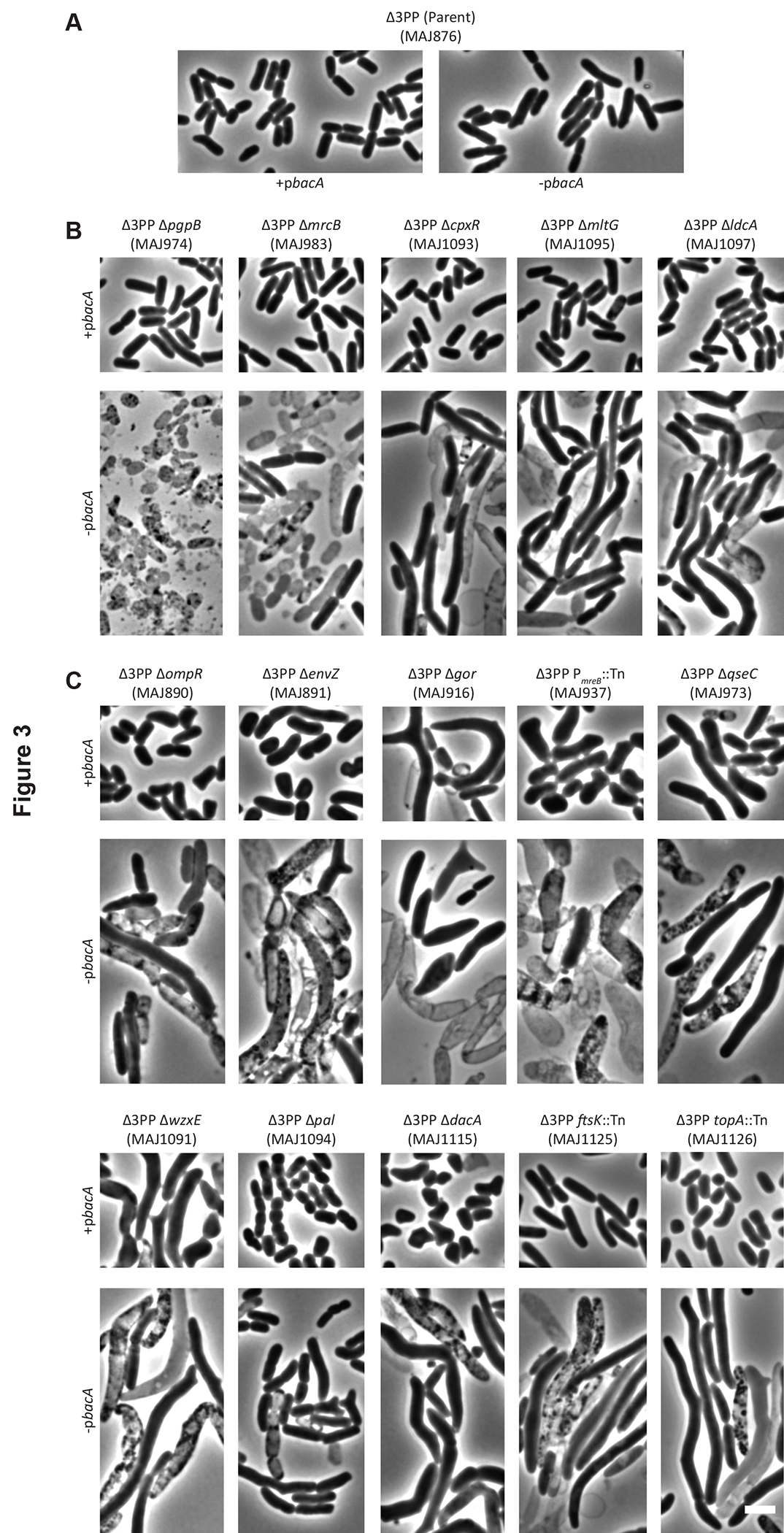

A steady supply of Und-P is required to maintain normal cell shape (Jorgenson et al., 2016, Jorgenson & Young, 2016), which suggested that synthetic interactions in the Δ3PP background might provoke shape defects. To determine whether our Δ3PP mutant derivatives harbored cell shape defects, cells were cultured in LB medium with or without chloramphenicol (to select for pbacA) and IPTG (to express bacA) at 37°C and 42°C. While loss of bacA expression had little effect on the morphology for the Δ3PP parent at 37°C (Figure S4A) or 42°C (Figure 3A), bacA expression was required to maintain cell shape and integrity for all Δ3PP mutants (Figure 3, S3, and S4), especially at 42°C (Figure 3 and S3B; compare the morphologies for +pbacA to -pbacA). We broadly categorized the phenotypes we observed as cell division or morphogenesis-related. All mutants were imaged at 37°C (Figure S3 and S4) and 42°C (Figure 3 and S3).

Figure 3. Morphology of Δ3PP mutant derivatives at 42°C.

Cells with the indicated genotypes were grown at 42°C in LB (-pbacA) or LB containing chloramphenicol and 500 μM IPTG (+pbacA) until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.3–0.4. The cells were then photographed by phase-contrast microscopy. Images of Δ3PP mutants grown at 37°C are shown in Figure S4 in the supplemental material. The white bar represents 3 μm. (A) The Δ3PP parent. (B) Mutant derivatives that produce shape defects in the absence of bacA expression. (C) Mutant derivatives that produce shape defects independent of bacA expression. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Mutants affected for cell division grew as long filaments irrespective of bacA expression (Figure S3). This included the Lon protease, which is required to set the basal level of SulA, an inhibitor of FtsZ (which initiates cell division) ring formation, through proteolytic degradation (Mizusawa & Gottesman, 1983, Higashitani et al., 1997) (Figure S3). Since SulA filaments cells in absence of Lon (Adler & Hardigree, 1964, Gayda et al., 1976), we reasoned that SulA was also responsible for filamenting Δ3PP lon::Tn cells (Figure S3). We note, however, that SulA is thermolabile and aggregates at 42°C (Mizrahi et al., 2007). Thus, it is unlikely that SulA is solely responsible for the shape defect of Δ3PP lon::Tn cells at 42°C. Mutations that disrupt seqA (Lu et al., 1994, Pedersen et al., 2017) or rep (Michel et al., 1997) lead to double-stranded DNA breaks, which activate the SOS response (Ossanna & Mount, 1989, Rotman et al., 2014), triggering sulA expression and thus filamentation (Figure S3). The Min proteins MinC, MinD, and MinE function to restrict FtsZ ring formation to midcell (de Boer et al., 1989). Importantly, loss of MinE enables MinCD complexes to inhibit FtsZ-ring formation throughout the cell, causing filamentation (de Boer et al., 1989). Since stem loops protect mRNA from ribonuclease degradation (Richards & Belasco, 2019), an insertion in the terminator of minE would likely promote 3’ exonucleolytic degradation of the min mRNA transcript. Therefore, TminE::Tn cells probably filament due to limiting amounts of MinE (Figure S3). We also note that disrupting the essential region of FtsK that functions in cell division induces filamentation (Begg et al., 1995). However, an insertion outside the essential region of FtsK that functions in DNA translocation (Table S1) (Goodall et al., 2018) only had a minor effect on cell length in Δ3PP cells when BacA was present (Figure 3C, +pbacA). Since disrupting the DNA translocase domain of ftsK induces sulA expression, this likely explains why ftsK::Tn (+pbacA) cells grow somewhat longer (Figure 3 and S4) (Liu et al., 1998). Interestingly, all of the filamenting mutants lysed in the absence of bacA expression when grown at 42°C (Figure S3B). This suggests that ongoing Und-PP phosphatase activity is critical in cells blocked for cell division at elevated temperature. More generally, we interpret the isolation of mutants that filament to issues pertaining to plasmid segregation. Since replication of the unstable plasmid and the chromosome initiate simultaneously (Frame & Bishop, 1971), this means that most, if not all, cell filaments will contain multiple copies of the mini-F plasmid due to the presence of multiple chromosomes. Thus, growing longer increases the likelihood of plasmid retention, which is why these mutants appear blue in our screen.

For those mutants affected for morphogenesis, we further divided these phenotypes as BacA-dependent or BacA-independent. BacA-dependent mutants produced rod-shaped cells when expressing bacA, but grew misshapen and/or lysed in its absence (Figure 3B; see also Figure S4B for 37°C morphologies). This mutant class was composed entirely of genes that affect PG metabolism, either directly or indirectly. Factors that directly affect PG metabolism included the Und-PP phosphatase PgpB (El Ghachi et al., 2005), the cell wall synthase PBP1B (ΔmrcB) (Sauvage et al., 2008), and the cell wall degrading enzymes MltG (Yunck et al., 2016) and LdcA (Templin et al., 1999). As expected, cells lacking all four Und-PP phosphatases (ΔpgpB) lysed completely, as did a significant fraction of Δ3PP cells deleted for mrcB (Figure 3B). This confirms and extends our previous finding that simultaneously inhibiting the production of Und-P and PG metabolism produces a synergistic response leading to cell lysis (Jorgenson et al., 2019). We also identified the response regulator CpxR from the CpxAR two-component signal transduction system (Raivio, 2014), which indirectly affects PG metabolism by regulating the expression of PG modifying enzymes (Weatherspoon-Griffin et al., 2011, Bernal-Cabas et al., 2015). This suggests that the Cpx response is critical for viability when Und-P is limiting.

BacA-independent mutants produced morphological defects, even when expressing bacA (Figure 3C; see also Figure S4C for 37°C morphologies). Again, many of the genes disrupted in this class of mutants produce factors already known to maintain cell shape. This included the ECA flippase WzxE (Rick et al., 2003) (Figure 3C), whose absence sequesters Und-P in non-recyclable intermediates causing cells to grow misshapen (Jorgenson et al., 2016). In addition, mutants lacking Pal do not efficiently constrict the cell envelope and produce chains of unseparated cells (Gerding et al., 2007), which we observed at 42°C (Figure 3C). DacA cleaves the terminal D-alanine from PG peptide side chains (Spratt & Strominger, 1976, Matsuhashi et al., 1979) and mutants grow as branched cells (Nelson & Young, 2000), which we also observed (Figure 3C and S4C). The mre locus encodes MreBCD, which are required to maintain rod shape (Wachi et al., 1989, Wachi et al., 1987), and MreB requires a steady supply of Und-P for proper polymerization and function (Schirner et al., 2015). In addition, limiting expression from the mre locus induces cells to enlarge and produce spherical shapes (Kruse et al., 2005). Not surprisingly, cells with an insertion in the promoter region of mreB were misshapen (i.e., longer, wider, rounder) (Figure 3C and S4C, +pbacA) and lysed in the absence of BacA (Figure 3C and S4C, -pbacA). Finally, TopA relaxes supercoiled DNA (Kirkegaard & Wang, 1985) and null mutants (harboring compensatory mutations) form long filaments (Usongo & Drolet, 2014); however, an insertion in the third zinc finger motif (nonessential region) of topA caused cells to grow as misshapen rods and spheres (Figure 3C and S4C). Interestingly, only the first two zinc finger motifs are required for TopA to bind DNA (Zumstein & Wang, 1986). Thus, TopA relies on efficient Und-PP dephosphorylation when disrupted for DNA binding for unknown reasons.

The BacA-independent mutants also contained several genes whose products were not known to affect morphology. These included both components of the EnvZ/OmpR two-component system, the glutathione reductase Gor, and QseC, the sensor kinase component of the QseBC two-component system. To determine whether these shape defects were due to the loss of these genes alone (and not due to the combined loss of the LpxT and YbjG Und-PP phosphatases), we deleted envZ, gor, ompR, or qseC from the parental wild type (i.e., MG1655 ΔlacIZYA). Importantly, these mutants exhibited morphologies similar to their Δ3PP derivatives when evaluated by microscopy and flow cytometry (compare morphologies in Figure 4 to those in Figure 3C and S4C). A closer inspection revealed that cells lacking QseC were 30% longer and 15% wider than the parental wild type when cultured at 37°C and 54% longer and 27% wider at 42°C (Table 2). When examined by flow cytometry, the distribution of the forward scatter area of ΔqseC cells was shifted to the right when compared to that of the parental wild type (Figure 4B), confirming that ΔqseC cells are enlarged. Mutants lacking EnvZ, Gor, or OmpR were also enlarged (Figure 4), but we also observed branching in these mutant backgrounds (Figure 4A). Branching arises when FtsZ, which initiates cell division, forms slanted rings (Potluri et al., 2012). Thus, FtsZ orientation is likely altered in these cells. We note that the mechanism of branching is not fully understood but is related to the activity of cell wall hydrolases (Potluri et al., 2012). As expected, expressing envZ, gor, ompR, or qseC from a plasmid reversed these shape defects (Figure S5). We also tested whether growing slower would correct morphology. To do this, we imaged ΔenvZ, Δgor, ΔompR, and ΔqseC cells grown in M9-glucose medium at 37°C and 42°C. As shown in Figure S6, these mutants produced virtually wild type morphologies. Thus, rapid growth promotes shape defects in cells lacking EnvZ, Gor, OmpR, or QseC. In summary, disrupting Und-P metabolism triggers shape defects in mutants whose gene products have direct or tangential connections to morphogenesis.

Figure 4. New shape-determinants.

(A) Cells with the indicated genotypes were grown at 37°C in LB until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.5. The cells were then photographed by phase-contrast microscopy. White arrows point to examples of branching. The white bar represents 3 μm. (B) Live cells from panel A were also examined by flow cytometry. Histograms of the forward scatter area from 100,000 events (cells) are shown. The mean cell size of the wild type is represented by the dashed line and is expressed in arbitrary units (AU). Data are representative of two independent experiments. The strains shown are MAJ25 (WT), MAJ964 (ΔenvZ), MAJ938 (ΔompR), MAJ969 (Δgor), and MAJ1005 (ΔqseC).

Table 2.

Morphological phenotypes of an E. coli qseC null mutant

| Genotypea | Temp (°C) | No. of cells evaluated | Avg. length, μm, (SD) | Avg. width, μm (SD) | % cells with indicated no. of constrictions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 0 | 1 | >1 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| WT | 30 | 371 | 2.9 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.1) | 68 | 32 | 0 |

| 37 | 319 | 2.6 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.1) | 62 | 38 | 0 | |

| 42 | 261 | 2.6 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.2) | 60 | 40 | 0 | |

|

| |||||||

| ΔqseC | 30 | 196 | 3.4 (1.1) | 1.3 (0.2) | 73 | 27 | 0 |

| 37 | 341 | 3.5 (1.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | 62 | 38 | 0 | |

| 42 | 264 | 4.5 (2.7) | 1.7 (0.2) | 58 | 42 | 0 | |

Strains used were MAJ25 (WT) and MAJ1005 (ΔqseC).

QseB overactivation disrupts cell shape.

At this point, we decided to characterize the ΔqseC mutant and will report on the envZ, gor, and ompR mutants later. QseC is a sensor kinase that phosphorylates QseB in response to autoinducer-3, epinephrine, and norepinephrine (Clarke et al., 2006). Phosphorylated QseB positively regulates its expression (Clarke & Sperandio, 2005a) as well the expression of flhDC, flagellar synthesis genes (Clarke & Sperandio, 2005b). Loss of QseC causes cross-phosphorylation of its response regulator QseB through PmrB (Guckes et al., 2013), another sensor kinase, resulting in constitutive action of QseB (Figure 5A). Overactivation of QseB disrupts metabolism (Hadjifrangiskou et al., 2011), reduces expression of virulence-associated genes (Kostakioti et al., 2009), and (as shown here) disrupts cell shape (Figure 4). Importantly, ΔqseC phenotypes are suppressed by deleting qseB or pmrB (Kostakioti et al., 2009, Bearson et al., 2010, Guckes et al., 2013).

Figure 5. QseB overactivation disrupts cell shape.

(A) Schematic depicting activated QseC phosphorylating and activating QseB (wild type). PmrB and one or more unknown factors (?) phosphorylate QseB in the absence of QseC (ΔqseC). Unlike QseC, however, PmrB cannot efficiently dephosphorylate QseB, leading to excessive amounts of activated QseB (Guckes et al., 2013). (B) Cells with the indicated genotypes were grown at 42°C in LB until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.5. The cells were then photographed by phase-contrast microscopy. The white bar represents 3 μm. (C) Live cells from panel B were also examined by flow cytometry. Histograms of the forward scatter area from 100,000 events (cells) are shown. The mean cell size of the wild type is represented by the dashed line and is expressed in arbitrary units (AU). Data are representative of two independent experiments. The strains shown are MAJ25 (WT), MAJ1002 (ΔpmrB), MAJ962 (ΔqseB), MAJ1005 (ΔqseC), MAJ1003 (ΔpmrB ΔqseC), and MAJ999 (ΔqseBC).

To determine if the shape defect of ΔqseC cells was related to QseB overactivation, we first constructed a mutant lacking QseC and QseB. Strikingly, loss of QseB completely reversed the shape defect of ΔqseC cells when grown in LB medium at 42°C (Figure 5B and 5C). Next, we determined whether deleting pmrB in ΔqseC cells would have a similar effect. Interestingly, loss of PmrB only partially reversed the shape defect of ΔqseC cells (Figure 5B and 5C). This result suggests that additional factors are capable of activating QseB (Figure 5A). The PmrAB two-component system also positively regulates qseB expression at the level of transcription through the PmrA response regulator, and deleting pmrA from ΔqseC cells can suppress some but not all ΔqseC phenotypes (Guckes et al., 2013). In this case, deleting pmrA had no effect on the shape of ΔqseC cells (Figure S7). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that constitutive activation of QseB, likely by multiple kinases or a combination of PmrB and small phosphate donors (McCleary et al., 1993), results in cell shape defects.

Evidence ruling out YgiW in the shape defect of ΔqseC cells.

In E. coli UTI189, QseB overactivation was observed to alter the expression of 443 genes (Hadjifrangiskou et al., 2011). Of the genes that were highly altered (e.g., qseB), the most upregulated gene was ygiW (fold change 2.8 × 1017). Interestingly, ygiW is located directly upstream of qseBC (Hadjifrangiskou et al., 2011) and codes for a predicted periplasmic protein of the bacterial oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding-fold (BOF, PF04076) protein family (Ginalski et al., 2004). Notably, the YgiW homolog in Salmonella typhimurium (i.e., VisP) binds PG in a pull-down assay (Moreira et al., 2013). Based on these observations, we reasoned that ygiW overexpression may interfere with PG synthesis in ΔqseC cells. However, deleting ygiW did not reverse the shape defect of ΔqseC cells (Figure S8). This result indicates that ygiW has no effect on shaping ΔqseC cells.

Multicopy suppression of the shape defect produced by ΔqseC cells.

To further determine the morphological basis for the ΔqseC shape defect, we isolated multicopy plasmids that reverse the shape defect of cells lacking QseC. Since Δ3PPΔqseC cells lacking pbacA produce small-colonies (Figure 2C) and grow as misshapen cells (Figure 3C and S4C), we reasoned that multicopy suppressing plasmids would produce large-colonies that grow as rod-shaped cells (Figure 6A). To do this, we first introduced a pBR322-based E. coli library (Ulbrandt et al., 1997) into strain MAJ973 (Δ3PPΔqseC/ pbacA), and screened approximately 30,000 colonies on LB-IX ampicillin (ampicillin selects for pBR322 derivatives) plates at 42°C for light blue colony formation, indicating segregation of pbacA. From these, we identified 21 light blue colonies that produced large colonies when purified on LB-IX agar at 42°C and rod-shaped cells when grown in LB medium containing ampicillin and 500 μM IPTG at 42°C. Conversely, small-colony white variants always produced misshapen cells.

Figure 6. Suppression of ΔqseC shape defects.

(A) Workflow of strategy to uncover multicopy plasmids that suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells. Δ3PP ΔqseC cells harboring pbacA produce predominantly blue colonies at 42°C (cf., Figure 2C). However, pbacA segregates in cells containing plasmids (pORF) that suppress the ΔqseC shape defect, and appear light blue (i.e., sectored-blue). Note that white colonies (indicating loss of pbacA) always yielded misshapen cells. (B) Micrographs of ΔqseC cells containing derivatives of pBRplac that express qseC or the small RNA rprA. Cells with the indicated genotypes were grown at 42°C in LB until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.5. The cells were then photographed by phase-contrast microscopy. The white bar represents 3 μm. (C) Live cells from panel B were also examined by flow cytometry. Histograms of the forward scatter area from 100,000 events (cells) are shown. The mean cell size of the wild type is represented by the dashed line and is expressed in arbitrary units (AU). Data are representative of two independent experiments. The strains shown are MAJ1177 (pqseC), MAJ1143 (vector), MAJ1144 (—), MAJ1151 (ΔrpoS), and MAJ1163 (Δhfq/prprA).

Candidate plasmids were subsequently isolated and transformed into ΔqseC (MAJ1005) cells and examined for shape suppression at 42°C as above. From these, we identified two classes of suppressing plasmids. The first class fully restored ΔqseC cells to the size and shape of wild type cells, and included plasmids harboring qseC or rprA, a small regulatory RNA (Majdalani et al., 2001). The second class of suppressing plasmids partially reversed the shape defect of ΔqseC cells, and consisted entirely of plasmids containing pdhR, a transcriptional regulator (Quail & Guest, 1995). Plasmids expressing only qseC, rprA, or pdhR produced the same results as the pBR322 derivatives (Figure 6 and S9), confirming that overexpressing rprA and, to a lesser extent, pdhR can suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells. To our knowledge, multicopy shape suppression by rprA is the first example of a small RNA acting as a shape suppressor. During the course of these experiments, we also tested whether overexpressing the Und-PP synthase uppS could suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells. However, uppS overexpression had no effect on the shape of ΔqseC cells (Figure S5). This suggests Und-P(P) is not limiting in QseC cells.

Shape suppression of ΔqseC cells by multicopy rprA requires Hfq but not RpoS

We next sought to determine what factors were required for shape suppression of ΔqseC cells by multicopy rprA. RprA (RpoS regulator RNA) positively regulates translation of the stationary phase sigma factor RpoS (Majdalani et al., 2001) by binding to and stabilizing rpoS mRNA (Majdalani et al., 2002), an interaction that is enhanced by the RNA-binding protein Hfq (Soper et al., 2010). We reasoned that the function of one of these factors was important to suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells by multicopy rprA. To determine the contribution of RpoS to multicopy shape suppression of ΔqseC cells by RprA, we overexpressed rprA in a ΔqseC ΔrpoS mutant. Surprisingly, loss of RpoS had no appreciable effect on shape suppression (Figure 6B and 6C). This suggests that activation of the general stress response is not required to suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells by multicopy rprA. Since Hfq enhances RprA-RNA binding (Soper et al., 2010), we reasoned that loss of Hfq might prevent RprA activity. Indeed, multicopy rprA failed to restore cell shape to ΔqseC Δhfq cells, which formed bulges (Figure 6B and 6C). This result suggests an alternative RprA-RNA interaction is required to suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells. We note that Hfq is required to maintain normal cell shape (Tsui et al., 1994, Lybecker et al., 2010, Bai et al., 2010, Wilms et al., 2012, Boudry et al., 2014, Irnov et al., 2017) (Figure S7). RprA also regulates the expression of csgD and ydaM (Jorgensen et al., 2012, Mika et al., 2012), but these factors were not required for multicopy shape suppression of ΔqseC cell by RprA (Figure S10). Collectively, these data indicate that RprA plays a role in maintaining cell shape by an unknown mechanism.

Discussion

Walled bacteria employ polyprenyl carrier lipids to assemble and transport cell wall intermediates (Manat et al., 2014). In E. coli, like most bacteria, Und-P serves as the primary lipid carrier and is essential (Kato et al., 1999). Since Und-P originates from the dephosphorylation of Und-PP, the phosphatases required to generate the monophosphate linkage are conditionally essential (El Ghachi et al., 2004, El Ghachi et al., 2005). Here, we took advantage of this functional overlap to identify new connections to Und-P metabolism. Utilizing a derivative of the unstable mini-F plasmid system (Bernhardt & de Boer, 2004), we identified synthetically sick and lethal interactions in the absence of three (out of four) Und-PP phosphatases in E. coli. The screen was highly successful, netting several known connections to Und-P metabolism as well as entirely new connections. The absolute requirement of Und-P for PG metabolism (Kato et al., 1999) means that the screen was primed to uncover PG-intersecting pathways, which we show were present in greater numbers than previously thought. In short, we demonstrate the utility of disrupting Und-P metabolism to find new ways to inhibit bacterial growth and uncover subtle biological circuits.

Und-PP metabolism questions not resolved by the Δ3PP screen.

Several open questions regarding Und-P(P) metabolism were not resolved by the Δ3PP screen. For example, Und-PP dephosphorylation occurs extracellularly (Tatar et al., 2007, Touze et al., 2008, Manat et al., 2015), yet it is not known how Und-PP is flipped from the inner side of the cytoplasmic membrane to the outer side or how it is flopped back as Und-P. In addition, it is not known whether there are additional Und-PP phosphatases, noting that the BacA and PAP2 protein families share no sequence similarity (El Ghachi et al., 2005). Finally, whether all Und-P-utilizing pathways have been identified in E. coli is not settled. The results from the Δ3PP screen suggest two possibilities. First, factors that transport, dephosphorylate, or utilize Und-P(P) are already known, to varying degrees. We consider this the most likely possibility. Alternatively, additional factors required for Und-PP metabolism exist but are essential or were missed for other (unknown) reasons. Identifying Und-P(P) interactions in environmental isolates or Gram-positive organisms may help distinguish between these possibilities. More broadly, questions regarding the synthesis and metabolism of Und-P(P) have important implications toward treating bacterial infections (see below) and engineering bacteria to produce isoprenoid derivatives for high-value pharmaceuticals and industrial products (Tetali, 2019).

Surface area to volume requirements likely explain the basis for Δ3PP mutant morphologies.

Why do Δ3PP mutant derivatives grow bigger in the absence of BacA? While it makes some sense that inhibiting multiple PG-affecting pathways would cause cells to grow more misshapen, it is not obvious why they always grow larger. This basic question is rooted in fundamental laws governing how cells grow and determine their shape. The ‘relative rates’ model assumes that bacteria alter their dimensions so that the ratio of surface area to volume (SA/V) homeostasis equals the ratio of (β) surface synthesis to (α) volume synthesis (i.e., SA/V=β/α) (Harris et al., 2014, Harris & Theriot, 2018, Harris & Theriot, 2016). Thus, the ‘relative rates’ model predicts that in cases where surface synthesis (β) decreases and volume synthesis (α) increases, cells will reduce SA/V to re-establish SA/V homeostasis. This type of situation occurs when PG precursor synthesis is inhibited (Harris & Theriot, 2016, Si et al., 2017, Real & Henriques, 2006). In such cases, bacteria reduce SA/V by growing longer and wider (i.e., bigger).

Since decreasing Und-PP dephosphorylation is expected to reduce PG precursor formation, the ‘relative rates’ model would predict Δ3PP cells to grow even longer and wider if inhibited further for PG synthesis, which we observed for all Δ3PP mutant derivatives (Figure 3 and S4). We also interpret this observation to mean that any mutation that causes cells to grow bigger could compensate for defects in Und-P(P) metabolism. In cases where cells lysed, dimensional changes were likely insufficient to lower SA/V beyond the threshold needed to withstand the force generated by internal osmotic (turgor) pressure. To that end, E. coli grows to a maximum width of 1.5–2.0 μm; cells that grow beyond this limit become misshapen and lyse (Tropini et al., 2014). Not surprisingly, Δ3PP derivatives with widths that exceed this limit were usually lysed (Figure 3 and S4). In short, the ‘relative rates’ model provides a likely explanation why inhibiting Und-PP dephosphorylation primes cells with otherwise imperceptible defects in PG synthesis to grow larger. Whether reducing PG precursors in other contexts would identify similar pathways is unknown.

The link between Und-P and DNA replication/translocation.

What underlies the link between Und-P(P) metabolism and DNA replication/translocation? We think the answer to this question is related to the SOS response. Antibiotics that target early (Perez-Capilla et al., 2005) and late stages (Miller et al., 2004, Perez-Capilla et al., 2005) of cell wall synthesis induce the SOS response which, in addition to triggering sulA expression, also activates specialized translesion synthesis (TLS) polymerases Pol II (PolB), Pol IV (DinB), and Pol V (UmuDC) (Maslowska et al., 2019). An important aspect to these polymerases is that they are error-prone and mutagenize undamaged DNA. Interestingly, antibiotics that target the early stages of cell wall synthesis induce dinB expression (Perez-Capilla et al., 2005). Since defects in Und-P(P) metabolism also disrupt cell wall assembly at the point of synthesis (Paradis-Bleau et al., 2014, Jorgenson et al., 2016), it may be that the SOS response is triggered (albeit at a low level) in Δ3PP cells. If so, any mutation that further stimulates the SOS response in Δ3PP cells may produce a lethal combination of mutations via the activity of TLS polymerases. This could explain the disparate morphologies we observe in populations of Δ3PP derivatives inhibited for DNA replication (rep, seqA, topA) and translocation (ftsK) (Figure 3, S3, and S4).

Reexamining the physiological functions of the QseBC two-component system.

The QseBC system is known as a global regulator (Weigel & Demuth, 2016), responsible for controlling biofilm formation and virulence. This designation is due, in large measure, to the use of qseC mutants. For example, loss of QseC impairs biofilm formation of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Novak et al., 2010, Juarez-Rodriguez et al., 2013) and Haemophilus influenzae (Unal et al., 2012). Similarly, qseC mutants are attenuated for virulence in enterohemorrhagic (Clarke et al., 2006) and uropathogenic E. coli (Kostakioti et al., 2009), as well as in Salmonella enterica Typhimurium (Moreira et al., 2010, Bearson & Bearson, 2008). However, qseB mutants, which would be expected to mirror qseC mutants, do not exhibit similar defects in terms of biofilm formation (Wang et al., 2011), motility (Hughes et al., 2009, Guckes et al., 2013, Kostakioti et al., 2009), virulence (Kostakioti et al., 2009), and now cell shape (Figure 5). These differences are likely due to the fact that mutants lacking QseC, but not QseB, grow misshapen and lyse. This means that (some) functions previously attributed to QseBC may actually be indirect consequences of a PG biogenesis defect. To that end, QseB does not appear to regulate cell wall modifying genes (Sperandio et al., 2002, Pasupuleti et al., 2018, Gou et al., 2019), suggesting that QseB overactivation indirectly affects cell wall synthesis. In summary, we recommend that conclusions based on qseC mutants be reevaluated to account for indirect effects on the cell wall, ideally by comparing qseC to qseB mutants.

An expanding view of the RprA regulon.

How does RprA overexpression reverse the shape defect of ΔqseC cells? While we were surprised that RprA functioned independent of its established target to suppress the shape defect of ΔqseC cells, similar effects have also been observed for RprA inhibition of the CpxAR two-component signal transduction pathway (Vogt et al., 2014). Specifically, rprA overexpression represses expression of cpxP and degP, members of the CpxR regulon, independent of rpoS, csgD, and ydaM (Vogt et al., 2014). Whether RprA suppresses the shape defect of ΔqseC cells and inhibits the Cpx pathway by the same mechanism is unknown. However, such examples strongly suggest there are unexplored regulatory pathways that RprA controls. Indeed, RprA is predicted to bind, with various affinity, at least 200 mRNAs according to the CopraRNA database (version 2.1.2) (Raden et al., 2018). Thus, dissecting the RprA regulon will likely provide important insights into the mechanisms employed by bacteria to overcome (severe) cell envelope defects. Since rprA expression is controlled by the Rcs signal transduction pathway (Wall et al., 2018), we expect this system to play an important role in cells lacking qseC function.

Morphological phenotyping informs gene function and potential therapies.

The number and types of assays used to study gene function vary as widely as the pathways they represent. For some experiments though, time and cost play outsized roles in determining the extent and rigor of investigation. In such cases, identifying alternative approaches based on some phenotypic trait is critical. Historically, growth has served this function [e.g., (Typas et al., 2008, Nichols et al., 2011)]. However, since most mutants grow normally, more recent efforts have attempted to systematically catalog morphological phenotypes (French et al., 2017, Campos et al., 2018, Zahir et al., 2019). Here we corroborate, extend, and add to the collective morphological record 19 genes (and implicate several others) whose mutants produce shape defects in a matter of hours using relatively inexpensive reagents (i.e., LB). Moreover, the profound morphologies generated by these mutants in the Δ3PP background obviate the need for more specialized and quantitative analysis, and may serve as a useful proxy to assay the function of some of these genes.

Finally, the morphological data provided by this study may inform future, life-saving therapies. For example, increasing temperature above 37°C exacerbates the phenotype of envZ, gor, ompR, or qseC mutants (Figure 3 and S4). Since bacterial infections can induce sustained febrile responses in excess of 39°C (Ogoina, 2011), inhibitors against these proteins during febrile episodes may potentiate established treatments to shorten the duration and effects of certain bacterial infections. Thus, morphological phenotyping should be considered when designing new antibiotic treatment regimens.

Materials and methods

Media.

Cells were cultured in LB Miller broth (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 1% NaCl; IBI Scientific), λYM broth (1% tryptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 0.25% NaCl, and 0.2% maltose), or minimal M9 broth (1X M9 salts, 0.5 mg ml−1 thiamine, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2; Teknova). Glucose was added to M9 broth at 0.2%. Plates contained 1.5% agar (Difco). As required, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin, 20 μg ml−1 chloramphenicol, 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin, and 10 μg ml−1 tetracycline.

Strains, plasmids, and primers.

All strains, plasmids, and primers are listed in Tables S2, S3, and S4 in the supporting information, respectively. All oligonucleotides primers were obtained from Eurofins Genomics.

Strain and plasmid construction.

E. coli MG1655 ΔlacIZYA is the parent strain for this study (Bernhardt & de Boer, 2004). Gene deletions were constructed by using lambda Red recombination (Datsenko & Wanner, 2000) or P1-mediated transduction (Miller, 1972). Kanamycin resistance markers were evicted by using FLP recombinase produced from pCP20 (Cherepanov & Wackernagel, 1995). All gene deletions were verified by PCR. Plasmid construction is detailed in SI Text in the supporting information. All reference sequences were obtained from the Ecocyc database (Keseler et al., 2017). PCR fragments were purified by using the DNA clean and concentrator kit (Zymo Research). Plasmids were purified by using the Qiaprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen).

Phage mutagenesis and screen to identify Δ3PP synthetic interactions.

Overnight cultures of MAJ876 [ΔlacIZYA ΔlpxT ΔybjG ΔbacA/cat Plac::bacA lacZ] were washed with λYM broth and resuspended in λYM broth. Cells were diluted 1:10 into the same medium and mutagenized with mini-Tn10 by infecting with phage λ1098 (Way et al., 1984) at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5. After 30 minutes at room temperature, cells were grown for 1.5 h at 37°C. Cells were then plated on LB agar containing tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and 500 μM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside; Research Products International) and incubated at 37°C overnight. The phage mutagenesis yielded approximately 50,000 colonies (spread over 20 plates) that were resuspened in approximately 5 mL of LB medium containing 500 μM IPTG. Glycerol was added to 15% and the library was frozen at −80°C.

The mutant library was screened by preparing a 1 × 10−6 dilution in LB medium and plating on LB agar containing 60 μg ml−1 X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside, Abcam) and 500 μM IPTG. [Note: tetracycline was omitted to prevent selection of insertions in pbacA]. Plates were incubated at 30°C, 37°C, or 42°C until X-Gal staining was clearly visible (i.e., usually 24 – 48 h). We screened between 60,000 and 150,000 colonies at each temperature, and purified those colonies that appeared solid-blue on LB agar containing 60 μg ml−1 X-gal and 500 μM IPTG. The positions of mini-Tn10 insertions were determined by arbitrary PCR (O’Toole & Kolter, 1998) as described previously (Bernhardt & de Boer, 2004) using primer pairs P140/P695 (first amplification) and P141/P696 (second amplification).

Colony phenotyping Δ3PP strain derivatives.

Overnight cultures carrying pbacA were diluted 1 × 10−6 in LB medium and plated on LB agar containing 60 μg ml-1 X-Gal and 500 μM IPTG. Plates were incubated at 30°C, 37°C, or 42°C as described above and imaged by using an iPhone X (Apple Inc.).

Morphological analysis of Δ3PP strain derivatives.

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:2,000 in LB medium or LB medium containing chloramphenicol (to select for pbacA) and 500 μM IPTG and grown at 37°C or 42°C to mid-exponential phase. Live cells were then spotted on 1% agarose pads and imaged by phase-contrast microscopy by using an Olympus BX60 microscope. Images were captured by using an XM10 monochrome camera. Live cells were also prepared for flow cytometry. Briefly, 1 mL of cells (above) were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in room temperature phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 9 mM NaH2PO4, and 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Cells were washed twice in PBS, diluted to an OD600 ~0.05, and analyzed by using the forward scatter detector in a BD LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer at the UAMS Flow Cytometry Core Facility. Morphological measurements were made using the cellSens Dimensions software (Olympus). The average maximum width of a population of cells is noted in Table 2.

Isolating multicopy suppressors of ΔqseC.

A pBR322-based E. coli library (Ulbrandt et al., 1997) was introduced into MAJ973 (Δ3PPΔqseC/pbacA) by electroporation. Transformants were plated onto LB-IX plates containing ampicillin and 500 μM IPTG and incubated at 42°C overnight. Approximately 30,000 colonies were screened and those colonies that appeared light blue, indicating loss of pbacA, were purified. From these, we observed the formation of small- and large-colony variants. Overnight cultures of cells from the small and large-colony variants were diluted 1:2,000 in LB medium containing ampicillin and 500 μM IPTG, grown at 42°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ~0.5, and imaged under phase-contrast microscopy. Microscopic analysis revealed that large colony variants produced rod-shaped cells whereas small colony variants produced misshapen cells. Plasmids were isolated from the large-colony variants, transformed into MAJ1005 (ΔqseC), and tested for their ability to reverse the shape defect of ΔqseC cells as above. Suppressing plasmids were sequenced using primers P735 and P736.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Susan Gottesman and Nadim Majdalani (NCI) for providing the pORF library, plasmids pBRplac and prprA, and for technical guidance. We thank Kenn Gerdes for providing the anti-MreB antibody. We thank Kevin Young for helpful discussions during the preparation of this manuscript. We also thank Anne Darley and Victoria Marcelle for technical assistance. This study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences NIH grant GM061019. The UAMS DNA and flow cytometry core facilities are supported in part by the Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Inflammatory Responses NIH grant GM103625. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Adler HI, and Hardigree AA (1964) Analysis of a Gene Controlling Cell Division and Sensitivity to Radiation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 87: 720–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Golubov A, Smith EA, and McDonough KA (2010) The importance of the small RNA chaperone Hfq for growth of epidemic Yersinia pestis, but not Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, with implications for plague biology. J Bacteriol 192: 4239–4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearson BL, and Bearson SM (2008) The role of the QseC quorum-sensing sensor kinase in colonization and norepinephrine-enhanced motility of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microb Pathog 44: 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearson BL, Bearson SM, Lee IS, and Brunelle BW (2010) The Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium QseB response regulator negatively regulates bacterial motility and swine colonization in the absence of the QseC sensor kinase. Microb Pathog 48: 214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg KJ, Dewar SJ, and Donachie WD (1995) A new Escherichia coli cell division gene, ftsK. J Bacteriol 177: 6211–6222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Cabas M, Ayala JA, and Raivio TL (2015) The Cpx envelope stress response modifies peptidoglycan cross-linking via the L,D-transpeptidase LdtD and the novel protein YgaU. J Bacteriol 197: 603–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt TG, and de Boer PA (2004) Screening for synthetic lethal mutants in Escherichia coli and identification of EnvC (YibP) as a periplasmic septal ring factor with murein hydrolase activity. Mol Microbiol 52: 1255–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar AP, Beveridge TJ, and Brown ED (2001) Precise deletion of tagD and controlled depletion of its product, glycerol 3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, leads to irregular morphology and lysis of Bacillus subtilis grown at physiological temperature. J Bacteriol 183: 6688–6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudry P, Gracia C, Monot M, Caillet J, Saujet L, Hajnsdorf E, Dupuy B, Martin-Verstraete I, and Soutourina O (2014) Pleiotropic role of the RNA chaperone protein Hfq in the human pathogen Clostridium difficile. J Bacteriol 196: 3234–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhss A, Trunkfield AE, Bugg TD, and Mengin-Lecreulx D (2008) The biosynthesis of peptidoglycan lipid-linked intermediates. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32: 208–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos M, Govers SK, Irnov I, Dobihal GS, Cornet F, and Jacobs-Wagner C (2018) Genomewide phenotypic analysis of growth, cell morphogenesis, and cell cycle events in Escherichia coli. Mol Syst Biol 14: e7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov PP, and Wackernagel W (1995) Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MB, Hughes DT, Zhu C, Boedeker EC, and Sperandio V (2006) The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10420–10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MB, and Sperandio V (2005a) Transcriptional autoregulation by quorum sensing Escherichia coli regulators B and C (QseBC) in enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). Mol Microbiol 58: 441–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MB, and Sperandio V (2005b) Transcriptional regulation of flhDC by QseBC and sigma (FliA) in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 57: 1734–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson L, Powers J, and Whitfield C (2005) The C-terminal domain of the nucleotide-binding domain protein Wzt determines substrate specificity in the ATP-binding cassette transporter for the lipopolysaccharide O-antigens in Escherichia coli serotypes O8 and O9a. J Biol Chem 280: 30310–30319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarny TL, Perri AL, French S, and Brown ED (2014) Discovery of Novel Cell Wall-Active Compounds Using P-ywaC, a Sensitive Reporter of Cell Wall Stress, in the Model Gram-Positive Bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 58: 3261–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, and Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer PA, Crossley RE, and Rothfield LI (1989) A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the minicell locus determine proper placement of the division septum in E. coli. Cell 56: 641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan AJF, Errington J, and Vollmer W (2020) Regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis and remodelling. Nat Rev Microbiol 18: 446–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghachi M, Bouhss A, Blanot D, and Mengin-Lecreulx D (2004) The bacA gene of Escherichia coli encodes an undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase activity. J Biol Chem 279: 30106–30113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghachi M, Derbise A, Bouhss A, and Mengin-Lecreulx D (2005) Identification of multiple genes encoding membrane proteins with undecaprenyl pyrophosphate phosphatase (UppP) activity in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 280: 18689–18695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhenawy W, Davis RM, Fero J, Salama NR, Felman MF, and Ruiz N (2016) The O-Antigen Flippase Wzk Can Substitute for MurJ in Peptidoglycan Synthesis in Helicobacter pylori and Escherichia coli. Plos One 11: e0161587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farha MA, Czarny TL, Myers CL, Worrall LJ, French S, Conrady DG, Wang Y, Oldfield E, Strynadka NC, and Brown ED (2015) Antagonism screen for inhibitors of bacterial cell wall biogenesis uncovers an inhibitor of undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 11048–11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame R, and Bishop JO (1971) The number of sex-factors per chromosome in Escherichia coli. Biochem J 121: 93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French S, Cote JP, Stokes JM, Truant R, and Brown ED (2017) Bacteria Getting into Shape: Genetic Determinants of E. coli Morphology. Mbio 8: e01977–01916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasiorowski E, Auger R, Tian X, Hicham S, Ecobichon C, Roure S, Douglass MV, Trent MS, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Touze T, and Boneca IG (2019) HupA, the main undecaprenyl pyrophosphate and phosphatidylglycerol phosphate phosphatase in Helicobacter pylori is essential for colonization of the stomach. PLoS Pathog 15: e1007972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayda RC, Yamamoto LT, and Markovitz A (1976) Second-site mutations in capR (lon) strains of Escherichia coli K-12 that prevent radiation sensitivity and allow bacteriophage lambda to lysogenize. J Bacteriol 127: 1208–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerding MA, Ogata Y, Pecora ND, Niki H, and de Boer PAJ (2007) The trans-envelope Tol-Pal complex is part of the cell division machinery and required for proper outer-membrane invagination during cell constriction in E. coli. Molecular Microbiology 63: 1008–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginalski K, Kinch L, Rychlewski L, and Grishin NV (2004) BOF: a novel family of bacterial OB-fold proteins. FEBS Lett 567: 297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall ECA, Robinson A, Johnston IG, Jabbari S, Turner KA, Cunningham AF, Lund PA, Cole JA, and Henderson IR (2018) The Essential Genome of Escherichia coli K-12. MBio 9: e02096–02017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou Y, Liu W, Wang JJ, Tan L, Hong B, Guo L, Liu H, Pan Y, and Zhao Y (2019) CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of qseB induced asynchrony between motility and biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Can J Microbiol 65: 691–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guckes KR, Kostakioti M, Breland EJ, Gu AP, Shaffer CL, Martinez CR 3rd, Hultgren SJ, and Hadjifrangiskou M (2013) Strong cross-system interactions drive the activation of the QseB response regulator in the absence of its cognate sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 16592–16597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjifrangiskou M, Kostakioti M, Chen SL, Henderson JP, Greene SE, and Hultgren SJ (2011) A central metabolic circuit controlled by QseC in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 80: 1516–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LK, Dye NA, and Theriot JA (2014) A Caulobacter MreB mutant with irregular cell shape exhibits compensatory widening to maintain a preferred surface area to volume ratio. Molecular Microbiology 94: 988–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LK, and Theriot JA (2016) Relative Rates of Surface and Volume Synthesis Set Bacterial Cell Size. Cell 165: 1479–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LK, and Theriot JA (2018) Surface Area to Volume Ratio: A Natural Variable for Bacterial Morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol 26: 815–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Rocamora VM, Otten CF, Radkov A, Simorre JP, Breukink E, VanNieuwenhze M, and Vollmer W (2018) Coupling of polymerase and carrier lipid phosphatase prevents product inhibition in peptidoglycan synthesis. Cell Surf 2: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashitani A, Ishii Y, Kato Y, and Koriuchi K (1997) Functional dissection of a cell-division inhibitor, SulA, of Escherichia coli and its negative regulation by Lon. Mol Gen Genet 254: 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DT, Clarke MB, Yamamoto K, Rasko DA, and Sperandio V (2009) The QseC adrenergic signaling cascade in Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). PLoS Pathog 5: e1000553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WN (2007) The non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 282: 21573–21577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irnov I, Wang Z, Jannetty ND, Bustamante JA, Rhee KY, and Jacobs-Wagner C (2017) Crosstalk between the tricarboxylic acid cycle and peptidoglycan synthesis in Caulobacter crescentus through the homeostatic control of alpha-ketoglutarate. Plos Genetics 13: e1006978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen MG, Nielsen JS, Boysen A, Franch T, Moller-Jensen J, and Valentin-Hansen P (2012) Small regulatory RNAs control the multi-cellular adhesive lifestyle of Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology 84: 36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson MA, Kannan S, Laubacher ME, and Young KD (2016) Dead-end intermediates in the enterobacterial common antigen pathway induce morphological defects in Escherichia coli by competing for undecaprenyl phosphate. Mol Microbiol 100: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson MA, MacCain WJ, Meberg BM, Kannan S, Bryant JC, and Young KD (2019) Simultaneously inhibiting undecaprenyl phosphate production and peptidoglycan synthases promotes rapid lysis in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 112: 233–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson MA, and Young KD (2016) Interrupting biosynthesis of O antigen or the lipopolysaccharide core produces morphological defects in Escherichia coli by sequestering undecaprenyl phosphate. J Bacteriol 198: 3070–3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez-Rodriguez MD, Torres-Escobar A, and Demuth DR (2013) ygiW and qseBC are co-expressed in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and regulate biofilm growth. Microbiology 159: 989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato J, Fujisaki S, Nakajima K, Nishimura Y, Sato M, and Nakano A (1999) The Escherichia coli homologue of yeast RER2, a key enzyme of dolichol synthesis, is essential for carrier lipid formation in bacterial cell wall synthesis. J Bacteriol 181: 2733–2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keseler IM, Mackie A, Santos-Zavaleta A, Billington R, Bonavides-Martinez C, Caspi R, Fulcher C, Gama-Castro S, Kothari A, Krummenacker M, Latendresse M, Muniz-Rascado L, Ong Q, Paley S, Peralta-Gil M, Subhraveti P, Velazquez-Ramirez DA, Weaver D, Collado-Vides J, Paulsen I, and Karp PD (2017) The EcoCyc database: reflecting new knowledge about Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res 45: D543–D550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkegaard K, and Wang JC (1985) Bacterial-DNA Topoisomerase-I Can Relax Positively Supercoiled DNA Containing a Single-Stranded Loop. Journal of Molecular Biology 185: 625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostakioti M, Hadjifrangiskou M, Pinkner JS, and Hultgren SJ (2009) QseC-mediated dephosphorylation of QseB is required for expression of genes associated with virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology 73: 1020–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse T, Bork-Jensen J, and Gerdes K (2005) The morphogenetic MreBCD proteins of Escherichia coli form an essential membrane-bound complex. Mol Microbiol 55: 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, and Helmann JD (2013) Reducing the Level of Undecaprenyl Pyrophosphate Synthase Has Complex Effects on Susceptibility to Cell Wall Antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57: 4267–4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GW, Draper GC, and Donachie WD (1998) FtsK is a bifunctional protein involved in cell division and chromosome localization in Escherichia coli. Molecular Microbiology 29: 893–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Campbell JL, Boye E, and Kleckner N (1994) SeqA: a negative modulator of replication initiation in E. coli. Cell 77: 413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lybecker MC, Abel CA, Feig AL, and Samuels DS (2010) Identification and function of the RNA chaperone Hfq in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol 78: 622–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCain WJ, Kannan S, Jameel DZ, Troutman JM, and Young KD (2018) A Defective Undecaprenyl Pyrophosphate Synthase Induces Growth and Morphological Defects That Are Suppressed by Mutations in the Isoprenoid Pathway of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 200: e00255–00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdalani N, Chen S, Murrow J, St John K, and Gottesman S (2001) Regulation of RpoS by a novel small RNA: the characterization of RprA. Mol Microbiol 39: 1382–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdalani N, Hernandez D, and Gottesman S (2002) Regulation and mode of action of the second small RNA activator of RpoS translation, RprA. Mol Microbiol 46: 813–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manat G, El Ghachi M, Auger R, Baouche K, Olatunji S, Kerff F, Touze T, Mengin-Lecreulx D, and Bouhss A (2015) Membrane Topology and Biochemical Characterization of the Escherichia coli BacA Undecaprenyl-Pyrophosphate Phosphatase. PLoS One 10: e0142870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manat G, Roure S, Auger R, Bouhss A, Barreteau H, Mengin-Lecreulx D, and Touze T (2014) Deciphering the metabolism of undecaprenyl-phosphate: the bacterial cell-wall unit carrier at the membrane frontier. Microb Drug Resist 20: 199–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowska KH, Makiela-Dzbenska K, and Fijalkowska IJ (2019) The SOS system: A complex and tightly regulated response to DNA damage. Environ Mol Mutagen 60: 368–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhashi M, Tamaki S, Curtis SJ, and Strominger JL (1979) Mutational evidence for identity of penicillin-binding protein 5 in Escherichia coli with the major D-alanine carboxypeptidase IA activity. J Bacteriol 137: 644–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary WR, Stock JB, and Ninfa AJ (1993) Is acetyl phosphate a global signal in Escherichia coli? J Bacteriol 175: 2793–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeske AJ, Sham LT, Kimsey H, Koo BM, Gross CA, Bernhardt TG, and Rudner DZ (2015) MurJ and a novel lipid II flippase are required for cell wall biogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 6437–6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel B, Ehrlich SD, and Uzest M (1997) DNA double-strand breaks caused by replication arrest. EMBO J 16: 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mika F, Busse S, Possling A, Berkholz J, Tschowri N, Sommerfeldt N, Pruteanu M, and Hengge R (2012) Targeting of csgD by the small regulatory RNA RprA links stationary phase, biofilm formation and cell envelope stress in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 84: 51–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, Thomsen LE, Gaggero C, Mosseri R, Ingmer H, and Cohen SN (2004) SOS response induction by beta-lactams and bacterial defense against antibiotic lethality. Science 305: 1629–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JH (1972) Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi I, Dagan M, Biran D, and Ron EZ (2007) Potential use of toxic thermolabile proteins to study protein quality control systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 5951–5953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizusawa S, and Gottesman S (1983) Protein degradation in Escherichia coli: the lon gene controls the stability of sulA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80: 358–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira CG, Herrera CM, Needham BD, Parker CT, Libby SJ, Fang FC, Trent MS, and Sperandio V (2013) Virulence and stress-related periplasmic protein (VisP) in bacterial/host associations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 1470–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira CG, Weinshenker D, and Sperandio V (2010) QseC mediates Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium virulence in vitro and in vivo. Infect Immun 78: 914–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, and Young KD (2000) Penicillin binding protein 5 affects cell diameter, contour, and morphology of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 182: 1714–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols RJ, Sen S, Choo YJ, Beltrao P, Zietek M, Chaba R, Lee S, Kazmierczak KM, Lee KJ, Wong A, Shales M, Lovett S, Winkler ME, Krogan NJ, Typas A, and Gross CA (2011) Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell 144: 143–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak EA, Shao H, Daep CA, and Demuth DR (2010) Autoinducer-2 and QseC control biofilm formation and in vivo virulence of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun 78: 2919–2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole GA, and Kolter R (1998) Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 28: 449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoina D (2011) Fever, fever patterns and diseases called ‘fever’--a review. J Infect Public Health 4: 108–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossanna N, and Mount DW (1989) Mutations in uvrD induce the SOS response in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 171: 303–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis-Bleau C, Kritikos G, Orlova K, Typas A, and Bernhardt TG (2014) A genome-wide screen for bacterial envelope biogenesis mutants identifies a novel factor involved in cell wall precursor metabolism. PLoS Genet 10: e1004056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis-Bleau C, Markovski M, Uehara T, Lupoli TJ, Walker S, Kahne DE, and Bernhardt TG (2010) Lipoprotein cofactors located in the outer membrane activate bacterial cell wall polymerases. Cell 143: 1110–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupuleti S, Sule N, Manson MD, and Jayaraman A (2018) Conversion of Norepinephrine to 3,4-Dihdroxymandelic Acid in Escherichia coli Requires the QseBC Quorum-Sensing System and the FeaR Transcription Factor. J Bacteriol 200: e00564–00517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen IB, Helgesen E, Flatten I, Fossum-Raunehaug S, and Skarstad K (2017) SeqA structures behind Escherichia coli replication forks affect replication elongation and restart mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 6471–6485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Capilla T, Baquero MR, Gomez-Gomez JM, Ionel A, Martin S, and Blazquez J (2005) SOS-independent induction of dinB transcription by beta-lactam-mediated inhibition of cell wall synthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 187: 1515–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, Colavin A, Shi H, Czarny TL, Larson MH, Wong S, Hawkins JS, Lu CHS, Koo BM, Marta E, Shiver AL, Whitehead EH, Weissman JS, Brown ED, Qi LS, Huang KC, and Gross CA (2016) A Comprehensive, CRISPR-based Functional Analysis of Essential Genes in Bacteria. Cell 165: 1493–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potluri LP, de Pedro MA, and Young KD (2012) Escherichia coli low-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins help orient septal FtsZ, and their absence leads to asymmetric cell division and branching. Mol Microbiol 84: 203–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail MA, and Guest JR (1995) Purification, characterization and mode of action of PdhR, the transcriptional repressor of the pdhR-aceEF-lpd operon of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 15: 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raden M, Ali SM, Alkhnbashi OS, Busch A, Costa F, Davis JA, Eggenhofer F, Gelhausen R, Georg J, Heyne S, Hiller M, Kundu K, Kleinkauf R, Lott SC, Mohamed MM, Mattheis A, Miladi M, Richter AS, Will S, Wolff J, Wright PR, and Backofen R (2018) Freiburg RNA tools: a central online resource for RNA-focused research and teaching. Nucleic Acids Res 46: W25–W29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivio TL (2014) Everything old is new again: An update on current research on the Cpx envelope stress response. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Cell Research 1843: 1529–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real G, and Henriques AO (2006) Localization of the Bacillus subtilis murB gene within the dcw cluster is important for growth and sporulation. J Bacteriol 188: 1721–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J, and Belasco JG (2019) Obstacles to Scanning by RNase E Govern Bacterial mRNA Lifetimes by Hindering Access to Distal Cleavage Sites. Mol Cell 74: 284–295 e285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick PD, Barr K, Sankaran K, Kajimura J, Rush JS, and Waechter CJ (2003) Evidence that the wzxE gene of Escherichia coli K-12 encodes a protein involved in the transbilayer movement of a trisaccharide-lipid intermediate in the assembly of enterobacterial common antigen. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278: 16534–16542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotman E, Khan SR, Kouzminova E, and Kuzminov A (2014) Replication fork inhibition in seqA mutants of Escherichia coli triggers replication fork breakage. Mol Microbiol 93: 50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage E, Kerff F, Terrak M, Ayala JA, and Charlier P (2008) The penicillin-binding proteins: structure and role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32: 234–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]