Introduction

Locum tenens physician employment arrangements have their supporters and their detractors. Some deride them as a potential “error-producing condition,”1 yet others laud them as an option to reduce or ameliorate physician “burnout,” low patient satisfaction, and disparities in health care access.2

Many views are anecdotal or provided by locum tenens staffing companies. Empirical literature is limited and often methodologically weak.3 Nonetheless, consideration of the seismic shifts in the delivery of healthcare in the last quarter-century in the US requires recognition of the substantial and increasing role that locum tenens physician coverage plays in both community and hospital-based healthcare today. Those considering a locum tenens experience during their medical career might benefit from the advice of Malcolm Gladwell: “Truly successful decision-making relies on a balance between deliberate and instinctive thinking.” Whether you are considering hiring locum tenens physicians within your practice or seeking such employment yourself, what follows aspires to assist you as you make your deliberations.

Historical Context

Merriam-Webster defines locum tenens as “one filling an office for a time or temporarily taking the place of another.”4 Locum tenens became a healthcare delivery model in the 1970s initially to address rural physician burnout in Utah. With funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Health System Research Institute at the University of Utah College of Medicine created a network of physicians who covered rural practices while the rural physicians accessed continuing education. One of the two physician founders of locum tenens, Alan Kronhaus, recounted that the scheduling of his locum tenens shifts allowed him to nurture mutual passions of patient care and skiing, with six-month stints of each.5

While features of the original model persist, locum tenens as a healthcare delivery model has grown and advanced dramatically in ensuing decades. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2023 that 50,000 doctors, or 7% of the US physician workforce not including foreign medical-school graduates, currently practice medicine via temporary assignments.6 Nearly 10,000 physician locum tenens jobs are listed with one agency alone, with specialties ranging from family practice, emergency medicine and hospital medicine to transplant surgery, interventional radiology and hospice and palliative care.7 As reported by Staffing Industry Analysts in “Largest Healthcare Staffing Firms in the US: 2019 Update,” 49 staffing firms generated at least $50 million each in US healthcare staffing revenue in 2018. Together, these firms generated an estimated $12.7 billion in revenue and comprised 75% of the market.8

Characteristics of the Locum Tenens Workforce

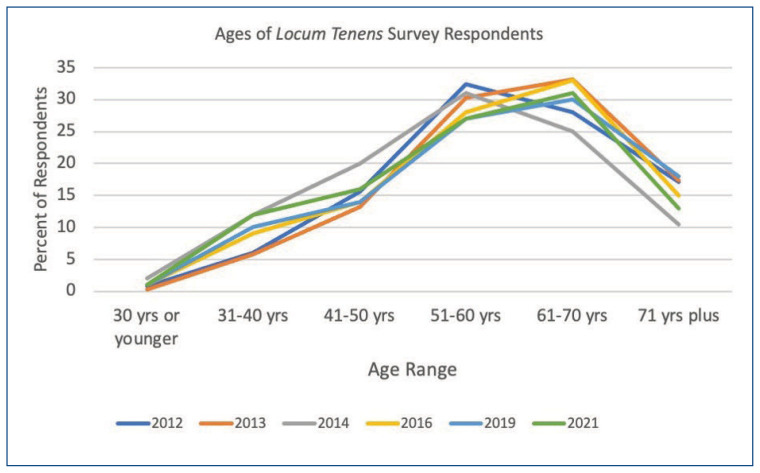

A 2017 survey of 897 locum tenens physicians was performed by Staff Care for the purpose of characterizing their physician workforce. Approximately 60% were medical specialists.9 Close to half, 48%, were 61 years or older and three-quarters were 51 years or older. Sixty-five percent had been in practice for at least 21 years. Nine of ten physicians surveyed had worked in permanent practice at some point during their careers. As illustrated in Figure 1, the age ranges of locum tenens physicians responding to a staffing company survey has varied little over the last decade. Approximately half of those surveyed reported that they began working as a locum tenens physician during the middle of their careers, while 36% started taking locum tenens positions after retiring from permanent practice. The most common factors influencing respondents’ decisions about which locum tenens positions to take were location (89%), pay rate (67%), length of assignment (60%), and patient load (38%).10 See Figure 1.11,12

Figure 1.

Formed as a response to standardize locum tenens services, the National Association of Locum Tenens Organizations, NALTO, was established in 2001 to both create and enforce strong industry standards for the profession, stressing honesty, objectivity, integrity, and competency. Best practice guidelines primarily address contractual expectations, dispute resolution, and documentation of communications rather than delving into potentially controversial matters regarding clinical practice. As NALTO’s Board of Directors are affiliated primarily with staffing organizations and lack physician representation, development of organizations promoting the interests and perspectives of locum tenens physicians is warranted.13

Quality of Locum Tenens Care

Few studies exist to support or refute the quality of care delivered by physicians working in locum tenens positions. Some have attributed prescribing errors to locum tenens staff,14 ascribed in part to a lack of familiarity among locum tenens physicians with local teams, processes, practices, and guidelines. In England, locum tenens physicians are more likely to be the subject of complaints, more likely to have those complaints subsequently investigated and more likely to receive sanctions, although the reasons behind such complaints are neither well-documented nor understood.15 The General Medical Council reviewing such complaints concluded: “Doctors who act solely as locums or work for locum agencies have a greater risk of being complained about, and complaints about them are more likely to reach the threshold for a full investigation. A wider discussion is essential to understand the root causes of this and to explore whether further professional and workplace support for locums can reduce the risk to patients.”16

An assessment of the quality and cost of neurosurgical care between locum tenens and non-locum tenens neurosurgeons in the US reviewed 2005–2011 Medicare claims data and found no difference in short-term complication rates, lengths of stay, or costs between locum tenens and non-locum tenens neurosurgeons.17

A 2020 prospective cohort study compared treatment by 22 employed hospitalists and 24 locum tenens hospitalists at Promedica Toledo Hospital in Ohio. Primary outcome was adjusted length-of-stay and secondary outcomes were hospital cost, inpatient mortality, 30-day all-cause readmission, and 30-day mortality. Patients treated by locum tenens hospitalists had one-day shorter length-of-stay and $1,339 decreased hospital costs but no statistically significant difference in mortality or readmissions.18

In another large retrospective study, researchers at Harvard University, Columbia University, UCLA and the National Bureau of Economic Research analyzed national Medicare data to characterize locum tenens physicians’ patterns, quality and costs of care relative to non-locum tenens physicians. Randomizing a sample of 1,818,873 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized and treated by a general internist during 2009–2014, 38,475 of them (2.1%) received care from a locum tenens physician. In addition, 9.3% (4,123/44,520) of general internists were temporarily covered by a locum tenens physician at some point. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included inpatient Medicare Part B spending, length-of-stay, and 30-day readmissions. In this retrospective cohort analysis, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality among patients treated by locum tenens physicians compared with those treated by non–locum tenens physicians (8.83% vs 8.70%). Regarding secondary outcomes, patients treated by locum tenens physicians had significantly higher adjusted total Part B charges ($1,836 vs $1,712), longer length-of-stay, (5.64 days vs 5.21 days), and significantly lower readmission rates (22.80% vs 23.83%) than patients treated by non–locum tenens physicians.19

Based on our review of the literature, data with which to compare quality indictors between locum tenens and non-locum tenens physicians is limited and conflicting. Further, results may differ based on the specialty of care. Do results in general internal medicine translate to emergency medicine, anesthesiology, or critical care? The use of locum tenens, at a minimum, may impact patient outcomes, nursing and other healthcare team members’ satisfaction and wellbeing, hospital financial margins, and the community mission of hospitals. Studies to better inform decisions regarding the use of locum tenens are needed. Aside from mortality data and cost analyses, comparison of the satisfaction of patients, nurses, other physicians, and all healthcare team members who works side-by-side with locum tenens physicians is warranted. Finally, additional data is needed to inform physicians as to the pros and cons of locum tenens work at various stages of one’s career.

Pros and Cons of Locum Tenens

From a physician perspective, potential benefits of locum tenens work could include greater scheduling flexibility, reduced administrative burdens, enhanced pay, and opportunity for social and cultural experiences in multiple locales. Disadvantages include the need to secure hospital credentials for each facility of employment and a state medical license for assignments outside one’s primary state of practice. In addition, credentialling for clinical privileges at many hospitals requires a detailed chronology of prior work experiences, possibly supported by identification of professional references for care rendered. The “paper trail” of locum tenens positions could become progressively cumbersome depending on the number and duration of assignments.

As independent contractors, locum tenens physicians are responsible for filing their own taxes and securing those “fringe” benefits typically provided by an employer, including life insurance, disability, health insurance, and retirement plans.20 Some locum tenens physicians choose to incorporate to reduce taxation and limit liability. While the hourly wage might be higher for locum tenens work, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that total benefits for employed workers in the ninetieth wage percentile constitute 37% of their total compensation, a factor to deliberate when considering high locum tenens pay sans benefits.21 Professional liability insurance, whether claims with a tail or occurrence, traditionally is the responsibility of the locum tenens company. Should “tail” coverage become problematic, costs could be prohibitive. Simply acquiring retrospective “tail” coverage as an independent contractor might be unfeasible. Paid vacation, sick, personal, and holiday leave are not provided. While anecdotal, some physicians pursuing locum tenens work during the COVID pandemic found themselves unemployed once staffing needs were reduced, facing long stretches of unplanned and unpaid sabbatical.

Recommendation for Locum Tenens

If considering contracting physicians for temporary clinical coverage, locum tenens remains a viable option. Both the physician workforce and the corporations arranging and securing such coverage have improved substantially over the last half-century. While empiric evidence evaluating locum tenens is limited, two cohort studies noted above identified no significant difference in 30-day mortality between care provided by locum tenens and non-locum tenens physicians.

If contemplating ongoing work as a locum tenens physician, we believe the role remains best suited for those later in their career when approaching retirement, as a post-retirement clinical activity or perhaps as a sabbatical earlier in one’s career. While the professional benefits secured through traditional employment ultimately can be established by an independent contractor pursuing full-time locum tenens work, the hassles of doing so can be substantial. In addition, the financial impact of unexpected unemployment, whether from an injury, illness, or pandemic, can be devastating. Many recognize such drawbacks. While media reports suggest “gig work” has become increasingly popular among younger physicians,22 survey results of practicing locum physicians suggest otherwise.23,24

Lifestyle benefits of locum tenens employment certainly exist for younger physicians desiring clinical practice without an ongoing commitment to a locale, schedule, colleagues, hospital, or patient population. This must be weighed against the advantages of a less itinerant practice, which include not only the employment benefits packages noted above, but also the satisfaction of enduring relationships with patients and colleagues, a sense of building and maintaining a core clinical practice, and the opportunity to branch out in other medical pursuits such as health policy, education, and research. While most of this manuscript’s authors have grayed to some degree, all readily recall early career frustrations: a sense of under-appreciation, lack of fulfillment, few options for advancement, and ultimately, self-doubt. Not limited to the practice of medicine, others have noted that “No one is immune from frustration, but the savviest people understand it’s an essential part of success.”25 Most of us who have chosen the more traditional path for our medical career have successfully pursued a diversity of interests beyond our core clinical practice. Given time, opportunity eventually knocks, sometimes repeatedly.

Footnotes

Randy Jotte, MD, (pictured) and Larry Lewis, MD, are Professors of Emergency Medicine and are at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri. Gary Gaddis, MD, is Professor of Biomedical and Health Informatics, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine and Volunteer Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of California-Irvine School of Medicine. Evan Schwarz, MD, is an Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles California.

References

- 1.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002 Apr 20;359(9315):1373–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A prologue to locum tenens, locumstory.com. CHG Healthcare. [accessed June 21, 2023]. https://locumstory.com/story .

- 3.Ferguson J, Walshe K. The quality and safety of locum doctors: a narrative review. J R Soc Med. 2019 Nov;112(11):462–471. doi: 10.1177/0141076819877539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locum tenens. Merriam-Webster.com 2023. Jun 23, 2023. https://www.merriamwebster.com .

- 5.A history of locum tenens: the origins of a new approach to healthcare. CompHealth A CHG Company; Aug 13, 2017. https://comphealth.com/resources/the-origin-of-locum-tenens . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarrant Gretchen. Burned Out, Doctors Turn to Temp Work: A growing group of physicians are ditching medicine’s traditional career path and hitting the road as temporary doctors-for-hire”. The Wall Street Journal. [New York, NY] 2023 June 6; [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jobs. CompHealth. A CHG Company; [Accessed June 21, 2023]. https://comphealth.com/jobs/physician . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healthcare Staffing Report: October 10, 2019. Largest US Healthcare Staffing Firms List Includes 49 Firms: SIA Staffing Industry Analysts. Oct 9, 2019. https://www2.staffingindustry.com/Editorial/Healthcare-Staffing-Report/Archive-Healthcare-Staffing-Report/2019/Oct.-10-2019/Largest-US-healthcare-staffing-firms-list-includes-49-firms-SIA#:~:text=October%209%2C%202019&text=AMN%20Healthcare%20Services%20Inc.,the%20fourth%20quarter%20of%202017 .

- 9.Staff Care. An AMN Healthcare Company; [Accessed June 22, 2013]. White Paper Series: Locum Tenens and the Emerging Shortage of Medical Specialists. https://www.staffcare.com/siteassets/resources/thought-leadership/white-paper-locum-tenens-and-emerging-shortage-of-medical-specialists.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumenthal DM, Tsugawa Y, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Substitute Doctors Are Becoming More Common. What Do We Know About their Quality of Care? Harvard Business Review. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Survey of Temporary Physician Staffing Rents Staff Care. An AMN Healthcare Company; 2017. [Accessed June 23, 2023]. https://www.staffcare.com/siteassets/resources/thought-leadership/2017-survey-temporaryphysician-staffing-trends.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Survey of Locum Tenens Physicians and Advanced Practitioners Staff Care. An AMN Healthcare Company; 2021. [Accessed June 23, 2023]. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn-insights/physician/surveys/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Best Practice Guidelines NALTO The National Association of Locum Tenens Organizations. [Accessed June 22, 2023]. https://www.nalto.org/bestpractice-guidelines/

- 14.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002 Apr 20;359(9315):1373–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson J, Walshe K. The quality and safety of locum doctors: a narrative review. J R Soc Med. 2019 Nov;112(11):462–471. doi: 10.1177/0141076819877539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Medical Council. What Our Data Tells Us about Locum Doctors. Manchester: General Medical Council; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiu RG, Nunna RS, Siddiqui N, Khalid SI, Behbahani M, Mehta AI. Locum Tenens Neurosurgery in the United States: A Medicare Claims Analysis of Outcomes, Complications, and Cost of Care. World Neurosurg. 2020 Oct;142:e210–e214. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.06.169. Epub 2020 Jun 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustafa Ali MK, Sabha MM, Mustafa SK, Banifadel M, Ghazaleh S, Aburayyan KM, Ghanim MT, Awad MT, Gekonde DN, Ambati AR, Ramahi A, Elzanaty AM, Nesheiwat Z, Shastri PM, Al-Sarie M, McGready J. Hospitalization and Post-hospitalization Outcomes Among Teaching Internal Medicine, Employed Hospitalist, and Locum Tenens Hospitalist Services in a Tertiary Center: a Prospective Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 Oct;36(10):3040–3051. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06578-4. 2021 Jan 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumenthal DM, Olenski AR, Tsugawa Y, Jena AB. Association Between Treatment by Locum Tenens Internal Medicine Physicians and 30-Day Mortality Among Hospitalized Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA. 2017;318(21):2119–2129. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The pros and cons of locum tenens. Weatherby Healthcare A CHG Company. [Accessed June 23, 2023]. https://weatherbyhealthcare.com/blog/pros-and-cons-of-locum-tenens .

- 21.Employer Costs for Employee Compensation – March 2023. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor; Jun 16, 2023. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ecec.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarrant Gretchen. Burned Out, Doctors Turn to Temp Work: A growing group of physicians are ditching medicine’s traditional career path and hitting the road as temporary doctors-for-hire”. The Wall Street Journal [New York, NY] 2023 June 6; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Survey of Temporary Physician Staffing Rents Staff Care. An AMN Healthcare Company; 2017. [Accessed June 23, 2023]. https://www.staffcare.com/siteassets/resources/thought-leadership/2017-survey-temporaryphysician-staffing-trends.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 24.Survey of Locum Tenens Physicians and Advanced Practitioners Staff Care. An AMN Healthcare Company; 2021. [Accessed June 23, 2023]. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn-insights/physician/surveys/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blaschka A. 4 Sneaky Ways Frustration Can Help You make Career. Progress Forbes. Sep 9, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyblaschka/2022/09/09/4-sneaky-ways-frustration-can-help-you-makecareer-progress/?sh=6a21f972be6e .