Abstract

The natural phenolic compound ellagic acid exerts anti-cancer effects, including activity against colorectal cancer (CRC). Previously, we reported that ellagic acid can inhibit the proliferation of CRC, and can induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. This study investigated ellagic acid-mediated anticancer effects using the human colon cancer HCT-116 cell line. After 72 h of ellagic acid treatment, a total of 206 long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) with differential expression greater than 1.5-fold were identified (115 down-regulated and 91 up-regulated). Furthermore, the co-expression network analysis of differentially expressed lncRNA and mRNA showed that differential expressed lncRNA might be the target of ellagic acid activity in inhibiting CRC.

Keywords: colorectal carcinoma, ellagic acid, long noncoding RNA, mRNA

Introduction

Among the most prevalent tumor types, colorectal cancer (CRC) has become a common cancer with the third highest morbidity and mortality in the world, while the number of cancer-incurred deaths due to CRC is in second place worldwide [1]. The core mechanism of CRC involves a multi-step disease. This process includes the gradual accumulation and interaction of multiple factors such as the microenvironment and genetic changes [2]. Hence, the application of more advanced drugs targeting novel targets will enhance the current success rate of CRC treatment [3]. However, successful drug development is hampered because there is a certain gap in the understanding and cognition of the molecular mechanisms involved in CRC development and progression, which also leads to an unsatisfactory prognosis for many patients. Thus, it is crucial to further investigate the molecular activities associated with CRC, with the aim to facilitate the discovery of novel therapeutic targets.

High-throughput sequencing analysis of transcriptomes and genomes has revealed that less than 2% of the genome encodes proteins, while no less than 75% of genes will be actively transcribed by noncoding RNA (ncRNA) [4,5]. Based on the above, the core of the research effort to date is based on 2% protein-coding genes, which indicates that the results are not fully representative of the disease nor do they fully reflect the core mechanisms involved in carcinogenesis [6,7]. Thus, the identified mechanisms to date may not be the only biological reference markers in clinical practice. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are nonprotein-coding transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides. Numerous complex mechanisms are involved in their activity, which also suggests there are numerous potential implications for lncRNAs in different stages of carcinogenesis and progression [8,9]. Currently, lncRNAs are considered a core regulatory component of tumor development and metastasis and have been attributed roles involving the regulation of chromatin organization before and after gene transcription [10–13]. Furthermore, the subcellular localization of lncRNAs is also very important in determining their function [5].

Through many studies at this stage, it can be concluded that the abnormal expression of lncRNAs is associated with tumor growth, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation in CRC, which also indicates that these lncRNAs can be used as new molecular markers for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment [9,14–18]. However, whether lncRNAs inhibit the growth of tumor cells via anti-tumor agents still needs to be further explored.

Chemoprevention is a realistic and effective treatment strategy against cancer [19]. Ellagic acid [2,3,7,8-tetrahydroxy-chromeno (5,4,3-cde) chromene-5,10-dione; International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry], is a polyphenol found in woody plants and fruits including nuts, grapes, and berries [20], and is regarded as a potential chemo-preventive agent, inhibiting proliferation in a variety of cancer types [20,21]. Previous research findings from in-vitro and in-vivo tests have indicated that ellagic acid exhibits remarkable inhibitory effects against CRC, suggesting it has an effective anti-tumor role against CRC [22–24]. However, the molecular activities relevant to the cellular responses induced by ellagic acid, especially their regulatory mechanisms in transcription and protein interaction, have not been investigated in depth. Moreover, previous studies have never tested the relevant lncRNA targets. Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the lncRNA targets of ellagic acid able to inhibit the growth of HCT-116 CRC cells, accordingly providing a theoretical basis for precision therapy in CRC.

In our previous studies using microarray analysis using the AffymetrixGeneChip Human Transcriptome Array 2.0 (HTA; Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, California, USA), we observed that treatment with ellagic acid not only inhibited CRC cell proliferation but also was accompanied by significantly changed expression levels of 857 genes (494 genes down-regulated, 363 genes up-regulated) after 72 h of treatment, with minimum 1.5-fold change in expression [25,26]. Furthermore, we also obtained data on differentially expressed lncRNAs from the microarray analysis. As a part of the follow-up to that project, this study verified that ellagic acid could inhibit the growth of HCT-116 CRC cells by regulating lncRNA targets, which in turn influenced the expression of their mRNA targets.

Materials and methods

RNA preparation and microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from HCT116 cells (from ATCC cell bank) using the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). Cells were treated with ellagic acid or four independent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and then treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) before further processing. The integrity of RNA is assessed by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. The Affymetrix HTA Gene Chip (Affymetrix, Inc.) was used to study and analyze the global expression profile of human lncRNA and protein-coding transcripts of HCT116 cells [25]. In this microarray, 26 816 coding transcripts and 39 128 lncRNAs were included [25]. Using random primers, each sample was amplified together with the full length of the transcript and then transcribed to cRNA using fluorescent markers without 3′ bias. Heat maps and unsupervised hierarchical clustering were performed based on the relative expression levels using the Cluster-Treeview program: Affymetrix.

Categories of long noncoding RNA

The type of lncRNA determined its genomic location relative to the coding gene [27–29]. The categories were defined as sense, intergenic, antisense, and bidirectional lncRNA. If the lncRNA exon and the coding transcript exon on the same genome chain overlapped to a certain extent, then a sense lncRNA was defined. Bidirectional lncRNA was identified when the entire lncRNA sequence was within 1000 bp of the coding transcript. The antisense lncRNA overlaps with the antisense coding transcript. Intergenic lncRNA indicates that there is no bidirectional coding transcript or overlap around annotated coding genes.

Gene Ontology analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis

Standard Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment and Gene Ontology annotation analysis were performed to determine the core function of the closest genes preferentially associated with lncRNA expression. The category of Gene Ontology is derived from Gene Ontology. Gene Ontology covers a three-level structured network, and its defined terms describe the specific attributes of gene products [30]. Fisher’s test was mainly to compare statistically significant associations. The P value indicates the importance of Gene Ontology enrichment category identified for the differentially expressed lncRNA/gene list. The objective of pathway analysis is to identify the potential functional role of differentially expressed coding genes using the most recent database of known KEGG pathways, and the results of pathway analysis were subsequently used to determine the role of differentially expressed lncRNAs. Further combination with Gene Ontology analysis was used to analyze the mutual influence and effects of lncRNAs and coding genes resulting from the ellagic acid-induced apoptosis of HCT116 cells [31].

Analysis of the long noncoding RNA–gene network

The Gminix-Cloud Biotechnology Information online laboratory uses differential lncRNA and differential gene expression characteristics to establish a potential lncRNA and gene network. This network allows to define the relationship and underlying mechanisms between differentially expressed genes and lncRNA. This network absorbs the scale-free characteristics of large amounts of data and relies on the effects of genes and lncRNAs to achieve a simulation of the scale-free relationship. For analytical purposes, we optimally selected no less than 200 genes and no less than 30 lncRNAs.

The analysis method for clustering genes and lncRNA networks includes the following steps: the expression profiles of differential lncRNA and differential genes are input and through pairwise correlations, a contingency matrix is established for each pair identified. Subsequently, for each hub gene (lncRNA or gene), the degree of connectivity and the adjacency matrix (aij) of each pair is obtained. For each cluster (a β value is selected from 1 to 30), linear regression is performed on log(k) and log(p(k)), to linearly transform the two equations and yield a slope that is approximately −1. The average value cannot be too low. Calculation of the difference between any two nodes is used as the distance to define the hybrid hierarchical clustering algorithm to achieve several central nodes and modules for the dendrogram.

Each cluster reflects multiple subgroups of nodes that share a close relationship and serves to represent the functions and individual interactions more accurately. Not only that, when the expression data set does not meet the conditions required for the scale-free analysis, then the threshold α is selected, and the adjacency matrix (aij) is obtained together with the similarity coefficient matrix (sij):

Here ‘I’ is an indication function: it is 1 when otherwise it is given a value of 0. Next, we derive the adjacency matrix, whose elements are 0 or 1, and the network graph can be generated based on these values: two nodes i and j are connected if and only if . The threshold must be carefully selected so that the dendrogram can show the main relationships between nodes, and the average strength of interaction should not be too low.

Real-time reverse transcription analysis

After 72 h of treatment with ellagic acid (E2250, purity ≥ 95%; Sigma) or negative control, TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and RNeasy reagent kit (Qiagen, Germany) were used to obtain total RNA. Subsequently, the purity and integrity of ribosomal RNA were evaluated [25,26].

Total RNA from HCT-116 cells receiving a 72-h treatment with ellagic acid (100 µM, an optimal concentration of ellagic acid determined from our previous report [25]) was used for transcriptomics analysis of selected target genes using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). RNA (2 µg) was reversely transcribed to cDNA using the Super Script II reverse transcriptase kit (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and oligo (dT) primers. Specific primers (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) used for the reactions are listed in Table 1 and the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to perform RT-qPCR. The data analysis was based on the comparative or ΔΔCt method. The normalization of results was achieved using β-actin levels as the reference gene [25,26].

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences used in the quantitative real-time real-time-PCR

| Primer name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| GAPDH | CTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGGACTC |

| CAGTAGAGGCAGGGATGATGTT | |

| DDX11-AS1 | ATCCCACCCTGCCTTTGATG |

| AACGGGGCTGAAGCTCTAAC | |

| LINC00152 | CACCCCTTGTGGGTTCAGAG |

| TGGTTTATTCTTGCCGGGGT | |

| LINC00622 | AGGCAAGTGGGTTTGAAGCA |

| CACTCTAGGTCTTGCCCTCC | |

| LUCAT1 | TTCTGGGCAGGACAGTTGTG |

| ATCCTTGAGGTGCTCGCTTC | |

| UCA1 | GCCAGCCTCAGCTTAATCCA |

| CCCTGTTGCTAAGCCGATGA |

RT-PCR, real-time PCR.

Bioinformatics analysis

The sequence conservation of lncRNA and its related protein-coding genes was determined using the University of California Santa Cruz genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and other available databases therein. LncRNA considered in the analysis included: bidirectional lncRNA, promoter-associated lncRNA, intronic lncRNA, and cis- and antisense lncRNA. During the analysis, various epigenetic phenomena were incorporated to facilitate the identification of noncoding regulatory elements.

Statistical analysis

Volcano plot filtering was used to identify statistically significant differentially expressed mRNA and lncRNA. The threshold fold change for up-regulation and down-regulation of gene expression was set at ≥1.5 (P value ≤ 0.05). Values were expressed by mean ± SE and by GraphPad Prism version 5.0, USA was used for all statistical analysis. The Student’s test was used to compare the differences in the means between the two groups. A P value of <0.05 represents acceptable significance.

Results

Global profiling of long noncoding RNA and coding genes in ellagic acid-treated HCT116 cells

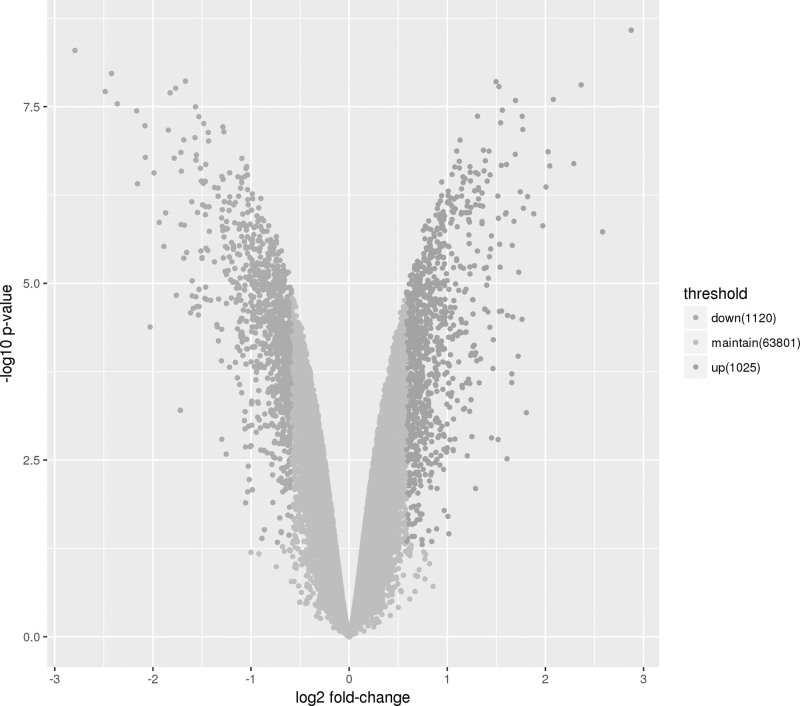

In previous studies, it was found that 100 μM ellagic acid could effectively reduce the proliferation of HCT116 cells by 50% within 72 h [25,26]. We used similar treatment conditions (dose and time) for the HCT116 cell line in the microarray analysis covering 26 816 coding transcripts and 39 128 lncRNAs. We verified whether the coding gene and expression profile of lncRNA could be used to define the role played by lncRNA in the growth of CRC cells exposed to ellagic acid. The Volcano plot is shown in Fig. 1. Total RNA from four independent experiments of DMSO or ellagic acid-treated HCT116 cell (24 h) was isolated to study gene expression using the Human LncRNA Microarray V2.0. Volcano Plot analysis of the microarray chip data on the differentially expressed lncRNA between the ellagic acid treated and control group. The vertical green lines correspond to a 1.5-fold up- and down-regulation while the horizontal green line represents a P value of 0.05. The data showed that 74.24% of coding genes and 52.32% of ncRNA were expressed above background levels (Table 2). Volcano maps are important tools used to visualize the differential gene expression patterns between two different conditions. Herein, we used Volcano plot analysis to compare the control group and the ellagic acid treatment group. The findings showed that 2.98% (959) of coding genes and 2.46% (961) of ncRNA were significantly expressed following treatment with ellagic acid (Table 2). Next, a hierarchical cluster analysis method was adopted to analyze gene expression patterns associated with the proliferation of HCT116 cells in response to ellagic acid treatment. The findings showed the lncRNA expression profile between the control group and the ellagic acid treatment group differed significantly (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

Profiling of ellagic acid-regulated lncRNA and coding RNA. The red dots to the left and to the right of the vertical green lines indicate more than a 1.5-fold change. Statistical significance was defined as fold change ≥1.5 and P value ≤ 0.05 between ellagic acid-treated and control (DMSO) groups. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA.

Table 2.

Summary of microarray data

| Probe class | Total | Expressed above background | Differentially expressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coding expression | 26 816 | 19 371 (72.24%) | 959 (2.98%) |

| Noncoding expression | 39 128 | 20 473 (52.32%) | 961 (2.46%) |

Statistically significant differentially expressed long noncoding RNA and mRNA from the Volcano plot filtering having fold change ≥1.5 (P value ≤0.05).

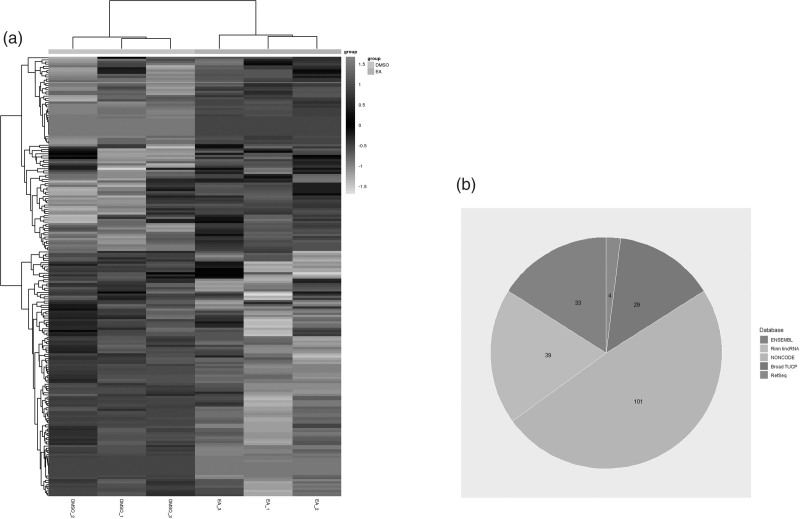

Fig. 2.

LncRNA from DMSO- and ellagic acid-treated HCT116 cells. (a) Heat map presentation of the expression profile of lncRNA. Each column represents a sample and each row represents a gene. Three independent experiments for each DMSO and ellagic acid-treatment group. (b) The category and distribution of the differentially expressed lncRNA in DMSO- and ellagic acid-treated HCT116 cells. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA.

Differentially expressed lncRNAs and interacting coding genes in ellagic acid-treated proliferating HCT116 cells

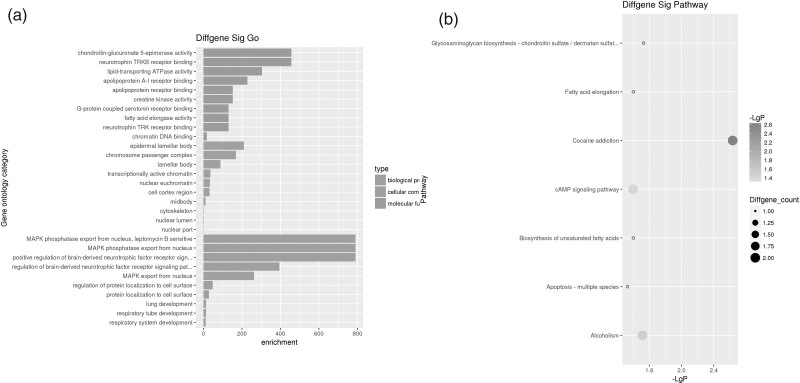

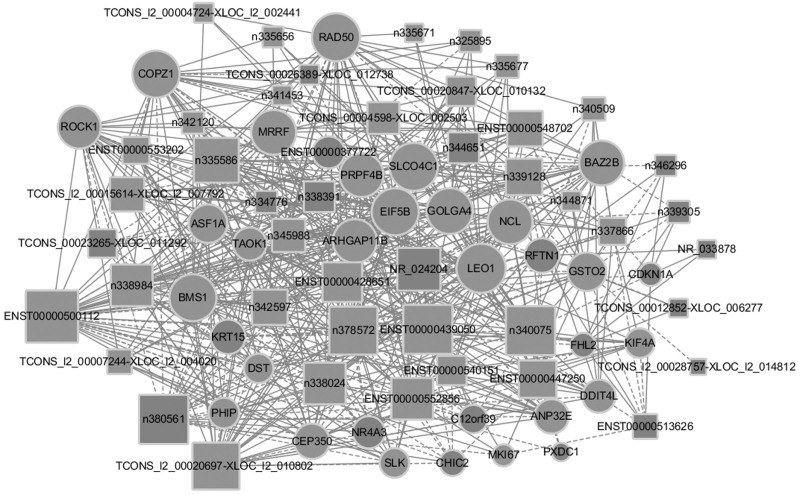

Further analysis of 206 of the 961 differentially expressed ncRNAs following exposure to ellagic acid were lncRNA, were identified using different databases (Fig. 2b). The co-expression of coding genes and lncRNA pairs was evaluated by Fisher’s exact test adjusted by Bonferroni corrections for multiple tests. If the P value was <0.01 and was within a given percentile, the gene expression was considered a co-expression. For a more in-depth analysis of the functional interactions, two Gene Ontology analyses were performed. The first mainly linked a coding gene with no less than three lncRNAs (Fig. 3a), and vice versa the other analysis mainly connected one lncRNAs with no less than three coding genes (Fig. 3b). The bar graph shows the top 10 enrichment score values of significantly enriched molecular function items. Gene Ontology analysis of co-expressed coding genes and lncRNA found that genes with cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor activity, oxidoreductase activity, and catalytic activity were preferentially enriched. The co-expressed lncRNA genes whose expression level was greater than two-fold were selected for Gene Ontology analysis. Co-expression networks of differentially lncRNAs and closely related mRNAs were also constructed to determine whether the differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs were involved in a potential interactive mechanism (Fig. 4). Table 3 lists the top 10 differentially expressed lncRNAs. The expression levels of n335183, n340042, n326000, n335586, and TCONS_00004331-XLOC_002204 increased significantly, and were highly up-regulated genes in ellagic acid-treated CRC HTC116 cells, while NR_003706, NR_002983, NR_002971, n383862, and n341216 decreased significantly. Further comparison and analysis of gene expression changes induced by ellagic acid were performed using RT-qPCR to confirm the microarray data. Differential expression of the selected known lncRNAs was consistent with the microarray data shown in Table 4. Based on the lncRNA-mRNA Co-expression network, we found five regulated functional target genes [CDKN1A, kinesin family member 4A (KIF4A), anti-silencing function 1A (ASF1A), nucleolin, and rho-related coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1 (ROCK1)] shown in Table 5.

Fig. 3.

Gene Ontology analysis of lncRNA-associated with coding genes. (a) Gene Ontology analysis of coding genes in which one coding gene is associated with at least three lncRNA. The top 10 significantly enriched molecular functions along with their scores are listed on the x-axis and the y-axis, respectively. (b) KEGG pathway analysis of coding genes in which one lncRNA is connected to at least three mRNAs. The size of the dots indicates the number of enriched PCGs; the color of the dots represents the degree of significance based on the P value. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA; PCGs; protein-coding genes.

Fig. 4.

Co-expression network of DE lncRNA and differentially expressed mRNA. The squares represent lncRNA, the circles represent mRNA, the size of the shape represents the weighted value, red indicates up-regulation, and blue indicates down-regulation. lncRNA, long noncoding RNA.

Table 3.

Relative changes in expression (ratio treated/control cells) of selected top 10 long noncoding RNAs from HCT-116 cells after a 72-h exposure to ellagic acid

| Probe set ID | Gene symbol | Accession number | Fold change | P value | Gene feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC04002654.hg.1 | n335183 | −5.6161 | 2.5E-05 | Down | |

| TC17000796.hg.1 | SNORA38B | NR_003706 | 5.16439 | 2.7E-05 | Up |

| TC10002092.hg.1 | n340042 | −5.1424 | 3.4E-05 | Down | |

| TC01002542.hg.1 | SNORA55 | NR_002983 | 4.88078 | 5.8E-05 | Up |

| TC10002570.hg.1 | n326000 | −4.4784 | 7.7E-05 | Down | |

| TC15002176.hg.1 | n335586 | −4.2177 | 5.6E-05 | Down | |

| TC06000375.hg.1 | SNORA38 | NR_002971 | 4.08637 | 4.6E-05 | Up |

| TC02004404.hg.1 | TCONS_00004331-XLOC_002204 | −4.0827 | 0.00038 | Down | |

| TC20001451.hg.1 | n383862 | 4.02566 | 8.4E-05 | Up | |

| TC07002222.hg.1 | n341216 | 3.95474 | 0.00012 | Up |

Table 4.

Microarray data further confirmed by real-time PCR

| Probe set ID | Gene symbol | Accession number | Fold change (microarray) | P value (microarray) | Gene feature | Fold change (RT-PCR) | P value | Biotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC12001357.hg.1 | DDX11-AS1 | NR_038927 | 1.670157 | 0.001406 | Up | 2.32975 | 0.008 | Noncoding |

| TC19000279.hg.1 | UCA1 | NR_015379 | −1.568326 | 0.002406 | Down | -2.67832 | 0.013 | Noncoding |

| TC05001589.hg.1 | LUCAT1 | ENST00000513626 | 2.728864 | 0.000221 | Up | 4.32565 | 0.006 | Noncoding |

| TC02000535.hg.1 | LINC00152 | NR_024204 | 2.496151 | 0.000117 | Up | 3.25688 | 0.011 | Noncoding |

| TC01003048.hg.1 | LINC00622 | NR_036540 | 2.478382 | 0.000942 | Up | 3.28961 | 0.007 | Noncoding |

Long noncoding RNA expression level was normalized to the mRNA levels of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. The data shown indicate relative fold induction (ellagic acid vs. dimethyl sulfoxide treatment) after a 72-h exposure. Relative changes in expression (ratio treated/control cells) of 5 selected long noncoding RNAs in HCT-116 cells after a 72-h exposure to ellagic acid as identified by Affymetrix microarray and validated by real-time PCR.

RT-PCR, real-time PCR.

Table 5.

Crucial long noncoding RNAs and their mRNAs involved in the network

| mRNA | Gene feature | lncRNA | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIF4A | Down | n335586 | Positive |

| n340075 | |||

| ASF1A | Down | ENST00000548702 | Positive |

| n335586 | |||

| n340075 | |||

| n342597 | |||

| Nucleolin | Down | ENST00000548702 | Positive |

| n335586 | |||

| n340075 | |||

| n342597 | |||

| ROCK1 | Down | ENST00000548702 | Positive |

| n335586 | |||

| n340075 | |||

| n342597 |

ASF1A, anti-silencing function 1A; KIF4A, kinesin family member 4A; lncRNA, long noncoding RNA; ROCK1, rho-related coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1.

Discussion

CRC is a devastating malignant disease, ranking fifth and second among the most common causes of death from cancer in China [32] and western countries [33], respectively. Although effective therapeutic strategies have been developed in previous decades, the 5-year overall survival of CRC patients remains unsatisfactory, owing to the limited number of currently adopted prognostic factors (e.g. vascular and neural invasion, a low lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, and tumor stage III/IV) [3]. Chemo-prevention is an effective method for the inhibition of cancer cell growth. However, our understanding of CRC pathogenesis remained limited. Thus, it was crucial to further investigate the molecular activities associated with CRC, with the aim of identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Ellagic acid is considered a potential chemo-preventive agent given its capacity to inhibit the proliferation of various types of cancer [34]. Based on in-vitro and in-vivo experiments, ellagic acid has been reported to cause a remarkable delay in CRC progression, suggesting that ellagic acid might exert an anti-tumor role in CRC [35,36]. However, the relevant molecular pathways determining the cellular response to ellagic acid, especially those related to transcriptional regulation and protein production, have not been clarified in detail. Therefore, it is clinically relevant to determine the molecular mechanisms and targets of ellagic acid-induced inhibition of growth in HCT-116 CRC cells. Although most studies have suggested the involvement of target genes in this process, few have investigated the role of lncRNAs.

Generally, high-throughput microarray technology has been used to search for differentially expressed lncRNAs using tissue samples and cell lines. Zhou et al. [37] adopted this method to study differences in mRNA and lncRNA expression profiles between hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues, and analyzed the significantly dysregulated genes [38–40].

We used microarray analysis to systematically analyze and study the underlying mechanism of genes and pathways of ellagic acid-induced inhibition of HCT-116 CRC cell proliferation [25]. Meanwhile, in our previous study, microarray analysis showed that, after a 72-h exposure to ellagic acid treatment, a total of 4738 genes exhibited an over 1.2-fold change in expression levels [25]. The findings of the current study demonstrated that the ellagic acid-treated HCT-116 was arrested in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, and thereby led to cell apoptosis.

Accordingly, the regulatory function of ellagic acid on the lncRNA expression in CRC cells suggests these may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for CRC. Further research is warranted to better understand the potential clinical application of ellagic acid in cancer therapy.

It has been reported that multiple lncRNAs may be involved in carcinogenesis ability or act as tumor suppressor genes [41–43]. Although the changes in lncRNA expression levels are associated with the development of CRC, the molecular mechanisms involved still require further study. Many studies have shown that there is a great correlation between lncRNA expression and CRC. Furthermore, our novel findings show that exposure to ellagic acid changes the expression of many coding RNAs and lncRNAs. These differentially expressed lncRNA may be the target of ellagic acid-inhibition of CRC cell proliferation.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the regulation of protein-coding gene changes in multiple cancer cells treated with ellagic acid. The comparative analysis found that changes in coding gene expression were more closely associated with changes in lncRNA expression. Moreover, the coding genes regulated by ellagic acid have cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor activity, oxidoreductase, and catalytic activity (Fig. 3a and b). Altogether, this evidence supports the concept that lncRNA has an important role in ellagic acid-induced CRC cell death. Analysis of confirmatory RT-qPCR results showed there a great correlation with the microarray expression data obtained in our study. Figure 4 shows the entire study workflow. Demonstration of the differential expression of target genes using RT-qPCR shows that microarray analysis is reproducible and reliable.

As described above, lncRNAs play obvious molecular roles. Although lncRNAs may also exert epigenetic effects as precursors of small RNA, lncRNAs have been reported to play an important role in dose compensation, chromatin regulation, genomic imprinting, and many other biological processes [42–44]. Furthermore, there is evidence indicating that lncRNAs respond to stress in a variety of ways, which are also cell-type and/or drug-specific [45]. Intergenic lncRNAs account for half of the total expressed lncRNA. Intergenic lncRNA can effectively regulate gene expression by modifying RNA binding proteins or chromatin complex formation. Moreover, there are many reports describing dysregulated expression of lncRNAs in genes and cancers [46,47]. Intergenic lncRNA is considered a new link for the entire process of oncogenesis and can be used in multiple steps of treatment [47]. LncRNAs have also been reported to be very important in the entire process of CRC. For example, Tao et al. [48] reported that nuclear factor-κB-interacting lncRNA is down-regulated in CRC, and can obviously exert a certain tumor suppressor effect. Tsai [49] reported that Linc00659 acts as a new type of oncogene in the process of CRC by regulating the growth of cancer cells. Studies by Zhang [50] determined that the expression of glucose phosphate mutant enzyme 5 antisense RNA1 (PGM5-AS1) in CRC tissues was significantly down-regulated in vivo in humans, while in-vitro PGM5-AS1 inhibits the growth of CRC cells as determined by the comparison and analysis of abnormally expressed genes in the GeneChip microarray.

The present study compared 1783 mRNA and 1658 lncRNAs differentially expressed in CRC tissue samples. Regulating corresponding mRNAs is one of the main ways that lncRNAs exert their regulatory functions. We documented the selective differential expression of lncRNA in ellagic acid-treated CRC cells. The functions of many identified lncRNAs are uncertain. Through the effective establishment of the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network, the identification of key lncRNAs and their target gene related to ellagic acid grown in HCT116 cells can be achieved. According to the analysis of lncRNA/mRNA co-expression network, the expression of mRNA associated with several oncogenes, such as ASF1A, KIF4A, nucleolin and ROCK1, was down-regulated by corresponding ellagic acid-inhibited LncRNAs n335586, n340075, n342597, and ENST00000548702. The n335586 was the most down-regulated lncRNA, and it was also the most significant hub gene with 26 related edges. Related coding mRNAs include several genes that are significantly related to the occurrence of cancer. The lncRNA n335586 has a length of 270 nt and is located on the CKMT1A gene on chromosome 15. It is reported that overexpression of lnc n335586 contributes to cell migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells [51]. LncRNA n335586 has more neighbors in the network, indicating its important role in regulating gene expression and protein translation determining the anti-proliferative effects observed in ellagic acid-treated HCT116 cells.

In summary, our findings effectively underline the important role of differentially expressed lncRNAs involved in the ellagic acid-mediated apoptosis of CRC cells. We identified the lncRNA n335586 in CRC through integrated gene chip analysis. Differentially expressed lncRNA n335586 may act as a potentially important therapeutic target for the treatment of human CRC. Thus, it is necessary to determine whether similar changes in the lncRNA transcriptome are observed in CRC patients and to further evaluate the potential role of lncRNA n335586 as a therapeutic target for CRC. The above results point towards lncRNAs becoming biomarkers in the diagnosis and treatment of CRC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Excellent youth project of the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (Grant No. HYDSYYXQN202006, principal investigator J.Z.), the youth project of Science and technology innovation project of Heilongjiang Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Grant No. ZHY19-080, principal investigator J.Z.), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82072673, principal investigator G.L.). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen D, Song S, Lu J, Luo Y, Yang Z, Huang Q, et al. Functional variants of -1318T>G and -673C>T in c-Jun promoter region associated with increased colorectal cancer risk by elevating promoter activity. Carcinogenesis 2011; 32:1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu Q, Hu T, Zheng E, Deng X, Wang Z. Prognostic role of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in colorectal cancer: an up-to-date meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2017; 96:e7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G, Lu X, Yuan L. ncRNA: a link between RNA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014; 1839:1097–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNA in cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21:1253–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim T, Croce CM. Long noncoding RNAs: undeciphered cellular codes encrypting keys of colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Lett 2018; 417:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batista PJ, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs: cellular address codes in development and disease. Cell 2013; 152:1298–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhamija S, Diederichs S. From junk to master regulators of invasion: lncRNA functions in migration, EMT and metastasis. Int J Cancer 2016; 139:269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 2009; 136:629–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St Laurent G, Wahlestedt C, Kapranov P. The landscape of long noncoding RNA classification. Trends Genet 2015; 31:239–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng Y, Liu L, Shukla GC. A comprehensive review of web-based noncoding RNA resources for cancer research. Cancer Lett 2017; 407:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, French C, Lin MF, Feldser D, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature 2009; 458:223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolha L, Ravnik-Glavač M, Glavač D. Long noncoding RNAs as biomarkers in cancer. Dis Markers 2017; 2017:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nana-Sinkam SP, Croce CM. Non-coding RNAs in cancer initiation and progression and as novel biomarkers. Mol Oncol 2011; 5:483–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung T, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNA in genome regulation: prospects and mechanisms. RNA Biol 2010; 7:582–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X, Song JH, Cheng Y, Wu W, Bhagat T, Yu Y, et al. Long non-coding RNA HNF1A-AS1 regulates proliferation and migration in oesophageal adeno-carcinoma cells. Gut 2014; 63:881–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts TC, Morris KV, Weinberg MS. Perspectives on the mechanism of transcriptional regulation by long non-coding RNAs. Epigenetics 2014; 9:13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spizzo R, Almeida MI, Colombatti A, Calin GA. Long non-coding RNAs and cancer: a new frontier of translational research? Oncogene 2012; 31:4577–4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Plants as a source of anti-cancer agents. J Ethnopharmacol 2005; 100:72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitley AC, Stoner GD, Darby MV, Walle T. Intestinal epithelial cell accumulation of the cancer preventive polyphenol ellagic acid-extensive binding to protein and DNA. Biochem Pharmacol 2003; 66:907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiyer HS, Vadhanam MV, Stoyanova R, Caprio GD, Clapper ML, Gupta RC. Dietary berries and ellagic acid prevent oxidative DNA damage and modulate expression of DNA repair genes. Int J Mol Sci 2008; 9:327–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho H, Jung H, Lee H, Yi HC, Kwak HK, Hwang KT. Chemopreventive activity of ellagitannins and their derivatives from black raspberry seeds on HT-29 colon cancer cells. Food Funct 2015; 6:1675–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertens-Talcott SU, Lee JH, Percival SS, Talcott ST. Induction of cell death in Caco-2 human colon carcinoma cells by ellagic acid rich fractions from muscadine grapes. J Agric Food Chem 2006; 54:5336–5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li LW, Na C, Tian SY, Chen J, Ma R, Gao Y, et al. Ellagic acid induces HeLa cell apoptosis via regulating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling. Exp Ther Med 2018; 16:29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao JL, Li GD, Bo WL, Zhou YH, Dang SW, Wei JF, et al. Multiple effects of ellagic acid on human colorectal carcinoma cells identified by gene expression profile analysis. Int J Oncol 2017; 50:613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao J, Li G, Wei J, Dang S, Yu X, Ding L, et al. Ellagic acid induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the TGF β1/Smad3 signaling pathway in human colon cancer HCT 116 cells. Oncol Rep 2020; 44:768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:716–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engstrom PG, Suzuki H, Ninomiya N, Akalin A, Sessa L, Lavorgna G, et al. Complex loci in human and mouse genomes. PLoS Genet 2006; 2:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR, Pang KC, Bruce SJ, Gardiner BB, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Genome Res 2008; 18:1433–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balakrishnan R, Harris MA, Huntley R, Van Auken K, Cherry JM. A guide to best practices for Gene Ontology (GO) manual annotation. Database (Oxford) 2013; 2013:bat054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao Q, Liu C, Yuan X, Kang S, Miao R, Xiao H, et al. Large-scale prediction of long non-coding RNA functions in a coding-non-coding gene co-expression network. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39:3864–3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Young GP, Sano Y, Chiu HM, Byeon JS, et al.; Asia Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. Asia Pacific consensus recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. Gut 2008; 57:1166–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Dyba T, Randi G, Bettio M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur J Cancer 2018; 103:356–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ceci C, Lacal PM, Tentori L, De Martino MG, Miano R, Graziani G. Experimental evidence of the antitumor, antimetastatic and antiangiogenic activity of ellagic acid. Nutrients 2018; 10:1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umesalma S, Sudhandiran G. Differential inhibitory effects of the polyphenol ellagic acid on inflammatory mediators NF-kappaB, iNOS, COX-2, TNF-alpha, IL-6 in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced rat colon carcinogenesis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010; 107:650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kong X, Ding X, Yang Q. Identification of multi-target effects of Huaier aqueous extract via microarray profiling in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2015; 46:2047–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Li W, Jin T, Xiang X, Li M, Wang J, et al. Gene microarray analysis of lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles in patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:4862–4882. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou M, Ye Z, Gu Y, Tian B, Wu B, Li J. Genomic analysis of drug resistant pancreatic cancer cell line by combining long non-coding RNA and mRNA expression profiling. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8:38–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L, Zhang J, Jiang A, Liu Q, Li C, Yang C, et al. Expression profile of long non-coding RNAs is altered in endometrial cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:5010–5021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang QQ, Deng YF. Genome-wide analysis of long non-coding RNA in primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma by microarray. Histopathology 2015; 66:1022–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitra SA, Mitra AP, Triche TJ. A central role for long non-coding RNA in cancer. Front Genet 2012; 3:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Wu Z, Fu X, Han W. Long noncoding RNAs: insights from biological features and functions to diseases. Med Res Rev 2013; 33:517–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin L, Chang HY. Uncovering the role of genomic ‘dark matter’ in human disease. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:1589–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moran VA, Perera RJ, Khalil AM. Emerging functional and mechanistic paradigms of mammalian long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:6391–6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozgur E, Mert U, Isin M, Okutan M, Dalay N, Gezer U. Differential expression of long non-coding RNAs during genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis in HeLa and MCF-7 cells. Clin Exp Med 2013; 13:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer 2011; 10:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai MC, Spitale RC, Chang HY. Long intergenic noncoding RNAs: new links in cancer progression. Cancer Res 2011; 71:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao F, Xu Y, Yang D, Tian B, Jia Y, Hou J, et al. LncRNA NKILA correlates with the malignant status and serves as a tumor suppressive role in rectal cancer. J Cell Biochem 2018; 119:9809–9816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai KW, Lo YH, Liu H, Yeh CY, Chen YZ, Hsu CW, et al. Linc00659, a long noncoding RNA, acts as novel oncogene in regulating cancer cell growth in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer 2018; 17:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q, Ding Z, Wan L, Tong W, Mao J, Li L, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the long noncoding RNA expression profile and construction of the lncRNA-mRNA co-expression network in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2020; 21:157–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan H, Lv P, Mu T, Zhao X, Liu Y, Feng Y, et al. LncRNA n335586/miR-924/CKMT1A axis contributes to cell migration and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 2018; 429:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]