Abstract

Halomethoxybenzenes are pervasive in the atmosphere at concentration levels that exceed, often by an order of magnitude, those of the persistent organic pollutants with which they share the attributes of persistence and potential for long-range transport, bioaccumulation, and toxic effects. Long ignored by environmental chemists because of their predominantly natural origin—namely, synthesis by terrestrial wood-rotting fungi, marine algae, and invertebrates—knowledge of their environmental pathways remains limited. Through measuring the spatial and seasonal variability of four halomethoxybenzenes in air and precipitation and performing complementary environmental fate simulations, we present evidence that these compounds undergo continental-scale transport in the atmosphere, which they enter largely by evaporation from water. This also applies to halomethoxybenzenes originating in terrestrial environments, such as drosophilin A methyl ether, which reach aquatic environments with runoff, possibly in the form of their phenolic precursors. Our findings contribute substantially to the comprehension of sources and fate of halomethoxybenzenes, illuminating their widespread atmospheric dispersal.

Persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic substances of natural origin evaporate from water into air, where they are widely dispersed.

INTRODUCTION

Halomethoxybenzenes (HMBs) comprise benzenes substituted with halogens and one or more methoxy groups but not with other substituents, e.g., halogenated anisoles and dimethoxy compounds. HMBs are mainly produced or transformed in the environment either by biotic or abiotic processes and therefore are often considered “natural products.” HMBs have gained the attention of the scientific community because of widespread occurrence and relatively high concentrations in terrestrial and marine environments, while also exhibiting properties that resemble those of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) (1–6). The occurrence of HMBs in remote regions, combined with long atmospheric half-lives (exceeding the threshold of 2 days) indicate potential for long-range transport (LRT) (4). Furthermore, some HMBs have been shown to accumulate in aquatic and terrestrial organisms, for example, halogenated dimethoxy compounds have been reported in wild boar (7), Great Lakes fish (8), and sea turtles and sharks (9). Some halogenated dimethoxy compounds can persist in the environment for many years (10). Whereas toxicity data of HMBs are limited, sublethal effects of chlorinated veratroles and anisoles to zebra fish embryos and larvae have been reported with toxic threshold concentrations ranging 2.8 to 450 μg liter−1 (11). Toxic effects of halogenated phenols, which are regarded as precursors of HMBs, have been identified. For example, 2,4,6-tribromophenol, the precursor of 2,4,6-tribromo-anisole (TBA), has been demonstrated to disturb the human thyroid transport protein transthyretin and cause reproductive effects in fish (12, 13). In view of the potential environmental effects, halogenated natural products have been included in the assessment of “Chemicals of Emerging Arctic Concern” by the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (14).

Both anthropogenic and biogenic activities might be involved in the formation of HMBs. Usually, they are formed by microbial methylation of chloro- or bromo-phenolics, whereby the precursors could be either naturally produced or released from human activities (1). Brominated anisoles (BAs) are formed from O-methylation of bromophenols, which are widely produced by marine algae and invertebrates (15). While BAs are therefore usually considered to have marine origin, bromophenols have also been reported to be disinfection by-products formed during water chlorination (16). In contrast, chloroanisoles are more likely to be of anthropogenic origin as the precursor chlorophenols are commercially used as fungicides and wood preservative (5). Some chlorinated anisoles and phenols, i.e., pentachlorophenol (PCP) and its derivatives, have been regulated as POPs under the Stockholm Convention since 2015 (17). Chlorinated veratroles were reported to be formed via biological methylations of chlorinated guaiacols and catechols, which are associated with chlorine bleached kraft pulp effluents (11, 18). In contrast, 1,2,4,5-tetrachloro-3,6-dimethoxybenzene [drosophilin A methyl ether (DAME)], a structural isomer of tetrachloroveratrole (TeCV), is believed to be synthesized by terrestrial fungi and has been found in crystal form in decayed heartwood (10, 19).

Whereas the atmospheric levels and air-water exchange of HMBs have been studied extensively, largely missing so far are studies on the spatial variability of HMBs in the atmosphere, even though they might provide insights into sources. Early work investigating spatial pattern of chlorinated anisoles in the marine atmosphere over the East Atlantic and North Pacific Ocean recorded higher concentrations in the northern hemisphere compared to the South, which was attributed to higher anthropogenic inputs in the more populated and industrialized North (2, 5). While microbial formation of chlorinated anisoles from chlorinated phenols is well established, a continent-scale study of pentachloroanisole (PCA) and PCP in pine needles revealed divergent spatial pattern, indicating potentially different sources for the two compounds (20). In the Nordic region, Bidleman et al. (6) interpreted higher atmospheric level of BAs at a coastal site relative to an inland site as reflecting marine origin. Higher concentrations in the south and during summer (June to August) were associated with higher rates of brominated phenol production, which are temperature and salinity dependent (21, 22). For dimethoxylated HMBs, Bidleman et al. (6) reported levels and time trends of TeCV and DAME at two Nordic sites, as well as their relationship with halogenated anisoles and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Close relationships between TeCV and DAME and with BAs might suggest similar sources and environment fate, even though previously different sources had been assigned to these HMBs (10, 11, 18, 19). Spatial pattern of dimethoxylated HMBs could provide more insights into their sources, but no such data are available so far.

Here, we report on the concentrations of HMBs in air, water, and atmospheric deposition samples from across Southern Canada. The study regions include Canada’s most populous cities as well as coastal areas on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Not only does this effort represent some of the first such measurements in North America, but also it is the first to comprehensively record spatial distribution patterns using passive sampling networks comprising a large number of sampling sites. The ability to map the levels of HMBs was used to shed fresh light on their origins and fate. Furthermore, we use model simulations of environmental fate and LRT to support and explain the measurements.

RESULTS

Atmospheric levels

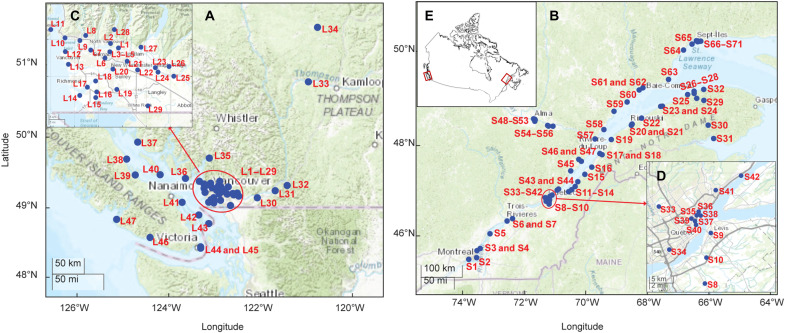

HMBs were quantified in more than 235 passive air samplers (PASs), deployed for periods ranging from 4 to 12 months, and 72 samples taken with active air samplers (AASs) collected from 2019 to 2022 with the aim to investigate their atmospheric concentrations and spatial variability on the east and west coasts of Canada. The study region included Canada’s largest cities as well as coastal areas in the St. Lawrence River and Estuary and Salish Sea region. Figure 1 displays maps with the sampling sites in each region, with more highly resolved maps for tightly clustered sites inserted. Details on PAS and AAS sampling and the quantification results are provided in tables S1 and S2.

Fig. 1. Sampling locations of passive air sampler (PAS) networks.

Labeled sampling sites in Southwestern British Columbia (A) and Southern Quebec (B), with inserted maps providing higher resolution for Vancouver (C) and Quebec City (D). A large-scale map shows the location of the sampling regions on the east coast and west coast of Canada (E).

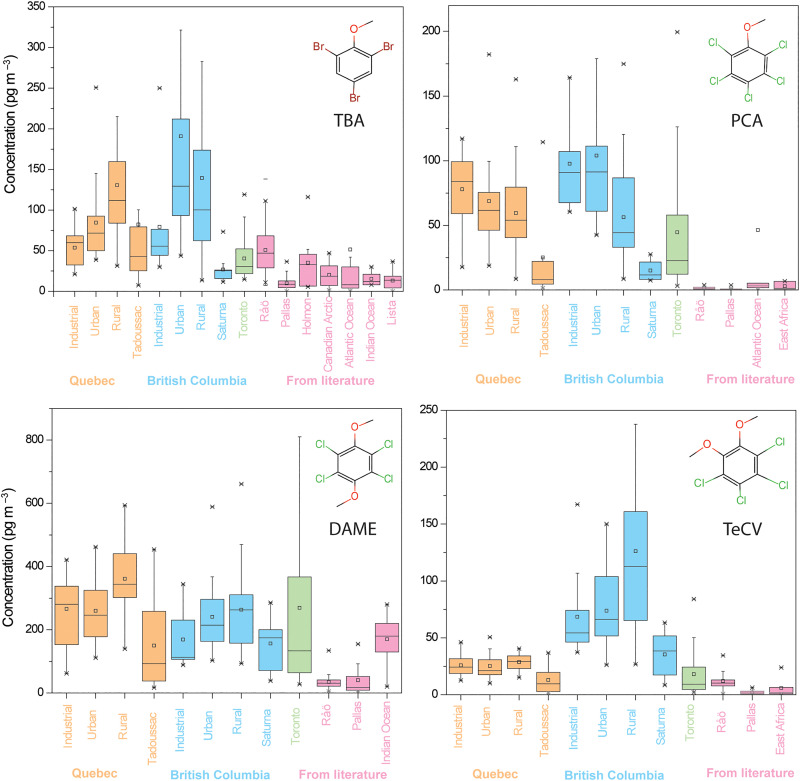

TBA, PCA, TeCV, and DAME were detected above the detection limits in every passive and active air sample analyzed in this study (except for TeCV in three PASs). Because HMBs were not detected on atmospheric particles, i.e., the filters of the AAS, the gaseous concentrations in AAS and PAS represent the bulk HMB concentrations in the atmosphere. For these four compounds, Fig. 2 compares the concentrations and their variability between the three studied Canadian regions [Quebec (QC), British Columbia (BC), and Toronto]. The data from the PAS networks are displayed separately on the basis of site classifications (industrial, urban, and rural). Furthermore, data for other locations reported in the literature are presented in Fig. 2 for comparison, with more details provided in table S3. While we compare time-averaged concentrations at multiple locations from the PAS networks with multiple short-term measurements obtained by AAS at one location, the averages in both cases should approximate the long-term means. However, it is not appropriate to compare the variability of PAS and AAS data in Fig. 2, as they convey information on spatial and temporal variability, respectively. A detailed description and the comparison of the levels in PAS and AAS are provided in the Supplementary Materials (text S1 and table S4).

Fig. 2. Comparison of atmospheric levels of HMBs in different Canadian regions with literature data.

Only data from studies with more than 10 samples are included. Details on studies reported for Sweden (Råö and Holmon), Norway (Lista), Finland (Pallas), the Canadian Arctic, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and East Africa are provided in table S3. Some outliers with very high concentration are not displayed. Data labeled “industrial,” “urban,” and “rural” in Quebec (QC) and British Columbia (BC) are from passive air samplers; all others are from active air samplers.

The presence of these four HMBs in almost all air samples attests to their ubiquity in the atmosphere. The high spatial and temporal variability apparent in Fig. 2 suggests that this is not a result of very long atmospheric residence times leading to well-mixed concentrations within a hemisphere (as is, e.g., the case for hexachlorobenzene) (23) but rather is due to a combination of wide-spread sources to the atmosphere and atmospheric residence times allowing for dispersal on a regional scale. Support for substantial potential of the HMBs for long-range atmospheric transport is provided by a screening model–based assessment described in detail in the Supplementary Materials (text S2 and table S6).

The sequence in the relative abundance of the four compounds is the same in almost all studied regions, with DAME being the most abundant, followed by TBA. The relative abundance of PCA and TeCV differs somewhat between regions, with PCA being more abundant than TeCV in QC and Toronto, while these two compounds have very similar levels in BC. The latter is due to TeCV being much higher in BC than elsewhere. Levels of PCA and DAME are similar in BC and QC and levels of TBA are slightly higher in BC compared to QC. Levels of PCA, TeCV, and TBA are generally lower in Toronto than on the coasts. DAME is the exception in that levels in Toronto are comparable to those on the coasts. PCA levels tend to decrease from industrial and urban to rural sites, as one might expect for a chemical with mostly anthropogenic sources. The opposite trend is apparent for the levels of DAME, TBA, and TeCV, whereby site classification is very influential for TeCV in BC but not in QC.

The averaged levels of HMBs in this study were overall higher than those reported for other locations (table S3). Specifically, TBA were 2 to 5 times higher than those reported by Bidleman et al. at coastal sites in the Nordic region (6, 21, 22, 24) and 2 to 10 times higher than those at coastal sites and in marine air (25–27), and Canadian Artic air (4). Levels of PCA were one to two orders of magnitude higher than those in the Nordic region and East Africa (3, 6) but still lower than those reported in air above the North Atlantic and in air over a wastewater treatment plant in Germany in the 1990s (2, 28). DAME levels here were five to seven times higher than in the Nordic region but only slightly higher than level over the southern Indian ocean (6, 27). Concentrations of its structural isomer TeCV, on the other hand, were one order magnitude greater than those in the Nordic region and in East Africa (3, 6).

Veratrole with one to three chlorines were only quantified in a selection of 83 PASs (table S7). Of these, only 3-chloroveratrole (3-MoCV) was frequently detected (84% detection frequency), with low levels that were similar in BC (11.8 ± 6.7 pg m−3) and QC (11.0 ± 5.9 pg m−3). 4-chloroveratrole (4-MoCV) was only detected in a quarter of the analyzed extracts in BC and in only one sample from Quebec. When present above detection limits, 4-MoCV concentrations (24.3 ± 13.6 pg m−3) were higher than those of its isomer in BC. 4,5-Dichloroveratrole (DiCV) could not be quantified because of interferences. 3,4,5-Trichloroveratrole (TriCV) with a detection frequency of less than 45% had average levels of 5.6 ± 2.7 pg m−3, which are comparable to level reported in the atmosphere of Lake Victoria in East Africa (3). We believe these to be the first reported concentrations of monochlorinated veratrole in the atmosphere.

Spatial patterns of HMBs in air

The PAS networks in QC and BC allow us to investigate the spatial patterns of the four regularly detected HMBs in the atmosphere (Fig. 3). The pattern for TBA clearly indicates the importance of marine sources. In BC, sites close to the ocean have higher levels than those further inland (Fig. 3A). High TBA concentrations (> 400 pg m−3) were found at near-shore sites on Vancouver Island (L39 and L41), including in Victoria (L44 and L45). Within Vancouver, several coastal sites (L10, L13, L14, and L15) had levels that were clearly elevated, relative even to sites only a few kilometers inland (see inset map in Fig. 3A). The same can be seen in QC (Fig. 3B), where the sites along the St. Lawrence Estuary record higher TBA levels, especially along the south shore (with S19, S23, and S26 showing levels in excess of 200 pg m−3), than those further away from marine waters. This is apparent in lower levels in the St. Lawrence River valley (S1 to S10), in the Saguenay area (S48 to S56), and along a transect across the Gaspé peninsula (S26 to S31; fig. S1).

Fig. 3. Spatial patterns of HMBs in the atmosphere of Southwestern British Columbia (BC) and Southern Quebec (QC).

Concentrations in picograms per cubic meter are displayed for TBA (A and B), PCA (C and D), DAME (E and F), and TeCV (G and H). Panels on the left [(A), (C), (E), and (G)] show BC with an inserted map providing higher resolution for Vancouver. Panels on the right [(B), (D), (F), and (H)] show QC with an inserted map for Quebec City. To eliminate possible effects of seasonal variability, the spatial patterns are based on PASs deployed in seasons with comparable average temperatures. Levels from samplers deployed at the same site during similar temperatures were averaged. Triangles (instead of dots) are used for samplers deployed during deviating temperatures. Large dots represent measured levels that exceed the maximum value of the color scale.

However, we could easily detect TBA also at sites very far from the ocean. We recorded levels of 45 pg m−3 at a site in Montreal, which is similar to the annual average of ~40 pg m−3 measured with the AAS in Toronto. Similar levels were also present at sites L33 and L34 in the BC interior, which is separated from the ocean by the coastal mountain range. These are concentrations in the same range as those reported in Northern Europe (6, 21, 22, 24). Given this, anthropogenic sources might also contribute, in addition to LRT. For example, within the St. Lawrence River valley, we recorded slightly higher levels around 100 pg m−3 in Sorel-Tracy (S5), a center of the steel industry.

PCA, generally believed to originate from anthropogenetic activities, has a spatial pattern distinct from the other HMBs. Waite et al. (29) reported higher PCP air concentration at urban sites compared to rural sites as well as elevated level in the vicinity of utility pole storage site, in which PCP-containing wood preservative had been applied. Similarly in this study, urban sites generally have higher level of PCA, e.g., in Vancouver (L1 to L29) (Fig. 3C) and along the Montreal–Quebec City corridor and the upper estuary (S1 to S16 and S33 to S47) and sites S52 and S55 in the Saguenay region (Fig. 3D). There is considerable variability within the Vancouver area, with elevated levels at some locations along Burrard Inlet (>100 pg m−3; L1, L6, and L7) and at the mouth of the Fraser River (>300 pg m−3, L14), yet much lower ones at sites further upstream on the Fraser (< 50 pg m−3 e.g., at L17, L18, and L24) (Fig. 3C, inset). An exceptional high value was recorded at site S59 on the Northern shore of the estuary. Very low levels are apparent at inland sites on the Gaspé (S28 to S30) and in the BC interior (L32 and L34), suggesting a possible role for water bodies in the delivery of PCA to the atmosphere. However, some coastal sites also have very low PCA levels.

DAME and TeCV show remarkably complex spatial patterns. In both BC and QC, the highest levels of DAME (>400 pg m−3) were recorded at sites in the vicinity of the ocean. In BC, these levels were measured at sites on the Salish Sea (L39, L40, L42, and L43) but also at a number of sites in the Vancouver region (UBC L12, Burnaby L6, and Boundary Bay L15) (Fig. 3E), whereas in QC, this was the case at numerous sites on the St. Lawrence estuary (S32, S45, S25, and S26) (Fig. 3F). While this may suggest a marine source, sites in the interior of BC (L33 and L34) or in the St. Lawrence River valley (S5 Sorel-Tracy, S2, S3, S6, and S9) often also had fairly high levels (>300 pg m−3). Clearly, the annual average of the DAME concentrations measured in Toronto (~270 pg m−3) is clear evidence that there are nonmarine sources of DAME to the atmosphere. In BC, TeCV has high levels around the Salish Sea (L36, L39, L40, L42, and L43) (Fig. 3G) and also in Burrard Inlet (L28 Indian Arm). In QC, TeCV levels are a lot lower and also a lot more uniform, with sites with slightly higher levels in the St. Lawrence River valley (S5 and S8) and the Quebec City area (S9 and S34) (Fig. 3H).

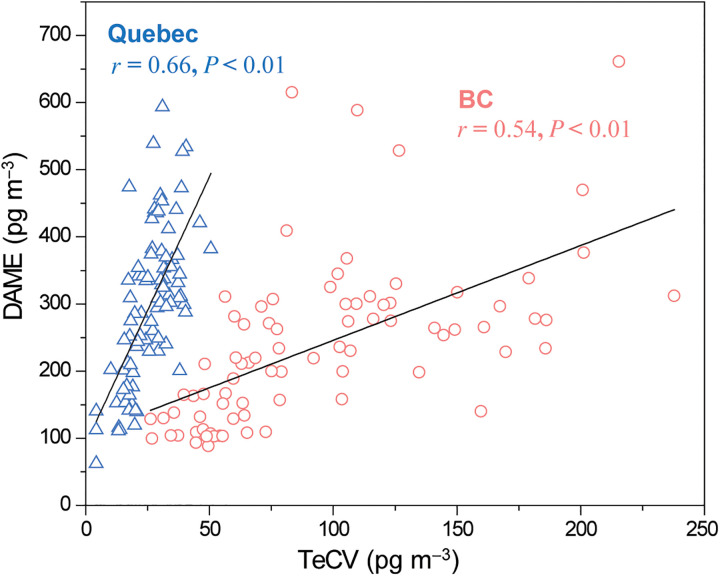

Overall, the patterns for DAME and TeCV share similarities, which is also evident in fairly high correlations between their concentrations in BC (r = 0.54) and QC (r = 0.66), significant at P < 0.01 (table S8 and Fig. 4). Bidleman et al. (6) also had observed strong correlations between these two compounds at both of Råö and Pallas in Northern Europe. More correlations between HMBs are discussed in the Supplementary Materials (text S3).

Fig. 4. Correlations between DAME and TeCV in the atmosphere of Southwestern British Columbia (BC) (red circle) and Southern Quebec (QC) (blue triangle) in Canada.

TeCV levels are several folds higher in BC than in QC. While TeCV has been linked with pulp bleaching processes (11, 18), the National Pollutant Release Inventory of Canada (30) does not indicate a higher release of contaminants associated with the pulp and paper industry in BC compared to QC. Neither can we find evidence that TeCV levels are elevated in close proximity to pulp and paper manufacturing facilities (fig. S2). The reason for this may be that the formation of chlorinated phenolic compounds from pulp bleaching has been greatly reduced since elemental chlorine-free bleaching was introduced after 2000.

Because of the extensive formation of DAME in decaying wood by basidiomycete, forest fires have been hypothesized as a potential pathway for DAME to the atmosphere (10). In our study, DAME levels in air were not related to forest cover or with the occurrence of forest fires in the vicinity of a sampling site. We also did not observe any correlation between the concentrations of DAME (or TeCV) in air and those of retene, a commonly used marker of biomass burning (31). In Northern Europe, Bidleman et al. (10) also did not find a significant positive relationship between levels of DAME and benzo[a]pyrene (a potential marker for biomass burning).

We conclude that sources other than the pulp and paper industry or forest fires need to be invoked to explain the prevalence of TeCV and DAME in the environment. The spatial patterns in this study suggest that evaporation from water contributes to their presence in the atmosphere. Similar to TBA, we record decreasing trends of DAME from the southeast shore of the estuary to the offshore sites on the Gaspé (sites S26 to S31; fig. S1), suggestive of evaporation from the estuary as a source. Evaporation from water bodies as a source of DAME to the atmosphere may not be limited to the ocean but may also occur from fresh water as comparable levels of DAME were found in the Toronto atmosphere (far from the ocean but next to Lake Ontario) (table S2). In East Africa, higher TeCV levels were found near Lake Victoria than further away from the lake (3).

Seasonal variability of HMBs in air

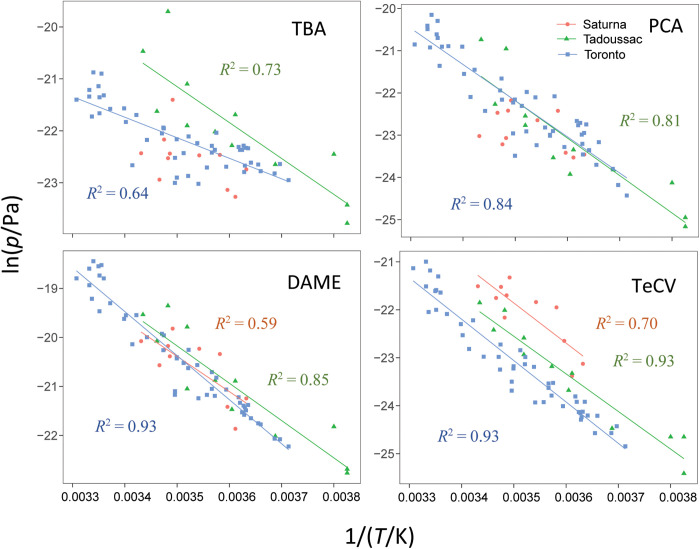

The atmospheric levels of HMBs exhibit large seasonal variations (Fig. 5). The four frequently detected HMBs showed similar trends at all three AAS locations, with generally higher concentrations levels during the warm season. Regressions of the logarithm of partial pressure log p against reciprocal temperature 1/T [Clausius-Clapeyron (CC) plots; Fig. 6 and table S8] were significant for all four HMBs in Tadoussac and Toronto (P < 0.01) but not for TBA and PCA on Saturna Island.

Fig. 5. Temporal variability of the concentrations of four HMBs in the atmosphere.

Changes in temperature (right y axis) and concentrations (left y axis) in Saturna Island, British Columbia (BC) in 2019–2020 (A), Tadoussac, Quebec (QC) in 2020–2021 (B), and Toronto, Ontario in 2020–2021 [(C), note different x axis].

Fig. 6. Regressions of logarithm of partial pressure (in pascals) of HMBs against reciprocal of temperature (in kelvin) on Saturna Island, in Tadoussac, and Toronto.

Regressions for TBA and PCA on Saturna Island were not significant. Slopes and P values are given in table S9.

Apparent enthalpies of surface-air exchange (ΔHSA-app) derived from the slopes of the CC relationships are comparable to, or slightly higher than, values reported previously for the Nordic region (table S9) (6). Comparing the ΔHSA-app with enthalpies of exchange between water and air ΔHWA and soil and air ΔHSoilA has been used to gauge the relative importance of local air-surface exchange and LRT for the presence of a compound in the atmosphere (32, 33). For the HMBs, this interpretation could be somewhat confounded by rates of formation (e.g., O-methylation) increasing with temperature. In other words, because temperature not only affects the air-surface equilibrium but also the amount of chemical available for evaporation, ΔHSA-app values that exceed ΔHWA and ΔHSoilA values are possible. Nevertheless, the derived ΔHSA-app for the HMBs falling close to ΔHWA and the enthalpies of exchange between octanol and air ΔHOA suggest that local exchange processes are important. An exception is TBA in Toronto, which has a shallow slope (smaller ΔHSA-app value), suggesting that long-range transport is playing a larger role in controlling the atmospheric levels of TBA in Toronto than in Tadoussac. This is consistent with the large geographical distance of Toronto from marine sources and a substantial long-range atmospheric transport potential estimated for TBA (text S2 and table S6). The lack of a temperature dependence of TBA and PCA on Saturna Island could be due to the small annual temperature range and the smaller number of data points.

At 11 of the sites in BC, PASs were deployed at least three times during different seasons, and therefore different temperatures, which allowed us to also explore the temperature dependence of air concentrations at those locations. We again observed higher levels of the four main HMBs during warmer deployments, with 28 of the 44 log p versus 1/T regressions for these sites having an R2 greater than 0.6 (table S10). The ΔHSA-app calculated for DAME and PCA from these PAS data were again close to the ΔHWA and ΔHOA, lending support for local exchange being dominant for DAME and PCA. TeCV, in particular, showed a clear temperature dependence at most sites. The ΔHSA-app of TeCV at inland sites (L3 to L5, L13, L31, and L34) was smaller than at coastal sites (L39 and L44), suggestive of TeCV originating from water and being transported inland. This interpretation is further supported by all sites with elevated TeCV levels being near water in BC (Fig. 3). ΔHSA-app of TBA were mostly close to ΔHWA and ΔHOA. A negative ΔHSA-app, indicating higher levels during colder deployments, was calculated for TBA at the BC site farthest from the ocean (L34). This might be indicative of TBA’s marine origin and the ability to undergo LRT.

Local exchange is influenced by meteorological conditions, i.e., temperature and wind. Wind direction was further examined in Toronto in addition to temperature. The winds were divided into three categories: rural winds, urban winds, and lake winds (fig. S3). The correlations between atmospheric levels and wind fractions were analyzed (table S11). The fraction of lake winds is significantly correlated with HMB levels, suggesting that the lake is the potential local sources of HMBs. This was the case even for TBA, for which the CC-plot indicated a larger influence of LRT in Toronto.

HMBs in precipitation

The HMBs levels in precipitation collected with a monthly resolution for 1 year on Saturna Island, BC, and in Tadoussac, QC, are summarized in table S12. HMBs were not detected in the filter of precipitation. Concentrations of 2,4-dibromoanisole (DBA) in precipitation ranged from <MDL (method detection limits) to 100 pg liter−1 on Saturna and from <MDL to 186 pg liter−1 in Tadoussac. DAME was detected in all samples, with averaged levels of 306 ± 82 and 457 ± 233 pg liter−1 on Saturna and in Tadoussac, respectively. TBA (123 ± 111 pg liter−1) and 4-MoCV (250 ± 133 pg liter−1) were detected in Tadoussac precipitation. PCA was only detected in two summer time samples from Tadoussac. More frequent detections and higher concentration of HMBs in precipitation in Tadoussac may be related to the lower temperatures favoring partitioning from gas to water. Wet deposition fluxes were also calculated for the detected HMBs. A higher rain fall rate on Saturna compensates for lower concentrations, so the wet deposition of DBA and DAME were similar in the two regions (table S12). The concentrations of DBA, TBA, and DAME in precipitation and their deposition fluxes reported here are about four to five times higher than what has been reported at the coastal Råö site and up to one order of magnitude greater than the inland Pallas site in the Nordic region (6).

The year-long measurements at Tadoussac and Saturna Island allowed scavenging ratios SR to be estimated from the concentration in precipitation (pg m−3) and air (pg m−3). Because concentrations in both media are required, this could only be done for TBA and PCA in Tadoussac and for DAME at both sites. An SR close to the water-air partitioning ratio KWA of the HMB at the temperature of the precipitation event indicates equilibrium between atmospheric gas phase and rainwater. Considering the uncertainty of KWA and the measured concentrations and of combining a monthly precipitation sample with a 24-hour air sample taken during the same month, the SRs of TBA (SR/KWA = 1.8 ± 0.82) and DAME (SR/KWA = 2.7 ± 1.3 and 3.0 ± 1.7 at Tadoussac and Saturna Island, respectively) (table S13) are indeed indicating equilibrium conditions. The SRs for DAME was significantly (P < 0.05) related to temperature at both sites (fig. S4). Values of the apparent internal energy change for water-air transfer (ΔUWA-app) for DAME of 62 ± 21 (Saturna Island) and 54 ± 12 kJ mol−1 (Tadoussac) estimated from the slope of ln SR versus 1/T are comparable with a predicted ΔUWA of 66 kJ mol−1. The SRs for HMBs in this study are very similar to those reported previously for Northern Europe (6), suggesting that precipitation scavenging of HMBs is well described by equilibrium partitioning between atmospheric gas phase and precipitation. The SR estimated for PCA was about one order of magnitude higher than the KWA but might not be trustworthy as only two data points were available in precipitation with level close to the detection limit.

HMBs in water

Concentrations of HMBs in water, sampled passively at 10 sites in each of QC and BC in summer 2021 (fig. S5), are summarized in table S14. No notable vertical gradients were found when comparing concentrations in passive water samplers (PWSs) deployed at different water depths (table S13). In contrast to the atmosphere, TBA was the most abundant HMB in water with average concentration of 3700 ± 2700 pg liter−1, followed by DAME. PCA had the lowest concentrations in both regions (4.8 ± 2.4 pg liter−1), while TeCV was only detected in BC. Overall, HMB levels in both regions are comparable, i.e., slightly higher level for TBA and slight lower level for DAME in BC, but similar PCA levels in the two regions. The PWS results are consistent with the measurements in air. For example, high TBA concentrations in water support its marine origin. Detection of TeCV only in PWS deployed in BC is aligned with the much higher atmospheric level of TeCV in BC and suggestive of volatilization from water.

TBA levels in water measured in this study are generally higher than what has been reported elsewhere, specifically, six to eight times higher than at the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, and up to two orders of magnitude higher than in Northern Europe and the Canadian Arctic (4, 21, 34, 35). PCA has been reported in a wide range of concentrations in water, from <1 pg liter−1 to up to 290 ng liter−1 (36–40). Its concentration in this study was about one order of magnitude lower than the level reported in Lake Ontario but slightly higher than in seawater of the German Bight (North Sea) (39, 40). TeCV concentration in water in this study is slightly higher than that reported in northern Baltic rivers and estuaries (35) but one order of magnitude lower than reported decades ago in a river receiving effluent from bleached pulp mill effluent (18). The DAME level here is about half of that in northern Baltic water bodies (35) but one order of magnitude higher than in surface water of the Atlantic Ocean (41).

Spatial patterns of HMBs in water can offer some indications of their origin (fig. S6). Consistent with a marine source, TBA levels were much higher in the estuary (W10) than in the St. Lawrence River (W1 to W9) and in waters around Victoria (V6 to V10) than around Vancouver (V1 to V5) (fig. S6, A and B). This is consistent with reported elevated level in estuaries compared to riverine and offshore waters in northern Baltic estuaries (35). The anthropogenic PCA, on the other hand, had elevated levels in urban water e.g., in Port Moody (V1) in the inner Vancouver Harbour and in the city of Victoria (V8) and along the St. Lawrence River (W1 to W9) (fig. S6, C and D). While DAME’s distribution was quite uniform in Quebec waters (fig. S6F), higher levels were observed close to the mouth of the Fraser River in BC (V4 and V5; fig. S6E), which might implicate riverine runoff in delivering DAME from terrestrial environments to water. TeCV exhibited a similar pattern to DAME with an additional hot spot on the north shore of Burrard Inlet (V3; fig. S6G). Considering the similarity of DAME and TeCV in many regards, it is likely that the two compounds originate from similar sources.

The concentration data of HMBs in water and air allow us to investigate the air-water equilibrium status. Fugacities of HMBs in water (fW) and air (fA) were calculated from concentrations in water (Cw, mole per cubic meter) and air (CA, mole per cubic meter) and the temperature-adjusted water air equilibrium partitioning ratio (KWA) (table S15). Specifically, fW = CW·KWA·R·T while fA = CA·R·T, where R is the gas constant and T is temperature in kelvin. The ratio of fW/fA indicates the tendency for net deposition (<1) or volatilization (>1). We caution that the uncertainty in the KWA and in passive sampling rates, particularly for the PWS, renders these air-water exchange calculations somewhat uncertain. The fugacity ratios for the HMBs were similar in BC and QC (table S15). Ratios that greatly exceeded 1 (27 ± 17) indicate net volatilization of TBA, as has previously been reported in the Northern Baltic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean (10 to 94) (21, 42) but differs from near-equilibrium conditions reported for the Canadian Arctic (4). DAME and TeCV, with fW/fA ratios of 0.7 ± 0.4 and 1.3 ± 0.8, respectively, were close to air-water equilibrium. PCA is more likely to volatilize from water with a mean fW/fA ratio slightly above unity (5.7 ± 3.7).

DISCUSSION

Compared to anthropogenic organic contaminants, much less effort has been expended on investigating the sources and environmental fate of HMBs. Through a large geographical scope, an unusually large number of sampling sites, the inclusion of water, air and precipitation samples, and the focus on both spatial and seasonal patterns, the present investigation sought to advance knowledge on the origin and behavior of HMBs in the environment. The study provided support for earlier findings, such as the marine origin of TBA and the importance of anthropogenic sources for PCA. The former was confirmed by elevated atmospheric levels near the ocean, high seasonal variability associated with its production by marine organisms and fugacity ratios consistent with net volatilization from water. Support for the latter was mostly provided by higher PCA level in air and water of urban areas. Our study also generated data that challenge earlier hypotheses, such as the absence of (i) evidence linking TeCV with the paper and pulp industry or (ii) a relationship between atmospheric DAME and forest fires.

Our study provided evidence for the remarkable atmospheric LRT potential of TBA resulting in its presence far from the ocean. Our study further revealed the importance of evaporation from water for controlling atmospheric levels of HMBs that are largely believed to have terrestrial origins, such as DAME and TeCV. Empirical evidence for this includes (i) spatial patterns in the atmosphere that show higher levels at coastal sites rather than at sites in heavily forested regions, (ii) high levels of HMBs at the mouth of the Fraser River, (iii) a strong seasonality in air concentrations, with coastal sites sometimes showing a stronger relationship with temperature than inland sites, and (iv) higher HMB levels in Toronto during times when the air originates over Lake Ontario. We propose that even though HMBs such as DAME and TeCV are believed to originate in terrestrial environments, they mostly enter the atmosphere by evaporation from water. The transfer from terrestrial environments to lakes, rivers and coastal waters occurs by runoff of the HMBs itself as well as in the form of their phenolic precursors, which can then undergo O-methylation in the aquatic environment. Logging practices that involve the transport and storage of harvested wood in water could provide a short-cut for the transport of HMBs and their phenolic precursors from forest to water.

To test the plausibility of terrestrial runoff and volatilization from water being the main pathway for DAME to the atmosphere, we assessed the main environmental fate processes of DAME and its phenolic precursor [2,3,5,6-tetrachloro-4-methoxyphenol, drosophilin A (DA)] using a steady-state multimedia environmental fate model (text S4 and fig. S7) (43). As compounds naturally formed for presumably geological time scales, assuming that DAME and DA have achieved a steady state in the environment is highly plausible. We further assumed that DAME and DA originate solely in the terrestrial environment, i.e., 100% of their release occurred to soil. To account for the high uncertainty of the degradation half-life of DAME and DA, we performed two sets of simulations with the compounds being either highly persistent or readily degradable. The simulations suggest that DAME emitted to soil is approximately four times more likely to be transferred with runoff to water than to evaporate from the soil (fig. S7). In the case of DA, whose phenolic group is dissociated at environmental pH, runoff is even an order of magnitude more important than evaporation from soil (fig. S7). The simulations further suggest that even if DAME is emitted to soil, evaporation from water is a major fate process, with the evaporation flux from water exceeding the one from soil if DAME is reasonably persistent. While DA itself does not evaporate from water, we can infer that it could do so readily after undergoing O-methylation to DAME in water. Overall, these simulations lend support for the hypothesis that runoff of HMBs and their phenolic precursors occurs and is followed by volatilization of the HMB from water. The evaporating HMB is either transported to the water itself or is formed by O-methylation of its phenolic precursor in the water. Further details on the model simulation are given in the Supplementary Materials (text S4). We might expect that a similar behavior can also be attributed to PCA and its phenol precursor PCP.

It also implies that all four of the HMBs studied here tend to reach the atmosphere by volatilizing from water, even if there are different reasons for their presence in water: TBA is produced within sea water, DAME and probably also TeCV originate in forests and reach the water through natural runoff, and PCA originates from anthropogenic activities and reach water mostly through runoff from urban and industrial areas of PCP use.

Earlier work clearly demonstrated that a naturally produced compound such as DAME is persistent in the environment (10) and able to bioaccumulate in organisms (7–9). DAME and DA exhibit antimicrobial properties that may serve as the wood fungi’s chemical defense against organisms that compete for the same substrate (19).Therefore, it is possible that they exert toxic effects similar to those of other biocides. Although data on toxicity are limited, predictions from quantitative structure–activity relationship suggest that DAME has potential for mutagenic, developmental, and reproductive toxicity as well as acute toxicity and aquatic ecotoxicity not unlike those of many POPs (table S16). The current study demonstrated the ability for DAME and other HMBs not only to reach the atmosphere in notable amounts, regularly reaching concentrations that exceed those of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls by more than an order of magnitudes, but also to undergo substantial atmospheric LRT. It is not unreasonable to believe that DAME and other HMBs would meet the criteria applied to classify POPs under the Stockholm Convention and would be slated for global restrictions if they were man-made compounds. While obviously nothing can be done about the presence of naturally produced HMBs in the environment, it is valid to question whether they do not deserve more scientific attention, considering their ubiquity, abundance, and POP-like characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Passive air sampler networks

Two networks of PASs were established in Southwestern BC and Southern QC. A previously described PAS relying on styrene−divinylbenzene co-polymeric resin (commercial name XAD-2) as sorbent was used for sampling gas-phase HMBs (44). The East coast network comprised 71 unique sampling sites covering the St. Lawrence River valley from Montreal to Quebec City as well as the north and south shores of the St. Lawrence Estuary. The West coast network comprised 47 unique sampling sites across BC, with a focus on the lower mainland around Vancouver and the Canadian shore of the Salish Sea. As 19 and 47 field blanks were collected and 15 and 36 of the deployments were replicated in the East and West, respectively, a total of 235 PASs was extracted and analyzed.

Both networks comprise sampling sites in cities (urban sites), close to industrial facilities (industrial sites) and at locations away from anthropogenic sources (remote sites) (Fig. 1). PASs were installed on trees or existing man-made structures, generally 2 to 4 m above the ground. Deployments lasted 4 to 12 months (median, 9 months) during 2019–2022. Details on sampling site locations, deployment periods, and replication are provided in table S1. The retrieved PASs were stored in metal shipping tubes capped with Teflon tape–coated stoppers, sealed with Teflon tape, and stored in sealed bags at −20°C until analysis. During each deployment, the PAS housing contained two XAD-filled mesh cylinders, with one being analyzed and the other being archived.

Active air sampling and precipitation collection

Seasonal variability of HMBs in air was studied using AASs, whereby a glass-fiber filter (GFF) and a polyurethane foam (PUF)/XAD-2/PUF sandwich collected compounds in the particle and gas phase, respectively. Twelve 24-hour AASs were taken at monthly intervals on Saturna Island, BC (L43; Fig. 1) in the Salish Sea and close to Tadoussac, Quebec (close to S57; Fig. 1) on the North shore of the St. Lawrence Estuary. Forty-eight consecutive week-long AASs were taken on the campus of the University of Toronto Scarborough in the eastern suburbs of Toronto. Details on the three locations and sampling periods are provided in table S2. Precipitation was sampled monthly on Saturna Island and in Tadoussac with a wet deposition sampler during the same 12-month period as the AAS. Precipitation samples were collected in sample bottles containing 0.2 liter of dichloromethane.

Passive water sampling

PWSs with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) as sorbent, designed for sampling dissolved HMBs, were deployed at 10 unique sites in each of QC and BC from May to August 2021. Deployment sites were mainly in urban areas, i.e., coastal Vancouver and Victoria in BC, along the St. Lawrence River between Montreal and Quebec City and in the lower Estuary close to Rimouski. Counting replicated deployments at different depths and for different lengths of time, there were 48 PWSs. Before deployment, LPPE sheets were spiked with performance reference compounds (PRCs). The dissipation of these PRCs allows for the calculation of site- and compound-specific sampling rate for the target analytes. Details on PRCs and the treatment of LPPEs are available in text S5. Detailed information on the PWS sampling is given in table S14 and fig. S5 includes a map with sampling locations.

Sample extraction and pretreatment

The XAD-2 resin from the PASs, PUF–XAD-2 sandwiches from the AASs in Toronto, GFFs (particle phase) from the AASs on Saturna Island and Tadoussac and the GFFs from the precipitation samples were extracted using a 1:1 mixture of hexane and acetone using an accelerated solvent extractor (Dionex ASE 350, Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA) with the following settings: 1500 psi, 75°C, 6-min static cycle, 3 cycles per sample, 100% flush volume, 240-s purge with ultrahigh purity nitrogen. The PUF–XAD-2 sandwiches from the AASs on Saturna Island and Tadoussac were Soxhlet extracted using 375 ml of dichloromethane for 20 to 22 hours. The precipitation samples were filtered through 0.7-μm GFFs. Then, each 800 ml of filtered precipitation samples was subjected to liquid-liquid extraction three times using 50 ml of dichloromethane until all sample was extracted and the resulting extracts were combined. The LDPE from PWSs were extracted by wiping the sheets with pre-extracted Kimwipes, placing them into a baked 40-ml amber glass vial, adding 30 ml of hexane, shaking for 5 min, and then soaking overnight. This procedure was repeated twice, and the extracts were combined.

Before extraction, 40 ng of 13C-pentachlorobenzene (13C-PeCB), 13C-hexachlorobenzene (13C-HCB), and 13C-PCA was spiked as surrogates onto all samples. In the case of the PWSs, this step was performed after the Kimwipe cleaning and before the addition of hexane, whereby 5 min were allocated to allow the surrogates to sorb into PE sheets. The volumes of all the extracts were reduced to ~1 ml in iso-octane using a rotary evaporator. The concentrated extracts then were passed through sodium sulfate (baked at 450°C overnight) to remove water residues. Extracts were again concentrated to 1 ml using a stream of nitrogen and lastly adjusted to 0.5 ml. 13C-PCB105 (15 ng) was added to extracts as injection standard before instrument analysis.

The HMBs analyzed in all PASs, samples taken with AASs, PWSs, and precipitation samples taken in this study included DBA, TBA, PCA, TeCV, and DAME. Selected extracts were additionally analyzed for 4-MoCV, 3-MoCV, DiCV, and TriCV. Detailed information on materials, solvents, and chemical standards is given in table S17.

Instrument analysis

The analysis for the HMBs was done using a gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometer (Agilent 7000A Triple Quadrupole GC-MS) operated in Electron Impact Ionization mode. A capillary DB-5 column (Agilent J&W Scientific, 30 m by 0.25-mm i.d. by 0.25-μm film thickness) was used to separate the HMBs. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1, and 2 μl of extract was injected in pulsed splitless mode at 250°C. The oven temperature program was as follows: initial oven temperature was 80°C and then raised to 160°C at 20°C min−1, raised to 230°C at 3°C min−1, and raised to 300° at 20°C min−1 and held for 10 min. The ion source and transfer line temperature were set at 250° and 280°C, respectively. The transitions and collision energies of the MS/MS are provided in table S18.

Quality assurance/quality control

All glassware was machine-washed with detergent, rinsed with deionized water, and baked for 24 hours before use. All other experimental materials coming in contact with samples or extracts were cleaned and rinsed with acetone and hexane or dichloromethane three times. A total of more than 20 procedure blanks were prepared along with each batch of extraction. HMBs were not detected in any procedure and solvent blanks. Only low levels of DAME and TBA were detected in some PAS field blanks, which were subtracted from amounts quantified in exposed samplers. MDLs were calculated as three times the SDs of levels in field blanks, if a compound was detected in those blanks [with a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) > 3]; otherwise, the MDLs were calculated as the concentrations at which the S/N is 10. The MDLs for PASs, precipitation, ASSs, and PWSs are summarized in the Supplementary Materials. The recoveries of surrogates (13C-PeCB, 13C-HCB, and 13C-PCA) in different samples were within the acceptable range (table S19).

Data analysis

Volumetric air concentrations averaged over the time period of a PAS’s deployment were calculated by dividing the quantified amount by the product of the deployment period in days and a compound-specific sampling rate in cubic meter per day. Passive air sampling rates for the HMBs were obtained from a calibration study conducted at the time of the AAS sampling in Toronto (45). The sampling rates for PWSs was calculated on the basis of equations by Booij and Smedes et al. (46, 47). Maps and visualizations of spatial patterns were made using Geobasemap within MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Crooks, A. Costa, Y. Lapointe, L.-G. Esquilat, J. Praud, S. Vigneron, F. Gagnon, J. Pritchard, A. Colussi, C. Boutot, B. Cayouette, F. Moualek, F. Bélanger, C. Lapierre, F. Ledoux, S. Turgeon, S. Duquette, and the CAPMON team for assistance in deploying samplers and providing facilities/permissions to the sampling locations. We are also grateful to A. Sangion for help with the environmental model simulation.

Funding: This work was supported by Grant and Contribution Agreements (GCXE20S008, GCXE20S010, and GCXE20S011) with Environment and Climate Change Canada under the Whale Recovery Initiative.

Author contributions: F.Z. and Y.L., with assistance by J.O., prepared and analyzed the passive air samplers (PASs) and the Toronto AASs. F.Z. and Y.L. also took the Toronto AAS. C.S. prepared and analyzed all samples from Saturna Island and Tadoussac as well as the PWSs. K.L. and F.A.P.C.G. deployed/retrieved PASs and PWSs in BC. A.B.C., A.D.C., Z.L., N.A., H.H., F.Z., and F.W. deployed/retrieved PASs and PWSs in Quebec. Y.D.L. prepared standards and provided guidance on sampling and sample analyses. F.Z. compiled and interpreted data, with input from F.W. F.Z. and F.W. wrote the manuscript with input by the other coauthors. H.H. coordinated the project.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Tables S1 to S20

Figs. S1 to S7

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.T. F. Bidleman, A. Andersson, L. M. Jantunen, J. R. Kucklick, H. Kylin, R. J. Letcher, M. Tysklind, F. Wong, A review of halogenated natural products in Arctic, Subarctic and Nordic ecosystems. Emerg. Contam. 5, 89–115 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.U. Führer, A. Deißler, J. Schreitmüller, K. Ballschmiter, Analysis of halogenated methoxybenzenes and hexachlorobenzene (HCB) in the picogram m−3 range in marine air. Chromatographia 45, 414–427 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 3.K. Arinaitwe, B. T. Kiremire, D. C. G. Muir, P. Fellin, H. Li, C. Teixeira, D. N. Mubiru, Legacy and currently used pesticides in the atmospheric environment of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 543, 9–18 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.F. Wong, L. M. Jantunen, M. Pućko, T. Papakyriakou, R. M. Staebler, G. A. Stern, T. F. Bidleman, Air−water exchange of anthropogenic and natural organohalogens on International Polar Year (IPY) expeditions in the Canadian Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 876–881 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U. Führer, K. Ballschmiter, Bromochloromethoxybenzenes in the marine troposphere of the Atlantic Ocean: A group of organohalogens with mixed biogenic and anthropogenic origin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 2208–2215 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 6.T. Bidleman, A. Andersson, E. Brorström-Lundén, S. Brugel, L. Ericson, K. Hansson, M. Tysklind, Halomethoxybenzenes in air of the Nordic region. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 13, 100209 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.J. Hiebl, K. Lehnert, W. Vetter, Identification of a fungi-derived terrestrial halogenated natural product in wild boar (Sus scrofa). J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 6188–6192 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A. Renaguli, S. Fernando, P. K. Hopke, T. M. Holsen, B. S. Crimmins, Nontargeted screening of halogenated organic compounds in fish fillet tissues from the Great Lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 15035–15045 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.A. Renaguli, S. Fernando, T. M. Holsen, P. K. Hopke, D. H. Adams, G. H. Balazs, T. T. Jones, T. M. Work, J. M. Lynch, B. S. Crimmins, Characterization of halogenated organic compounds in pelagic sharks and sea turtles using a nontargeted approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 16390–16401 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.L. A. J. Garvie, B. Wilkens, T. L. Groy, J. A. Glaeser, Substantial production of drosophilin A methyl ether (tetrachloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene) by the lignicolous basidiomycete Phellinus badius in the heartwood of mesquite (Prosopis juliflora) trees. Sci. Nat. 102, 18 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A. H. Neilson, A. S. Allard, S. Reiland, M. Remberger, A. Tärnholm, T. Viktor, L. Landner, Tri- and tetra-chloroveratrole, metabolites produced by bacterial O-methylation of tri- and tetra-chloroguaiacol: An assessment of their bioconcentration potential and their effects on fish reproduction. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 41, 1502–1512 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 12.A. Norman Haldén, J. R. Nyholm, P. L. Andersson, H. Holbech, L. Norrgren, Oral exposure of adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) to 2,4,6-tribromophenol affects reproduction. Aquat. Toxicol. 100, 30–37 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.J. Fu, Y. Guo, M. Wang, L. Yang, J. Han, J. S. Lee, B. Zhou, Bioconcentration of 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP) and thyroid endocrine disruption in zebrafish larvae. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 206, 111207 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AMAP. Assessment 2016: Chemicals of Emerging Arctic Concern; Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme: Oslo, Norway (2017).

- 15.A. S. Allard, M. Remberger, A. H. Neilson, Bacterial O-methylation of halogen-substituted phenols. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53, 839–845 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.W. J. Sim, S. H. Lee, I. S. Lee, S. D. Choi, J. E. Oh, Distribution and formation of chlorophenols and bromophenols in marine and riverine environments. Chemosphere 77, 552–558 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme. SC-7/13: Listing of pentachlorophenol and its salts and esters (2015); http://chm.pops.int/TheConvention/ ConferenceoftheParties/ReportsandDecisions/tabid/208/Default.aspx (accessed 3 March 2021).

- 18.B. G. Brownlee, G. A. MacInnis, L. R. Noton, Chlorinated anisoles and veratroles in a Canadian river receiving bleached kraft pulp mill effluent. Identification, distribution, and olfactory evaluation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 2450–2455 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 19.P. J. M. Teunissen, H. J. Swarts, J. A. Field, The de novo production of drosophilin A (tetrachloro-4-methoxyphenol) and drosophilin A methyl ether (tetrachloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene) by ligninolytic basidiomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47, 695–700 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.H. Kylin, T. Svensson, S. Jensen, W. M. J. Strachan, R. Franich, H. Bouwman, The trans-continental distributions of pentachlorophenol and pentachloroanisole in pine needles indicate separate origins. Environ. Pollut. 229, 688–695 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.T. F. Bidleman, K. Agosta, A. Andersson, P. Haglund, O. Nygren, M. Ripszam, M. Tysklind, Air–water exchange of brominated anisoles in the northern Baltic Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 6124–6132 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.T. F. Bidleman, E. Brorström-Lundén, K. Hansson, H. Laudon, O. Nygren, M. Tysklind, Atmospheric transport and deposition of bromoanisoles along a temperate to Arctic gradient. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 10974–10982 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.L. Shen, F. Wania, Y. D. Lei, C. Teixeira, D. C. G. Muir, T. F. Bidleman, Atmospheric distribution and long-range transport behavior of organochlorine pesticides in North America. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 409–420 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.T. F. Bidleman, H. Laudon, O. Nygren, S. Svanberg, M. Tysklind, Chlorinated pesticides and natural brominated anisoles in air at three northern Baltic stations. Environ. Pollut. 225, 381–389 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.E. Atlas, K. Sullivan, C. S. Giam, Widespread occurrence of polyhalogenated aromatic ethers in the marine atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 20, 1217–1220 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 26.J. Melcher, M. Schlabach, M. S. Andersen, W. Vetter, Contrasting the seasonal variability of halogenated natural products and anthropogenic hexachlorocyclohexanes in the southern Norwegian atmosphere. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 55, 547–557 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R. Wittlinger, K. Ballschmiter, Studies of the global baseline pollution XIII. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 336, 193–200 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 28.U. Führer, A. Führer, K. Ballschmiter, Determination of biogenic halogenated methyl-phenyl ethers (halogenated anisoles) in the picogram m−3 range in air. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 354, 333–343 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D. T. Waite, N. P. Gurprasad, A. J. Cessna, D. V. Quiring, Atmospheric pentachlorophenol concentrations in relation to air temperature at five Canadian locations. Chemosphere 37, 2251–2260 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Pollutant Release Inventory–Geographic Distribution of Reporting Facilities (computer file) (Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2016).

- 31.G. Shen, S. Tao, S. Wei, Y. Zhang, R. Wang, B. Wang, W. Li, H. Shen, Y. Huang, Y. Yang, W. Wang, X. Wang, S. L. M. Simonich, Retene emission from residential solid fuels in China and evaluation of retene as a unique marker for soft wood combustion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 4666–4672 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.F. Wania, J. E. Haugen, Y. D. Lei, D. Mackay, Temperature dependence of atmospheric concentrations of semivolatile organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 1013–1021 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 33.R. M. Hoff, K. A. Brice, C. J. Halsall, Nonlinearity in the slopes of Clausius−Clapeyron plots for SVOCs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 1793–1798 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 34.W. Vetter, S. Kaserzon, C. Gallen, S. Knoll, M. Gallen, C. Hauler, J. F. Mueller, Occurrence and concentrations of halogenated natural products derived from seven years of passive water sampling (2007–2013) at Normanby Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 137, 81–90 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.T. Bidleman, K. Agosta, A. Andersson, S. Brugel, L. Ericson, K. Hansson, O. Nygren, M. Tysklind, Sources and pathways of halomethoxybenzenes in northern Baltic estuaries. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1161065 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 36.D. A. Alvarez, W. L. Cranor, S. D. Perkins, R. C. Clark, S. B. Smith, Chemical and toxicologic assessment of organic contaminants in surface water using passive samplers. J. Environ. Qual. 37, 1024–1033 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.S. C. Nallanthigal, S. Herrera, M. J. Gómez, A. R. Fernández-Alba, Determination of hormonally active chlorinated chemicals in waters at sub μg/L level using stir bar sorptive extraction-liquid desorption followed by negative chemical ionization-gas chromatography triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 94, 48–64 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Y. Tang, Z. Wu, Y. Zhang, C. Wang, X. Ma, K. Zhang, R. Pan, Y. Cao, X. Zhou, Cultivation-dependent and cultivation-independent investigation of O-methylated pollutant-producing bacteria in three drinking water treatment plants. Water Res. 231, 119618 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.G. Zhong, Z. Xie, A. Möller, C. Halsall, A. Caba, R. Sturm, J. Tang, G. Zhang, R. Ebinghaus, Currently used pesticides, hexachlorobenzene and hexachlorocyclohexanes in the air and seawater of the German Bight (North Sea). Environ. Chem. 9, 405 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 40.X. Zhang, M. Robson, K. Jobst, M. Pena-Abaurrea, A. Muscalu, S. Chaudhuri, C. Marvin, I. D. Brindle, E. J. Reiner, P. Helm, Halogenated organic contaminants of concern in urban-influenced waters of Lake Ontario, Canada: Passive sampling with targeted and non-targeted screening. Environ. Pollut. 264, 114733 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.J. Schreitmüller, K. Ballschmiter, Air-water equilibrium of hexachlorocyclohexanes and chloromethoxybenzenes in the North and South Atlantic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29, 207–215 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O. Pfeifer, K. Ballschmiter, Halogenated methyl-phenyl ethers (HMPE; halogenated anisoles) in the marine troposphere and in the surface water of the Atlantic Ocean: An indicator of the global load of anthropogenic and biogenic halophenols. Organohalogen Compd. 57, 483–486 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 43.EAS-E Suite (Ver.0.96 - BETA, release November, 2022); www.eas-e-suite.com. Accessed [2023]. Developed by ARC Arnot Research and Consulting Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 44.F. Wania, L. Shen, Y. D. Lei, C. Teixeira, D. C. G. Muir, Development and calibration of a resin-based passive sampling system for monitoring persistent organic pollutants in the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 1352–1359 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Y. Li, F. Zhan, Y. D. Lei, C. Shunthirasingham, H. Hung, F. Wania, Field calibration and PAS-SIM model evaluation of the XAD-based passive air sampler for semi-volatile organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 9224–9233 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.K. Booij, H. E. Hofmans, C. V. Fischer, E. M. Van Weerlee, Temperature-dependent uptake rates of nonpolar organic compounds by semipermeable membrane devices and low-density polyethylene membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 361–366 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.K. Booij, F. Smedes, An improved method for estimating in situ sampling rates of nonpolar passive samplers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 6789–6794 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.K. Breivik, M. S. McLachlan, F. Wania, The emissions fractions approach to assessing the long-range transport potential of organic chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 11983–11990 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.K. Mansouri, C. M. Grulke, R. S. Judson, A. J. Williams, OPERA models for predicting physicochemical properties and environmental fate endpoints. J. Chem. 10, 10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.P. Bohlin-Nizzetto, A. Wenche, Monitoring of environmental contaminants in air and precipitation, Annual Report 2015 (NILU report, 2016).

- 51.N. Ulrich, S. Endo, T. N. Brown, N. Watanabe, G. Bronner, M. H. Abraham, K. U. Goss, UFZ-LSER database v 3.2.1 [Internet], Leipzig, Germany, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research-UFZ. 2017 [accessed on 14 January 2023]. Available from www.ufz.de/lserd.

- 52.VEGA-QSAR: AI inside a platform for predictive toxicology. Proceedings of the workshop “Popularize Artificial Intelligence 2013”; www.vegahub.eu/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Tables S1 to S20

Figs. S1 to S7

References