Abstract

RAP80 has been characterized as a component of the BRCA1-A complex and is responsible for the recruitment of BRCA1 to DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). However, we and others found that the recruitment of RAP80 and BRCA1 were not absolutely temporally synchronized, indicating that other mechanisms, apart from physical interaction, might be implicated. Recently, liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) has been characterized as a novel mechanism for the organization of key signaling molecules to drive their particular cellular functions. Here, we characterized that RAP80 LLPS at DSB was required for RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment. Both cellular and in vitro experiments showed that RAP80 phase separated at DSB, which was ascribed to a highly disordered region (IDR) at its N-terminal. Meanwhile, the Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains that quickly formed after DSBs occur, strongly enhanced RAP80 phase separation and were responsible for the induction of RAP80 condensation at the DSB site. Most importantly, abolishing the condensation of RAP80 significantly suppressed the formation of BRCA1 foci, encovering a pivotal role of RAP80 condensates in BRCA1 recruitment and radiosensitivity. Together, our study disclosed a new mechanism underlying RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment, which provided new insight into the role of phase separation in DSB repair.

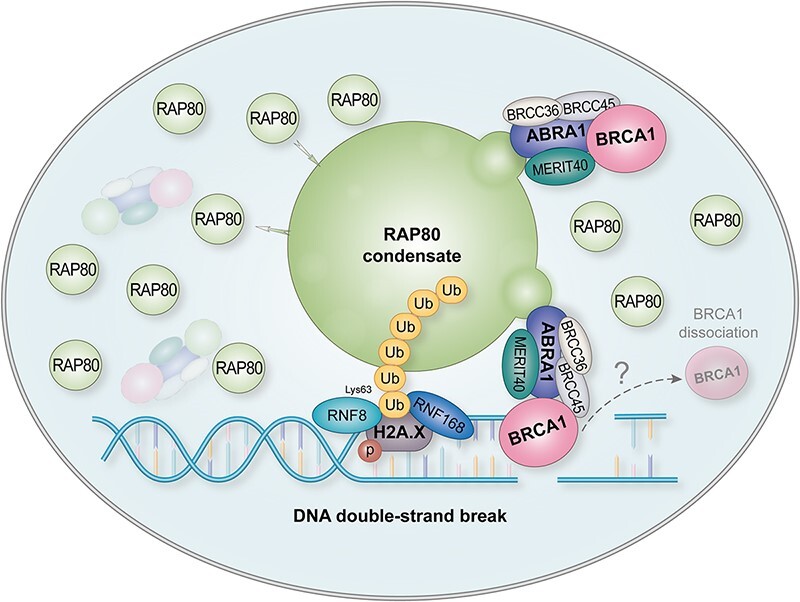

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) is an important driving force for membraneless organelles formation and plays a pivotal role in many biological processes (1–3). When soluble protein undergoes LLPS, it condenses into a dense phase that forms liquid-like droplets. Recent studies disclosed the essential role of the intrinsically disordered region (IDR) in protein LLPS, showing that the condensing protein was much more disordered than the entire proteome (4). There are some characteristics presented in IDR, e.g. typical IDRs are rich in charged amino acids (5), elastin-like poly-peptides (ELPs) are enriched in hydrophobic amino acids (6) and prion-like domains contain repetitive peptides (7,8). Indeed, we and other groups found that LLPS functioned pivotal roles for DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair (9,10) and some essential DSB repair factors underwent LLPS during their DSB repair process (11). For example, upon DNA damage, MRNIP condensates move to the damaged DNA rapidly to accelerate the binding of DNA lesions by the concentrated MRN complex (12); damage-induced lncRNAs (dilncRNAs) recruit 53BP1 to DNA lesions and promote the formation of DNA damage-induced foci through LLPS (13) and 53BP1 condensation enhances radiation-induced p53 activation (14). In cancer cells, many of these protein condensations are accelerated, resulting in the failure of genotoxicity-based anti-cancer therapy (15).

BRCA1 is a well-known tumor suppressor gene, which is essential for homologous recombination (HR)-mediated DSB repair. BRCA1 dysfunction leads to the inefficiency of DNA damage repair, resulting in genome instability and tumorigenesis (16). BRCA1 is the central component of at least four complexes, including the RAP80-containing BRCA1-A complex. BRCA1-A complex is composed of RAP80, ABRA1, MERIT40, BRCC45 and BRCC3 (17,18). BRCA1-A complex is responsible for the recruitment of BRCA1 to DSB through the interaction between ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) of RAP80 and the Lys63 poly-ubiquitin chains on the γH2A.X. RAP80 is integrated into the BRCA1-A complex through its ABRA1-interacting region (AIR) (19). RAP80 protein contains two UIMs, UIM1 (residues 80–97) and UIM2 (residues 103–125), flanked by 5 amino acids (20). Mutation or depletion of the UIM disrupts the ubiquitin-binding capacity of RAP80 and diminished its recruitment to DSB lesions (21,22). Furthermore, studies revealed that small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) interacting motif (SIM)-mutated RAP80 displayed decreased formation of IR-induced foci, indicating that SIM of RAP80 and DNA damage-induced SUMOylation were also required for recruiting RAP80 to damaged DNA (23,24). However, although RAP80 was identified as a component of the BRCA1-A complex, several studies revealed that the dynamic of RAP80 at DSB was different from BRCA1 as well as other proteins in the BRCA1-A complex (25), suggesting that the role of RAP80 in BRCA1-A complex recruitment and DSB repair need to be further investigated.

In this study, we identified that the LLPS potential of RAP80 was required for its accumulation at the DSB site and RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment. The association between RAP80 and Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains increased multivalent interactions to induce RAP80 LLPS at the DNA damage site. Significantly, RAP80 LLPS enhanced the radio-resistance of tumor cells, indicating that RAP80 may be a potential target for sensitizing tumors to radiotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and tissues

HEK 293T, U2-OS and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (G7513, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 100units/ml penicillin-streptomycin (15140122, HyClone, South Logan, UT, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). HCT116 cells were cultured in McCOY’S 5A medium (SH30200.01, Cytiva, South Logan, UT, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2.

RAP80 knocked out HeLa and HCT116 cells were constructed using CRISPR/cas9. Briefly, cells were infected with lentivirus containing RAP80-targeting sgRNA for 48 h before being selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin for ten days. Cells infected with lentivirus derived from lenti-CRISPRv2 empty vector were used as the wildtype control.

Human colorectal tissues were obtained from the Tissue Bank of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University. The tumor tissues were obtained from patients with rectal cancer who received neoadjuvant radiotherapy followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) surgery. The radiation proctitis tissues were obtained from patients with radiation proctitis who underwent resection of rectal lesion. The control tissues for radiation proctitis were the distal normal tissue from rectal cancer resection. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.

Construction of plasmids

Human cDNA was cloned into pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro, pGEX-6P-2 or pcDNA 3.0. The base vectors were engineered to contain an N-terminal Flag and a C-terminal mEGFP, mCherry, or mCherry-CRY2 followed by stop codon TGA. Encoding cDNA sequences generated by PCR were inserted in-frame in front of mEGFP, mCherry or mCherry-CRY2. The proteins used in this paper were as follows: full-length RAP80 (WT), amino acids 1–719; IDR1, amino acids 1–254; IDR2, amino acids 313–501; IDR3, amino acids 587–719; ΔIDR1, amino acids 255–719; (SIM+UIM), amino acids (1-50)+(80–125); (IDR1+AIR), amino acids (1-254)+(265–330); (SIM+UIM+AIR), amino acids (1–50)+(80–125)+(265–330); ΔUIM, amino acids (1-79)+(126–719); 4×UIM, amino acids (1-125)+(80–125)+(80–125)+(80–719). To generate sgRAP80 cell lines, a lenti-CRISPRv2 vector was used to create a plasmid targeting the RAP80 genomic locus by the following sgRNA sequence: ATTGTGATATCCGATAGTGA.

Live-cell imaging

Cells were cultured in glass-bottom dishes one day before transfection with the plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection, live-cell images were collected through Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope (64× oil objective) equipped with an incubation chamber to provide an atmosphere of 37°C with 5% CO2.

1,6-Hexanediol treatment: cells were cultured on glass-bottom dishes, and transfected with plasmids for 24 h before observation. Culture medium was removed and replaced with medium containing 6% or 10% 1,6-hexanediol. After incubation for indicating times, the 1,6-hexanediol-containing medium was removed and replaced with complete medium (26–28). Images were captured in a time series mode using Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope.

ATP depletion: complete medium was replaced with glucose-free DMEM (11966025, Gibco). After 2h incubation, medium containing 5 mM 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (HY-13966, MedChemExpress, MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and 126 nM oligomycin (495455, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was added to the dish. Cells were cultured for another 2 h before acquisition.

OptoIDR assay: cells were transfected with RAP80 IDR1-mCherry-CRY2 or NLS-ΔIDR1-mCherry plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (11668019, Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, droplet formation was induced with blue light (488 nm, 50% laser power) every 2 s during the imaging process, and images were captured every 2.5 s.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP was performed using 488 or 561 nm laser module. Bleaching was performed at 100% laser power, and images were collected every 2.5 s. Images were further processed by ZEN2 software. For FRAP of OptoIDR assays were performed after stimulation with blue light for 60 s, and images were captured every 2.5 s without blue light.

Protein expression and purification

GST-RAP80-mEGFP, GST-RAP80-mCherry, GST-IDR1-mCherry, GST-ΔIDR1-mCherry, GST-ΔUIM-mCherry, GST-4×UIM-mCherry proteins were expressed in the Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3). Cultures were grown at 37°C in a percussion incubator until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Then, IPTG was added to reach a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and cultures were grown at 25 °C for 12 h in a percussion incubator. After centrifugation, cells were collected and resuspended in pre-chilled Lysis buffer (1 M NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, lysed by sonication and then centrifuged twice at 15 000 × g for 15 min to remove the insoluble substances. The supernatant was applied to GST-tagged purification resin (P2253, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) at 4°C for 3 h, followed by three washes with Lysis buffer. Then Elution buffer (25 mM GSH, 1 M NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10% glycerol) was applied to elute the protein. Concentrated proteins were stored at −80 °C. All purification steps were performed on ice or at 4°C. Poly-ubiquitin chains were given by Prof. Lei Liu (Tsinghua University) as a gift. mEGFP proteins were generated in our previous study (12).

In vitro droplet assay

For assays with PEG 8000 and Ficoll 400, GST-RAP80-mEGFP protein was diluted to the intended concentration in buffers containing 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 and 150 mM NaCl with or without LLPS enhancer. To examine the influence of salt concentration, GST-RAP80-mEGFP protein was diluted to 5 μm in 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 containing NaCl at the indicated concentration. To examine the influence of protein concentration, GST-RAP80-mEGFP protein was diluted to the indicated concentration in 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 containing 150 mM NaCl. To examine the influence of pH, the GST-RAP80-mEGFP protein was added to 25 mM Tris–HCl of the intended pH containing 150 mM NaCl. Droplet assays were performed in a reaction volume of 20 μl in PCR tubes mixed by pipetting. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 20°C for 10 min and then pipetted onto glass slides for observation. Images were captured using Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope with a 64× oil objective and further processed by ZEN2 software. Fluorescence intensity was measured by Image J.

Atomic force microscope imaging (AFM)

AFM images were captured in tapping mode using an AFM instrument (Dimension FastScan Bio, Bruker, Germany) equipped with a high-resonance microscope. The microscope was used to detect and select GST-RAP80-mEGFP droplets for nanoscale imaging with AFM. AFM imaging conditions were: scan size, 5.00 × 5.00 μm2; scan rate, 0.501 Hz; pixel size, 20 × 20 pixel2. All imaging were performed at room temperature. NanoScope Analysis software (Version 1.40, Bruker Corporation) was used to process the images and data.

Western blotting (WB)

Whole-cell extracts were obtained using RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 1% NP-40; 0.5% Na-deoxycholate) supplemented with protease inhibitor (04693132001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Biosharp, BL615A, China). The primary antibody used were as followed: anti-RAP80 (14466, CST, 1:1000); anti-BRCA1 (sc-6954, Santa Cruz, 1:200); anti-ABRA1 (14366, Proteintech, 1:2000); anti-αTubulin (66031, Proteintech, 1:2000); anti-Flag (740001, Thermo, 1:2000); anti-GST (66001, Proteintech, 1:1000); anti-ubiquitin (3936 s, CST, 1:1000); anti-Lys63-linked ubiquitin chain (5621s, CST, 1:1000); anti-Lys48-linked ubiquitin chain (8081s, CST, 1:1000). Images were captured with a ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-rad). Blots images were processed using Image Lab software.

GST pull-down

GST-RAP80-mCherry, GST-IDR1-mCherry, and GST-(SIM+UIM)-mCherry proteins were incubated with K63 Ub9–10 in a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 for 10 min, respectively. Then the mixtures were applied to GST-tagged purification resin (SA008100, Smart-Lifesciences, Changzhou, China) at 4°C for 3 h, followed by three washes with 1× PBS. At last, 1× SDS Loading buffer (E151-05, Genstar) was applied to resuspend the resin, and the mixtures were heated to 100°C for 20 min (until the resin was completely melted) for denaturation before SDS-PAGE analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

HeLa sgRAP80 cells were transfected with Flag-RAP80-mEGFP for 36h before being exposed to X-Ray (5Gy). After 4h of recovery, cells were collected and lysed using IP-lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 5% glycerol and protease inhibitor cocktail) at 4°C for 20 min, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation (13 000 × g, 4°C, 12 min). Then, cell lysates were mixed with Anti-FLAG® M2 Magnetic Beads (M8823, Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) and rotated at 4°C for 3 h. After five times washing with IP-lysis buffer, immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted from beads with 50 μl 100 mM glycine (pH 3.5), boiled in 1×SDS loading buffer, resolved on SDS-PAGE gel, and subjected to western blotting analysis.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (DF0135, Leagene, Beijing, China) for 15 min at room temperature (RT), washed three times (5min once) with 1×PBS, blocked in blocking buffer (5% goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1×PBS) for at least one hour at RT or 4°C overnight, and incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at RT or 4°C overnight. After three times washes in 1 × PBS, the coverslips were treated with secondary antibodies tagged with Alexa Fluor 488, 555, or 647 (4408S, 4413S, or 4414S, CST) for 1 h at RT in the dark. Cells were washed twice in PBS and then stained with DAPI for 5min (D9542, Sigma-Aldrich,1:1000). Images were collected using an LSM880 Zeiss confocal microscope. The primary antibodies used in this paper targeted the following proteins: anti-RAP80 (14466, CST, 1:200), anti-p-H2A.X (80312S, CST, 1:500), anti-BRCA1 (sc-6954, Santa Cruz, 1:50), anti-CCNA2 (MU170815, Abmart, 1:100).

Detection of chromosomal aberrations

Cells were irradiated with 1 Gy X-ray and recovered for 4 h, followed by incubation with 100 ng/ml colcemid at 37°C for 3 h. Then, cells were resuspended in pre-warmed 75 mM KCl solution and incubated at 37°C for 23min, followed by the addition of fixative solution (methanol/acetic acid, 3:1). Cells suspension was dropped onto pre-chilled slides to make chromosome preparations. The slides were air-dried overnight, digested by 0.05% trypsin for 10s, and chromosomal aberrations were examined in Giemsa-stained metaphases under an oil-immersion objective. At least 30 chromosomes were examined for each group, and chromosomal abnormalities were scored at 100× magnification.

DSB repair reporter

The DSB repair reporter assay was conducted as described previously (29). In brief, cells were transfected with pLCN DSB Repair Reporter (Addgene plasmid #98895), pCAGGS DRR mCherry Donor EF1a BFP (Addgene plasmid #98896), and pCBASceI plasmid (Addgene plasmid #26477) for 72 h before fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (these plasmids were gifts from Jan Karlseder). BFP-positive cells were gated for mCherry or GFP analysis.

Statistical analysis

Colony formation assay and DDR assay were repeated independently three times. IF and in vitro droplets assays were repeated twice. Statistical analyses for each experiment were indicated in the respective figure legends. Data were presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and Log-rank tests were performed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) to identify prognostic factors. All other statistical tests were two-sided and were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

RAP80 forms liquid-like condensates in nucleus

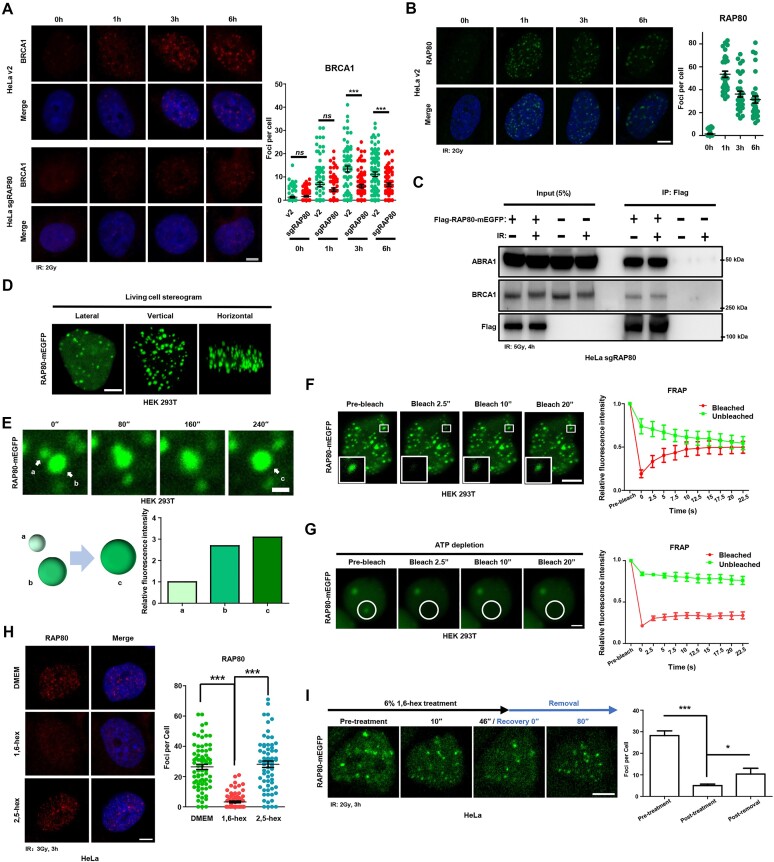

RAP80 had been characterized as a component of the BRCA1-A complex, and was responsible for the recruitment of BRCA1 to ionizing radiation-induced foci (IRIF) (20,30). Consistently, our results showed that after IR (X-ray), BRCA1 formed foci rapidly, whereas in HeLa sgRAP80 cells, IR-induced BRCA1 foci were significantly diminished (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1). Meanwhile, we noticed that the changes of BRCA1 and RAP80 foci post-IR were asynchronous. RAP80 IRIF was induced rapidly at 1h post-IR, and its number peaked at 1h and was continuously reducing post 1h, whereas the number of BRCA1 IRIF reached its peak at 3h post-IR (Figure 1A, B). Most importantly, CoIP assay showed that the radiation had no influence on the interaction between RAP80 and BRCA1 (Figure 1C), suggesting that RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment might employ other mechanisms apart from physical interaction.

Figure 1.

RAP80 forms liquid-like condensates in the nucleus. (A, B) HeLa cells were exposed to 2 Gy irradiation and fixed at the indicated time before IF analysis. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) CoIP assay showed the association of Flag-RAP80-mEGFP, BRCA1 and ABRA1 in HeLa sgRAP80 cells. (D) Confocal image 3D reconstruction of RAP80-mEGFP droplets in the nucleus. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Confocal image sequence showing the fusion between adjacent RAP80-mEGFP foci in the nucleus. The quantification data showed the fluorescence intensity of droplet a, b and c. Scale bar 5 μm. (F) FRAP assay of RAP80-mEGFP puncta in HEK 293T cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (G) ATP depletion abolished the FRAP of RAP80 droplets in HEK 293T cells. Scale bar, 2 μm. (H) 1,6-Hexanediol treatment disrupted endogenous RAP80 foci in HeLa cells. 2,5-hexanediol was used as a negative control. Scale bar, 5μm. I, exogenous RAP80 puncta were disrupted by 1,6-hexanediol and recovered after 1,6-hexanediol removal in HeLa cells. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Recently, studies have reported that DNA repair molecules may undergo liquid-liquid phase separation at DSB site (12). As RAP80 was also a highly disordered protein, we hypothesized that RAP80 may be recruited to IRIF in this manner. Living cell imaging with fluorescence microscopy showed that over-expressed RAP80-mEGFP fusion protein formed obvious puncta in HEK 293T cells without IR treatment (Figure 1D). Thin layer scanning and 3D reconstruction of the RAP80-mEGFP-expressing cells showed that RAP80-mEGFP formed spherical condensates. In particular, the fusing event between adjacent RAP80-mEGFP condensates indicated a liquid-like property (Figure 1E). The dynamic exchange between condensates and the surroundings has been considered a characteristic of LLPS, which is an ATP-dependent process. Consistently, RAP80-mEGFP condensates displayed a high rate of FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching) (Figure 1F), whereas ATP depletion via glucose deprivation and oligomycin treatment largely reduced the number, as well as the FRAP rate of RAP80-mEGFP condensates (Figure 1G). Additionally, RAP80-mEGFP condensates could be disrupted by 1,6-hexanediol treatment, a reagent known to disrupt liquid-like condensates, while recovering after 1,6-hexanediol removal (31) (Figure 1H, I). All these results indicate that RAP80 forms liquid-like condensates in the nucleus, which are consistent with the previously reported properties of LLPS.

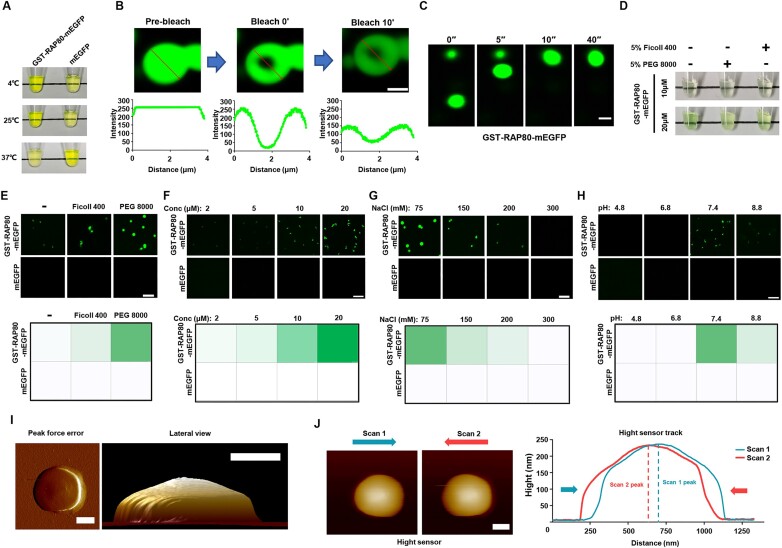

RAP80 forms condensate in vitro

To further verify whether RAP80 formed condensates in vitro, GST-RAP80-mEGFP recombinant protein was purified (Sup Figure 2A). When diluted in buffers containing 150mM NaCl, GST-RAP80-mEGFP protein muddied the solution in a temperature-dependent manner (Figure 2A). Observation of this solution under fluorescence microscope revealed that GST-RAP80-mEGFP formed liquid-like droplets, in which FRAP and the fusion among adjacent droplets were observed (Figure 2B, C). PEG 8000 and Ficoll 400 were used to mimic the crowding situation of the intracellular environment, which further strengthened the formation of GST-RAP80-mEGFP droplets (Figure 2D, E). Phase separation of RAP80 was positively correlated with protein concentration, and suppressed by a high salt concentration (Figure 2F, G; Supplementary Figure 2B). Proper pH was also required for the formation of RAP80 condensates (Figure 2H). RAP80 condensate was characterized as a droplet with a smooth surface by Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) (Figure 2I). When analyzed with AFM in a contact mode, the height curves from the bidirectional scan were slightly shifted, indicating the liquid-like property of RAP80 droplets (Figure 2J).

Figure 2.

RAP80 forms condensate in vitro. (A) GST-RAP80-mEGFP solution was muddied in a temperature-dependent manner, whereas the mEGFP solution remained clear. (B) Region within the GST-RAP80-mEGFP droplets was photobleached, and fluorescence signals were collected under a confocal microscope. Scale bar, 2 μm. (C) The fusion of GST-RAP80-mEGFP droplets in vitro. Scale bar, 2 μm. (D) Crowding solution containing PEG 8000 or Ficoll 400 enhanced RAP80 LLPS in vitro. (E–H) Confocal image of RAP80 in vitro droplet showed that protein concentration, salt, and pH regulated RAP80 LLPS. Scale bar, 2 μm. (I, J) characterization of the morphology of GST-RAP80-mEGFP droplets using AFM in tapping mode (I) or contact mode (J). Scale bar, 50 nm.

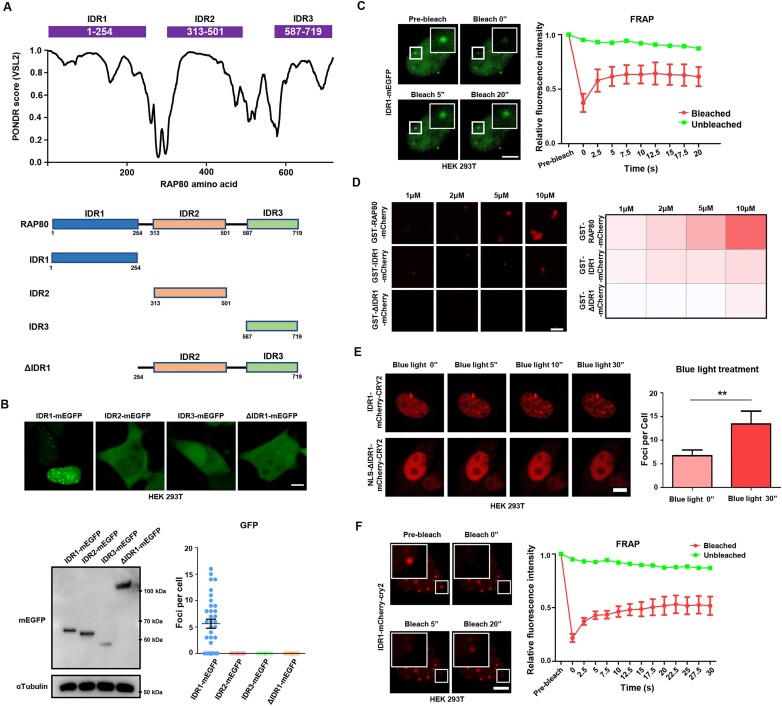

IDR1 is required for RAP80 phase separation

RAP80 contains 3 highly intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) (Figure 3A). Further, we asked whether the IDRs of RAP80 were sufficient for its condensation. IDR1-mEGFP, IDR2-mEGFP, IDR3-mEGFP or ΔIDR1-mEGFP was over-expressed in HEK 293T cells and observed with the confocal microscope. The results showed that only IDR1-mEGFP underwent LLPS in the nucleus (Figure 3B), while ΔIDR1-mEGFP remained soluble. Moreover, IDR1-mEGFP condensates had a rapid FRAP (Figure 3C). In vitro condensates assays were performed on GST-IDR1-mCherry and GST-ΔIDR1-mCherry, which showed that only GST-RAP80 IDR1-mCherry formed condensates (Figure 3D). Later, we used a previously developed optoIDR tool to verify the LLPS potency of IDR1; optoIDR employed a blue light-responsive, self-associating CRY2 protein that largely enhanced the condensate formation of IDR upon blue light stimulation (32). Consistently, blue light facilitated the rapid formation of liquid-like condensates of IDR1-mCherry-CRY2 in cells, while NLS-ΔIDR1-mCherry-CRY2 still maintained a diffused condition. (Figure 3E). Meanwhile, blue light-induced IDR1-mCherry-CRY2 foci also presented a liquid-like character in FRAP assay (Figure 3F). Together, these data indicate that IDR1 is required for RAP80 phase separation.

Figure 3.

IDR1 is required for RAP80 phase separation. (A) IDRs of RAP80 were analyzed using PONDR (http://www.pondr.com/) and the diagram of RAP80 mutants. (B) living cell imaging of IDR1-mEGFP, IDR2-mEGFP, IDR3-mEGFP and ΔIDR1-mEGFP in HEK 293T cells. Twenty-four hours after plasmid transfection, GFP-positive cells were selected using FACS and seeded in plates for living cell imaging and western blotting analysis. The foci number of all cells observed in living cell imaging was counted. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) FRAP assay on IDR1-mEGFP condensate in HEK 293T cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Confocal image of in vitro condensates formation of GST-RAP80-mCherry, GST-IDR1-mCherry, and GST-ΔIDR1-mCherry protein. (E) OptoIDR assay to verify the IDR1-mediated LLPS. n = 6. Scale bar, 5 μm. (F) FRAP assay of blue light-induced IDR1-mCherry-CRY2 droplets. Blue light, 60 s. Scale bar, 5 μm.

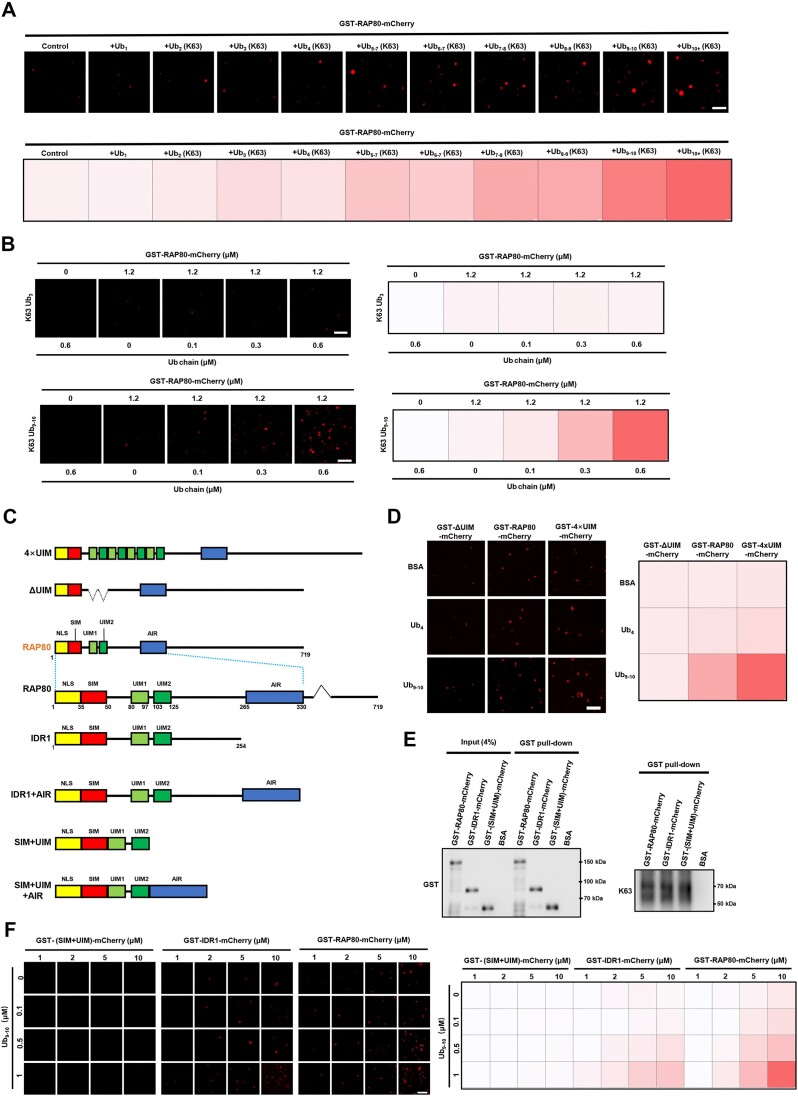

Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains trigger RAP80 phase separation in an UIMs- and IDR1-dependent manner

Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains tag the sites of DNA breaks and function as a signal to recruit a BRCA1-A complex containing BRCA1, BARD1, BRCC3, ABRA1, and RAP80. RAP80 acts as a linker responsible for recruiting the BRCA1-A complex to DNA break sites through its AIR (ABRA1-interacting region) and tandem double UIMs (ubiquitin-interacting motifs), which were reported to recognize Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains (33,34). It is well-known that multivalent interaction is the driving force of LLPS, while the association between UIMs and Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains may increase the multivalent potency of RAP80 protein (35,36). To investigate whether the Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains promoted the condensation of RAP80, the chemically synthesized Lys63-linked ubiquitin chains with a length gradient from mono-ubiquitin (Ub1) to 10-polymer-ubiquitin (Ub10) (Sup Figure 3A) were incubated with purified GST-RAP80-mCherry proteins. The results showed that supplementation of ubiquitin multipolymer (poly-ubiquitin chain) significantly induced the LLPS of RAP80, and the ability to induce RAP80 condensates was positively correlated with the length of the ubiquitin chain (Figure 4A, B). Meanwhile, poly-ubiquitin supplementation had no impact on the in vitro LLPS of RAP80 mutant deleting UIMs (ΔUIM), whereas induced the LLPS of 4×UIMs-containing mutant (4×UIM) stronger than that of wildtype RAP80 (Figure 4C, D; Supplementary Figure 3B). As a control, Lys48-linked poly-ubiquitin chains had no impact on RAP80 condensate formation in vitro (Sup Figure 3C). To elucidate the role of disorder region in poly-ubiquitin-mediated RAP80 LLPS, GST-RAP80-mCherry, GST-IDR1-mCherry, and GST-(SIM+UIM)-mCherry were purified and incubated with Lys63-linked Ub9-10 chains. Although the affinity to Lys63-linked Ub9-10 chain remained similar (Figure 4E), GST-(SIM+UIM)-mCherry did not form condensates in the presence of Lys63-linked Ub9-10in vitro, while GST-RAP80-mCherry and GST-IDR1-mCherry formed Ub9–10-induced condensates (Figure 4F). All these data indicated that Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin triggered RAP80 phase separation in an UIMs- and IDR-dependent manner.

Figure 4.

Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin triggers RAP80 phase separation in a UIMs- and IDR1-dependent manner. (A) 1.2 μM GST-RAP80-mCherry was incubated with 0.6 μM Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin containing the indicated number of units. The fluorescence intensity of droplets was presented as the area × mean intensity (A × M). Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) Long Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin induced RAP80 LLPS stronger than a short one. The fluorescence intensity of droplets was presented as the area × mean intensity (A × M). Scale bar, 2 μm. (C) Diagram of the RAP80 protein-truncating mutants. (D) Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin trigger RAP80 LLPS in a UIM-depended manner. The fluorescence intensity of droplets was presented as the area × mean intensity (A × M). Scale bar 2 μm. (E) examining the affinity of GST-RAP80-mCherry, GST-IDR1-mCherry, and GST-(SIM+UIM)-mCherry to poly-ubiquitin using GST pull-down assay. (F) Long K63 poly-ubiquitin chains triggered RAP80 IDR1 LLPS. The fluorescence intensity of droplets was presented as the area × mean intensity (A × M). Scale bar, 2 μm.

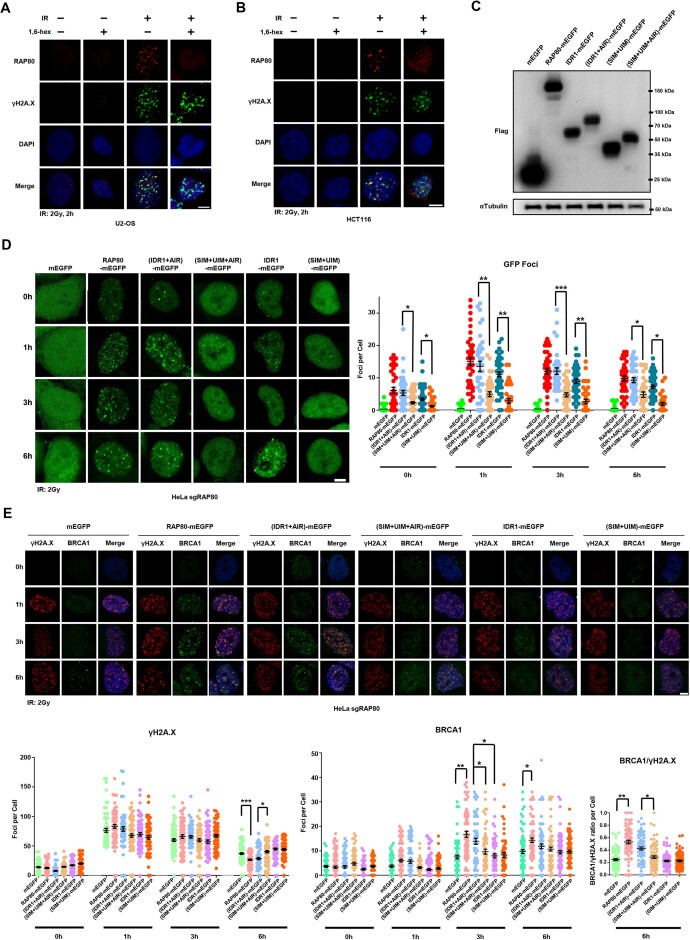

RAP80 LLPS is required for the condensation of RAP80-BRCA1 at DSB

To test if IR-induced endogenous RAP80 foci were LLPS, 1,6-hexanediol was used to treat the irradiated cells. Interestingly, IR-induced RAP80 foci were remarkably diminished by 1,6-hexanediol whereas γH2A.X foci remained unchanged (Figure 5A, B). As the AIR domain of RAP80 was required for its interaction with BRCA1, we constructed (IDR1+AIR)-mEGFP and (SIM+UIM+AIR)-mEGFP mutants for functional assay. Further, RAP80-mEGFP, IDR1-mEGFP, (SIM+UIM)-mEGFP, (IDR1+AIR)-mEGFP, (SIM+UIM+AIR)-mEGFP and mEGFP were respectively stably-expressed in HeLa sgRAP80 cells (Figure 5C; Sup Figure 4A) and exposed to IR. RAP80-mEGFP, IDR1-mEGFP, and (IDR1 + AIR)-mEGFP formed a larger number of foci in the nucleus, while (SIM + UIM)-mEGFP and (SIM+UIM+AIR)-mEGFP showed significant lower foci number (Figure 5D). These data revealed that LLPS of RAP80 was required for its condensation at DNA damaged site. Next, we asked if LLPS was essential for the recruitment of BRCA1 to DNA lesions by RAP80, which is crucial for DNA repair. BRCA1 and γH2A.X foci numbers were examined in the Hela sgRAP80 cells, grouped by stable expression of RAP80-mEGFP, IDR1-mEGFP, (SIM+UIM)-mEGFP, (IDR1+AIR)-mEGFP, (SIM+UIM+AIR)-mEGFP, and mEGFP. Only cells expressing RAP80-WT-mEGFP and RAP80-(IDR1+AIR)-mEGFP showed prominent BRCA1 IRIF (Figure 5E), which was consistent with their LLPS capacity. On the other hand, although IDR1 could form condensates at DNA damage lesions (Figure 5D), it was insufficient for BRCA1 IRIF formation, while in IDR1 + AIR expressed cells, BRCA1 IRIF was similar to that in RAP80-WT expressing cells (Figure 5E), indicating that both LLPS and AIR domain were critical for RAP80-mediated recruitment of BRCA1.

Figure 5.

RAP80 LLPS is required for the condensation of RAP80 and BRCA1 at DSB. (A, B) 10% 1,6-hexanediol disrupted IR-induced RAP80 puncta in U2-OS and HCT116 cells. Cells were irradiated with 2 Gy X-ray, recovered for 2 h, and treated with 10% 1,6-hexanediol for 50 s before IF analysis. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) the expression of different mutants in RAP80-KO HeLa cells was analyzed by western blotting. RAP80-KO HeLa cells were infected with lentivirus to construct mutants stably-expressed cell lines. (D) The foci number of stably-expressing different RAP80 mutants HeLa sgRAP80 cells after IR (2 Gy). Scale bar, 5 μm; n ≥ 30 cells. (E) RAP80 LLPS promoted the recruitment of BRCA1 to DSB and accelerated the clearance of IR-induced γH2A.X. The ratio of BRCA1/γH2A.X foci number for each cell was calculated at 6 h after IR. RAP80-KO HeLa cells were infected with lentivirus to construct mutants stably-expressed cell lines. Scale bar, 5 μm; n ≥ 50 cells.

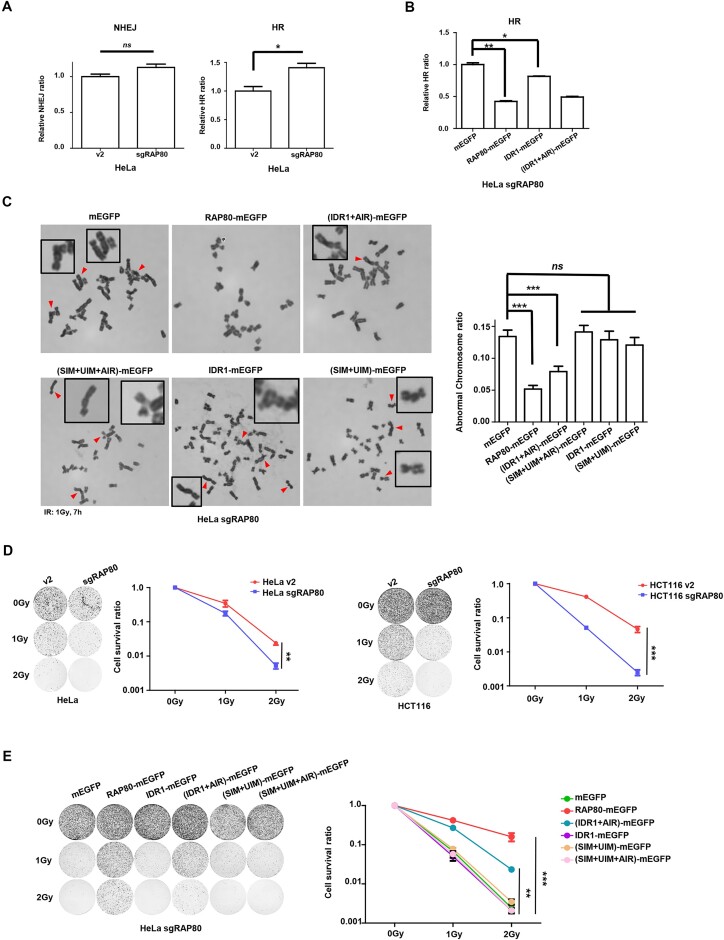

RAP80 condensates promote DNA damage repair and radio-resistance

Consistent with its role in BRCA1 recruitment, IR-induced γH2A.X foci in RAP80-WT and IDR1+AIR re-expressing cells were eliminated faster than that of control cells, indicating that RAP80 LLPS was required for sufficient DNA damage repair (Figure 5E). It has been reported that RAP80 suppresses hyper-HR and hyper-end processing to promote genome stability (37,38). In agreement with these reports, our data showed that RAP80 depletion resulted in hyper-HR but having no impact on NHEJ (Figure 6A). Furthermore, restoring RAP80-WT and IDR1+AIR in RAP80-KO cells attenuated hyper-HR and IR-induced chromosome aberrant (Figure 6B, C; Supplementary Figure 4B, C), indicating that LLPS was essential for RAP80 function. Additionally, colony formation assay was used to analyze the radiosensitivity of tumor cells. In agreement with the previous report (37), RAP80 depletion sensitized tumor cells to IR (Figure 6D). Most importantly, re-expression of RAP80-WT or IDR1+AIR in HeLa sgRAP80 cells largely restored radio-resistance (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

RAP80 LLPS regulates HR, genomic stability, and radio-sensitivity. (A, B) DSB repair reporter assay in RAP80-WT and different RAP80 mutants stably-expressing HeLa sgRAP80 cells. The population of GFP+ and mCherry+ cells in BFP+ cells was analyzed. Data from three biological replicates were presented. (C) Different RAP80 mutants stably-expressing HeLa sgRAP80 cells were treated with IR (1 Gy), and aberrant chromosomes were counted in at least 30 cells of metaphases. (D) Colony formation assay showed that RAP80 knockout sensitized HeLa and HCT116 cells to radiation. (E) Examining the radiosensitivity of HeLa sgRAP80 cells stably-expressing indicated RAP80 mutants by colony formation assay.

Taken together, our results suggested that after DNA damage occurs, RAP80 underwent LLPS at DNA lesion, which was required for RAP80 accumulation and sufficient BRCA1 recruitment, thereby promoting DNA repair and radio-resistance.

DISCUSSION

Here, we found that although RAP80 and BRCA1 are reported to form the BRCA1-A complex (21,30), and the recruitment of BRCA1 to DNA lesion was RAP80 dependent (Figure 1A), their temporal dynamics at the DNA damage site are different. Furthermore, the IR-induced BRCA1 foci were more likely to be attached to RAP80 foci than being perfectly colocalized (Supplementary Figure 5A). Consistently, a previous study from Livingstone's group showed that RAP80 depletion not only reduced the number of BRCA1 IRIF but also made the BRCA1 IRIF smaller and less condensed (37). These observations indicate a novel mechanism underlying RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment apart from their physical interaction. Recently, we and others have reported that LLPS plays important roles in DSB repair, including DSB sensing, non-homologous recombination (NHEJ) repair, and HR repair (12,39,40). Further, we characterized that RAP80 underwent LLPS and formed liquid-like condensates at the DSB site, which was required for the recruitment of BRCA1. Significantly, by disrupting RAP80 condensates using 1,6-hexanediol after the foci formation of BRCA1 and RAP80, we observed that BRCA1 foci number was moderately reduced (Sup Figure 5B), suggesting that RAP80 condensate may also contribute to the maintenance of BRCA1 at DNA damage site. Reported studies have given evidence that BRCA1 is responsible for recruiting other BRCA1-dominant complex components, including CtIP and BACH1 (41–44). Moreover, phase-separated condensates might recruit or exclude some molecules with high specificity (45). We proposed that RAP80 condensates might recruit the BRCA1-A complex to the DSB site, and subsequentially disassemble the BRCA1-A complex to favor the recruitment and assembly of other BRCA1 complex components (Graphical Abstract).

Ubiquitination is the post-translational modification process by which ubiquitin is attached via an isopeptide bond to lysine residues on a protein (45). Ubiquitin could be linked to each other through all of its seven resides of lysine (Lys6, Lys11, Lys27, Lys29, Lys33, Lys48 and Lys63) (46). As the most abundant ubiquitination type, Lys48-linked ubiquitination is usually related to the degradation of substrates through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (47,48). Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitination, however, regulates the enzymatic activity, interaction, or intracellular transportation of substrates, participating in diverse biological processes, including DNA damage repair (49). Ubiquitination triggers and amplifies many biological signals in DNA damage response. For example, chromatin ubiquitylation by the RNF8 and RNF168 has a central role in recruiting key DNA repair factors to DSB sites. At DSB sites, RNF8 promotes histone ubiquitylation to trigger E3 ligase RNF168 recruitment (50–52).

Ubiquitination also plays a role in the regulation of LLPS. Highly disordered proteins with ubiquitin-binding motifs, such as hHR23B and p62, were found undergoing LLPS by binding to the poly-ubiquitin chain (53–55). RAP80 contains two UIM (80–97 and 103–125aa) and intrinsically disordered region 1 (1–254aa), both of which are important for its condensation (Figure 3B-E and Figure 4D-F). Different types of poly-ubiquitination chains significantly varied in the binding affinities to UIM-containing protein, resulting in different potentials in inducing LLPS. For example, Lys11- and Lys48-linked poly-ubiquitin generally inhibits UBQLN2 LLPS, whereas Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin significantly enhances LLPS (56,57). In agreement with these findings, we found that Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin induced the condensation of RAP80 whereas Lys48-linked poly-ubiquitin had no impact (Figure 4A, Supplementary Figure 3C). The underlying mechanism may be ascribed to the higher affinity of RAP80 to Lys63-linked poly-ubiquitin than that of Lys48-linked (58). We also found that RAP80 LLPS was positively correlated with the valence of poly-ubiquitin, Lys63-linked Ub(2–4) hardly induced RAP80 condensation while Lys63-linked Ub(>4)strongly triggered RAP80 LLPS (Figure 4A, B), which is consistent with the stimulation of LLPS by multivalent interaction. In addition to H2A.X, other proteins, such as Histone H1, L3MBTL1, and L3MBTL2 (59–61), are also found to be Lys63-linked ubiquitinated, which may also be bound with RAP80 and served as the trigger of RAP80 LLPS.

In addition to IDR and the interaction with poly-ubiquitin, other factors may also be involved in the induction of RAP80 condensation. When comparing IR-induced foci numbers, we found that IDR1-mEGFP foci numbers were less than full-length RAP80-mEGFP (Figure 5D). Furthermore, in vitro droplets assay showed that GST-IDR1-mCherry formed fewer condensates than GST-RAP80-mCherry, indicating that apart from IDR1 and UIM, RAP80 contains other regulatory motifs. SUMOylation at DSB site is responsible for the recruitment of DNA repair factors. Interestingly, RAP80 contains a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM), which may bind to the SUMOylated protein at DSB and provide additional multivalent interactions to trigger RAP80 LLPS. Furthermore, consistent with the cell cycle dependency of HR repair, IR-induced RAP80 condensation mainly occurred in the S/G2 phase (Supplementary Figure 5C). This cell cycle dependency may be ascribed to that RAP80 expression was varied at different cell cycle phases. Several studies have shown that RAP80 was highly expressed in S/G2 phase, but was reduced expressed in M to G1 phase (62,63). The underlying mechanism remains to be further disclosed.

Our results suggested that all of the IDR1, UIM, and AIR motifs are essential for RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment. Firstly, although the IR-induced foci number of IDR1-mEGFP and (IDR1+AIR)-mEGFP was similar, (IDR1+AIR)-mEGFP-expressing cells showed more BRCA1 foci (Figure 5E), which was consistent with the previous report that deletion of AIR reduced BRCA1 recruitment (19). Secondly, after IR, (IDR+AIR)-mEGFP re-expressing HeLa sgRAP80 cells showed significantly higher BRCA1 foci number than that of (SIM+UIM+AIR)-mEGFP, indicating that RAP80 LLPS was mediated by IDR1 and poly-ubiquitin, and was required for BRCA1 recruitment.

The dysregulation of DNA damage repair is one of the driving forces for tumorigenesis and tumor radio-resistance. Consistent with the role of RAP80 in DSB repair, it had been reported as an independent prognosis biomarker for many types of cancers, including ovarian cancer (64), non-small cell lung cancer(65), and breast cancer (66). Furthermore, our colony formation assay showed that the LLPS potency of RAP80 mutants was negatively correlated with cell radiosensitivity, which may be ascribed to the ability to recruit BRCA1 and DSB repair. Consistent with its roles in DSB repair, the analysis of clinical samples showed that for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who receive neoadjuvant radiotherapy, RAP80 protein level was negatively correlated to their prognosis (Sup Figure 6A), while for patients with radiation enteritis (RE), RAP80 protein level in RE tissues was lower than normal intestinal tissues (Sup Figure 6B), suggesting that RAP80 plays an important role in the regulation of radiosensitivity.

Taken together, our study disclosed a novel mechanism underlying RAP80-mediated BRCA1 recruitment, which was mediated by LLPS to promote irradiation-induced DNA damage repair. Significantly, RAP80 LLPS-based phenotype might be the explanation for tumor radio-resistance, hence that RAP80 LLPS might be a promising target for cancer treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Figure 3A was created using PONDR (http://www.pondr.com/). We thank the Cytogenetics Laboratory of Obstetrical Department in the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University for their technical support in karyotyping. We gratefully thank the moral support from Dr Lei Wang, the former vice president of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, who had dedicated his lifetime to colorectal cancer and radiation enteritis. Though Dr Lei Wang has been away from us for 4 years, his noteworthy contribution to human health as well as his extraordinary benevolence, dauntlessness and selflessness, as recorded in our previous Lancet Digital Health paper, is still engraved on our mind. Dear Dr Wang, we miss you, very much.

Contributor Information

Caolitao Qin, Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Yun-Long Wang, Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Academy of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Jin-Ying Zhou, Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Academy of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China.

Jie Shi, Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Wan-Wen Zhao, Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Ya-Xi Zhu, GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; Department of Pathology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Shao-Mei Bai, GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; Department of Pathology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Li-Li Feng, Department of Radiation Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Shu-Ying Bie, Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; Department of Pathology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Bing Zeng, GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; Department of Gastroenterology, Hernia and Abdominal Wall Surgery, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Jian Zheng, Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Guang-Dong Zeng, Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Wei-Xing Feng, Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Xiang-Bo Wan, Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Academy of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Department of Radiation Oncology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

Xin-Juan Fan, Henan Provincial Key Laboratory of Radiation Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; Academy of Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan 450052, P.R. China; GuangDong Provincial Key Laboratory of Colorectal and Pelvic Floor Diseases, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China; Department of Pathology, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510655, P.R. China.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All primary data are available from the authors upon request.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Key R&D Program of China [2022YFA1105300, 2022YFC2503700]; National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars [82225040]; National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars [82122057]; Natural Science Foundation of China [82103770, 82171163]; Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars [2021B1515020022]; Guangdong Science and Technology Project [2020A1515010314, 2022A1515012363]; Beijing Bethune Charitable Foundation [flzh202102]; Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [22qntd3602]. Funding for open access charge: National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars [82122057].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mehta S., Zhang J.. Liquid-liquid phase separation drives cellular function and dysfunction in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2022; 22:239–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lopez-Palacios T.P., Andersen J.L.. Kinase regulation by liquid-liquid phase separation. Trends. Cell Biol. 2023; 33:649–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang B., Zhang L., Dai T., Qin Z., Lu H., Zhang L., Zhou F.. Liquid–liquid phase separation in human health and diseases. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2021; 6:290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darling A.L., Liu Y., Oldfield C.J., Uversky V.N.. Intrinsically disordered proteome of Human membrane-less organelles. Proteomics. 2018; 18:e1700193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Uversky V.N., Gillespie J.R., Fink A.L. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions?. Proteins. 2000; 41:415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muiznieks L.D., Sharpe S., Pomes R., Keeley F.W. Role of liquid-liquid phase separation in assembly of elastin and other extracellular matrix proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2018; 430:4741–4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mittag T., Parker R.. Multiple modes of protein-protein interactions promote RNP granule assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 2018; 430:4636–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim H.J., Kim N.C., Wang Y.D., Scarborough E.A., Moore J., Diaz Z., MacLea K.S., Freibaum B., Li S., Molliex A.et al.. Mutations in prion-like domains in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 cause multisystem proteinopathy and ALS. Nature. 2013; 495:467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stanic M., Mekhail K.. Integration of DNA damage responses with dynamic spatial genome organization. Trends. Genet. 2022; 38:290–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fijen C., Rothenberg E.. The evolving complexity of DNA damage foci: RNA, condensates and chromatin in DNA double-strand break repair. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2021; 105:103170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mirza-Aghazadeh-Attari M., Mohammadzadeh A., Yousefi B., Mihanfar A., Karimian A., Majidinia M.. 53BP1: a key player of DNA damage response with critical functions in cancer. DNA Repair (Amst.). 2019; 73:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y.L., Zhao W.W., Bai S.M., Feng L.L., Bie S.Y., Gong L., Wang F., Wei M.B., Feng W.X., Pang X.L.et al.. MRNIP condensates promote DNA double-strand break sensing and end resection. Nat. Commun. 2022; 13:2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pessina F., Giavazzi F., Yin Y., Gioia U., Vitelli V., Galbiati A., Barozzi S., Garre M., Oldani A., Flaus A.et al.. Functional transcription promoters at DNA double-strand breaks mediate RNA-driven phase separation of damage-response factors. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019; 21:1286–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kilic S., Lezaja A., Gatti M., Bianco E., Michelena J., Imhof R., Altmeyer M.. Phase separation of 53BP1 determines liquid-like behavior of DNA repair compartments. EMBO J. 2019; 38:e101379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cai D., Liu Z., Lippincott-Schwartz J.. Biomolecular condensates and their links to cancer progression. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2021; 46:535–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tarsounas M., Sung P.. The antitumorigenic roles of BRCA1-BARD1 in DNA repair and replication. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Bio. 2020; 21:284–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu J., Liu C., Chen J., Yu X.. RAP80 protein is important for genomic stability and is required for stabilizing BRCA1-A complex at DNA damage sites in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:22919–22926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jiang Q., Foglizzo M., Morozov Y.I., Yang X., Datta A., Tian L., Thada V., Li W., Zeqiraj E., Greenberg R.A.. Autologous K63 deubiquitylation within the BRCA1-A complex licenses DNA damage recognition. J. Cell Biol. 2022; 221:e202111050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rabl J., Bunker R.D., Schenk A.D., Cavadini S., Gill M.E., Abdulrahman W., Andres-Pons A., Luijsterburg M.S., Ibrahim A., Branigan E.et al.. Structural basis of BRCC36 function in DNA repair and immune regulation. Mol. Cell. 2019; 75:483–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim H., Chen J., Yu X.. Ubiquitin-binding Protein RAP80 Mediates BRCA1-dependent DNA Damage Response. Science. 2007; 316:1202–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yan J., Kim Y.S., Yang X.P., Li L.P., Liao G., Xia F., Jetten A.M.. The ubiquitin-interacting motif containing protein RAP80 interacts with BRCA1 and functions in DNA damage repair response. Cancer. Res. 2007; 67:6647–6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nikkila J., Coleman K.A., Morrissey D., Pylkas K., Erkko H., Messick T.E., Karppinen S.M., Amelina A., Winqvist R., Greenberg R.A.. Familial breast cancer screening reveals an alteration in the RAP80 UIM domain that impairs DNA damage response function. Oncogene. 2009; 28:1843–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu X., Paul A., Wang B.. Rap80 protein recruitment to DNA double-strand breaks requires binding to both small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) and ubiquitin conjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:25510–25519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guzzo C.M., Berndsen C.E., Zhu J., Gupta V., Datta A., Greenberg R.A., Wolberger C., Matunis M.J.. RNF4-Dependent hybrid SUMO-ubiquitin chains are signals for RAP80 and thereby mediate the recruitment of BRCA1 to sites of DNA damage. Sci. Signal. 2012; 5:ra88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mok M.T., Henderson B.R.. The in vivo dynamic organization of BRCA1-A complex proteins at DNA damage-induced nuclear foci. Traffic. 2012; 13:800–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Duster R., Kaltheuner I.H., Schmitz M., Geyer M.. 1,6-Hexanediol, commonly used to dissolve liquid-liquid phase separated condensates, directly impairs kinase and phosphatase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2021; 296:100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Krypotou E., Townsend G.E., Gao X., Tachiyama S., Liu J., Pokorzynski N.D., Goodman A.L., Groisman E.A.. Bacteria require phase separation for fitness in the mammalian gut. Science. 2023; 379:1149–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang Y., Lei G., Lin T., Zhou N., Wu J., Wang Z., Fan Y., Sheng H., Mao R.. 1,6-Hexanediol regulates angiogenesis via suppression of cyclin A1-mediated endothelial function. BMC Biol. 2023; 21:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arnoult N., Correia A., Ma J., Merlo A., Garcia-Gomez S., Maric M., Tognetti M., Benner C.W., Boulton S.J., Saghatelian A.et al.. Regulation of DNA repair pathway choice in S and G2 phases by the NHEJ inhibitor CYREN. Nature. 2017; 549:548–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sobhian B., Shao G., Lilli D.R., Culhane A.C., Moreau L.A., Xia B., Livingston D.M., Greenberg R.A.. RAP80 targets BRCA1 to specific ubiquitin structures at DNA damage sites. Science. 2007; 316:1198–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ulianov S.V., Velichko A.K., Magnitov M.D., Luzhin A.V., Golov A.K., Ovsyannikova N., Kireev I.I., Gavrikov A.S., Mishin A.S., Garaev A.K.et al.. Suppression of liquid-liquid phase separation by 1,6-hexanediol partially compromises the 3D genome organization in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:10524–10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Valon L., Marin-Llaurado A., Wyatt T., Charras G., Trepat X.. Optogenetic control of cellular forces and mechanotransduction. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8:14396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walters K.J., Chen X.. Measuring ubiquitin chain linkage: rap80 uses a molecular ruler mechanism for ubiquitin linkage specificity. EMBO J. 2009; 28:2307–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang B., Elledge S.J.. Ubc13/Rnf8 ubiquitin ligases control foci formation of the Rap80/Abraxas/Brca1/Brcc36 complex in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007; 104:20759–20763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song X., Yang F., Yang T., Wang Y., Ding M., Li L., Xu P., Liu S., Dai M., Chi C.et al.. Phase separation of EB1 guides microtubule plus-end dynamics. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2022; 25:79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shen C., Li R., Negro R., Cheng J., Vora S.M., Fu T.M., Wang A., He K., Andreeva L., Gao P.et al.. Phase separation drives RNA virus-induced activation of the NLRP6 inflammasome. Cell. 2021; 184:5759–5774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu Y., Scully R., Sobhian B., Xie A., Shestakova E., Livingston D.M.. RAP80-directed tuning of BRCA1 homologous recombination function at ionizing radiation-induced nuclear foci. Gene. Dev. 2011; 25:685–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vohhodina J., Toomire K.J., Petit S.A., Micevic G., Kumari G., Botchkarev V.J., Li Z., Livingston D.M., Hu Y.. RAP80 and BRCA1 parsylation protect chromosome integrity by preventing retention of BRCA1-B/C complexes in DNA repair foci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020; 117:2084–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Y.L., Zhao W.W., Bai S.M., Ma Y., Yin X.K., Feng L.L., Zeng G.D., Wang F., Feng W.X., Zheng J.et al.. DNA damage-induced paraspeckle formation enhances DNA repair and tumor radioresistance by recruiting ribosomal protein P0. Cell Death. Dis. 2022; 13:709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fan X.J., Wang Y.L., Zhao W.W., Bai S.M., Ma Y., Yin X.K., Feng L.L., Feng W.X., Wang Y.N., Liu Q.et al.. NONO phase separation enhances DNA damage repair by accelerating nuclear EGFR-induced DNA-PK activation. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021; 11:2838–2852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cantor S.B., Bell D.W., Ganesan S., Kass E.M., Drapkin R., Grossman S., Wahrer D.C., Sgroi D.C., Lane W.S., Haber D.A.et al.. BACH1, a novel helicase-like protein, interacts directly with BRCA1 and contributes to Its DNA repair function. Cell. 2001; 105:149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu X., Fu S., Lai M., Baer R., Chen J.. BRCA1 ubiquitinates its phosphorylation-dependent binding partner CtIP. Gene. Dev. 2006; 20:1721–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yu X., Wu L.C., Bowcock A.M., Aronheim A., Baer R.. The C-terminal (BRCT) domains of BRCA1 interact in vivo with CtIP, a protein implicated in the CtBP pathway of transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 1998; 273:25388–25392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Greenberg R.A., Sobhian B., Pathania S., Cantor S.B., Nakatani Y., Livingston D.M.. Multifactorial contributions to an acute DNA damage response by BRCA1/BARD1-containing complexes. Gene. Dev. 2006; 20:34–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lu Y., Wu T., Gutman O., Lu H., Zhou Q., Henis Y.I., Luo K.. Phase separation of TAZ compartmentalizes the transcription machinery to promote gene expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020; 22:453–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kwon Y.T., Ciechanover A.. The ubiquitin code in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017; 42:873–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Depraetere V. Getting activated with poly-ubiquitination. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001; 3:E181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hjerpe R., Rodriguez M.S.. Alternative UPS drug targets upstream the 26S proteasome. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. 2008; 40:1126–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Swatek K.N., Komander D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 2016; 26:399–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Panier S., Ichijima Y., Fradet-Turcotte A., Leung C.C., Kaustov L., Arrowsmith C.H., Durocher D. Tandem protein interaction modules organize the ubiquitin-dependent response to DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. 2012; 47:383–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stewart G.S., Panier S., Townsend K., Al-Hakim A.K., Kolas N.K., Miller E.S., Nakada S., Ylanko J., Olivarius S., Mendez M.et al.. The RIDDLE syndrome protein mediates a ubiquitin-dependent signaling cascade at sites of DNA damage. Cell. 2009; 136:420–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Doil C., Mailand N., Bekker-Jensen S., Menard P., Larsen D.H., Pepperkok R., Ellenberg J., Panier S., Durocher D., Bartek J.et al.. RNF168 binds and amplifies ubiquitin conjugates on damaged chromosomes to allow accumulation of repair proteins. Cell. 2009; 136:435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yasuda S., Tsuchiya H., Kaiho A., Guo Q., Ikeuchi K., Endo A., Arai N., Ohtake F., Murata S., Inada T.et al.. Stress- and ubiquitylation-dependent phase separation of the proteasome. Nature. 2020; 578:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dao T.P., Castaneda C.A.. Ubiquitin-modulated phase separation of shuttle proteins: does condensate formation promote protein degradation?. Bioessays. 2020; 42:e2000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sun D., Wu R., Zheng J., Li P., Yu L.. Polyubiquitin chain-induced p62 phase separation drives autophagic cargo segregation. Cell Res. 2018; 28:405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dao T.P., Yang Y., Presti M.F., Cosgrove M.S., Hopkins J.B., Ma W., Loh S.N., Castaneda C.A.. Mechanistic insights into enhancement or inhibition of phase separation by different polyubiquitin chains. EMBO Rep. 2022; 23:e55056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dao T.P., Kolaitis R.M., Kim H.J., O’Donovan K., Martyniak B., Colicino E., Hehnly H., Taylor J.P., Castaneda C.A.. Ubiquitin modulates liquid-liquid phase separation of UBQLN2 via disruption of multivalent interactions. Mol. Cell. 2018; 69:965–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sims J.J., Cohen R.E.. Linkage-specific avidity defines the lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin-binding preference of rap80. Mol. Cell. 2009; 33:775–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thorslund T., Ripplinger A., Hoffmann S., Wild T., Uckelmann M., Villumsen B., Narita T., Sixma T.K., Choudhary C., Bekker-Jensen S.et al.. Histone H1 couples initiation and amplification of ubiquitin signalling after DNA damage. Nature. 2015; 527:389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kato K., Nakajima K., Ui A., Muto-Terao Y., Ogiwara H., Nakada S.. Fine-tuning of DNA damage-dependent ubiquitination by OTUB2 supports the DNA repair pathway choice. Mol. Cell. 2014; 53:617–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nowsheen S., Aziz K., Aziz A., Deng M., Qin B., Luo K., Jeganathan K.B., Zhang H., Liu T., Yu J.et al.. L3MBTL2 orchestrates ubiquitin signalling by dictating the sequential recruitment of RNF8 and RNF168 after DNA damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018; 20:455–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cho H.J., Oh Y.J., Han S.H., Chung H.J., Kim C.H., Lee N.S., Kim W.J., Choi J.M., Kim H.. Cdk1 protein-mediated phosphorylation of receptor-associated protein 80 (RAP80) serine 677 modulates DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint and cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2013; 288:3768–3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cho H.J., Lee E.H., Han S.H., Chung H.J., Jeong J.H., Kwon J., Kim H.. Degradation of human RAP80 is cell cycle regulated by Cdc20 and Cdh1 ubiquitin ligases. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012; 10:615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rebbeck T.R., Mitra N., Domchek S.M., Wan F., Friebel T.M., Tran T.V., Singer C.F., Tea M.K., Blum J.L., Tung N.et al.. Modification of BRCA1-associated breast and ovarian cancer risk by BRCA1-interacting genes. Cancer Res. 2011; 71:5792–5805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sun X., Cui F., Yin H., Wu D., Wang N., Yuan M., Fei Y., Wang Q.. Association between EGFR mutation and expression of BRCA1 and RAP80 in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018; 16:2201–2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nikkilä J., Coleman K.A., Morrissey D., Pylkäs K., Erkko H., Messick T.E., Karppinen S., Amelina A., Winqvist R., Greenberg R.A.. Familial breast cancer screening reveals an alteration in the RAP80 UIM domain that impairs DNA damage response function. Oncogene. 2009; 28:1843–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All primary data are available from the authors upon request.