Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this valuation study was to produce a value set to support the use of EQ-5D-5L data in decision making in Slovenia.

Methods

The study design followed the published EuroQol research protocol, and a quota sample was defined according to age, sex, and region. Overall, 1012 adult respondents completed 10 time trade-off and seven discrete choice experiment tasks in face-to-face interviews. The Tobit model was used to analyse the composite time trade-off (cTTO) data in order to generate values for the 3125 EQ-5D-5L health states.

Results

The data showed logical consistency, with more severe states being given lower values. The greatest disutility was shown in the pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions. In the EQ-5D-5L value set, the values range from −1.09 to 1. With the exception of UA5 (unable to perform usual activities), all other levels on all health dimensions were statistically different from 0 and from each other. Compared with the existing EQ-5D-3L value set, there is a slightly lower share of ‘worse than dead’ states (32.1% compared with 33.7%) and the minimum value is lower.

Conclusions

Results have important implications for users of the EQ-5D-5L in Slovenia and regions. It is a robust and up-to-date value set and should be the preferred value set used in adults in Slovenia and in neighbouring countries without their own value set.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| This paper presents the EQ-5D-5L value set for Slovenia, which was obtained following the EuroQol Group valuation protocol for EQ-5D-5L. The values were calculated from composite time trade-off (cTTO) data on the preferences of 1012 adults from Slovenia towards EQ-5D-5L health states, using the Tobit model. |

| The use of EQ-5D-5L in Slovenia is on the rise; health care providers are obliged by law to use EQ-5D-5L as a patient-reported outcome measure in the endoprosthetics registry. It is also one of the compulsory outcome indicators defined in the 2023 National Quality and Safety Strategy draft. The presented value set will allow further analysis and will support outcome-based decision making in Slovenia. |

Introduction

Health technology assessment (HTA) has been increasingly used in healthcare decision making on resource allocation in many countries. Health technologies in Slovenia are assessed by various bodies that publish guidelines and recommendations on conducting economic evaluations of health interventions [1, 2]. The most common way to express the benefits of health intervention is quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The QALY is a measure that combines a treatment’s impact on a patient’s length of life and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) into a single outcome. To calculate QALYs, we need to express HRQOL in the form of a single value, known as health utility, which is scored on a scale that assigns a value of 1 to a state equivalent to full health and 0 to a state equivalent to being dead [3]. The EQ-5D, a preference-based quality-of-life measure, is one of the most used measures for the valuation of health [4, 5].

The EQ-5D instrument was developed by the EuroQol Organization. Currently, the following EQ-5D instruments are available: three-level instrument (EQ-5D-3L), five-level instrument (EQ-5D-5L), and youth version (EQ-5D-Y). Each of these instruments can be adapted for the mode of administration (e.g. self-complete, proxy, or interviewer administration) or for use on a different platform (paper or digital). The EQ-5D five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) was developed by the EuroQol Organization in 2009 [6] to avoid the methodological limitations [7] of the three-level version. EQ-5D-5L is currently available in more than 150 languages and in various modes of administration [8]. The descriptive system of the EQ-5D questionnaire consists of five dimensions: mobility (MO), self-care (SC), usual activities (UA), pain/discomfort (PD), and anxiety/depression (AD). In the original 3L version, each dimension had three levels of problems: no, some, or severe [9]; however, in the 5L version, these levels are no, slight, moderate, severe, or unable to/extreme problems [4]. The EQ-5D-5L has shown strong psychometric properties [7]. A systematic review [10] that included 24 studies found that Shannon’s indices were always higher for 5L than for 3L, and all but three studies reported lower ceiling effects (‘11111’) for 5L than for 3L. There was mixed and insufficient evidence on responsiveness and test–retest reliability, although results on index values showed better performance for 5L on test–retest reliability. Other studies also showed higher discriminatory power and more even distribution, with improved informativity and reduced ceiling effect for EQ-5D-5L than EQ-5D-3L [11].

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire has been translated into the Slovenian language [10]. As it had no corresponding values for each of the 3125 health states, and its use was therefore hindered, an interim EQ-5D-5L value set for Slovenia using the crosswalk methodology developed by the EuroQol was developed in 2020 [12]. The crosswalk value set is of course not based on preferences directly elicited from representative general population samples, which was the aim of this study. Currently, there are 37 published EQ-5D-5L value sets worldwide, three of which are in Central and Eastern Europe: Romania [13], Poland [14], and Hungary [15].

As Slovenia has had the official translation of EQ-5D instruments as well as value sets and population norms available, EQ-5D has been widely used in studies measuring HRQoL in various patient populations [16, 17]. EQ-5D-5L is also one of the recommended patient-reported outcome measures in the new National Quality and Safety Strategy draft 2023–2031 [18] and was, by law, included in the Registry of Endoprosthetics in 2021 [19]. For all these reasons, we can expect that the new value set will be widely used.

The aim of this study was to develop the EQ-5D-5L value set for Slovenia by eliciting general adult population preferences. The elicited preferences will replace the crosswalk preferences for the EQ-5D-5L-defined health states currently used in the assessment of healthcare interventions.

Methods

The EuroQol Group’s valuation protocol was strictly followed throughout the study [20].

Sampling

For the survey, a representative sample of 1012 Slovenian adults aged 18+ years was obtained. The non-probability quota samples were formed across 12 statistical regions in Slovenia, according to age groups (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, ≥ 65 years) and sex (female/male). Inclusion criteria for the study were age ≥ 18 years and agreement to participation via an online informed consent form. Participation in the study was voluntary, however participants received compensation in the form of a €10 gift card. Respondents were recruited via the interviewers, who mostly covered their respective areas of residence. A mixed recruitment strategy was used as the respondents were recruited through personal contact as well as in public spaces.

Interviews

The interviewer team consisted of 11 university students studying economics, social sciences, or medicine, as well as one principal investigator. All interviewers underwent one full day of training in accordance with the programme developed by the EuroQol Group. Each interviewer conducted at least 10 training interviews or more in case the results had still not reached a sufficient quality level. The interviews started in March 2022 and continued until November 2022 when the quotas were full. The interviewers covered at least one region but some covered more regions, depending on the number of respondents in each region. Face-to face interviews were conducted that used composite time trade-off (cTTO) and discrete choice experiment (DCE) methods. The minimum number of interviews performed per interviewer was 35 and the maximum was 131.

The latest available version of the EuroQol Valuation Technique (EQ-VT) was used for the study (version 2.1). The study received approval from the Commission of the Republic of Slovenia for Medical Ethics (no. 0120-381/2021/6, dated 3 November 2021) prior to data collection. The target sample size was 1000 respondents, as defined in the EuroQol Group’s valuation protocol [20].

The interview consisted of a welcome and an explanation of the purpose of the interview, self-reported health using the 5L descriptive system and EQ-VAS task, cTTO valuation tasks (wheelchair example, three practice states, 10 real tasks, debriefing questions, feedback module), DCE valuation tasks (seven tasks, debriefing questions), demographic questions, comment box, and an additional DCE survey trying to determine the value of QALYs in Slovenia.

Research Design

Overall, 86 of the 3125 EQ-5D-5L health states were included in two different preference elicitation tasks according to the EQ-VT design [21]: (1) composite time trade-off (cTTO), and (2) DCE without duration. For the cTTO tasks, the health states were grouped into 10 blocks consisting of 10 health states each. Some states were present in multiple blocks, with each mild state (21111, 12111, 11211, 11121, 11112) repeated in two blocks and the pits state (55555) repeated in all 10 blocks. The remaining 80 states were generated using Fedorov’s exchange algorithm. For the DCE tasks, we used 196 pairs of EQ-5D-5L health states, divided into 28 blocks of seven pairs. The assignment of the cTTO and DCE blocks to each of the respondents was random.

The aim of the cTTO is to find a point at which the respondent is indifferent between a longer period of impaired health and a shorter period of full health. The cTTO approach incorporates the lead time in cases when the respondents consider a certain health state as worse than dead [22]. The whole cTTO approach is explained to the respondent at the beginning using the ‘wheelchair example’, where the worse than dead and better than dead health states are valued. The task is then practiced on three practice states (one good health state, one bad health state, and one hard-to-imagine health state). The cTTO values range from −1 (trading whole lead time) to 1 (trading no years in full health). At the end of the cTTO task, all health states are ranked from the best to the worst. If the respondent is not happy with the ranking, the responses are flagged and removed from the valuation tasks.

DCE tasks without duration consist of seven pairs of EQ-5D-5L health states, where the respondent is required to choose the better one.

Quality Control

Throughout the data collection period, interviewer performance was monitored as part of the quality-control procedure developed by the EuroQol Group [23]. The EuroQol Group appointed two supervisors of quality, with whom regular meetings were held during the entire period of data collection. The quality criteria were:

no explanation of the lead time in the wheelchair example;

the time used for the demonstration of the wheelchair example was shorter than 3 min;

the time used to complete 10 cTTO tasks was shorter than 5 mins;

inconsistency in the cTTO ratings, as 55555 is not the lowest and is at least 0.5 higher than the health state with the lowest value.

All the interviews that did not meet all the above-mentioned criteria were discussed with the interviewers in person and were not necessarily excluded if the respondent demonstrated an understanding of the cTTO task according to the interviewer’s judgement.

Data Analysis

While DCE data were collected as part of the EuroQol Group’s valuation protocol, we chose to focus solely on TTO data in our study. This decision was based on standard guidelines for analysing health state preference data, as well as our assumption that the TTO data alone should provide sufficient and logically consistent estimates for our purposes [24].

Descriptive statistics of the sample characteristics and cTTO utilities were computed. No exclusions were made based on data quality. Similar to the previous valuation studies [15, 25–27], we excluded the responses flagged by respondents in the feedback module. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The cTTO data were modelled via the Tobit model, a statistical model used to analyse censored data, also known as the censored regression model. Censored data refer to observations that are either truncated or censored, meaning that the true value of the observation is unknown but is known to fall within a certain range. This is the case when the respondent is still not indifferent between a longer 20-year period of impaired health and immediate death and prefers to die immediately.

The variant of the Tobit model used in this paper is the model with conditional heteroscedasticity, which accounts for the fact that the variance of the error term may vary with the predictor variables. According to the recent systematic literature review, the (heteroscedastic) Tobit model with censoring at –1 is the most commonly estimated model when dealing with cTTO data [28].

If the variance of the error term is not constant but varies with the predictor variables, then failing to account for this in the model may result in a poor fit. By modelling heteroscedasticity, the model can better capture the relationship between the predictor variables and the dependent variable, leading to more accurate predictions.

Another advantage is that it can improve the interpretability of the model. If the variance of the error term is not constant, then the standard errors of the estimated coefficients may not accurately reflect the uncertainty in the estimates. By modelling the heteroscedasticity, the standard errors can be adjusted to account for the varying variance, resulting in more accurate inferences about the coefficients.

The dependent variable in the model was disutility [25, 29], defined as 1 minus the number of years at the indifference point divided by 10. For example, if the respondent was indifferent between 5 years in full health and 10 years of impaired health, that state would have a utility of 0.5 and a disutility of −0.5. As the cTTO values range from −1 (trading whole lead time) to 1 (trading no years in full health) the disutility ranged from −2 to 0, where −2 represents the censoring threshold and 0 indicates that the model has no constant.

In the following Tobit model specification, incremental dummies were used to test whether the effect of a categorical predictor on the disutility differs significantly between the reference category (‘No problems’) and each of the other categories (levels of problems). The variance of the error term was modelled with health dimensions treated as continuous variables (1—‘No problems’, …, 5—‘Unable/extreme problems’). The Tobit model had the following form:

where Y* is the latent and Y is the censored dependent variable. MO, SC, UA, PD, and AD are the predictor variables—health dimensions, where numbering corresponds to the level of problems, β1-20 are the model coefficients, −2 is the censoring threshold, and u is the error term. The error term in this model is assumed to have a conditional heteroscedasticity structure, meaning that the variance of the error term varies with the predictor variables MO, SC, UA, PD, and AD. σ(MO, SC, UA, PD, AD) is a function of the predictor variables that captures the variance of the error term, and ε is a normally distributed error term with a mean of 0.

Results

Respondent Characteristics

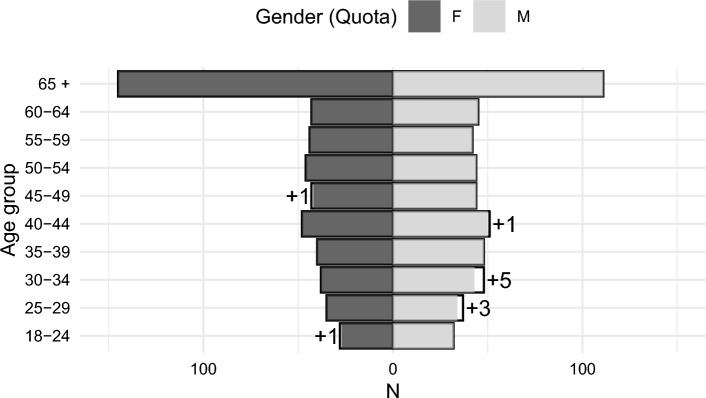

A total of 1012 respondents, representative of the Slovenia general population for age, sex and regions, were successfully interviewed (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the sample are summarised in Table 1. 38.5% of the respondents reported no problems in any of the five EQ-5D dimensions. The share of the respondents who reported any problems was highest in the PD dimension (51.9%), followed by MO (27.5%), UA (24.2%), AD (32.9%), and SC (11.2%). Not more than 0.5% of all respondents had extreme problems in any of the dimensions.

Fig. 1.

Sample of respondents by age and sex quotas. F female, M male

Table 1.

Demographics of the respondents in the Slovenian valuation sample

| Sampling characteristics | n | % | Population %a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 502 | 49.60 | 49.99 |

| Female | 510 | 50.40 | 50.01 |

| Age, years | |||

| 18–24 | 60 | 5.90 | 7.90 |

| 25–29 | 73 | 7.20 | 6.35 |

| 30–34 | 86 | 8.50 | 7.27 |

| 35–39 | 88 | 8.70 | 8.21 |

| 40–44 | 99 | 9.80 | 9.12 |

| 45–49 | 87 | 8.60 | 8.88 |

| 50–54 | 90 | 8.90 | 8.31 |

| 55–59 | 86 | 8.50 | 8.69 |

| 60–64 | 88 | 8.70 | 8.15 |

| 65+ | 256 | 25.30 | 27.12 |

| NUTS-2 region | |||

| East | 552 | 54.50 | 52.70 |

| West | 460 | 45.50 | 47.30 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 50 | 4.90 | 9.24 |

| Secondary school | 475 | 46.90 | 54.76 |

| University degree | 487 | 48.10 | 36.01 |

| Employment | |||

| Employed, self-employed | 590 | 58.30 | 52.00 |

| Unemployed | 27 | 2.70 | 4.10 |

| Retired | 283 | 28.00 | 29.50 |

| Student | 64 | 6.30 | 8.40 |

| Other | 48 | 4.70 | 6.10 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 419 | 41.40 | 59.40 |

| Single | 162 | 16.00 | 23.20 |

| Divorced | 62 | 6.10 | NA |

| Widowed | 72 | 7.10 | NA |

| In a partnership | 247 | 24.40 | 17.40 |

| Other | 50 | 4.90 | NA |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 | 331 | 32.70 | 29.80 |

| 1 | 234 | 23.10 | 38.60 |

| 2 | 346 | 34.20 | 25.20 |

| 3 or more | 101 | 10.00 | 6.40 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| History of serious illness | ||

| Self | 273 | 27.00 |

| In family | 693 | 68.50 |

| Caring for others | 405 | 40.00 |

| Self-rated health EQ-VAS | ||

| VAS [mean (SD)] | 83.6 | 8.30 |

| (0,80) | 285 | 28.20 |

| (80,90) | 261 | 25.80 |

| (90,100) | 405 | 40.00 |

| 100 | 61 | 6.00 |

| Self-rated health using a descriptive system | ||

| Mobility: No problems | 734 | 72.50 |

| Usual activities: No problems | 767 | 75.80 |

| Self-care: No problems | 899 | 88.80 |

| Pain/discomfort: No problems | 487 | 48.10 |

| Anxiety/depression: No problems | 780 | 77.10 |

Marital status and number of children in the population were based on data on families. Employment status and education in the population were based on age 15+ years; sex, age, and region were based on age 18+ years

NA not available, NUTS nomenclature of territorial units for statistics, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analogue scale

aSource: The Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia

Data Characteristics

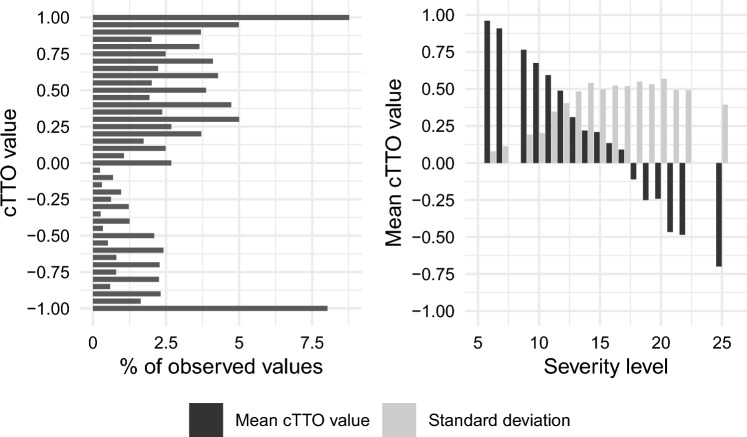

In our study, there were no missing responses for any valuation task, resulting in a total of 10,120 (5L) cTTO responses from 1012 respondents. In the feedback module, 582 (57.5%) respondents flagged at least one health state (n = 356 flagged one health state, n = 174 flagged two, n = 48 flagged three, and n = 4 flagged four health states). Overall, 864 (5L) cTTO responses were removed by respondents in the rank ordering. Thus, data analysis included 9256 (5L) cTTO observations from 1012 respondents. 29.6% of mean cTTO values were negative, and most of these worse-than-dead responses were elicited at −1 (8%). The proportion of values clustered at 0 was 2.7%, and 8.8% at 1 (Fig. 2). The higher the severity level (i.e., sum of levels across dimensions), the lower the mean cTTO value, whereby the standard deviation increases with the severity level (Fig. 2). The observed mean cTTO values ranged from −0.700 for health state 55555, to 0.959 for health state 21111.

Fig. 2.

Observed cTTO value distribution and cTTO composite time trade-off

EQ-5D-5L Value Set for Slovenia

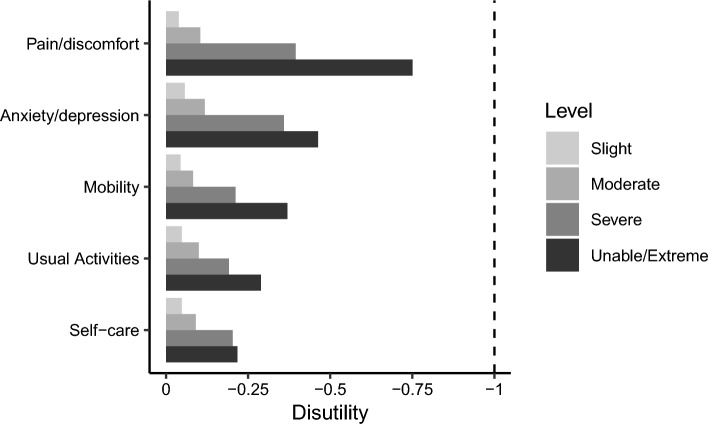

Results of the Tobit model are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 3. The incremental dummy variables in the model were used to test whether the effect of a categorical predictor on the disutility differs significantly between the reference category (‘No problems’) and each of the other categories (levels of problems). Because all regression coefficients are negative, this means that they are also logically consistent. With the exception of UA5 (unable to perform usual activities), all other levels on all health dimensions are statistically different from 0 and statistically different from each other. In the case of ‘usual activities’, a move from level 4 to level 5 was seen, on average, as worsening of health, although the difference was not statistically significant at 5%. Additionally, variance increased with any increase in severity level on all dimensions. An overview of the combined values of the incremental dummies is shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for the model

| Variable | Estimate | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables of the model | ||

| MO2: Slight problems | −0.044*** | 0.008 |

| MO3: Moderate problems | −0.038* | 0.015 |

| MO4: Severe problems | −0.129*** | 0.020 |

| MO5: Unable | −0.158*** | 0.021 |

| SC2: Slight problems | −0.048*** | 0.007 |

| SC3: Moderate problems | −0.052*** | 0.013 |

| SC4: Severe problems | −0.092*** | 0.018 |

| SC5: Unable | −0.097*** | 0.018 |

| SC2: Slight problems | −0.048*** | 0.007 |

| UA3: Moderate problems | −0.043** | 0.013 |

| UA4: Severe problems | −0.112*** | 0.016 |

| UA5: Unable | −0.014 | 0.018 |

| PD2: Slight problems | −0.039*** | 0.007 |

| PD3: Moderate problems | −0.065*** | 0.015 |

| PD4: Severe problems | −0.291*** | 0.018 |

| PD5: Extreme problems | −0.356*** | 0.021 |

| AD2: Slight problems | −0.057*** | 0.007 |

| AD3: Moderate problems | −0.061*** | 0.015 |

| AD4: Severe problems | −0.241*** | 0.016 |

| AD5: Extreme problems | −0.104*** | 0.017 |

| Independent variables of the variance | ||

| Constant | −2.565*** | 0.034 |

| MO | 0.112*** | 0.005 |

| SC | 0.089*** | 0.006 |

| UA | 0.089*** | 0.006 |

| PD | 0.130*** | 0.006 |

| AD | 0.150*** | 0.006 |

| Log-likelihood | −4930 | 26 Df |

SE standard error, MO Mobility, SC Self-care, UA Usual activities, PD Pain/discomfort, AD Anxiety/depression, 2,3,4,5 severity levels, *** indicates p < 0.001, ** indicates p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, Df degrees of freedom

Fig. 3.

Disutility estimates according to the EQ-5D-5L

Comparison of EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L Values

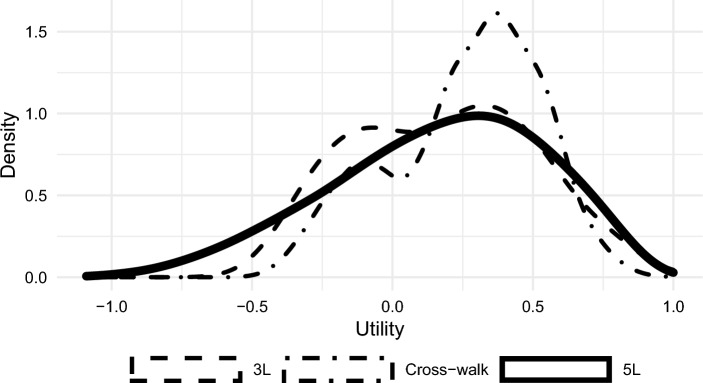

The kernel density plot of the 3125 values in the EQ-5D-5L value set shows a left-skewed distribution, whereas the EQ-5D-3L and crosswalk value sets are characterised by two peaks (bimodal distribution). The EQ-5D-5L value set covers a larger evaluation space without a constant as a deviation from full health (−1.090 to 1) than in the EQ-5D-3L and the crosswalk value sets (−0.495 to 1) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kernel density plot of all possible dimensions of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L

Discussion

In this study, a Slovenian value set for the EQ-5D-5L was estimated. In the estimation process, the latest EQ-VT protocol approved by the EuroQol Research Foundation was used. The Tobit model with conditional heteroscedasticity, based solely on cTTO data, produced a logically consistent and statistically significant parameter.

To date, there is no agreement on which modelling strategy might be the best in estimating value sets [30]. In some countries, only cTTO data were used to derive a value set [15, 31]. Using only cTTO data can deliver logically inconsistent estimates, therefore researchers used the DCE scoring algorithms [32] anchored on cTTO data or a so-called hybrid model [25–27, 33, 34], which uses both types of data, i.e. DCE and cTTO, to derive a value set.

There is no solid theoretical justification to combine both elicitation methods as they represent two very distinct valuation methods [30]. Namely, there are fundamental differences between the two methodologies that may exclude linking the DCE and cTTO data. A researcher can either assume that utility can be observed directly (as with cTTO) or that it cannot be, as it is latent, unobserved (DCE), but not both. While DCE, rooted in random utility theory, is a superior methodology for preference elicitations, its current design and protocol at EuroQol do not enable the estimation of a value set on its own.

The initial idea was to combine the cTTO and DCE data to address the issues that occurred with previous TTO data studies and led to logically inconsistent parameter estimates [28]. The pooling of TTO and DCE data is based on the assumption that there is a relationship between them and a constant proportionality assumption implied by the cTTO. In a study published in 2022, Augustovski et al. [35] found that it was not appropriate to combine the data. After estimating the value sets separately, the equivalence of their parameters was rejected and the DCE rejected the constant proportionality assumption implied by the cTTO [28]. Moreover, it has been shown that individuals were willing to give up more years of their life to avoid severe health states in TTO than in DCE (TTO tended to produce higher valuations for severe health states) [36].

The Slovenian EQ-5D-5L value set was also compared with the Romanian, Polish and Hungarian EQ-5D-5L value sets. These countries were selected for the comparison as they are geographically located in Central and Eastern European (CEE) and have certain similarities regarding their history and culture. Nevertheless, differences were noted between the four value sets in terms of values assigned to the worst health state or value range, model approach, and the relative importance of the five EQ-5D-5L dimensions. The value range was largest in Slovenia as Slovenians assigned the lowest value to the worst health state 55555 (Slovenia −1.090, Hungary −0.848, Poland −0.590 and Romania −0.323). The PD dimension was ranked highest in Slovenia, Romania and Poland, and came second in Hungary, where mobility was the most important dimension. The least important dimension in Slovenia was self-care, followed by usual activities, while in all other CEE countries, the least important dimension was usual activities [13–15].

Finally, modelling approaches in arriving to the final value set differ among countries: Hungary and Slovenia used only cTTO data for their model, while on the other hand, Poland and Romania used cTTO and DCE data for their final model. All these differences stress the importance of having a national value set for EQ-5D health states.

The distinct feature in the Slovenian value set is high disutility for the fifth level of PD dimension (extreme pain). In comparison with the EQ-5D-3L set, the disutility connected to PD was lower. High disutility could be connected to the translation of extreme pain and discomfort. The Slovenian translation of this dimension is more in terms of unbearable pain and discomfort instead of extreme. Although this does not impact the relative position of the pain and discomfort levels, some respondents might have felt that pain that someone cannot bear is worse and that it is only possible to choose ‘dead’ over unbearable pain/discomfort. The disutility attached to the extreme pain could hence be exaggerated.

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire has been widely used in population studies in Slovenia in the last few years. Users will benefit from a better descriptive system and the use of high-quality valuation data, which were derived from a more representative sample of the adult population. Furthermore, the EQ-5D-3L value set for Slovenia was obtained in 2005 and 2006. The EQ-5D-5L value set is a robust and up-to-date value set and should be the preferred value set used in adults in Slovenia and in neighbouring countries without their own value set.

Conclusions

The Slovenian cTTO-based EQ-5D-5L value set is recommended for use as an up-to-date EQ-5D value set in Slovenia. It is recommended for use in population studies, as well as in cost-utility studies, for decision making in clinical assessments and HTAs. EQ-5D is the only generic instrument with its own value set in Slovenia, enabling a refined preference-based HRQoL measurement to describe patients’ health. The set shows the relative importance that the Slovenian adult population places on different EQ-5D dimensions: greater importance is placed on the PD dimension followed by the AD dimension. The so-called physical EQ-5D dimensions (MO, SC, UA) seem to be less important for the Slovenians. Such societal preferences have implications for the assessment of treatments and should be taken into account in fund allocation decision making in health policy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Fannie Rencz and Bram Roudijk for their unwavering support, advice, and monitoring of the quality of the collected data throughout the data collection phase.

Declarations

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the EuroQol Group (EQ Project no. 377-VS).

Conflicts of interest

Valentina Prevolnik Rupel is a member of the EuroQol organization. Marko Ogorevc declares no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

Data will be available in the EuroQol Data Repository upon request.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed to the study concept, design, material preparation and data collection. The analysis was performed by MO, and the first draft of the manuscript was written by VPR and MO, who also commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. The funding for the study and the ethical approval was obtained by VPR.

Ethics approval

The study received approval from the Commission of the Republic of Slovenia for Medical Ethics (no. 0120-381/2021/6 dated 3 November 2021) prior to initiating recruitment and data collection.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to commencing the survey.

Consent for publication

All authors provide this consent.

Code availability

Please contact the corresponding author for any requests for any study materials including codes.

References

- 1.Rules on inclusion of medicines on the list [Pravilnik o razvrščanju zdravil na listo] (Uradni list RS, št. 35/13). http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=PRAV11493. Accessed 14 Jan 2023.

- 2.Ministry of Health of Republic of Slovenia. Procedures on handling the applications for new health care programmes [Slovenian] Ljubljana: Ministry of Health; 2015. http://www.mz.gov.si/si/o_ministrstvu/zdravstveni_svet_in_ostala_posvetovalna_telesa/zdravstveni_svet/postopek_za_vloge/. Accessed 23 Mar 2023.

- 3.Torrance GW. Measurement of health state utilities for economic appraisal. J Health Econ. 1986 doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(86)90020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996 doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brauer CA, Rosen AB, Greenberg D, Neumann PJ. Trends in the measurement of health utilities in published cost-utility analyses. Value Health. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim TH, Jo MW, Lee SI, Kim SH, Chung SM. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in the general population of South Korea. Qual Life Res. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EuroQol Organization. EQ-5D-5L. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/. Accessed 16 Jan 2023.

- 9.The EuroQol Group EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990 doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchholz I, Janssen MF, Kohlmann T, Feng YS. A systematic review of studies comparing the measurement properties of the three-level and five-level versions of the EQ-5D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0642-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janssen MF, Bonsel GJ, Luo N. Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prevolnik Rupel V, Ogorevc M. Crosswalk EQ-5D-5L value set for Slovenia. Zdr Varst. 2020 doi: 10.2478/sjph-2020-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olariu E, Mohammed W, Oluboyede Y, et al. EQ-5D-5L: a value set for Romania. Eur J Health Econ. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10198-022-01481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golicki D, Jakubczyk M, Graczyk K, Niewada M. Valuation of EQ-5D-5L Health States in Poland: the First EQ-VT-based study in Central and Eastern Europe. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00811-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rencz F, Brodszky V, Gulácsi L, et al. Parallel valuation of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L by time trade-off in Hungary. Value Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brulc U, Drobnič M, Kolar M, Stražar K. A prospective, single-center study following operative treatment for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turk E, Mičetić-Turk D, Šikić-Pogačar M, Tapajner A, Vlaisavljević V, Prevolnik RV. Health related QoL in celiac disease patients in Slovenia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):356. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01612-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health. National Quality and Safety Strategy 2023-2031. Available at: https://www.gov.si/zbirke/javne-objave/nacionalna-strategija-kakovosti-in-varnosti-v-zdravstvu-2023-2031/. Accessed 14 Jan 2023.

- 19.HealthCare Databases Act [Zakon o zbirkah podatkov s področja zdravstvenega varstva]. Official Gazette 65/00, 141/22. http://pisrs.si/Pis.web/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO1419# Accessed 14 Jan 2023.

- 20.Oppe M, Devlin NJ, van Hout B, Krabbe PF, de Charro F. A program of methodological research to arrive at the new international EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, van Hout B, Ramos-Goñi JM. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation protocol. Value Health. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devlin NJ, Tsuchiya A, Buckingham K, Tilling C. A uniform time trade-off method for states better and worse than dead: feasibility study of the ‘lead time’ approach. Health Econ. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hec.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos-Goñi JM, Oppe M, Slaap B, Busschbach JJV, Stolk E. Quality control process for EQ-5D-5L valuation studies. Value Health. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rowen D, AzzabiZouraq I, Chevrou-Severac H, van Hout B. International regulations and recommendations for utility data for health technology assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0544-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig K, Graf von der Schulenburg JM, Greiner W. German value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0615-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobbins A, Barry L, Kelleher D, et al. Utility values for health states in Ireland: a value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0690-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purba FD, Hunfeld JAM, Iskandarsyah A, et al. The Indonesian EQ-5D-5L value set. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowen D, Mukuria C, McDool E. A systematic review of the methodologies and modelling approaches used to generate international EQ-5D-5L value sets. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s40273-022-01159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouckaert N, Cleemput I, Devriese S, Gerkens S. An EQ-5D-5L value set for Belgium. Pharmacoeconomics Open. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s41669-022-00353-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummond M, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Versteegh M, Vermeulen K, Evers S, de Wit GA, Prenger R, Stolk E. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiroiwa T, Ikeda S, Noto S, et al. Comparison of value set based on DCE and/or TTO data: scoring for EQ-5D-5L health states in Japan. Value Health. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.03.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira PL, Antunes P, Ferreira LN, Pereira LN, Ramos-Goni JM. A hybrid modelling approach for eliciting health state preferences: the Portuguese EQ-5D-5L value set. Qual Life Res. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrade LF, Ludwig K, Goni JMR, Oppe M, de Pouvourville GA. French value set for the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00876-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Augustovski F, Belizá M, Gibbons L, Reyes N, Stolk E, Craig BM, Tejada RA. Peruvian valuation of the EQ-5D-5L: a direct comparison of time trade-off and discrete choice experiments. Value Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson A, Spencer AE, Pinto-Prades JL, Covey JA. Exploring differences between TTO and DCE in the valuation of health states. Med Decis Making. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0272989X16668343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available in the EuroQol Data Repository upon request.