Abstract

Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit seeds, also known as river tamarind, contain sulfhydryl compounds that exhibit antioxidant effects. However, these seeds also possess a toxic effect from mimosine. In this study, the river tamarind seeds were extracted using a natural deep eutectic solvent (NADES) based UAE. Among six NADES compositions screened, choline chloride-glycerol (ChCl-Gly) and choline chloride-sucrose (ChCl-Suc) were selected to be further optimized using a Box-Behnken Design in the RSM. The optimization of total sulfhydryl content was performed in 17 runs using three variables, namely water content in NADES (39%, 41%, and 43%), extraction time (5, 10, and 15 min), and the liquid-solid ratio (3, 5, and 7 mL/g). The highest concentration of sulfhydryls was obtained from ChCl-Gly-UAE (0.89 mg/g sample) under the conditions of a water content in NADES of 41% (v/v) and a liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g for 15 min, followed by that of from ChCl-Suc-UAE extract under the conditions of water content in NADES of 43% (v/v) and the liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g for 10 min with total sulfhydryl level was 0.67 mg/g sample. The maceration method using 30% ethanol resulted in the lowest level of sulfhydryls with a value of 0.52 mg/g. The mimosine compounds obtained in the NADES-based UAE (ChCl-Suc and ChCl-Gly) extracts were 4.95 and 7.67 mg/g, respectively, while 12.56 mg/g in the 30% ethanol-maceration extract. The surface morphology of L. leucocephala seed before and after extraction was analyzed using scanning electron microscopy. Therefore, it can be concluded that the use of ChCl-Suc and ChCl-Gly in NADES-based UAE is more selective in attracting sulfhydryl compounds than that of 30% ethanol-maceration extraction.

Keywords: Box-Behnken design, Leucaena leucocephala, Mimosine, Natural deep eutectic solvent, Thiols

1. Introduction

Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit, which belongs to the Fabaceae family, is a perennial legume plant that can live for a long time [1]. The river tamarind, a common name for this plant, contains chemical constituents that have been proven to exhibit biological activities such as antioxidant, antidiabetic [2], and anticancer [3]. These phytochemicals are mainly found in the leaves and seeds [4].

The distinctive aroma from the seeds of river tamarind indicates the presence of sulfhydryl compounds (thiols) [5]. Based on the study done by Wardatun et al. (2020), the total sulfhydryl level in the river tamarind seeds was found to be higher than those of other Fabaceae family plants, including in Parkia speciosa Hassk and Archidendron jiringa (Jack) I. C. Nielsen [6].

Sulfhydryl groups can act as essential antioxidants to protect cells from oxidative stress by interacting with the electrophilic groups of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [7]. Furthermore, thiols can also be used as chelating agents to detoxify heavy metal ions such as Pb, Hg, and Cd [8]. However, the extraction of sulfhydryls from the L. leucocephala seeds is quite challenging due to other toxic compounds in the seeds, such as mimosine [6,9]. Therefore, the proper extraction method is critical in attracting optimum levels of desired compounds while eliminating unwanted compounds.

The extraction of sulfhydryls from the river tamarind seeds has been successfully demonstrated by Wardatun et al. (2020) using the maceration method with 30% ethanol [6]. Unfortunately, such a conventional method is ineffective as it needs lots of solvents and is time-consuming [10]. Furthermore, using semi-polar solvents like ethanol could attract polar and non-polar compounds. Thus, the method does not efficiently extract targeted compounds in the material. In addition, the use of organic solvent is unfavorable due to its properties which are flammable, volatile, toxic, carcinogenic, and non-biodegradable [11].

The design of sustainable and environmentally friendly natural product extraction processes is a current approach that researchers widely used to develop more efficient extraction methods. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) were first introduced by Choi et al. (2011) and can be expressed as a “green solvent” [12]. NADES as an extraction solvent is often used in applications in the pharmaceutical field because it has beneficial properties, including adjustable viscosity, a broad extraction capability, stability in the liquid state at room temperature, low volatility, non-flammability, low toxicity, sustainability, inexpensive, environmentally friendly, and bio-degradable [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. In addition, NADES can extract polar and non-polar compounds based explicitly on their composition and has better results than conventional solvents such as water, ethanol, and methanol [18]. Many studies have successfully applied NADESs in extraction such as alkaloids [19], anthocyanins [20], saponins [21], phenyletanes and phenylpropanoids [22], steroidal saponins [23], phlorotannins [24], polysaccharides [25], carotenoids and hydrophylic vitamins [26].

The prolonged extraction time and the excessive use of solvents caused the ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) method to become a new method that is more efficient and can increase the efficiency of compound extraction [26]. The combination of UAE and NADES is expected to realize the concept of sustainable green extraction [27]. One of the advantages of NADES-UAE is that the method can attract higher active compounds selectively with lower levels of toxic compounds in a relatively short time compared to conventional methods [28,29].

The successful extraction of polar bioactive compounds from plants, such as rutin, caffeine, and chlorogenic acid using NADES choline chloride-sugar alcohol combined with the UAE method has been reported in a few studies [30,31]. Other studies done by Dai et al. were also successfully used lactic acid, glucose, choline chloride, fructose, and sucrose to extract metabolite compounds from natural products [[32], [33], [34], [35]]. However, the application of NADES-based UAE on sulfhydryls and mimosine from L. leucochepala seed has never been reported.

The main objective of this study was to design and optimize the extraction conditions of targeted secondary metabolites (sulfhydryl compounds) from L. leucocephala seeds using NADES with a composition of choline chloride, and sugars (simple sugars and sugar alcohols) such as sucrose, fructose, glucose, glycerol, sorbitol, and 1,2-propanediol with the UAE method. The study consists of two phases. In the initial step, we evaluated the effectiveness of two types of NADES compositions, including choline chloride-simple sugars and choline chloride-sugar alcohols. The selected NADES compositions were then subjected to the optimization of extraction parameters, including the NADES-water ratio, solid-liquid ratio, and extraction time determined using response surface methodology (RSM). The optimum conditions were achieved when the total sulfhydryl level obtained from L. leucochephala seeds using NADES-UAE was high. The unwanted compound, mimosine, was low compared to the 30% ethanol maceration results.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Plant material

The commercial of L. leucocephala seeds was purchased from e-Commerce, Banten, Indonesia. The sample was authenticated by Herbarium Bogoriense, Bogor Botanical Garden, Bogor, West Java, Indonesia, and the voucher specimen (15/LPP-FFUI/VII/2021) was deposited at Pharmacognosy – Phytochemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Indonesia.

2.1.2. Chemical materials

Chemical materials used in this study include glucose (≥99.5%) (Merk, Germany), fructose (≥99%) (Merk, Germany), sucrose (Merk, Germany), glycerol (≥99.5%) (P&G Chemicals Malaysia through PT. Brataco, Indonesia), sorbitol and 1,2-propanediol (Pharmaceutical grade) (Dow Chemical Pacific Thailand through PT. Brataco, Indonesia), choline chloride (99%) (Xi'an Rongsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Tiongkok), l-glutathione reduced ≥98.0% (GSH) standard, 5-5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB: Ellman's reagent) ≥ 98%, and l-mimosine standard (≥98%) (Sigma-Aldrich through PT. Indofa Utama Multi-Core, Indonesia).

2.2. Extraction process

2.2.1. Maceration method

The maceration process was carried out based on our previous studies [36]. Briefly, the dried L. leucochepala seed powder (50 g) was macerated for 24 h with 250 mL of 30% ethanol at room temperature. The residue from the maceration process was re-macerated twice using 150 mL and 100 mL of solvent consecutively. The extract solution was separated from the residue, pooled into a round-bottom flask, and then subjected to vacuum evaporator (Buchi Switzerland) at 60 °C until viscous extract was obtained. The obtained extract (5.41 g) was put into a vial and then sealed with aluminum foil to avoid direct light exposure.

The sample solution was prepared to analyze the total sulfhydryl levels, 500 mg of the obtained concentrated extract was dissolved with distilled water (DW) in a 5-mL volumetric flask. The solution was then subjected to a microplate reader to determine the total sulfhydryl levels in the extract. 500 mg of concentrated extract were dissolved in 2.0 mL of DW to analyze the mimosine level. After that, 30 mg of activated carbon was added. The solution was then boiled for 15 min. Next, the solution was filtered using a syringe (Axiva 0.45 μm) into a 5-mL volumetric flask. About 2.5 mL of 0.1 N HCl was added into the flask and diluted with DW to the level of the etched line.

2.2.2. NADES-based ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) method

2.2.2.1. Screening and preparation of NADES types composition

The NADES components and the molar ratio used (Table 1) were based on the previous studies that have successfully demonstrated the use of NADES combination to extract polar bioactive compounds from plants [30,31,37]. NADES is a mixture of hydrogen bond donor (HBD) and hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) (Zafarani-Moattar et al., 2020). In this study, the combination of sugar (simple sugar and sugar alcohol) as HBD and choline chloride as HBA was chosen since the ingredients are easy to obtain, affordable, and less toxic. The NADES preparation process was performed using the heating and stirring methods. The ingredients were added together according to a predetermined molar ratio and heated at a temperature of 80 °C. The solution was considered stable if it remained clear throughout storage.

Table 1.

Different types of NADES.

| No. | NADES Types |

Mole Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBA | HBD | Abbreviation | ||

| 1 | Choline chloride | Sucrose | ChCl-Suc | 1:1 |

| 2 | Choline chloride | Fructose | ChCl-Fru | 1:1 |

| 3 | Choline chloride | Glucose | ChCl-Glu | 1:1 |

| 4 | Choline chloride | Glycerol | ChCl-Gly | 1:1 |

| 5 | Choline chloride | Sorbitol | ChCl-Sor | 4:1 |

| 6 | Choline chloride | 1,2-Propanediol | ChCl-Pro | 1:1 |

Six NADES were produced by mixing choline chloride with simple sugars (glucose, sucrose, and fructose) or sugar alcohols (glycerol, sorbitol, and 1,2-propanediol) based on the composition given in Table 1. Each NADES composition for the screening was prepared by adding 70% (v/v) of water into NADES (10 mL of NADES was mixed with 7 mL of water); or the mixture contains 59% of NADES and 41% of water.

2.2.2.2. Optimization of extraction process by NADES-based UAE method

The process of extraction was conducted using NADES-based UAE according to previous studies with some modifications on the NADES types composition [[38], [39], [40]]. Briefly, 5 g of powdered sample were put into a closed glass bottle. The amount of NADES solution was added, followed by the sonication process according to the specific extraction conditions, as shown in Table 2. The obtained NADES extraction liquid was moved into a tube and centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 17 min. Subsequently, the solid and liquid parts were separated by filtration using a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membrane. The obtained extract was then stored in closed vials and protected from light.

Table 2.

Experimental design.

| Factors | Unit | Symbol | Level |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (−1) | Mid (0) | High (1) | |||

| Water content in NADES | % (v/v) | A | 39 | 41 | 43 |

| Extraction Time | Min | B | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| Liquid-Solid Ratio | mL/g | C | 3 | 5 | 7 |

The solubilizing and extraction abilities of each synthesized NADES were evaluated by quantifying the total sulfhydryl contents in the obtained extract. The extraction conditions, as follows: liquid-solid ratio of 5 mL/g, 41% water content, and 10 min of sonication time, were kept the same for all the investigated NADES.

2.3. Determination of sulfhydryl content

Before quantifying the total sulfhydryl groups (TSH), the analytical method used (microplate reader) was validated. The validation details can be seen in Supplementary data 1.

The total sulfhydryl level (TSH) was examined using Ellman's method, with slight modifications for adjusting tools specification [6,[41], [42], [43]]. Briefly, 600 μL of samples and 2400 μL of 200 mM potassium phosphate buffer (K2HPO4/NaOH) pH 7.4 were added to 300 μL of 1 mM DTNB reagent and vortexed for 10 s. Then the mixed solutions were kept at room temperature for 2 min. Next, the absorbance of each sample (200 μL) was measured using a 96-well microplate reader at the maximum wavelength of 416 nm. The TSH was expressed as a reduced l-glutathione (GSH) equivalent.

2.4. Determination of mimosine levels

Preliminary to the determination of mimosine levels, analytical method validation was conducted. The validation details can be found in Supplementary data 2.

Mimosine content in L. leucochepala seeds extract was quantified using a rapid colorimetric method [36,[44], [45], [46]], with slight modification for adjusting tools specification. Briefly, 200 μl of the prepared sample solution was pipetted and then put into a 5 mL conical flask. Subsequently, 400 μl of 0.1 N HCl and 200 μl of 0.5% FeCl3 in 0.1 N HCl were added and diluted with DW until the level of the etched line. The mixture was maintained at room temperature for 10 min before being analyzed at 534 nm, as the maximum wavelength, using a spectrophotometer UV-VIS.

2.5. Design experiments for optimizing NADES-based UAE

NADES-based UAE of sulfhydryl was conducted in three different factors and levels, including NADES-water ratio (A), extraction time (B), and liquid-solid ratio (C), as shown in Table 2. Seventeen experimental runs with random order of five central point replications for response surface testing, were simulated by the RSM with a three-factor and three-level design method. The multilinear quadratic regression equation was applied in the response surface analysis to forecast the dependent variables and assess the effects of NADES-based UAE condition factor, as follows (1):

| (1) |

The effect of each factor was analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The final model included terms with a 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05) and those required to maintain the hierarchy of model terms. The best-fitted model was developed using a multiple linear regression analysis. The model validity was assessed using F-values, p-values, Lack of Fit, coefficient of determination (R2), estimated coefficient, and variance inflation factor (VIF). Optimal extraction conditions were calculated to maximize the extraction efficiency of all target compounds simultaneously. The model adequacy was confirmed by extraction under the predicted optimal conditions in triplicate. The experimental design, optimization, and construction of three-dimensional response surface plots were performed using the licensed version of Design Expert 12 software (Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, USA). The data and graphical figures for the total sulfhydryl levels and comparison of sulfhydryl and mimosine content in L. leucochepala were statistically analyzed (ANOVA) and created using GraphPad Prism 9.5.1. (Free Trial).

2.6. Surface morphology of L. leucocephala seed powder

The comparison of surface morphology of the samples before and after the extraction process (maceration and sonication) were observed using JOEL scanning electron microscopy (JSM-5510LV) according to literature [[47], [48], [49]]. Briefly, Powdered L. leucocephala seeds (before and after sonication) were placed on a carbon plate and laminated with a palladium-gold thin layer to create a conductive surface. The procedure was performed under a vacuum. Then the samples were subjected and directly screened under SEM at various magnifications and 20 kV.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation and selection of NADES

The formation time needed to produce NADES was different depending on its compositions. NADES with the composition of ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Pro required faster time compared to ChCl-Suc, ChCl-Fru, ChCl-Glu, and ChCl-Sor. This is because glycerol and 1,2-propanediol are liquid, while sucrose, fructose, and glucose are in solid form. In addition, the melting point of glycerol and 1,2-propanediol (18 °C and 59 °C, respectively) are lower than sorbitol (88–102 °C) in liquid form. Moreover, another factor that can affect the formation time is the number of hydroxyl group branches in HBD. The more complex the structure and hydroxyl groups in HBD, the more difficult it will be for the halide anion from HBA to bind to the hydroxyl group of HBD [[50], [51], [52]]n this case, sorbitol has six hydroxyl groups and a more complex structure than the other NADES, so it requires a longer formation time because the halide anions from HBA will be more difficult to bind to the HBD hydroxyl groups.

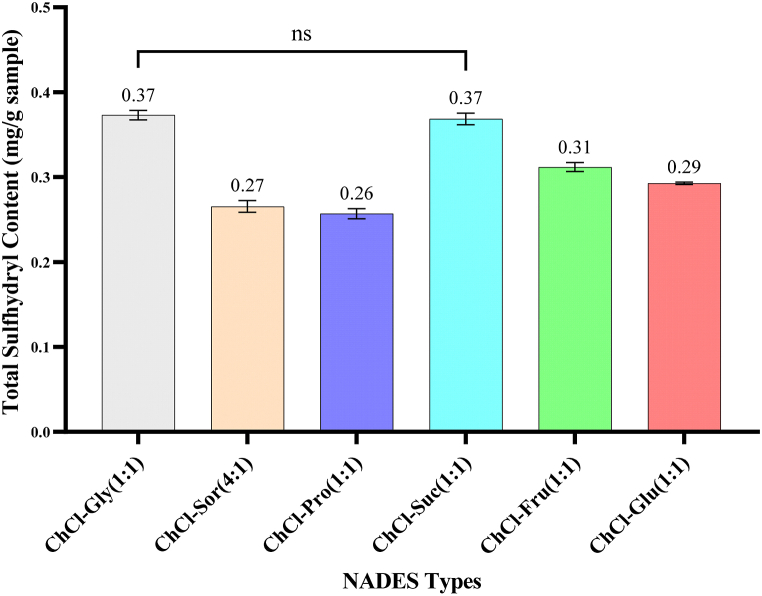

The yield of total sulfhydryl levels derived from each NADES was different, as presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Total sulfhydryl levels of L. leucochepala seed extract obtained from various NADES types composition (ChCl: choline chloride; Gly: glycerol; Sor: sorbitol; Pro: 1,2-propanediol; Suc: sucrose; Fru: fructose; Glu: glucose).

Fig. 1 depicts the total sulfhydryl content in the powdered tamarind river seeds extracted with different NADES compositions. Statistically, the sulfhydryl levels in extract derived from each NADES were significantly different except for ChCl-Gly (1:1) and ChCl-Suc (1:1) (p < 0.05). Among six observed NADES, the highest level of total sulfhydryls was recovered from ChCl-Gly (1:1) and ChCl-Suc (1:1) with the same concentration (0.37 mg/g sample). In contrast, the combination of choline chloride with 1,2-propanediol performed the lowest sulfhydryl content (0.26 mg/g sample). The difference in sulfhydryl level in obtained extracts can be influenced by several factors, such as the physicochemical characteristics of the solvents, including the viscosity, polarity, surface tension, the water content in NADES, and the interaction of hydrogen bonds between NADES and other compounds can affect the level of desired compounds [[53], [54], [55]].

The NADES composition, ChCl-Gly (1:1) and ChCl-Suc (1:1), were then opted to be further optimized using RSM. These two solvents were chosen since they attract higher sulfhydryl content in the river tamarind seed than other tested solvents.

3.2. Optimization of NADES-based UAE process

Two NADES compositions, ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc, were selected for the optimization extraction process based on the highest total sulfhydryl level obtained from the initial screening. To perform the optimization process, a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) involving 17 runs was used to determine the effects of three experimental conditions, including water content in NADES (39, 41, and 43%v/v), extraction time (5, 10, and 15 min), and liquid-solid ratio (3, 5, and 7 mL/g) and each condition was performed in triplicate. BBD is easier and more efficient to apply in experiments than other RSM designs [50,56]. The BBD matrix for the experimental design and observed responses for sulfhydryl levels (mg/g sample) have been summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The result of sulfhydryl content from L. leucocephala seed-based experimental design (17 trials) using RSM with BBD.

| Run | Water content in NADES (%) | Extraction time (Min) | Liquid-solid ratio (ml/g) | Sulfhydryl Content (mg/g) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChCl-Gly | ChCl-Suc | ||||

| 1 | 43 | 15 | 5 | 0.45 | 0.51 |

| 2 | 41 | 15 | 7 | 0.37 | 0.32 |

| 3 | 41 | 10 | 5 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| 4 | 43 | 5 | 5 | 0.21 | 0.44 |

| 5 | 39 | 10 | 7 | 0.29 | 0.42 |

| 6 | 43 | 10 | 3 | 0.36 | 0.67 |

| 7 | 41 | 5 | 3 | 0.38 | 0.28 |

| 8 | 41 | 10 | 5 | 0.39 | 0.36 |

| 9 | 41 | 10 | 5 | 0.36 | 0.35 |

| 10 | 39 | 10 | 3 | 0.57 | 0.37 |

| 11 | 43 | 10 | 7 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| 12 | 41 | 15 | 3 | 0.89 | 0.30 |

| 13 | 41 | 5 | 7 | 0.38 | 0.29 |

| 14 | 41 | 10 | 5 | 0.32 | 0.39 |

| 15 | 41 | 10 | 5 | 0.32 | 0.37 |

| 16 | 39 | 5 | 5 | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| 17 | 39 | 15 | 5 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

Table 3 shows that the highest concentration of sulfhydryls (0.89 mg/g sample) using ChCl-Gly as solvent was obtained from the conditions of 41% (v/v) of water content, the liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g, and an extraction time of 15 min (as can be seen in the run 12). For ChCl-Suc, the highest sulfhydryl level was achieved from the extract with factor conditions: water content in NADES of 43% (v/v), sonication for 10 min, and the liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g samples (run 6).

3.2.1. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for optimization of NADES (ChCl-Gly) based UAE

To investigate the significance and the correlation of independent variables with total sulfhydryl level, the experimental data were evaluated using the ANOVA. The model of quadratic regression was used as suggested in the Fit Summary.

The ANOVA of the quadratic regression model (Table 4) indicates that the model was highly significant, with an F-value of 11.35 with a shallow probability value of 0,0021 (p < 0.05). In addition, the coefficient of determination (R2), 0.9358, also demonstrated that the model could explain 93% of the variability in the response. Moreover, the Lack of Fit (LOF) F-value of 6.53 with a p-value of 0.0508 (p > 0.05) implies that the LOF is not significant (the model fits well).

Table 4.

AVONA of ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc based UAE.

| Source | Sum of Square | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChCl-Gly based UAE | |||||

| Model | 0.3407 | 9 | 0.0379 | 11.35 | 0.0021 |

| A- Water content in NADES | 0.0030 | 1 | 0.0030 | 0.911 | 0.3717 |

| B-Extraction Time | 0.0706 | 1 | 0.0706 | 21.15 | 0.0025 |

| C-Liquid-Solid Ratio | 0.0930 | 1 | 0.0930 | 27.06 | 0.0012 |

| AB | 0.0126 | 1 | 0.0126 | 3.77 | 0.0932 |

| AC | 0.0123 | 1 | 0.0123 | 3.70 | 0.0960 |

| BC | 0.0670 | 1 | 0.0670 | 20.08 | 0.0029 |

| A2 | 0.0291 | 1 | 0.0291 | 8.71 | 0.0213 |

| B2 | 0.0084 | 1 | 0.0084 | 2.51 | 0.1569 |

| C2 | 0.0506 | 1 | 0.0506 | 15.18 | 0.0059 |

| Residual | 0.0234 | 7 | 0.0033 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0194 | 3 | 0.0065 | 6.53 | 0.0508 |

| Pure Error | 0.0040 | 4 | 0.0010 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.3640 | 16 | |||

| R2 = 0.9358; CV = 14.93%; Adj R2 = 0.8534 | |||||

| ChCl-Suc based UAE | |||||

| Model | 0.15 | 9 | 0.017 | 26.84 | 0.0001 |

| A- Water content in NADES | 0.058 | 1 | 0.058 | 94.31 | <0.0001 |

| B-Extraction Time | 0.0023 | 1 | 0.0023 | 3.70 | 0.0960 |

| C-Liquid-Solid Ratio | 0.0013 | 1 | 0.0013 | 1.91 | 0.2097 |

| AB | 0.0003 | 1 | 0.0003 | 0.56 | 0.4805 |

| AC | 0.0121 | 1 | 0.0121 | 19.81 | 0.003 |

| BC | 0.00003 | 1 | 0.00003 | 0.041 | 0.8461 |

| A2 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.051 | 82.27 | <0.0001 |

| B2 | 0.027 | 1 | 0.027 | 43.71 | 0.0003 |

| C2 | 0.0006 | 1 | 0.0006 | 0.98 | 0.3544 |

| Residual | 0.0043 | 7 | 0.00062 | ||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0035 | 3 | 0.00118 | 6.01 | 0.0580 |

| Pure Error | 0.0008 | 4 | 0.00019 | ||

| Cor Total | 0.1535 | 16 | |||

| R2 = 0.9718; CV = 6.33%; Adj R2 = 0.979 | |||||

From the p-values of each variable (p < 0.05), two linear coefficients (extraction time (B) and liquid-solid ratio (C)), one interactive coefficient (BC), and two quadratic coefficients (A2 and C2) seemed to be significant, which described that the terms had remarkable effects on sulfhydryls extraction. The water content in NADES did not significantly affect the sulfhydryl levels on the sample extracted with ChCl-Gly-based UAE.

Table 5 shows that, when all factors are constant, the coefficient estimates represent the expected changes in the response per unit in factor values. The intercept value of 0.35 is the overall average response of all processes in the orthogonal design. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value equals one when the factors involved are in an orthogonal position. VIF is a correlation parameter between factors. A VIF value greater than one indicates multicollinearity. The higher the VIF value, the worse the factor correlation. As a rough rule, a VIF of less than 10 is tolerable [[57], [58], [59], [60]].

Table 5.

Coefficients in terms of codec factors for sulfhydryl extraction from L. leucocephala seeds.

| Factors | Coefficient Estimate | df | Standard Error | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChCl-Gly based UAE | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.35 | 1 | 0.026 | 0.29 | 0.41 | |

| A – Water content in NADES | −0.019 | 1 | 0.020 | −0.068 | 0.029 | 1.00 |

| B – Extraction Time | 0.094 | 1 | 0.020 | 0.046 | 0.14 | 1.00 |

| C – Liquid-Solid Ratio | −0.11 | 1 | 0.020 | −0.15 | −0.058 | 1.00 |

| AB | 0.056 | 1 | 0.029 | −0.012 | 0.12 | 1.00 |

| AC | 0.055 | 1 | 0.029 | −0.013 | 0.12 | 1.00 |

| BC | −0.13 | 1 | 0.029 | −0.20 | −0.061 | 1.01 |

| A2 | −0.083 | 1 | 0.028 | −0.15 | −0.016 | 1.01 |

| B2 | 0.045 | 1 | 0.028 | −0.022 | 0.11 | 1.01 |

| C2 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.028 | 0.043 | 0.18 | 1.01 |

| ChCl-Suc based UAE | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.37 | 1 | 0.011 | 0.34 | 0.39 | |

| A – Water content in NADES | 0.085 | 1 | 0.0088 | 0.064 | 0.011 | 1.00 |

| B – Extraction Time | 0.017 | 1 | 0.0088 | −0.039 | 0.038 | 1.00 |

| C – Liquid-Solid Ratio | −0.012 | 1 | 0.0088 | −0.033 | 0.0086 | 1.00 |

| AB | 0.0093 | 1 | 0.012 | −0.020 | 0.039 | 1.00 |

| AC | −0.055 | 1 | 0.012 | −0.085 | −0.026 | 1.00 |

| BC | 0.0025 | 1 | 0.012 | −0.027 | 0.032 | 1.00 |

| A2 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.012 | 0.081 | 0.14 | 1.01 |

| B2 | −0.080 | 1 | 0.012 | −0.11 | −0.051 | 1.01 |

| C2 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.012 | −0.017 | 0.041 | 1.01 |

Furthermore, based on the analysis results was obtained the best model of the multilinear quadratic regression equation was as follows:

| (2) |

Y1 is the total sulfhydryl content from L. leucocephala seed using NADES (ChCl-Gly) based UAE, A is the water content in NADES, B is extraction time, and C is the liquid-solid ratio. The design space can be used to explored using this equation model (2) and the equation is needed to determine the activity response mainly using different variable factor values.

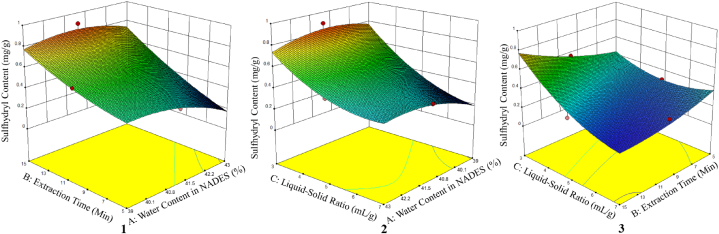

In addition, the obtained optimization results can be visualized as a three-dimensional (3D) response surface graph. Fig. 2 illustrates the relationships between the variables including water content in NADES and extraction time (Fig. 2(1)); water content in NADES and the ratio of solid to liquid (Fig. 2(2)); extraction time and the ratio of solid to liquid (Fig. 2(3)), which were plotted in a 3D response graph of sulfhydryl content from L. leulocephala seed. A cross-section of the graph reveals that the sulfhydryl level will be higher in the red area and lower in the light blue area (as shown in the contour plot) [61].

Fig. 2.

The three-dimensional (3D) contour of the response surface plot representing (1) extraction time and water content in NADES; (2) liquid-solid ratio and water content in NADES; and (3) liquid-solid ratio and extraction time on the response of sulfhydryl content from L. leucocephala seed using NADES (ChCl-Gly) based UAE.

3.2.2. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for optimization of NADES (ChCl-Suc) based UAE

Meanwhile, the optimization of ChCl-Suc based UAE condition in extracting sulfhydryls content from L. leucocephala seed was obtained by analyzing the experimental data (Table 3) with quadratic regression model. The F-value of 26.86, as shown in Table 4, indicates that the model was highly significant (p < 0.05), where there is only a 0.01% chance such an F-value could occur due to noise. The Fit of the model was also expressed by the determination coefficients (R2), which was 0.9728, suggesting that the model could explain 97% of the variability in the response. Moreover, the LOF F-value of 6.01 with a p-value of 0.0580 (p > 0.05) implies that the model fits well since the LOF is insignificant. In addition, the greater reliability of the experiment was shown by a lower value of the coefficient of variance (CV) (6.33%).

As presented in Table 4 (ChCl-Suc based UAE), the significance of each coefficient is indicated by the p-values. The significance of the corresponding coefficient increases as the p-value decreases. One linear coefficient (water content in NADES (A)), one interactive coefficient (AC), and two quadratic coefficients (A2 and B2) notably impacted the extraction of sulfhydryls from the samples (p < 0.05).

From Table 5 (ChCl-Suc), the intercept value of 0.37 indicates the overall average response of all processes in the orthogonal design. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value equals one when the factors involved are in an orthogonal position. The VIF value is in the range of 1.00–4.00, which is the correlation parameter between factors (VIF <10 is tolerable) [[57], [58], [59], [60]].

Based on the results was obtained the best model of the multilinear quadratic regression equation was as follows:

| (3) |

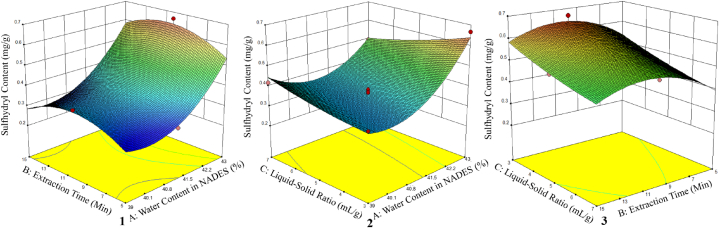

where Y2 is sulfhydryl content from L. leucocephala seed using NADES (ChCl-Suc) based UAE, this equation model (3) can be used to navigate the design space. Fig. 3 depicts interaction effects between the extraction parameter factors on sulfhydryl level from L. leucocephala seed which are plotted in the 3D response graphs. The interaction between parameters includes the water content in NADES and extraction time (Fig. 3(1)); water content in NADES and liquid-solid ratio (Fig. 3(2)); and extraction time and liquid-solid ratio (Fig. 3(3)).

Fig. 3.

The three-dimensional (3D) contour of the response surface plot representing (1) extraction time and water content in NADES; (2) liquid-solid ratio and water content in NADES; and (3) liquid-solid ratio and extraction time on the response of sulfhydryl content from L. leucocephala seed using NADES (ChCl-Suc) based UAE.

3.2.3. The optimum condition of NADES-based UAE and the effect of interaction factors

The optimal conditions of both NADES type compositions were determined by the RSM analysis using the licensed Design Expert v12 software. These conditions were derived from equations (2), (3)). The optimal conditions of ChCl-Gly based UAE was predicted using equation (2). The extraction process involved a water content of 41% and the liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g, with an extraction period of 15 min. This generated in a sulfhydryl level of 0.84 ± 0.06 mg/g. While for the conditions of NADES (ChCl-Suc) based UAE, equation (3) was employed to forecast the optimum parameters. The optimal circumstances were determined to be a water content of 43% and a liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g for 10 min resulting 0.64 ± 0.03 mg/g of sulfhydryl content values. The predicted yields of sulfhydryl level (optimum condition) obtained from both ChCl-Gly based UAE and ChCl-Suc based UAE were confirmed by experimental laboratory (in triplicate) resulting the actual data of sulfhydryl content of 0.89 ± 0.04 and 0.67 ± 0.36 mg/g, respectively.

Due to its significance in the interactions between solutes and solvents, hydrogen bonding is a crucial in NADES based extraction [62]. The Cl and O atoms in ChCl-based NADES molecules exhibit a high electronegativity, enabling them to readily receive hydrogen and establish hydrogen bonding interactions with solvents and solutes. In a recent study, the molecular transport of HBD and choline cations (Ch+) in various DESs derived from ChCl was investigated. The structure of HBD was found to strongly influence the molecular mobility of the entire system [63]. The difference of sulfhydryl level obtained from various tested NADESs may be affected by a diverse range of interactions, including hydrogen bonding interactions and ionic interactions. In this study, ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc based NADES may increase diffusivity of sulfhydryls in ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc compared to other observed NADES compositions. However, the mechanism of the NADESs and sulfhydryls interactions needs to be further studied by investigating the thermodynamic characteristics and solubility behavior of the synthesized NADESs in sulfhydryls.

The effect of the water content in NADES based UAE ranged from 39 to 43% for both NADES compositions, ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc. The optimum conditions for ChCl-Gly-based UAE were 41% and 43% for ChCl-Suc-based UAE. The incorporation of water to NADES is crucial for the purpose of reducing viscosity. A certain amount of water can enhance the concentration of the targeted compounds because it reduces the viscosity allowing mass transfer process occurs from the solid sample to the solution [64,65]. However, a too high-water percentage in NADES can also lead to reduction in the extraction yield. This is due to a diminution in the interaction between NADES and the desired compound as well as an increase in polarity [38,39]. It should be highlighted that the impact of increasing the polarity of the NADES (with addition of water) on the effectiveness of extraction is contingent upon the polarity of the specific compounds being targeted [65].

The effect of extraction time on the total sulfhydryl contents was observed by setting various times ranging from 5 to 15 min, according to the previous studies. The optimum extraction time in the UAE using ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc was obtained at 15 and 10 min, respectively. This condition indicates that the secondary metabolite (solute) dissolutions were in equilibrium [66,67].

The liquid-solid ratio effect was evaluated using different ratios, including 3, 5, and 7 mL/g. In this work, the liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g was the optimum condition of both NADES types composition for extracting sulfhydryls.

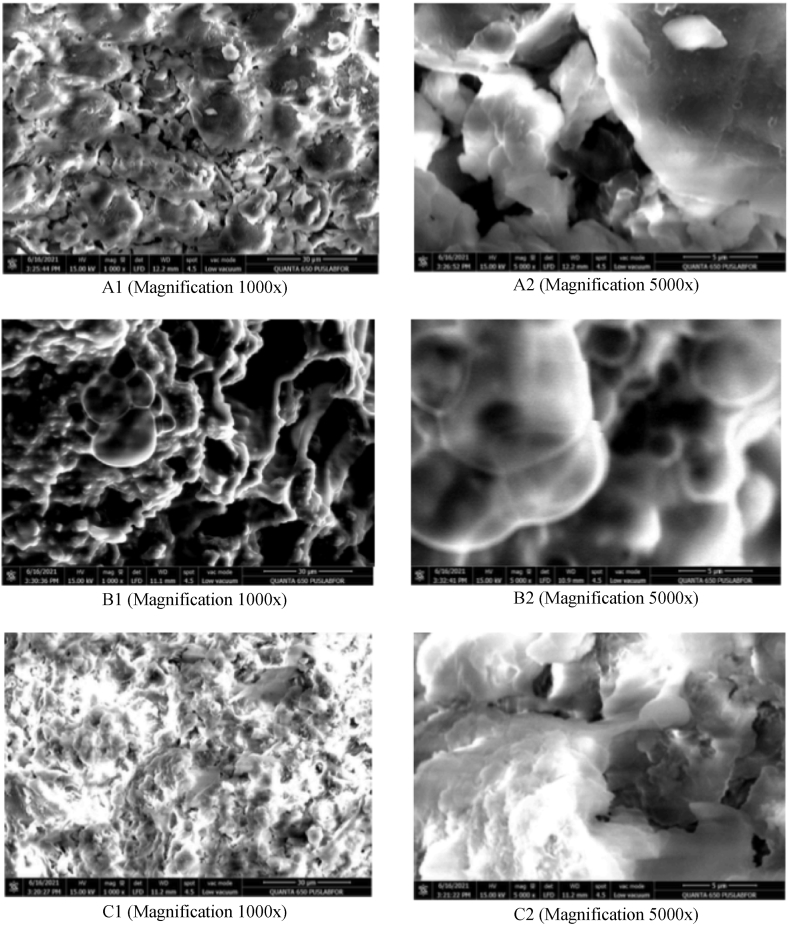

3.3. Surface morphology of L. leucocephala seed powder

To support the correctness of the analysis results between NADES-UAE and 30% ethanol-maceration, surface morphology analysis was performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) on L. leucochepala seed powder both prior to and after to sonication. The aim of conducting the SEM test was to determine the condition of the cell wall in L. leucochepala seed powder before and after the extraction process.

SEM results on the powder before extraction (A) and after extraction by 30% ethanol-maceration (B) and NADES-based UAE (ChCl-Gly) (C) with a magnification of 1000× (1) and 5000× (2) can be seen in Fig. 4. SEM analysis results showed significant differences in the level of damage to the cell wall surface between the samples before and after extraction. Fig. 4B shows the damage to the cell walls compared to before extraction. Interestingly, in the case after extraction using the NADES-based UAE (Fig. 4C), the surface was cracked entirely compared to before (Fig. 4A) and after extraction with 30% ethanol-maceration. The synergistic effect between NADES and UAE is evident in the degree of damage to the surface morphology of the samples. NADES, with the composition of HBD and HBA, allows the breakdown of cellulose within the cell wall sample and facilitates the extraction of target compounds from the cell matrix [49,68].

Fig. 4.

The surface morphology of the dried powder of L. leucocephala seed before treatment (A1 and A2), after extraction with 30% ethanol-maceration (B1 and B2), and after NADES (ChCl-Gly)-based UAE (C1 and C2).

Besides being able to produce better extraction results, the advantage gained from using the UAE method is that it can minimize the amount of solvent used, shorten the extraction time, and require low temperature, making it suitable for withdrawing thermolabile compounds such as sulfhydryl compounds [69,70]. Whereas conventional techniques such as maceration have weaknesses, including the excessive utilization of organic solvents, restricted applicability of extracts due to solvent toxicity, and prolonged extraction time [70,71].

3.4. Mimosine levels from the optimum condition of NADES-based UAE

In this study, apart from determining the levels of sulfhydryl compounds, the levels of mimosine contained in L. leucocephala seeds were also measured. The mimosine contained in L. leucocephala seeds needs to be considered because of its toxic effects [72]. Mimosine compounds belong to the class of pyridine alkaloids [73]. Some studies on animals had proved that mimosine could cause several adverse effects, such as hair loss in ruminants [72], alopecia, anorexia, weight loss, kidney and liver dysfunction, goiter, and death in Alpine goats [74]. In humans, the dose of 32 mg/kg/day of mimosine was toxic [36].

The measurements of mimosine levels were conducted on the extracts derived from the optimized NADES-based UAE condition (ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc) and the 30% ethanol maceration.

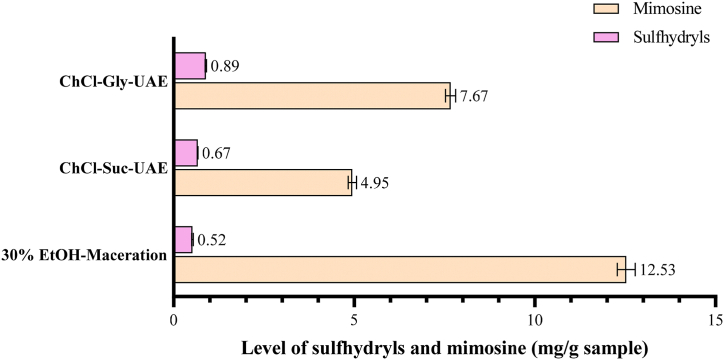

Fig. 5 depicts the total sulfhydryl and mimosine levels obtained from samples extracted with ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc-based UAE in optimized conditions and with 30% ethanol maceration. It is clear from the given chart that the highest level of sulfhydryls was achieved from the UAE method using ChCl-Gly as a solvent with 0.89 mg/g seed powder, followed by ChCl-Suc based UAE with 0.67 mg/g, and the lowest was that of 30% ethanol maceration (0.52 mg/g). On the contrary, the 30% ethanol maceration method generated the highest mimosine level compared to NADES-based UAE.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of sulfhydryl and mimosine contents in L. leucochepala seed powder extracted with different NADES (ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc) based UAE and 30% ethanol-maceration.

In terms of targeted compound extraction, the level of total sulfhydryls is expected to be high, while the presence of mimosine is minimal due to its toxic nature. As shown in Fig. 5, NADES-based UAE in optimum conditions could escalate the levels of total sulfhydryls in the extracts from the ChCl-Gly and ChCly-Suc with values of 0.89 mg/g and 0.67 mg/g samples, respectively. Otherwise, at the same time and conditions, the NADES-based UAE declined the levels of mimosine. The ChCl-Gly-UAE resulted in a 7.67 mg/g sample of mimosine, which was about 61% lower than the 30% ethanol maceration method (12.53 mg/g sample). At the same time, the ChCl-Suc-UAE generated a mimosine level of 4.95 mg/g sample, which was about 40% lower than that of maceration method result. These results suggest that NADES-based UAE used in this study could selectively attract sulfhydryl compounds in the sample matrix compared to the 30% ethanol maceration method. However, further studies should be conducted to optimize other condition factors that affect the UAE, such as the temperature, ultrasonic intensity, duty cycle of irradiation, and HBA and HBD ratio [75].

Interestingly, in the results of the measurement of mimosine levels, 30% ethanol was found to be suitable to attract mimosine in the river tamarind seed. Therefore, using mimosine compounds from L. leucocephala seed, its extraction efficiency can also be increased by involving the UAE method. In addition, the mimosine might not have been optimally attracted because the extraction duration was under the ideal range in the NADES-based UAE. After all, it was only 15 min long. Likewise, the ratio of solvent to powder and the addition of water in NADES had not reached its optimum condition, where only 3 mL/g was used, and 41% water was added. This shows that the optimum conditions for extracting L. leucocephala seeds in terms of the levels of sulfhydryl and mimosine compounds have different extraction conditions. Therefore, if mimosine is expected to be high, further optimization on the extraction method, solvents, and condition factors needs to be carried out.

4. Conclusion

Among six NADES compositions, ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc were selected to be further optimized since both generated higher levels of total sulfhydryl than the other tested compositions. The NADES-UAE method extracted a higher level of sulfhydryls than 30% ethanol-maceration. The optimal UAE conditions for ChCl-Gly were 41% (v/v) of water content in NADES, liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g sample for 15 min of sonication with the total sulfhydryl levels of 0.8915 mg/g, while for ChCl-Suc, it was 43% (v/v) of water content, the liquid-solid ratio of 3 mL/g sample for 10 min with the level of total sulfhydryl of 0.67 mg/g sample. The determination of mimosine from the optimum condition was also conducted, where ChCl-Gly and ChCl-Suc resulted in 7.67 mg/g and 4.95 mg/g, respectively. The SEM image revealed a greater degree of surface morphological destruction in the L. leucocephala seed following NADES-based UAE compared to 30% ethanol-maceration. The study suggested that ChCl-Suc and ChCl-Gly-based UAE were green and effective methods to extract targeted compounds from L. leucocephala seeds.

Author contribution statement

Islamudin Ahmad: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper. Baso Didik Hikmawan; Disqi Fahira Maharani; Nadya Nisrina: Performed the experiment; Analyzed and interpreted the data. Ayun Erwina Arifianti: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. Abdul Mun'im: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by The National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) through Research Collaboration Center (PKR) funding scheme for National Metabolomics Collaborative Research Center with grant number 04/PKR/PPK-DFRI/2022.

References

- 1.Verma S. A Review Study on Leucaena leucocephala : A Multipurpose Tree. 2016;2(2):103–105. doi: 10.1186/1754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowtivannakul P., Srichaikul B., Talubmook C. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of seed extract from Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit. Agriculture and Natural Resources. Sep. 2016;50(5):357–361. doi: 10.1016/j.anres.2016.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.She L.-C., Liu C.-M., Chen C.-T., Li H.-T., Li W.-J., Chen C.-Y. The anti-cancer and anti-metastasis effects of phytochemical constituents from Leucaena leucocephala. Biomed. Res. 2017;28(7):2893–2897. www.biomedres.info [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meena Devi V.N., Ariharan V.N., Nagendra Prasad P. Nutritive value and potential uses of Leucaena leucocephala as biofuel–a mini review. Res. J. Pharmaceut. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2013;4(1):515–521. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suvachittanont W., Kurashima Y., Esumi H., Tsuda M. Formation of thiazolidine-4-carboxyiic acid (thioproline), an effective nitrite-trapping agent in human body, in Parkia speciosa seeds and other edible leguminous seeds in Thailand. Food Chem. 1996;55(4):359–363. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(95)00132-8. Apr. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wardatun S., Harahap Y., Mun’im A., Chany Saputri F., Sutandyo N. Removal of mimosine from leucaena leucocephala (lam.) de Wit seeds to increase their benefits as nutraceuticals. Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research (PSR) 2020;7(3):159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Güngör N., Özyürek M., Gülü K., Eki S.D., Apak R. Comparative evaluation of antioxidant capacities of thiol-based antioxidants measured by different in vitro methods. Talanta. Feb. 2011;83(5):1650–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjørklund G., Crisponi G., Nurchi V.M., Cappai R., Buha Djordjevic A., Aaseth J. A review on coordination properties of thiol-containing chelating agents towards mercury, cadmium, and lead. Molecules. 2019;24(18):3247. doi: 10.3390/molecules24183247. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohan V.R., Tresina P.S., Daffodil E.D. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Elsevier; 2016. Antinutritional factors in legume seeds: characteristics and determination; pp. 211–220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Q.W., Lin L.G., Ye W.C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: A comprehensive review,” Chinese Medicine (United Kingdom) 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s13020-018-0177-x. BioMed Central Ltd., Apr. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Othman N., Manan Z.A., Alwi S.R.W., Sarmidi M.R. A review of extraction technology for carotenoids and vitamin e recovery from palm oil. Journal of Applied Sciences. 2010;10(12):1187–1191. doi: 10.3923/jas.2010.1187.1191. Asian Network for Scientific Information. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi Y.H., et al. Are natural deep eutectic solvents the missing link in understanding cellular metabolism and physiology? Plant Physiol. Aug. 2011;156(4):1701–1705. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.178426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benvenutti L., Zielinski A.A.F., Ferreira S.R.S. Which is the best food emerging solvent: IL, DES or NADES? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019;90:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.06.003. Elsevier Ltd. Aug. 01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mišan A., et al. The perspectives of natural deep eutectic solvents in agri-food sector. 2019;60(15):2564–2592. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1650717. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craveiro R., et al. Properties and thermal behavior of natural deep eutectic solvents. J. Mol. Liq. Mar. 2016;215:534–540. doi: 10.1016/J.MOLLIQ.2016.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro V.I.B., Craveiro R., Silva J.M., Reis R.L., Paiva A., Ana A.R. Natural deep eutectic systems as alternative nontoxic cryoprotective agents. Cryobiology. 2018;83:15–26. doi: 10.1016/J.CRYOBIOL.2018.06.010. Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad I., Hikmawan B.D., Sulistiarini R., Mun’im A. Peperomia pellucida (L.) Kunth herbs: a comprehensive review on phytochemical, pharmacological, extraction engineering development, and economic promising perspectives. J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. Jan. 2023;13(1):1–9. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2023.130201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de los Á. Fernández M., Boiteux J., Espino M., Gomez F.J.V., Silva M.F. Natural deep eutectic solvents-mediated extractions: the way forward for sustainable analytical developments. Anal. Chim. Acta. Dec. 2018;1038:1–10. doi: 10.1016/J.ACA.2018.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takla S.S., Shawky E., Hammoda H.M., Darwish F.A. Green techniques in comparison to conventional ones in the extraction of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: best solvents selection and parameters optimization. J. Chromatogr. A. 2018;1567:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu X., et al. Natural deep eutectic solvent enhanced pulse-ultrasonication assisted extraction as a multi-stability protective and efficient green strategy to extract anthocyanin from blueberry pomace. LWT. Jun. 2021;144 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrochenko A.A., et al. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Extraction of Triterpene Saponins from Aralia elata var. mandshurica (Rupr. & Maxim.) J. Wen,” Molecules. Apr. 2023;28(8):3614. doi: 10.3390/molecules28083614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shikov A.N., Kosman V.M., Flissyuk E.V., Smekhova I.E., Elameen A., Pozharitskaya O.N. Natural deep eutectic solvents for the extraction of phenyletanes and phenylpropanoids of rhodiola rosea L. Molecules. Apr. 2020;25(8):1826. doi: 10.3390/molecules25081826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang G.-Y., et al. Natural deep eutectic solvents for the extraction of bioactive steroidal saponins from dioscoreae nipponicae rhizoma. Molecules. Apr. 2021;26(7):2079. doi: 10.3390/molecules26072079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obluchinskaya E.D., Pozharitskaya O.N., Shevyrin V.A., Kovaleva E.G., Flisyuk E.V., Shikov A.N. Optimization of extraction of phlorotannins from the arctic fucus vesiculosus using natural deep eutectic solvents and their HPLC profiling with tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry. Mar. Drugs. Apr. 2023;21(5):263. doi: 10.3390/md21050263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolae C.-V., Trică B., Doncea S.-M., Marinaș I.C., Oancea F., Constantinescu-Aruxandei D. Priorities of Chemistry for a Sustainable Development-PRIOCHEM. MDPI; Basel Switzerland: Oct. 2019. Evaluation and optimization of polysaccharides and ferulic acid solubility in NADES using surface response methodology; p. 96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen C., et al. Advances in ultrasound assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from cash crops–A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;48:538–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansinhos I., Gonçalves S., Rodríguez-Solana R., Ordóñez-Díaz J.L., Moreno-Rojas J.M., Romano A. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction and natural deep eutectic solvents combination: a green strategy to improve the recovery of phenolic compounds from Lavandula pedunculata subsp. lusitanica (chaytor) franco. Antioxidants. 2021;10(4):582. doi: 10.3390/antiox10040582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakti A.S., Saputri F.C., Mun’im A. Optimization of choline chloride-glycerol based natural deep eutectic solvent for extraction bioactive substances from Cinnamomum burmannii barks and Caesalpinia sappan heartwoods. Heliyon. 2019;5(12) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmad I., Arifianti A.E., Sakti A.S., Saputri F.C., Mun’im A. Simultaneous natural deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasonic-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds of cinnamon bark and sappan wood as a dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor. Molecules. 2020;25(17) doi: 10.3390/molecules25173832. Sep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuniarti E., Saputri F.C., Mun’im A. Application of the natural deep eutectic solvent choline chloridesorbitol to extract chlorogenic acid and caffeine from green coffee beans (Coffea canephora) J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2019;9(3):82–90. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2019.90312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y., et al. Green and efficient extraction of rutin from tartary buckwheat hull by using natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2017;221:1400–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai Y., Row K.H. Application of natural deep eutectic solvents in the extraction of quercetin from vegetables. Molecules. 2019;24:12. doi: 10.3390/molecules24122300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai Y., Rozema E., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Application of natural deep eutectic solvents to the extraction of anthocyanins from Catharanthus roseus with high extractability and stability replacing conventional organic solvents. J. Chromatogr. A. 2016;1434:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai Y., Witkamp G.J., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Natural deep eutectic solvents as a new extraction media for phenolic metabolites in carthamus tinctorius L. Anal. Chem. 2013;85(13):6272–6278. doi: 10.1021/ac400432p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai Y., Witkamp G.J., Verpoorte R., Choi Y.H. Tailoring properties of natural deep eutectic solvents with water to facilitate their applications. Food Chem. 2015;187:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wardatun S., Harahap Y., Mun’im A., Saputri F.C., Sutandyo N. Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit Seeds: a new potential source of sulfhydryl compounds. Phcog. J. 2020;12(2):298–302. doi: 10.5530/pj.2020.12.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad I., Syakfanaya A.M., Azminah A., Saputri F.C., Mun’im A. Optimization of betaine-sorbitol natural deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted extraction and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity of chlorogenic acid and caffeine content from robusta green coffee beans. Heliyon. 2021;7(8) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07702. Aug. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Syakfanaya A.M., Saputri F.C., Munim A. Simultaneously extraction of caffeine and chlorogenic acid from coffea canephora bean using natural deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasonic assisted extraction. Phcog. J. 2019;11(2):267–271. doi: 10.5530/pj.2019.11.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmad I., Syakfanaya A.M., Azminah A., Saputri F.C., Mun’im A. Optimization of betaine-sorbitol natural deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted extraction and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity of chlorogenic acid and caffeine content from robusta green coffee beans. Heliyon. 2021;7(8) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuniarti E., Saputri F.C., Mun’im A. Application of the natural deep eutectic solvent choline chloridesorbitol to extract chlorogenic acid and caffeine from green coffee beans (Coffea canephora) J. Appl. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2019;9(3):82–90. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2019.90312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kontogeorgos N., Roussis I.G. Research Note: total free sulphydryl of seceral white and red wines. South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 2014;35(1):125–127. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellman G.L. Tissue sulphydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan M. InTech; 2012. The Transmission Electron Microscope. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotchabhakdi N., Seanjum C., Kiwfo K., Grudpan K. A simple extract of Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit leaf containing mimosine as a natural color reagent for iron determination. Microchem. J. Mar. 2021;162 doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2020.105860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto H., Sherman G.D. A rapid colorimetric method for the determination of mimosine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1951;33(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(51)90098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilham Z., Hamidon H., Rosji N.A., Ramli N., Osman N. Extraction and quantification of toxic compound mimosine from leucaena leucocephala leaves. Procedia Chem. 2015;16:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.proche.2015.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khademi A., Saatchi M., Mehdi M., Baghaei B. Scanning electron microscopic evaluation of residual smear layer following preparation of curved root canals using hand instrumentation or two engine-driven systema. Iran. Endod. J. 2015;10(4):236–239. doi: 10.7508/iej.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krishnan R.Y., Chandran M.N., Vadivel V., Rajan K.S. Insights on the influence of microwave irradiation on the extraction of flavonoids from Terminalia chebula. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016;170:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2016.06.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad I., Yanuar A., Mulia K., Mun’im A. Application of ionic liquid as a green solvent for polyphenolics content extraction of peperomia pellucida (L) kunth herb. J. Young Pharm. 2017;9(4) doi: 10.5530/jyp.2017.9.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bi W., Tian M., Row K.H. Evaluation of alcohol-based deep eutectic solvent in extraction and determination of flavonoids with response surface methodology optimization. J. Chromatogr. A. Apr. 2013;1285:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oktaviyanti N.D., Kartini, Mun’im A. Application and optimization of ultrasound-assisted deep eutectic solvent for the extraction of new skin-lightning cosmetic materials from Ixora javanica flower. Heliyon. 2019;5(11) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulia K., Fauzia F., Krisanti E.A. Polyalcohols as hydrogen-bonding donors in choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents for extraction of xanthones from the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana L. Molecules. 2019;24(3):636–647. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y., Friesen J.B., McAlpine J.B., Lankin D.C., Chen S.N., Pauli G.F. Natural deep eutectic solvents: properties, applications, and perspectives. J. Nat. Prod. 2018;81(3):679–690. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang L., Li L., Hu H., Wan J., Li P. Natural deep eutectic solvents for simultaneous extraction of multi-bioactive components from jinqi jiangtang preparations. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(1) doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng X., et al. Green extraction of five target phenolic acids from Lonicerae japonicae Flos with deep eutectic solvent. Sep. Purif. Technol. Jan. 2016;157:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2015.10.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yusuf B., et al. Optimizing natural deep eutectic solvent citric acid-glucose based microwave-assisted extraction of total polyphenols content from eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) bulb. Indonesian Journal of Chemistry. 2021;21(4):797–805. doi: 10.22146/ijc.58467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Layne K.L. Methods to determine optimum factor levels for multiple responses in designed experimentation. Qual. Eng. 1995;7(4):649–656. doi: 10.1080/08982119508918813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raissi S., Farsani R.E. Statistical process optimization through multi-response surface methodology. World Acad Sci Eng Technol. 2009;39(3):280–284. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aung T., Kim S.J., Eun J.B. A hybrid RSM-ANN-GA approach on optimisation of extraction conditions for bioactive component-rich laver (Porphyra dentata) extract. Food Chem. 2022;366(Jan) doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demirel C., Kabutey A., Herák D., Sedlaček A., Mizera Č., Dajbych O. Using box–behnken design coupled with response surface methodology for optimizing rapeseed oil expression parameters under heating and freezing conditions. Processes. 2022;10(3) doi: 10.3390/pr10030490. Mar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khuri A.I., Mukhopadhyay S. Response surface methodology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat. 2010;2(2):128–149. doi: 10.1002/wics.73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lobo I.A., Robertson P.A., Villani L., Wilson D.J.D., Robertson E.G. Thiols as hydrogen bond acceptors and donors: spectroscopy of 2-phenylethanethiol complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A. Sep. 2018;122(36):7171–7180. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.8b06649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.D'Agostino C., et al. Molecular and ionic diffusion in aqueous-deep eutectic solvent mixtures: probing inter-molecular interactions using PFG NMR. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17(23):15297–15304. doi: 10.1039/c5cp01493j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Radošević K., et al. Antimicrobial, cytotoxic and antioxidative evaluation of natural deep eutectic solvents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. May 2018;25(14):14188–14196. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1669-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vilková M., Płotka-Wasylka J., Andruch V. The role of water in deep eutectic solvent-base extraction. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;304 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Şahin S., Aybastier Ö., Işik E. Optimisation of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of antioxidant compounds from Artemisia absinthium using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2013;141(2):1361–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aybastier Ö., Işik E., Şahin S., Demir C. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of antioxidant compounds from blackberry leaves using response surface methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013;44:558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patil S.S., Pathak A., Rathod V.K. Optimization and kinetic study of ultrasound assisted deep eutectic solvent based extraction: a greener route for extraction of curcuminoids from Curcuma longa. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70(Jan) doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chemat F., Rombaut N., Sicaire A.G., Meullemiestre A., Fabiano-Tixier A.S., Abert-Vian M. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:540–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Medina-Torres N., Ayora-Talavera T., Espinosa-Andrews H., Sánchez-Contreras A., Pacheco N. Ultrasound assisted extraction for the recovery of phenolic compounds from vegetable sources. Agronomy. 2017;7(3) doi: 10.3390/agronomy7030047. Jul. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.da Porto C., Porretto E., Decorti D. Comparison of ultrasound-assisted extraction with conventional extraction methods of oil and polyphenols from grape (Vitis vinifera L.) seeds. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20(4):1076–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramli N., Jamaludin A.A., Ilham Z. Mimosine toxicity in leucaena biomass: a hurdle impeding maximum use for bioproducts and bioenergy. International Journal of Envirom,emtal Sciences & Natural Resources. 2017;6(5):1–5. doi: 10.19080/IJESNR.2017.07.555700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogita S., Kato M., Watanabe S., Ashihara H. The co-occurrence of two pyridine alkaloids, mimosine and trigonelline, in Leucaena leucocephala. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung - Section C Journal of Biosciences. 2014;69(3–4):124–132. doi: 10.5560/ZNC.2013-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al-Dehneh A., Pierzynowski S.G., Smuts M., Fernandezt J.M. Blood metabolite and regulatory hormone concentrations and response to metabolic challenges during the infusion of mimosine and 2,3-dihydroxypyridine in alpine Goats1r2. Journal of Animal Sciences. 1994;72(2):415–420. doi: 10.2527/1994.722415x. https://academic.oup.com/jas/article-abstract/72/2/415/4719228 [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu Y., Pan S. Effects of various factors of ultrasonic treatment on the extraction yield of all-trans-lycopene from red grapefruit (Citrus paradise Macf.) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20(4):1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/J.ULTSONCH.2013.01.006. Jul. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.