Abstract

Although microbial genomes harbor an abundance of biosynthetic gene clusters, there remain substantial technological gaps that impair the direct correlation of newly discovered gene clusters and their corresponding secondary metabolite products. As an example of one approach designed to minimize or bridge such gaps, we employed hierarchical clustering analysis and principal component analysis (hcapca, whose sole input is MS data) to prioritize 109 marine Micromonospora strains and ultimately identify novel strain WMMB482 as a candidate for in-depth “metabologenomics” analysis following its prioritization. Highlighting the power of current MS-based technologies, not only did hcapca enable the discovery of one new, nonribosomal peptide bearing an incredible diversity of unique functional groups, but metabolomics for WMMB482 unveiled 16 additional congeners via the application of Global Natural Product Social molecular networking (GNPS), herein named ecteinamines A–Q (1–17). The ecteinamines possess an unprecedented skeleton housing a host of uncommon functionalities including a menaquinone pathway-derived 2-naphthoate moiety, 4-methyloxazoline, the first example of a naturally occurring Ψ[CH2NH] “reduced amide”, a methylsulfinyl moiety, and a d-cysteinyl residue that appears to derive from a unique noncanonical epimerase domain. Extensive in silico analysis of the ecteinamine (ect) biosynthetic gene cluster and stable isotope-feeding experiments helped illuminate the novel enzymology driving ecteinamine assembly as well the role of cluster collaborations or “duets” in producing such structurally complex agents. Finally, ecteinamines were found to bind nickel, cobalt, zinc, and copper, suggesting a possible biological role as broad-spectrum metallophores.

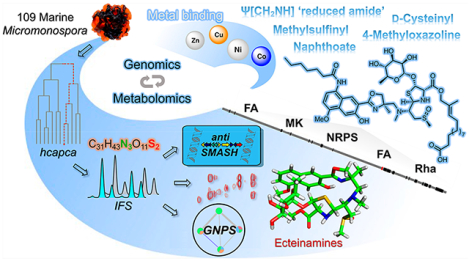

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The last five years have witnessed dramatic advances in “omics” technologies having profound ramifications on chemical biology.1–4 This is perhaps most prominently on display when one considers the study of natural products biosynthesis and drug discovery; particularly striking to consider is the question of how technological advances in mass spectrometry,5 bioinformatics,6 and genomics7 have begun to enable views of new natural products and their means of construction that, hitherto, were all but unimaginable even just 10 or 20 years ago. For instance, van der Hooft and co-workers2 have established the “Paired Omics Data Platform (PoDP)”; this community-driven and supported initiative seeks to identify links between metabolomic and genomic data. The PoDP is a true “grass-roots” initiative in that all data must be in a public database. This discovery platform seeks to identify and document correlations between metabolomic (structural) information and genomic (biosynthetic potential) data; the goal is to identify natural product biosynthetic origins and to correlate these to discrete structural elements (or complete intact structures) of natural products. The duality of genomic and metabolomic data sets underlying this approach renders a paradigm capable of unveiling novel metabolites while, at the same time, giving insight into the biosynthetic machineries driving their construction and presumed structural features. Notably, this approach, like many others before it, is rooted in the idea that any given intact structure discovered likely originates from the cellular execution of one readily accountable BGC, or cluster.8–12

While this remains a completely valid logic, it has become increasingly evident, with improved technologies, that an increasing number of natural products arise by virtue of random enzymatic (encoded by “unclustered genes”) or nonenzymatic chemistries, natural selection processes, and collaborative cluster phenomena.13,14 A number of recently reported natural products (pyronitrins15 and tasikamides16) have showcased the recruitment of various building blocks (or synthons) from different and completely unrelated BGCs (collaborative clusters) contained within a given producer. Yet still, the number of known natural products clearly attributable to collaborative clusters, as opposed to only one, is exceedingly low. This, we posit, is due to technological limitations that have begun to cede to new and/or dramatically refined methodologies. Consistent with this notion, we report here not just a single metabolite resulting from collaborative unclustered genes within the producing microbe, but rather, a whole family of related compounds whose origins invoke the collaboration of unclustered genes.

In contrast to PoDP and other strategies such as metabologenomics,8 many approaches to identifying molecular novelty within large pools of natural products do not take into immediate consideration their biosynthetic origins. Untargeted metabolomics, for instance, typically use LC-MS data sets and seek no immediate correlation to genomics data. Yet, the last several years have seen immense growth in LC-MS-based capabilities.17–19 Our own efforts to mine the metabolomes of marine-derived bacteria for molecular diversity20 inspired the development of automated hierarchical cluster analysis and principal component analysis (hcapca) as a means of analyzing large numbers of LC-MS data sets for microbial strain prioritization and discovery.21,22 Compared to traditional principal component analysis (PCA), hcapca is a powerful tool to analyze large numbers of LC-MS data sets (100s to 1000s). It first groups strains by similarity using hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) followed by PCA analysis on each of the smaller groups. This readily unveils “outliers”, i.e., samples whose chemistries are distinct from consensus features shared by the majority of samples in the overall data set and, in practice, works extremely well to visualize new chemistry. By virtue of its sole dependence upon LC-MS data, hcapca benefits from, but is also limited by, its narrowly defined structural data and perspectives.21 Tandem-MS (MS2) represents one solution to this hcapca limitation. Not at all surprising given the advances in mass spectroscopy and bioinformatics in recent years, new tools such as Global Natural Products Social (GNPS) molecular networking rely on MS2 data sets and molecular fragmentation similarities allowing for spectral alignments to detect similar spectra from structurally related molecules.23

The product, in large part, of a crowd-sourcing initiative, GNPS networking has benefitted from a wide assortment of MS and MS2 data set contributions from an array of laboratories as well as the advent of software packages; all are based on the premise that similar fragmentation data can be used to deduce new molecules with a high degree of precision.

In this paper, we highlight the power and complementarity of hcapca and GNPS alongside genomics to discover a new family of nonribosomal peptides (NRPs) with an unprecedented skeleton from marine Micromonospora sp. WMMB482. As we have found in the recent structural revision of forazoline A, isotopic fine structure (IFS) MS data proved both uniquely illuminating and essential to the discovery.24 Highly significant is that the newly discovered natural products (ecteinamines A–Q, 1–17, Figure 1) do not appear to result from a single BGC but rather invoke an assortment of collaborative yet unclustered genes, as well as varied chemistries.

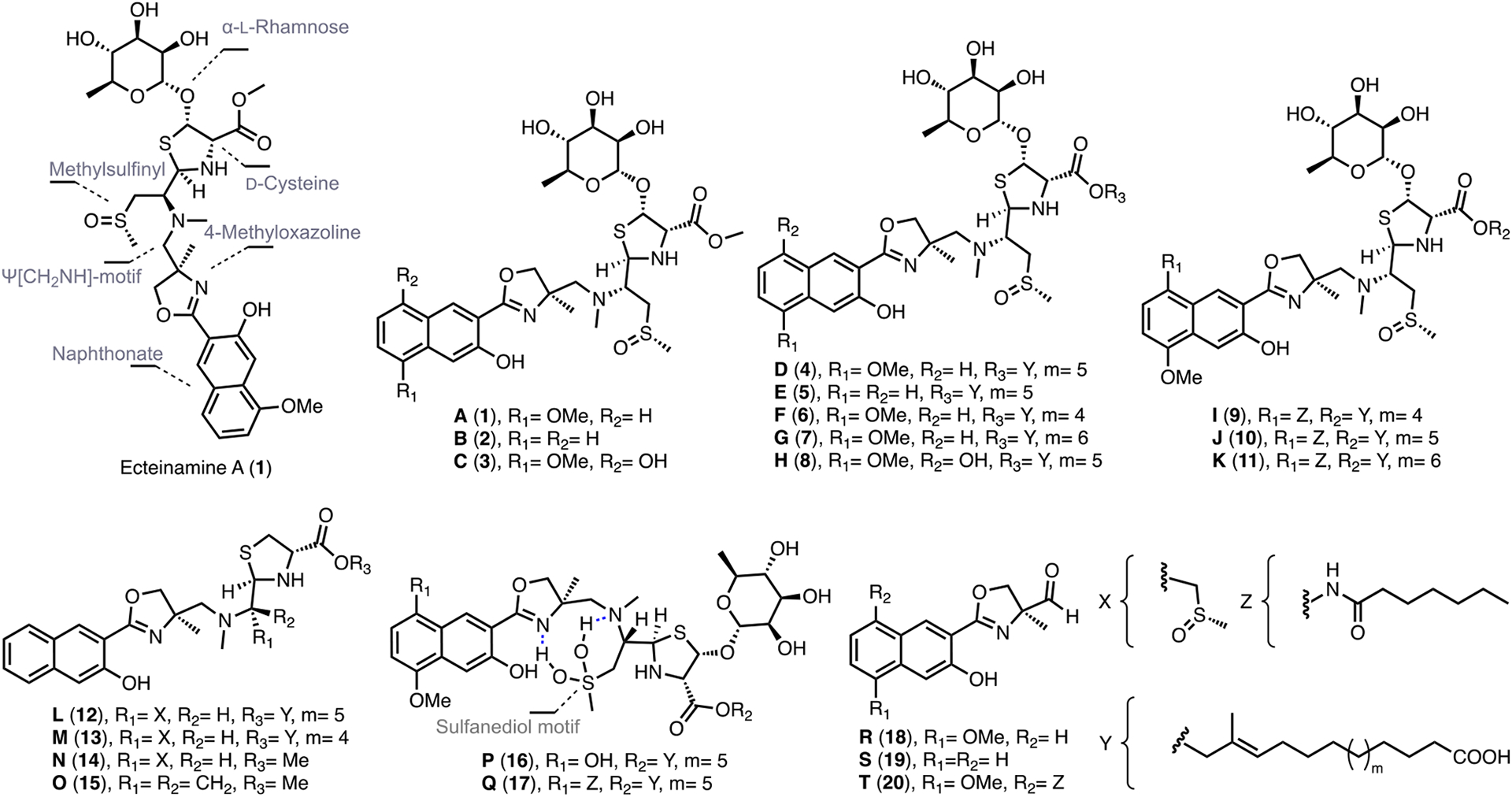

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of ecteinamines A–T (1–20) described in this paper.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Metabolomics and Genomics Analyses of a Large Set of Marine Micromonospora Led to the Discovery of Ecteinamines as Novel NRPs.

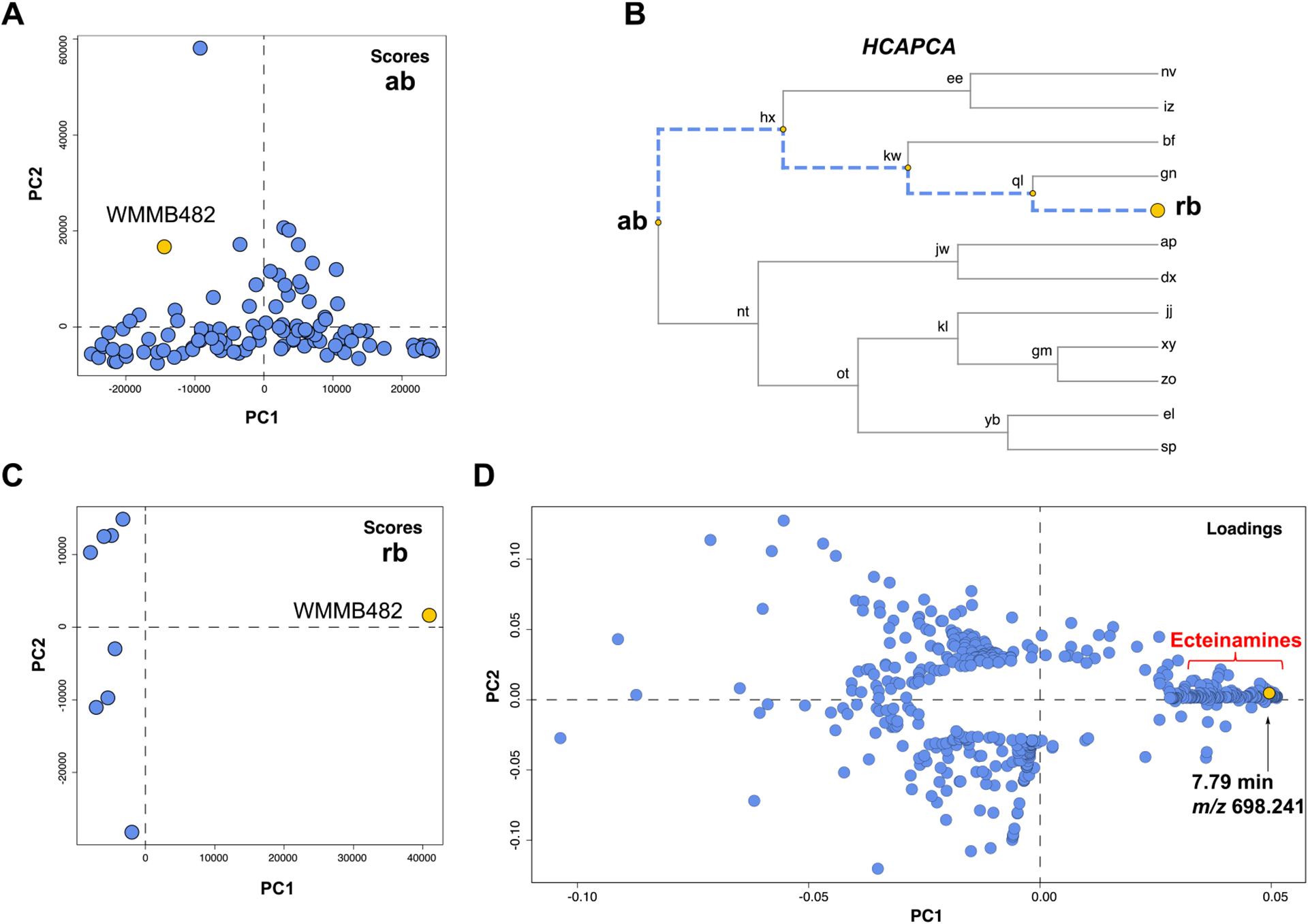

We analyzed a strain library containing 109 marine-derived Micromonospora spp. using hcapca. Initially, the PCA scores plot of all 109 strains (Figure 2A) showed that WMMB482 was not chemically distinct from the other strains. The intragroup variance exceeds the intergroup variance, which is a sign that the model fails to classify. However, after the application of hcapca, the strains were grouped into smaller subsets [represented by leaf nodes in the tree (Figure 2B) and shown in bold letters], and closer examination of node “rb” showed WMMB482 to be chemically distinct from the rest of the data set as evidenced by the scores plot (Figure 2C). Examination of the corresponding loadings plot for strain WMMB482 (Figure 2D) led to the identification of unique metabolites (e.g., the metabolite with m/z 698.241), which were then further pursued.

Figure 2.

Processing of a 109-strain library using hcapca revealed strain WMMB482 to be chemically divergent from the remainder of the data set. (A) PCA scores plot of all 109 strains. (B) Different nodes were generated after the application of hcapca. (C) Scores plot of the subcluster “rb” containing 9 strains with WMMB482 highlighted in yellow. (D) Loadings plot of strain WMMB482. The PCA loading plot showed a series of metabolites produced by WMMB482, including one unique metabolite, ecteinamine A (tR = 7.79 min, m/z 698.241).

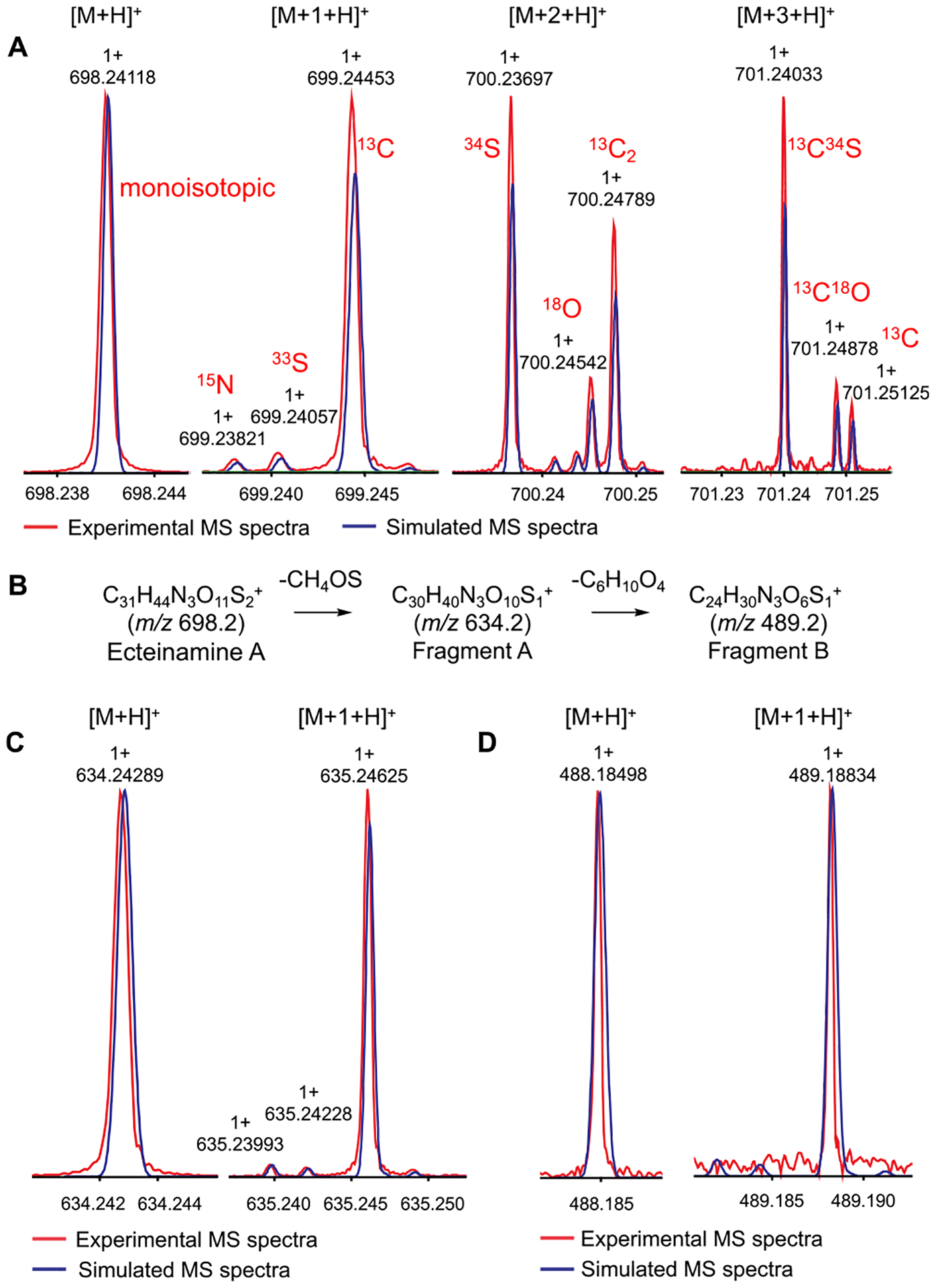

In parallel, IFS analysis was used to unambiguously determine the molecular formula of the metabolite with m/z 698.2412, designated as ecteinamine A. MS data of ecteinamine A was acquired on a Bruker 12T SolariX XRTM MRMS (magnetic resonance mass spectrometry, estimated resolving power 1.5 M at 400 m/z)24 and yielded an intense {[M + H]+, A+} adduct peak, m/z 698.2412. Isotopologues of ecteinamine {[A + 1]+, [A + 2]+, and [A + 3]+ ions} were analyzed to reveal the isotopic fine structures. The simulated IFS for C31H43N3O11S2 matched the acquired MS spectra of all major isotopologues (Figure 3A), confirming the elemental composition. To gain more structural information for ecteinamine A, MS2 and MS3 analyses were performed to investigate the IFS of the fragment ions. Further IFS analysis of the major MS2 fragment (fragment A, m/z = 634.2429, Figure 3C) and major MS3 fragment (fragment B m/z = 488.1850, Figure 3D) revealed a loss of a methylsulfinyl functional group (C1H4O1S1) and an additional sugar unit (C6H10O4), respectively (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Overlaid MS spectra of the experimental (red traces) and simulated (blue traces) IFS. (A) IFS of ecteinamine A {(C31H44N3O11S2)+, [M + H]+} and its isotopologues ([M + 1 + H]+, [M + 2 + H]+, and [M + 3 + H]+) acquired from the Bruker MRMS instrument. (B) Possible ion fragments of ecteinamine A (ESI-MRMS MS2 and ESI-MRMS MS3 of ecteinamine A). (C) Overlaid MS spectra of the experimental (red traces) and simulated (blue traces) IFS of a fragment ion (C30H40N3O10S1+, fragment A of ecteinamine) and its isotopologue {[M + 1 + H]+}. (D) Overlaid MS spectra of the experimental (red traces) and simulated (blue traces) IFS of a fragment ion (C24H30N3O6S1+, fragment B of ecteinamine A) and its isotopologue {[M + 1 + H]+}.

These intriguing aspects of the structure inspired us to sequence the genome of Micromonospora sp. WMMB482 using PacBio technology; analysis was carried out using DIA-MOND25 and antiSMASH (version 5.1.2) software.26 We searched for a BGC that was consistent with the nitrogen and sulfur atoms in ecteinamine A. Thus, we focused on BGCs for NRPs, NRP-PK (polyketide) hybrids, and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (Ripps). Of the 22 gene clusters identified in the WMMB482 genome (Figure S19), two immediately stood out as viable candidates for ecteinamine production. These clusters, tentatively termed ect-ked (BGC at location 5,035,057–5,145,459) and ect-coe (BGC at location 6,321,226–6,377,021), were most similar to the clusters associated with biosynthesis of the enediyne-based DNA-damaging agent kedarcidin (ked)27 and coelibactin (coe),28 respectively. Notably, ect-ked and ect-coe were predicted to incorporate two and three cysteines, respectively, a realization that, upon IFS analysis of 1, led us to assign the tentative ect-ked cluster as the more aptly termed ect cluster. IFS data for 1 clearly indicated the presence of two sulfur atoms, most likely originating from cysteine.

Further in silico analyses enabled comparisons between the methyltransferase (MT) domain/glycosyltransferase found within the ect cluster and the methylsulfinyl/sugar functionalities within 1 as determined by metabolomics. Also, in considering the methylsulfinyl group of ecteinamine A and its assigned BGC, we scrutinized the heterocyclic possibilities offered by the C-domains in all three NRPS genes; this entailed their alignment and examination/searching for the conserved DXXXXD cyclization motif (Figure S75).29 To our surprise, across all three systems, the cyclization motif was found to be conserved and fully intact, suggesting the fidelity of their putative biosynthetic functions as encoded within the ect cluster. This finding refuted the idea that the methylsulfinyl group in 1 originates from a free thiol. In sum, in-depth metabolomic and genomic analyses indicated that ecteinamine A is heavily modified by enzymes whose genes reside beyond the ect cluster and are thus unclustered. Importantly, these unclustered genes within WMMB482 enable a seemingly simple cluster to produce a highly functionalized molecule with a unique backbone.

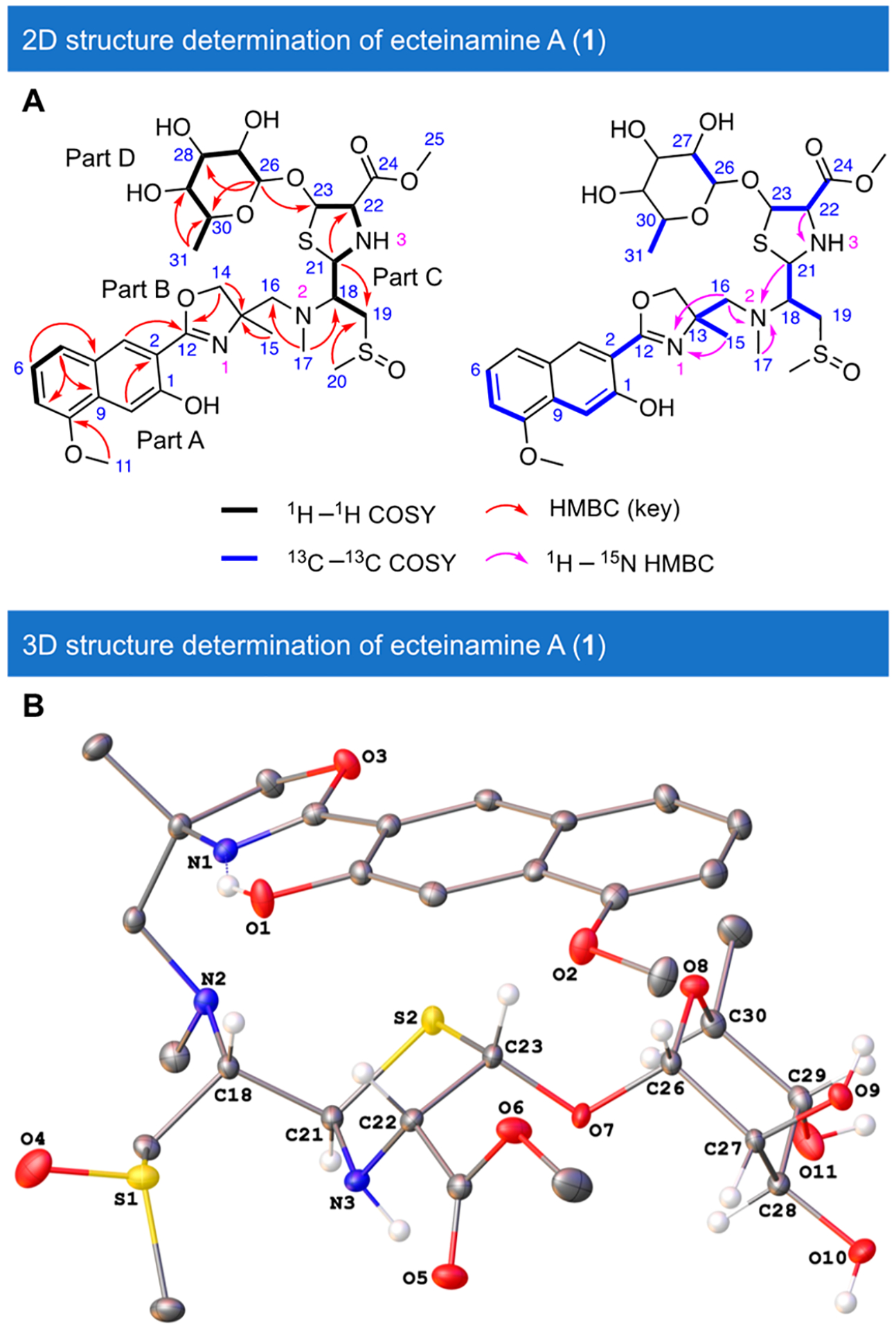

Given the perceived disconnect between the ect cluster and preliminary structural information, we pursued de novo structure determination. We analyzed 1D and 2D NMR data to establish the planar structure of 1. The highly unusual structural features required an array of spectroscopic approaches to establish its structure. An isotopic enrichment strategy30 using uniformly labeled 13C glucose and 15NH4Cl in fermentations figured prominently in these efforts and is described in the Supporting Information (SI). Acquisition of 13C–13C gCOSY and 15N HMBC spectra and detailed analysis of the correlations [details in SI, Section 4.2] supported the structure of 1 (Figure 4A). Efforts to grow crystals of 1 yielded, from a 7:3 MeOH–H2O system, crystals that proved highly amenable to crystallographic analyses.

Figure 4.

Structure determination of ecteinamine A (1). (A) 1H1H COSY, key HMBC, ROESY, 13C–13C COSY, and 1H–15N HMBC correlations for ecteinamine A (1). (B) X-ray crystal structure of ecteinamine A (1) illustrating its absolute configuration.

Hence, X-ray crystallography using Mo Kα radiation (details in the SI, Sections 2.4 and 4.3) not only validated earlier structural hypotheses rooted in NMR spectroscopy but also revealed the absolute configuration of 1 to be 13R,18S,21R,22S,23S,26S,27R,28R,29R,30S as shown in Figure 4B [Flack parameter = 0.00(2), CCDC 2090757]. Notably, the S-1 of the methylsulfinyl moiety was determined to be of the S configuration.

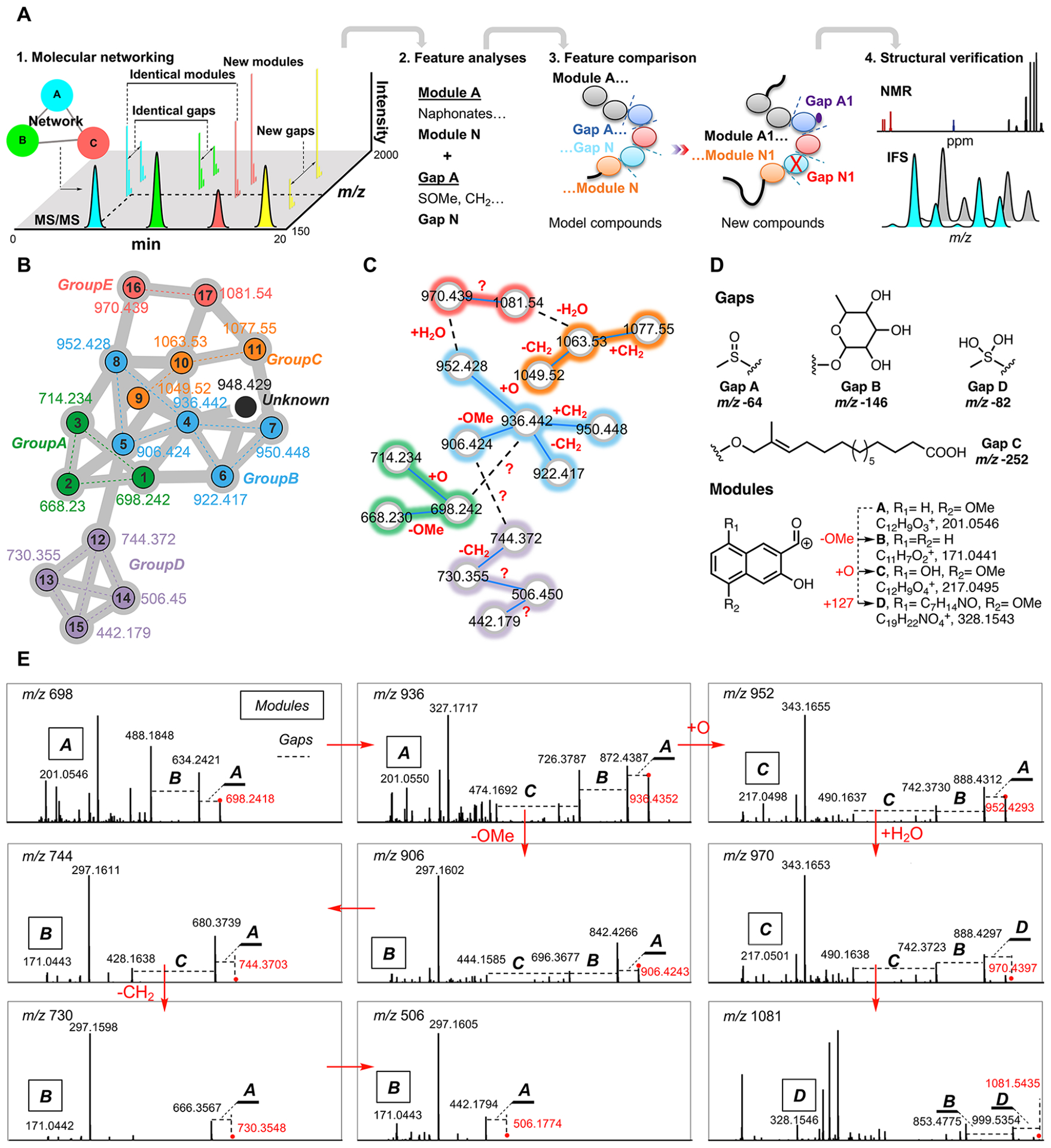

Having rigorously elucidated the structure of ecteinamine A, we next employed molecular networking as a part of the Global Natural Products Social molecular networking (GNPS) web platform23 (Figure 5) to search for possible ecteinamine analogs and biosynthetic precursors from the crude extract of strain WMMB482 (details in the SI, Section 4.3). The logic at this juncture was that such discoveries might shed light on the biosynthetic machineries responsible for 1. Using GNPS (Figures 5 and S14), we identified 18 analogs in the crude extract. More detailed metabolomics analyses (IFS and/or MS/MS) of all ions inspired us to propose the chemical structures of a majority of new ecteinamine congeners (17 out of 18, ecteinamines A–Q, 1–17) (Figure 5B), three shunt products, ecteinamines R–T (18–20, Figure 1), and three biosynthetic precursors, ecteinols A–C (21–23, Figure 7). The structures of three of these [ecteinamines B (2), D (4), and I (9)] were further verified by 2D NMR (Figure S24). Although we were unable to obtain crystals of other ecteinamines suitable for crystallographic study, the common biosynthetic origins and similarity of NMR data sets to those of 1 suggest that other ecteinamines possess the same absolute configuration as 1.

Figure 5.

Metabolomics-based ecteinamine analog discovery. (A) Logic and rationale behind new analog identification based on metabolomics data. Detailed analyses of chemical features obtained from metabolomics enabled the structural elucidation of most ecteinamine family members. (B) Close-up view of molecular networking analysis of ecteinamines in the crude extract of strain WMMB482. In general, two compounds are related if they are connected within the network. A total of 18 ecteinamines were observed, 17 of which were characterized. The determined analogs were grouped and colored in accordance with their structures. (C) Molecular networking analysis elucidated common chemical features. (D) List of structural features (gaps and modules) used for structural elucidation. (E) Detailed MS/MS analysis for structural elucidation of cryptic analogs.

Figure 7.

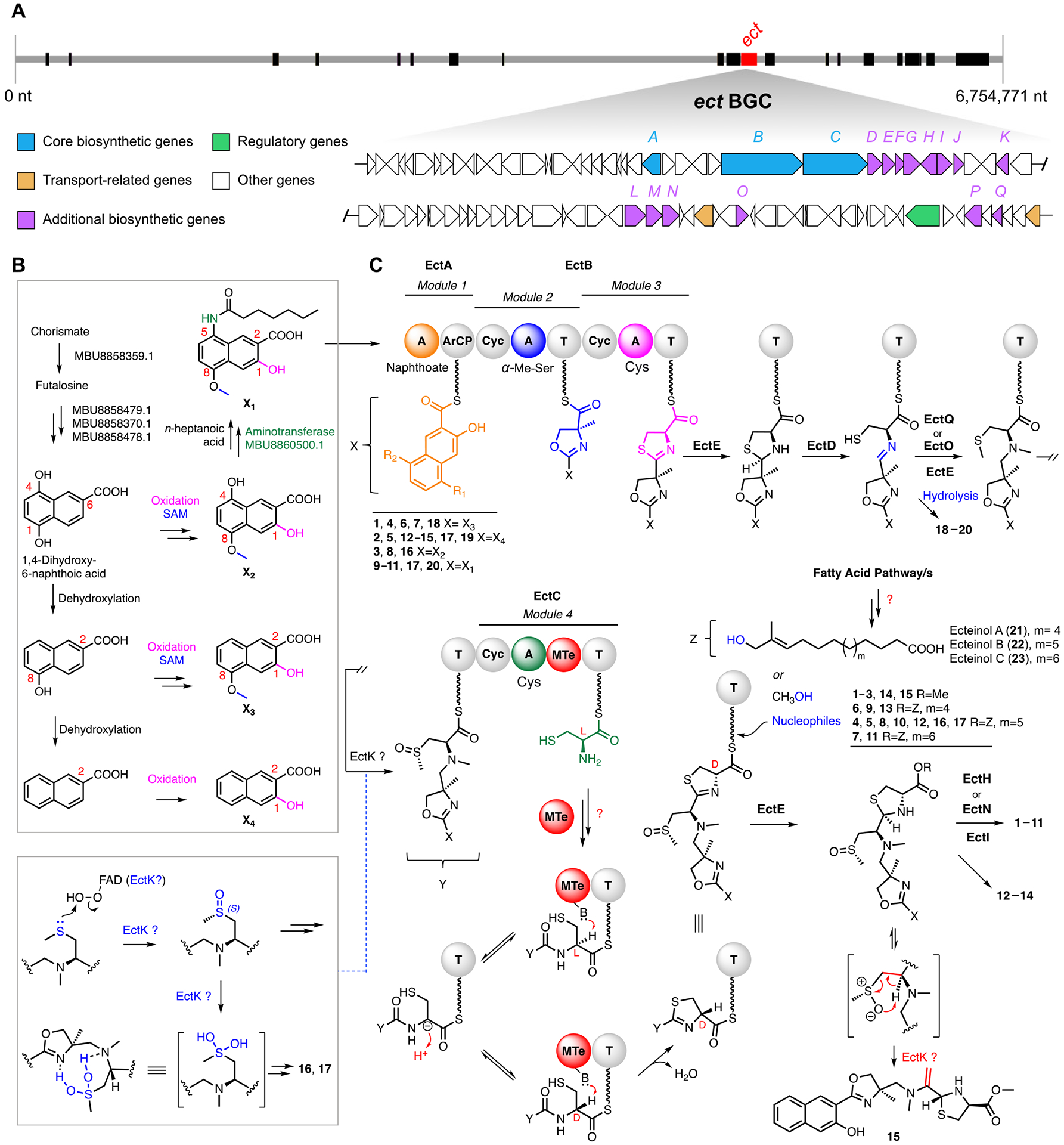

Proposed biosynthetic pathway for ecteinamines. A complete listing of clusters/genes and their putative roles/functions is available in the SI, Section 8. (A) Overview of the ecteinamine biosynthetic gene cluster (ect) within the Micromonospora sp. WMMB482 genome; the ect cluster highlighted is one of more than 20 clusters identified within the WMMB482 genome. Tentative functional annotations for ect genes and their relative organization are indicated by color as shown. Genes colored in white are not proposed to be involved directly in biosynthesis. Black bars represent other unrelated BGCs. (B) Proposed biosynthetic pathway to relevant 2-naphthoic acid moieties. (C) Biosynthesis of the ecteinamine NRPS scaffold. A, adenylation domain; ArCP, aryl carrier protein; Cyc, cyclization domain; T, thioesterase. The MTe domain in module 4 is an MT-like domain postulated to catalyze epimerization of the α-carbon in the cysteinyl thioester. Note that ecteinols A–C (panel C, 21–23) serve as key structural elements for 4–13, 16, and 17 (Figure 1).

Structural Novelty Analysis of Ecteinamines.

Having unambiguously elucidated the structures of ecteinamines, we next carried out a comprehensive structure search, complementary to early MS-based dereplication efforts. The ecteinamines proved to be highly unique and unusual in the context of Scifinder (ecteinamine A, similarity <70%, Figure S66). Ecteinamines are characterized by an NRPS-derived core scaffold; unique features are, however, projected from, and embedded within, this NRP core. Uncommon functionalities displayed by ecteinamines within the NRP skeleton include a 2-naphthoate moiety, 4-methyloxazoline, a Ψ[CH2NH] “reduced amide” moiety, and a methylsulfinyl moiety. Although slightly different in the substitution patterns, napthoates, in the context of secondary metabolism, were first noted in the enediynes kedarcidin and neocarzinostatin31 (Figure S67) and have been noted more recently in the karamomycins,32 which are interesting 2-naphthalen-2-yl-thiazolines identified from Nomomuraea endophytica. The 4-methyloxazoline moieties found in ecteinamines are rare, but recent reports have unveiled several examples of natural products containing this moiety (Figures S69).33–36,8 Additionally, the ecteinamines represent the first natural products in which the Ψ[CH2NH] “reduced amide” has been found. Although commonly encountered and exploited in synthetic compounds, serving as a peptide bond isostere,37 this well-documented group has been elusive in natural products. At the same time, the presence of the methylsulfinyl functionality in marine natural products is unusual; one of the most well-established examples is the methylsulfinyl moiety found in neopetrosiamides, tricyclic peptides from the marine sponge Neopetrosia sp.38 (Figure S67). The ecteinamine case represents an interesting scenario wherein the methylsulfinyl moiety is present in the majority of family members; its absence likely signals a biosynthetic dead end. For instance, compounds 12–15 all bear a strikingly truncated backbone, and three of the four display a pendant sugar moiety. Only compound 15 lacks this sugar and, coincidentally, also is devoid of the methylsulfinyl group. It is easy to envision that 15 might result from a cis elimination event involving the methylsulfinyl.39 One of the most interesting features identified within the ecteinamine family is the sulfanediol characteristic of compounds 16 and 17. To our knowledge, this is the first time that such a species has been observed within the context of a biosynthetic pathway.40 We envision that the methyl sulfoxide moiety of 1, or a related precursor, undergoes oxidation and that this species is stabilized by a network of two intramolecular H-bonds between the nearby oxazoline and Ψ[CH2NH] moieties, respectively.41

Biosynthesis of the Ecteinamine 2-Naphthoic Acid Moiety.

The prospect, as suggested by the numerous unique and rare functional groups contained in ecteinamines, that understanding ecteinamine biosynthesis could unveil new enzymatic machineries inspired a genomics study of WMMB482. In silico analysis of the WMMB482 genome demonstrated that the peptide backbone is encoded by two NRPS open reading frames (ORFs) that encode three modules. Functional assignments of other individual ORFs were made by comparison of the deduced gene products with proteins of known or predicted functions in the database as summarized in Table S18.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the ecteinamine family is that the biosynthesis of the 2-naphthoic acid moiety found in ecteinamines and other natural products, such as kedarcidin and karamomycins, has very little literature precedent. After evaluating possible sources of the naphthoate; the menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthetic pathway proved especially attractive. Two menaquinone biosynthetic pathways are known, and each entails the conversion of chorismate to menaquinone by eight, or four, enzymes, respectively [(MenA to MenH in E. coli) and (MqnA to MqnD in Streptomyces sp.)].42–46 Chorismate and its biosynthetic products are ubiquitous in both primary and secondary metabolic pathways. As such, it is possible that some degree of metabolite drift or recruitment across pathways may be operative in ecteinamine construction. Bioinformatics analysis of the WMMB482 genome revealed the presence of putative homologues for all four mqn-encoded enzymes (for detailed functional annotations of four genes for chorismate processing see Table S18, Figures 7B and S71). We thus propose that the 2-naphthoate motif of the ecteinamines likely arises as a shunt product in the conversion of chorismate to menaquinone. Once generated, 1,4-dihydroxy-6-naphthoic acid undergoes conversion to the precursors of the ecteinamines (Figures 7B and S72). The ectA A-domain displayed the greatest protein similarity to AFV52184.1 (kedU28) from the kedarcidin cluster.27 Both its location and similarity to KedU28 strongly suggest that EctA loads all naphthoates onto the first aryl carrier protein (ArCP) of the NRPS machinery (Figure 7C).

Biosynthesis of the Ecteinamine 4-Methyloxazoline Moiety.

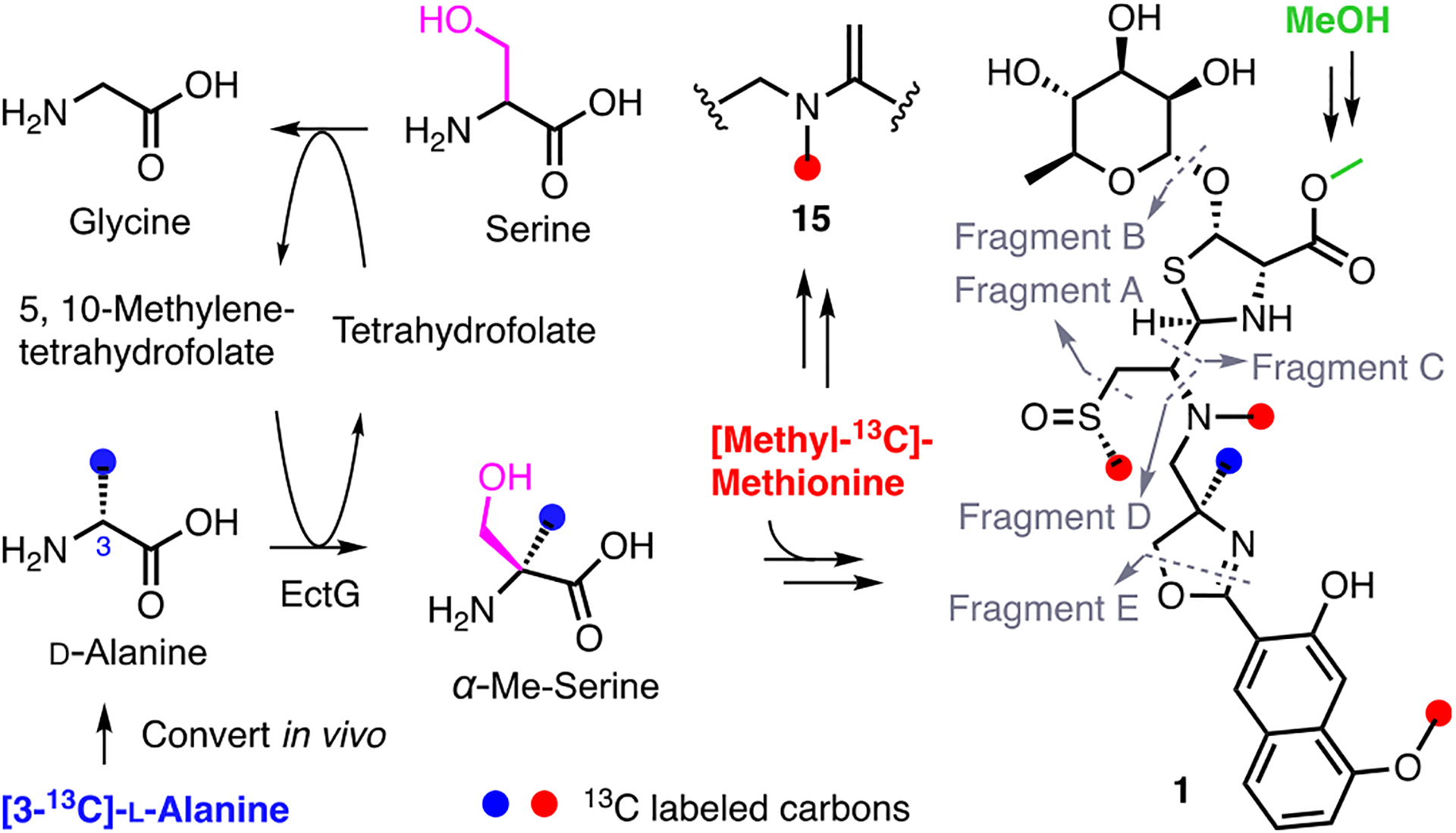

The first ectB A-domain (module 2, Figure 7) in the NRPS machinery compares well with known A-domains as determined using MIBiG2.47 The active-site residues of the ectB A-domain in module 2 suggest activation of Thr (Table S4), though a novel α-Me-l-Ser is incorporated based on the structures of ecteinamines. The installation of the NRPS embedded cyclization domain (Cyc) might then catalyze 4-methyloxazoline formation (Figure S75).48 It was not clear at this stage whether α-Me-l-Ser was installed by the NRPS or if it was generated by methylation of l-Ser following its integration via typical peptide elongation chemistry; either scenario seemed feasible leading up to methyloxazoline ring formation. We initially expected that the methyl group of the 4-methyloxazoline ring could be installed by an S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase since related methylthiazoline systems in thiazostatin and watasemycin49 are thought to result from cysteine methylation by an NRPS embedded SAM-dependent MT domain (Figure S74). However, extensive bioinformatic analysis revealed the presence of EctG, a glycine/serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) homologue (FmoH for JBIR analogs,36 protein identity 53.7%; AmiS for amicetin,50 protein identity 50.2%; TbrU for tambromycin,8 protein identity 50.9%, Figure S74C). We theorized that this SHMT might generate the key intermediate α-Me-l-Ser from d-alanine prior to NRPS-mediated installation.

In light of concerns surrounding ecteinamine methylation pathways we carried out isotopic incorporation studies (details in the SI, Section 9). The independent, yet comparative applications of 13C-labeled precursor molecules, [3-13C]-d-Ala and/or [methyl-13C]-methionine, proved highly informative. MS/MS data generated for fermentations supplemented with either isotopic methyl source revealed that the direct incorporation of 13C into the 4-methyloxazoline was achieved only by feeding [3-13C]-l-Ala. Comparisons of fragments D and E made this clear. Notably, fragment D showed an isotopic pattern consistent with the incorporation of one 13C atom; in contrast, no 13C was incorporated into fragment E (Figures 6 and S80). Moreover, the N-methyl on the “reduced amide” was determined to be SAM-derived as evidenced by [methyl-13C]methionine incorporation of 15 (Figures 6 and S80). These findings suggest that [3-13C]-l-Ala undergoes epimerization to [3-13C]-d-Ala and that the 3-methyl group is then incorporated into the 4-methyloxazoline moiety of the ecteinamines. In addition to the findings above, MS/MS analyses of extracts generated using media supplemented with [methyl-13C]-methionine revealed isotopic enrichments at the methylsulfinyl (Me-20) and OMe (Me-11) of each naphthoate ring (Figure 6). Not surprisingly, the carboxymethyl group (C25) was found to not derive from SAM since no isotopic enrichment was found at C25. This supports the idea of methanolysis, as a key step en route to biosynthesis of 1. To verify that the C25 methyl group undergoes biosynthetic installation and is not the result of extractions and chemical procedures, we repeated these experiments using acetonitrile as the extraction solvent rather than MeOH. Analyses of the LC-MS spectra (Figures S54 and S80) again revealed the presence of 1 despite the complete absence of MeOH during the course of extractions. Ultimately, the carboxymethyl group characteristic of the ecteinamines (1–3, 14) was definitively attributed a biosynthetic origin.

Figure 6.

Overview of methyl group incorporation into 1 and 15 based on isotopic enrichment studies.

Biosynthesis of the Ecteinamine NRPS Scaffold.

The biosynthetic origins of the ecteinamines became evident very early on by virtue of their NRP-like backbones; especially telling was the extent of their heterocyclic features and approximate spacing of heteroatoms. Unlike other common cysteine-containing NRPS-derived metallophores, such as yersiniabactin,51 the ecteinamines contain a novel Ψ[CH2NH] reduced amide bond in the C/N-seco thiazolidine skeleton. As described above, cyclization motifs of all three modules are conserved and fully intact, indicating high fidelity for cyclization chemistries within the ect cluster. One gene in particular (ectE) was predicted, on the basis of comparisons to work previously carried out on thiazostatin,49 to generate a reductase able to convert a thiazoline to the corresponding thiazolidine. Accordingly, we envision that EctE carries out the same transformation en route to the ecteinamines. Deoxygenation of the requisite amide necessary to install the Ψ[CH2NH] moiety likely proceeds via cysteine linkage and cyclization to the thiazoline. EctE-mediated reduction to the thiazolidine49 (Figure S76) and subsequent C–S lysis (enzymatic or spontaneous) are envisioned to afford an imine intermediate; related biosynthetic chemistries are known. Importantly, efforts to identify this putative imine intermediate and/or related products (hydrolyzed amines and aldehydes) made clear the presence of ecteinamine aldehydes 18–20 (Figures S76, S339–S341). This finding underscores the importance of current day metabolomics capabilities; the ability to visualize 18–20 using metabolomics helps to validate our proposed biosynthetic pathway.

Once formed, we envision that the ring-opened thiazolidine serves as a substrate for an N- and/or S-methyltransferase. Very interestingly, the absence of any clear MT domains in ectB suggests that a stand-alone methyltransferase (putatively EctQ or EctO) likely performs two NRPS-anchored methylation events: one en route to the methyl sulfoxide moiety and the other at the Ψ[CH2NH] amino group. Relatedly, that all ecteinamines characterized to date harbor S-chirality at the sulfoxides, rather than epimeric mixtures, suggests that most, if not all, S-oxidations en route to the ecteinamines are carried out enzymatically.52 This idea was supported by carefully executed control experiments using LC-MS analysis of freshly collected fermentation broths, which revealed that none of the ecteinamines identified here are formed during chemical workups (details in the SI, Section 8.4). The identification of exomethylene 15 also supports potential enzyme involvement when it comes to sulfur modifications during ecteinamine assembly. Particularly intriguing is the prospect for sulfoxide syn elimination via a five-membered cyclic transition state. A closely related transformation involved in synerazol biosynthesis has been assigned to the bifunctional methyltransferase/FAD-dependent monooxygenase PsoF.53 En route to synerazol, PsoF has been proposed to convert a sulfide to the corresponding sulfoxide and then also catalyze a syn elimination of the newly generated sulfoxide. There are four FAD-dependent monooxygenase analogs within the ect cluster (EctK, EctL, EctM, EctP); one or more of these likely catalyze S-oxidation and/or sulfoxide elimination in ecteinamine biosynthesis (Figure 7C).

Crystallographic analysis of 1 made clear that the final cysteine added during NRPS-catalyzed assembly bears non-natural d-stereochemistry. Comprehensive bioinformatic analyses failed to unveil any reasonable stand-alone epimerase candidates (details in the SI, Section 8.5). This finding, combined with the proximity of an MTe-like domain found in EctC, suggests that cysteine epimerization prior to NRP incorporation may be carried out by the MTe-like domain of EctC. A similar scenario has been previously reported in pyochelin biosynthesis.54 Following cysteine incorporation to the growing chain and presumed subsequent cyclization and epimerization, we then envision that reduction of the d-configured thiazoline affords the saturated thiazolidine. The genomics of the ect cluster, structures elucidated for ecteinamines, and functionally similar enzymes associated with thiazoline reduction chemistry all suggest that EctE carries out thiazoline reduction.

Biosynthetic completion of the ecteinamines occurs following thiazoline reduction and scaffold release from the NRPS machinery. Although we cannot rule out other enzymatic contributions (details in the SI, Section 8.6), the absence of a thioesterase domain invokes alternative release mechanisms; one of these entails hydrolytic or alcoholysis pathways likely involving methanol and long chain fatty alcohols in this case. This has been observed in the biosynthesis of bovienimides,55 NRPs from the entomopathogenic bacterium Xenorhabdus bovienii. Perhaps noteworthy is that, despite extensive data set searching, we have never been able to detect C-terminal free acid variants of ecteinamine; we hypothesize that either the observed ecteinamines are extremely stable, their acid forms (if generated) are unstable, or the acid forms are present in vanishingly small quantities that elude detection. Finally, subsequent tailoring chemistries by EctH or EctN (oxidation at C23) and EctI (C23 glycosylation with α-l-rhamnose) enabled the formation of chemically divergent ecteinamines. Notably with respect to the availability of rhamnose, the genes needed for rhamnose production are unclustered and are found embedded within a predicted saccharide region (Figure S79). In addition, the discovery of unglycosylated ecteinamine analogs 12–15 suggests that thiazolidine glycosylation represents one of the final steps in ecteinamine family member biosynthesis.

Metal-Binding Ability of Ecteinamines.

The combination of the 2-naphthoic acid and methyloxazoline seen in ecteinamines represents an unprecedented scaffold but also hints at a putative function for these compounds in their producing organism’s natural habitat. Many reported oxazolyl-phenols, usually 2-hydroxybenzoyl-oxazoline groups, as found in amychelin56 and attinimicin,57 are known to possess siderophore properties. This ring system is an established metal-binding moiety; although preferentially associated with iron chelation, other metals such as zinc and copper are candidates for chelation as well.58,59 Accordingly, we theorize, based on their structures, the ecteinamines may play important roles as metal-sequestering agents enabling WMMB482 survival in the metal-deficient marine environment. Ecteinamine’s unique set of functional groups and their arrangement suggest that these compounds are capable of metal chelation. Indeed, a large number of marine-derived natural products serve as siderophores and/or metallophores.60 Thus, we examined the prospect that ecteinamines may serve as ligands for various metals. Specifically, chrome azurol S (CAS) assay results (Figure S55) along with an iron regulation assay (Figure S56) indicated that WMMB482 did not synthesize ecteinamines in response to iron limitation; this suggested that ecteinamines are not genuine siderophores.

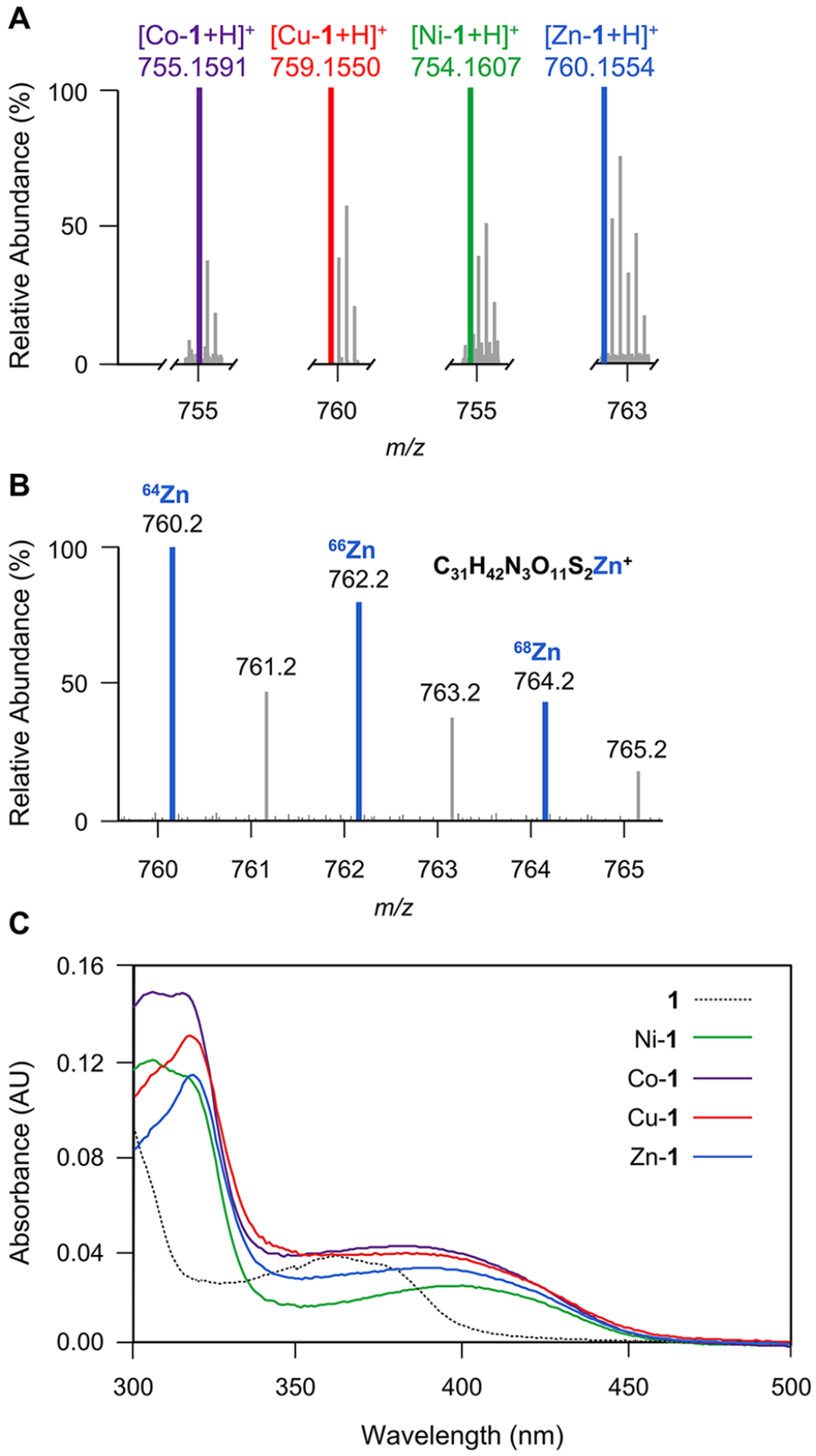

We then evaluated the solution-phase metal-binding activity of ecteinamines using metabolomics to determine metal–ligand stoichiometries with different metals. To start, we tracked the ability of 1 to form assorted metal complexes with cobalt, nickel, zinc, and copper using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) as the means of detection. Direct infusion of assorted complexes enabled the observation of all four metal complexes (Figure 8A). The isotopic patterns characteristic of each metal observed in ESI-MS allowed us to identify each discrete metal–ligand complex (Figures S62–S65). For instance, the MS of a zinc complex with pseudomolecular ion peaks at m/z 760.2, 762.2, and 764.2 was consistent with the presence of a 1–Zn2+ monomeric complex (Figures 8B and S63). Ecteinamine A and metal complex solutions were then subjected to UV/vis measurement. In addition to the absorption at λ = 366 nm for 1, copper-1, nickel-1, zinc-1, and cobalt-1 showed an absorption maximum at 386, 400, 390, and 381 nm, respectively (Figures 8C and S57–S61). These data strongly support the notion that ecteinamines are broad-spectrum metallophores. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the amphiphilic properties of ecteinamines (lipids on the ester and sugar in the peptidic core) enable the efficient uptake of metals.61 In considering what is known about other membrane receptor-mediated metal uptake systems, it seems likely that the lipophilic fatty acid tails in the ecteinamines anchor them to the outside of the cell, thus enabling metal collection from the extracellular milieu. Projection of the hydrophilic iron-binding headgroup (sugar-associated) into the extracellular marine environment likely enables facile metal collection and is not unlike a microscopic form of metal fishing net.

Figure 8.

Determination of ecteinamines as broad-spectrum metallophores. (A) Mass spectra of metal-chelating 1 complexes. [Co-1 + H]+, m/zcalcd 755.1587; [Cu-1 + H]+, m/zcalcd 759.1551; [Ni-1 + H]+, m/zcalcd 754.1609; [Zn-1 + H]+, m/zcalcd 760.1547. (B) Close-up view of the mass spectrum for Zn-1. {[1-64Zn + H]+, m/z 760.1554, calcd for C31H42N3O11S264Zn, 760.1547} with pseudomolecular ion peaks at m/z 760.2, 762.2, and 764.2 showing 1 bound to zinc isotopes with masses of 64, 66, and 68, respectively. The empirical molecular formula was deduced from exact mass. (C) UV/vis spectra of 1, Ni-1, Co-1, Cu-1, and Zn-1 complexes. In addition to the absorption at λ = 366 nm for 1, Ni-1, Co-1, Cu-1, and Zn-1 complexes showed maximum absorptions at 400, 381, 386, and 390 nm, respectively.

CONCLUSION

The discovery of a new class of NRPS-based natural products from a panel of 109 marine Micromonospora strains highlights the power and complementarity of modern-day omics technologies, especially hcapca and GNPS networking. The ecteinamines, characterized by a generally conserved and consistent NRP backbone, display a wide assortment of different ancillary groups which appear to call upon the extensive recruitment of enzymatic machineries encoded for well beyond the core ect BGC. In particular, the machinery responsible for naphthoate construction, represented as the mqn cluster, represents an ect cluster collaborator to establish the core ecteinamine scaffold. Of the 20 new compounds identified, 17 contain an intact backbone derived from mqn and ect cluster collaboration; the remaining three contain all but the thiazoline component (and associated appendages) found in the other 17. Interestingly, the ecteinamine family displays a wide array of structural variability among its members; these nuances from one ecteinamine to the other appear to be dictated by an array of enzymes encoded throughout the ~7,000,000 bp genome of strain WMMB482. That we have been able to discover and characterize the overwhelming majority of these compounds is a testament to the integration and refinement of new omics technologies that enable views into microbial metabolomics and genomics that were once inconceivable. These findings are rounded out by rigorous genomics studies and isotopic incorporation initiatives to better understand some of the key enzymologies underlying ecteinamine’s core structure. In all, the work detailed here unveils a new class of marine-derived natural products displaying highly diverse and uncommon structural features and whose biosynthetic underpinnings add to a growing family of natural products generated by the actions of multiple BGCs as well as unclustered genes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Xu-Wen Li at Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Dr. Yuki Sugimoto at Harvard Medical School, and Dr. Fei Xu at Zhejiang University for help with analyzing the biosynthesis of ecteinamines; Randy Hamchand at Yale University for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript; Dr. Xuefeng Jiang at East China Normal University for helping to analyze the sulfur chemistry; Dr. Sheng-Xiong Huang at Kunming Institute of Botany for sharing the information on kedarcidin biosynthesis; and Dr. Neil Miller at UW-Madison Department of Bacteriology for studies aimed at understanding ecteinamine biosynthesis. This work was funded by NIH Grants U19AI109673, U19AI142720, and R01AT009874. We would like to thank the Analytical Instrumentation Center at the School of Pharmacy, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for the facilities to acquire spectroscopic data. This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grant P41GM103399 (NIGMS), old number: P41RR002301. Equipment was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the NIH (P41GM103399, S10RR02781, S10RR08438, S10RR023438, S10RR025062, S10RR029220), the NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), and the USDA. The Bruker Quazar APEX2 was purchased by the UW-Madison Department of Chemistry with a portion of a generous gift from Paul J. and Margaret M. Bender.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c06410.

General experimental details, metabolomics details, genomics details, isolation and structural elucidation of ecteinamines, details on the investigation of siderophore/metallophore activity of ecteinamine A, details on proposed biosynthetic pathway, stable isotope feeding study, NMR and MS spectra for ecteinamines; in addition, identifying information for data depositions to MassIVE(MS/MS), Natural Products Atlas, and Paired Omics Platform repositories (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 2090757 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.2c06410

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Qihao Wu, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States.

Bailey A. Bell, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States

Jia-Xuan Yan, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States;.

Marc G. Chevrette, Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, United States;

Nathan J. Brittin, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States

Yanlong Zhu, Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States;.

Shaurya Chanana, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States.

Mitasree Maity, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States.

Doug R. Braun, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States

Amelia M. Wheaton, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States;

Ilia A. Guzei, Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States;

Ying Ge, Department of Cell and Regenerative Biology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States;; Department of Chemistry, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States;

Scott R. Rajski, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States

Michael G. Thomas, Department of Bacteriology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, United States

Tim S. Bugni, Pharmaceutical Sciences Division, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53705, United States; The Small Molecule Screening Facility, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin 53792, United States;

REFERENCES

- (1).Wolfender JL; Litaudon M; Touboul D; Queiroz EF Innovative omics-based approaches for prioritisation and targeted isolation of natural products - new strategies for drug discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep 2019, 36, 855–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Schorn MA; Verhoeven S; Ridder L; Huber F; Acharya DD; Aksenov AA; Aleti G; Moghaddam JA; Aron AT; Aziz S; et al. A community resource for paired genomic and metabolomic data mining. Nat. Chem. Biol 2021, 17, 363–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Machado H; Tuttle RN; Jensen PR Omics-based natural product discovery and the lexicon of genome mining. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 2017, 39, 136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Atanasov AG; Zotchev SB; Dirsch VM; Supuran CT Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 200–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bouslimani A; Sanchez LM; Garg N; Dorrestein PC Mass spectrometry of natural products: current, emerging and future technologies. Nat. Prod. Rep 2014, 31, 718–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Medema MH The year 2020 in natural product bioinformatics: an overview of the latest tools and databases. Nat. Prod. Rep 2021, 38, 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kalkreuter E; Pan G; Cepeda AJ; Shen B Targeting bacterial genomes for natural product discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2020, 41, 13–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Goering AW; McClure RA; Doroghazi JR; Albright JC; Haverland NA; Zhang Y; Ju KS; Thomson RJ; Metcalf WW; Kelleher NL Metabologenomics: correlation of microbial gene clusters with metabolites drives discovery of a nonribosomal peptide with an unusual amino acid monomer. ACS Cent. Sci 2016, 2, 99–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).van der Hooft J; Mohimani H; Bauermeister A; Dorrestein PC; Duncan KR; Medema MH Linking genomics and metabolomics to chart specialized metabolic diversity. Chem. Soc. Rev 2020, 49, 3297–3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Doroghazi JR; Albright JC; Goering AW; Ju KS; Haines RR; Tchalukov KA; Labeda DP; Kelleher NL; Metcalf WW A roadmap for natural product discovery based on large-scale genomics and metabolomics. Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 963–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Caesar LK; Montaser R; Keller NP; Kelleher NL Metabolomics and genomics in natural products research: complementary tools for targeting new chemical entities. Nat. Prod. Rep 2021, 38, 2041–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Harvey AL; Edrada-Ebel R; Quinn RJ The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 111–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).McCaughey CS; van Santen JA; van der Hooft J; Medema MH; Linington RG An isotopic labeling approach linking natural products with biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Chem. Biol 2022, 18, 295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Walsh CT; Fischbach MA Natural products version 2.0: connecting genes to molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 2469–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Mevers E; Saurí J; Helfrich EJN; Henke M; Barns KJ; Bugni TS; Andes D; Currie CR; Clardy J Pyronitrins A-D: chimeric natural products produced by Pseudomonas protegens. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 17098–17101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ma GL; Candra H; Pang LM; Xiong J; Ding Y; Tran HT; Low ZJ; Ye H; Liu M; Zheng J; et al. Biosynthesis of tasikamides via pathway coupling and diazonium-mediated hydrazone formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 1622–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kurita KL; Glassey E; Linington RG Integration of highcontent screening and untargeted metabolomics for comprehensive functional annotation of natural product libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 11999–12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hoffmann T; Krug D; Hüttel S; Müller R Improving natural products identification through targeted LC-MS/MS in an untargeted secondary metabolomics workflow. Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 10780–10788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tsugawa H; Rai A; Saito K; Nakabayashi R Metabolomics and complementary techniques to investigate the plant phytochemical cosmos. Nat. Prod. Rep 2021, 38, 1729–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hou Y; Braun DR; Michel CR; Klassen JL; Adnani N; Wyche TP; Bugni TS Microbial strain prioritization using metabolomics tools for the discovery of natural products. Anal. Chem 2012, 84, 4277–4283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chanana S; Thomas CS; Zhang F; Rajski SR; Bugni TS hcapca: Automated hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis of large metabolomic datasets in R. Metabolites 2020, 10, 297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zhang F; Zhao M; Braun DR; Ericksen SS; Piotrowski JS; Nelson J; Peng J; Ananiev GE; Chanana S; Barns K; et al. A marine microbiome antifungal targets urgent-threat drug-resistant fungi. Science 2020, 370, 974–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang M; Carver JJ; Phelan VV; Sanchez LM; Garg N; Peng Y; Nguyen DD; Watrous J; Kapono CA; Luzzatto-Knaan T; et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol 2016, 34, 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Zhang F; Wyche TP; Zhu YL; Braun DR; Yan JX; Chanana S; Ge Y; Guzei IA; Chevrette MG; Currie CR; et al. MS-derived isotopic fine structure reveals forazoline A as a thioketone-containing marine-derived natural product. Org. Lett 2020, 22, 1275–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Buchfink B; Reuter K; Drost HG Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 366–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Blin K; Shaw S; Steinke K; Villebro R; Ziemert N; Lee SY; Medema MH; Weber T antiSMASH 5.0: updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W81–W87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lohman JR; Huang SX; Horsman GP; Dilfer PE; Huang T; Chen Y; Wendt-Pienkowski E; Shen B Cloning and sequencing of the kedarcidin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptoalloteichus sp. ATCC 53650 revealing new insights into biosynthesis of the enediyne family of antitumor antibiotics. Mol. Biosyst 2013, 9, 478–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zhao B; Moody SC; Hider RC; Lei L; Kelly SL; Waterman MR; Lamb DC Structural analysis of cytochrome P450 105N1 involved in the biosynthesis of the zincophore, coelibactin. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 8500–8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bloudoff K; Schmeing TM Structural and functional aspects of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase condensation domain superfamily: discovery, dissection and diversity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom 2017, 11, 1587–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wyche TP; Piotrowski JS; Hou Y; Braun D; Deshpande R; McIlwain S; Ong IM; Guzei IA; Westler WM; Andes DR; et al. Forazoline A: marine-derived polyketide with antifungal in vivo efficacy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 11583–11586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Galm U; Hager MH; Van Lanen SG; Ju J; Thorson JS; Shen B Antitumor antibiotics: bleomycin, enediynes, and mitomycin. Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 739–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Shaaban KA; Shaaban M; Rahman H; Grün-Wollny I; Kämpfer P; Kelter G; Fiebig H; Laatsch H Karamomycins A-C: 2-Naphthalen-2-yl-thiazoles from Nonomuraea endophytica. J. Nat. Prod 2019, 82, 870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Motohashi K; Takagi M; Shin-Ya K Tetrapeptides possessing a unique skeleton, JBIR-34 and JBIR-35, isolated from a sponge-derived actinomycete, Streptomyces sp. Sp080513GE-23. J. Nat. Prod 2010, 73, 226–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Tsukamoto M; Murooka K; Nakajima S; Abe S; Suzuki H; Hirano K; Kondo H; Kojiri K; Suda H BE-32030 A, B, C, D and E, new antitumor substances produced by Nocardia sp. A32030. J. Antibiot 1997, 50, 815–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Izumikawa M; Kawahara T; Kagaya N; Yamamura H; Hayakawa M; Takagi M; Yoshida M; Doi T; Shin-ya K Pyrrolidine-containing peptides, JBIR-126, –148, and –149, from Streptomyces sp. NBRC 111228. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 5333–5336. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Muliandi A; Katsuyama Y; Sone K; Izumikawa M; Moriya T; Hashimoto J; Kozone I; Takagi M; Shin-ya K; Ohnishi Y Biosynthesis of the 4-methyloxazoline-containing nonribosomal peptides, JBIR-34 and –35, in Streptomyces sp. Sp080513GE-23. Chem. Biol 2014, 21, 923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kato Y; Kuroda T; Huang Y; Ohta R; Goto Y; Suga H Chemoenzymatic posttranslational modification reactions for the synthesis of Ψ[CH2NH]-containing peptides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Williams DE; Austin P; Diaz-Marrero AR; Soest RV; Matainaho T; Roskelley CD; Roberge M; Andersen RJ Neopetrosiamides, peptides from the marine sponge Neopetrosia sp. that inhibit amoeboid invasion by human tumor cells. Org. Lett 2005, 7, 4173–4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Jones LH Dehydroamino acid chemical biology: an example of functional group interconversion on proteins. RSC Chem. Biol 2020, 1, 298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Dunbar KL; Scharf DH; Litomska A; Hertweck C Enzymatic carbon-sulfur bond formation in natural product biosynthesis. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 5521–5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Gong B; Bai E; Feng X; Yi L; Wang Y; Chen X; Zhu X; Duan Y; Huang Y Characterization of chalkophomycin, a copper(II) metallophore with an unprecedented molecular architecture. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 20579–20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Suvarna K; Stevenson D; Meganathan R; Hudspeth ME Menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis: localization and characterization of the menA gene from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol 1998, 180, 2782–2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hiratsuka T; Furihata K; Ishikawa J; Yamashita H; Itoh N; Seto H; Dairi T An alternative menaquinone biosynthetic pathway operating in microorganisms. Science 2008, 321, 1670–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Seto H; Jinnai Y; Hiratsuka T; Fukawa M; Furihata K; Itoh N; Dairi T Studies on a new biosynthetic pathway for menaquinone. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 5614–5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Mahanta N; Fedoseyenko D; Dairi T; Begley TP Menaquinone biosynthesis: formation of aminofutalosine requires a unique radical SAM enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 15318–15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Mahanta N; Hicks KA; Naseem S; Zhang Y; Fedoseyenko D; Ealick SE; Begley TP Menaquinone biosynthesis: biochemical and structural studies of chorismate dehydratase. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 1837–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Kautsar SA; Blin K; Shaw S; Navarro-Muñoz JC; Terlouw BR; van der Hooft J; van Santen JA; Tracanna V; Suarez Duran HG; Pascal Andreu V; et al. MIBiG 2.0: a repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D454–D458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Katsuyama Y; Sone K; Harada A; Kawai S; Urano N; Adachi N; Moriya T; Kawasaki M; Shin-Ya K; Senda T; Ohnishi Y Structural and functional analyses of the tridomainnonribosomal peptide synthetase FmoA3 for 4-methyloxazoline ring formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 14554–14562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Inahashi Y; Zhou S; Bibb MJ; Song L; Al-Bassam MM; Bibb MJ; Challis GL Watasemycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces venezuelae: thiazoline C-methylation by a type B radical-SAM methylase homologue. Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 2823–2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Zhang G; Zhang H; Li S; Xiao J; Zhang G; Zhu Y; Niu S; Ju J; Zhang C Characterization of the amicetin biosynthesis gene cluster from Streptomyces vinaceusdrappus NRRL 2363 implicates two alternative strategies for amide bond formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2012, 78, 2393–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Pfeifer BA; Wang CC; Walsh CT; Khosla C Biosynthesis of yersiniabactin, a complex polyketide-nonribosomal peptide, using Escherichia coli as a heterologous host. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2003, 69, 6698–6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Capon RJ Extracting value: mechanistic insights into the formation of natural product artifacts - case studies in marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep 2020, 37, 55–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Yamamoto T; Tsunematsu Y; Hara K; Suzuki T; Kishimoto S; Kawagishi H; Noguchi H; Hashimoto H; Tang Y; Hotta K; Watanabe K Oxidative trans to cis isomerization of olefins in polyketide biosynthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 6207–6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Patel HM; Tao J; Walsh CT Epimerization of an L-cysteinyl to a D-cysteinyl residue during thiazoline ring formation in siderophore chain elongation by pyochelin synthetase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 10514–10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Li JH; Cho W; Hamchand R; Oh J; Crawford JM A conserved nonribosomal peptide synthetase in Xenorhabdus bovienii produces citrulline-functionalized lipopeptides. J. Nat. Prod 2021, 84, 2692–2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Seyedsayamdost MR; Traxler MF; Zheng SL; Kolter R; Clardy J Structure and biosynthesis of amychelin, an unusual mixed-ligand siderophore from Amycolatopsis sp. AA4. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 11434–11437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Fukuda TTH; Helfrich EJN; Mevers E; Melo WGP; Van Arnam EB; Andes DR; Currie CR; Pupo MT; Clardy J Specialized metabolites reveal evolutionary history and geographic dispersion of a multilateral symbiosis. ACS Cent. Sci 2021, 7, 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Hesketh A; Kock H; Mootien S; Bibb M The role of absC, a novel regulatory gene for secondary metabolism, in zinc-dependent antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Microbiol 2009, 74, 1427–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Koh EL; Henderson JP Microbial copper-binding siderophores at the host-pathogen interface. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 18967–18974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Sandy M; Butler A Microbial iron acquisition: marine and terrestrial siderophores. Chem. Rev 2009, 109, 4580–4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Martinez JS; Butler A Marine amphiphilic siderophores: marinobactin structure, uptake, and microbial partitioning. J. Inorg. Biochem 2007, 101, 1692–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.