Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the incidence rates of lung cancer in women compared with men from 2000 to 2019.

A previous study from the American Cancer Society reported higher lung cancer incidence in women than men younger than 50 years in the US, a reversal in the historically higher burden in men that was not fully explained by smoking differences.1 It is unknown, however, whether this pattern has changed in contemporary birth cohorts. Herein, we extended the previous analysis with an additional 5 years of data to monitor shifts in lung cancer incidence by age and sex.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, population-based incidence data on lung and bronchus cancer diagnosed from 2000 to 2019 were obtained from 22 registries of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program, covering nearly 50% of the US population.2 Cases were stratified by sex, age in 5-year increments (30-34 to ≥85 years), and year of diagnosis (2000-2004, 2005-2009, 2010-2014, and 2015-2019). Data on race and ethnicity were available but not reported because of the study emphasis on age and sex.

Age-specific lung cancer incidence rates per 100 000 person-years adjusted for delays in reporting were calculated using SEER*Stat, version 8.4.1.3 The Tiwari method was used to calculate female to male rate ratios and 95% CIs. Two-sided testing at P < .05 was considered statistically significant.4 This study was based on deidentified publicly available data and therefore exempt from institutional review board approval or informed consent per Common Rule 45 CFR §46. This study followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Results

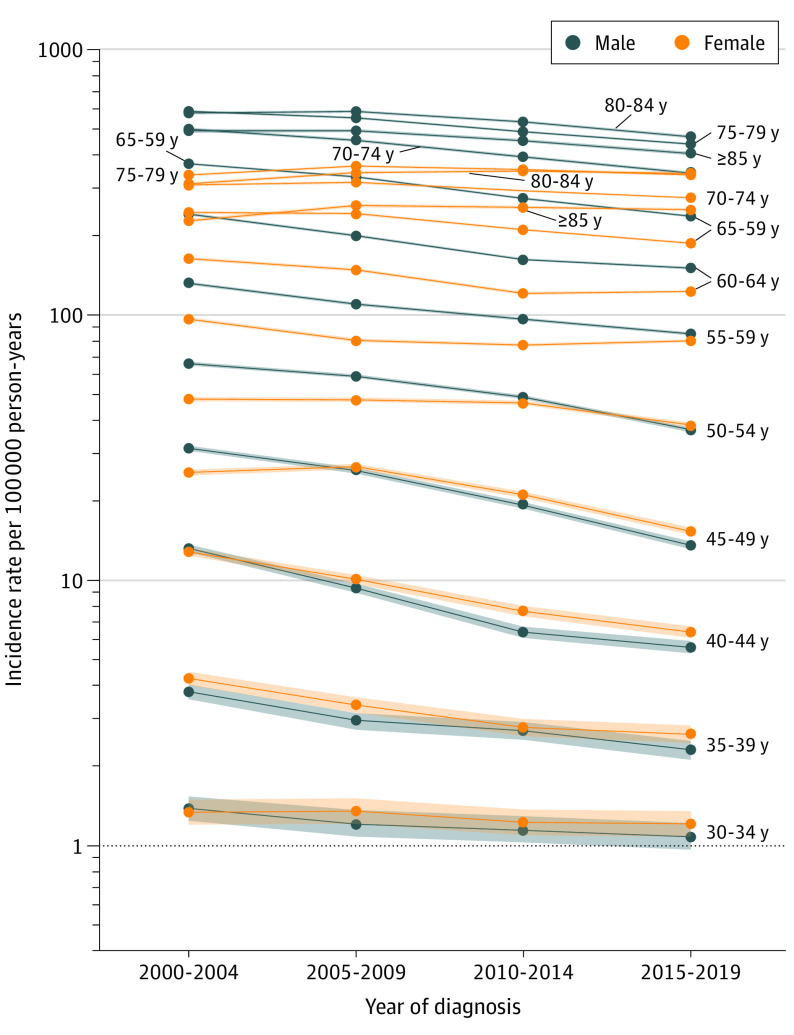

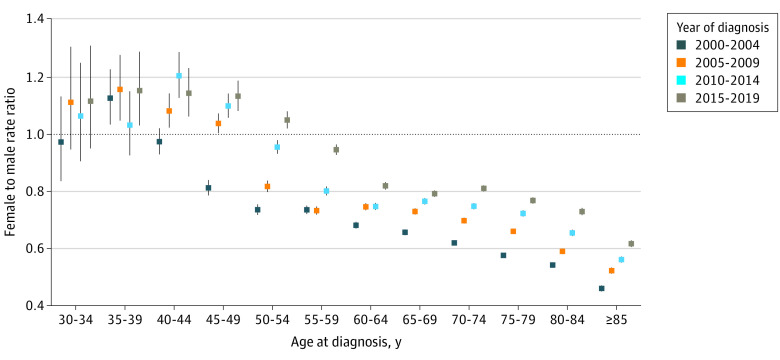

Overall, the declines in the incidence rates between 2000-2004 and 2015-2019 were greater in men than women, leading to a higher incidence in women aged 35 to 54 years (Figure 1). Among individuals aged 50 to 54 years, for example, the rate per 100 000 person-years decreased by 44% in men (from 65.6; 95% CI, 64.5-66.6 to 36.8; 95% CI, 36.1-37.6) and by 20% in women (from 48.1; 95% CI, 47.2-49.0 to 38.5; 95% CI, 37.8-39.3). As a result, the female to male incidence rate ratio increased from 0.73 (95% CI, 0.72-0.75) during 2000-2004 to 1.05 (95% CI, 1.02-1.08) during 2015-2019 (Figure 2). Among individuals aged 55 years or older, however, incidence rates continued to be lower in women, although differences became increasingly smaller (Figure 1). Among persons aged 70 to 74 years, for example, the female to male incidence rate ratio increased from 0.62 (95% CI, 0.61-0.63) during 2000-2004 to 0.81 (95% CI, 0.80-0.82) during 2015-2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Changes in Lung Cancer Incidence Rates by Sex and 5-Year Age Groups From 2000-2004 to 2015-2019.

Rates are per 100 000 person-years and adjusted for delays in case reporting. Shading indicates 95% CIs.

Figure 2. Lung Cancer Female to Male Incidence Rate Ratios by 5-Year Age Groups From 2000-2004 to 2015-2019.

Men served as the reference group. Error bars indicate the 95% CIs.

Discussion

Based on high-quality population-based data, we found that the higher lung cancer incidence in women than in men has not only continued in individuals younger than 50 years but also now extends to middle-aged adults as younger women with a high risk of the disease enter older age. Reasons for this shift are unclear because the prevalence and intensity of smoking are not higher in younger women compared with men except for a slightly elevated prevalence among those born in the 1960s.1 In addition, findings from cohort studies do not support higher carcinogenic effects of cigarette smoking in women than in men, although these studies were largely based on persons older than 50 years born before the 1960s.5 Overdiagnosis is unlikely to be a major contributor to the excess risk in younger women because it occurred in both early- and late-stage tumors, as shown previously.1 Occupational exposures (eg, asbestos), which are more prevalent in men, have substantially reduced over the past decades and may have partly contributed to the shift in the disease burden. Further research is needed to elucidate reasons for the higher lung cancer incidence in younger women. Meanwhile, cigarette smoking cessation efforts should be intensified among younger and middle-aged women, and lung cancer screening encouraged among eligible women at both health care professional and community levels. Limitations of the study include the lack of individual risk factor data in the analytical database and not accounting for the growth in populations born outside the US during the study period, but cigarette smoking among non–US born individuals is substantially lower in women than men.6

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Jemal A, Miller KD, Ma J, et al. Higher lung cancer incidence in young women than young men in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1999-2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1715907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute . Surveillance research program. April 2022. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov

- 3.National Cancer Institute. SEER*Stat software. August 14, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat

- 4.Tiwari RC, Clegg LX, Zou Z. Efficient interval estimation for age-adjusted cancer rates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2006;15(6):547-569. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Keeffe LM, Taylor G, Huxley RR, Mitchell P, Woodward M, Peters SAE. Smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer in women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e021611. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pampel F, Khlat M, Bricard D, Legleye S. Smoking among immigrant groups in the united states: prevalence, education gradients, and male-to-female ratios. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(4):532-538. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement