Abstract

Objective:

To analyze gender differences in authorship of North American (Canadian and American) and international published otolaryngology—head and neck surgery (OHNS) clinical practice guidelines (CPG) over a 17-year period.

Methods:

Clinical practice guidelines published between 2005 and 2022 were identified through the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) search strategy in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Studies were included if they were original studies, published in the English language, and encompassed Canadian, American, or international OHNS clinical practice guidelines.

Results:

A total of 145 guidelines were identified, encompassing 661 female authors (27.4%) and 1756 male authors (72.7%). Among OHNS authors, women and men accounted for 21.2% and 78.8% of authors, respectively. Women who were involved in guideline authorship were 31.0% less likely to be an otolaryngologist compared to men. There were no gender differences across first or senior author and by subspeciality. Female otolaryngologist representation was the greatest in rhinology (28.3%) and pediatrics (26.7%). American guidelines had the greatest proportion of female authors per guideline (34.1%) and the greatest number of unique female authors (33.2%).

Conclusion:

Despite the increasing representation of women in OHNS, gender gaps exist with regards to authorship within clinical practice guidelines. Greater gender diversity and transparency is required within guideline authorship to help achieve equitable gender representation and the development of balanced guidelines with a variety of viewpoints.

Keywords: otolaryngology, gender differences, authorship, clinical guidelines

Introduction

Over the past several decades, there has been a trend toward increasing representation of women across the field of medicine, from the level of medical students to practicing physicians. Though this is promising, women continue to be disproportionately underrepresented in surgical specialties, and encounter gender-based discrimination, sexual harassment, and fewer academic promotions.1 -4 When considering otolaryngology—head and neck surgery (OHNS), there is notable underrepresentation of women. Women are underrepresented within residency programs and academic positions, including chair persons, program directors, professors, and on editorial boards both in Canada and the United States (US).5 -7 While gender disparities in OHNS have been characterized in North America, there is limited information available regarding female representation in OHNS globally.

The greatest gender disparity exists within academic medicine and research. Authorship and academic productivity are key metrics of academic achievement, playing a role in professional and career development, and obtaining grants and awards.8,9 Publications and research output correlate with overall academic success and career advancement as significant emphasis is placed on scholarly productivity, research output and impact, and educational involvement when considering academic promotion.10 -15 Previous studies have found significant gender differences within otolaryngology in publications, grant funding, and national conference representation, with women demonstrating decreased research productivity and contributions compared to their male counterparts.16 -19

There is currently a lack of published literature on the representation of women within clinical practice guidelines (CPG). Guideline authorship is unique in that the authors are typically leaders in the field who are selected by invitation, a process that lacks transparency and introduces an opportunity for gender bias. 20 Analysis of the gender of clinical practice guideline authors has been conducted and compared broadly across other medical specialties; however, this has not yet been done in OHNS.20 -23 Thus, the objective of this study was to analyze gender differences in authorship of North American (Canadian and US) and international published OHNS clinical practice guidelines over a 17-year period.

Methods

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required, as stated under the Canadian guidelines in the Tri-Council Policy Statement, article 2.2 for research involving publicly available data. 24 The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was utilized in this study. 25

The search strategy was developed by a hospital librarian to identify guidelines published in OHNS between 2005 and 2020 in MEDLINE and EMBASE, utilizing the validated Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH) search filter. 26 Articles were accessed on May 4, 2022 and studies were screened by 1 reviewer. Inclusion criteria included: (1) Canadian, American, or international otolaryngology guidelines, (2) guidelines summarizing clinical practice, (3) guidelines published between 2005 and 2022, (4) English language, and (5) original study. Position statements, clinical consensus statements, clinical practice guidelines, and practice recommendations were included. Studies were excluded if they were: (1) compilation or summaries of previous guidelines, (2) not related to clinical practice (ie, education tools), and (3) literature reviews and commentaries. Only international guidelines were included, and country-specific guidelines, aside from Canadian and American, were not considered.

Extracted variables included: study type, year of publication, associated society, author name, gender, degree (MD/DO, PhD, and MSc), specialty of physician authors, and otolaryngology subspecialty. Study types included: clinical practice guidelines, consensus statements, position statements, and practice parameters. The categorization of subspecialities included: general otolaryngology, head and neck, otology/neurotology, rhinology, pediatrics, and laryngology. Gender of authors were defined as binary “male,” “female,” or “unknown.” This variable was extracted based on author name, pronouns, and/or Google search with the author’s name with/without subspeciality to find publicly available photos for reference or images on university and hospital websites.

Statistical Analysis

The cohort of guideline authors were characterized using descriptive statistics. Differences in gender across study type, discipline of presentation, and publication rate were examined using chi-square test and logistic regression with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). A 2-tailed alpha of .05 was used to determine significant differences between genders. The analysis and all statistical tests were completed using SAS Software (version 9.4; SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Demographics

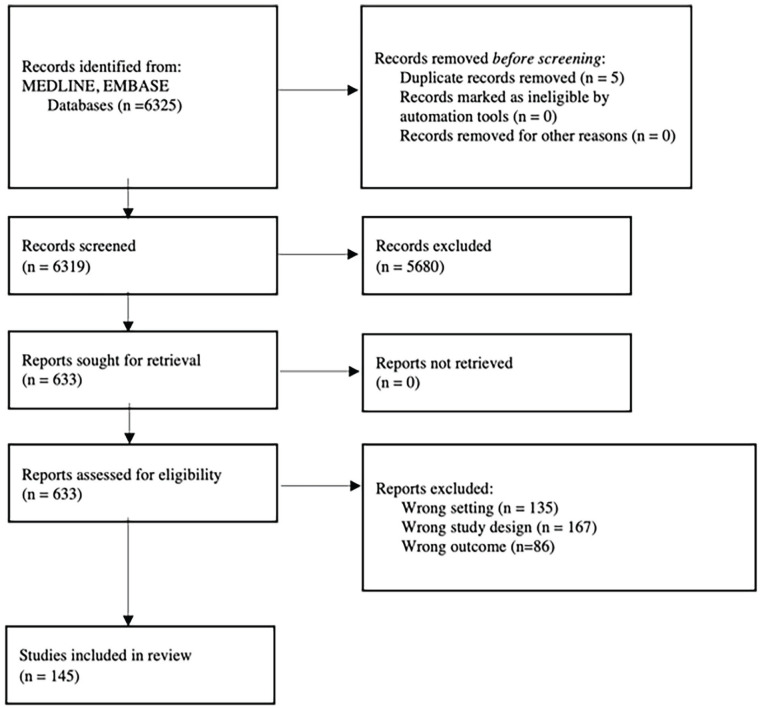

The literature search identified 6325 guidelines for screening (Figure 1). One hundred and forty-five OHNS guidelines published between 2005 and 2022 were identified and data from 2435 authors were initially extracted. Of the 2435 authors, 3 were removed due to unknown gender and 15 were removed due to unspecified publication type, resulting in a final sample of 2417.

Figure 1.

Screening and identification of articles.

Overall Gender Characteristics of Published Guidelines

Overall, 661 authors were female (27.4%) and 1756 were male (72.7%). Further, 65.2% of female authors were unique individuals (n = 431) and 66.8% of male authors were unique individuals (n = 1173). The median number of authors per guideline was 14 (IQR: 8.0-20.0), consisting of a median of 4 women (IQR: 1.0-7.0) and 9 men (IQR: 6.0-13.0) per guideline. Guidelines had significantly fewer female otolaryngologist authors (21.2%; n = 374) than female physicians from other specialties (28.2%; n = 113; P < .01). Similarly, there was a significant difference in the number of unique female physician authors (27.4%; n = 96) compared to the number of unique female otolaryngologists (20.7%; n = 222) (P < .01).

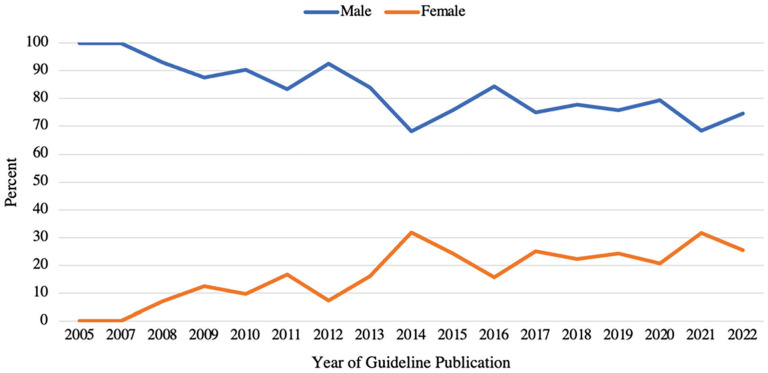

Over time, the proportion of female authors involved in published guidelines significantly increased from 0% in 2005 to 25.4% in 2022 (P < .01; Figure 2). Guidelines published in 2021 had the greatest number of female authors (31.7%).

Figure 2.

Female otolaryngology representation in guideline authorship over time (2005-2022).

Gender Characteristics of Published Guidelines for Otolaryngologists

The majority of authors were physicians (89.3%; n = 2131), versus basic scientists or allied health professionals, and of those physicians, 81.3% (n = 1761) were otolaryngologists. The median number of otolaryngologists per guideline was 9 (IQR: 6.0-13.0), with the median number of female otolaryngologists being 3 (IQR: 1.0-5.5) and male otolaryngologists being 8 (IQR: 5.0-15.5). There was no difference in the proportion of unique male (61.4%; n = 851) and female (59.4%; n = 222) otolaryngologists.

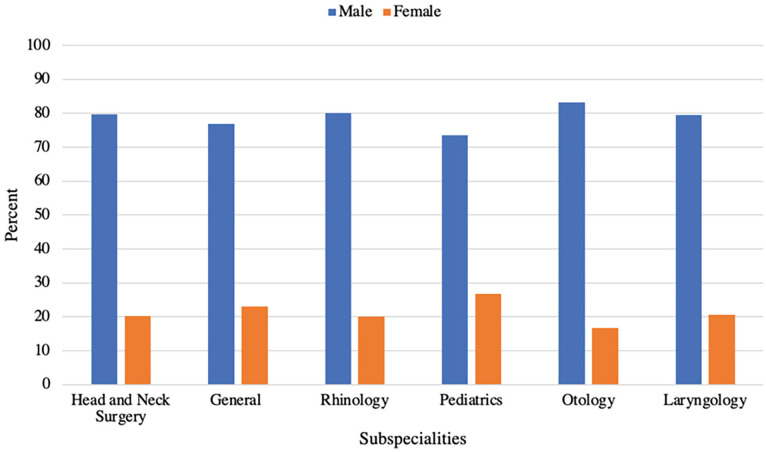

Women who were involved in guideline authorship were 31.0% less likely to be an otolaryngologist (OR: 0.69; 95%CI: 0.54-0.88) compared to men. There were also no gender differences in otolaryngologist representation across surgical subspecialties (P = .05; Table 1). Female otolaryngologist representation was the greatest in rhinology (28.3%) and pediatrics (26.7%; Figure 3). There was no significant difference between gender and the likelihood of being a first or senior author (P = .53; Table 1).

Table 1.

Author Variables by Gender of Otolaryngologist.

| Variables | Overall (N = 1761) | Male otolaryngologist (N = 1387) | Female otolaryngologist (N = 374) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||

| Author type a | .53 | |||

| First author | 56.1 (129) | 55.0 (99) | 60.0 (30) | |

| Senior author | 43.9 (101) | 45.0 (81) | 40.0 (20) | |

| Representation by subspecialty | .05 | |||

| Head and neck | 13.2 (232) | 13.3 (185) | 12.6 (47) | |

| General | 12.0 (212) | 11.8 (163) | 13.1 (49) | |

| Rhinology | 30.2 (531) | 30.6 (425) | 28.3 (106) | |

| Pediatrics | 21.4 (377) | 20.0 (277) | 26.7 (100) | |

| Otology | 17.7 (312) | 18.8 (260) | 13.9 (52) | |

| Laryngology | 5.5 (97) | 5.6 (77) | 5.4 (20) | |

| Country of published guideline | .03 | |||

| Canada | 7.3 (128) | 7.3 (101) | 7.2 (27) | |

| USA | 42.2 (741) | 40.5 (561) | 48.1 (180) | |

| International | 50.6 (889) | 52.2 (722) | 44.7 (167) | |

Sample size differs from totals as each publication only contained 1 first author and 1 senior author.

Figure 3.

Female and male otolaryngologist representation by subspeciality.

Published Guidelines by Country

When examining the country of origin for each guideline, the US had the most published guidelines with 85, followed by international guidelines at 45, and 14 guidelines from Canada. Congruent with this, 48.0% (n = 1160) of authors, from any specialty, were from the US. This was followed by international authors with 45.1% (n = 1087), and Canadian authors with 6.9% (n = 167).

The representation of female otolaryngologists who authored published guidelines differed by country (P = .03). Male otolaryngologists were most likely to be authors in international guidelines, whereas female otolaryngologists were more likely to be authors in American guidelines (Table 1). There was also a significant difference in the proportion of female otolaryngologist authors per guideline by publishing country, with the greatest proportion of female authors coming from the US (n = 180, 24.3%; P = .03; Table 2). There was also a significant difference in the number of unique female otolaryngologist authors by country, with the US having the greatest number of unique female authors at 24.7% (P = .02). Only 28.2% of international guidelines contained more than 25% female otolaryngologist authors. This was followed by Canadian at 33.3% of guidelines with more than 25% female representation, and the US at 53.8%.

Table 2.

Guideline Publication Characteristics by Country of Publication for Otolaryngologists.

| Variables | Canada (N = 128) | USA (N = 741) | International (N = 889) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | ||||

| Number of female authors per guideline | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.0-3.5) | 3.0 (1.0-4.5) | 4.0 (1.0-7.0) | n/a |

| Gender of total authors per guideline | ||||

| Male | 78.9 (101) | 75.7 (561) | 81.2 (722) | .03 |

| Female | 21.1 (27) | 24.3 (180) | 18.8 (167) | |

| Gender of first authors a | ||||

| Male | 83.3 (10) | 75.0 (54) | 77.3 (34) | .81 |

| Female | 16.7 (2) | 25.0 (18) | 22.7 (10) | |

| Gender of senior authors a | ||||

| Male | 100.0 (10) | 76.9 (40) | 79.0 (30) | .24 |

| Female | 0.0 (0) | 23.1 (12) | 21.0 (8) | |

| Female representation by subspecialty | ||||

| Head and neck | 0.0 (0) | 23.9 (43) | 2.4 (4) | <.01 |

| General | 29.6 (8) | 15.6 (28) | 7.8 (13) | |

| Rhinology | 29.6 (8) | 21.1 (38) | 35.9 (60) | |

| Pediatrics | 22.2 (6) | 18.3 (33) | 36.5 (61) | |

| Otology | 18.5 (5) | 16.7 (30) | 10.2 (17) | |

| Laryngology | 0.0 (0) | 4.4 (8) | 7.2 (12) | |

Sample size differs from totals as each publication only contained 1 first author and 1 senior author.

International guidelines had a median of 4 (IQR: 1.0-7.0) female otolaryngologists per publication, Canada had a median of 2.5 (IQR: 1.0-3.5), and the US had a median of 3 (IQR: 1.0-4.5) female otolaryngologists involved in guideline publications (Table 2).

Society-Specific Gender Differences

There were 98 society-specific guidelines identified, with 9.2% (n = 9) from the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) and the Canadian Society of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (CSO-HNS). Among the guidelines published by the AAO-HNS, 38.0% of authors were female, whereas guidelines published by the CSO-HNS contained 19.5% female authors (P = .01). When examining female otolaryngologists, they accounted for 22.2% (n = 22) and 24.9% (n = 88) of authors in guidelines published by the CSO-HNS, and AAO-HNS, respectively (P = .58).

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the global representation and authorship of females in OHNS clinical guidelines. It adds to the growing but minimal body of literature on the status of women in OHNS and adds an international perspective on changes in guideline authorship over the last 17 years. This study found that while the representation of women has been increasing over time, women account for less than one third of authors in clinical guidelines. When considering the country of publication, the US had the greatest proportion of female authors per guideline, followed by Canadian and international guidelines. Further advocacy efforts are required to promote and support women in otolaryngology globally.

The representation of women decreases through medical school to surgical residency, fellowship, and even further in senior academic roles, a phenomenon known as the “leaky pipeline.” Women typically comprise 50% of graduating medical students, but represented only 34.7% of OHNS residents, and 24.5% of academic faculty in the US in 2019. 27 Similarly in Canada, females represented 41.9% of OHNS residents and only 18.7% of academic faculty in 2019. 6 Despite the lower proportions of women in higher levels of leadership, the number of women is significantly increasing within OHNS. In Canada, the number of practicing female otolaryngologists increased from 10% to 24.3% between 2000 and 2019, and similarly in the US, representation increased from 6% to 32% between 1998 and 2015.6,28,29 While the field is approaching gender parity, women continue to be significantly underrepresented within leadership roles. 30

Given the disparities within academic medicine, it is not surprising that women are also underrepresented within guideline authorship, accounting for only 20% of guideline authors. Guideline writing groups involve knowledgeable individuals from many specialties, with expertise being determined by clinical experience and research expertise on the topic. Selection of authorship within clinical practice guidelines and position statements lacks transparency and is typically determined by informal invitation, creating an opportunity for sex bias compared to self-driven authorship of original research works. 21 This study found that female authors were more likely to be non-otolaryngologists, consistent with previous studies which found that female authors in otolaryngology papers are more likely to be non-physicians.31,32 Male otolaryngologists have a greater number of publications, citations, co-authorships, and actively publish for more years, which may be a contributing factor to underrepresentation of females within clinical guidelines.18,33 However, various studies suggest that female otolaryngologists may have the same research productivity as their male counterparts.34,35 The number of female first and senior authors in otolaryngology literature significantly increased between 2000 and 2015. 17 As more women become otolaryngologists, enter positions of leadership earlier in their career, and serve as mentors, it may encourage young female otolaryngologists to pursue careers in academia, and to increase contributions to research and academia.15,36

There was a significant difference in the representation of female otolaryngologists by country. While data is available on the distribution of female otolaryngologists in Canada and the United States, no such data exists on an international scale. Canadian guidelines had the fewest number of female authors per guideline. In 2019, women represented 38.9% of otolaryngologists in academic medicine in Canada but only 22.2% of authors were women in Canadian guidelines. 6 Conversely, the representation of female otolaryngologists within guidelines was greater than their representation within academia in the US. Female otolaryngologists accounted for 34.1% of authors but represented 24.6% of female OHNS faculty in the US in 2019. 27 The AAO-HNS developed a comprehensive branch dedicated towards promoting women in otolaryngology (WIO) in 2010 and currently has over 2000 members. It includes endowment grants and mentorship programs, which could serve to explain why women are more represented in US guidelines than Canadian. Currently, no study has been conducted on a European, Asian, or international scale to assess female representation in OHNS. Studies assessing the status of women in otolaryngology have been primarily conducted in the US, with several studies conducted in Canada.6,17,18,27,34,36 -39

Gender representation in guideline authorship with respect to subspeciality was also explored. In this study, while no gender differences were found in authorship based on subspeciality, rhinology and pediatrics had the greatest female representation. It is not surprising that pediatric guidelines had high rates of female authors as prior literature has shown pediatrics to be the subspeciality with the greatest female representation.31,32,40 However, females have been traditionally underrepresented in rhinology.6,41 Prior research has shown that female authors accounted for less than an quarter of authors in rhinology journals and were significantly underrepresented as senior authors. 41 The increasing representation of female authorship within otolaryngology literature and across subspecialities over the last 20 years may account for the gender shift within rhinology literature.17,32 In a study assessing trends of authorship in 11 major otolaryngology journals between 2000 and 2015, Rhinology demonstrated the second greatest proportion of overall female authorship and the greatest increase in the number of first female authors. 17

Similar disparities have been found in other leadership roles. Women in otolaryngology lag behind their male counterparts in academic rank, academic society involvement, leadership roles within journal editorial roles, and national institute of health (NIH) grant funding.16,19,35,42,43 Gender bias is pervasive within surgery and there are various factors that could contribute to barriers women in OHNS face regarding career advancement and underrepresentation in guideline authorship.44,45 Gender bias may result from an unfavorable work environment, which can include harassment (including verbal and sexual), insufficient support (via mentorship or financially), and negative perceptions from superiors or peers. 45 Gender bias may also impact mentorship opportunities as there is a critical lack of role models and mentorship among both female surgeons and trainees.44,46 -50 Gender differences and societal expectations with regards to familial responsibilities are also a significant contributor to gender bias. Childbearing and motherhood impacts career advancement for female surgeons as they are more likely to be the primary caregiver and assume more childcare responsibilities.51 -56 Surgeon mothers can be regarded as weak in surgical capabilities, perceived to be less committed to work, and experience disapproval and criticism from senior surgeons, which unfairly impacts opportunities and remuneration.46,47,49,57 -59 As a whole, work environments and societal expectations for familial responsibilities can be major barriers to career advancement into or within academia, career satisfaction, and the motivation to contribute beyond the physician-patient encounter.44,46 -50

Diversity within guideline authorship is critical not only for the field of otolaryngology, but for patients. Authors of clinical guidelines should ideally reflect patient populations, and it is critical to achieve equity in diverse gender, race, and ethnicity representation in guideline authorship to ensure applicability of guidelines for diverse patient populations.20,23 While we found that female representation significantly increased over the study’s 17 year period, further improvements in equity, diversity, and inclusion are necessary. Currently, the appointment of individuals to guideline committees lacks transparency, as there are limited objective criteria to assess which individuals are experts within a given field and how guideline committee and leadership roles should be appointed. 60 The process must be transparent and equitable to allow for gender diversity. 60 Objective criteria to assess the quality of grants for funding and blinding of name, gender, and institution of authors could help to remove inherent biases. 20 Applying similar blinding and objective assessments to appointment of guideline committee authors and chairs may help to promote gender equity. 20 Allyship from male otolaryngologists in leadership positions is critical and their empowerment and advocacy for their female colleagues may play a role in advancing the status of women within academic OHNS. Leadership committees must make an active effort to ensure that female colleagues are included within guidelines. Furthermore, increasing research opportunities and grant funding for women may allow for greater contributions to academia, and subsequently, to guidelines. The WIO branch within the AAO-HNS and CSO-HNS should continue to create opportunities for women within the field of research and grant funding. Research mentorship programs may be useful in increasing academic productivity and creating visible role models for females interested in academia.

While this study was the first to assess trends in North American and international guideline authorship, it is not without limitations. Assumptions were made regarding authors’ genders and a binary definition of gender was employed. The authors are aware that gender exists on a continuum and those who do not identify as cis-women or cis-men were not accurately captured. Furthermore, gender differences in guideline committees and chair positions were not considered due to an inaccessibility of this data. The AAO-HNS published data on the members of the guideline committee on their webpage; however, this data was not available for other clinical guidelines, and was thus not extracted. This may have been an important consideration as a similar study to assess gender differences in authorship in cardiology clinical guidelines found that more women were co-authors on guidelines when women were chairs of guideline committees. 20 Furthermore, while different forms of clinical practice guidelines were included, such as position statements, clinical consensus statements, and practice recommendations, there is potential for variability in the quality of these guidelines. Lastly, this paper examined guidelines published between 2005 and 2022 and it is possible that more guidelines may be in the process of publication this year.

Conclusion

This study found that while the rates of female authorship within otolaryngology clinical guidelines has increased over time, women are still underrepresented. Female otolaryngologists are represented at greater rates in American guidelines compared to Canadian and international guidelines. Increasing gender diversity within guideline authorship, and at a broader level continuing to support female otolaryngologists to thrive within academia, will help achieve equitable representation and the development of balanced guidelines with a variety of viewpoints.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Darren Hamilton, Health Sciences Hospital Librarian, for his aid in developing the search strategy.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This project was a podium presentation at the 76th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Society of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, Sept 30 to Oct 3, 2022.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Dorsa Mavedatnia  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6625-9301

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6625-9301

References

- 1. Bruce AN, Battista A, Plankey MW, Johnson LB, Marshall MB. Perceptions of gender-based discrimination during surgical training and practice. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:25923. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.25923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walton MM. Sexual equality, discrimination and harassment in medicine: it’s time to act. Med J Aust. 2015;203(4):167-169. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burgos CM, Josephson A. Gender differences in the learning and teaching of surgery: a literature review. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:110-124. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5380.ca6b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273(13):1022-1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eloy JA, Blake DM, D’Aguillo C, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Baredes S. Academic benchmarks for otolaryngology leaders. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(8):622-629. doi: 10.1177/0003489415573073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grose E, Chen T, Siu J, Campisi P, Witterick IJ, Chan Y. National trends in gender diversity among trainees and practicing physicians in otolaryngology—head and neck surgery in Canada. JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2022;148(1):13-19. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fu T, Wu V, Campisi P, Witterick IJ, Chan Y. Academic benchmarks for leaders in Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery: a Canadian perspective. J Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00419-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castillo M. Measuring academic output: the H-Index. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(5):783-784. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beasley BW, Wright SM, Cofrancesco J, Babbott SF, Thomas PA, Bass EB. Promotion criteria for clinician-educators in the United States and Canada. A survey of promotion committee chairpersons. JAMA. 1997;278(9):723-728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haws BE, Khechen B, Movassaghi K, et al. Authorship trends in Spine publications from 2000 to 2015. Spine. 2018;43(17):1225-1230. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Dijk D, Manor O, Carey LB. Publication metrics and success on the academic job market. Curr Biol. 2014;24(11):R516-R517. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crowley RW, Asthagiri AR, Starke RM, et al. In-training factors predictive of choosing and sustaining a productive academic career path in neurological surgery. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(4):1024-1032. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3182367143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Venable GT, Khan NR, Taylor DR, Thompson CJ, Michael LM, Klimo P. A correlation between National Institutes of Health funding and bibliometrics in neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2014;81(3-4):468-472. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Svider PF, Lopez SA, Husain Q, Bhagat N, Eloy JA, Langer PD. The association between scholarly impact and National Institutes of Health funding in ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):423-428. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Epperson M, Gouveia CJ, Tabangin ME, et al. Female representation in otolaryngology leadership roles. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(7):1664-1669. doi: 10.1002/lary.28308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eloy JA, Svider PF, Kovalerchik O, Baredes S, Kalyoussef E, Chandrasekhar SS. Gender differences in successful NIH grant funding in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(1):77-83. doi: 10.1177/0194599813486083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arrighi-Allisan AE, Shukla DC, Meyer AM, et al. Gender trends in authorship of original otolaryngology publications: a fifteen-year perspective. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(9):2126-2132. doi: 10.1002/lary.28372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Okafor S, Tibbetts K, Shah G, Tillman B, Agan A, Halderman AA. Is the gender gap closing in otolaryngology subspecialties? An analysis of research productivity. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(5):1144-1150. doi: 10.1002/lary.28189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barinsky GL, Daoud D, Tan D, et al. Gender representation at conferences, executive boards, and program committees in otolaryngology. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(2):E373-E379. doi: 10.1002/lary.28823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rai D, Kumar A, Waheed SH, et al. Gender differences in international cardiology guideline authorship: a comparison of the US, Canadian, and European cardiology guidelines from 2006 to 2020. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(5):e024249. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.024249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Merman E, Pincus D, Bell C, et al. Differences in clinical practice guideline authorship by gender. Lancet. 2018;392(10158):1626-1628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32268-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ross L, Hassett C, Brown P, et al. Gender representation among physician authors of American Academy of neurology clinical practice guidelines. Neurology. 2023;100:e465-e472. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rai D, Tahir MW, Waheed SH, et al. National trends of sex disparity in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline Writing Committee authors over 15 years. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(2):e007578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Government of Canada IAP on RE. Tri-council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans—TCPS 2 (2018)—Chapter 2: scope and approach. April 1, 2019. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter2-chapitre2.html

- 25. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Search - CADTH Search Filters Database - Canadian Agency for drugs and technologies in health. Accessed August 16, 2022. https://searchfilters.cadth.ca/

- 27. Grewal JS. Gender distribution in otolaryngology training programs. J Otolaryngol Rhinol. 2022;8(1):116. doi: 10.23937/2572-4193.1510116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferguson BJ, Grandis JR. Women in otolaryngology: closing the gender gap. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14(3):159-163. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193203.62967.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. AAMC. 2015-2016 The State of Women in Academic Medicine Statistics. AAMC. 2016. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www-aamc-org.proxy.bib.uottawa.ca/data-reports/faculty-institutions/data/2015-2016-state-women-academic-medicine-statistics [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newman TH, Parry MG, Zakeri R, et al. Gender diversity in UK surgical specialties: a national observational study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e055516. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhattacharyya N, Shapiro NL. Increased female authorship in otolaryngology over the past three decades. Laryngoscope. 2000;110(3 Pt 1):358-361. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bergeron JL, Wilken R, Miller ME, Shapiro NL, Bhattacharyya N. Measurable progress in female authorship in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(1):40-43. doi: 10.1177/0194599812438171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eloy JA, Svider PF, Cherla DV, et al. Gender disparities in research productivity among 9952 academic physicians. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):1865-1875. doi: 10.1002/lary.24039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hill RG, Boeckermann LM, Huwyler C, Jiang N. Academic and gender differences among U.S. otolaryngology board members. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(4):731-736. doi: 10.1002/lary.28958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garstka ME, Randolph GW, Haddad AB, et al. Gender disparities are present in academic rank and leadership positions despite overall equivalence in research productivity indices among senior members of American Head and Neck Society (AHNS) Fellowship Faculty. Head Neck. 2019;41(11):3818-3825. doi: 10.1002/hed.25913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quereshy HA, Quinton BA, Mowry SE. Otolaryngology workforce trends by gender: when and where is the gap narrowing? Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43(3):103427. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zambare WV, Sobin L, Messner A, Levi JR, Tracy JC, Tracy LF. Gender representation in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery recognition awards. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(6):1200-1207. doi: 10.1177/0194599820970958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lindsay R. Gender-based pay discrimination in otolaryngology. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):989-995. doi: 10.1002/lary.29103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miller AL, Rathi VK, Gray ST, Bergmark RW. Female authorship of opinion pieces in leading otolaryngology journals between 2013 and 2018. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(1):35-37. doi: 10.1177/0194599819886119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choi SS, Miller RH. Women otolaryngologist representation in specialty society membership and leadership positions. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(11):2428-2433. doi: 10.1002/lary.23566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halderman AA, Rao A, Desai-Markowski S, et al. Gender and authorship trends in rhinology, allergy, and skull-base literature from 2008 to 2018. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(9):1336-1346. doi: 10.1002/alr.22793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eloy JA, Mady LJ, Svider PF, et al. Regional differences in gender promotion and scholarly productivity in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):371-377. doi: 10.1177/0194599813515183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Litvack JR, Wick EH, Whipple ME. Trends in female leadership at high-profile otolaryngology journals, 1997-2017. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):2031-2035. doi: 10.1002/lary.27707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meyer TK, Bergmark R, Zatz M, Sardesai MG, Litvack JR, Starks Acosta A. Barriers pushed aside: insights on career and family success from women leaders in academic otolaryngology. Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2019;161(2):257-264. doi: 10.1177/0194599819841608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim WH, Wong C, Jain SR, et al. The unspoken reality of gender bias in surgery: a qualitative systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dahlke AR, Johnson JK, Greenberg CC, et al. Gender differences in utilization of duty-hour regulations, aspects of burnout, and psychological well-being among general surgery residents in the United States. Ann Surg. 2018;268(2):204-211. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bernardi K, Shah P, Lyons NB, et al. Perceptions on gender disparity in surgery and surgical leadership: a multicenter mixed methods study. Surgery. 2020;167(4):743-750. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lu PW, Columbus AB, Fields AC, Melnitchouk N, Cho NL. Gender differences in surgeon burnout and barriers to career satisfaction: a qualitative exploration. J Surg Res. 2020;247:28-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hutchison K. Four types of gender bias affecting women surgeons and their cumulative impact. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(4):236-241. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2019-105552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hinze SW. “Am I being over-sensitive?” Women’s experience of sexual harassment during medical training. Health Lond Engl 1997. 2004;8(1):101-127. doi: 10.1177/1363459304038799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bingmer K, Walsh DS, Gantt NL, Sanfey HA, Stein SL. Surgeon experience with parental leave policies varies based on practice setting. World J Surg. 2020;44(7):2144-2161. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05447-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hamilton AR, Tyson MD, Braga JA, Lerner LB. Childbearing and pregnancy characteristics of female orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(11):e77. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, Freischlag J. Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg Chic Ill 1960. 2011;146(2):211-217. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McAlister C, Jin YP, Braga-Mele R, DesMarchais BF, Buys YM. Comparison of lifestyle and practice patterns between male and female Canadian ophthalmologists. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(3):287-290. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schroen AT, Brownstein MR, Sheldon GF. Women in academic general surgery. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2004;79(4):310-318. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200404000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Streu R, McGrath MH, Gay A, Salem B, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Plastic surgeons’ satisfaction with work-life balance: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(4):1713-1719. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318208d1b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rich A, Viney R, Needleman S, Griffin A, Woolf K. “You can’t be a person and a doctor”: the work-life balance of doctors in training-a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013897. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hill E, Solomon Y, Dornan T, Stalmeijer R. “You become a man in a man’s world”: is there discursive space for women in surgery? Med Educ. 2015;49(12):1207-1218. doi: 10.1111/medu.12818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liang R, Dornan T, Nestel D. Why do women leave surgical training? A qualitative and feminist study. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):541-549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32612-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. TCTMD.com. Trust and Transparency: From Ancient Rome to Guideline Committees. TCTMD.com. 2021. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.tctmd.com/news/trust-and-transparency-ancient-rome-guideline-committees [Google Scholar]