Abstract

Background

Establishing and maintaining relationships and ways of connecting and being with others is an important component of health and wellbeing. Harnessing the relational within caring, supportive, educational, or carceral settings as a systems response has been referred to as relational practice. Practitioners, people with lived experience, academics and policy makers, do not yet share a well-defined common understanding of relational practice. Consequently, there is potential for interdisciplinary and interagency miscommunication, as well as the risk of policy and practice being increasingly disconnected. Comprehensive reviews are needed to support the development of a coherent shared understanding of relational practice.

Method

This study uses a scoping review design providing a scope and synthesis of extant literature relating to relational practice focussing on organisational and systemic practice. The review aimed to map how relational practice is used, defined and understood across health, criminal justice, education and social work, noting any impacts and benefits reported. Searches were conducted on 8 bibliographic databases on 27 October 2021. English language articles were included that involve/discuss practice and/or intervention/s that prioritise interpersonal relationships in service provision, in both external (organisational contexts) and internal (how this is received by workers and service users) aspects.

Results

A total of 8010 relevant articles were identified, of which 158 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the synthesis. Most were opinion-based or theoretical argument papers (n = 61, 38.60%), with 6 (3.80%) critical or narrative reviews. A further 27 (17.09%) were categorised as case studies, focussing on explaining relational practice being used in an organisation or a specific intervention and its components, rather than conducting an evaluation or examination of the effectiveness of the service, with only 11 including any empirical data. Of the included empirical studies, 45 were qualitative, 6 were quantitative, and 9 mixed methods studies. There were differences in the use of terminology and definitions of relational practice within and across sectors.

Conclusion

Although there may be implicit knowledge of what relational practice is the research field lacks coherent and comprehensive models. Despite definitional ambiguities, a number of benefits are attributed to relational practices.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42021295958

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13643-023-02344-9.

Keywords: Relational practice, Enabling environments, Relational approach, Health, Social care, Justice, Education

Background

While there is not a clearly outlined definition of relational practice it is generally understood as an approach that gives priority to interpersonal relationships in both in relation to external (organisational contexts) and internal (how this is received by workers and service users) aspects. It is the foundation upon which effective interventions are made, and it forms the conditions for a healthy relational environment [1]. Notions of relational practice are not new. Systematised relational, psychosocial approaches to mental health care have a lengthy heritage, for example in the development of therapeutic communities [2]. Building on such traditions, Haigh and Benefield [3] describe the importance of relational practice in working toward a unified model of human development, with cross-sector implications. Within their work, they describe the importance of a ‘whole-person, whole-life perspective in the field of human relations’ with the quality of relational activity defined as being central to positive human outcomes and effective service provision [3]. The term relational practice is increasingly described and applied across different service contexts, including health, education, criminal justice and social work. The ways in which relational practice is described varywidely but include Psychologically Informed Environments, Enabling Environments and Psychosocial Environments, as well as other environments and work practices that use the relational practice label to describe their provision.

The importance of relationships and ways of connecting and being with others cannot be underestimated with respect to positive health, wellbeing and other outcomes (such as mental health recovery, overcoming social challenges, rehabilitation in criminal justice services and learning). However, practitioners, people with lived experience, academics and policy makers have not yet articulated a shared understanding of relational practice [3]. Consequently, there is a potential for interdisciplinary and interagency miscommunication, as well as a risk of policy and practice being disconnected. Further, inconsistency in terminology between disciplines is likely to result in separate knowledge bases being developed in parallel, complicating and compromising transfer of evidence into practice across fields.

While there are some systematic or scoping reviews of relational practice in specific service provision, such as acute care settings [4] or after-school provision [5], to date, there has been no comprehensive synthesis or mapping of the extant relational practice literature, across disciplines. Largely absent from the literature are reviews that focus on organisational practice using relational approaches, rather than focused on individual and/or therapeutic relationships. This scoping review maps and combines literature across a range of disciplines (Health, Education, Criminal Justice, and Social Care/Work) to provide clarity and direction, charting and summarising existing understandings. As we aimed to examine evidence from disparate or heterogeneous sources, rather than seeking only the best evidence to answer a specific question, a scoping review methodology was considered appropriate [6]. This methodology enables an examination and synthesis of the extent, range and nature of research on relational practice across health, criminal justice, social care/work and education, to inform future systematic reviews, and to identify gaps in the literature [7]. The four chosen sectors (health, criminal justice, social care/work and education) were included as these are all people facing public service contexts where relationships and relational practices are of crucial importance. We used the service provision being provided or discussed in the papers as criteria for inclusion rather than academic discipline.

The review focuses specifically on the relational practice used in an organisational context rather than in one-to-one approaches (i.e., individualised therapeutic approaches). We used the following definition: relational practice from a systemic and organisational perspective, defined as practice and/or intervention that prioritises interpersonal relationships in service provision, in both external (organisational contexts) and internal (how this is received by workers and service users) aspects. This approach was adopted owing to the ambitious and broad scope of this review, but also to add a focus as there is a wide range of relational approaches that are focused upon individualised interventions, such as therapeutic relationships and other evidence-based therapeutic/psychological approaches, but less is known about relational approaches at an organisational level. Within the review, we also scoped the extant literature for any reported impacts and benefits of relational practice.

Research question

How is relational practice used, defined and understood across different academic disciplines, professional practices and contexts, focussing on Health, Education, Criminal Justice, and Social Care/Work, and what are its reported impacts and benefits?

Method

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping reviews [6]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) is provided in Additional file 1. Prior to commencement, the review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: PROSPERO2021CRD42021295958) and is available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021295958.

A multi-disciplinary core research team was brought together made up of academics, clinicians and people with lived experience of service provision with representation from health, education, social care/work and criminal justice experiences. A steering group committee was also convened with similar representative experience. This group provided oversight of the project, informed by subject matter expertise complimenting cross-sector and occupational/lived experience among the membership and supported with the search strategy, identifying search terms and the synthesis of the literature.

Search strategy

Searches were conducted on eight electronic databases (EPIC, SocIndex, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Education Abstracts, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Ovid MEDLINE and Criminal Justice Database) on 27 October 2021. Keywords for database searches included the following:

Relational focussed OR relational based OR relational work OR Relational social work OR Relational centred OR Relational centered OR relational practice* or relational informed OR relational theory OR relational approach* OR relational perspective* OR relational model OR relational strategy or relational strategies OR relational environment* or relational justice* OR relational education* or relational health OR relational therapy OR relational thinking OR relational inquiry OR relationship focussed OR relationship based practice OR relationship informed OR interpersonal system OR interpersonal environment* OR interpersonal practice OR interpersonal approach* or interpersonal perspective OR interpersonal strategy or interpersonal strategies OR psychosocial environments OR enabling environments

The full search strategy for each database is included in Additional file 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review are displayed in Table 1. In order to encompass a broad range of approaches, the relational practice was broadly defined as practices and/or interventions that prioritise interpersonal relationships in service provision, in relation to both external (organisational contexts) and internal (how this is received by workers and service users) aspects. Articles were included where relational practice was seen as the foundation upon which effective interventions are made and form the conditions for a healthy relational environment. Because the focus of this review was on organisational processes, articles exclusively about the therapeutic relationship and/or therapeutic approaches were only included if they informed a systemic and organisational approach.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Any patients or service users without age restriction (e.g., including children and youth) accessing face-to-face health, education, justice or social care/social work | Computer-facing services—e.g., virtual platform interventions (Telecare, etc.), artificial intelligence, relational data bases. Human–computer interaction |

| Concept | Relational practice from a systemic and organisational perspective, defined as practice and/or intervention that prioritises interpersonal relationships in service provision, in relation both to external (organisational contexts) and internal (how this is received by workers and service users) aspects. |

Studies/articles purely about the therapeutic relationship/alliance Studies of interventions/work practices/ Service Provision where the focus is not specifically on the relational component Studies/articles about an evidence-based or therapeutic interaction linked to a psychological intervention or focussed solely on group/one-to-one interactions |

| Context | People facing services across and the following sectors: Education (including any type of education provision, i.e. school, college, university), Health (any health service), Criminal Justice (e.g. Liaison and Diversion, Prisons, Probation, Offender Personality Disorder, YOT, Police, Special Hospital), and Social Care/Work (including third sector organisation provision) | Any services/organisations outside of the 4 defined sectors. For example, studies examining exclusively business and work focussed. |

All types of studies (qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods), conceptual or theoretical papers/reports and all types of reviews (i.e., systematic, scoping, meta-analysis) were included, reported in peer-reviewed journals, grey literature and book and book chapters fully available online. Only articles published in English were included; however, there was no limit on the country of origin. Only articles published from 2000 were included to focus on current/recent practice and service delivery.

Study/paper selection

All records identified from the database searches were downloaded to EndNote and duplicates were removed using Systematic Review Accelerator [8]. Any remaining citations were transferred to Rayyan for screening, and any further duplicates identified were removed. Title and abstract screening were conducted in Rayyan independently by five reviewers (PB, RN, MM, GL, JP), with 20% of the papers screened independently by at least two reviewers. Inter-rater reliability was 84.09% at the title and abstract stage. Once title and abstract screening were complete, selected full-text papers were sourced and checked against inclusion criteria by six reviewers independently (PB, RN, MM, GL, JP), with at least 20% of the papers screened by at least two reviewers. An inter-rater reliability of 85% was achieved at the full-text screening stage. Reasons for exclusion were noted at this stage. Agreement at all stages was made by consensus, and any disagreements regarding inclusion were discussed with a third member of the research team where necessary.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from all selected texts using a data extraction sheet designed by the research team in collaboration with the steering group committee. The data extraction tool was piloted and refinements made. Following this authors completed data extraction for a sample of 10 studies as sufficient agreement was reached the authors then applied to tool to the remaining studies independently. Data extraction included key study/article characteristics (e.g., country), people facing service type, sector type, aims of study, study/article type, including key information for empirical studies (i.e., participants, design, data collection methods), underlying theories, key terms and definitions of relational practice and reported impacts and benefits. The research team collectively carried out calibration testing of the tool with a sample of articles prior to the assignment of independent data extraction of research team members [9].

Data synthesis

Data extracted from selected articles was charted, and a mapping of the scope of the literature was conducted using narrative synthesis. Narrative synthesis is an often-used approach within systematic and scoping study literature reviews. This approach enables the synthesis of large bodies of literature and looks to explore the relationships in the dataset collected and analyse commonalities, conflicts and relationships that assist us to reach conclusions and make recommendations for practice [10]. Consultation with the steering group committee throughout the data synthesis stage supported the interpretation and synthesis of the review findings.

Results

The results of the systematic search and screening process are displayed in a PRISMA flow chart (see Fig. 1). A total of 11,490 articles were initially identified from database searches. After the removal of duplicates, 8010 were retained, and 521 remained for full-text review. Overall, 158 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in the synthesis. Table 2 displays the characteristics of the studies/articles included.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Table 2.

Characteristics of included articles/studies

| First author | Year | Countrya | Service users | Professionals | Sector type | Specific service type | Aim of study/paper | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggett [11] | 2019 | UK | Child and Adolescents Mental Health (CAMHS) service users | Clinical psychologists | Health | CAMHS | Propose a model of risk management that moves away from an overemphasis on ‘technical’ approaches to ensuring that this is balanced by organisations supporting ‘relational’ approaches and further, ‘relational-collaborative’ approaches | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Anderson [12] | 2016 | US | Care home residents | Care aides | Health | Nursing homes | Exploring the complexities of care; working environments; and knowledge, skills, and efforts of care aides who work in nursing homes. | Qualitative |

| Andrews [13] | 2018 | Canada | Mothers with substance abuse | Clinicians/social workers/academics | Health | Multi-sector including health, social care | Explore mothers’ service use at breaking the cycle, an early intervention and prevention program for pregnant and parenting women and their young children in Toronto, Canada. | Quantitative |

| Andrews [14] | 2019 | Canada | Community-based projects | Academic researchers | Health | Community projects supporting vulnerable families | Describes two approaches integrated into a multiyear, multiphase research and evaluation initiative supporting the health and well-being of vulnerable families: (1) a relational approach and (2) a trauma-informed approach; specific strategies and key considerations used are outlined. |

Opinion Piece/theoretical argument |

| Appleby [15] | 2020 | New Zealand | Young offenders | Social workers | Criminal justice | Youth offending and mental health provision | Focuses on the social work contribution to service improvement by reflecting on the establishment of the first youth forensic forum in Aotearoa New Zealand, to improve mental health assessment experiences for young people within youth justice residences. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Arnkil [16] | 2015 | Finland | Psychotherapy clients and students | Psychotherapy/family therapists | Health | Mental health | An analysis of the use of open dialogicity in psychotherapy and juxtaposes it with education in order to find common dialogical elements in all relational practices | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Asakura [17] | 2018 | Canada | Student social workers | Experienced social workers | Social care/work | Field work coordination for trainee social workers | Conceptualizes field coordination as a negotiated pedagogy in which the coordinators navigate complex and often competing needs among students, field agencies, and social work practice. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Bainbridge [18] | 2017 | UK | Female offenders | Forensic clinicians | Criminal justice | Women in custody | Considers the development of the therapeutic environment of a PIPE (psychologically informed planned environments) Unit and in particular its translation for women in custody | Qualitative |

| Barrett-lennard [19] | 2011 | Australia | Psychotherapy clients | Psychotherapists | Health | Mental health | Stresses the connectedness of human lives, and views our life process and consciousness as relational in its essence | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Barrow [20] | 2021 | UK | Young people who have experienced child sexual exploitation (CSE) | Clinical psychologists | Health | Mental health, young people, CSA/CSE | Service evaluation: explored viewpoints of key stakeholders, such as young people and frontline staff, about CSE services | Quantitative |

| Bennett [21] | 2017 | UK | Offenders | Prison governor, clinical service head | Criminal justice | Prison-based democratic therapeutic communities | Describe the work of HMP Grendon, the only prison in the UK to operate entirely as a series of democratic therapeutic communities and to summarise the research of its effectiveness. | Case study/report |

| Bennett [22] | 2018 | UK | Offenders | Prison governor, clinical service head | Criminal justice | Prison-based democratic therapeutic communities | Consider how the more positive social climates found in democratic therapeutic communities are constructed and how these practices can be replicated in other settings | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Berzoff [23] | 2006 | US | Social work students | Lecturers | Education | Masters course in end-of-life care for social work students | Describes the first post-master’s program in the US in end-of-life care for social workers | Case study/report |

| Bjornsdottir [24] | 2018 | Iceland | Older persons receiving care at home | Senior nurses/academics | Health | Home care nursing for elderly people | Enhance knowledge and understanding of the nature of home care nursing practice. | Qualitative |

| Blagg [25] | 2018 | Australia | Young people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) | Criminology academics | Criminal justice | Youths with FASD in the justice system | Reports on a study undertaken in three Indigenous communities in the West Kimberley region of Western Australia (WA) intended to develop diversionary strategies for young people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). | Mixed methods |

| Blumhardt [26] | 2017 | New Zealand | Children and family | Academics; anti-poverty non-governmental organisation | Social care/work | Vulnerable, excluded families in poverty | Posits the radical practice of anti-poverty organisation ATD Fourth World in England (where child protection is characteristically risk-averse, individualised and coercive), as an alternative for work with families experiencing poverty and social exclusion | Qualitative |

| Bøe [27] | 2019 | New Zealand | Children in child protection institutions | Milieu therapists | Social care/work | Child protection institutions | Examine factors described by milieu therapists as significant for relational work with youth placed in institutions | Qualitative |

| Boober [28] | 2005 | US | Incarcerated women (ready for parole) | Staff members involved in the transition programme | Criminal justice | Prison context, re-entry to society | Describe the Maine Re-entry Network transition program at the Women's Center in Windham, Maine, | Case study/report |

| Booth [29] | 2012 | US | Adult learners | University lecturers | Education | University | Discuss the characteristics of working with adult learners relating to interpersonal boundaries | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Boschki [30] | 2005 | Germany | Student | Teacher | Education | Religious education (school context) | Discusses the possibilities and chances of a relational approach to religious education | Critical/narrative review |

| Bridges [31] | 2014 | UK | Older people | Nurses | Health | Elderly residential care | Propose the use of a novel implementation programme designed to improve and support the delivery of compassionate care by health and social care teams. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Bridges [32] | 2017 | UK | Acute care patients | Nursing staff, managers | Health | Nursing acute care | Identify and explain the extent to which Creating Learning Environments for Compassionate Care (CLECC) was implemented into existing work practices by nursing staff, and to inform conclusions about how such interventions can be optimised to support compassionate care in acute settings | Qualitative |

| Bridges [33] | 2020 | Various | Elderly inpatients | Nursing staff | Health | Elderly inpatient hospital care | To synthesise qualitative research findings into older people’s experiences of acute healthcare | Systematic review |

| Brown [34] | 2018 | Ireland | Children and young people in care | Residential care home staff | Social care/work | Residential childcare | Explores the views and experiences of residential care workers regarding relationship‐based practice. | Qualitative |

| Bunar [35] | 2011 | Sweden | Parents | Teachers, principals | Education | Multicultural urban schools | To outline an argument that a relational approach is needed in multicultural schools | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Burchard [36] | 2005 | UK | Families | Community nurses | Health | Family nursing | A comparison of ethical principles relating to research, family nursing practice, and Foucault’s meta-ethical framework is offered | Critical/narrative review |

| Byrne [37] | 2016 | UK | Young offenders | Social workers, youth justice workers | Criminal justice | Youth criminal justice | Consider and explore the principles that should inform a positive and progressive approach to conceptualising and delivering youth justice. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Cahill [38] | 2016 | Ireland | Young people in care | Residential care staff | Social care/work | Residential childcare | Exploring relationship-based approaches in residential childcare practice, from the perspectives of both residential childcare workers and young care leavers | Qualitative |

| Campbell [39] | 2012 | India, South Africa | Community out-patients | Nurses | Health | Home-based nursing (AIDS) | Explore transformation communication by presenting a secondary analysis of two contrasting case studies using peer education with highly marginalised women in HIV/AIDS management. | Case study/report |

| Carpenter [40] | 2015 | US | Students, faculty members | Higher education leaders | Education | University | Examine the strategic organization-public dialogic communication practices of universities in the USA | Qualitative |

| Celik [41] | 2021 | Germany | Students | Teachers | Education | Secondary school | Explain a relational framework that ties the concepts of institutional habitus, field and capital, and investigate how a secondary school improves the educational engagement of working-class, second-generation Turkish immigrant youth in Germany. | Case study/report |

| Cheung [42] | 2017 | Hong Kong | Clients | Social workers | Social care/work | Social work | Drawing from the experiences of community development projects in rural Hong Kong, discuss how guanxi among social workers, clients and other stakeholders in Chinese communities might challenge the professionalism of social work and breach the boundaries of social work relationships. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Cleary [43] | 2012 | Various | Mental health inpatients | Mental health nurses | Health | Acute mental health inpatient care | Identify, analyse and synthesize research in adult acute inpatient mental health units, which focused on nurse-patient interaction. | Systematic review |

| Cleland [44] | 2021 | UK | Parent involvement with students | Teachers | Education | Compulsory education only | Explores examples of parent-school relations which impact positively on parents, regarding empowerment, parent voice and social capital. | Systematic review (meta-ethnography) |

| Coleman [45] | 1999 | Greece | Families | Training teachers | Education | Early years education | Justifying a family involvement training course | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Collier [46] | 2010 | UK | Older people with mental health difficulties | Mental health professionals | Health | Older Persons Mental Health | Exploration of ethics in the context of older persons mental health care | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Collinson [47] | 2019 | UK | Substance misuse | Substance misuse workers | Health | Recovery and Substance Misuse | Shares an asset-based community model highlighting the strong dynamic relationship between the key components of recovery capital and represents a foundation for community and therapeutic-level interventions for building recovery capital. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Conradson [48] | 2003 | UK | Community centre service users | Community centre workers | Social care/work | Community drop-in centres—Brexton House Bristol | Explores the ways in which drop-in centres may at times function as spaces of care in the city, focussing upon social relations within the drop-in space and the various subjectivities that emerge in this relational environment. | Qualitative |

| Cranley [49] | 2020 | Canada | Older residents | Nursing staff | Health | Older persons residential Care | Explore shared decision-making among residents, families and staff to identify relevant strategies to support shared decision-making in LTC. | Qualitative |

| Creaney [50] | 2014 | UK | Youth services | Youth workers | Criminal justice | Youth Justice | Critical Review of the “position of relationship-based practice” in youth justice, in particular looking at how “effective programmes” seem to have been given heightened importance over “effective relationships” | Critical/narrative review |

| Creaney [51] | 2015 | UK | Youth services | Youth workers | Criminal justice | Hard to engage young people | Examination of how youth justice practice could become more participatory and engaging, particularly with those who are "involuntary clients" or in other words difficult to engage. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Creaney [52] | 2020 | UK | Youth services | Youth workers | Criminal justice | Youth Justice | Explore young people’s experiences of youth justice supervision with particular reference to the efficacy of participatory practices | Qualitative |

| Cuyvers [53] | 2013 | Belgium | Social work undergraduates | Social work lecturers | Education | Social work education | Describe a relational practice approach embedded in appreciative inquiry in social work education | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Daly [54] | 2020 | UK, New Zealand | Students | Teachers | Education | Schools and Systems | Examines schools as ‘systems’ in which teachers learn; conceptualising schools from an ecological perspective, the relations among all stakeholders are brought into focus. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Daniel [55] | 2018 | Canada | Children and young people | Youth workers | Social care/work | Children and youth services | Expand upon Garfat’s [56] exposition and ask that we rethink our understandings and practice in the field of CYC when we incorporate sites of diversity. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Davies [57] | 2019 | UK | Offenders | Probation and prison | Criminal justice | Probation and Prison | Examines the progress in the introduction of the Enabling Environments (EE) standards across seven sites (four Approved Premises and three prisons) | Case study/report |

| Deery [58] | 2008 | UK | Prenatal and postnatal women/birthing people | Midwifery | Health | Community-based Midwifery | Examines community midwives’ experience of linear time during the third phase of a 3-year action research study, seeking to compare and contrast the ways in which they experienced this temporal framework, individually and organizationally, in their clinical practice. | Qualitative |

| Defrino [59] | 2009 | US | Patients | Nurses | Health | Nursing not specific | Discusses the theory of the relational work of nurses derived from a psychodynamic theory of the relational practices of women and the workplace. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Dewar [60] | 2013 | UK | Older people, staff and relatives | Medical staff not defined | Health | Acute hospital setting | Actively involve older people, staff and relatives in agreeing a definition of compassionate relationship-centred care and identify strategies to promote such care in acute hospital settings for older people. | Qualitative |

| Doane [61] | 2002 | Canada | Student nurses | Nursing lecturers | Education | Nursing education | Discusses the pedagogical value of interpretive inquiry for the teaching–learning of relational practice. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Doane [62] | 2007 | Canada | Patients | Nurses | Health | General nursing | Critically examine the concept of obligation in nursing practice, and using a relational understanding, suggest 3 obligations underlying nursing relationships, proposing that responsive, compassionate, therapeutic relationships, and ethical and competent nursing practice are integrally connected, and that relational inquiry can support the enactment of both. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Dupuis [63] | 2012 | US | People living with dementia | Staff providing dementia care | Health | Dementia care | Description of new relational approach, that views persons with dementia as equal partners in dementia care, support and formal services: ‘authentic partnerships. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Durocher [64] | 2019 | Canada | Older adults | Healthcare professionals | Health | Older adult inpatient rehabilitation unit | To discern relational approaches adopted by families in planning for the discharge of older adults from inpatient settings and how they inform practice in discharge planning with older adults. | Case study/report |

| Ellery [65] | 2010 | New Zealand | Secondary school children years 7–11 | Teachers | Education | Secondary school | Discover how RTLB (Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour) can effectively support secondary teachers to enhance inclusive classroom practices. | Qualitative |

| Elliott [66] | 2011 | Australia | Members of public (victims of crime) | Police | Criminal justice | Policing | Test a relational model of authority in victim-police interactions and examine what perceived antecedents of procedural justice in contacts with the police mean for victims of crime. | Mixed methods |

| Elwyn [67] | 2021 | US | Patients | Healthcare professionals | Health | Healthcare in general | Present an argument that the process commonly described as shared decision making involves work that is cognitive, emotional, and relational, and particularly if people are ill, should have the underpinning goal of restoring autonomy. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Emmamally [68] | 2018 | South Africa | Patients and their families | Emergency dept professionals | Health | Emergency care | To describe the adherence of emergency healthcare professionals to family-centred practices in some emergency departments | Quantitative |

| Emmamally [69] | 2020 | South Africa | Patients and their families | Emergency dept professionals | Health | Emergency care | Describe Health Care Providers’ perceptions of relational practice with families in emergency department contexts | Qualitative |

| Emmamally [70] | 2020 | South Africa | Families | Emergency dept professionals | Health | Emergency care | To describe families’ perceptions of relational practice when interacting with health care professionals in emergency departments in the South African context. | Qualitative |

| Ferguson [71] | 2020 | UK | Service users | Social work teams, family support workers | Social care/work | Child protection | Examine what social workers actually do, especially in long-term relationships. | Mixed methods |

| Finkelstein [72] | 2005 | US | Women with alcohol/drug use and mental health disorders with histories of violence | Women Embracing Life and Living (WELL) Project providers | Health | Substance use/violence prevention | Describe the organisation and delivery of a service based on the relational model of women’s development | Case study/report |

| Fitzmaurice [73] | 2015 | US | Academic staff/university | Academic staff/university | Education | University | Describe a program of faculty support that places trust and community-building at the center of its efforts. | Case study/report |

| Fortuin [74] | 2007 | US | Women offenders | Corrections and voluntary agency staff | Criminal justice | Rehabilitation of offenders | Describes transition, reunification and re-entry programme for female offenders in Maine | Case study/report |

| Frelin [75] | 2014 | Sweden | Secondary school students | Teachers and other staff | Education | Secondary school | Introduces a theoretical framework for studying school improvement processes using concepts from spatial theory, in which distinctions between mental, social and physical space are applied makes for a multidimensional analysis of processes of change. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Frost [76] | 2008 | UK | Social care service users | Social workers | Social care/work | Social work services, social work education, research | Examining how the current re-emergence of psychosocial theory, mainly emanating from sociology, is useful for informing social work theory. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Gharabaghi [77] | 2008 | Canada | Young people and families | Child and youth care practitioners | Social care/work | Child and youth care | Explores the professional issues of relationships within child and youth care practice. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Gharabaghi [78] | 2008 | Canada | Young people and families | Youth workers | Social care/work | Youth work | Highlight five dialectical processes within relational youth work in the hopes that we might collectively engage not only in the celebration of our concept, but also in a serious contemplation of its pitfalls. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Gill [79] | 2020 | UK, US | Students | Teachers | Education | Schools | Describe a relational perspective for educational evaluation | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Giller [80] | 2006 | US | Various service provider practitioners | Educators | Education | Practitioner education curriculum development | Discuss how, Risking Connection teaches the philosophy of relational therapy and how collaborative relationships have nurtured the development, application, and follow-up of Risking Connection. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Goddard [81] | 2021 | US | Nursing students | Nurse educators | Education | Nurse education | A call to action for trauma awareness in nursing education, aiming to guide nursing educators, researchers, and leaders in support, retention, and building foundational skill sets in a now traumatized nursing student population. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Grimshaw [82] | 2016 | UK | Older adults | Health and social care workers | Health | Older peoples care | Scoping literature review of the H&SC and broader management literature to identify and extract important behaviours, processes and practices underlying the support of high-quality relationships. | Scoping review |

| Haigh [3] | 2019 | UK | Service users | public sector workers | All sectors | General health, justice, social care and education services | To agree a better map of human development by using an iterative process of consultation with professionals and specialists in relevant disciplines, and service users | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Haigh [2] | 2013 | UK | Mental health service users | Mental health professionals | Health | Mental health care | Describe the necessary primary emotional development experiences for healthy personality formation. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Hibbin [83] | 2019 | UK | School children | Teacher | Education | Primary and secondary schools | Consider how provision for children with SEND (Special Educational Needs and Disabilities) is conceptualised, operationalised and enacted | Qualitative |

| Holt [84] | 2018 | UK | Children and their families | Social workers | Social care/work | Social work with children and families | Outline how reforms to the family justice system limit the potential for social workers to engage in relationship-based work with children and their families. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Horowitz [85] | 2015 | US | Psychiatric inpatients | Mental health nurses | Health | Mental health hospitals | Argues for trauma-informed, person-centred, recovery-focused (TPR) care in psychiatric hospitals | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Howitt [86] | 2020 | Australia | Community members on a public housing estate | Salvation army workers and volunteers | Social care/work | Community development | Explore the transformative potential of relational, rather than transactional, community development practices | Qualitative |

| Ingólfsdóttir [87] | 2021 | Iceland | Young disabled children and their families | Professionals providing specialised services | Social care/work | Services for disabled children and their families | Views and experiences of professionals providing specialised services to disabled children and their families. | Qualitative |

| Jennings [88] | 2018 | US | Patients | Clinical staff | Health | Bioethics | To advance the discussion of relational approaches within bioethics by an interpretive analysis of the concept of solidarity and the concept of care when seen as modes of moral and political practice | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Jindra [89] | 2020 | US | Residents/community members | Community workers | Social care/work | Anti-poverty non-profit organisations | Critique of the precariousness and promise of relational work in anti-poverty organisations | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Kanner [90] | 2005 | US | Adolescents with emotional, behavioural and educational issues | Teaching and support staff | Education | Educational setting for adolescents with emotional, behavioural and educational issues | Description of the relational approach of the Kanner Academy drawing to the relational ethic that derives from Gestalt field theory. | Case study/report |

| Kerstetter [91] | 2016 | US | School children | Teaching and support staff | Education | Public charter schools—'no excuses' schools | Examines the extent to which authoritarian discipline systems are necessary for success at “no excuses” schools, drawing upon qualitative research at a strategic site | Qualitative |

| Kippist [92] | 2020 | Australia | Renal care patients | Carers and staff | Health | Regional dialysis centre | Presents findings from the first of a two-part study exploring user experiences of brilliant renal care within the Regional Dialysis Centre in Blacktown (RDC-B) | Qualitative |

| Kirk [93] | 2017 | UK | Children | Social workers and team managers | Social care/work | Child Protection | Describes and evaluates an approach to social work practice, which divides levels of risk within the child in need category enabling adequate, coordinated support and oversight to be provided | Qualitative |

| Kitchen [94] | 2009 | Canada | children | Teachers | Education | Elementary school | Examines how a respectful and relational approach to teacher development can result in deep and sustained professional growth and renewal. | Case study/report |

| Kong [95] | 2020 | Hong Kong | Women who have left abusive partners | Social work practitioner-researcher | Social care/work | Domestic violence service (crisis intervention) | Provide insights for improving the local domestic violence service, whose main focus is on crisis intervention. | Qualitative |

| Kranke [96] | 2019 | US | Veterans | Military social workers | Social care/work | Veteran reintegration support | Propose a practice paradigm shift among veterans that would also focus on the attributes of “sameness” rather than differentness alone. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Kuperminc [97] | 2019 | US | Boys and Girls Clubs of America members | Programme staff | Education | After school settings | Examined associations among programmatic structures, workplace and workforce characteristics, and relational practices of program staff as they relate to young people’s ratings of their experience attending local clubs. | Quantitative |

| Kutnick [98] | 2014 | Hong Kong | School children | Teachers | Education | Primary school | Effectiveness of a relation-based group work approach adapted/co-developed by HK primary school mathematics teachers | Quantitative |

| Larkin [99] | 2020 | UK | Unaccompanied young females (UYFS) | Social workers | Social care/work | Care for female under 18 unaccompanied asylum seekers | Through a study of how UYFS and practitioners in England experienced and constructed each other during their everyday practice encounters, the potential of the practice space for creating mutual understandings and enabling positive changes is discussed | Qualitative |

| Laschinger [100] | 2014 | Canada | Patients | Nurses | Health | Hospital & community | Test a model linking a positive leadership approach and work-place empowerment to workplace incivility, burnout, and subsequently job satisfaction | Quantitative |

| Lees [101] | 2016 | UK | Workers in therapeutic communities or similar services | Senior TC clinicians, group psychotherapists | Health | Training for workers in TCS, enabling environments and similar | Describe transient therapeutic communities (TCS) and their value for training. This is a descriptive account which includes the findings of two field study evaluations, and direct participant feedback. | Case study/report |

| Lefevre [102] | 2019 | UK | Children at risk/being sexually exploited | Various (police, social work) | Social care/work | Child protection | Analysis of data from a 2-year evaluation of the piloting of a child-centred framework for addressing child sexual exploitation (CSE) in England to illuminate the dilemma between control and participation, and strategies used to address it | Qualitative |

| Leonardsen [103] | 2007 | Norway | Social work service users | Social workers | Social care/work | General social work | Differentiate individual vs. relational approaches to empowerment and argue for changes to social work standards/education | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Lindqvist [104] | 2014 | Sweden | Students | Teachers | Education | Primary/secondary school | Examine the strategies used by teachers whose practice was considered inclusive | Qualitative |

| Ljungblad [105] | 2021 | Sweden | Children | Teachers | Education | Schools | Explaining Pedagogical Relational Teachership | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Llewellyn [106] | 2012 | Canada | Citizens of war-affected countries | People in peace keeping institutions | Criminal justice | International peace building | Setting out a theory of relational justice | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Lloyd [107] | 2015 | UK | Schools and families | Teachers | Health | Primary school obesity intervention | Overview of the conceptualisation and development of a novel obesity prevention intervention, the Healthy Lifestyles Programme | Case study/report |

| Macritchie [108] | 2019 | UK | Care experienced children | Volunteer mentors | Education | Primary and secondary school | Describe MCR pathways—mentoring programme for care-experienced young people | Case study/report |

| Markoff [109] | 2005 | US | Women with SU/MH disorder and trauma histories | Senior health providers | Health | Substance abuse/mental health | Describe the principles and strategies used to document and evaluate WELL Project implementation, and evidence of resulting systems change to support the delivery of integrated and trauma-informed services for women with co-occurring substance abuse and mental health disorders and histories of violence | Case study/report |

| Mccalman [110] | 2020 | Australia | Children from remote indigenous communities | Healthcare and wellbeing support staff | Health | Boarding school health and wellbeing service | Examines how boarding schools across Queensland promote and manage healthcare and wellbeing support for Indigenous students. | Qualitative |

| Mccarthy [111] | 2020 | US | Social work students | Social work educators | Education | University | Explores methods that instructors can take to support students’ developmental growth through the concept of intersubjectivity within a relational theory framework. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Mcdonald [112] | 2013 | US | Trainee teachers | Teacher educators | Education | University | Examine how placements in community-based organisations enable trainee elementary school teachers to practice relationally | Qualitative |

| Mcmahon [113] | 2011 | US | Patients | Nursing professionals | Health | General nursing | Propose a mid-range theory of nursing presence, identify development opportunities to improve student nurse use of presence as a relational skill | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Mcpherson [114] | 2018 | Australia | Children | Social workers, psychologists, and managers | Social care/work | Residential childcare | Reports on a study of a program response to children who have experienced trauma and are placed in out-of-home care | Mixed methods |

| Meer [115] | 2017 | South Africa | Women with intellectual disabilities | Service providers | Social care/work | Non-governmental disability service providers | Describes the intricacy of familial relationships for women with intellectual disabilities in South Africa who experience gender-based violence | Qualitative |

| Miller [116] | 2020 | UK | Adult carers | Service providers | Social care/work | Carer support | Explore practitioners’ views about the role of the narrative record in holding memories, recognition of capable agency, clarifying possibilities for action, restoration of identity and wellbeing. | Qualitative |

| Moore [117] | 2021 | UK | Service users | Adult social care services | Social care/work | Local Authority (Adult Social Care) | Using a case study of a large UK local authority adult care department, describes a new practice model, moving away from transactional practice and promoting creative, autonomous, and relationship-based practice | Case study/report |

| Moore [118] | 2020 | UK | Mental health service users | Peer support workers | Health | NHS Mental Health Services | Explore what NHS mental health professionals value about the peer support worker role | Qualitative |

| Motz [119] | 2007 | Canada | Women who abuse substances—pregnant or with children | Child welfare, substance use treatment, health and medical, and children’s service sectors | Health | Substance Misuse support service | Describing an early identification, prevention and treatment program for pregnant and parenting women who abuse substances (Breaking the Cycle) | Case study/report |

| Motz [120] | 2019 | Canada | Women who abuse substances with young children | Child welfare, substance use treatment, health and medical, and children’s service sectors | Health | Substance Misuse | Using a developmental-relational framework to understand women who abuse substances, their development and how this relates to early childhood experiences of violence in relationships | Case study/report |

| Mulkeen [121] | 2020 | Ireland | General social care service users | Social care workers | Social care/work | General social care | Discussing how concepts of care (including its relational components) are operationalised in social care workers standards | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Munford [122] | 2020 | New Zealand | Children | Social workers | Social care/work | Youth services | Examine the experience of shame and recognition of vulnerable young people during transition to adulthood | Qualitative |

| Murphy [123] | 2012 | UK | Students | HE lecturers | Education | University | Arguing for a new pedagogy of higher education | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Muusse [124] | 2021 | Netherlands | Service users | Community mental health team | Health | Community mental health team | Describe dilemmas related to multiple perspectives on good community mental health care, using multiple stories about Building U. We unravelled the stories as different modes of ordering care that are present in the daily discussions about the work of the CMHT. | Qualitative |

| Muusse [125] | 2020 | Italy | People with mental health conditions | Providers of mental health care and other support to people with mental health conditions | Health | Mental health in Trieste (minimal impatient provision) | Exploring good care in the context of Trieste deinstitutionalised mental health care system/services | Qualitative |

| Nelson [126] | 2011 | New Zealand | Children and families | Nurses | Health | Public health | Describe the community-based nursing service provided in Wellington for Children and Families | Case study/report |

| Nepustil [127] | 2021 | Czech Republic | People affected by addiction | Psychologists | Health | Addiction services | Describe an approach that uses a more relational perspective when working with people experiencing addiction | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Newbury [128] | 2012 | Canada | Providers and recipients of community provision | Course provider | Education | Two-day continuing education course on community development | Reflection on the experience of developing and delivering a two-day continuing education course on community development, and potential of relational practice when self is understood as relationally constituted, and change is understood as an ontological and collective process. | Case study/report |

| Nicholson [129] | 2021 | UK | Offenders | Probation | Criminal justice | Probation co-operatives 'The Preston Model' OPD Pathway | Present a workable, cooperative, democratised organisational form for offender resettlement allied to alternative approaches for realising fairer local economic justice. | Case study/report |

| Noam [130] | 2013 | US | Students in an after-school club | Teachers | Education | After school care | Discuss the role of and challenges with youth development-orientated educators in after-school club provision in schools in building relationships with students. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Noseworthy [131] | 2013 | New Zealand | Women prenatal and postnatal | Midwives | Health | Midwifery | Critically explores current issues around decision-making and proposes a relational decision-making model for midwifery care. | Qualitative |

| O'Meara [132] | 2021 | UK | Offending women | Offending managers | Criminal justice | Probation | To explore women’s experiences of criminal justice systems to inform the development of guidance on working with women. | Qualitative |

| Ould brahim [133] | 2019 | Canada | Patients with chronic pain | Nursing staff | Health | Self-management of care | Review predominant critiques of self- management and the traditional individualistic view of autonomy, proposing a relational approach to autonomy | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Pahk [134] | 2021 | South Korea | Solitary seniors | Peer support workers | Social care/work | Peer-support Services | Presents a relational framework for peer-support design and its application to two existing peer-support services for solitary seniors to understand the multi-faceted issue of social support | Mixed methods |

| Parker [135] | 2002 | US | Patients | Care workers | Health | Teaching hospital | Advances a model of workgroup-level factors that influence relational work, based on data from case studies of two caregiving workgroups. | Case study/report |

| Plamondon [136] | 2018 | Canada | Health care system users | Health care system providers | Health | Formal and informal providers of health care systems as well as community-based organizations | Outline the deliberative dialogue method and reflect on how these practices can help establish both processes and outcomes that can affect meaningful change in health systems | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Porter-samuels [137] | 2019 | Tonga | Students | Teachers | Education | Five schools which form a Kahui Ako | Insights from a group of predominantly pakeha teachers grappling with culturally responsive relational practice (CRRP), in a time and environment where external factors can affect self-efficacy and limit personal agency. | Mixed methods |

| Pozzuto [138] | 2009 | US | Social work service users | Social workers | Social care/work | General social work | Review the literature that calls for the incorporation of relational theory into social work practice involving two strands: the psychoanalytic and the feminist | Critical/narrative review |

| Quinn [139] | 2015 | UK | Students | School leaders | Education | School context not mentioned | Evaluation of a reflective learning programme developed by educational psychologists for school leaders in exploring the implementation of compassionate, relational approaches in schools, using an integrated whole school framework | Mixed methods |

| Rimm-kaufman [140] | 2004 | Us | School children | Teachers and staff | Education | Grades kindergarten through 3 | Examine the ways in which experience with a relational approach to education, the responsive classroom (RC) approach, related to teachers' beliefs, attitudes and teaching priorities | Mixed methods |

| Segal [141] | 2013 | US | Spanish-speaking immigrant clients | Social workers | Social care/work | Home visitation with immigrant clients | Applies relational theory to implementation issues around early childhood home visitation with Spanish-speaking immigrant clients | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Smyth [142] | 2007 | UK, USA, Australia, Canada, New Zealand | Students | Teachers | Education | Secondary school | Present a rationale for reinserting the relational work of schools at the centre of a teacher development-led form of recovery | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Steckley [143] | 2020 | UK | Children and young people in care | Residential care staff | Social care/work | Residential care (children and youth) | Identify and explore potential threshold concepts in residential childcare, with a corollary question about the utility of threshold concept theory in considering student and practitioner learning. | Qualitative |

| Svanemyr [144] | 2014 | Norway | Adolescents | Health care professionals | Health | Adolescent sexual and reproductive health | Provide a conceptual framework and the key elements for creating enabling environments for adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH). | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Swan [145] | 2018 | Ireland | Children and young people in care | Residential care staff | Social care/work | Residential care (children and youth) | Explores the psychodynamics of relationship-based practice from the perspective of young people in residential care. | Qualitative |

| Thachuk [146] | 2007 | Canada | Prenatal and postnatal women/birthing people | Midwives | Health | Midwifery—bioethics | Examines the parallels between the Canadian midwifery model of care and feminist reconfigurations of autonomy and choice. | Critical/narrative review |

| Thermane [147] | 2019 | South Africa | Pupils and parents | Teachers | Education | Schools in low-resourced communities | Argue for the use of the curriculum to make schools in low-resourced communities become effective despite the chronic adversities they face on a daily basis. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Townsend [148] | 2020 | UK | Residents | Big local representatives | Social care/work | Community development work | Presents findings on the potential role of money as a mechanism to enhance capabilities from an on-going evaluation of a major place-based initiative being implemented in 150 neighbourhoods | Qualitative |

| Trevithick [149] | 2003 | UK | Social work service users | Social workers | Social care/work | General social work | Discuss the importance of a relationship-based approach within social work, within a psychosocial perspective, in relation to eight areas of practice | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Tudor [150] | 2020 | New Zealand | Children | School social workers | Social care/work | Post-earthquake recovery work | Outlines some findings from an inquiry undertaken in the aftermath of 2011 earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which positive critique was used to examine the practice accounts of twelve school social workers alongside characteristics of recovery policies. | Qualitative |

| Turney [151] | 2012 | UK | Involuntary clients | Social workers | Social care/work | Child protection | Focuses on the process of engaging with families where a child is at risk of harm and considers a relationship-based approach to work with ‘involuntary clients’ of child protection services. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Turney [152] | 2001 | UK | Clients of child protection services | Social workers | Social care/work | Child protection | Examines the effects of physical and emotional neglect on children and considers effective social work intervention strategies for working with them and their families, making the argument that cases of chronic neglect, all involve the breakdown or absence of a relationship of care. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Valaitis [153] | 2018 | Canada | Patients | Primary health care & public health | Health | Primary care and public health | Examine Canadian key informants’ perceptions of intrapersonal (within an individual) and interpersonal (among individuals) factors that influence successful primary care and public health collaboration | Qualitative |

| Veenstra [154] | 2014 | Canada | General public/patients | Healthcare professionals | Health | Health promotion and public health | Discusses Bourdieu’s relational theory of practice in relation to agency health promotion and public health research | Critical/narrative review |

| Veenstra [155] | 2014 | Canada | General public/patients | Healthcare professionals | Health | Health promotion and public health | Advocate for a relational approach to the structure–agency dichotomy, suggesting that relational theories can provide useful insights into how and why people ‘choose’ to engage in health-related behaviours. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Vielle [156] | 2012 | New Zealand | Maori people | People working within criminal justice | Criminal justice | Criminal justice | Examines the philosophy of justice embodied in Tikanga Mãori, the Mãori traditional mechanism and approach to doing justice which adopts a holistic and relational lens | Qualitative |

| Ward-griffin [157] | 2012 | Canada | End-of-life patients | Palliative care nurses | Health | Palliative care | Examines the provision of home-based palliative care for Canadian seniors with advanced cancer from the perspective of nurses. | Qualitative |

| Warner [158] | 2015 | US | Severe disabilities | Educators and Therapists | Education | Community-based Special Education | Addresses the importance of community in fostering transformative learning and living environments for children with special needs. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Webber [159] | 2017 | UK | Children | Teachers | Education | Primary school | Explore how the case study school defines their approach and identify the strategies they put in place to support looked after and adopted children. | Case study/report |

| Werder [160] | 2016 | US | Students | Teachers | Education | Universities | Using examples from two institutions, partnerships with students in the scholarship of teaching and learning (SOTL) category of the partnership model are explored, focussing particularly on “co-inquiry” | Case study/report |

| Williams [161] | 2009 | UK | Older people | Nursing and care staff | Health | Acute settings for older people | Argue that the care of older people in acute settings will not be improved until more emphasis is given to the nature and quality of relationships between practitioners, older people and their carers recognising the importance of ‘relational practice’ as the basis for high-quality care. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Williams [162] | 2018 | UK | Families | Family practitioners | Social care/work | Family service delivery | Describes the findings of an evaluation of a training programme; The Restorative Approaches Family Engagement Project | Mixed methods |

| Wortham [163] | 2012 | US | Teachers, students | Educational psychologist | Education | Educational psychology | Outlines the implications of Gergen’s [164] relational approach for educational research and practice. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Wright [165] | 2012 | Canada | End-of-life patients | Nurses | Health | End-of-life care | Discusses the McGill Model of Nursing [166] provides for a relational approach that is congruent with the philosophy of palliative care. | Opinion piece/theoretical argument |

| Wyness [167] | 216 | UK | Students | Teachers | Education | Secondary school | Explores social and emotional work carried out in a case study of a school in an area of considerable economic deprivation. | Qualitative |

| Younas [168] | 2017 | Pakistan | Coronary care patients | Nurses | Health | Coronary hospital care | Describe the usefulness of the relational inquiry approach by analysing a patient’s health-illness transition and the nurse-patient interaction in Pakistan | Case study/report |

| Younas [169] | 2020 | Canada | Patients | Nurses | Health | Hospital care | Describe the relational inquiry nursing approach and illustrate how this approach can enable nurses to develop a deeper awareness of patient suffering | Case study/report |

aCountry of practice/organisation or where not stated country of author/s

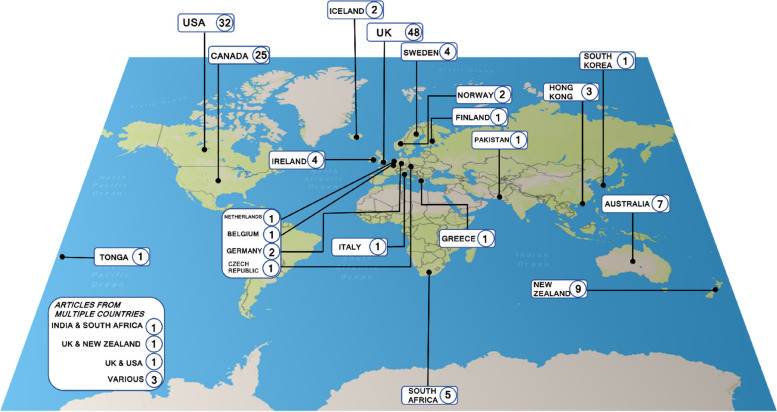

Country

Country relating to the service or organisation discussed was extracted from the included articles, where this was not identified the author’s affiliated country was noted. Figure 2 displays the countries represented in the included articles. Most of the included articles were from the UK (n = 48, 30.38%), followed by the USA (n = 32, 20.25%) and Canada (n = 25, 15.82%). There was however a broad and global spread of literature across the rest of the included literature.

Fig. 2.

Frequencies of countries represented in the included articles/studies

Sector type

In relation to the four sector types, health has the highest proportion of included literature (n = 60, 37.92%), followed by education (n = 41, 25.95%), social work/care (n = 39, 24.68%), and criminal justice (n = 17, 10.76%), with 1 paper that was across the 4 sectors [3]. Table 3 displays the frequencies of the sector types across the included articles/studies alongside the specific service/focus within each sector.

Table 3.

Frequencies of articles/studies for each sector type with specific service type or focus

| Sector type | n (%) | Articles/studies |

|---|---|---|

| Health | 60 (37.97%) | |

| Mental healtha | 12 (20.00%) | [2, 11, 16, 19, 20, 43, 46, 85, 101, 118, 124, 125] |

| Recovery and substance abuse | 7 (11.67%) | [14, 47, 72, 109, 119, 120, 127] |

| Elderly residential/inpatient care | 7 (11.67%) | [12, 24, 31, 33, 49, 64, 82] |

| General nursing/healthcare systems | 8 (13.33%) | [59, 62, 67, 100, 113, 135, 136, 169] |

| Primary care/public health/health promotion | 4 (6.67%) | [126, 153–155] |

| Acute hospital care | 3 (5.00%) | [32, 60, 161] |

| Emergency care | 3 (5.00%) | [68–70] |

| Midwifery | 2 (3.33%) | [58, 131] |

| Bioethics | 2 (3.33%) | [88, 146] |

| Palliative/end-of-life care | 2 (3.33%) | [157, 165] |

| School nursing/health projects | 2 (3.33%) | [107, 110] |

| Family nursing | 2 (3.33%) | [14, 36] |

| Other nursing/healthcareb | 6 (10.00%) | [39, 63, 92, 133, 144, 168] |

| Education | 41 (25.95%) | |

| Compulsory education school context | 9 (21.95%) | [30, 44, 54, 79, 83, 104, 105, 108, 139] |

| University | 7 (17.07%) | [29, 40, 73, 111, 112, 123, 160] |

| Secondary school | 5 (12.20%) | [41, 65, 75, 142, 167] |

| Kindergarten/elementary/primary school | 4 (9.76%) | [94, 98, 140, 159] |

| Specialist schoolsb | 3 (7.32%) | [90, 91, 137] |

| Nursing education | 2 (4.88%) | [61, 81] |

| Social work education | 2 (4.88%) | [23, 53] |

| After-school care/education | 2 (4.88%) | [97, 130] |

| Practitioner CPD short courses | 2 (4.88%) | [80, 128] |

| Early years education training | 1 (2.44%) | [45] |

| Multi-cultural urban schools | 1 (2.44%) | [35] |

| schools in low-resourced communities | 1 (2.44%) | [147] |

| Community-based special education | 1 (2.44%) | [158] |

| Educational psychology | 1 (2.44%) | [163] |

| Social work/care | 39 (24.68%) | |

| Child protection | 6 (15.38%) | [27, 71, 93, 102, 151, 152] |

| Residential childcare | 5 (12.82%) | [34, 38, 143, 145, 170] |

| General social work | 5 (12.82%) | [17, 42, 76, 103, 138] |

| Community development work/projects | 5 (12.83%) | [48, 86, 89, 148, 149] |

| Children and youth services | 4 (10.26%) | [55, 77, 78, 122] |

| Children and families | 3 (7.69%) | [26, 84, 162] |

| Disability social care services | 2 (5.13% | [87, 115] |

| Migration/asylum seekers | 2 (5.13%) | [99, 141] |

| General social care | 2 (5.13%) | [118, 121] |

| Other social careb | 5 (12.83%) | [95, 96, 116, 134, 150] |

| Criminal justice | 17 (10.76%) | |

| Young offenders | 5 (29.42%) | [15, 25, 37, 50, 52] |

| Probation/prison/re-entry to society | 6 (35.29%) | [21, 22, 28, 57, 129, 132] |

| Female offenders | 2 (11.65%) | [18, 74] |

| Hard to engage young people | 1 (5.88%) | [51] |

| Policing | 1 (5.88%) | [66] |

| International peace building | 1 (5.88%) | [106] |

| General criminal justice | 1 (5.88%) | [156] |

Older persons residential care has been included in the Health sector category as this care is conducted by both health and social care organisations but is with a population with predominately healthcare needs

aonly one of the mental health studies in the health sector was with children and adolescents (the rest were adult studies)

bOther nursing/healthcare includes a study each on dementia, dialysis, coronary, AIDS, pain management, adolescent sexual and reproductive health, Specialist schools include one study each for schools for children with emotional, behavioural and educational issues, public charter schools, five schools forming a Kahui Ako, Other social care includes post-earthquake recovery work, peer support services, carer support, veteran reintegration support, domestic violence

Study/article type

Study/article types were categorised as scoping or systematic reviews, empirical studies (either qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods), case studies, critical/narrative or opinion pieces/theoretical arguments. There was some overlap between the last three categories (e.g., some publications emphasising opinion or theoretical argument may also have included some brief details about application in a specific site/s). Where there was overlap the coders recorded the category that was closest to the authors’ stated intention (i.e., the aims of the article).

Descriptions of these articles were as follows:

Case study—a discussion or examination of relational practice or application of a delivery model in a specific site/s.

Critical/narrative review—generalised critique of relational practice or a particular philosophical approach and/or critical review of literature

Opinion piece/theoretical argument—where authors are proposing a particular approach or theoretical model for relational practice and/or an opinion of how to apply relational practice in a specific sector or the importance of relational practice in a specific sector

A large proportion of publications were opinion-based or theoretical argument papers (n = 61, 38.60%), with a further 6 (3.80%) critical or narrative reviews. These publications tended to propose models of relational practice or make arguments for the use of the relational practice in a specific service or organisation (see Table 2 for a summary of the aims of these studies/articles). An additional large number of included publications reported qualitative studies (n = 45, 28.48%) or case studies (n = 27, 17.09%). There was a lack of effectiveness trials or quantitative studies, with only 6 (3.80%) using a quantitative design and 9 (5.70%) using a mixed methods design.

Of the included publications, 27 were categorised as case studies, and 16 were descriptions of a practice or organisation and did not include any empirical data, although some did provide literature review and/or citations of other evidence sources relating to effectiveness [21, 101]. In these publications, the focus was predominately on explaining the relational practice being used in an organisation or a specific intervention and its components, rather than conducting an evaluation or examination of the effectiveness of the service. Four of these case studies were related to criminal justice services; one discussed the application of democratic therapeutic communities in the prison service [21], a further two discussed transition programmes for female offenders [28, 74] and one a community wealth-building project to promote successful re-entry for people released from prison [129]. Five of these articles related to an education setting and discussed applying the relational practice in the provision of faculty support [73], mentoring [108], delivery of a CPD course in community development [128], approach in a special school for adolescents with emotional, behavioural and educational issues [90] and using co-inquiry to form a partnership between students and lecturers in a university [160]. Six studies were health-related describing interventions for women with substance use problems and mental illness [72, 119], community-based nursing service for children and families [126] and a school obesity programme [107]. A final case study of a large UK local authority adult care department to describe a new practice model for social care [118].

The other 11 case studies included numerically informed quantitative data evaluating the service, intervention or practice described and are included alongside the studies using qualitative, quantitative or mixed-method study designs in Table 4. Most of the empirical evidence relating to the case studies is qualitative and focussed on the perceived impacts and benefits of the provision/intervention (see Table 4). Findings also relate to the importance of an institutional buy-in to the practice and support and training of staff in the approach to ensure success [41, 57, 135].

Table 4.

Descriptions of empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods, including case studies with empirical data)

| Author | Date | Description | Participant characteristics | Sample size | Data collection | Data analysis | Key findings relating to relational practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case study/report with empirical data | |||||||

| Berzoff [23] | 2006 | Describes and evaluates a master’s programme for social workers | Social workers working an average of 15.3 years in end-of-life care; ages from 26 to 71, Mage = 47.7 years; range of settings, including hospitals, community-based agencies, prisons, hospices, and nursing homes. | Not mentioned | Secondary data analysis of student’s evaluations | Thematic analysis | The hours students spent with their supervisors modelled how to be fully present with their dying and bereaved clients |

| Campbell [39] | 2012 | Secondary analysis of two contrasting case studies using peer education as the starting point for involving highly marginalised women in HIV/AIDS management. | Women with AIDS living in the community | Not mentioned | Secondary data analysis of case studies | Case comparison | Transformative communication (TC) flourished in one site and failed in another; TC is unlikely to be practiced in a non-transformative context, aspects of the material, symbolic and relational contexts of the two case studies profoundly shaped the possibility of successful TC. Creating enabling environments for transformative communication is a crucially important, though often neglected element of community health programmes. |

| Celik [41] | 2021 | Investigate how a secondary school improves the educational engagement of working-class, second-generation Turkish immigrant youth in Germany. | Students aged 15–18 years | 14 students and 10 teachers | Semi-structured interviews, observation, documentary analysis | Qualitative content analysis | The school’s institutional habitus combines the communal values of the immigrant community and the middle-class academic practices; the former narrows the gap between home and school, and the latter modifies the classed feelings of students. |

| Davies [57] | 2019 | Examines the progress of introducing Enabling Environments (EE) standards across seven sites | Approved premises residents and prison inmates | Four approved premises (24–26 residents) 3 prisons (250–1000 inmates) | Part of a larger EE impact study—observations/discussion with staff, service feedback, prison resident responses | Thematic analysis | It is essential for those leading services and new initiatives to engage with staff on the ground to demonstrate why the change is necessary and should be pursued now. Those involved in service development need to have sufficient knowledge and understanding to make links between their practice and the standards/goals and need to be able to “buy into” the process. While Leadership and Involvement are two of the 10 EE standards, it appears that these might be considered foundation areas which are required as a platform onto which the other aspects of the process “sit.” |

| Durocher [64] | 2019 | To discern relational approaches adopted by families in planning for the discharge of older adults from inpatient settings | Patients, family members and professionals involved in discharge meetings (family conferences) in three case studies | N = 20 (five older adults, seven family members and eight healthcare professionals) | Secondary analysis of micro ethnographic case studies, including observational field notes & semi-structured interviews | Qualitative exploratory | Family members employed strategies to promote older adults’ participation in decision-making that were consistent with relational autonomy theory, to overcome tensions between older adults’ wishes to return home and family’ assumption of a primary role in discharge decision-making and their wish for the older adult to move to a supported setting |