Abstract

The cellular basis of cerebral cortex functional architecture remains not well understood. A major challenge is to monitor and decipher neural network dynamics across broad cortical areas yet with projection neuron (PN)-type resolution in real time during behavior. Combining genetic targeting and wide-field imaging, we monitored activity dynamics of subcortical-projecting (PTFezf2) and intratelencephalic-projecting (ITPlxnD1) types across dorsal cortex of mice during different brain states and behaviors. ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons showed distinct activation patterns during wakeful resting, spontaneous movements, and upon sensory stimulation. Distinct ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks were dynamically tuned to different sensorimotor components of a naturalistic feeding behavior, and optogenetic inhibition of ITsPlxnD1 and PTsFezf2 in subnetwork nodes disrupted distinct components of this behavior. Lastly, ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 projection patterns are consistent with their subnetwork activation patterns. Our results show that, in addition to the concept of columnar organization, dynamic areal and PN type-specific subnetworks are a key feature of cortical functional architecture linking microcircuit components with global brain networks.

Introduction

The cerebral cortex orchestrates high-level brain functions ranging from perception and cognition to motor control, but the cellular basis of cortical network organization remains poorly understood. The mammalian cortex consists of dozens to over a hundred cortical areas, each featuring specific input-output connections with multiple other areas, thereby forming numerous functional subnetworks of information processing1,2. A foundational concept of cortical architecture is the columnar organization of neurons with similar functional properties3–5. Across cortical layers, diverse neuron types form intricate connections with each other and with neurons in other brain regions, constituting a “canonical circuit” that is duplicated and modified across areas6–8. An enduring challenge is to decipher the cellular basis of cortical architecture characterized by such nested levels of organization that integrates microcircuits with global networks across spatiotemporal scales9,10.

Among diverse cortical cell types, glutamatergic pyramidal neurons (PNs) constitute key elements for constructing the cortical architecture7,11. Whereas PN dendrites and local axonal arbors form the skeleton of local microcircuits, their long-range axons mediate communication with other cortical and subcortical regions. PNs can be divided into hierarchically organized major classes and subclasses, each comprising finer grained projection types7,12. One major class is the pyramidal tract (PT) neurons, which gives rise to corticofugal pathways that target all subcortical regions down to the brainstem and spinal cord. Another class is the intratelencephalic (IT) neurons, which targets other cortical and striatal regions, including those in the contralateral hemisphere. Recent studies in rodents have achieved a comprehensive description of cortical areal subnetworks13–15 and have begun to reveal their cellular underpinnings16,17. However, how these anatomically-defined networks relate to functional cortical networks remains unclear, as such studies require methods to monitor neural activity patterns in real time across large swaths of cortical territory yet with cell type resolution and in behaving animals.

fMRI measures brain-wide metabolic activities as a proxy of neural activity but with relatively poor spatial and temporal resolution18,19. Conversely, single unit recording20 and two-photon calcium imaging21 achieve real-time monitoring of neural activity with cellular resolution, but with rather limited spatial coverage. Widefield calcium imaging provide an opportunity to monitor activity in real time across a wide expanse of the mouse cortex at cellular resolution22. However, most studies to date have imaged activity either of broad neuronal classes23–33 or of laminar subpopulations containing mixed projection types34–38. While these studies have offered insights into cortical activity during different brain states, they have yet to resolve and compare activity in distinct PN types. In particular, how IT and PT PNs each contribute to cortical processing during different brain states in behaving animals remains to be elucidated.

We recently generated a comprehensive genetic toolkit for targeting the hierarchical organization of PNs in mouse cerebral cortex39, including the PlxnD1 and Fezf2 driver lines that readily distinguish IT and PT PN types, respectively. Here, we used widefield imaging to examine the dynamics of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subpopulations across the dorsal cortex of mice during a range of brain states. ITsPlxnD1 and PTsFezf2 show distinct activity dynamics during quiet wakefulness, spontaneous movements, upon sensory stimulation, and under anesthesia. Furthermore, distinct ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks dynamically tuned to different components of feeding behavior, including food retrieval, coordinated mouth-hand movements and ingestion. Optogenetic inhibition of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 in key areas of these subnetworks disrupted distinct components of this behavior. Anterograde tracing of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 from these areas revealed projection patterns that contribute to functional activation of corresponding subnetworks. Together, these results demonstrate that IT and PT subpopulations form parallel cortical processing streams and output pathways with spatiotemporal activity patterns that are distinct and change dynamically with behavioral state. Consequently, in addition to the concept of columnar organization, dynamic PN type subnetworks is a key feature of cortical functional architecture that integrates cortical microcircuits to global brain networks.

Results

Within our PN genetic toolkit39, the Fezf2-CreER line captures the large majority of PT population (PTFezf2) in layer 5b and 6 (L5b/6), and the PlxnD1-CreER captures an IT subpopulation (ITPlxnD1) which resides in L2/3 and L5a. Whereas PTsFezf2 project to mostly ipsilateral subcortical regions and represent over 95% of corticospinal PNs, ITsPlxnD1 project to ipsi- and contra-lateral cortical and striatal targets 39. As IT is the most diverse PN class comprising intracortical, callosal, and cortico-striatal PNs across layer 2–6, we estimated that ITPlxnD1 represent about 63% of IT neurons marked by Satb2 (Fig. 1b). PTFezf2 and ITPlxnD1 are distributed across the entire dorsal neocortex (Fig. 1a, Suppl. Fig. 4a)39.

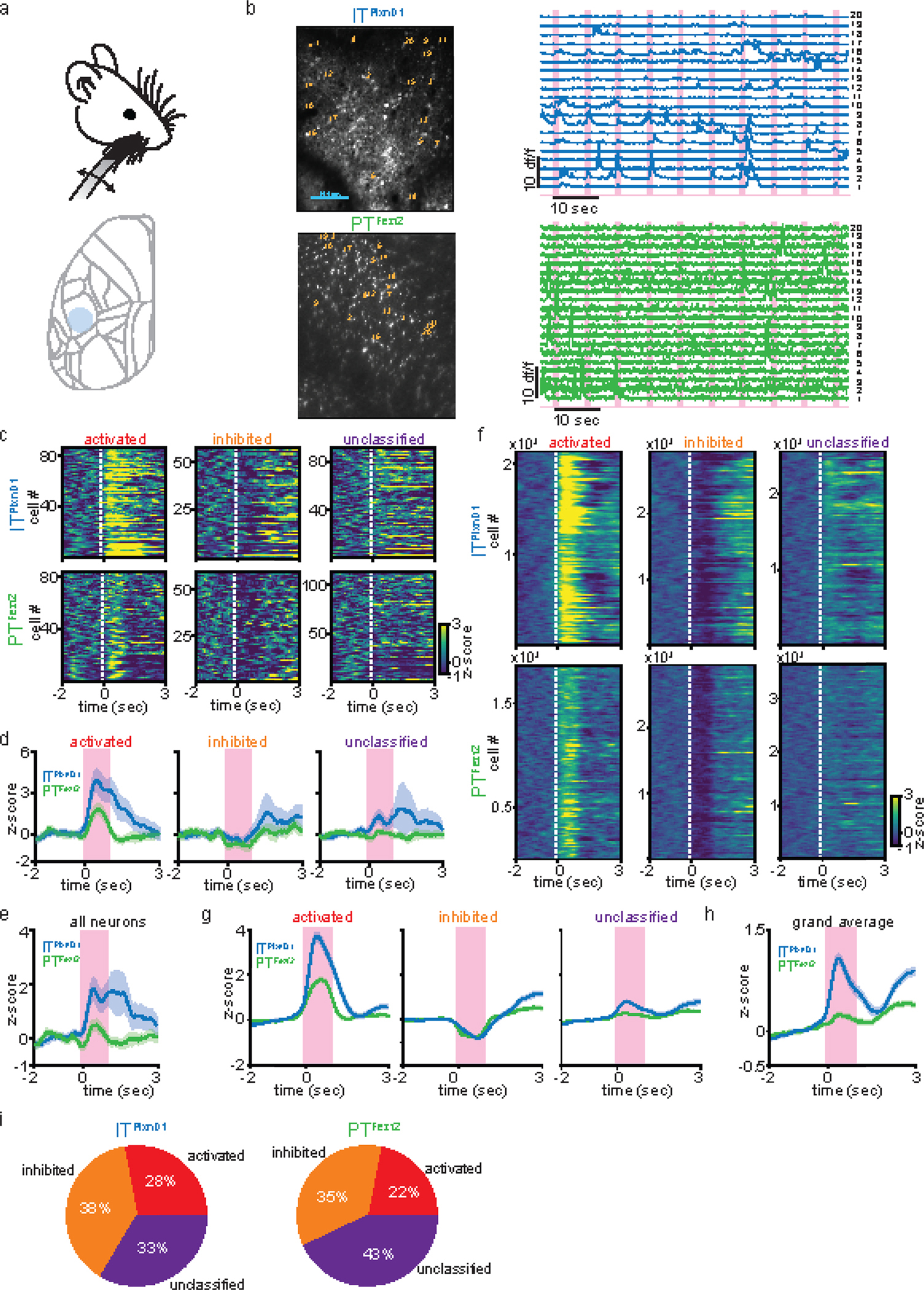

Figure 1. Distinct activity patterns of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during wakeful resting and upon sensory input.

a. STP images of GCaMP6f labeled PTFezf2 and ITPlxnD1 neurons across dorsal cortex. Arrow indicates anterior – posterior axis. Yellow text indicates approximate location of layer 2/3 (L2/3), layer 5a (L5a), layer 5b (L5b) and layer 6 (L6). Sagittal schematic depicts major projection patterns of IT and PT.

b. mRNA in situ images of Fezf2+ (left), PlexinD1+ (middle) cells. Double in situ overlaid (right) shows Satb2+ (red) and PlexinD1+ (green). PlexinD1+ cells represent subset of Satb2+ IT cells.

c. Example z-scored variance of behavior from video recordings (black trace) and corresponding variance of neural activity from ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green). Gray blocks indicate active episodes.

d. Average variance maps of spontaneous activity during active (right) and quiescent (left) episodes (n=12 sessions from 6 mice).

e-f. Distribution of percentage of cross-validated ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity variance explained by full frame behavior variance (e) and specific body part (f) from encoding model (n=12 sessions from 6 mice).

g. Illustration of unimodal sensory stimulation paradigm.

h. Mean activity maps of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 in response to corresponding sensory simulation (average of 12 sessions from 6 mice).

i. Single trial ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity within orofacial (yellow), whisker (red) and visual (purple) areas during orofacial (os), whisker (ws) and visual (vs) stimulation.

j. Single trial heat maps of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity from whisker (bc), orofacial (oc) and visual cortex (vc) in response to corresponding sensory stimulus from 1 example mouse for each cell type.

k. Mean activity of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 in whisker, orofacial and visual cortex during corresponding sensory stimulus (n=240 trials in 12 sessions from 6 mice, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

l. Distribution of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity intensity in whisker, orofacial and visual cortex during corresponding sensory stimulus (n=240 trials in 12 sessions from 6 mice); *p<0.05, ***p<0.0005. For box plots, central mark indicates median, bottom and top edges indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers extend to extreme points excluding outliers (1.5 times above or below interquartile range). All statistics in Supplementary table 1.

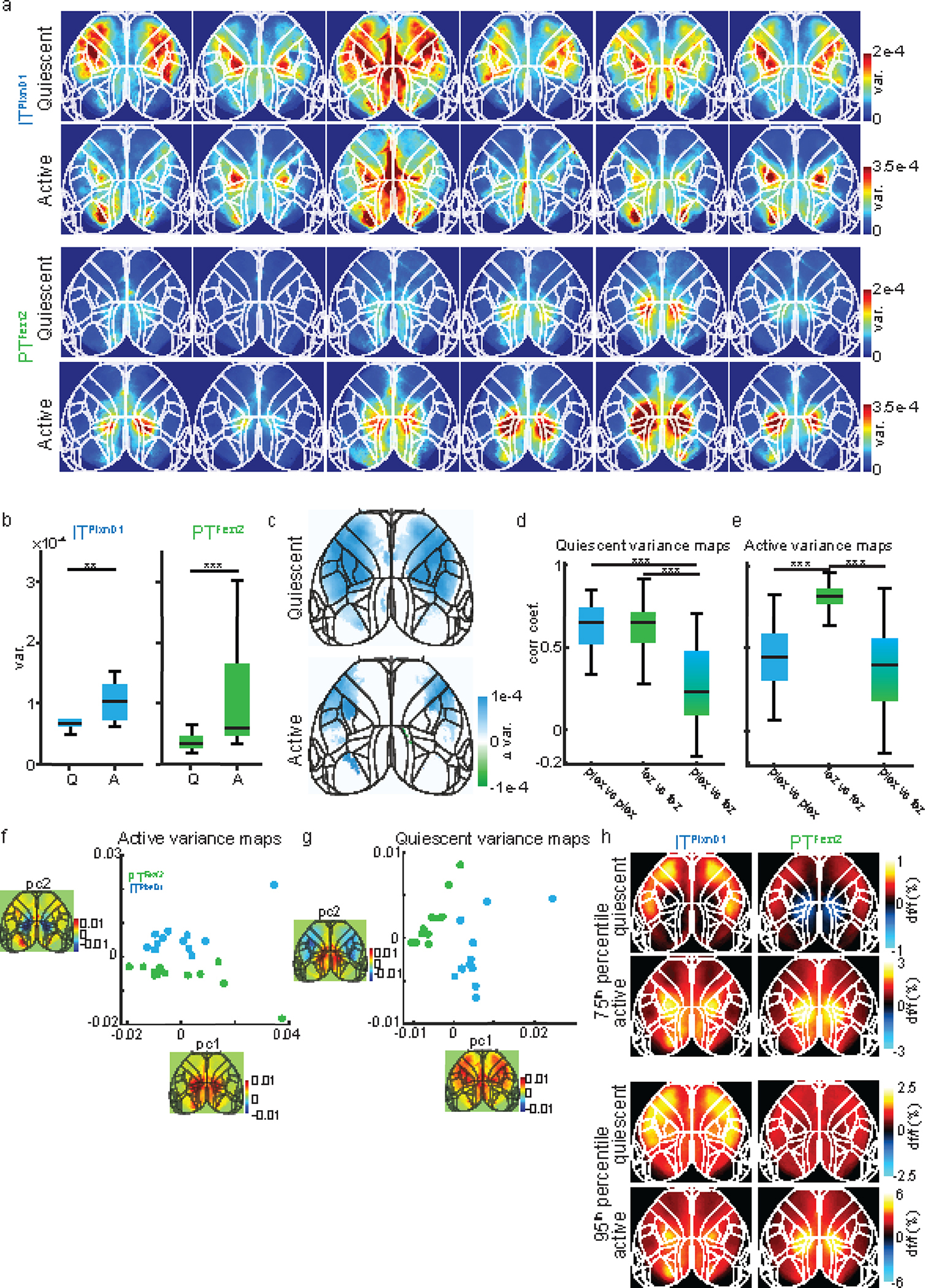

Distinct ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks during awake resting state

We bred PlxnD1 and Fezf2 driver lines with a GCaMP6f reporter line (Ai148), and examined global GCaMP6f expression pattern across dorsal cortex using serial two-photon tomography. Consistent with previous results39, GCaMP6f expression was restricted to L2/3 and 5a PNs in PlxnD1 mice, and to L5b and to a lower extent in L6 PNs in Fezf2 mice (Fig. 1a). We first characterized network dynamics of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during wakeful resting state in head-fixed mice using wide-field imaging across the dorsal cortex (Suppl. Fig. 1a,b). During this state, animals alternated between quiescence and spontaneous whisker, forelimb, and orofacial movements (Suppl. Videos 1,2). We quantified behavioral video variance recorded simultaneously with wide-field GCaMP6f imaging and identified episodes of quiescence and movements (active, Fig. 1c, Methods). We then measured neural activity variance across pixels in each episode and found significantly higher variance during active versus quiescent episode in both cell types (Extended data 1b). We then measured variance per pixel to obtain a cortical activation map during each episode. While both ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 were active across broad areas, they differed significantly in strongly active areas (Fig. 1d, Extended data 1a,c,d). In quiescent episodes, ITPlxnD1 were most active across forelimb, hindlimb, and frontolateral regions while PTFezf2 were more active in posteromedial parietal areas. During active episodes, ITPlxnD1 showed strong activation in hindlimb and visual sensory areas while PTFezf2 showed localized activation mostly in the posteromedial parietal regions, (Fig. 1d, Extended data 1a). We then compared the variance distribution at each pixel between the two populations to identify pixels that were significantly different between the two conditions (Ext Data Fig. 1c). Pearson’s correlation between spatial maps revealed strong correlation within and weak correlation between PN types during quiescent episodes (Extended data 1a,d). During active episodes, ITPlxnD1 activity maps were far more variable compared to PTFezf2 (Extended data 1a,e). Principal component analysis on the combined spatial maps of both PN types revealed non-overlapping clusters across both episodes, substantiating distinct cortical activation patterns between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 (Extended data 1f,g). Spatial maps of 75th and 95th percentile activity at each pixel indicated the magnitude of activation to be comparable with variance maps across episodes (Extended data 1h).

To investigate the correlation between neural activity and spontaneous movements, we built a linear encoding model using the top 200 singular value decomposition (SVD) temporal components of the behavior video as independent variables to explain the top 200 SVD temporal components of neural activity (Suppl. Fig. 2a,b). The top 200 components explained more than 85 % of neural and behavior variance in both populations with no significant difference (Suppl. Fig. 2a). Quantifying neural variance explained by spontaneous movements revealed PTFezf2 activity to be more strongly associated with spontaneous movements compared to ITPlxnD1 (Fig. 1e; suppl. methods). Furthermore, forelimb movements contributed significantly more towards PTFezf2 while other movements contributed equivalently between the two populations (Fig. 1f, Suppl. Fig. 2c, Suppl. methods).

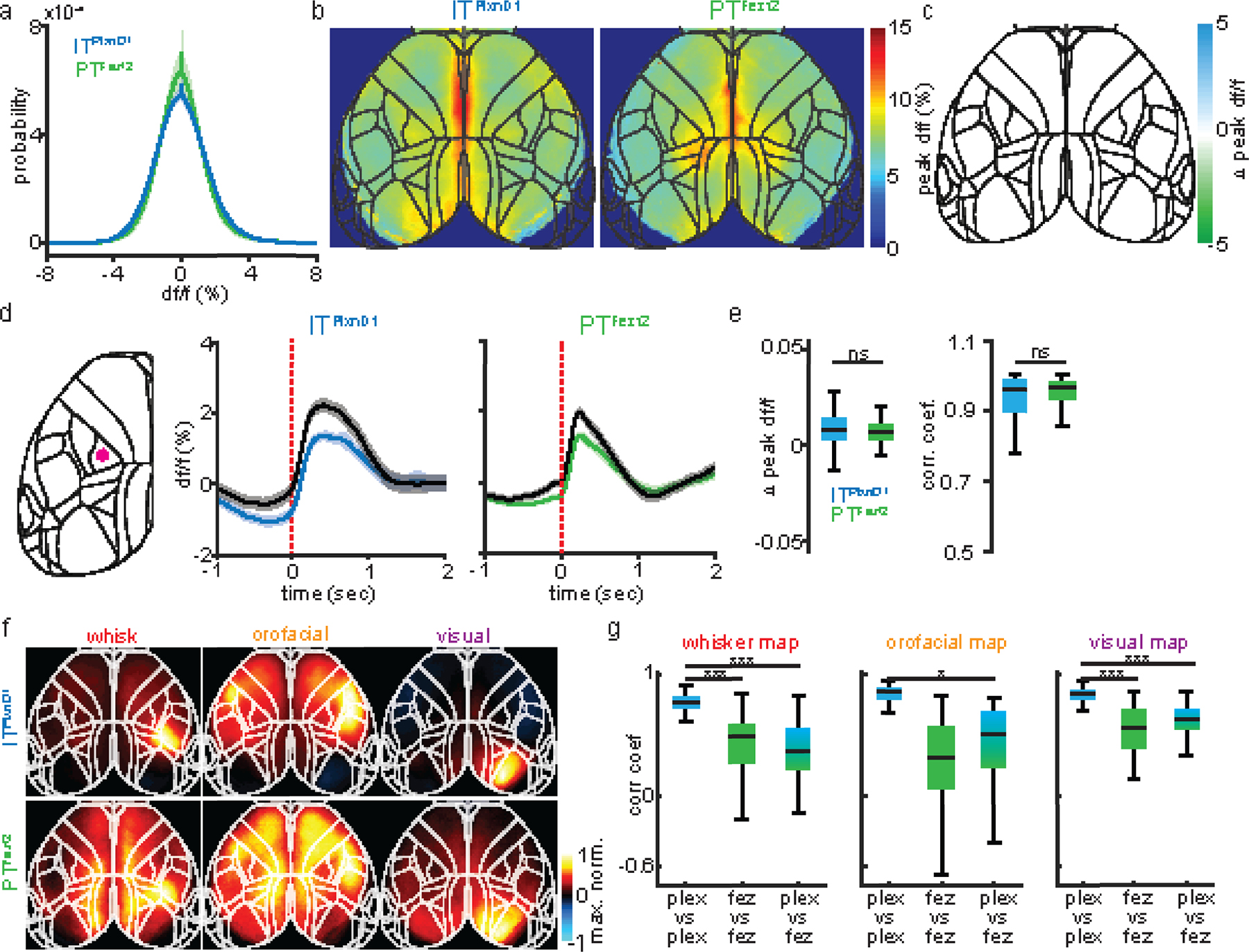

To evaluate whether difference in PTFezf2 and ITPlxnD1 responses could be explained by their difference in GCaMP6f expression we compared the distribution of df/f values from all pixels and peak df/f value at each pixel for every session during spontaneous behavior between the two PNs and found a similar distribution range for both (Extended data 2a–c). To verify if signal correction resulted in similar removal of artifacts, we performed df/f measurements with and without hemodynamic corrections from the hindlimb sensory area aligned to the onset of spontaneous movements (Extended data 2d). The peak difference and correlation between corrected and uncorrected signals were comparable between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 (Extended data 2e). Together, these results demonstrate distinct activation patterns of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during wakeful resting state with preferential PTFezf2 activation associated with spontaneous movements.

Sensory inputs preferentially activate ITPlxnD1 over PTFezf2

We next investigated ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activation following sensory inputs of the somatosensory and visual system (Fig. 1g, Methods). Light stimulation and tactile stimulation of whisker and orofacial region strongly activated ITPlxnD1 in primary visual, whisker and mouth-nose somatosensory cortex, respectively, but resulted in no or weak activation of PTFezf2 in those cortical areas (Fig 1h). On comparing temporal dynamics from centers of peak activation (methods), we found strong ITPlxnD1 but weak PTFezf2 activation in primary sensory cortices in response to whisker, orofacial, and visual stimulus (Fig. 1j,k). Comparing activity intensities validated significantly higher activity in ITPlxnD1 compared to PTFezf2 (Fig. 1l). Peak normalized maps further revealed activation in corresponding sensory cortices in PTFezf2 along with broader activation including retrosplenial areas (Extended data 2f). Stronger correlations between ITPlxnD1 spatial maps indicates reliability in activation pattern compared to PTFez2 (Extended data 2g). Considering that ITsPlxnD1 constitute a major subpopulation of ITs (Figure 1b), these results provide the first set of in vivo evidence that sensory inputs predominantly activate IT compared to PT PNs, consistent with previous findings that thalamic input predominantly impinges on IT but not PT cells40. Notably, ITsPlxnD1 activation per se does not lead to significant PT activation at the population level despite demonstrated synaptic connectivity from IT to PT PNs in cortical slice preparations41. It is possible that ItsPlxnD1 to PTFezf2 synaptic efficacy is modulated by brain states or that another IT subpopulation might more directly activate PTFezf2.

To confirm that widefield responses reflected calcium dynamics at cellular resolution, we used two-photon imaging to measure responses from single ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons from barrel cortex upon whisker stimulation (Extended data 3a, Methods). We recorded from cell bodies of ITPlxnD1 and apical dendrites of PTFezf2 (dendritic calcium activity in layer 5B is strongly correlated to cell body dynamics42–46, Extended data 3b) and used linear modelling approach to classify neurons as activated, inhibited or unclassified groups (Methods). We first measured the average response for each group of neurons form a single field of view (FOV) and found that within the activated group ITPlxnD1 neurons showed significantly higher response compared to PTFezf2 group (Extended data 3c,d). Average response of all neurons combined from a single FOV resulted in ITPlxnD1 displaying significantly larger response compared to PTFezf2 (Extended data 3e). Combining neuronal responses from all mice across all FOV’s resulted in similar response characteristics (Extended data 3f–h). These responses followed dynamics very similar to those observed using widefield imaging during whisker stimulation (Fig. 1k). Additionally, a larger proportion of ITPlxnD1 neurons were activated in response to whisker stimulation compared to PTFezf2 (across FOVs ITPlxnD1 vs. PTFezf2 mean ± s.d. (%), activated: 36.8 ± 15.5 vs. 28.1 ± 12.7, inhibited: 50.8 ± 20.6 vs. 44.8 ± 11.7, unclassified: 44.1 ± 12.3 vs. 54.9 ±15.6; data from all cells combined in Extended data 3i). These results show that the response properties in widefield imaging of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons closely reflect their cellular resolution dynamics.

PTFezf2 and ITPlxnD1 are tuned to distinct sensorimotor features

To examine the activation patterns of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during sensorimotor processing, we designed a head-fixed mouse feeding behavior. In this setup, mice sense a food pellet approaching on a moving belt, retrieve pellet into mouth by licking, recruit both hands to hold the pellet and initiate repeated bouts of hand-mouth coordinated eating movements that include: bite while handling the pellet, transfer pellet to hands while chewing, raise hands to bring pellet to mouth thereby starting the next bout (Fig. 2a, Suppl video 3). We used DeepLabCut47 to track pellet and body parts in video recordings and wrote custom algorithms to identify major events in successive phases of this behavior (Methods, Fig. 2b, Suppl. Fig. 3a, Suppl. Video 3).

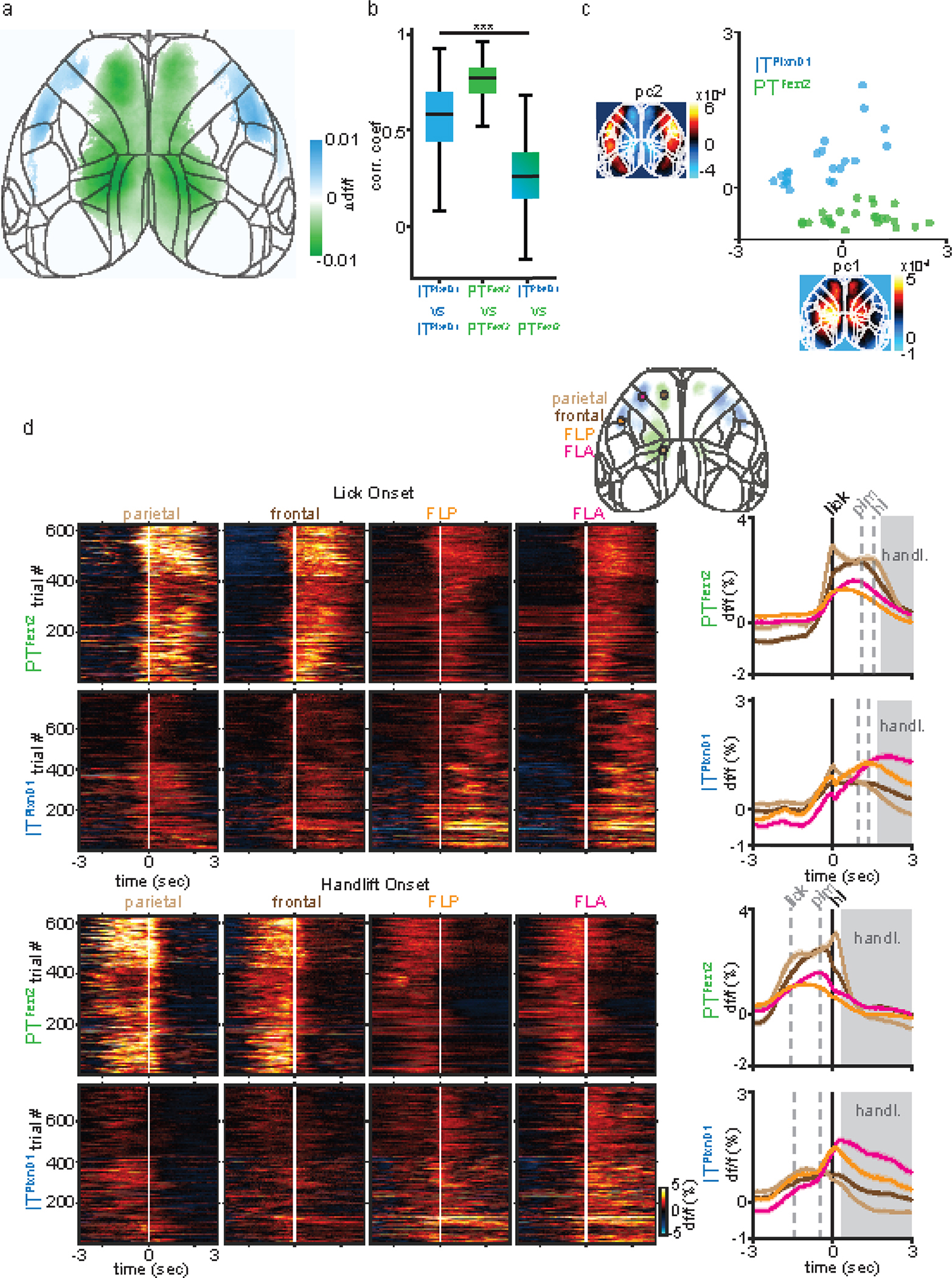

Figure 2. Distinct PTFezf2 and ITPlxnD1 subnetworks tuned to different sensorimotor components of a feeding behavior.

a. Schematic of the head-fixed feeding behavior showing the sequential sensorimotor components.

b. Example traces of tracked body parts and episodes of classified behavior events. Colored lines represent different body parts as indicated (light green shade: handle-and-eat episodes; orange shade: chewing episode).

c. Mean ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 sequential activity maps (200 ms steps) during the feeding sequence before and after pellet-in-mouth (PIM) onset (ITPlxnD1 – 23 sessions from 6 mice, PTFezf2 – 24 sessions from 5 mice). Note the largely sequential activation of areas and cell types indicated by arrows and numbers: 1) left barrel cortex (ITPlxnD1) when right whiskers sensed approaching pellet; 2) parietal node (PTFezf2) while making postural adjustments as pellet arrives; 3) forelimb sensory area (ITPlxnD1) with limb movements that adjusted grips of support bar as pellet approaches closer; 4) frontal node (PTFezf2) during lick; 5) orofacial sensory areas (FLP (Frontolateral Posterior), ITPlxnD1) when pellet-in-mouth; 6) parietal node again during hand lift; 7) FLA (Frontolateral Anterior)-FLP (ITPlxnD1) on handling and eating the pellet.

d. Difference between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 average activity maps at each time step as in panel c. Only significantly different pixels are displayed (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with p-value adjusted by False Discovery Rate = 0.05). Blue pixels indicate values significantly larger in ITPlxnD1 compared to PTFezf2 and vice versa for green pixels.

e. Spatial maps of ITPlxnD1 (top) and PTFezf2 (bottom) regression weights from an encoding model associated with lick, PIM, hand lift, eating and handling, and chewing (ITPlxnD1 - 23 sessions from 6 mice, PTFezf2 - 24 sessions from 5 mice).

We imaged the spatiotemporal activation patterns of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 across dorsal cortex while mice engage in the behavior (Suppl. Videos 4,5). We calculated average GCaMP6f signals per pixel in frames taken at multiple time points centered around when mice retrieve pellet into the mouth (pellet-in-mouth, or PIM) (Fig. 2c). Upon sensing the pellet approaching from the right side, mice adjust their postures and hand grip of the support bar while initiating multiple right-directed licks until retrieving the pellet into the mouth. During this period (Fig. 2c), ITPlxnD1 was first activated in left whisker primary sensory cortex (SSbfd), which then spread to bi-lateral forelimb and hindlimb sensory areas (Fig 2c, Suppl. Video 4). Simultaneously or immediately after, PTFezf2 was strongly activated in left medial parietal cortex (parietal node) just prior to right-directed licks, followed by bi-lateral activation in frontal cortex (medial secondary motor cortex, frontal node) during lick and pellet retrieval into mouth (Fig 2c, Suppl. Video 5). During the brief PIM period when mice again adjusted postures and then lift both hands to hold the pellet (Fig 2c), ITPlxnD1 was activated in bi-lateral orofacial primary sensory cortex (frontolateral posterior node; FLP) and subsequently in an anterior region spanning the lateral primary and secondary motor cortex (frontolateral anterior node; FLA), while PTFezf2 activation shifted from bi-lateral frontal to parietal node. In particular, PTFezf2 activation in parietal cortex reliably preceded hand lift. Following initiation of repeated bouts of eating actions, ITPlxnD1 was prominently activated in bilateral FLA and FLP specifically during coordinated oral-manual movements such as biting and handling, whereas PTFezf2 activation remained minimum throughout the dorsal cortex. For each time point, we compared the average df/f values at each pixel to identify regions that were significantly different between the two populations, confirming the differential flow of activation pattern (Fig. 2d). Measuring correlation between maps at each time point revealed PTFezf2 activity maps to be strongly correlated during lick and handlift while ITPlxnD1 activity maps showed a sharp increase following pellet in mouth which continued during oro-manual handling. We found rather weak correlation between activation patterns of the two populations across time (Suppl. Fig. 3b).

To obtain a spatial map of cortical activation during specific events, we build a linear encoding model using binary time stamps associated with the duration of lick, PIM, hand lift, handling, and chewing as independent variables to explain the top 200 SVD temporal components of neural activity. We then transformed the model regression weights to obtain a cortical map of weights associated with each event (Fig. 2e, Suppl. methods). This analysis substantiated our initial observations (Fig. 2c). Indeed, during lick onset ITPlxnD1 was active in left barrel cortex and bilateral forelimb/hindlimb sensory areas, which correlated with sensing the approaching pellet with contralateral whiskers and limb adjustments, respectively. In sharp contrast, PTFezf2 was active along a medial parietal-frontal axis, which correlated with licking. During PIM, ITPlxnD1 was preferentially active in FLP with lower activity in FLA as well as in forelimb/hindlimb sensory areas, while PTFezf2 was still active along the parietofrontal regions. Prior to and during hand lift, PTFezf2 showed strong activation specifically in bilateral parietal areas, whereas ITPlxnD1 showed predominant bilateral activation in both FLA and FLP. During eating and pellet handling, ITPlxnD1 was strongly active in FLA and less active in FLP, while PTFezf2 was only weakly active specifically in the frontal node (Fig 2e, note scale change in panels). Both ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 showed significantly reduced activity across dorsal cortex during chewing (Fig. 2e).

To capture prominently activated cortical areas associated with onset of various feeding movements, we computed average activity per pixel during the progression from licking, retrieving pellet into mouth, to hand lift across mice and sessions (from 1 second before to 2 seconds after PIM, Fig. 3a,d). Comparing the average df/f distribution at each pixel confirmed that PTFezf2 activation was most prominent along a medial parietal-frontal network whereas ITPlxnD1 was most strongly engaged along a frontolateral FLA-FLP network (Extended data 4a). Activation patterns were much more strongly correlated within each population than between the two populations, with PTFezf2 maps being more consistent than ITPlxnD1 (Extended data 4b). Principal component analysis on combined spatial maps confirmed distinct cortical activation patterns between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during various feeding movements (Extended data 4c).

Figure 3. ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 within frontolateral and parietofrontal nodes show distinct temporal dynamics during feeding behavior.

a,d. Mean activity map of PTFezf2 (a, 24 sessions from 5 mice) and ITPlxnD1 (d, 23 sessions from 6 mice) during feeding from 1 second before to 2 seconds after PIM.

b,e. Example PTFezf2 (b) and ITPlxnD1 (e) activity from FLA (magenta), FLP (orange), frontal (dark brown) and parietal (light brown) nodes during feeding behavior; vertical bars indicate behavior events.

c,f. Single trial heatmaps of PTFezf2 activity from frontal and parietal (c) and ITPlxnD1 from FLA and FLP nodes (f) centered to lick, PIM, and handlift onset (5 sessions from one example mouse).

g. Mean PTFezf2 activity within frontal and parietal node centered to lick, PIM, and handlift onset. Grey dashed lines indicate median onset times of other events relative to centered event (5 sessions from one example mouse, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m). Grey shade indicates eating-handling episode.

h. Mean ITPlxnD1 activity within FLA and FLP centered to lick, PIM, and handlift onset (5 sessions from one example mouse, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

i. Single trial heatmaps of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activities within parietal, frontal, FLP and FLA centered to PIM (ITPlxnD1 - 23 sessions from 6 mice, PTFezf2 - 24 sessions from 5 mice).

j. Mean ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity within parietal (light brown), frontal (dark brown), FLP (orange) and FLA (magenta) centered to PIM (sample size as in panel i, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m). Left inset: Overlaid activity maps of ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green) after thresholding indicating distinct nodes preferentially active during the feeding sequence.

k. Distribution of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activities centered at PIM onset from parietal, frontal, FLP and FLA projected to the subspace spanned by first two linear discriminant analysis dimensions (ITPlxnD1 - 23 sessions from 6 mice, PTFezf2 - 24 sessions from 5 mice).

To characterize the temporal activation patterns of key cortical nodes during behavior, we extracted temporal traces from the center within each of these 4 areas and examined their temporal dynamics aligned to the onset of lick, PIM, and hand lift (Fig 3b, c, e, f). PTFezf2 activity in the frontal node rose sharply prior to lick, sustained for the duration of licking until PIM, then declined prior to hand lift; on the other hand, PTFezf2 activity in the parietal node increased prior to lick then declined immediately after, followed by another sharp increase prior to hand lift then declined again right after. In contrast, ITPlxnD1 activities in FLA and FLP did not modulate significantly during either licking or hand lift but increased specifically only when mice first retrieved pellet into mouth; while activation in FLP decreased following a sharp rise after pellet-in-mouth, activities in FLA sustained during biting and handling (Fig. 3g,h). To examine cortical dynamics from both populations within the same region, we measured GCaMP6f signals centered to PIM from all four nodes for each cell type. PTFezf2 showed strong activation within parietal and frontal nodes specifically during lick and hand lift, whereas ITPlxnD1 showed significantly lower activation within these nodes during these episodes (Fig. 3i,j). In sharp contrast, ITPlxnD1 was preferentially active in FLA and FLP specifically during PIM with sustained activity especially in FLA during biting and handling, but no associated activity was observed in PTFezf2 within these nodes during the same period (Fig. 3i,j). Similar difference in dynamics was observed from activity aligned to either lick or handlift onset (Extended data 4d)

To validate the differential temporal dynamics between PN types we projected activity traces onto the top two dimensions identified by LDA to visualize the spatial distribution of projected clusters (Methods). The analysis showed ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity clustered independently with little overlap across regions (Fig. 3k). Altogether, these results indicate that ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 operate in distinct and partially parallel subnetworks, which are differentially engaged during specific sensorimotor components of a feeding behavior. It is important to note that the IT class comprises diverse subpopulations beyond ITPlxnD1; it is possible that activity of another IT subpopulation might more closely correlate with PT neurons.

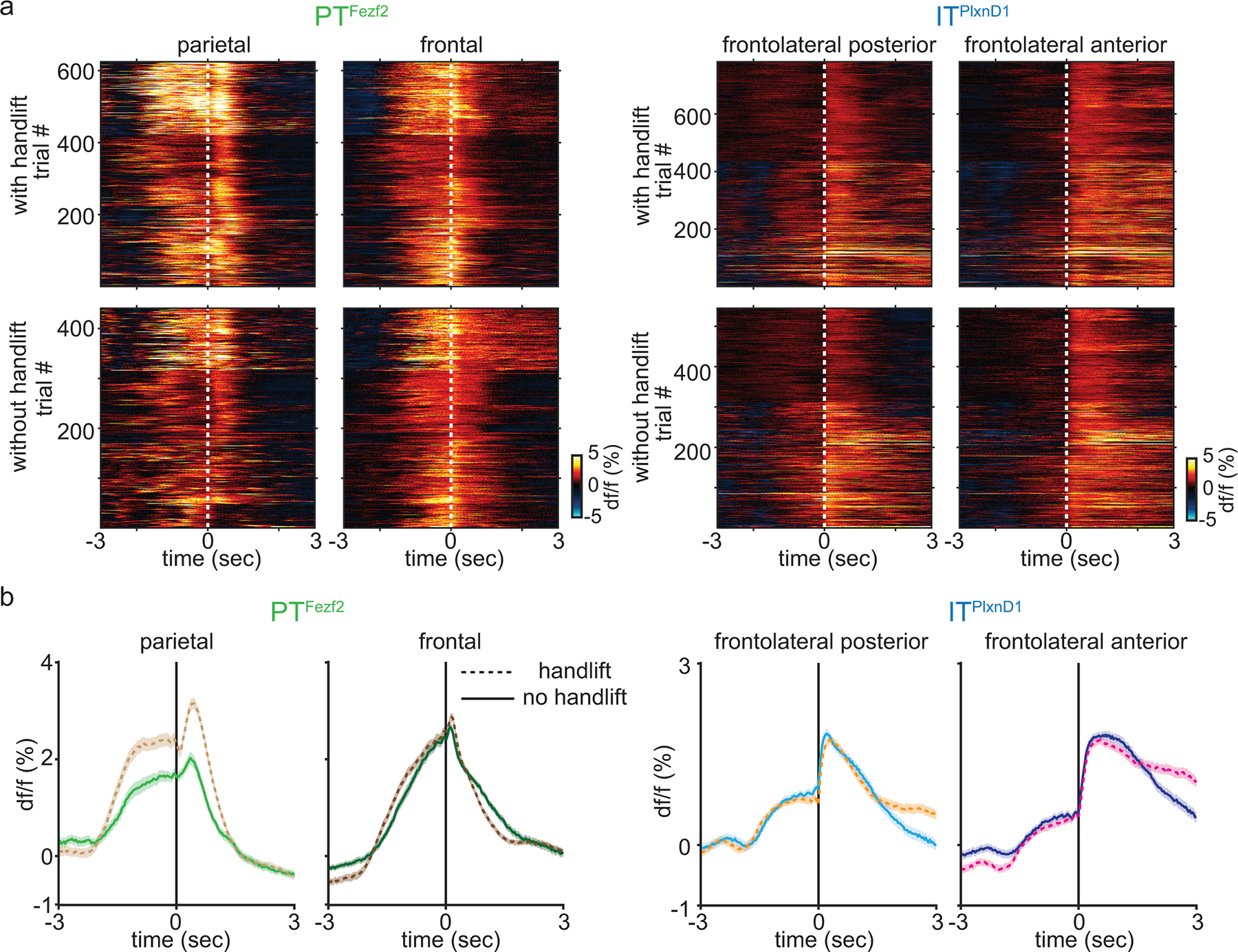

Feeding without hand occludes parietal PTFezf2 activity

To investigate if the observed PN dynamics were causally related to features of the behavior, we developed a variant of the feeding task in which mice lick to retrieve food pellet but eat without using hands (Fig. 4a); this was achieved by using a blocking plate to prevent hand lift until mice no longer attempted to use their hands during eating. We then measured ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activities aligned to the onset of lick and PIM, and compared these to those during normal trials in the same mice (Fig. 4b–e, Extended data 5a,b). Whereas PTFezf2 activity in the frontal node did not show a difference with or without hand lift, PTFezf2 activity in parietal node showed a significant decrease in trials without hand lift specifically during the time when mice would have lifted hand during normal trials (Fig 4c, Extended data 5a,b). On the other hand, ITPlxnD1 activity in FLA and FLP did not change during the same time with or without handlift. However, ITPlxnD1 activities in FLA and FLP showed a notable reduction during the eating-handling phase (Fig. 4d,e, Extended data 5a,b). Comparing activity intensity during with or without handlift indicated only PTFezf2 activities in parietal node to show a significant decline whereas ITPlxnD1 activities across FLA and FLP did not change during the hand lift phase (Fig. 4f,g).

Figure 4. Feeding without hand lift selectively occludes PTFezf2 activity in parietal node.

a. Schematic of feeding without hand lift trials.

b. Single trial heatmaps of PTFezf2 within frontal and parietal nodes centered to lick and PIM onset during feeding without handlift (2 sessions from one example mouse).

c. Mean PTFezf2 activity within frontal and parietal nodes centered to PIM during feeding with (dashed lines, 5 sessions from one example mouse) and without handlift (solid lines, 2 sessions from the same example mouse, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m). Grey box indicates eating-handling episode during handlift sessions.

d. Single trial heatmaps of ITPlxnD1 within FLA and FLP centered to lick and PIM onset during feeding without handlift (3 sessions from one example mouse).

e. Mean ITPlxnD1 activity within FLA and FLP centered to PIM during feeding with (dashed, 5 sessions from one example mouse) and without handlift (solid, 3 sessions from the same example mouse, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

f. Distribution of PTFezf2 activity intensity during 1 sec post PIM onset from parietal and frontal nodes during with and without handlift (no lift: 440 trials in 13 sessions from 5 mice, lift: 647 trials in 24 sessions from the same 5 mice).

g. Distribution of ITPlxnD1 activity intensity during 1 sec post PIM onset from FLA and FLP during with and without hand lift (no lift: 544 trials in 15 sessions from 6 mice, lift: 781 trials in 23 sessions from the same 6 mice).

h. Mean PTFezf2 (top) and ITPlxnD1 (bottom) activity maps during 1 sec post PIM onset with (left) and without (right) handlift.

i. Difference in PTFezf2 and ITPlxnD1 mean spatial activity maps between feeding with and without handlift. Only significantly different pixels are displayed (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with p-value adjusted by FDR = 0.05, sample size as in panel f,g). Note that parietal areas in PTFezf2 and no pixels in ITPlxnD1 are significantly different.***p<0.0005. For box plots, central mark indicates median, bottom and top edges indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers extend to extreme points excluding outliers. All statistics in Supplementary table 1.

To visualize cortical regions differentially modulated between trials with or without hand-lift, we computed mean pixel-wise activity during a 1 second period after PIM onset from both trial types and subtracted the spatial map of no-hand-lift trials from that of hand-lift trials (Fig. 4h). We computed difference between the two maps and visualized only significantly different pixels (Fig. 4i). As expected only the parietal region in PTFezf2 showed significantly higher activity during hand-lift compared to no-hand-lift trials while no pixels were significantly different within ITPlxnD1 (Fig. 4h,i). These results strengthen the correlation between parietal PTFezf2 activation and hand lift movement during feeding; they also suggest that ITPlxnD1 activity in FLA and FLP is in part related to orofacial sensorimotor components of feeding actions.

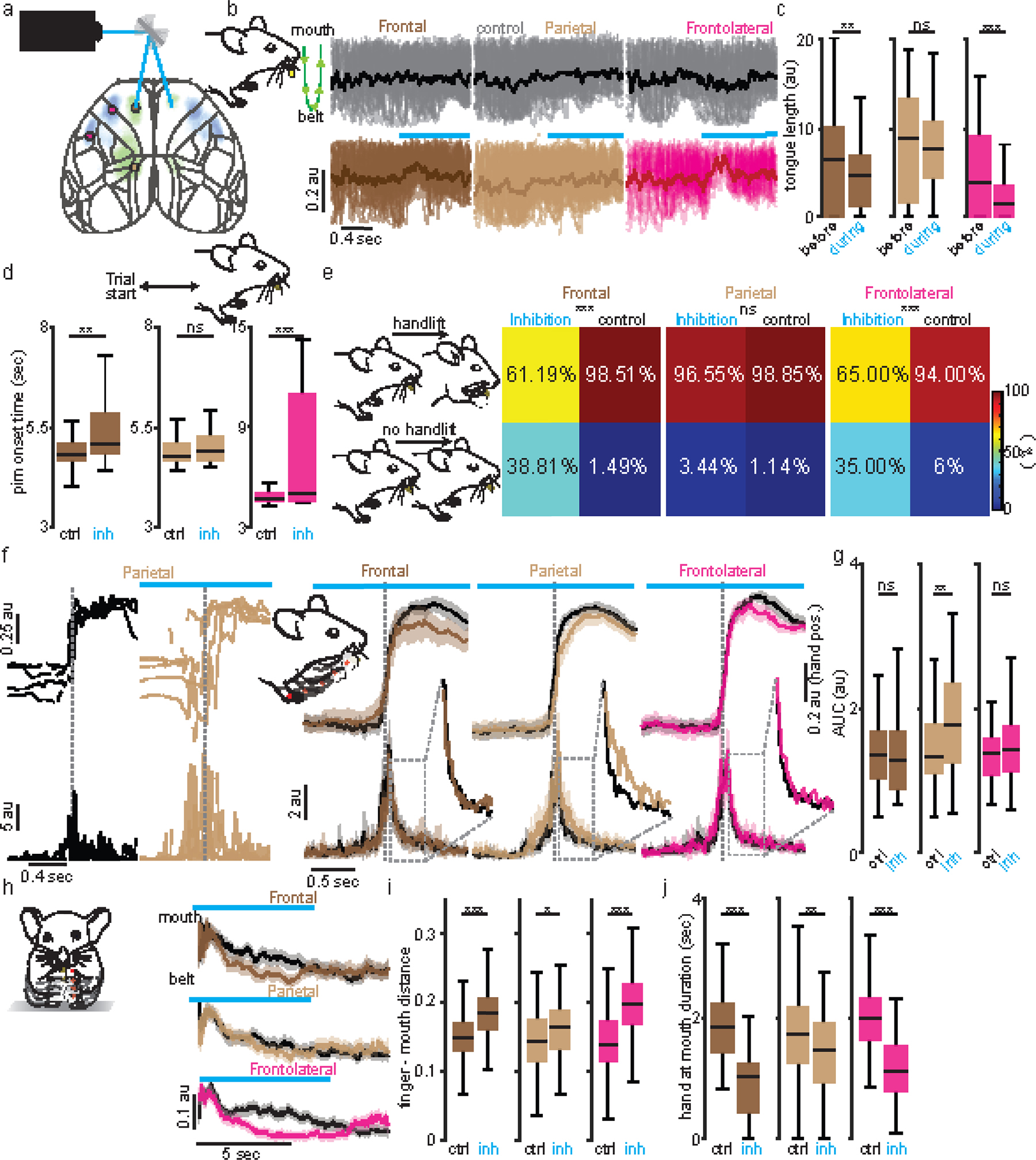

ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 inhibition differentially disrupts feeding

To first investigate if the cortical regions active during feeding behavior were necessary for its proper execution, we optogenetically inhibited bilateral regions of dorsal cortex using vGat-ChR2 mice expressing Channelrhodopsin-2 in GABAergic neurons (Extended data. 6a). We examined the effects of bilateral inhibition of parietal, frontal, FLP and FLA nodes on different components of the behavior including pellet retrieval by licking, hand lift after PIM, and mouth-hand mediated eating bouts. Our results show that the parietofrontal and frontolateral regions are necessary to orchestrate orofacial and forelimb movements that enable pellet retrieval and mouth-hand coordinated eating behavior (Extended data. 6).

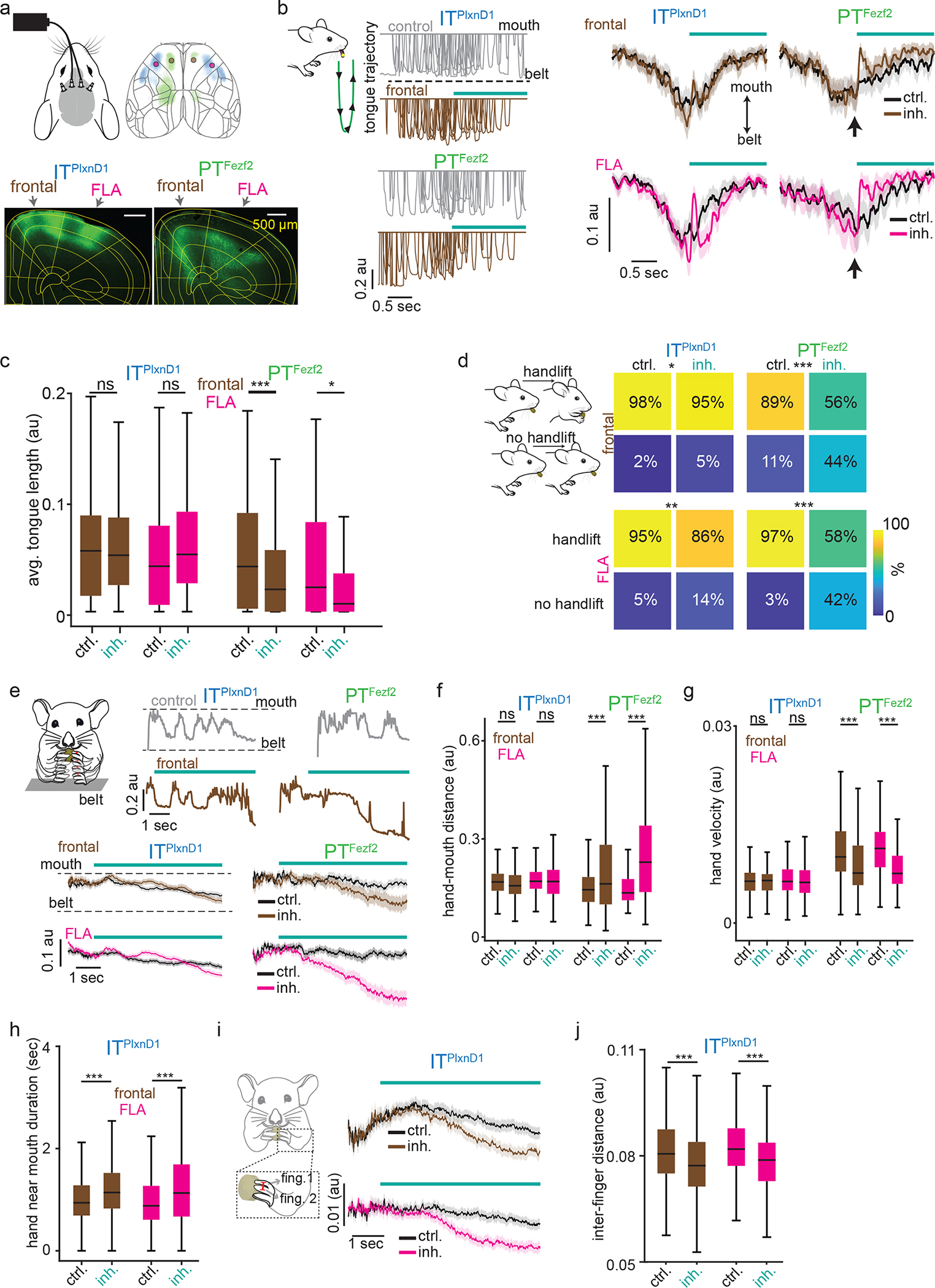

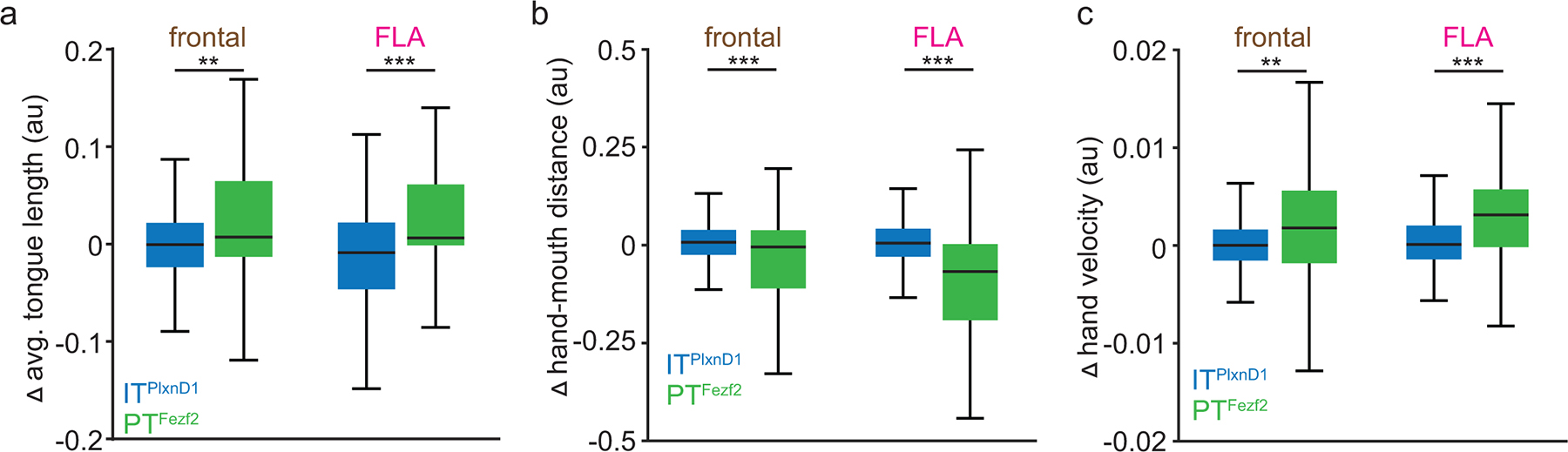

We then investigated if ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons within the same cortical region were causally associated with distinct sensorimotor components of the feeding behavior. We expressed-light activated Anion Channelrhodopsin (GtACR1) in ITPlxnD1 or PTFezf2 neurons in frontal and frontolateral regions of the same mouse and examined the effects of bilaterally inhibiting either population during specific phases of feeding (Methods, Fig. 5a). During pellet retrieval phase, PTFezf2 inhibition in both frontal and frontolateral nodes resulted in a sharp decrease in tongue length throughout the inhibition whereas ITPlxnD1 inhibition resulted in a momentary decrease at inhibition onset after which the animal recovered immediately to lick the pellet (Fig. 5b, Suppl. Video 6,7). This resulted in a significant decrease in the mean tongue length compared to control trials only when disrupting PTFezf2 but not ITPlxnD1 neurons (Fig 5c), which was substantiated by comparing the relative tongue length difference between the two populations (Extended data 7a). PTFezf2 inhibition in both frontal and frontolateral regions, after the mouse picked the pellet, disrupted the ability to bring hands to the mouth to hold the pellet, resulting in a sharp decrease in the proportion of handlift episodes while only a small effect was observed on ITPlxnD1 inhibition (Fig. 5d, Suppl. Video 8). This was validated by comparing the proportion of handlifts during inhibition between the two populations (Fig. 5d). Disrupting PTFezf2 in both frontal and frontolateral regions after retrieving the pellet and bringing hands to mouth (during food handling) strongly affected the gross mobility of hands such that mice were unable to properly bring the pellet towards the mouth (Fig 5e, Suppl. Video 9) resulting in an increase in hand-mouth distance and decrease in velocity (Fig. 5e,f,g). This was validated by comparing the relative hand to mouth distance and hand velocity difference between the two populations (Extended data 7b,c). While no such gross deficits were observed on ITPlxnD1 disruption (Fig. 5e,f,g), inhibiting both frontal and frontolateral resulted in a more subtle effect wherein mice had difficulty in using fingers to grasp the pellet properly, resulting in decreased agility and spending significantly longer time handling the pellet close to the mouth (Fig. 5e, Suppl. Video 10). Indeed, we found that during ITPlxnD1 inhibition the hands were closer to the mouth for a significantly longer time than control trials (Fig 5h). The decreased agility was accompanied by a drop in the number of grasps and rigid finger movements, resulting in a decrease in the distance between fingers during food handling (Suppl. Video 10, Fig 5i,j, methods). These results provide causal evidence that ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons within the same cortical regions differentially contribute to controlling distinct motor actions of feeding. While PTFezf2 is associated with controlling major oral and forelimb movements including lick and hand lift, ITPlxnD1 is likely involved in finer scale coordination such as finger movements during food handling.

Figure 5. Inhibiting ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 disrupts distinct components of feeding.

a. Top: Optogenetic setup layout (left) with inhibition location (right). Bottom: Example GtACR1 expression in ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 left cortex.

b. Left: 10 example tongue trajectories centered to inhibition of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 frontal (brown) node. Control (grey). Trajectories proceed from mouth (top) to belt (bottom, green schematic). Right: Mean tongue trajectories following inhibition of ITPlxnD1 frontal (brown, n=173), FLA (magenta, n=165) and PTFezf2 frontal (n=140) and FLA (n=98 trials) nodes. Black (control).

c. Distribution of mean tongue length for 1.5 seconds during control and inhibition of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 frontal and FLA nodes. Sample size as in b.

d. Handlift probability during control and inhibition of ITPlxnD1 frontal (n=201), FLA (n=200) and PTFezf2 frontal (n=82) and FLA (n=38) nodes.

e. Top two rows: example hand trajectory during inhibition (brown) of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 frontal node. Control (grey). Trajectories proceed from belt (bottom) to mouth (top). Bottom: Mean single hand trajectories during inhibition of ITPlxnD1 frontal (inh (n=353), control (n=363)), FLA (inh (n=455), control (n=461)) and PTFezf2 frontal (inh (n=167), control (n=176)) and FLA (inh (n=202), control (n=204)) nodes. Control (Black).

f,g. Distribution of mean normalized hand-mouth distance (f) and mean absolute hand velocity (g) for 5 seconds during control and inhibition of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 frontal and FLA nodes.

h. Distribution of mean hand near mouth duration for 5 seconds during control and inhibition of ITPlxnD1 frontal nodes.

i. Mean trace of inter-finger 1–2 distance during inhibition of ITPlxnD1 frontal (brown) and FLA (magenta) nodes. Control (black). Red line over finger 1 and 2 illustrates the variable measured.

j. Distribution of mean inter finger 1–2 distance for 5 seconds during control and inhibition of ITPlxnD1 frontal and FLA nodes. Sample size for panels f-j as in e. All data pooled from 4 mice for ITPlxnD1 and 3 for PTFezf2. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005. For box plots, central mark indicates median, bottom and top edges indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers extend to extreme points excluding outliers. Shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m. All statistics in supplementary table 1.

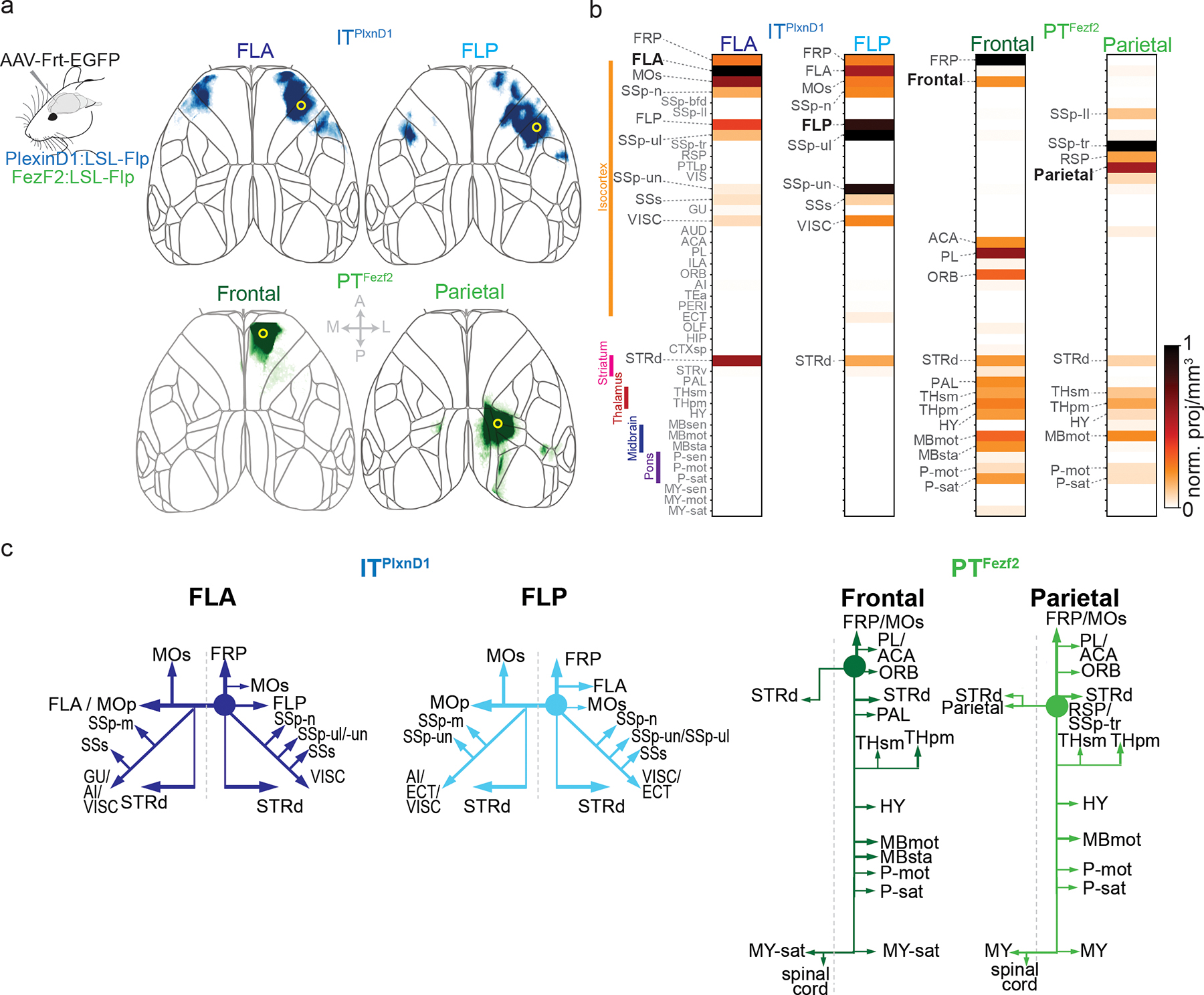

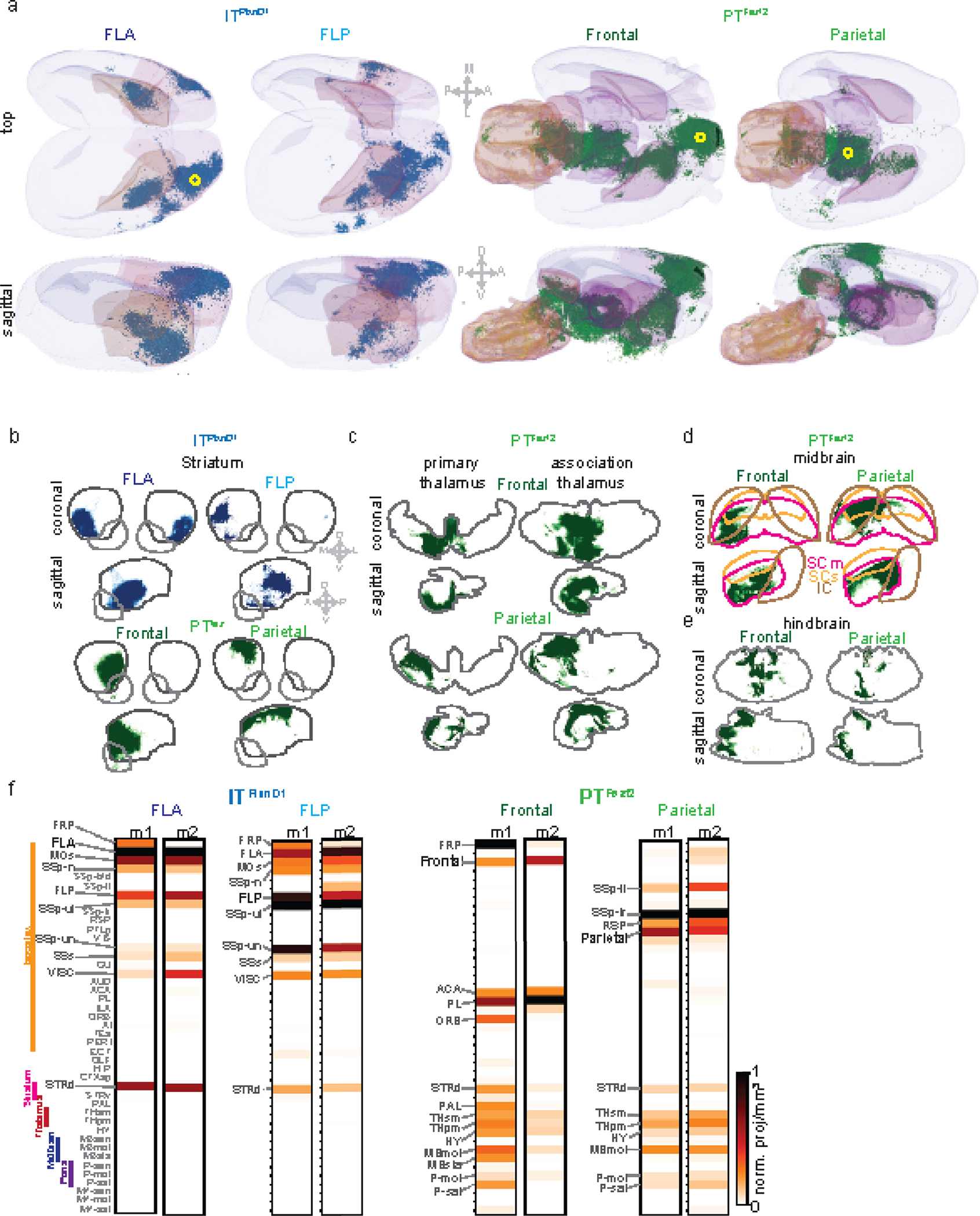

Distinct projections of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks

To explore the anatomical basis of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks revealed by wide-field calcium imaging, we examined their projection patterns by anterograde tracing using recombinase-dependent AAV in driver lines. Using serial two photon tomography across the whole mouse brain 48, we extracted the brain wide axonal projections and registered them to the Allen mouse Common Coordinate Framework (Methods, 49,50) and quantified and projected axonal traces within specific regions across multiple planes. With an isocortex mask, we extracted axonal traces specifically within the neocortex and projected signals to the dorsal cortical surface (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Brain wide projections of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 from frontolateral and parietofrontal networks.

a. Anterograde projections of ITPlxnD1 from FLA and FLP and PTFezf2 from frontal and parietal nodes within isocortex projected to the dorsal cortical surface from an example mouse.

b. Brain-wide volume and peak normalized projection intensity maps of ITPlxnD1 from FLA and FLP and PTFezf2 from frontal and parietal nodes from an example mouse. Black font indicates injection site; larger gray font indicates regions with significant projections; smaller gray font indicates regions analyzed.

c. Schematic of the projection of ITPlxnD1 from FLA and FLP and PTFezf2 from frontal and parietal nodes. Circle indicates the site of injection.

As expected, PTFezf2 in parietal and frontal regions show very little intracortical projections (Fig 6a, Extended data 8a, Suppl. Videos 13,14). PTFezf2 in frontal node predominantly project to dorsal striatum, pallidum (PAL), sensorimotor and polymodal thalamus (THsm, THpm), hypothalamus (HY), motor and behavior state-related midbrain regions (MBmot, MBsat), and motor and behavior state-related Pons within the hindbrain (P-mot, P-sat). PTFezf2 in parietal node projected to a similar set of subcortical regions as those of frontal node, but often at topographically different locations within each target region (Fig. 6b, Extended data 8b–e). To analyze the projection patterns, we projected axonal traces within the 3D masks for each region across its coronal and sagittal plane. PTFezf2 in parietal and frontal nodes both projected to the medial regions of caudate putamen (CP), with frontal node to ventromedial region and parietal node to dorsomedial regions (Extended data 8b); they did not project to ventral striatum. Within the thalamus, frontal PTFezf2 project predominantly to ventromedial regions both in primary and association thalamus while parietal PTFezf2 preferentially targeted dorsolateral regions in both subregions (Extended data 8c). Within the midbrain, frontal and parietal PTFezf2 specifically targeted the motor superior colliculus (SCm) with no projections to sensory superior colliculus or inferior colliculus. Within SCm, frontal PTFezf2 preferentially targeted ventrolateral regions while parietal PTFezf2 projected to dorsomedial areas (Extended data 8d). Together, the large set of PTFezf2 subcortical targets may mediate the intention, preparation, and coordinate the execution of tongue and forelimb movements during pellet retrieval and handling. In particular, the thalamic targets of parietofrontal nodes might project back to corresponding cortical regions and support PTFezf2-mediated cortico-thalamic-cortical pathways, including parietal-frontal communications40.

In contrast to PTFezf2, ITPlxnD1 formed extensive projections within cerebral cortex and striatum (Fig. 6b, Extended data 8b, Suppl. Videos 11,12). Within the dorsal cortex, ITPlxnD1 in FLA projected strongly to FLP and to contralateral FLA, and ITPlxnD1 in FLP projected strongly to FLA and to contralateral FLP. Therefore, ITPlxnD1 mediate reciprocal connections between ipsilateral FLA-FLP and between bilateral homotypic FLA and FLP (Fig. 6a). In addition, ITPlxnD1 from FLA predominantly project to FLP (MOp), lateral secondary motor cortex (MOs), forelimb and nose primary sensory cortex (SSp-ul, SSp-n), secondary sensory cortex (SSs) and visceral areas (VISC). Interestingly, ITPlxnD1 in FLP also projected to other similar regions targeted by FLA (Fig. 6b). Beyond cortex, ITPlxnD1 in FLA and FLP projected strongly to the ventrolateral and mediolateral division of the striatum, respectively (STRd, Fig. 6b, Extended data 8b). These reciprocal connections between FLA and FLP and their projections to other cortical and striatal targets likely contribute to the concerted activation of bilateral FLA-FLP subnetwork during pellet eating bouts involving coordinated mouth-hand sensorimotor actions. As driver lines allow integrated physiological and anatomical analysis of the same PN types, our results begin to uncover the anatomical and connectional basis of functional ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks.

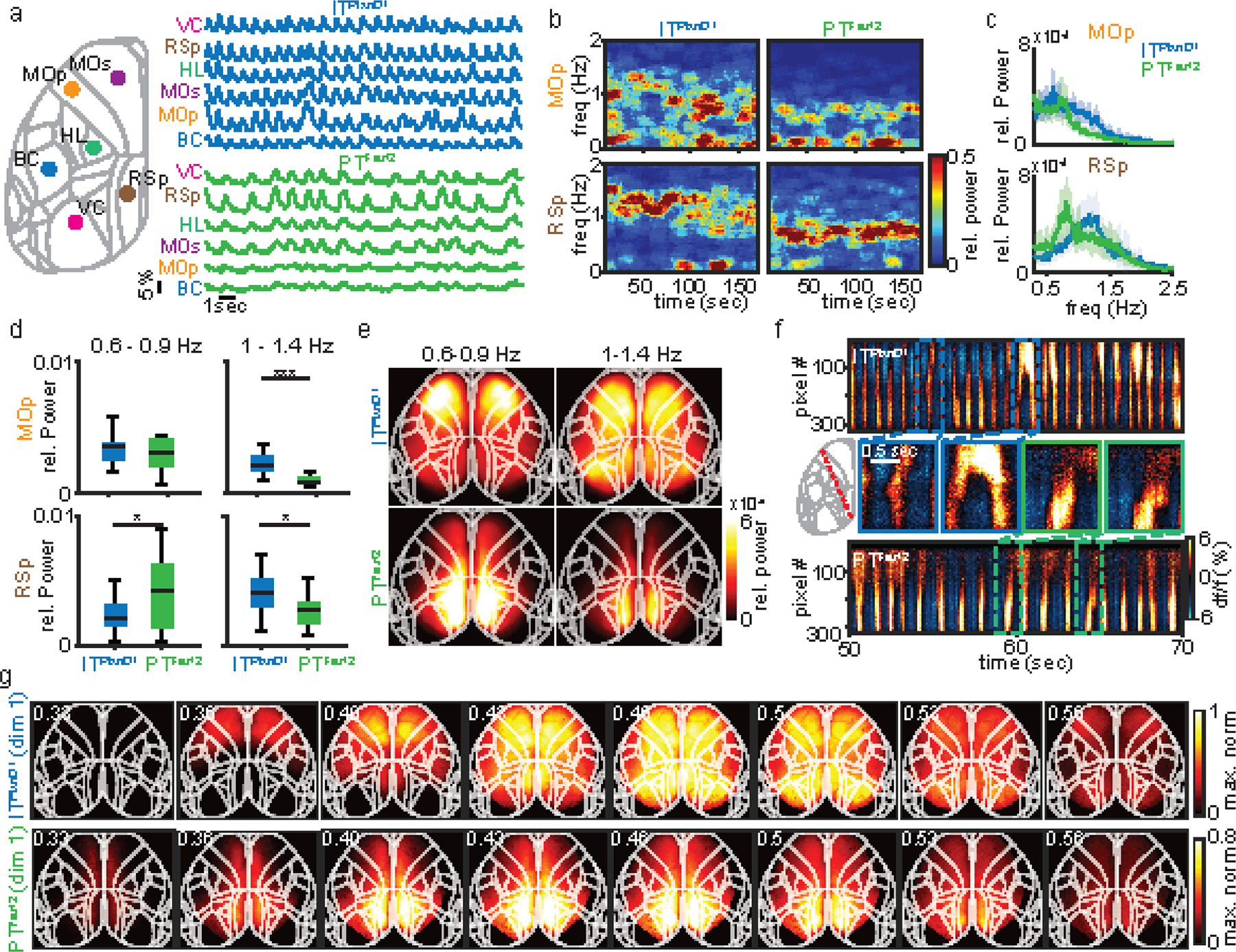

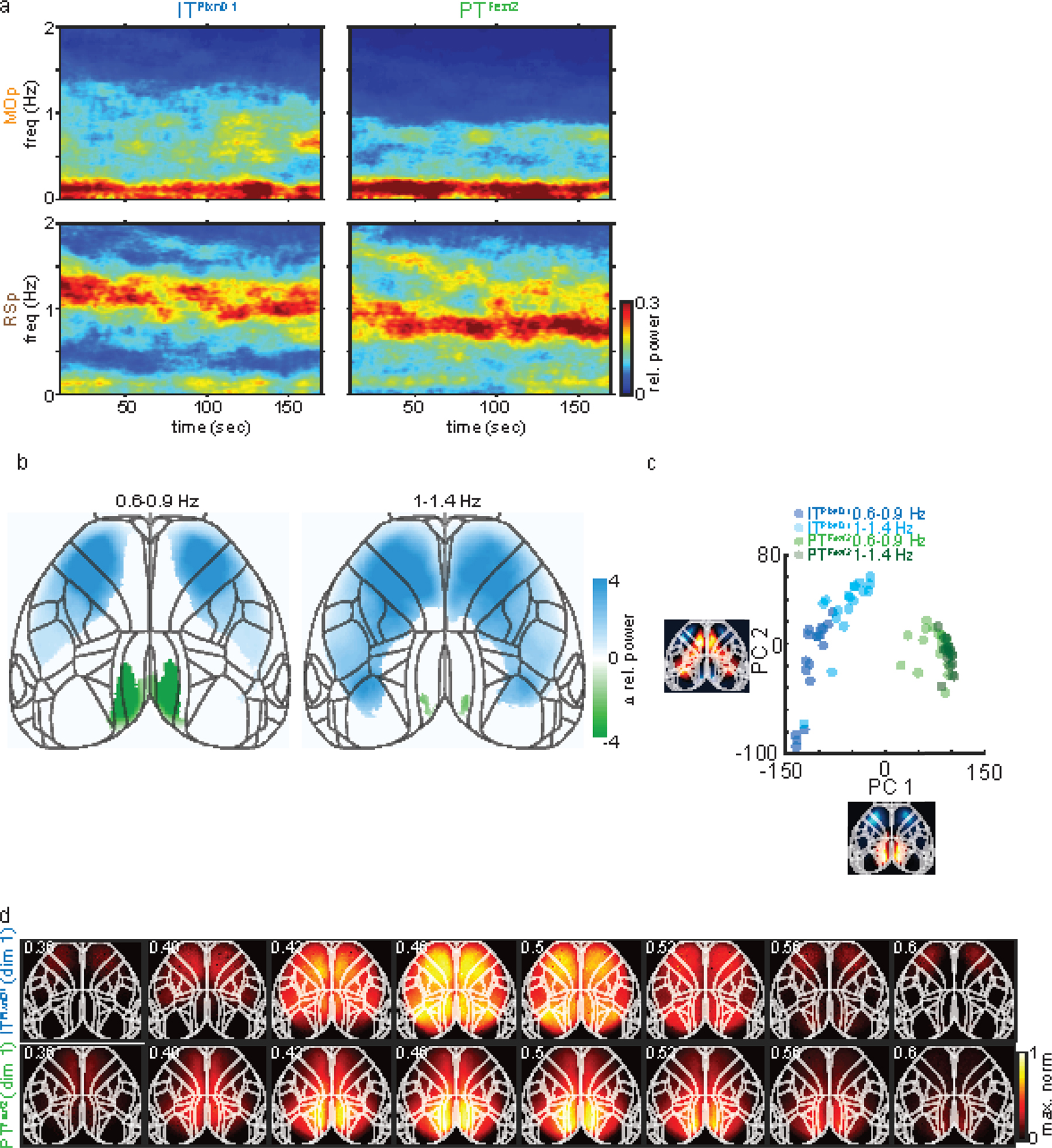

Distinct ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 dynamics under ketamine

Given the distinct spatiotemporal activation patterns of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during spontaneous and goal directed behavior, we further explored whether they differ in network dynamics in a dissociation-like brain state under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia 37,51. We found significant differences in both the temporal dynamics and spatial propagation of activities between the two cell types. ITPlxnD1 oscillated at a higher frequency compared to PTFezf2. Whereas ITPlxnD1 activities spread multi-directions across most of the dorsal cortex, PTFezf2 activities mainly propagated from retrosplenial toward the frontolateral regions (Extended data 9, 10, Suppl. Videos 15,16). These results show that even under an unconstrained brain state, ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 subnetworks operate with distinct spatiotemporal dynamics and spectral properties, likely reflecting their differences in biophysical, physiological 52, and connectional properties (e.g. Fig 6).

Discussion

Whereas early cytoarchitectonic analyses of cell distribution patterns identified numerous cortical areas53 and their characteristic laminar organization54,55, single cell recording revealed the vertical groupings of neuronal receptive field properties3,4. Since its formulation, columnar configuration as the basic units of cortical organization has been a foundational concept5, yet to date the anatomic basis and functional significance of “cortical columns” remain contentious56–58. Multi-cellular recordings and computational simulation led to the hypothesis of a “canonical circuit” template, which may perform similar operations across cortical areas6–8,59; but its cellular basis and relationship to global cortical networks remain unsolved. An enduring challenge for understanding cortical architecture is its neuronal diversity and wiring complexity10. Meeting this challenge requires methods to monitor and interpret neural activity patterns across cortical layers and areas with cell type resolution in real time and in behaving animals. Widefield calcium imaging in rodent cortex provide an opportunity to bridge cellular and cortex-wide measurement of neural activity22. Among diverse PNs, IT and PT represent two major top-level classes that mediate intracortical processing and subcortical output channels, respectively, with distinct gene expression12,60, developmental trajectories61, morphological and connectivity features41,52, biophysical properties 52, and functional specializations in specific cortical areas62,63 and behavior64–66. Here we demonstrate that ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 operate in separate and partially parallel subnetworks during a range of brain states and sensorimotor behaviors, and control distinct aspects of feeding movements. These results suggest a revision of the concept of cortical architecture predominantly shaped by the notion of columnar organization57; they indicate that dynamic areal and PN type-specific subnetworks are a key feature of cortical functional architecture that integrates microcircuit components and global brain networks. It is possible that columnar information flow between IT and PT, and thus the functional integration of corresponding subnetworks, might be dynamically gated by inhibitory and modulatory mechanisms according to brain states and behavioral demand.

Modeling and experimental studies have suggested that the source of signals measured by widefield imaging from cortical surface differs depending on the depth of cell body layer67 and is a weighted average of fluorescence originating across the cortical depth67,68. While a large proportion of signal originates from extra somatic layers, especially for deep layer neurons, a significant amount also arises from the cell body layer67. Additionally, the high correlation between calcium dynamics in cell body and apical dendrites suggest that dendritic signals closely reflect cell body dynamics42–46. Furthermore, GCaMP widefield signals are strongly associated with neuronal action potentials both at single cell resolution69 and across cortical depth in a local region38,70. Along with these limitations, it is important to note that GCaMP6f signals have relatively slow temporal dynamics (hundreds of milliseconds); complementary methods with better temporal resolution for spiking activities (e.g. electrophysiological recordings71) are necessary to decipher information flow and neural circuit operation.

The posterior parietal cortex (PPC) is an associational hub receiving inputs from virtually all sensory modalities and frontal motor areas, and supports a variety of functions including sensorimotor transformation, decision making, and movement planning72–74. PPC subdivisions are strongly connected with frontal secondary motor cortex in a topographically organized manner75,76, and this reciprocally connected network has been implicated in movement intension, planning, and the conversion of sensory information to motor commands77. The cellular basis of parietal-frontal network is not well understood73,78. Here we found that sequential and co-activation of parietal-frontal PTsFezf2 are the most prominent and prevalent activity signatures that precede and correlate with tongue, forelimb, and other body part movements. During the feeding task, training mice to eat without hands specifically occluded PTFezf2 parietal activation that normally precedes hand lift. Furthermore, optogenetic inhibition of PTFezf2 within the frontal node disrupts licking and hand lift, while inhibition of the parietal node disrupts hand-to-mouth movement trajectory. Together, these results suggest PTFezf2 as a key component of the parietal-frontal network implicated in sensorimotor transformation and action control. As PTsFezf2 do not extend significant intracortical projections, their co-activation in the parietal-frontal network might result from coordinated presynaptic inputs from, for example, a set of IT PNs that communicate between the two areas, or from cortico-thalamic-cortical pathways 40,79,80 linking these two areas. As the topographic connections between parietal and frontal subdivisions appear to correlate with multiple sensory modalities and body axis75,76,78, cellular resolution analysis using two-photon imaging and optogenetic recordings may resolve these topographically organized circuits that mediate different forms of sensorimotor transformation and action control.

While ITsPlxnD1 show broad and complex activity patterns during several brain states and numerous episodes of sensorimotor behaviors, we discovered a prominent FLP-FLA subnetwork that correlates with coordinated mouth and hand movements during feeding. Notably, this subnetwork is weakly correlated with pellet retrieval and handlift to mouth, when PTFezf2 in the parietal-frontal subnetwork showed strong activation. While FLP mostly comprises primary sensory areas of the orofacial and forelimb regions, FLA comprises frontolateral regions of primary and secondary motor areas. The prominent reciprocal ITPlxnD1 projections between these two areas and across bilateral FLP-FLA suggest an anatomical basis underlying the concerted activity dynamics of this functional subnetwork. Furthermore, optogenetic inhibition of ITPlxnD1 within frontolateral nodes resulted in finger movement deficits during pellet handling. Together, these results suggest a significant role of FLP-FLA subnetwork in the sensorimotor coordination of orofacial and forelimb movement during feeding.

Our focus on ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 populations in the current study does not yet achieve a full description of cortical network operations. Indeed, top-level classes further include cortico-thalamic, near-projecting, and layer 6b populations12; and the IT class alone comprises diverse transcriptomic12 and projection17 types that mediate myriad cortical processing streams81. Although ITPlxnD1 represents a major subset, other IT subpopulations remain to be recognized and analyzed using similar approaches. It is possible, for example, that another IT type might feature a direct presynaptic connection to PTFezf2 (e.g.7,41) and share a more similar spatiotemporal activity pattern and closer relationship to the PTFezf2 subnetwork. Finer resolution genetic tools for examining additional PN types will achieve an increasingly more comprehensive view of functional cortical networks. Furthermore, simultaneous analysis of two or more PN types in the same animal will be particularly informative in revealing their functional interactions underlying cortical processing.

Methods

Animals

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and Duke University.57 male and female mice were included as part of the study. All mice were housed in groups of at least 2 to 5 in 12 hours light/dark cycle. To express GCaMP6f within specific projection neuron (PN) population, 14 FezF2-CreER and 16 PlexinD1-CreER knockin mouse lines generated in the lab were crossed with Ai148 (The Jackson Laboratory, Strain #030328), a GCaMP6f reporter line. 3 VGAT-ChR2-EYFP (The Jackson Laboratory, Strain #014548) that express the blue light activated opsin ChR2 in GABAergic interneuron population were used for optogenetic manipulation. 6 PlexinD1-CreER and 4 FezF2-CreER crossed with a reporter line expressing LSL-Flp were used for viral expression of flp depended anterograde tracing. 4 PlexinD1-CreER and 3 FezF2-CreER mice were used for cell type specific inhibition experiments. 4 PlexinD1-CreER and 3 FezF2-CreER mice crossed with Ai148 were used for two photon imaging experiments. Expression of reporters were controlled via the intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen (20mg/ml, dissolved in corn oil) between 1 to 2 months postnatal. All mouse colonies at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) were maintained in accordance with husbandry protocols approved by the IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) and housed by gender in groups of 2 – 4 with access to food and water ad libitum and 12 hour light-dark cycle.

Surgical procedures

For widefield calcium imaging and optogenetic manipulation, adult mice older than 6 weeks were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane maintained between 1–2%. Ketoprofen (5 mg kg−1) was administered intraperitonially as analgesia before and after surgery, and lidocaine (2–4 mg kg−1) was applied subcutaneously under the scalp prior to surgery. Mice were mounted on a stereotaxic headframe (Kopf Instruments, 940 series or Leica Biosystems, Angle Two). An incision was made over the scalp to expose the dorsal surface of the skull and the skin pushed aside and fixed in position with tissue adhesive (Vetbond 3M). The surface was cleared using saline and an outer wall was created using dental cement (C&B Metabond, Parkell; Ortho-Jet, Lang Dental) keeping most of the skull exposed. A custom designed circular head plate was implanted using the dental cement to hold it in place. After cleaning the exposed skull thoroughly, a layer of cyanoacrylate (Zap-A-Gap CA+, Pacer Technology) was applied to clear the bone and provide a smooth surface to image calcium activity or for optogenetic stimulation 24. For viral injections, we followed the same anesthesia procedure. Under anesthesia, an incision was made over the scalp, a small burr hole drilled in the skull and brain surface was exposed. A pulled glass pipette tip of 20–30 μm containing the viral suspension was lowered into the brain; a 300–400 nl volume was delivered at a rate of 30 nl min−1 using a Picospritzer (General Valve Corp); the pipette remained in place for 10 min preventing backflow, prior to retraction, after which the incision was closed with 5/0 nylon suture thread (Ethilon Nylon Suture, Ethicon) or Tissueglue (3M Vetbond), and mice were kept warm on a heating pad until complete recovery 39. For cell type specific optogenetic manipulations, we first drilled through the skull using a 0.5 mm bur bilaterally over the frontal and frontolateral anterior areas in each mouse followed by viral injection (GtACR1) as described earlier. We then implanted Fiber optic cannulae (outer diameter 1.25 mm ceramic ferrule, 400 μm core, 0.39 NA, R-FOC-L400C-39A, RWD) placing them on surface of the brain without penetrating into tissue and sealed them to the skull using dental cement (Tetric EvoFlow, Ivoclar Vivadent AG) followed by head bar implantation.

Viruses

For cell type specific anterograde tracing we injected 300–400nl of flp dependent viral tracer (AAV2/8-Cag-fDIO TVAeGFP, UNC Vector Core) in FezF2-CreER;LSL-Flp mice at either the frontal node (1.7–1.85mm Anterior, 0.7mm lateral, 1.25 mm ventral) or the parietal node (−1.79 to −1.91 mm posterior, 1.25 to 1.35 mm lateral, 0.3–0.7 mm ventral) and in PlexinD1-CreER;LSL-Flp mice at either FLA (1.7 mm anterior, 2.25 mm lateral, 0.3–0.8 mm ventral) or FLP (0.3mm anterior, 3mm lateral, 0.4–0.8mm dorsal). For cell type specific optogenetic manipulation we injected ~400 nl of cre dependent GtACR1 (AAVDJ-Cbh-DIO-GtACR1-eYFP) bilaterally in both frontal and frontolateral nodes in each mouse between 300 – 800 μm deep. Mice were between 7 to 12 weeks during viral injection.

Whole-brain STP tomography and image analysis

Whole brain STP imaging was performed as described earlier 48. Briefly, perfused and post fixed brains of adult mice were embedded, cross-linked and imaged across coronal sections with a Chameleon Ultrafast-2 Ti:Sapphire laser. Images were further processed using imageJ/FIJI and adobe photoshop prior to analysis. To analyze GCaMP distribution and projection patterns of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2, each frame was background subtracted and aligned to 3D Allen map82 following which projection intensity in each brain region was computed. More detailed description of imaging and analysis in supplementary methods.

In Situ Hybridization

HCR in situ were performed as described83. Probes were ordered from Molecular Instruments. Mouse brain was sliced into 50 μm thick slices after PFA perfusion fixation and sucrose protection. Hybridization chain reaction in situ was performed via free floating method in 24 well plate. First, brain slices were exposed to probe hybridization buffer with HCR Probe Set at 37°C for 24 hours. Brain slices were washed with probe wash buffer, incubated with amplification buffer and amplified at 25°C for 24 hours. On day 3, brain slices were washed, counter stained with DAPI and mounted. PlexinD1 (546 nm), Fezf2 (546 nm) and Satb2 (647 nm) probes were used to examine overlaps between these markers.

Feeding behavior paradigm

We developed a novel behavior paradigm where in mice use an ethological behavioral sequence to capture, handle and feed on food pellets while being head fixed. Briefly, a food pellet is automatically dispensed onto a conveyer belt that delivers it to the head fixed mouse. The mouse then picks the pellet with its tongue to its mouth followed by bringing its hand to the mouth to manipulate and eat it. At the end of trial, the belt moves back to its starting position to initiate the delivery of a new pellet. Most mice can perform the task within two weeks of initiating training. Detailed description of the task and training protocol in supplementary methods.

Behavior tracking and classification

Using two high speed cameras (FL3-U3-13S2C-CS, Teledyne FLIR) fitted with varifocal lens (#COT10Z0513CS, B&H), we recorded behavior from both the front and left side of the mouse at 100 frames per second as they performed the task under IR illumination. We used DeepLabCut (v2.0.8) 47 to track a range of task components and body parts from both angles including the pellet, pellet holder, left wrist, lower lip, upperlip, nose, tongue tip, left three fingers and right three fingers (from front view). We developed custom algorithms that use these tracked features to identify and classify different behavior events including onset of lick, picking pellet into the mouth, hand lift and chewing events. To extract episodes of food handling, we built a long short term memory (LSTM) neural network classifier with 100 hidden units using MATLAB neural network tool box. Detailed description for classifying different events are in supplementary methods.

To identify hand position during optogenetic manipulation, we tracked the location of the first finger (Fig 5e) of one of the hands. Instantaneous hand velocity (speed) was quantified as the absolute value of the first derivative of the hand position with respect to time. To quantify deficits in handlift trajectory, we measured the absolute velocity of 15 Hz low pass filtered (to remove high frequency noise) hand trajectory during the lift episode and compared its integral between 0 to 1 second after hand lift between inhibition and control trials. Hands were considered close to mouth if the distance between finger and mouth was below a custom defined threshold. Inter finger distance was quantified by extracting the instantaneous Euclidean distance between the position of the 1st and 2nd finger (Fig. 5j). Control trials used for comparison were extracted from the closest non-inhibition trial preceding each inhibition trial. To compare effect of inhibition between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 (Extended data 7b,c), the first n control trials to match the sample size of inhibition trials were used to compute the distribution of difference between control and inhibition trials.

Wide-field calcium imaging

We used wide field imaging to simultaneously measure GCaMP6f activity across the dorsal cortex. The imaging system used was as described previously 24. Briefly, the cortical surface was illuminated with alternating blue (470nm) and violet (405nm) LEDs at 60 Hz. Images were acquired with a sCMOS (edge 5.5, PCO) camera. We used the 405 nm excitation signal to regress out hemodynamic signal from 470 nm excitation and to obtain calcium dependent ΔF/F. For spontaneous and ketamine anesthetized measurements, since activity was measured for 180 seconds continuously, signal was first detrended by fitting and subtracting a 7th order polynomial to the raw signal associated with 405 nm and 470 nm excitation (Suppl. Fig. 1c) prior to regressing out non-calcium dependent signal as described before. This resulting imaging rate of 30 frames per second after hemodynamic correction was used for all subsequent analysis of calcium activity. All widefield data were rigidly aligned to the Allen CCFv3 dorsal map using four anatomical landmarks; the left, center and right edges of the anterior ridge between the frontal cortex and the olfactory bulb and the lambda 24,82 there by allowing data to be combined across mice and sessions. Detailed description of imaging components and correction are in supplementary methods.

Optogenetic Manipulation

To disrupt cortical activity in VGAT-ChR2 mice during behavior, we built a laser scanning system that can direct laser stimulation unilaterally or bilaterally across the whole dorsal cortex surface. A collimated beam of blue light (470 nm) from a laser (SSL-473-0100-10TN-D-LED, Sanctity Laser) was fed into a 2D galvo system (GVS 002, Thorlabs) that was directed onto cortical surface using custom written software. The system contained an additional path to simultaneously visualize the cortical surface using a camera (BFS-U3-16S2C-CS, TELEDYNE FLIR). Using this system, we directed blue light with a beam diameter of 400 μm (full width half maximum) bilaterally at 30 Hz. Laser power at the stimulation site on the cortical surface was set between 10–15 mW. We bilaterally inhibited cortical areas identified from regions active during the feeding behavior task: FLA (1.6 mm anterior, 2.3 mm lateral), FLP(0.5mm anterior, 3.5 mm lateral), Frontal (2 mm anterior, 1 mm lateral) and Parietal (−1.2 mm posterior, 1.2 mm lateral). Using median onset times associated with lick, pellet in mouth and handlift from previous behavior trials, we turned on the stimulation prior to median lick onset time or during licking prior to median pellet in mouth onset time or after pellet in mouth but prior to median handlift onset time or after hand lift onset time during manipulation, bilaterally inhibiting each of the four ROIs for durations ranging from 5 to 7 seconds. The inhibition was randomly turned on between control trials where we did not provide any laser stimulation. For cell type specific manipulation, we used splitter branching fiber-optic patch cords (400 μm core, SBP(2) 1m FCM-2xZF2.5, doric) attached to the head of a 532 nm laser (GL532T3-100FC, SLOC Lasers). The output fibers were attached bilaterally to either the frontal or frontolateral anterior optic fiber implants during behavior for manipulation of either ITPlxnD1 or PTFezf2 neurons. Laser power was set between 5–8 mW. The inhibition protocol was as described earlier.

Neural and behavior data analysis

All neural and behavior analysis was performed on MATLAB v2018b and Python 3.8/3.9.

Wakeful resting state analysis

Mice were first habituated to head fixation in the setup as described earlier (supplementary methods). Calcium dynamics were recorded for 3 minutes at 30 fps with simultaneous behavior video recording at 20 fps. Both calcium activity and behavior videos were band pass filtered between 0.01 to 5 Hz. Variance from behavior video recordings were used to identify active and quiescent episodes. To quantify the amount of neural activity variance explained by behavior, we computed the Singular value decomposition (SVD) of both neural and behavior data. We then used a liner model to explain the top 200 temporal components of neural data using the top 200 temporal components of behavior video data as independent variables. We performed 5 fold cross validation of the model to obtain the cross validated R2 84. To quantify neural activity variance explained by each body part, we defined a window around each body part and extracted the average motion energy amplitude within each window. We then used a linear model to explain the top 200 SVD temporal components of neural activity data using the signal per body part as independent variables. We performed 5 fold cross validation of the model to obtain the cross validated R2 84. Detailed description of analysis in supplementary methods.

Sensory stimulation analysis

Before stimulation, mice were injected with chlorprothixene (1 mg/Kg i.p.) and maintained under light isoflurane anesthesia (0.8–1% with O2). We then placed a custom designed cardboard attached to two piezo actuators (BA5010, PiezoDrive) close to left whisker pad between whiskers and just below the upper and lower lip. We also placed an orange LED close to dorsal region of the left eye. We used an Arduino Uno Rev3 (A00006, Arduino) to drive the piezo and LED. A single trial consisted of 3 seconds baseline followed by whisker stimulation at 25 Hz for 1 second, 3 second delay, orofacial stimulation at 25 Hz for 1 second, 3 second delay, blinking visual stimulus at about 16 Hz for 1 second followed by 3 second delay before starting the next trial. We recorded one session per day consisting of 20 trials. To extract temporal traces, we used spatial maps obtained by averaging ITPlxnD1 activity per pixel during the 1 second stimulation period in response to each sensory stimulation. We identified centers of peak activity in each map and used a circular window of 560 μm diameter to extract signals within the circular mask and average them per frame. To compute activity intensity during sensory stimulation, we computed the integral of signals extracted from each roi for 1 second during the stimulation.

Two photon imaging and analysis

We used a Sutter movable objective microscope to measure single neuron calcium dynamics at 30.9 Hz over the left whisker somatosensory cortex. The location was identified using the peak activity following whisker stimulation from widefield imaging experiments. Each trial consisted of 3 seconds of baseline followed by 1 second whisker stimulation (as described previously) followed by another 3 seconds of post stimulus measurement. For each field of view, we measured responses across 20 trials. We recorded from cell bodies in ITPlxnD1 and apical dendrites of PTFezf2 (200 – 500 μm dorsoventral). We did not record from cell bodies in PTFezf2 since they were relatively dim due the depth. Dendritic calcium activity in layer 5B neurons has shown to be strongly correlated to cell body dynamics42–46. We used suite2p (https://www.suite2p.org/) to identify neurons and extract calcium dynamics followed by removal of neuropil activity and z-score computation for each neuron. To classify neurons, we used linear modelling to fit the response of each cell to a predictor variable containing ones during whisker stimulation and zeros otherwise. We used statsmodels module in Python to model the fit and obtain regression weights along with the associated statistical significance. Neurons with significantly positive regression weights (p<0.05) were classified as activated while those with significantly negative weights were classified as inhibited neurons. All other neurons were grouped as unclassified.

Feeding behavior analysis

To identify sequential activation pattern during feeding behavior, we extracted frames one second before and one second after pellet in mouth onset for all trials across mice and sessions. Since each frame is registered to the Allen CCFv3, we computed mean for each pixel at every sampling point to obtain an average activation map at each time point centered around pellet in mouth.

To identify activation maps associated with specific behavior event, we used a linear modelling approach. We used binary time stamps associated with each behavior event as independent variables to explain the top 200 SVD temporal components associated with neural activity. Spatial maps associated with each behavior event were obtained by computing the dot product between regression weights and spatial components of SVD. Detailed analysis is described in supplementary methods.

To identify the center of activation so as to extract temporal traces, we first calculated the average activity per pixel for 1 second before to 2 seconds after pim onset across mice and sessions (Fig. 3a,d). We then applied a mask containing mouth and nose primary sensory dorsal cortex region (as labeled by the Allen CCF V3) over the ITPlxnD1 activation map and identified center of peak activation and used it as the center of Frontolateral Posterior node (Fig. 3d, orange). Similarly we used MOs and MOp mask over ITPlxnD1 activation map to identify the center of Frontolateral Anterior node (Fig 3d, magenta). We used MOs mask over the PTFezf2 activation map to identify the center of frontal node (Fig 3a, dark brown) and a few cortical regions in the posterior area (RSPagl, VISam, VISa, SSp-tr, SSp-ll, SSp-ul, SSp-un, VISrl, SSp-bfd) to identify the center of parietal node (Fig 3a, light brown). We used a circular window mask of 560 μm diameter around these centers to extract signals within these masks and averaged them per frame to obtain temporal dynamics from each node. The Allen masks were used only to help identify the centers of peak activation and were not used to parcellate the cortex for any analysis.

To identify distinct activation clusters using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), we first combined temporal activity centered to PIM onset from all trials within an ROI from both PNs along the temporal dimension. We then concatenated the PN type class labels associated with each trial and performed LDA on the activity matrix and class labels using the LDA toolbox (LDA: Linear Discriminant Analysis, https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/29673-lda-linear-discriminant-analysis, MATLAB Central File Exchange. Retrieved December 28, 2021). We then projected the temporal activity matrix on the first two dimensions identified by the analysis and colored them based on PN type to visualize clusters.

Extended Data

Extended Data 1. ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activation patterns during wakeful resting state across mice.

a. Variance maps for each mouse (in columns) during quiescent and active episodes averaged over two sessions.

b. Distribution of variance during quiescent (Q) versus active (A) episodes in ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green) (n =12 sessions from 6 mice).

c. Difference between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 average variance maps for quiescent and active episodes (n=12 sessions from 6 mice). Only significantly different pixels are displayed (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with p-value adjusted by False Discovery Rate (FDR) = 0.05). Blue pixels indicate values significantly larger in ITPlxnD1 compared to PTFezf2 and vice versa for green pixels.

d. Distribution of Pearson’s correlation coefficients between quiescent variance maps within ITPlxnD1 (blue), PTFezf2 (green) and between ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 (blue green) (66 pairs within ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 and 144 pairs between ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 in 12 sessions from 6 mice for each cell type).

e. Distribution of Pearson’s correlation coefficients between active variance maps within ITPlxnD1 (blue), PTFezf2 (green) and between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 (blue green) (66 pairs within ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 and 144 pairs between ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 in 12 sessions from 6 mice for each cell type).

f. Distribution of ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green) active variance maps projected to the subspace spanned by the top two principal components.

g. Distribution of ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green) quiescent variance maps projected to the subspace spanned by the top two principal components.

h. Average maps of the 75th (top) and 95th (bottom) percentile df/f value during active and quiescent episodes for ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 (n =12 sessions from 6 mice). *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005. For box plots, central mark indicates median, bottom and top edges indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers extend to extreme points excluding outliers (1.5 times more or less than the interquartile range). All statistics in Supplementary table 1.

Extended Data 2. Spontaneous activity comparison and correlation of sensory response in ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 across mice.

a. Probability distribution of df/f values from ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green) during wakeful resting state (average of 12 sessions from 6 mice each, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

b. Mean peak df/f maps of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 during spontaneous behavior (average of 12 sessions from 6 mice for each cell type).

c. Difference between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 mean peak df/f maps. Only significantly different pixels are displayed (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with p-value adjusted by FDR = 0.05). Note that no pixels are significantly different.

d. Mean temporal dynamics of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity with (colored) and without (black) hemodynamic correction from hindlimb sensory area during spontaneous behavior. Activity is aligned to the onset of spontaneous movements (ITPlxnD1: 367 and PTFezf2: 474 trials in 12 sessions from 6 mice each, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m). Left image with red dot indicates location used to extract signal.

e. Left: Distribution of difference between hemodynamic corrected and uncorrected peak df/f value between 0 to 1 sec after spontaneous movement onset for ITPlxnD1 (blue) and PTFezf2 (green) from panel d. Right: Distribution of Pearson’s correlation coefficient between hemodynamic corrected and uncorrected ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 activity from panel d. (ITPlxnD1: 367 and PTFezf2: 474 trials).

f. Mean peak normalized activity maps of ITPlxnD1 (top) and PTFezf2 (bottom) in response to corresponding unimodal sensory simulation (n=12 sessions from 6 mice each).

g. Distribution of Pearson’s correlation coefficients between sensory activation maps within ITPlxnD1 (blue), PTFezf2 (green) and between ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 (blue green) (66 pairs within ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 and 144 pairs between ITPlxnD1 & PTFezf2 in 12 sessions from 6 mice each for all stimulations). *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005. For box plots, central mark indicates median, bottom and top edges indicate 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers extend to extreme points excluding outliers (1.5 times more or less than the interquartile range). All statistics in Supplementary table 1.

Extended Data 3. Calcium dynamics of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 at cellular resolution reflect widefield responses.

a. Schematic of the whisker stimulation paradigm and the cortical location for two photon imaging (blue circle).

b. Left: Example field of view (FOV) of ITPlxnD1 cell bodies and apical dendrites of PTFezf2 in the whisker barrel cortex. Right: Example traces from single ITPlxnD1 cell bodies and apical dendrites of PTFezf2. Numbers indicate the corresponding location on the FOV. Magenta bars indicate whisker stimulation events.

c. Heat map of average single neuron responses of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 classified into 3 groups based on their activity during whisker stimulation from the example FOV.

d. Average responses across all ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons within each group from the example FOV (shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m). Magenta bars indicate duration of whisker stimulation.

e. Average responses across all ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons from the example FOV (shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

f. Heat map of average single neuron responses of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 classified based on their activity during whisker stimulation across all mice and sessions (ITPlxnD1 42 FOV’s from n = 4 mice and PTFezf2 36 FOV’s from n = 3 mice).

g. Average responses across all ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons within each group across all mice and sessions (ITPlxnD1 42 FOV’s from n = 4 mice and PTFezf2 36 FOV’s from n = 3 mice, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

h. Average responses across all ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 neurons from all mice and sessions combined (ITPlxnD1 42 FOV’s from n = 4 mice and PTFezf2 36 FOV’s from n = 3 mice, shaded region indicates ±2 s.e.m).

i. Proportion of neurons in each group from ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2.

Extended Data 4. Temporal dynamics of ITPlxnD1 and PTFezf2 within parietofrontal and frontolateral networks centered to lick and hand lift onset.