Abstract

Antithrombin (AT) is a natural anticoagulant pivotal in inactivating serine protease enzymes in the coagulation cascade, making it a potent inhibitor of blood clot formation. AT also possesses anti-inflammatory properties by influencing anticoagulation and directly interacting with endothelial cells. Hereditary AT deficiency is one of the most severe inherited thrombophilias, with up to 85% lifetime risk of venous thromboembolism. Acquired AT deficiency arises during heparin therapy or states of hypercoagulability like sepsis and premature infancy. Optimization of AT levels in individuals with AT deficiency is an important treatment consideration, particularly during high-risk situations such as surgery, trauma, pregnancy, and postpartum. Here, we integrate the existing evidence surrounding the approved uses of AT therapy, as well as potential additional patient populations where AT therapy has been considered by the medical community, including any available consensus statements and guidelines. We also describe current knowledge regarding cost-effectiveness of AT concentrate in different contexts. Future work should seek to identify specific patient populations for whom targeted AT therapy is likely to provide the strongest clinical benefit.

Keywords: anticoagulation, heparin, cost, thrombosis, trauma

Introduction

The delicate balance of the coagulation system is achieved by appropriate activation and inhibition of procoagulant and anticoagulant proteins. If this balance is disturbed, hemorrhage, thrombosis, or thromboembolism can occur. Antithrombin (AT) is one of the most abundant and important regulators of the coagulation pathway. 1 The regulatory action of AT is accomplished by inhibition of the formation of thrombin and inactivation of multiple procoagulant serine proteases. 2

AT is secreted by the liver at a normal concentration of 0.125 to 0.160 mg/mL (80%-120%) 3 and is found in the plasma, vascular endothelium, and extravascular space. 4 The anticoagulant effect of AT is the mechanism behind the use of heparin in the treatment and prophylaxis of thrombosis, as the binding of heparin with AT induces a conformational change that drastically increases the potency of AT to inhibit the coagulation cascade. 5 In addition to modulating coagulation, AT can also stimulate the release of molecules that reduce inflammation. 6

Hereditary or acquired deficiencies in AT are associated with impaired endogenous coagulation and increased risk of thrombosis. 7 Supplementation with AT concentrate (ATc) can help restore normal hemostasis and reduce inflammation in patients with AT deficiency in states of hypercoagulability, including surgery and pregnancy. 6 Only 1 formulation of ATc is currently marketed in the United States: human plasma-derived ATc (Thrombate III, Grifols/Talecris, Barcelona, Spain). 8 ATc is approved in the United States in patients with hereditary AT deficiency for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolism and for the prevention of perioperative and peripartum thromboembolism.8,9

Given the potential for hemostatic and anti-inflammatory benefits associated with ATc, there are a plethora of studies describing investigation of additional uses for ATc.10–15 For example, AT therapy may benefit the treatment of individuals with sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, previously known as veno-occlusive disease (SOS/VOD), 11 heparin resistance,10,13 and sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). 15 Other works describe benefits to AT therapy during asparaginase therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 13 extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), 12 and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). 14 Recent evidence also suggests that AT plays a role in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), 16 hemorrhagic shock, 17 and in modulation of tumor cell activity. 18

The aim of this review is to integrate the existing evidence surrounding the use of ATc, including potential additional patient populations where AT therapy can be considered, and to describe current knowledge regarding cost-effectiveness of ATc in different contexts. The synthesis of this information will provide valuable insight to healthcare providers that can help to optimize their clinical decision-making, strategize healthcare resource utilization, and improve patient outcomes.

Antithrombin

Mechanism of Action

AT is a hepatic glycoprotein of the serpin superfamily, a collection of proteins with characteristic inhibitory and conformational features. AT targets and inhibits serine proteases activated (a) factor (f) II (thrombin) and fXa, as well as fIXa, fXIa, fXIIa, and fVIIa. 2 Although there are in vitro reports of heparin having AT-independent actions,19,20 AT is required for therapeutic anticoagulation by heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH); heparin alone has no direct anticoagulant effect. 21 Heparin induces a conformational change in AT that increases its inhibitory binding affinity by 1000-fold (Figure 1). 5

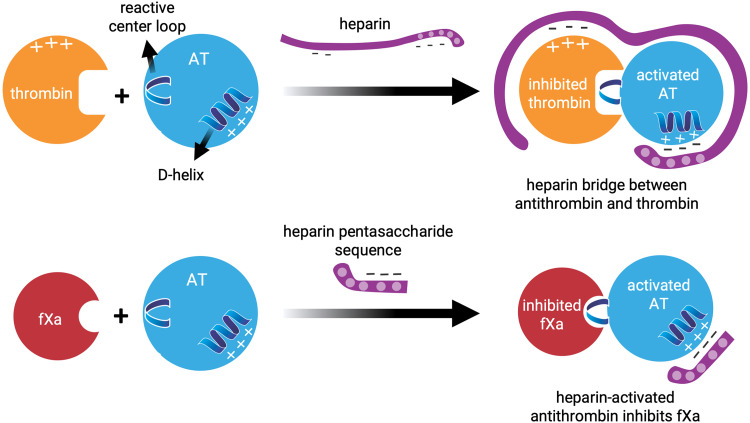

Figure 1.

The anticoagulant effect of heparin occurs via the binding of antithrombin with thrombin and activated factor X (fXa).

Both heparan sulfate and heparins—including unfractionated heparin (UFH) and LMWH, which are fragments of UFH produced by depolymerization—exert their anticoagulant activity by binding AT through a common sequence-specific pentasaccharide, which induces exposure of the AT reactive site and activation of AT (Figure 1).5,22 Heparin forms a bridge between AT and thrombin, promoting rapid inhibition, by AT, of coagulation proteases. 22 Therefore, the interaction of AT with heparin is the underpinning of the sophisticated system of time- and location-dependent regulation of hemostasis, as AT prevents the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin and of fibrinogen to fibrin, halts the completion of clot formation, reduces cytokine secretion, minimizes neutrophil–endothelial interactions, and decreases platelet and endothelial cell activation (Figure 2).

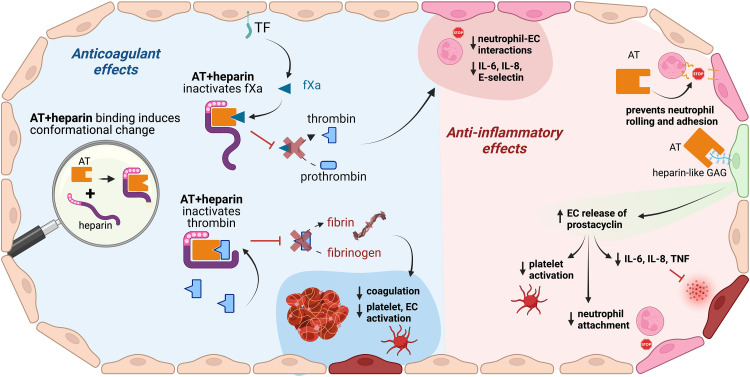

Figure 2.

Antithrombin mechanism of action: anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory effects. AT exerts both anticoagulant (left side of the figure) and anti-inflammatory (right side of the figure) effects. Created with BioRender.com. Abbreviations: AT, antithrombin; EC, endothelial cell; fXa, activated factor X; GAG, glycosaminoglycans; IL, interleukin; TF, tissue factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

For 35 years, AT has been known to exert anti-inflammatory effects, with recent molecular investigations revealing a 2-fold mechanism: (1) by binding to endothelial cell receptors that induce release of prostaglandin I2, which inhibits platelet activation and suppresses neutrophil interactions with the endothelium, and (2) by directly binding to specific cellular receptors that reduce the pro-inflammatory response by inhibiting cytokine expression.23–25 A detailed description of the molecular mechanisms associated with AT and its dynamics in coagulation and inflammation has been previously published. 25 Taken together, the anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory actions of AT make it an essential component of hemostasis with roles in a wide array of clinical conditions.

Antithrombin Concentrate

First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1991, ATc is prepared from human plasma pools and is used for the treatment of hereditary AT deficiency and for the treatment and prevention of perioperative or peripartum thromboembolism. 8 Because ATc is derived from human blood, there is a risk of transmission of infectious agents such as viruses or the Creutzfeldt–Jakob agent, but no cases of transmission have been reported. To address any potential risk of transmission, plasma donors are screened and ATc is fractionated and heated to destroy infectious agents without diminishing biologic activity. In the 2 clinical studies conducted during the investigation of human plasma-derived ATc (N = 33 subjects, N = 389 infusions, total), 9 subjects (27%) experienced 29 adverse reactions during 17 infusions (4.4%), and no serious adverse reactions were reported. All adverse reactions were of mild or moderate severity except for an event classified with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred term of “wound secretion and hematoma,” which was severe. The most common adverse reactions that occurred in at least 5% of subjects were dizziness, chest discomfort, nausea, dysgeusia, and pain (cramps). 8

One 10-mL vial of ATc contains 500 units, which is the equivalent of two 250-mL bags of fresh frozen plasma (FFP). 8 Dosing of ATc should be individualized to achieve a peak target AT level of 80% to 120% of normal. The required loading dose is calculated using the following formula:

The maintenance dose should be 60% of the loading dose, administered every 24 h. Administration of 1 dose of ATc usually takes 10 to 20 min and is typically well tolerated, but allergic-type hypersensitivity reactions are possible. 8 ATc is designed to interact with the endogenous anticoagulant system and can alter the effect of other drugs that interact with AT. 8 Therefore, close clinical and laboratory monitoring should be used to optimize anticoagulation in patients receiving ATc, particularly if the patient is at high risk of hemorrhage or if ATc is administered simultaneously with heparin.

Antithrombin Deficiency

AT deficiency is an acquired or hereditary condition of hypercoagulability due to low levels of AT, which is associated with an increased risk of thrombosis. 7

Hereditary Antithrombin Deficiency

Hereditary AT deficiency is the most severe and longest-known inherited thrombophilia, first described by Egeberg almost 60 years ago. 26 In the general population, hereditary AT deficiency affects 1 in 500 to 1 in 5000 persons.27,28 Recent advances in high-throughput nucleotide sequencing reveal this to be an underestimation, as the clinical presentation of AT deficiency is heterogeneous and diagnostic assays have limited thresholds of detection. For example, in 1 study of 400 individuals with venous thrombosis, sequencing revealed AT mutations in 4% of patients overall and, unexpectedly, in 5% of participants who had normal AT activity levels. 29 A genetic sequencing study of individuals from the general population, such as by screening blood donors, does not exist but is needed to provide additional insight into the rate of missed diagnosis of hereditary AT deficiency.

Hereditary AT deficiencies result from variants in the gene that encodes the AT protein, SERPINC1.30,31 Inheritance is usually autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. 32 The condition is almost always heterozygous, as the homozygous state is incompatible with survival except for some rare cases of variants that affect only the heparin-binding site. 33

Hereditary AT deficiency is categorized into 2 types: type I, a deficiency in AT levels, and type II, in which AT antigenic levels are normal but functional activity is reduced. These are often referred to as quantitative deficiency (type I) and qualitative deficiency (type II). Type I AT deficiency tends to be caused by nonsense or null variants of SERPINC1 that lead to a reduction in AT concentration and activity of ∼50%. Type I is more common than type II among patients with symptoms of thrombophilia and their family members, up to 80%. 34 Patients with type I deficiency often have a family history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and may develop thrombosis early in life. Women with confirmed or suspected type I AT deficiency require careful evaluation and counseling related to pregnancy, contraception, and menopausal hormone therapy due to the known link between estrogen use and thrombosis. 35

Type II AT deficiency is usually caused by missense mutations in SERPINC1 that result in a molecular defect in the protein. The defect interferes with the interaction between AT and its target proteases, reducing its anticoagulant function, though the immunological activity of AT is maintained and AT antigenic levels tend to remain normal (Figure 3). In the general population, type II AT deficiency is twice as common as type I 27 and is thought to be associated with lower risk of VTE. 30 The exception is type II variants that specifically affect the reactive site of AT, which carry a high risk of thrombosis. 28 Studies of blood donors suggest that the majority of cases of type II in the general population are undetected. 27

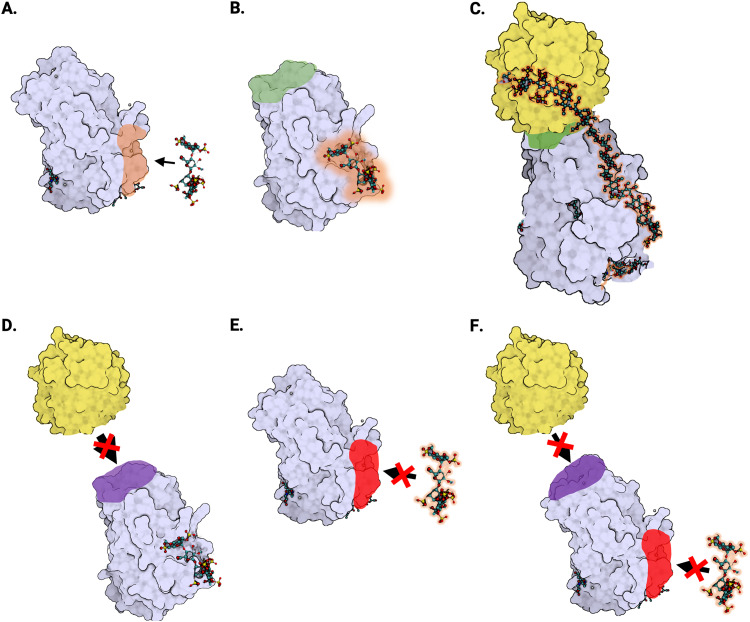

Figure 3.

Protein structure of antithrombin and type II antithrombin deficiencies. (A) Crystal structure of native antithrombin in its monomeric form (Protein Data Bank [PDB] identifier: 1T1F). The antithrombin protein (lavender) with heparin-binding site (orange) is shown near the heparin pentasaccharide fragment (ball-and-stick) that binds and activates antithrombin. (B) Anticoagulant activation of antithrombin by heparin (PDB: 1AZX). When the heparin pentasaccharide fragment (ball-and-stick) binds to antithrombin (lavender), it alters the conformation of the antithrombin reactive site (green), resulting in a 1000-fold increase in the inhibitory activity of antithrombin against its target proteases. (C) Antithrombin–thrombin–heparin ternary complex (PDB: 1TB6). Thrombin (yellow) binds to the reactive site (green) of antithrombin (lavender). Heparin (ball-and-stick) interacts with both thrombin and antithrombin, creating a thrombin–antithrombin bridge. (D) Type II reactive site (RS) deficiency. In antithrombin deficiency type IIa or type II reactive site (IIRS), there is a defect in the reactive site (purple) that interferes with the ability of antithrombin (lavender) to bind its target proteases, including thrombin (yellow). (E) Type II heparin-binding site (HBS) deficiency. In antithrombin deficiency type IIb, also known as type II heparin-binding site (IIHBS), there is a defect in the heparin-binding site (red) that interferes with the ability of antithrombin (lavender) to bind heparin (ball-and-stick). (F) Type II pleiotropic effect (PE) deficiency. In antithrombin deficiency type IIc, also known as type II pleiotropic effects (IIPE), there is a defect in the antithrombin protein (lavender) that interferes with both the reactive site (purple) and the heparin-binding site (red).

According to the Antithrombin Mutation Database, there are 3 subtypes of type II deficiency, broadly defined by the type of defect in the AT protein (Figure 3). 36 The first subtype involves a defect in the reactive site of AT due to 1 of at least 12 known SERPINC1 variants.

This subtype has traditionally been known as type IIa and more recently as type II reactive site (IIRS). Type IIRS defect reduces the ability of AT to bind with its target proteases—including thrombin—and tends to be less common but more thrombophilic than the other type II subtypes. 37

The second subtype, known as type IIb or type II heparin-binding site (IIHBS), is characterized by a defect in the heparin-binding site of AT (Figure 3). Type IIHBS interferes with the ability of AT to bind heparin, which reduces the anticoagulant effect of AT. Individuals with type IIHBS defect have a lower risk of VTE but a higher risk of arterial thromboembolism compared to other types of AT deficiency. 30 In some patients with ischemic stroke, knowledge of IIHBS diagnosis can be a useful prognostic factor. 38

The third subtype, known as type IIc or type II with pleiotropic effects (IIPE), typically involves a defect in the structure of AT near the reactive site (Figure 3). In type IIPE, there is a single genetic mutation that results in more than one functional defect in the AT protein. Individuals with this subtype tend to have lower AT levels than other type II subtypes. Type IIPE and type IIRS tend to be associated with more severe thrombophilic phenotypes than type IIHBS. The advent of next-generation sequencing has led to an explosion in investigations of SERPINC1 variants of both type I and type II, most often initiated to explore cases of familial thrombosis.31,39–41

After sequencing, bioinformatic analyses are used to link variant genotypes to the structure and function of the AT protein and to detect associations between protein defects and disease phenotypes.39–41 Recent work points to the importance of environmental factors on the phenotype of some variants, with a new potential classification termed transient hereditary AT deficiency. 42 These genotypic/phenotypic studies and molecular analyses may eventually have potential in the prognostication of VTE, but their interpretation is currently nuanced and direct clinical applications are not clear. The usefulness of genetic associations can be expected to expand as sequencing technology and personalized medicine become more conventional practice.

Acquired Antithrombin Deficiency

AT deficiency can be acquired due to a variety of conditions that affect the synthesis, accumulation, and depletion of AT; 28 these will be described in subsequent sections. Briefly, acquired plasma AT deficiency can arise secondarily from a range of disorders including liver dysfunction, premature infancy, nephrotic syndrome, chylothorax, inflammatory bowel syndrome, malnutrition, or severe burns, or as a result of interventions such as major surgery or cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Acquired AT deficiency can also be induced by heparin therapy, asparaginase therapy for ALL, or by sepsis-DIC.

Burden of Illness

The most common presentation of AT deficiency is VTE, which is a major health problem in the United States, especially among pregnant women and individuals undergoing surgery. 43 An estimated 50% of individuals with AT deficiency develop VTE by the age of 50 years, 28 but the absolute risk of first and recurrent VTE for individuals with AT deficiency varies due to environmental and genetic factors that exert a complex influence on presentation. Children with inherited AT deficiency have a 300-fold increase in thrombotic risk compared to the general population 44 and a 7.1-fold increased risk of ischemic stroke or cerebral sinovenous thrombosis. Notably, the normal reference intervals for AT levels in children (7-17 years) are higher than for adults; if adult reference intervals are used to evaluate children, AT-deficient children will be misdiagnosed as normal. 45 Despite early misconceptions that VTE was uncommon in the non-White population, prospective and case–control studies have reported comparable VTE risks conferred by AT deficiency across different ethnic groups.32,46 Risk ratios for VTE are cumulative and are known to be much higher in individuals with AT deficiency compared to other thrombophilic conditions, ranging from 10 to 50.47,48

Treatment of Antithrombin Deficiency

Treatment of individuals with AT deficiency is dependent on clinical presentation and must be personalized but generally falls into 3 categories: treatment of acute VTE, short-term thromboprophylaxis in high-risk clinical settings, and long-term anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis in symptomatic patients. For the treatment of acute VTE, first-line therapy is heparin or LMWH. Anticoagulation by heparin is biochemically dependent on AT, such that the treatment of acute VTE in patients with AT deficiency requires special consideration. A common approach in these patients is replacement or enrichment of AT through administration of ATc or transfusion of FFP.10,49 Guidelines recommend use of FFP only if ATc is not available, as transfusion of FFP carries risks including potential circulatory overload, allergic reaction, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), infection transmission, hemolytic transfusion reaction, and alloimmunization. 50 As reported by Beattie and Jeffrey, the treatment of heparin resistance with FFP may not restore the activated clotting time (ACT) to therapeutic levels with adequate heparinization, but ATc is safe and efficient with benefits including less risk of TRALI and transfusion-related infections, as well as lower volume administration. 10

Individuals with AT deficiency who are asymptomatic require short-term thromboprophylaxis in high-risk clinical settings such as surgery and pregnancy.51,52 Surgery stimulates classical external prothrombic factors including vascular endothelial damage and blood flow stasis, while pregnancy causes hypercoagulability and progesterone-induced venous dilatation. 51 ATc is approved in the United States for the prevention of perioperative and peripartum thrombosis in patients with hereditary AT deficiency. 9 Due to the substantial heterogeneity of clinical presentation, medical history, potential comorbidities, and risk factors, a personalized approach is required to effectively manage individual thrombotic risk.

In symptomatic patients with AT deficiency, long-term anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis is required; warfarin is considered a reliable and well-understood therapy known to increase AT levels, though it carries a risk of major hemorrhage, and non-adherence is a substantial problem. 53 In addition, some patients prefer not to be committed to long-term anticoagulation by warfarin due to the risk of bleeding and associated necessary lifestyle changes, inconvenience of dietary interactions, and required frequent laboratory monitoring. 54 Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are a safe and effective first-line therapy alternative to warfarin for long-term anticoagulation, 55 with 5 products recently approved by the United States FDA for the prevention of VTE in adults and 2 for the same use in children.56–58 A prospective cohort study, which included 29 patients with inherited AT deficiency, demonstrated safety and efficacy of DOACs similar to that of heparin and vitamin K agonists in treating VTE. 59 An earlier meta-analysis of 8 studies and 476 patients, of whom 15 were individuals with inherited AT deficiency treated with DOACs, reported similar results. 60 DOACs can cause erroneous AT test results by falsely increasing levels of AT activity, 61 so AT testing for patients treated with DOACs should be performed in a specialized or research laboratory. Test interference from DOACs can be managed with activated carbon, 62 the DOAC-Stop procedure, 63 or by using factor II-based chromogenic assays. 64 In the context of individualized treatment plans and difficult-to-manage cases, ATc can be given during pregnancy if a patient is intolerant of DOACs and does not respond well to heparin or in combination with DOACs for the treatment or prevention of acute thrombotic episodes. 53

Testing and Diagnosis of Antithrombin Deficiency

Testing for AT deficiency can be controversial, as a diagnosis does not always result in therapeutic changes and the cost of testing can be substantial. However, diagnosis of individuals with AT deficiency does expand the anticoagulant therapeutic arsenal available to healthcare providers, as these individuals can benefit from supplemental ATc.

Results from retrospective studies of families with AT deficiency indicate potential benefit to screening of asymptomatic relatives, for whom primary thromboprophylaxis during high-risk clinical settings can reduce the incidence of thrombotic events. 65 Individuals with a positive diagnosis can also benefit from avoiding oral contraceptives and hormone therapy. 66 There is strong evidence for increased risk of thrombosis in children with hereditary AT deficiency, especially during the newborn period due to developmentally lower levels of AT and in adolescence (12-18 years) due to similar triggers as in adults (pregnancy, surgery, and oral contraceptives). 44 These data support testing for AT deficiency to optimize preventative measures in adults, infants, and children with family history of VTE or known AT deficiency, particularly as prevention of VTE can offset the cost burden of testing.

Testing should be avoided if the individual is receiving full-dose heparin or LMWH, which can cause minor decreases in AT. 67 The AT assay type should be chosen carefully if the individual is taking warfarin, as warfarin can falsely increase AT activity when an older serum-based assay is used 68 but does not interfere with newer methods that use citrated plasma as the specimen. 67

A functional AT activity assay is required for diagnosis of AT deficiency because AT can be quantitatively normal but qualitatively defective. 67 Functional assays measure the ability of AT to inhibit thrombin or fXa in the presence of heparin. Levels of AT that are clearly below the normal range (ie, < 80%) are suggestive of AT deficiency; most AT-deficient patients have levels <70%. AT levels of 70% to 80% are considered borderline, and a follow-up measurement should be taken to confirm diagnosis. Testing of family members is recommended after careful counseling if a diagnosis may influence patient decision-making, particularly for women considering oral contraceptives or pregnancy.47,66 It is advisable to conduct AT deficiency testing on both adults and children with family history who have experienced early, extensive arterial or venous thrombosis and have a clot located in an uncommon area. Overall, the usefulness of testing and diagnosis for AT deficiency should be determined on an individual patient basis, as testing enables a personalized approach to disease management and can mitigate risks in family members.

Additional Patient Populations and Use Cases Where AT Therapy May Be Considered

Optimal patient care requires that providers be free to use their best judgment and understanding of medical knowledge, which tends to advance more rapidly than labeling revisions. 69 However, off-label prescribing presents challenges regarding limited information on effectiveness and safety, which are the responsibility of the provider to navigate in the context of each patient's medical history and clinical status. 70 Importantly, in the context of ATc, the optimal AT level is not clearly defined for off-label indications and the available evidence for safety and effectiveness is variable according to each potential use case. The aim of this section is to summarize the literature surrounding potential patient populations and use cases where AT therapy has been considered by the medical community, including any available consensus statements and guidelines (Table 1).

Table 1.

Currently Approved, Reported, Emerging, and Investigational Uses for AT Therapy.

| Category | Use |

|---|---|

| Approved | Treatment of hereditary AT deficiency |

| Treatment and prevention of perioperative or peripartum thromboembolism | |

| Reported | Management of heparin resistance in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| Treatment and prevention of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease | |

| Prevention and management of VTE throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period | |

| Management of heparin resistance in patients who require cardiopulmonary bypass | |

| Anticoagulation in critically ill patients undergoing CRRT | |

| Thromboprophylaxis in pediatric patients with chylothorax | |

| Protection from coagulopathy in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing asparaginase therapy | |

| Treatment of sepsis and sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation | |

| Emerging | Thromboprophylaxis and management of heparin resistance in individuals with COVID-19 |

| Thromboprophylaxis and management of hemorrhagic shock in critically injured trauma patients | |

| Investigational | Decrease of tumorigenic protein expression and activation of resistance pathways in glioblastoma multiforme cells |

| Inhibition of metastasis and angiogenesis in colorectal and lung cancer cell lines |

Abbreviations: AT, antithrombin; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Patients Undergoing ECMO

ECMO is a form of supportive care for critically ill patients in which the blood is oxygenated using an external artificial circuit. The contact between blood and the biomaterials of the artificial circuit creates a procoagulant state that requires systemic anticoagulation, usually with UFH. 71 Up to 50% of patients receiving ECMO experience heparin resistance, especially with prolonged heparin exposure.72,73 When heparin resistance occurs the relative contributions of different factors can be difficult to determine, but common causes are elevated levels of heparin-binding acute phase reactants, increased heparin clearance, and reduced AT activity. 73 Heparin resistance is a particular problem in neonates receiving ECMO because they have developmentally low levels of AT that can exacerbate heparin resistance 74 and they exhibit patterns of increased thrombin generation and fibrinolysis activation during anticoagulation with heparin that are distinct from children and adults. 75 Neonatal ECMO is also complicated by the immaturity of the hemostatic system, laboratory testing norms that are not tailored specifically for this population, inconsistency in management approaches, and limited availability of reliable evidence to establish optimal practices. 76

Heparin resistance during ECMO is usually managed with AT therapy, as raising AT levels increase the ability of heparin to achieve its anticoagulant effect. 77 Many institutions routinely use AT replacement in children undergoing ECMO to maximize the effect of heparin; others use AT reactively if difficulties are encountered in the titration of UFH. 78 Some cardiac surgeons use direct thrombin inhibitors such as bivalirudin if their institutional protocol dictates this approach. However, bivalirudin cost is substantially higher than that of heparin with AT therapy, and there is currently no reversal agent or antidote. 79

Meta-analyses have attempted to quantify the effects of AT therapy during ECMO by pooling and analyzing randomized controlled trials, but limitations in study design have restricted the usefulness of these studies in clinical practice. For example, in 2007, Afshari and colleagues 80 performed a meta-analysis of 20 randomized controlled trials with a total of 3458 patients, but their patient population was not adequately defined. Namely, all trials of patients who were “critically ill” were included, but the definition of critically ill allowed for variable severity and risk levels, from women with preeclampsia (∼0% mortality risk) to sepsis patients (∼50% mortality risk). This analysis also did not include trials of patients with myocardial infarction but did not provide justification for their exclusion. The decision to combine these particular datasets—and other methodological issues such as variations in patient age, dosing, treatment duration, and unbalanced distribution of groups—makes the quality of evidence from this study low.

A recent review of clinical practice indicates a general consensus that AT therapy is beneficial in achieving anticoagulation targets during ECMO. 81 The most recent study of AT therapy during ECMO showed that AT levels were sub-optimal in 88% of patients and that replacement for pediatric and neonatal patients with AT levels ≤80% did not increase risk of bleeding. 82 Guidelines from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization do not provide specific recommendations on the use of AT therapy during ECMO, 77 and prospective, randomized trials are needed to support evidence-based practice. In 2017, such a trial was begun in Italy to detect if AT therapy could decrease heparin dose requirements and improve anticoagulation during ECMO. Primary outcome results have not yet been published, but a pre-specified ancillary study showed a correlation between AT therapy and a decrease in inflammatory cytokines. 83

Overall, prevention of thrombosis must be balanced with efforts to minimize risks of bleeding, which can be particularly high in neonatal and pediatric patients. In both pediatric and adult patients undergoing ECMO or similar mechanical circulatory support such as a ventricular assist device, it can be a challenge to achieve appropriate titration of anticoagulation to prevent hemorrhagic and/or thrombotic complications, especially as substantial variability exists in the approach to management of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. 84 Individualized titration of anticoagulation intensity and improvements in the design and manufacture of devices are expected to enhance outcomes.

Further studies are needed to understand the optimal use of ATc during ECMO, particularly with respect to the difference in response to AT therapy in individuals with AT deficiency versus those with normal AT levels. These considerations are even more complex in infants and neonates due to their naturally low levels of AT as well as the dearth of studies available to inform evidence-based treatment guidelines.

Treatment and Prevention of SOS/VOD

Hepatic SOS, also known as VOD, is a serious complication that can develop after chemotherapy in the context of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. 85 The endothelial lining becomes damaged by chemotherapy, reducing AT and leading to a procoagulant state. The mechanism by which chemotherapeutic agents induce endothelial dysfunction is not well understood but is known to involve disruption of receptor proteins, 86 impairment of vasodilation, 87 and patchy exposure of the subendothelium. 88 Early studies concerning the prevention of SOS/VOD by prophylactic use of AT therapy showed reductions in healthcare utilization and morbidity, but the effectiveness of AT therapy in preventing SOS/VOD was not clear.89,90 A 2020 global SOS/VOD Task Force commissioned by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) cited these early studies in their report, which did not recommend AT therapy for the prevention of SOS/VOD in adults. 91 However, studies completed since 2008 have shown encouraging results on AT therapy in patients with SOS/VOD, especially when AT therapy is used to correct an AT deficiency rather than as prevention of SOS/VOD.11,92,93 Retrospective studies have observed sustained clinical response to AT therapy and no significant treatment-related morbidities, with decreased 100-day mortality rates in adults 94 and a 92% complete response rate in children. 11 A phase II open-label single-group clinical trial is ongoing in Korea, with early results showing that 68% of patients with SOS/VOD who reached target AT levels achieved complete response, though the sample size was small (N = 19). 92

Pregnancy-Related VTE

In the general population, pregnant women have a 5-fold higher risk of VTE than non-pregnant women, 52 and women with AT deficiency are at even higher risk, up to 50%.28,51 Elevated VTE risk carries into the postpartum period and is particularly high in the 6 weeks after delivery. 51 The mechanism behind pregnancy-related VTE in women with AT deficiency is thought to include increases in vascular volume, coagulation factor stimulation, state of hypercoagulability, compression of the veins, and changes in hepatic clearance.43,51 In normal pregnancy, AT levels fall precipitously at delivery and immediately postpartum, to 30% below baseline. 95 Since there is no evidence that synthesis of AT is impaired at this time, there is likely increased consumption of AT due to the hypercoagulable state of delivery. While this decrease in AT levels could potentially hold significant clinical implications for anticoagulation strategies in individuals at risk of pregnancy-related thrombosis, it may prove especially pertinent in the management of patients with a primary/secondary AT deficiency or an AT-deficient condition such as severe preeclampsia. Prevention and treatment of peripartum thromboembolism in women with AT deficiency are approved indications of ATc 8 ; clinical recommendations also support the use of ATc to prevent and manage VTE throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period.51,52 Current guidelines vary on the assessment of VTE risk and the optimum clinical management for pregnant women with AT deficiency, as no data from large-scale randomized controlled trials exist. 51 Cohort studies provide evidence of ATc's benefit in women with AT deficiency, specifically in treating VTE during pregnancy, preventing initial or recurrent VTE during pregnancy and delivery when administered with heparin, and as treatment in the case of complications and at delivery.52,96 Given that only small-scale studies are available, there is no standardized approach in the literature for management of pregnant women with AT deficiency, but VTE risk assessment is recommended before and during early pregnancy to individualize a treatment plan that includes AT therapy as warranted.51,96

Heparin Resistance During Cardiopulmonary Bypass

Anticoagulation is required during CPB to avoid clotting in the CPB circuit and to counteract thrombogenic factors stimulated by the surgical process. The most commonly used anticoagulant is UFH, which is dependent on AT for its therapeutic effect. 1 Between 4% and 26% of patients undergoing CPB demonstrate heparin resistance,97,98 meaning they fail to achieve an ACT of at least 400 to 480 s after receiving a standard heparin dose. 98 Heparin resistance can lead to thrombus formation and other serious surgical complications. The cause of heparin resistance is multifactorial and patient-specific but is usually attributable to an insufficient interaction between heparin and other blood elements, including AT.

Current clinical practice involves supplementation of heparin with AT once the heparin ceiling dose is reached; however, the threshold heparin dose is variable between institutions and practitioners, as is the timing and dose of AT. 97 Heparin resistance can also be treated by combined administration of heparin with FFP, but ATc is regarded as the safer choice over FFP. 99 Despite the higher costs and risk of heparin rebound for AT compared to FFP, AT has lower risk of transfusion-related lung injury and infections and lower volume administration, and patients are less likely to require additional transfusions during their hospital stay.10,99 The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) 2021 Clinical Practice Guidelines provide a Class 1A recommendation for the use of ATc to reduce FFP transfusions in patients with AT-mediated heparin resistance immediately before CPB and a Class 2B recommendation for its use in high-risk patients with religious objections to blood products. 100 Overall, the recommendation for heparin resistance during CPB is in favor of AT therapy, presuming ATc is available.

CRRT in Patients Who Are Critically Ill

CRRT is an alternative to intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) for patients who are critically ill and require renal support. The 2019 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline for acute kidney injury recommends CRRT for patients who are hemodynamically unstable, as CRRT is administered continuously over 24 h and therefore causes less drastic changes in fluids and solutes than IHD or PD. 101 Clotting of the extracorporeal circuit is a challenge in CRRT that is usually managed with heparin anticoagulation, but heparin administration consumes a significant amount of AT and can lead to premature clotting of the extracorporeal circuit filter. 102 Premature filter clotting reduces treatment efficacy and increases patient blood loss, in addition to driving higher staff workloads and costs as a consequence of reduced circuit life. 103

Retrospective studies indicate that AT therapy in patients with hereditary or acquired AT deficiency (AT levels <70%) may significantly increase filter lifetime, 104 help prevent clotting, and reduce heparin dose requirements. 105 Guidelines are limited due to lack of evidence, but consensus reports indicate that anticoagulation for CRRT should be individualized based on patient medical history, clinical presentation, and disease progression.106,107 Careful monitoring of AT levels can provide insight regarding the potential usefulness of AT therapy for critically ill patients undergoing CRRT.

Pediatric Postoperative Chylothorax

Chylothorax is a rare but serious condition in which chyle leaks from the lymphatic system into the pleural space as a result of damage to the thoracic duct. 108 Up to 3.9% of children undergoing any cardiac surgery and as many as 24% of children undergoing total cavopulmonary connection experience postoperative chylothorax,109,110 which is associated with significantly increased risks of mortality, ECMO use, and thrombosis. 111 Increased thrombotic risk may be due to decreases in AT, as children after cardiac surgery have 25% lower AT levels compared to age-matched children with non-chylous pleural effusion and ∼55% lower levels compared to healthy children. 112 Therefore, AT testing and replacement has been recommended for children with AT ≤60% in the immediate postoperative period (0-89 days) and for children with AT ≤80% after 89 days. 109

ALL Treated with l-Asparaginase

ALL is a cancer of the blood that occurs mostly in children, comprising ∼25% of cancers in patients younger than 15 years of age. 113 With access to modern treatment, ALL is curable and has 5-year survival rates of 93.5%. 114 Since the 1960s, l-asparaginase has been a mainstay of ALL treatment that has been credited with the progressive improvements in survival of children with ALL. 115 However, the use of l-asparaginase carries a risk of thrombosis, with VTE occurring in ∼5% of children 116 and 34% of adults 117 with ALL treated with l-asparaginase.

Depletion of AT levels during l-asparaginase therapy has long been observed 118 and is likely driven by decreased secretion of the AT protein by liver cells. 119 An early small-scale randomized trial reported in 1994 that AT therapy during l-asparaginase therapy elevated AT levels and provided protection from coagulopathy and DIC. 120 More recently, a 2020 meta-analysis of 8 retrospective studies on AT in patients with ALL found that the risk of VTE was significantly lower in adults with AT therapy versus those without. 13 Guidelines from the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis recommend AT therapy for adults with ALL receiving l-asparaginase treatment at a threshold AT level of 50% to 60%, targeting AT concentration in the normal range (80%-120%). 121

Sepsis and Sepsis-Associated DIC

According to a 2016 international task force, sepsis is defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by dysregulated host response to infection. 122 Septic shock is a subset of sepsis that is associated with a greater mortality risk than sepsis alone and is characterized by serious circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities. The inflammation that occurs in sepsis and septic shock can cause activation of the coagulation cascade, leading to sepsis-associated DIC (sepsis-DIC).123,124 In the United States, the incidence of severe sepsis is increasing at an annual rate of ∼13%, and 6-year mortality rates associated with sepsis and sepsis-DIC are estimated at 25% to 35%. 125

AT activity decreases at the onset of sepsis, and many studies have observed a significant correlation between AT levels and survival.126–128 However, attempts to improve clinical outcomes via AT therapy have largely been unsuccessful, with no significant mortality benefits observed for patients with sepsis in randomized controlled trials, though the interpretation of results from these trials is limited by the complexity of the trial design.129,130 Of note, a post hoc analysis showed a significant mortality reduction in patients with sepsis-DIC treated with AT therapy, 131 as did a meta-analysis of 32 randomized controlled trials. 132 In a 2013 randomized clinical trial of patients with sepsis-DIC in Japan, recovery rate was increased, sepsis-DIC scores were improved, and no major bleeding was observed with AT therapy. 133 Other Japanese retrospective studies have observed similar benefits associated with AT therapy in patients with sepsis-DIC.129,134,135 These results may be explained by the unique prognostic ability of baseline AT activity in predicting outcomes of patients with sepsis-DIC, and it may play an important role in early pathogenesis.127–129 Some clinicians have posited that AT therapy is most likely to be beneficial if administered as an early intervention against sepsis and sepsis-DIC, though this must be balanced with managing the potential risk of bleeding complications.123,124,136

Given these results, recommendations for the use of AT therapy in sepsis and sepsis-DIC vary widely. 124 In 2017, the International Surviving Sepsis Guideline panel recommended against the use of AT therapy for the treatment of sepsis and septic shock based on limited evidence and risk of bleeding, though they noted that future clinical trials may show benefits to patients with sepsis-DIC. 137 The Italian Society of Transfusion Medicine and Immunohaematology recommended in 2009 that treatment with AT therapy may be useful in sepsis-DIC to improve survival, though additional evidence is needed to make a strong recommendation. 50 The Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2020 provide the strongest support of AT therapy, with a grade 2C recommendation for AT therapy in patients with sepsis-DIC, finding that the mortality reduction benefit is likely to outweigh potential harms from risk of hemorrhagic complication. 138 An observational study to determine associations between early coagulopathy molecules and sepsis prognosis was registered with clinicaltrials.gov in 2020 (NCT04582188), but results have not been posted. 139 Further studies are needed to develop global evidence-based guidance related to the use of AT therapy in sepsis and sepsis-DIC.

COVID-19

COVID-19 is frequently associated with coagulopathy and high thrombotic risk, leading to thromboprophylaxis recommendations for hospitalized patients with COVID-19. 140 Heparin resistance has been documented in up to 80% of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit, which may be explained by observed reductions in AT levels. 141 In addition, multiple studies have identified AT levels as a prognostic marker of survival in severe COVID-19.16,141,142 In 2022, early results from a prospective randomized trial of AT therapy in participants with COVID-19 (N = 52) indicated that AT therapy was safe, with no breakthrough bleeding or other drug-related adverse events. 143

Recent molecular work indicates that the protective effect of AT against SARS-CoV-2 may occur at a very early stage of infection, as AT appears to inhibit the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect and replicate in lung epithelial cells. 144 Therefore, the effect of AT on COVID-19 pathophysiology may include anticoagulation, thromboprophylaxis, and protection against infection, but there are no current guidelines related to this application. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to determine if AT can improve outcomes for individuals with COVID-19.

Cost-Effectiveness

Current Costs

The cost of AT therapy has been described as a barrier to its use, 145 but the patient benefits associated with AT therapy can offset upfront costs.99,145–147 The acquisition cost of ATc varies between and within institutions and according to other location- and time-sensitive economic factors. 146 A 2018 cost-effectiveness study from the Johns Hopkins Hospital estimated the acquisition cost of a 500U vial of ATc (Thrombate III) to be US$2330 or $4.66 per unit. 146 A 2013 study from Florida estimated a slightly lower per-unit ATc acquisition cost of $3.27 ($3.53 adjusted for 2018 inflation). 148

In certain clinical contexts, the relative cost of ATc versus FFP may also be relevant, as providers may be able to choose between the 2 as options to achieve similar patient anticoagulation targets.16,49,99 Estimates for the mean acquisition cost per unit of FFP in the United States vary from $41.95 149 to $60.70, 150 and the price continues to increase annually, with regional variations. In-hospital processes such as the administration and monitoring of transfusions may cost as much as $170 per unit of FFP. 149 The delay associated with FFP defrosting time may also be a consideration in certain critical situations such as cardiac surgery, compared to the immediate availability of ATc. 10 Overall, in light of time spent during preparation and expenses associated with FFP administration such as overhead, transportation, and adverse events, ATc has been posited to be the overall more cost-effective and timely option versus FFP. 99

Cost-Effectiveness Strategies

Several cost-effectiveness strategies have been identified for ATc use, including rounding to full-vial sizes, weight-based dosing with restriction criteria, capped dosing protocols, and reductions in use of other blood products.14,145–147,151 One institution that rounded doses to a full-vial size if within 10% of the originally prescribed dose saw a median cost savings of US$1692 per dose and reduced waste of a median of 363 units per dose. 14 Other centers have adopted a similar full-vial use strategy to minimize wasted ATc, which resulted in savings from avoiding unused ATc product and reductions in the needed dose of other blood products. 151

A number of analyses have demonstrated that establishing internal institutional guidelines on ATc use cases, dosing strategies, and AT-level monitoring can increase cost-effectiveness.145–147 For example, a pilot study at Cincinnati Children's Hospital showed that a capped dosing protocol combined with peak AT monitoring achieved adequate AT repletion with an estimated total savings of $806,632 across 11 patients over an 18-month study period. 145 Similarly, the Johns Hopkins Hospital devised a set of restriction criteria and weight-based dosing protocols for AT repletion that resulted in projected estimated cost savings of US$556,000 per year. 146 Clinicians at Vanderbilt University implemented an anticoagulation laboratory protocol that included tests for antifactor Xa and AT levels. 147 The protocol led to significantly increased survival for pediatric patients receiving ECMO, as well as per year total blood product cost savings of more than $300,000. These recent studies suggest that despite the cost burden of additional laboratory measurements and close monitoring of AT activity, the implementation of institutional protocols can preserve good patient outcomes while leading to substantial cost savings and waste reduction.

Future Outlook

The role of AT in the coagulation system is critical, and its dysregulation or loss of function has far-reaching effects on patient health. The anticoagulant activity of heparin is overwhelmingly dependent on the presence and activity of AT. Available ATc products allow for optimization of AT levels to achieve hemostasis across transient and long-term clinical contexts. Adequate treatment with ATc is particularly important in patients with hereditary AT deficiency, as it is the most severe of the thrombophilias and carries a lifetime thrombotic risk of up to 85%. 28 Hereditary AT deficiency is underdiagnosed, as detection of all the subtypes is not possible with most commercial assays. 152 Advancement in early testing methods, expansion of access to genetically based personalized medicine, knowledge of evidence-based practice recommendations, understanding of AT therapy use cases, and increased provider awareness are important opportunities for improvement in the care of individuals with hereditary AT deficiency.

Acquired AT deficiency, which is typically transient in cause, must also be managed carefully in order to achieve the delicate balance of coagulation required in high-stress clinical situations. Understanding of the interplay between heparin and AT is critical, particularly as heparin resistance is relatively common in ECMO, cardiac surgery, CRRT, and COVID-19 and can usually be effectively managed with AT therapy. Research work in trauma-related VTE suggests that there may also be a benefit to AT therapy in critically injured patients, as it can increase the effectiveness of enoxaparin thromboprophylaxis153,154 and is important in the restoration of endothelial protective function in patients with hemorrhagic shock. 17 There may also be a potential role for AT in the modulation of tumor cell functions, particularly in its prelatent form, which is an intermediate conformation that occurs midway in the conversion of native to latent AT. 155 An in vitro study recently showed that prelatent AT decreased tumorigenic protein expression and activated resistance pathways in glioblastoma multiforme cells. 18 Another study showed that AT can inhibit metastatic proteases and angiogenesis in colorectal and lung cancer cell lines. 156

Clinical understanding of AT is limited by the quality and quantity of available evidence related to its effects on patient outcomes, including adverse events, in various clinical contexts. There are very few clinical trials on AT, and those which exist are small in size, poorly described, and at risk of bias due to lack of blinding, allocation concealment, and randomization, as well as incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. 157 Meta-analyses of pooled trials exist, but they have low quality of evidence due to high probability of bias and heterogeneity in the patient populations of the pooled trials, which are variable in participants, severity of condition, treatment regimens, and clinical setting.13,15,47,48,80,157 Patients and providers would benefit from a large-scale randomized controlled trial with low bias risk that would provide a high level of evidence concerning the effectiveness of AT use and supplementation.

The existing evidence surrounding the use of AT therapy, including its use in additional patient populations where AT therapy has been considered, suggests that there is much more to be discovered regarding the mechanisms and potential pathophysiological benefits of AT therapy. Cost-effectiveness analyses indicate that intentionality and pre-specified protocols for AT monitoring, dosing, and administration can maximize savings. Continued provider education on the role of AT in pathophysiology, hemostasis, and the broad variety of clinical contexts in which it can be used is critical to empowering the best clinical decision-making for optimal patient outcomes and strategic healthcare resource utilization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emily Farrar, PhD, of Boston Strategic Partners for medical writing support, funded by Grifols, Inc.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Both authors made substantial contributions to conceiving and drafting the article, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

The authors disclose support for the present manuscript in the form of medical writing and article processing charges, funded by Grifols, Inc. Dr Rodgers discloses membership on a jury panel sponsored by Grifols, Inc., that reviews research grant proposals on antithrombin research.

Funding: Medical writing support for this study was funded by Grifols, Inc.

ORCID iD: George M. Rodgers https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1234-0128

References

- 1.Oliver WC, Nuttall GA. Uncommon Cardiac Diseases. In: Kaplan JA, ed. Essentials of Cardiac Anesthesia. W.B. Saunders; 2008:415-444. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashikaga H, Chien KR. Blood Coagulation and Atherothrombosis. In: Chien KR, ed. Molecular Basis of Cardiovascular Disease. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; 2004:498-518. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conard J, Brosstad F, Lie Larsen M, Samama M, Abildgaard U. Molar antithrombin concentration in normal human plasma. Haemostasis. 1983;13(6):363-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson TH, Simon TL, Atencio AC. In vivo behavior of human radioiodinated antithrombin III: distribution among three physiologic pools. Blood. 1985;66(1):13-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson ST, Richard B, Izaguirre G, Schedin-Weiss S, Gettins PG. Molecular mechanisms of antithrombin-heparin regulation of blood clotting proteinases. A paradigm for understanding proteinase regulation by serpin family protein proteinase inhibitors. Biochimie. 2010;92(11):1587-1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy JH, Sniecinski RM, Welsby IJ, Levi M. Antithrombin: anti-inflammatory properties and clinical applications. Thromb Haemostasis. 2016;115(04):712-728. doi: 10.1160/TH15-08-0687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thaler E, Lechner K. Antithrombin III deficiency and thromboembolism. Clin Haematol. 1981;10(2):369-390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thrombate III, prescribing information [Internet]. Grifols/Talecris. 1991. Accessed June 2, 2023. https://www.thrombate.com/en/home.

- 9.Atryn, prescribing information [Internet]. Ovation Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2009. Accessed June 2, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/75529/download.

- 10.Beattie GW, Jeffrey RR. Is there evidence that fresh frozen plasma is superior to antithrombin administration to treat heparin resistance in cardiac surgery? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(1):117-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M, Rao S, Eickhoff JC, DeSantes KB, Capitini CM. A retrospective analysis of antithrombin III replacement therapy for the treatment of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome in children following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;42(2):145-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar G, Maskey A. Anticoagulation in ECMO patients: an overview. Ind J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;37(Suppl 2):241-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosalem O, Mujer M, Abu Rous F, Cole CE. Antithrombin supplementation in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) following asparaginase therapy: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stockton WM, Padilla-Tolentino E, Ragsdale CE. Antithrombin III doses rounded to available vial sizes in critically ill pediatric patients. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22(1):15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Umemura Y, Yamakawa K, Ogura H, Yuhara H, Fujimi S. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in three specific populations with sepsis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2016;14(3):518-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anaklı İ, Ergin Özcan P, Polat Ö, et al. Prognostic value of antithrombin levels in COVID-19 patients and impact of fresh frozen plasma treatment: a retrospective study. Turk J Haematol. 2021;38(1):15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez E, Peng Z, Kozar RA, et al. Antithrombin III contributes to the protective effects of fresh frozen plasma following hemorrhagic shock by preventing syndecan-1 shedding and endothelial barrier disruption. Shock. 2020;53(2):156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peñas-Martínez J, Luengo-Gil G, Espín S, et al. Anti-tumor functions of prelatent antithrombin on glioblastoma multiforme cells. Biomedicines. 2021;9(5):523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrow RT, Healey JF, Lollar P. Inhibition by heparin of thrombin-catalyzed activation of the factor VIII-von Willebrand factor complex. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(1):593-598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezaie AR. Rapid activation of protein C by factor Xa and thrombin in the presence of polyanionic compounds. Blood. 1998;91(12):4572-4580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodgers GM. Role of antithrombin concentrate in treatment of hereditary antithrombin deficiency. Thromb Haemostasis. 2009;101(05):806-812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Donnell JS, O'Sullivan JM, Preston RJS. Advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms that maintain normal haemostasis. Br J Haematol. 2019;186(1):24-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor FB, Jr., Emerson TE, Jr., Jordan R, Chang AK, Blick KE. Antithrombin-III prevents the lethal effects of Escherichia coli infusion in baboons. Circ Shock. 1988;26(3):227-235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann JN, Vollmar B, Inthorn D, Schildberg FW, Menger MD. Antithrombin reduces leukocyte adhesion during chronic endotoxemia by modulation of the cyclooxygenase pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279(1):C98-C107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlömmer C, Brandtner A, Bachler M. Antithrombin and its role in host defense and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):4283. 10.3390/ijms22084283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egeberg O. Thrombophilia caused by inheritable deficiency of blood antithrombin. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1965;17(1):92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tait RC, Walker ID, Perry DJ, et al. Prevalence of antithrombin deficiency in the healthy population. Br J Haematol. 1994;87(1):106-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maclean PS, Tait RC. Hereditary and acquired antithrombin deficiency: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment options. Drugs. 2007;67(10):1429-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng W, Tang L, Jian XR, et al. Genetic analysis should be included in clinical practice when screening for antithrombin deficiency. Thromb Haemostasis. 2015;113(2):262-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luxembourg B, Pavlova A, Geisen C, et al. Impact of the type of SERPINC1 mutation and subtype of antithrombin deficiency on the thrombotic phenotype in hereditary antithrombin deficiency. Thromb Haemostasis. 2014;111(2):249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vrtel P, Slavik L, Vodicka R, et al. Detection of unknown and rare pathogenic variants in antithrombin, protein C and protein S deficiency using high-throughput targeted sequencing. Diagnostics. 2022;12(5):1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lijfering WM, Brouwer JL, Veeger NJ, et al. Selective testing for thrombophilia in patients with first venous thrombosis: results from a retrospective family cohort study on absolute thrombotic risk for currently known thrombophilic defects in 2479 relatives. Blood. 2009;113(21):5314-5322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swoboda V, Zervan K, Thom K, et al. Homozygous antithrombin deficiency type II causing neonatal thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2017;158:134-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinelli I, Mannucci PM, De Stefano V, et al. Different risks of thrombosis in four coagulation defects associated with inherited thrombophilia: a study of 150 families. Blood. 1998;92(7):2353-2358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abou-Ismail MY, Citla Sridhar D, Nayak L. Estrogen and thrombosis: a bench to bedside review. Thromb Res. 2020;192:40-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lane DA, Bayston T, Olds RJ, et al. Antithrombin mutation database: 2nd (1997) update. For the Plasma Coagulation Inhibitors Subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Thromb Haemostasis. 1997;77(1):197-211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gindele R, Pénzes-Daku K, Balogh G, et al. Investigation of the differences in antithrombin to heparin binding among antithrombin Budapest 3, Basel, and Padua mutations by biochemical and in silico methods. Biomolecules. 2021;11(4):544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S, Lee W-J, Moon J, Jung K-H. Utility of the SERPINC1 gene test in ischemic stroke patients with antithrombin deficiency. Front Neurol. 2022;13:841934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu S, Wang H, Xu Q, et al. Type II antithrombin deficiency caused by a novel missense mutation (p.Leu417Gln) in a Chinese family. Blood Coagul Fibrin. 2021;32(1):57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F, Gui Y, Lu Y, et al. Novel SERPINC1 missense mutation (Cys462Tyr) causes disruption of the 279Cys-462Cys disulfide bond and leads to type I hereditary antithrombin deficiency. Clin Biochem. 2020;85:38-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang HL, Ruan DD, Wu M, et al. Identification and characterization of two SERPINC1 mutations causing congenital antithrombin deficiency. Thromb J. 2023;21(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bravo-Pérez C, de la Morena-Barrio ME, de la Morena-Barrio B, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of transient antithrombin deficiency: a new concept in congenital thrombophilia. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(2):216-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeJongh J, Frieling J, Lowry S, Drenth HJ. Pharmacokinetics of recombinant human antithrombin in delivery and surgery patients with hereditary antithrombin deficiency. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20(4):355-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de la Morena-Barrio B, Orlando C, de la Morena-Barrio ME, et al. Incidence and features of thrombosis in children with inherited antithrombin deficiency. Haematologica. 2019;104(12):2512-2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flanders MM, Phansalkar AR, Crist RA, Roberts WL, Rodgers GM. Pediatric reference intervals for uncommon bleeding and thrombotic disorders. J Pediatr. 2006;149(2):275-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muszbek L, Bereczky Z, Kovács B, Komáromi I. Antithrombin deficiency and its laboratory diagnosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2010;48(Suppl 1):S67-S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Croles FN, Borjas-Howard J, Nasserinejad K, Leebeek FW, Meijer K. Risk of venous thrombosis in antithrombin deficiency: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. In: Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 2018:315-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Croles FN, Nasserinejad K, Duvekot JJ, et al. Pregnancy, thrombophilia, and the risk of a first venous thrombosis: systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis. Br Med J. 2017;359(8127):j4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair PM, Rendo MJ, Reddoch-Cardenas KM, et al. Recent advances in use of fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, immunoglobulins, and clotting factors for transfusion support in patients with hematologic disease. Semin Hematol. 2020;57(2):73-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liumbruno G, Bennardello F, Lattanzio A, Piccoli P, Rossetti G. Italian Society of Transfusion Medicine and Immunohaematology (SIMTI) Working Party. Recommendations for the use of antithrombin concentrates and prothrombin complex concentrates. Blood Transfus. 2009;7(4):325-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hart C, Rott H, Heimerl S, Linnemann B. Management of antithrombin deficiency in pregnancy. Hamostaseologie. 2022;42(5):320-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.James AH, Konkle BA, Bauer KA. Prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy in patients with hereditary antithrombin deficiency. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:233-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer KA, Nguyen-Cao TM, Spears JB. Issues in the diagnosis and management of hereditary antithrombin deficiency. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50(9):758-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright JN, Vazquez SR, Kim K, Jones AE, Witt DM. Assessing patient preferences for switching from warfarin to direct oral anticoagulants. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019;48(4):596-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuk J, Papuga-Szela E, Zareba L, Undas A. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with severe inherited thrombophilia: a single-center cohort study. Int J Hematol. 2021;113(2):190-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.FDA approves drug to treat, help prevent types of blood clots in certain pediatric populations [Internet]. US Food & Drug Administration. 2021. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-drug-treat-help-prevent-types-blood-clots-certain-pediatric-populations.

- 57.Corrales-Medina FF, Raffini L, Recht M, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in pediatric venous thromboembolism: experience in specialized pediatric hemostasis centers in the United States. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;7(1):100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.FDA approves first oral blood thinning medication for children [Internet]. US Food & Drug Administration. 2021. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-oral-blood-thinning-medication-children.

- 59.Campello E, Spiezia L, Simion C, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with inherited thrombophilia and venous thromboembolism: a prospective cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(23):e018917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elsebaie MA, van Es N, Langston A, Büller HR, Gaddh M. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with venous thromboembolism and thrombophilia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2019;17(4):645-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Siriez R, Dogné JM, Gosselin R, et al. Comprehensive review of the impact of direct oral anticoagulants on thrombophilia diagnostic tests: practical recommendations for the laboratory. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021;43(1):7-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vercruyssen J, Meeus P, Bailleul E. Resolving DOAC interference on antithrombin activity testing on a FXa based method by the use of activated carbon. Clin Chim Acta. 2023;538:216-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ząbczyk M, Natorska J, Kopytek M, Malinowski KP, Undas A. The effect of direct oral anticoagulants on antithrombin activity testing is abolished by DOAC-stop in venous thromboembolism patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145(1):99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Darlow J, Mould H. Thrombophilia testing in the era of direct oral anticoagulants. Clin Med. 2021;21(5):e487-e491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mahmoodi BK, Brouwer JL, Ten Kate MK, et al. A prospective cohort study on the absolute risks of venous thromboembolism and predictive value of screening asymptomatic relatives of patients with hereditary deficiencies of protein S, protein C or antithrombin. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2010;8(6):1193-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Vlijmen EF, Wiewel-Verschueren S, Monster TB, Meijer K. Combined oral contraceptives, thrombophilia and the risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2016;14(7):1393-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Van Cott EM, Orlando C, Moore GW, et al. Recommendations for clinical laboratory testing for antithrombin deficiency; communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2020;18(1):17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Von Kaulla E, Von Kaulla KN. Antithrombin 3 and diseases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1967;48(1):69-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.FDA. Use of approved drugs for unlabeled indications. In: FDA Drug Bull. 1982: 4-5. [PubMed]

- 70.Nightingale SL. Off-label use of prescription drugs. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(3):425-427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barton R, Ignjatovic V, Monagle P. Anticoagulation during ECMO in neonatal and paediatric patients. Thromb Res. 2019;173:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bembea MM, Annich G, Rycus P, et al. Variability in anticoagulation management of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: an international survey. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(2):e77-e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Raghunathan V, Liu P, Kohs TCL, et al. Heparin resistance is common in patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation but is not associated with worse clinical outcomes. ASAIO J. 2021;67(8):899-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Monagle P, Chan AKC, Goldenberg NA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e737S-e801S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Hundalani SG, Nguyen KT, Soundar E, et al. Age-based difference in activation markers of coagulation and fibrinolysis in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(5):e198-e205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cashen K, Meert K, Dalton H. Anticoagulation in neonatal ECMO: an enigma despite a lot of effort!. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McMichael ABV, Ryerson LM, Ratano D, et al. 2021 ELSO adult and pediatric anticoagulation guidelines. ASAIO J. 2022;68(3):303-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beyer JT, Schoeppler KE, Zanotti G, et al. Antithrombin administration during intravenous heparin anticoagulation in the intensive care unit: a single-center matched retrospective cohort study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(1):145-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buck ML. Bivalirudin as an alternative to heparin for anticoagulation in infants and children. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20(6):408-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Afshari A, Wetterslev J, Brok J, Møller A. Antithrombin III in critically ill patients: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Br Med J. 2007;335(7632):1248-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piacente C, Martucci G, Miceli V, et al. A narrative review of antithrombin use during veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: rationale, current use, effects on anticoagulation, and outcomes. Perfusion. 2020;35(6):452-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tzanetos DRT, Myers J, Wells T, et al. The use of recombinant antithrombin III in pediatric and neonatal ECMO patients. ASAIO J. 2017;63(1):93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Panigada M, Spinelli E, De Falco S, et al. The relationship between antithrombin administration and inflammation during veno-venous ECMO. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):14284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raffini L. Anticoagulation with VADs and ECMO: walking the tightrope. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017(1):674-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bonifazi F, Barbato F, Ravaioli F, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of VOD/SOS after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Woodley-Cook J, Shin LY, Swystun L, et al. Effects of the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin on the protein C anticoagulant pathway. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(12):3303-3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chow AY, Chin C, Dahl G, Rosenthal DN. Anthracyclines cause endothelial injury in pediatric cancer patients: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):925-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cwikiel M, Zhang B, Eskilsson J, Wieslander J, Albertsson M. The influence of 5-fluorouracil on the endothelium in small arteries. An electron microscopic study in rabbits. Scanning Microsc. 1995;9(2):23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Haire WD, Ruby EI, Stephens LC, et al. A prospective randomized double-blind trial of antithrombin III concentrate in the treatment of multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1998;4(3):142-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Morris JD, Harris RE, Hashmi R, et al. Antithrombin-III for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced organ dysfunction following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20(10):871-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mohty M, Malard F, Abecasis M, et al. Prophylactic, preemptive, and curative treatment for sinusoidal obstruction syndrome/veno-occlusive disease in adult patients: a position statement from an international expert group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(3):485-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hong CR, Lee JW, Eom H-S, et al. A multicenter prospective phase II study of antithrombin-III based treatment for veno-occlusive disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2016;128(22):3387. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Richardson P, Aggarwal S, Topaloglu O, Villa KF, Corbacioglu S. Systematic review of defibrotide studies in the treatment of veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54(12):1951-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peres E, Kintzel P, Dansey R, et al. Early intervention with antithrombin III therapy to prevent progression of hepatic venoocclusive disease. Blood Coagul Fibrin. 2008;19(3):203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.James AH, Rhee E, Thames B, Philipp CS. Characterization of antithrombin levels in pregnancy. Thromb Res. 2014;134(3):648-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kobayashi T. Clinical guidance for pregnant women with hereditary thrombotic predisposition. Clinical Blood. 2022;63(9):1223-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sniecinski RM, Bennett-Guerrero E, Shore-Lesserson L. Anticoagulation management and heparin resistance during cardiopulmonary bypass: a survey of Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists members. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):e41-e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ, et al. 2011 Update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(3):944-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Spiess BD. Treating heparin resistance with antithrombin or fresh frozen plasma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(6):2153-2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tibi P, McClure RS, Huang J, et al. STS/SCA/AmSECT/SABM update to the clinical practice guidelines on patient blood management. J Extra-Corpor Technol. 2021;53(2):97-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179-c184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singer M, McNally T, Screaton G, et al. Heparin clearance during continuous veno-venous haemofiltration. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20(3):212-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Joannidis M, Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Clinical review: patency of the circuit in continuous renal replacement therapy. Crit Care. 2007;11(4):218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]