Abstract

We determined the nucleotide sequences of blaCARB-4 encoding CARB-4 and deduced a polypeptide of 288 amino acids. The gene was characterized as a variant of group 2c carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamases such as PSE-4, PSE-1, and CARB-3. The level of DNA homology between the bla genes for these β-lactamases varied from 98.7 to 99.9%, while that between these genes and blaCARB-4 encoding CARB-4 was 86.3%. The blaCARB-4 gene was acquired from some other source because it has a G+C content of 39.1%, compared to a G+C content of 67% for typical Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes. DNA sequencing revealed that blaAER-1 shared 60.8% DNA identity with blaPSE-3 encoding PSE-3. The deduced AER-1 β-lactamase peptide was compared to class A, B, C, and D enzymes and had 57.6% identity with PSE-3, including an STHK tetrad at the active site. For CARB-4 and AER-1, conserved canonical amino acid boxes typical of class A β-lactamases were identified in a multiple alignment. Analysis of the DNA sequences flanking blaCARB-4 and blaAER-1 confirmed the importance of gene cassettes acquired via integrons in bla gene distribution.

Penicilloyl serine transferases, routinely called β-lactamases, cleave the cyclic amide bond of β-lactam antibiotics via the formation of a serine ester-linked penicilloyl enzyme giving a product devoid of antibacterial activity (46). A close inspection of databases indicated that in the last 3 years, a collection of at least 150 DNA sequences from plasmid-mediated and chromosomal bla genes has been acquired. Analysis of deduced peptides confirmed that most have conserved motifs typical of serine active-site enzymes that are divided into three major classes (classes A, C, and D) on the basis of a level of amino acid sequence identity of more than 20% between members in each class (10).

In 1969, a β-lactamase was found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Dalgleish, it was noticed to be “markedly active against carbenicillin,” and the enzyme was named PSE-4 (13, 32). As other β-lactamase enzymes were found, it was noticed that some β-lactamases have better activities than others against carbenicillin. All β-lactamases except class C enzymes hydrolyze carbenicillin at very different levels; class C enzymes hydrolyse it poorly. Genes encoding enzymes similar to PSE-4 were subsequently discovered in other bacterial species and are now known to be part of multidrug resistance transposons (24). In addition to the four original β-lactamases called PSE-1, PSE-2, PSE-3, and PSE-4, a plethora of plasmid-mediated enzymes capable of hydrolyzing carbenicillin at a high rate, such as LCR-1 (10), AER-1 (16), CARB-3 (22), NPS-1 (26), CARB-5 (35), and CARB-4 (36), were identified; but these enzymes have subtle differences in their biochemical properties and in their substrate profiles (7). The amino acid sequences of PSE-1 (17), PSE-2 (18), PSE-3 (8), PSE-4 (4), and CARB-3 (23) have been compared to those of other class A and class D enzymes, and it has been confirmed that PSE-2 (OXA-10) is a class D enzyme (10).

The relationship of CARB-4 to other plasmid-mediated β-lactamases has been tested by determining the neutralization of benzylpenicillin-hydrolyzing activity with antisera prepared against purified the TEM-1, OXA-4, and CARB-3 β-lactamases (36). Antisera prepared with CARB-3 antigen inactivated the CARB-4 β-lactamase as well as the PSE-1, PSE-4, and CARB-3 enzymes (22, 36). The blaCARB-3 and blaCARB-4 genes are localized within transposons Tn1413 (7 kb) and Tn1408 (25 kb), respectively; these mobile elements were from plasmids isolated from bacterial strains of distinct origins (24, 27, 47).

Unusual β-lactamases such as a metalloenzyme have been reported in Aeromonas hydrophila, a water-borne, gram-negative rod known to be highly resistant to β-lactam antibiotics, including carbenicillin (42). A carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase has been discovered in an isolate of A. hydrophila from blood (16). The substrate profile of the AER-1 enzyme resembled those of plasmid-mediated carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzymes, but it had a different isoelectric point (pI 5.9) and molecular mass (29 kDa); these values are reminiscent of those for BRO-1 (pI 5.45), PSE-1 (pI 5.7), CARB-3 (pI 5.75), and CARB-5 (pI 5.35). The gene coding for AER-1 is part of the Ω7711 unit which is IncP mobilizable but RecA dependent and which inserts only between purC and guaB at a specific site in the Escherichia coli chromosome (16). The Ω7711 unit cotransfers resistance to the antibiotics chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and sulfonamide; the transfer of multidrug resistance and insertion at a unique site are properties analogous to those of Tn7.

In the study described in this report, we have focused on a carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzyme identified from a clinical isolate, P. aeruginosa p83372, containing the pUD12 plasmid and producing CARB-4. This enzyme has an acidic isoelectric point (pI 4.3) and hydrolyzes carbenicillin very efficiently (36). We also present the nucleotide sequences of blaAER-1 and blaCARB-4, including flanking sequences containing integrons that explain their distribution and presence in different mobile genetic elements (15). We compared the deduced AER-1 and CARB-4 polypeptides with those of other group 2c enzymes (7) via a multiple alignment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown on tryptic soy agar plates (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml). The cloning vector used initially was pACYC184 (chloramphenicol resistant [Cmr] and tetracycline resistant [Tetr]) (9, 37). E. coli HB101 (5) transformants were selected on chloramphenicol-containing plates and were susceptible to tetracycline. E. coli HB101 was the recipient of pMON1028, pMON510, and recombinant plasmid derivatives coding for CARB-4 and AER-1 β-lactamases. The selected transformants were confirmed to produce the prototype enzymes by isoelectric focusing (23). For single-stranded DNA production and sequencing, the blaCARB-4 and blaAER-1 genes were subcloned into phages M13mp18 and M13mp19 (29). E. coli JM101 was used as a recipient and was kept on minimal medium without proline (44). Bacteriophages M13mp18 and M13mp19, the replicative forms of phagemids pBGS18+ and pBGS19+, and single-stranded DNA were prepared by standard procedures (29, 30, 39, 40, 43).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phagemids, and phages used in the study

| Strain, plasmid, or phagemid | Characteristics | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| HB101 | F−ara-14 galK2 hsds(20) lacY1 leu mtl-1 proA2 recA13 rpsL20 supE44 thi xyl-5 | 5 |

| JM101 | supE thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′ (traD36 proAB lacIqZ ΔM15) | 29, 30 |

| J53-2 | F-met pro Rifr | 6 |

| J3-2 Ω7711 | F−met pro Rifr Ω7711 Apr Cmr Smr Sur Tcr | 6 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila VL7711 | Isolated from a human blood sample, India; Apr Cmr Smr Sur Tcr | 6 |

| Plasmids and phagemids | ||

| pACYC184 | Cmr Tcr p15A derivative | 9, 37 |

| pMK20 | Kmr | 21 |

| pBGS19+ | Kmr | 44 |

| pBGS18+ | Kmr | 44 |

| pMON1025 | Apr Cmr Sur; a 4.3-kb BamHI fragment from pMK20, Tn1413 | 25 |

| pMON1035 | Apr Kmr; a 1.9-kb BamHI-HindIII fragment into pBGS18+ | This work |

| pMON1039 | Apr Kmr; a 1.1-kb BglII-XhoI fragment into M13mp18 | This work |

| pMON1041 | Apr Kmr; a 1.1-kb BglII-XhoI into M13mp19 | This work |

| pMON1042 | A 650-bp XbaI-XbaI into M13mp18 | This work |

| pMON1043 | A 650-bp XbaI-XbaI fragment into M13mp19 | This work |

| pMON1044 | A 480-bp HindIII fragment into M13mp18 | This work |

| pMON1045 | A 480-bp HindIII fragment into M13mp19 | This work |

| pMON510 | J53-2 Ω7711; 1.5-kb Sau3AI chromosomal DNA fragment | 25 |

| pMON511 | Apr; a 2.2-kb SalI-HindIII from pMON510 in pBGS18+ | This work |

| pMON512 | Apr; a 2.2-kb HindIII-SalI from pMON510 in pBGS19+ | This work |

Enzymes and chemicals.

All chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available. Restriction enzymes were used with the manufacturer’s recommendations and were from Pharmacia LKB, Baie d’Urfé, Montréal, Québec, Canada; New England Biolabs, Mississaugua, Ontario, Canada; and Gibco BRL, Mississaugua, Ontario, Canada. The radioisotope [35S]dATP was from Amersham.

Preparation of DNA and related techniques.

Large plasmid DNA preparations were prepared by the cleared lysate method, with modifications for cell lysis (1 mg of lysozyme per ml, 7.5 mM disodium EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [pH 8.0]), and were purified by cesium chloride-ethidium bromide gradient ultracentrifugation (14, 39). Plasmid minipreparations for double-stranded DNA sequencing were prepared with Qiagen plasmid mini and midi kits (Chatsworth, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s suggestions. Restriction enzymes were digested as recommended by the manufacturer; ligation, transformation, and selection of recombinant DNA molecules were done by standard procedures (39, 43).

Physical mapping and subcloning.

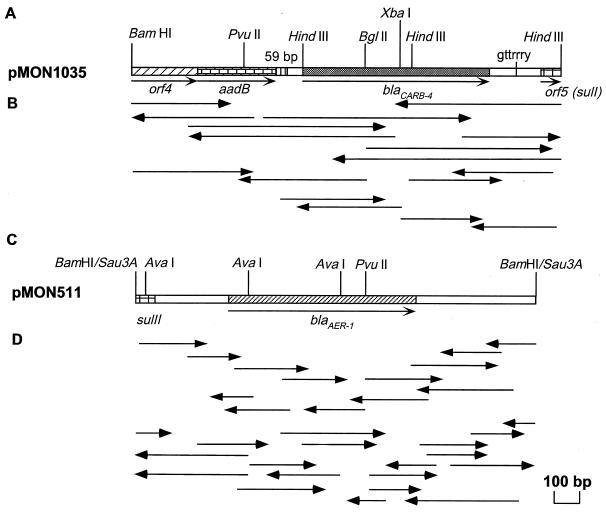

We previously reported the cloning of a 4.3-kb BamHI DNA fragment containing blaCARB-4 (CARB-4) and a 1.5-kb Sau3AI fragment coding for blaAER-1 (AER-1) isolated from the multidrug resistance transposon Tn1413 (Apr, Gmr, Kmr, Sur, Tmr) and from a genomic library of E. coli J53-1 Ω7711, respectively (25). E. coli HB101 transformants were selected for ampicillin resistance containing recombinant plasmids pMON1025 and pMON511 and were confirmed to produce CARB-4 (pI 4.3) and AER-1 (pI 5.9) β-lactamases by isoelectric focusing (data not shown). From pMON1025, we constructed plasmids pMON1026, pMON1027, pMON1028, and pMON1035 (Table 1). Phenotypic analysis of E. coli HB101 transformants with ampicillin, kanamycin, and sulfonamide and correlation with the plasmids’ physical DNA maps constructed with selected restriction endonucleases indiated that blaCARB-4 is within the 1.9-kb BamHI plus HindIII fragment. The physical map of pMON511 is shown in Fig. 1C. The blaAER-1 structural gene was centrally mapped by deletion of an AvaI fragment and was associated with ampicillin susceptibility in the recipient E. coli strain.

FIG. 1.

Physical maps of recombinant plasmids pMON1035 (A) and pMON511 (C). Only the DNA inserts are depicted as open-boxed lines that include the restriction sites used for subcloning into M13mp18 and M13mp19 sequencing vectors. The sequencing strategies used for blaCARB-4 and flanking DNA (B) and blaAER-1 (D) are indicated below each map. The extent and direction of each sequencing reaction are indicated by arrows, and sequencing primers, synthesized as 21-mers from the last nucleotides read, were used.

DNA sequencing.

The 650-bp XbaI-XbaI DNA fragment (in which the first XbaI is blaCARB-4 and the second site is in the pACYC184 moiety at position 1424 [37]), the 548-bp HindIII-HindIII fragment, and the 1.1-kb BglII-XhoI fragments isolated from pMON1025 and pMON1039 (Table 1) were cloned in both orientations into the sequencing phage vectors M13mp18 and M13mp19 and into the phagemids pBGS18+ and pBGS19+ (30, 44). For blaAER-1, a 2.2-kb HindIII-SalI fragment from pMON511 (Table 1) was cloned into M13mp8 and M13mp9 (29). The 2.2-kb SalI-HindIII fragment from pMON511 was subcloned into phagemid pBGS18+ for sequencing (Fig. 1C and Table 1). Complementary DNA strands were completely sequenced by the primer walking sequencing strategy outlined in Fig. 1B and D. Nucleotide sequencing of single-stranded DNA was done by the dideoxynucleotide T7 polymerase chain termination method (40) with the Pharmacia LKB sequencing kit and [α-35S]dCTP (Amersham).

Nucleotide sequencing was also repeated on an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer with ABI Prism dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kits by the AmpliTaq DNA polymerase protocol as recommended by the manufacturer (Perkin-Elmer, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Sequencing primers were usually 21-mers selected from the last 50 nucleotides read on autoradiograms or from chromatograms and were synthesized on a Gene Assembler Plus apparatus (Pharmacia) and an Beckman Oligo1000 DNA synthesizer. The oligonucleotides were purified on short 20% polyacrylamide–urea sequencing gels and visualized by UV shadowing (2).

Informatics and computer software analysis.

DNA sequence analyses were done with software from ABI (Factura, Gene Navigator, and AutoAssembler) and the Genetics Computer Group (version 9.0) of the University of Wisconsin (11). Comparisons of the sequences with the sequences in the GenBank, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, and National Biomedical Research Foundation databases were done with the Genetics Computer Group software package adapted to a UNIX-based system by using the FASTA, TFASTA, and BLAST programs. Identification of signal peptides and prediction of protein localization sites were done by two methods (31, 33, 34). Molecular masses and pI values were predicted from the amino acid sequences as described previously (3). The Terminator and Stemloop programs were used to identify terminator sequences by using a primary structure threshold cutoff P value of 3.5 (6). Multiple alignments were done with CLUSTALW in the MOLPHY (version 2.2) package of software. Phylogenies were obtained with the PHYLIP software package (version 3.57c), obtained from J. Felsenstein, University of Washington (12).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences reported here have been assigned GenBank accession nos. U14748 and U14749.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequence of blaCARB-4 encoding CARB-4.

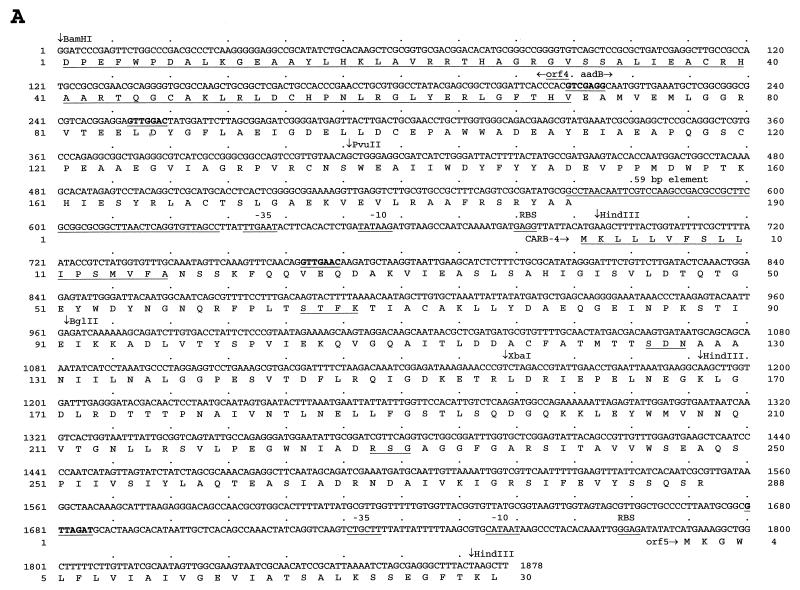

Comparisons of the physical maps of pMON1025 and Tn1413 published previously (24, 28) and the map of pMON1035 described in Fig. 1A showed minor differences in the positions of restriction endonuclease sites (as a BamHI site) that were attributed to the limits of DNA mapping done previously (24, 28). The nucleotide sequences of the physical DNA maps for BglII, ClaI, HindIII, PvuII, SstI, and XbaI done for pMON1035 shown in Fig. 1A were also identified (Fig. 2). We refer to the gene as blaCARB-4 encoding CARB-4, and complementary DNA strands were completely sequenced by using subclones and the primer walking sequencing strategy illustrated in Fig. 1B and D. The nucleotide sequence of blaCARB-4 (Fig. 2A) is 1,878 nucleotides (nts) long. Searches in databases identified an integron that comprised open reading frame (ORF) ORF4 (from nts 1 to 211) and that was in frame with part of aadB and a 59-bp element (from nts 212 to 271) (15, 41). We identified the blaCARB-4 gene cassette encoding CARB-4 (from nts 572 to 1679) and part of ORF5 encoding sul-1 (from nts 1680 to 1878). The blaCARB-4 gene cassette had significant DNA homology with blaPSE-1 (86.5%) and blaN-29 (86.3%), as summarized in Table 2. DNA analysis indicated G+C contents of 69.2% for ORF4 and 58.8% for aadB. Curiously, the blaCARB-4 gene cassette encoding CARB-4 had a G+C content of 39.1% and ORF5 had a G+C content of 38.7%. Similar G+C contents for part of the integron and blaCARB-4 would indicate a role of the integron in the assembly of the 1.87-kb locus. In addition, the typical G+C content of genes from P. aeruginosa is 67%.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequences of blaCARB-4 (A) and blaAER-1 (B) genes and their flanking regions. The deduced amino acid sequence is indicated by the one-letter code beginning under the first nucleotide of each codon. The secretion peptides in CARB-4 and AER-1 as well as conserved amino acids found in PRPs are underlined (1, 19, 20). The stop codon in each sequence is indicated by an asterisk. Ribosome-binding sites (RBS) and −10 and −35 regions are underlined, and potential int recombination sequences (gttrrry) are indicated in boldface in the DNA sequence. Horizontal arrows indicate the direction of transcription; vertical arrows identify the cutting sites of the restriction endonucleases.

TABLE 2.

DNA homology between β-lactamases of group 2c genes

| β-Lac- tamase | % Homology

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSE-4 | CARB-3 | CARB-4 | PSE-3 | AER-1 | PSE-1 | N-29 | GN79 | |

| CARB-3 | 99.78 | |||||||

| CARB-4 | 86.39 | 86.39 | ||||||

| PSE-3 | 50.46 | 50.73 | 49.54 | |||||

| AER-1 | 50.44 | 50.33 | 51.41 | 60.76 | ||||

| PSE-1 | 99.89 | 99.89 | 86.51 | 50.59 | 50.59 | |||

| N-29 | 98.73 | 98.73 | 86.28 | 50.46 | 50.59 | 98.85 | ||

| GN79 | 53.33 | 53.10 | 54.98 | 53.54 | 50.00 | 53.29 | 52.83 | |

| BRO-1 | 48.89 | 48.89 | 48.94 | 46.61 | 42.72 | 48.71 | 49.06 | 49.87 |

The blaCARB-4 coded for a CARB-4 peptide of 288 amino acids, it had a theoretical pI of 4.74, and it had a molecular weight of 31,489, including a predicted 17-amino-acid signal peptide; the mature protein has a pI of 4.67 and a molecular weight of 29,585; these values agree with the biochemical data (36). As shown in Table 3, CARB-4 had the highest degrees of identity with CARB-3 (86.8%) and PSE-4 (86.1%). CARB-4 has an STFK tetrad (amino acid positions 65 to 68, known as SXXK starting at S70 in Ambler’s standard numbering for class A) characteristic of class A β-lactamase active sites, an SDN triad (positions 130 to 132), and an RSG triad (positions 234 to 236). The RSG triad is also known as R/K-S/T-G and is part of the conserved amino acid residues found in penicillin-recognizing proteins (PRPs) (1, 19, 20). DNA sequencing confirmed that PSE-4, CARB-3, and PSE-1 are closely related. PSE-1 differs from PSE-4 by one amino acid (A instead of E273), CARB-3 differs from PSE-4 by two amino acids (A instead of E273 and L instead of F193), and N-29 differs from PSE-4 by six amino acids.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid identity between carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzymes

| β-Lac- tamase | % Identity

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSE-4 | CARB-3 | CARB-4 | PSE-3 | AER-1 | PSE-1 | N-29 | GN79 | |

| CARB-3 | 99.31 | |||||||

| CARB-4 | 86.11 | 86.81 | ||||||

| PSE-3 | 44.01 | 44.37 | 42.25 | |||||

| AER-1 | 42.81 | 44.88 | 44.68 | 57.63 | ||||

| PSE-1 | 99.65 | 99.65 | 86.51 | 43.51 | 45.04 | |||

| N-29 | 97.92 | 97.92 | 86.16 | 43.86 | 45.39 | 98.27 | ||

| GN79 | 45.1 | 45.68 | 44.64 | 48.80 | 46.21 | 45.33 | 45.33 | |

| BRO-1 | 31.43 | 31.77 | 31.07 | 32.65 | 32.23 | 31.43 | 31.43 | 33.45 |

Curiously, we noted differences between the DNA sequence encoding PSE-3 and the deduced peptide sequence reported in the literature (8). To reconcile the DNA sequence with the amino acid sequence, the following changes were made: change of nucleotide G to C at position 148, change of nucleotide A to T at position 158, change of nucleotide C to G at position 159, and removal of nucleotide T at position 607.

Sequence of blaAER-1 encoding AER-1.

In pMON511 (Fig. 1C), the PvuII restriction site was mapped outside the AvaI fragment, in contrast to earlier reports (25), and the location is now supported by sequencing results. The entire nucleotide sequence obtained from the Sau3A DNA fragment shown in Fig. 2B is 1,727 nts long and encompasses the blaAER-1 structural gene with flanking sequences. From nts 1 to 83, we noted 100% homology with the 5′ region of sulII, as underlined in Fig. 2B (41). This sequence homologous to the upstream region of the dihydropteroate synthase (sulII) gene found in pLS88 and in the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010 suggested that the blaAER-1 gene is integrated in a transcriptional region and would have been acquired by the Ω7711 mobile element (41). We did not find homology to known genes in databases when we used sequences from nts 84 to 324. The blaAER-1 gene from nts 325 to 1239 in Fig. 2B was localized by translation of the 1,727 nts in all six frames. BLAST searches identified a single ORF of 304 amino acids encoding an AER-1 whose sequence was homologous to those of known β-lactamases, primarily PSE-3 found in class A. The sequence 100% homologous to the 5′ region of sulII had a G+C content of 48%, the 5′ region flanking blaAER-1 had G+C content of 54%, blaAER-1 had a G+C content of 54%, and the 3′ region flanking blaAER-1 had a G+C content of 52.7%.

The deduced peptide sequence of AER-1 had 57.6% identity with that of PSE-3, 44.9% identity with that of CARB-3, and 44.7% identity with that of CARB-4, as indicated in Table 3. A predicted signal sequence of 37 amino acids which would give a theoretical mature protein of 28,508 Da and a pI of 5.78 was identified. Analysis of the AER-1 amino acid sequence identified an STHK tetrad active site (amino acid positions 70 to 73). Other features typical of PRPs are underlined in Fig. 2B including an SDN (amino acid positions 130 to 132) and the KTG triad (amino acid positions 234 to 236), also known as R/K-S/T-G.

Homology and multiple alignment of CARB enzymes.

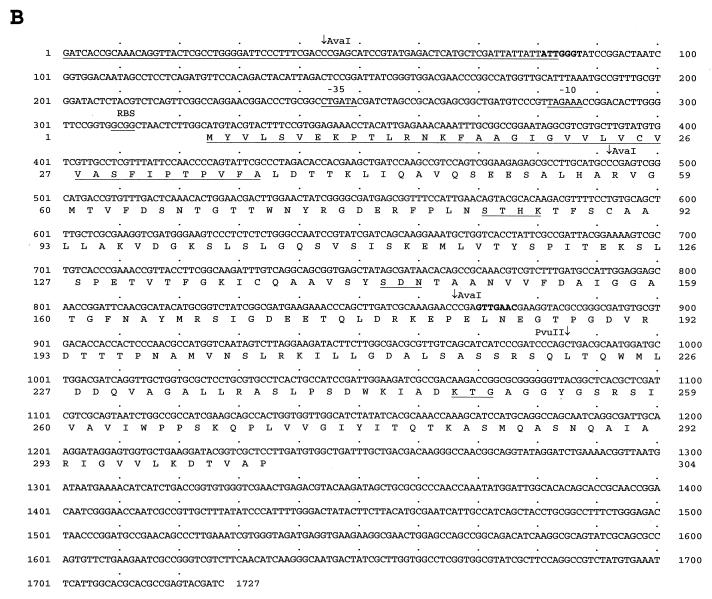

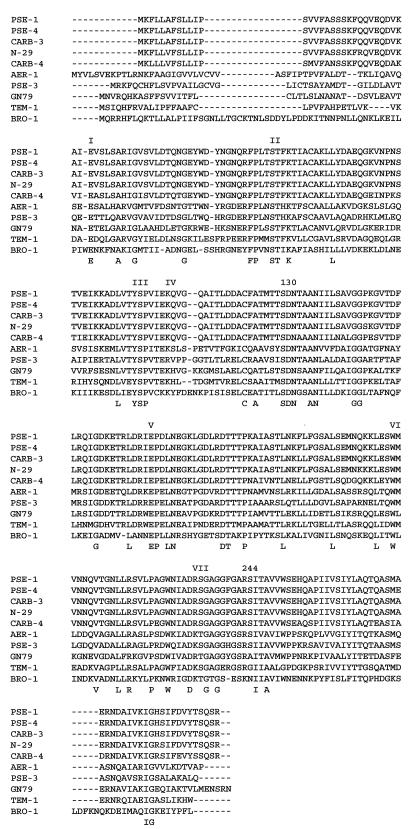

Since the CARB-4 and AER-1 β-lactamases hydrolyze carbenicillin at a high rate, we focused our analysis by comparisons of the CARB-4 and AER-1 enzymes with known class A and class D carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzymes (10). Comparisons of CARB-4 and AER-1 with class D enzymes having carbenicillin-hydrolyzing activity, such as LCR-1 and PSE-2, gave low levels of identity for CARB-4 (19.3 and 12.3%, respectively) and AER-1 (20.2 and 19.7%, respectively) (data not shown). In contrast, both CARB-4 and AER-1 had consistently higher (more than 30%) pairwise identities with class A enzymes (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, the BRO-1 enzyme was included in group 2c but has an identity of between 31.07 and 33.45% compared with other enzymes of group 2c. To better assess the degrees of relatedness between β-lactamases having so-called carbenicillin-hydrolyzing activities, defined as group 2c (7), we aligned CARB-4 and AER-1 with PSE-4, PSE-3, GN79, BRO-1, and TEM-1, as shown in Fig. 3. In the alignment the seven canonical amino acid boxes representing conserved motifs of PRPs are well conserved in CARB-4 as well as in AER-1.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the CARB-4 and AER-1 amino acid sequences with the sequences of class A enzymes with carbenicillin-hydrolyzing activity. PSE-1 is from P. aeruginosa RPL11 (17); PSE-4 is from P. aeruginosa Dalgleish (4); CARB-3 is from P. aeruginosa Cilote (23); N-29 is from P. mirabilis N-29 (47); PSE-3 is from P. aeruginosa ps142 (8; unpublished data); GN79 is from P. mirabilis GN-79 (38); BRO-1 is from Branhamella catarrhalis (unpublished data and GenBank accession no. U49269); TEM-1 is from pBR322 (45). Identical residues in eight proteins are indicated as a consensus sequence. The numbering of the amino acids follows standard nomenclature (1).

A phylogenetic tree was constructed (data not shown) on the basis of the alignment in Fig. 3, and it gave results similar to those presented previously (7): CARB-4 is clustered with PSE-1, CARB-3, Proteus mirabilis N-29, and PSE-4; AER-1 is clustered with P. mirabilis GN79; and PSE-3, BRO-1, and TEM-1 make up an outgroup.

Studies with a prototype class 2c β-lactamase to define catalysis and the interactions of specific amino acid residues with carboxypenicillins will be essential for elucidating the particularities in the structure and function of carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzymes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant to R.C.L. from the Canadian Centers of Excellence via the Canadian Bacterial Diseases Network. R.C.L. is a Research Scholar of Exceptional Merit from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P, Coulson A F W, Frère J-M, Ghuysen J-M, Joris B, Forsman M, Levesque R C, Tiraby G, Waley S G. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1991;276:269–272. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson T A, Smith M. In: Oligonucleotide synthesis: a practical approach. Gait M J, editor. Washington, D.C: IRL Press; 1984. pp. 35–81. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjellqvist B, Hughes G J, Pasquali C, Paquet N, Ravier F, Sanchez J-C, Frutiger S, Hochstrasser D F. The focusing positions of polypeptides in immobilized pH gradients can be predicted from their amino acid sequences. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:1023–1031. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501401163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boissinot M, Levesque R C. Nucleotide sequence of the PSE-4 carbenicillinase gene and correlations with Staphylococcus aureus PC1 β-lactamase crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1225–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brendel V, Trifonov E N. A computer algorithm for testing potential prokaryotic terminators. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4411–4427. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.10.4411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell J I A, Scahill S, Gibson T, Ambler R P. The phototrophic bacterium Rhodopseudomonas capsulata sp108 encodes an indigenous class A beta-lactamase. Biochem J. 1989;260:803–812. doi: 10.1042/bj2600803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couture F, Lachapelle J, Levesque R C. Phylogeny of LCR-1 and OXA-5 with class A and class D β-lactamases. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1693–1705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package), version 3.57c. Distributed by the author. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furth A J. Purification and properties of a constitutive β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain Dalgleish. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1975;377:431–433. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(75)90323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerry B, LeBlanc D J, Falkow S. General method for the isolation of plasmid deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1973;116:1064–1066. doi: 10.1128/jb.116.2.1064-1066.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall R M, Recchia G D, Collis C M, Brown H J, Stokes H W. Gene cassettes and integrons: moving antibiotic resistance genes in gram-negative bacteria. In: Amabile-Cuevas C F, editor. Antibiotic resistance: from molecular basics to therapeutic options. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes Company; 1996. pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hedges R W, Medeiros A A, Cohenford M, Jacoby G A. Genetic and biochemical properties of AER-1, a novel carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from Aeromonas hydrophila. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:479–484. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huovinen P, Jacoby G A. Sequence of the PSE-1 β-lactamase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2428–2430. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huovinen P, Huovinen S, Jacoby G A. Sequence of PSE-2 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:134–136. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joris B, Ghuysen J-M, Dive G, Renard A, Dideberg O, Charlier P, Frère J-M, Kelly J A, Boyington J C, Moews P C, Knox J R. The active site-serine penicillin-recognizing enzymes as member of the Streptomyces R61 dd-peptidase family. Biochem J. 1988;250:313–324. doi: 10.1042/bj2500313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joris B, Ledent P, Dideberg O, Fonze E, Lamotte-Brasseur E, Kelly J, Ghuysen J-M, Frère J M. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kahn M, Kolter R, Thomas C, Figurski D, Meyer R, Remaut E, Helinski D R. Plasmid cloning vehicles derived from plasmids ColE1, F, R6K and RK2. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:268–280. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labia R, Guionie M, Barthélémy M. Properties of three carbenicillin-hydrolysing β-lactamases (CARB) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of a new enzyme. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981;7:49–56. doi: 10.1093/jac/7.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lachapelle J, Dufresne J, Levesque R C. Characterization of blaCARB-3 encoding the carbenicillinase-3 β-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1991;102:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90530-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levesque R C, Jacoby G A. Molecular structure and interrelationships of multiresistance β-lactamase transposons. Plasmid. 1988;19:21–29. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(88)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levesque R C, Medeiros A A, Jacoby G A. Molecular cloning and DNA homology of plasmid-mediated β-lactamase genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;206:252–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00333581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livermore D M, Jones C S. Characterization of NPS-1, a novel plasmid-mediated β-lactamase from two Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:99–103. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livermore D M, Maskell J P, Williams D J. Detection of PSE-2 β-lactamase in enterobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:268–272. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercier J, Lachapelle J, Couture F, Lafond M, Vezina G, Boissinot M, Levesque R C. Structural and functional characterization of tnpI, a recombinase locus in Tn21 and related β-lactamase transposons. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3745–3757. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3745-3757.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Messing J. New M13 vectors for cloning. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:20–78. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messing J, Vieira J, Yanish-Perron C C. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. Expert system for predicting protein localization sites in gram-negative bacteria. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1991;11:95–110. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newsom S W B. Carbenicillin-resistant Pseudomonas. Lancet. 1969;ii:1141. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90742-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, Heijne G V. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliver D. Protein secretion in Escherichia coli. Rev Microbiol. 1985;39:615–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paul G, Joly-Guillou M L, Bergogne-Berezin E, Nivot P, Philippon A. Novel carbenicillin-hydrolyzing β-lactamase (CARB-5) from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus var. anitratus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;59:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philippon A M, Pamp G C, Thabaut A P, Jacoby G A. Properties of a novel carbenicillin-hydrolyzing enzyme (CARB-4) specified by IncP2 plasmid from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:519–520. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose R E. The nucleotide sequence of pACYC184. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:355. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.1.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakurai Y, Tsukamoto K, Sawai T. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of a carbenicillin-hydrolyzing penicillinase gene from Proteus mirabilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7038–7041. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.7038-7041.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholz P, Haring V, Wittmann-Liebold B, Ashman K, Bagdasarian M, Scherzinger E. Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization of the broad-host range plasmid RSF1010. Gene. 1989;75:271–288. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segatore B, Massida O, Satta G, Setacci D, Amicosante G. High specificity of cphA-encoded metallo-β-lactamase from Aeromonas hydrophila AEO36 for carbapenems and its contribution to β-lactam resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1324–1328. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silhavy T J, Berman M L, Enquist L W. Experiments with gene fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spratt B G, Hedge P J, te Heesch S, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–341. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutcliffe J G. Nucleotide sequence of the ampicillin resistance gene of Escherichia coli plasmid pBR322. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3737–3741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sykes R B, Matthew M. The β-lactamase of gram-negative bacteria and their role in resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1976;2:115–157. doi: 10.1093/jac/2.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi I, Tsukamoto K, Harada M, Sawai T. Carbenicillin-hydrolysing penicillinase of Proteus mirabilis and the PSE-type penicillinases of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Immunol. 1983;27:995–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1983.tb02934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]