Abstract

Purines are required for fundamental biological processes and alterations in their metabolism lead to severe genetic diseases associated with developmental defects whose etiology remains unclear. Here, we studied the developmental requirements for purine metabolism using the amphibian Xenopus laevis as a vertebrate model. We provide the first functional characterization of purine pathway genes and show that these genes are mainly expressed in nervous and muscular embryonic tissues. Morphants were generated to decipher the functions of these genes, with a focus on the adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL), which is an enzyme required for both salvage and de novo purine pathways. adsl.L knockdown led to a severe reduction in the expression of the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs: Myod1, Myf5 and Myogenin), thus resulting in defects in somite formation and, at later stages, the development and/or migration of both craniofacial and hypaxial muscle progenitors. The reduced expressions of hprt1.L and ppat, which are two genes specific to the salvage and de novo pathways, respectively, resulted in similar alterations. In conclusion, our data show for the first time that de novo and recycling purine pathways are essential for myogenesis and highlight new mechanisms in the regulation of MRF gene expression.

Keywords: metabolic disease, myogenic regulatory factors, hypaxial muscle progenitors, adenylosuccinate lyase, yeast model

1. Introduction

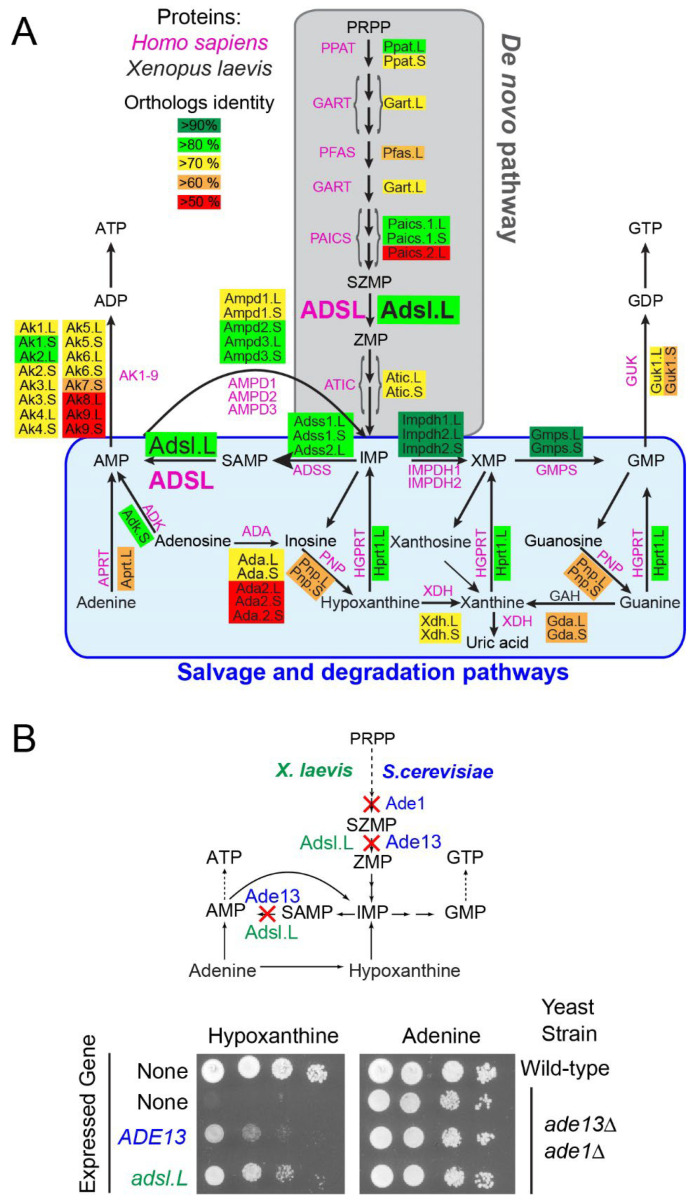

Purine triphosphate nucleotides, ATP and GTP are synthesized via a highly conserved [1] de novo pathway, allowing for sequential construction of the purine ring on a ribose phosphate moiety provided by phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) (Figure 1A and Figure S1 for details). This de novo pathway results in the synthesis of inosine 5′-monophosphate (IMP), which can be converted into either AMP or GMP and then into other phosphorylated nucleotide forms required for all known forms of life. These nucleotides can alternatively be synthetized via a salvage pathway using precursors taken up from the extracellular medium or coming from the internal recycling of preexisting purines (Figure 1A). Purines and their derivatives (such as NAD(P) (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate)), FAD (Flavin adenine dinucleotide), coenzyme A, ADP-ribose, S-adenosyl-methionine and S-adenosyl-homocysteine) form a family of metabolites among the most abundant (mM range) in cells and are involved in a myriad of physiological events. Purines are required for numerous cellular processes, such as the biosynthesis of nucleic acids and lipids; replication; transcription; translation; maintenance of energy and redox balances; and regulation of gene expression (methylation, acetylation, etc.) and cell signaling, such as the purinergic signaling pathway [2]. Therefore, defects, even minor ones, in the purine de novo biosynthesis or recycling pathways lead to deleterious physiological effects. Indeed, to date, no less than 35 rare genetic pathologies have been associated with purine metabolism dysfunctions [3,4,5,6,7].

Figure 1.

The X. laevis adsl.L gene encodes the adenylosuccinate lyase activity required in two non-sequential steps of the highly conserved purine synthesis pathways. (A) Schematic representation of the human and X. laevis purine biosynthesis pathways. Abbreviations: AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, Inosine monophosphate; PRPP, Phosphorybosyl pyrophosphate; SAMP, Succinyl-AMP; SZMP, Succinyl-Amino Imidazole Carboxamide Ribonucleotide monophosphate; XMP, Xanthosine monophosphate; ZMP, Amino Imidazole CarboxAmide Ribonucleotide monophosphate. (B) Functional complementation of the growth defect of the yeast adenylosuccinate lyase deletion mutant via expression of the X. laevis adsl.L ortholog gene. Yeast wild-type and adsl knockout mutant (ade13 ade1) strains were either transformed with a plasmid, allowing for expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ADE13) or the X. laevis (adsl.L) adenylosuccinate lyase encoding genes, or with the empty vector (None). Serial dilutions (1/10) of transformants were dropped on SDcasaWA medium supplemented with either hypoxanthine or adenine as the sole external purine source. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C before imaging. Of note, the ade1 ade13 double deletion mutant was used in this experiment to avoid genetic instability associated with the accumulation of SZMP and/or its nucleoside derivatives observed in the single ade13 mutant [8].

Purine-associated pathologies share a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms, including hyperuricemia, immunological, hematological and renal manifestations, as well as severe muscular and neurological dysfunctions [3,4]. They are all characterized by abnormal levels of purine nucleotides, nucleosides and/or nucleobases in the patient’s body fluids and/or cells. Although in most cases, the mutated gene has been identified, the causal link between the defective enzyme, the decrease in some final products, the accumulation of purine intermediates or the alteration of physiological functions with the observed symptoms often remains very elusive, even unknown.

The adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency (OMIM 103050) is one of the most studied purine metabolism pathologies in which the functions of the Adsl enzyme, which catalyzes two non-consecutive reactions required both for the salvage and de novo purine pathways, are altered (Figure 1A). First described in 1984 [9], this rare autosomal recessive disorder is associated with a massive accumulation of succinyl derivatives (Succinyl-adenosine and Succinyl-AICAR (AminoImidazole CarboxAmide Ribonucleoside)) corresponding to dephosphorylation of the monophosphate substrates of Adsl (SZMP and SAMP, Figure 1A) in patient fluids (blood, urine and cerebrospinal fluid). The first patient-specific mutation in the ADSL gene was identified in 1992 [10] and, to date, more than 50 different mutations have been described [11] (Figure S2, orange and yellow boxes). All the biochemically studied mutations lead to a low residual Adsl enzymatic activity [12,13,14,15,16]. This pathology is characterized by serious neuromuscular dysfunctions, including psychomotor retardation, brain abnormalities, autistic features, seizures, ataxia, axial hypotonia, peripheral hypotonicity, muscular wasting and growth retardation [14,17,18]. Three distinct forms of ADSL deficiency have been categorized based on the severity of the symptoms: a fatal neonatal form (respiratory failure causing death within the first weeks of life), a childhood form with severe neuromuscular symptoms (severe form; type I) and a more progressive form with milder symptoms (mild form; type II) (for review see [19]). A robust correlation has been clearly established between the residual activity of Adsl, the consequent accumulation of succinyl derivatives and the intensity of phenotypes [16,20,21,22]. However, these studies do not explain the molecular bases associated with ADSL deficiency, though they raise a real interest in identifying biological functions that could be modulated by SZMP, SAMP and their derivatives. For example, SZMP acts as a signal metabolite that regulates transcriptional expression in yeast [8] and promotes proliferation in cancer cells by modulating pyruvate kinase activity [23], while SAMP stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic cells [24]. More recently, RNA-seq analysis of a cellular model of ADSL deficiency identified the misexpression of genes involved in cancer and embryogenesis, bringing some first clues to understanding the molecular bases of this rare disease [25].

To go further into the etiology of this disease, it is now essential to identify the different biological processes that are altered by a purine deficiency during embryonic development, as the most severe symptoms appear in utero or within the first weeks or months after birth. To our knowledge, few invertebrate and vertebrate models have been developed to study this disease and no mammalian model recapitulating ADSL deficiency exists, most likely due to embryonic lethality [26,27]. Here, we established an X. laevis model to assess the developmental functions of ADSL by knocking down its embryonic expression. This powerful vertebrate model organism has been widely used to identify developmental impairments associated with human pathologies [28,29].

We report the identification and functional validation of the adsl.L gene and show this gene as being mostly expressed in the nervous and muscular tissues during X. laevis development. The knockdown of adsl.L results in downregulation at different developmental stages of several myogenic regulating factor (MRF) expressions, such as Myod1, Myf5 and Myogenin, and leads to alterations in somites, craniofacial and hypaxial muscle formation, thus showing that adsl.L is essential for myogenesis. Finally, functional comparative analysis of other enzymes in the de novo and salvage purine pathways (ppat.L, ppat.S and hprt1.L) highlights a major role for purine metabolism in muscle tissue development, providing insight into the developmental defects that underlie some of the symptoms of patients with severe ADSL deficiency, as well as other purine-associated pathologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Media

SDcasaW is an SD medium (0.5% ammonium sulfate, 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (BD-Difco; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and 2% glucose) supplemented with 0.2% casamino acids (#A1404HA; Biokar/Solabia group; Pantin, France) and tryptophan (0.2 mM). When indicated, adenine (0.3 mM) or hypoxanthine (0.3 mM) was added as an external purine source in SDcasaW.

2.2. Yeast Strains and Plasmids

All yeast strains are listed in Table S1 and belong to or are derived from a set of disrupted strains isogenic to BY4741 or BY4742 purchased from Euroscarf (Oberursel, Germany). Double mutant strains were obtained via crossing, sporulation and micromanipulation of meiosis progeny. All plasmids (Table S2) were constructed using the pCM189 vector [30], allowing for the expression of the X. laevis gene in yeast under the control of a tetracycline-repressible promoter. X. laevis open reading frame (ORF) sequences were amplified using PCR from I.M.A.G.E Clones (Source Biosciences; Nottingham, UK). All X. laevis ORF sequences were fully verified via sequencing after cloning in the pCM189 vector. Further cloning details are available upon request.

2.3. Yeast Growth Test

For the drop tests, yeast transformants were pre-cultured overnight on a solid SDcasaWA medium, re-suspended in sterile water at 1 × 107 cells/mL and submitted to 1/10 serial dilutions. Drops (5 μL) of each dilution were spotted on freshly prepared SDcasaW medium plates supplemented or not with adenine or hypoxanthine. Plates were incubated either at 30 or 37 °C for 2 to 7 days before imaging.

2.4. Embryo Culture

X. laevis males and females were purchased from the CNRS Xenopus Breeding Center (CRB, Rennes, France). Embryos were obtained via in vitro fertilization of oocytes collected in 1× Marc’s Modified Ringers saline solution (1× MMR: 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) from a hormonally (hCG (Centravet, Nancy, France), 450 units) stimulated female by adding crushed testis isolated from a sacrificed male. Fertilized eggs were de-jellied in 3% L-cysteine hydrochloride, pH 7.6 (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck group, Darmstadt, Germany), and washed several times with 0.1 × MMR. Embryos were then cultured to the required stage in 0.1× MMR in the presence of 50 µM of gentamycin sulfate. Embryos were staged according to the Nieuwkoop and Faber table of X. laevis development [31].

2.5. mRNA Synthesis and Morpholino Oligonucleotides

Capped mRNAs were synthesized using Sp6 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kits (Ambion, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) from linearized plasmids (listed in Table S3). adsl.L, ppat.S, ppat.L and hprt1.L RNA were transcribed from the IMAGE clones. adsl.L-RNA*, ppat.S-RNA*, ppat.L-RNA* and hprt1.L* ORFs were amplified using PCR in conditions that allow for the introduction of mutations in the morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) binding site and were subcloned into the plasmid pBF. Homo sapiens ADSL cDNA was subcloned into the plasmid pCS2+. adsl.L MO1 (5′-AAGCATGGAGGGGAGCAGTGGGCTAAG-3′), adsl.L MO2 (5′-ATGGAGGGGAGCAGTGGGCTAAGCAT-3′), hprt1.L MO (5′-GGACACAGGCTCAGACATGGCGAGC-3′), ppat.L/ppat.S MO (5′-GTGATGGAGTTTGAGGAGCTGGGGAT-3′) and standard control MO (cMO) were designed and supplied by Gene Tools, LLC. The position of the MOs in relation to their respective RNA is indicated in Figure S3.

2.6. Microinjections

Embryos were injected with MO alone or in combination with MO non-targeted mRNA (mutated adsl.L RNA* or Homo sapiens ADSL, as specified in the text/legend) into the marginal zone of one blastomere at the 2-cell stage. LacZ (250 pg) RNA was co-injected as a lineage tracer. Embryos were injected in 5% Ficoll, 0.375× MMR, cultured to various developmental stages, fixed in MEMFA (MOPS 100 mM pH 7.4, EGTA 2 mM, MgSO4 1 mM, 4.0% (v/v) formaldehyde) and stained for β-galactosidase activity using Red-Gal or X-Gal substrates (RES1364C-A103X or B4252, Merck) to identify the injected side and correctly targeted embryos. Embryos were fixed again in MEMFA before dehydration into 100% methanol or ethanol for immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization, respectively.

2.7. In Situ Hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations (ISHs) were carried out as previously described [32,33,34]. Sense and antisense riboprobes were designed by subcloning fragments of coding cDNA sequences in pBlueScript II (SK or KS) plasmids (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). Riboprobes were generated by in vitro transcription using the SP6/T7 DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland, #11175025910) after plasmid linearization, as indicated in Table S4. Riboprobe hybridization detection was carried out with an anti-DIG Alkaline Phosphatase antibody (Roche, #11093274910) and the BM-Purple AP substrate (Roche, #11442074001). Riboprobes for lbx1, mespa, myf5, myod1, myogenin, pax3, tbxt (xbra) and tcf15 were previously described [35,36,37].

2.8. Immunostaining

Whole-mount immunostaining of differentiated skeletal muscle cells was performed using the monoclonal hybridoma 12-101 primary antibody [38] (1/200 dilution; DSHB #AB-531892) and the EnVision+ Mouse HRP kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA, K4007) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

2.9. Temporal Expression of Genes Established Using RT-PCR

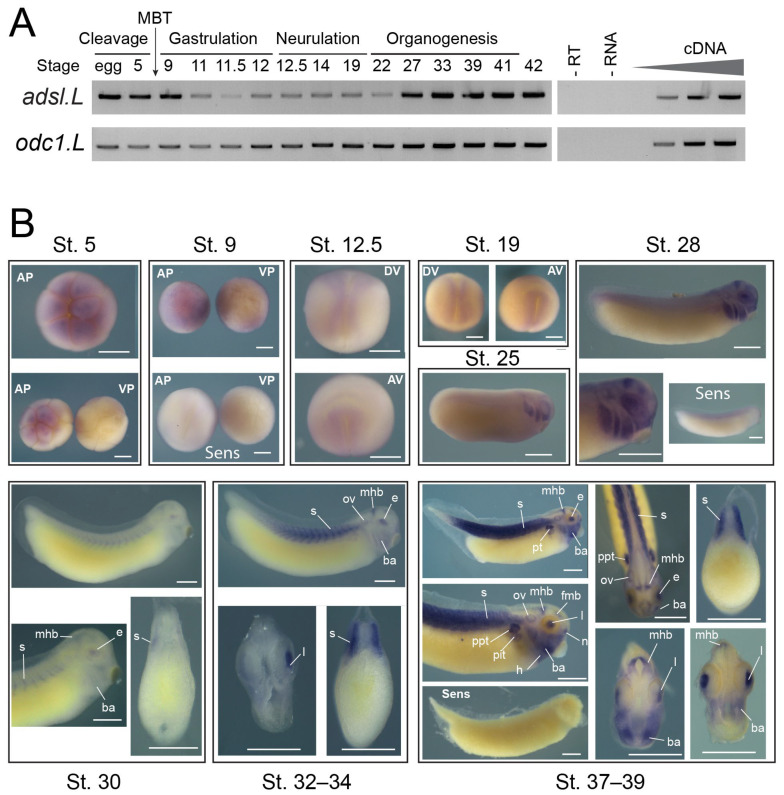

RNA extraction from whole embryos, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR were performed as previously described [33,39]. Sequences of the specific primers designed for each gene and PCR amplification conditions are given in Table S5. Chosen primers were selected to differentiate homeolog gene expression and to discriminate potential genomic amplification from cDNA amplification. PCR products were verified via sequencing (Eurofins genomics). The quantity of input cDNA was determined via normalization of the samples with the constant ornithine decarboxylase gene odc1.L [40]. Linearity of the signal was controlled by carrying out PCR reactions on doubling dilutions of cDNA and negative controls without either RNAs, reverse transcriptase or cDNA were also performed. Experiments were done at least twice on embryos from two different females (N ≥ 2) and representative profiles are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Spatiotemporal expression of adsl.L gene during X. laevis embryonic development. (A) Temporal expression profiles of adsl.L gene during embryogenesis. The expression profile was determined using RT-PCR from the cDNA of the fertilized oocyte (egg) and whole embryo at indicated stages covering the different phases of X. laevis embryogenesis. The ornithine decarboxylase gene odc1.L was used as a loading control and negative controls were performed by omitting either reverse transcriptase (-RT) or RNA (-RNA) in the reaction mix. Linearity was determined via dilutions of cDNA from stage 39 for adsl.L and 41 for odc1.L. Mid-blastula transition (MBT) is indicated. (B) Spatial expression profile of adsl.L gene during embryogenesis. Whole-mount in situ hybridization with adsl.L-specific DIG-labeled antisense or sense RNA probes was performed on embryos from stages (St.) 5 to 37–39. St. 5 and 9: animal (AP) and vegetal (VP) pole views, St. 12.5 and 19: dorsal (DV) and anterior (AV) views; later stages: lateral views, with dorsal up and anterior on the right, and dorsal view at stages 37–39. Transverse sections are dorsal up. Abbreviations: ba, branchial arches; e, eye; fmb, forebrain–midbrain boundary; h, heart; l, lens; mhb, midbrain–hindbrain boundary; n: nasal placode; ov, otic vesicle; ppt, pronephric proximal tubules; pit, pronephric intermediate tubules; s, somites. Bars: 0.5 mm.

2.10. Embryo Scoring and Photography

Embryos were bleached (1% H2O2, 5% formamide, 0.5× SSC) to remove all visible pigment, and phenotypes were determined in a commonly used way, i.e., blind-coded, by comparing the injected and un-injected sides. Only embryos with normal muscle tissue formation on the un-injected side and correctly targeted β-galactosidase staining on the injected side were scored. Transverse sections were performed with a razor blade on fixed embryos. Embryos were photographed using an SMZ18 binocular system (Nikon, Minato City, Tokyo, Japan).

2.11. Statistics and Reproducibility

All experiments were carried out on at least two batches of fertilized eggs from two independent females (N ≥ 2). Histograms represent the percentage of embryos displaying each phenotype and the number of embryos in each category is indicated in the bars of each histogram. Fisher’s exact test was used for the statistical analyses and p-values are presented above the bars of the histogram in all figures.

2.12. Bioinformatics

Sequences were identified on the NCBI and Xenbase databases [41]. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) searches were performed on the NBCI Nucleotide and the Xenbase X. laevis 9.1 Scaffolds genome databases [42]. Conceptual translation of complementary DNA (cDNA) was performed on the ExPASy Internet website using the program Translate Tool (web.expasy.org/translate/, accessed on 1 September 2017). A comparison of the coding sequences from H. sapiens, S. cerevisiae, X. laevis and X. tropicalis was done on https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (2022). Accession numbers of all sequences used in this study are given in Tables S6 and S7.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of X. laevis Purine Pathway Genes

The purine biosynthesis pathways are known to be highly conserved throughout evolution [1]. Most of X. laevis genes encoding potential purine-pathway enzymes have been putatively identified and annotated via automated computational analyses from the entire genome sequencing [43]. Protein sequences were deduced from the conceptual translation of these annotated genes and aligned with their potential orthologs, e.g., H. sapiens and X. tropicalis (Table S6). The vast majority of X. laevis de novo and salvage pathways have two homeologs, whose protein sequences display a high degree of identity with their X. tropicalis and human orthologs (more than 85 and 50%, respectively; Figure 1A and Table S6), suggesting that these annotated genes effectively encode the predicted purine pathway enzymes.

To establish that the putative X. laevis purine pathway genes encode the predicted enzymatic activities, a functional complementation assay was undertaken via heterologous expression of X. laevis genes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which was shown to be a valuable model to investigate metabolic pathways [44]. Yeast knockout mutants were available in the laboratory and sequence alignments showed a high degree of identity between S. cerevisiae and X. laevis orthologous protein sequences (Figure S1 and Table S7). Plasmids allowing for expression of the X. laevis ORF in S. cerevisiae were transformed in the cognate yeast knockout mutant, and functional complementation was tested. As shown in Figure 1B, the yeast adsl knockout mutant (ade13) was unable to grow in the presence of hypoxanthine as a unique purine source, but growth was restored by the expression of either the S. cerevisiae ADE13 or the X. laevis adsl.L gene. By contrast, all these strains were able to grow in the presence of adenine, which allowed for purine synthesis via the adenine phosphoribosyl transferase (Apt1) and AMP deaminase (Amd1) activities (Figure S1). Similar experiments were conducted with 15 other X. laevis purine-pathway-encoding genes, 13 of which were able to complement the S. cerevisiae cognate knockout mutants (Figures S4 and S5). Altogether, this data allowed us to functionally validate adsl.L and 13 other X. laevis genes involved in purine de novo and recycling pathways, demonstrating that the purine pathways were functionally conserved in X. laevis.

We then focused on the role of adenylosuccinate lyase, as (1) it is encoded by a single gene (adsl.L), greatly simplifying the knockdown experiments, and its protein sequence is highly conserved between human and X. laevis (Figure S2); (2) it is the only enzymatic activity that is required in both the de novo biosynthesis and recycling purine pathways; and (3) its mutation leads to severe developmental alterations, for which the molecular bases associated with the symptoms are still largely unknown.

3.2. The adsl.L Gene Was Mostly Expressed in Muscular and Neuronal Tissues and Their Precursors during X. laevis Development

adsl.L spatiotemporal expression during X. laevis development was established via two complementary approaches. First, its temporal expression profile was determined using RT-PCR on whole embryos from fertilized egg to stage 45 (Figure 2A). The adsl.L gene displays both a maternal (before the mid-blastula transition (MBT)) and a zygotic expression at all developmental stages studied.

adsl.L spatial expression was then determined via in situ hybridization (Figure 2B). adsl.L expression is detected in the animal, but not vegetal, pole during the cleavage phase. Zygotic expression was detected in the neuroectoderm and the paraxial mesoderm during neurulation. From stage 25 until the late organogenesis stages, adsl.L expression was found in the developing epibranchial placodes, lens and in the central nervous system (fore–midbrain and mid–hindbrain boundaries). From stage 30 onward, adsl.L transcripts were also detected in the somites and its somitic expression appeared to increase during organogenesis. At the late organogenesis stage, its expression was detected in other mesoderm-derived tissues, such as the pronephric tubules (proximal and intermediate tubules) and the heart.

Using similar approaches, we showed that (1) 14 out of the 16 tested genes display a similar temporal expression profile to that of adsl.L (Figure S6) and (2) all 9 genes tested using in situ hybridization were expressed in neuromuscular tissues (e.g., somites, hypaxial muscles, central nervous system and retinas), even if differences in the tissue specificity existed for some of these genes (Figures S7 and S8). These spatiotemporal expression patterns are consistent with the fact that neuromuscular dysfunctions are the primary symptoms associated with purine-dependent diseases.

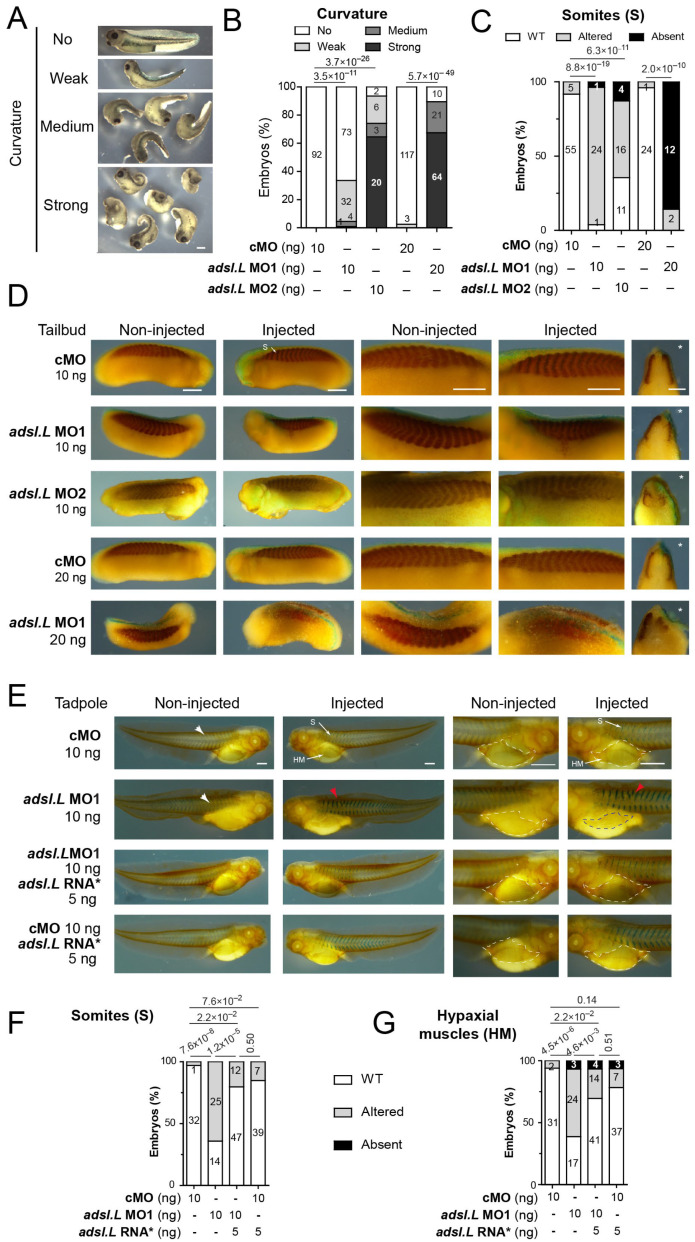

3.3. The adsl.L Gene Was Required for X. laevis Myogenesis

To understand the role of adsl.L during muscle development, we undertook a loss of function approach using two specific anti-sense morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) (see Figure S3A for MOs efficiency). MO injections were performed in the marginal zone of one blastomere at the two-cell stage. This injection has the advantage of unilaterally affecting the development of the future mesoderm, with the non-injected side serving as an internal control. A dose-dependent curvature along the anteroposterior axis was observed following the injection of adsl.L MO1 and MO2, and not of the control morpholino (cMO), with a concave deformation always corresponding to the side of the injection (Figure 3A,B). This curvature phenotype was already documented when myogenesis was altered [45], suggesting that adsl.L gene could be required for proper muscle formation in X. laevis. To test this hypothesis, we performed immunostaining on tailbud and tadpole stages with the differentiated skeletal-muscle-cell-specific 12-101 antibody [38]. The cMO-injected embryos displayed normal global morphology and normal muscle phenotype at all stages tested. By contrast, myotomes were smaller along the dorsoventral axis following the injection of 10 ng of adsl.L MO1 or MO2 at the tailbud stage (Figure 3C,D). Furthermore, the somite morphology was considerably altered. Straight-shape somites, blurred somite domains and fewer v-shaped somites were observed on the injected side. The 12-101-positive area was also reduced along the anteroposterior axis, with the latter shortening most likely being at the origin of the curvature phenotype observed (Figure 3A). This muscle alteration was even more exacerbated by increasing the dose of MO, with severe reduction and, in some cases, absence of a 12-101-positive domain and no somitic-like structure observed on the injected side in more than 80% of the injected 20 ng MO1 embryos (Figure 3C). This dose-dependent muscle phenotype was still observed in the tadpole stage (stage 39), with a similar percentage of adsl.L morphant embryos displaying myotome reduction and altered chevron-shaped somites in their injected side, especially in the anterior trunk region (Figure S9A,B). At the late tadpole stage (stage 41), somite defects, which were characterized by anterior straight or criss-crossed somites, were observed on the injected side of adsl.L morphants (red arrowheads; Figure 3E,F), whereas the cMO embryo injected side displayed the characteristic v-shaped somites (white arrowheads; Figure 3E,F). Reduction in the hypaxial muscles (precursors of the limb muscles) was also observed in adsl.L morphants but not in cMO-injected embryos (Figure 3E,G; compare the blue to the white dashed areas in adsl.L MO1 embryo). This hypaxial muscle phenotype was worsened when the MO dose was increased with no hypaxial muscle progenitors in 70% and 96% of analyzed embryos following 10 ng and 20 ng of adsl.L MO1 injection, respectively (Figure S9A,C). These phenotypes were rescued by co-injecting adsl.L MO1 with the adsl.L mutated RNA*, whose translation was unaffected (Figure S3A) by adsl.L MO1 and MO2 (Figure 3E–G). No significant phenotype was obtained by co-injecting the adsl.L RNA* with cMO (Figure 3E–G). Together, these results validate the muscular-associated phenotypes as a consequence of a specific adsl.L gene knockdown and not of the potential morpholino injection’s side effects.

Figure 3.

The adsl.L gene is required for somites and hypaxial muscle formation in X. laevis. (A) Representative images of adsl.L morphants following adsl.L MO1 injection at either 10 ng (weak and medium curvature) or 20 ng (medium and strong curvature). (B) Quantification and statistics of the curvature phenotype. (C–G) Immunostaining with the differentiated muscle-cell-specific 12-101 antibody revealed a strong alteration of somites and hypaxial muscle formation in adsl.L knockdown and adsl.L overexpressing embryos. Representative images (D,E) and quantification and statistics (C,F,G) of somites and hypaxial muscles phenotype at tailbud (C,D) and tadpole (E–G) stages. Injected side is indicated by asterisks. S, somites; HM, hypaxial muscles. Bars: 0.5 mm. White and red arrowheads point to typical somite chevron shapes and altered somites, respectively. The adsl.L RNA* refers to mutated RNA whose translation was not affected by the adsl.L specific MOs (Figure S3). Numbers above the bars of histograms correspond to p-values.

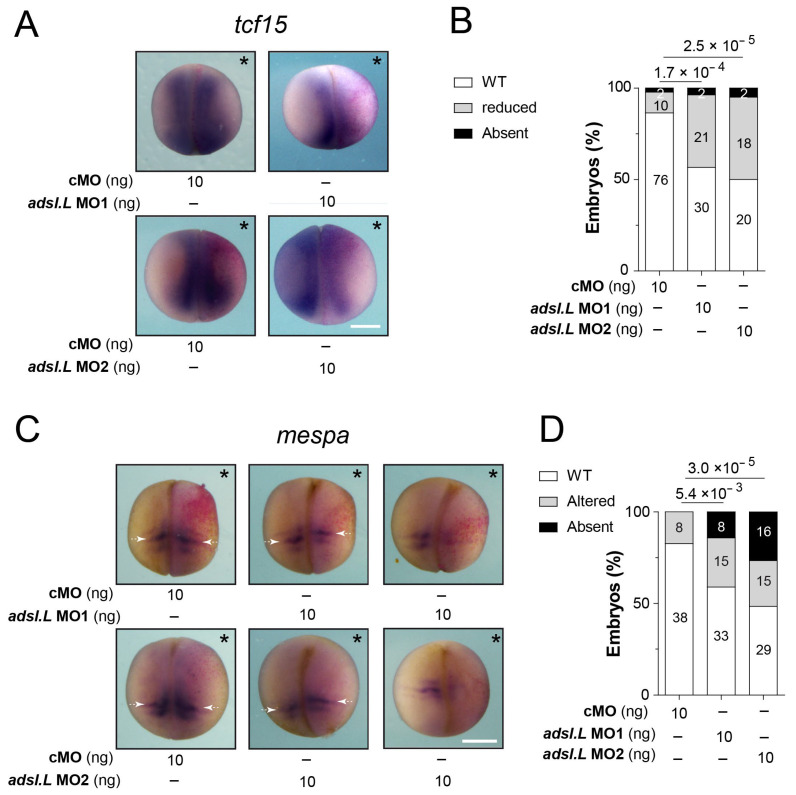

To confirm the adsl.L gene implications during myogenesis, the expressions of tcf15 (paraxis) and mespa (thylacine 1) genes were analyzed in adsl.L MO1 and MO2 morphants at late neurula stages (stages 17–19). As expected, tcf15 expression was observed in the dorsolateral part of the somites [35] following the control cMO injection. However, its expression domain was reduced following adsl.L knockdown (Figure 4A,B), suggesting that the primitive myotome formation was impacted in adsl.L morphants. Alterations in the expression of mespa, which is a somitomere marker [46,47], were also observed in adsl.L knockdown conditions (Figure 4C,D). These alterations included a reduction in, and even an absence of, mespa stripes number and their lateral length. The most frequent phenotype was a shift to a more anterior position in the presomitic mesoderm (white arrows, Figure 4C). These significant phenotypes suggest that adsl.L was involved in the segmentation of the presomitic mesoderm.

Figure 4.

The adsl.L gene is required for the expression of tcf15 and mespa genes involved in early somitogenesis. Expression of tcf15 (A,B) and mespa (C,D) genes at late neurula stage is altered by the knockdown of adsl.L gene. Representative images of trf15 (A) and mespa (C) RNA expression revealed via in situ hybridization. Statistics are shown in (B) and (D) for trf15 and mespa RNA, respectively. White arrows point to the anterior domain of the somitomere S-II on both sides of the embryos. Injected side is indicated by asterisks. Numbers above the bars of histograms correspond to p-values. Bars: 0.5 mm.

To determine whether the observed muscle phenotypes were specifically related to the knockdown of the adsl.L gene or to the purine pathways alteration, similar loss of function experiments (see Figure S3B,C for the MOs efficiencies) were carried out on other purine-associated genes: (1) the ppat (ppat.L and ppat.S) genes encoding the phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase (Ppat), which is the first enzyme of the purine de novo pathway, and (2) the hprt1.L gene encodin Hypoxanthine-PhosphoRybosylTransferase (Hprt) in the salvage pathway (Figure 1A), which is the enzyme that allows for metabolization of hypoxanthine, which is the major purine source in X. laevis embryos [48]. Comparable muscle alterations were obtained with independent knockdown of these genes, i.e., a strong alteration of somite shape at both the tailbud and tadpole stages, which were associated with smaller myotomes at the early organogenesis stage and reduction in, or even absence of, hypaxial muscles in the latter stages (Figures S10 and S11). Myogenesis alterations were also observed at the neurula stages (Figures S12 and S13). A reduction in the tcf15 expression domain was observed following ppat and hprt1.L MO injection (Figure S12). Furthermore, the formation of somitomeres was disrupted in ppat and hprt1.L morphants, which showed a shift and number reduction of mespa stripes on the injected side (Figure S13).

Taken together, these similar muscle phenotypes observed in adsl.L, ppat and hrpt1.L morphants demonstrated a strong association between altered purine pathways and defects in somitogenesis and myogenesis.

3.4. Expression of the myod1 and myf5 Genes Required Functional Purine Pathways

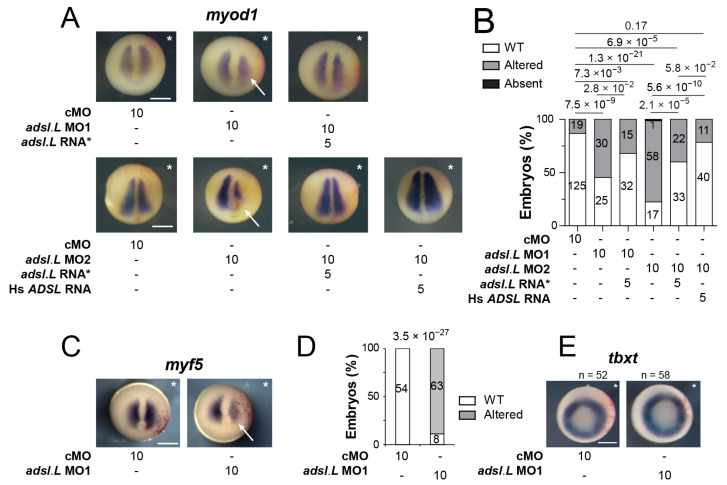

We assessed whether the muscular phenotypes observed upon the knockdown of purine-associated genes could result from an alteration of the myogenic regulatory factors’ (MRFs’) expression during the different myogenic waves [36,49]. The expression of both myod1 and myf5 was first analyzed via in situ hybridization at the early neurula stage, during the first myogenic wave (Figure 5A–D). A strong reduction in both myod1 and myf5 expression was observed on the injected side of adsl.L morphants (Figure 5A,C), whereas no alteration could be seen in the cMO-injected embryos. This significant reduction was even stronger in the anterior region, which gave rise to the first somites. Importantly, myod1 expression was rescued by the injection of X. laevis adsl.L mutated RNA* or human ADSL RNA in adsl.L MO1 and MO2 morphants (Figure 5A,B). These results are consistent with an adenylosuccinate lyase activity, even when heterologous, which is required for the proper expression of myod1. Of note, the overexpression of either X. laevis adsl.L mutated RNA* or human ADSL mRNA induced a small but significant increase in myod1 expression (Figure S14). To exclude the idea that the observed reduction of myod1 and myf5 expression resulted from an alteration of mesoderm formation and/or integrity in adsl.L morphants, expression of the pan-mesoderm marker tbxt (xbra) was analyzed via in situ hybridization on whole embryos at stage 11. No significant difference was observed in all injected embryos (Figure 5E). Finally, a strong and similar reduction in myod1 expression, with no alteration of the tbxt gene expression pattern, was also observed in either ppat.L/ppat.S or hprt1.L morphants (Figure S15). Altogether, these results show that functional purine synthesis is strictly required for a proper expression of the myogenic regulatory factor genes myod1 and myf5 during the first myogenic wave.

Figure 5.

Expression of the myogenic regulatory factors myod1 and myf5 in paraxial mesoderm was strongly affected by the knockdown of the adsl.L gene. (A) Expression of myod1 gene at the early neurula stage was altered by the knockdown of adsl.L gene and rescued by adsl.L RNA* and human ADSL RNA. (C) Representative images of the effect on myf5 RNA expression by adsl.L knockdown at stage 12.5 revealed via in situ hybridization. (B,D) Quantification and statistics of the myod1 and myf5 expression phenotypes are presented in (A,C), respectively. (E) Knockdown of adsl.L did not alter the mesoderm formation, as revealed by the absence of change in tbxt (xbra) RNA expression domain at stage 11. Injected side is indicated by asterisks. The amounts of MO and RNA presented in this figure are in ng. Bars: 0.5 mm. Numbers above the bars of histograms correspond to p-values. White arrows point to the domain where expression of either myod1 or myf5 is altered.

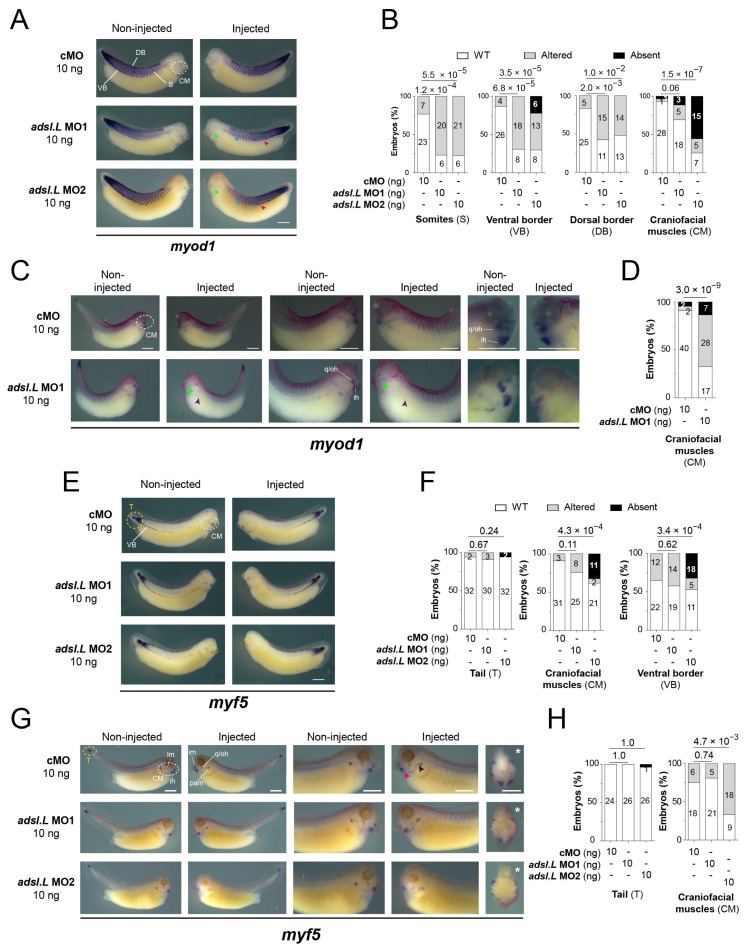

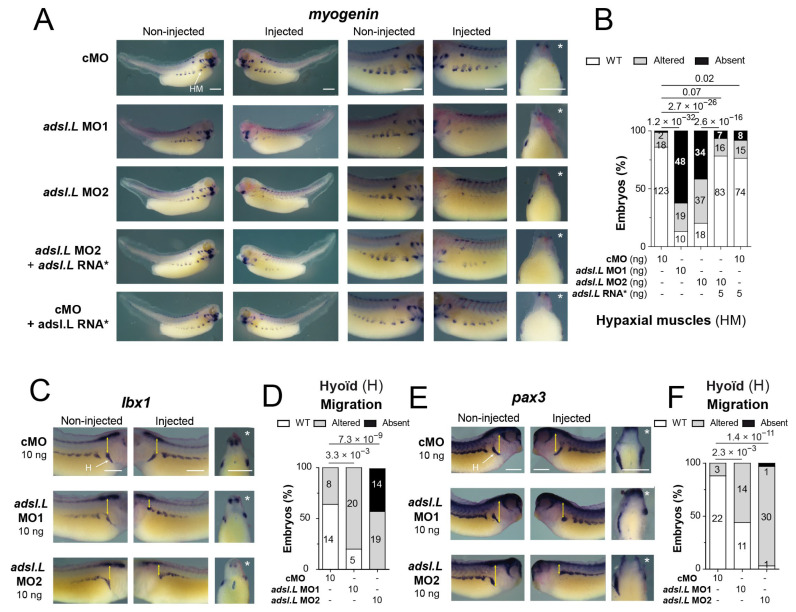

To further analyze the effects of adsl.L knockdown on MRF expression, myod1 and myf5 expression was then analyzed at later developmental stages (Figure 6). At the tailbud stage, the myod1 expression in the somites was found to be markedly altered in the adsl.L MO1 and MO2 morphants. As observed with the 12-101 staining, myotomes were shortened along the dorsoventral axis and somite shape defects and even a loss of the chevron v-shape of the most anterior somites were observed (blue arrowheads, Figure 6A,B). myod1 expression in the ventral border of the dermomyotome was also markedly reduced or lost (red arrowheads, Figure 6A,B), while its expression in the dermomyotome dorsal border was less altered in the anterior trunk region. The expression of myod1 in craniofacial muscles was also reduced or even absent following adsl.L MO1 or MO2 injection (green arrowheads, Figure 6A,B). These alterations in craniofacial muscles were also observed at the tadpole stages, with a severe significant reduction in myod1 expression, especially in the interhyoideus (ih), quadrato-hyoangularis and orbitohyoideus anlagen (q/oh) in adsl.L MO1 and MO2 morphants (light green arrowheads, Figure 6C,D). The expression of myf5 was also noticeably altered in craniofacial muscles at both the tailbud and tadpole stages (Figure 6E–H), even if these alterations were milder than the myod1 ones. Indeed, myf5 expression in adsl.L morphants was reduced or absent at both stages in the dorsal region of the pharyngeal arch muscle anlagen (black arrowhead, Figure 6G), whereas its expression in the interhyoideus and the intermandibularis muscle anlagen was rarely reduced (pink arrowhead, Figure 6G). However, no alteration in myf5 expression was observed in the undifferentiated presomitic mesoderm in the tail region (yellow circles, Figure 6E–H). The implication of adsl.L in the formation of the cranial muscles was also confirmed by analyzing the expression of myogenin (myog) following adsl.L MO1 and MO2 injection at stage 39 (Figure 7A and Figure S16). A strong reduction or even an absence of myogenin staining in the pharyngeal arch muscle anlagen was observed on the injected side in adsl.L morphants, whereas its expression in the interhyoideus and intermandibularis muscle anlagen was, however, less affected. These results are consistent with those observed via 12-101 immunolabelling on adsl.L morphants (Figure S9, blue arrowhead). Altogether, these data show that adsl.L is required for myod1, myf5 and myogenin expression during the second wave of myogenesis.

Figure 6.

Knockdown of adsl.L gene caused an impaired expression of myod1 and myf5 at late tailbud and tadpole embryonic stages, leading to somites and craniofacial muscle formation defects. (A–D) Representative images of the adsl.L-dependent altered expression of myod1 (A) and myf5 (C) domains in either somite (S), dorsal somite border (DB), ventral somite border (VB) or craniofacial muscles (CM), as revealed via in situ hybridization in late tailbud embryos. Blue, red, green and purple arrowheads point to myod1 altered expression in somites, ventral border, craniofacial muscles and hypaxial muscles, respectively. (E,G) Representative images of the adsl.L-dependent altered expression of myod1 (E) and myf5 (G) domains in the unsegmented mesoderm in the most posterior tail (T), somites (S), ventral somite border (VB) and craniofacial muscles (CM) in tadpole embryos. Black and pink arrowheads point to myf5 altered expression in pharyngeal arch muscle enlagen intermandibularis muscle enlagen respectively. (B,D,F,H) Quantification and statistics of the myod1 and myf5 expression phenotypes presented in (A,C,E,G), respectively. Craniofacial muscles: ih, interhyoïedus anlage; im, intermandibularis anlage; lm, levatores mandibulae anlage; pam, pharyngeal archmuscle anlagen; q/oh, common orbitohyoïdeus and quadrato-hyoangularis precursors. Injected side is indicated by asterisks. Bars: 0.5 mm. Numbers above the bars of histograms correspond to p-values.

Figure 7.

The adsl.L gene is required for hypaxial muscle migration. (A,B) The hypaxial muscle defect associated with adsl.L knockdown was rescued by the MO non-targeted adsl.L RNA*. Representative images (A) and quantifications (number in bars) and statistics (B) of the adsl.L-dependent alteration of myogenin gene expression monitored via in situ hybridization. (C–F) Migration of myoblasts in the hyoid region was found to be severely affected in adsl.L morphants, as shown by lbx1 (C,D) and pax3 (E,F) gene expression pattern alterations. Injected side is indicated by asterisks. Bars: 0.5 mm. HM and H stand for hypaxial muscles and hyoid region, respectively. Numbers above the bars of histograms correspond to p-values.

3.5. The adsl.L Gene Was Required for Hypaxial Muscle Formation and Migration

In addition to the somite and craniofacial muscle phenotypes, severe hypaxial muscle alterations were observed in adsl.L morphants (Figure 3 and Figure S9). To further characterize these defects, the expression of myogenin was analyzed via in situ hybridization at the late tadpole stage. adsl.L knockdown resulted in either a strong decrease or even an absence of myog expression in hypaxial muscle cells, while no significant alteration was observed in the embryos injected with the control morpholino (cMO) in combination or not with the adsl.L mutated RNA* (Figure 7A,B). This muscle phenotype was rescued by the injection of the adsl.L mutated RNA* in adsl.L MO2 morphants. These myogenin expression alterations were confirmed, as the myod1 expression was strongly reduced or absent in hypaxial muscles in adsl.L morphants (purple arrowheads, Figure 6C and Figure S17). These results confirm the role of the adsl.L gene in the expression of myogenic regulatory factors required for correct hypaxial muscle development. In addition, hypaxial muscles were also found to be highly reduced or absent, as revealed via 12-101 immunolabelling in ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L morphants (pink arrowheads, Figures S10 and S11). Interestingly, hypaxial muscle defects were also observed in tcf15 knockout mice [50], which is a gene whose expression is altered in purine X. laevis morphants (Figure 4A).

To better understand the deleterious effect of adsl.L knockdown on hypaxial muscles, expression of the pax3 and lbx1 genes encoding transcription factors were analyzed at different tadpole stages. Lbx1 and pax3 were both expressed in hypaxial body wall undifferentiated cells that form the front of hypaxial myoblast migration [37,51]. Although the injection of adsl.L MOs, especially adsl.L MO2, induced a slight reduction in lbx1 expression in the hypaxial muscle precursors, the major observed phenotype was a migration alteration of these lbx1 positive cells (Figure 7C,D). Indeed, muscle progenitors were closer to the ventral border of the somites. This alteration was more pronounced in the most anterior region (trunk I), in which progenitors migrated around the hyoid region (see yellow double arrows in Figure 7C). Similar alterations were observed for pax3 positive hypaxial body wall progenitors, which were characterized by a severe alteration of hypaxial progenitor migration, while the pax3 expression was less or not affected in the hypaxial myotome (Figure 7E,F). Altogether, these results show that purine biosynthesis genes are essential during hypaxial muscle formation in X. laevis.

4. Discussion

4.1. X. laevis as a Vertebrate Model to Study Purine-Deficiency-Related Pathologies

In this study, we functionally characterized the main members of the purine biosynthesis and salvage pathways in the vertebrate X. laevis for the first time. We also established the comparative map of their embryonic spatiotemporal expression and showed that the main common expression of purine genes was in the neuromuscular tissue and its precursors. This expression profile could be directly linked to the neuromuscular symptoms usually observed in most of the nearly thirty identified purine-associated pathologies [3,4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, we investigated the embryonic roles of three purine biosynthesis enzymes during vertebrate muscle development, focusing on the Adsl.L enzyme. As ADSL deficiency in humans is associated with residual enzymatic activity (reviewed in [6,52]), we believe that our experimental strategy based on the knockdown with morpholino-oligonucleotides is more appropriate in identifying the molecular dysfunctions found in patients rather than strategies based on knockout experiments. Altogether, our data show that X. laevis is a relevant model for studying the molecular bases of the developmental alterations associated with purine deficiencies.

4.2. Role of Purine Pathway Genes during X. laevis Development

Maternal and zygotic expression are key indicators of potential pathway involvement during vertebrate development. We show that the early stages of X. laevis embryo development are dependent on both purine pathways, as all the genes studied, except for adss1.L and adss1.S, are maternal genes and are expressed from gastrula stages. However, from the early organogenesis phase (stage 22), all 17 tested genes were expressed. We previously showed that the unique reserve of purine in embryos, namely, hypoxanthine, is depleted at stage 22 [48], and thus, this embryonic stage is placed as a key turning point of the purine source for the embryo. From this stage onward and until stage 45 (the stage where embryos start to feed), purines can only be synthesized de novo or recycled within the embryo, and the zygotic expression of purine biosynthesis genes then becomes crucial.

Furthermore, the genes of the purine de novo and salvage pathways share simultaneous embryonic expression and mostly in the same tissues, strongly suggesting that neither pathway is preferred for purine supply during X. laevis development. Our functional experiments also demonstrated that both pathways were involved in development since the muscle alterations observed in adsl.L morphants were also observed in ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L morphants. This is different from what was obtained in C. elegans, in which muscle phenotypes associated with ADSL deficiency are rather dependent on the purine recycling pathway [27].

In addition, we showed that adsl.L plays an early and essential role in myogenesis during the first and second myogenic wave, and its knockdown is associated with strong alterations in the primary myotome, somitomeres and anterior somite formation and the subsequent malformation of hypaxial and craniofacial muscles. Embryonic neuromuscular defects were previously described in other animal models [26,27], with a strong alteration in muscle integrity observed in C. elegans adsl knockout mutants. These studies raised the question of whether the observed phenotypes were the result of a decrease in one or more end products of the purine biosynthetic pathways, or that of an accumulation of Adsl.L substrates or their derivatives. Indeed, the neurodevelopmental alterations observed in zebrafish adsl mutants were associated with the accumulation of SAICAr, which is the dephosphorylated form of Adsl substrate in the de novo pathway (SAICAR or SZMP), and thus, these neuronal alterations were rescued via inhibition of this pathway [26]. In X. laevis, as the alterations in myogenesis are very similar in the adsl.L, ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L morphants, it seems very unlikely that the muscle phenotypes were related to an accumulation of Adsl.L substrates or their derivatives (Figure 1A). A metabolic rescue of the phenotypes is, therefore, an appropriate strategy to determine whether the muscle phenotypes could be related to a decrease in Adsl.L products and/or downstream metabolites. Hypoxanthine, which is the main source of purine in X. laevis embryo [48], would have been the best candidate metabolite for the MO rescue, but it could not be tested here since its metabolization requires the enzymatic activity of Adsl.L (Figure 1A). Rescue experiments were therefore carried out by adding adenine to the adsl.L morphant culture medium in concentrations at which this purine precursor was soluble in the medium (50 µM) but without any success. We cannot rule out that this may be due to the incapacity of this purine to cross the vitelline membrane. However, rescue experiments via adenine injection into the blastocoel or archenteron, as previously performed for other purine [32,53], are not possible because of adenine’s low solubility in aqueous solutions (<few µM).

Overall, these results strongly suggest that the observed muscle phenotypes are associated with purine deficiency, regardless of the mode of biosynthesis of these purines since disruption of the de novo pathway (ppat.L/ppat.S MO), the recycling pathway (hprt1.L MO) or both (adsl.L MO) results in similar alterations in myogenesis. However, these alterations may explain the muscle symptoms, such as axial hypotonia, peripheral hypotonia and muscle wasting observed in patients [14,17,18].

4.3. Muscle Defects Associated with Purine Pathways Dysfunction Were Related to Altered Expressions of MRF Genes

Our study provides new in vivo evidence for the identification of altered molecular mechanisms during purine deficiency. Indeed, we show that functional purine pathways were required for the expression of the myogenic regulator factors Myod1, Myf5 and Myogenin, which are by far the master regulatory transcription factors of the embryonic myogenic program, including myotome and somite formation and hypaxial and craniofacial myogenesis [36,49]. The adsl.L-specific alteration of myod1 and myf5 expression in the ventral border of the dermomyotome could, therefore, be at the origin of the deleterious effects observed in morphants on hypaxial progenitors and differentiated hypaxial muscle cells. A strong decrease in MRF expression was observed in the adsl.L morphants from the earliest stages of muscle formation in the neurula embryos. As MRF genes regulate the expression of other MRFs and/or their own expression, it is possible that one (or more) key purine derivative(s) could regulate the transcription expression and/or the function of one of the MRFs. Interestingly, the opposite phenotypes were obtained for myod1 expression in adsl.L morphants and in embryos overexpressing this gene, placing adsl.L as a key regulator of myod1 expression during development. Since Myod1 is a potent inducer of muscle differentiation and is required for myf5 expression in early X. laevis development, correct anterior somite segmentation [54] and correct myotome size [35], it is, therefore, possible that the muscle defects in adsl.L morphants were mainly due to a deregulation of myod1 expression, thus placing this gene, and the purine biosynthetic pathways, at the top of the myogenic gene cascade. An interesting future point of investigation would be to test whether myod1 expression is able to rescue adsl.L morphant muscle phenotypes.

So far, we have not found a direct or indirect link between purines and the transcriptional regulation of MRFs. However, regulation of transcription factor activity via direct binding of purine metabolites has already been demonstrated in different organisms [8,55]. In yeast, we have shown that the direct binding of purine metabolites (SZMP and ZMP, Figure 1) on Pho4 and Pho2 transcription factors was responsible for their activation [8]. These two metabolites of the de novo purine pathway were certainly not those implicated here, as similar muscle phenotypes were obtained in adsl.L, ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L morphants, but we can speculate that another purine derivative could similarly be involved in modulating the transcriptional expression of MRFs during X. laevis myogenesis. Moreover, regulation of myogenin gene expression by metabolites (CMP and UMP) was recently observed in the mouse C2C12 cell line [56], showing that MRF expression can be modulated by nucleotides. To our knowledge, a similar direct regulation of MRFs by purines has not been described to date. If it exists, as suggested by our data, then the mechanism by which it acts remains to be established.

It may be possible that the effect of purines on MRF expressions is indirect via upstream cascades, responding to purines and regulating the expression of these genes. Indeed, many upstream signals, for example, Wnt and FGF, regulate the expression of MRFs in myogenesis (reviewed in [57]). These pathways involve the activation of protein kinases of the myogenic kinome, whose activity is highly dependent on intracellular pools of purine nucleotides [58]. In particular, the activity of protein kinase A, which is initiated by the activation of heteromeric G proteins and adenylate cyclase through the Wnt pathway, is required for the expression of myod1 and myf5 and the formation of myoblasts. In addition, extracellular triphosphate purine nucleotides are ligands of purinergic receptors that are involved in myoblast proliferation and differentiation [59,60]. We recently showed that the ATP-dependent P2X5 receptor subunit is specifically expressed in X. laevis somites, which is in agreement with its expression profile described in other animal models [61,62]. We may hypothesize that adsl.L knockdown may reduce the availability of extracellular purines, leading to a possible alteration in P2X5 activation and myogenesis impairment [62]. This hypothesis will be tested in the near future in the laboratory. We previously showed that purinergic signaling controls vertebrate eye development by acting on the expression of the PSED (pax/six/eya/dach) network genes [29]. As this PSED gene network regulates MRF expression [63], it may also be possible that a similar mechanism is involved in adsl.L morphants. Interestingly, our observed muscle phenotypes are highly similar to those induced by retinoic acid receptor β2 (RARβ2) loss of function, i.e., a rostral shift of presomitic markers, defects in somite morphology, chevron-shaped somites and hypaxial muscle formation [64]. Retinoic acid pathway, through the activation of RAR, regulates myogenic differentiation and MRF gene expression [65]. It was reported that retinoic acid affects the synthesis of PRPP in human erythrocytes in psoriasis [66] and RA deficiency interferes with the expression of genes involved in the purine metabolism pathway in vivo [67]. These data, along with ours, suggest a possible link between purine biosynthetic pathway, retinoic acid signaling pathway and MRF gene expression, which is worthy of further investigation in the future.

In conclusion, the establishment of this new animal model allowed us to demonstrate the critical functions of the purine biosynthetic pathways during vertebrate embryogenesis. Indeed, our results provide evidence for the roles of purine pathway genes in myogenesis through the regulation of MRF gene expression during embryogenesis. Although the first median and lateral myogenesis disappeared during evolution, the second myogenic wave is conserved [49]. We can, therefore, speculate that the involvement of the de novo and salvage purine pathways during this myogenic wave is conserved in mammals and that purines may, therefore, be key regulators in the formation of hypaxial myogenic cells, i.e., the progenitors of the abdominal, spinal, and limb muscles, those muscles which are affected in patients with purine-associated pathologies [4,5,7,52]. Although in this work, we mostly focused on muscle alterations, it provides the basis for further functional studies to identify the molecular mechanisms involved in the development of neuromuscular tissues, those tissues in which the alterations underlie the major deleterious symptoms of patients with purine deficiency.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks C. Blanchard, A. Martinez and A. Tocco for their technical help; D. Patterson for a generous gift of the pADSLpCR3.1 plasmid used to clone the human ADSL-pCS2+ plasmid for the rescue experiments; C. Chanoine and B. Della Gaspera for a generous gift of the plasmids used for mespa, myogenin and tcf15 in situ hybridization probes; J. E. Gomes for critical reading of the manuscript; and K. Chiimba and S. Sanghera for English proofreading.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cells12192379/s1, Figure S1: Conservation of purine biosynthesis pathways between the yeast S. cerevisiae and X. laevis; Figure S2: Sequence comparison between the H. sapiens (Hs) and X. laevis (Xl) adenylosuccinate lyase enzymes; Figure S3: Validation of the morpholinos translation interference by in vitro translation; Figure S4: Functional complementation of yeast purine de novo pathway mutants by the X. laevis ortholog genes; Figure S5: Functional complementation of yeast purine salvage knocked-out mutants by the X. laevis ortholog genes; Figure S6: Temporal expression profiles of purine pathway genes during embryogenesis; Figure S7: The expression profile was determined for each gene by in situ hybridization (ISH) using antisense probes; Figure S8: In situ hybridization using control sense probes; Figure S9: Severity of adsl.L knock-down-associated phenotypes is morpholino dose-dependent; Figure S10: The ppat.L and ppat.S genes are required for somites and hypaxial muscle formation in X. laevis; Figure S11: The hprt1.L gene is required for somitogenesis and hypaxial muscle formation in X. laevis; Figure S12: The ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L genes are required for expression of the tcf15 gene; Figure S13: The ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L genes are required for expression of the mespa gene; Figure S14: Effect of H. sapiens ADSL and X. laevis adsl.L RNA* on myod1 expression at stage 12.5; Figure S15: Expression of the myogenic regulatory factor myod1 gene in the paraxial mesoderm is strongly affected by knock-down of ppat.L/ppat.S and hprt1.L genes; Figure S16: Statistical analysis of the effects associated with adsl.L knock-down on myogenin expression in craniofacial muscles in late tailbud stage embryos; Figure S17: Statistical analysis of the effects consecutive to adsl.L knock-down on myod1 expression in hypaxial muscles in late tailbud stage embryos; Table S1: Yeast strains; Table S2: Plasmids used for functional complementation in yeast; Table S3: Plasmids used for mRNA synthesis; Table S4: Ribonucleotides probes used for in situ hybridization; Table S5: Oligonucleotides used for RT-PCR analyses; Table S6: Comparison of the purine biosynthesis pathways encoding genes and proteins between, X. laevis, H. sapiens and X. tropicalis; Table S7: Comparison of the purine biosynthesis pathways encoding genes and proteins between X. laevis and S. cerevisiae.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P. and K.M.; methodology, B.P., C.S.-M., E.H., F.H., K.M. and M.D.; formal analysis, B.P., K.M. and M.D.; investigation, B.P., C.S.-M., E.H., F.H., K.M. and M.D.; resources, B.D.-F., B.P., C.S.-M., E.B.-G., E.H., F.H., K.M. and M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P. and K.M.; supervision, B.P. and K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures, which were performed in the Aquatic facility of the Centre Broca-Nouvelle Aquitaine in Bordeaux EU0655, complied with the official European guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Directive 2010/63/EU) and were approved by the Bordeaux Ethics Committee (CEEA50) and the French Min-istry of Agriculture (agreement #A33 063 942, approved 27 July 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by recurrent funding from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), and from PEPS/IDEX CNRS/Bordeaux University 2014 and the “Association Retina France” grant 2014 to B.P.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Daignan-Fornier B., Pinson B. Yeast to Study Human Purine Metabolism Diseases. Cells. 2019;8:67. doi: 10.3390/cells8010067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massé K., Dale N. Purines as Potential Morphogens during Embryonic Development. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:503–521. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9290-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simmonds H.A., Duley J.A., Fairbanks L.D., McBride M.B. When to Investigate for Purine and Pyrimidine Disorders. Introduction and Review of Clinical and Laboratory Indications. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1997;20:214–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1005308923168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramaniam S., Duley J.A., Christodoulou J. Inborn Errors of Purine Metabolism: Clinical Update and Therapies. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014;37:669–686. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurecka A. Inborn Errors of Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2009;32:247–263. doi: 10.1007/s10545-009-1094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyhan W.L. Disorders of Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Berghe G., Vincent M.-F., Marie S. Disorders of Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism. In: Fernandes J., Saudubray J.-M., van den Berghe G., Walter J.H., editors. Inborn Metabolic Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2006. pp. 433–449. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinson B., Vaur S., Sagot I., Coulpier F., Lemoine S., Daignan-Fornier B. Metabolic Intermediates Selectively Stimulate Transcription Factor Interaction and Modulate Phosphate and Purine Pathways. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1399–1407. doi: 10.1101/gad.521809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaeken J., Van den Berghe G. An Infantile Autistic Syndrome Characterised by the Presence of Succinylpurines in Body Fluids. Lancet. 1984;2:1058–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone R.L., Aimi J., Barshop B.A., Jaeken J., Van den Berghe G., Zalkin H., Dixon J.E. A Mutation in Adenylosuccinate Lyase Associated with Mental Retardation and Autistic Features. Nat. Genet. 1992;1:59–63. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao X., Li K., Tang B., Luo Y., Ding D., Zhao Y., Wang C., Zhou X., Liu Z., Zhang Y., et al. Novel Mutations in ADSL for Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency Identified by the Combination of Trio-WES and Constantly Updated Guidelines. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1625. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01637-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Bergh F., Vincent M.F., Jaeken J., Van den Berghe G. Residual Adenylosuccinase Activities in Fibroblasts of Adenylosuccinase-Deficient Children: Parallel Deficiency with Adenylosuccinate and Succinyl-AICAR in Profoundly Retarded Patients and Non-Parallel Deficiency in a Mildly Retarded Girl. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1993;16:415–424. doi: 10.1007/BF00710291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kmoch S., Hartmannová H., Stibůrková B., Krijt J., Zikánová M., Sebesta I. Human Adenylosuccinate Lyase (ADSL), Cloning and Characterization of Full-Length cDNA and Its Isoform, Gene Structure and Molecular Basis for ADSL Deficiency in Six Patients. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1501–1513. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.10.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mouchegh K., Zikánová M., Hoffmann G.F., Kretzschmar B., Kühn T., Mildenberger E., Stoltenburg-Didinger G., Krijt J., Dvoráková L., Honzík T., et al. Lethal Fetal and Early Neonatal Presentation of Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency: Observation of 6 Patients in 4 Families. J. Pediatr. 2007;150:57–61.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurecka A., Zikanova M., Tylki-Szymanska A., Krijt J., Bogdanska A., Gradowska W., Mullerova K., Sykut-Cegielska J., Kmoch S., Pronicka E. Clinical, Biochemical and Molecular Findings in Seven Polish Patients with Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;94:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zikanova M., Skopova V., Hnizda A., Krijt J., Kmoch S. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of 14 Mutant Adsl Enzyme Complexes and Correlation to Phenotypic Heterogeneity of Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:445–455. doi: 10.1002/humu.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegel E.K., Colman R.F., Patterson D. Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2006;89:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gitiaux C., Ceballos-Picot I., Marie S., Valayannopoulos V., Rio M., Verrieres S., Benoist J.F., Vincent M.F., Desguerre I., Bahi-Buisson N. Misleading Behavioural Phenotype with Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG. 2009;17:133–136. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurecka A., Zikanova M., Kmoch S., Tylki-Szymańska A. Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2015;38:231–242. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9755-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marie S., Race V., Vincent M.F., Van den Berghe G. Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency: From the Clinics to Molecular Biology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000;486:79–82. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46843-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Race V., Marie S., Vincent M.F., van den Berghe G. Clinical, Biochemical and Molecular Genetic Correlations in Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2159–2165. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.14.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mastrogiorgio G., Macchiaiolo M., Buonuomo P.S., Bellacchio E., Bordi M., Vecchio D., Brown K.P., Watson N.K., Contardi B., Cecconi F., et al. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of Patients with Adenylosuccinate Lyase Deficiency. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021;16:112. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01731-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keller K.E., Tan I.S., Lee Y.-S. SAICAR Stimulates Pyruvate Kinase Isoform M2 and Promotes Cancer Cell Survival in Glucose-Limited Conditions. Science. 2012;338:1069–1072. doi: 10.1126/science.1224409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gooding J.R., Jensen M.V., Dai X., Wenner B.R., Lu D., Arumugam R., Ferdaoussi M., MacDonald P.E., Newgard C.B. Adenylosuccinate Is an Insulin Secretagogue Derived from Glucose-Induced Purine Metabolism. Cell Rep. 2015;13:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzarino R.C., Baresova V., Zikánová M., Duval N., Wilkinson T.G., Patterson D., Vacano G.N. The CRISPR-Cas9 crADSL HeLa Transcriptome: A First Step in Establishing a Model for ADSL Deficiency and SAICAR Accumulation. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2019;21:100512. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dutto I., Gerhards J., Herrera A., Souckova O., Škopová V., Smak J.A., Junza A., Yanes O., Boeckx C., Burkhalter M.D., et al. Pathway-Specific Effects of ADSL Deficiency on Neurodevelopment. eLife. 2022;11:e70518. doi: 10.7554/eLife.70518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsac R., Pinson B., Saint-Marc C., Olmedo M., Artal-Sanz M., Daignan-Fornier B., Gomes J.-E. Purine Homeostasis Is Necessary for Developmental Timing, Germline Maintenance and Muscle Integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2019;211:1297–1313. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sater A.K., Moody S.A. Using Xenopus to Understand Human Disease and Developmental Disorders. Genesis. 2017;55 doi: 10.1002/dvg.22997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blum M., Ott T. Xenopus: An Undervalued Model Organism to Study and Model Human Genetic Disease. Cells Tissues Organs. 2018;205:303–313. doi: 10.1159/000490898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garí E., Piedrafita L., Aldea M., Herrero E. A Set of Vectors with a Tetracycline-Regulatable Promoter System for Modulated Gene Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast Chichester Engl. 1997;13:837–848. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199707)13:9<837::AID-YEA145>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nieuwkoop P.D., Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus Laevis (Daudin): A Systematical and Chronological Survey of the Development from the Fertilized Egg Till the End of Metamorphosis. Garland Pub.; Spokane, WA, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massé K., Bhamra S., Eason R., Dale N., Jones E.A. Purine-Mediated Signalling Triggers Eye Development. Nature. 2007;449:1058–1062. doi: 10.1038/nature06189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanchard C., Boué-Grabot E., Massé K. Comparative Embryonic Spatio-Temporal Expression Profile Map of the Xenopus P2X Receptor Family. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019;13:340. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massé K., Eason R., Bhamra S., Dale N., Jones E.A. Comparative Genomic and Expression Analysis of the Conserved NTPDase Gene Family in Xenopus. Genomics. 2006;87:366–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Della Gaspera B., Armand A.-S., Lecolle S., Charbonnier F., Chanoine C. Mef2d Acts Upstream of Muscle Identity Genes and Couples Lateral Myogenesis to Dermomyotome Formation in Xenopus laevis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Della Gaspera B., Armand A.-S., Sequeira I., Chesneau A., Mazabraud A., Lécolle S., Charbonnier F., Chanoine C. Myogenic Waves and Myogenic Programs during Xenopus Embryonic Myogenesis. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2012;241:995–1007. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin B.L., Harland R.M. A Novel Role for Lbx1 in Xenopus Hypaxial Myogenesis. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2006;133:195–208. doi: 10.1242/dev.02183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kintner C.R., Brockes J.P. Monoclonal Antibodies Identify Blastemal Cells Derived from Dedifferentiating Limb Regeneration. Nature. 1984;308:67–69. doi: 10.1038/308067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massé K., Bhamra S., Allsop G., Dale N., Jones E.A. Ectophosphodiesterase/Nucleotide Phosphohydrolase (Enpp) Nucleotidases: Cloning, Conservation and Developmental Restriction. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010;54:181–193. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.092879km. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bassez T., Paris J., Omilli F., Dorel C., Osborne H.B. Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Ornithine Decarboxylase in Xenopus Laevis Oocytes. Dev. Camb. Engl. 1990;110:955–962. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.3.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowes J.B., Snyder K.A., Segerdell E., Gibb R., Jarabek C., Noumen E., Pollet N., Vize P.D. Xenbase: A Xenopus Biology and Genomics Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D761–D767. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karpinka J.B., Fortriede J.D., Burns K.A., James-Zorn C., Ponferrada V.G., Lee J., Karimi K., Zorn A.M., Vize P.D. Xenbase, the Xenopus Model Organism Database; New Virtualized System, Data Types and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D756–D763. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Session A.M., Uno Y., Kwon T., Chapman J.A., Toyoda A., Takahashi S., Fukui A., Hikosaka A., Suzuki A., Kondo M., et al. Genome Evolution in the Allotetraploid Frog Xenopus laevis. Nature. 2016;538:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature19840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ljungdahl P.O., Daignan-Fornier B. Regulation of Amino Acid, Nucleotide, and Phosphate Metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:885–929. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.133306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kragtorp K.A., Miller J.R. Integrin Alpha5 Is Required for Somite Rotation and Boundary Formation in Xenopus. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2007;236:2713–2720. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno T.A., Kintner C. Regulation of Segmental Patterning by Retinoic Acid Signaling during Xenopus Somitogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:205–218. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sparrow D.B., Jen W.C., Kotecha S., Towers N., Kintner C., Mohun T.J. Thylacine 1 Is Expressed Segmentally within the Paraxial Mesoderm of the Xenopus Embryo and Interacts with the Notch Pathway. Dev. Camb. Engl. 1998;125:2041–2051. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.11.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tocco A., Pinson B., Thiébaud P., Thézé N., Massé K. Comparative Genomic and Expression Analysis of the Adenosine Signaling Pathway Members in Xenopus. Purinergic Signal. 2015;11:59–77. doi: 10.1007/s11302-014-9431-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Della Gaspera B., Weill L., Chanoine C. Evolution of Somite Compartmentalization: A View From Xenopus. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;9:790847. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.790847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson-Rawls J., Hurt C.R., Parsons S.M., Rawls A. Differential Regulation of Epaxial and Hypaxial Muscle Development by Paraxis. Dev. Camb. Engl. 1999;126:5217–5229. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin B.L., Harland R.M. Hypaxial Muscle Migration during Primary Myogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Dev. Biol. 2001;239:270–280. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelley R.E., Andersson H.C. Disorders of Purines and Pyrimidines. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2014;120:827–838. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4087-0.00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iijima R., Kunieda T., Yamaguchi S., Kamigaki H., Fujii-Taira I., Sekimizu K., Kubo T., Natori S., Homma K.J. The Extracellular Adenosine Deaminase Growth Factor, ADGF/CECR1, Plays a Role in Xenopus Embryogenesis via the Adenosine/P1 Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:2255–2264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maguire R.J., Isaacs H.V., Pownall M.E. Early Transcriptional Targets of MyoD Link Myogenesis and Somitogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2012;371:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim P.B., Nelson J.W., Breaker R.R. An Ancient Riboswitch Class in Bacteria Regulates Purine Biosynthesis and One-Carbon Metabolism. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakagawara K., Takeuchi C., Ishige K. 5′-CMP and 5′-UMP Promote Myogenic Differentiation and Mitochondrial Biogenesis by Activating Myogenin and PGC-1α in a Mouse Myoblast C2C12 Cell Line. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2022;31:101309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2022.101309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabillo A., Ramirez J., Domingo C.R. Making Muscle: Morphogenetic Movements and Molecular Mechanisms of Myogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016;51:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knight J.D., Kothary R. The Myogenic Kinome: Protein Kinases Critical to Mammalian Skeletal Myogenesis. Skelet. Muscle. 2011;1:29. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burnstock G., Arnett T.R., Orriss I.R. Purinergic Signalling in the Musculoskeletal System. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9:541–572. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pietrangelo T., Guarnieri S., Fulle S., Fanò G., Mariggiò M.A. Signal Transduction Events Induced by Extracellular Guanosine 5′ Triphosphate in Excitable Cells. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:633–636. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer M.P., Gröschel-Stewart U., Robson T., Burnstock G. Expression of Two ATP-Gated Ion Channels, P2X5 and P2X6, in Developing Chick Skeletal Muscle. Dev. Dyn. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 1999;216:442–449. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199912)216:4/5<442::AID-DVDY12>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ryten M., Dunn P.M., Neary J.T., Burnstock G. ATP Regulates the Differentiation of Mammalian Skeletal Muscle by Activation of a P2X5 Receptor on Satellite Cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:345–355. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maire P., Dos Santos M., Madani R., Sakakibara I., Viaut C., Wurmser M. Myogenesis Control by SIX Transcriptional Complexes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;104:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Janesick A., Tang W., Nguyen T.T.L., Blumberg B. RARβ2 Is Required for Vertebrate Somitogenesis. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2017;144:1997–2008. doi: 10.1242/dev.144345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen J., Li Q. Implication of Retinoic Acid Receptor Selective Signaling in Myogenic Differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:18856. doi: 10.1038/srep18856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baló-Banga J.M., Leibinger J., Molnár L., Király K. The Effect of Retinoic Acid on the Synthesis of Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate in Human Erythrocytes in Psoriasis. A Preliminary Note. Dermatologica. 1978;157((Suppl. S1)):45–51. doi: 10.1159/000250884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paschaki M., Schneider C., Rhinn M., Thibault-Carpentier C., Dembélé D., Niederreither K., Dollé P. Transcriptomic Analysis of Murine Embryos Lacking Endogenous Retinoic Acid Signaling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.