Abstract

The emergence of Leishmania less sensitive to pentavalent antimonial agents (SbVs), the report of inhibition of purified topoisomerase I of Leishmania donovani by sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam), and the uncertain mechanism of action of antimonial drugs prompted an evaluation of SbVs in the stabilization of cleavable complexes in promastigotes of Leishmania (Viannia). The effect of camptothecin, an inhibitor of topoisomerase, and additive-free meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) on the stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes associated with the inhibition of topoisomerase was assessed in the human promonocytic cell line U-937, promastigotes of L. (Viannia) panamensis selected for SbV resistance in vitro, and the corresponding wild-type strain. The stabilization of cleavable complexes and the 50% effective dose (ED50) of SbVs for parasites isolated from patients with relapses were also evaluated. The median ED50 for the wild-type strain was 16.7 μg of SbV/ml, while that of the line selected for resistance was 209.5 μg of SbV/ml. Treatment with both meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate (20 to 200 μg of SbV/ml) stabilized DNA-protein complexes in the wild-type strain but not the resistant line. The ED50s of the SbVs for Leishmania strains from patients with relapses was comparable to those for the line selected for in vitro resistance, and DNA-protein complexes were not stabilized by exposure to meglumine antimoniate. Cleavable complexes were observed in all Leishmania strains treated with camptothecin. Camptothecin stabilized cleavable complexes in U-937 cells; SbVs did not. The selective effect of the SbVs on the stabilization of DNA-protein complexes in Leishmania and the loss of this effect in naturally resistant or experimentally derived SbV-resistant Leishmania suggest that topoisomerase may be a target of antimonial drugs.

The clinical response of American dermal leishmaniasis to treatment with pentavalent antimonial drugs (SbVs) is variable (10, 16). Host factors such as the localization and chronicity of the lesion(s) (16, 22), underlying illness or concomitant infection, and acquired resistance (12) influence the rate of healing. Furthermore, the potency of the particular lot of antimonial drug and the sensitivities of the Leishmania strains have been shown to differ (3, 15) and could therefore contribute to the outcome of chemotherapy. The participation of multiple host, parasite, and drug factors in the response to treatment have confounded attempts to correlate the in vitro sensitivities of Leishmania isolates to SbVs with the clinical response.

A further constraint on the interpretation of sensitivity to SbVs in vitro and the clinical response is the lack of understanding of the modes of action of these drugs against Leishmania. Using topoisomerase I purified from Leishmania donovani, Chakraborty and Majumder (7) demonstrated that the SbV sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) inhibited the unwinding and cleavage of the supercoiled plasmid pBR322 and also stabilized covalent complexes of topoisomerase and DNA. Calf thymus topoisomerase I was not inhibited by sodium stibogluconate, nor was the DNA gyrase of Escherichia coli. Phosphofructokinase and enzymes involved in the synthesis of nucleotide triphosphates have also been shown to be inhibited in vitro by the SbVs meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) and sodium stibogluconate (2, 3). However, the capacity of SbVs to inhibit these enzymes in vivo and the relationship of any such inhibitory activity to the therapeutic effects of these drugs are unknown.

In order to define the role of parasite sensitivity to SbVs in treatment failure and to examine the mode of action of SbVs, we used a line of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis derived by in vitro selection for resistance to additive-free meglumine antimoniate and the corresponding wild-type strain, as well as paired strains from patients with documented reactivation following treatment and healing (20). In addition, a single lot of each of additive-free meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate were used, thereby controlling drug sources of variability. The in vitro sensitivities of naturally derived putative resistant strains and the stabilization of cleavable complexes in vivo in promastigotes treated with additive-free meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate were compared with those of the experimentally derived SbV-resistant line and the wild-type strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs.

Additive-free sodium stibogluconate (lot no. BL06916) and meglumine antimoniate (lot no. BL09186) were provided as powdered formulations by the Division of Experimental Therapeutics of the Walter Reed Army Institute, Washington, D.C. Each formulation had an SbV content of 25 to 26.2%, by weight. Stock solutions were prepared by dissolution in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.0), sterilized by filtration, and then stored at −20°C until used. Camptothecin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) at a concentration of 50 μM and was diluted in Schneider’s Drosophila medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) for in vivo assay of the inhibition of topoisomerase I.

Parasites.

L. (Viannia) panamensis MHOM/CO/86/1166 was isolated from a patient with cutaneous leishmaniasis prior to treatment, and the 50% effective dose (ED50) of meglumine antimoniate for the strain in vitro was low. The strain was selected for resistance in vitro by culture in the presence of increasing concentrations of additive-free meglumine antimoniate. In parallel, because ED50 determinations are dependent on robust growth, the original wild-type strain was cultured in Schneider’s Drosophila medium–10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Vecol, Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia) without meglumine antimoniate in order to ensure comparable adaptation of the sensitive and resistant lines to in vitro propagation. These wild-type and resistant populations provided reference standards for the in vitro evaluation of sensitivity to SbV. The Leishmania strains from patients with cases of documented reactivation and reinfection used to examine the relationship between the clinical response and in vitro sensitivity to SbV are listed in Table 1. Reactivation of disease was distinguished from reinfection on the basis of the identity (isoenzyme profile, karyotype, and restriction fragment length polymorphism profile) or nonidentity of the parasites isolated from the same individual during the first and subsequent episodes of disease, respectively (20).

TABLE 1.

L. (Viannia) panamensis strains isolated from patients with relapse and reinfection included in the investigation of sensitivity to SbVs

| Strain codea | Isoenzyme phenotype (zymodeme)b |

|---|---|

| Relapse (initial, recurrent isolates identical) | |

| M/HOM/CO/85/2407i | 2.4 |

| M/HOM/CO/85/2407r | 2.4 |

| M/HOM/CO/84/2238i | 2.4 |

| M/HOM/CO/84/2238r | 2.4 |

| M/HOM/CO/83/2025i | 2.4 |

| M/HOM/CO/83/2025r | 2.4 |

| Reinfections (initial, recurrent isolates disparate) | |

| M/HOM/CO/85/2485i and five clones | 2.3 |

| M/HOM/CO/85/2485r | 2.4 |

| M/HOM/CO/85/2309i | 2.3 |

| M/HOM/CO/85/2309r | 2.4 |

i, strain isolated from initial lesion; r, strain isolated from recurrent lesion.

Data are from Saravia et al. (21).

Determination of ED50.

Promastigotes of Leishmania strains were propagated in Senekjie’s medium at 25°C. Logarithmic-phase organisms were harvested at 72 h of culture and were washed twice with PBS by centrifugation at 1,600 × g at room temperature. Parasites were suspended at 106/ml in Schneider’s medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and meglumine antimoniate at SbV concentrations from 5.5 to 680 μg/ml and were cultured in 24-well sterile disposable plates (Falcon; Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, N.J.) at 25°C. Assays were performed in triplicate. One milliliter of culture medium containing the corresponding concentration of SbV was added at 48 h. Promastigotes cultured at the same concentration in the absence of drug served as controls. At 96 h in the presence of additive-free meglumine antimoniate, viable promastigotes were counted with a hemocytometer and the ED50 was calculated by probit analyses (1).

Determination of the effect of camptothecin and SbVs on the stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes associated with topoisomerase. (i) U-937 cells.

The effects of camptothecin and SbVs on the stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes associated with topoisomerase were evaluated by the method described for L. donovani by Bodley and Shapiro (4) on the basis of the stabilization of cleavable complexes of enzyme with DNA. The principle of this method is as follows. Topoisomerase breaks the DNA strands and binds covalently to DNA via a phosphotyrosine bond. This covalently bound complex of topoisomerase and DNA is reversible when enzymatic catalysis is completed. Inhibition of topoisomerase by camptothecin results when the DNA-topoisomerase complex is stabilized, preventing separation of the enzyme from the DNA and thereby impeding the catalytic activity. Camptothecin was used as a positive control for the stabilization of cleavable complexes in the histiocytic cell line U-937 (ATCC CRL-159302) and Leishmania. The solvent dimethyl sulfoxide at 100 μl/ml served as a negative control for camptothecin. U-937 cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL) containing either camptothecin at 50,100, or 200 μM/ml or the additive-free SbV meglumine antimoniate at a concentration of 100, 500, or 1,000 μg/ml, and the suspension was incubated for 30 min. Afterward, the cells were lysed by resuspension in 2.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Serva Feinbiochemica, Heidelberg, Germany) containing 10 mM EDTA (Sigma) and salmon DNA (Sigma) at a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml. The lysate was divided into two equal parts; one was treated with 1.7 mg of proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, GmBH, Mannheim, Germany) per ml for 1 h at 56°C and the other was untreated and was maintained at room temperature. Subsequently, the DNA was extracted with phenol (Sigma) and was concentrated with isopropanol (Fisher) and 3 M sodium acetate (pH 7.0; Sigma).

Phenol extraction of total DNA reveals a clear band at the phenol-aqueous interface in the untreated sample containing complexes of DNA-protein. Uncomplexed DNA is solubilized in the aqueous phase and protein is solubilized in the phenolic phase. The proteinase K-treated sample, in contrast, does not form a band at the phenol-aqueous interface since the protein bound to DNA has been destroyed by the proteinase K. Hence, more DNA is present in the aqueous phase of the proteinase K-treated sample than in the untreated sample when complexes have been stabilized. DNA was quantitated spectrophotometrically at 260 nm or was visualized in a 1.5% agarose gel following electrophoresis at 40 V for 8 h.

(ii) Leishmania.

Promastigotes were harvested in the logarithmic phase of growth, washed twice by centrifugation at 1,600 × g for 10 min at room temperature, and resuspended at a concentration of 108 parasites/ml in PBS. On the basis of the results of prior experiments, this concentration of parasites provided a clear distinction between positive and negative controls for the stabilization of cleavable complexes with camptothecin. Parasite suspensions were exposed to camptothecin at 50 μM/ml or additive-free meglumine antimoniate and/or sodium stibogluconate at concentrations ranging from 20 to 200 μg of SbV/ml and were processed as described above for U-937 cells.

RESULTS

ED50 of meglumine antimoniate for wild-type L. panamensis 1166 and SbV-resistant line selected in vitro and strains isolated from patients presenting with relapse or reinfection.

The ED50 for promastigotes of strain 1166 prior to in vitro selection with additive-free meglumine antimoniate was significantly lower than that for the same strain selected for resistance to SbVs in vitro (Table 2). The ED50s for strains isolated from the initial lesion of patients experiencing relapse following treatment were equal to or greater than 170 μg of SbV/ml. For two of three strains isolated from the lesions of patients at the time of relapse, ED50s were greater than 170 μg of SbV/ml and for the third the ED50 was 85.9 μg of SbV/ml. In contrast, for strains from patients who had experienced reinfections, ED50s were between 28 and 132 μg of SbV/ml (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

ED50 of additive-free meglumine antimoniate for wild-type strain 1166 and SbV-resistant line selected in vitro and strains isolated from patients presenting relapse or reinfectiona

| Expt no. | Strain | ED50 (μg of SbV/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Internal control | |

| 1166wt | 16.70 | |

| 1166SR | 140.22 | |

| Relapse | ||

| RE-2407i | >170.00 | |

| RE-2407r | 85.90 | |

| 2 | Internal control | |

| 1166wt | 39.50 | |

| 1166SR | 209.94 | |

| Relapse | ||

| RE-2025i | >170.00 | |

| RE-2025r | >680.00 | |

| RE-2238i | >170.00 | |

| RE-2238r | 170.00 | |

| 3 | Internal control | |

| 1166wt | 15.75 | |

| 1166SR | 209.50 | |

| Reinfection | ||

| RI-2309i | ND | |

| RI-2309r | 97.19 | |

| RI-2485i | 28.43 | |

| RI-2485r | 132.40 |

1166 wt, wild-type 1166; 1166SR, strain 1166 selected for SbV resistance; i, strain isolated from initial lesion; r, strain isolated from recurrent lesion; ND, not determined.

Effects of camptothecin and SbVs on the stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes. (i) U-937 cells.

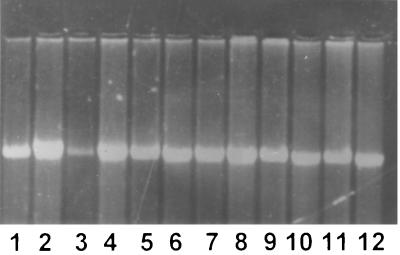

The stabilization of cleavable complexes associated with the inhibition of topoisomerase in eukaryotic cells treated with camptothecin was confirmed with the human histiocytic cell line U-937. Complexes were stabilized over doses of 50, 100, and 200 μM; however, visual resolution of DNA from cleavable complexes was greater with 50 μM camptothecin. In contrast to the results obtained with camptothecin, an SbV at doses as high as 1,000 μg/ml either as additive-free meglumine antimoniate or sodium stibogluconate failed to stabilize cleavable DNA-protein complexes in U-937 cells (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes in U-937 cells. Lanes: 1, dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μl) without proteinase K; 2, dimethyl sulfoxide (100 μl) plus proteinase K; 3, camptothecin (50 μM) without proteinase K; 4, camptothecin (50 μM) plus proteinase K; 5, meglumine antimoniate (100 μg of SbV/ml) without proteinase K; 6, meglumine antimoniate (100 μg of SbV/ml) plus proteinase K; 7, meglumine antimoniate (200 μg of SbV/ml) without proteinase K; 8, meglumine antimoniate (200 μg of SbV/ml) plus proteinase K; 9, sodium stibogluconate (100 μg of SbV/ml) without proteinase K; 10, sodium stibogluconate (100 μg of SbV/ml) plus proteinase K; 11, sodium stibogluconate (200 of μg SbV/ml) without proteinase K; 12, sodium stibogluconate (200 of μg SbV/ml) plus proteinase K.

(ii) Promastigotes of L. (Viannia) panamensis.

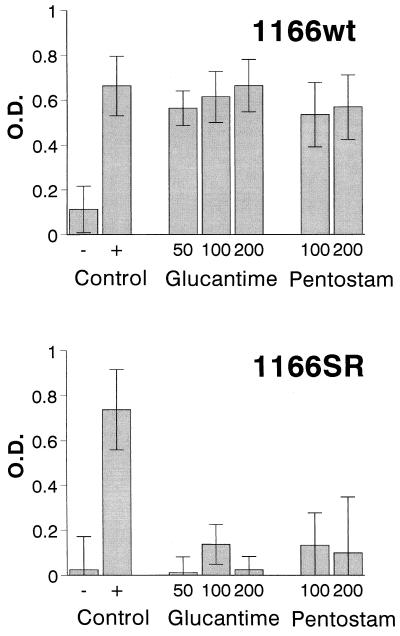

Cleavable complexes were stabilized in all strains of L. (Viannia) panamensis examined when promastigotes were treated with camptothecin. As in the case of U-937 cells, 50 μM was the optimal dose for camptothecin, and camptothecin was therefore used as a positive control for the stabilization of DNA-protein complexes. Treatment with an SbV either as additive-free meglumine antimoniate or sodium stibogluconate resulted in the stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes in the sensitive, wild-type strain 1166 at all concentrations tested (20, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg of SbV/ml) (Fig. 2). In contrast, the SbV-resistant line of strain 1166 did not yield cleavable complexes when it was treated with any of the concentrations of an SbV (Fig. 2). The differences in the mean optical density (OD) values and 95% confidence interval for proteinase K-treated and untreated samples of promastigotes of the wild-type and SbV-resistant line of strain 1166 when they were exposed to additive-free meglumine antimoniate were clearly disparate (Fig. 2). The mean difference in the ODs for proteinase K-treated and untreated samples of promastigotes of the sensitive wild-type line exposed to any dose of meglumine antimoniate fell within the confidence interval for the positive control for stabilization of cleavable complexes associated with topoisomerase inhibition (camptothecin), while the value obtained for promastigotes of the resistant line treated with any dose of meglumine antimoniate fell within the confidence interval for the negative control for complex stabilization (dimethyl sulfoxide). The confidence intervals for the wild-type and SbV-resistant lines of strain 1166, as well as the positive and negative controls for cleavable complex stabilization (camptothecin and dimethyl sulfoxide, respectively) provided the bases for defining the effect of SbVs on cleavable complex stabilization in strains from patients with relapses and reinfections.

FIG. 2.

Stabilization of DNA-protein complexes in promastigotes of the L. (Viannia) panamensis 1166 wild-type strain (1166wt) and SbV-resistant line (1166SR; resistant to 175 μg of SbV/ml) treated with camptothecin, meglumine antimoniate, (Glucantime) and sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam). The negative control was dimethyl sulfoxide; the positive control was camptothecin at 50 μM. Meglumine antimoniate was used at concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 μg/ml, and sodium stibogluconate was used at concentrations of 100 and 200 μg/ml. Bars indicate the average difference in OD between proteinase K-treated and untreated samples in eight independent experiments for meglumine antimoniate and three independent experiments for sodium stibogluconate.

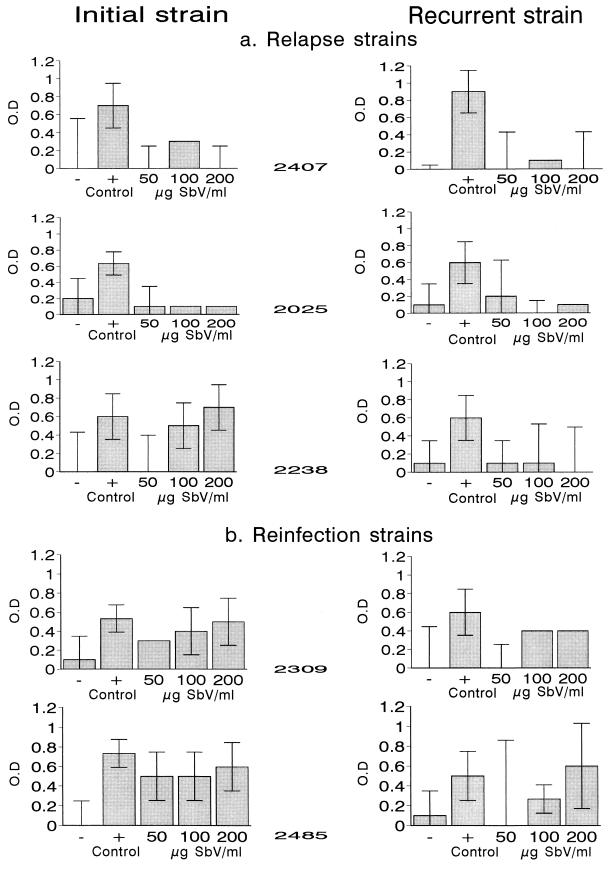

Strains from patients with documented cases of relapse or reinfection following treatment and complete healing demonstrated distinct patterns of sensitivity to SbV. Cleavable complex stabilization was not observed at any concentration of SbV evaluated with two of three paired strains (strains 2407 and 2025) from patients with relapses (Fig. 3). For the third pair of strains, (strain 2238), complexes were not stabilized by treatment with 50 μg of SbV/ml but were stabilized by treatment with 100 and 200 μg of SbV/ml for the strain isolated from the initial lesion. None of these doses of SbV resulted in the stabilization of cleavable complexes in the corresponding relapse strain (Fig. 3). Contrary to the results obtained with relapse strains, promastigotes of the strains initially isolated from patients with reinfections yielded complexes at all three concentrations of SbV. The strains isolated from recurrent lesions attributed to reinfection did not present DNA-protein complexes when they were treated with 50 μg of SbV/ml but did when they were treated with 100 and/or 200 μg of SbV/ml (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Stabilization of DNA-protein complexes in paired strains of L. (Viannia) panamensis treated with camptothecin and meglumine antimoniate. (a) Strains from patients with relapses; (b) strains from patients with reinfections. The negative control was dimethyl sulfoxide; the positive control was camptothecin at 50 μM. Bars indicate the average difference in OD between proteinase K-treated and untreated samples in three experiments. The difference in the OD within the confidence interval for the SbV-sensitive wild-type strain (1166WT; control value) is indicative of sensitivity to SbV. The difference in the OD within the confidence interval for the SbV-resistant line (1166SR) is indicative of resistance.

Relationship between ED50 and cleavable complex stabilization.

The median ED50 of an SbV for the wild-type strain used as an internal standard was 16.7 μg/ml, and cleavable complexes were stabilized by all concentrations of SbVs evaluated. The median ED50 of an SbV for the line of the same strain selected for resistance was 209.5 μg/ml, and none of the concentrations of an SbV resulted in complex stabilization. Among the strains isolated from patients with recurrent leishmaniasis (relapse or reinfection), the median ED50 for strains that presented cleavable complexes when they were treated with one or more concentrations of an SbV was 114.8 μg/ml. In contrast, the median ED50 for strains that did not present complexes when they were treated with any concentration of an SbV was greater than 170 μg of SbV/ml.

DISCUSSION

The relationship between response to treatment and the sensitivities of Leishmania strains to an SbV has been inferred from the results of studies of the in vitro sensitivities of strains isolated from patients whose treatment was unsuccessful (12, 15). However, uncertainty exists as to whether the in vitro sensitivity of parasites reflects the effectiveness of SbVs since factors such as patient compliance, the variable potencies of different lots of drug, and immunologic and nonimmunologic host factors are also determinants of the response to treatment and have not been controlled in the prior analyses.

In order to overcome the uncertainties inherent in the response to treatment and assessment of the sensitivity to SbVs in vitro, we introduced internal standards of in vitro sensitivity and resistance consisting of a line selected in vitro with additive-free meglumine antimoniate and the corresponding wild-type strain. An additive-free SbV was used to derive a resistant population in order to avoid the selection of populations that would develop resistance to other components of the formulation such as the preservative m-chlorocresol, which has been found to have greater leishmanicidal activity in vitro than SbVs and to be able to induce specific resistance (8, 18). Selection with increasing concentrations of an SbV yielded organisms for which the ED50 of additive-free meglumine antimoniate was increased. Besides the uncertain qualitative relationship between the in vitro and the in vivo response, the significance of a particular ED50 in vitro with respect to sensitivity in vivo is unknown. Time of exposure to an SbV in vitro is a critical determinant of the ED50. Hence, the inclusion of internal standards for bona fide resistance also provides a point of reference for interassay comparisons.

The use of strains from patients with relapses determined on the basis of prospective clinical observation together with biochemical characterization of the initial and relapse strains provided strains from patients with explicitly defined treatment failures. The consistent finding that the ED50s for the strains initially isolated from patients with relapses were all high in vitro when additive-free meglumine antimoniate was used supports the existence of primary resistance and the contributory role of the low level of sensitivity to SbVs of parasites from patients with relapses. Evidence for a spectrum of sensitivity to SbVs among Leishmania strains isolated from patients prior to treatment has been reported by Grogl et al. (12). We have also observed a wide range of ED50s of SbVs (5 to 680 μg of SbV/ml for strains isolated prior to treatment [19]). The diverse pattern of sensitivity to SbVs exhibited by the phenotypically and genotypically distinct paired strains from patients with reinfections provides further support for primary resistance among strains circulating in foci of endemicity. The frequency of some level of resistance among the strains from patients with recurrent disease suggests that the phenomenon may be common in areas of endemicity.

Whether a low level of sensitivity to SbVs is innate or is the result of selective pressure by treatment administered to other affected members of the community remains to be established. The general assumption that humans are not a source of infection to sandflies theoretically renders infection of humans a dead end; resistance resulting from inadequate treatment would not be propagated as in the case of malaria. However, subcurative treatment has been associated with diminished sensitivity to SbVs in vitro (11, 12). Moreover, the loss of cleavable complex stabilization in relapse strain 2238 when the promastigotes were exposed to an SbV is consistent with secondary resistance. Incomplete treatment of patients residing in areas of endemicity is common. In our experience, even with active follow-up, fewer than 50% of diagnosed patients complete the prescribed treatment (20 mg/kg of body weight/day for 20 days). Therefore, it is conceivable that persisting infections, as demonstrated for parasites responsible for relapses, involve parasites with low levels of sensitivity to SbVs. It is noteworthy that while the sylvatic reservoirs of the species of Leishmania (Viannia) remain an enigma, the prevalence of infection among adult residents in areas of endemicity can approximate 100% (23). If persistent infection is the rule rather than a rare exception, incompletely treated patients in foci of endemicity could constitute a growing source of Leishmania with low levels of sensitivity to SbVs.

Evidence that the SbV sodium stibogluconate inhibited purified topoisomerase I of L. donovani in vitro had been reported previously (7). The current findings of the stabilization of cleavable complexes in response to SbVs in vivo among promastigotes of L. (Viannia) panamensis that are sensitive to SbVs and the lack of such complexes in a line derived from the same strain by selection for resistance to SbVs provide compelling evidence that the sensitivity and resistance of Leishmania to SbVs in vivo is linked to effects on the stabilization of cleavable DNA-protein complexes. Such complexes involving covalently bound protein and DNA have been shown to correlate with inhibition of topoisomerase activity in mammalian cells, Leishmania, and trypanosomes treated with camptothecin (4, 14). The results are suggestive of topoisomerase inhibition; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that complexes involve another covalently bound protein.

The selectivity of the effect of SbVs on cleavable complex stabilization in Leishmania, whereas camptothecin stabilized cleavable complexes in both the human histiocytic cell line and Leishmania, is consistent with the favorable therapeutic index of SbVs. The extension of this observation to strains isolated from patients that clinically responded to treatment and the lack of complex stabilization in strains from patients that suffered relapses indicate that the relationship between the diminished sensitivity of Leishmania to SbVs and the loss of complex stabilization when the corresponding promastigotes were treated with SbVs in vitro is not restricted to artificially derived resistant populations of Leishmania.

The ED50 and the concentration of SbVs that resulted in DNA-protein complex stabilization were related: a low ED50 was associated with complex stabilization at low concentrations of SbV, while a higher ED50 was associated with the lack of complex stabilization at the lower concentration or all of the concentrations of SbV tested. A threshold ED50 that predicts clinical resistance could not be identified on the basis of the results of the experiments that we conducted. The inherent variability of ED50 on the basis of the inhibition of growth of populations whose growth is heterogeneous renders ED50 a relative indicator of drug sensitivity. The assay of DNA-protein complexes, on the other hand, may allow a threshold dose of an SbV indicative of clinical resistance to be established. Notably, even 30 min of exposure to 20 μg of SbV/ml (data not shown), a physiologically relevant concentration of an SbV, resulted in complex stabilization in the wild-type strain 1166. The short-term exposure to an SbV (30 min) in the cleavable complex assay did not kill the vast majority of promastigotes; viability was between 70 and 82% for promastigotes treated with an SbV and 64% for promastigotes treated with 50 μM camptothecin. Hence, the effect on cleavable complex stabilization is not attributable to nonspecific toxicity.

The effect on cleavable complex stabilization in the sensitive and resistant populations of Leishmania was the same for both forms of SbV, sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate. This indicates that the mechanism of action on cleavable complexes of both formulations is likely to be the same or that the mechanism of resistance is nonspecific. In contrast, and supporting the former possibility, the capacity of camptothecin to stabilize cleavable complexes was unaffected by in vitro selection for resistance to SbVs. This finding and the selective effect of SbVs on cleavable complex stabilization in Leishmania indicate that camptothecin and SbVs probably have different interaction sites in the formation of DNA-protein complexes or different mechanisms of action. In this regard, Palumbo et al. (17) demonstrated that two antitumor drugs of similar structure that stabilized cleavable complexes (genistein and ellipticinium) bound to different DNA sites on the cleavable complex of DNA-topoisomerase II. However, whether resistance to an SbV is the result of efflux or a qualitative or quantitative difference in the molecular target remains to be determined. Nevertheless, in vitro selection for resistance to meglumine antimoniate by using Leishmania guyanensis has been reported to be accompanied by amplification of a gene similar to the P-glycoprotein gene (9), and the amplification of the P-glycoprotein gene in Leishmania tarentolae has been shown to confer resistance to heavy metals (6).

In fact, more than one mechanism involving either permeability or target resistance, or both, could confer diminished sensitivity of Leishmania to SbVs. Other experimental approaches will be required to establish the mechanism(s) of resistance in the line selected in vitro and the strains from patients with relapses following treatment. Regardless of the mechanism, should a decrease or the absence of complex stabilization be a common expression of resistance to SbVs, the corresponding assay offers several advantages over conventional in vitro sensitivity testing and could represent a simple, robust alternative assay.

The results presented here support the drug sensitivity of the parasite as a contributory factor in treatment failure without reducing the importance of the immune response and other host factors in the clinical response to treatment. Relapses have been associated with a low or negative cutaneous hypersensitivity response to leishmanin at the time of diagnosis (20). More recently, recurrent leishmaniasis, whether the result of reinfection or relapse, was found to be associated with a significantly lower level of cutaneous hypersensitivity to Leishmania antigen at the time of initial diagnosis and at follow-up (5). It is conceivable that the relative importance of parasite sensitivity to SbVs and host immune factors varies among patients. These results and prior observations on the host response in patients with relapses suggest that the combination of a low level of sensitivity to SbVs and a low-level cell-mediated response propitiate relapse. An effective immune response may reduce the impact of a low level of sensitivity of Leishmania to SbVs, and vice versa.

The demonstration that treatment of promastigotes with an SbV, the first-line drug for the treatment of leishmaniasis, results in the stabilization of DNA-protein complexes and the fact that resistance to SbVs is accompanied by the loss of cleavable complex stabilization are consistent with prior evidence that the SbV sodium stibogluconate inhibits topoisomerase purified from L. donovanni. These findings suggest that topoisomerase may be a therapeutically important target of SbVs and encourage the targeting of alternative antileishmanial drugs to parasite topoisomerase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by USNIAID grant P50-130603 and COLCIENCIAS grant 2229-04-002-92.

We thank Walter Reed Army Institute for the provision of additive-free formulations of meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate. The assistance of Iris Segura and Jaime Muñoz in the propagation of Leishmania strains and Graciela Salinas in the standardization of DNA extraction for topoisomerase assays is acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atchinson J, Silvey S D. The generalization of probit analysis to the case of multiple responses. Biometrika. 1957;44:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman J D, Waddell D, Hanson B D. Biochemical mechanisms of the antileishmanial activity of sodium stibogluconate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:916–920. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.6.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman J D. Chemotherapy for leishmaniasis: biochemical mechanisms, clinical efficacy, and future strategies. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:560–586. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodley A L, Shapiro T. Molecular and cytotoxic effects of camptothecin, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, on Trypanosomes and Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3726–3730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosque, F., G. Milon, L. Valderrama, and N. G. Saravia. Permissivity of human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages to infection by promastigotes. J. Parasitol., in press. [PubMed]

- 6.Callahan H L, Beverley S M. Heavy metal resistance: a new role for P-glycoproteins in Leishmania. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18427–18430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty A K, Majumder H K. Mode of action of pentavalent antimonials: specific inhibition of type I DNA topoisomerase of Leishmania donovani. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;152:605–612. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ephros M, Waldman E, Zilberstein D. Pentostam induces resistance to antimony and the preservative chlorocresol in Leishmania donovani promastigotes and axenically grown amastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1064–1068. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira-Pinto K C, Miranda A L, Anacleto C, Fernandes A P S M, Abdo M C B, Petrillo M L, Moreira E S A. L. (V.) guyanensis isolation and characterization of glucantime-resistant cell lines. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:944–949. doi: 10.1139/m96-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franke E D, Wignall F S, Cruz M E, Rosales E, Tovar A A, Lucas C M, Berman J D. Efficacy and toxicity of sodium stibogluconate for mucosal leishmaniasis. Ann Intern Med. 1990;133:934–940. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Orsini S. Decreased sensitivity to meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®) of Leishmania infantum isolated from dogs after several courses of drug treatment. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86:613–620. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1992.11812717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grogl M, Thomason T M, Franke E D. Drug resistance in leishmaniasis: its implication in systemic chemotherapy of cutaneous and mucocutaneous disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:117–126. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutteridge W E, Coombs G H. Biochemistry of parasitic protozoa. London, United Kingdom: MacMillan Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiang Y H, Liu L F. Identification of mammalian DNA topoisomerase I as an intracellular target of anticancer drug camptothecin. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1722–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson J E, Tally J D, Ellis W Y. Quantitative in vitro drug potency and drug susceptibility evaluation of Leishmania sp. from patients unresponsive to pentavalent antimony therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;90:464–480. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsden P D. Mucosal leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1986;80:859–876. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(86)90243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palumbo M, Mabilia M, Pozzan A. Conformational properties of topoisomerase II inhibitors and sequence specificity of DNA cleavage. J Mol Recognit. 1994;7:227–231. doi: 10.1002/jmr.300070312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts W L, Rainey P M. Antileishmanial activity of sodium stibogluconate fractions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1842–1846. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.9.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robledo, S., A. Z. Valencia, and N. G. Saravia. Sensitivity to Glucantime® of Leishmania Viannia isolated from patients prior to treatment. Submitted for publication. [PubMed]

- 20.Saravia N G, Weigle K, Segura I, Holmes S, Pacheco S, Labrada L A, Goncalves A. Recurrent lesions in human Leishmania braziliensis reactivation or reinfection? Lancet. 1990;336:398–402. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91945-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saravia N G, Segura I, Santrich C, Holguín A F, Valderrama L, Ocampo C B. Epidemiologic, genetic and clinical associations among phenotypically distinct populations of Leishmania Viannia in Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:86–94. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weigle K, Santrich C, Martinez F, Valderrama L, Saravia N G. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia: environmental and behavioral factors for infection, clinical manifestations and pathogenicity. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:709–714. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weigle K, Saravia N G. Natural history, clinical evolution and the host-parasite interaction in New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Clin Dermatol. 1996;14:433–450. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(96)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]