Abstract

The broad antibacterial spectrum and the low incidence of seizures in meropenem-treated patients qualifies meropenem for therapy of bacterial meningitis. The present study evaluates concentrations in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the absence of pronounced meningeal inflammation. Patients with occlusive hydrocephalus caused by cerebrovascular diseases, who had undergone external ventriculostomy (n = 10, age range 48 to 75 years), received 2 g of meropenem intravenously over 30 min. Serum and CSF were drawn repeatedly and analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy. Pharmacokinetics were determined by noncompartmental analysis. Maximum concentrations in serum were 84.7 ± 23.7 μg/ml. A CSF maximum (CmaxCSF) of 0.63 ± 0.50 μg/ml (mean ± standard deviation) was observed 4.1 ± 2.6 h after the end of the infusion. CmaxCSF and the area under the curve for CSF (AUCCSF) depended on the AUC for serum (AUCS), the CSF-to-serum albumin ratio, and the CSF leukocyte count. Elimination from CSF was considerably slower than from serum (half-life at β phase [t1/2β] of 7.36 ± 2.89 h in CSF versus t1/2β of 1.69 ± 0.60 h in serum). The AUCCSF/AUCS ratio for meropenem, as a measure of overall CSF penetration, was 0.047 ± 0.022. The AUCCSF/AUCS ratio for meropenem was similar to that for other β-lactam antibiotics with a low binding to serum proteins. The concentration maxima of meropenem in ventricular CSF observed in this study are high enough to kill fully susceptible pathogens. They may not be sufficient to kill bacteria with a reduced sensitivity to carbapenems, although clinical success has been reported for patients with meningitis caused by penicillin-resistant pneumococci and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

The carbapenems imipenem and meropenem exhibit a broad spectrum of activity against pathogens including those typically involved in bacterial central nervous system (CNS) infections. Compared to newer cephalosporins, they are active against Listeria monocytogenes and many anaerobes found in brain abscesses (8, 14, 29). Against listeria-induced meningitis in guinea pigs, meropenem was as effective as ampicillin plus gentamicin (15). Data for humans, however, are lacking. While imipenem-cilastatin administration has been associated with an unacceptable incidence of epileptic seizures in children with meningitis (2), meropenem does not appear to cause seizures more frequently than β-lactam antibiotics routinely used to treat meningitis (23).

In randomized clinical trials meropenem has been shown to be as effective as cefotaxime and ceftriaxone in treating community-acquired bacterial meningitis in children and adults (12, 27). For five patients with fully developed meningeal inflammation, meropenem concentrations in lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ranged from 0.9 to 6.5 μg/ml after a single dose of 40 mg/kg of body weight. For one child with Staphylococcus epidermidis ventriculitis, however, the lumbar CSF meropenem concentration was only 0.3 μg/ml 6 h after dosing (5). Similarly, in the absence of meningeal inflammation lumbar CSF meropenem concentrations of 0.03 to 0.26 μg/ml were observed 0.5 to 2.5 h after a dose of 1 g (11).

In the early stages of meningococcal meningitis and in Streptococcus pneumoniae sepsis after splenectomy, ventricular shunt infections, and corticoid-treated meningitis, bacteria are present in the subarachnoid space in the absence of pronounced inflammation (3, 9, 10, 13, 22, 24). Furthermore, ventricular antimicrobial concentrations may be up to 10 times lower than lumbar levels after intravenous (i.v.) administration (1). For these reasons, successful treatment of bacterial CNS infections must ensure sufficient drug concentrations in lumbar and ventricular CSF under conditions of not only severe but also minor impairment of the blood-CSF barrier. In the present study we investigated the pharmacokinetics of meropenem in the ventricular CSF of patients with external ventriculostomy and minor abnormalities of the blood-CSF barrier.

(This work was presented, in part, as a poster (no. A-50) at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Canada, 28 September to 1 October 1997.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ten patients (five females and five males; age range, 48 to 75 years; serum creatinine concentration, 0.7 to 1.7 mg/dl) suffering from extracerebral infections caused by bacteria of proven or presumed (when treatment had to be initiated before susceptibility data were available) susceptibility to meropenem were included in this study. They had undergone external ventriculostomy due to occlusive hydrocephalus caused by cerebrovascular accidents. Patients with clinical evidence of ventriculitis and with serum creatinine concentrations above 2 mg/dl were not considered.

The CSF leukocyte count on the day of meropenem administration ranged from 0 to 91 cells/μl (median, 8 cells/μl), and the CSF protein content ranged from 80 to 1,716 μg/ml (median, 587 μg/ml). All patients received a first dose of 2 g of meropenem i.v. (Meronem; Zeneca GmbH, Plankstadt, Germany) over a 30-min period. Treatment was continued 16 h later with 1 g of meropenem three times a day. For further information on the patients studied see Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the patients investigateda

| Pa- tient | Age (yr), sex | Wt (kg) | Disease | Time interval (days)b | Treatment | Serum creatinine concn (mg/dl) | CLCRc (ml/min) | Serum albumin concn (g/liter) | CSF analysisd

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein concn (mg/liter) | QAlb (10−3) | WBC/ mm3 | RBC/ mm3 | |||||||||

| 1 | 48, m | 85 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | 4 | Amoxicillin, clavulanate, gentamicin, metronidazole | 1.7 | 64 | 28 | 425 | 5.4 | 91 | 8,875 |

| 2 | 75, f | 70 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 12 | 0.7 | 76 | 23 | 284 | 5.3 | 5 | 20 | |

| 3 | 63, m | 80 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | 4 | Mannitol | 0.7 | 122 | 27 | 1,630 | 29.9 | 68 | 2,560 |

| 4 | 75, f | 75 | Cerebellar hemorrhage | 7 | Mannitol | 0.8 | 72 | 28 | 848 | 10.1 | 5 | 1,605 |

| 5 | 55, f | 85 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 8 | Dexamethasone, mannitol | 0.7 | 121 | 27 | 518 | 3.0 | 26 | 4,096 |

| 6 | 52, m | 70 | Basilar artery occlusion | 3 | Mannitol, amoxicillin, gentaicin, metronidazole | 0.8 | 107 | 26 | 201 | 4.4 | 1 | 40 |

| 7 | 63, f | 80 | Infratentorial infarction | 5 | Mannitol, amoxicillin, clavulanate | 0.9 | 81 | 29 | 80 | 1.5 | 0 | 20 |

| 8 | 66, m | 95 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | 11 | Mannitol, cefotaxime, metronidazole | 0.8 | 122 | 31 | 1,716 | 4.9 | 11 | 4,690 |

| 9 | 55, m | 95 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | 8 | Dexamethasone | 0.7 | 160 | 29 | 840 | 7.8 | 44 | 7,851 |

| 10 | 60, f | 65 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | 8 | Glycerol, cefotaxime | 0.9 | 68 | 22 | 843 | 6.1 | 3 | 1,840 |

Patient order reflects descending peak CSF meropenem concentration.

Time interval between insertion of external ventriculostomy and the first meropenem infusion.

Creatinine clearance (CLCR) was estimated by the following equations: males, (140 − age) · weight · 72−1 · serum creatinine−1; females, (140 − age) · weight · 85−1 · serum creatinine−1. These equations tend to overestimate creatinine clearance in obese and emaciated patients.

WBC, leukocyte; RBC, erythrocyte.

Ventricular CSF and arterial blood were sampled from indwelling catheters before, at the end, and at 30 min and 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16 h after the end of the infusion. At 10 min after the end of the infusion, only blood was drawn. The ventricular CSF samples were drawn from the port nearest to the site of insertion of the ventriculostomy, and 1 ml of CSF was discarded before the CSF sample (1 ml) was collected. Blood was allowed to clot for 3 min. Then blood and CSF were centrifuged immediately. The supernatants were frozen at −70°C.

Informed consent to participation in this study was obtained from the nearest relative. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany.

After deproteinization with acetonitrile, serum and CSF drug concentrations were measured by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy/mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS). A total of 50 μl of each sample was separated on a reversed-phase column (40 by 4.6 mm) with an isocratic system. The mobile phase consisted of 78% 0.005 M ammonium acetate buffer and 22% acetonitrile. Peaks were monitored by a selected reaction monitoring method as follows: precursor (meropenem + H)+ → product ion for meropenem m/z 384 → m/z 68, and for the internal standard, m/z 518 → m/z 143. Meropenem eluted after 0.9 min, and the internal standard eluted after 1.5 min. Mac Quan software (version 1.4-noFPU, 1991 to 1995) (Perkin-Elmer, Toronto, Canada) was used for the evaluation of the chromatograms.

The serum and CSF samples were measured against a calibration row prepared from drug-free serum and CSF, respectively. No interferences in serum and CSF were observed for meropenem or the internal standards. Calibration was performed by weighted (1/concentration) linear regression. The linearity of the meropenem calibration curve for serum was demonstrated between 0.019 and 42.1 μg/ml. For CSF, linearity was found in a concentration range of 0.0042 to 4.91 μg/ml. The lowest calibration levels were taken as quantification limits. Samples with drug concentrations above the quantification limits were prediluted with tested drug-free plasma.

For control of interassay variation, spiked quality control samples were prepared by adding defined amounts of meropenem to tested drug-free serum and CSF. The interassay precisions of the spiked meropenem quality controls in serum were 4.1% at a drug concentration of 30.1 μg/ml, 3.3% at 3.01 μg/ml, 5.4% at 0.343 μg/ml, and 4.9% at 0.041 μg/ml. The interassay precisions of the spiked quality controls in CSF were 1.1% at a concentration of 3.94 μg/ml, 2.3% at 0.541 μg/l, 3.7% at 0.075 μg/ml, and 3.1% at 0.012 μg/ml. The accuracy of the meropenem standards ranged from 95.1 to 104.3% for serum and from 97.5 and 104.3% for CSF.

Concentration-time curves for serum and CSF were analyzed by noncompartmental pharmacokinetic methods using the program Topfit 2.0 (Gödecke-Schering-Thomae, Biberach an der Riss, Germany). Peak serum and CSF drug concentrations (CmaxS and CmaxCSF, respectively), time from the end of the infusion to the respective peak concentrations (tmaxS and tmaxCSF), and time above hypothetical MICs of 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml in CSF were directly taken from the concentration-time curves. Elimination rate constants (kel) were determined by log-linear regression analysis [weighting function g(yi) = 1/yi, where g(yi) is the weighted concentration and yi is the individual concentration as determined by LC-MS/MS], and half-lives at β phase (t1/2β) were determined as ln2/kel. The areas under the concentration-time curves for serum and CSF up to the last measurable drug concentration (AUCS0-t and AUCCSF0-t, respectively) were estimated by the linear trapezoidal rule. Extrapolation to infinity (AUCS, AUCCSF) was done by dividing the last measurable drug concentration (Cl) by kel, and the ratio AUCCSFextrapolated/AUCCSF was expressed as a percentage. The total clearance in serum (CL) was calculated as dose/AUCS, and the apparent volume of distribution (Vβ) was calculated as dose/(AUCS · kel). The volume of distribution in steady state (VSS) was determined as CL · [mean residence time − (infusion time/2)], where the mean residence time is defined as ∫0∞ CS(t) · tdt/AUCS. The exit rate constant from CSF (koutCSF or CLoutCSF/VCSF) was determined by plotting ΔCCSF versus AUCCSF/AUCS · AUCStn→tn+1 − AUCCSFtn→tn+1. Linear least-square regression yielded a straight line without intercept, the slope equalling koutCSF (26). koutCSF can be used to estimate the approximate elimination half-life from CSF after intraventricular injection of meropenem (t*1/2CSF) by using the equation koutCSF = ln2/t*1/2CSF.

Pharmacokinetic data were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). Medians are provided to facilitate comparison with previous data on CSF penetration by other compounds, where normal distributions were not always present. The determinants of the entry of meropenem into CSF were analyzed by stepwise multiple linear regression with AUCCSF and CmaxCSF as dependent variables and AUCS, CmaxS, VSS, t1/2βS, age, serum creatinine, CSF protein content, CSF-to-serum albumin ratio (QAlb), time interval between insertion of external ventriculostomy and the first meropenem infusion, and CSF leukocyte count as independent variables.

RESULTS

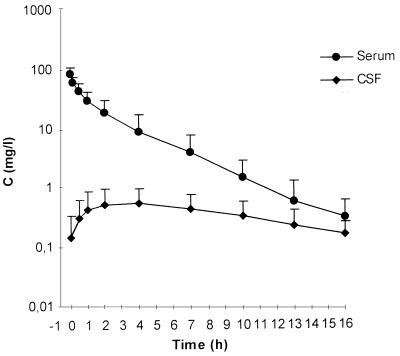

At the end of the infusion, maximum serum meropenem concentrations were 84.7 ± 23.7 μg/ml (mean ± SD). CL was 270 ± 137 ml/min, and the VSS amounted to 28.7 ± 6.8 liters (Table 2). The mean maximum CSF drug concentration of 0.63 ± 0.50 μg/ml was observed 4.1 ± 2.6 h after the end of the infusion. The lowest individual patient CSF maximum observed was 0.13 μg/ml, and the highest was 1.60 μg/ml. Elimination from CSF was considerably slower than from serum (t1/2β of 7.36 ± 2.89 h in CSF versus t1/2β of 1.69 ± 0.60 h in serum) (Fig. 1). The AUCCSF/AUCS ratio for meropenem, as a measure of overall CSF penetration, was 0.047 ± 0.022 (Table 3). koutCSF ranged from 0.056 to 0.321/h, corresponding to an approximate elimination half-life from CSF, which would be effective after intraventricular injection of meropenem (t*1/2CSF), of 6.75 ± 3.44 h (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic properties of meropenem in serum after i.v. administration of 2 g

| Patient | Cmax (mg/l) | AUC (mg · h/liter) | CL (ml/min) | CL/kg (ml/min/kg) | t1/2β (h) | Vβ (liter) | VSS (liter) | VSS/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 90.6 | 210.6 | 158 | 1.86 | 2.72 | 37.2 | 31.9 | 0.38 |

| 2 | 132.4 | 305.1 | 109 | 1.56 | 2.34 | 22.2 | 19.8 | 0.28 |

| 3 | 96.1 | 206.4 | 162 | 2.03 | 1.11 | 15.5 | 28.1 | 0.35 |

| 4 | 80.5 | 234.3 | 142 | 1.89 | 2.32 | 28.6 | 26.4 | 0.35 |

| 5 | 82.1 | 91.2 | 365 | 4.29 | 1.32 | 41.8 | 24.6 | 0.29 |

| 6 | 90.6 | 135.1 | 247 | 3.53 | 1.24 | 26.5 | 25.2 | 0.36 |

| 7 | 56.9 | 130.0 | 256 | 3.20 | 1.96 | 43.5 | 34.5 | 0.43 |

| 8 | 101.6 | 97.1 | 343 | 3.61 | 1.01 | 30.0 | 19.9 | 0.21 |

| 9 | 65.6 | 60.7 | 549 | 5.78 | 1.44 | 68.7 | 37.8 | 0.40 |

| 10 | 51.0 | 90.2 | 369 | 5.68 | 1.41 | 45.2 | 38.9 | 0.60 |

| Mean (± SD)a | 84.7 (23.7) | 156.1 (78.9) | 270 (137) | 3.34 (1.55) | 1.69 (0.60) | 35.9 (15.0) | 28.7 (6.8) | 0.37 (0.10) |

| Median | 86.4 | 132.6 | 252 | 3.37 | 1.43 | 33.6 | 27.3 | 0.36 |

SD, standard deviation.

FIG. 1.

Concentration-time curves of meropenem in serum and CSF after i.v. administration of 2 g in patients with external ventriculostomy. Note the lag time between maximum serum and CSF meropenem concentrations and the slow drug elimination from CSF. Data are means (± SD) for 10 patients.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic properties of meropenem in CSF after i.v. administration of 2 g

| Patient | Cmax (mg/liter) | Tmaxa (h) | AUC (mg · h/liter) | AUCCSFextrapolated/ AUCCSF (%) | t1/2β (h) | AUCCSF/ AUCS | Time (h) above a MIC of:

|

t*1/2CSF (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.125 μg/ml | 0.5 μg/ml | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.60 | 2 | 14.2 | 16.1 | 5.65 | 0.067 | 16 | 9 | 2.18 |

| 2 | 1.22 | 4 | 17.2 | 33.1 | 8.55 | 0.056 | 16 | 11 | 5.68 |

| 3 | 1.09 | 4 | 18.3 | 30.3 | 7.79 | 0.089 | 16 | 13 | 8.46 |

| 4 | 0.65 | 7 | 14.7 | 43.7 | 11.9 | 0.063 | 16 | 12 | 10.66 |

| 5 | 0.48 | 4 | 4.46 | 9.8 | 4.57 | 0.049 | 15 | 0 | 4.63 |

| 6 | 0.41 | 10 | 5.80 | 14.7 | 6.46 | 0.043 | 13 | 0 | 8.61 |

| 7 | 0.29 | 2 | 4.87 | 30.6 | 8.31 | 0.037 | 14 | 0 | 7.87 |

| 8 | 0.24 | 2 | 2.27 | 14.1 | 5.30 | 0.023 | 8 | 0 | 4.78 |

| 9 | 0.20 | 2 | 1.18 | 4.2 | 3.31 | 0.019 | 3 | 0 | 2.16 |

| 10 | 0.13 | 4 | 2.54 | 44.4 | 11.8 | 0.028 | 3 | 0 | 12.47 |

| Mean (SDb) | 0.63 (0.50) | 4.1 (2.6) | 8.55 (6.73) | 26.1 (16.4) | 7.36 (2.89) | 0.047 (0.022) | 12 (5) | 5 (6) | 6.75 (3.44) |

| Median | 0.45 | 4 | 5.34 | 23.4 | 7.13 | 0.046 | 14 | 0 | 6.77 |

Tmax, time to maximum concentration.

SD, standard deviation.

In the case of highly susceptible bacteria requiring a MIC of 0.125 μg/ml, the time above the MIC in CSF would be 12 ± 5 h. In the presence of a moderately susceptible bacterium requiring a MIC of 0.5 μg/ml the CSF meropenem concentrations would be below the MIC for the whole period of observation for six patients. For the other four patients the time above the MIC would range from 9 to 13 h (Table 3).

Stepwise multiple linear regression with AUCCSF as the dependent variable yielded three variables, which explained 98% of the variance (P < 0.00005): AUCS, QAlb, and CSF leukocyte density. Similarly, for the dependent variable CmaxCSF, AUCS, CSF leukocyte count, and QAlb explained 97% of the variance (P < 0.00005) (Table 4). The inclusion of additional independent variables (VSS, t1/2βS, age, serum creatinine, CSF protein content, time interval between insertion of external ventriculostomy and the first meropenem infusion) only led to small, nonsignificant increases of the goodness of fit (R2).

TABLE 4.

Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis of the entry of meropenem into ventricular CSF

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | R2 | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUCCSF | AUCS | 0.87 | 53.4 | 0.0001 |

| QAlb | 0.97 | 100.3 | <0.00005 | |

| CSF leukocyte density | 0.98 | 131.0 | <0.00005 | |

| CmaxCSF | AUCS | 0.64 | 14.2 | 0.0055 |

| CSF leukocyte density | 0.94 | 59.2 | <0.00005 | |

| QAlb | 0.97 | 69.5 | <0.00005 |

DISCUSSION

Meropenem is a weak acid with a pKa of 2.9. At physiological pH, it is highly ionized and hydrophilic (manufacturer’s information). The molecular mass of the anhydrous free acid is 383.5 Da and that of the trihydrate is 437.5 Da. Binding to serum proteins is neglegibly low (11) and should not affect CSF penetration (21). As with other hydrophilic compounds with similar molecular masses (16, 18, 19), maximum concentrations in CSF were observed several hours after the end of the meropenem infusion and drug elimination was substantially slower from CSF than from serum. In the present study, after a single dose of 2 g of meropenem, maximum concentrations in CSF (median, 0.45 μg/ml) were almost identical to those observed after a 2-g i.v. dose of cefotaxime or ceftriaxone (median, 0.44 and 0.43 μg/ml, respectively [19]). Meropenem CSF maxima were lower than maximum CSF concentrations encountered after the administration of 3 g of ceftazidime (18) or 6 g of piperacillin (16). The AUCCSF/AUCS ratio for meropenem (0.046) compared well with the median AUCCSF/AUCS ratios for ceftazidime (0.054) (18) and piperacillin (0.034) (16) but was two- to threefold below that for cefotaxime (0.12) and approximately seven times above the median AUCCSF/AUCS ratio for ceftriaxone (0.007) (19). We are unaware of a comparable study concerning the penetration of imipenem into the ventricular CSF. An investigation of imipenem in lumbar CSF 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after i.v. administration of 1 g of imipenem and 1 g of cilastatin yielded mean imipenem concentrations of 0.62 to 0.90 μg/ml, i.e., concentrations similar to those found by us in ventricular CSF after 2 g of meropenem. The AUCCSF1–8h/AUCS1–8h ratio for imipenem in the absence of meningeal inflammation was 0.073. Extrapolation to infinity was not performed. In the presence of meningeal inflammation, lumbar CSF imipenem concentrations were two to three times higher than those without inflamed meninges (6).

In all patients, elimination from the CSF space was slower than elimination from serum. To assess the effect of the passage of drug from blood to CSF during the elimination phase on t1/2βCSF, the exit rate constant koutCSF was calculated allowing an estimate of the elimination half-life from CSF, which would be effective after intraventricular drug injection (t*1/2CSF). Independent of t1/2βS, the t*1/2CSFs should be almost identical for hydrophilic drugs predominantly cleared from CSF by bulk flow. On average, t*1/2CSF was 0.6 h shorter than t1/2βCSF (Table 3). The relatively long elimination half-life of meropenem in CSF suggests accumulation after repeated dosing. Assuming linear kinetics, mean CSF drug concentrations in steady state can be estimated from the AUCCSF after the first dose by dividing AUCCSF by the dosing interval (17). The mean AUCCSF of meropenem was 8.55 mg · h/liter. Repeated doses of 2 g and dosing intervals of 8 h, i.e., the maximum daily dose recommended by the manufacturer, would result in mean steady state concentrations in CSF of approximately 1.1 μg/ml.

In the present study, stepwise multiple linear regression analysis using both AUCCSF and CmaxCSF as dependent variables demonstrated the impact of AUCS upon penetration into CSF. Consistently, the patient with an elevated serum creatinine concentration and the two oldest patients ranked first, second, and fourth with respect to the maximum CSF concentration and second, third, and fourth with respect to AUCCSF. Parameters describing the state of the blood-CSF barrier (QAlb and CSF leukocyte count) also had a substantial influence on CSF penetration. In the case of AUCCSF, the QAlb was more significant than the CSF leukocyte count in explaining the interindividual variance of the entry of meropenem into CSF. The patient with the greatest QAlb ranked first with respect to AUCCSF. With CmaxCSF, the increase of R2 was greater with the CSF leukocyte count than with the QAlb. In both cases, the increase of R2 achieved by the inclusion of the third independent variable was small but significant.

In a previous study of lumbar CSF during severe meningeal inflammation, meropenem concentrations after a single dose of 40 mg/kg (0.9 to 6.5 μg/ml) were higher than those found by us (5). The two probable reasons are as follows: (i) disruption of the blood-CSF barrier of our patients, as estimated by the CSF protein content and the QAlb, ranged from absent to moderate and (ii) in the present study, meropenem concentrations were determined in ventricular CSF. The current practice of measuring lumbar CSF antibiotic concentrations and assuming identical antibiotic concentrations in all parts of the CSF compartment often overestimates the antibiotic concentrations in the CSF surrounding the brain. In a recent study of primates the AUC of lamivudine was approximately five times higher in the lumbar than in the ventricular CSF after i.v. infusion (1). For these reasons, the CSF drug concentrations measured by us are probably the minimum concentrations which can be encountered in bacterial CNS infections.

The maximum CSF meropenem concentrations of all patients included in this study equalled or surmounted the MICs at which 90% of isolates are inhibited (MIC90s) for Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, penicillin-sensitive Streptococcus pneumoniae, and for most members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (≤0.125 μg/ml) (8, 29). For the majority of patients, the CSF maxima were above the MIC90s of L. monocytogenes, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and Serratia marcescens strains (0.25 μg/ml). Less than half of our patients, however, reached a CSF maximum corresponding to the MIC90s of Bacteroides spp. (0.5 μg/ml) and penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae (0.5 and 1 μg/ml) (8, 25, 29). Nevertheless, three cases of S. pneumoniae meningitis caused by strains for which the MICs were 0.25 to 1 μg/ml were successfully treated with meropenem (30). The MIC90 of P. aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp. (8 μg/ml) (8, 29) was considerably higher than the maximum CSF concentration encountered in this study. Again, two cases of successful treatment of Pseudomonas meningitis with meropenem have been documented (4, 7). The MIC90 of meropenem for Staphylococcus epidermidis was 4.3 μg/ml (29). Methicillin resistance frequently encountered in S. epidermidis precludes the use of any β-lactam antibiotic. Therefore, meropenem is only suitable for methicillin-sensitive strains with documented susceptibility.

In the case of a fully susceptible bacterium for which the meropenem MIC is 0.125 μg/ml, the meropenem concentration in CSF would be above the MIC for most of the observation period (12 ± 5 h). However, for 6 of 10 patients concentrations in CSF did not reach 0.5 μg/ml (Table 3). Obviously, with the CSF levels observed, a meropenem concentration/MIC ratio above 10, which is probably required for a rapid bactericidal effect in experimental meningitis (20, 28), will only be reached in the presence of highly susceptible pathogens. Yet, the minimum CSF antibiotic concentration in relation to the MIC and MBC essential for successful eradication of bacteria remains to be determined. An exact MIC determination is mandatory for CNS infections in order to assess whether sufficient CSF drug concentrations can be counted upon. In selected cases the measurement of CSF drug concentrations may be necessary. To overcome the problem of minor meningeal inflammation in bacterial CNS infections, more lipophilic compounds, whose CSF penetration is less dependent on the functional state of the blood-CSF barrier, may be used in combination with cephalosporins or carbapenems. This strategy has been advocated for dexamethasone-treated patients with bacterial meningitis (24).

In conclusion, in the presence of minor impairment of the blood-CSF barrier, the CSF maxima of meropenem in ventricular CSF were high enough to kill fully susceptible pathogens. They may not be sufficient for bacteria with a reduced sensitivity to carbapenems, although clinical success has been reported for patients with meningitis caused by penicillin-resistant pneumococci and P. aeruginosa. From a pharmacokinetic view, increasing the dose of meropenem to 8 to 12 g/day, as is current practice with other β-lactam antibiotics, would be desirable in these conditions. We are, however, unaware of data which would indicate that such high doses of meropenem would be tolerated without toxic side effects. The AUCCSF/AUCS ratio for meropenem, as a measure of overall CSF penetration, was similar to that for β-lactam antibiotics with a low binding to serum proteins. The elimination half-life in CSF of approximately 7 h suggests moderate accumulation after repeated dosing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported, in part, by Zeneca GmbH, Plankstadt, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaney S M, Daniel M J, Harker A J, Godwin K, Balis F M. Pharmacokinetics of lamivudine and BCH-189 in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of nonhuman primates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2779–2782. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckley M M, Brogden R N, Barradell L B, Goa K L. Imipenem/cilastatin: a reappraisal of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1992;44:408–444. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199244030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabellos C, Martinez-Lacasa J, Martos A, Tubau F, Fernandez A, Viladrich P F, Gudiol F. Influence of dexamethasone on efficacy of ceftriaxone and vancomycin therapy in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2158–2160. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chmelik V, Gutvirth J. Meropenem treatment of post-traumatic meningitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:922–923. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.6.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagan R, Velghe L, Rodda J L, Klugman K P. Penetration of meropenem into the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with inflamed meninges. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:175–179. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dealy D H, Duma R J, Tartaglione T A, Beightol L A, Patterson P M. Abstracts of the 14th International Congress on Chemotherapy, Kyoto, Japan. 1985. Penetration of primaxin (N-formimidoyl thienamycin and cilastatin) into human cerebrospinal fluid, abstr. S-78-4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnelly J P, Horrevorts A M, Sauerwein R W, de Pauw B E. High dose meropenem in meningitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lancet. 1992;339:1117. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90714-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, J. R. 1995. Meropenem: a microbiological overview. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36(Suppl. A):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Forward K R, Fewer H D, Stiver H G. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections. A review of 35 infections in 32 patients. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:389–394. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.59.3.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gietz J, Prange H, Nau R. Pneumokokken-Sepsis und -Meningitis bei Erwachsenen nach Splenektomie. In: Prange H, Bitsch A, editors. Bakterielle ZNS-Erkrankungen bei systemischen Infektionen. Darmstadt, Germany: Steinkopff; 1997. pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson, M., K. L. Faulkner, P. J. Turner, S. J. Haworth, W. Sheikh, H. Nadler, and D. H. Pitkin. 1995. A compilation of meropenem tissue distribution data. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36(Suppl. A):43–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Klugman K P, Dagan R the Meropenem Meningitis Study Group. Randomized comparison of meropenem with cefotaxime for treatment of bacterial meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1140–1146. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore C M, Ross M. Acute bacterial meningitis with absent or minimal cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities. Clin Pediatr. 1973;12:117–118. doi: 10.1177/000992287301200216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray P R, Niles A C. In-vitro activity of meropenem (SM-7338), imipenem, and five other antibiotics against anaerobic clinical isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;13:57–61. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(90)90055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nairn, K., G. L. Shepherd, and J. R. Edwards. 1995. Efficacy of meropenem in experimental meningitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36(Suppl. A):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Nau R, Kinzig-Schippers M, Sörgel F, Schinschke S, Rössing R, Müller C, Kolenda H, Prange H W. Kinetics of piperacillin and tazobactam in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid of hydrocephalic patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:987–991. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nau R, Prange H W. Estimation of steady state antibiotic concentration in cerebrospinal fluid from single-dose kinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49:407–409. doi: 10.1007/BF00203787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nau R, Prange H W, Kinzig M, Frank A, Dressel A, Scholz P, Kolenda H, Sörgel F. Cerebrospinal fluid ceftazidime kinetics in patients with external ventriculostomies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:763–766. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nau R, Prange H W, Muth P, Mahr G, Menck S, Kolenda H, Sörgel F. Passage of cefotaxime and ceftriaxone into cerebrospinal fluid of patients with uninflamed meninges. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1518–1524. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.7.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nau R, Schmidt T, Kaye K, Froula J L, Täuber M G. Quinolone antibiotics in therapy of experimental pneumococcal meningitis in rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:593–597. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nau R, Sörgel F, Prange H W. Lipophilicity at pH 7.4 and molecular size govern the entry of not actively transported drugs into the cerebrospinal fluid in humans with uninflamed meninges. J Neurol Sci. 1994;122:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noetzel M J, Baker R P. Shunt fluid examination: risks and benefits in the evaluation of shunt malformation and infection. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:328–332. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.61.2.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norrby, S. R., P. A. Newell, K. L. Faulkner, and W. Lesky. 1995. Safety profile of meropenem: international clinical experience based on the first 3125 patients treated with meropenem. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36(Suppl. A):207–223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Paris M M, Hickey S M, Uscher M I, Shelton S, Olsen K D, McCracken G H. Effect of dexamethasone on therapy of experimental penicillin- and cephalosporin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1320–1324. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pikis A, Donkersloot J A, Akram S, Keith J M, Campos J M, Rodriguez W J. Decreased susceptibility to imipenem among penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:105–108. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawchuk R J, Hedaya M A. Modeling the enhanced uptake of zidovudine (AZT) into cerebrospinal fluid. 1. Effect of probenecid. Pharm Res. 1990;7:332–338. doi: 10.1023/a:1015854902915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmutzhard, E., K. J. Williams, G. Vukmirovits, V. Chmelik, B. Pfausler, A. Featherstone, and the Meropenem Meningitis Study Group. 1995. A randomised comparison of meropenem with cefotaxime or ceftriaxone for the treatment of bacterial meningitis in adults. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36(Suppl. A):85–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Täuber M G, Doroshow C A, Hackbarth C J, Rusnak M G, Drake T A, Sande M A. Antibacterial activity of β-lactam antibiotics in experimental meningitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:568–574. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiseman L R, Wagstaff A J, Brogden R N, Bryson H M. Meropenem: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy. Drugs. 1995;50:73–101. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeneca GmbH. 1997. Data on file.