Abstract

Tissue pharmacokinetics of trovafloxacin, a new broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agent, were measured by positron emission tomography (PET) with [18F]trovafloxacin in 16 healthy volunteers (12 men and 4 women). Each subject received a single oral dose of trovafloxacin (200 mg) daily beginning 5 to 8 days before the PET measurements. Approximately 2 h after the final oral dose, the subject was positioned in the gantry of the PET camera, and 1 h later 10 to 20 mCi of [18F]trovafloxacin was infused intravenously over 1 to 2 min. Serial PET images and blood samples were collected for 6 to 8 h, starting at the initiation of the infusion. Drug concentrations were expressed as the percentage of injected dose per gram, and absolute concentrations were estimated by assuming complete absorption of the final oral dose. In most tissues, there was rapid accumulation of the radiolabeled drug, with high levels achieved within 10 min after tracer infusion. Peak concentrations of more than five times the MIC at which 90% of the isolates are inhibited (MIC90) for most members of Enterobacteriaceae and anaerobes (>10-fold for most organisms) were achieved in virtually all tissues, and the concentrations remained above this level for more than 6 to 8 h. Particularly high peak concentrations (micrograms per gram; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) were achieved in the liver (35.06 ± 5.89), pancreas (32.36 ± 20.18), kidney (27.20 ± 10.68), lung (22.51 ± 7.11), and spleen (21.77 ± 11.33). Plateau concentrations (measured at 2 to 8 h; micrograms per gram; mean ± SEM) were 3.25 ± 0.43 in the myocardium, 7.23 ± 0.95 in the lung, 11.29 ± 0.75 in the liver, 9.50 ± 2.72 in the pancreas, 4.74 ± 0.54 in the spleen, 1.32 ± 0.09 in the bowel, 4.42 ± 0.32 in the kidney, 1.51 ± 0.15 in the bone, 2.46 ± 0.17 in the muscle, 4.94 ± 1.17 in the prostate, and 3.27 ± 0.49 in the uterus. In the brain, the concentrations (peak, ∼2.63 ± 1.49 μg/g; plateau, ∼0.91 ± 0.15 μg/g) exceeded the MIC90s for such common causes of central nervous system infections as Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC90, <0.2 μg/ml), Neisseria meningitidis (MIC90, <0.008 μg/ml), and Haemophilus influenzae (MIC90, <0.03 μg/ml). These PET results suggest that trovafloxacin will be useful in the treatment of a broad range of infections at diverse anatomic sites.

Trovafloxacin {1α,5α,6α-7-(6-amino-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hex- 3-yl)-1-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-6-fluoro-1,4-dihydro-4-oxo-1,8- naphthyridine-3-carboxylic acid}, or CP 99,219, is a new, highly potent fluoroquinolone with broad-spectrum in vitro activity against gram-positive and gram-negative organisms (8). Comparisons of its in vitro antibacterial activity with those of other fluoroquinolones revealed that trovafloxacin is significantly more potent against many gram-positive organisms, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and ciprofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant staphylococci (9, 20, 21, 25, 26, 33). Trovafloxacin also has high potency against anaerobic organisms (3, 4, 37, 44) and activity against members of the Enterobacteriaceae (5, 42). In general, trovafloxacin has greater potency (MIC at which 90% of the isolates are inhibited [MIC90], <2 μg/ml) and a broader antimicrobial spectrum than ciprofloxacin, temafloxacin, sparfloxacin, fleroxacin, and ofloxacin (6, 17, 31, 42, 43). Organisms for which the MIC90s of trovafloxacin are >4 μg/ml are rare and include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacteroides fragilis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, and oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. In vivo, trovafloxacin was shown to have significant antimicrobial activity in numerous experimental infection models (1, 18, 19, 23, 32, 34). Early clinical studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in a variety of infections, including uncomplicated gonorrhea, at single oral doses as low as 50 mg (22).

Single- and multiple-dose safety and pharmacokinetic studies with healthy humans have demonstrated that the drug is well tolerated and that a dosage of 200 mg once or twice daily should be adequate for the treatment of systemic infections caused by most common bacterial pathogens (38, 39, 45). Studies of the tissue distribution of trovafloxacin in laboratory animals have demonstrated rapid absorption from the gastrointestinal tract (unpublished results) and high concentrations in virtually all tissues (12). For humans, concentrations of trovafloxacin have been measured in bodily fluids and a small number of tissues (29, 40). However, detailed studies of tissue distribution have not been reported. To optimize the clinical use of trovafloxacin, detailed pharmacokinetic data on the distribution of drug to different tissues would be of considerable value in designing dosing schedules that maximize therapeutic efficacy for different types of infection.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is an extremely powerful in vivo technique for making detailed pharmacokinetic measurements in both animal models of infection and humans (10, 11, 13–15, 27, 28, 36). Since trovafloxacin contains three fluorine atoms, PET with 18F-labeled trovafloxacin holds great promise for pharmacokinetic measurements. Recently, we developed a method for radiolabeling trovafloxacin by exchanging 18F for 19F (2, 41), demonstrated that the radiolabeled drug is chemically identical to the native drug, and performed pharmacokinetic studies with normal and infected rats and rabbits (12). Because trovafloxacin undergoes a low level of in vivo metabolism within 6 to 8 h after injection in humans, tissue and blood radioactivity measurements within this time frame should accurately reflect concentrations of intact drug (30). We report here the results of tissue pharmacokinetic studies using PET and [18F]trovafloxacin in healthy human subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of [18F]trovafloxacin.

[18F]trovafloxacin (CP 99,219) was prepared by exchange of 18F for 19F and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography. 18F was prepared by the 18O(p,n) 18F nuclear reaction (24), added to a mixture of K2CO3 (4.0 mg) and Kryptofix 2.2.2. (14.6 mg), and dried azeotropically with acetonitrile. The residue was combined with 1.0 mg of trovafloxacin dissolved in 0.5 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide and heated at 160°C for 15 min. Purification was performed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography with a 250- by 10-mm Vydac C18 column (mobile phase; 83:17 phosphate buffer [pH 4.4]-acetonitrile; flow rate, 4 ml/min). The product was collected in a sterile glass vial, evaporated to dryness in vacuo, dissolved in sterile saline for injection (United States Pharmacopea), and sterilized with a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter (Millex-GS; Millipore). This method routinely provided 18F-labeled trovafloxacin with radiochemical yields of 15 to 30% (end of synthesis) and radiochemical purity of >97% within 45 min. Prior to administration, the product was determined to be pyrogen free by the Limulus amebocyte lysate test. Sterility was verified after injection. Further details of the radiolabeling procedure have been described elsewhere (2).

Safety considerations.

An acute-toxicity study with radiolabeled trovafloxacin was performed prior to human use. Briefly, groups of six rats were injected with either [18F]trovafloxacin (at a dose 100-fold higher than the proposed human dose) or vehicle. Food and water intake and body weight were measured for 7 days, and the animals were observed for gross signs of toxicity. At the end of the observation period, the rats were sacrificed, and histological sections of the brain, heart, lung, liver, spleen, kidney, skeletal muscle, bowel, testicle, bone, and prostate were examined by a board-certified pathologist.

Medical internal radiation dose calculations, based on biodistribution data for rats, indicated that approximately 20 mCi of [18F]trovafloxacin can be administered without delivering a radiation burden in excess of 20 mGy to any organ (unpublished results). This dose of radioactivity is adequate for measuring trovafloxacin pharmacokinetics in humans over 8 to 10 h by PET.

Human subjects.

Twelve healthy male (mean age, 34.00 ± 5.52 years; range, 23 to 43 years) and 4 healthy female (mean age, 28.00 ± 4.85 years; range, 24 to 35 years) volunteers were studied. The female subjects were required to have regular menstrual cycles for enrollment in the study. Prior to participation in the study, each subject had a complete medical history interview and physical examination, electrocardiogram, urinalysis, complete blood count (with differential count), and blood chemistries (levels of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase). Female volunteers were studied at 3 days postmenstruation and underwent serum pregnancy testing within 24 h before injection of radiolabeled drug. Each subject was treated with a single oral dose of trovafloxacin (200 mg) daily for 5 to 8 days before the PET study. The physical examination, urinalysis, complete blood count, and blood chemistries were repeated 1 week after imaging.

The human study protocol was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital committees on human studies, pharmacy, and radioisotopes. All subjects gave written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Pharmacokinetics of trovafloxacin.

Approximately 2 h after receiving the final oral dose of trovafloxacin, each subject was positioned in the gantry of the PET camera, and a venous catheter was placed in each arm (one for infusion of drug and one for blood sampling). One hour later 10 to 20 mCi of [18F]trovafloxacin was infused intravenously over 1 to 2 min. Serial PET imaging and blood sampling were initiated at the start of the infusion and continued for approximately 6 to 8 h. Blood samples (2 ml) were collected at 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 25, 30, and 45 min and at 1, 1.5, 2, 4, and 6 to 8 h after the start of infusion. Due to the limited field of view of the PET camera and the short physical half-life of 18F, detailed pharmacokinetic studies were performed for specific groups of organs in different sets of subjects; extracranial organs were studied in eight males and the four females, and the brain was studied in four males. Two imaging protocols were employed. For the study of extracranial organs, two body regions were imaged: the first included the heart, lung, and bone, and the second included the abdomen and pelvis. The uterus was included in the data set for the abdomen and pelvis.

Each subject was positioned supine on the imaging bed of the PET camera with his or her arms extended out of the field of view. For imaging of the extracranial organs, the subject was positioned on the basis of reconstructed transmission data so that the organs of interest were included in the field of view. For later imaging, positioning marks were drawn on the subject’s thorax, abdomen, and pelvis. During the first 2 h, serial 2-min images of both organ groups were acquired. The bed positions (corresponding to the two body regions) were switched under computer control. After the last image was acquired the subject was allowed to resume usual activity. At 4 and 6 to 8 h after the start of the infusion, the subject was repositioned in the PET camera, and 10- to 15-min images were acquired in each position. A transmission scan was acquired after each repositioning. For brain studies, the subject’s head was fixed with an individually fabricated head holder (Tru Scan Image Inc., Annapolis, Md.), and serial images were acquired in two bed positions. The timing of the imaging was identical to that described above.

Images were acquired with a PC-4096 PET camera (Scanditronix AB, Uppsala, Sweden), and concentrations of [18F]trovafloxacin in blood were measured with a well counter. The primary imaging parametric values for the PC-4096 camera are in-plane and axial resolutions of a 6.0-mm full width of photopeak measured at half maximum count, 15 contiguous slices at a 6.5-mm separation, and a sensitivity of ∼5,000 cps/mCi (35).

Analytical methods.

The PET images were reconstructed by using a conventional filtered back-projection algorithm to an in-plane resolution of a 7-mm full width of photopeak measured at half maximum count. Attenuation correction was performed with transmission images acquired with a rotating pin source containing 68Ge. All projection data were corrected for nonuniformity of detector response, dead time, random coincidences, and scattered radiation. Regions of interest were circular, with a fixed diameter of 16 mm (8 mm for the myocardium). The PET camera was cross-calibrated with a well scintillation counter by comparing the camera response to a uniformly distributed 18F solution in a 20-cm-diameter cylindrical phantom with the response of the well counter to an aliquot of the same solution.

The concentration of trovafloxacin in each organ (expressed as the percentage of injected dose [ID] per gram) was calculated by dividing the concentration of [18F]trovafloxacin in each tissue determined by PET (nanocuries per cubic centimeter) by the total ID of drug (nanocuries) and multiplying by 100.

Since the density of most organs is ∼1 g/cm3, concentrations expressed as percentage of ID per cubic centimeter are approximately equal to concentrations expressed as percentage of ID per gram. For the lung, concentrations were corrected for lung tissue density, ∼0.26 ± 0.03 g/cm3 (16). The concentrations of trovafloxacin in the brain were quite low, and radioactivity in the blood made a significant contribution to brain tissue concentrations measured by PET. To correct for this effect, concentrations in brain parenchyma were corrected by subtracting 4% of the concentration of drug in blood from the total tissue concentration. This correction did not have a significant effect on trovafloxacin concentrations in the other tissues.

Pharmacokinetic parameters.

For each subject, the time dependence of drug concentration (percentage of ID per gram) was tabulated and averaged to yield composite time-concentration curves for each tissue. From the average time-concentration curves, the following pharmacokinetic parameters were determined in terms of percentage of ID per gram for each tissue: peak concentration, plateau concentration (average concentration from 2 to 8 h after injection [15]), and normalized area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) (AUC/period of measurement). AUCs were calculated by numerical integration by using the trapezoidal rule. It was assumed that the final oral dose of trovafloxacin is completely absorbed, and the pharmacokinetic parameters were converted to absolute concentration units by multiplication by the quotient obtained by dividing the ID by 100.

The lowest concentrations of radioactivity that were measured in the present study were approximately 100 nCi/cm3, with a precision of ±5%. For an ID of 10 mCi, this corresponds to a quantitation limit of 0.001% ID/cm3. In terms of absolute drug concentration, this represents a quantification limit of ∼2.0 μg/cm3 if 200 mg of unlabeled drug is injected with the tracer.

Statistical analysis.

The results of the pharmacokinetic studies were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance with a linear model in which organ was the classification variable. Post hoc comparisons of drug concentrations in individual tissues were performed by Duncan’s new multiple-range test (7). In order to describe the blood clearance of trovafloxacin in terms of a limited number of parameters, the time dependence of the blood concentration of drug was fit to a biexponential function by a nonlinear least-squares method (weighted to variance) by using the program PROC NLIN (SAS Institute). All results are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEMs).

RESULTS

The results of the acute-toxicity study did not demonstrate any adverse effects of the radiolabeled drug. Similarly, in the human volunteers, the results of physical examination and laboratory tests were not affected by administration of [18F]trovafloxacin. Mild drug-related side effects were noted in several of the volunteers; however, only one of them withdrew from the study because of these symptoms. These side effects included dizziness, restlessness, fatigue, headache, or incoordination (five subjects) and gastrointestinal complaints, primarily nausea or a bad taste (four subjects), with two of the subjects having complaints in both these sets. An additional subject complained of pruritus without evident rash. All symptoms resolved with cessation of the drug.

Pharmacokinetics of trovafloxacin in the brain.

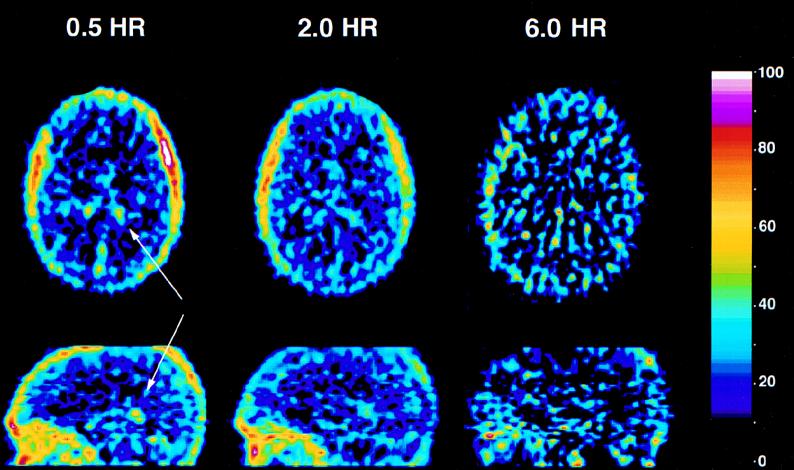

Figure 1 shows PET images of the brain (at 52 mm above the orbitomeatal line) of a healthy male volunteer acquired at 0.5, 2, and 6 h after intravenous injection of [18F]trovafloxacin. These images indicate that trovafloxacin accumulation in the brain largely parallels blood volume. The time dependence of trovafloxacin accumulation in the brain is shown in Fig. 2. The peak and plateau concentrations and normalized AUC were 2.63 ± 1.49, 0.91 ± 0.15, and 1.13 ± 0.33 μg/g, respectively. From these data, it is apparent that trovafloxacin enters the brain rapidly (peak concentration occurs within 10 min after the start of infusion) and distributes uniformly to all neural structures. In some of the early images, focal accumulation of tracer was observed in the region of the lateral ventricles, possibly representing accumulation in the choroid plexus.

FIG. 1.

Representative PET images of the brain of a healthy male subject at 30 min, 2 h, and 6 h after intravenous injection of [18F]trovafloxacin. All images were recorded at 52 mm above the orbitomeatal line. The area of maximum concentration on each image is represented as 100% on the color scale.

FIG. 2.

Representative tissue distribution curves of trovafloxacin in the indicated tissues of healthy human subjects. Tissue concentrations of trovafloxacin were measured by PET and are expressed as the means ± SEMs for 16 subjects (12 males and 4 females).

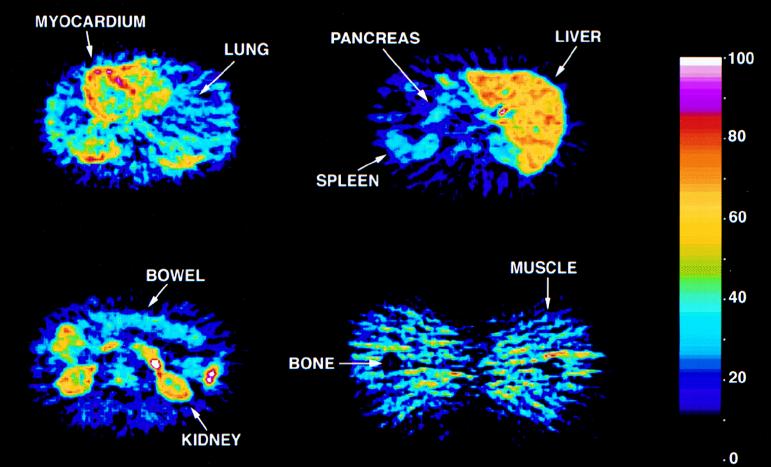

Pharmacokinetics of trovafloxacin in peripheral tissues.

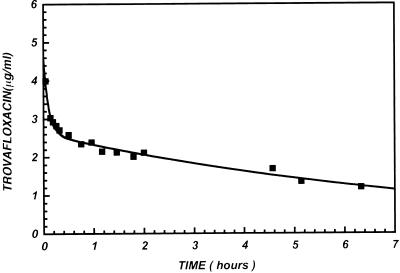

The time dependence of the distribution of trovafloxacin to the major organs of the body is also illustrated in Fig. 2. Figure 3 shows four representative PET images of the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, spleen, bowel, kidneys, muscle, and bone of human subjects at 90 min after infusion of [18F]trovafloxacin. These data indicate that [18F]trovafloxacin penetrates to a significant extent into all peripheral organs. For most of the tissues that were studied, high levels of trovafloxacin accumulation were reached by 10 min and the concentrations decreased only slightly over the remainder of the study. In the kidney, liver, lung, and myocardium, drug clearance was more rapid than in the other tissues. Particularly high peak concentrations (micrograms per gram) were achieved in the liver (35.06 ± 5.89), pancreas (32.36 ± 20.18), kidney (27.20 ± 10.68), lung (22.51 ± 7.11), and spleen (21.77 ± 11.33). From after the end of infusion to the conclusion of PET imaging, clearance of trovafloxacin from the circulation was well described by a biexponential function (Fig. 4): [trovafloxacin] = (2.43 ± 0.09)e−(0.097 ± 0.01)t + (0.60 ± 0.10)e−(2.80 ± 1.27)t, where t is time.

FIG. 3.

Representative PET images of human subjects injected with [18F]trovafloxacin. The area of maximum concentration on each image is represented as 100% on the color scale.

FIG. 4.

Mean blood clearance of trovafloxacin in 16 healthy subjects (12 males and 4 females), determined by direct radioactivity measurements. Results for individual subjects are not shown. The data acquired from the end of the infusion to the conclusion of the study were well described by a biexponential function.

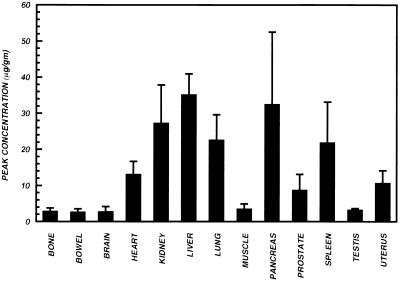

Figures 5 to 7 summarize the pharmacokinetic properties of trovafloxacin in all of the tissues that were studied. Since analysis of variance failed to reveal a significant main effect of sex on any of the pharmacokinetic parameters, the data for males and females were pooled.

FIG. 5.

Peak concentrations of trovafloxacin in the indicated tissues of healthy human subjects. For all tissues except the uterus, values are the means ± SEMs for 12 male subjects. For the uterus, data for the 4 female subjects are shown.

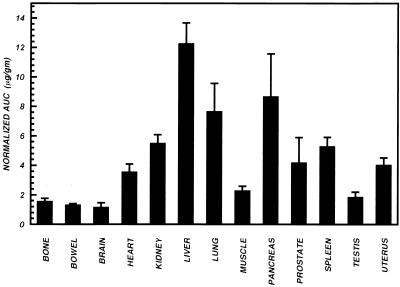

FIG. 7.

Normalized AUCs for trovafloxacin in various tissues of healthy human subjects. For all tissues except the uterus, values are the means ± SEMs for 12 male subjects. For the uterus, data for the 4 female subjects are shown.

Analysis of variance of the peak concentrations (Fig. 5) demonstrated a significant main effect of organ on the concentrations of trovafloxacin (F = 16.11; P < 0.0001). The trovafloxacin concentration in the liver was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in all other tissues except the pancreas and kidney. The concentrations in the kidney and lung were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those in the heart, blood, uterus, prostate, muscle, testis, bone, brain, and bowel. The concentration in the spleen was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those in the blood, uterus, prostate, muscle, testis, bone, brain, and bowel.

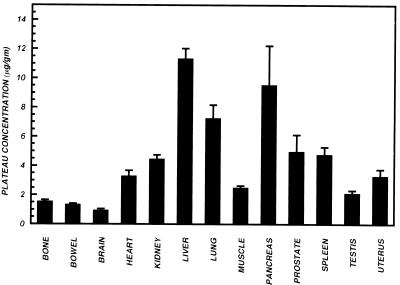

Analysis of variance of the plateau concentrations (Fig. 6) demonstrated a significant main effect of organ on trovafloxacin accumulation (F = 44.52; P < 0.0001). Trovafloxacin concentrations in the liver and pancreas were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those in all other tissues. The concentration in the lung was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in all other tissues except the liver and pancreas. The concentrations in the prostate, spleen, and kidney were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in the muscle, testis, blood, bone, bowel, and brain. The concentration in the heart was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those in the bone, bowel, and brain, and that in the uterus was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those in the bowel and brain.

FIG. 6.

Plateau concentrations of trovafloxacin in various tissues of healthy human subjects. For all tissues except the uterus, values are the means ± SEMs for 12 male subjects. For the uterus, data for the 4 female subjects are shown.

Analysis of variance of the normalized AUCs (Fig. 7) demonstrated a significant main effect of organ on trovafloxacin accumulation (F = 18.85; P < 0.0001). The trovafloxacin concentration in the liver was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in all other tissues, and that in the pancreas was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in all other tissues except the liver. The concentration in the lung was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in the prostate, uterus, heart, muscle, blood, testis, bone, bowel, and brain. The concentrations in the kidney and spleen were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in the muscle, blood, testis, bone, bowel, and brain. The concentration in the prostate was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than in the brain.

Very high trovafloxacin concentrations were measured in the gallbladder: peak concentration, 317.06 ± 140.48 μg/g; plateau concentration, 211.56 ± 30.36 μg/g; and AUC, 138.04 ± 29.73 μg/g. However, due to the thinness of the gallbladder wall and the limitations of PET resolution, it was not possible to differentiate between tissue-associated and intraluminal drug.

Although the concentration of trovafloxacin in pulmonary tissue measured directly by PET is low, this is due to the fact that PET measurements yield drug concentrations in micrograms per cubic centimeter of tissue. Since most tissues are of approximately unit density, concentrations measured by PET are similar to the results that would be expected from direct radioactivity measurements on excised tissues. In contrast, the density of the lung is approximately 0.26 ± 0.03 g/cm3 (16). When this correction is taken into account, the peak and plateau concentrations and normalized AUC of trovafloxacin in the lung are 22.07 ± 6.94, 3.05 ± 0.05, and 4.19 ± 0.55 μg/g, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The presence of three fluorine atoms in its native structure and the ability to prepare 18F-labeled drug by an exchange reaction make trovafloxacin an ideal drug for PET studies. Also, since during the first several hours after injection trovafloxacin undergoes minimal in vivo metabolism in humans, tissue and blood radioactivity measurements accurately reflect concentrations of intact drug (unpublished results). Thus, PET permits the precise noninvasive measurement of the concentration of drug over time in various tissues, including sites of infection. The drawbacks of this approach are the limited spatial resolution of PET measurements (tissue volumes of ∼1.0 cm3) and the short physical half-life of 18F, which limits the time frame of pharmacokinetic measurements to 8 to 10 h. For trovafloxacin, this constraint did not prevent the acquisition of detailed tissue pharmacokinetic data, previously for animals (2, 12) and now for humans. It should be pointed out, however, that PET measurements yield only total concentrations of drug per gram of tissue and cannot differentiate between intra- and extracellular concentrations.

The pattern of distribution of trovafloxacin in healthy human subjects is remarkably similar to the results of our previous PET measurements with another 18F-labeled fluoroquinolone, fleroxacin (15). As for [18F]fleroxacin, the uniform decreases in trovafloxacin concentrations in the kidney and liver are most probably related to the fact that these are clearance organs. Similarly, the rapidly decreasing concentrations of drug in the lung and muscle may be due to rapid equilibration in these organs. The low level of accumulation in bone is consistent with the proposed mechanism of metabolism of trovafloxacin via conjugation with minimal defluorination (unpublished results) and supports the utility of [18F]trovafloxacin prepared by exchange of 18F for 19F for pharmacokinetic studies (2).

The use of PET to study pharmacokinetics has many advantages over more conventional techniques. Although changes in drug concentrations in tissues could be determined by radioactivity measurements of excised tissues or quantitative autoradiography involving many animals, PET allows multiple measurements in the same subject at different times and in a variety of physiological or pathological states. A major advantage of PET is the quantitative nature of the measurement. Even more importantly, PET is the only noninvasive technique that can be used to measure tissue pharmacokinetics quantitatively in humans.

The concentrations of trovafloxacin achieved in the tissues of healthy humans appear promising in light of the sensitivities of a wide range of microorganisms to trovafloxacin. Thus, while the MIC90s for virtually all the Enterobacteriaceae and anaerobes are <0.5 μg/ml (9, 20, 21, 25, 33, 37, 46), peak concentrations of drug are well over 2 μg/g in all extracranial tissues. Considering these pharmacokinetic data in the context of the organisms causing infection at different anatomic sites, it appears that trovafloxacin should be especially useful in the treatment and prevention of surgical infection (particularly in the abdomen), gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary infection, urinary tract infection, and pulmonary infection, and it seems to hold promise in the treatment of infection at other sites as well. For example, whereas other fluoroquinolones have traditionally not been used in the treatment of meningitis, the trovafloxacin concentrations achieved in the brains of healthy subjects (peak concentration, ∼2.63 ± 1.49 μg/g; plateau concentration, ∼0.91 ± 0.15 μg/g) are well above the MIC90s for such important causes of central nervous system infection as S. pneumoniae (MIC90 of <0.2 μg/ml), Neisseria meningitidis (MIC90 of <0.008 μg/ml), and Haemophilus influenzae (MIC90 of <0.03 μg/ml) (8, 9, 33, 26, 43). As the occurrence of resistance to drugs such as penicillin and ampicillin becomes more widespread, this property of trovafloxacin could become quite valuable clinically.

In summary, the promise of PET imaging for noninvasive quantification of the tissue distribution of trovafloxacin, an important highly potent broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone, suggested in earlier animal studies (2, 12), has been established in the present studies with human volunteers. At doses of drug that are currently used to treat clinical infection, effective concentrations of trovafloxacin are delivered to all tissues, including those in the central nervous system. The noninvasive nature of the technique as well as the reproducibility of the results will permit future studies of the distribution of trovafloxacin to tissue sites of infection in humans, permitting the study of the correlation between therapeutic efficacy and drug distribution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a grant from Pfizer Central Research, Groton, Conn.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azoulay-Dupus, E., J. P. Bedos, E. Valee, and J. J. Pocidalo. 1991. Comparative activity of fluorinated quinolones in acute and subacute Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia models: efficacy of temafloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 28(Suppl. C):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Babich J W, Rubin R H, Graham W A, Wilkinson R A, Vincent J, Fischman A J. 18F-labeling and biodistribution of the novel fluoro-quinolone antimicrobial agent, trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:995–998. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Thornsberry C, McLaughlin J C, Jenkins S G, Hardy D J, Allen S D. Methods of measuring susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria to trovafloxacin, including quality control parameters. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:676–678. doi: 10.1007/BF01691158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowker K E, Wootton M, Holt H A, Reeves D S, MacGowan A P. The in-vitro activity of trovafloxacin and nine other antimicrobials against 413 anaerobic bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:271–281. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Child J, Andrews J, Boswell F, Brenwald N, Wise R. The in-vitro activity of CP 99,219, a new naphthyridone antimicrobial agent: a comparison with fluoroquinolone agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:869–876. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coque T M, Singh K V, Murray B E. Comparative in-vitro activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against gram-positive cocci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1011–1016. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duncan D B. Multiple range tests and multiple F-tests. Biometrics. 1955;11:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliopoulos G M, Klimm K, Eliopoulos C T, Ferraro M J, Moellering R C. Program and abstracts of the 32nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. In vitro activity of CP-99,219, a new fluoroquinolone, against clinical isolates of gram-positive bacteria, abstr. 752; p. 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eliopoulos G M, Klimm K, Eliopoulos C T, Ferraro M J, Moellering R C., Jr In vitro activity of CP-99,219, a new fluoroquinolone, against clinical isolates of gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:366–370. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischman A J, Alpert N M, Livni E, Ray S, Sinclair I, Elmaleh D R, Weiss S, Correia J A, Webb D, Liss R, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled fluconazole in rabbits with candidal infections studied with positron emission tomography. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:1351–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischman A J, Alpert N M, Livni E, Ray S, Sinclair I, Callahan R J, Correia J A, Webb D, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled fluconazole in healthy human subjects by positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1270–1277. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischman A J, Babich J W, Alpert N M, Vincent J, Callahan R J, Correia J A, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled trovafloxacin in normal and E. coli infected rats and rabbits studied with positron emission tomography. Clin Microb Infect. 1997;3:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischman A J, Livni E, Babich J, Alpert N M, Liu Y-Y, Thom E, Cleeland R, Prosser B L, Callahan R J, Correia J A, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled fleroxacin in rabbits with Escherichia coli infections, studied with positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2286–2292. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischman A J, Livni E, Babich J W, Alpert N M, Bonab A, Chodosh S, McGovern F, Kamitsuka P, Liu Y-Y, Cleeland R, Prosser B L, Correia J A, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of [18F]fleroxacin in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and complicated urinary tract infection studied by positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:659–664. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischman A, Livni E, Babich J, Alpert N M, Liu Y-Y, Thom E, Cleeland R, Prosser B L, Correia J A, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Pharmacokinetics of [18F]fleroxacin in healthy human subjects studied by using positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents and Chemother. 1993;37:2144–2152. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler J F, Young A E. The average density of healthy lung. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1959;81:312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs P C, Barry A L, Brown S D, Sewell D L. In vitro activity and selection of disk content for disk diffusion susceptibility tests with trovafloxacin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:678–682. doi: 10.1007/BF01691159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girard A E, Faiella J A, Cimochowski C R, Brighty K E. Program and abstracts of the 33rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. In vivo oral activity of CP-99,219 in models of acute and localized infection, abstr. 1510; p. 395. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girard A E, Girard D, Gootz T D, Faiella J A, Cimochowski C R. In vivo efficacy of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219), a new quinolone with extended activities against gram-positive pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Bacteroides fragilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2210–2216. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gooding B B, Jones R N. In vitro antimicrobial activity of CP-99,219, a novel azabicyclo-naphthyridone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:349–353. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gootz T D, Brighty K E, Anderson M R, Schmieder B J, Haskell S L, Sutcliffe J A, Castaldi M J, McGuirk P R. In vitro activity of CP-99,219, a novel 7-(3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexyl) naphthyridone antimicrobial. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;19:235–243. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hook E W, III, Pinson G B, Blalock C J, Johnson R B. Dose-ranging study of CP-99,219 (trovafloxacin) for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 1996;40:1720–1721. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan A A, Slifer T, Araujo F G, Remington J S. Trovafloxacin is active against Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1855–1859. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilbourn M G, Welch M J. A simple low volume target for N-13 and F-18 production. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:120. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knapp J S, Neal S W, Parekh M C, Rice R J. In vitro activity of a new fluoroquinolone, CP-99,219, against strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:987–989. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liljequist B O, Hoffman B M, Hedlund J. Activity of trovafloxacin against blood isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Sweden. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:671–675. doi: 10.1007/BF01691157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livni E, Babich J, Alpert N M, Liu Y Y, Thom E, Cleeland R, Prosser B L, Correia J A, Strauss H W, Rubin R H, Fischman A J. Synthesis and biodistribution of 18F-labeled fleroxacin. Int J Nucl Med Biol. 1993;20:81–87. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(93)90139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livni E, Fischman A J, Ray S, Sinclair I, Elmaleh D R, Alpert N M, Weiss S, Correia J A, Webb D, Dahl R, Robeson W, Margouleff D, Liss R, Strauss H W, Rubin R H. Synthesis of 18F-labeled fluconazole and positron emission tomography studies in rabbits. Int J Nucl Med Biol. 1992;19:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(92)90007-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mann H J, Bitterman P B, Anderson A C, Teng R, Johnson A, Avery M, Vincent J. CP-99,219 penetration into human bronchial tissues and fluids following the administration of a single dose, abstr. F241. 1995. p. 155. . Abstracts of the In 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melnik, G., W. H. Schwesinger, R. Teng, L. C. Dogoto, and J. Vincent. Hepatobiliary elimination of trovafloxacin and metabolites following single oral doses in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Murphy S P, Cormican M G, Jones R N. Comparative antimicrobial activity and spectrum of CP-99,219, a novel fluoroquinolone, tested against ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates. Ir J Med Sci. 1995;164(4):271–273. doi: 10.1007/BF02967201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nau, R., T. Schmidt, K. Kaye, J. L. Froula, and M. G. Tauber. Quinolone antibiotics in the therapy of experimental pneumococcal meningitis in rabbits. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Neu H C, Chin N-X. In vitro activity of the new fluoroquinolone CP-99,219. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2615–2622. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.11.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.París M M, Hickey S M, Trujillo M, Shelton S, McCracken G H., Jr Evaluation of CP-99,219, a new fluoroquinolone, for treatment of experimental penicillin and cephalosporin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1243–1246. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roto Kops E H, Herzog H, Schmid A, Holte S, Feinendegen L E. Performance characteristics of an eight-ring whole body PET scanner. J Comput Assisted Tomogr. 1990;14:437–445. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199005000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin R H, Livni E, Babich J, Alpert N M, Liu Y Y, Cleeland R, Prosser B L, Thom E, Fischman A J. Tissue pharmacokinetics of fleroxacin in humans as determined by positron emission tomography. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1994;4:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Activity of CP 99,219 compared with those of ciprofloxacin, grepafloxacin, metronidazole, cefoxitin, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam against 489 anaerobes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2471–2476. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teng R, Harris S C, Nix D E, Schentag J J, Foulds G, Liston T E. Pharmacokinetics and safety of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219), a new quinolone antibiotic, following administration of single oral doses to healthy male volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:385–394. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teng R, Liston T E, Harris S C. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of trovafloxacin in healthy volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:955–963. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teng R, Tensfeldt T G, Liston T E, Foulds G. Determination of trovafloxacin, a new quinolone antibiotic, in biological samples by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1996;675(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tewson T J. Synthesis of fluorine-18 lomefloxacin, a fluorinated quinolone antibiotic. J Label Compd Radiopharm. 1993;32:145–146. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verbist L, Verhaegen J. In vitro activity of trovafloxacin versus ciprofloxacin against clinical isolates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:683–685. doi: 10.1007/BF01691160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visalli M A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Activity of CP 99,219 (trovafloxacin) compared with ciprofloxacin, sparfloxacin, clinafloxacin, lomefloxacin and cefuroxime against ten penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-resistant pneumococci by time kill methodology. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:77–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wexler H M, Molitoris E, Molitoris D, Finegold S M. In vitro activities of trovafloxacin against 557 strains of anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2232–2235. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wise R, Mortiboy D, Child J, Andrews J M. Pharmacokinetics and penetration into inflammatory fluid of trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:47–49. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfson J S, Hooper D C. Fluroquinolone antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:378–424. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]