To the Editor—The 2023 Duke-ISCVID (International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases) criteria, recently published in your journal, provide many new important aspects to the diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis (IE) [1]. The revised criteria keep the original format of the Duke criteria, including major imaging and major microbiology criteria, complemented with minor criteria [1–3]. Whereas methods for imaging have been revolutionized since the introduction of the Duke criteria in 1994 [2], the microbiological methods have developed but are still, in essence, the same. The more sophisticated imaging techniques have likely led to radically increased sensitivity and specificity as compared with the 1990s, whereas the sensitivity of the microbiological method remains high and the specificity remains low. This development should, in our opinion, result in a more pronounced emphasis on the imaging modalities in the diagnostic criteria for IE.

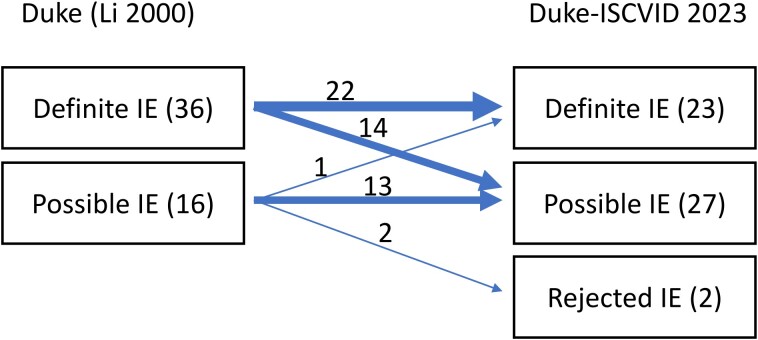

One of the changes in the 2023 Duke-ISCVID criteria is that Enterococcus faecium is no longer considered a “typical endocarditis pathogen” and thus 2 positive blood cultures with E. faecium are regarded as a minor criterion [1, 3]. In the previous version, non-nosocomial E. faecium bacteremia with unknown focus was considered as a typical endocarditis pathogen [3]. It is generally accepted that IE is rare in bacteremia with E. faecium [4, 5]. However, E. faecium can indeed cause IE and the consequence of the reclassification of the species is shown in Figure 1 with data from the Swedish Registry for Infective Endocarditis (SRIE) [6].

Figure 1.

Consequence of the Dukes-ISCVID 2023 reclassification of E.faecium on IE, data from the Swedish Registry for Infective Endocarditis 2008–2023. Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; ISCVID, International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases.

There were 7679 cases of patients treated for IE reported to the SRIE between 2008 and the present. Of these, 52 episodes (0.7%) were caused by E. faecium. Figure 1 demonstrates the consequences for the classification of these 52 cases by the proposed changes of the criteria. Importantly, in the 14 cases reclassified from definite IE to possible IE with the Duke-ISCVID criteria, 13 patients had vegetations demonstrated with echocardiography in conjunction with positive blood cultures with E. faecium. In 1 case, a patient with pacemaker vegetations was reclassified from possible to definite IE with the Duke-ISCVID criteria since pacemaker has been added as a minor criterion in the latter [1].

The sensitivity of the ISCVID-Duke criteria thus decreases when E. faecium is excluded from the “typical endocarditis pathogens.” The Duke-ISCVID criteria chose to include nosocomially acquired Enterococcus faecalis bacteremia with known focus as a major criterion, although IE is known to be rare in this condition [7]. The argument for including E. faecalis was that the sensitivity of the criteria increased [8].

Our observations on E. faecium endocarditis point to the fact that it does not matter if a bacterium is a common or a rare cause of IE when the patient has IE as determined by echocardiography and concomitant bacteremia. We propose that the diagnostic criteria for IE could be revised so that patients fulfilling major imaging criteria and having significant bacteremia, irrespective of species, should be regarded as definite IE. In cases with negative imaging, the propensity of the bacterium to cause IE should be considered as well as other minor criteria.

Contributor Information

Helena Lindberg, Division of Infection Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; Department of Infectious Diseases, Hospital of Halland, Halmstad, Sweden.

Ulrika Snygg-Martin, Department of Infectious Diseases, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute of Biomedicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; Head of Swedish Registry of Infective Endocarditis, Swedish Society of Infectious Diseases, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Andreas Berge, Unit of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Department of Infectious Diseases, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden.

Magnus Rasmussen, Division of Infection Medicine, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; Division for Infectious Diseases, Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden.

Notes

Financial support. M. R. reports grants or contracts unrelated to this work from Swedish Governmental Funds for Clinical Research. There was no funding for this study.

References

- 1. Fowler VG, Durack DT, Selton-Suty C, et al. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases criteria for infective endocarditis: updating the modified Duke criteria. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 77:518–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med 1994; 96:200–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30:633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pinholt M, Östergaard C, Arpi M, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics and 30-day mortality of enterococcal bacteraemia in Denmark 2006–2009: a population-based cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouza E, Kestler M, Beca T, et al. The NOVA score: a proposal to reduce the need for transesophageal echocardiography in patients with enterococcal bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:528–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berisha B, Ragnarsson S, Olaison L, Rasmussen M. Microbiological etiology in prosthetic valve endocarditis: a nationwide registry study. J Intern Med 2022; 292:428–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rasmussen M, Berge A. Revision of the diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis are needed—please do it thoroughly. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:2041–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dahl A, Fowler VG, Miro JM, Bruun NE. Sign of the times: updating infective endocarditis diagnostic criteria to recognize Enterococcus faecalis as a typical endocarditis bacterium. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:1097–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]