Abstract

Background and Objectives

This study aims to explore the association between hearing impairment (HI) and functional disability and to examine whether depression mediates this association.

Research Design and Methods

In the study, 11 335 individuals aged 45 years and older were analyzed from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. The study used logistic regression and Karlson/Holm/Breen’s method to examine the correlation between HI, depression, and functional disability. Functional disability was assessed using activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Results

HI was significantly associated with activities of daily living disability (odds ratio [OR] = 1.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.21–1.49) and instrumental activities of daily living disability (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.46–1.68). The mediated effect of depression accounted for 22.80% and 15.17% of the total effect of HI on activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living disability, respectively. Additionally, depression partially mediated the effects of HI on specific activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living tasks, including bathing (33.23%), toileting (27.50%), doing chores (37.36%), preparing meals (28.04%), shopping (25.81%), taking care of finances (11.82%), and taking medicine (12.71%).

Discussion and Implications

HI increased the likelihood of functional disability partially through depression in middle-aged and older adults, suggesting that emphasizing the mental wellness of these people with HI is necessary to prevent impairments in physical function.

Keywords: Depression, Functional disability, Hearing impairment, Mediation analysis, Older adults

Translational Significance: Although hearing impairment is associated with depression and functional disability, few studies explore depression as a mediator between hearing impairment and functional disability. This study finds depression partially mediates the association between self-reported hearing impairment and functional disability, affecting different functional abilities of senior adults through depression. Interventions targeting self-reported hearing impairment and depression are crucial in preventing functional disability, particularly regarding instrumental activities of daily living among older adults.

Disability in older adults has received considerable attention and interest over the last few decades (1). The report on disability from World Health Organization (WHO) showed that 46.1% of older adults in the world (over 60 years of age) live with disability and the number is rising in parallel with the accelerated world aging process. As one of the countries with the largest aging population in the world, China has more than 42 million older adults (2). Some meta-analyses have shown that the pooled prevalence rate of disability in China is over 20% (3). WHO predicted that the number of older adults in China with disabilities will increase to 66 million by 2050 (4). According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), disability is the sum of impairments, activity limitations, or participation restrictions (5). As a key quality indicator for activity limitations, functional disability commonly refers to difficulty in basic activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental ADL (IADL) (6). ADL are commonly regarded as fundamental activities for independent living at home, such as bathing, dressing, and eating (7). IADL means more complex activities that require a higher level of autonomy and cognitive function, such as taking care of finances, shopping, and preparing meals (7).

Previous studies have identified many influencing factors related to functional disability, such as sensory impairment (8,9) and mental health status (10,11). Among these factors, hearing impairment (HI) has been suggested as an important factor affecting functional disability in older adults (12). A meta-analysis study demonstrated that older adults who experienced HI were more likely to report ADL difficulties than older adults without HI (12). Some longitudinal studies showed that self-reported HI may negatively affect older adults’ physical functioning independent of baseline health status (13,14). Moreover, several studies found that older adults with HI had more limitations to specific activities than those without HI, such as walking, getting in and out of bed, and managing medication (15). However, some studies did not find an independent association between HI and functional disability (16,17).

Depression, as one of the leading causes of disability in world, was suggested as a risk factor that predicts a functional decline and physical disability in older adults (18). Kalyani et al. found that participants reporting depression showed higher functional disability in mobility tasks, doing usual activities, and heavy work (19). A cohort of community-dwelling individuals over 8 years indicated that depression was associated with increased odds of disability onset after adjusting for confounders (18). The long-term depression may reduce one’s social engagement (20), personal interaction (21), and cognitive function (22,23). Such effects are likely to limit the independent implementation of ADL and IADL (24).

Depression also has been associated with HI in related theoretical or empirical studies (25–28). The gradual development of HI is significantly linked to the reduction of personal communication capability and socialization motivation and may be more prone to emotional disorder, thus, developing into depression (27,28). Some longitudinal studies reported that the risk of developing depression is substantial in nondepressed participants with self-reported hearing problems (26,29,30). However, other studies showed that objectively measured hearing loss, but not self-reported HI, was associated with depression (31).

To date, hearing impairment is known to be independently associated with depression and functional disability, but the relationship between self-reported HI, depression, and functional disability remains inconclusive. Moreover, the studies have not further demonstrated whether depression mediates the association between self-reported HI and functional disability. Therefore, this study aims to: (i) explore the association between HI and functional disability and (ii) examine whether depression has a mediating effect in the association between HI and functional disability.

Method

Data Source

This study used the data of China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2018. This national survey collected information on the health and aging status of adults aged 45 years and above in China, covering a variety of information regarding basic demographic characteristics, family structure, health status, health care, etc. (32). The baseline national wave of CHARLS is being fielded in 2011 and includes 17 708 individuals in 150 counties/districts and 450 villages and committees in 28 provinces (33). Follow-up surveys were conducted every 2–3 years. As of now, CHARLS has completed regular surveys in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2018.

The data used in this study were panel data extracted from 4 waves of CHARLS. After excluding samples with missing key variables, including self-reported hearing, depression, ADL, IADL, and confounding variables. This study finally included 11 335 participants who were followed up for all 4 waves. See Supplementary Figure 1 for details.

Variable Measures

Hearing impairment

HI was accessed by the following question: “How is your hearing?” Five options were given: (1) excellent, (2) very good, (3) good, (4) fair, and (5) poor. In accordance with previous study (30), HI was categorized into 2 categories: nonimpairment (“excellent, very good, and good”), HI (“fair, poor”).

Functional disability

Functional disability was assessed by ADL and IADL. Five items were measured for ADL, namely, dressing, eating, toileting, bathing, and getting out of the bed. Five items were measured for IADL, namely, preparing meals, shopping, doing chores, managing assets, and taking medicine. Each answer was divided into 4 responses as follows: (i) No, I do not have any difficulty; (ii) I have difficulty but can still do it; (iii) Yes, I have difficulty and need help; and (iv) I cannot do it. Consistent with Qian and Ren 2016 (34), disability in each item was defined as participants who reported having difficultly, needing help, or cannot (ie, having a response of 2, 3, or 4). Participants were entered into an ADL or IADL disability group if they reported one of the 5 items of ADL or IADL.

Depression

Depression was measured by the Centre for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale of 10 items (CES-D10). Respondents reported the frequency of occurrence of each item in the past week, and the frequency of each item was set to 0–3. The total score corresponding to the 10 items was 0–30. The higher the score was, the more severe the depression. According to recent studies, 10 as a cutoff point indicated good validity in identifying clinically significant depression (35,36). In this study, Participants were entered into a depression group if their CES-D10 score was more than 10.

Covariates

Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics and health-related variables. Gender (male, female), age (45–59, 60–75, 75+), marital status (married or cohabitating, single), education (illiterate, primary and middle school, high school, and above), location (urban, rural), and retirement (yes, no) and time (wave) were included in demographic characteristics. Smoking (yes, no), alcohol consumption (yes, no), chronic diseases (no, one disease, two, and more diseases), participation in social activities (yes, no), visual impairment (yes, no), the use of hearing aid (yes, no), and cognitive status (score) were considered health-related variables.

Statistical Analysis

First, the baseline characteristics of the participants according to hearing status were reported as percentages for categorical variables, and differences between groups were examined with the Chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Second, Baron and Kenny’s method for mediation analysis used the relationships between HI (X), depression (M), and functional disability (Y) (see Figure 1). Given the dichotomous nature of the functional disability in ADL and IADL and panel data of this study, binary logistic regression commands for panel data in Stata were used to examine the relationships of X, M, and Y, and the time variables were controlled. Third, the Karlson, Holm, and Breen (KHB) method is a general decomposition method that can effectively solve the scale problem related to the inseparability of estimation coefficients, through Monte Carlo simulation, the confounding percentage bias of the KHB method is smaller than other methods. The KHB logit model command for panel data was used to test the direct effect of HI (βDE), indirect effects (βIE) through depression, total effect (βtotal), and proportion of mediation (βIE/βtotal).

Figure 1.

Mediating analysis of hearing impairment, depression, and functional disability. ADL = activities of daily living; HI = hearing impairment; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. X indicates the independent variable (HI), Y indicates the dependent variable (ADL and IADL), and M indicates the mediator (depression). Mediating effect is considered if the condition is fulfilled as follows. First, X is associated with Y (path c). Second, X is associated with the M (path a). Third, M is associated with the Y after adjusting for X (path b). Finally, if the effect of X on Y is still significant when M was included in the model (path cʹ), partial mediation is considered if X is no longer significant, it is complete mediation.

All models were adjusted for covariates listed in the variable measurement section. All data were performed using STATA 16.0, and the cutoff value of statistical significance was p < .05 (2-sided).

Results

The participants’ baseline characteristics of demographic and health status are shown in Supplementary Table 1. A total of 11 335 respondents aged 45 years and above were included in this study. At baseline, 54.9% reported HI, 13.9% of participants reported ADL disability, 19.4% reported IADL disability, and 38.1% reported depression. Univariate analysis revealed significant differences prevalence of ADL disability and IADL disability in HI and depression. For covariates, hearing aid and retirement were not significant different within the ADL disability (p > .05) and IADL disability (p > .05).

The Pathway of Hearing Impairment, Depression, and Functional Disability

Figure 2 shows the path diagram of HI and ADL disability and specific activities based on the logistic regression. For path c, HI was significantly associated with ADL disability, bathing, and toileting (p < .001), but not significantly associated with getting out of bed, eating, and dressing (p > .05). For path a, it was found a significant association between self-reported HI with depression (p < .001). After controlling all covariates and HI, path b showed that the depression was independently related to ADL disability, getting out of the bed, bathing, eating, dressing, and toileting (p < .001). Finally, when controlled covariates and depression, HI was associated with ADL disability, bathing, and toileting (p < .001). According to Baron and Kenny’s method, depression may have a partial mediating effect on the associations among HI and ADL disability, bathing, and toileting.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression results of paths a, b, c, and cʹ for hearing impairment, depression, and activities of daily living disability. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; HI: hearing impairment; ADL: activities of daily living.

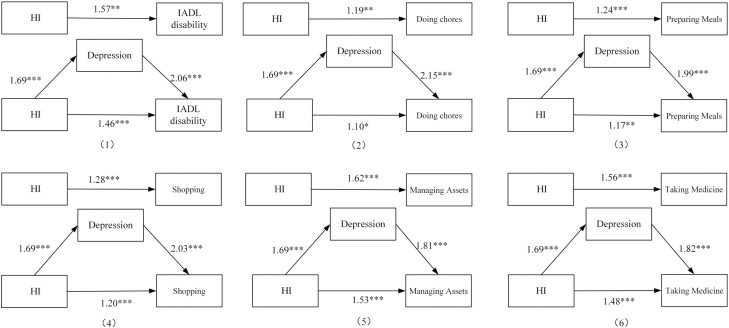

Figure 3 shows the path diagram of HI and IADL disability and specific activities based on the logistic regression. For path c, HI was significantly associated with IADL disability, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine (p < .001). For path a, it was found a significant association between self-reported HI with depression (p < .001). After controlling all the covariates and HI, path b showed that the depression was independently related to IADL disability, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine (p < .001). Finally, when covariates and depression were controlled, HI was still associated with IADL disability, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine (p < .001). According to Baron and Kenny’s method, depression may have a partial mediating effect on the associations among HI and IADL disability, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine.

Figure 3.

Logistic regression results of paths a, b, c, and cʹ for hearing impairment, depression, and instrumental activities of daily living disability. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; HI = hearing impairment.

Mediation of Depression of Hearing Impairment and Functional Disability

KHB mediation analysis further tested the mediating effect of depression. Tables 1 and 2 present the results of the direct effect, relative indirect effects through depression, total effect on functional disability and specific activities, and proportion of mediation. Table 1 shows that depression played a significant and partially mediating role in the relationship between HI and ADL disability, HI and bathing, and HI and toileting, respectively. Depression explained 22.80%, 33.23%, and 27.50% in the association of HI and ADL disability, bathing, and toileting, respectively.

Table 1.

Mediation Analyses of the Association Between Hearing Impairment and Activities of Daily Living Disability by Depression

| Variable | ADL Disability | Dressing | Eating | Getting Out of Bed | Bathing | Toileting | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | |

| Total effect | 1.34 (1.22,1.50) |

<.001 | 1.14 (0.96,1.36) |

.136 | 1.00 (0.76,1.32) |

.973 | 0.93 (0.76,1.15) |

.511 | 1.22 (1.08,1.39) |

.001 | 1.24 (1.08,1.42) |

.003 |

| Direct effect | 1.26 (1.14,1.40) |

<.001 | 1.07 (0.90,1.28) |

.432 | 0.96 (0.73,126) |

.763 | 0.89 (0.72,1.09) |

.252 | 1.14 (1.01,1.29) |

.034 | 1.17 (1.01,1.35) |

.032 |

| Indirect effect | 1.07 (1.06,1.08) |

<.001 | 1.06 (1.04,1.08) |

<.001 | 1.05 (1.02,1.07) |

<.001 | 1.05 (1.03,1.07) |

<.001 | 1.09 (1.05,1.08) |

<.001 | 1.06 (1.05,1.07) |

<.001 |

| Mediated (%) | 22.80 | NA | NA | NA | 33.23 | 27.50 | ||||||

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable; OR = odds ratio.

Table 2.

Mediation Analyses of the Association Between Hearing Impairment and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Disability by Depression

| Variable | IADL Disability | Doing Chores | Preparing Meals | Shopping | Managing Finance | Taking Medicine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | OR (95% CI) |

p Value | |

| Total effect | 1.57 (1.47,1.68) |

<0.001 | 1.20 (1.09,1.33) |

<.001 | 1.25 (1.14,1.39) |

<.001 | 1.28 (1.16,1.43) |

<.001 | 1.62 (1.49,1.77) |

<.001 | 1.57 (1.36,1.80) |

<.001 |

| Direct effect | 1.47 (1.38,1.57) |

<0.001 | 1.12 (1.01,1.24) |

.021 | 1.18 (1.07,1.31) |

.001 | 1.20 (1.09,1.34) |

<.001 | 1.53 (1.41,1.67) |

<.001 | 1.47 (1.28,1.70) |

<.001 |

| Indirect effect | 1.07 (1.06,1.08) |

<0.001 | 1.07 (1.06,1.08) |

<.001 | 1.07 (1.05,1.07) |

<.001 | 1.07 (1.06,1.08) |

<.001 | 1.06 (1.05,1.07) |

<.001 | 1.05 (1.05,1.01) |

<.001 |

| Mediated (%) | 15.17 | 37.36 | 28.04 | 25.81 | 11.82 | 12.71 | ||||||

Notes: CI = confidence interval; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; OR = odds ratio.

Table 2 shows a partially mediated effect of depression found in IADL disability and all specific activities, namely, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine, and depression explained 15.17%, 37.36%, 28.04%, 25.81%, 11.82%, and 12.71% in the association of HI and IADL disability, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine, respectively.

Discussion

To sum up, the findings outlined a high prevalence of self-reported HI (54.9% in baseline) and depression (over 35% in baseline) in middle- and old-aged Chinese. This is consistent with the figures calculated by some recent studies on middle-aged and older adults in China (37–39), and is much higher than the average level of low- and middle-income countries (40) and even the pool prevalence of older adults globally (41). This not only warns of the daunting challenges facing China in terms of the increasing burden of HI and depression, but also reminds us of the urgent need for more accessible and feasible methods in the context of a shortage of professional resources (36,42). This finding also showed that special attention should be paid to the hearing and mental health of middle-aged and older adults in China.

This study also found an independent association between self-reported HI and functional disability, and depression had a partially mediating effect on this association. Moreover, it was found that participants with HI reported restrictions in routine activities in ADL and IADL, such as bathing, toileting, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine. A partially mediating effect of depression has also been found in these associations. These results suggested that self-reported HI may affect functional disability through depression. It is speculated that the possible reasons for these results may be related to psychology, behavior, and cognition.

Hearing Impairment and Functional Disability

In this study, middle-aged and older adults with self-reported HI reported more difficulty performing ADL and IADL. Specifically, there was a significant correlation between self-reported HI and bathing and going to the toilet, although getting up, eating, and dressing was not associated with self-reported HI. Previous studies observed that older adults with hearing loss based on pure tone audiometry have more restrictions on getting in and out of bed than those without hearing loss (15), which is not found in this study. This may be due to different ways of hearing measurement. However, consistent with previous studies, we found that more complex IADL tasks, such as shopping, asset management, and drug therapy, were observed to be associated with HI compared with basic ADL (43). These findings suggest that self-reported HI may affect the different functional abilities of older adults and may limit their ability to perform complex functions.

According to previous studies, the decline of hearing may impair the maintenance of postural balance and change in gait and walking speed (44); thus, compared with simple self-care tasks, such as eating and dressing, older adults with HI may be restricted in movement activities that required more auditory cues (45). Further, degenerated hearing may affect cognitive and communication function. Brink and Stones found that HI was associated with impaired linguistic communication and lower levels of mood (46). As communication is an important aspect of daily living, especially when performing IADL tasks such as shopping and managing assets (47), it is not surprising that HI with its resulting communication problems would be associated with difficulty in performing these activities.

Mediation of Depression of Hearing Impairment and Functional Disability

A notable finding in this study was that depression was reflected as a mediator in the association between HI and functional disability. Our results concur with the finding of Ye et al. that self-reported HI and depression were significantly related to functional disability (48). Further, we found that depression as a mediator can partially explain the association between self-reported HI and functional disability. This finding implied that depression may be a potential mechanism underlying the relationship between HI and functional disability. According to previous studies, there are several possible reasons for the mediated effect of depression in the association between HI and functional disability (27,49).

First, the impaired hearing was correlated with psychological disorders and health status (50). Older adults with HI are prone to negative psychology and emotion because of communication obstacles, such as anxiety and loneliness (27), and even despair when they encounter difficulties in daily life, which has been linked with the crucial risk factors for depression. According to stress theory, mental health tends to be poor when a person is stimulated by stress (49). Meanwhile, older adults with HI may experience greater health burden and higher multimorbidity rates (36), and may even receive care from family members, which leads to an increased psychological burden and produces feelings of inferiority (51).

Second, older adults with self-reported HI have more negative life events and behavior than those without HI. Older adults with HI have limited participation in social activities due to the lack of necessary hearing information to communicate with others (20). Older adults with HI may cut down on personal interaction and be predisposed to reduce the amount of time spent outside their homes and participate in social activities (52). As a result, older adults who focus on individual social roles may see themselves as a burden, which may lead to feelings of depression, and further affect physical function disability.

In addition, cognitive impairment accompanied by HI-related depression could be a possible reason for the mediation effect of depression. Some scholars have suggested that HI-related depression may affect one’s cognitive function (53), such as attention, learning domains, and visuospatial ability (54), which may cause functional disability in older adults. A recent study indicated that when older adults suffer from depression and cognitive impairment (55), their ability to perform complex aspects of ADL and specific instrumental activity may be impaired (14). Our results also indicated that depression may impair functional performance in older adults with HI, usually in more complex activities related to cognition, such as managing assets and taking medicine. Therefore, HI may affect functional disability through depression.

The current study has several strengths including a large sample size from a prospective cohort and a high participation rate, consequently giving us a great potential to draw a reasonable conclusion. However, this study still has several limitations. First, based on the CHARLS, this study only used self-reported measures for hearing, depression, and function status, rather than objective measures. However, previous evidence also found that subjective hearing indicators and depression reports can better reflect individuals’ subjective perception of their psychological and physical condition (13). Second, in view of the high prevalence and low attention of HI, this study only focused on the participants’ hearing impairment and did not explore the association of visual impairment or other sensory impairment and functional disability. However, visual impairment has been enrolled in the analysis as a control variable to avoid potential confounding. Future studies can further link different sensory impairments to functional disability and examine the mediated effect of depression. Third, this study used balanced panel data and was not a time-lag analysis, so the results cannot explain the causality. However, balancing panel data has many advantages, such as controlling the impact of omitted variables and generating more accurate predictions. Despite these limitations, the results of this study could help us better understand the relationship between HI, functional disability, and depression.

Conclusion

Both HI and depression are associated with functional disability among middle-aged and older adults in China, and depression partially mediated the association between HI and functional disability. Moreover, HI and depression were found to be significantly correlated with specific complex tasks of ADL and IADL, including bathing, toileting, doing chores, preparing meals, shopping, managing assets, and taking medicine. Therefore, the government should take more responsibility for the early prevention of hearing impairment in middle-aged and older adults. Meanwhile, medical institutions should strengthen mental health construction when implementing intervention measures of HI, such as psychological counseling, social participation encouragement, and cognitive improvement, which may indicate changes in functional health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research used data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). The authors thank the CHARLS team for providing the data and all participants of CHARLS. The authors thank all the organizations that funded their research, which are National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72074086 and grant number 71673093), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, HUST, China (YCJJ20230689; 2022WKZDJC009).

Contributor Information

Dan Han, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Sangsang Li, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Yunyi Wu, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Jie Zhao, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Mei Zhang, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Hui Liao, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Ying Ma, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Chaoyang Yan, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Jing Wang, Department of Health Management, School of Medicine and Health Management, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China; The Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Science of Hubei Province and Institute for Poverty Reduction and Development, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China.

Funding

The work was supported by: National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72074086); National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 716730930); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number YCJJ20230689); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, HUST, China (grant number 2022WKZDJC009).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data Availability

Publicly available data sets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://charls.charlsdata.com/pages/data/111/zh-cn.html and the names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) also can be found at this link.

Author Contributions

D.H. conceived the idea, performed the data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. S.S.L., M.Z., and Y.Y.W. contributed to its design. L.H., J.Z., Y.M., and C.Y.Y. provided suggestions for the discussion of the manuscript. J.W. critically revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The biomedical ethics review committee of Peking University approved CHARLS, and all participants signed written informed consent. The approval number of the household survey is IRB00001052-11015. Respondents were given a statement explaining the purpose of the study, and all study participants had signed written informed consent prior to being investigated. The study protocol is performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines.

References

- 1. Saal S, Beutner K, Bogunski J, et al. Interventions for the prevention and treatment of disability due to acquired joint contractures in older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):373–382. 10.1093/ageing/afx026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization,World Bank. World report on disability. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564182

- 3. Zheng PP, Guo ZL, Du XJ, Yang HM, Wang ZJ.. Prevalence of disability among the Chinese older population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3). 10.3390/ijerph19031656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. China country assessment report on ageing and health. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241509312

- 5. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 2018. Accessed January 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

- 6. National Research Council Committee on National S, National Research Council Committee on P. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. (2009). Improving the Measurement of Late-Life Disability in Population Surveys: Beyond ADLs and IADLs, Summary of a Workshop, National Academy of Sciences. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yang R, Xu D, Wang H, Xu J.. Longitudinal trajectories of physical functioning among Chinese older adults: the role of depressive symptoms, cognitive functioning and subjective memory. Age Ageing. 2021;50(5):1682–1691. 10.1093/ageing/afab135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crews JE, Campbell VA.. Vision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older Americans: implications for health and functioning. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):823–829. 10.2105/ajph.94.5.823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. GBD 2019 Hearing Loss Collaborators. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England). 2021;397(10278):996–1009. 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00516-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo L, An L, Luo F, Yu B.. Social isolation, loneliness and functional disability in Chinese older women and men: a longitudinal study. Age Ageing. Jul 2021;50(4):1222–1228. 10.1093/ageing/afaa271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Armstrong NM, Deal JA, Betz J, et al. Associations of hearing loss and depressive symptoms with incident disability in older adults: health, aging, and body composition study. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(3):531–536. 10.1093/gerona/gly251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin TC, Yen MF, Liao YC.. Hearing loss is a risk factor of disability in older adults: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;85:103907. 10.1016/j.archger.2019.103907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liljas AEM, Carvalho LA, Papachristou E, et al. Self-reported hearing impairment and incident frailty in English community-dwelling older adults: a 4-year follow-up study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):958–965. 10.1111/jgs.14687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amieva H, Ouvrard C, Meillon C, Rullier L, Dartigues JF.. Death, depression, disability, and dementia associated with self-reported hearing problems: a 25-year study. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(10):1383–1389. 10.1093/gerona/glx250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gopinath B, Schneider J, McMahon CM, Teber E, Leeder SR, Mitchell P.. Severity of age-related hearing loss is associated with impaired activities of daily living. Age Ageing. 2012;41(2):195–200. 10.1093/ageing/afr155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cosh S, von Hanno T, Helmer C, Bertelsen G, Delcourt C, Schirmer H; SENSE-Cog Group. The association amongst visual, hearing, and dual sensory loss with depression and anxiety over 6 years: The Tromsø Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiat. Apr 2018;33(4):598–605. 10.1002/gps.4827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Armstrong NM, Vieira Ligo Teixeira C, Gendron C, et al. Associations of dual sensory impairment with incident mobility and ADL difficulty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(7):1997–2007. 10.1111/jgs.17764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF.. Racial differences on association of depressive symptoms with combined basic and instrumental activities of daily living. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(2):215–222. 10.1093/gerona/glt074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalyani RR, Ji N, Carnethon M, et al. Diabetes, depressive symptoms, and functional disability in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. J Diab Complications. 2017;31(8):1259–1265. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glass TA, De Leon CF, Bassuk SS, Berkman LF.. Social engagement and depressive symptoms in late life: longitudinal findings. J Aging Health. 2006;18(4):604–628. 10.1177/0898264306291017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H.. Association between social participation and instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older adults. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(10):553–561. 10.2188/jea.JE20150253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S.. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39–48. 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim JM, Chalem Y, di Nicola S, Hong JP, Won SH, Milea D.. A cross-sectional study of functional disabilities and perceived cognitive dysfunction in patients with major depressive disorder in South Korea: The PERFORM-K study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;239:353–361. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Connolly D, Garvey J, McKee G.. Factors associated with ADL/IADL disability in community dwelling older adults in the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(8):809–816. 10.3109/09638288.2016.1161848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gopinath B, Wang JJ, Schneider J, et al. Depressive symptoms in older adults with hearing impairments: the Blue Mountains Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1306–1308. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Amieva H, Ouvrard C, Meillon C, Rullier L, Dartigues JF.. Death, depression, disability, and dementia associated with self-reported hearing problems: a 25-year study. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(10):1383–1389. 10.1093/gerona/glx250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lawrence BJ, Jayakody DMP, Bennett RJ, Eikelboom RH, Gasson N, Friedland PL.. Hearing loss and depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2020;60(3):e137–e154. 10.1093/geront/gnz009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pronk M, Deeg DJ, Smits C, et al. Prospective effects of hearing status on loneliness and depression in older persons: identification of subgroups. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(12):887–896. 10.3109/14992027.2011.599871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nuesse T, Schlueter A, Lemke U, Holube I.. Self-reported hearing handicap in adults aged 55 to 81 years is modulated by hearing abilities, frailty, mental health, and willingness to use hearing aids. Int J Audiol. 2021;60(sup2):71–79. 10.1080/14992027.2020.1858237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu YG, Wang CC, Huang Q, Zhang L, Liu Y.. Association of vision and hearing status with depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Front Public Health. 2022;10:857307. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.857307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee AT, Tong MC, Yuen KC, Tang PS, Vanhasselt CA.. Hearing impairment and depressive symptoms in an older Chinese population. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39(5):498–503. 10.2310/7070.2010.090265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen X, Wang FS, Strauss J, Zhao Y.. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). (2019). Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging. ISBN: 978-3-319-69892-2. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao Y, Strauss J, Chen X, Wang Y, Gong J, Meng Q, Wang G, Wang H.. China health and retirement longitudinal study wave 4 user’s guide. National School of Development, Peking University. Accessed February 5, 2023. extension://bfdogplmndidlpjfhoijckpakkdjkkil/pdf/viewer.html?file=http%3A%2F%2Fcharls.pku.edu.cn%2Fen%2Fdata%2FUser2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qian J, Ren X.. Association between comorbid conditions and BADL/IADL disability in hypertension patients over age 45: Based on the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(31):e4536. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, et al. Association of audiometric age-related hearing loss with depressive symptoms among Hispanic individuals. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(2):132–139. 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yan C, Liao H, Ma Y, Xiang Q, Wang J.. Association among multimorbidity, physical disability and depression trajectories: a study of urban–rural differences in China. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(8):2149–2160. 10.1007/s11136-021-02807-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rong H, Lai X, Jing R, Wang X, Fang H, Mahmoudi E.. Association of sensory impairments with cognitive decline and depression among older adults in China. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):e2014186. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guan L, Liu Q, Chen D, Chen C, Wang Z.. Hearing loss, depression, and medical service utilization among older adults: evidence from China. Public Health. 2022;205:122–129. 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luo H, Li J, Zhang Q, et al. Obesity and the onset of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in China: evidence from the CHARLS. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):909. 10.1186/s12889-018-5834-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim AR, Park JH, Park HY.. Analysis of factors affecting depression in older adults in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9887. 10.3390/ijerph18189887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cai H, Jin Y, Liu R, et al. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J Psychiat. 2023;80:103417. 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang R, Chen Z, Zhou Y, Shen L, Zhang Z, Wu X.. Melancholy or mahjong? Diversity, frequency, type, and rural–urban divide of social participation and depression in middle- and old-aged Chinese: a fixed-effects analysis. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2019;238:112518. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mueller-Schotte S, Zuithoff NPA, van der Schouw YT, Schuurmans MJ, Bleijenberg N.. Trajectories of limitations in instrumental activities of daily living in frail older adults with vision, hearing, or dual sensory loss. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(6):936–942. 10.1093/gerona/gly155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen DS, Betz J, Yaffe K, et al. Health ABC study. Association of hearing impairment with declines in physical functioning and the risk of disability in older adults. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(5):654–661. 10.1093/gerona/glu207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dai L, Best V, Shinn-Cunningham BG.. Sensorineural hearing loss degrades behavioral and physiological measures of human spatial selective auditory attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(14):E3286–E3295. 10.1073/pnas.1721226115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brink P, Stones M.. Examination of the relationship among hearing impairment, linguistic communication, mood, and social engagement of residents in complex continuing-care facilities. Gerontologist. 2007;47(5):633–641. 10.1093/geront/47.5.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Albers MW, Gilmore GC, Kaye J, et al. At the interface of sensory and motor dysfunctions and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(1):70–98. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ye X, Zhu DW, Chen SY, He P.. The association of hearing impairment and its severity with physical and mental health among Chinese middle-aged and older adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):155. 10.1186/s12955-020-01417-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ma Y, Xiang Q, Yan C, Liao H, Wang J.. Relationship between chronic diseases and depression: the mediating effect of pain. BMC Psychiat. 2021;21(1):436. 10.1186/s12888-021-03428-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arlinger S. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss—a review. Int J Audiol. 2003;42(Suppl 2):2S17–2S20. 10.3109/14992020309074639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Z, Chen D, Pan T, Chen C, Guan L.. Hearing loss, depression and social participation of older adults: evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22(7):529–535. 10.1111/ggi.14413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mikkola TM, Polku H, Portegijs E, et al. Self-reported hearing is associated with time spent out-of-home and withdrawal from leisure activities in older community-dwelling adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(2):297–302. 10.1007/s40520-015-0389-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brewster KK, Hu MC, Zilcha-Mano S, et al. Age-related hearing loss, late-life depression, and risk for incident dementia in older adults. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76(5):827–834. 10.1093/gerona/glaa242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, et al. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiat. 2001;9(2):113–135. 10.1097/00019442-200105000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Powell DS, Brenowitz WD, Yaffe K, et al. Examining the combined estimated effects of hearing loss and depressive symptoms on risk of cognitive decline and incident dementia. J Gerontol Series B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(5):839–849. 10.1093/geronb/gbab194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available data sets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://charls.charlsdata.com/pages/data/111/zh-cn.html and the names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) also can be found at this link.