Abstract

This Account describes new reactions that have been developed in the Johnson laboratories at UNC Chapel Hill enabled by considerations of N–O bond cleavage. Three main case studies are highlighted: the metal-catalyzed electrophilic amination of O-acyl hydroxyl amines, multihetero-Cope rearrangements driven by O–N bond breakage, and merged dearomatization/N=O cycloadditions for the synthesis of complex 4-aminocyclohexanols such as those found in the natural product tetrodotoxin.

Keywords: amination, catalysis, sigmatropic reactions, total synthesis, tetrodotoxin, cycloadditions

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Exothermic reactions occur through the exchange of weaker bonds for stronger bonds; consequently, a key element in the design of new transformations is the obligatory accounting of sufficient driving force on the bond-breaking side of the thermodynamic ledger. Heteroatom–heteroatom bonds tend to be weaker than C–C, C–H, and C–heteroatom bonds and within this broad subset nitrogen–oxygen bonds have a long history of enabling a wealth of interesting reactivity in organic chemistry. The purpose of this Account is to describe several projects from our laboratories that have relied on reaction designs predicated on breaking relatively weak N–O bonds in a strategic manner.

2. Electrophilic Amination

The driving force for our laboratory’s first foray into weak bonds was the corresponding author’s interest in securing an independent academic appointment. A hastily assembled ‘third proposal’ was the least thought-through of the three and inspired little confidence in any of the students starting the fledgling group at UNC in 2001. It was not until Ashley Berman began graduate studies in 2002 that the PI was able to find a student willing to take the plunge on the idea (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

A screenshot from the corresponding author’s third job proposal

Our investigations began with the hypothesis that compounds containing weak N–X bonds could be useful reagents in the installation of amines on carbon scaffolds. This paradigm of ‘electrophilic amination’, in which an activated leaving group induces nitrogen atoms to function as electrophiles in an umpolung fashion, found early success in the synthesis of primary and tertiary amines.2 For example, Boche and co-workers reported that N,N-dialkyl-O-sulfonyl hydroxylamines 1 can be alkylated with organolithium and Grignard reagents in modest yields (Figure 1).3 Similar transformations were also accomplished under a catalytic regime: the Erdik and Narasaka laboratories showed that O-sulfonyl oximes 2 reacted with RMgX or RZnX reagents in the presence of Cu(I) salts. Subsequent hydrolysis resulted in the net delivery of primary amines in the form of a H2N(+) synthon.4,5 At the outset of our studies, there had been no examples of the direct catalyzed delivery of R2N(+) synthons via sp3-hybridized electrophiles.

Figure 1.

Historical development of electrophilic aminating reagents

Scheme 2.

Selected scope of Cu-catalyzed aminations of diorganozinc reagents

In contrast to the dearth of such electrophilic amination techniques, the Buchwald–Hartwig coupling of aryl (pseudo)halides and amines has become the state of the art for the synthesis of arylamines via nucleophilic amination.6 We believed that the amination of nonstabilized carbon nucleophiles held considerable promise as an alternative, complementary approach that could deliver high-value compounds under mild conditions.

Our initial attempts at umpolung C–N bond constructions began with N,N-dialkyl-N-chloroamines 3, easily prepared compounds that had seen minimal use in electrophilic aminations.2 Inspired by our colleague Jim Morken’s ‘matrixed’ approach to catalyst screening,7 Ashley Berman undertook an extensive screening of organometallic nucleophiles and transition-metal catalysts (Figure 1); unfortunately, the desired tertiary amine products were observed in unsatisfactory yields (10–20%). Ashley reasoned, based on observing a significant amount of C-nucleophile homocoupling, that N-chloroamines 3 were too oxidizing. Perhaps a less oxidizing reagent could retain the nucleofugal characteristics of the halide while inducing less homocoupling? We therefore treated O-acyl hydroxylamine derivatives 4, prepared in a single step from secondary amines and benzoyl peroxide, with PhZnX reagents in the presence of 1.25 mol% CuOTf and observed the formation of N-arylamines in reasonable yield. Simply switching to diorganozinc R2Zn·MXn reagents 5, prepared by transmetalation of the corresponding organolithium or Grignard reagents, dramatically increased the isolated yield, resulting in a general phenomenon as explored in Scheme 2. Under ligand-free copper-catalyzed conditions, various dialkyl anilines and tertiary amines 6 were synthesized in excellent yields after short reaction times.8 Heteroaryl (6b) and tert-alkyl (6e) motifs were well tolerated. Secondary alkylamines 6g–i, including those with extreme steric hindrance, could also be accessed by this chemistry, representing the previously unreported incorporation of a RHN(+) synthon. For example, N,N-tert-octyl-tert-butylamine 6i was isolated by distillation on 10 mmol scale in good yield. In the course of this study, we observed that other copper salts, including air-stable CuCl2, were equally competent at promoting the arylation of N,N-dialkyl-O-acyl hydroxylamines. We subsequently validated the scalability of the net process, beginning with morpholine and phenylmagnesium bromide, on multigram scale.9 The low reaction temperature, facile reagent synthesis, and low catalyst loading without the need for a supporting ligand offer a valuable complement to the extant palladium-catalyzed Buchwald–Hartwig couplings. In many cases, analytically pure products were obtained through a simple acid/base extractive workup.

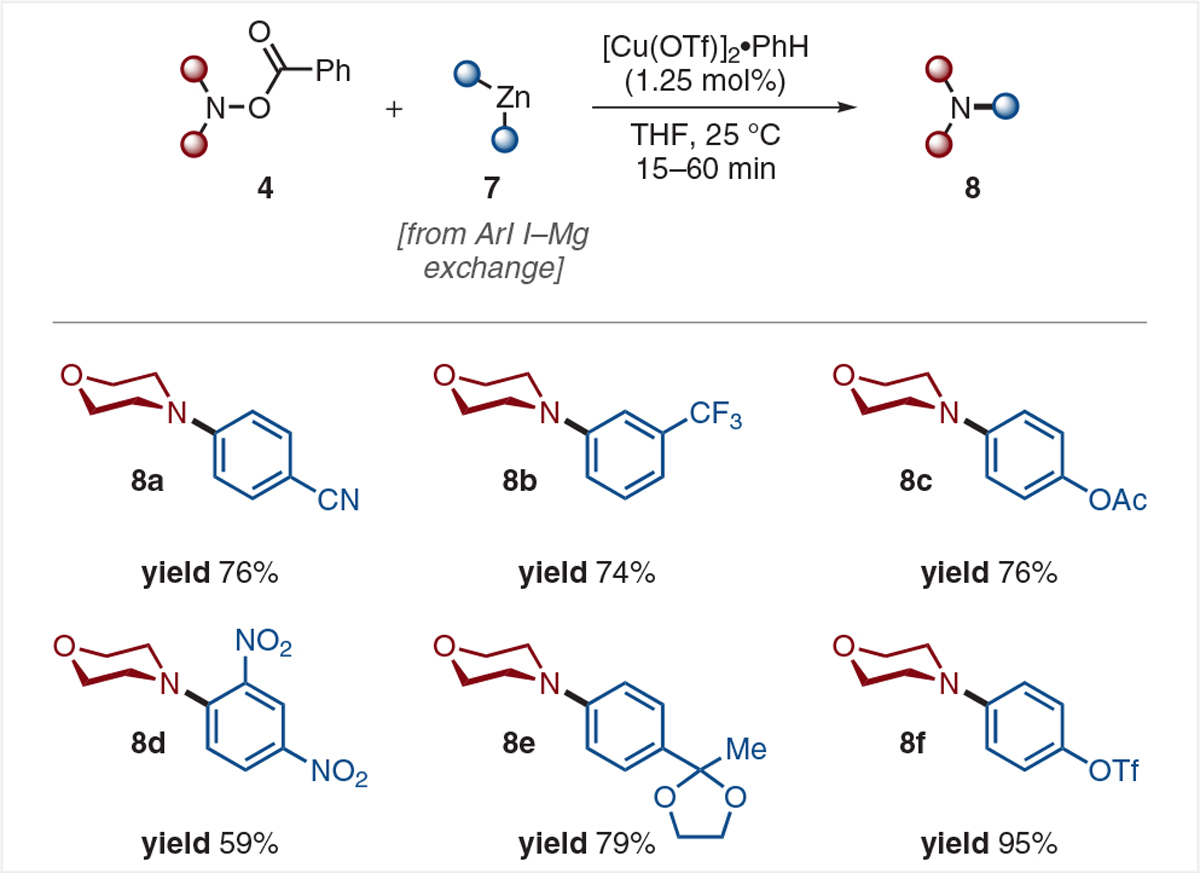

In hopes of expanding the functional group tolerance of this reaction, we applied I–Mg exchange sequence to the copper-catalyzed amination of diorganozinc reagents. As shown in Scheme 3, nitriles (8a), trifluoromethyl groups (8b), acetates (8c), nitro groups (8d), protected ketones (8e), and even triflates (8f) were used to obtain the corresponding tertiary amines in good to excellent yields.10 Both aryl units from the Ar2Zn reagent 7 could be delivered when using only 0.6 equivalents rather than the optimized 1.1 equivalents, albeit in somewhat reduced yield.

Scheme 3.

Electrophilic amination of functionalized diarylzinc reagents

Directed ortho metalation of arenes can be linked to transmetalation with ZnCl2 and the resulting diarylzinc species 9 can be treated with O-benzoyl hydroxylamines 4, without further isolation or purification, to effect electrophilic amination using catalytic CuCl2 (Scheme 4).11 N,N-Di-alkylamide (10a) and methoxymethyl (10c) directing groups perform well, while O-aryl carbamate (10d) and oxazoline (10b) motifs are somewhat less effective. A slower reaction rate was observed for these reactions, likely a result of increased zinc coordination. This sequence provides an alternative approach for substrates not previously accessible by Grignard formation, lithium–halogen exchange, or I–Mg exchange.

Scheme 4.

Directed ortho metalation/amination

The generality of transition metals to mediate electrophilic aminations extends beyond copper salts. We found that Ni(II)–bisphosphine complexes performed well when organozinc halides were employed, marking this as a divergent approach to the use of diorganozinc reagents as above. Using commercial and air-stable Ni(PPh3)2 with organozinc halides 11, prepared by transmetalation of the corresponding Grignards reagents with excess ZnCl2, amination of a suite of aryl, primary alkyl, and benzylic fragments proceeded smoothly (Scheme 5).12 Secondary and tertiary alkyl reagents were not tolerated here. Functionalized ArZnCl reagents 11, e.g. the precursors of tertiary amines 12, were prepared by I–Mg exchange of the aryl chloride followed by transmetalation and found to be well tolerated under these conditions. Separately, the aforementioned problems using N-chloroamines 3 were nicely solved by Jarvo and Barker, also through the application of Ni-based catalysts.13

Scheme 5.

Selected scope of Ni-catalyzed electrophilic amination

2.1. Mechanism

Matthew Campbell examined the mechanism by which this transformation occurs.14 Previous studies have suggested that Cu mediates C–N coupling through reductive elimination; however, there are multiple plausible mechanistic pathways that arrive at the requisite copper–amido complex 13. These include scenarios in which a copper complex could: (i) engage the O-benzoyl hydroxylamine in an SN2 reaction at nitrogen, (ii) undergo a non-SN2 oxidative addition process, or (iii) add through a radical pathway (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Possible mechanistic scenarios

To distinguish between these various possibilities, we first employed the enantiomerically enriched Grignard reagent 14 developed by Hoffmann and Hölzer15 to investigate various oxidations including electrophilic amination (Scheme 7a). Transmetalation of this reagent (ca. 84% ee) with zinc and subsequent electrophilic amination, followed by functional group interconversion, afforded acetamide 15 with approximately 9% racemization. Hoffmann previously reported sequential transmetalation of reagent 14 with zinc and copper followed by conjugate addition to mesityl oxide with only 6% racemization, comparable to our results. We therefore concluded that a polar mechanism is likely dominant, as any radical processes would result in significant racemization.

Scheme 7.

Mechanistic studies

To differentiate between SN2 displacement at nitrogen and a non-SN2 oxidative addition, we employed the endocyclic restriction test developed by Beak (Scheme 7b).16 When the system is forced into a six-membered ring, intramolecular SN2 displacement is forbidden due to the prohibitive build-up of strain in the 6-endo-tet transition state 18a. In contrast, the σ-bond complex 18b is not strained and therefore accessible prior to an intramolecular non-SN2 oxidative addition. An equimolar mixture of iodide 16 and the deuterated analogue 16-d14 was treated with i-PrMgCl at cryogenic temperatures to induce iodine–magnesium exchange. Sequential treatment with ZnCl2 and CuCl2, followed by TMS diazomethane, led to the formation of tertiary amine 17. MS analysis of the reaction mixture revealed a statistical mixture of 17-d0, 17-d4, 17-d10, and 17-d14, meaning that intermolecular amination led to the formation of crossover products. The transition state therefore likely has a large Cu–N–OBz bond angle (e.g., ca. 180°).

2.2. Broader Use

Gratifyingly, Berman and Campbell’s work helped O-acyl hydroxylamines to become indispensable reagents for the direct delivery of the R2N(+) and RHN(+) synthons in a wide range of catalytic applications throughout laboratories globally. While the full breadth of these transformations is beyond the scope of this Account and has recently been reviewed,17,18 a summation of key advances will be discussed. The scope of carbon nucleophiles was expanded to include alkyl19 and aryl boronates20,21 and silyl ketene acetals.22 The generation of reactive organometallic intermediates through C–H activation, either by directed metalation23 or Catellani reaction24,25 with concomitant incorporation of diverse nucleophiles, and their productive capture by C–N bond formation through reaction with R2N-OBz reagents comprises another fertile offshoot of Ashley Berman’s initial studies. Remarkable success has been achieved in the realm of olefin functionalization chemistry.26 For example, catalytically generated copper–hydride species can engage olefins to produce an intermediate alkyl cuprate that is then trapped by an N,N-dialkyl-O-acyl hydroxylamine to afford enantioenriched tertiary amines.18,27 Boryl cuprates have been shown to act similarly in a range of systems.18 Carbon nucleophiles derived from aryl boronates or diorganozinc species are also compatible with nickel-catalyzed olefin functionalization when using an aminoquinoline directing group.28,29 Fluoroamination,30 amino-oxygenation,31,32 and diamination33–35 of alkenes have all been shown to be viable catalytic reactions. That so many publications and distinct approaches have relied on these R2N-OBz species marks them as uniquely versatile ‘plug-and-play’ reagents for electrophilic amination across a wide range of substrates, catalysts, and reaction conditions. We will continue to watch with gratitude and appreciation as many more useful transformations will be invented as a result of these discoveries.

3. Multihetero-Cope Rearrangements

The total synthesis of biologically active, stereochemically dense natural products often provides an impetus for the development of new reactions. For example, Justin Malinowski and Stefan McCarver prepared bis(acetonide) 19 in 15 steps as part of a proposed route to pactamycin 20,36 a potent and universal inhibitor of peptidyl translocation in ribosomes. The complex stereotetrad required elaboration of a methylene ketone to a trans-1,2-diamine in order to complete the synthesis and we saw an opportunity to expand on the available methodologies (Scheme 8). In response to our need to convert an α-methylene ketone into a 1,2-diamine, we were attracted to a report by Coates and Cummins on the use of N-alkyl-N-acetoxyenamines in multihetero [3,3] rearrangements driven by the cleavage of a weak N–O bond to provide α-acyloxy carbonyl compounds.37,38 Justin Malinowski and Ericka Malow proposed that treatment of ketonitrones 21 with imidoyl chlorides 22 would set up a facile multihetero-Cope rearrangement to provide protected α-amino imines 2439 species that we hypothesized could be easily cleaved to provide the parent α-amino ketones (Scheme 8) or reduced to 1,2-diamines, as in pactamycin 20.

Scheme 8.

Paradigmatic approach to the synthesis of α-amino-imines via multihetero-[3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements

In practice, when aryl ketonitrone 25 was treated with Cbz-protected trifluoromethyl imidoyl chloride 26 and a mild organic base, full consumption of the substrate was observed but enediamide 27 was observed instead of the expected α-amino carbonyl (Scheme 9).40 We proposed that the following a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement, deprotonation of the acidic α-proton of imine 28 facilitated a stepwise 1,4-trifluoroacetyl migration/proton transfer sequence. The resulting enediamides were generated exclusively as the (Z)-isomer in moderate yields, although a propiophenone-derived substrate 27b showed inverted selectivity as a result of increased A1,3-strain from the methyl substituent.

Scheme 9.

Selected aryl nitrone scope in multihetero-Cope rearrangements

A divergent outcome was observed when cyclic alkyl nitrones 29 were deployed. Deprotonation of the more sterically accessible α-proton of Cope product 31, a feature that was not present in the above scenario, led to α′-carbamoyl enamides 30 in moderate yields (Scheme 10). Chirality transfer from a nitrone derived from (S)-α-methyl benzylamine was poor (30b) and low diastereostereoselectivity was observed when a 4-tert-butylcyclohexanone-derived nitrone was used as a substrate (30d). Intriguingly, cyclohexenone-derived nitrone 29e provided cis-β′-chloro-α′-carbamoyl enamide 30e through incorporation of the chloride byproduct. In support of our original conceit, deprotection of the enamide motif was achieved under mild conditions to afford α-amino ketone 32 in excellent yield.

Scheme 10.

Selected scope and deprotection of cyclic/alkyl nitrones

In follow-up work from our group, Sam Bartlett and Kimberly Keiter sought to apply a Coates/Cummins-type [3,3] rearrangement to nitrones derived from α-keto esters.41 In particular, fully substituted variants lacking acidic β-protons should not be susceptible to second-stage deprotonation/acyl transfer events and would result in the formation of α-hydroxylated species. We again sought to leverage weak N–O bonds to drive a sigmatropic rearrangement to provide β-benzyloxy-α-imino esters (Scheme 11).

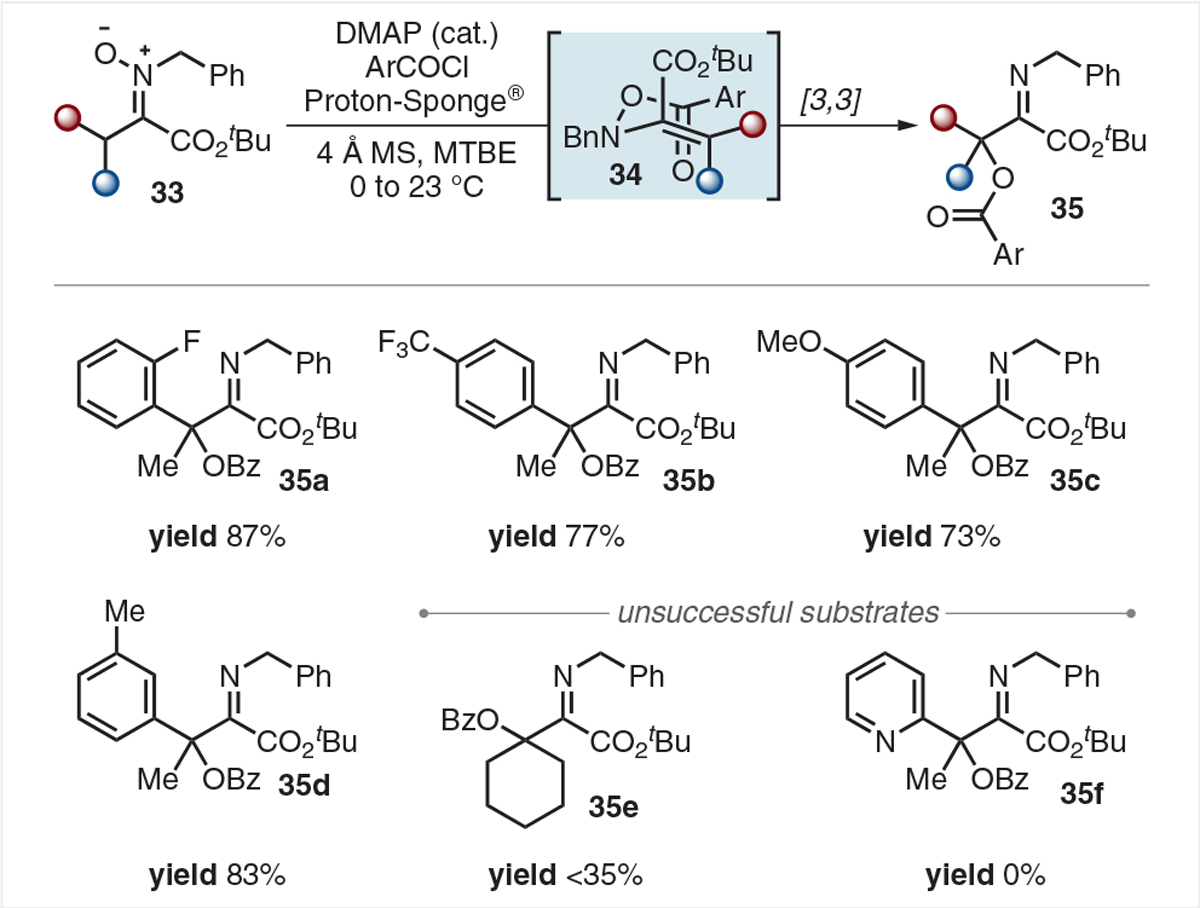

Scheme 11.

Selected scope of fully substituted β-benzyloxy-α-imino esters

Using DMAP as a nucleophilic catalyst and Proton-Sponge® as mild organic base, α-keto ester derived nitrones 33 were treated with benzoyl chlorides to generate O-benzoyl-N-oxyenamines 34 which spontaneously underwent a multihetero [3,3] rearrangement. The resulting β-oxyben-zoylated imines 35a–d were obtained in good to excellent yields. Multiple side reactions and instability to purification problematized the cyclohexyl derivative 35e, while pyridyl substrate 35f was completely unreactive.

4. Progress toward a Total Synthesis of (−)-Tetrodotoxin

In the cases described above, preinstallation of N–O bonds facilitated functionalization of diverse substrates; however, a reaction that forges carbon–nitrogen and carbon–oxygen bonds while retaining a nitrogen–oxygen bond not only introduces dense functionality in short order, but also allows for downstream modifications of complex scaffolds. This reaction manifold encompasses nitrone [3+2]42 and nitroso [4+2] cycloadditions,43 among others. We were particularly attracted to the requisite syn-facial selectivity of such cycloadditions as a pathway to stereospecifically install two distinct heteroatomic groups. The application of this strategy could immensely simplify a retrosynthesis of the neurotoxin (−)-tetrodotoxin (TTX) 36.

As a potent and densely functionalized bioactive molecule, TTX 36 has been the subject of immense synthetic study for the past 50 years, efforts which have been reviewed previously.44–46 Our approach began with the common conceptual target ‘tetrodamine’ 37, in which the caged dioxaadamantyl ortho-acid has been hydrolyzed and the cyclic guanidinium motif has been cleaved with formal loss of a carbodiimide equivalent (Scheme 12). We can now clearly point to the deeply embedded syn-C6,8a-aminocyclohexnaol substructure which we targeted for installation by an acyl nitroso Diels–Alder cycloaddition. As the only two fully substituted stereogenic centers present in TTX, significant effort has been made to effect their selective formation; however, our approach would simultaneously and stereospecifically create both new bonds and would directly intercept dienones 38 which are themselves prepared from feedstock aromatic starting materials 39.

Scheme 12.

Retrosynthetic analysis of (−)-tetrodotoxin

Initially, we thought that oxidative remodeling of an achiral aromatic precursor could be initiated by Adler oxidation of salicyl alcohols 39 to generate spiroepoxydienones 42. In practice, Steffen Good and Robert Sharpe found that this pairwise generation of mutually reactive species facilitated the desired [4+2] cycloaddition while suppressing homodimerization of the carbocyclic substrates and outcompeting deleterious decomposition of the highly reactive acyl nitroso species (Equation 1).47 Optimization of a one-pot reaction of 4-chloro-2-salicyl alcohol 39a and Cbz-hydroxylamine 40 under various conditions revealed that (1) water was essential for promoting the Adler oxidation; (2) excess water facilitated the undesired reduction of spiroepoxydienone 42 in the presence of acyl nitroso species; and (3) cycloreversion and recombination of the Diels–Alder adducts 41 occurred at higher reaction temperatures, as supported by crossover studies. Taken together, we settled on a two-phase CH2Cl2/water solvent system in the presence of a phase-transfer catalyst at 0 °C, followed by brief thermal equilibration at 30 °C to provide the desired tricyclic oxazinanone cycloadducts 41 in good yield and high diastereoselectivity. A selected scope can be found in Scheme 13.

Scheme 13.

Scope of the one-pot oxidation dearomatization/[4+2] cycloaddition

Equation 1.

Optimization of a one-pot Adler oxidation/acyl nitroso Diels–Alder cycloaddition

We next evaluated the manifold synthetic opportunities for these cycloadducts on the basis of the four distinct ‘addressable’ functional groups present: (1) ketone; (2) epoxide; (3) disubstituted alkene; and (4) oxazinane, as a latent amino alcohol (Scheme 14). Reduction of cycloadduct 41d with NaBH4 provided epoxyalcohol 42 as a mixture of diastereomers, while epoxidation afforded bis(oxirane) 43 as a single product. When cycloadduct was treated with m-CP-BA, a vinylogous Baeyer–Villiger oxidation occurred, yielding fused lactone 44 in good yield. Condensation of the ketone with hydroxylamine to provide epoxyoxime 45 facilitated a reductive fragmentation, unveiling primary alcohol 46 and providing important precedent for future applications toward TTX 36. We also found that the epoxide could be opened in the presence of bromodimethylsulfonium bromide to provide bromohydrin 47. Dihydroxylation of the alkene present in cycloadduct 41d proceeded with exquisite diastereoselectivity, providing diol 48 in the same stereochemistry present in ‘tetrodamine’ 37. Subsequent hydrogenolysis of the benzyloxycarbonyl protecting group and oxazinane reduction occurred with concomitant epoxide opening to afford the highly oxygenated cyclohexanone 49 in good yield. These successful experiments prompted us to continue our approach to tetrodotoxin 36 and showcase the breadth of chemistry that can be performed on functionalized heterocycloadducts.

Scheme 14.

Chemoselective modification of tricyclic spiroepoxyox-azinanones

We therefore required a tetrasubstituted phenol that could be parlayed through the aforementioned sequence towards TTX 36. Monosilyl-protected salicyl alcohol 50 was prepared from commercially available 2,3,6-trimethylphenol in five steps. Two-pot biphasic Adler oxidation/acyl nitroso Diels–Alder cycloaddition afforded cycloadduct 51 in good yield as a single diastereomer (Scheme 15a). As above, alkene dihydroxylation proceeded in excellent diastereoselectivity and enabled hydrogenolytic oxazinane cleavage of diol 52 to provide epoxylactol 53 in good yield, following spontaneous cyclization of the C9 alcohol into the C5 ketone.

Scheme 15.

Summary of first-generation route toward (±)-TTX

Work on the attempted elaboration of these materials to TTX is briefly summarized below (Scheme 15b).48 Triol 52 was protected and cyclized to generate oxazolidinone 54. We hoped to leverage the well-known reductive openings of epoxyketones with SmI2 to generate β-hydroxyketones. In practice, treatment with SmI2 at cryogenic temperatures yielded the desired ring opened adduct 55 as a single diastereomer. Unfortunately, the oxazinane N–O bond could not be cleaved to provide amino alcohol 56 despite repeated attempts. We next addressed the installation of the last carbon needed to complete the skeleton of TTX 36 in the hopes that other congeners might exhibit greater success in the epoxide opening (Scheme 15c). Tetrol 53 was converted to C10 glycolate 57 by a nine-step sequence and treated with SmI2 at room temperature to provide iodohydrin 58. Unfortunately, this material could not be parlayed into a complete synthesis of (±)-tetrodotoxin 36 via ‘tetrodamine’ 37.

Given the many successes and drawbacks of the route outlined above, one of us (J.G.R.) sought to evaluate a distinct approach in which a different C4a aldehyde surrogate was employed.49,50 This second-generation approach is marked by the use of a dimethyl ketal 59 as a latent ketone, enabling us to leverage prior results on the nitroso Diels–Alder cycloadditions of masked ortho-benzoquinones,51,52 versatile intermediates in the synthesis of complex natural products derived from phenolic feedstocks such as guaiacol 60 (Scheme 16a).53 We synthesized diene 61 in ten steps from 2-bromophenol. After extensive optimization, we found that an aerobic Cu(II)-catalyzed system led to the efficient generation of an acyl nitroso species54,55 with concomitant cycloaddition (Scheme 16b). Cycloadduct 63 was isolated in good yield and diastereoselectivity and was quickly subjected to dihydroxylation, which in this case required the in situ generation of highly oxidizing RuO4.56

Scheme 16.

Development of a second-generation approach to (±)-TTX

We attempted to affect the homologation at C4a, thereby validating our choice to switch to a different diene precursor but were stymied by the steric hindrance of the adjacent fully substituted center on ketone 65 (Scheme 17). Attempts to install a protected guanidine subunit on lactone 67 were met with failure for similar reasons. Perhaps the most intriguing results occurred when tetrol 64 was directly subjected to hydrogenolysis. Reductive cleavage of the N–O bond set off a cyclization cascade which saw the spontaneous formation of a bridging lactol and a lactone, as supported by an X-ray crystallography experiment. Unfortunately, we were again unable to functionalize the resultant neopentylic primary amine 69.

Scheme 17.

Attempted homologations and guanidinylations

Taken together, these results highlight the power of concomitantly installed nitrogen and oxygen heteroatoms to facilitate the synthesis of complex molecules and unveil unexpected reactivity. The low-lying N=O LUMO facilitates cycloaddition in a highly functionalized environment, and the derived oxazinanone functions as an effective surrogate for the most challenging stereochemical feature of TTX 36: the 1,4-syn-aminocyclohexanol. Whereas prior work in our group using N–O bonds focused on C–N bond formation, in this instance hydrogenolysis of the weak N–O bond is the enabling step for revealing the requisite amine and alcohol functions. With the phenol → bicyclic oxazinanone → amino cyclohexanol sequence now established in two separate contexts by us, the extant challenge to be solved involves the strategic packaging of the aromatic precursor to simplify the generation of the needed C4a aldehyde or its equivalent.

5. Conclusion

This Account has presented a diverse array of projects from our laboratory focused on complexity building reactions based on the chemistry of weak N–O bonds. Driven by the thermodynamic driving force provided by breaking these weak bonds in exchange for stronger ones, we have enjoyed success in developing organometallic couplings, sigmatropic rearrangements, and cycloaddition reactions. An unexpected but gratifying aspect of these studies has been the widespread adoption of O-acyl hydroxylamines as versatile reagents for the delivery of R2N(+) synthons to a diverse range of organometallic intermediates. The continued exploration of N–O bond chemistry may continue to yield useful new transformations for the community.

Funding Information

The project described was supported by award no. R35 GM118055 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Biographies

Biographical Sketches

Jacob G. Robins received his BSc in chemistry with honors from the College of William & Mary in 2016, where he conducted research with Prof. Jonathan R. Scheerer. He completed his doctoral studies with Prof. Jeffrey S. Johnson at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2021, during which time he pursued the total synthesis of (−)-tetrodotoxin. He is currently a postdoctoral associate with Prof. Scott J. Miller at Yale University.

Jeffrey S. Johnson received his BSc in chemistry from the University of Kansas in 1994 with highest distinction and honors in chemistry. He was a graduate student at Harvard University as an NSF Graduate Fellow in the laboratories of Prof. David A. Evans, receiving his PhD in 1999. He conducted postdoctoral research at the University of California at Berkeley from 1999 to 2001 as an NIH Postdoctoral Fellow under the direction of Prof. Robert G. Bergman. He joined the faculty of the Department of Chemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2001 and since 2014 has held the A. Ronald Gallant Distinguished Professorship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- (1).Current address: Robins Jacob G., Department of Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8107, USA. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Erdik E; Ay M Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Boche G; Mayer N; Bernheim M; Wagner K Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 687. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Tsutsui H; Hayashi Y; Narasaka K Chem. Lett. 1997, 26, 317. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Erdik E; Ay M Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem. 1989, 19, 663. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ruiz-Castillo P; Buchwald SL Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Taylor SJ; Morken JP J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 12202. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Berman AM; Johnson JS J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Berman AM; Johnson JS Org. Synth. 2006, 83, 31. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Berman AM; Johnson JS J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Berman AM; Johnson JS J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Berman AM; Johnson JS Synlett 2005, 1799. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Barker TJ; Jarvo ER J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Campbell MJ; Johnson JS Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hoffmann RW; Hölzer B J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Beak P Acc. Chem. Res. 1992, 25, 215. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Mohite SB; Bera M; Kumar V; Karpoormath R; Baba SB; Kumbhar AS Top. Curr. Chem. 2022, 381, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hirano K; Miura M J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Rucker RP; Whittaker AM; Dang H; Lalic G J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Rucker RP; Whittaker AM; Dang H; Lalic G Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Matsuda N; Hirano K; Satoh T; Miura M Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Matsuda N; Hirano K; Satoh T; Miura M Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yoo EJ; Ma S; Mei T-S; Chan KSL; Yu J-Q J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Dong Z; Dong GJ Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Dong Z; Lu G; Wang J; Liu P; Dong G J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wu Z; Hu M; Li J; Wu W; Jiang H Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Liu RY; Buchwald SL Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kang T; Kim N; Cheng PT; Zhang H; Foo K; Engle KM J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).van der Puyl VA; Derosa J; Engle KM ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 224. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Feng G; Ku CK; Zhao J; Wang Q J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hemric BN; Chen AW; Wang Q J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hemric BN; Shen K; Wang Q J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Peterson LJ; Kirsch JK; Wolfe JP Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Shen K; Wang Q Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chen J; Zhu Y-P; Li J-H; Wang Q-A Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Malinowski JT; McCarver SJ; Johnson JS Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Cummins CH; Coates RM J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 2070. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Tabolin AA; Ioffe SL Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lantos I; Zhang W-Y Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 5977. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Malinowski JT; Malow EJ; Johnson JS Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Bartlett SL; Keiter KM; Zavesky BP; Johnson JS Synthesis 2019, 51, 203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Confalone PN; Huie EM In Organic Reactions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, 2004, 1. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Carosso S; Miller MJ Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Makarova M; Rycek L; Hajicek J; Baidilov D; Hudlicky T Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Murakami K; Toma T; Fukuyama T; Yokoshima S Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Konrad DB; Rühmann K-P; Ando H; Hetzler BE; Strassner N; Houk KN; Matsuura BS; Trauner D Science 2022, 377, 411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Good SN; Sharpe RJ; Johnson JS J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Good S Dissertation 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Robins JG; Johnson JS Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Robins JG Dissertation 2021. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lin K-C; Liao C-C Chem. Commun. 2001, 1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Shimizu H; Yoshimura A; Noguchi K; Nemykin VN; Zhdankin VV; Saito A Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018, 14, 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Roche SP; Porco JA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Chaiyaveij D; Cleary L; Batsanov AS; Marder TB; Shea KJ; Whiting A Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Frazier CP; Engelking JR; Read de Alaniz J J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Plietker B; Niggemann M J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]