Abstract

Context:

Emotion regulation by the physician can influence the effectiveness of serious illness conversations. The feasibility of multimodal assessment of emotion regulation during these conversations is unknown.

Objective:

To develop and assess an experimental framework for evaluating physician emotion regulation during serious illness conversations.

Methods:

We developed and then assessed a multimodal assessment framework for physician emotion regulation using a cross-sectional, pilot study on physicians trained in the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG) in a simulated, telehealth encounter. Development of the assessment framework included a literature review and subject matter expert consultations. Our predefined feasibility endpoints included: an enrollment rate of ≥60% of approached physicians, >90% completion rate of survey items, and <20% missing data from wearable heart rate sensors. To describe physician emotion regulation, we performed a thematic analysis of the conversation, its documentation, and physician interviews.

Results:

Out of 12 physicians approached, 11 (92%) SICG-trained physicians enrolled in the study: five medical oncology and six palliative care physicians. All 11 completed the survey (100% completion rate). Two sensors (chest band, wrist sensor) had <20% missing data during study tasks. The forearm sensor had > 20% missing data. The thematic analysis found that physicians’: 1) overarching goal was to move beyond prognosis to reasonable hope; 2) tactically focused on establishing a trusting, supportive relationship; and 3) possessed incomplete awareness of their emotion regulation strategies.

Conclusion:

Our novel, multimodal assessment of physician emotion regulation was feasible in a simulated SICG encounter. Physicians exhibited incomplete understanding of their emotion regulation strategies.

Keywords: Emotion regulation, communication, prognosis, physician, oncology

Introduction

Clinical discussions about prognosis, patient’s emotional response, values, and treatment goals called “serious illness conversations,” can improve patient and communication outcomes,1–4 and oncology practice guidelines recognize these conversations as essential parts of advanced cancer care.5,6 Structured conversations such as clinician scripts like the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG),7 promote high-quality communication. Randomized controlled trials evaluating the use of the SICG in oncology demonstrate 1) relevant process-based gains in the documentation of serious illness conversations (i.e., earlier, higher quality, more frequent)8 and 2) improvements in patient anxiety and depression.9 Nonetheless, observational studies indicate that physicians using the SICG may still omit two key guideline-endorsed communication practices:10,11 disclosing patient-requested prognostic information and responding to expressed patient emotion.12 Prior work in oncology confirms both of these shortcomings are common and not unique to the use of SICG.13–17 Tnhese practices are important because they were each identified as key processes for the higher rate of goal-concordant care observed in two randomized controlled trials of early, integrated specialty palliative care, compared to usual care oncology.18,19 Prior studies indicate that both patient emotion25–27 and physician emotion28–30 moderate the willingness to openly discuss prognosis. Therefore, understanding how physicians manage self and patient emotions – emotion regulation – may be useful for developing more effective interventions to modify physician communication behavior.

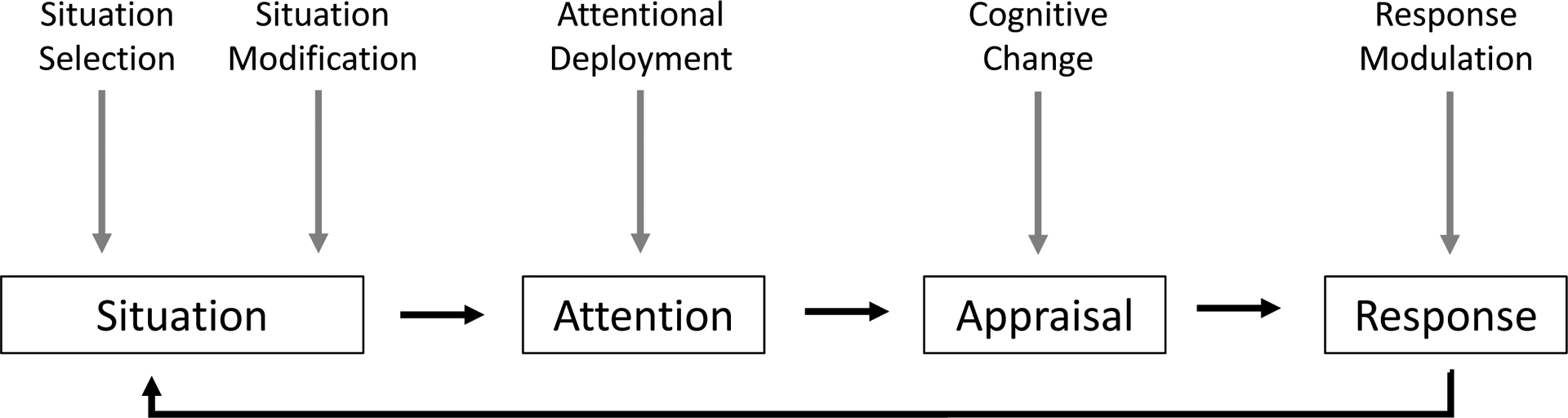

Emotion regulation includes “the processes by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and then express those emotions.”20 Successful emotion regulation involves modulating emotion to achieve a goal (hedonic or instrumental).21 Gross’s process model categorizes emotion regulation strategies into five sequential processes that produce flexible responses (Figure 1).20,22 Refinements to the model include contextualizing it to reflect social interactions and framing the regulation by its intended target: the term “intrinsic” (aka intrapersonal) is used for self-targeting, and the term “extrinsic” (aka interpersonal) is used for targeting another individual.23 Inherently, intrinsic and extrinsic emotion regulation exist on a continuum, and in some circumstances, one cannot delineate a clear distinction.24

Figure 1.

Gross’s Process Model of Emotion Regulation

Situation Selection refers to actions that make it more or less likely to give rise to an emotion (e.g. initiating versus avoiding a serious illness conversation). Situation modification refers to modifying context to alter emotional impact (e.g. conducting the conversation alone versus with the patient’s caregiver). Attention deployment refers to directing one’s attention towards or away from emotion (e.g. redirecting conversation towards versus away from emotion). Cognitive change refers to how one appraises the situation (e.g. viewing the expression of negative emotion as caused by physician behavior versus a natural response to bad news). Response modulation refers to changes in experiential, behavioral or physiologic responses (e.g. physician’s internal experience, communication behavior or autonomic changes).

An important gap in the literature for clinician emotion regulation involves measurement and analytic strategies, specifically how to optimize and integrate between different data sources (i.e., self-report, physiologic, and observer). Validated psychologic inventories can assess an individual’s momentary affective state (e.g., PANAS31), use of emotion regulation strategies (e.g., DIRE32), and abilities (e.g., ERSQ33). These measures can provide reliable, quick, and meaningful insights, but include reliance on accurate self-awareness and do not allow moment-by-moment assessments. Physiologic measures of moment-by-moment emotion regulation rely on assessing the autonomic nervous system.33 Biometric markers of emotion regulation include heart rate variability (HRV), electrodermal activity, facial electromyography, and afferent pupillary dilation.34–36 These biometric measures can provide objective measures of physiologic response, potentially at a more granular level. However, major downsides include technical challenges in measurement, optimal use conditions inhibiting usual real-world task performance, and confounding physiologic processes (e.g., medications, health conditions, etc.). A third group of emotion regulation assessment strategies uses observation and includes: assessment of written narratives,37,38 interviews with a trained psychiatrist,21 structured observer tools,39 and qualitative assessment of verbal, paraverbal, and nonverbal communication.40 Downsides of observer approaches include omitting important contextual factors (e.g., cultural norms, language) and methods are time-intensive. Some researchers advocate combining measurement strategies to overcome the limitations of any single approach.41 Currently, the assessment of clinician emotion regulation during the use of the SICG has not been described in the literature.

In this study, we sought to develop and evaluate an experimental framework using multimodal assessment of physician emotion regulation during serious illness conversations. To evaluate our novel framework, we chose to pilot the data collection and analysis in a simulated telehealth visit before fieldwork with actual patients. Our primary aim was to assess the feasibility of the experimental framework. We predefined three measures as the benchmarks for feasibility: enrollment rate ≥60% of approached physicians, >90% completion rate of survey items, and <20% missing data from the wearable sensors. Our secondary aim was to describe physician emotion regulation in the context of conducting serious illness conversations.

Methods

This study used a multimodal assessment to examine SICG-trained physicians’ emotion regulation during a simulated, telehealth encounter using the SICG. The simulation methodology permits standardization and eliminates the potential for patient harm. The Dartmouth Health IRB approved our study protocol, which was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov(NCT05365763).

Development Phase

A multidisciplinary team developed the simulated case and data collection design. The team included palliative care physicians, a medical oncologist, an affective scientist, a behavioral decision scientist, and a biostatistician. The simulated case depicted a 46-year-old woman with recurrent liposarcoma on second-line chemotherapy, open to participating in a physician-led SICG. The case included clinical instructions: a paragraph clinical summary, instructions to conduct a SICG, and time-based prognostic information in different formats (e.g., “months to a year” versus “two-year overall survival is 25%”). We trained one experienced actor to play the role of the patient. The training standardized two pre-planned emotion cues: 1) mild anxiety when first broaching the conversation; and 2) shock moving into sadness during prognosis disclosure. The final protocol included refinements identified through two pilot telehealth encounters using study team members.

Biometric Sensors

We selected three sensors: the more expensive Empatica E4® (E4) worn on the wrist (~$1500); the consumer wearable Scosche® Rhythm24 (R24) worn on the forearm (~$100); and the consumer wearable chest-band Polar® H10 (H10) (~$100). The E4 had the built-in capability to store readings remotely, whereas the R24 and H10 required a Bluetooth connection to another device and a third-party application to capture continuous HRV data. We used Elite HRV™ version 5.5.4 run on an investigator’s Apple® iPhone and iPad to capture and upload continuous recordings of R24 and E10 HRV. E4 results were stored remotely on the device and uploaded in its proprietary software after the session. We assessed Apple Watch Series 4® as a candidate sensor. However, it could not be used for this study because its software provided only a few minutes of HRV data, not a continuous reading.

Recruitment

We performed convenience sampling at a single academic medical center of medical oncology and specialty palliative physicians known to have completed SICG training. After completion of all study activities, physicians received a $100 honorarium.

Data Collection on Physician Emotion Regulation

In the three days before their scheduled session, physicians received an online survey (REDCap®, Nashville, TN) that included demographics, 22-item Maslach Burnout Inventory for Medical Personnel (MBI-MP),42 and 27-item Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ)33.

The experimental task began with verbal and written instructions. Next, the physician participant attached wrist, arm, and chest band HRV sensors in a private setting. The physician then participated in a 7-minute rest-activity with concurrent baseline HRV recording to compare with HRV recorded during the simulated telehealth encounter.

Physicians reviewed the case instructions after the rest activity, had the opportunity to ask any questions, and completed the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) to measure their initial positive and negative affect.31 The telehealth encounter with the standardized patient was conducted and recorded via videoconferencing software (Zoom® version 5.7). Physicians ended the encounter at their discretion by closing the visit. After the encounter, physicians completed the PANAS again, removed the sensors, and documented the encounter in our institution’s electronic health record (EHR) Epic® Play environment using our intuition’s standardized SICG template.

Lastly, physicians participated in an audio-recorded, semi-structured interview. The interviewer asked about the physician’s emotional experience and its impact on the encounter in two phases (Appendix A). First, the interviewer assessed the physician’s experience of the overall encounter. Second, the interviewer and subject watched the video-recorded encounter together, stopping at three pre-planned conversational events to discuss the physician’s perspective: 1) patient anxiety at broaching SICG; 2) shock after hearing prognosis; and 3) physician recommendation at the conversation end.

Data Analysis

Using a hybrid coding approach,43 two authors (GTW medical oncologist; SKG communication scientist) semantically coded each physician’s dataset (encounter, interview, and EHR note) in two steps. Step 1 began with data familiarization, and discussing initial observations. Step 2 recorded semantic codes for each transcript individually, line-by-line. To discuss and define the codebook, the coders discussed codes during weekly meetings until an agreement was reached. The emotion regulation literature, communication skills literature, and Gross’s process model20,22 informed a priori codes. Each observed emotional regulation strategy was assigned to a single category, intrinsic vs extrinsic, to avoid redundancy. Coders resolved differences and developed a consensus on codes, code definitions, and categorizations to ensure rigor. The dataset was then deductively coded on Atlas.Ti based on the final codebook. The authors followed the six phases of Braun and Clarke’s43 in their thematic analysis.

Survey data were summarized with descriptive statistics of all psychological inventories and length of study activities. For biometric sensor data, investigators measured the length of each study activity and compared these times with the associated timestamps reported by each sensor to assess if <20% of each study activity was missing. We do not report visual inspection or quality assessment of HRV data. For Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), we applied the commonly used Emotion Exhaustion (EE) Score of ≥27 or Depersonalization (DP) score of ≥10 defining “burnout.”44 Differences in physicians’ positive and negative affective states (PANAS) before and after the telehealth encounter were assessed using paired t-tests (STATA version 15.1, College Station, TX). Based upon a planned sample size of 10 participants, we had 80% power to detect a 3-point difference in positive or negative affect, considered clinically significant. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons.

Results

Study population

We approached 12 physicians and 11 (92%) enrolled. They included 5 (45%) females, 10 who self-identified as white (91%), 5 medical oncologists (45%), 6 specialty palliative care (55%), and a reported average of 11 years (SD = 7.5) in their current clinical role. At baseline, participants scored a mean of 2.77 (SD = 0.48) on the ERSQ, and 4 (36%) exhibited “burnout” on the MBI. Between the pre- and post-encounter PANAS, there was a statistically significant decrease in negative affect, t(10) = 5.22, p < 0.01, but no statistically significant change in positive affect, t(10) = −1.89, p = 0.09 (see Table 1 for full results).

Table 1.

Physician Demographics and Psychologic Inventory results

| Physicians (n=11) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | n | % |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 49 (10) | |

| Female sex | 5 | 45 |

| Race | ||

| White | 10 | |

| Asian | 1 | |

| Specialty | ||

| Medical Oncology | 5 | |

| Palliative Care | 6 | |

| Years in Current Clinical Role, mean SD | 11 (7.5) | |

| Estimated average use of SICG in practice | ||

| None since being trained | 1 | 9 |

| Once per year | ||

| Once every six months | 1 | 9 |

| Once every two months | ||

| Once a month | 2 | 18 |

| Once a week | 3 | 27 |

| Two or more times a week | 4 | 32 |

| Number meeting criteria for “burnout” | 4 | 36 |

| Psychologic Inventories | Mean | (SD) |

| Maslach Burnout Inventory | ||

| Emotional Exhaustion | 17.4 | 9.2 |

| Depersonalization | 6.1 | 4.6 |

| Personal Achievement | 41.1 | 5.0 |

| Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire | ||

| Attention | 2.83 | 0.61 |

| Body perception | 2.47 | 0.45 |

| Clarity | 2.83 | 0.52 |

| Understanding | 3.03 | 0.60 |

| Acceptance | 2.77 | 0.56 |

| Resilience | 2.93 | 0.75 |

| Readiness | 2.87 | 0.72 |

| SS | 2.57 | 0.74 |

| Modification | 2.60 | 0.57 |

| Total ER | 2.77 | 0.48 |

| PANAS | ||

| Positive Affect before1 | 30.8 | 8.2 |

| Positive Affect after1 | 33.6 | 8.6 |

| Negative Affect before2 | 15.6 | 2.5 |

| Negative Affect after2 | 11.9 | 1.8 |

P-value for difference is 0.09

P-value for difference is <0.01

Feasibility of study procedures

All participants completed all study survey items (100%). The median length of the telehealth encounter was 24 minutes (range 16 – 34 minutes). The biometric sensor performance of the chest band (Polar H10™) and the wrist sensor (Empatica E4™) met the study benchmark (less than 20% missing data) for resting and telehealth encounter tasks, but the forearm sensor (Scoche R24™) did not, missing HRV in 36% of resting tasks (4/11) and 63% (7/11) of telehealth encounters.

Qualitative findings of clinician emotion regulation strategies

Triangulating across our three data sources (e.g., encounter, interview, documentation), we observed physicians engage in emotion regulation before, during, and after disclosing a prognosis in the simulated serious illness conversation. We observed intrinsic (Table 2) and extrinsic strategies (Table 3) used in varying degrees for physician emotion regulation’s goal, strategic focus, and awareness of its use in this context. We summarize the themes below and provide examples categorized via Gross’ process model in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Intrinsic (Self-focused) Physician Emotion regulation strategies

| Strategies deployed | Illustrative Quotes from Interview or Simulated Encounter | |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1. Goal as reasonable hope |

Cognitive Change Self-efficacy |

We’ve got a plan. We’re going to be able to help this lady. Kind of feeling pretty good. [Interview, Physician 7, Palliative Care] |

| Self-critical | I guess I was feeling mildly incompetent at the moment. [Interview, Physician 6, Palliative Care] | |

| Theme 2. Establishing trusting, supportive relationship |

Situation Modification Trusting relationship |

I think it continued to build trust. I think I was feeling sensing her mood as well that she was warming up a little bit, like she was smiling and laughing. So, I just think it helped the relationship continue in that direction. [Interview, Physician 7, Palliative Care] |

| Step-wise disclosure |

Physician: One thing is that chemotherapy like this usually donť eradicate, it does not, unfortunately, get rid of a cancer like this completely.

Patient: Okay. Physician: I know you had mentioned that part of your hope was that it would eradicate, and I think thaťs—I would hope for that, too, although I think, if I’m being honest with you, I think the likelihood is very low that chemotherapy would get rid of your cancer. Patient: Okay. Physician: So, at the same time, I agree with you that the goal of the treatment is to try to help you live longer and feel as good as you can feel. So, within that, you know, there is a significant risk that you could die in a year or less. [Physician 10, Oncology] |

|

|

Attention Deployment Heightened Attention |

Um, I was paying attention to whether I was pushing her too hard with all the talking about dying as a little worried about it. But I the data I was getting back was that she was tolerating it. [Interview, Physician 1, Palliative Care] | |

|

Cognitive Change Norm discordant |

There are things that I sometimes find myself doing, but they arenť quite as comfortable, and specifically giving prognostic information, I never do that. [Interview, Physician 4, Palliative Care] | |

| Norm concordant | No, this is--iťs a part of the oncologisťs life. [Interview, Physician 5, Oncology] | |

|

Response Modulation Follow the script |

I think it made it feel like it was an event with a beginning, a middle, and an end. [Interview, Physician 11, Palliative Care] | |

| Having a plan B | If I went too long and we lost the connection, or if she started to get—if we started to lose that trust a little bit. I don’t know if I would say if she got defensive, but if she started to put up a little bit of a barrier between the two of us, because I wasn’t responding to that. That’s what I didn’t want her to lose some of the buy-in that I had had up to this point. [Interview, Physician 7, Palliative Care] | |

| Theme 3. Incomplete awareness |

Cognitive Change High internal emotion |

I’m going to feel like a jerk, and she’s going to have her emotional world come crashing down upon her when she hears the truth. [Interview Physician 3, Oncology] |

| Low internal emotion | I don’t know. I’m pretty numb with these things. [Interview, Physician 10, Oncology] | |

|

Response Modulation Affective forecasting |

It informed me where she was coming from, and it did give me the sense--and she elaborated, like I’m doing fine, and I think that I kind of assigned her a reason for thinking that. I said, oh, a lot of people think about palliative care only being--because she gave me that information. So, I felt like it impacted, it gave me more information that she did that, I could understand it. [Interview, Physician 4, Palliative Care] | |

| Fortifying self | I was feeling really worried, and that’s why you can hear me tiptoeing up to it and putting brackets around it. [Interview, Physician 3, Oncology] |

Table 3.

Extrinsic (Patient-focused) Physician Emotion Regulation Strategies

| Physician strategies | Illustrative Quotes from the Simulated Encounter | |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1. Goal as reasonable hope |

Situation Selection Prognostic Confrontation |

From the information I have, iťs something that could become life-threatening within months to a year potentially, so iťs pretty serious. [Physician 9, Oncology] |

|

Situation Modification Softening the blow |

I see that you’re feeling good now and have energy and are tolerating the treatment, and I’m hoping that that will go on for a good long time…I think that we can probably anticipate that at some point things will progress. The timeline can be difficult to predict, but probably on the order of somewhere between months to a year, we may see the cancer come back. [Physician 11, Palliative Care] | |

|

Cognitive Change Positive Reframe |

Patient: I know [my son] is planning on getting married, but they’re not thinking next week, certainly. So I would really, really love to just see that. To be… to be around for that.

Physician: Thaťs important. And I can imagine and I’d like us to think together as we keep talking about ways for you to fill him in about what you’ve just heard so that maybe we can make that a reality so in some way have you be able to be there somehow? [Physician 1, Palliative Care] |

|

| Emphasize quality-of-life | The goal of treatment is quality of life. I want you to be as good as possible. [Physician 3, Oncology] | |

|

Response Modulation Pivot to more treatment |

You had shared that the first one stopped working, so you switched to another one. He did share that there are others, so if this one that you’re on is found to not be working well, there are others that can be tried. [Physician 4, Palliative Care] | |

| Selecting achievable goals | Actually, iťs maybe a realistic hope. If he were three years old, and to marry … I mean, we can work together to help you achieve most of these goals. [Physician 5, Oncology] | |

| Pivot to advance care planning | One place to start may be to talk with his physician about making a long-term care plan. [Physician 6, Palliative Care] | |

|

Situation Selection Prognostic Avoidance |

Physician: What you’re hoping for over the future with your illness. Patient: Well, yeah, I guess before we kind of go into those questions, I’m wondering if there’s anybody--I donť know, maybe you’re not the person to ask this, but I donť really have a way of assessing goals until I understand my prognosis, actually, and I feel like I donť. [Physician 4, Palliative Care] |

|

|

Situation Modification Obtaining permission |

“Do you need a minute or are you okay if we keep chatting a little bit?” [Physician 9, Oncology] | |

|

Attention Deployment Pointing to a positive |

I really hope that you will do better than these average numbers that I mentioned earlier. [Physician 5, Oncology] | |

| Warning shot | But some of the questions are a little heavy, so if any of them make you uncomfortable, donť sweat it. [Physician 9, Oncology] | |

|

Response Modulation Rapport building |

I see that there’s a lot of sunlight there coming through your window, so I’m glad to see that. [Physician 7, Palliative Care] | |

| Praise | Those are pretty amazing things. Yeah. Makes you a pretty resilient person I can imagine. [Physician 1, Palliative Care] | |

| Validation | Right. Definitely, that kind of thing can be really important. [Physician 9, Oncology] | |

| Use of Empathy | I can imagine I would feel a lot of feeling about that and I just wonder how you’re feeling. [Physician 8, Palliative Care] |

Theme 1 – Physicians’ overarching goal was to move beyond prognosis to reasonable hope

Physician emotion regulation entailed managing emotion, patient and self, with a goal in mind. In our simulation, the physicians’ goal for providing the prognostic disclosure was not “breaking bad news” per se (i.e., life expectancy is years shorter than patient expectation), but the conversational activities that followed (i.e., attainable goal-setting). Borrowing from the psychiatric literature, we observed physicians engage in the clinical practice of constructing “reasonable hope,” when patients and clinicians work together to move from the unattainable to the attainable.45 From an intrinsic regulatory perspective, the internal benchmark for the physicians’ overall performance was attending to two overlapping objectives: 1) protecting the patient from future harm (e.g., missed opportunities or unwanted medical care) or 2) defining achievable, meaningful goals in light of a limited life expectancy.

Since the clinical practice of reasonable hope is mostly externally focused on the patient, physician use of extrinsic emotion regulation strategies predominated. The delivery of the prognosis (e.g., bad news) was the entry point for this practice, and physicians selected either a discrete headline on the short prognosis (prognostic confrontation) or couched the bad news to mitigate its full impact (softening the blow). The work of reasonable hope by and large came after the prognostic disclosure. While many factors were held constant across all encounters (e.g., physician instructions, SICG, trained actor), we observed variation in how the physicians used what they learned from the patient. Some engaged in communication seeking to bring about a cognitive change (reappraisal), which came in two forms: 1) positive reframing to focus on what can happen, and 2) emphasizing quality over length of life. They also varied in how they aligned towards an attainable goal, however, there was similarity in that multiple priorities were identified. In the recommendation part of the conversation, the physician might pivot to advance care planning. They might also, alongside the patient, select an achievable yet significant goal (e.g., consider another line of treatment, spend time with family). While physician emotion regulatory strategies varied, there was unity in the practice of generating reasonable hope once it was clear the prognosis was delivered and comprehended.

Theme 2 – Physicians tactically focused on establishing a trusting, supportive relationship

Fostering and maintaining a trusting relationship with the patient was a focus for physicians navigating the prognostic disclosure within a serious illness conversation. Internally, the physician’s perception of this trust acted as a compass on how to proceed around sensitive disclosure like a shorter-than-expected time-based prognosis. For example, physicians used situation modification around the prognosis disclosure, either by ensuring sufficient trust existed before disclosing the prognosis or by providing the prognosis step-wise that allowed them to titrate the information provided. Correspondingly, attention and cognitive changes in the physician centered on assessing whether the therapeutic bond with the patient was still intact. Lastly, in their response modulation, physicians could adhere to the structure and language of the SICG to maintain the open dialogue (e.g., follow the script) or develop contingencies if the patient appeared to be losing trust.

Since trust is a social construct, many of the emotional regulation strategies we observed related to this theme were extrinsic. The provision of emotional support was deeply intertwined with building trust: emotional support was seen in various iterations (e.g., praise, validation, use of empathy) as were other more explicit trust-building activities (e.g., obtaining permission). The overarching observation was that the physicians continually attended to the patient’s psychological safety throughout the serious illness conversation, and that trust was the foundation to effect the desired outcome.

Theme 3 – Physicians possessed incomplete awareness of their emotion regulation strategies.

The intensity of the internal emotions experienced by physicians differed widely. In their interviews, some describe feeling low to no emotion, and others describe high emotions, especially immediately after the prognostic disclosure. We also observed variability in the physician’s awareness of their use of emotion regulation strategies. For example, some engaged in a form of affective forecasting where they predicted what, why, and how the patient’s emotion might change. These predictions may have allowed the physician to draw on internal resources to tolerate negative emotions (e.g., fortifying self). The interviews also indicated that the emotion regulation strategies deployed by the physicians were sometimes outside of their conscious control. In one physician interview, the physician reprimands themselves for the delayed disclosure of a prognosis, “instead of just giving her a time, I spent a lot of time talking about what it was that we were trying to put off” (Physician 11). In other instances, the physician’s description of the encounter was at odds with the observed behavior. For example, during the encounter, Physician 10 used various strategies to blunt the impact of the bad news (e.g., preamble on the patient’s treatment history, step-wise prognostic disclosure) as well as emphasizing uncertainty to undercut the message that time could be short. In the interview, Physician 10 described the prognostic disclosure as “non-problematic”, “I have her permission,” and “we are at a good place to share information,” which all belie the tip-toeing up to the prognosis and the immediate response afterward of emphasizing uncertainty. We observed instances, even within the same interview, where physician responses were consistent and inconsistent with their observed emotion regulation. We infer physician interviews are only a partially informative window into physician emotion regulation.

Discussion

In the development and evaluation of our experimental framework to assess physician emotion regulation during serious illness conversations in oncology, we had two main findings. First, our framework was technically successful and highlights the importance of multimodal assessments. For example, physician interviews were not consistently a reliable and informative data source for emotion regulation, suggesting the need for corroboration using other methods. Second, Gross’s process model was a helpful construct to gain insight into how physicians navigated a prognostic disclosure. In particular, the goals and tactics used by physicians to navigate this conversation were brought into clearer focus via this model.

The experimental framework met our pre-specified feasibility benchmarks for recruitment and data collection. The experimental framework also encountered technical and analytic challenges. Emotions varied dynamically over the course of the conversations, supporting previous findings.12 Therefore sampling psychologic inventory measures (e.g., MBI, ERSQ) before and after did not capture the full range of affect experienced by participants. Collecting biometric data alongside patient-physician communication data was intended to provide the moment-by-moment assessment. Nonetheless, not all sensor approaches are feasible. Despite its accessibility and interoperability, the Apple™ watch did support continuous HRV over the study tasks and the forearm sensor (Scoche R24™) had too much missing data. We speculate that the cause of the missing data was the phone or third-party application supporting the data stream. If either of these secondary technologies fail, HRV data collection is interrupted. Additionally, since we did not analyze the quality of the HRV data in this study, we cannot definitively comment on whether all these data sources can be successfully integrated to provide meaningful, coherent insights on physician emotion regulation. The successes and challenges support further development to characterize physician emotion regulation during SICG use more completely.

Our study is novel in its evaluation of physician emotion regulation during serious illness communication in oncology. Prior work in psychiatry describes how physicians regulate self and patient emotion during therapeutic encounters to treat mental health conditions,21,47 and given different therapeutic contexts involved, physician goals and strategies would be expected to differ in oncology. Our study builds on best-practice recommendations for delivering bad news,48,49 and provides a deeper exploration of physician motivations and emotional regulation strategies before, during, and after a prognostic disclosure. Although delivering the requested prognostic information was the instrumental goal of each study encounter, this goal was subsumed by the conversational work that occurred after (Theme 1). Using the definition provided by Kaethe Weingarten, we observed that physicians engaged in co-creating reasonable hope, “directing our attention to what is within reach more than what may be desired but unattainable.”45 To generate the psychological safety necessary for this conversation, physicians sought to foster a supportive and trusting relationship with the patient (Theme 2). Complementing prior work assessing the mechanisms by which specialty palliative care communication influenced health outcomes in oncology,18,19 our work suggests some potential means by which emotional support can influence medical decision-making (i.e., support prognostic awareness and attainable goal-setting). Lastly, physician insight around their emotion regulation of self and patient emotion was incomplete (Theme 3), suggesting stratagems to promote effective physician emotion regulation in this context cannot rely on self-identification alone.

While our study includes important strengths like data triangulation, use of a widely available communication tool (SICG),7, and sampling two different, physician specialties, there were nonetheless limitations. Caution should be made generalizing findings, as the nature of this being a simulated encounter (i.e., Hawthorne effect), use of the SICG, and case features (i.e., overly optimistic prognostic expectations) may have influenced the emotion regulation strategies used. Similarly, we sampled physicians from a single institution in rural New England who were predominantly white, and therefore cultural diversity in our sample is limited. We made design choices to enhance comparisons across encounters (i.e., use of the SICG, training one actor, same patient case) that will limit generalizability to other clinical and patient contexts. Our team lacked sufficient expertise in HRV analysis to inform the relative utility of physiologic measurement in addition to self-report and observer assessment on physician emotion regulation. We did not directly compare medical oncology to specialty palliative physicians given the small number of participants involved and the use of convenience sampling.

Structured conversations, like the SICG, assist physicians in the challenging task of delivering prognoses. Our multi-modal experimental framework establishes that integrating data from direct questioning, biometrics, and assisted introspection is feasible and can detect emotion regulation strategies in a controlled setting. Refinements and further integration among data sources will be required to optimize before use in the field.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Casey O’Quinn (clinical research coordinator) and Andrew Campbell for their early assistance in the grant.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

We thank the American Cancer Society and the Prouty Foundation affiliated with the DCC.

ECA was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Grant Number KL2TR002545. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

This work was performed at Dartmouth Cancer Center of Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, et al. Effects of End-of-Life Discussions on the Mental Health of Bereaved Family Members and Quality of Patient Death and Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(1):17–26.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315(3):284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340(mar23 1):c1345–c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy MH, Weinstein SM, Carducci MA, NCCN Palliative Care Practice Guidelines Panel. NCCN: Palliative care. Cancer Control. 2001;8(6 Suppl 2):66–71. http://www1.si.mahidol.ac.th/Palliative/node/30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor J Cancer care during the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1986–1996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labs Ariadne. Serious Illness Care. https://www.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care/. Published 2021. Accessed August 27, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. Evaluating an Intervention to Improve Communication between Oncology Clinicians and Patients with Life-Limiting Cancer: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial of the Serious Illness Care Program. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):801–809. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the Serious Illness Care Program in Outpatient Oncology: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):751–759. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(31):3618–3632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Palliative Care https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/palliative.pdf. Published 2021. Accessed October 5, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geerse OP, Lamas DJ, Sanders JJ, et al. A Qualitative Study of Serious Illness Conversations in Patients with Advanced Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(7):773–781. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koedoot C, Oort F, de Haan R, Bakker PJ, de Graeff A, de Haes JCJ. The content and amount of information given by medical oncologists when telling patients with advanced cancer what their treatment options are. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(2):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knutzen KE, Sacks OA, Brody-Bizar OC, et al. Actual and Missed Opportunities for End-of-Life Care Discussions With Oncology Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113193. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou WS, Hamel LM, Thai CL, et al. Discussing prognosis and treatment goals with patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative analysis of oncologists’ language. Heal Expect. 2017;20(5):1073–1080. doi: 10.1111/hex.12549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist Communication About Emotion During Visits With Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing Communication Between Oncologists and Patients With a Computer-Based Training Program. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):593. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas TH, Jackson VA, Carlson H, et al. Communication Differences between Oncologists and Palliative Care Clinicians: A Qualitative Analysis of Early, Integrated Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(1):41–49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):283–290. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross JJ. The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2(3):271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weilenmann S, Schnyder U, Parkinson B, Corda C, von Känel R, Pfaltz MC. Emotion Transfer, Emotion Regulation, and Empathy-Related Processes in Physician-Patient Interactions and Their Association With Physician Well-Being: A Theoretical Model. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:389. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross JJ. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Second. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams WC, Morelli SA, Ong DC, Zaki J. Interpersonal emotion regulation: Implications for affiliation, perceived support, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018;115(2):224–254. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messina I, Calvo V, Masaro C, Ghedin S, Marogna C. Interpersonal Emotion Regulation: From Research to Group Therapy. Front Psychol. 2021;12(March):1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derry HM, Maciejewski PK, Epstein AS, et al. Associations between Anxiety, Poor Prognosis, and Accurate Understanding of Scan Results among Advanced Cancer Patients. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(8):961–965. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang ST, Chen CH, Wen FH, et al. Accurate Prognostic Awareness Facilitates, Whereas Better Quality of Life and More Anxiety Symptoms Hinder End-of-Life Care Discussions: A Longitudinal Survey Study in Terminally Ill Cancer Patients’ Last Six Months of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1068–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end of life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver beravement adjustment. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenton JJ, Duberstein PR, Kravitz RL, et al. Impact of Prognostic Discussions on the Patient-Physician Relationship: Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(3):225–230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.6288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han PKJ, Dieckmann NF, Holt C, Gutheil C, Peters E. Factors affecting physicians’ intentions to communicate personalized prognostic information to cancer patients at the end of life: An experimental vignette study. Med Decis Mak. 2016;36(6):703–713. doi: 10.1177/0272989X16638321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Vliet LM, Epstein AS. Current state of the art and science of patient-clinician communication in progressive disease: Patients’ need to know and need to feel known. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3474–3478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon-Gordon KL, Haliczer LA, Conkey LC, Whalen DJ. Difficulties in Interpersonal Emotion Regulation: Initial Development and Validation of a Self-Report Measure. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2018;40(3):528–549. doi: 10.1007/s10862-018-9647-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berking M, Znoj H. Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur standardisierten Selbsteinschätzung emotionaler Kompetenzen (SEK-27). Zeitschrift für Psychiatr Psychol und Psychother. 2008;56(2):141–153. doi: 10.1024/1661-4747.56.2.141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinner VL, Kuchinke L, Dierolf AM, Merz CJ, Otto T, Wolf OT. What our eyes tell us about feelings: Tracking pupillary responses during emotion regulation processes. Psychophysiology. 2017;54(4):508–518. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balzarotti S, Biassoni F, Colombo B, Ciceri MR. Cardiac vagal control as a marker of emotion regulation in healthy adults: A review. Biol Psychol. 2017;130(April):54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latham MD, Cook N, Simmons JG, et al. Physiological correlates of emotional reactivity and regulation in early adolescents. Biol Psychol. 2017;127(July):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doulougeri K, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. (How) do medical students regulate their emotions? BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0832-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaki J, Craig Williams W. Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion. 2013;13(5):803–810. doi: 10.1037/a0033839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagstrøm J, Spang KS, Christiansen BM, et al. The Puzzle of Emotion Regulation: Development and Evaluation of the Tangram Emotion Coding Manual for Children. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10(October):1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kazemitabar M, Lajoie SP, Doleck T. Analysis of emotion regulation using posture, voice, and attention: A qualitative case study. Comput Educ Open. 2021;2(February):100030. doi: 10.1016/j.caeo.2021.100030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagasawa T, Masui K, Doi H, Ogawa-Ochiai K, Tsumura N. Continuous estimation of emotional change using multimodal responses from remotely measured biological information. 2022;27:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s10015-022-00734-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Fourth. Menlo Park, California: Mind Garden, Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2012:57–71. doi: 10.1037/13620-004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians a systematic review. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weingarten K Reasonable hope: Construct, clinical applications, and supports. Fam Process. 2010;49(1):5–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaffer F, Ginsberg JP. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front Public Heal. 2017;5(September):1–17. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barzilay S, Gagnon A, Yaseen ZS, et al. al. Associations between clinicians’ emotion regulation, treatment recommendations, and patient suicidal ideation. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2022;52(2):329–340. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA. Approaching Difficult Communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(3):164–177. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/canjclin.55.3.164/full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Derry HM, Epstein AS, Lichtenthal WG, Prigerson HG. Emotions in the room: common emotional reactions to discussions of poor prognosis and tools to address them. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19(8):689–696. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2019.1651648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.