Abstract

Background and Objectives

The use of highly effective multiple sclerosis (MS) disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) is rapidly increasing. Yet, little is known about their real-world risks of infections. The goals of this study were to assess the comparative risk of outpatient and serious infections across DMTs in a large, diverse, U.S. cohort and determine whether such risks are attributable to DMTs, having MS, or other factors.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of Kaiser Permanente Southern California members from 2008 through 2020 with MS and non-MS controls matched on age, sex, race, and ethnicity. MS treatments, serious (those requiring hospitalization) and outpatient infections, and covariates were collected from the electronic health record. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) and risk ratios (aRR) were estimated using the Cox and Poisson regression, respectively.

Results

Six thousand, six hundred and twenty-six patients with MS with 11,929 treatment episodes (2,487 rituximab, 546 natalizumab, 298 fingolimod, 4,629 interferon-beta/glatiramer acetate, IFN/GLAT, and 3,969 untreated) and 33,550 population controls were included in the analyses. The average age at treatment start ranged from 38.9 to 49.2 years, and 74% were women. Untreated (aRR = 1.39, [95% CI = 1.35–1.44]) and IFN/GLAT-treated patients with MS (aRR = 1.60, [95% CI = 1.56–1.65]) had a higher risk of outpatient infections and serious infections (aHR = 2.97, [95% CI = 2.65–3.32 and aHR = 2.31, [95% CI = 2.04–2.62], respectively) compared with controls. Rituximab (aRR = 1.19, [95% CI = 1.14–1.25]), fingolimod (aRR = 1.22, [95% CI = 1.09–1.37]), and to a lesser extent, natalizumab treatment (aRR = 1.08, [95% CI = 0.97–1.20]) were associated with an increased risk of outpatient infections compared with IFN/GLAT. Rituximab (aHR = 1.41, [95% CI = 1.09–1.84]) and natalizumab (aHR = 1.40, [95% CI = 0.96–2.04]) treatment were associated with a similar increased risk of serious infections compared with IFN/GLAT. The only treatment-specific association identified was fingolimod with outpatient herpetic infections. Higher comorbidity index, previous hospitalization for infections, and advanced disability significantly increased the risk of serious infections independent of DMTs. Hospitalization for UTI-related pseudorelapses accounted for 24%–48% of serious infections.

Discussion

Patients with MS have higher risks of outpatient and serious infections compared with patients without MS. The risk of outpatient infections was similarly increased by rituximab and fingolimod and serious infections by rituximab and natalizumab compared with IFN/GLAT. Steps to minimize risks include optimizing bladder care, comorbidity prevention, varicella vaccination, and considering discontinuing or avoiding DMT use in patients with advanced disability and/or previous hospitalizations for infections.

Introduction

Because multiple sclerosis (MS) disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have become more effective at suppressing inflammatory disease activity and the mechanisms of action of these highly effective DMTs have expanded, an increased risk of serious infections and DMT-specific infections have emerged.1,2 Understanding the magnitude of infectious risks and identifying potentially modifiable risk factors are becoming a vital part of risk-benefit discussions when choosing a DMT, yet little real-world data exist.

Current understanding of DMT infectious risks is derived primarily from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and postmarketing studies, neither of which are sufficient. RCTs include highly selected patients that are generally younger, less disabled, with fewer comorbidities, and treated for a shorter duration than real-world MS populations, thereby generally underestimating the risk of infections.3 Postmarketing studies, although important for identifying unusual DMT-specific risks with prolonged use such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) with natalizumab, are not useful for generating comparative data on infections commonly seen in patients with MS such as urosepsis or urinary tract infections (UTIs).4,5

The single real-world study to-date1 found that natalizumab, fingolimod, and particularly rituximab increased the overall risk of serious infections compared with interferon-beta (IFN) or glatiramer acetate (GLAT). Whether these findings can be extrapolated to U.S. DMT-treated populations that typically have more comorbidites, include subgroups of patients with advanced disability, are racially and ethnically diverse, and do not benefit from universal healthcare coverage is unclear. In addition, studies including a comprehensive set of both milder outpatient and more severe hospitalized infections across DMTs in real-world populations are still lacking.

The goals of this study were to assess the comparative risk of outpatient and serious infections in a large, diverse, U.S. MS cohort to determine to what extent such risks are attributable to having MS or DMTs and to identify potentially modifiable factors.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using Kaiser Permanente Southern California's (KPSC) complete electronic health record (EHR). KPSC provides care to >4.8 million members in Southern California, representing ∼20% of the general population in this geographic area. The sociodemographic characteristics of KPSC members are representative of the underlying population.6

The EHR was electronically searched from January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2020, to identify the following: persons with MS (pwMS), start and stop dates of DMTs, clinical and demographic characteristics, serious and outpatient infections, and general population controls matched 5:1 on date of birth, sex, race and ethnicity, and membership duration during the study period. The EHR of rituximab-treated persons were reviewed to confirm MS diagnosis.7,8 Inclusion criteria were (1) diagnosis of MS using a validated algorithm9 and (2) 6-month continuous membership. Exclusion criteria were rituximab treatment for non-MS diagnoses (n = 117) and treatment with rarely used DMTs (n = 199).

Serious infections, other than novel corona virus 2019, were defined as hospitalizations with ICD9 or 10 infection code as the primary or secondary discharge diagnoses equivalent to Grade 3 or higher per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).10 Sepsis, urosepsis, and pneumonia were identified via ICD9/10 codes (eTable 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A911). To identify rare infectious complications associated with DMTs, all charts with ≥1 hospital discharge diagnosis for PML, herpetic infections, meningitis, or encephalitis were manually reviewed. Hospitalizations for pseudorelapses because of UTIs were included because (1) they meet the definition for CTCAE grade 3 or higher and (2) although not life-threatening, are important to patients and healthcare systems. These pseudorelapses were defined as ICD9/10 code for MS as primary discharge diagnosis with UTI as secondary discharge diagnosis and no ICD code for sepsis during the same hospitalization.

Prespecified outpatient infections were selected based on the input from patient and clinician stakeholders. These included UTIs, upper and lower respiratory tract infections (URI and LRI), otitis media, cellulitis, herpetic, fungal, and vaginal infections. Trichomoniasis, a sexually transmitted vaginitis, was measured as a control. The prespecified infections were identified using validated algorithms that combines ICD codes and episode definitions (all outcomes), abnormal chest imaging (pneumonia), dispensed antivirals, and removing prophylactic antivirals (herpetic infections), antibiotics (UTIs, bacterial vaginosis [BV], trichomoniasis), antifungals (yeast vaginitis), and/or abnormal laboratory tests (UTI) identified from the EHR.11 All outpatient infections were defined as any outpatient infection ICD9/10 code. If the same 3-digit ICD code was entered within 3 months, it was counted as one episode.

The crude incidence rates (IR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated after tabulating all infection counts and person-year (PY) contributions in each group. Poisson regression models were used to calculate the risk ratios (RR) and adjusted RR (aRR) of outpatient infections and Cox proportional hazards models for time to first serious infection. We compared untreated MS and treatment with rituximab, natalizumab, fingolimod, or IFN/GLAT to general population controls and conducted analyses restricted to DMT-treated patients with MS compared with IFN/GLAT group. We were underpowered to detect a difference in serious infections in the fingolimod-treated group; thus, these results are not included (eMethods, links.lww.com/NXI/A911).

DMT use was defined based on the onset of action as follows: ≥4 infusions of natalizumab, ≥1 infusion of rituximab, ≥2 dispensed prescriptions of fingolimod, and ≥3 dispensed prescriptions of IFN or GLAT. To account for prolonged immunosuppression after the last DMT use, DMT discontinuation was defined as follows: 24 months since last rituximab or other B-cell depleting drug, 6 months after last natalizumab infusion, or dispensed prescription of fingolimod, IFN, or GLAT. Patients who started another DMT during a previous DMT discontinuation window (e.g., starting rituximab 6 weeks after discontinuing natalizumab) were classified as being only on the new DMT (e.g., rituximab) as of the new DMT's (e.g., rituximab) start date. Patients with MS who did not meet any of these definitions of DMT treatment, were past the previous DMT discontinuation window, nor were on other DMTs not included in these analyses (e.g., dimethyl fumarate), were classified as untreated. Thus, each infection was assigned only to one exposure category (rituximab, natalizumab, fingolimod, IFN/GLAT, or untreated).

Person-years contributions began at DMT start or untreated window (MS) and membership start (controls) during the study period and ended at membership termination, DMT discontinuation, or death, whichever came first. All models were adjusted for the following covariates at the start of each treatment window: age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (0, 1, ≥2),12 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, eTable 2, links.lww.com/NXI/A911), and hospitalization for infections in the previous 5 years (yes/no). Self-identified race and ethnicity obtained from the EHR was classified as white, non-Hispanic (referred to as white) or nonwhite, which includes Hispanic, Black, Asian, Native American/Alaskans, or mixed-race individuals as a surrogate measure for structural racism. Models restricted to patients with MS were additionally adjusted for advanced ambulatory disability (defined as requiring walker, wheelchair, Hoyer lift, and/or hospital bed; yes/no) and previous use of any DMT (yes/no). The robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate was used to account for patients who contributed to more than one group. Factors with p < 0.20 were included in the final adjusted model. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons because the purpose of this study is to identify safety signals, some of which may be rare.

Sensitivity analyses excluding hospitalization for UTI-related pseudorelapses were conducted to allow for comparison with previous studies.1,13 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study protocol was approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent because we used data already collected in the EHR and the no more than minimal risk to the participants.

Data Availability

Owing to the KPSC Institutional Review Board, data are available upon reasonable request.

Results

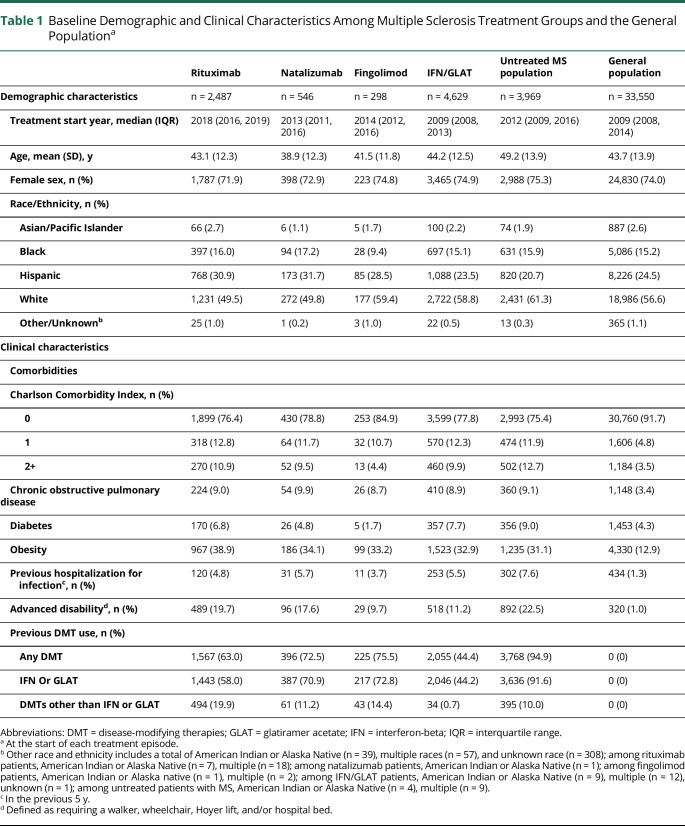

The demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. 11,929 treatment episodes among 6,626 patients with MS of whom 2,487 were treated with rituximab, 546 natalizumab, 298 fingolimod, 4,629 IFN/GLAT, and 3,969 untreated were included in the analyses. Switching DMTs, particularly from IFN/GLAT to other DMTs or to being untreated was common. Previous use of DMTs other than IFN/GLAT was highest among rituximab-treated patients (19.9%) and rare among IFN/GLAT group (0.7%). Advanced disability was almost as common among rituximab- or natalizumab-treated patients as untreated patients (19.7%, 17.6% and 22.5%, respectively). Patients with MS had more comorbidities, particularly COPD and diabetes, and were more likely to have been hospitalized for infections in the 5 years before the start of each treatment episode than the general population (Table 1). Fingolimod-treated patients were the healthiest among the MS groups with the lowest Charlson Comorbidity Indices, fewer infection-hospitalizations, or advanced disability (9.7%) and a diabetes rate (1.7%) that was lower than the general population. Natalizumab-treated patients were the youngest and untreated patients with MS the oldest at the start of each episode. The cohort was racially and ethnically diverse, with Hispanic pwMS comprising 24.4% and Black pwMS 15.1% of the cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Among Multiple Sclerosis Treatment Groups and the General Populationa

| Rituximab | Natalizumab | Fingolimod | IFN/GLAT | Untreated MS population | General population | |

| Demographic characteristics | n = 2,487 | n = 546 | n = 298 | n = 4,629 | n = 3,969 | n = 33,550 |

| Treatment start year, median (IQR) | 2018 (2016, 2019) | 2013 (2011, 2016) | 2014 (2012, 2016) | 2009 (2008, 2013) | 2012 (2009, 2016) | 2009 (2008, 2014) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.1 (12.3) | 38.9 (12.3) | 41.5 (11.8) | 44.2 (12.5) | 49.2 (13.9) | 43.7 (13.9) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 1,787 (71.9) | 398 (72.9) | 223 (74.8) | 3,465 (74.9) | 2,988 (75.3) | 24,830 (74.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 66 (2.7) | 6 (1.1) | 5 (1.7) | 100 (2.2) | 74 (1.9) | 887 (2.6) |

| Black | 397 (16.0) | 94 (17.2) | 28 (9.4) | 697 (15.1) | 631 (15.9) | 5,086 (15.2) |

| Hispanic | 768 (30.9) | 173 (31.7) | 85 (28.5) | 1,088 (23.5) | 820 (20.7) | 8,226 (24.5) |

| White | 1,231 (49.5) | 272 (49.8) | 177 (59.4) | 2,722 (58.8) | 2,431 (61.3) | 18,986 (56.6) |

| Other/Unknownb | 25 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (1.0) | 22 (0.5) | 13 (0.3) | 365 (1.1) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 1,899 (76.4) | 430 (78.8) | 253 (84.9) | 3,599 (77.8) | 2,993 (75.4) | 30,760 (91.7) |

| 1 | 318 (12.8) | 64 (11.7) | 32 (10.7) | 570 (12.3) | 474 (11.9) | 1,606 (4.8) |

| 2+ | 270 (10.9) | 52 (9.5) | 13 (4.4) | 460 (9.9) | 502 (12.7) | 1,184 (3.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 224 (9.0) | 54 (9.9) | 26 (8.7) | 410 (8.9) | 360 (9.1) | 1,148 (3.4) |

| Diabetes | 170 (6.8) | 26 (4.8) | 5 (1.7) | 357 (7.7) | 356 (9.0) | 1,453 (4.3) |

| Obesity | 967 (38.9) | 186 (34.1) | 99 (33.2) | 1,523 (32.9) | 1,235 (31.1) | 4,330 (12.9) |

| Previous hospitalization for infectionc, n (%) | 120 (4.8) | 31 (5.7) | 11 (3.7) | 253 (5.5) | 302 (7.6) | 434 (1.3) |

| Advanced disabilityd, n (%) | 489 (19.7) | 96 (17.6) | 29 (9.7) | 518 (11.2) | 892 (22.5) | 320 (1.0) |

| Previous DMT use, n (%) | ||||||

| Any DMT | 1,567 (63.0) | 396 (72.5) | 225 (75.5) | 2,055 (44.4) | 3,768 (94.9) | 0 (0) |

| IFN Or GLAT | 1,443 (58.0) | 387 (70.9) | 217 (72.8) | 2,046 (44.2) | 3,636 (91.6) | 0 (0) |

| DMTs other than IFN or GLAT | 494 (19.9) | 61 (11.2) | 43 (14.4) | 34 (0.7) | 395 (10.0) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: DMT = disease-modifying therapies; GLAT = glatiramer acetate; IFN = interferon-beta; IQR = interquartile range.

At the start of each treatment episode.

Other race and ethnicity includes a total of American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 39), multiple races (n = 57), and unknown race (n = 308); among rituximab patients, American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 7), multiple (n = 18); among natalizumab patients, American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 1); among fingolimod patients, American Indian or Alaska native (n = 1), multiple (n = 2); among IFN/GLAT patients, American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 9), multiple (n = 12), unknown (n = 1); among untreated patients with MS, American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 4), multiple (n = 9).

In the previous 5 y.

Defined as requiring a walker, wheelchair, Hoyer lift, and/or hospital bed.

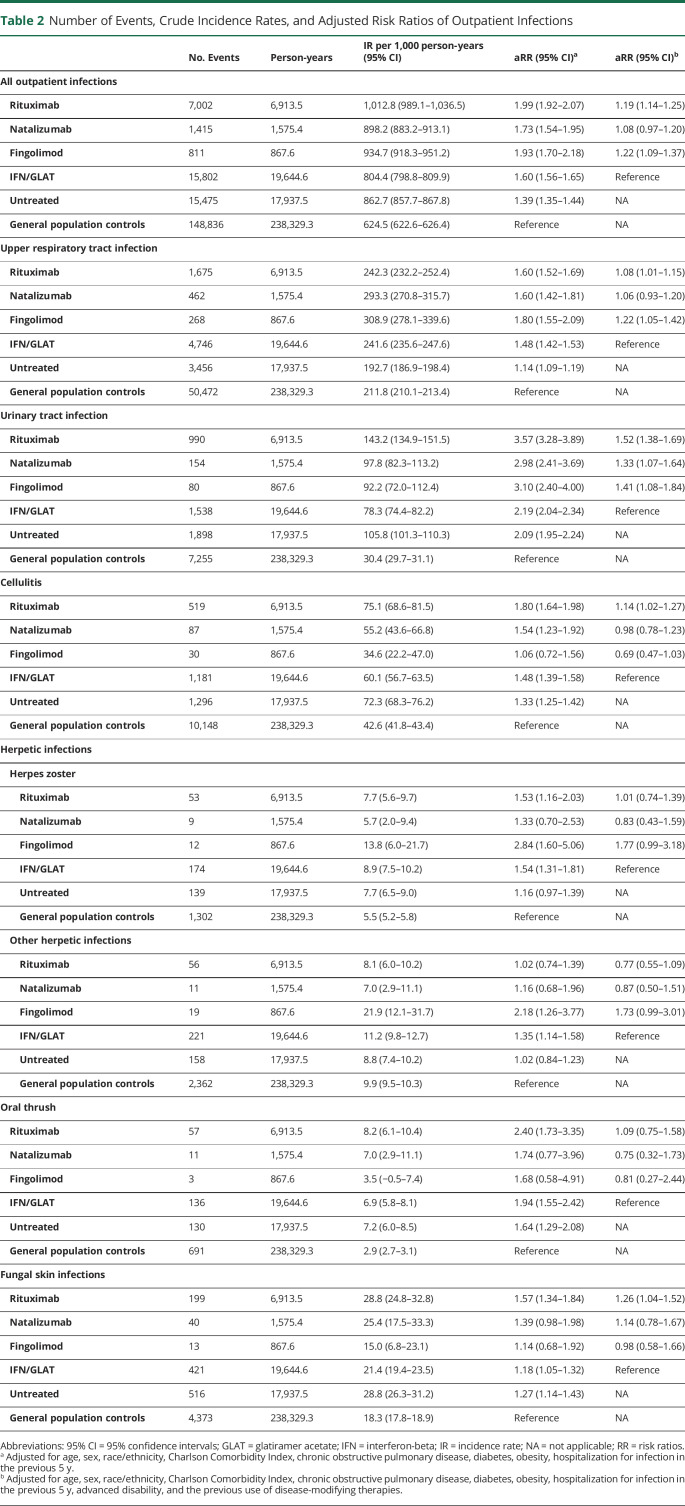

Outpatient Infections

Table 2 shows the number of events, crude IR, and aRR of outpatient infections. Untreated patients with MS had higher crude rates and adjusted risks of any outpatient infections, including UTIs, cellulitis, oral thrush, fungal skin infections, and herpes zoster, but similar rates and risks of LRI, pneumonia, otitis media, and fungal nailbed infections (eTable 3, links.lww.com/NXI/A911) compared with the controls. Treatment with IFN/GLAT was associated with additionally elevated aRR of URIs and herpetic infections compared with untreated patients with MS and controls.

Table 2.

Number of Events, Crude Incidence Rates, and Adjusted Risk Ratios of Outpatient Infections

| No. Events | Person-years | IR per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI)a | aRR (95% CI)b | |

| All outpatient infections | |||||

| Rituximab | 7,002 | 6,913.5 | 1,012.8 (989.1–1,036.5) | 1.99 (1.92–2.07) | 1.19 (1.14–1.25) |

| Natalizumab | 1,415 | 1,575.4 | 898.2 (883.2–913.1) | 1.73 (1.54–1.95) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| Fingolimod | 811 | 867.6 | 934.7 (918.3–951.2) | 1.93 (1.70–2.18) | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) |

| IFN/GLAT | 15,802 | 19,644.6 | 804.4 (798.8–809.9) | 1.60 (1.56–1.65) | Reference |

| Untreated | 15,475 | 17,937.5 | 862.7 (857.7–867.8) | 1.39 (1.35–1.44) | NA |

| General population controls | 148,836 | 238,329.3 | 624.5 (622.6–626.4) | Reference | NA |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | |||||

| Rituximab | 1,675 | 6,913.5 | 242.3 (232.2–252.4) | 1.60 (1.52–1.69) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) |

| Natalizumab | 462 | 1,575.4 | 293.3 (270.8–315.7) | 1.60 (1.42–1.81) | 1.06 (0.93–1.20) |

| Fingolimod | 268 | 867.6 | 308.9 (278.1–339.6) | 1.80 (1.55–2.09) | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) |

| IFN/GLAT | 4,746 | 19,644.6 | 241.6 (235.6–247.6) | 1.48 (1.42–1.53) | Reference |

| Untreated | 3,456 | 17,937.5 | 192.7 (186.9–198.4) | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | NA |

| General population controls | 50,472 | 238,329.3 | 211.8 (210.1–213.4) | Reference | NA |

| Urinary tract infection | |||||

| Rituximab | 990 | 6,913.5 | 143.2 (134.9–151.5) | 3.57 (3.28–3.89) | 1.52 (1.38–1.69) |

| Natalizumab | 154 | 1,575.4 | 97.8 (82.3–113.2) | 2.98 (2.41–3.69) | 1.33 (1.07–1.64) |

| Fingolimod | 80 | 867.6 | 92.2 (72.0–112.4) | 3.10 (2.40–4.00) | 1.41 (1.08–1.84) |

| IFN/GLAT | 1,538 | 19,644.6 | 78.3 (74.4–82.2) | 2.19 (2.04–2.34) | Reference |

| Untreated | 1,898 | 17,937.5 | 105.8 (101.3–110.3) | 2.09 (1.95–2.24) | NA |

| General population controls | 7,255 | 238,329.3 | 30.4 (29.7–31.1) | Reference | NA |

| Cellulitis | |||||

| Rituximab | 519 | 6,913.5 | 75.1 (68.6–81.5) | 1.80 (1.64–1.98) | 1.14 (1.02–1.27) |

| Natalizumab | 87 | 1,575.4 | 55.2 (43.6–66.8) | 1.54 (1.23–1.92) | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) |

| Fingolimod | 30 | 867.6 | 34.6 (22.2–47.0) | 1.06 (0.72–1.56) | 0.69 (0.47–1.03) |

| IFN/GLAT | 1,181 | 19,644.6 | 60.1 (56.7–63.5) | 1.48 (1.39–1.58) | Reference |

| Untreated | 1,296 | 17,937.5 | 72.3 (68.3–76.2) | 1.33 (1.25–1.42) | NA |

| General population controls | 10,148 | 238,329.3 | 42.6 (41.8–43.4) | Reference | NA |

| Herpetic infections | |||||

| Herpes zoster | |||||

| Rituximab | 53 | 6,913.5 | 7.7 (5.6–9.7) | 1.53 (1.16–2.03) | 1.01 (0.74–1.39) |

| Natalizumab | 9 | 1,575.4 | 5.7 (2.0–9.4) | 1.33 (0.70–2.53) | 0.83 (0.43–1.59) |

| Fingolimod | 12 | 867.6 | 13.8 (6.0–21.7) | 2.84 (1.60–5.06) | 1.77 (0.99–3.18) |

| IFN/GLAT | 174 | 19,644.6 | 8.9 (7.5–10.2) | 1.54 (1.31–1.81) | Reference |

| Untreated | 139 | 17,937.5 | 7.7 (6.5–9.0) | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | NA |

| General population controls | 1,302 | 238,329.3 | 5.5 (5.2–5.8) | Reference | NA |

| Other herpetic infections | |||||

| Rituximab | 56 | 6,913.5 | 8.1 (6.0–10.2) | 1.02 (0.74–1.39) | 0.77 (0.55–1.09) |

| Natalizumab | 11 | 1,575.4 | 7.0 (2.9–11.1) | 1.16 (0.68–1.96) | 0.87 (0.50–1.51) |

| Fingolimod | 19 | 867.6 | 21.9 (12.1–31.7) | 2.18 (1.26–3.77) | 1.73 (0.99–3.01) |

| IFN/GLAT | 221 | 19,644.6 | 11.2 (9.8–12.7) | 1.35 (1.14–1.58) | Reference |

| Untreated | 158 | 17,937.5 | 8.8 (7.4–10.2) | 1.02 (0.84–1.23) | NA |

| General population controls | 2,362 | 238,329.3 | 9.9 (9.5–10.3) | Reference | NA |

| Oral thrush | |||||

| Rituximab | 57 | 6,913.5 | 8.2 (6.1–10.4) | 2.40 (1.73–3.35) | 1.09 (0.75–1.58) |

| Natalizumab | 11 | 1,575.4 | 7.0 (2.9–11.1) | 1.74 (0.77–3.96) | 0.75 (0.32–1.73) |

| Fingolimod | 3 | 867.6 | 3.5 (−0.5–7.4) | 1.68 (0.58–4.91) | 0.81 (0.27–2.44) |

| IFN/GLAT | 136 | 19,644.6 | 6.9 (5.8–8.1) | 1.94 (1.55–2.42) | Reference |

| Untreated | 130 | 17,937.5 | 7.2 (6.0–8.5) | 1.64 (1.29–2.08) | NA |

| General population controls | 691 | 238,329.3 | 2.9 (2.7–3.1) | Reference | NA |

| Fungal skin infections | |||||

| Rituximab | 199 | 6,913.5 | 28.8 (24.8–32.8) | 1.57 (1.34–1.84) | 1.26 (1.04–1.52) |

| Natalizumab | 40 | 1,575.4 | 25.4 (17.5–33.3) | 1.39 (0.98–1.98) | 1.14 (0.78–1.67) |

| Fingolimod | 13 | 867.6 | 15.0 (6.8–23.1) | 1.14 (0.68–1.92) | 0.98 (0.58–1.66) |

| IFN/GLAT | 421 | 19,644.6 | 21.4 (19.4–23.5) | 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | Reference |

| Untreated | 516 | 17,937.5 | 28.8 (26.3–31.2) | 1.27 (1.14–1.43) | NA |

| General population controls | 4,373 | 238,329.3 | 18.3 (17.8–18.9) | Reference | NA |

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals; GLAT = glatiramer acetate; IFN = interferon-beta; IR = incidence rate; NA = not applicable; RR = risk ratios.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, hospitalization for infection in the previous 5 y.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, hospitalization for infection in the previous 5 y, advanced disability, and the previous use of disease-modifying therapies.

Treatment with rituximab, fingolimod, and to a lesser extent, natalizumab were associated with similarly increased aRR of all outpatient infections compared with general population controls and IFN/GLAT-treated patients, although the aRR of outpatient infections for natalizumab compared with IFN/GLAT did not reach statistical significance. The risk of UTIs were similarly increased in pwMS treated with rituximab, natalizumab, or fingolimod compared with both the general population and IFN/GLAT-treated pwMS. Fingolimod, rituximab, and natalizumab treatment were associated with similarly increased aRR of URIs, the most common infection across all groups, although this finding did not reach statistical significance for natalizumab when compared with IFN/GLAT. Cellulitis risk was similarly elevated in rituximab- or natalizumab-treated pwMS compared with controls. Compared with IFN/GLAT, only rituximab was associated with an increased risk of cellulitis (aRR = 1.14 [95% CI = 1.02–1.27]). Rituximab was also associated with an increased risk of fungal skin infections compared with IFN/GLAT (aRR = 1.26 [95% CI = 1.04–1.52]). Neither rituximab, natalizumab, nor fingolimod were associated with increased risks of LRI, outpatient pneumonia, otitis media, oral thrush, or BV compared with IFN/GLAT (eTable 3, links.lww.com/NXI/A911).

The crude rates and adjusted risks of herpes zoster and other herpetic infections were more than 2-fold higher among fingolimod-treated pwMS compared with controls. Fingolimod treatment was also associated with an increased risk compared with IFN/GLAT (herpes zoster aRR = 1.77 [95% CI = 0.99–3.18]; other herpes aRR = 1.73 [95% CI = 0.99–3.01]), although these findings did not reach statistical significance.

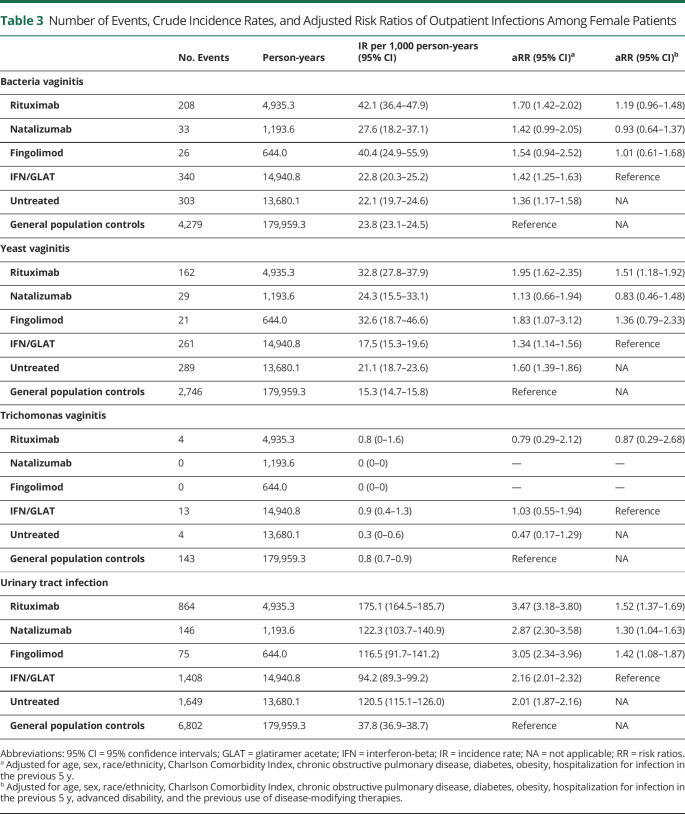

Vaginitis

Women with MS across all groups had higher adjusted risks of BV compared with controls, although this did not reach statistical significance for natalizumab- or fingolimod-treated women. The adjusted risk of yeast vaginitis was also higher among women with MS (except for natalizumab) compared with controls. Compared with IFN/GLAT, only rituximab was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of yeast vaginitis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of Events, Crude Incidence Rates, and Adjusted Risk Ratios of Outpatient Infections Among Female Patients

| No. Events | Person-years | IR per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI)a | aRR (95% CI)b | |

| Bacteria vaginitis | |||||

| Rituximab | 208 | 4,935.3 | 42.1 (36.4–47.9) | 1.70 (1.42–2.02) | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) |

| Natalizumab | 33 | 1,193.6 | 27.6 (18.2–37.1) | 1.42 (0.99–2.05) | 0.93 (0.64–1.37) |

| Fingolimod | 26 | 644.0 | 40.4 (24.9–55.9) | 1.54 (0.94–2.52) | 1.01 (0.61–1.68) |

| IFN/GLAT | 340 | 14,940.8 | 22.8 (20.3–25.2) | 1.42 (1.25–1.63) | Reference |

| Untreated | 303 | 13,680.1 | 22.1 (19.7–24.6) | 1.36 (1.17–1.58) | NA |

| General population controls | 4,279 | 179,959.3 | 23.8 (23.1–24.5) | Reference | NA |

| Yeast vaginitis | |||||

| Rituximab | 162 | 4,935.3 | 32.8 (27.8–37.9) | 1.95 (1.62–2.35) | 1.51 (1.18–1.92) |

| Natalizumab | 29 | 1,193.6 | 24.3 (15.5–33.1) | 1.13 (0.66–1.94) | 0.83 (0.46–1.48) |

| Fingolimod | 21 | 644.0 | 32.6 (18.7–46.6) | 1.83 (1.07–3.12) | 1.36 (0.79–2.33) |

| IFN/GLAT | 261 | 14,940.8 | 17.5 (15.3–19.6) | 1.34 (1.14–1.56) | Reference |

| Untreated | 289 | 13,680.1 | 21.1 (18.7–23.6) | 1.60 (1.39–1.86) | NA |

| General population controls | 2,746 | 179,959.3 | 15.3 (14.7–15.8) | Reference | NA |

| Trichomonas vaginitis | |||||

| Rituximab | 4 | 4,935.3 | 0.8 (0–1.6) | 0.79 (0.29–2.12) | 0.87 (0.29–2.68) |

| Natalizumab | 0 | 1,193.6 | 0 (0–0) | — | — |

| Fingolimod | 0 | 644.0 | 0 (0–0) | — | — |

| IFN/GLAT | 13 | 14,940.8 | 0.9 (0.4–1.3) | 1.03 (0.55–1.94) | Reference |

| Untreated | 4 | 13,680.1 | 0.3 (0–0.6) | 0.47 (0.17–1.29) | NA |

| General population controls | 143 | 179,959.3 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | Reference | NA |

| Urinary tract infection | |||||

| Rituximab | 864 | 4,935.3 | 175.1 (164.5–185.7) | 3.47 (3.18–3.80) | 1.52 (1.37–1.69) |

| Natalizumab | 146 | 1,193.6 | 122.3 (103.7–140.9) | 2.87 (2.30–3.58) | 1.30 (1.04–1.63) |

| Fingolimod | 75 | 644.0 | 116.5 (91.7–141.2) | 3.05 (2.34–3.96) | 1.42 (1.08–1.87) |

| IFN/GLAT | 1,408 | 14,940.8 | 94.2 (89.3–99.2) | 2.16 (2.01–2.32) | Reference |

| Untreated | 1,649 | 13,680.1 | 120.5 (115.1–126.0) | 2.01 (1.87–2.16) | NA |

| General population controls | 6,802 | 179,959.3 | 37.8 (36.9–38.7) | Reference | NA |

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals; GLAT = glatiramer acetate; IFN = interferon-beta; IR = incidence rate; NA = not applicable; RR = risk ratios.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, hospitalization for infection in the previous 5 y.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, hospitalization for infection in the previous 5 y, advanced disability, and the previous use of disease-modifying therapies.

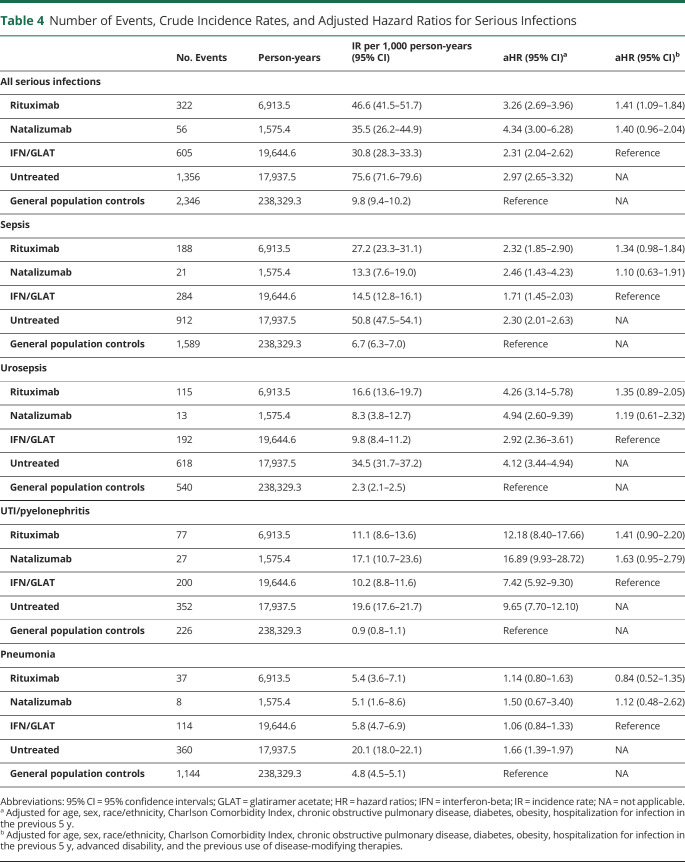

Serious Infections

Table 4 shows the number of events, crude IRs, and adjusted hazards ratios (aHR) of time to first serious infection. Untreated patients with MS have higher crude rates and adjusted risks of serious infections, including sepsis—particularly urosepsis—pneumonia, and notably, hospitalization for debility from otherwise uncomplicated UTIs (e.g., pseudorelapses) compared with general population controls. Patients with MS were more likely to be hospitalized more than once for infections (6.8%, n = 268 untreated, 2.6%, n = 65 rituximab-, 1.6%, n = 9 natalizumab-, and 2.7%, n = 123 IFN/GLAT-treated patients) compared with controls (1.3%, n = 425). Crude hospitalization rates for UTI-related debility/pseudorelapses accounted for 24% of hospitalizations among RTX and untreated patients with MS, 33% of IFN/GLAT, and 48% of natalizumab-treated patients. Both rituximab and natalizumab were associated with a similarly increased adjusted risk of serious infections, including urosepsis and hospitalized UTI-related debility/pseudorelapses, compared with the general population. However, compared with IFN/GLAT, most of these findings were not statistically significant except for rituximab and any serious infection (aHR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.09–1.84). In sensitivity analyses, excluding hospitalizations for UTI-related debility/pseudorelapses, this association was no longer statistically significant (aHR = 1.31 [95% CI = 1.00–1.73], p = 0.05, eTable 4, links.lww.com/NXI/A911).

Table 4.

Number of Events, Crude Incidence Rates, and Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Serious Infections

| No. Events | Person-years | IR per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI)a | aHR (95% CI)b | |

| All serious infections | |||||

| Rituximab | 322 | 6,913.5 | 46.6 (41.5–51.7) | 3.26 (2.69–3.96) | 1.41 (1.09–1.84) |

| Natalizumab | 56 | 1,575.4 | 35.5 (26.2–44.9) | 4.34 (3.00–6.28) | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) |

| IFN/GLAT | 605 | 19,644.6 | 30.8 (28.3–33.3) | 2.31 (2.04–2.62) | Reference |

| Untreated | 1,356 | 17,937.5 | 75.6 (71.6–79.6) | 2.97 (2.65–3.32) | NA |

| General population controls | 2,346 | 238,329.3 | 9.8 (9.4–10.2) | Reference | NA |

| Sepsis | |||||

| Rituximab | 188 | 6,913.5 | 27.2 (23.3–31.1) | 2.32 (1.85–2.90) | 1.34 (0.98–1.84) |

| Natalizumab | 21 | 1,575.4 | 13.3 (7.6–19.0) | 2.46 (1.43–4.23) | 1.10 (0.63–1.91) |

| IFN/GLAT | 284 | 19,644.6 | 14.5 (12.8–16.1) | 1.71 (1.45–2.03) | Reference |

| Untreated | 912 | 17,937.5 | 50.8 (47.5–54.1) | 2.30 (2.01–2.63) | NA |

| General population controls | 1,589 | 238,329.3 | 6.7 (6.3–7.0) | Reference | NA |

| Urosepsis | |||||

| Rituximab | 115 | 6,913.5 | 16.6 (13.6–19.7) | 4.26 (3.14–5.78) | 1.35 (0.89–2.05) |

| Natalizumab | 13 | 1,575.4 | 8.3 (3.8–12.7) | 4.94 (2.60–9.39) | 1.19 (0.61–2.32) |

| IFN/GLAT | 192 | 19,644.6 | 9.8 (8.4–11.2) | 2.92 (2.36–3.61) | Reference |

| Untreated | 618 | 17,937.5 | 34.5 (31.7–37.2) | 4.12 (3.44–4.94) | NA |

| General population controls | 540 | 238,329.3 | 2.3 (2.1–2.5) | Reference | NA |

| UTI/pyelonephritis | |||||

| Rituximab | 77 | 6,913.5 | 11.1 (8.6–13.6) | 12.18 (8.40–17.66) | 1.41 (0.90–2.20) |

| Natalizumab | 27 | 1,575.4 | 17.1 (10.7–23.6) | 16.89 (9.93–28.72) | 1.63 (0.95–2.79) |

| IFN/GLAT | 200 | 19,644.6 | 10.2 (8.8–11.6) | 7.42 (5.92–9.30) | Reference |

| Untreated | 352 | 17,937.5 | 19.6 (17.6–21.7) | 9.65 (7.70–12.10) | NA |

| General population controls | 226 | 238,329.3 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | Reference | NA |

| Pneumonia | |||||

| Rituximab | 37 | 6,913.5 | 5.4 (3.6–7.1) | 1.14 (0.80–1.63) | 0.84 (0.52–1.35) |

| Natalizumab | 8 | 1,575.4 | 5.1 (1.6–8.6) | 1.50 (0.67–3.40) | 1.12 (0.48–2.62) |

| IFN/GLAT | 114 | 19,644.6 | 5.8 (4.7–6.9) | 1.06 (0.84–1.33) | Reference |

| Untreated | 360 | 17,937.5 | 20.1 (18.0–22.1) | 1.66 (1.39–1.97) | NA |

| General population controls | 1,144 | 238,329.3 | 4.8 (4.5–5.1) | Reference | NA |

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals; GLAT = glatiramer acetate; HR = hazard ratios; IFN = interferon-beta; IR = incidence rate; NA = not applicable.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, hospitalization for infection in the previous 5 y.

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, obesity, hospitalization for infection in the previous 5 y, advanced disability, and the previous use of disease-modifying therapies.

Hospitalizations for pneumonia were rare, and neither rituximab nor natalizumab were associated with an increased risk. We identified no cases of PML, and no increased risk of meningitis, encephalitis, or serious herpetic infections across the MS DMT treatment groups (eTable 5, links.lww.com/NXI/A911).

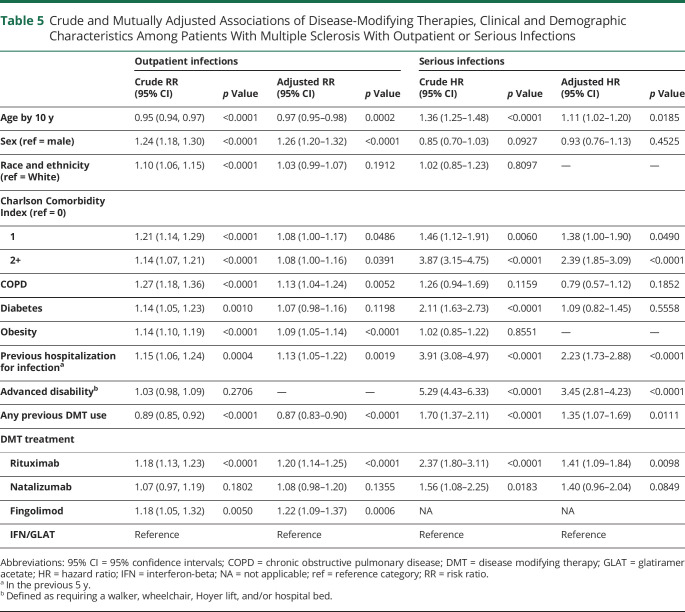

Comorbidities, Advanced Disability, and Infection Risk

Among DMT-treated patients with MS, a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, previous hospitalization for infection, or advanced disability were significant independent risk factors for serious infections (Table 5). The 2- to 3-fold increased risks associated with these factors were higher than treatment with rituximab (aHR = 1.41) or natalizumab (aHR = 1.40). Higher comorbidity index and previous hospitalization for infection were independently associated with higher risk of outpatient infections, albeit with lower magnitudes of effect than serious infections. COPD was an independent risk factor for outpatient infections but not for serious infections when simultaneously adjusting for the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Race and ethnicity were not independently associated with the risk of outpatient or serious infections. Older age was associated with an increased risk of serious and slightly decreased risk of outpatient infections. Female sex was associated with an increased risk of outpatient infections, showed no association with serious infections, and in sensitivity analyses excluding pseudorelapses, was associated with a lower risk of serious infections (eTable 4, links.lww.com/NXI/A911).

Table 5.

Crude and Mutually Adjusted Associations of Disease-Modifying Therapies, Clinical and Demographic Characteristics Among Patients With Multiple Sclerosis With Outpatient or Serious Infections

| Outpatient infections | Serious infections | |||||||

| Crude RR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | p Value | Crude HR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age by 10 y | 0.95 (0.94, 0.97) | <0.0001 | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) | 0.0002 | 1.36 (1.25–1.48) | <0.0001 | 1.11 (1.02–1.20) | 0.0185 |

| Sex (ref = male) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.30) | <0.0001 | 1.26 (1.20–1.32) | <0.0001 | 0.85 (0.70–1.03) | 0.0927 | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | 0.4525 |

| Race and ethnicity (ref = White) | 1.10 (1.06, 1.15) | <0.0001 | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 0.1912 | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | 0.8097 | — | — |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (ref = 0) | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.21 (1.14, 1.29) | <0.0001 | 1.08 (1.00–1.17) | 0.0486 | 1.46 (1.12–1.91) | 0.0060 | 1.38 (1.00–1.90) | 0.0490 |

| 2+ | 1.14 (1.07, 1.21) | <0.0001 | 1.08 (1.00–1.16) | 0.0391 | 3.87 (3.15–4.75) | <0.0001 | 2.39 (1.85–3.09) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 1.27 (1.18, 1.36) | <0.0001 | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) | 0.0052 | 1.26 (0.94–1.69) | 0.1159 | 0.79 (0.57–1.12) | 0.1852 |

| Diabetes | 1.14 (1.05, 1.23) | 0.0010 | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 0.1198 | 2.11 (1.63–2.73) | <0.0001 | 1.09 (0.82–1.45) | 0.5558 |

| Obesity | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | <0.0001 | 1.09 (1.05–1.14) | <0.0001 | 1.02 (0.85–1.22) | 0.8551 | — | — |

| Previous hospitalization for infectiona | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) | 0.0004 | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | 0.0019 | 3.91 (3.08–4.97) | <0.0001 | 2.23 (1.73–2.88) | <0.0001 |

| Advanced disabilityb | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.2706 | — | — | 5.29 (4.43–6.33) | <0.0001 | 3.45 (2.81–4.23) | <0.0001 |

| Any previous DMT use | 0.89 (0.85, 0.92) | <0.0001 | 0.87 (0.83–0.90) | <0.0001 | 1.70 (1.37–2.11) | <0.0001 | 1.35 (1.07–1.69) | 0.0111 |

| DMT treatment | ||||||||

| Rituximab | 1.18 (1.13, 1.23) | <0.0001 | 1.20 (1.14–1.25) | <0.0001 | 2.37 (1.80–3.11) | <0.0001 | 1.41 (1.09–1.84) | 0.0098 |

| Natalizumab | 1.07 (0.97, 1.19) | 0.1802 | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | 0.1355 | 1.56 (1.08–2.25) | 0.0183 | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | 0.0849 |

| Fingolimod | 1.18 (1.05, 1.32) | 0.0050 | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) | 0.0006 | NA | NA | ||

| IFN/GLAT | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

Abbreviations: 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DMT = disease modifying therapy; GLAT = glatiramer acetate; HR = hazard ratio; IFN = interferon-beta; NA = not applicable; ref = reference category; RR = risk ratio.

In the previous 5 y.

Defined as requiring a walker, wheelchair, Hoyer lift, and/or hospital bed.

Discussion

In this large, diverse, real-world population, we found that patients with MS are at significantly higher risk of outpatient and serious infections. The risk of outpatient infections was similarly increased by rituximab, fingolimod, and natalizumab, and serious infections by rituximab and natalizumab compared with IFN/GLAT. Higher comorbidity index, previous hospitalization for infections, and advanced disability significantly increased the risk of serious infections independent of DMT treatment. UTIs resulting in hospitalization for pseudorelapses, a poorly studied problem, accounted for 24%–48% of serious infections. Although not life-threatening, the magnitude of this problem and its impact on patients' quality of life and health systems warrants further study. The only treatment-specific risk identified was fingolimod and herpes infections. We did not find any drug-specific infections associated with rituximab, the most commonly used HET in our health system, including PML or herpetic infections, even though this is the preferred treatment for patients that are JCV antibody positive or have a history of recurrent herpetic infections. Rituximab was associated with an increased risk of UTIs, yeast vaginitis, fungal skin infections, cellulitis, and a slight increased risk of URIs compared with IFN/GLAT. Clinicians and patients should be aware of these relatively high risks of infection and steps to minimize risks including optimizing bladder care, comorbidity prevention, varicella vaccination, minimizing corticosteroid use, and considering discontinuing or avoiding DMT use in patients with advanced disability and/or previous hospitalizations for infections should be discussed.

Comparison of our outpatient infection findings with the sparse existing real-world literature is challenging because previous studies either focused on newly diagnosed4,5 (and presumably less disabled) patients with MS, did not distinguish between DMT treatment or type,4,5 and used unvalidated methods that relied on either ICD codes entered by specialists5 (but not general practitioners) and/or solely on dispensed antibiotic and antiviral prescriptions.1 Because these limitations are likely to underestimate true infection rates, it is perhaps not surprising that our crude outpatient infections rates are higher than in these studies. Nevertheless, there are some striking similarities in the most common types of infections identified in our and the newly diagnosed MS studies,4,5 namely a significantly higher risk of UTIs, skin infections, and URIs compared with non-MS controls.

Another striking similarity between our findings and previous studies is the increased risk of herpetic infections in fingolimod-treated patients. This risk was first identified in RCTs and included 2 fatalities.14 It is common in our practice to either avoid fingolimod use in patients without varicella immunity or recurrent HSV or prescribe antivirals prophylactically. Even in this context and after excluding patients on prophylactic antivirals, some of whom have breakthrough infections, we still found a significantly increased risk of outpatient herpetic infections among fingolimod-treated patients.

The assessment of vaginitis risk, requested by our patient stakeholders, has not been previously addressed in real-world studies. We found that women with MS were at higher risk of yeast vaginitis and BV compared with the general population, and rituximab was associated with an additional increased risk. These analyses have limitations because we did not measure important risk factors including sexual activity or the number of sexual partners, although it is reassuring that we did not find any increased risk of trichomonas vaginitis, a sexually transmitted disease, in women with MS.

Our findings that the use of rituximab and natalizumab increase the risk of serious infections compared with IFN/GLAT or general population controls are generally consistent with the findings from a nationwide Swedish registry-linkage study1—the only other large, real-world comparative safety study of DMTs. Yet, unlike this study,1 we did not identify any clear signal that rituximab was associated with a higher risk of serious infections than natalizumab. We think this is most likely because in our U.S. population, DMTs, including natalizumab, were prescribed to patients who were older, had more comorbidities, and significantly more ambulatory disability than in Sweden,1 all of which are strong independent risk factors for serious infections. These population differences likely contribute to the significantly higher crude serious infection IRs reported even after excluding pseudorelapses compared with the Swedish study1 in the rituximab (34.6 vs 19.71/1,000-PY), natalizumab (18.4 vs 11.41), and IFN/GLAT (20.6 vs 8.91) groups. It is notable that our rituximab crude rates were only slightly higher than those reported in a U.S. referral center-based study (30.5, 95% CI = 24.3–37.8 per 1,000-PY).13 This study reported high usage in patients with advanced disability (24.8%)13 compared with our population (19.7%). The higher rates we observed also likely reflect that we captured all infection-related hospitalizations, not just the first hospitalization.1,13 It should be noted that these analyses did not include hospitalization for COVID-19, the risk of which is clearly elevated by rituximab and other B-cell depleting therapies but not natalizumab use,15 because these results were previously published.16,17

The combined rate of outpatient (17.0/100-PY) and serious infections (15.9/100-PY) reported in a meta-analysis3 of 45 RCTs of FDA-approved DMTs is vastly lower than the rates we observed. Differences in infectious IRs we observed and these RCTs vary by DMT. For example, our study found double the rate of serious infections in natalizumab-treated patients than in RCTs18 and higher rate of outpatient infections compared with fingolimod RCTs.14 The use of natalizumab in patients with advanced disability and comorbidities in our population may explain these differences but nebulous reporting of infectious risks in RCTs may also play a role, such as reporting only selected infections, proportion of patients affected, and/or using intention-to-treat rather than at-risk patients in the denominator, all of which typically underestimate the true rate of infections.14,18 In the future, it would be helpful for DMT RCTs to report the rates of total and specific infections, including those commonly found in patients with MS such as UTIs, URIs, and cellulitis.

Advanced disability was the most important risk factor for serious infections, followed by a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 2 or higher, both of which were larger in magnitude than either treatment with rituximab or natalizumab. Previous hospitalization for infections was also a strong predictor of subsequent serious infections, regardless of DMT choice. Reflecting real-world practices in the United States,19 ∼20% of our population were dependent on a walker, wheelchair, or worse, although there is only weak evidence of benefit of B-cell depleting therapies in walker-dependent but not higher levels of disability, and no evidence of benefit of other DMTs even in walker-dependent pwMS.20 These findings strongly suggest that the risks of DMTs that are highly effective in relapsing forms of MS outweigh the benefits in pwMS with advanced disability, particularly those who have already been hospitalized for infection or have multiple comorbidities. Physicians should counsel patients accordingly and consider discontinuing DMTs in these high-risk populations.

Strengths of this study include comprehensive assessment of infections in a large real-world population that reflects how DMTs are used off-label in patients with MS who are otherwise excluded from RCTs because of high disability, advanced age, and/or comorbidities. The use of validated methods to identify outpatient infections including laboratory-confirmed UTIs; manual chart review of rare, serious infections; comprehensive assessment of comorbidities; and identification of potentially modifiable factors are other notable strengths. Incorporating feedback from our stakeholders illuminated how troublesome outpatient infections are, and led us to examine vaginitis risk for the first time in a large MS population. Last, this study sheds light on how common hospitalization for pseudorelapses (i.e., increased debility) because of uncomplicated UTIs are, a clinically well-recognized but here-to-for vastly understudied problem.

The most important limitations of this study are residual confounding by indication and unmeasured confounders, particularly for varicella zoster where we did not account for vaccination status. It is routine in our practice to avoid natalizumab in JCV antibody-positive patients and fingolimod in patients with recurrent herpes infections. This, along with a relatively small sample of fingolimod- or natalizumab-treated patients, is the most likely reason we did not detect any cases of PML, herpes meningitis, or encephalitis. As with previous MS studies,1,4,5,13 we did not account for corticosteroid use, higher doses of which are known to increase the risk of serious and outpatient infections. This may be an important unmeasured confounder because intermittent corticosteroid use to alleviate pseudorelapse symptoms or improve stamina in patients with advanced disability is a common, albeit highly variable, practice. Residual confounding by advanced disability (i.e., assuming a similar risk of infections in those requiring walkers as bedbound pwMS) may also explain the apparently counterintuitive finding that untreated pwMS have a slightly higher risk of any serious infection and hospitalization for pneumonia than IFN/GLAT-treated patients. Furthermore, 92% of untreated pwMS had previously been treated with IFN/GLAT with discontinuation occurring in a mixture of patients with benign MS21 or progressive, nonrelapsing MS in accordance with the American Academy of Neurology's Choosing Wisely recommendations.22 We also did not measure whether patients were current smokers, a known risk factor for URIs and pneumonia. Last, although the average time on DMT (2.5–3 years) was longer than in RCTs, we may still have underestimated infections that increase with higher cumulative dose or longer duration of therapies. These limitations should be addressed in future studies.

Our study emphasizes that infectious morbidity, which is already high in patients with MS, is further increased with rituximab, fingolimod, and to a slightly lesser extent, natalizumab use. In patients with advanced disability from progressive, nonrelapsing forms of MS, the use of DMTs should be strongly reconsidered because there is no evidence of benefit, and this study highlights the relatively high risk of serious infections. The high effectiveness of these treatments in relapsing forms of MS means that identifying strategies to reduce the risks of infections are of vital importance now and for the foreseeable future. Taken together with the existing literature, our study suggests that effective strategies to reduce UTIs (and thereby urosepsis), preventing comorbidities, and varicella vaccinations along with minimizing corticosteroid use may all be particularly impactful. Future studies of efficient interventions, including at the health systems level, to reduce infection risks are needed.

Acknowledgment

The authors are extremely grateful to all of our stakeholders, patients, family members, clinicians, and MS advocacy groups for their invaluable input.

Glossary

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratios

- aRR

adjusted risk ratios

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- DMTs

disease-modifying therapies

- EHR

electronic health record

- KPSC

Kaiser Permanente Southern California

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PML

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- RCTs

randomized controlled trials

- UTIs

urinary tract infections

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Annette M. Langer-Gould, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Los Angeles Medical Center, Southern California Permanente Medical Group | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Jessica B. Smith, MPH | Department of Research and Evaluation, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Pasadena | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Edlin G. Gonzales, MA | Department of Research and Evaluation, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Pasadena | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content, and major role in the acquisition of data |

| Fredrik Piehl, MD, PhD | Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Bonnie H. Li, MS | Department of Research and Evaluation, Southern California Permanente Medical Group, Pasadena | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Program Award (MS-1511-33196).

Disclosure

A. Langer-Gould has received grant support and awards from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the National MS Society. She currently serves as a voting member on the California Technology Assessment Forum, a core program of the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). She has received sponsored and reimbursed travel from ICER; F. Piehl has received research grants from Merck KGaA and UCB and fees for serving on DMC in clinical trials with Chugai, Lundbeck, and Roche; J.B. Smith reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; E.G. Gonzales reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; and B.H. Li reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Luna G, Alping P, Burman J, et al. Infection risks among patients with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod, natalizumab, rituximab, and injectable therapies. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(2):184-191. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otero-Romero S, Sanchez-Montalva A, Vidal-Jordana A. Assessing and mitigating risk of infection in patients with multiple sclerosis on disease modifying treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17(3):285-300. doi: 10.1080/1744666x.2021.1886924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prosperini L, Haggiag S, Tortorella C, Galgani S, Gasperini C. Age-related adverse events of disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis: a meta-regression. Mult Scler. 2021;27(9):1391-1402. doi: 10.1177/1352458520964778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persson R, Lee S, Ulcickas Yood M, et al. Infections in patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis: a multi-database study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;41:101982. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.101982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castelo-Branco A, Chiesa F, Conte S, et al. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: a national cohort study in Sweden. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;45:102420. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16(3):37-41. doi: 10.7812/tpp/12-031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(17)30470-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer-Gould A, Lucas R, Xiang AH, et al. MS Sunshine Study: sun exposure but not vitamin D is associated with multiple sclerosis risk in blacks and hispanics. Nutrients. 2018;10(3):268. doi: 10.3390/nu10030268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culpepper WJ, Marrie RA, Langer-Gould A, et al. Validation of an algorithm for identifying MS cases in administrative health claims datasets. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1016-e1028. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000007043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Hum. an Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0 [PDF]; 2017. Accessed March 30, 2023. ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JB, Li BH, Gonzales EG, Langer-Gould A. Validation of algorithms for identifying outpatient infections in MS patients using electronic medical records. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;57:103449. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer BL, Wallach AI, Corboy JR, Dubovskaya K, Alvarez E, Kister I. Serious safety events in rituximab-treated multiple sclerosis and related disorders. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020;7(9):1477-1487. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.GILENYA (fingolimod. Novartis Phramaceuticals Corporation; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sormani MP, De Rossi N, Schiavetti I, et al. Disease-modifying therapies and coronavirus disease 2019 severity in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2021;89(4):780-789. doi: 10.1002/ana.26028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer-Gould A, Smith JB, Li BH, KPSC MS Specialist Group. Multiple sclerosis, rituximab, and COVID-19. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8(4):938-943. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JB, Gonzales EG, Li BH, Langer-Gould A. Analysis of rituximab use, time between rituximab and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and COVID-19 hospitalization or death in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2248664. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.48664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.TYSABRI (natalizumab). Biogen Idec Inc.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smoot K, Chen C, Stuchiner T, Lucas L, Grote L, Cohan S. Clinical outcomes of patients with multiple sclerosis treated with ocrelizumab in a US community MS center: an observational study. BMJ Neurol Open. 2021;3(2):e000108. doi: 10.1136/bmjno-2020-000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Siponimod for the Treatment of Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: Effectiveness and Value. Final Evidence Report; 2019. Accessed June 12, 2023. icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_MS_Final_Evidence_Report_062019.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McFaul D, Hakopian NN, Smith JB, Nielsen AS, Langer-Gould A. Defining benign/burnt-out MS and discontinuing disease-modifying therapies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(2):e960. doi: 10.1212/nxi.0000000000000960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer-Gould AM, Anderson WE, Armstrong MJ, et al. The American Academy of Neurology's top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology. 2013;81(11):1004-1011. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0b013e31828aab14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Owing to the KPSC Institutional Review Board, data are available upon reasonable request.