Abstract

A clinical strain of Proteus mirabilis (CF09) isolated from urine specimens of a patient displayed resistance to amoxicillin (MIC >4,096 μg/ml), ticarcillin (4,096 μg/ml), cefoxitin (64 μg/ml), cefotaxime (256 μg/ml), and ceftazidime (128 μg/ml) and required an elevated MIC of aztreonam (4 μg/ml). Clavulanic acid did not act synergistically with cephalosporins. Two β-lactamases with apparent pIs of 5.6 and 9.0 were identified by isoelectric focusing on a gel. Substrate and inhibition profiles were characteristic of an AmpC-type β-lactamase with a pI of 9.0. Amplification by PCR with primers for ampC genes (Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, and Citrobacter freundii) of a 756-bp DNA fragment from strain CF09 was obtained only with C. freundii-specific primers. Hybridization results showed that the ampC gene is only chromosomally located while the TEM gene is plasmid located. After cloning of the gene, analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence (1,146 bp) showed that this ampC gene is close to blaCMY-2, from which it differs by three point mutations leading to amino acid substitutions Glu → Gly at position 22, Trp → Arg at position 201, and Ser → Asn at position 343. AmpC β-lactamases derived from that of C. freundii (LAT-1, LAT-2, BIL-1, and CMY-2) have been found in Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli, and Enterobacter aerogenes and have been reported to be plasmid borne. This is the first example of a chromosomally encoded AmpC-type β-lactamase observed in P. mirabilis. We suggest that it be designated CMY-3.

Resistance to β-lactams in Proteus mirabilis strains is principally due to TEM production, with a high prevalence of TEM-2 (26). Extended-spectrum β-lactamases TEM-3 (10, 24), TEM-10 (27), or PER-2 (4) and, recently, inhibitor-resistant TEM (IRT-13/TEM-44) (8) have also been observed in this species. Chromosomal cephalosporinase has not been reported in P. mirabilis strains. Bush group 1 β-lactamases (9) are encoded by chromosomally located bla genes in Enterobacteriaceae, principally in Enterobacter, Serratia, Citrobacter, and Providencia species and Escherichia coli. These enzymes, belonging to class C β-lactamases (1), are cephalosporinases not inhibited by clavulanic acid. Plasmid-mediated class C β-lactamases have been recently reported in Klebsiella pneumoniae (3, 5, 7, 13–15, 28, 34), E. coli (7, 11) Enterobacter aerogenes (13), and Salmonella species (2, 18). These β-lactamases show sequence similarities to AmpC β-lactamases either of Enterobacter cloacae (ACT-1, and MIR-1) (7, 28), of Citrobacter freundii (CMY-2, BIL-1, LAT-2, and LAT-1) (3, 11, 13, 34), or of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CMY-1, FOX-1, and MOX-1) (5, 14, 15).

We describe here a chromosomally encoded class C β-lactamase that may be derived from AmpC β-lactamase of C. freundii, produced by a clinical strain of P. mirabilis resistant to all penicillins and cephalosporins, including cephamycins and aztreonam.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

P. mirabilis CF09, producing TEM-2 and the novel β-lactamase, was isolated from urine specimens of a patient hospitalized in a neurology unit of the teaching hospital of Clermont-Ferrand (France). P. mirabilis ATCC 103181T and E. coli JM109 were used as recipient strains, respectively, for transfer experiments by conjugation and for transformation after cloning experiments. C. freundii OS60, E. cloacae P99, and E. coli K-12 were used as positive controls for DNA amplification by PCR with ampC-specific primers. E. coli RP4 (TEM-2) and C. freundii OS60 were used as positive controls, and P. mirabilis ATCC 103181T was used as a negative control for DNA-DNA hybridizations.

Susceptibility to β-lactams.

MICs of amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml), ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid (clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml), cephalothin, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, and imipenem were determined by dilution in Mueller-Hinton agar (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) with an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot. Antibiotics were provided as powders by SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals (amoxicillin, ticarcillin, and clavulanic acid), Roussel-Uclaf (cefotaxime), Glaxo Wellcome Research and Development (ceftazidime), Bristol-Myers Squibb (aztreonam), and Merck Sharp and Dohme-Chibret (cefoxitin and imipenem).

Isoelectric focusing.

Isoelectric focusing was performed with polyacrylamide gels containing ampholines with a pH range of 3.5 to 10, as previously described (32). β-Lactamases with known pIs, TEM-1 (5.4), TEM-2 (5.6), SHV-5 (8.2), and MEN-1 (8.6), were used as standards.

Conjugation experiments.

Conjugation experiments were performed for 40 min at 37°C for strain CF09 with recipient strain P. mirabilis ATCC 103181T, resistant to rifampin. The transconjugants were selected on agar containing rifampin (300 μg/ml) and ceftazidime (16 μg/ml) and on agar containing rifampin (300 μg/ml) and ticarcillin (128 μg/ml).

Determination of β-lactamase kinetic constants Km, Ki, and relative Vmax.

Affinity Km and relative Vmax values were obtained with highly purified extracts (≥97% pure) by a computerized microacidimetric method (19). The Km and relative Vmax values of the AmpC-type β-lactamase produced by P. mirabilis CF09 were determined for penicillins and cephalosporins. The inhibition constants (Ki) with clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam were determined by competition procedures with cephaloridine.

DNA amplification.

DNA amplification with crude extract of P. mirabilis CF09 as a template was performed by PCR (29) in a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR System 2004 DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus Instruments) with a symmetric ratio of consensus primers CF-A and CF-B, specific for the ampC genes of C. freundii, consensus primers EC-A and EC-B, specific for the ampC genes of E. cloacae, primers COL-A and COL-B, specific for the ampC gene of E. coli K-12 (Table 1), and primers 5′-CS and 3′-CS, specific for the 5′ and 3′ conserved segments of integrons previously described (20). Annealing temperatures were 54°C for primers CF-A and CF-B, 62°C for primers EC-A and EC-B, 58°C for primers COL-A and COL-B, and 50°C for primers 5′-CS and 3′-CS.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of the oligonucleotides used for amplification and/or sequencing reactions

| Application and primer name a | Sequenceb | Nucleotide positionc |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification and sequencing | ||

| CF-A | 5′-d[ATTCCGGGTATGGCCGT]-3′ | 175 |

| CF-B | 5′-d[GGGTTTACCTCAACGGC]-3′ | 1010 |

| Sequencing | ||

| CF-C | 5′-d[ATCGGCTTTACCCCAGGT]-3′ | 243 |

| CF-D | 5′-d[ATCAAGGGCAGCGACAGC]-3′ | 952 |

| Amplification | ||

| EC-A | 5′-d[CCCTTTGCTGCGCCCTGC]-3′ | 57 |

| EC-B | 5′-d[TGCCGCCTCAACGCGTGC]-3′ | 1162 |

| COL-A | 5′-d[ACGACGCTCTGCGCCTTA]-3′ | 69 |

| COL-B | 5′-d[AAGAATCTGCCAGGCGGC]-3′ | 1178 |

Primers CF-A and CF-B are consensus sequences of the ampC genes of C. freundii OS60 (21) and C. freundii GN346 (33) and genes encoding LAT-1 (34), LAT-2 (13), BIL-1 (11), and CMY-2 (3). Primers EC-A and EC-B are consensus sequences of the ampC genes of E. cloacae P99, E. cloacae MHN-1, and E. cloacae Q908R (12). Primers COL-A and COL-B are specific to the ampC gene of E. coli K-12 (16).

Primers CF-A, CF-D, EC-A, and COL-A are identical to the leading strand; primers CF-B, CF-C, EC-B, and COL-B are identical to the lagging strand.

DNA preparation.

Plasmid DNA preparation was performed by alkaline lysis, as previously described by Kado and Liu (17). Chromosomal DNA preparation was performed by lysis with lysozyme, proteinase K, and Sarkosyl, as described by Sambrook et al. (30). Chromosomal DNA was obtained by centrifugation in a cesium chloride density gradient with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. The viscous fraction containing chromosomal DNA was collected by dripping through a large needle inserted into the side of the tube and dialyzed.

Probe preparation.

A blaTEM internal fragment of 328 bp was amplified as previously described (32). An ampC 756-bp DNA fragment was amplified by PCR with C. freundii OS60 as the template and with ampC-specific primers CF-A and CF-B. These two probes were labeled with [α-32P]dATP, as previously described (32).

DNA-DNA hybridizations.

Total chromosomal and plasmid DNA from P. mirabilis CF09 were hybridized with the blaTEM and ampC probes, as previously described (32), by dot blotting on a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham International). E. coli RP4 (TEM-2) and C. freundii OS60 were used as positive controls, and P. mirabilis ATCC 103181T was used as a negative control.

Cloning experiments.

Cloning experiments were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (30). CF09 chromosomal DNA was digested with HindIII (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France). Ligation to vector pACYC 184 was followed by electrotransformation of E. coli JM109. E. coli transformants were selected on Mueller-Hinton agar containing ceftazidime (16 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml).

Sequencing.

Sequencing of the internal 756-bp DNA fragment was performed by the dideoxy chain termination procedure of Sanger et al. (31) on an ABI377 automatic sequencer using the ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS (Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems division, Foster City, Calif.) and primers CF-A and CF-B (Table 1). Complete sequencing of the gene and of the flanking regions was obtained with primers CF-C and CF-D (Table 1), whose sequences were determined from the nucleotide sequence of the internal 756-bp DNA fragment.

RESULTS

Cloning experiments.

An E. coli JM109 clone harboring a recombinant plasmid with a DNA insert of approximately 5 kb (pPM1) was obtained. This clone, designated E. coli JM109(pPM1), was kept for further analysis. Resistance phenotyping, isoelectric focusing, and amplification by PCR with C. freundii ampC-specific primers (CF-A and CF-B) confirmed the presence of the ampC gene in E. coli JM109(pPM1).

Conjugation experiments.

Plasmid DNA from P. mirabilis CF09 was transferred by conjugation into P. mirabilis ATCC 103181T. A transconjugant (TrCF029) was obtained only on agar containing rifampin and ticarcillin. It was resistant to penicillins, and the bla gene, encoding the β-lactamase produced, was identical to the blaTEM-2 gene, as confirmed by sequencing (data not shown).

β-Lactamase characterization.

Two β-lactamase bands, of pI 5.6 and 9.0, were observed by isoelectric focusing in P. mirabilis CF09; only one band, of pI 9.0, in E. coli JM109(pPM1) and one band, of pI 5.6, in the transconjugant TrCF029 were observed.

Susceptibility to β-lactams.

P. mirabilis CF09 and E. coli JM109(pPM1) were characterized by high levels of resistance to cephalothin (>1,024 and >1,024 μg/ml, respectively), cefoxitin (64 and 128 μg/ml), and broad-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, 256 and 16 μg/ml; ceftazidime, 128 and 64 μg/ml) (Table 2). Clavulanic acid did not act synergistically with cephalosporins for either strain. A low synergistic effect was observed only with penicillins for the clinical strain CF09, which produced a TEM-2 enzyme in addition to the AmpC-type β-lactamase. The cephalosporin resistance phenotype of E. coli JM109(pPM1) was similar to that of E. coli DH5α T+(pPMV2), described elsewhere (3), which produces enzyme CMY-2 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

MICs of β-lactams for P. mirabilis CF09, clone E. coli JM109(pPM1) harboring recomibinant plasmid pPM1, recipient strain E. coli JM109, and clone E. coli DH5α T+ producing CMY-2 (3).

| Antibiotic | MIC fora:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. mirabilis CF09 (CMY-3 and TEM-2) | E. coli JM109(pPM1) (CMY-3) | E. coli JM109 | E. coli DH5α T+ (CMY-2)b | |

| Amoxicillin | >4,096 | 1,024 | 2 | NR |

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (2 μg/ml)c | 1,024 | 1,024 | 2 | NR |

| Ticarcillin | 4,096 | 1,024 | 1 | NR |

| Ticarcillin + clavulanic acid (2 μg/ml)c | 128 | 512 | 0.5 | NR |

| Cephalothin | >1,024 | >1,024 | 2 | NR |

| Cefoxitin | 64 | 128 | 1 | 256 |

| Cefotaxime | 256 | 16 | ≤0.12 | 16 |

| Ceftazidime | 128 | 64 | ≤0.12 | 128 |

| Aztreonam | 4 | 32 | ≤0.12 | 64 |

| Imipenem | 4 | 0.25 | ≤0.12 | 0.5 |

Data in parentheses following strain designations are enzymes, where applicable.

Data are from Bauernfeind et al. (3). NR, not reported.

Clavulanic acid did not improve the MICs of the different cephalosporins and aztreonam (data not shown).

Kinetic constants.

The kinetic parameters (Km, Ki, and Vmax) of the AmpC-type β-lactamase produced by strain CF09 (Table 3) were similar to those reported for cephalosporin-hydrolyzing β-lactamases poorly inhibited by clavulanic acid (Bush group 1 β-lactamases) (9).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of the β-lactamase CMY-3

| Antibiotic | Vmaxa | Km or Kib |

|---|---|---|

| β-Lactams | ||

| Cephaloridine | 100 | 90 |

| Cephalothin | 110 | 40 |

| Cefoperazone | 15 | 10 |

| Cefotaxime | <0.1 | 0.5 |

| Ceftazidime | <0.1 | 115 |

| Aztreonam | <0.1 | 0.01 |

| Moxalactam | <0.1 | 0.005 |

| Cefoxitin | <0.1 | 0.2 |

| Benzylpenicillin | 5 | 3 |

| Amoxicillin | 1 | ND |

| Ticarcillin | <0.1 | ND |

| Piperacillin | <0.1 | ND |

| Cloxacillin | <0.1 | 0.04 |

| β-Lactamase inhibitors | ||

| Clavulanic acid | 140 | |

| Sulbactam | 10 | |

| Tazobactam | 10 |

Vmax values are given as percentages of cephaloridine (100%).

Km (for β-lactams) and Ki (for β-lactamase inhibitors) values are in micromolar units. ND, not determined.

DNA amplification.

Amplification of CF09 DNA with the ampC-specific primers was successful only with C. freundii-specific primers CF-A and CF-B (Table 1) and, as expected, a 756-bp DNA fragment was obtained. No DNA amplification was obtained with integron-specific primers 5′-CS and 3′-CS.

Sequencing.

The complete nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the AmpC-type β-lactamase was obtained with the recombinant plasmid pPM1 and primers CF-A, CF-B, CF-C, and CF-D (Table 1). The nucleotide sequence of this bla gene differs from blaCMY-2 by three point mutations, A → G at position 167, T → C at position 703, and G → A at position 1130, leading to amino acid substitutions Glu → Gly at position 22, Trp → Arg at position 201, and Ser → Asn at position 343 (Table 4). Sequencing of about 1,080 bp of each side of the flanking regions was obtained. No inverted repeated sequences suggestive of a transposable element and no sequences evoking a 59-base element specific to a gene cassette were observed.

TABLE 4.

Nucleotide and amino acid substitutions between blaCMY-2 and blaCMY-3

| Gene (enzyme) | Nucleotide (amino acid)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 167 (22) | 703 (201) | 1130 (343) | |

| blaCMY-2 (CMY-2) | A (Glu) | T (Trp) | G (Ser) |

| blaCMY-3 (CMY-3) | G (Gly) | C (Arg) | A (Asn) |

Nucleotide and amino acid numbering are according to the nucleotide sequence of the ampC gene and the amino acid sequence of the AmpC β-lactamase, respectively, of C. freundii OS60 (21).

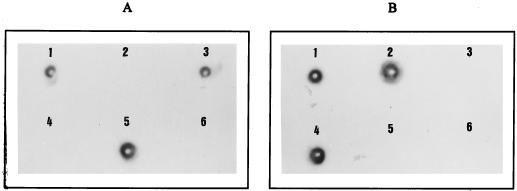

DNA-DNA hybridizations.

Total DNA of P. mirabilis CF09 hybridized with the blaTEM and the ampC probes. The ampC probe hybridized with chromosomal DNA of strain CF09, and the blaTEM probe hybridized with plasmid DNA of strain CF09 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

DNA-DNA hybridizations, by dot blotting on a nylon membrane, of total, chromosomal, and plasmid DNA from P. mirabilis CF09 with the blaTEM probe (A) and the C. freundii ampC probe (B). 1, Total DNA from strain CF09; 2, chromosomal DNA from strain CF09; 3, plasmid DNA from strain CF09; 4, total DNA from C. freundii OS60; 5, total DNA from E. coli RP4(TEM-2); 6, total DNA from P. mirabilis ATCC 103181T.

DISCUSSION

Wild-type strains of P. mirabilis are susceptible to all penicillins and cephalosporins. TEM or TEM-derived β-lactamases in this species have been previously described, and no chromosomally encoded β-lactamase production has been reported. The β-lactamase CEP-1 produced by a clinical strain of P. mirabilis was the first plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase reported (6), but the nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding this enzyme has not been determined. Since 1990, several plasmid-mediated AmpC-type β-lactamases have been characterized, mainly in K. pneumoniae (3, 5, 7, 13–15, 28, 34) but also in E. coli (7, 11) E. aerogenes (13), and Salmonella species (2, 18). They confer a β-lactam resistance phenotype resembling that conferred by derepressed cephalosporinase. This resistance to β-lactams is not reversed by clavulanic acid. These enzymes originate from the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases of C. freundii, E. cloacae, or P. aeruginosa. The enzymes that originate from C. freundii (LAT-1, LAT-2, CMY-2, and BIL-1) or from E. cloacae (MIR-1 and ACT-1) have high homologies, about 90%, with their parent AmpC enzyme (5, 7, 13), while MOX-1, FOX-1, and CMY-1 have homologies of only 55% with the AmpC β-lactamase of P. aeruginosa (5).

We describe a clinical strain of P. mirabilis which expresses an unusual resistance phenotype, with high-level resistance to β-lactams and other antibiotics including aminoglycosides (except amikacin), fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim, and sulfamethoxazole. This strain produces two β-lactamases, a TEM-2 enzyme and an AmpC-type β-lactamase. Production of this AmpC β-lactamase by E. coli JM109(pPM1), which harbors the recombinant plasmid pPM1, confers high-level resistance to amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid, all the cephalosporins investigated, and aztreonam (Table 2). The MICs of cephalosporins for E. coli JM109(pPM1) are similar to those reported by Bauernfeind et al. (3) for E. coli DH5α T+(pPMV2), which produces only CMY-2.

The amino acid sequence of the AmpC-type β-lactamase produced by strain CF09 is close to that of CMY-2, from which it differs by three amino acid substitutions: Glu → Gly-22, Trp → Arg-201, and Ser → Asn-243. It is unlikely that the substitutions of Gly for Glu-22 and Arg for Trp-201, which occur far from the active site, affect the catalytic properties of the enzyme. Substitution of Asn for Ser-343 has been previously described for the amino acid sequences of the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases of E. coli K-12 (16) and P. aeruginosa (23) and of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases FOX-1 (14) and CMY-1 (5). Although Ser-343 is close to Ser-318, which follows box 7 (KTG triad beginning at position 315) (22, 25), this substitution probably has no effect on catalytic properties.

CMY-2 is a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase that has been described for K. pneumoniae and which originates from the chromosomal β-lactamase of C. freundii (3). A plasmid carrying blaCMY-2 was recently observed in C. freundii and was transferable to K. pneumoniae and E. coli (3), which explains why this gene can be observed in Enterobacteriaceae other than C. freundii. Our results show that the gene encoding the AmpC-type β-lactamase produced by P. mirabilis CF09 is only chromosomally located. We suggest that the ampC gene migrated like blaCMY-2 from the chromosome of C. freundii to a plasmid with a transposon as the vehicle. This plasmid might be transferred in P. mirabilis CF09; hence, we hypothesize that the CF09 ampC gene could be in turn transposed from the plasmid to the chromosome, as previously suggested for ACT-1 (7). We did not observe a P. mirabilis strain harboring a plasmid encoding the CF09 AmpC β-lactamase, which suggests that the replication of β-lactamase-encoding plasmids could be as problematic as their transfer in this species (24).

Preliminary results of sequencing of the flanking regions of the gene encoding the AmpC β-lactamase produced by strain CF09 (about 1,080 bp on each side) did not show inverted repeated sequences suggestive of the presence of a transposable element. This ampC gene was probably not inserted in an integron, since a short imperfect inverted repeat element called 59-base element (specific to gene cassettes inserted in integron structures) was not observed on the flanking regions. Moreover, amplification by PCR with primers specific to the 5′ and 3′ conserved segments of integrons was unsuccessful. Further studies on these flanking regions are in progress.

Chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases of C. freundii or E. cloacae are regulated by a trans-acting protein, AmpR, which is encoded by the ampR gene immediately upstream of the ampC β-lactamase gene. In the absence of an inducer, AmpR represses the synthesis of the β-lactamase. No plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase except DHA-1 (2) has an ampR regulatory gene. Sequencing of the flanking regions of the gene encoding the AmpC β-lactamase produced by strain CF09, as for blaCMY-2, did not show homology with an ampR regulatory gene. The lack of an ampC regulator could explain the β-lactam resistance phenotype conferred by the production of these plasmid-mediated β-lactamases, which is close to that conferred by derepressed cephalosporinase production.

Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases have been reported increasingly since 1990, principally in species which do not produce an inductible chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase. Three outbreaks of Enterobacteriaceae producing AmpC plasmid-mediated β-lactamases have been reported (7, 13, 28). The other plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases were observed sporadically (3, 5, 14, 15, 34). Production of these plasmid-mediated enzymes was probably underestimated in C. freundii, Enterobacter species, and Serratia species, owing to the presence of a chromosomal cephalosporinase, which can be derepressed. Hence, detection of a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase in these species is more difficult.

This is the first report of an AmpC-type β-lactamase produced by a clinical strain of P. mirabilis from France. This enzyme, which is only chromosomally, encoded, could be designated CMY-3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rolande Perroux, Marlene Jan, and Dominique Rubio for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Direction de la Recherche et des Etudes Doctorales, Ministère de l’Education Nationale, Paris, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnaud G, Arlet G, Gaillot O, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Program and abstracts of the 16th Interdisciplinary Meeting on Anti-Infectious Chemotherapy. Paris, France. 1996. A novel AmpC plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with the AmpR gene in Salmonella enteritica (serovar enteritidis), abstr. 26/C3; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Giamarellou H. Characterization of the plasmidic β-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:221–224. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Mangold P, Amann S, Akalin E, Ang O, Bal C, Casellas J M. Characterization of β-lactamase gene blaPER-2, which encodes an extended-spectrum class A β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:616–620. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Wilheim R, Chong Y. Comparative characterization of the cephamycinase blaCMY-1 gene and its relationship with other β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1926–1930. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobrowski M M, Matthew M, Barth P T, Datta N, Grinter N J, Jacob A E, Kontomichalou P, Dale J W, Smith J T. Plasmid-determined β-lactamase indistinguishable from the chromosomal β-lactamase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1976;123:149–157. doi: 10.1128/jb.125.1.149-157.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford P A, Urban C, Mariano N, Projan S J, Rahal J J, Bush K. Imipenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with the combination of ACT-1, a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase, and the loss of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:563–569. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bret L, Chanal C, Sirot D, Labia R, Sirot J. Characterization of an inhibitor-resistant enzyme IRT-2 derived from TEM-2 β-lactamase produced by Proteus mirabilis strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:183–191. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chanal C, Sirot D, Romaszko J P, Bret L, Sirot J. Survey of prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:127–132. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fosberry A P, Payne D J, Lawlor E J, Hodgson J E. Cloning and sequence analysis of blaBIL-1, a plasmid-mediated class C β-lactamase gene in Escherichia coli BS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1182–1185. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galleni M, Lindberg F, Normark S, Cole S, Honore S, Joris B, Frere J M. Sequence and comparative analysis of three Enterobacter cloacae ampC β-lactamase genes and their product. Biochem J. 1988;250:753–760. doi: 10.1042/bj2500753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gazouli M, Tzouvelekis L S, Prinarakis E, Miriagou V, Tzelepi E. Transferable cefoxitin resistance in enterobacteria from Greek hospitals and characterization of a plasmid-mediated group 1 β-lactamase (LAT-2) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1736–1740. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez Leiza M, Perez-Diaz J C, Ayala J, Casellas J M, Martinez-Beltran J, Bush K, Baquero F. Gene sequence and biochemical characterization of FOX-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae, a new AmpC-type plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with two molecular variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2150–2157. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horii T, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Ichiyama S, Wacharotayankun R, Kato N. Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase isolated from Klebsiella pneumoniae confers resistance to broad-spectrum β-lactams, including moxalactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:984–990. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaurin B, Grundström T. ampC cephalosporinase of Escherichia coli K-12 has different evolutionary origin from that of the penicillinase type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4897–4901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kado C I, Liu S T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koeck J L, Arlet G, Philippon A, Basmaciogullari S, Thien H V, Buisson Y, Cavallo J D. Abstracts of the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Novel plasmid-mediated AmpC-type β-lactamase (SAL-1) in a clinical isolate of Salmonella senftenberg, abstr. C29; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labia R, Andrillon J, Le Goffic F. Computerized microacidimetric determination of β-lactamase Michaelis-Menten constants. FEBS Lett. 1973;33:42–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque C, Piche L, Larose C, Roy P H. PCR mapping of integrons reveals several novel combinations of resistance genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:185–191. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg F, Normark S. Sequence of the Citrobacter freundii OS60 chromosomal ampC β-lactamase gene. Eur J Biochem. 1986;156:441–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lobkovsky E, Moews P C, Liu H, Zhao H, Frere J M, Knox J R. Evolution of an enzyme activity: crystallographic structure at 2-Å resolution of cephalosporinase from the amps gene of Enterobacter cloacae P99 and comparison with a class A penicillinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11257–11261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lodge J M, Minchin S D, Piddock L J V, Busby S J. Cloning, sequencing and analysis of the structural gene and regulatory region of the P. aeruginosa chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase. Biochem J. 1990;272:627–631. doi: 10.1042/bj2720627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mariotte S, Nordmann P, Nicolas M H. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Proteus mirabilis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:925–935. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.5.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oefner C, D’Arcy A, Daly J J, Gubernator K, Charnas R L, Heinze I, Hubschwerlen C, Winkler F K. Refined crystal structure of β-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii indicates a mechanism for β-lactam hydrolysis. Nature. 1990;343:284–288. doi: 10.1038/343284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouellette M, Paul G C, Philippon A M, Roy P H. Oligonucleotide probes (TEM-1, OXA-1) versus isoelectric focusing in β-lactamase characterization of 114 resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:397–399. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palzkill T, Thomson K S, Sanders C C, Moland E S, Huang W, Milligan T W. New variant of TEM-10 β-lactamase gene produced by a clinical isolate of Proteus mirabilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1199–1200. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papanicolaou G A, Medeiros A A, Jacoby G A. Novel plasmid-mediated β-lactamase (MIR-1) conferring resistance to oxyimino- and α-methoxy β-lactams in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2200–2209. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sirot D, Chanal C, Henquell C, Labia R, Sirot J, Cluzel R. Clinical isolates of Escherichia coli producing multiple TEM-mutants resistant to β-lactamase inhibitors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:1117–1126. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukamoto K, Tachibana K, Yamazaki N, Ishii Y, Ujiie K, Nishida N, Sawai T. Role of lysine-67 in the active site of class C β-lactamase from Citrobacter freundii GN346. Eur J Biochem. 1990;188:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzouvelekis L S, Tzelepi E, Mentis A F, Tsakris A. Identification of a novel plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with chromosomal cephalosporinase characteristics from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:645–654. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]