Abstract

This study explored the influence of neighborhood residential density, physical and social environments on physical activity of older adults in Metro Vancouver, British Columbia and Metro Portland, Oregon. Eight neighborhoods in the two metropolitan regions were selected based on varying population density and income levels. Photovoice method was used with sixty-six older adult participants across the neighborhoods. Data were analyzed to explore any possible differences in the physical or social environmental aspects perceived as barriers or facilitators to physical activity between the higher and lower density neighborhoods. Four themes emerged based on a systematic analysis of the participant-taken photographs, participants’ descriptions of photographs and group discussions. These themes were: safety and security, accessibility, comfort of movement, and peer support. Although a few themes were common across the eight neighborhoods, there were also differences between neighborhoods of varying residential density and across the two metro areas. More negative issues were reported concerning traffic hazards and personal safety in the higher density neighborhoods compared to the lower density neighborhoods. Also, a more positive outlook on public transportation was noted in the higher density neighborhoods. Across the two regions, differences were noted regarding private transportation, intergenerational activities and volunteering.

Introduction

In North America, the fastest growing segment of the population is older adults. In the United States (with similar figures in Canada), the older adult population is projected to grow by 2.6% annually between 2010 and 2030; while the population under 65 will decline by an average of 0.2% annually (U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, 1998). There is a staggering rise in overweight and obesity incidence among older adults and aging baby boomers (Kaplan, Huguet, Newsom, McFarland, & Lindsay, 2003; Wister, 2005). Despite this, the majority of older adults (57%) have been classified as inactive (Statistics Canada, 2006). Inactivity has important health and well-being implications for older adults, as inactive older adults have an increased risk of falling, of developing chronic health conditions, and experiencing a lower quality of life compared to active seniors (Lockett, Willis, & Edwards, 2005). A substantial body of evidence indicates that regular engagement in moderate-intensity physical activity on most days of the week is sufficient for older adults to achieve positive health outcomes (Blumenthal & Gullette, 2002; Division of Aging & Seniors, 2001; Li et al., 2005). Regular participation in physical activity for leisure, transportation or household activities could prevent, delay, or significantly minimize negative effects associated with chronic conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes) commonly experienced in later life (e.g., Colman & Walker, 2004; Seefeldt, Malina, & Clark, 2002). Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that older adults who engage in regular physical activity benefit from increased psychological well-being in various health-related quality of life domains including emotional, cognitive and social functioning (Acree et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2004; White, Wójcicki, & McAuley, 2009).

Physical activity accomplished as part of daily life, such as walking for travel or recreation is an excellent strategy to increase seniors’ physical activity levels, and usually occurs within one’s neighborhood environment (Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2003). Studies have shown that features of the built environment can affect the level of physical activity in all ages (Berke, Koepsell, Moudon, Hoskins, & Larson, 2007; Cervero & Radisch, 1996; Frank & Pivo, 1994). It has been suggested that promoting a safe environment among older adults may also increase their levels of physical activity (Li et al., 2005). In order to promote active living, people need to be supported and encouraged by their physical and social environments (Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2003). However, few studies have investigated the impact of the neighborhood built and social environment on the physical activity of older adults.

The neighborhood environment becomes increasingly salient to older adults who face multiple personal and social changes that often limit daily activities to their immediate or nearby surroundings (Dobson & Gilron, 2009; Glass & Balfour, 2003). Physical activity that is accomplished as part of daily life, such as walking for travel or recreation, usually occurs within one’s neighborhood (Giles-Corti & Donovan, 2002; Troped et al., 2001) and these habitual forms of physical activities represent key sources of exercise for older adults (Li et al., 2005). Accordingly, neighborhood built environments can offer significant potential to promote physical activity, particularly among older adult populations, by providing safe and accessible venues for such activities (Ball, Bauman, Leslie, & Owen, 2001; Brownson, Baker, Housemann, Brennan, & Bacak, 2001; Michael, Perdue, Orwoll, Stefanick, & Marshall, 2010; Nagel, Carlson, Bosworth, & Michael, 2008).

Residential density is one of the most common measures of the built environment that has been associated with physical activity (Brownson, Hoehner, Day, Forsyth, & Sallis, 2009). Density is seen to be important because it has direct effects on utilitarian physical activity, the data is readily available and it can also be a proxy for other variables such as income (Brownson et al., 2009;Forsyth, Oakes, Schmitz, & Hearst, 2007). High residential density sites are believed to increase walking for transport as the congestion of people and traffic make it more convenient to walk or take the bus than drive (Forsyth et al., 2007; Frank & Pivo, 1994). Previous research has shown that more walkable neighborhood environments are associated with greater residential density, mixed land use and greater street connectivity (Gauvin et al., 2005). Studies have found that physical activity is increased by a variety of accessible destinations, neighborhood esthetics, access to public and private recreational facilities, neighborhood infrastructure and higher residential density (Berke et al., 2007; Brownson et al., 2009;Gauvin et al., 2005; Nagel et al., 2008). Higher residential density may increase older adult’s physical activity if they have amenities and facilities located at an accessible walking distance from their home. Previous research on residential density and travel patterns have concluded that residents of higher density areas use public transportation or walk more frequently than residents of lower density areas and that higher density areas have a lower rate of automobile ownership (Steiner, 1994).

Considering residential density as an important factor in promotion of walking and physical activity in older adults, neighborhoods in each metropolitan area were selected based on their density levels. Photovoice method was used as part of a larger study (Chaudhury et al., in press) to qualitatively identify key issues related to the role of the physical environment and social capital in influencing seniors’ physical activity as perceived by older adult residents of the selected neighborhoods. Photovoice was developed by Wang and Burris (1997) and is described as “a process by which people can identify, represent, and enhance their community through a specific photographic technique (pg. 369).” This participatory method has emerged as a potential tool for collecting and disseminating knowledge in a way that enables local people to get involved in identifying and assessing the strengths and concerns in their community, create dialog, share knowledge and develop a presentation of their lived experiences and priorities (Hergenrather, Rhodes, & Bardhoshi, 2009). Photovoice method is consistent with core community based participatory research principles with an emphasis “on individual and community strengths, co-learning, capacity building and balancing research and action” (Catalani & Minkler, 2010, p. 425).

Method

In order to identify neighborhood social and physical environmental aspects influential on physical activity of older adults, eight residential neighborhoods (four from each metro area) were chosen as study sites based on population density and income levels. Four density and income categories were created: higher density/higher income; higher density/lower income; lower density/higher income and lower density/lower income (Table 1). Census tracts were used as a basis to select neighborhoods with at least 1000 older adults (65+) in order to have an adequate number of older adults for a survey planned for the subsequent year of this project as part of a larger study. The census tract borders were kept flexible in order to obtain enough participants for this photovoice portion of the study. Density and income chosen as proxy measures were guided by previous research (Berke et al., 2007; Brownson et al., 2009; Forsyth et al., 2007; Steiner, 1994) and the availability of census data for the two measures. Data on the physical and social environments were reported through the eyes of the older adults living in the neighborhoods by allowing them to take their own pictures through photovoice method.

Table 1.

Vancouver, BC and Portland, OR area neighborhoods by density and income.

| Portland | Vancouver | |

|---|---|---|

| Higher density/higher income (HD/HI) | Mt. Tabor (16 participants) | Vancouver (7 participants) |

| Higher density/lower income (HD/LI) | Clackamas (1 participant) | Burnaby (5 participants) |

| Lower density/higher income (LD/HI) | Lake Oswego (9 participants) | Surrey (13 participants) |

| Lower density/lower income (LD/LI) | Milwaukie (6 participants) | Maple Ridge (9 participants) |

Density (households per hectare):

Portland Region: high 19.37; low 10.53.

Vancouver Region: high 81.3; low 10.2.

Median household income:

Vancouver Region: high: $67,236; low: $30,379.

Portland Region: high: $61,935; low: $30,892.

Thirty-four older adults in four neighborhoods in Metro Vancouver, British Columbia and 32 older adults in four neighborhoods in Metro Portland, Oregon participated in the photovoice method. The recruitment of study participants was done using multiple strategies. Primary recruitment was done at local community centers by posting flyers, as well as talking with older adult groups at those centers. Other strategies included contacting churches, community planning tables, advertisements in community newspapers and word-of-mouth. To be eligible for the study the person needed to be: 65 years of age or over, living in community-based housing, be able to communicate and understand basic English, be functionally mobile and comfortable walking in neighborhood with or without assistive devices, be able to self-report physical and social activity, have no hindrances that would impede the ability to operate a camera, be willing to attend a one half-day training session and one half-day discussion session.

All participants attended one training/information session before the data collection. A catered half-day training/information session was held in each metro area. A brief questionnaire on self-reported health and physical activity levels was administered. During this initial session, the participatory nature of the photovoice method was emphasized. The training identified three important reasons the method was selected for this project each related to the importance of engaging community members in the research: (a) the method values the knowledge put forth by people as a vital source of expertise; (b) what professionals, researchers, specialists, and outsiders think is important may completely fail to match what the community thinks is important, and (c) the photovoice process turns the camera lens toward the eyes and experiences of people that may not be heard otherwise. In the second part of the session, a professional photographer instructed the study participants on effective photo-taking techniques and allowed them time to practice with a disposable camera.

For the actual photovoice activity, the participants were asked to photograph physical and social aspects of their respective neighborhoods that they perceived as facilitators or barriers to their physical activity behaviors. For the purpose of this study, “physical activity” was defined as to any physical movement or mobility carried out for the purpose of leisure (e.g., walk in the park, dance class, workout at gym) or transportation (e.g., walking/cycling to a destination) in the participant’s neighborhood. Although physical activity also includes activities of daily living (ADLs) in the home, the current definition in this study was based on its focus on activities taking place in the neighborhood environment. A participant package was handed out that included: a 27-exposure disposable camera, a photo-journal to document where each picture was taken and the reason behind taking the picture, general information on the study and photography tips, picture taking consent forms, a postage-paid envelope and instructions. Participants had 2 weeks to take the pictures and were asked to mail the camera back to the research team when finished. The photographs were developed by the research team and a set of prints was mailed back to the participants with additional instructions. Each participant was asked to select 6–8 photographs from her/his respective set that best reflected the issues he/she was trying to capture and write additional comments or impressions about those selected pictures.

The participants attended a second half-day catered group discussion session in each metro area. In the first part of this session, the researchers randomly distributed the participants into multiple small groups, with each group having 4–5 participants. Each participant then discussed her/his 6–8 selected pictures within the small group with a facilitator (researcher/research assistant) who took notes and summarized the group’s findings. In the second half of the session, highlights from the multiple small group discussions were shared with the whole group (32 participants in Portland and 34 participants in Vancouver) and a facilitated discussion was recorded. These sessions were meant to foster critical discussion and reflection regarding issues identified in the photographs, emerging issues and to generate planning and design recommendations on how to overcome the barriers and enhance facilitators of physical activity in the study neighborhoods. Each participant who completed the study up to this point was given a stipend of $100 as honorarium for her/his time and travel expenses to attend the two face-to-face sessions (training and discussion) as required by the study process.

All photographs, photo journals and additional write-ups were then collected, organized and coded by two researchers in each region. The researchers started with a framework of concepts identified from the literature using a deductive analytic strategy called “Successive approximation” (Neuman, 2006). “Successive approximation” is a method of qualitative data analysis in which the researcher repeatedly moves back and forth between the empirical data and abstract concepts or theories (Neuman, p. 469). The concepts, i.e., safety, accessibility, etc., have been previously reported as important issues in the literature on physical environment for walkability. In this study, the concepts are explored and exemplified in a participatory method (photovoice) and potential social aspects of physical activity are identified. We explored areas of congruence and incongruence between the higher density and lower density neighborhoods. Ethics approval for this study was received from Simon Fraser University Office of Research ethics.

Demographics

All participants filled out a questionnaire asking basic questions on their socio-demographics (Table 2). The general socio-demographics included the participants’ sex, age, marital status, level of education and living arrangement. In both regions the majority of the participants were female. In Portland, the age ranged from 65 to 92 years old and 62% were in the older age ranges from 75 to 80+. In Vancouver, the majority of the sample was younger with 61% belonging to the lower age ranges of 65–74. The education level in Portland was high, with 75% reported having completed college, university or some graduate school or more, compared to only 27% in Vancouver’s.

Table 2.

Socio-Economic Status (SES) demographics of participants.

| General SES demographics | Portland (n = 32) | Vancouver (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 37% (12) | 26% (9) |

| Female | 62% (20) | 73% (25) |

| Age | ||

| Age range | 65–92 | 65–87 |

| 65–69 | 25% (8) | 32% (11) |

| 70–74 | 12% (4) | 29% (10) |

| 75–79 | 28% (9) | 15% (5) |

| 80+ | 34% (11) | 12% (4) |

| Not stated | 12% (4) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single (never married) | 0% (0) | 3% (1) |

| Married/common law | 44% (14) | 47% (16) |

| Separated/divorced | 31% (10) | 12% (4) |

| Widowed | 25% (8) | 38% (13) |

| Education | ||

| Not stated | 3% (1) | 3% (1) |

| Grade school (up to grade 8) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| High school (up to grade 12) | 9% (3) | 29% (10) |

| Technical training certificate | 3% (1) | 9% (3) |

| Some college or university | 9% (3) | 32% (11) |

| Completed college or university | 28% (9) | 15% (5) |

| Some graduate school or more | 47% (15) | 12% (4) |

| Living arrangement | ||

| On own | 53% (17) | 41% (14) |

| With spouse/partner | 34% (11) | 44% (15) |

| With other family | 6% (2) | 9% (3) |

| With other non-family | 0% (0) | 3% (1) |

| Not stated | 6% (2) | 3% (1) |

Findings

Data were analyzed to identify any differences between the neighborhoods grouped as higher versus lower density, as well as differences across the two metro areas. Four themes emerged based on thematic analysis of the participants’ photographs, group discussions and the descriptions of each photograph by the participants. These themes –Safety and Security, Accessibility, Comfort of Movement and Peer Support – are presented with representative photographs and quotes.

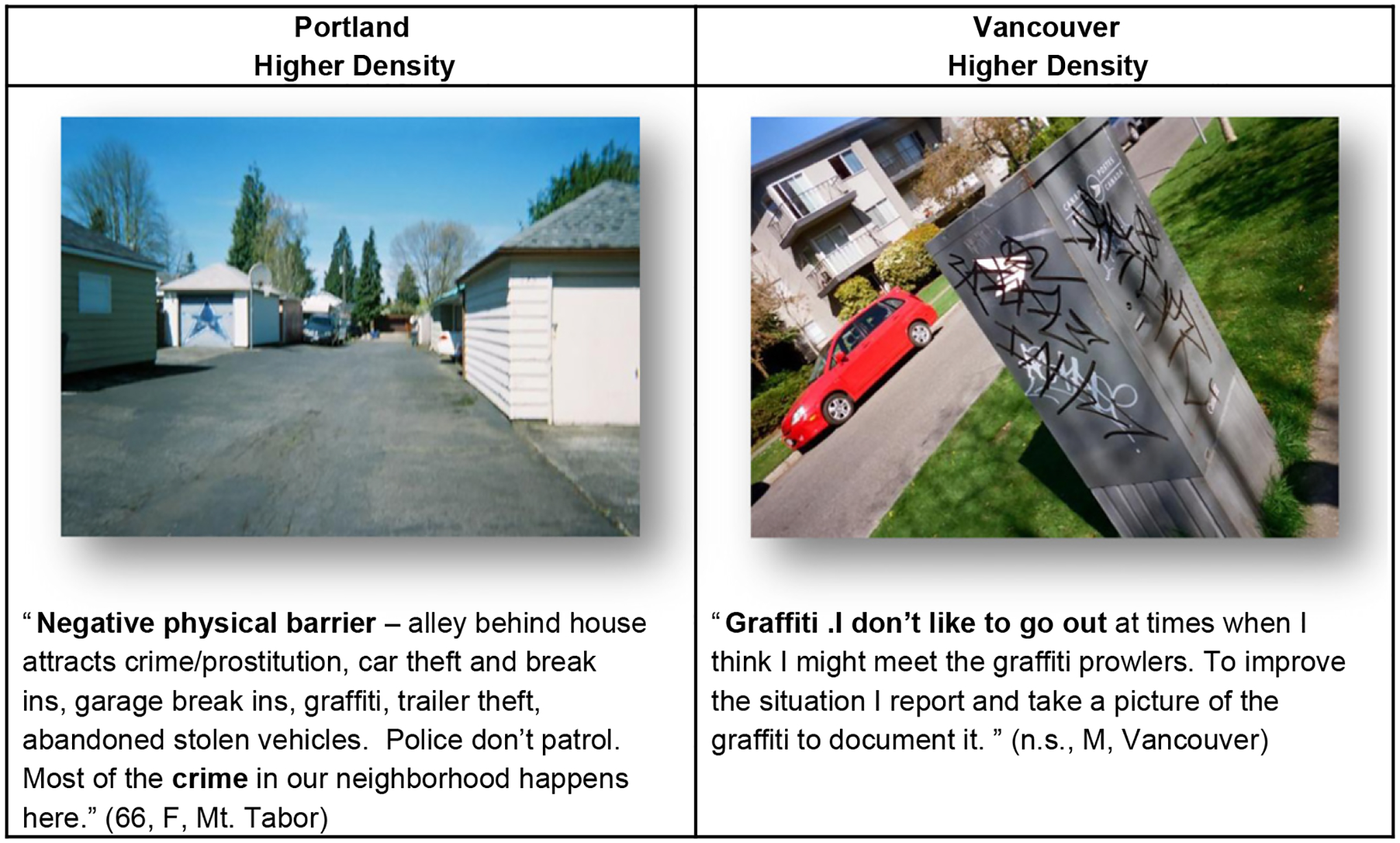

Safety and security

The theme “safety and security” encompasses issues that affected the participants’ sense of feeling physically safe and psychologically secure in their neighborhoods (Fig. 1). This theme was composed of three subthemes: a) maintenance and upkeep of the physical environment, b) traffic hazards, and c) the neighborhood atmosphere. In the sub-theme of maintenance and upkeep of the physical environment, no noticeable differences between the various neighborhoods were found. The most common physical environment barrier was uneven sidewalks or any obstacles or barriers that were tripping hazards and made it unsafe to walk. Absence of sidewalks, ending or narrow sidewalks were commonly mentioned as barriers to walking. Physical environment facilitators for walking included paved, flat, smooth and wide walking surfaces with good lighting and accessible seating.

Fig. 1.

Safety and security — neighborhood atmosphere.

In regard to traffic concerns, more negative issues were reported in the higher density neighborhoods compared to the lower density neighborhoods in both regions. Issues such as busy streets with high traffic volume and speed, unsafe intersections and crosswalks, dangerous and impatient drivers with little respect for the rules of the road, and poor visibility were common. Higher density areas often have heavy traffic congestion and smaller streets, causing busy streets and potentially impatient drivers. People living in higher density areas have also been reported to use public transportation or walk more frequently (Steiner, 1994), which would increase the pedestrian traffic and create more congestion around sidewalks, crosswalks and intersections. This may cause dangerous or unsafe conditions, or the perception of the environment being unsafe for pedestrians.

In terms of personal safety and neighborhood atmosphere, more negative aspects were mentioned in the higher density neighborhoods in both cities. Issues such as feeling unsafe, crime, graffiti and vandalism were mentioned in the higher density neighborhoods. However, specific to Vancouver’s lower density neighborhood (mostly the South Surrey area) many participants mentioned that teenagers would often hangout at the beach at night causing safety concerns in the neighborhood and creating an unsafe atmosphere at night. For the older adults, this may be a perception of feeling unsafe as youth hanging out in groups may be seen as intimidating or dangerous. In any event, the presence of teenagers at night is a deterrent for going outside for an after dinner walk for those older adults. This latter issue raises the potential (real or perceived) conflict in use of public spaces by different age groups. The diversity of uses by older adults and other age groups (e.g., teenagers, families with children) need to be further explored in order to have a fuller and more meaningful understanding.

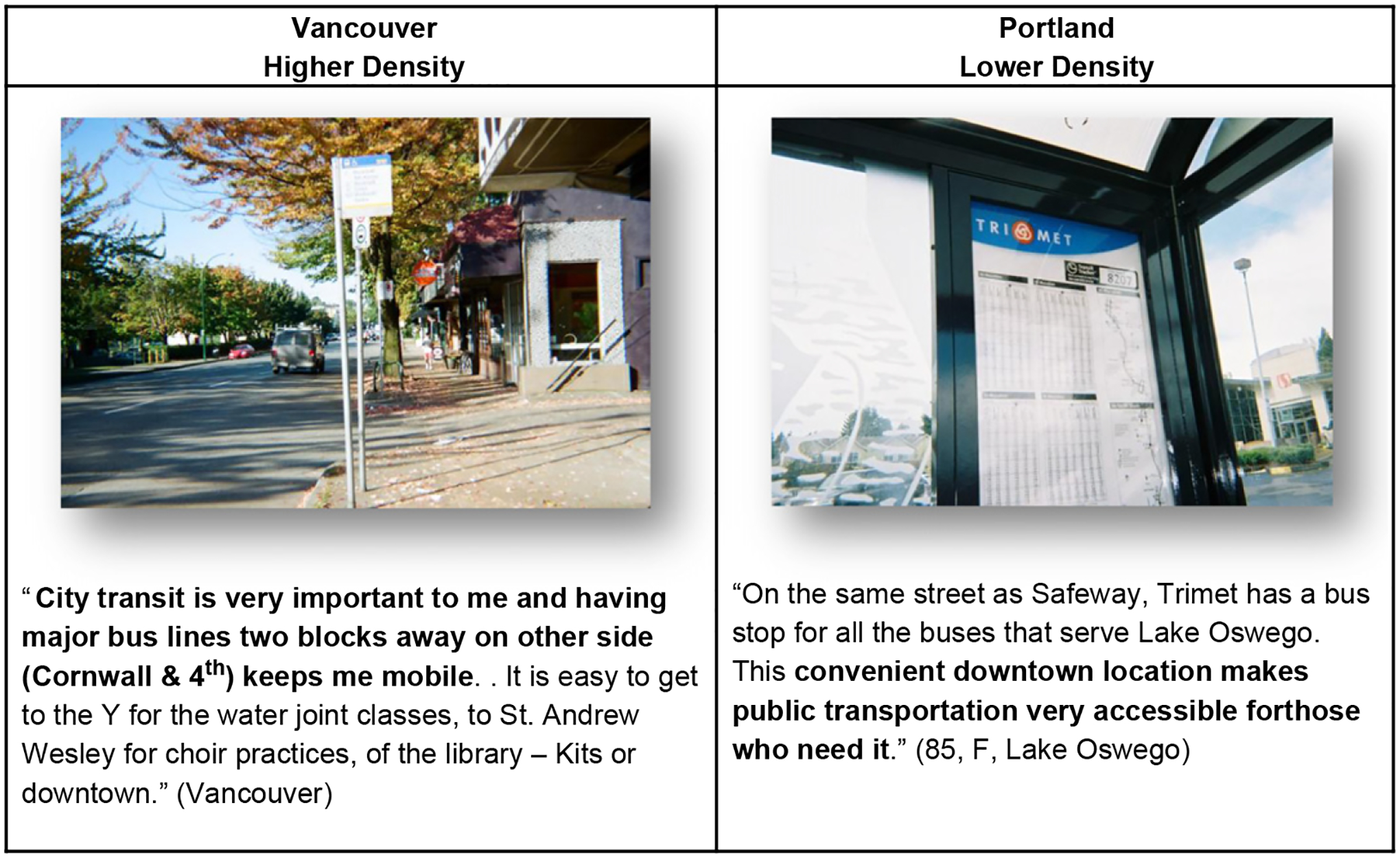

Accessibility

Not surprisingly, issues of accessibility and barriers in getting to neighborhood amenities were identified as contributing factors in their levels of mobility and activity. Two issues emerged as facilitators to physical activity: a) access of public transportation, and b) access to neighborhood facilities or services (Fig. 2). Although public transportation issues were mentioned by many participants in all the neighborhoods, a few differences arose among the neighborhoods. Participants living in the higher density neighborhoods reported a more positive outlook on the public transportation system. In those neighborhoods, the majority of participants who mentioned public transportation reported that the bus system is to be an accessible and convenient service in their community. As an interesting variation on this topic, participants in Portland’s lower density neighborhoods documented the availability of community buses through the community centers or retirement homes. The only barrier mentioned was poor access to the local parks, which posed as a barrier to utilizing the city’s parks. In Vancouver’s lower density neighborhoods, poor transportation was a common theme, reporting a lack of adequate scheduling and service. Limited public transportation access to recreational places such as parks or mall complexes was seen as a detrimental to physical activity, as visiting those destinations required the use of a car. Participants from all neighborhoods — regardless of differing density, mentioned the importance of accessible amenities. Amenities such as the bank, grocery store, post-office, mall, library, gym or recreation center were often mentioned as important amenities to have close to home. These amenities had a utilitarian purpose as well as a recreational or social component.

Fig. 2.

Accessibility of public transportation.

The importance of “accessibility” in this theme underscores two issues. First, in planning for providing community-based amenities and services, it is equally critical to consider how might older adults get to these amenities/services. It is one thing to develop an adult day program or a seniors’ wellness program in the neighborhood; however, it is another matter to carefully examine if older adults with varying mobility challenges can easily and safely get to these destinations. The mechanism of transportation on foot, public transit or other shared options are critical in terms of sustained participation and use of programs and services that might be available in the neighborhood. Second, the value of informal social interaction associated with a physical activity is a conceptually rich and practically promising avenue. This raises the possibility that older adults might be more likely to participate in and maintain physical activity behavior when there is a meaningful social aspect to it. The latter could include a range of sociological dimensions including emotional support, motivation, information support, social interaction, friendship, sense of belonging, etc.

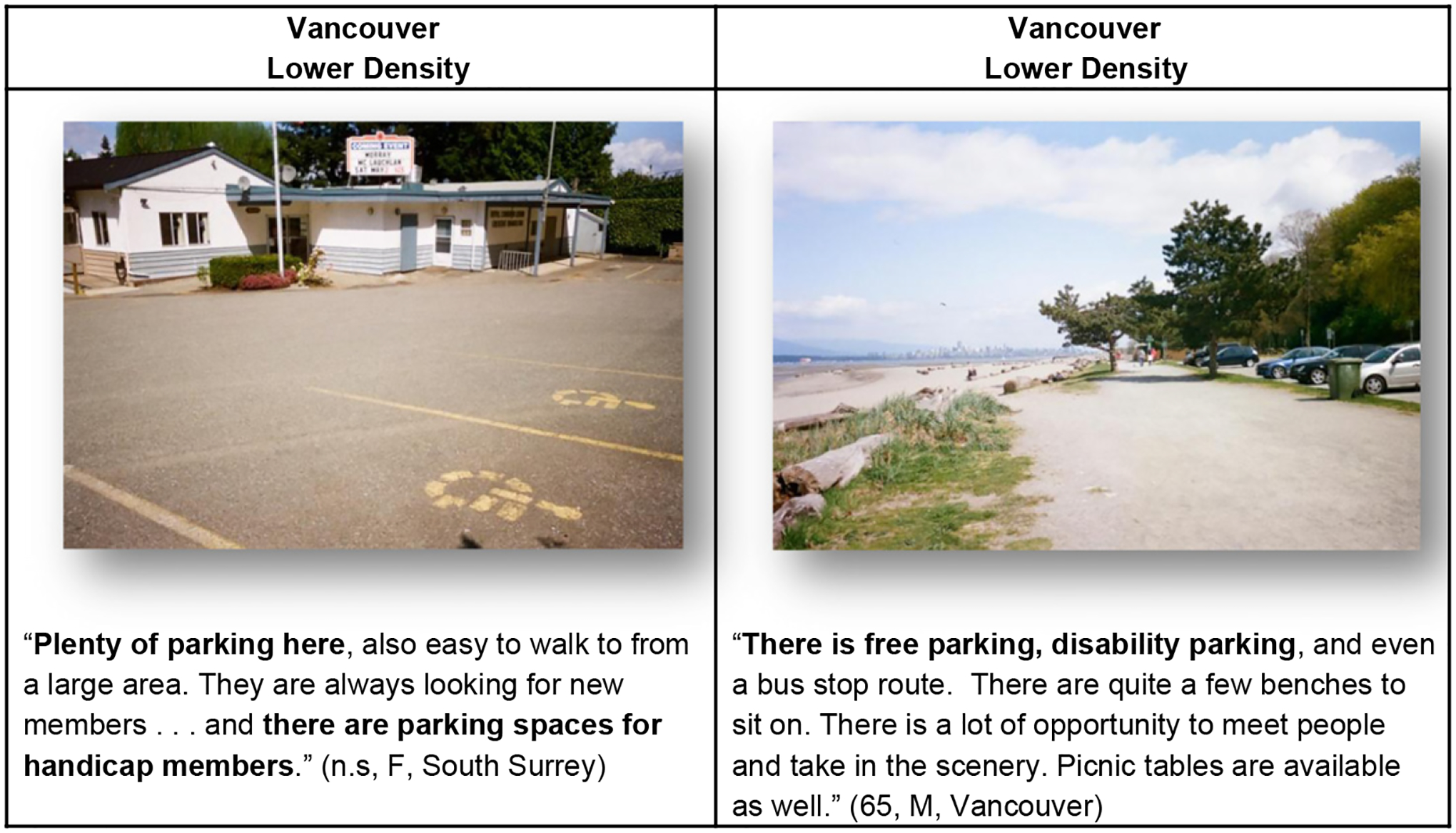

Comfort of movement

The theme “comfort of movement” encompasses physical environmental features which assist or cause difficulty for people in navigating their environment as described and photographed by the participants (Fig. 3). The majority of the comfort of movement features mentioned was common throughout all the neighborhoods. Features that were seen by all neighborhood participants as facilitators to physical activity was available seating, railings, handrails, ramps, safe stairs, and water fountains. Vancouver’s lower density neighborhoods also included the importance of automated doors on buildings and the presence of clean washrooms in public areas as features that helped with movement. Additionally, in both Vancouver’s lower and higher density neighborhoods, the use of cars and the availability and cost of parking were included in the participants’ descriptions —a factor that was rarely discussed in Portland. This may be due to the uniqueness of each city. Portland is generally recognized for its good transportation system and city bike routes which contribute to its being a more transit oriented city than Vancouver. Participants in Vancouver neighborhoods had to rely more on automobiles to get to facilities, grocery stores and recreational destinations, especially in the lower density neighborhoods. Portland’s participants did not often mention personal automobiles which may reflect the city’s culture or the specific participants who participated in the study.

Fig. 3.

Comfort of movement — cars and parking.

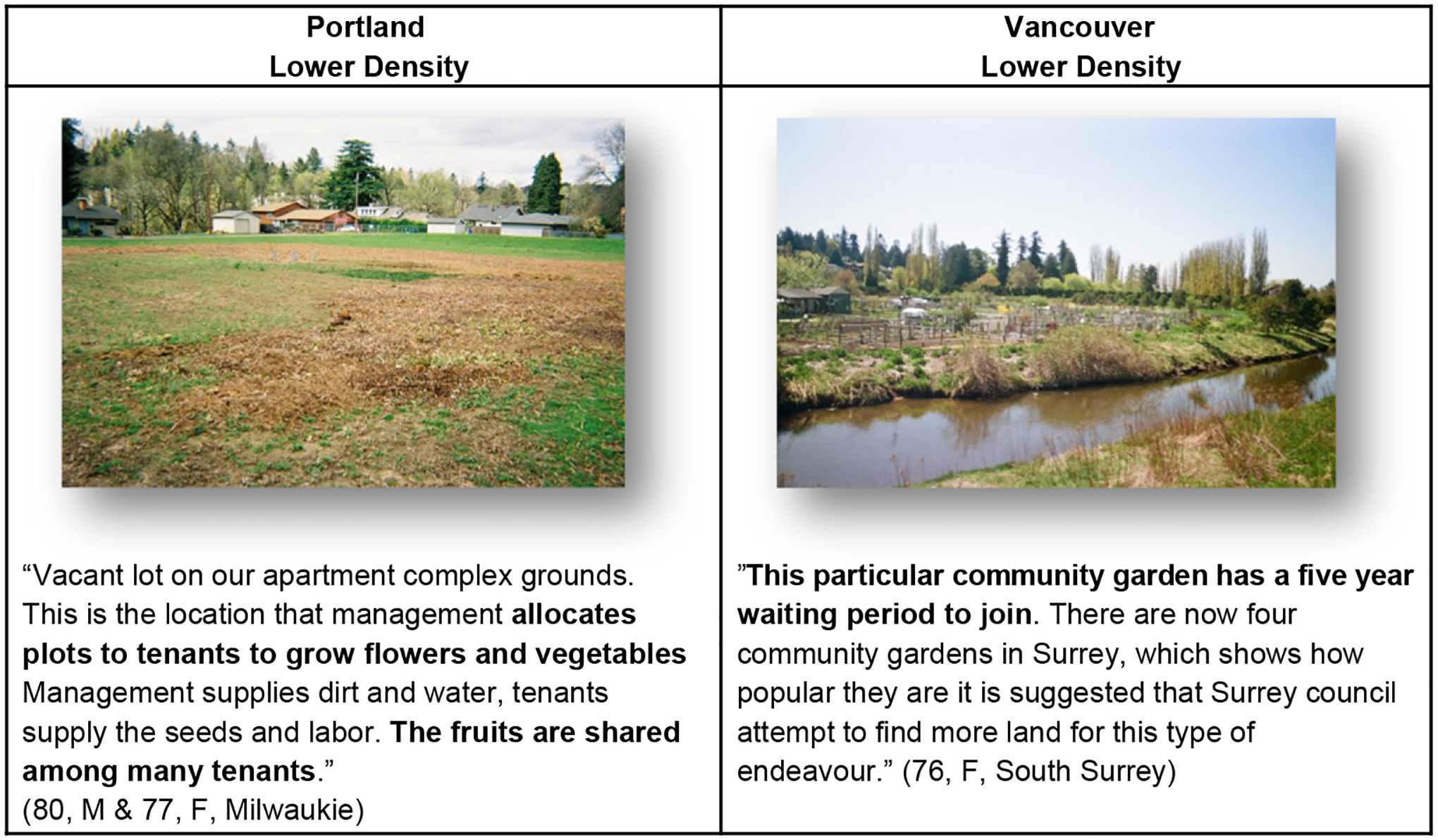

Peer support

Peer support and socialization described by the participants came in many forms. Peer support was provided with formal and informal ways within the community and facilitated physical and social activities. Gardening was also a strong facilitator for physical activity and peer support. Formal social supports were characterized by planned activities such as walking groups or lunch groups and included all the community-based programs outlined in the previous theme. This was the case in all neighborhoods; however in Vancouver’s lower density and Portland’s higher density neighborhoods, more formal support groups were identified. The participants in these neighborhoods outlined more formal groups such as bird walking groups, heart and stroke club, formal walking groups and formal monthly meetings to socialize or play music (Fig. 4). Vancouver’s lower density neighborhoods were noted for their large multicultural community events, this finding may reflect the work being done in these communities by the residents and community leaders.

Fig. 4.

Peer support — gardening.

In terms of informal social support, all participants mentioned socialization and peer support after or during physical activity, whether it be working out and socializing with a friend at the gym or exercise class or post-exercising socialization. Many participants expressed walking with family or friends for physical activity or walking to a meeting spot to have coffee and socialize. Participants also referenced meeting and socializing with community members or neighbors while on a walk, at the shops or stopping to chat with people passing by. Within informal support, there were no differences seen between neighborhood density levels. Participants in all neighborhoods mentioned gardening; however it was most significant in the city of Portland, especially in the higher density neighborhoods. In Portland, many of the gardening photographs and descriptions were of community gardening plots where the land was shared among the members of the community. While attending to plants and vegetables served as the primary source of physical activity, many of the participants enjoyed the social aspect of this activity where a social gardening community was formed. In some instances, spaces for socialization (i.e. benches, picnic tables) were available in the garden area. In Portland, gardening was seen to be a significant facilitator to their physical and social activities. In Vancouver, a few gardening plots were mentioned, as well as maintenance of private yards such as mowing the lawn or gardening as a form of exercise. In Vancouver’s low density neighborhood, it was also mentioned that there is often long waiting periods of garden space which can act as a barrier to gardening in their area.

Discussion and conclusion

Several themes were common throughout all eight neighborhoods in both metro areas regardless of the density levels. Barriers and facilitators of the physical environment such as uneven sidewalks or smooth flat walking spaces were important in all neighborhoods. A variety of accessible facilities and destinations were identified as positive features for maintenance and increase in physical activity. Participants also identified positive environmental aspects for their comfort of movement, such as benches or ramps, which assisted their movement. Lastly, easy access to community centers and community groups was seen as a significant issue fostering physical and social activities. These common findings correspond with the previous research concerning the physical environment and older adult physical activity (Berke et al., 2007; Brownson et al., 2009; Gauvin et al., 2005; Michael, Green, & Farquhar, 2006). Overall, the themes of safety and security, accessibility, comfort of movement, and peer support complement the physical environmental and social aspects of the neighborhood experience related to mobility and physical activity. The first three themes are more oriented toward the physical environmental features, whereas the last one is based on primarily social context of the physical activity behavior. We believe that the interdependence of these two dimensions, as exemplified in the participants’ photos and descriptions, point out the need that they be simultaneously considered for any physical activity program or environmental interventions.

Analyzing the findings by region and neighborhood density allowed for more specific themes to be identified based on location and density. Traffic and neighborhood atmosphere were found to affect the older adult physical activity negatively in the higher density neighborhoods. It has been proposed that higher residential density increases traffic congestion and that at a certain threshold it will become more convenient to walk or take the bus (Forsyth et al., 2007). For the majority, public transportation was regarded as accessible and convenient, except for the lower density neighborhoods of Vancouver. Previous studies looking at the relationship between residential density and transportation have suggested that residents in higher density areas use public transportation or walk more frequently than residents in lower density areas where there is often a higher automobile ownership (Steiner, 1994). This study found a difference in automobiles between regions as Vancouver had significantly more references in needing a car, parking areas and driving to destinations.

The lower density neighborhoods reported the park or beach to be common destinations compared to the higher density neighborhoods. Gardening was more significant in the city of Portland, especially in the higher density neighborhoods; however it was mentioned in Vancouver as an amenity that would be more widely used if they were more available. Portland’s higher density neighborhoods also reported a strong intergenerational and volunteering component that was found to be significant to their physical and social activity. In Vancouver, it was the lower density neighborhood that reported intergenerational and multicultural activities to be important for the physical and social activity, perhaps due to the multicultural make-up of the neighborhood or the neighborhood event policies.

Physical and social environmental issues related to density and locations highlighted in this study are relevant for policy makers and city planners to recognize in supporting mobility and physical activity in older adults. Findings such as higher density neighborhoods having more negative traffic issues could be beneficial for policy makers and city planners to recognize, and implement traffic calming strategies such as flashing crosswalks to make it safer to walk in the streets and increase physical activity.

Comparing differences between the two regions also brought up several interesting differences that are helpful for future research directions. Common findings in both regions, regardless of density, such as accessible facilities, may be universal for considering the environmental needs of older adults. Understanding the universal needs that encourage and assist older adults to engage in physical activity in their neighborhood is beneficial for city planners and decision makers. Differences observed across Vancouver and Portland areas may be affected by many factors, such as the city’s policies, programs, design, maintenance, transportation system, general priorities and budget.

This study adds to the growing body of literature examining the role of neighborhood physical and social environments on the physical activity of older adults. Older adults are particularly at risk for functional decline and inactivity. Often, physical activity is accomplished as a part of daily life, such as walking for travel or recreation which usually occurs within one’s neighborhood. The physical and social environments are an important factor in older adults’ physical activity levels. Understanding aspects related to neighborhood density levels that could facilitate or impede physical activity can help make more informed policy, planning and design decisions. Findings from this study provide perspectives of older adults themselves in identifying neighborhood physical and social environmental characteristics that have perceived or real influences on health promoting behaviors. The issue of residential density has emerged as a more complex reality than how it is typically perceived and conceptualized. Although increased density provides greater opportunity for accessible services and amenities and in general, likely to allow more walkable neighborhood, the potential negative aspects need to be carefully considered. Potential conflicts of space usage by different age groups, perceived lack of sense of security and high traffic volume are some of the challenging social aspects of higher density neighborhoods that should be examined and planned for to maximize the effectiveness of higher density neighborhoods.

Limitations of this study include the non-random sample and the inability to correlate the findings with data on older adult’s actual physical activity. However, the participants included individuals with variability in individual- and neighborhood-characteristics. The findings from the two cities suggest that the barriers and facilitators were real and important and there are variations based on residential density of the neighborhoods. Data were collected in eight neighborhoods in two cities in the Pacific Northwest, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results. Nevertheless, studies such as this one are essential as a first step in designing interventions for understudied groups, including older adults.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

References

- Acree LS, Longfors J, Fjeldstad AS, Fjeldstad C, Schank B, Nickel KJ, et al. (2006). Physical activity is related to quality of life in older adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Bauman A, Leslie E, & Owen N (2001). Perceived environmental aesthetics and convenience and company are associated with walking for exercise among Australian adults. Preventive Medicine, 33, 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke E, Koepsell T, Moudon AV, Hoskins RE, & Larson EB (2007). Association of the built environment with physical activity and obesity in older persons. American Journal of Public Health, 97(3), 486–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal JA, & Gullette ECD (2002). Exercise interventions and aging: Psychological and physical health benefits in older adults. In Schaie KW, Leventhal H, & Willis SL (Eds.), Effective health behavior in older adults (pp. 157–177). New York: Springer Series Societal Impact on Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Baker EA, Housemann RA, Brennan LK, & Bacak SJ (2001). Environmental and policy determinants of physical activity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(12), 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Hoehner CM, Day K, Forsyth A, & Sallis JF (2009). Measuring the built environment for physical activity: State of the science. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 26(4S), S99–S123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, & Minkler M (2010). Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior, 37, 424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervero R, & Radisch C (1996). Travel choices in pedestrian versus automobiles orientated neighborhoods. Transport Policy, 3(3), 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury H, Sarte A, Michael YL, Mahmood A, McGregor EM, & Wister A (in press). Use of a systematic observational measure to assess and compare walkability for older adults in Vancouver, British Columbia and Portland, Oregon neighborhoods. Journal of Urban Design. [Google Scholar]

- Colman R, & Walker S (2004). The cost of physical inactivity in British Columbia. Victoria, BC: GPI Atlantic. [Google Scholar]

- Division of Aging and Seniors (2001). Healthy aging: Physical activity and older adults. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson NG, & Gilron AR (2009). From partnership to policy: The evolution of active living by design in Portland, Oregon. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(6), S436–S444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth A, Oakes M, Schmitz KH, & Hearst M (2007). Does residential density increase walking and other physical activity? Urban Studies, 44 (4), 679–697. [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, & Pivo G (1994). Impacts of mixed use and density on utilization of three modes of travel: Single-occupant vehicle, transit, and walking. Transportation Research Record, 1466, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvin L, Richard L, Craig LC, Spivock M, Riva M, Forster M, et al. (2005). From walkability to active living potential: An “ecometric” validation study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(2S2), 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, & Donovan RJ (2002). The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 1793–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B, & Donovan RJ (2003). Relative influences of individual, social, environmental, and physical environmental correlates of walking. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1583–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, & Balfour JL (2003). Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. In Kawachi I, & Berkman LF (Eds.), Neighborhoods and health (pp. 303–334). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hergenrather CK, Rhodes DS, & Bardhoshi G (2009). Photovoice as a community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(6), 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Newsom JT, McFarland BH, & Lindsay J (2003). Prevalence and correlates of overweight and obesity among older adults: Findings from the Canadian national population health survey. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 58A(11), 1018–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Fisher JK, Bauman A, Ory MG, Chodzko-Zajko W, Harmer P, et al. (2005). Neighborhood influences on physical activity in middle-aged and older adults: A multilevel perspective. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 13(1), 87–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockett D, Willis A, & Edwards N (2005). Through seniors’ eyes: An exploratory qualitative study to identify environmental barriers to and facilitators of walking. Journal of Nursing Research, 37(3), 48–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael YL, Perdue LA, Orwoll ES, Stefanick ML, & Marshall LM (2010). Physical activity resources and changes in walking in a cohort of older men. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael YL, Green MK, & Farquhar SA (2006). Neighborhood design and active aging. Health & Place, 12, 734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel C, Carlson NE, Bosworth M, & Michael YL (2008). The relationship between neighborhood built environment and walking among older adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 168, 461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman WL (2006). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (Sixth edition). Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Seefeldt V, Malina RM, & Clark MA (2002). Factors affecting levels of physical activity in adults. The Journal of Sports Medicine, 32(3), 143–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada (2006). Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle 3.1: Public Use Microdata File (Catalogue no. 82M0013XCB). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner RL (1994). Residential density and travel patterns: Review of literature. Transportation Research Record, 1466, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AH, Cable NT, Faulkner G, Hillsdon M, Narici M, & Van Der Bij AK (2004). Physical activity and older adults: A review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. The Journal of Sports Medicine, 22(8), 703–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troped PJ, Saunders RP, Pate RR, Reininger B, Ureda JR, & Thompson SJ (2001). Associations between self-reported and objective physical environmental factors and use of a community rail-trail. Preventive Medicine, 32, 191–200 (2 (Print)). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, the American Association of Retired Persons, the Federal Council on the Aging & the U.S Administration on Aging (1998. Edition). Aging America; Trends and Projections. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, & Burris MA (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24, 369–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SM, Wójcicki TR, & McAuley E (2009). Physical activity and quality of life in community dwelling older adults. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wister AV (2005). Baby boomer health dynamics: How are we aging? Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]