Abstract

Five spontaneous nitrofurantoin-resistant mutants (one each of Clostridium leptum, Clostridium paraputrificum, two other Clostridium spp. strains from the human intestinal microflora, and Clostridium perfringens ATCC 3626) were selected by growth on a nitrofurantoin-containing medium. All of the Clostridium wild-type and mutant strains produced nitroreductase, as was shown by the conversion of 4-nitrobenzoic acid to 4-aminobenzoic acid. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of the mutants during incubation with 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml showed the gradual disappearance of the nitrofurantoin peak. The nitrofurantoin peak also disappeared when cell-free supernatants instead of cultures of each of the resistant and wild-type bacteria were used, but it persisted if the cell-free supernatants had been inactivated by heat. At least two of the mutants converted nitrofurantoin to metabolites without antibacterial activity, as was shown by a bioassay with a nitrofurantoin-susceptible Bacillus sp. strain. Nitrofurantoin at a high concentration (50 μg/ml) continued to exert some toxicity, even on the resistant strains, as was evident from the longer lag phases. This study indicates that Clostridium strains can develop resistance to nitrofurantoin while retaining the ability to produce nitroreductase; the mutants metabolized nitrofurantoin to compounds without antibacterial activity.

Nitrofurantoin, 1-[(5-nitrofurfurylidene)amino]hydantoin, is a synthetic antibacterial agent which is effective against most common gram-negative and gram-positive urinary tract pathogenic bacteria (6). Although most of an ingested dose of nitrofurantoin is absorbed in the small intestine, 6 to 13% of this drug reaches the colon (27). Bacteria resistant to nitrofurantoin have been found in the feces of both adults and children (3, 4, 13, 28), and nitrofurantoin has been associated with increased risk of community-acquired, antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile diarrhea (10).

Nitro drugs are reduced by mammalian and microbial nitroreductases to free-radical metabolites with bactericidal activities (1, 15–17, 19, 22). Although reduction of nitrofurantoin has been shown to occur in the ceca and colons of rats (2), the specifics of the metabolism of this drug by bacteria from the human intestinal microflora are not known.

Bacteria from the human intestinal tract, especially Clostridium species, are involved in the activation and detoxification in vivo of ingested compounds, including nitro compounds, by metabolizing them to products which are either more toxic or less toxic than the parent compounds (23, 25). Drugs can affect metabolic activities and the enzymatic potential of the gut microflora (7, 25). Therefore, exposure of intestinal bacteria to antibiotics will affect metabolic activities, with potentially important consequences for health (25), as can be extrapolated from the impact of antibiotic treatments in experimental animals. There are differences between animals treated with antibiotics and untreated animals regarding reabsorption and excretion of mutagenic environmental pollutants (18), binding of environmental contaminants to macromolecules (29), and enzymes associated with liver tumors induced by mutagenic compounds (12).

Five nitroreductase-producing strains of Clostridium, a predominant genus of colonic bacteria (7), were grown in the presence of nitrofurantoin to evaluate its effects on anaerobic bacteria from the human intestinal tract. Nitrofurantoin-resistant mutants of the strains were isolated, and their growth characteristics and nitroreductase activities were examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and reagents.

Clostridium perfringens ATCC 3626 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.). Clostridium paraputrificum NR1, Clostridium sp. strain NR8, Clostridium sp. strain NR9, and Clostridium leptum NP15 were isolated from human intestinal microflora (23). Bacillus sp. strain PS was isolated from potato salad.

Cultures of anaerobes were maintained in prereduced, anaerobically sterilized (PRAS) meat broth (Carr-Scarborough Microbiological, Inc., Decatur, Ga.). Brain-heart infusion (BHI-PRAS) broth was from Carr-Scarborough. BHI broth and BHI agar, used for the growth of anaerobes, and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, used for the aerobic growth of Bacillus sp. strain PS, were prepared from ingredients obtained from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). Nitrofurantoin was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). All other chemicals were obtained from either Sigma or Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, Wis.).

Isolation of mutants resistant to nitrofurantoin.

MIC of nitrofurantoin was measured for different bacteria by a tube dilution method with 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, or 10 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml of the BHI medium. Nitrofurantoin (10 μg/ml), to which all of the bacteria were susceptible, was used to select the resistant mutants. Resistant colonies of each strain, which were produced spontaneously on BHI plates or broth containing 10 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml, were transferred to BHI-PRAS broth, also containing 10 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml, and incubated overnight at 37°C. The cultures were then transferred to BHI broth containing 25 or 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml and incubated at 37°C overnight. Resistant mutants were grown in BHI broth containing 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml.

Growth of resistant bacteria with various concentrations of nitrofurantoin.

Resistant strains were grown for 20 h in BHI broth in the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml. The next day, 200 μl of each of the cultures was added to 5 ml of BHI-PRAS broth without nitrofurantoin or with 10, 20, or 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml. The samples were harvested at various intervals. Growth was evaluated by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm (A600) with a model E1 312E (Biotech Instruments, Winooski, Vt.) spectrophotometer.

HPLC analysis of the fate of nitrofurantoin incubated with bacteria.

A single colony of each mutant was used to inoculate BHI-PRAS broth anaerobically. The cultures were then incubated overnight at 37°C. Nitrofurantoin (50 μg/ml) was added anaerobically to each culture; samples removed at 0, 1, 3, 7, and 24 h were centrifuged and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Noninoculated BHI-PRAS medium containing nitrofurantoin was incubated at 37°C as a control.

The HPLC system consisted of a model 600E pump and gradient controller and a model 996 photodiode array detector monitored at 200 to 400 nm (both from Waters Corp., Milford, Mass.), a model 7125 injector with a 20-μl loop (Rheodyne, Cotati, Calif.), and a Prodigy (5-μm particle size, octadecyl silane-3, 4.6 by 250 mm) column (Phenomenex, Torrance, Calif.). HPLC data were acquired and processed with Millennium 2010 Chromatography Manager software (version 2.1; Waters Corp.). Initially, 100% mobile phase I (95% H2O plus 5% acetonitrile, containing 2 g of ammonium acetate per liter) was maintained for 2 min after injection. The mobile phase was then changed over 30 min to 100% mobile phase II (20% H2O plus 80% acetonitrile, containing 2 g of ammonium acetate per liter) and was maintained for 5 min. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. Each HPLC analysis included a standard nitrofurantoin sample as a reference.

Assay of bacterial supernatants for metabolism of nitrofurantoin.

Resistant strains were grown in the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml of BHI broth at 37°C; wild-type strains were grown under the same conditions without nitrofurantoin. The cultures were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were filtered through a degassed Acrodisc filter (HT Tuffryn membrane, 0.2-μm pore size; Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, Mich.). The filtered supernatants were added to each of five sterile, degassed tubes. Two of the cultures were heated for 5 min in a boiling water bath. To one boiled culture and one control culture, 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml was added and incubated for 20 h. The rest of the cultures were incubated at 37°C without further treatment. For zero time incubation, nitrofurantoin (50 μg/ml) was added to one of the boiled cultures and to one control culture. One culture was left untreated. All samples were analyzed by HPLC as described above.

Bioassay for antibacterial activity of nitrofurantoin metabolites after incubation with bacteria.

To assay for the antibacterial activities of nitrofurantoin residues after incubation with the mutants, the rate of growth of a nitrofurantoin-sensitive Bacillus sp., strain PS, was monitored. The supernatants from wild-type and mutant Clostridium sp. strains, incubated overnight without nitrofurantoin and with 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml, respectively, were used. The growth rates of Bacillus sp. strain PS in the presence and absence of nitrofurantoin and culture supernatants were compared. Bacillus sp. strain PS, which did not grow in media containing 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml, was grown overnight on LB agar. The bacterial cells were suspended in sterile distilled water (2 × 107 cells per ml). Fifty microliters of this suspension was added to 1 ml of BHI-PRAS broth, either with or without 50 μg of nitrofurantoin, and also to filter-sterilized supernatants from either cultures of the wild-type (grown without nitrofurantoin) or nitrofurantoin-resistant Clostridium spp. strains that had been grown overnight with or without 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml. Samples (0.1 ml each) were harvested at 3, 5, 7, and 24 h, and serial dilutions were plated on LB agar for colony counting after incubation at 37°C overnight.

Assay of nitroreductase activity.

The nitroreductase activities in the cultures of resistant and parent strains were measured under anaerobic conditions in a glove box with anaerobic gas (85% N2–10% H2–5% CO2). Each of the wild-type and nitrofurantoin-resistant strains was incubated at 37°C overnight in BHI medium in the absence or the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml, respectively. 4-Nitrobenzoic acid (final concentration, 500 μg/ml) was added anaerobically to each of the cultures. The cultures were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 30 min, and the conversion of 4-nitrobenzoic acid to 4-aminobenzoic acid was assayed as previously described (23). The amount of 4-aminobenzoic acid produced was measured by the A540. The cell density was measured by the A600.

The nitroreductase activities in the supernatants of overnight cultures of resistant and wild-type strains, grown in the presence or absence of nitrofurantoin, respectively, were also examined. Cells from overnight cultures were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were added to empty tubes that had been degassed with anaerobic gas. 4-Nitrobenzoic acid was added to the tubes which were incubated at 37°C for 1 h as described previously. Samples were centrifuged and then assayed for the presence of 4-aminobenzoic acid (23, 30). The amount of 4-aminobenzoic acid produced was calculated from the A540, and protein was measured by the method of Lowry et al. (14). The units of nitroreductase activity (the amount of enzyme necessary to produce 1 μg of 4-aminobenzoic acid in 1 h at 37°C) were calculated for the cell density (A600) in the bacterial cultures and for the protein in the bacterial supernatants (14).

RESULTS

Susceptibilities of different strains of Clostridium species to nitrofurantoin.

The MICs of nitrofurantoin for the different Clostridium species were as follows: ≤6 μg/ml (C. perfringens ATCC 3626), ≤8 μg/ml (C. paraputrificum NR1), ≤5 μg/ml (Clostridium sp. strain NR8), ≤4 μg/ml (Clostridium sp. strain NR9), and ≤2 μg/ml (C. leptum NP15). Resistant bacterial colonies developed at a frequency of 10−5 to 10−7 for the different species on agar plates containing 10 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml. These colonies subsequently developed resistance to higher concentrations of nitrofurantoin in BHI medium.

Effect of nitrofurantoin on the growth of resistant bacteria.

The Clostridium spp. strains that grew for two subsequent passages in the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml were considered resistant to nitrofurantoin. One mutant from each wild type was selected. The resistant bacteria were designated C. perfringens 3626NF, C. paraputrificum NR1NF, Clostridium sp. strain NR8NF, Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF, and C. leptum NP15NF.

The growth rates of resistant bacteria varied at different concentrations of nitrofurantoin. Figure 1 is representative of the growth of three resistant strains in the presence of different concentrations of nitrofurantoin. All three strains had longer lag phases in the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml. C. perfringens 3626NF (Fig. 1A) and C. paraputrificum NR1NF (Fig. 1B) also had lower cell densities in the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml than in the absence of this drug (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Effect of the concentration of nitrofurantoin on the growth of resistant strains of Clostridium species. (A) C. perfringens 3626NF; (B) C. paraputrificum NR1NF; (C) Clostridium sp. strain NR8NF. ○, no drug; •, 10 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml; □, 20 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml; ▪, 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml.

Metabolism of nitrofurantoin by resistant bacteria.

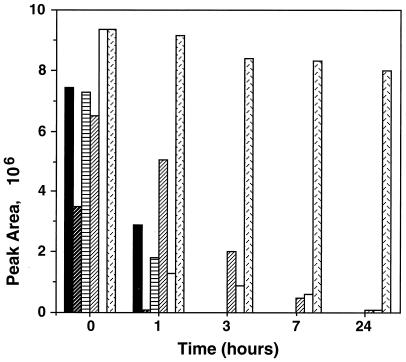

HPLC was used to monitor the metabolism of nitrofurantoin by the resistant strains. The concentration of nitrofurantoin, before and after incubation with medium, bacterial culture, or bacterial supernatant, was monitored at three different wavelengths corresponding to the UVλmax values of the nitrofurantoin. The results for 376 nm are presented in the figures because they show the highest sensitivities for nitrofurantoin. In the samples taken at zero time from the BHI medium and the bacterial cultures to which nitrofurantoin had been added and from the BHI medium incubated for 24 h with nitrofurantoin at 37°C, the nitrofurantoin peak eluted from the HPLC column at the time corresponding to the standard nitrofurantoin peak (Fig. 2A). After incubation of nitrofurantoin with the bacterial cultures, all five of the resistant mutants metabolized nitrofurantoin. Fig. 2B shows the HPLC profile after the overnight incubation of Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF in BHI-PRAS broth with 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml; it is representative of chromatographic profiles observed after incubation of nitrofurantoin with the other resistant strains. In each case, the peak corresponding to the nitrofurantoin peak decreased with time and finally disappeared or nearly disappeared during incubation (Fig. 3). However, no metabolites produced from nitrofurantoin could be definitely recognized from the chromatographic data.

FIG. 2.

HPLC elution profiles of cultures of a nitrofurantoin-resistant mutant, Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF, in BHI medium containing nitrofurantoin. (A) Culture inoculated with the mutant and sampled at zero time. (B) Culture inoculated with the mutant after incubation. (The elution profile of the noninoculated medium with nitrofurantoin after incubation for 24 h and that of nitrofurantoin after incubation with a heat-treated culture supernatant were both similar to that shown in panel A; the profile of the nitrofurantoin after incubation with an active culture supernatant was similar to that shown in panel B.)

FIG. 3.

Areas of the nitrofurantoin peaks in HPLC profile after anaerobic incubation with overnight cultures of Clostridium sp. mutants or noninoculated BHI medium. ▪, C. paraputrificum NR1NF; , C. perfringens 3626NF; ▤, Clostridium sp. strain NR8NF; ▨, C. leptum NP15NF; □, Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF; ▩, BHI medium.

When nitrofurantoin was incubated with cell-free supernatants from overnight cultures of the wild-type and mutant strains, the nitrofurantoin peak also disappeared and the HPLC pattern was similar to that for nitrofurantoin incubated with the bacterial cultures (Fig. 2B). Boiling the supernatants before addition of nitrofurantoin, however, prevented the disappearance of the nitrofurantoin peak so that the HPLC profile was similar to that for incubation of nitrofurantoin with noninoculated media (Fig. 2A).

Bactericidal activity of residual nitrofurantoin after incubation with nitrofurantoin-resistant mutants.

To assay for the antibacterial activities of nitrofurantoin residues after incubation with the mutants, the rate of growth of a nitrofurantoin-sensitive Bacillus sp., strain PS, was monitored. In the presence of 50 μg of nitrofurantoin per ml of BHI broth, the number of Bacillus sp. strain PS cells after 24 h had decreased from 1.45 × 106 to 1.10 × 106 per ml (Fig. 4A), indicating the inhibition of the growth of this bacterium in the presence of nitrofurantoin. In contrast, in the absence of nitrofurantoin, the number of Bacillus sp. strain PS cells increased 64-fold from 1.84 × 106 to 1.18 × 108 per ml (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

(A) Number of surviving cells of a nitrofurantoin-sensitive bacterium (Bacillus sp. strain PS) before and after incubation with either BHI broth or cultures of nitrofurantoin-resistant strains of Clostridium species (grown with or without nitrofurantoin). ▪, BHI broth; □, BHI and nitrofurantoin; •, C. paraputrificum NR1; ○, C. paraputrificum NR1NF with nitrofurantoin; ✚, Clostridium sp. strain NR9; ×, Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF grown with nitrofurantoin. (B) Number of surviving cells of a nitrofurantoin-sensitive bacterium (Bacillus sp. strain PS) before and after incubation with either BHI broth or cultures of nitrofurantoin-resistant strains of Clostridium species (grown with or without nitrofurantoin). ▴, BHI broth; ▵, BHI and nitrofurantoin; ▪, C. perfringens ATCC 3626; □, C. perfringens 3626NF with nitrofurantoin; ✚, C. leptum NP15; ×, C. leptum NP15NF grown with nitrofurantoin; ○, Clostridium sp. strain NR8; •, Clostridium sp. strain NR8NF. The incubation of Bacillus sp. strain PS with the supernatants of nitrofurantoin-resistant bacteria in the absence of nitrofurantoin produced results identical to those obtained for parental strains (data not shown).

When grown in the presence of the supernatants from resistant strains (with or without nitrofurantoin) or the parental strains of C. paraputrificum NR1 and Clostridium sp. NR9, the number of Bacillus sp. strain PS cells also increased (77-fold for C. paraputrificum NR1, 82-fold for resistant C. paraputrificum NR1NF with nitrofurantoin, 61-fold for Clostridium sp. strain NR9, 61.6-fold for Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF without nitrofurantoin, and 73-fold for resistant Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF with nitrofurantoin). These results indicate that C. paraputrificum NR1NF and Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF converted nitrofurantoin to compounds that did not inhibit the growth of Bacillus sp. strain PS (Fig. 4A). The results were inconclusive for Clostridium sp. strain NR8NF, C. perfringens 3626NF, and C. leptum NP15NF with nitrofurantoin, because the parent strains (Clostridium sp. strain NR8, C. perfringens ATCC 3626, and C. leptum NP15) inhibited the Bacillus sp. strain PS even when no nitrofurantoin had been added to the medium (Fig. 4B). There were no differences between the supernatants from parental strains and resistant strains which were not incubated with nitrofurantoin regarding support for the growth of Bacillus sp. strain PS. Since the results for both were similar, only the data from the parental strains are shown in Fig. 4 in addition to the data from the resistant strains with nitrofurantoin.

Nitroreductase activity of resistant and sensitive strains.

The nitroreductase activities in the supernatants of overnight cultures of resistant strains (incubated with nitrofurantoin) and wild-type strains (without nitrofurantoin) were shown by measuring the conversion of 4-nitrobenzoic acid to 4-aminobenzoic acid under anaerobic conditions. All 10 strains had nitroreductase activity after overnight incubation (Table 1). 4-Aminobenzoic acid was produced during incubation of 4-nitrobenzoic acid with all of the wild-type and mutant bacteria, whether or not they had previously been grown in the presence of nitrofurantoin. All of the mutants showed higher nitroreductase activities than did the corresponding parental strains (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Nitroreductase activity in cultures and cell-free supernatants of parental strains and nitrofurantoin-resistant mutants of Clostridium spp.

| Strain | Nitroreductase activity

fora:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells

|

Soluble protein

|

|||

| Parental strain | Resistant strain | Parental strain | Resistant strain | |

| Clostridium perfringens ATCC 3626 | 89.5 | 102.6 | 6.8 | 10.4 |

| Clostridium paraputrificum NR1 | 39.8 | 135.4 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Clostridium sp. strain NR8 | 74.7 | 102.3 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| Clostridium sp. strain NR9 | 156.1 | 227.0 | 3.3 | 3.9 |

| Clostridium leptum NP15 | ND | ND | 5.4 | 21.8 |

Results are expressed as units of activity where a unit is the amount of enzyme that produces 1 μg of 4-aminobenzoic acid per h from 4-nitrobenzoic acid at 37°C: for cells, units of activity per cell absorbance (A600); for protein, units of activity per milligram of soluble protein. ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Antibiotic treatment has been associated with impaired fermentative activities (7), altered metabolic processes in the colon (7), and diarrhea (10). Bacteria resistant to various antibiotics, including nitrofurantoin, have been isolated from human fecal samples (3, 4), and there is concern for the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes to pathogenic bacteria through the cascade of resistance transfer between related species (8, 24).

In this study, we have shown that nitroreductase-producing Clostridium species from human intestinal microflora were able to develop resistance to nitrofurantoin. Although nitrofurantoin-resistant mutants of several other genera of bacteria have been either developed in the laboratory or isolated from human fecal samples with a frequency of 1 to 2.3% (for Escherichia coli) (3, 4, 13, 21, 28), this is the first study in which nitrofurantoin resistance has been reported in nitroreductase-producing Clostridium sp. strains.

Nitrofurantoin was almost completely metabolized by the cells, the culture supernatants from all of the resistant mutants, and the supernatants from the parental strains, as shown by HPLC. The enzymes involved in this metabolic process were extracellular and heat labile. As in the study of Moreno et al. (19) with rat liver mitochondria, the metabolites produced during incubation of nitrofurantoin with the bacteria were presumably unstable and were not detected. Both C. paraputrificum NR1NF and Clostridium sp. strain NR9NF deactivated this drug, as was evident from the lack of antimicrobial activity of the supernatants against the nitrofurantoin-susceptible Bacillus sp. strain PS. This result indicates that the end products of nitrofurantoin metabolism by these strains no longer have any antimicrobial activity. It has been suggested that the end products of nitrofurantoin reduction by bacteria are biologically inactive (1, 15); we previously have shown that the direct-acting mutagenicity of 1-nitropyrene, 1,3-dinitropyrene, and 1,6-dinitropyrene is inactivated by incubation with these bacteria (23).

The antibacterial activity of drugs containing nitro groups has been attributed to the conversion of these compounds by nitroreductases to toxic but unstable intermediates (1, 15–17, 22). In this study, we detected nitroreductase activity in all of the Clostridium spp. strains, including both nitrofurantoin-sensitive and -resistant strains. Carlier et al. (5) observed differences between the reduction pathways of 5-nitroimidazole in susceptible and resistant strains of Bacteroides fragilis. Whereas in the susceptible strains nitroso radicals are formed, in the resistant strains amine derivatives are formed, preventing the formation of toxic forms of the drug (5). We previously have shown by activity staining that only one nitroreductase isozyme is present in four of these bacteria and that they are able to produce amine derivatives from nitropyrenes and 4-nitrobenzoic acid (23).

In addition to the toxic, unstable intermediates produced from nitrofurantoin by nitroreductase, mechanisms proposed to explain the toxicity of nitrofurantoin include the formation of intrastrand cross-links in DNA and the inhibition of protein synthesis (9, 16, 17, 19–22, 26). McOsker and Fitzpatrick (16) reported that nitrofurantoin has multiple sites of attack and multiple mechanisms of action, inhibiting protein synthesis by nonspecific reactions with both ribosomal protein and rRNA. They mentioned that nitrofurantoin has antibacterial activity against E. coli even in the absence of nitroreductase (16).

Higher concentrations of nitrofurantoin (50 μg/ml) increased the lag phase of nitrofurantoin-resistant Clostridium spp. and decreased the growth rates of one of the strains. This result is similar to results obtained by Hoffman et al. (11), who observed that both the lag phase and maximum growth rate of a resistant strain of Helicobacter pylori were inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by metronidazole (11).

In summary, we have obtained five nitrofurantoin-resistant mutants of Clostridium strains and shown that development of nitroreductase resistance in these strains was not due to a loss in nitroreductase activity. The nitrofurantoin was metabolized by a heat-labile extracellular fraction. At least two of the Clostridium strains converted nitrofurantoin to compounds that permitted the growth of nitrofurantoin-susceptible bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pamala Lunsford for her technical assistance and John B. Sutherland, Jon G. Wilkes, Carl E. Cerniglia, and Bruce D. Erickson for helpful comments regarding preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asnin R E. The reduction of furacin by cell free extracts of furacin resistant and parent susceptible strains of E. coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1957;66:208–216. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(57)90551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aufrere M B, Hoener B A, Vore M. Reductive metabolism of nitrofurantoin in the rat. Drug Metab Dispos. 1978;6:403–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beunders, A. J. 1994. Development of antibacterial resistance: the Dutch experience. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33(Suppl. A):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Calva J J, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Ceron C. Antimicrobial resistance in fecal flora. Longitudinal community-based surveillance of children from urban Mexico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1699–1702. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlier J P, Sellier N, Rager M N, Reysset G. Metabolism of 5-nitroimidazole in susceptible and resistant isogenic strains of Bacteroides fragilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1495–1499. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain R E. Chemotherapeutic properties of prominent nitrofurans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1976;2:325–336. doi: 10.1093/jac/2.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway P. Microbial ecology of the human large intestine. In: Gibson G R, Macfarlane G T, editors. Human colonic bacteria: role in nutrition, physiology and pathology. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies J. Another look at antibiotic resistance. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1553–1559. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-8-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrlich P, Schweiger M. Nitrofurans, a group of synthetic antibiotics with a new mode of action: discrimination of specific messenger RNA classes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3386–3390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschhorn L R, Trnka Y, Onderdonk A, Lee M L T, Platt R. Epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:127–133. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman P S, Goodwin A, Johnsen J, Magee K, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S J O. Metabolic activities of metronidazole-sensitive and -resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori: repression of pyruvate oxidoreductase and expression of isocitrate lyase activity correlate with resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4822–4829. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4822-4829.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehman-McKeeman L D, Johnson D R, Caudill D. Induction and inhibition of mouse cytochrome P-450 2B enzymes by musk xylene. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;142:169–177. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.7927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.London N, Nijsten R, Van der Bogaard A, Stobberigh E. Carriage of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coliby healthy volunteers during a 15-week period. Infect Immun. 1994;22:187–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01716700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCalla D R. Biological effects of nitrofurans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1977;3:517–520. doi: 10.1093/jac/3.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McOsker C C, Fitzpatrick P M. Nitrofurantoin: mechanism of action and implications for resistance development in common uropathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:23–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.suppl_a.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McOsker C C, Pollack J R, Anderson J A. Inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis by nitrofurantoin macrocrystals: an explanation for the continued efficacy of nitrofurantoin. R Soc Med Int Congr Symp Ser. 1989;154:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medinsky M A, Shelton H, Bond J A, McClellan R O. Biliary excretion and enterohepatic circulation of 1-nitropyrene metabolites in Fischer-344 rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34:2325–2330. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno S N, Mason R P, Docampo R. Reduction of nifurtimox and nitrofurantoin to free radical metabolites by rat liver mitochondria. Evidence of an outer membrane-located nitroreductase. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6289–6305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mukherjee U, Basak J, Chatterjee S N. DNA damage and cell killing by nitrofurantoin in relation to its carcinogenic potential. Cancer Biochem Biophys. 1990;11:275–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee U, Bhattacharya R, Chatterjee S N. Effect of nitrofurantoin on viability, DNA synthesis and morphology of Vibrio choleraecells. Indian J Exp Biol. 1993;31:808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pavicic M J, van Winkelhoff A J, Pavicic-Temming Y A, de Graaff J. Metronidazole susceptibility factors in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:263–269. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rafii F, Franklin W, Heflich R H, Cerniglia C E. Reduction of nitroaromatic compounds by anaerobic bacteria isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:962–968. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.962-968.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmussen, B. A., K. Bush, and F. P. Tally. 1997. Antimicrobial resistance in anaerobes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24(Suppl. 1):110–120. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Rowland I. Toxicology of the colon: role of the intestinal microflora. In: Gibson G R, Macfarlane G T, editors. Human colonic bacteria: role in nutrition, physiology and pathology. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1995. pp. 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengupta S, Rahman M S, Mukherjee U, Basak J, Pal A K, Chatterjee S N. DNA damage and prophage induction and toxicity of nitrofurantoin in Escherichia coli and Vibrio choleraecells. Mutat Res. 1990;244:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(90)90108-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah R R, Wade G. Reappraisal of the risk/benefit of nitrofurantoin: review of toxicity and efficacy. Adverse Drug React Acute Poisoning Rev. 1989;8:183–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamey T A, Condy M, Mihara G. Prophylactic efficacy of nitrofurantoin macrocrystals and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in urinary infections. Biological effects on the vaginal and rectal flora. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:780–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197704072961403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki J, Meguro S, Morita O, Hirayama S, Suzuki S. Comparison of in vivobinding of aromatic nitro and amino compounds to rat hemoglobin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:3511–3519. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zacharia P K, Juchau M R. The role of gut flora in the reduction of aromatic nitro-groups. Drug Metab Dispos. 1974;2:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]