Abstract

Objectives

To compare palatal dimensions and molar inclinations after Invisalign First System (IFS) to those in patients treated with slow maxillary expansion (SME) and normal controls.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-three mixed dentition patients treated with IFS were gender- and dental age-matched to another two groups: Haas-type SME and control group. The intercanine width (ICW), intermolar width (IMW), palatal surface area (SA), volume (V), and first molar buccolingual inclinations (MI) were measured before (T1) and after (T2) treatment. Analysis of variance was used to compare the differences among the three groups.

Results

The ICW increased significantly by 3.10 mm after IFS, 4.77 mm with SME, and 0.54 mm in controls; the difference among the groups was statistically significant (P < .001). The IMW increased by 1.95 mm in IFS, 4.76 mm in SME, and 0.54 mm in controls, with significant intra- and intergroup differences. Palatal SA and volume increased by 43.50 mm2 and 294.85 mm3 in the IFS group, which differed significantly from SME, but was similar to controls. The right and left MI increased 0.24° and 0.08° buccally, respectively, in the IFS group, which was comparable to controls, while significantly increased buccal MI was observed in the SME group.

Conclusions

IFS expands the upper arch with increased ICW and IMW compared to controls, but the expansion amount is smaller than SME. Unlike SME, IFS has no effects on palatal dimensions and molar inclinations.

Keywords: Invisalign First system, Palatal dimension, Slow maxillary expansion, Molar inclination

INTRODUCTION

With decades of improvements in computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM) and dental materials, the Invisalign system (Align Technology Inc., Tempe, AZ) has been used to treat over 14 million patients worldwide including more complex cases, mainly in adults and teenagers.1–4 Invisalign First system (IFS) was first introduced in 2018, targeting mixed dentition children who needed Phase I treatment. A few case reports published in the early stage showed that the most predictable treatment outcomes could be obtained in Class II malocclusions in which the maxillary molars needed derotation and distalization, malocclusions with a narrow maxilla and/or mandible, and anterior crossbite with a functional shift.5–8 Recent case series also demonstrated that IFS may be effective for interceptive problems in moderate and severe cases.9

Early treatment of dentoalveolar crossbite traditionally involves the application of an expansion appliance, fixed or removable, with a slow or rapid expansion protocol to address the transverse deficiency.10 Although the efficacy and predictability of maxillary arch expansion with Invisalign aligners in permanent dentitions have been explored with no common ground,11–16 a few studies have endeavored to evaluate transverse arch development with IFS in growing subjects and found it to be a reasonable alternative to traditional maxillary expanders.17–19 In contrast to rapid maxillary expansion (RME) in which the initial triangular shape was maintained, Lombardo et al. found that IFS improved maxillary arch shape.19

Changes in palatal area, volume, and molar buccolingual inclination (MI) have been reported extensively with different maxillary expansion methods.20–25 However, there is no previously published study documenting palatal area and volume changes after IFS therapy. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate changes in palatal dimensions and MI after IFS in mixed dentition and compare them with slow maxillary expansion (SME) and untreated normal controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (IRB: H21-03540). Sample size calculation determined that it was necessary to have a minimum of 17 subjects in each group to detect a minimum difference in the palatal volume of 927.55 mm3, with a standard deviation (SD) of 727.80 mm3, at a significance level of 5% and a power of 80%.23

Eighty-six patients, aged 8 to 11 years old, were consecutively treated by a single, highly experienced orthodontist who prescribed all ClinCheck treatment plans between October 2018 and June 2020. Fifty-one were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: mixed dentition malocclusions being treated with IFS, upper first molars fully erupted, nonextraction, and having finished the first series of aligners. Exclusion criteria included: missing bilateral primary canines, use of auxiliary appliances, previous orthodontic treatment, or presence of craniofacial deformities.

The SME and control groups were recruited from a previous study23 in which 30 randomly selected patients were treated with SME. Thirty untreated normal control subjects were from the Oregon Health and Sciences University collection and matched for gender, molar relationship, and dental age using the Demirjian and Goldstein method.26 All three groups were rematched using the same criteria, and 23 patients (11 males and 12 females) from each group were finalized.

In the IFS group, all patients were planned with the same sequential staging expansion protocol, with molars first followed by the simultaneous expansion of deciduous molars and canines. The amount of expansion at each stage was 0.25 mm. SmartForce aligner activations and the optimized expansion-support attachments were built into the aligner without prescribing extra buccal root torque to the first molars. No specific derotation of the upper first molar around its palatal root was programmed. All patients were instructed to change their aligners every week. The mean number of aligners was 28. The duration between the initial (T1) and refinement (T2) was 1.02 ± 0.36 years.

Treatment protocol for the SME group involved a two-banded Haas-type appliance with one quarter-turn every 2 days until the maxillary lingual cusps were in contact with the mandibular buccal cusps, followed by passive retention for a minimum of 6 months. The treatment duration was 0.98 ± 0.51 years. The observation period of the control group was 1.22 ± 0.56 years.

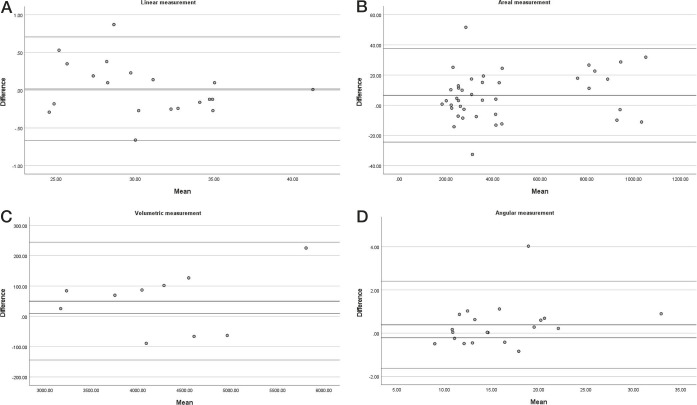

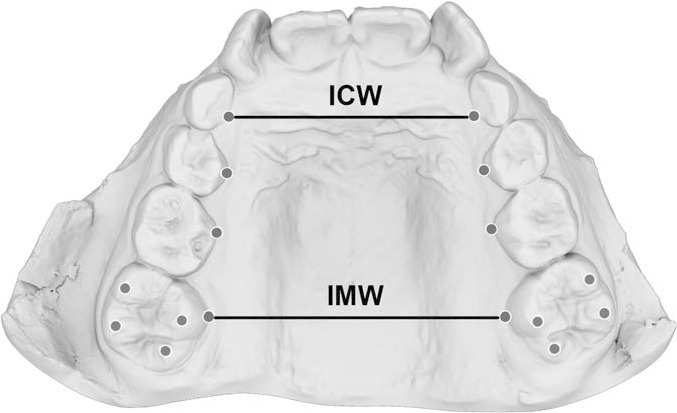

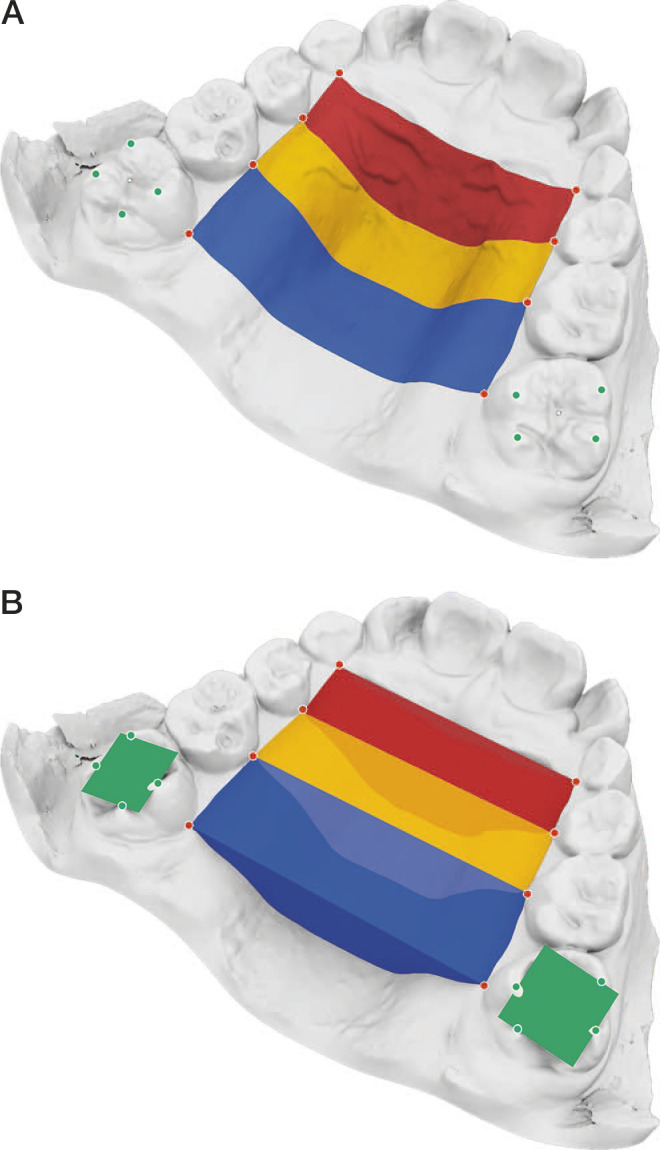

Maxillary stereolithography (STL) models in the IFS group were collected at T1 and T2. For the SME and control groups, all scanned maxillary models were imported and analyzed in Rhinoceros 3D (version 7.0, Robert McNeel & Associates, Seattle, WA). Each model was landmarked as follows: a landmark was placed at the point of greatest concavity along the lingual gingival margin of primary canines, primary first molars, primary second molars, and permanent first molars bilaterally (Figure 1). Linear measurement of intercanine (ICW) and intermolar widths (IMW) are shown in Figure 1. Total palatal surface area (SA) and volume (V) were measured and divided into anterior (ant.), middle (mid.), and posterior (post.) parts (Figure 2). Additional landmarks were placed at the cusp tips of permanent first molars to produce best-fit horizontal planes. The buccolingual inclination of the permanent first molar was determined by measuring the angle between a line normal to the best-fit plane and a line perpendicular to the occlusal plane (the horizontal plane through the points defining the palatal gingival margins of the maxillary teeth) (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Landmark identification and measurements of ICW and IMW. ICW indicates intercanine width; IMW, intermolar width.

Figure 2.

Palatal surface area (A) and volume (B) measurements including anterior (black), middle (light gray), and posterior (dark gray) segments.

Figure 3.

Illustration of molar buccolingual inclination measurement.

The data were analyzed with SPSS (Version 27.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Measurements for 10 models were repeated 1 month apart to assess intra-examiner agreement using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Bland-Altman plots were generated to show the deviations in the measurements. All measurements were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilks test. Descriptive statistics in the form of median and interquartile ranges (IQR, Q3–Q1) were reported when the parameters did not show a normal distribution. Changes between T1 and T2 in each group were analyzed with paired t-test for normal data and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normal data. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to evaluate the differences among groups at T1 and parameter changes for normally distributed and non-normally distributed data, respectively, with a threshold for statistical significance of P < .05.

RESULTS

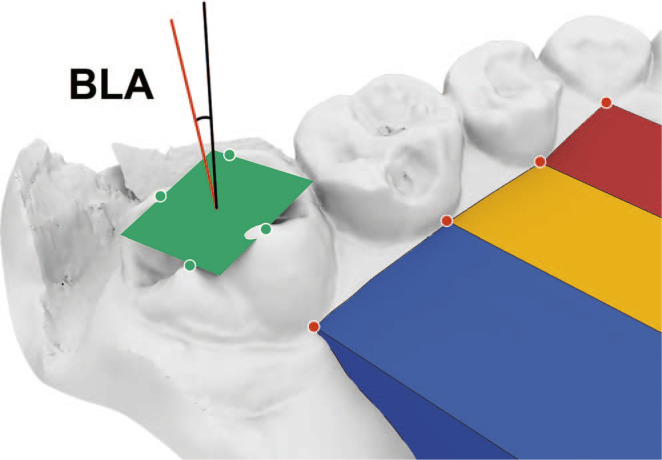

The intra-examiner ICC was 0.974 (95% CI: 0.952 to 0.999), which indicated an excellent level of agreement. The Bland-Altman plots for linear, areal, volumetric, and angular measurements are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Bland-Altman plot of repeated linear (A), areal (B), volumetric (C), and angular (D) measurements.

All parameters were normally distributed except V ant. in the control group at T1 and T2, V mid. in the SME group at T1, both IFS and control groups at T2, V post. in the control group at T1, and total volume (V) in the control group at T1 and T2.

Table 1 shows no statistically significant difference in dental age, treatment duration, palatal volume, and MI at T1 among the three groups. Statistically significant differences were found only in ICW and IMW, with a smaller ICW in the SME group and a larger IMW in the IFS group (P < .05).

Table 1.

Comparison of Dental Age, Treatment Duration and Measurements at T1 Among the Three Groups (n = 23 / Group)f

|

|

IFS Group | SME Group | Control Group |

P |

|

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR)b |

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

Mean ± SD or Media (IQR) |

||

| Dental agea (y) | 8.45 ± 0.67 | 8.34 ± 0.79 | 8.40 ± 0.84 | .889 |

| Duration (y) | 1.02 ± 0.36 | 0.98 ± 0.51 | 1.22 ± 0.56 | .190 |

| ICW (mm) | 25.28 ± 1.65e | 23.03 ± 2.42d | 24.62 ± 2.01e | .001* |

| IMW (mm) | 32.46 ± 2.07d | 30.81 ± 3.03e | 30.92 ± 1.86e | .036* |

| SA ant. (mm2) | 233.36 ± 25.32 | 218.77 ± 40.03 | 237.76 ± 38.12 | .165 |

| SA mid. (mm2) | 243.68 ± 20.48 | 246.70 ± 33.03 | 247.05 ± 29.12 | .974 |

| SA post. (mm2) | 379.12 ± 35.35 | 356.18 ± 44.92 | 362.38 ± 30.68 | .095 |

| SA (mm2) | 856.16 ± 54.79 | 821.65 ± 104.35 | 847.19 ± 66.41 | .305 |

| V ant. (mm3) | 624.76 (192.66) | 596.46 (240.62) | 663.10 (169.78) | .090c |

| V mid. (mm3) | 1077.16 (208.75) | 1056.83 (314.58) | 1118.16 (245.95) | .314c |

| V post. (mm3) | 2106.23 (541.31) | 1697.92 (546.80) | 1910.52 (218.19) | .081c |

| V (mm3) | 3743.39 (720.59) | 3369.98 (1312.13) | 3735.91 (525.57) | .193c |

| MI 16 (°) | 14.40 ± 5.23 | 12.23 ± 5.68 | 13.66 ± 4.51 | .354 |

| MI 26 (°) | 13.19 ± 5.07 | 10.98 ± 4.48 | 13.21 ± 3.38 | .146 |

P < 0.05.

Dental age assessed by Demirjian.26

Mean± SD was reported for normal data and median (IQR) was reported for variables without normality. Analysis of variance tests were performed except indicated as c, which shows the results of Kruskal-Wallis tests.

indicate the post hoc comparison with the subset for alpha = 0.05.

ICW, intercanine width; IFS, Invisalign First system; IMW, intermolar width; MI, molar buccolingual inclination; SA, surface area; SME, slow maxillary expansion; V, volume; MI, molar buccolingual inclination.

Changes in ICW, IMW, Total SA, and V (including different sections), and MI in each group are summarized in Table 2. For the intragroup comparison, all variables except SA post. and MI increased significantly after treatment in the IFS group. In the SME group, all parameters showed various degrees of statistically significant increments. In the control group, ICW, IMW, SA and V in the posterior one-third, and Total SA and V showed significant changes.

Table 2.

Intra- and Intergroup Comparisons of Variable Changes From T1 to T2c

|

Variable |

IFS |

SME |

||||

| T1 | T2 | T2–T1 |

P |

T1 | T2 | |

|

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

||

| ICW (mm) | 25.28 ± 1.65 | 28.38 ± 1.64 | 3.10 ± 1.29 | .000*** | 23.03 ± 2.42 | 27.8 ± 2.23 |

| IMW (mm) | 32.46 ± 2.07 | 34.41 ± 2.42 | 1.95 ± 1.61 | .000*** | 30.81 ± 3.03 | 35.56 ± 3.28 |

| SA ant. 1/3 (mm2) | 233.36 ± 25.32 | 255.98 ± 26.79 | 22.63 ± 26.25 | .000*** | 218.77 ± 40.03 | 262.66 ± 46.84 |

| SA mid. 1/3 (mm2) | 243.68 ± 20.48 | 262.79 ± 20.37 | 19.1 ± 16.04 | .000*** | 246.7 ± 33.03 | 267.67 ± 30.55 |

| SA post. 1/3 (mm2) | 379.12 ± 35.35 | 380.89 ± 42.29 | 1.77 ± 28.23 | .766 | 356.18 ± 44.92 | 408.97 ± 48.28 |

| SA total (mm2) | 856.16 ± 54.79 | 899.66 ± 63.81 | 43.50 ± 39.58 | .000*** | 821.65 ± 104.35 | 939.3 ± 107.08 |

| V ant. 1/3 (mm3) | 624.93 ± 134.24 | 710.25 ± 127.47 | 85.32 ± 121.61 | .004** | 636.06 ± 207.15 | 853.51 ± 252.15 |

| V mid. 1/3 (mm3) | 1077.16 (208.75) | 1172.64 (304.00) | 124.18 ± 90.24 | .000a *** | 1056.83 (314.58) | 1312.47 (322.51) |

| V post. 1/3 (mm3) | 2069.51 ± 308.78 | 2154.87 ± 324.81 | 85.36 ± 179.71 | .026* | 1867.82 ± 423.54 | 2310.87 ± 487.55 |

| V total (mm3)a | 3798.55 ± 477.88 | 4093.4 ± 499.24 | 294.85 ± 290.91 | .000a *** | 3616.13 ± 834.09 | 4487.93 ± 922.31 |

| MI16 (°) | 14.4 ± 5.23 | 14.64 ± 4.64 | 0.24 ± 3.60 | .792 | 12.23 ± 5.68 | 16.37 ± 7.42 |

| MI26 (°) | 13.19 ± 5.07 | 13.27 ± 5.29 | 0.08 ± 1.97 | .506 | 10.98 ± 4.48 | 14.96 ± 5.78 |

P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001.

Wilcoxon-signed rank analysis was used for variables without normal distributions instead of paired t-test.

Kruskal-Wallis test was used for variables without normal distributions instead of ANOVA.

ICW indicates intercanine width; IFS, Invisalign First system; IQR, interquartile range; IMW, inter-molar width; MI, molar buccolingual inclination; SA, surface area; SD, standard deviation; SME, slow maxillary expansion; V, volume; MI, molar buccolingual inclination.

Table 2.

Extended

|

SME |

Control |

IFS vs SME | IFS vs Control | SME vs Control | ||||

| T2–T1 |

P |

T1 | T2 | T2–T1 | ||||

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) |

Mean ± SD |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

| 4.77 ± 0.92 | .000*** | 24.62 ± 2.01 | 25.16 ± 2.10 | 0.54 ± 0.77 | .003** | .000*** | .000*** | .000*** |

| 4.76 ± 1.27 | .000*** | 30.92 ± 1.86 | 31.45 ± 2.06 | 0.54 ± 0.68 | .001** | .000*** | .001** | .000*** |

| 43.89 ± 29.47 | .000*** | 237.76 ± 38.12 | 241.56 ± 37.69 | 3.80 ± 22.33 | .423 | .021* | .045* | .000*** |

| 20.97 ± 19.95 | .000*** | 247.05 ± 29.12 | 250.74 ± 31.59 | 3.69 ± 27.67 | .529 | .955 | .049* | .024* |

| 52.79 ± 26.38 | .000*** | 362.38 ± 30.68 | 375.88 ± 32.29 | 13.5 ± 18.03 | .002** | .000*** | .246 | .000*** |

| 117.64 ± 46.89 | .000*** | 847.19 ± 66.41 | 868.18 ± 77.37 | 20.99 ± 34.15 | .007** | .000*** | .152 | .000*** |

| 217.45 ± 149.41 | .000*** | 663.10 (169.78) | 722.66 (158.23) | 35.72 ± 90.18 | .101a | .003b** | .191b | .000b*** |

| 211.3 ± 128.10 | .000a*** | 1118.16 (245.95) | 1188.31 (246.81) | 39.31 ± 171.65 | .412a | .010b* | .090b | .000b*** |

| 443.05 ± 226.10 | .000*** | 1910.52 (218.19) | 1998.66 (353.04) | 143.34 ± 129.42 | .000a*** | .000b*** | .490b | .000b*** |

| 871.80 ± 385.61 | .000*** | 3735.91 (525.57) | 3947.36 (438.38) | 218.36 ± 257.22 | .001a** | .000*** | .406b | .000b*** |

| 4.15 ± 6.57 | .036* | 13.66 ± 4.51 | 13.30 ± 4.35 | −0.37 ± 4.17 | .677 | .008** | .909 | .025* |

| 3.98 ± 4.83 | .001** | 13.21 ± 3.38 | 12.99 ± 4.14 | −0.22 ± 2.96 | .789 | .000*** | .116 | .001** |

For the intergroup comparison (Table 2), the ICW increased significantly by 3.10 mm after IFS (P < .001), 4.77 mm with SME (P < .001), and 0.54 mm in controls (P < .01); the difference among the three groups was also statistically significant (P < .001). The IMW changes showed the same pattern: increased by 1.95 mm in the IFS (P < .001), 4.76 mm in the SME (P < .001), and 0.54 mm in controls (P < .01), with statistically significant differences among groups. The palatal SA and volume increased by 43.50 mm2 and 294.85 mm3 in IFS, which differed significantly from SME, while similar to controls. The right and left MI increased by 0.24° and 0.08° buccally, respectively, in IFS, which was comparable to controls, while significant buccal crown tipping was observed in the SME group.

DISCUSSION

Clear aligner therapy (CAT) has numerous benefits such as improved esthetics, greater comfort, and ease of oral hygiene. CAT can produce dental expansion at the intercanine, interpremolar, and intermolar levels.27 By evaluating the changes in palatal dimensions and MI, inferences about the effect of CAT on dentoalveolar expansion can be evaluated. Studies investigated the effect of CAT on arch expansion in permanent dentitions;11–16 and a few studies assessed mixed dentition patients.17–19 This pilot study aimed to explore the arch width, palatal dimensions, and MI in IFS and compare them with two matching groups: SME and normal controls.

During the observation period of approximately 1 year, the ICW increased by 3.10 mm in IFS and was significantly different from that of the Haas and control groups, which increased by 4.77 mm and 0.54 mm, respectively. The IMW increased by 1.95 mm in IFS and was also significantly different from that of the SME and control, which increased by 4.76 mm and 0.54 mm, respectively. In the current study, IFS therapy produced a greater increase in ICW and a nearly identical increase in IMW compared to a study by Levrini et al. in which a 2-mm increase in ICW and IMW in 8 months was reported.17 Similar observations of more ICW expansion (2.6 mm) than IMW (1.2 mm) were reported by Lione et al.,18 which were in agreement with the current study results by demonstrating that IFS could effectively develop or expand the maxillary arch in the mixed dentition.

The mean SA in the anterior, middle, and posterior thirds increased by 22.63 mm2, 19.10 mm2, and 1.77 mm2, respectively, after IFS treatment. In the anterior and middle thirds, the increase was significantly greater than that of the control group. Interestingly, the area increase in the middle third in IFS was similar to that of SME, while the IFS group showed no difference from the control group in the posterior third. Instead, the SME had a significant increase posteriorly (52.79 mm2). As the palatal SA is dependent on dental landmarks, the lack of significant change in the posterior SA indicated minimal dentoalveolar expansion at the first molar level with IFS.17 Lione et al. found that the greatest expansion was detected at the level of the first deciduous molars, which was in the middle.18 This could be explained by the essentially distinct features of the appliances. The Haas-expander has bands on the first molars, whereas the terminal permanent first molar is the most flexible part of the aligner in IFS and, therefore, likely had a lower expansion force. This has been observed in adult expansion studies.11,14,15,28

For the regional and total volume changes, there was no difference between IFS and control groups, while the SME group showed a significantly greater increase compared to the other groups. It is worth noting that the indications between IFS and SME are different, with Haas-type expander as a skeletal expansion appliance and IFS as a dentoalveolar expansion option. This not only accounted for the differences in palatal dimensional changes between IFS and SME but also the ICW and IMW discrepancies observed at T1. Patients who underwent SME usually started off with more severe maxillary constriction and needed skeletal expansion. However, a skeletal transverse discrepancy was seldom seen in IFS. To compare IFS with SME and controls in this study, it was not the aim to compare the efficacy of two inequivalent expanders, but rather to assess the amount of expansion that potentially could be achieved with different appliances and assist the clinician in choosing the appropriate appliance.

MI after IFS showed nonsignificant changes even without adding additional buccal root torque as recommended by previous studies.12,13 One unique feature of the IFS, which was part of the G8 innovation, was counteracting buccal crown tipping with SmartForce aligner activations and optimized expansion attachments. In the present study, IFS demonstrated better control in MI. In SME, MI increased significantly, showing that expansion achieved was a combination of buccal molar movement and buccal crown tipping.23 Overexpansion was part of the expansion protocol for SME. Nonetheless, IFS therapy is only indicated for dentoalveolar expansion, with the advantage of coordinating upper and lower arch shapes at an earlier stage.

Lione et al.18 suggested that programmed derotation around the first molar palatal root with arch expansion could improve the Class II molar relationship, regain intra-arch space, and avoid unwanted overexpansion in the molar region. Lombardo et al. also showed significant arch shape modifications in IFS compared with RME with the same strategy.19 In the present study, no derotation was prescribed deliberately for IFS. Also, due to the Haas-type expander design in SME, it was not possible to compare the effects of derotation of the first molar. Molar derotation effects on expansion in IFS might need further exploration.

One limitation of this study was that palatal dimension measurements, such as SA and V, were exclusively dependent on soft tissue and dental landmarks; surface meshes created from these landmarks could only provide an estimation. A more accurate way of measuring skeletal changes would be by using CBCT. This was not possible in the current study due to radiation hygiene concerns. Another limitation was that volumetric changes do not necessarily equate to skeletal expansion, eg, an increase in palatal volume may reflect an increase in the depth of the palatal vault but not the widening of the underlying basal bone. Finally, the retrospective nature of this study with IFS and the other comparison groups collected from different sources at different time points was also a limitation. The treatment method was selected mainly based on the clinicians’ knowledge and experience. A well-designed prospective clinical trial would be ideal to augment the internal validity of future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

IFS produced significant increases in intercanine and intermolar width compared to untreated controls. However, IFS expansion magnitude was less than that in the SME group.

The overall palatal SA and volume changes after IFS treatment showed no significant differences compared to the control group, while the SME group showed a significant increase in palatal dimensions.

Molar inclinations were unchanged after IFS, but the Haas-type expander increased MI significantly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the American Association of Orthodontists Orthodontic Faculty Development Fellowship Award (AAOF OFDFA 2021).

REFERENCES

- 1. Garnett BS, Mahood K, Nguyen M, et al. Cephalometric comparison of adult anterior open bite treatment using clear aligners and fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2019;89:3–9. doi: 10.2319/010418-4.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henick D, Dayan W, Dunford R, Warunek S, Al-Jewair T. Effects of Invisalign (G5) with virtual bite ramps for skeletal deep overbite malocclusion correction in adults. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:164–170. doi: 10.2319/072220-646.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dai FF, Xu TM, Shu G. Comparison of achieved and predicted tooth movement of maxillary first molars and central incisors: first premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2019;89:679–687. doi: 10.2319/090418-646.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cong A, Ruellas ACO, Tai SK, et al. Presurgical orthodontic decompensation with clear aligners. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2022;162:538–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2021.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Favero R, Volpato A, Favero L. Managing early orthodontic treatment with clear aligners. J Clin Orthod. 2018;52:701–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blevins R. Phase I orthodontic treatment using Invisalign First. J Clin Orthod. 2019;53:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Staderini E, Meuli S, Gallenzi P. Orthodontic treatment of class three malocclusion using clear aligners: a case report. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2019;9:360–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Staderini E, Patini R, Meuli S, Camodeca A, Guglielmi F, Gallenzi P. Indication of clear aligners in the early treatment of anterior crossbite: a case series. Dental Press J Orthod. 2020;25:33–43. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.25.4.033-043.oar. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pinho T, Rocha D, Ribeiro S, Monteiro F, Pascoal S, Azevedo R. Interceptive treatment with Invisalign® First in moderate and severe cases: a case series. Children (Basel) 2022;9:1176. doi: 10.3390/children9081176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Algharbi M, Bazargani F, Dimberg L. Do different maxillary expansion appliances influence the outcomes of the treatment? Eur J Orthod. 2018;40:97–106. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjx035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Solano-Mendoza B, Sonnemberg B, Solano-Reina E, Iglesias-Linares A. How effective is the Invisalign system in expansion movement with Ex30′ aligners? Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21:1475–1484. doi: 10.1007/s00784-016-1908-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Houle JP, Piedade L, Todescan R, Jr,, Pinheiro FH. The predictability of transverse changes with Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2017;87:19–24. doi: 10.2319/122115-875.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou N, Guo J. Efficiency of upper arch expansion with the Invisalign system. Angle Orthod. 2020;90:23–30. doi: 10.2319/022719-151.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morales-Burruezo I, Gandia Franco JL, Cobo J, Vela Hernandez A, Bellot Arcid C. Arch expansion with the Invisalign system: efficacy and predictability Plos One 2020. 15 E0242979 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lione R, Paoloni V, Bartolommei L, et al. Maxillary arch development with Invisalign system: analysis of expansion dental movements on digital dental casts. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:433–440. doi: 10.2319/080520-687.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riede U, Wai S, Neururer S, et al. Maxillary expansion or contraction and occlusal contact adjustment: effectiveness of current aligner treatment. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25:4671–4679. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-03780-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levrini L, Carganico A, Abbate L. Maxillary expansion with clear aligners in the mixed dentition: a preliminary study with Invisalign First system. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2021;22:125–128. doi: 10.23804/ejpd.2021.22.02.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lione R, Cretella Lombardo E, Paoloni V, Meuli S, Pavoni C, Cozza P. Upper arch dimensional changes with clear aligners in the early mixed dentition: a prospective study J Orofac Orthop 2021. 9 10.1007/s00056-021-00332-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lombardo CE, Paoloni V, Fanelli S, Pavoni C, Gazzani F, Cozza P. Evaluation of the upper arch morphological changes after two different protocols of expansion in early mixed dentition: rapid maxillary expansion and Invisalign first system. Life (Basel) 2022;12:1323. doi: 10.3390/life12091323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marini I, Bonetti GA, Achilli V, Salemi G. A photogrammetric technique for the analysis of palatal three-dimensional changes during rapid maxillary expansion. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:26–30. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gracco A, Malaguti A, Lombardo L, Mazzoli A, Rafaeli R. Palatal volume following rapid maxillary expansion in mixed dentition. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:153–159. doi: 10.2319/010407-7.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gohl E, Nguyen M, Enciso R. Three-dimensional computed tomography comparison of the maxillary palatal vault between patients with rapid palatal expansion and orthodontically treated controls. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bukhari A, Kennedy D, Hannam A, Aleksejūnienė J, Yen E. Dimensional changes in the palate associated with slow maxillary expansion for early treatment of posterior crossbite. Angle Orthod. 2018;88:390–396. doi: 10.2319/082317-571.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kinzinger GSM, Lisson JA, Buschhoff C, Hourfar J, Korbmacher-Steiner H. Impact of rapid maxillary expansion on palatal morphology at different dentition stages. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26:4715–4725. doi: 10.1007/s00784-022-04434-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Malmvind D, Golez A, Magnuson A, Ovsenik M, Bazargani F. Three-dimensional assessment of palatal area chages after posterior crossbite correction with tooth-borne and tooth bone-borne rapid maxillary expansion. Angle Orthod. 2022;92:589–597. doi: 10.2319/012822-85.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Demirjian A, Goldstein H. New systems for dental maturity based on seven and four teeth. Ann Hum Biol. 1976;3:411–421. doi: 10.1080/03014467600001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galan-Lopez L, Barcia-Gonzalez J, Plasencia E. A systematic review of the accuracy and efficiency of dental movements with Invisalign. Korean J Orthod. 2019;49:140–149. doi: 10.4041/kjod.2019.49.3.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haouili N, Kravitz ND, Vaid NR, Ferguson DJ, Makki L. Has Invisalign improved? A prospective follow-up study on the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]