Abstract

A novel serotonin ligand (−)‐MBP was developed for the treatment of schizophrenia that has 5‐HT2A/2B antagonist activity together with 5‐HT2C agonist activity. The multi‐functional activity of this novel drug candidate was characterized using pharmacological magnetic resonance imaging. It was hypothesized (−)‐MBP would affect activity in brain areas associated with sensory perception. Adult male mice were given one of three doses of (−)‐MBP (3.0, 10, 18 mg/kg) or vehicle while fully awake during the MRI scanning session and imaged for 15 min post I.P. injection. BOLD functional imaging was used to follow changes in global brain activity. Data for each treatment were registered to a 3D MRI mouse brain atlas providing site‐specific information on 132 different brain areas. There was a dose‐dependent decrease in positive BOLD signal in numerous brain regions, especially thalamus, cerebrum, and limbic cortex. The 3.0 mg/kg dose had the greatest effect on positive BOLD while the 18 mg/kg dose was less effective. Conversely, the 18 mg/kg dose showed the greatest negative BOLD response while the 3.0 mg/kg showed the least. The prominent activation of the thalamus and cerebrum included the neural circuitry associated with Papez circuit of emotional experience. When compared to vehicle, the 3.0 mg dose affected all sensory modalities, for example, olfactory, somatosensory, motor, and auditory except for the visual cortex. These findings show that (−)‐MBP, a ligand with both 5‐HT2A/2B antagonist and 5‐HT2C agonist activities, interacts with thalamocortical circuitry and impacts areas involved in sensory perception.

Keywords: BOLD imaging, Papez circuit, schizophrenia, serotonin, thalamus

Abbreviations

- 5‐HT

serotonin

- BOLD

blood oxygen level‐dependent

- FOV

field of view

- HASTE

Half Fourier Acquisition Single Shot Turbo Spin Echo

- NEX

number of excitations

- phMRI

pharmacological magnetic resonance imaging

- RARE

rapid acquisition relaxation enhancement

- TE

echo time

- TR

repetition time

1. INTRODUCTION

Serotonin (5‐HT) is a neurotransmitter whose physiological effects are mediated by a family of 5‐HT receptors (5‐HTR). These receptors are categorized into seven classes (5‐HT1 to 5‐HT7) with each class being subdivided into further groups. The 5‐HT2 class is further divided into subtypes 5‐HT2A, 5‐HT2B, and 5‐HT2C. These 5‐HT2 (5‐HT2R) receptor subtypes are G protein‐coupled receptors that act via Gαq/11 coupled activation of phospholipase C, leading to intracellular formation of inositol triphosphate and diacylglycerol and the release of calcium. 5‐HT2AR protein is highly expressed in the cortex and hippocampus and 5‐HT2ARs have been targeted clinically to treat schizophrenia. 5‐HT2B receptors (5‐HT2BRs) are largely found in smooth muscle tissue; however, they are also found in the cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, lateral septum, hypothalamus, and medial amygdala of the brain, and they can modulate dopamine (as well as serotonin) neuronal function. 1 , 2 , 3 5‐HT2C receptors (5‐HT2CRs) are exclusively expressed in the central nervous system with high density in choroid plexus. 5‐HT2CRs play a particularly important role in the ventral tegmentum, nucleus accumbens, and the prefrontal cortex 4 and have been targeted for treatment for various neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, and addiction. 5

First‐generation antipsychotics, like haloperidol, are efficacious at treating psychosis but come with a host of serious off‐target effects, including parkinsonism. Second‐generation antipsychotics, often referred to as atypical antipsychotics, do not improve in efficacy and in fact have been shown to be ineffective in one‐third of patients. An analysis of a new generation of drugs targeting the serotonin (5‐HT) system, more specifically the 5‐HT2CR, as an alternative approach to treat psychoses could prove insightful. 6 Postmortem analysis of patients with a history of schizophrenia showed downregulation of 5‐HT2CRs 7 and suggests a possible role in psychosis. 5‐HT2ARs also may be involved in schizophrenia as blocking these receptors is one proposed mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics. 8 Together, 5‐HT2CR agonism and 5‐HT2AR antagonism may provide a unique and efficacious mechanism for treating psychosis.

Booth and colleagues developed (−)‐trans‐(2S,4R)‐4‐(3′ [meta]‐bromophenyl)‐N,N‐dimethyl‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydronaphthalen‐2‐amine ((−)‐MBP) which has agonist activity at 5‐HT2CRs but competitive antagonist and inverse agonist activities at 5‐HT2ARs and 5‐HT2BRs, 6 , 9 To “fingerprint” or characterize the multi‐functional serotonin 5‐HT2R activities of this molecule, studies were performed on awake mice using blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) pharmacological magnetic resonance imaging (phMRI). This imaging protocol provides information on the integrated neural circuitry engaged by different doses of test compound when the mechanism of action is unknown due to multiple targets. For example, cannabidiol, CBD, is a promiscuous molecule whose mechanism is poorly understood due to its multiple targets. 10 In a recent study on awake mice, Sadaka et al. reported a dose‐dependent effect of CBD that showed an unexpected polarization of brain activity between the hindbrain reticular activating system and the forebrain prefrontal cortex. 11 In this study using (−)‐MBP, we found prominent dose‐dependent changes in the thalamus, sensorimotor cortices, and limbic cortex. This confirmed our hypothesis that (−)‐MBP would affect circuitry involved in sensory perception providing insight into possible therapeutic indications.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animal usage

Male C57BL/J6 mice (n = 40) approximately 100 days of age and weighing between 28 and 30 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Mice were kept in a controlled environment where they experienced a 12‐h cycle of light and darkness. The lights turned on at 07:00 h. They had unrestricted access to food and water. The mice were obtained and taken care of following the guidelines outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Institutes of Health Publications No. 85‐23, Revised 1985). The study followed the regulations set by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Northeastern University, protocol # 21‐0824R and complied with the ARRIVE guidelines, which provide recommendations for reporting in vivo experiments involving animal research. 12

2.2. Drug preparation and administration

(−)‐MBP is a novel compound that functions as a near‐full efficacy agonist at 5‐HT2C receptors and as an inverse agonist/antagonist at 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2B receptor subtypes. 6 , 9 The compound was synthesized as previously described. 9 , 13 Affinities of (−)‐MBP at mouse 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptors are Ki = 26 nM and Ki = 11 nM, respectively. 6 Affinity of (−)‐MBP at the mouse 5‐HT2B receptor is not reported; however, Ki values for (−)‐MBP at the human 5‐HT2A, 5‐HT2B, and 5‐HT2C receptors are 20, 13, and 12 nM, respectively. 3 (−)‐MBP was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl for I.P. injections. Mice were randomly assigned to one of four groups corresponding to saline vehicle, 3.0, 10, or 18 mg/kg given in a volume of 100 μL. These doses were chosen based on the in vivo pharmacology reported by Canal et al. (2014) to block drug‐induced head twitching and hyperlocomotion. 6 Lower doses of (−)‐MBP, 0.1 and 1 mg/kg were ineffective. To deliver the drug remotely during the imaging session, a polyethylene tube (PE‐20), approximately 30 cm in length, was positioned in the peritoneal cavity.

2.3. Awake mouse imaging

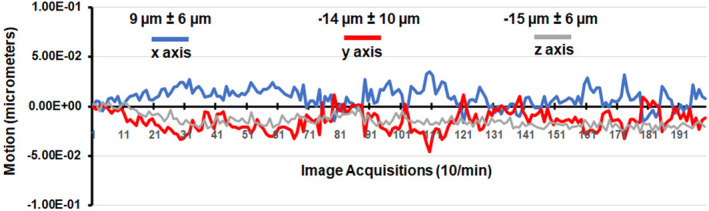

A detailed description of the awake mouse imaging system is published elsewhere. 14 Notably, we used a quadrature transmit/receive volume coil (ID = 38 mm) that provided both high anatomical resolution and high signal‐to‐noise ratio for voxel‐based BOLD fMRI. Furthermore, the unique design of the mouse holder (Ekam Imaging) fully stabilized the head in a cushioned helmet, minimizing discomfort caused by ear bars and other restraint systems that are commonly used to immobilize the head for awake animal imaging. 15 A movie showing the set‐up of a mouse for awake imaging is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W5Jup13isqw. The level of motion artifact combined for mice is shown in Figure 1. Mice with motion exceeding 100 μm, that is greater than one‐half the in‐plane dimensions of a voxel (ca 190 μm2) in any orthogonal direction were excluded from the study. Based on these criteria and loss due to technical issues, the final number of mice in each experimental condition was vehicle (n = 6), 3.0 mg/kg (n = 8), 10 mg/kg (n = 7), 18 mg/kg (n = 8).

FIGURE 1.

Motion artifact. Shown is the degree of motion artifact recorded over the 20 min imaging protocol (200 image acquisitions). The data are reported as the mean and standard deviation in micrometers for axes Y, Z, and X for all mice from each experimental condition (n = 29).

2.3.1. Acclimation

One week before the initial imaging session, all the mice were familiarized with the head restraint and the noise produced by the scanner. Initially, the mice were gently secured in the holding system while under 1%–2% isoflurane anesthesia. Once they regained consciousness, the mice were placed in an enclosed black box designed to simulate an MRI scanner for a period of up to 30 min. This box emitted audio recordings of MRI pulses. This process of acclimation was repeated for four consecutive days in order to minimize the effects caused by the autonomic nervous system during awake animal imaging. The aim was to reduce changes in heart rate, respiration, corticosteroid levels, and motor movements, ultimately improving the quality of the images by enhancing the contrast‐to‐noise ratios. 16 Still other labs have focused on longer periods of acclimation to minimize stress during awake imaging. 15 , 17 , 18

2.4. BOLD phMRI image acquisition and pulse sequence

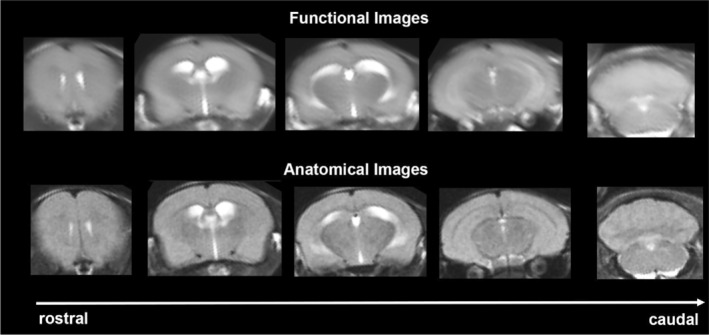

Experiments were conducted using a Bruker BioSpec 7.0T/20‐cm USR horizontal magnet (Bruker) and a 2T/m magnetic field gradient insert (ID = 12 cm) capable of a 120‐μsec rise time. At the beginning of each imaging session, a high‐resolution anatomical data set was collected using the rapid acquisition relaxation enhancement (RARE) pulse sequence (RARE factor 8); (18 slices; 0.75 mm; field of view (FOV) 1.8 cm2; data matrix 128 × 128; repetition time (TR) 2.1 s; echo time (TE) 12.4 msec; Effect TE 48 msec; number of excitations (NEX) 6; 6.5 min acquisition time). Functional images were acquired using a multi‐slice Half Fourier Acquisition Single Shot Turbo Spin Echo (HASTE) pulse sequence (RARE factor 53); (18 slices; 0.75 mm; FOV 1.8 cm; data matrix 96 × 96; TR 6 s; TE 4 msec; Effective TE 24 msec; 20 min acquisition time; in‐plane resolution 187.5 μm2). To provide an illustration, the spatial resolution achieved is sufficient to distinguish the bilateral habenula region with approximately 4–5 voxels allocated for each side. However, it falls short in differentiating between the lateral and medial habenula. The utilization of spin echo was crucial in obtaining functional images that possessed the anatomical accuracy necessary for aligning the data with the mouse MRI atlas, as demonstrated in Figure 2. Each functional imaging session consisted of uninterrupted data acquisitions (whole brain scans) of 200 scan repetitions or acquisitions for a total elapsed time of 20 min. The control window included the first 50 scan acquisitions (18 slices acquired in each), covering a 5 min baseline. Following the control window, an I.P. injection of vehicle or (−)‐MBP was given followed by another 150 acquisitions over a 15 min period. The order of drug doses was randomized over the scanning sessions and blind to the imager which was also true during data analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Neuroanatomical fidelity. Shown are representative examples of brain images collected during a single imaging session using a multi‐slice spin echo, RARE (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement) pulse sequence. The row on the bottom shows axial sections collected during the anatomical scan taken at the beginning of each imaging session using a data matrix of 18 slices; 0.75 mm thickness; FOV 1.8 cm2; data matrix 128 × 128. The row above shows the same images but collected for functional analysis using HASTE, a RARE pulse sequence modified for faster acquisition time. These images were acquired using the same field of view and slice anatomy but a larger data matrix of 96 × 96. Note the anatomical fidelity between the functional images and their original anatomical image. The absence of any distortion is necessary when registering the data to atlas to resolve 132 segmented brain areas.

2.5. Imaging data analysis

The dose‐dependent effect of (−)‐MBP on brain activity was quantified through positive and negative percent changes in BOLD signal relative to baseline. The initial analyses of signal change in individual subjects were done comparing image acquisitions 100–200 to baseline 1–50. The statistical significance of these alterations was evaluated for each voxel (approximately 15 000 per subject) in their original reference system using independent Student's t‐tests. A threshold of 1% was employed to accommodate the typical fluctuations in the BOLD signal observed in the awake rodent brain. To address the issue of multiple t‐tests conducted, a mechanism was implemented to control false‐positive detections, as described by Genovese et al. 19 This mechanism aimed to maintain the average false‐positive detection rate below 0.05. The formula used for this purpose was as follows:

| (1) |

In our analysis, the formula used to control false positives involved evaluating the p‐values (P i ) obtained from the t‐tests for each pixel within the region of interest (ROI). The ROI contained a total of V pixels, and these pixels were ranked based on their probability values. To maintain conservative estimates of significance, a false‐positive filter value (q) of 0.2 was applied. Additionally, the constant c(V) was set to unity, following the approach outlined by Benjamini and Hochberg. 20 The resulting statistical significance was determined based on a 95% confidence level, two‐tailed distributions, and the assumption of heteroscedastic variance for the t‐tests. Pixels that displayed statistical significance retained their relative percentage change values, while all other pixel values were assigned a value of zero.

Voxel‐based percent changes in BOLD signal generated for individual subjects were combined across subjects within the same group to build representative functional maps. To this end, all images were first aligned and registered to a 3D Mouse Brain Atlas© with 132 segmented and annotated brain regions (Ekam Solutions). The co‐registrational code SPM8 was used with the following parameters: Quality: 0.97, Smoothing: 0.35 mm, Separation: 0.50 mm. Gaussian smoothing was performed with a FWHM of 0.8 mm. Image registration involved translation, rotation, and scaling, independently and in all three dimensions. All applied spatial transformations were compiled into a matrix for the ‐th subject. Every transformed anatomical pixel location was tagged with a brain area to generate fully segmented representations of individual subjects within the atlas.

Next, composite maps of the percent changes in BOLD signal were built for each experimental group. Each composite pixel location (row, column, and slice) was mapped to a voxel of the ‐th subject by virtue of the inverse transformation matrix . A tri‐linear interpolation of subject‐specific voxel values determined their contribution to the composite representation. The use of the inverse matrices ensured that the full composite volume was populated with subject inputs. The average of all contributions was assigned as the percent change in BOLD signal at each voxel within the composite representation of the brain for the respective experimental group. The number of activated voxels in each of the 132 regions was then compared between the control and (−)‐MBP doses using a Kruskal‐Wallis test statistic. Those brain areas with significant changes in positive and negative BOLD signal are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The data for all 132 brain areas for both positive and negative BOLD are presented in Files S1 and S2. The data from the Files S1 and S2 on all 132 individual brain areas were then coalesced into brain regions, for example cerebellum, thalamus, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, etc. For example, the thalamus shown in Figure 3 is comprised of 11 brain areas as listed in Table 3. The number of voxels activated for each brain across the four doses was normalized and presented as a percentage of the total volume of all voxels as shown in Figure 3. Each measure for the four experimental groups was compared with a one‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism version 9.1.2 for Windows, (GraphPad Software).

TABLE 1.

(−)‐MBP positive volume of activation dose response.

| Positive BOLD volume of activation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain area | 3 mg | SE | 10 mg | SE | 18 mg | SE | p value | ω Sq |

| Lateral posterior thalamus | 35 | 1.4 | 26 | 2.5 | 18 | 3.3 | .001 | 0.730 |

| Posterior thalamus | 39 | 0.8 | 28 | 3.9 | 23 | 4.0 | .001 | 0.686 |

| Secondary somatosensory ctx | 214 | 3.1 | 166 | 18.3 | 138 | 22.7 | .001 | 0.620 |

| Reticular thalamus | 40 | 0.8 | 32 | 2.4 | 27 | 4.2 | .001 | 0.607 |

| Corpus callosum | 167 | 3.8 | 129 | 13.3 | 94 | 14.9 | .001 | 0.606 |

| Anterior cingulate area | 123 | 2.3 | 88 | 12.5 | 75 | 12.4 | .001 | 0.585 |

| Insular caudal ctx | 94 | 4.4 | 58 | 8.1 | 53 | 5.4 | .001 | 0.575 |

| Olfactory tubercles | 64 | 1.9 | 53 | 5.3 | 42 | 4.4 | .002 | 0.533 |

| Globus pallidus | 102 | 2.4 | 87 | 5.5 | 66 | 11.0 | .002 | 0.528 |

| Internal capsule | 61 | 1.5 | 50 | 5.0 | 35 | 5.3 | .002 | 0.503 |

| Zona incerta | 35 | 1.7 | 27 | 1.5 | 20 | 3.3 | .002 | 0.494 |

| Medial geniculate | 51 | 2.5 | 45 | 2.2 | 34 | 3.6 | .002 | 0.492 |

| External capsule | 51 | 1.9 | 42 | 3.9 | 30 | 4.4 | .002 | 0.489 |

| Anterior thalamus | 57 | 1.5 | 52 | 1.5 | 38 | 6.4 | .004 | 0.450 |

| Primary somatosensory ctx | 782 | 17.9 | 683 | 59.7 | 585 | 77.4 | .004 | 0.446 |

| Pontine reticular n. caudal | 162 | 10.6 | 127 | 11.7 | 97 | 13.7 | .005 | 0.415 |

| Lateral geniculate | 29 | 1.0 | 23 | 2.9 | 18 | 2.1 | .005 | 0.042 |

| Principal sensory n. trigeminal | 99 | 6.0 | 82 | 5.9 | 50 | 12.1 | .007 | 0.391 |

| Primary motor ctx | 197 | 11.4 | 166 | 21.4 | 146 | 21.5 | .007 | 0.382 |

| Ventral thalamus | 206 | 2.5 | 183 | 10.2 | 152 | 24.3 | .008 | 0.372 |

| Auditory ctx | 142 | 5.2 | 126 | 7.2 | 114 | 9.9 | .008 | 0.369 |

| Lateral caudal hypothalamus | 45 | 2.4 | 32 | 4.3 | 38 | 1.3 | .008 | 0.056 |

| Caudate putamen | 684 | 13.5 | 599 | 66.0 | 505 | 77.5 | .009 | 0.362 |

| Rostral piriform ctx | 272 | 12.5 | 230 | 28.5 | 162 | 19.8 | .009 | 0.358 |

| Retrosplenial rostral ctx | 154 | 4.0 | 126 | 12.5 | 106 | 17.8 | .009 | 0.358 |

| Insular rostral ctx | 196 | 10.8 | 162 | 25.2 | 116 | 19.6 | .011 | 0.339 |

| Lateral dorsal thalamus | 34 | 2.8 | 29 | 2.8 | 19 | 3.4 | .011 | 0.337 |

| Ventral pallidum | 80 | 2.2 | 60 | 6.6 | 62 | 4.8 | .013 | 0.326 |

| Granular cell layer | 192 | 28.0 | 162 | 25.5 | 100 | 15.7 | .013 | 0.322 |

| Superior colliculus | 314 | 8.4 | 297 | 17.1 | 214 | 35.6 | .014 | 0.321 |

| Ventral tegmental area | 24 | 1.1 | 16 | 3.3 | 18 | 0.9 | .015 | 0.057 |

| 6th cerebellar lobule | 217 | 12.3 | 156 | 15.9 | 125 | 25.6 | .015 | 0.309 |

| Pontine reticular n. oral | 144 | 6.8 | 116 | 9.9 | 110 | 13.8 | .018 | 0.294 |

| Bed n. stria terminalis | 59 | 0.8 | 46 | 4.3 | 43 | 7.5 | .018 | 0.063 |

| Glomerular layer | 237 | 35.8 | 196 | 31.3 | 109 | 17.7 | .019 | 0.289 |

| Diagonal band of Broca | 25 | 0.7 | 22 | 2.3 | 19 | 1.0 | .020 | 0.284 |

| Central medial thalamus | 21 | 1.3 | 16 | 1.6 | 14 | 3.0 | .021 | 0.280 |

| Paraventricular hypothalamus | 6 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.8 | .021 | 0.039 |

| Anterior olfactory area | 238 | 34.8 | 201 | 30.8 | 165 | 23.9 | .023 | 0.269 |

| Dorsal hippocampal commissure | 10 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.1 | .023 | 2.000 |

| Lateral preoptic area | 13 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.6 | 11 | 2.0 | .029 | 0.342 |

| Parietal ctx | 13 | 0.9 | 8 | 1.3 | 9 | 1.8 | .038 | 0.078 |

| Orbital ctx | 191 | 28.4 | 184 | 26.0 | 153 | 23.1 | .041 | 0.213 |

| Endopiriform area | 29 | 3.3 | 23 | 3.6 | 17 | 3.2 | .041 | 0.213 |

| Subiculum | 253 | 18.6 | 212 | 10.1 | 201 | 20.3 | .041 | 0.015 |

| Mesencephalic reticular formation | 262 | 11.8 | 234 | 7.8 | 202 | 24.0 | .050 | 0.194 |

TABLE 2.

(−)‐MBP negative volume of activation dose response.

| Negative BOLD volume of activation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain area | 3 mg | SE | 10 mg | SE | 18 mg | SE | p value | ω Sq |

| Anterior thalamus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.2 | 8 | 2.8 | .001 | 0.559 |

| Insular rostral ctx | 0 | 0.3 | 10 | 5.7 | 41 | 7.7 | .001 | 0.543 |

| Primary motor ctx | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.4 | 4 | 1.3 | .001 | 0.502 |

| Medial geniculate | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.5 | 5 | 1.7 | .002 | 0.485 |

| Secondary somatosensory ctx | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.9 | 16 | 5.2 | .003 | 0.480 |

| Olfactory tubercles | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 1.3 | 8 | 2.3 | .003 | 0.451 |

| Corpus callosum | 0 | 0.4 | 9 | 3.9 | 32 | 6.5 | .003 | 0.469 |

| Primary somatosensory ctx | 1 | 0.5 | 7 | 4.4 | 41 | 10.4 | .003 | 0.444 |

| Retrosplenial rostral ctx | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 3.7 | 15 | 4.8 | .004 | 0.404 |

| Endopiriform area | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.1 | 3 | 1.9 | .005 | 0.345 |

| Medial dorsal thalamus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | .005 | 0.277 |

| Anterior cingulate area | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.1 | 4 | 1.4 | .006 | 0.411 |

| Internal capsule | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 1.0 | 8 | 3.5 | .008 | 0.372 |

| Rostral piriform ctx | 4 | 4.4 | 10 | 6.5 | 46 | 11.4 | .012 | 0.323 |

| External capsule | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 1.5 | 6 | 1.5 | .014 | 0.326 |

| Frontal association ctx | 0 | 0.3 | 7 | 4.9 | 10 | 3.3 | .018 | 0.237 |

| Zona incerta | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.7 | .018 | 0.290 |

| Central medial thalamus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | .024 | 0.141 |

| Posterior thalamus | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | .024 | 0.250 |

| Reticular thalamus | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 2.5 | .026 | 0.257 |

| Pontine reticular n. caudal | 2 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 3.3 | .027 | 0.263 |

| Principal sensory n. trigeminal | 2 | 1.1 | 4 | 2.1 | 19 | 6.4 | .027 | 0.257 |

| Solitary tract area | 2 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.6 | 11 | 6.0 | .031 | 0.197 |

| CA1 | 1 | 0.9 | 23 | 9.6 | 33 | 9.2 | .031 | 0.206 |

| Insular caudal ctx | 0 | 0.3 | 7 | 3.4 | 15 | 4.7 | .031 | 0.263 |

| Ventral thalamus | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.4 | 10 | 7.7 | .032 | 0.195 |

| CA3 | 2 | 1.6 | 6 | 2.9 | 17 | 6.8 | .036 | 0.196 |

| Caudate putamen | 4 | 2.6 | 16 | 10.5 | 53 | 22.4 | .037 | 0.225 |

| Granular cell layer | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 12.6 | 5 | 2.0 | .038 | 0.206 |

| Inferior colliculus | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 2.5 | 18 | 7.5 | .038 | 0.180 |

| 3rd cerebellar lobule | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 1.2 | 7 | 2.9 | .039 | 0.178 |

| Secondary motor ctx | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.7 | .039 | 0.162 |

| Olivary complex | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.1 | .039 | 0.146 |

| 10th cerebellar lobule | 0 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 6 | 3.3 | .040 | 0.193 |

| Auditory ctx | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.2 | 6 | 2.5 | .042 | 0.203 |

| Dentate gyrus | 1 | 0.8 | 4 | 2.0 | 9 | 3.2 | .044 | 0.166 |

| Accumbens shell | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.5 | .049 | 0.119 |

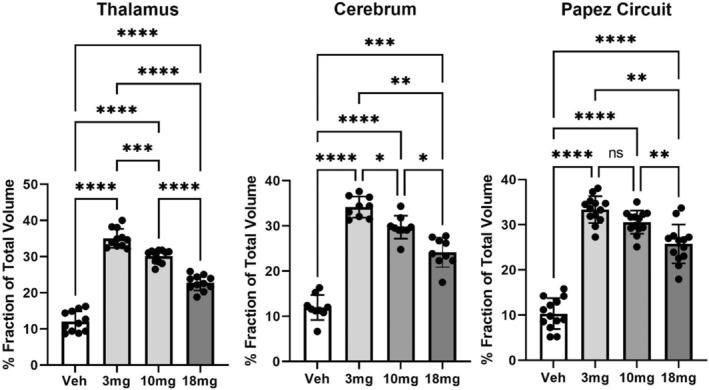

FIGURE 3.

Dose‐dependent effects of (−)‐MBP. Shown are bar graphs (mean ± SD) and dot plots (brain areas) presented as the mean of percent fraction of the total volume of activation in each brain area across all experimental conditions. The inverse response to each dose of (−)‐MBP is significantly different from vehicle and each other with the exception of the 3.0 and 10 mg doses in Papez circuit. *<.05; **<.01; ***<.001; ****<.0001.

TABLE 3.

Dose‐dependent changes in thalamus.

| Positive BOLD volume of activation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain area | 3 mg | SE | 10 mg | SE | 18 mg | SE | p value | ω Sq |

| Lateral posterior thalamus | 35 | 1.4 | 26 | 2.5 | 18 | 3.3 | .001 | 0.730 |

| Posterior thalamus | 39 | 0.8 | 28 | 3.9 | 23 | 4.0 | .001 | 0.686 |

| Reticular thalamus | 40 | 0.8 | 32 | 2.4 | 27 | 4.2 | .001 | 0.607 |

| Zona incerta | 35 | 1.7 | 27 | 1.5 | 20 | 3.3 | .002 | 0.494 |

| Medial geniculate | 51 | 2.5 | 45 | 2.2 | 34 | 3.6 | .002 | 0.492 |

| Anterior thalamus | 57 | 1.5 | 52 | 1.5 | 38 | 6.4 | .004 | 0.450 |

| Lateral geniculate | 29 | 1.0 | 23 | 2.9 | 18 | 2.1 | .005 | 0.042 |

| Ventral thalamus | 206 | 2.5 | 183 | 10.2 | 152 | 24.3 | .008 | 0.372 |

| Lateral dorsal thalamus | 34 | 2.8 | 29 | 2.8 | 19 | 3.4 | .011 | 0.337 |

| Central medial thalamus | 21 | 1.3 | 16 | 1.6 | 14 | 3.0 | .021 | 0.280 |

3. RESULTS

Tables reporting the positive and negative volumes of activation, that is number of voxels activated for all 132 brain areas for vehicle and each dose of (−)‐MBP are provided in Files S1 and S2. There was a robust positive activation with drug as 102/132 brain areas were significantly different across the four experimental groups. When the three doses of (−)‐MBP were compared to each other, a clear dose‐dependent change in positive volume of activation was observed in 46/132 brain areas as shown in Table 1. The brain areas in Table 1 are ranked in order of their significance. Shown highlighted in gray are the mean number of voxels significantly activated following the I.P. injection of vehicle (Veh), 3, 10, and 18 mg/kg of (−)‐MBP with a critical value α < .05 and the omega square (ω Sq) for effect size. A false discovery rate (FDR) for multi‐comparisons gives a significance level of p = .069. Note the trend in activation across all brain areas with the 3 mg/kg dose being the most active and the 18 mg/kg dose the least active. Shown in Table 2 highlighted in gray are the dose‐dependent changes in negative volume of activation. Only 29/132 brain areas showed a significant difference across doses (FDR = 0.044). Interestingly, there was little to no negative BOLD signal change with the 3 and 10 mg/kg doses of (−)‐MBP, while the highest dose of 18 mg/kg caused the greatest increase in negative BOLD. The trends would suggest that the positive and negative volume of activation are inversely correlated with the 18 mg/kg dose showing the lowest positive activation but the highest negative response. It should be noted that mice administered the 3 mg/kg dose of (−)‐MBP were observed to be devoid of movement and non‐reactive to toe pinch for approximately 15–20 min after being removed from the magnet or approximately 30 min after drug administration. This behavior was not observed with the 10 and 18 mg/kg doses.

The brain areas most represented in Table 1 are localized to the thalamus and cerebral cortex. Tables 2 and 3 list these areas, while Figure 3 shows bar graphs (mean ± SD) and dot plots (brain areas) for each dose of (−)‐MBP and vehicle for thalamus and cerebral cortex. A one‐way ANOVA showed a significant (p < .0001) difference between doses for thalamus (F (2.183,21.83) = 144.3) and cerebral cortex (F (2.520,20.16) = 82.11). Tukey's multiple comparisons showed all doses for each brain region were significantly different from vehicle and from each other (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Dose‐dependent changes in cerebral cortex.

| Positive BOLD volume of activation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain area | 3 mg | SE | 10 mg | SE | 18 mg | SE | p value | ω Sq |

| Secondary somatosensory ctx | 214 | 3.1 | 166 | 18.3 | 138 | 22.7 | .001 | 0.620 |

| Anterior cingulate ctx | 123 | 2.3 | 88 | 12.5 | 75 | 12.4 | .001 | 0.585 |

| Insular caudal ctx | 94 | 4.4 | 58 | 8.1 | 53 | 5.4 | .001 | 0.575 |

| Primary somatosensory ctx | 782 | 17.9 | 683 | 59.7 | 585 | 77.4 | .004 | 0.446 |

| Primary motor ctx | 197 | 11.4 | 166 | 21.4 | 146 | 21.5 | .007 | 0.382 |

| Auditory ctx | 142 | 5.2 | 126 | 7.2 | 114 | 9.9 | .008 | 0.369 |

| Rostral piriform ctx | 272 | 12.5 | 230 | 28.5 | 162 | 19.8 | .009 | 0.358 |

| Retrosplenial rostral ctx | 154 | 4.0 | 126 | 12.5 | 106 | 17.8 | .009 | 0.358 |

| Insular rostral ctx | 196 | 10.8 | 162 | 25.2 | 116 | 19.6 | .011 | 0.339 |

| Parietal ctx | 13 | 0.9 | 8 | 1.3 | 9 | 1.8 | .038 | 0.078 |

| Orbital ctx | 191 | 28.4 | 184 | 26.0 | 153 | 23.1 | .041 | 0.213 |

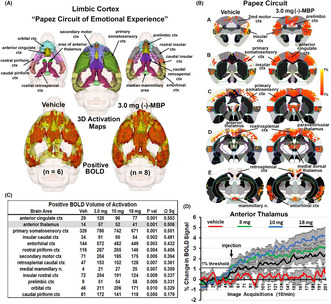

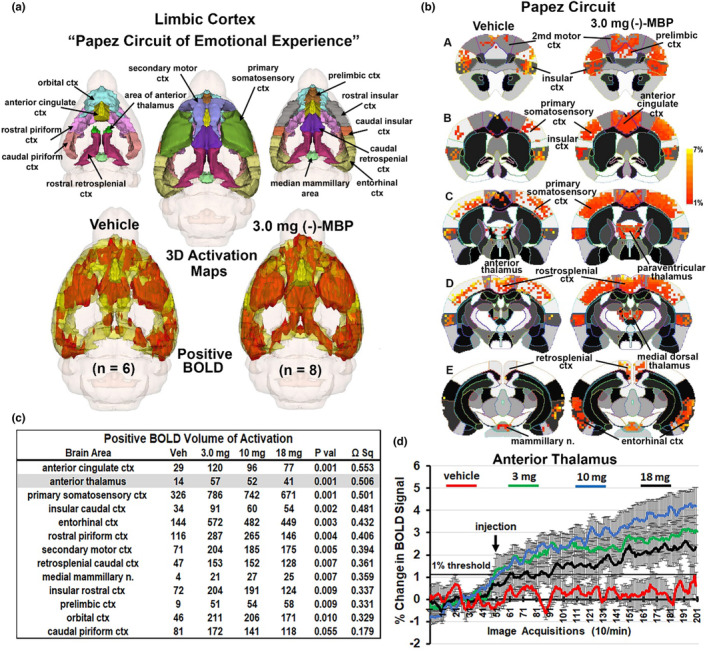

Figure 4a shows the rat equivalent of Papez circuit and its different brain areas as color‐coded 3D volumes. These areas are coalesced as a single volume in yellow below with the average positive BOLD signal shown in red for vehicle and the 3.0 mg dose of (−)‐MBP. Figure 4b is 2D activation maps showing the average positive BOLD signal change as individual voxels displayed on the mouse MRI segmented atlas. The BOLD signal change for vehicle and 3.0 mg/kg (−)‐MBP for each voxel is the average of all areas shown in the table (Figure 4c) that comprise Papez circuit. The table lists all these areas in order of their significance (critical value <0.05) and effect size (omega square). The anterior thalamus (highlighted in gray) is considered the key node in Papez circuit. The time course in BOLD signal change in the anterior thalamus for vehicle and each dose of (−)‐MBP is shown in Figure 4d. I.P injections occurred at approximately the 50th image acquisition (5 min from onset of imaging). A repeated measures mixed effects analysis showed a main effect for treatment (F (3,24) = 6.424, p < .0024) and a significant interaction between time and treatment (F (597,4776) = 3.810, p < .0001).

FIGURE 4.

Circuit of Papez. (a) Shows the color‐coded 3D volumes that comprise Papez circuit. These volumes are coalesced into a single yellow volume below showing the average positive BOLD signal (red) from all subjects. (b) To the right is 2D activation maps from the rat brain atlas showing the precise location of the significantly positive (red) BOLD voxels. Each voxel is the average signal from all subjects for vehicle or 3.0 mg dose of (−)‐MBP. The table in (c) is the brain areas that comprise Papez circuit ranked in order of significance. The time course plot in (d) to the right shows the percent change in BOD signal for the anterior thalamus for each experimental condition over the 20 min scanning session. Arrow denotes time of I.P. injection. Vertical lines denote SE.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study evaluated the dose‐dependent changes in BOLD signal across the entire mouse brain in response to a serotonin ligand (−)‐MBP that is a near‐full efficacy agonist at 5‐HT2C receptors and an inverse agonist/antagonist at 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2B receptor subtypes. BOLD imaging in awake rodents has been used to characterize the immediate effects of numerous drugs on brain activity. 11 , 15 , 21 , 22 In this case, the fingerprint or pattern of BOLD activity across 132 brain areas represents a complex interaction between different serotonin receptors across discrete brain areas. Pharmacological MRI is a method to assess the global integrated neural circuitry underpinning the behavioral effects of CNS therapeutics independent of their specific biochemical mechanism. 23 In this study, 74/132 brain areas showed a dose‐dependent change in activation predominantly in thalamus, cerebrum, and limbic circuitry. These data are discussed with respect to serotonergic signaling in neural circuitry that may be involved in psychiatric illness, particularly psychosis.

5HT2C receptors have a widespread distribution in the brain, whereas 5HT2A receptors are concentrated in a few areas such as the cortex, and both receptors show overlapping distribution in some areas. 24 Multiple reports have mentioned the presence of both 5HT2A and 5HT2C receptors in thalamic regions such as lateral and medial geniculate nucleus, reticular nucleus, and zona incerta. 24 , 25 , 26 Given the presence of both receptors in thalamus, the observed decreasing dose response may be attributed to inactivation of 5HT2A receptors at low concentration (due to 5‐HT2A antagonism/inverse agonism) and activation of 5HT2C receptors (due to 5‐HT2C agonism) at high concentration. An expected outcome of a 5HT2C agonist alone would have been a dose‐dependent increase in activation in regions with high 5HT2C receptor expression. However, multiple factors might be responsible for the decreasing negative BOLD signal, dose response observed in this study, as (−)‐MBP also has a competitive antagonist effect at the histamine H1 receptor. 6 The present study showed activation of nearly all of the cerebrum. It is reported that there is significant colocalization of both receptors in rat medial prefrontal cortex with a higher concentration of 5HT2A. 27

In this study, (−)‐MBP activated nearly all areas of the thalamus. There was a significant decreasing BOLD signal, dose–response with the exception of the anterior pretectal nucleus and parafascicular nucleus. Previous studies have shown that 5‐HT2CRs are widely distributed and abundant in the thalamus of rodents including the parafascicular nucleus. 28 This inconsistency may be due to the presence of 5‐HT2ARs in the parafascicular nucleus, whose deactivation by (−)‐MBP is masking the excitation of 5‐HT2CRs in this region. 29 Our current results align well with what is known about the distribution of 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptors in the thalamus. The thalamus acts as a filter for sensory input before relaying this information to the cortex. 30 5‐HT2ARs and 5‐HT2CRs have both proven to be prominent targets for mood‐related disorders. 31 Given the known role of the thalamus as a sensory filter, (−)‐MBP's activation of the thalamus should increase its ability to filter sensory input prior to relaying it to the cortex. Together, the known information about 5‐HT2ARs, 5‐HT2CRs, as well as the thalamus' function, suggests that (−)‐MBP may be efficacious in diseases and disorders where the thalamus's activity is downregulated, or sensory input is upregulated.

The activation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus together with other midline dorsal thalamic nuclei (e.g., paraventricular, medial dorsal, and central nuclei) is particularly interesting because the anterior nucleus is the cornerstone of the neural circuitry of emotion first proposed by Cannon 32 and popularized by Papez. 33 The “Papez circuit” connects the hypothalamus and hippocampus to the limbic cortex through the anterior thalamus and midline dorsal thalamic nuclei. These thalamic nuclei receive extensive afferent connections from the hippocampus 34 , 35 and the mammillary nuclei. 36 These midline thalamic nuclei send primary projections to the anterior cingulate, retrosplenial, prefrontal, and orbital cortices and adjacent cortical areas. The rodent equivalent of the Papez circuit was described by Kulkarni et al., while imaging the innate response to the highly attractive smell of almond in rats. 37 Indeed, we have used the almond‐induced pattern of BOLD activation described by Kulkarni et al., to create the circuit of Papez shown in Figure 4.

As noted above, mice administered the 3.0 mg/kg dose of (−)‐MBP were observed to be devoid of movement and non‐reactive to toe pinch for approximately 15–20 min after being removed from the magnet, or approximately 30 min after drug administration. This observation is difficult to explain given the published findings that (−)‐MBP lacks sedative and locomotor effects. 6 This outcome may be related to 5‐HT2C receptor negative modulation of dopamine release. 38 It has been reported that 5HT2CR agonism mediates tonic inhibition of frontal‐cortical dopaminergic transmission. 39 A previous study has shown that selective 5‐HT2CR antagonists have the potential to reverse haloperidol‐induced catalepsy with a significant increase of 5HT2CR levels in medial dorsal thalamus. 38 Reavill et al. found that 5HT2CRs play an important role in catalepsy. 40 Given the activation of the medial dorsal thalamus by (−)‐MBP in this current study, and (−)‐MBP's known action as a 5‐HT2CR agonist, we speculate that dopamine levels were decreased by the agonistic activity of (−)‐MBP at 5‐HT2CRs, thus inhibiting motion and pain response of the mice. This is consistent with the results of previous behavioral studies in which selective 5HT2CR agonists cause a decrease in locomotor activity in mice, while 5‐HT2A agonists cause an increase in locomotor activity. 41 Likewise, the 5‐HT2B inverse agonist/antagonist activity of (−)‐MBP should be considered regarding its effects on locomotor activity. For example, 5‐HT antagonists reduce PCP‐induced hyperlocomotion (without inducing catalepsy) and reduce amphetamine‐induced hyperlocomotion in rats. 3 , 42 Another possible mechanism for the decrease in locomotion at low doses of (−)‐MBP might be the involvement of histamine H1 receptors, a potential off‐target where (−)‐MBP has appreciable affinity, Ki = 30 nM. 13 The absence of locomotor effects at higher doses of (−)‐MBP used in the current studies is puzzling, but nonetheless bodes well for beneficial psychotropic effects without locomotor and sedative effects.

4.1. Data interpretation

Ideally, brain and blood should have been collected at the end of the imaging session to ascertain the actual levels of (−)‐MBP at each dose. The choice of drug doses in phMRI is usually based on preclinical behavioral pharmacology. In this case, the dose range was taken from Canal et al., looking at the ability of (−)‐MBP to block the head twitching effect of 5HT2 agonists and amphetamine‐induced hyperlocomotion in male C57BL/J6 mice. 6 The 10 mg/kg dose of (−)‐MBP was effective in significantly decreasing both behavioral measures by 10 min after administration. The present study shows a dose‐dependent decrease in positive BOLD in thalamus and cortex within 15 min of drug administration that could explain the blocking effects of (−)‐MBP. Canal et al. reported doses of 0.1 and 1.0 mg/kg of (−)‐MBP were ineffective in blocking drug‐induced head twitching and hyperlocomotion. It would have been interesting to see if these lower doses would have caused a dose‐dependent increase in positive BOLD creating an inverted U‐shaped dose‐response curve.

5. SUMMARY

The present study was performed using phMRI in mice treated with (−)‐MBP and showed a dose‐dependent decrease in BOLD signal in brain regions, especially thalamus, cerebrum, and limbic cortex. With respect to serotonergic signaling the pattern of neural activation based on previous literature would suggest (−)‐MBP might have therapeutic efficacy in psychiatric illness, particularly psychosis. 5‐HT2AR antagonism has been associated with antipsychotic‐like effects. 43 Indeed, clozapine, a highly effective atypical antipsychotic, acts through antagonism of 5‐HT2ARs and multiple dopamine receptors, with many off‐target effects including histamine H1 receptors and 5‐HT2CRs. Given the agonism of (−)‐MBP at 5‐HT2CRs, antagonism at 5‐HT2ARs, and its robust thalamic/cortical response that entails Papez circuit, this drug may have benefits similar to clozapine but with fewer side effects. Also, further attention should be paid to the cortical feedback to the thalamic reticular nucleus that exerts GABAergic control over the primary thalamic projections to sensory and motor cortices aiding in filtering and regulating sensory neurotransmission.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

This work was done by graduate students Preeti K. Sathe, Gargi R. Ramdasi, Kaylie Giammatteo, Harvens Beauzile, Shuyue Wang, and Heng Zhang, to satisfy a course requirement. All contributed equally to the data generation, analysis, and manuscript preparation. Praveen Kulkarni, Raymond G. Booth, and Craig F. Ferris contributed to the concept, experimental design, drafting, manuscript preparation, and interpretation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Craig F. Ferris has a financial interest in Animal Imaging Research, a company that makes radiofrequency electronics and holders for awake animal imaging. Craig F. Ferris and Praveen Kulkarni have a partnership interest in Ekam Solutions a company that develops 3D MRI atlases for animal research.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The protocol (# 21‐0824R) used in this study complied with the regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Northeastern University.

Supporting information

File S1

File S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for these studies was provided by the National Institutes of Health R01‐047130 to RGB. We also thank Ekam Imaging and the Department Pharmaceutical Sciences for financial support.

Sathe PK, Ramdasi GR, Giammatteo K, et al. Effects of (−)‐MBP, a novel 5‐HT2C agonist and 5‐HT2A/2B antagonist/inverse agonist on brain activity: A phMRI study on awake mice. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2023;11:e01144. doi: 10.1002/prp2.1144

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cathala A, Lucas G, Lopez‐Terrones E, Revest JM, Artigas F, Spampinato U. Differential expression of serotonin(2B) receptors in GABAergic and serotoninergic neurons of the rat and mouse dorsal raphe nucleus. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2022;121:103750. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2022.103750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Devroye C, Cathala A, Piazza PV, Spampinato U. The central serotonin(2B) receptor as a new pharmacological target for the treatment of dopamine‐related neuropsychiatric disorders: rationale and current status of research. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;181:143‐155. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devroye C, Cathala A, Haddjeri N, et al. Differential control of dopamine ascending pathways by serotonin2B receptor antagonists: new opportunities for the treatment of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2016;109:59‐68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wold EA, Wild CT, Cunningham KA, Zhou J. Targeting the 5‐HT2C receptor in biological context and the current state of 5‐HT2C receptor ligand development. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19:1381‐1398. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190709101449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoyer D, Hannon JP, Martin GR. Molecular, pharmacological and functional diversity of 5‐HT receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:533‐554. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00746-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canal CE, Morgan D, Felsing D, et al. A novel aminotetralin‐type serotonin (5‐HT) 2C receptor‐specific agonist and 5‐HT2A competitive antagonist/5‐HT2B inverse agonist with preclinical efficacy for psychoses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349:310‐318. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.212373.PMC3989798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chagraoui A, Thibaut F, Skiba M, Thuillez C, Bourin M. 5‐HT2C receptors in psychiatric disorders: a review. Progr Neuro‐Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;66:120‐135. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Felsing DE, Anastasio NC, Miszkiel JM, Gilbertson SR, Allen JA, Cunningham KA. Biophysical validation of serotonin 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptor interaction. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Casey AB, Mukherjee M, McGlynn RP, Cui M, Kohut SJ, Booth RG. A new class of 5‐HT(2A) /5‐HT(2C) receptor inverse agonists: synthesis, molecular modeling, in vitro and in vivo pharmacology of novel 2‐aminotetralins. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179:2610‐2630. doi: 10.1111/bph.15756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McPartland JM, Duncan M, Di Marzo V, Pertwee RG. Are cannabidiol and Delta(9)‐tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:737‐753. doi: 10.1111/bph.12944.PMC4301686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sadaka AH, Ozuna AG, Ortiz RJ, et al. Cannabidiol has a unique effect on global brain activity: a pharmacological, functional MRI study in awake mice. J Transl Med. 2021;19:220. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02891-6.PMC8142641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG; Group NCRRGW . Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577‐1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x.PMC2936830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sakhuja R, Kondabolu K, Cordova‐Sintjago T, et al. Novel 4‐substituted‐N,N‐dimethyltetrahydronaphthalen‐2‐amines: synthesis, affinity, and in silico docking studies at serotonin 5‐HT2‐type and histamine H1 G protein‐coupled receptors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:1588‐1600. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.060.PMC4363177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferris CF, Kulkarni P, Toddes S, Yee J, Kenkel W, Nedelman M. Studies on the Q175 Knock‐in model of Huntington's disease using functional imaging in awake mice: evidence of olfactory dysfunction. Front Neurol. 2014;5:94. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00094.PMC4074991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferris CF. Applications in awake animal magnetic resonance imaging. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:854377. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.854377.PMC9017993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. King JA, Garelick TS, Brevard ME, et al. Procedure for minimizing stress for fMRI studies in conscious rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;148:154‐160. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.04.011.PMC2962951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stenroos P, Paasonen J, Salo RA, et al. Awake rat brain functional magnetic resonance imaging using standard radio frequency coils and a 3D printed restraint kit. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:548. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00548.PMC6109636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang PC, Procissi D, Bao Q, Centeno MV, Baria A, Apkarian AV. Novel method for functional brain imaging in awake minimally restrained rats. J Neurophysiol. 2016;116:61‐80. doi: 10.1152/jn.01078.2015.PMC4961750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage. 2002;15:870‐878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B Methodol. 1995;57:289‐300. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferris CF, Kulkarni P, Yee JR, Nedelman M, de Jong IEM. The serotonin receptor 6 antagonist Idalopirdine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil have synergistic effects on brain activity‐a functional MRI study in the awake rat. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:279. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00279.PMC5467007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferris CF, Yee JR, Kenkel WM, et al. Distinct BOLD activation profiles following central and peripheral oxytocin administration in awake rats. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:245. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00245.PMC4585275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Borsook D, Becerra L, Hargreaves R. A role for fMRI in optimizing CNS drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:411‐424. doi: 10.1038/nrd2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pompeiano M, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Distribution of the serotonin 5‐HT2 receptor family mRNAs: comparison between 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptors. Mol Brain Res. 1994;23:163‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoffman BJ, Mezey E. Distribution of serotonin 5‐HT1C receptor mRNA in adult rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1989;247:453‐462. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81390-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:264‐355. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011478.PMC4813425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nocjar C, Alex KD, Sonneborn A, Abbas AI, Roth BL, Pehek EA. Serotonin‐2C and‐2a receptor co‐expression on cells in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2015;297:22‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clemett DA, Punhani T, S. Duxon M, Blackburn TP, Fone KCF. Immunohistochemical localisation of the 5‐HT2C receptor protein in the rat CNS. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:123‐132. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00086-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chung KKMM, Herbert J. Central serotonin depletion modulates the behavioural, endocrine and physiological responses to repeated social stress and subsequent c‐fos expression in the brains of male rats. Neuroscience. 1999;92:613‐625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yasuno F, Suhara T, Okubo Y, et al. Low dopamine D2Receptor binding in subregions of the thalamus in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1016‐1022. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Julius D, Huang KN, Livelli TJ, Axel R, Jessell TM. The 5HT2 receptor defines a family of structurally distinct but functionally conserved serotonin receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:928‐932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cannon WB. The James‐Lang theory of emotion: a critical examination and an alternative theory. Am J Psychol. 1927;39:106‐124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papez JW. A proposed mechanism of emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725‐743. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sikes RW, Chronister RB, White LE. Origin of the direct hippocampus‐anterior thalamic bundle in the rat: a combined horseradish peroxidase‐Golgi analysis. Exp Neurol. 1977;57:379‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Swanson LW, Cowan WM. An autoradiographic study of the organization of the efferent connections of the hippocampal formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:49‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seki M, Zyo K. Anterior thalamic afferents from the mamillary body and the limbic cortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229:242‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kulkarni P, Stolberg T, Sullivanjr JM, Ferris CF. Imaging evolutionarily conserved neural networks: preferential activation of the olfactory system by food‐related odor. Behav Brain Res. 2012;230:201‐207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Creed‐Carson M, Oraha A, Nobrega JN. Effects of 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptor antagonists on acute and chronic dyskinetic effects induced by haloperidol in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2011;219:273‐279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Millan M, Dekeyne A, Gobert A. Serotonin (5‐HT) 2C receptors tonically inhibit dopamine (DA) and noradrenaline (NA), but not 5‐HT, release in the frontal cortex in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:953‐955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reavill C, Kettle A, Holland V, Riley G, Blackburn TP. Attenuation of haloperidol‐induced catalepsy by a 5‐HT2Creceptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:572‐574. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Halberstadt AL, Van Der Heijden I, Ruderman MA, et al. 5‐HT2A and 5‐HT2C receptors exert opposing effects on locomotor activity in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1958‐1967. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Auclair AL, Cathala A, Sarrazin F, et al. The central serotonin 2B receptor: a new pharmacological target to modulate the mesoaccumbens dopaminergic pathway activity. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1323‐1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lally J, Gaughran F, Timms P, Curran SR. Treatment‐resistant schizophrenia: current insights on the pharmacogenomics of antipsychotics. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2016;9:117‐129. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S115741.PMC5106233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File S1

File S2

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.