Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether prolactin (PRL) regulates the proliferation of pigeon crop epithelium through the Hippo signaling pathway during the breeding cycle. Twenty-four pairs of adult pigeons were allotted to four groups by different breeding stages, and their crops and serum were sampled. Eighteen pairs of young pigeons were selected and divided into three groups for the injection experiments. The results showed that the serum PRL content and crop epithelial thickness of pigeons increased significantly at day 17 of incubation (I17) and day 1 of chick-rearing (R1). In males, the mRNA levels of yes-associated transcriptional regulator (YAP) and snail family transcriptional repressor 2 (SNAI2) were peaked at I17, and the gene levels of large tumor suppressor kinase 1 (LATS1), serine/threonine kinase 3 (STK3), TEA domain transcription factor 3 (TEAD3), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), MYC proto-oncogene (c-Myc) and SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2) reached the maximum value at R1. In females, the gene expression of YAP, STK3, TEAD3, and SOX2 reached the greatest level at I17, the expression profile of SAV1, CTGF, and c-Myc were maximized at R1. In males, the protein levels of LATS1 and YAP were maximized at R1 and the CTGF expression was upregulated at I17. In females, LATS1, YAP, and CTGF reached a maximum value at I17, and the expression level of phosphorylated YAP was minimized at I17 in males and females. Subcutaneous injection of prolactin (injected for 6 d, 10 μg per kg body weight every day) on the left crop of pigeons can promote the proliferation of crop epithelium by increasing the CTGF level and reducing the phosphorylation level of YAP. YAP-TEAD inhibitor verteporfin (injection for 6 d, 2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) can inhibit the proliferation of crop epithelium induced by prolactin by inhibiting YAP and CTGF expression. In conclusion, PRL can participate in crop cell proliferation of pigeons by promoting the expression of YAP and CTGF in Hippo pathway.

Keywords: connective tissue growth factor, crop proliferation, hippo pathway, pigeon, prolactin

PRL can promote the proliferation of crop epithelium in pigeons by regulating the Hippo pathway.

Introduction

Pigeons are altricial birds, and baby squabs (Columba livia domestica) need to rely on the crop milk secreted by the crop tissue of both parents to survive during the early stage (Bharathi et al., 1997). Pigeon crops are composed of two lateral leaves beside the esophagus, and the crop wall contains the outer membrane, muscular layer, and mucosa (Sales and Janssens 2003; Gillespie et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2016). During lactation, the cell division of basal cells and intermediate cells in the mucosal epithelium of the crop will be activated under prolactin (PRL) stimulation, resulting in an enlarged and thickened crop wall, with increasing papillary hyperplasia of the epithelium (Gillespie et al., 2011). Finally, the volume and thickness of the crop wall increased significantly by 2–3 times (Carr and James 1931; Hu et al., 2016).

PRL is a protein hormone secreted by eosinophils in the anterior pituitary, which is widely present in animals (Wilkanowska et al., 2014). In mammals, the main function of PRL is to promote the proliferation of mammary cells and maintain lactation ability (Skwarło-Sońta 1992). Similarly, a number of studies have shown the important role of PRL in pigeon crop proliferation (Anderson et al., 1984; Chen et al., 2020). Nicoll (1990) pointed out that exogenous prolactin can induce the proliferation of crop epithelial mucosa. Chen et al. (2020) found that wing vein injection of bromocriptine mesylate injection (a specific inhibitor of PRL) could lead to a decrease in the relative weight and thickness of pigeon crops. Although it has been confirmed that PRL can promote crop proliferation of pigeons, it is still unclear what signal transduction mechanism it plays.

The Hippo pathway is a newly discovered growth signal transduction pathway that exists widely in multicellular organisms, and it plays an important role in promoting cell proliferation (Kango-Singh and Singh 2009; Pan 2010; Deng et al., 2016). The Hippo pathway was first discovered in Drosophila, and its transmission mechanism of it is as follows: when it is activated, the upstream kinases, namely, salvador homology 1 (SAV1) and MOB kinase activator 1 (MOB1), bind to serine/threonine kinase 3 (STK3) and large tumor suppressor 1/2 (LATS1/2), respectively. The yes-associated protein (YAP) is then phosphorylated by the LATS1/2-STK3 complex. Eventually, YAP is localized to the cytoplasm and degraded by ubiquitination. The LATS1/2-STK3 complex is not activated when the Hippo pathway is inhibited, and the YAP protein is dephosphorylated and enters the nucleus, thereby binding to the TEA domain transcription factor (TEAD) family to induce cell proliferation (Tremblay and Camargo 2012).

The Hippo pathway is important for the development of animal tissues, including proliferation of mouse myoblasts, skeletal muscle growth in Drosophila, and longissimus dorsi development in Hu sheep (Sun et al., 2014; Deng et al., 2016; Watt et al., 2018). Overexpression of the YAP gene promotes cell proliferation and differentiation in Hu sheep myoblasts or skeletal muscle satellite cells by activating the MCAT element, a specific promoter of skeletal muscle genes (Sun et al., 2014). Significant increases have been observed in the relative weight of the heart, stomach, and spleen of mouse embryos when the expression of the SAV1, STK3, or LATS1/2 genes is inhibited or knocked down (Del Re et al., 2013). YAP promotes the proliferation of intestinal mucosal epithelial cells in mice by activating the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which is significantly activated during pigeon crop proliferation (Chen et al., 2020; Deng et al., 2022). In addition, Ding et al. (2021) reported that the mRNA levels of LATS2 are significantly greater in the breast muscle of 10-d-old squads compared to the embryonic period. Thus, the Hippo pathway is highly conserved in most species, here, we propose a hypothesis that PRL may promote the proliferation of pigeon crop epithelium cells through the Hippo pathway.

The proliferation of pigeon crop tissues is the basis for the formation of crop milk. However, the mechanism of crop proliferation has not been studied (Shetty et al., 1994; Xie et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2023a). Understanding the mechanism of epithelial cell proliferation in pigeon crops is of great significance for research on crop milk formation. Therefore, the expression levels of Hippo pathway-related genes and proteins in the crop tissues of pigeons during different breeding stages were measured in the present study, and the relationship among PRL, the Hippo pathway, and pigeon crop epithelium proliferation was investigated by in vivo injection experiments.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for experimental animals developed by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. All animal experimental protocols were approved by Department of Scientific Research, Institute of Animal Science, Yangzhou University.

Birds and housing

In total, 24 pairs of adult White King pigeons (24 males and 24 females, 60 wk old; average weight 560 ± 15 g) and 18 young White King pigeons (3 mo old, mixed sex, average weight 380 ± 20 g) were obtained from a commercial pigeon farm (Tianyi Pigeon Industry, Co., Ltd., China). All adult pigeons were selected from a large group (approximately 2,000 pairs) with the same oviposition interval. To maintain the hatching ability of parental pigeons, plastic eggs were added to the cage after the second egg was laid (Xie et al., 2018). Each pair of adult pigeons and young pigeons were housed in an artificial birdhouse equipped with a nest and shelter. The birds were fed a diet based on corn, soybean meal, and wheat (16.67% crude protein, 12.00 MJ/kg metabolic energy, 1.13% calcium, 0.34% available phosphorus, 0.89% lysine, and 0.31% methionine). Nutritional levels were referenced in a previous study (Xie et al., 2016). The birds had free access to feed, sand, and water. During the entire experiment, 16 h of light was provided every day, and the mean daily temperature was 23 ± 4 °C.

Experimental design and sample collection

Experiment 1: A total of 24 pairs of adult pigeons were divided into the following groups according to different breeding stages, with six pairs of pigeons in each sample group: incubation day 4 (I4), incubation day 17 (I17), chick-rearing day 1 (R1), and chick reading day 25 (R25). Every six pairs were sampled at specific breeding stages. Each pigeon was subjected to a 50-d study, including a 7-d domestication period and a 43-d experimental period (18 d of incubation and 25 d of chick-rearing), and the grouping of pigeons was completed before 50-d study. The baby squabs were transferred to the commercial pigeon farm and taken care of by other parent pigeons. After the 50-d study period, 24 pairs of pigeons were euthanized by cervical dislocation to collect the crop tissues. Samples were rapidly divided into two parts as follows: one was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent inspection; the other was stored in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature.

Experiment 2: A total of 18 young pigeons were divided into the following three groups: control group, PRL group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP) group. All pigeons were injected in the left crop leaves. The control group was injected with 0.9% normal saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), followed by injection with 2 mg 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU; Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) per kg body weight every day. The PRL group was injected with PRL (Sino Biological Inc., Beijing, China, 10 μg per kg body weight every day), followed by injection with EdU. The PRL+VP group was injected with VP (Med Chem Express Llc., Shanghai, China, 2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, followed by injection with EdU. The injections were performed at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d. On day 7 of the experiment, all young pigeons were euthanized by cervical dislocation to collect the left crop leaf tissues. The crop sample was divided into two parts as follows: one was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent inspection; the other was stored in 4% paraformaldehyde solution at room temperature.

Histological examinations

The fixed tissues were then cut into slices as previously reported by Wan et al. (2019). Briefly, the crop samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for up to 48 h, and the samples were then dehydrated, cleared, and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded samples were then sectioned (7 μm) and placed on glass slides. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed as previously reported by Zhu et al. (2023b), and slides were evaluated under light microscopy (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The epithelial thickness of the crop tissue was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA).

Tissue RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

According to the methods reported by Zhu et al. (2023a), frozen samples were ground to a fine powder using liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from crop tissue (80–100 mg) using TRIzol, and genomic DNA was eliminated by RNase-free DNase (Takara, Dalian, China). The quality of total RNA was examined by native RNA electrophoresis and the UV absorbance ratio at 260 nm and 280 nm, respectively. cDNA was synthesized using oligo dT-adapter primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Takara, Dalian, China) at 42 °C for 60 min.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The mRNA profiles of YAP, large tumor suppressor kinase 1 (LATS1), salvador homology 1 (SAV1), serine/threonine kinase 3 (STK3), TEA domain transcription factor 3 (TEAD3), TEAD4, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), MYC proto-oncogene (c-Myc), SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2), snail family transcriptional repressor 2 (SNAI2), and 18S were detected by qRT‒PCR using an ABI Step-One Plus Real-Time PCR system (ABI7500, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a SYBR Premix PCR kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The thermocycler program was as follows: 95 °C for 30 s followed by 42 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The standard curve was determined using pooled samples. Three replicates were used for each sample, and the sample without cDNA template was used as a negative control. The specificity of the amplification was verified by a melting curve analysis, with 18S as the internal control. The calibrator for each gene was the average ΔΔCt value of the I4 stage, and the relative expression was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The primers designed by Primer Premier 5.0 software are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in the present study

| Gene1) | Nucleotide sequences (5’→3’)2 | Acession No. | Bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| YAP | F: GAACGTTACAGCTCCCACCA | XM_021286320 | 185 |

| R: GCTGATTCATGGCAAAGCGT | |||

| LATS1 | F: AAGCTATTCCCCTCAAGCCT | XM_005507637 | 127 |

| R: TGACAATCCAACCCGCATCA | |||

| SAV1 | F: GAGGCACACTTCAGGCATCG | XM_005505159 | 162 |

| R: CTCCAGTGAGTCGTGTTCGT | |||

| STK3 | F: TGCAACAATGTGACAGTCCCT | XM_005499485 | 110 |

| R: TATGTCCGAAACAGAGCCCG | |||

| TEAD3 | F: ACCAGGTTGGCATCAAGGTCT | XM_005513694 | 121 |

| R: TGCAGAGCCTTATCCTTCGAG | |||

| TEAD4 | F: AGCCCTCTTCCTCTGGTTCTTC | XM_013369478 | 175 |

| R: CACACACCCTCAGCGTCATT | |||

| CTGF | F: TTGCGACCACCATAAGGGAC | XM_005509387 | 129 |

| R: AAGGACTCTCCGCTCCGATA | |||

| c-Myc | F: AGCAGCGACTCGGAAGAAGAA | XM_005510814 | 154 |

| R: TGGAAGGAGAAGCGGCATAA | |||

| SOX2 | F: CATTGACGAAGCTAAGCGGC | XM_005506585 | 152 |

| R: TCGTCATGGTATTGGTGCCC | |||

| SNAI2 | F: CACATCAGGACCCACACACT | XM_005502842 | 113 |

| R: GAAAACGGCTTCTCTCCAGT | |||

| 18S | F: AGCTCTTTCTCGATTCCGTG | AF173630 | 256 |

| R: GGGTAGGCACAAGCTGAGCC |

1YAP = Yes-associated transcriptional protein, LATS1 = Large tumor suppressor kinase 1, SAV1 = Salvador homology protein 1, STK3 = Serine/threonine kinase 3, TEAD3 = TEA domain transcription factor 3, TEAD4 = TEA domain transcription factor 4, CTGF = Connective tissue growth factor, c-Myc = MYC proto-oncogene, SOX2 = SRY-box transcription factor 2, SNAI2 = Snail family transcriptional repressor.

2F = forward; R = reverse.

Western blot analysis

The tissue samples were thawed and homogenized in precooled RIPA lysis buffer containing benzo sulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and phosphatase inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The protein concentration was determined by Bradford analysis, and 40 µg of sample protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (SDS) gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The polyvinylidene fluoride membrane was blocked with 5% fat-free milk at room temperature for 120 min, followed by incubation with primary antibodies against YAP (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), LATS1 (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), phosphorylated-YAP (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:1000), CTGF (Biorbyt, dilution 1:500), and β-actin (Abcam, dilution 1:1000) overnight at 4 °C. The PVDF membrane was then washed with buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, dilution 1:2,000) at room temperature for 120 min. Finally, enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents were used to visualize the bands, which were scanned by a Bio-Rad scanning densitometer. The intensity of the individual bands was calculated using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously reported by Dong et al. (2007). In brief, the crop sample slices were dewaxed, hydrated, and repaired with 1 × citric acid repair solution for 10 min (at 95 °C), and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide aqueous solution for 10 min. The slices were blocked with 1 × Animal-Free Blocking Solution for 30 min (Cell Signaling Technology), and 200 μL of anti-YAP antibody (1:200; diluted with Antibody Diluent [Cell Signaling Technology]) was added to the slices. Then, 30–100 μL of Boost Detection Reagent (Cell Signaling Technology) was added dropwise to each slice, which were then incubated at room temperature for 30 min in a humidifier. Then, 150 μL of DAB solution (Cell Signaling Technology; DAB Chromogen Concentrate and DAB Diluent were mixed in a ratio of 1:3) was added followed by incubation for 10 min. The slices were then stained with hematoxylin (Cell Signaling Technology) for 15 min, fixed with neutral resin (Cell Signaling Technology), sealed, and evaluated under an optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

EdU cell proliferation assay

Crop cell proliferation was detected using an EdU Cell Proliferation Kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The slides were sealed and evaluated under an optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The data were statistically evaluated using SPSS 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Variables in males or females during breeding were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s post hoc test. Correlation analysis was performed using two-tailed Kendall’s tau-b method. Differences or effects were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Epidermal structure and thickness of pigeon crops

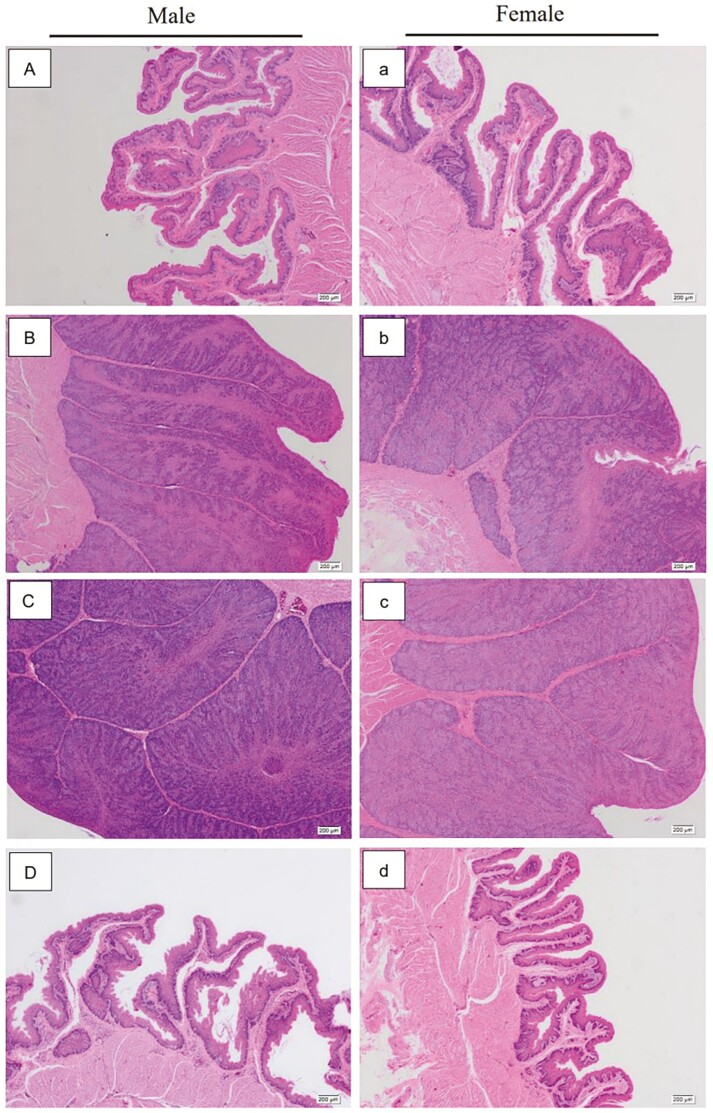

As shown in Figure 1, there were no obvious hyperplasia indications or individual folds on the surface of the crop epithelium at I4 (Figure 1A and a). The thickness of the crop epithelium was significantly increased (P < 0.05) at I17 and R1 (Figure 1B, b, C, and c, Table 2) compared to I4. Moreover, obvious spikes were observed on the crop mumble epithelium, which were filled with proliferating epithelial cells. The crop epithelium of both female and male pigeons has degenerated at R25 (Figure 1D and d, Table 2), which was characterized by a significant increase in the distance between adjacent folds. The length and number of surface spikes, as well as the thickness of the crop epithelium, returned to the I4 level at the end of chick rearing (R25).

Figure 1.

Changes in physiological structure of crop tissue of breeding pigeons in different breeding cycles. The magnification was 4×, A, B, C, and D were the observation results of crop epithelial structure of male pigeons on the incubation day 4 and 17 and chick-rearing day 1 and 25. a, b, c, and d were the observation results of crop epithelial structure of female pigeons on the incubation day 4 and 17 and chick-rearing day 1 and 25.

Table 2.

The epithelial thickness of crop tissue in breeding pigeons

| Item1 | Breeding time point | Thickness of crop epithelium (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||

| Incubation | |||

| I4 | 80.07 ± 7.79b | 59.75 ± 0.75C | |

| I17 | 2008.72 ± 290.01a | 1770.35 ± 201.71B | |

| Chick rearing | |||

| R1 | 2230.03 ± 158.11a | 2352.48 ± 229.34A | |

| R25 | 74.82 ± 7.99b | 59.09 ± 8.04C | |

1) Data are shown as means ± SEM; n = 6. 2The stages included day 4 (I4), 10 (I10), and 17 (I17) of the incubation, day 1 (R1), 7 (R7), 15 (R15), and 25 (R25) of the chick rearing, n = 6.

A–C, a–d Mean values within the same row not sharing a common superscript letter are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Serum PRL levels of pigeons

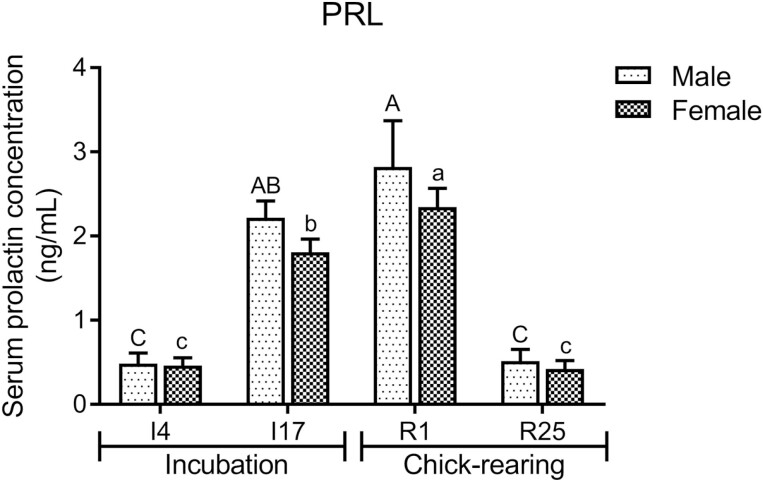

Figure 2 shows that in different breeding periods, the serum PRL levels of female and male pigeons reached their greatest levels at R1, and these levels were significantly greater than those at I4 and R25 (P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Serum PRL levels of pigeons in different breeding stages. The stages included incubation period: I4 and I17; and chick-rearing period: R1 and R25. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6 males and females). Data points with different capital letters (A–C) or lowercase letters (a–c) are significantly different (P < 0.05).

mRNA levels of Hippo pathway-related genes

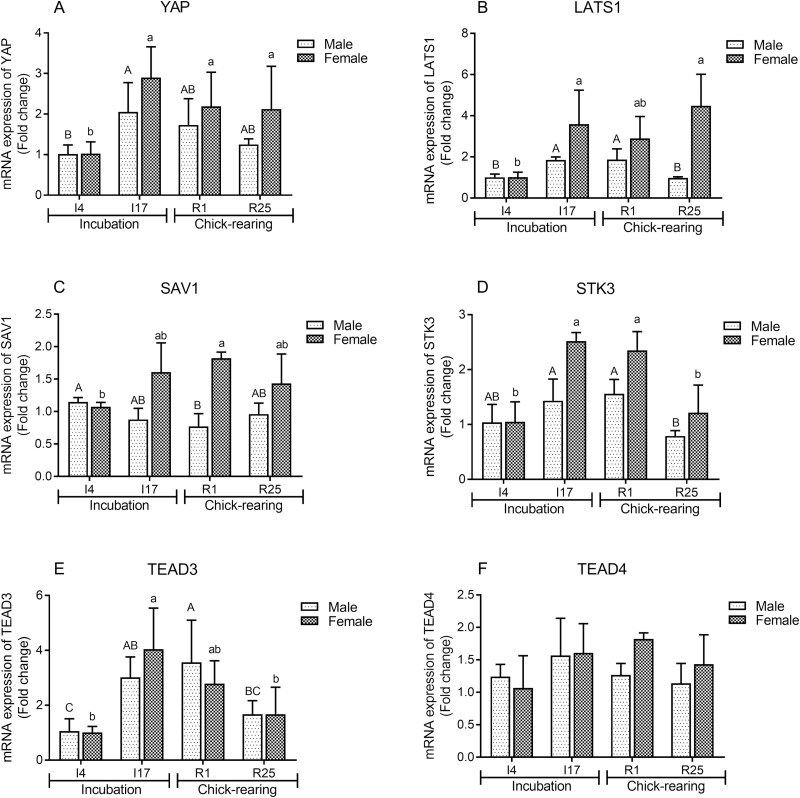

Compared to I4, the YAP gene expression level in crop tissues of male and female pigeons significantly increased at I17 (P < 0.05) but then gradually decreased thereafter (Figure 3). In males, LATS1 gene expression reached the greatest level at I17 and R1 (P < 0.05), whereas LATS1 gene expression was significantly upregulated at I17 and R25 in females (P < 0.05). The expression of SAV1 reached a minimum at I4 but a maximum at R1 in males and females (P < 0.05). The STK3 and TEAD3 mRNA levels in the crop of male and female pigeons were significantly greater at I17 and R1 compared to at I4 and R25 (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in TEAD4 gene expression during different breeding stages. In female crop tissues, the expression level of TEAD4 in R1 was greater than that in I4 (P = 0.053).

Figure 3.

The mRNA expressions of yes-associated transcriptional protein (YAP) (A), large tumor suppressor kinase 1 (LATS1) (B), salvador homology protein 1 (SAV1) (C), serine/threonine kinase 3 (STK3) (D), TEA domain transcription factor 3 (TEAD3) (e) and TEA domain transcription factor 4 (TEAD4) (F) in crop tissues of male and female pigeons during incubation and chick-rearing periods. The stages included incubation period: incubation day 4 (I4) and 17 (I17); chick-rearing period: rearing day 1 (R1) and 25 (R25). Values are means ± SEM (n = 6 pigeons per day for each sex). Bars with different capital letters (A, B, C) are significantly different in male pigeons (P < 0.05). Bars with different lowercases (a, b) are significantly different in female pigeons (P < 0.05).

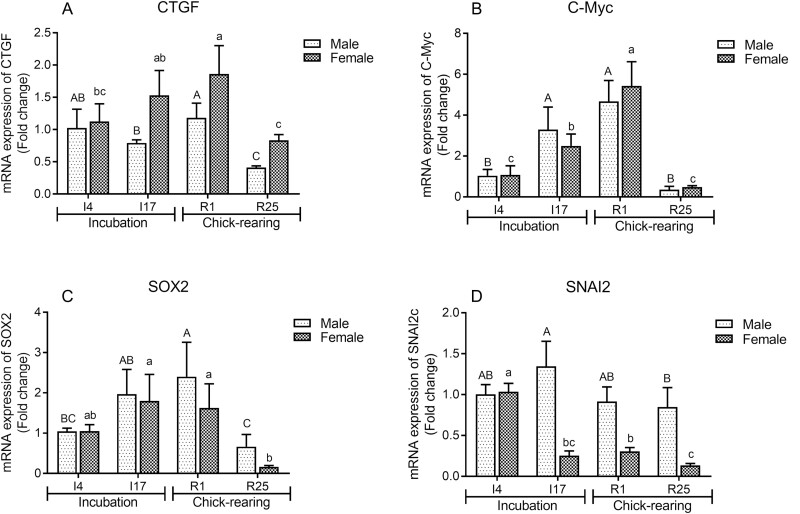

The gene expression levels of other downstream transcription factors of the Hippo pathway are shown in Figure 4. In female and male crop tissues, the mRNA levels of CTGF and c-Myc reached a maximum at R1, and the gene expression of SOX2 was the greatest at I17 and R1 (P < 0.05). After the I4 period, the gene expression of SNAI2 in the crop of female pigeons was significantly downregulated, while the maximum SNAI2 expression was at I17 in male pigeons (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

The mRNA expressions of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (A), MYC proto-oncogene (c-Myc) (B), SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2) (C) and snail family transcriptional repressor 2 (SNAI2) (d) in crop tissues of male and female pigeons during incubation and chick-rearing periods. The stages included incubation period: incubation day 4 (I4) and 17 (I17); chick-rearing period: rearing day 1 (R1) and 25 (R25). Values are means ± SEM (n = 6 pigeons per day for each sex). Bars with different capital letters (A, B, C) are significantly different in male pigeons (P < 0.05). Bars with different lowercases (a, b, c) are significantly different in female pigeons (P < 0.05).

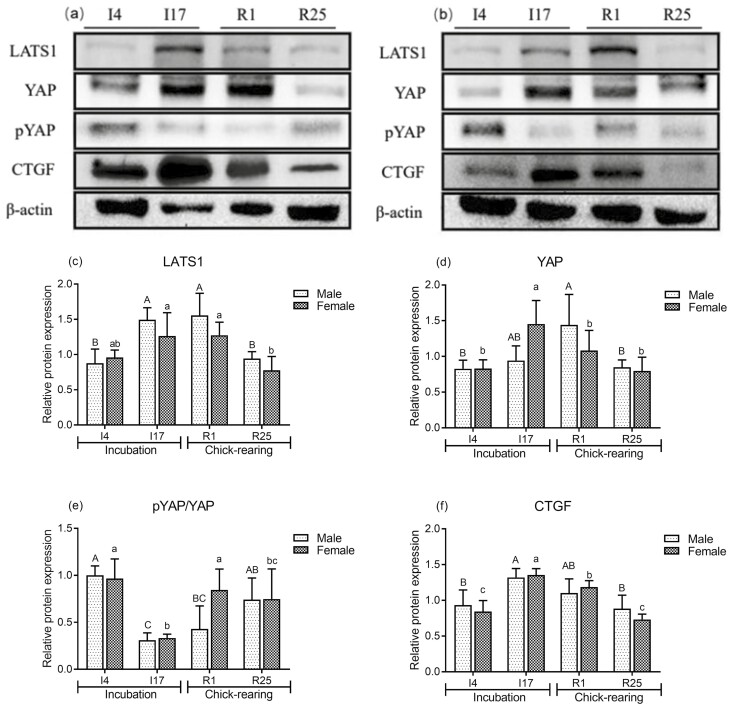

Expression levels of Hippo signaling pathway-related proteins

To investigate whether the Hippo signaling pathway is involved in crop tissue cell proliferation, the protein levels of LATS1, YAP, CTGF, and pYAP in crop tissues of male and female pigeons were detected by western blot analysis. Compared to I4 and R25, the protein expression levels of LATS1, YAP, and CTGF in the crop of male (Figure 5A, C, D, and F) and female (Figure 5B, C, D, and F) pigeons were significantly increased at I17 and R1. In contrast, pYAP expression levels in the crop tissues of both male and female pigeons were significantly decreased at I17 (Figure 5A, B, and E).

Figure 5.

Representative western blot and densitometric analysis of Hippo signaling pathway-related proteins in crop tissues of male (A) and female pigeons (B) during incubation and chick-rearing periods. Expression levels of large tumor suppressor kinase 1 (LATS1) (C), yes-associated transcriptional protein (YAP) (D), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (F) are normalized to β‐actin levels. Expression levels of phosphorylated YAP (pYAP) (E) are normalized to YAP levels. The stages included incubation period: incubation day 4 (I4) and 17 (I17); chick-rearing period: rearing day 1 (R1) and 25 (R25). Values are means ± SEM (n = 6 pigeons per day for each sex). Bars with different capital letters (A, B, C) are significantly different in male pigeons (P < 0.05). Bars with different lowercases (a, b, c) are significantly different in female pigeons (P < 0.05).

Correlation analysis of Hippo pathway gene expression levels, Hippo pathway protein levels, and crop epidermal thickness

The mRNA expression levels of LATS1, STK3, TEAD3, c-Myc, and SOX2 were significantly positively correlated with crop epidermal thickness (Table 3, P < 0.05). The thickness of the female crop epidermis was significantly positively correlated with the expression of the STK3 gene (Table 3, P < 0.05) and positively correlated with the change in the CTGF gene (Table 3, P = 0.063). The protein expression levels of YAP in the crop tissues of male and female pigeons were significantly positively correlated with the variation in crop epithelial thickness (Table 3, P < 0.05). There was a positive correlation between CTGF protein levels and epithelial thickness in female pigeon tissues (Table 3, P = 0.061). The level of pYAP protein was significantly negatively correlated with the thickness of pigeon crop epithelium in males and females (Table 3, P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between Hippo pathway-related genes and proteins levels and superficial thickness in crop tissue of pigeons1

| Item | Name2 | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation index | P-value | Correlation index | P-value | ||

| Genes | YAP | 0.861 | 0.141 | 0.691 | 0.309 |

| LATS1 | 0.981 | 0.019* | 0.117 | 0.823 | |

| SAV1 | −0.872 | 0.128 | 0.859 | 0.141 | |

| STK3 | 0.957 | 0.043* | 0.982 | 0.018* | |

| TEAD3 | 0.976 | 0.024* | 0.868 | 0.132 | |

| TEAD4 | 0.561 | 0.439 | 0.117 | 0.143 | |

| CTGF | 0.549 | 0.451 | 0.937 | 0.063 | |

| c-Myc | 0.987 | 0.013* | 0.872 | 0.128 | |

| SOX2 | 0.982 | 0.019* | 0.857 | 0.143 | |

| SNAI2 | 0.364 | 0.636 | −0.425 | 0.575 | |

| Proteins | YAP | 0. 988 | 0.012* | 0.951 | 0.049* |

| LATS1 | 0.835 | 0.065 | 0.824 | 0.135 | |

| CTGF | 0.777 | 0.223 | 0.937 | 0.061 | |

| pYAP | −0.877 | 0.023* | −0.819 | 0.031* | |

1Values of the correlation coefficients were derived from the Pearson product moment correlation method.

2YAP = Yes-associated transcriptional protein, LATS1 = Large tumor suppressor kinase 1, SAV1 = Salvador homology protein 1, STK3 = Serine/threonine kinase 3, TEAD3 = TEA domain transcription factor 3, TEAD4 = TEA domain transcription factor 4, CTGF = Connective tissue growth factor, c-Myc = MYC proto-oncogene, SOX2 = SRY-box transcription factor 2, SNAI2 = Snail family transcriptional repressor, pYAP = phosphorylated-YAP.

*Mean values are significantly different (P < 0.05), n = 6.

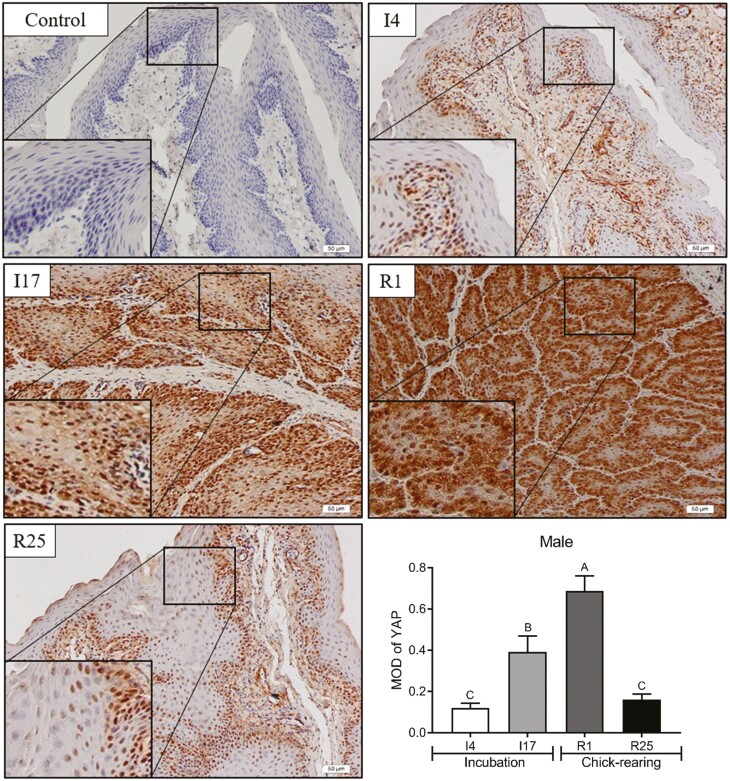

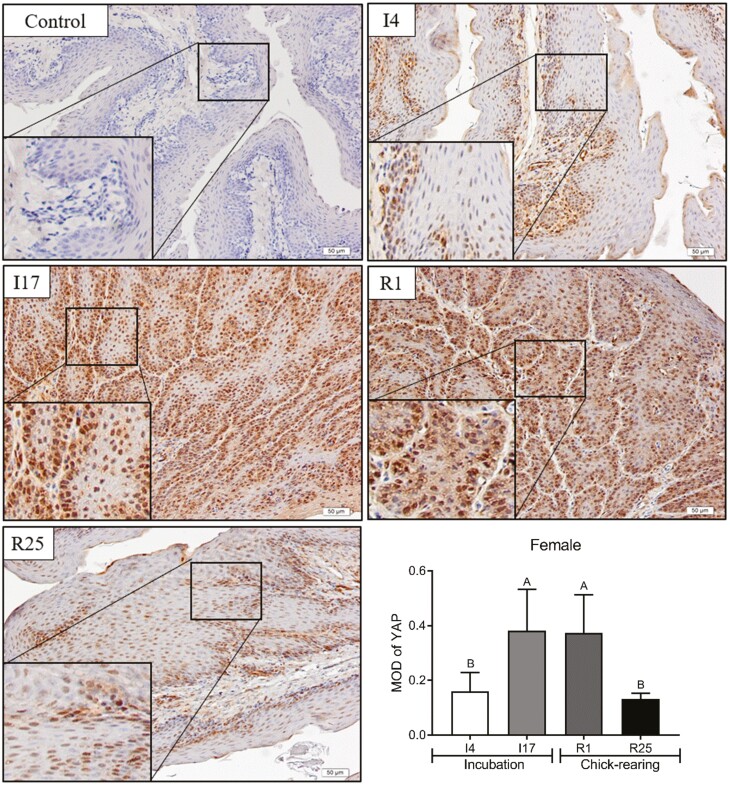

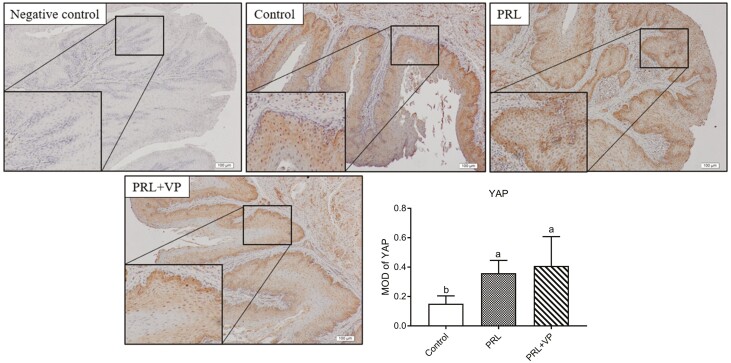

Cellular localization of YAP protein in pigeon crops

In the present study, immunohistochemistry was used to explore the cellular localization of YAP to determine whether YAP plays a biological role in the proliferation of pigeon crops. Compared to I4 and R25, the YAP protein was significantly enriched in the crop epithelial cells of male pigeons at I17 and R1 (Figure 6, P < 0.05). Similar to male pigeons, the enrichment of YAP protein in the crop epithelial cells of female pigeons was significantly increased at I17 and R1 (Figure 7, P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Cytoplasmic localization of YAP in crop tissue of male pigeons during breeding period. The magnification was 20×. Control represented the negative control. The stages included incubation period: incubation day 4 (I4) and 17 (I17); chick-rearing period: rearing day 1 (R1) and 25 (R25). Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). Bars with the different capital letters (A–C) are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Cytoplasmic localization of YAP in crop tissue of female pigeons during breeding period. The magnification was 20×. Control represented the negative control. The stages included incubation period: incubation day 4 (I4) and 17 (I17); chick-rearing period: rearing day 1 (R1) and 25 (R25). Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). Bars with the different capital letters (A–B) are significantly different (P < 0.05).

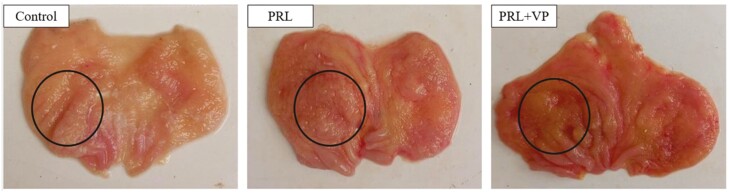

Effect of subcutaneous injection of PRL and VP on the cell proliferation of pigeon crops

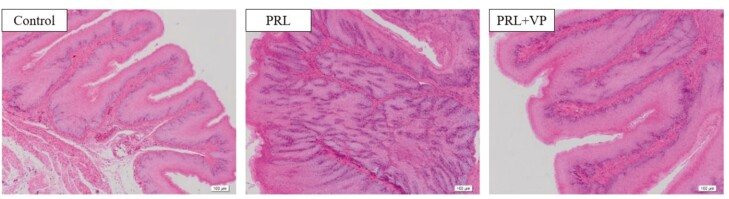

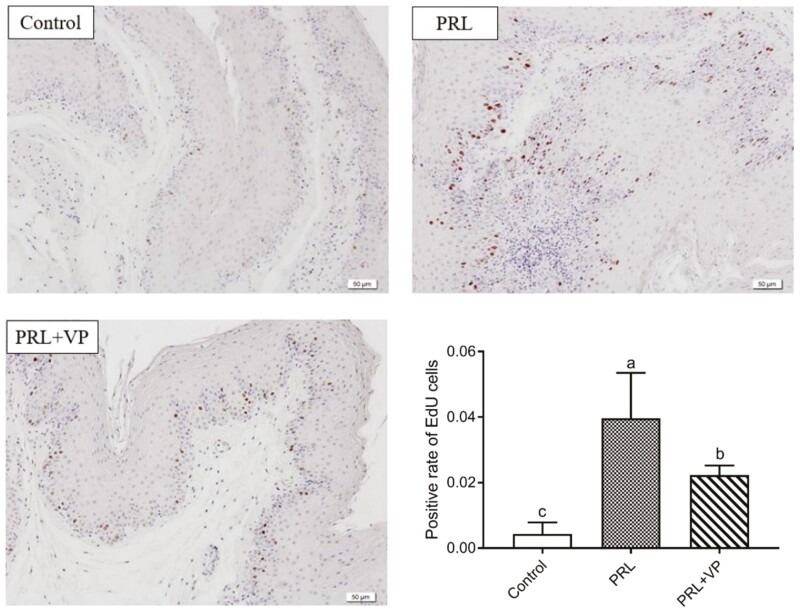

Compared to the control group, crop tissue proliferation was more obvious after PRL injection in the left crop of pigeons (Figure 8; indicated by black circle). In addition, pigeon crop tissue showed signs of hyperplasia after injection of VP, but it was not obvious compared to the PRL group. HE staining showed that the thickness of the crop epithelium in the PRL group was significantly greater than that in the control group and PRL + VP group (Figure 9). The relative number of proliferating crop tissue cells in the PRL and PRL + VP groups was significantly greater than that of the control group, and the positive rate of EdU cells was significantly increased (P < 0.05), with the greatest rate in the PRL group (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Morphological differences of pigeon crops in control group, prolactin (PRL) injection group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP) group. The control group was injected with 0.9 % sterile saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), and EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, 2 mg per kg body weight every day) was injected after that. The pigeons of PRL injection group were injected with PRL (10 μg per kg body weight every day), and EdU was injected later. The PRL+VP group pigeons were injected with VP (2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, and then injected with EdU. Injection was carried out at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d.

Figure 9.

Observation on the structure of pigeon crops epithelium in control group, prolactin (PRL) injection group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP). The magnification was 10×. The control group was injected with 0.9 % sterile saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), and EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, 2 mg per kg body weight every day) was injected after that. The pigeons of PRL injection group were injected with PRL (10 μg per kg body weight every day), and EdU was injected later. The PRL+VP group pigeons were injected with VP (2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, and then injected with EdU. Injection was carried out at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d.

Figure 10.

Detection of EdU cell proliferation in pigeon crops in control group, prolactin (PRL) injection group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP). The magnification was 20×. The control group was injected with 0.9 % sterile saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), and EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, 2 mg per kg body weight every day) was injected after that. The pigeons of PRL injection group were injected with PRL (10 μg per kg body weight every day), and EdU was injected later. The PRL+VP group pigeons were injected with VP (2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, and then injected with EdU. Injection was carried out at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d. Bars with the different lowercase letters (A–C) are significantly different (P < 0.05), n = 6.

Effects of subcutaneous injection of PRL and VP on Hippo pathway-related genes

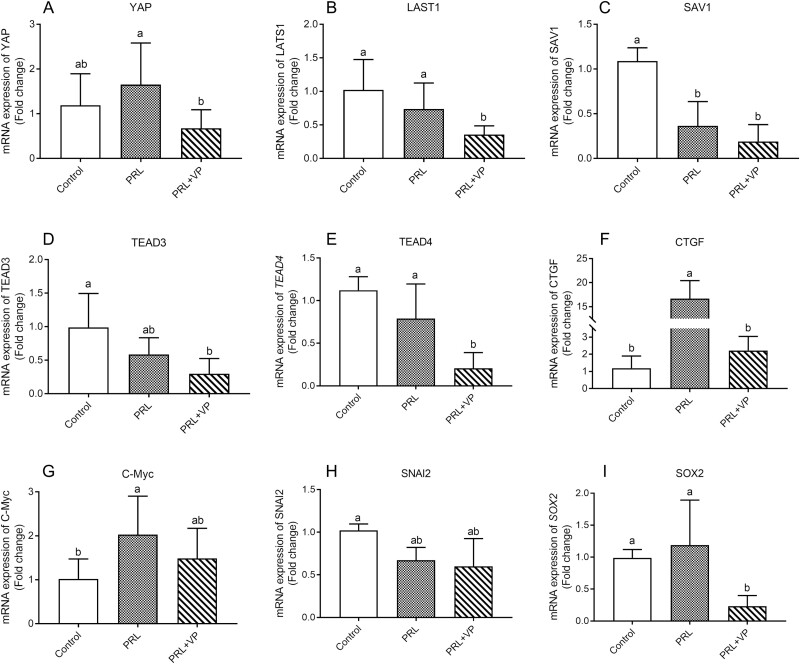

The mRNA expression levels of YAP, SOX2, CTGF, and c-Myc in the PRL group were greater than those in the control and PRL + VP groups (Figure 11, P < 0.05). Of these, CTGF reached a significant level (P < 0.01), with expression levels approximately 15 and 7 times greater than the control group and PRL + VP group, respectively. In addition, the expression levels of the SAV1, LATS1, TEAD3, and TEAD4 genes in the control group were greater than those in the PRL and PRL + VP groups.

Figure 11.

mRNA levels of Hippo pathway-related genes in pigeon crops in control group, prolactin (PRL) injection group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP). The control group was injected with 0.9 % sterile saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), and EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, 2 mg per kg body weight every day) was injected after that. The pigeons of PRL injection group were injected with PRL (10 μg per kg body weight every day), and EdU was injected later. The PRL+VP group pigeons were injected with VP (2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, and then injected with EdU. Injection was carried out at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d. Bars with the different lowercase letters (A–B) are significantly different (P < 0.05), n = 6.

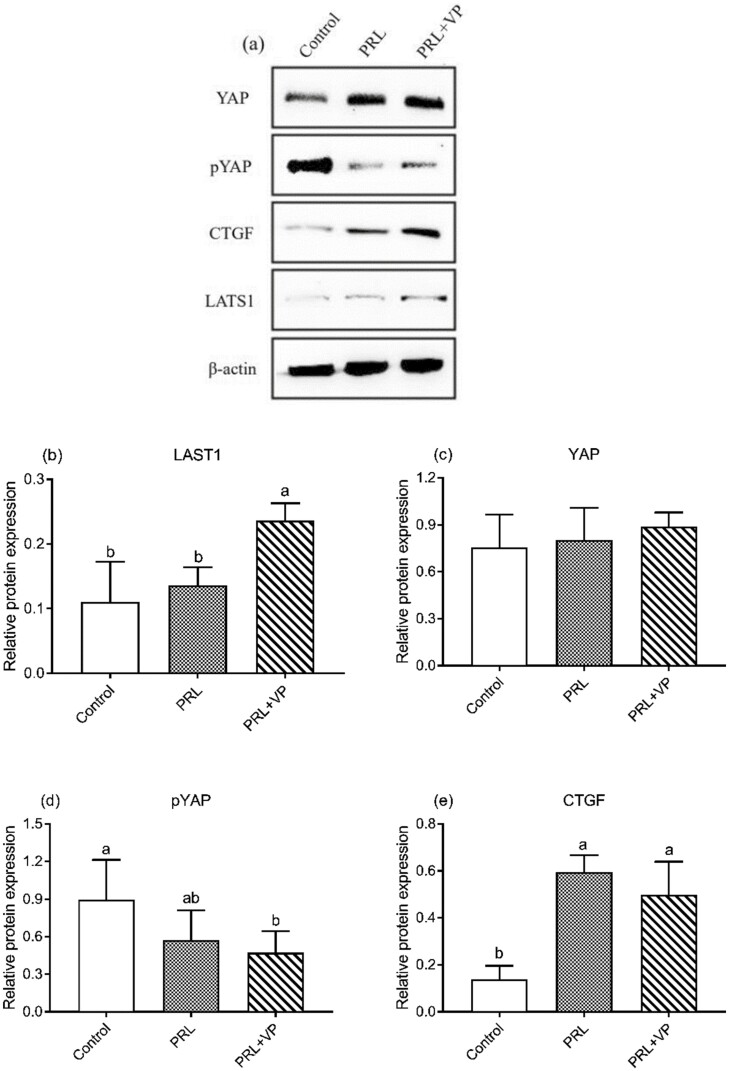

Compared to the control group, the total YAP protein levels in the PRL and PRL + VP groups were not significantly upregulated, whereas the YAP phosphorylation levels were significantly decreased in the PRL and PRL + VP groups (Figure 12). At the same time, the CTGF protein expression levels in the PRL and PRL + VP groups were significantly upregulated compared to the control group, and the LATS1 protein expression level was significantly upregulated in the PRL + VP group compared to the control group. Moreover, as shown in Figure 13, the YAP protein in the PRL and PRL + VP groups was mostly enriched in the nucleus of the pigeon crop epithelium compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

Figure 12.

Expression of Hippo pathway protein in pigeon crop tissues in control group, prolactin (PRL) injection group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP). The control group was injected with 0.9 % sterile saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), and EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, 2 mg per kg body weight every day) was injected after that. The pigeons of PRL injection group were injected with PRL (10 μg per kg body weight every day), and EdU was injected later. The PRL+VP group pigeons were injected with VP (2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, and then injected with EdU. Injection was carried out at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d. Bars with the different lowercase letters (A–B) are significantly different (P < 0.05), n = 6.

Figure 13.

Cytoplasmic localization of YAP in crop tissue of pigeons in control group, prolactin (PRL) injection group, and PRL+ verteporfin (VP). The control group was injected with 0.9 % sterile saline (200 μL per kg body weight every day), and EdU (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine, 2 mg per kg body weight every day) was injected after that. The pigeons of PRL injection group were injected with PRL (10 μg per kg body weight every day), and EdU was injected later. The PRL+VP group pigeons were injected with VP (2.5 mg per kg body weight every day) after injection of PRL, and then injected with EdU. Injection was carried out at 8:00 a.m. every day for 6 d. Bars with the different lowercase letters (A–B) are significantly different (P < 0.05), n = 6.

Discussion

Cell proliferation is an important basis for the growth, development, reproduction, inheritance, and maintenance of intracellular homeostasis of organisms, which is important in pigeon crop tissues (Harvey and Tapon 2007; Kango-Singh and Singh 2009). We previously reported that significant cell proliferation occurs in the crop mumble epithelium of breeding pigeons due to the need for pigeon milk formation during the lactation, resulting in significant increases in the thickness and relative weight of the crop mumble (Hu et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2020). Therefore, exploring the proliferation mechanism of pigeon crop epithelial cells will help to better understand the formation of crop milk.

After the beginning of the incubation period, the present study demonstrated that the crop structure and thickness of male and female pigeons greatly changed, and peg structures were observed on the crop epidermis. These changes began on day 3 of incubation and became more obvious on day 10 of incubation, which agreed with previous studies (Davies 1939; Contzler et al., 2005; Gillespie et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2016). In the present study, the static state of pigeon crops was observed during the nonlactation period (I4 and R25). At this time, the crop epithelial structure of male and female pigeons did not significantly proliferate. However, with the progress of the reproductive cycle, the tissue of the crop mucosa changed. The thickness of the crop epithelium reached the maximum value at I17 and R1, and the epithelium showed obvious hyperplasia. The changes in crop morphology have been confirmed to be related to the high level of serum PRL (Xie et al., 2018).

PRL is a hormone synthesized and secreted by the anterior pituitary, and it mainly mediates mammalian mammary gland development, lactation, and other processes, as well as plays a direct role in the proliferation and division of biological cells (Freeman et al., 2000; Carretero et al., 2003; Ao et al., 2022). In the present study, a greater concentration of serum PRL was found during the lactation period compared to the nonbreeding period. Similarly, Dong et al. (2013) and Hu et al. (2016) observed a significant increase in serum PRL levels and PRL receptor mRNA expression in pigeon crops during the lactation period. Moreover, it has been reported that the injection of exogenous PRL significantly increases the relative weight, thickness, total DNA, and total RNA of pigeon crops (Horseman and Buntin 1995; Accorsi et al., 2002; Buntin and Buntin 2014; Chen et al., 2020). In the present study, 6 d after PRL subcutaneous injection, obvious tissue hyperplasia was observed at the injection site. HE staining showed that the epithelium of the pigeon crop after PRL injection was significantly thickened, and the nail process structure was rapidly extended and bifurcated with proliferating cells stacked between the bifurcations. Additionally, the EdU-positive rate of the PRL group was significantly greater than that of the control group. Thus, these results indicated that PRL promotes the proliferation of pigeon crop epithelial cells.

PRL promotes cell division mainly by inhibiting cell apoptosis and shortening the cell cycle, and it has a certain role in promoting the growth of breast cells and various tumor cells, which is similar to the biological role of the Hippo pathway (Ma et al., 2019; Driskill and Pan 2021; Fu et al., 2022; He et al., 2022). The Hippo pathway has been shown to play an important role in the development of various tissues and organs, but it remains unknown whether it is also involved in the proliferation of pigeon crop epithelial cells (Yan et al., 2016; Barcus et al., 2017; Cao et al., 2021). In the present study, the YAP gene expression levels peaked at I17 and R1, and the total protein level of YAP was consistent with the mRNA level. The injection of exogenous PRL induced a decrease in pYAP levels and promoted its enrichment in the nucleus of crop epithelial cells, which suggested that YAP may play an important role in crop proliferation. Similar to the present results, Nie et al. (2021) demonstrated that the addition of 0.5 μg of PRL to AsPC-1 and BxPC-3 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells decreases the pYAP level and promotes the accumulation of YAP in the nucleus. Additional studies have reported that PRL binds to the PRL receptor and induces the expression of NIMA-related kinase 9, which ultimately activates YAP and promotes its enrichment in the nucleus, suggesting a potential mechanism by which PRL activates YAP in pigeon crops. In addition, PRL promotes the proliferation of prolactinoma MMQ cells through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway has a direct regulatory relationship with the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway (Konsage et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2014). The Y3-binding site of the YAP gene sequence binds to β-catenin and promotes the transcription of YAP (Konsavage et al., 2012). Gillespie et al. (2011) reported that the expression of the β-catenin gene in the ‘lactating’ pigeon crop is significantly greater than that in the non-lactating pigeon crop, suggesting that YAP may be bound by β-catenin to promote the proliferation of the pigeon crop epithelium. These results suggest that YAP may be a key factor in the proliferation of pigeon crop epithelium.

In the present study, the gene and protein levels of LATS1 in pigeon crop tissue were significantly upregulated at I17 and R1. However, this upregulation contradicted the upregulation of YAP protein. Of note, several studies have noted that there are organizational differences in the regulatory relationship between LATS1 and YAP. For instance, Zhang et al. (2019) found a significant negative correlation between the activities of LATS1 and YAP in the skeletal muscle of Hu sheep. In contrast, in muscle tissue (such as the Longissimus), the expression level of LATS1 maintains the activity of YAP, and the positive correlation between the two proteins increases with the age of the sheep (Sun et al., 2012). Hence, the relationship between LATS1 and YAP varies in different animal tissues (Zheng and Pan 2019; Jin et al., 2023). In addition, LATS1 also induces the expression of the Bax and Caspase 3 apoptosis genes in a manner independent of the Hippo pathway to promote the process of cell apoptosis. Considering that the apoptosis activity is more obvious during the formation of pigeon milk, this may be one of the reasons for the high expression of LATS1 (Shen et al., 2016). In addition, the present study demonstrated that injection of exogenous PRL inhibited the expression of LATS1 and SAV1 in pigeon crops, indicating that PRL inhibits the expression of hippo pathway upstream factors. Recently, studies have confirmed that LATS2, a homolog of LATS1, is a target gene of microRNA-135b. Under the stimulation of PRL, CpG-DNA upstream of microRNA-135b in goat mammary epithelial cells is methylated, thereby inhibiting the expression of LATS2. The same mechanism may exist between PRL and LATS1, suggesting a potential mechanism by which PRL regulates the Hippo pathway in pigeon crops (Chen et al., 2018).

CTGF was initially found to induce the proliferation, division, and migration of fibroblasts as well as extracellular matrix formation (Liu et al., 2014). Recent studies have shown that CTGF is a target gene for YAP and TEADs, which can be induced by high expression of YAP (Zhao et al., 2008). Knocking out YAP results in a decrease in CTGF mRNA and protein levels (Zhao et al., 2008). In the present study, the mRNA and protein levels of CTGF in the crop tissue of male and female pigeons were significantly increased at I17 and R1. Additionally, the injection test confirmed that the increase in CTGF expression level was derived from the induction of PRL, indicating an interaction between CTGF and PRL. Studies have shown that the addition of CTGF alone stimulates proliferation of the MAC-T bovine mammary epithelial cell line and enhances the expression of PRL receptor mRNA and protein levels (Li et al., 2017). At the same time, PRL promotes the proliferation and differentiation of scar fibroblasts induced by CTGF, indicating that CTGF is an important target protein for the biological role of PRL (Zhou et al., 2008). In addition, the glycolytic pathway of pigeon crop tissue is activated during the formation of crop milk (Zhu et al., 2023a). Interestingly, there is an interaction between CTGF and GLUTs; CTGF induces the expression of GLUT3 and enhances glycolysis, thereby regulating cell growth and viability, suggesting another important role of CTGF in pigeon crops (Kim et al., 2021).

c-Myc is a widely conserved transcriptional regulator involved in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Kaur and Cole 2013; Stine et al., 2015). As the main regulatory checkpoint in cell proliferation, the transition of the cell cycle from G1 phase to S phase is significantly activated by c-Myc expression (Zhao et al, 2015). Previous studies have shown that YAP is a transcription stimulator of c-Myc, and the upregulation of YAP induces c-Myc gene and protein expression levels (Xiao et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017). In the present study, the mRNA level of c-Myc rapidly increased at the peak period of pigeon crop proliferation (I17 and R1), and its expression pattern was consistent with that of YAP. The injection experiment showed that PRL increased the mRNA level of c-Myc in pigeon crops, which was consistent with the results of Fresno-Vara et al. (2001), who noted that PRL promotes the proliferation of w53 lymphoid cells by inducing c-Myc expression. This activation depends on the activity of Src kinase and PI3K. In addition, protein kinase B also upregulates the expression level of c-Myc by inactivating GSK3, suggesting that the same mechanism may exist in pigeon crops (Domínguez-Cáceres et al. 2004). These results suggest that c-Myc may be a key gene affecting pigeon crop proliferation.

The SOX2 transcription factor is one of the necessary factors for mammalian embryonic development, and it is also an important downstream transcription factor in the Hippo pathway (Novak et al., 2020). In the present study, the gene expression level of SOX2 in pigeon crop tissues was significantly increased in I17 and R1, and SOX2 gene expression was also induced by injection of exogenous PRL. Botermann et al. (2021) noted that activation of Hedgehog signaling in the pituitary gland induces the secretion of PRL, which promotes the proliferation of Sox2+ cells, suggesting an interaction between SOX2 and PRL. This mechanism may exist in pigeon crops, but further research is needed. VP is a YAP blocker that blocks the interaction between YAP and TEADs, which inhibits the expression of downstream target genes, ultimately inhibiting cell proliferation (Barrette et al., 2022). Studies have shown that injection of VP (10 mg per kg body weight every day) inhibits the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by inhibiting the expression of SOX2 and CTGF, respectively (Kang et al., 2018; Guimei et al., 2020). It has previously been reported that intraperitoneal injection of VP (50 mg) significantly reduces the proliferation ability of mouse spleen leukemia cells and osteosarcoma cells (Morishita et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2021). Similar to the above results, the present results indicated that continued injection of VP on the basis of PRL injection may inhibit PRL-induced crop epithelial cell proliferation and reduce the mRNA levels of CTGF, TEAD3, TEAD4, SOX2, and c-Myc. Thus, these results suggest that PRL regulates the proliferation of pigeon crop tissues by affecting Hippo pathway-related molecules.

Conclusion

There is a certain correlation between the Hippo pathway and crop epithelial proliferation. During the proliferation of pigeon crops, the expression of YAP, c-Myc, SOX2, TEAD3, and CTGF were significantly upregulated. Subcutaneous injection of PRL promoted the proliferation of crop epithelial cells and induced the upregulation of YAP mRNA levels. The high expression of CTGF depends on PRL, suggesting that PRL may be involved in pigeon crop tissue proliferation by influencing YAP and CTGF.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members in the school for their generous technical suggestions. The research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Greater Education Institutions of China (23KJA23001) and the Key R&D Plan Project of Huai’an City (Rural Revitalization) (HAN202203).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- c-Myc

MYC proto-oncogene

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- ECL

enhanced chemiluminescence

- EdU

5-ethynyl-2’ -deoxy uridine

- LATS1

large tumor suppressor kinase 1

- MOB1

MOB kinase activator 1

- PRL

prolactin

- SAV1

salvador homology protein 1

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SNAI2

snail family transcriptional repressor 2

- SOX2

SRY-box transcription factor 2

- STK3

serine/threonine kinase 3

- TEAD3

TEA domain transcription factor 3

- TEAD4

TEA domain transcription factor 4

- VP

verteporfin

- YAP

yes-associated transcriptional protein

Contributor Information

Jianguo Zhu, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Regional Modern Agriculture & Environmental Protection, Huaiyin Normal University, Huaian 223300, P.R.China; College of Animal Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, P.R.China.

Xingyi Teng, College of Animal Science and Technology, Qingdao Agricultural University, Qingdao 266000, P.R.China.

Liuxiong Wang, College of Animal Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, P.R.China.

Mingde Zheng, College of Animal Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, P.R.China.

Yu Meng, College of Animal Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, P.R.China.

Tingwu Liu, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Regional Modern Agriculture & Environmental Protection, Huaiyin Normal University, Huaian 223300, P.R.China.

Ying Liu, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Regional Modern Agriculture & Environmental Protection, Huaiyin Normal University, Huaian 223300, P.R.China.

Haixia Huan, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Regional Modern Agriculture & Environmental Protection, Huaiyin Normal University, Huaian 223300, P.R.China.

Daoqing Gong, College of Animal Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, P.R.China.

Peng Xie, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Regional Modern Agriculture & Environmental Protection, Huaiyin Normal University, Huaian 223300, P.R.China.

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Department of Scientific Research, Institute of Animal Science, Yangzhou University.

Literature Cited

- Accorsi, P. A., Pacioni B., Pezzi C., Forni M., Flint D. J., and Seren E... 2002. Role of prolactin, growth hormone and insulin like growth factor 1 in mammary gland involution in the dairy cow. J. Dairy Sci. 85:507–513. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74102-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T. R., Pitts D. S., and Nicoll C. S... 1984. Prolactin’s mitogenic action on the pigeon crop-sac mucosal epithelium involves direct and indirect mechanisms. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 54:236–246. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(84)90177-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao, J. Z., Ma, R.Li, S.Zhang, X.Gao, M. Zhang. 2022. Phospho-Tudor-SN coordinates with STAT5 to regulate prolactin-stimulated milk protein synthesis and proliferation of bovine mammary epithelial cells. Anim. Biotechnol. 33:1161–1169. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2021.1879824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcus, C. E., O’Leary K. A., Brockman J. L., Rugowski D. E., Liu Y., Garcia N., Yu M., Keely P. J., Eliceiri K. W., and Schuler L. A... 2017. Elevated collagen-I augments tumor progressive signals, intravasation and metastasis of prolactin-induced estrogen receptor alpha positive mammary tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res. BCR. 19:9. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0801-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrette, A. M., Ronk H., Joshi T., Mussa Z., Mehrotra M., Bouras A., Nudelman G., Jesu Raj J. G., Bozec D., Lam W.,. et al. 2022. Anti-invasive efficacy and survival benefit of the YAP-TEAD inhibitor verteporfin in preclinical glioblastoma models. Neuro. Oncol. 24:694–707. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharathi, L., Shenoy K. B., and Hegde S. N... 1997. Biochemical differences between crop tissue and crop milk of pigeons (Columba livia). Comp. Biochem Physiol. 116:51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(96)00116-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botermann, D. S., Brandes N., Frommhold A., Heß I., Wolff A., Zibat A., Hahn H., Buslei R., and Uhmann A... 2021. Hedgehog signaling in endocrine and folliculo-stellate cells of the adult pituitary. J. Endocrinol. 248:303–316. doi: 10.1530/JOE-20-0388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntin, J. D., and Buntin L... 2014. Increased STAT5 signalling in the ring dove brain in response to prolactin administration and spontaneous elevations in prolactin during the breeding cycle. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 200:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L., Gao H., Li P., Gui S., and Zhang Y... 2014. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in the antitumor effect of fulvestrant on rat prolactinoma MMQ cells. Tumour Biol. 35:5121–5127. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1571-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y., Feng Z., He X., Zhang X., Xing B., Wu Y., Hojnacki T., Katona B. W., Ma J., Zhan X.,. et al. 2021. Prolactin-regulated Pbk is involved in pregnancy-induced β-cell proliferation in mice. J. Endocrinol. 252:107–123. doi: 10.1530/JOE-21-0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, R. H., and James C. M... 1931. Synthesis of adequate protein in the glands of the pigeon crop. Am. J. Physiol. 97:227–231. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1931.97.1.227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carretero, J., Rubio M., Blanco E., Burks D. J., Torres J. L., Hernández E., Bodego P., Riesco J. M., Juanes J. A., and Vázquez R... 2003. Variations in the cellular proliferation of prolactin cells from late pregnancy to lactation in rats. Ann. Anat. 185:97–101. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(03)80068-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., Gu W., Wang Q., Fu X., Wang Y., Xu X., and Wen Y... 2017. C-MYC and BCL-2 mediate YAP-regulated tumorigenesis in OSCC. Oncotarget 9:668–679. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z., Luo J., Zhang C., Ma Y., Sun S., Zhang T., and Loor J. J... 2018. Mechanism of prolactin inhibition of miR-135b via methylation in goat mammary epithelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 233:651–662. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. J., Pan N. X., Wang X. Q., Yan H. C., and Gao C. Q... 2020. Methionine promotes crop milk protein synthesis through the JAK2-STAT5 signaling during lactation of domestic pigeons (Columba livia). Food Funct. 11:10786–10798. doi: 10.1039/d0fo02257h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contzler, R., Favre B., Huber M., and Hohl D... 2005. Cornulin, a new member of the “fused gene” family, is expressed during epidermal differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124:990–997. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23694.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, W. L. 1939. The composition of the crop milk of pigeons. Biochem. J. 33:898–901. doi: 10.1042/bj0330898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re, D. P., Yang Y., Nakano N., Cho J., Zhai P., Yamamoto T., Zhang N., Yabuta N., Nojima H., Pan D.,. et al. 2013. Yes-associated protein isoform 1 (Yap1) promotes cardiomyocyte survival and growth to protect against myocardial ischemic injury. J. Biol. Chem. 288:3977–3988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Q., Guo T., Zhou X., Xi Y., Yang X., and Ge W... 2016. Cross-Talk between mitochondrial fusion and the Hippo pathway in controlling cell proliferation during drosophila development. Genetics 203:1777–1788. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.186445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, F., Wu Z., Xu M., and Xia P... 2022. YAP Activates STAT3 signalling to promote colonic epithelial cell proliferation in DSS-Induced colitis and colitis associated cancer. J. Inflam. Res. 15:5471–5482. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S377077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H., Lin Y., Zhang T., Chen L., Zhang G., Wang J., Xie K., and Dai G... 2021. Transcriptome analysis of differentially expressed mRNA related to pigeon muscle development. Animals (Basel). 11:2311. doi: 10.3390/ani11082311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Cáceres, M. A., García-Martínez J. M., Calcabrini A., González L., Porque P. G., León J., and Martín-Pérez J... 2004. Prolactin induces c-Myc expression and cell survival through activation of Src/Akt pathway in lymphoid cells. Oncogene 23:7378–7390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J., Feldmann G., Huang J., Wu S., Zhang N., Comerford S. A., Gayyed M. F., Anders R. A., Maitra A., and Pan D... 2007. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 130:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X. Y., Zhang M., Jia Y. X., and Zou X. T... 2013. Physiological and hormonal aspects in female domestic pigeons (Columba livia) associated with breeding stage and experience. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl) 97:861–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2012.01331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskill, J. H., and Pan D... 2021. The Hippo pathway in liver homeostasis and pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 16:299–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-030420-105050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. E., Kanyicska B., Lerant A., and Nagy G... 2000. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol. Rev. 80:1523–1631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresno Vara, J. A., Cáceres M. A., Silva A., and Martín-Pérez J... 2001. Src family kinases are required for prolactin induction of cell proliferation. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2171–2183. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M., Hu Y., Lan T., Guan K. L., Luo T., and Luo M... 2022. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7:376. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01191-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, M. J., Haring V. R., McColl K. A., Monaghan P., Donald J. A., Nicholas K. R., Moore R. J., and Crowley T. M... 2011. Histological and global gene expression analysis of the ‘lactating’ pigeon crop. BMC Genomics 12:452. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, M. J., Crowley T. M., Haring V. R., Wilson S. L., Harper J. A., Payne J. S., Green D., Monaghan P., Stanley D., Donald J. A.,. et al. 2013. Transcriptome analysis of pigeon milk production—role of cornification and triglyceride synthesis genes. BMC Genomics 14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimei, M., Alrouh S., Saber-Ayad M., Hafezi S. A., Vinod A., Rawat S., Wardeh Y., Bakkour T. M., and El-Serafi A. T... 2020. Inhibition of yes-associated protein-1 (YAP1) enhances the response of invasive breast cancer cells to the standard therapy. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press) 12:189–199. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S268926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, K., and Tapon N... 2007. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway - an emerging tumour-suppressor network. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7:182–191. doi: 10.1038/nrc2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, M., Zhang W., Wang S., Ge L., Cao X., Wang S., Yuan Z., Lv X., Getachew T., Mwacharo J. M.,. et al. 2022. MicroRNA-181a regulates the proliferation and differentiation of hu sheep skeletal muscle satellite cells and targets the YAP1 gene. Genes. 13:520. doi: 10.3390/genes13030520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horseman, N. D., and Buntin J. D... 1995. Regulation of pigeon crop milk secretion and parental behaviors by prolactin. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 15:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.001241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. C., Gao C. Q., Wang X. H., Yan H. C., Chen Z. S., and Wang X. Q... 2016. Crop milk protein is synthesised following activation of the IRS1/Akt/TOR signalling pathway in the domestic pigeon (Columba livia). Br. Poult. Sci. 57:855–862. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2016.1219694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C. L., He Y. A., Jiang S. G., Wang X. Q., Yan H. C., Tan H. Z., and Gao C. Q... 2023. Chemical composition of pigeon crop milk and factors affecting its production: a review. Poult. Sci. 102:102681. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W., Huang T., Zhou Y., Zhang J., Lung R. W. M., Tong J. H. M., Chan A. W. H., Zhang B., Wong C. C., Wu F.,. et al. 2018. miR-375 is involved in Hippo pathway by targeting YAP1/TEAD4-CTGF axis in gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 9:92. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0134-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kango-Singh, M., and Singh A... 2009. Regulation of organ size: insights from the Drosophila Hippo signaling pathway. Dev. Dyn 238:1627–1637. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, M., and Cole M. D... 2013. MYC acts via the PTEN tumor suppressor to elicit autoregulation and genome-wide gene repression by activation of the Ezh2 methyltransferase. Cancer Res. 73:695–705. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., Son S., Ko Y., and Shin I... 2021. CTGF regulates cell proliferation, migration, and glucose metabolism through activation of FAK signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncogene 40:2667–2681. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01731-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konsavage, W. M., Kyler S. L. Jr, Rennoll S. A., Jin G., and Yochum G. S... 2012. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates Yes-associated protein (YAP) gene expression in colorectal carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287:11730–11739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., Guo X., Zhang T., Wang N., Li J., Xu P., Zhang S., Ren G., and Li D... 2017. Fibroblast growth factor 21 ameliorates high glucose-induced fibrogenesis in mesangial cells through inhibiting STAT5 signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 93:695–704. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N., Nelson B. R., Bezprozvannaya S., Shelton J. M., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., and Olson E. N... 2014. Requirement of MEF2A, C, and D for skeletal muscle regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111:4109–4114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401732111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen T. D... 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S., Meng Z., Chen R., and Guan K. L... 2019. The Hippo Pathway: Biology and pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88:577–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, T., Hayakawa F., Sugimoto K., Iwase M., Yamamoto H., Hirano D., Kojima Y., Imoto N., Naoe T., and Kiyoi H... 2016. The photosensitizer verteporfin has light-independent anti-leukemic activity for Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia and synergistically works with dasatinib. Oncotarget 7:56241–56252. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll, C. S. 1990. Pigeon crop-sac as a model system for studying the direct and indirect effects of hormones and growth factors on cell growth and differentiation in vivo. J. Exp. Zool. Suppl. 4:72–77. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402560413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie, H., Huang P. Q., Jiang S. H., Yang Q., Hu L. P., Yang X. M., Li J., Wang Y. H., Li Q., Zhang Y. F.,. et al. 2021. The short isoform of PRLR suppresses the pentose phosphate pathway and nucleotide synthesis through the NEK9-Hippo axis in pancreatic cancer. Theranostics 11:3898–3915. doi: 10.7150/thno.51712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak, D., Hüser L., Elton J. J., Umansky V., Altevogt P., and Utikal J... 2020. SOX2 in development and cancer biology. Semin. Cancer Biol. 67:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D. 2010. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales, J., and Janssens G... 2003. Nutrition of the domestic pigeon (Columba livia domestica). World's Poult. Sci. J. 59:221–232. doi: 10.1079/wps20030014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L., Wen J., Zhao T., Hu Z., Song C., Gu D., He M., Lee N. P., Xu Z., and Chen J... 2016. A genetic variant in large tumor suppressor kinase 2 of Hippo signaling pathway contributes to prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 9:1945–1951. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S100699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, S., Salimath P. V., and Hegde S. N... 1994. Carbohydrates of pigeon milk and their changes in the first week of secretion. Arch. Int. Physiol. Biochim. Biophys. 102:277–280. doi: 10.3109/13813459409003944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skwarło-Sońta, K. 1992. Prolactin as an immunoregulatory hormone in mammals and birds. Immunol. Lett. 33:105–121. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90034-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine, Z. E., Walton Z. E., Altman B. J., Hsieh A. L., and Dang C. V... 2015. MYC, metabolism, and cancer. Cancer Discov. 5:1024–1039. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W., Li D., Wang P., Musa H. H., Ding J., Li B., Ma Y., Guan W. J., Chu M., Chen L.,. et al. 2012. Postnatal expression of myostatin (MSTN) and myogenin (MYoG) genes in Hu sheep of China. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 11:12246–12251. doi: 10.5897/AJB10.1660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W., Li D., Su R., Musa H. H., Chen L., and Zhou H... 2014. Construction, characterization and expression of full-length cDNA clone of sheep YAP1 gene. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41:947–956. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2939-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, A. M., and Camargo F. D... 2012. Hippo signaling in mammalian stem cells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23:818–826. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X. P., Xie P., Bu Z., Zou X. T., and Gong D. Q... 2019. Prolactin induces lipid synthesis of organ-cultured pigeon crops. Poult. Sci. 98:1842–1853. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt, K. I., Goodman C. A., Hornberger T. A., and Gregorevic P... 2018. The Hippo signaling pathway in the regulation of skeletal muscle mass and function. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 46:92–96. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkanowska, A., Mazurowski A., Mroczkowski S., and Kokoszyński D... 2014. Prolactin (PRL) and prolactin receptor (PRLR) genes and their role in poultry production traits. Folia. Biol. (Krakow). 62:1–8. doi: 10.3409/fb62_1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W., Wang J., Ou C., Zhang Y., Ma L., Weng W., Pan Q., and Sun F... 2013. Mutual interaction between YAP and C-Myc is critical for carcinogenesis in liver cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 439:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P., Jiang X. Y., Bu Z., Fu S. Y., Zhang S. Y., and Tang Q. P... 2016. Free choice feeding of whole grains in meat-type pigeons: 1. effect on performance, carcass traits and organ development. Br. Poult. Sci. 57:699–706. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2016.1206191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P., Wang X. P., Bu Z., and Zou X. T... 2017. Differential expression of fatty acid transporters and fatty acid synthesis-related genes in crop tissues of male and female pigeons (Columba livia domestica) during incubation and chick rearing. Br. Poult. Sci. 58:594–602. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2017.1357798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P., Wan X. P., Bu Z., Diao E. J., Gong D. Q., and Zou X. T... 2018. Changes in hormone profiles, growth factors, and mRNA expression of the related receptors in crop tissue, relative organ weight, and serum biochemical parameters in the domestic pigeon (Columba livia) during incubation and chick-rearing periods under artificial farming conditions. Poult. Sci. 97:2189–2202. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H., Zhao M., Huang S., Chen P., Wu W. Y., Huang J., Wu Z. S., and Wu Q... 2016. Prolactin inhibits BCL6 expression in breast cancer cells through a microRNA-339-5p-dependent pathway. J. Breast Cancer 19:26–33. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X., Xu Y., Jiang C., Ma Z., and Jin L... 2021. Verteporfin suppresses osteosarcoma progression by targeting the Hippo signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 22:724. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. M., Zhang T. T., An S. Y., El-Samahy M. A., Yang H., Wan Y. J., Meng F. X., Xiao S. H., Wang F., and Lei Z. H... 2019. Expression of Hippo signaling pathway components in Hu sheep male reproductive tract and spermatozoa. Theriogenology 126:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B., Ye X., Yu J., Li L., Li W., Li S., Yu J., Lin J. D., Wang C. Y., Chinnaiyan A. M.,. et al. 2008. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F., Lin T., He W., Han J., Zhu D., Hu K., Li W., Zheng Z., Huang J., and Xie W... 2015. Knockdown of a novel lincRNA AATBC suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in bladder cancer. Oncotarget 6:1064–1078. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y., and Pan D... 2019. The Hippo signaling pathway in development and disease. Dev. Cell 50:264–282. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y., Capuco A. V., and Jiang H... 2008. Involvement of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF1) stimulation of proliferation of a bovine mammary epithelial cell line. Domest Anim. Endocrinol. 35:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. G., Xie P., Song C., Liu T. W., and Gong D. Q... 2023a. Differential expression of glucose metabolism-related genes and AMP-activated protein kinases in crop tissue of male and female pigeons (Columba livia domestica) during the incubation and chick-rearing periods. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl) 107:680–690. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. G., Xie P., Zheng M. D., Meng Y., Wei M. L., Liu Y., Liu T. W., and Gong D. Q... 2023b. Dynamic changes in protein concentrations of keratins in crop milk and related gene expression in pigeon crops during different incubation and chick rearing stages. Br. Poult. Sci. 64:100–109. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2022.2119836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]