Abstract

Background

Concern has been expressed about the relevance of secondary care studies to primary care patients specifically about the effectiveness of antidepressant medication. There is a need to review the evidence of only those studies that have been conducted comparing antidepressant efficacy with placebo in primary care‐based samples.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants in patients (under the age of 65 years) with depression in primary care.

Search methods

All searches were conducted in September 2007.

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) Controlled Trials Register was searched, together with a supplementary search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, LILACS, CINAHL and PSYNDEX. Abstracts of all possible studies for inclusion were assessed independently by two reviewers. Further trials were sought through searching the reference lists of studies initially identified and by scrutinising other relevant review papers. Selected authors and experts were also contacted.

Selection criteria

Studies were selected if they were randomised controlled trials of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) versus placebo in adults. Older patients (over 65 years) were excluded. Patients had to be recruited from a primary care setting. For continuous outcomes the Hamilton Depression scale of the Montgomery Asberg Scale was required.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted using data extraction forms by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by discussion. A similar process was used for the validity assessment. Pooling of results was done using Review Manager 5. The primary outcome was depression reduction, based on a dichotomous measure of clinical response, using relative risk (RR), and on a continuous measure of depression symptoms, using the mean difference (MD), with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

There were fourteen studies (16 comparisons) with extractable data included in the review, of which ten studies examined TCAs, two examined SSRIs and two included both classes, all compared with placebo. The number of participants in the intervention groups was 1364 and in the placebo groups 919. Nearly all studies were of short duration, typically 6‐8 weeks. Pooled estimates of efficacy data showed an RR of 1.24, 95% CI 1.11‐1.38 in favour of TCAs against placebo. For SSRIs this was 1.28, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.43.. The numbers needed to treat (NNT) for TCAs ranged from 7 to 16 {median NNT 9} patient expected event rate ranged from 63% to 26% respectively) and for SSRIs from 7 to 8 {median NNT 7} (patient expected event rate ranged from 48% to 42% respectively) . The numbers needed to harm (NNH for withdrawal due to side effects) ranged from 4 to 30 for TCAs (excluding three studies with no harmful events leading to withdrawal) and 20 to 90 for SSRIs.

Authors' conclusions

Both TCAs and SSRIs are effective for depression treated in primary care.

Plain language summary

Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care

Depression in the primary care setting is very common. However, most systematic reviews of antidepressant treatment have included trials conducted in secondary care settings. There has been doubt about the effectiveness of antidepressants in primary care, and hence the impetus to do this review. Through extensive searches of the literature we found 14 studies conducted in adults (not the elderly) in primary care setting, in which tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were compared against a placebo control group in the treatment of depression. The results showed that both TCAs and SSRIs were effective for depression. Most of the studies were supported by funds from pharmaceutical companies and were of short duration. There appeared to be more adverse effects with TCAs than with SSRIs, however rates of withdrawal from study medication due to adverse effects were very similar between the two antidepressant classes. Adverse effects not leading to medication cessation seemed to be more common with TCAs than SSRIs.

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is very common in primary care, with a 12‐month prevalence of 18.1% (including dysthymia 0.8%). There is considerable overlap with anxiety and substance use (MAGPIE 2003). Depression is also common in the community, with a 12‐month prevalence of 7.1% (Oakley‐Browne 2006).

It is a paradox that whilst the vast majority of patients with clinical depression are dealt with in primary care, most of the research findings upon which decisions are made have involved secondary care patients. This is important because research suggests that patients with depressive disorders in primary care have different aetiology, pathophysiology and natural history from those of psychiatric inpatients or outpatients (Arya 1999; Suh 1999). Often, depressed primary care patients present with somatic symptoms, which include gastrointestinal, skeletal muscle, and cardiovascular complaints, as opposed to describing non‐somatic criteria for depression.

Description of the intervention

The most commonly used antidepressants in the treatment of depression in primary care are tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). It is generally thought that TCAs act by inhibiting the re‐uptake by nerve cells of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, dopamine, or serotonin. Tricyclics may have an affinity for muscarinic and histamine H1 receptors. Norepinephrine and dopamine are considered stimulatory neurotransmitters, but tricyclic antidepressants also increase the effects H1 histamine, and hence have sedative effects. SSRIs are a class of antidepressants used in the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders. SSRIs increase the level of the serotonin by inhibiting its reuptake into the presynaptic (brain) cell, increasing the level of serotonin available to bind to the postsynaptic receptor.

Doubts about the effectiveness of antidepressant medication and other therapies such as cognitive therapy may contribute to the variability in primary care management of depression (Jenkins 2001; King 2002). Up to 40% of depressed patients fail to demonstrate a response to first line antidepressant drug treatment (Joffe 1996) and of those that do respond only a proportion will achieve full recovery (APA 1993). One cohort study of primary care patients found 60% of those treated with medication and 50% with milder depression still met the criteria for depression at one year (Goldberg 1998).

Why it is important to do this review

Recent calls indicate an urgent need to review the evidence of only those studies that have been conducted concerning antidepressant efficacy on primary care based samples (Gill 1997; NCCHTA 2000). Systematic reviews of antidepressant medication often include patients who are seen in outpatient facilities rather than being seen in primary care or at least recruited from primary care (Ellis 2002). Concern has been expressed about the relevance of secondary care studies to primary care patients (NCCHTA 2000; Gill 1997). We are aware of only two published systematic reviews on patients either seen or recruited in primary care. Both compared newer antidepressants with older antidepressants (Mulrow 2000; MacGillivray 2003). The review by Mulrow and colleagues (Mulrow 2000) had a small section on antidepressant drugs versus placebo but reviewed only four studies. The MacGillivray review (MacGillivray 2003) compared SSRIs with TCAs, and hence only commented on relative efficacy. Comparison with placebo is needed to obtain absolute efficacy. A paper version of this Cochrane review was published in 2005 (Arroll 2005). A review of new generation antidepressants to the Food and Drug Administration found that they were only effective with those patients with more severe depression (Kirsch 2008).

These considerations indicate a need to review the evidence of only those studies that have been conducted comparing antidepressant efficacy with placebo on primary care based samples (Gill 1997; NCCHTA 2000).

Objectives

The aim of this review was to examine the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressant medication compared with placebo in studies of treating depression in adults aged less than 65 years in primary care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials only were included. Cross‐over trials were not included as the course of depression is neither fluctuating nor rapidly responsive to treatment and hence not considered suitable for this method.

Types of participants

To be included in the review studies had to include adults of 18 years or older. Studies with a majority (more than 50%) of participants over 65 years or under 18 years of age were excluded. Patients were required to be recruited from a primary care clinic.

The diagnosis of unipolar depression was based on formal diagnostic interviews according to international criteria such as the ICD (International Classification of Disease ‐WHO) or the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual American Psychiatric Association). Studies in which GPs thought the patient was depressed, and that the symptoms warranted pharmacological therapy, were also included.

A post hoc decision was made to exclude studies in which participants were diagnosed with co‐morbid physical or mental conditions.

Types of interventions

Intervention Antidepressants for inclusion in the review were tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tetracyclic medication (eg Mianserin) that are currently in use in some countries. Tetracyclic medications were included in the TCA group, as their side effect profile is similar to TCAs. Studies were required to be of a duration of at least four weeks. A post hoc decision was made that medication(s) needed to be regarded as in current clinical use (in the view of review authors) to be included in the review.

Studies involving monoamine oxidase inhibitors and serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) were not included in the review. In future updates of the review, a comparison of SNRI medication versus placebo will be included.

Main comparisons 1. TCAs versus placebo 2. SSRIs versus placebo

Types of outcome measures

Only trials with extractable data were included in the review.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was reduction in depression symptoms, measured in the following ways:

1. Continuous outcomes, reported as reduction in depression symptoms at post‐treatment, in terms of validated depression rating scales (the most commonly used were the Hamilton depression rating scale {Hamilton 1960) and the Montgomery‐Asberg scale Montgomery 1979})

2. Dichotomous outcomes, reported as clinical response post‐treatment. Outcomes were considered positive for remission where a 50% reduction from intimal score or a score of less than 8 on the Hamilton Depression rating scale was achieved. Response ranged from any response (sometimes unspecified) to full remission. A similar approach is used with the Montgomery ‐Asberg scale. The dichotomous outcomes were needed to generate numbers needed to treat (NNT) values.

Secondary outcomes

1. Occurrence of adverse effects

2. Withdrawal from trials due to: a) adverse effects b) treatment failure c) any reasons

3. Economic outcomes

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group's Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintain two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 33,500 reports of RCTs in depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique Study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐Psi coding manual, using a controlled vocabulary, please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Coordinator for further details. Reports of trials for inclusion in the Group's registers are collated from routine (weekly), generic searches of MEDLINE (1950‐), EMBASE (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐); quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trials registers c/o the World Health Organization's trials portal (the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)), pharmaceutical companies, the handsearching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses.

Details of CCDAN's generic search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website.

Electronic searches

An updated electronic search of the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Registers (CCDANCTR‐Studies and CCDANCTR‐References was conducted to 31 December 2013 (Appendix 1).

There was no restrictions on date, language or publication status applied to the searches

Searching other resources

Reference lists Further trials were sought through searching the reference lists of studies initially identified and by scrutinising other relevant review papers.

Other sources Authors of all selected papers were approached and asked if they had or knew of unpublished studies or published studies that we had not found.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two of the reviewers (BA and SM) read all the abstracts and decided which were relevant to the review. Where it was unclear from the abstract if the study was relevant to this review a full paper was reviewed

Data extraction and management

Review authors independently extracted the data and compared their results. Disagreement on findings were discussed and resolved through discussion. Formal data extraction sheets were not used.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality assessment Assessment of methodological quality was performed using the Quality Rating Scale (Moncrieff 2001) (see Table 1 for a description of each item on the scale). Seven key methodological items from the QRS were also selected. To be a high quality study the total score had to be ≥ 27 and to have no zero scores in any of the seven key components of quality (see below). The seven items were chosen as they were considered essential aspects of quality (a score of 0 on any component indicates poor quality for that item, 2 indicates good quality).

1. Quality Rating Scale items.

| No | Item___________________________________________ | Components_________________________________________ |

| 1 | Objectives and specification: Were main outcomes established a priori? | 0 = Objectives unclear 1 = Objectives clear but main outcomes not specified a priori 2 = Objectives clear with a priori specification of main outcomes |

| 2 | Adequacy of sample size: Were there enough completers in each group? | 0 = No/don't know 2 = Yes |

| 3 | Planned duration of trial including follow up? | 0 = < 3 months 1 = > 3 months < 6 months 2 = > 6 months |

| 4 | Method of allocation | 0 = Not randomised and likely to be biased 1 = Partially or quasi randomised with some bias possible 2 = Randomised allocation |

| 5 | Concealment of allocation | 0 = Not done or not reported 1 = Partial concealment reported 2 = Done adequately |

| 6 | Clear description of treatment (including doses of drugs) & adjunctive treatment | 0 = Main treatments not clearly described 1 = Inadequate details of main or adjunctive treatments 2 = Full details of main and adjunctive treatments |

| 7 | Blinding of subjects | 0 = Not done 1 = Blinded but no test of blinding 2 = Blinded and integrity of blinding tested |

| 8 | Source of subjects described and representative sample recruited? | 0 = Source of subjects not described 1 = Source of subjects but unrepresentative sample e.g. in‐patients/specialist settings 2 = Source of subjects described plus representative sample |

| 9 | Use of diagnostic criteria (or clear specification of inclusion criteria) | 0 = None 1 = Diagnostic criteria or clear inclusion criteria 2 = Diagnostic criteria + specification of severity |

| 10 | Record of exclusion criteria and number of exclusions and refusals reported? | 0 = Criteria and number not reported 1 = Criteria or number of exclusions & refusals not reported 2 = Criteria and number of exclusions and refusals reported |

| 11 | Description of sample demographic characteristics? | 0 = Little/no information (only age/sex) 1 = Basic description (e.g. marital status/ethnicity) 2 = Full description (e.g. socio‐economic status/clinical history) |

| 12 | Blinding of assessor | 0 = Not done 1 = Blinded but no test of blinding 2 = Blinded and integrity of blinding tested |

| 13 | Assessment of compliance with experimental treatments (including adherence to therapy) | 0 = Not assessed 1 = Assessed for some experimental treatments 2 = Assessed for all experimental treatments |

| 14 | Details on side effects | 0 = Inadequate details 1 = Recorded by group but details inadequate 2 = Full side effect profiles by group |

| 15 | Record of number and reasons for withdrawal by group | 0 = No information on withdrawals by group 1 = Withdrawals by group reported without reason 2 = Withdrawals and reason by group |

| 16 | Outcome measures described clearly or use of validated instruments | 0 = Outcomes not described clearly 1= Some outcomes not clearly described 2= Outcomes described or valid & reliable instruments used |

| 17 | Information on comparability and adjustment for differences in analysis | 0= No information on comparability 1= Some info on comparability with appropriate adjustment 2= Sufficient comparability info with appropriate adjustment |

| 18 | Inclusion of withdrawals in analysis (ITT or endpoint) | 0 = Not included or not reported 1 = Withdrawals included in analysis by estimation of outcome 2 = Withdrawals followed up and included in analysis |

| 19 | Presentation of results with inclusion of data for re‐analysis of main outcomes (e.g. SDs) | 0 = Inadequate presentation 1= Adequate 2 = Comprehensive |

| 20 | Appropriate statistical analysis (including correction for multiple tests where applicable) | 0 = Inappropriate 1 = Mainly appropriate 2 = Appropriate and comprehensive |

| 21 | Conclusions justified | 0 = No 1 = Partially 2 = Yes |

| 22 | Declaration of interests (e.g. source of funding) | 0 = No 2 = Yes |

| Notes: 1= Details on how the allocation code was protected from those involved in patient recruitment may be achieved by having allocation done by a central independent body, or protection of code (e.g. sealed opaque envelopes). 2= Source of subjects refers to the setting in which subjects were found (e.g. inpatients, outpatients, general practice, community etc). 3= Test of integrity of blinding is normally done by asking participants to guess their allocated group. Results can be compared to those which would be expected by chance. 4= Whether or not the decision to initiate an antidepressant was based strictly on the primary care practitioners judgment that there was clinical depression warranting treatment rather than insisting that criteria for a specific diagnosis, such as major depressive disorder, be established. |

Seven key QRS components included:

Item 2 = Adequacy of sample size

Item 5 = Allocation concealment

Item 6 = Clear description of treatment

Item 8 = Representative source of participants

Item 9 = Use of diagnostic criteria or clear specification of inclusion criteria.

Item 15 = Details regarding number and reasons for withdrawal by group.

Item 16 = Outcome measures described clearly or use of validated instrument

Risk of bias assessment Item 5 of the QRS, allocation concealment, represented one domain of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins 2008). The Risk of Bias tool covers a total of six domains (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias), and is now recommended for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane reviews. In future updates of this review, studies will be assessed for risk of bias using all domains of this tool.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes, the standardised mean difference (SMD) was used when different depression questionnaires were being used between studies in a comparison, and the mean difference was used when the same questionnaire was being used, together with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

For dichotomous outcomes, a pooled risk ratio (RR) was calculated, together with a 95% CI. When overall results were significant, the number needed to treat (NNT) or harm (NNH) to produce one outcome was calculated by combining the overall risk ratio with an estimate of the prevalence of the event in the control group of the trials.

Unit of analysis issues

Where one control group and two medications were used in a study, the control group was split in half for both the numerator and the denominator.

Dealing with missing data

There was no adjustment by the reviewers for intention to treat (ITT) analysis. Unless study authors did an ITT analysis, the analyses were done per protocol.

Continuous outcomes: where values were missing, certain assumptions were made. Where results were not reported in tables or the text but presented as graphs, the values were estimated from reading the graph and included as "approximated" results. The results of this line of sight method was agreed upon by two of the review authors. Where standard errors (SE) or confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, the SD was calculated from those figures. Where standard deviations (SD) of final results were not stated, and SEs and CIs were also not reported, baseline SDs or the highest SD from all studies reviewed for the same variable and group (intervention or control) was used. For HAMD scores, the highest value for SD for placebo in the TCA studies was 9.6 (Blashki (75mg) 1971) and 7.3 for intervention arms in the TCA studies (Brink 1984). For MADRS scores, the highest values for SDs were 10.3 for the Sertraline arm (Wade 2002), 4.5 for Mianserin arm and 9.1 for placebo (Malt 1999). These were baseline SDs and were used when SDs in other studies were not reported in the corresponding groups.

Dichotomous outcomes: The denominator for incidence of adverse events was the number for which data were collected (i.e. initial drop‐outs for which there were no data were not included). However the denominator for incidence of withdrawals for any reason was the number randomised (i.e. including initial drop‐outs for which there were no data).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was formally tested using the natural approximate chi‐square test, with the p‐value conservatively set at 0.1. Heterogeneity was also tested using the I2 statistic, with I2 values over 50% indicating strong heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

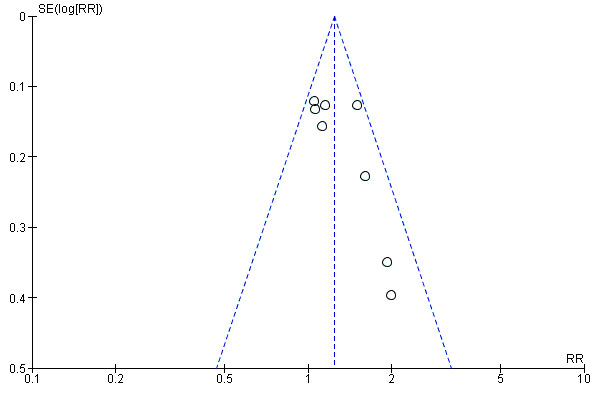

Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot in RevMan 5 (Figure 1).

1.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 TCAs versus placebo, outcome: 1.2 Clinical response at post‐treatment.

Data synthesis

Random effects analysis was used if the I2 was greater than 50%.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were conducted for the following clinical characteristics:

1. Dosage of antidepressant 2. UK based studies vs European and US based studies

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of results for the following internal validity criteria:

1. Use of approximated data versus non‐approximated data 2. High quality (≥27 on QRS) versus low quality studies 3. Major depression diagnosis only 4. Different depression scales 5. Proportion of GP assessors (use of GP assessors was chosen for one of the sensitivity analyses as it was thought that GPs may have a different way of assessing depression than psychiatrists) 6. No competing interests

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Earlier searches of CCDAN's specialized Register (to 2007), conducted for the first version of this review, retrieved 82 references. Following screening of abstracts obtained through these searches and scanning reference lists, hard copies of 37 articles were obtained. Of those, fourteen studies (16 different comparisons) met the full inclusion criteria for the review (published 2009).

The search was updated in December 2013 when 151 additional references were retrieved, yielding two possible new studies which are in Studies awaiting classification. It is believed that the incorporation of these studies when the review is next updated in full will not materially alter the conclusions.

Included studies

The studies are described individually in the Characteristics of Included studies table.

Study design All studies were randomised controlled trials.

Participants The studies included in the review covered a range of depressive disorders. One TCA study included only patients with major depressive disorder (Barge‐Schaapveld 2002). Two studies of SSRIs included only patients with major depressive disorder (Lepola 2001 Citalopram; Lepola 2001 Escitalopram; Wade 2002), as did one study with both TCA and SSRI arms (Doogan 1994).

Interventions Ten trials (11 comparisons) examining TCAs were identified. The TCA drugs included imipramine Barge‐Schaapveld 2002; Lecrubier 1997; Philipp 1999), amitriptyline (Blashki (75mg) 1971; Blashki (150 mg) 1971; Feighner 1979; Hollyman 1988; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Thomson 1982), dothiepin (Thompson 1989); and mianserin (Brink 1984).

Two trials (three comparisons) examined an SSRI drug. The SSRIs included citalopram (Lepola 2001 Citalopram) and escitalopram (Lepola 2001 Escitalopram;; Wade 2002).

Two trials included both a TCA and an SSRI arm. Doogan 1994 compared sertraline and dothiepin against a placebo control. Malt 1999 examined sertraline and mianserin against placebo.

We found no trials in primary care for monoamine oxidase inhibitors and only one on venlafaxine. For the purposes of the current version of the review, the focus is on TCAs and SSRIs.

Outcomes For the continuous outcomes the two scales used and reported were either the Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAMD) or the Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS). These two rating scales were the ones most commonly used. Occasionally others were reported (e.g. Lecrubier 1997 for discrete outcomes). For consistency and for the purposes of comparison, we used HAMD and MADRS data only.

Excluded studies

Twenty studies were excluded from the review which had been identified through a search of the CCDAN Register as being of potential relevance to the review and required investigation beyond the title and CCDAN coding provided. Studies excluded from the review are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies, with reasons for exclusion.

Reasons included participants with physical comorbidities (n = 2); psychiatric comorbidity (e.g., both anxiety and depression) (n= 1) or participants from mixed setting (e.g. both primary and secondary care) (n=1).

In five cases, studies turned out not to have carried out in a primary care setting, or to feature treatment delivered by psychiatrists and not primary care staff. In a further five studies drugs were given either as combined treatment or against non‐eligible comparators (of these, one study appeared to have a placebo arm but in fact included two active treatment arms which were both also given placebos) (O'Hara 1978). Two studies were related to other studies included within the review. On closer inspection one study was found to have an inadequate design; one an inappropriate drug (a monoamine oxidase inhibitor); one assessed outcomes on the Leeds Depression Scale only, and one study involved a drug we considered no longer to be in current clinical use (the TCA iprindole) (Rickels 1968)).

Studies awaiting classification

Two studies are awaiting classification following an update search in 2013 (Hegerl 2010; Miller 1989). Their inclusion in the review would not materially alter the conclusions of this review. See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for details of the studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Eight of the fourteen studies included in the review were assessed as having adequate allocation concealment (Barge‐Schaapveld 2002; Blashki (75mg) 1971/Blashki (150 mg) 1971; Doogan 1994; Feighner 1979; Hollyman 1988; Malt 1999; Mynors‐Wallis 1995, Wade 2002)

Other sources of bias (see Table 2 for individual scores of each study)

2. Methodological quality of included studies.

| Author and year | Sample size adequacy | Concealment | Treatment description | Representative sample | Diagnostic criteria | Withdrawals | Outcome measures | Total |

| Barge‐Schaapveld 2002 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 31 |

| Blashki 1971 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30 |

| Brink 1984 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 26 |

| Doogan 1994 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 30 |

| Feighner 1979 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 27 |

| Hollyman 1988 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 38 |

| Lecrubier 1997 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 32 |

| Lepola 2001 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 28 |

| Malt 1999 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 34 |

| Mynors‐wallis 1995 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 34 |

| Philipp 1999 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 37 |

| Thompson 1989 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 26 |

| Thomson 1982 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 25 |

| Wade 2002 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 32 |

Sample size adequacy Ten studies were considered to have an adequate sample size (Barge‐Schaapveld 2002; Blashki (75mg) 1971/Blashki (150 mg) 1971; Doogan 1994; Feighner 1979; Hollyman 1988; Lepola 2001 Citalopram/Lepola 2001 Escitalopram; Malt 1999; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Philipp 1999; Wade 2002).

Clear description of treatment All studies included in the review provided a clear description of the antidepressant treatment and placebo groups.

Representative source of participants Nine studies were considered to have described and recruited a representative sample (Brink 1984; Doogan 1994; Hollyman 1988; Lecrubier 1997; Malt 1999; Mynors‐Wallis 1995; Philipp 1999; Thompson 1989;Thomson 1982).

Use of diagnostic criteria All studies used diagnostic criteria and specified the severity of depression, with the exception of Blashki (75mg) 1971/Blashki (150 mg) 1971 and Thomson 1982.

Withdrawals All studies followed up withdrawals and included them in analyses with the exception of Barge‐Schaapveld 2002, Doogan 1994, Mynors‐Wallis 1995 and Thompson 1989.

Outcome measures Only one study did not fully describe and use validated instruments (Doogan 1994).

Effects of interventions

A fixed effect model was used for all analyses unless otherwise stated. If the I‐squared statistic was >50%, a random effects model was used.

COMPARISON 1: TCAs VERSUS PLACEBO

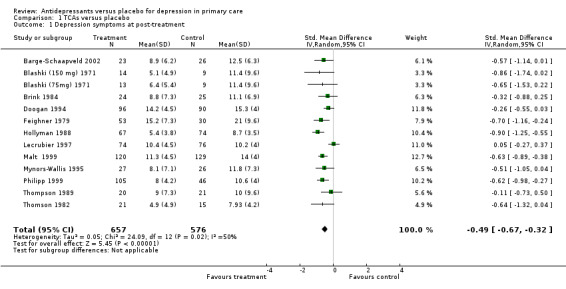

Primary outcome 1. Reduction in depression symptoms at post‐treatment There were 12 studies included in this analysis and 13 comparisons (one study reported on two doses, Blashki (150 mg) 1971, Blashki (75mg) 1971, and hence is reported here as two arms versus placebo). The standardised mean difference (SMD) was ‐0.49 95% CI ‐0.67 to ‐0.32 (random effects) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 1 Depression symptoms at post‐treatment.

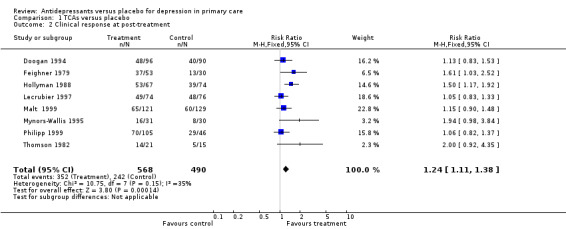

2. Clinical response at post‐treatment There were 8 studies for this analysis with 8 comparisons. The relative risk for benefit (response) was 1.24, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.38 (Analysis 1.2). Response ranged from any response to remission.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 2 Clinical response at post‐treatment.

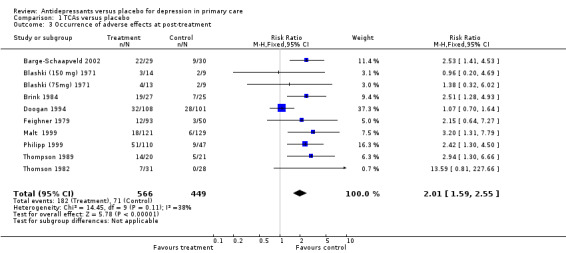

Secondary outcomes 1. Occurence of adverse effects at post‐treatment This forest plot reports the adverse effects not necessarily causing withdrawal from the study for patients on tricyclic antidepressants. The relative risk for harm was 2.01, (95% CI 1.59 to 2.55) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 3 Occurrence of adverse effects at post‐treatment.

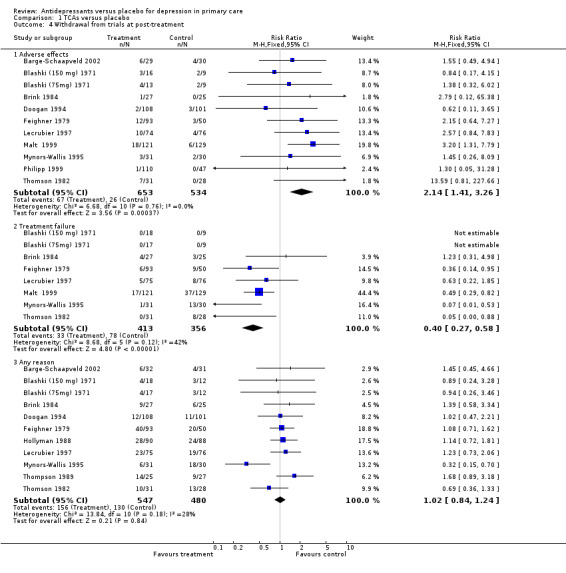

2. Withdrawal from trials at post‐treatment (Analysis 1.4) For withdrawal from the study due to adverse effects for patients on tricyclic antidepressants, the relative risk for harm was 2.14, 95% CI 1.41 to 3.26.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 4 Withdrawal from trials at post‐treatment.

For withdrawal due to treatment failure for patients on tricyclic antidepressants, there was a reduction in effect and hence a positive result suggesting more treatment failure in the placebo group, reported as a relative risk less than one. The relative risk was 0.40, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.58.

For withdrawal due to any reason for patients on tricyclic antidepressants, the relative risk was 1.02, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.24.

3. Economic outcomes No studies contributed economic data.

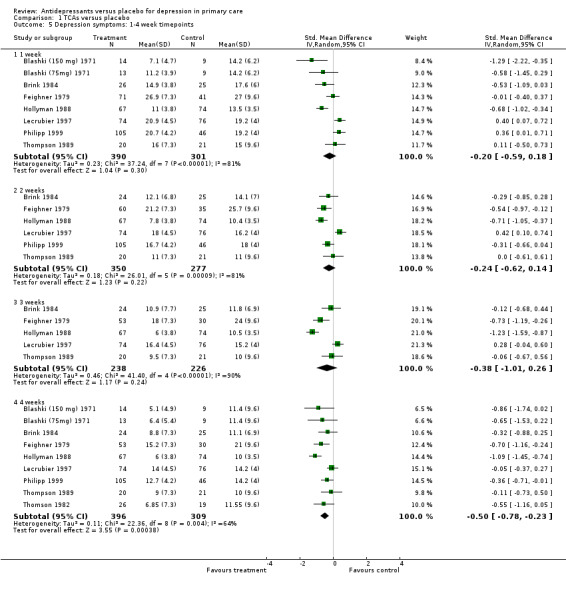

Reduction in depression symptoms:1‐4 week time points (Analysis 1.5) One week: For these studies, the SMD was ‐0.2, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.18 (random effects).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 5 Depression symptoms: 1‐4 week timepoints.

Two weeks: For these studies, the SMD was ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐0.62 to 0.14 (random effects).

Three weeks: For these studies, the SMD was ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐1.01 to 0.26 (random effects).

Four weeks: For these studies, the SMD was ‐0.50, 95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.23 (random effects)

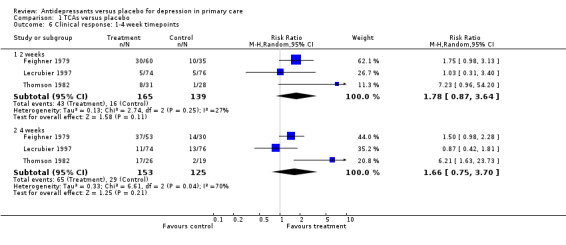

Clinical response: 1‐4 week time points (Analysis 1.6) Two weeks: The Lecrubier 1997 study used the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale to report percentage 'very much improved' instead of using the MADRS. Therefore the CGI was used for this analysis in this paper. The relative risk for benefit was 1.78, 95% CI 0.87 to 3.64 (random effects).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 6 Clinical response: 1‐4 week timepoints.

Four weeks: For these studies, the relative risk for benefit was 1.66, 95% CI 0.75 to 3.70 (random effects).

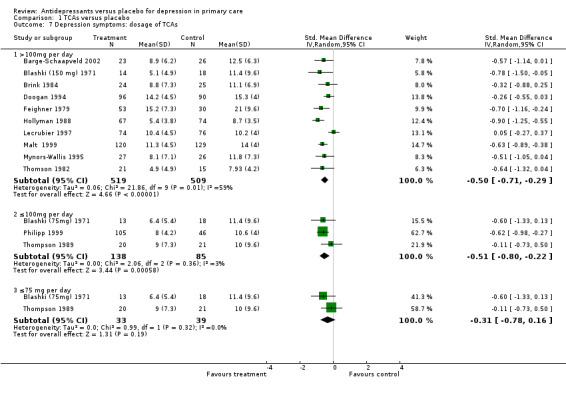

Subgroup analyses

1. Dosage of TCAs Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.7) Dose >100mg per day: For these studies in which patients were on more than 100mg per day of tricyclic antidepressant, the SMD was ‐0.5, 95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.29 (random effects).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 7 Depression symptoms: dosage of TCAs.

Dose ≤ 100 mg per day: For studies in which patients started on 100mg or less per day of tricyclic antidepressant, only Blashki (75mg) 1971 stayed at that dose. In Thompson 1989 the dose started at 75mg of Dothiepin but could go up to 150mg per day and for Philipp 1999 the starting dose of Imipramine was 50 mg but could go to 100mg. The SMD was ‐0.51, 95%CI ‐0.80 to ‐0.22 (random effects).

Dose ≤ 75 mg per day: For those studies with patients who stayed on 75 mg or lower the SMD was ‐0.31, 95%CI ‐0.78 to 0.16 (random effects)

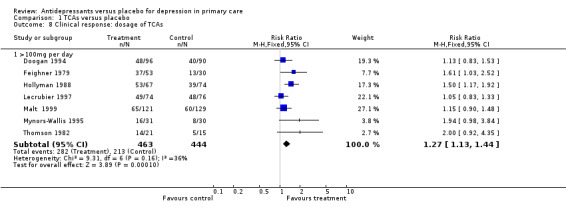

Clinical response (Analysis 1.8) For these studies, patients needed to be on more than 100 mg per day of tricyclic antidepressant and the outcomes were dichotomous. The relative risk for benefit (a response) was 1.27, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.44.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 8 Clinical response: dosage of TCAs.

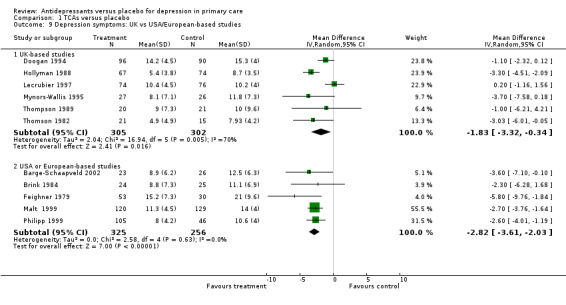

2. UK vs USA/European‐based studies Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.9) For patients recruited in the United Kingdom, the mean difference was ‐1.83, 95% CI ‐3.32 to ‐0.34 (random effects). For patients recruited in the USA or Europe, the mean difference was ‐2.82, 95% CI ‐3.61 to ‐2.03 (random effects).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 9 Depression symptoms: UK vs USA/European‐based studies.

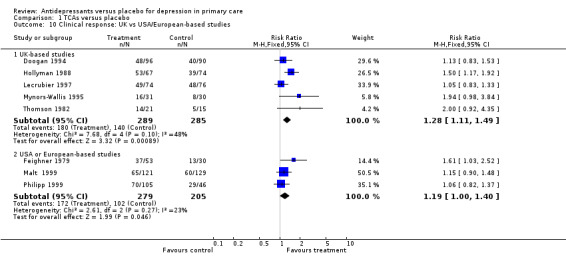

Clinical response (Analysis 1.10) For patients recruited in the United Kingdom, the relative risk for benefit was 1.28, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.49. For patients recruited in the USA or Europe, the relative risk for benefit was 1.19, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.40.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 10 Clinical response: UK vs USA/European‐based studies.

Sensitivity analyses

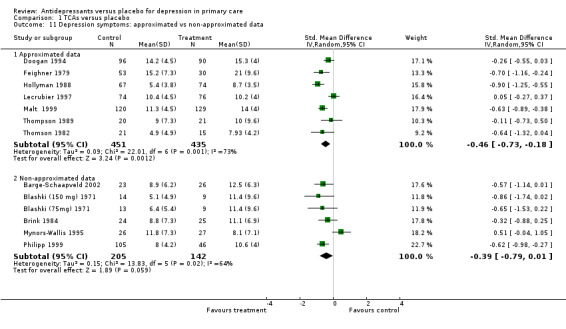

1. Approximated vs non‐approximated data Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.11) For approximated data, there were seven studies in the analysis, with the approximations resulting from an "eyeball" reckoning from a graph or use of standard deviations from other studies where there were none reported. The SMD was ‐0.46, 95 %CI ‐0.73 to ‐0.18 (random effects). For non‐approximated data, the SMD was ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐0.79 to 0.01.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 11 Depression symptoms: approximated vs non‐approximated data.

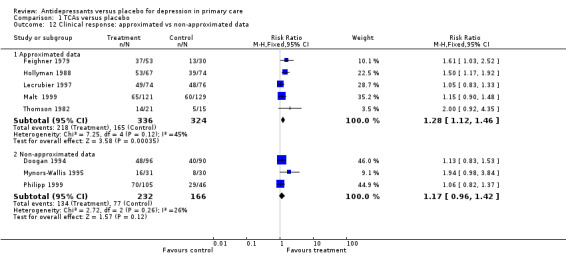

Clinical response (Analysis 1.12) For approximated data, the values obtained from studies were usually "eyeballed" from graphs in the paper.The relative risk for benefit (a response) was 1.28, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.46. For non‐approximated data, the relative risk for benefit (a response) was 1.17, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.42.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 12 Clinical response: approximated vs non‐approximated data.

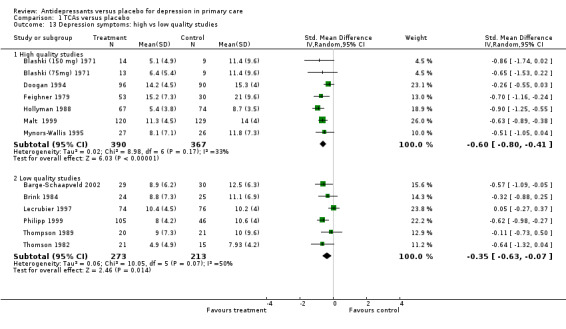

2. High versus low quality studies Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.13) For high quality studies (quality score of 28 or more out of 44 and no zeros on the seven key methodological items), the SMD was ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐0.80 to ‐0.41(random effects). For low quality studies, the SMD was ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.63 to ‐0.07 (random effects).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 13 Depression symptoms: high vs low quality studies.

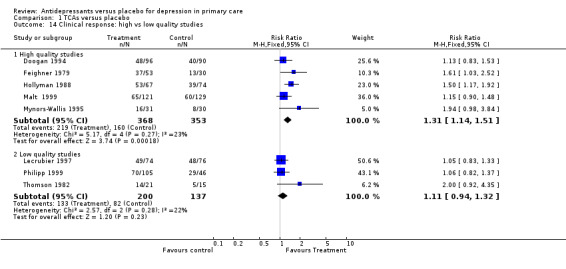

Clinical response (Analysis 1.14) For high quality studies, the relative risk for benefit was 1.31, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.51. For low quality studies, the relative risk for benefit was 1.11, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.32.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 14 Clinical response: high vs low quality studies.

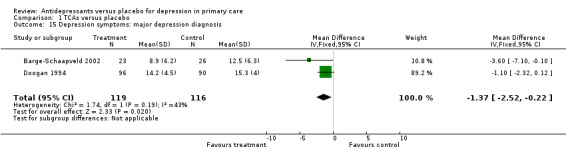

3. Major depression diagnosis Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.15) For studies in which patients had a diagnosis of major depression, the mean difference was ‐1.37, 95% CI ‐2.52 to ‐0.22.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 15 Depression symptoms: major depression diagnosis.

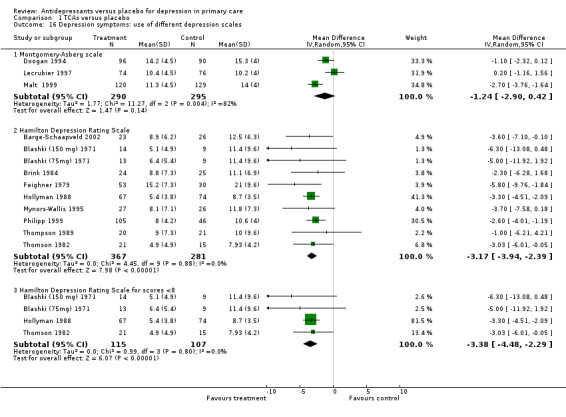

4. Use of different depression scales Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.16) For studies using the Montgomery‐Asberg scale, the mean difference was ‐1.24, 95% CI ‐2.90 to 0.42 (random effects). For studies using the Hamilton Depression Scale, the mean difference was ‐3.17, 95% CI ‐3.94 to ‐2.39 (random effects). For studies where the outcomes were continuous but included outcomes of remission (less than 8 on the Hamilton Depression Scale), the mean difference was ‐3.38, 95% CI ‐4.48 to ‐2.29 (random effects).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 16 Depression symptoms: use of different depression scales.

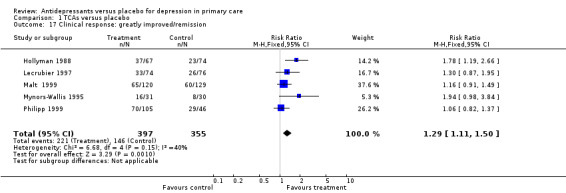

Clinical response:greatly improved/remission (Analysis 1.17) For studies in which patients had outcomes of greatly improved or remission data, the relative risk for benefit was 1.29 95% CI (1.11 to 1.50).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 17 Clinical response: greatly improved/remission.

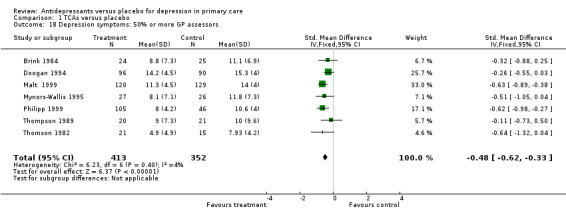

5. 50% or more GP assessors Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.18) For studies in which at least half or more of the assessors were primary care providers, the SMD was ‐0.48, 95% CI ‐0.62 to ‐0.33.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 18 Depression symptoms: 50% or more GP assessors.

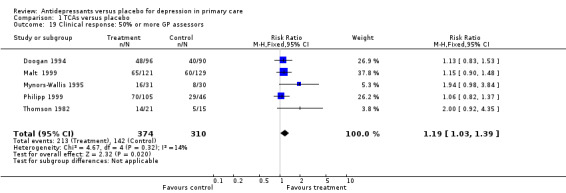

Clinical response (Analysis 1.19) For studies in which at least half or more of the assessors were primary care providers, the relative risk for benefit (a response) was 1.19, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.39.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 19 Clinical response: 50% or more GP assessors.

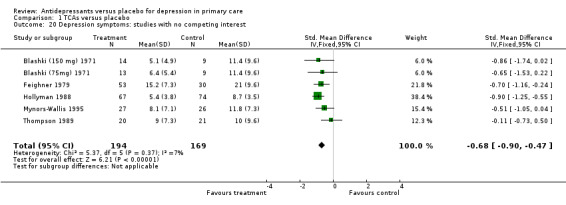

6. Studies with no competing interest Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 1.20) For studies where no competing interest was expressed (i.e. no pharmaceutical company), the SMD was ‐0.68, 95% CI ‐0.90 to ‐0.47.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 20 Depression symptoms: studies with no competing interest.

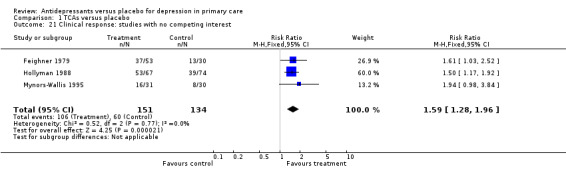

Clinical response (Analysis 1.21) For studies in which no competing interest was expressed (i.e. no pharmaceutical company), the relative risk for benefit was 1.59, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.96.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 TCAs versus placebo, Outcome 21 Clinical response: studies with no competing interest.

COMPARISON 2: SSRIs VERSUS PLACEBO

Primary outcome

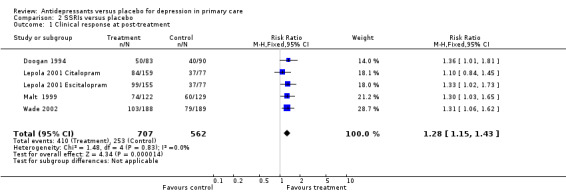

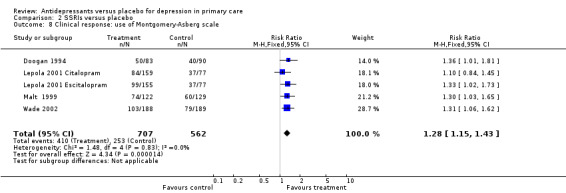

1. Clinical response at post‐treatment (Analysis 2.1) There were four studies with dichotomous outcomes in this comparisons. One study examined two medications, Escitalopram and Citalopram (Lepola 2001 CitalopramLepola 2001 Escitalopram). The relative risk for benefit was 1.28, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.43.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical response at post‐treatment.

Secondary outcomes

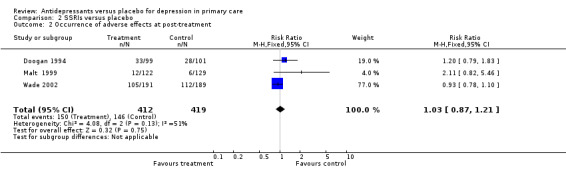

1. Occurrence of adverse effects at post treatment (Analysis 2.2) Adverse effects did not necessarily cause withdrawal from the study for patients on SSRIs. The relative risk for harm was 1.08, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.22.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 2 Occurrence of adverse effects at post‐treatment.

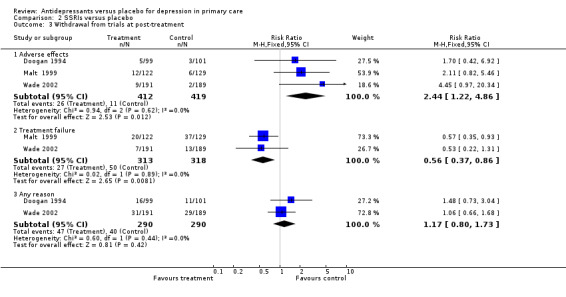

2. Withdrawal from trials at post treatment (Analysis 2.3) For withdrawal due to adverse effects for patients on SSRIs, the relative risk for harm was 2.05, 95% CI 1.11 to 3.75.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 3 Withdrawal from trials at post‐treatment.

For withdrawal due to treatment failure for patients on SSRIs, reported as a reduction in effect and hence a positive result, suggesting more treatment failure in the placebo group is reported as a relative risk less than one, the relative risk was 0.51, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.78.

For withdrawal due to any reason for patients on SSRIs, the relative risk was 1.02, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.44.

3. Ecomomic outcomes No studies contributed data to this outcome

Subgroup analyses

1. Dosage of SSRIs No subgroup analyses were performed due to lack of studies

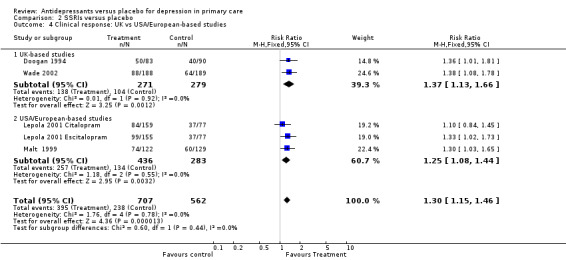

2. UK versus USA/European studies (Analysis 2.4) For UK trials, the relative risk for benefit was 1.37, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.66. For USA/European studies, the relative risk for benefit was 1.25, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.44.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 4 Clinical response: UK vs USA/European‐based studies.

Sensitivity analyses

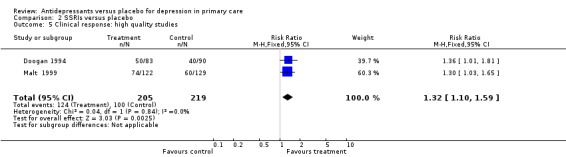

1. High quality studies (Analysis 2.5) The relative risk for benefit for high quality studies only was 1.32, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.59.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 5 Clinical response: high quality studies.

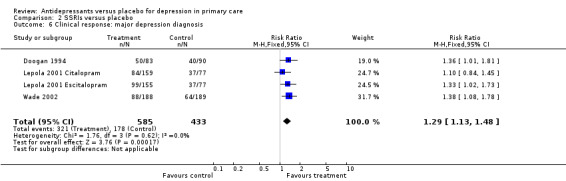

2. Major depression diagnosis (Analysis 2.6) For studies in which patients had a diagnosis of major depression, the relative risk for benefit was 1.29, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.48.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 6 Clinical response: major depression diagnosis.

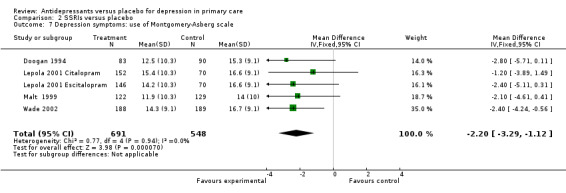

3. Use of different depression scales Reduction in depression symptoms (Analysis 2.7) For the Montgomery‐Asberg scale, standard deviations were only available for the Malt study so those SDs were used for the other studies. The SMD was ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐0.35 to ‐0.12.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 7 Depression symptoms: use of Montgomery‐Asberg scale.

Clinical response (Analysis 2.8) For the Montgomery‐Asberg scale(remission or improved), the relative risk for benefit was 1.27, 95% 1.11 to 1.45).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SSRIs versus placebo, Outcome 8 Clinical response: use of Montgomery‐Asberg scale.

Sensitivity analyses were not performed for approximated data, use of >50% GP assessors or studies with no competing interest.

Publication bias Results from the funnel plot showed that small studies with no effect were missing from the graph (Figure 1). This may reflect some publication bias as such studies can be difficult to get published.

Summary of main results: NNT and NNH The numbers needed to treat (NNT) for TCAs ranged from 7 to 16 {median NNT 9} patient expected event rate ranged from 63% to 26% respectively) and for SSRIs from 7 to 8 {median NNT 7} (patient expected event rate ranged from 48% to 42% respectively) . The numbers needed to harm (NNH for withdrawal due to side effects) ranged from 4 to 30 for TCAs (excluding three studies with no harmful events leading to withdrawal) and 20 to 90 for SSRIs.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The review included 14 studies (16 comparisons), and the results show that both TCAs and SSRIs are significantly more effective than placebo for both discrete and continuous outcomes. Such analyses were significant whether the GPs were 50% or more of the assessors, the studies were UK or Europe/US‐based, and where the Hamilton depression scale was used, but not the Montgomery‐Asberg scale. For TCAs, the results were also positive when analyses included studies that had remission as an outcome or a Hamilton score of less than 8 as a marker of remission, and where no commercial backing for the study was reported. The only analyses which were not statistically significant were those for low quality studies and for response after one, two and threes weeks of tricyclic antidepressants. The responses were statistically significant for four weeks after starting therapy. The results were also positive for the pooling of those studies that had doses of tricyclic antidepressants at or under 100mg per day. The numbers needed to treat to get an improvement was 6 to 16 for the TCAs (median NNT 9) and 7 to 8 for the SSRIs (median NNT 7). These findings are comparable to other treatments in primary care and likely to be acceptable to most primary care clinicians. The results apply to major depressive disorder and heterogeneous depression (commonly seen in primary care).

Adverse effects were statistically higher than placebo for both tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs except for withdrawal for any reason. Withdrawal due to treatment failure was statistically greater in the placebo group than the medication group for both classes of medication. This is consistent with the evidence for effectiveness.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The review included studies with a range of depressed patients. One TCA study included only patients with major depressive disorder (Barge‐Schaapveld 2002). Two studies of SSRIs included only patients with major depressive disorder (Lepola 2001 Citalopram; Lepola 2001 Escitalopram; Wade 2002), as did one study with both TCA and SSRI arms (Doogan 1994). As patients in primary care settings have a range of depression severity the generalisability of the results of these studies to primary care is reasonable (Arroll 2002). Only one study conducted an analysis of minor depression and this found that amitriptyline was superior to placebo in probable or definite major depression on the Research Diagnostic Criteria, but not in minor depression (Paykel 1988) Amitriptyline was also superior to placebo in subjects with initial scores on the Hamilton Depression Scale of 13‐15, and 16 or more, but not with lower scores. The Paykell study (Hollyman 1988) indicates that tricyclic antidepressants are of considerable benefit in relatively mild depressive disorders, except in the mildest range.

Quality of the evidence

There has been an issue that studies in primary care populations may only benefit from antidepressant medication when it is given by a psychiatrist. Our significant findings for continuous and discrete outcomes contradict this. There is evidence in this review that both TCAs and SSRIs are more effective than placebo in the primary care setting. This needs to be tempered with the knowledge that there may be some publication bias and that many of the studies were small and of variable quality.

The majority of systematic reviews concerning antidepressant efficacy fail to report a detailed examination of methodological quality and therefore fail to include such criteria when examining treatment effects. This is important because bias in primary studies due to poor methodological quality (e.g. selection bias, ascertainment bias, inappropriate handling of withdrawals, protocol violations) can lead to exaggeration of treatment effects. A study of trial quality in systematic reviews showed that if low quality studies were included in pooled estimates of treatment effect there was a 30‐50% exaggeration of treatment effectiveness (Moher 1999). We did not however, find any appreciable differences between effects for the high quality studies compared with the lower quality studies other than a non‐significant result for clinical responses in the low quality studies. Another form of bias for meta‐analysis is that of publication bias. Our funnel plot suggests that small studies with small effect sizes may be missing. This is consistent with a review of all applications to the US FDA, which examined all submitted trials of newer antidepressants. Their finding was that when all studies were considered, the benefit of antidepressants was much smaller than when only the published studies were considered (Kirsch 2002).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We found only 14 studies (16 comparisons) based in primary care that met inclusion criteria and provided evidence for the comparative efficacy of TCAs and SSRIs versus placebo. In a previous review of trials comparing SSRIs and TCAs in primary care, we similarly found relatively few studies (MacGillivray 2003). This compares with considerably larger numbers of studies conducted with patients from all settings. Williams 2000 found 206 studies comparing a newer antidepressant with an older (123 of which involved an SSRI). They found a benefit for the newer antidepressants of RR = 1.6 (95% CI 1.3 to 2.3). In a review including only studies conducted within the USA, Steffens 1997 discovered 36 trials comparing a TCA drug with an SSRI. The majority of studies included in the present review were small phase three studies supported by commercial funding. In fact all of the SSRI versus placebo studies had some commercial involvement. Many studies were of short duration, typically 6‐8 weeks. Our findings are in keeping with a review of 108 studies of newer antidepressants, which found that both TCAs and SSRIs were effective in treating depression (Anderson 2001).

Previous reviews have tended to show that SSRIs are generally more tolerable than TCAs, although evidence is conflicting. Meta‐analyses using drop‐out rates as an index of tolerability have varied in their findings. Whilst one review (Song 1993) found no difference in drop‐out rates between SSRIs (32.3%) and TCAs (33.2%), another (Anderson 1995) found a small but statistically significant lower drop‐out rate for SSRIs (30.8%) relative to TCAs (33.4%). In our review focusing only on primary care treated samples, we found drop‐out rates due to adverse effects for SSRIs of 5.2% and TCAs of 10.2%. In another review of antidepressants in primary care the risk of withdrawal of patients due to side effects with SSRI compared with TCAs was 0.6 (95% CI 0.6‐0.88) (MacGillivray 2003). Primary care clinicians may be more likely than hospital colleagues to alter therapy when side‐effects are experienced, even during clinical trials (Simon 2002).

Our finding of a significant benefit for low dose tricyclic antidepressants (i.e. ≤ 100mg per day) is consistent with a meta‐analysis of studies in all settings which found a benefit from low dose tricyclic antidepressants (Furukawa 2002). Only one of the three studies in our review was statistically significant which suggests that larger trials are needed in the primary care setting to clarify issues such as dose of antidepressants (Thompson 1989; Blashki (75mg) 1971). The review of low dose studies found there was no evidence of increased benefit with higher doses but there was an increase in side effects. Our results were similar to that review, but the increase in adverse effects was non‐significant.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Our results suggest that treating depression with antidepressants is an appropriate activity in primary care. The evidence is clear for major depression and levels of depression greater than minor depression. Based on this evidence, tricyclic antidepressants could be considered and the dose kept at or below 100mg per day, and waiting at least 4 weeks for a response may be worth considering. Both SSRIs and TCAs appear to be tolerable, but more adverse effects can be expected with TCAs. The numbers needed to treat (NNT) are between 6 and 16 for TCAs (median NNT 9) and 7 to 8 (median NNT 7) for SSRIs. An NNT of 7 means that one patient will benefit from treatment and six will not although up to half may get better on placebo. This is true in primary care and secondary care. There is no dose information on SSRIs and we cannot comment on the appropriate duration of treatment for either TCAs or SSRIs.

Implications for research.

Gaps in the literature include a lack of attention to the treatment of specific diagnostic groups, in particular minor depression. Further research is needed on these groups of patients in addition to longer and larger trials of low dose TCAs. There is also a need for studies to be conducted by agencies other than pharmaceutical companies and to conduct studies in patients with lower levels of depression i.e. minor depression.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 April 2014 | Amended | Search updated to 2013, two possible new studies identified but not fully incorporated. |

History

Review first published: Issue 3, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 24 September 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The original work for this review was funded by a grant from the Chief Scientist Office (Scotland)

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search of the CCDANCTR‐Studies Register to 2007

CCDANCTR‐Studies ‐ searched on 24 September 2007 Intervention = (Antidepress* or "Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors" or "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors" or "Tricyclic Drugs" or Acetylcarnitine or Alaproclate or Amersergide or Amiflamine or Amineptine or Amitriptyline or Amoxapine or Befloxatone or Benactyzine or Brofaromine or Bupropion or Butriptyline or Caroxazone or Chlorpoxiten or Cilosamine or Cimoxatone or Citalopram or Clomipramine or Clorgyline or Clorimipramine or Clovoxamine or Deanol or Demexiptiline or Deprenyl or Desipramine or Dibenzipin or Diclofensine or Dothiepin or Doxepin or Duloxetine or Escitalopram or Etoperidone or Femoxetine or Fluotracen or Fluoxetine or Fluparoxan or Fluvoxamine or Idazoxan or Imipramine or Iprindol* or Iproniazid or isocarboxazid or Litoxetin* or Lofepramin* or Maprotilin* or Medifoxamin* or Melitracen or Metapramin* or Mianserin or Milnacipran or Minaprin* or Mirtazapin* or Moclobemid* or Nefazodon* or Nialamid* or Nomifensin* or Nortriptylin* or Noxiptilin* or Opipramol or Oxaflozan* or Oxaprotilin* or Pargylin* or Paroxetin* or Phenelzin* or Piribedil or Pirlindol* or Pivagabin* or Prosulprid* or Protriptylin* or Quinupramin* or Reboxetin* or Rolipram or Sertralin* or Setiptilin* or Teniloxin* or Tetrindol* or Thiazesim or Thozalinon* or Tianeptin* or Toloxaton* or Tomoxetin* or Tranylcypromin* or Trazodon* or Trimipramin* or Venlafaxin* or Viloxazin* or Viqualin* or Zimeldin*) And Intervention = Placebo* And Diagnosis = (Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder" or "Affective Symptoms") And Setting = ("General Practice" or "Primary Care" or "Community Mental Health" or "Family Practice" or "Health Maintenance Organization" or HMO or Home or "University Clinic" or Private or Ambulatory) And Age Group = Adult

Appendix 2. Search of the CCDANCTR‐References Register to 2007

CCDANCTR‐References ‐ searched on 24 September 2007 Free‐text = (Antidepress* or "Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors" or "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors" or "Tricyclic Drugs" or Acetylcarnitine or Alaproclate or Amersergide or Amiflamine or Amineptine or Amitriptyline or Amoxapine or Befloxatone or Benactyzine or Brofaromine or Bupropion or Butriptyline or Caroxazone or Chlorpoxiten or Cilosamine or Cimoxatone or Citalopram or Clomipramine or Clorgyline or Clorimipramine or Clovoxamine or Deanol or Demexiptiline or Deprenyl or Desipramine or Dibenzipin or Diclofensine or Dothiepin or Doxepin or Duloxetine or Escitalopram or Etoperidone or Femoxetine or Fluotracen or Fluoxetine or Fluparoxan or Fluvoxamine or Idazoxan or Imipramine or Iprindol* or Iproniazid or isocarboxazid or Litoxetin* or Lofepramin* or Maprotilin* or Medifoxamin* or Melitracen or Metapramin* or Mianserin or Milnacipran or Minaprin* or Mirtazapin* or Moclobemid* or Nefazodon* or Nialamid* or Nomifensin* or Nortriptylin* or Noxiptilin* or Opipramol or Oxaflozan* or Oxaprotilin* or Pargylin* or Paroxetin* or Phenelzin* or Piribedil or Pirlindol* or Pivagabin* or Prosulprid* or Protriptylin* or Quinupramin* or Reboxetin* or Rolipram or Sertralin* or Setiptilin* or Teniloxin* or Tetrindol* or Thiazesim or Thozalinon* or Tianeptin* or Toloxaton* or Tomoxetin* or Tranylcypromin* or Trazodon* or Trimipramin* or Venlafaxin* or Viloxazin* or Viqualin* or Zimeldin*) And Free‐text= Placebo* And Keyword = (Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder" or "Affective Symptoms") And Free‐text = ("General Practice" or "Primary Care" or "Community Mental Health" or "Family Practice" or "Health Maintenance Organization" or HMO or Home or "University Clinic" or Private or Ambulatory)

Appendix 3. Update CCDANCTR Search (Studies and References Register) carried out in 2013

#1. (antidepress* or anti‐depress* or "anti depress*" or MAOI* or RIMA* or “monoamine oxidase inhibit*” or ((serotonin or norepinephrine or noradrenaline or neurotransmitter* or dopamin*) NEAR (uptake or reuptake or re‐uptake or "re uptake")) or SSRI* or SNRI* or NARI* or SARI* or NDRI* or TCA* or tricyclic* or tetracyclic*)

#2. (Agomelatine or Alaproclate or Amoxapine or Amineptine or Amitriptylin* or Amitriptylinoxide or Atomoxetine or Befloxatone or Benactyzine or Binospirone or Brofaromine or (Buproprion or Amfebutamone) or Butriptyline or Caroxazone or Cianopramine or Cilobamine or Cimoxatone or Citalopram or (Chlorimipramin* or Clomipramin* or Chlomipramin* or Clomipramine) or Clorgyline or Clovoxamine or (CX157 or Tyrima) or Demexiptiline or Deprenyl or (Desipramine* or Pertofrane) or Desvenlafaxine or Dibenzepin or Diclofensine or Dimetacrin* or Dosulepin or Dothiepin or Doxepin or Duloxetine or Desvenlafaxine or DVS‐233 or Escitalopram or Etoperidone or Femoxetine or Fluotracen or Fluoxetine or Fluvoxamine or (Hyperforin or Hypericum or “St John*”) or Imipramin* or Iprindole or Iproniazid* or Ipsapirone or Isocarboxazid* or Levomilnacipran or Lofepramine* or (“Lu AA21004” or Vortioxetine) or "Lu AA24530" or (LY2216684 or Edivoxetine) or Maprotiline or Melitracen or Metapramine or Mianserin or Milnacipran or Minaprine or Mirtazapine or Moclobemide or Nefazodone or Nialamide or Nitroxazepine or Nomifensine or Norfenfluramine or Nortriptylin* or Noxiptilin* or Opipramol or Oxaflozane or Paroxetine or Phenelzine or Pheniprazine or Pipofezine or Pirlindole or Pivagabine or Pizotyline or Propizepine or Protriptylin* or Quinupramine or Reboxetine or Rolipram or Scopolamine or Selegiline or Sertraline or Setiptiline or Teciptiline or Thozalinone or Tianeptin* or Toloxatone or Tranylcypromin* or Trazodone or Trimipramine or Venlafaxine or Viloxazine or Vilazodone or Viqualine or Zalospirone)

#3. (#1 or #2)

#4. placebo*

#5. (#3 and #4)

#6. (depress* or dysthymi* or "adjustment disorder*" or "mood disorder*" or "affective disorder" or "affective symptoms"):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mc,mh

#7. (#5 and #6)

#8. (primary NEAR2 (care or health*))

#9. (family or general or community) NEAR2 (medic* or doctor* or physician* or practi* or health*)

#10. (GP or “GP’s”):ab

#11. (community NEAR2 (care or health*))

#12. “health maintenance organization" or HMO or home

#13. "university clinic" or “health cent*” or private or ambulatory

#14. (#8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13)

#15. (#7 and #14)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. TCAs versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Depression symptoms at post‐treatment | 13 | 1233 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.49 [‐0.67, ‐0.32] |

| 2 Clinical response at post‐treatment | 8 | 1058 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.11, 1.38] |

| 3 Occurrence of adverse effects at post‐treatment | 10 | 1015 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.59, 2.55] |

| 4 Withdrawal from trials at post‐treatment | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Adverse effects | 11 | 1187 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.14 [1.41, 3.26] |

| 4.2 Treatment failure | 8 | 769 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.27, 0.58] |

| 4.3 Any reason | 11 | 1027 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.84, 1.24] |

| 5 Depression symptoms: 1‐4 week timepoints | 9 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 1 week | 8 | 691 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.59, 0.18] |

| 5.2 2 weeks | 6 | 627 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.24 [‐0.62, 0.14] |

| 5.3 3 weeks | 5 | 464 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.38 [‐1.01, 0.26] |

| 5.4 4 weeks | 9 | 705 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.50 [‐0.78, ‐0.23] |

| 6 Clinical response: 1‐4 week timepoints | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 2 weeks | 3 | 304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.78 [0.87, 3.64] |

| 6.2 4 weeks | 3 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.66 [0.75, 3.70] |

| 7 Depression symptoms: dosage of TCAs | 13 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 >100mg per day | 10 | 1028 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.50 [‐0.71, ‐0.29] |

| 7.2 ≤100mg per day | 3 | 223 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.51 [‐0.80, ‐0.22] |

| 7.3 ≤75 mg per day | 2 | 72 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.31 [‐0.78, 0.16] |

| 8 Clinical response: dosage of TCAs | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 >100mg per day | 7 | 907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [1.13, 1.44] |

| 9 Depression symptoms: UK vs USA/European‐based studies | 11 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 UK‐based studies | 6 | 607 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.83 [‐3.32, ‐0.34] |

| 9.2 USA or European‐based studies | 5 | 581 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.82 [‐3.61, ‐2.03] |

| 10 Clinical response: UK vs USA/European‐based studies | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 UK‐based studies | 5 | 574 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.11, 1.49] |

| 10.2 USA or European‐based studies | 3 | 484 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.00, 1.40] |

| 11 Depression symptoms: approximated vs non‐approximated data | 13 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 11.1 Approximated data | 7 | 886 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.46 [‐0.73, ‐0.18] |

| 11.2 Non‐approximated data | 6 | 347 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.39 [‐0.79, 0.01] |

| 12 Clinical response: approximated vs non‐approximated data | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 Approximated data | 5 | 660 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.12, 1.46] |

| 12.2 Non‐approximated data | 3 | 398 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.96, 1.42] |

| 13 Depression symptoms: high vs low quality studies | 13 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 13.1 High quality studies | 7 | 757 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐0.80, ‐0.41] |

| 13.2 Low quality studies | 6 | 486 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.35 [‐0.63, ‐0.07] |

| 14 Clinical response: high vs low quality studies | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 High quality studies | 5 | 721 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [1.14, 1.51] |

| 14.2 Low quality studies | 3 | 337 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.94, 1.32] |

| 15 Depression symptoms: major depression diagnosis | 2 | 235 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.37 [‐2.52, ‐0.22] |

| 16 Depression symptoms: use of different depression scales | 13 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 16.1 Montgomery‐Asberg scale | 3 | 585 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.24 [‐2.90, 0.42] |

| 16.2 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | 10 | 648 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.17 [‐3.94, ‐2.39] |

| 16.3 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for scores <8 | 4 | 222 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.38 [‐4.48, ‐2.29] |

| 17 Clinical response: greatly improved/remission | 5 | 752 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.11, 1.50] |

| 18 Depression symptoms: 50% or more GP assessors | 7 | 765 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.48 [‐0.62, ‐0.33] |

| 19 Clinical response: 50% or more GP assessors | 5 | 684 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.03, 1.39] |

| 20 Depression symptoms: studies with no competing interest | 6 | 363 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.68 [‐0.90, ‐0.47] |

| 21 Clinical response: studies with no competing interest | 3 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.59 [1.28, 1.96] |

Comparison 2. SSRIs versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical response at post‐treatment | 5 | 1269 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.15, 1.43] |

| 2 Occurrence of adverse effects at post‐treatment | 3 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.87, 1.21] |

| 3 Withdrawal from trials at post‐treatment | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Adverse effects | 3 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.44 [1.22, 4.86] |

| 3.2 Treatment failure | 2 | 631 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.37, 0.86] |

| 3.3 Any reason | 2 | 580 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.80, 1.73] |

| 4 Clinical response: UK vs USA/European‐based studies | 5 | 1269 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.15, 1.46] |

| 4.1 UK‐based studies | 2 | 550 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [1.13, 1.66] |

| 4.2 USA/European‐based studies | 3 | 719 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.08, 1.44] |

| 5 Clinical response: high quality studies | 2 | 424 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.10, 1.59] |

| 6 Clinical response: major depression diagnosis | 4 | 1018 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.13, 1.48] |

| 7 Depression symptoms: use of Montgomery‐Asberg scale | 5 | 1239 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.20 [‐3.29, ‐1.12] |

| 8 Clinical response: use of Montgomery‐Asberg scale | 5 | 1269 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.15, 1.43] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Barge‐Schaapveld 2002.

| Methods | Imipramine vs placebo randomised controlled trial (RCT) in eight primary care practices in Netherlands | |

| Participants | N = 63. Imipramine group n=32; Placebo group n=31. Inclusion criteria: Age 18‐65 years. DSM‐III‐R/DSM‐IV diagnosis of current depressive disorder. Equal or greater than 18 on 17‐item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) and a score of equal or greater than 4 on Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI) Exclusion criteria: on psychotropics or major medical disorder. | |

| Interventions | 50 mg Imipramine per day increasing to over 200 mg per day after 1 week. Duration 6 weeks with a subsample going to 18 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | 10 withdrew due to adverse effects: 6 on Imipramine and 4 on placebo. Results at 6 weeks: Imipramine group n=23, HAMD mean=8.9 (SD 6.2), Placebo n=26, HAMD mean=12.5 (SD 6.3) | |

| Notes | Not clear who administered medication and outcome check list | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Blashki (150 mg) 1971.

| Methods | Amitriptyline vs Amylobarbitone vs placebo RCT involving 21 GPs in Melbourne over a 6 month period | |

| Participants | N = 82. Inclusion criteria: Women over 15 years (mean age 37.7), persistent lower mood with depressive symptoms; sleep and appetite disturbances, loss of interest, inability to concentrate. Mean baseline HAMD = 17.4 (SD4.9) Exclusion criteria: organic brain disorder, schizophrenia, epilepsy, alcoholism and mental retardation. | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 150 mg per day, amylobarbitone 150 mg/day and placebo for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | 23 drop outs. (82 started, 61 analysed) Results at 28 days: Amitriptyline 75mg n=13, HAMD mean=6.4 (SD 5.4), vs Amitriptyline 150 mg n=14, HAMD mean=5.1 (SD 4.9) vs Placebo n=18, HAMD mean=11.4 (SD 9.6) At one week: Amitripyline 75mg n=13, HAMD mean=11.2 (SD 3.9) vs Amitriptyline 150mg n=14, HAMD mean=7.1 (SD 4.7) vs Placebo n=18, HAMD mean=14.2 (SD 6.2) Side effects not leading to withdrawal included shakiness of legs or arms, dry mouth, blurred vision, fuzziness in the head drowsiness, restlessness, headache, pain in stomach (no difference between groups). Adverse effects leading to withdrawal (11/82): Amitriptyline 75mg/day (4), Amitriptyline 150mg/day (3), Placebo (4) | |

| Notes | Amitriptyline versus placebo. Saw a psychiatrist for medication but also saw their GP during 4 weeks of study. Considered as being conducted by a psychiatrist | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Blashki (75mg) 1971.

| Methods | Amitriptyline vs Amylobarbitone vs placebo RCT involving 21 GPs in Melbourne over a 6 month period | |

| Participants | N = 82. Inclusion criteria: Women over 15 years (mean age 37.7), persistent lower mood with depressive symptoms; sleep and appetite disturbances, loss of interest, inability to concentrate. Mean baseline HAMD = 17.4 (SD4.9) Exclusion criteria: organic brain disorder, schizophrenia, epilepsy, alcoholism and mental retardation. | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 75 mg per day, amylobarbitone 150 mg/day and placebo for 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | 23 drop outs. (82 started, 61 analysed) Results at 28 days: Amitriptyline 75mg n=13, HAMD mean=6.4 (SD 5.4), vs Amitriptyline 150 mg n=14, HAMD mean=5.1 (SD 4.9) vs Placebo n=18, HAMD mean=11.4 (SD 9.6) At one week: Amitripyline 75mg n=13, HAMD mean=11.2 (SD 3.9) vs Amitriptyline 150mg n=14, HAMD mean=7.1 (SD 4.7) vs Placebo n=18, HAMD mean=14.2 (SD 6.2) Side effects not leading to withdrawal included shakiness of legs or arms, dry mouth, blurred vision, fuzziness in the head drowsiness, restlessness, headache, pain in stomach (no difference between groups). Adverse effects leading to withdrawal (11/82): Amitriptyline 75mg/day (4), Amitriptyline 150mg/day (3), Placebo (4) | |

| Notes | Amitriptyline versus placebo. Saw a psychiatrist for medication but also saw their GP during 4 weeks of study. Considered as being conducted by a psychiatrist | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Brink 1984.

| Methods | Mianserin vs placebo RCT Patients from a representative Dutch general practice | |

| Participants | N =52. Patients aged 18‐65 years with a diagnosis of depressive disorder according to the Medical Research Council criteria: persistent alteration of mood which exceeded customary sadness accompanied by one or more of following: self deprecation with a morbid sense of guilt, sleep disturbance, hypochondriasis with psychomotor retardation or agitation. Mianserin n=27, placebo n=25 Exclusion: major illness, ECT or antidepressants in previous 6 months. Only 3 patients in each group had HAMD scores <17 | |

| Interventions | Mianserin 3 x 10 mg nightly increasing to 6x nightly or matching placebo. Could have oxazepam as a hypnotic. Duration 4 weeks | |

| Outcomes | 29% (15) drop outs. 9 from Mianserin and 6 placebo. Intention to treat if stayed in trial up to 15 days: N=24 in mianserin and 25 in placebo group. At day 28: Mianserin group HAMD mean 8.8 (SD 7.3) vs Placebo HAMD mean 11.1 (SD 6.9). Mianserin effect was significant at day 7: Mianserin group N=26, HAMD mean 14.9, (SD 3.8) vs Placebo N=25 HAMD mean 17.6 (SD 6.0) at day 7. At day 14: Mianserin group N=24 HAMD mean 12.1 (SD 6.8) vs N=25, HAMD mean 14.1 (SD 7.0) for Placebo. At day 21: Mianserin group N=24, HAMD mean 10.9 (SD 7.7) vs N=25 HAMD mean 11.8 (SD 6.9) for Placebo. Clinical global impression score at baseline: Mianserin group mean 2.7 at day 0 and at day 28 mean 1.1 and for placebo at day 0 mean 2.8 and at day 28 mean 1.6. Global improvement score: Mianserin at day 28 mean was 2.0 and placebo 1.3 (P<0.05). | |

| Notes | Tetracyclic study. Low powered study. Medication and assessments done by GPs | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Doogan 1994.

| Methods | Sertraline vs dothiepin vs placebo. Randomised controlled trial Country: UK Not sure how GPs were chosen | |

| Participants | N=308 patients randomized. Primary major depressive disorder according to DSM III‐R aged over 18 years and have a score of 22 or more on MADRS and a severity score of 4 or more on the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI). Exclusions >35 on MADRS, risk of suicide, pregnancy, lactation, significant physical illness, mania, benign prostatic hypertrophy, treatment with certain antihypertensive agents, antihistamines or sympathomimetic, lithium in past 3 months, resistant depression (i.e. had 8 or more weeks with medication or had an episode lasting over 1 year), schizophrenia or organic brain disease, epilepsy, other psychotropic medications | |

| Interventions | 7‐14 days of single blind run in. Sertaline 50 mg and dothiepin 75mg for 14 days then double dose if possible for 6 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | 13% (39) not evaluable. At day 42: for sertraline group MADRS mean 12.5 (SD not reported) n=83 vs dothiepin mean 14.2 (SD 4.5) n=96 and placebo mean 15.3 (SD not reported) n=90. SDs were not reported but SDs from Malt 1999 were used in analysis. The proportion responding (i.e.: => 50% reduction in MADRS) Sertraline=50/83 (60.2%), Dothiepin =48/96 (50%) & placebo 40/90 (44%). Median dose of sertraline was 50 mg and 150 mg of dothiepin. Side effects: (mainly in central nervous system, peripheral nervous system and GI system) 33/99 Sertraline, 32/108 Dothiepin and placebo 28/101. Adverse effects leading to withdrawal: 5/99 for sertraline 2/108 on dothiepin and 3/101 on placebo. Treatment withdrawal for any reason: Sertraline 16/99 Dothiepin 12/108 Placebo 11/101 | |

| Notes | Analysis was intention to treat after 1st return visit. GPs did the assessments and medication handling | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Feighner 1979.

| Methods | Amitriptyline vs placebo RCT from 4 physicians in private practice in USA + 2 other university clinics | |

| Participants | N=337 patients. 30% male. Mean age 40.2 yrs. Criteria of Feighner 1972 dysphoric mood + 5 of poor appetite, weight loss, loss of energy, agitation or retardation, loss of interest, diminished sexual drive, self reproach or guilt, poor concentration and thoughts of death or suicide. Also > 20 on HAMD, >14 on short Beck and >8 on Covi scale. Exclusions: schizophrenia, alcoholism, hysteria, antisocial personality, serious medical risks, no recent ECT or MAOI or tricyclic or tranquilliser within 5 days. 143 were unipolar and 33 bipolar. 161 not classified | |

| Interventions | Amitriptyline 25mg 4 tablets to start increasing to 5 or 6 tabs over 4 weeks. Same for placebo. Assessment was by a psychiatrist | |