Abstract

Background

Over the past decade, treatment targets for ulcerative colitis (UC) have become more stringent, incorporating multiple parameters. Recently, the concept of ‘disease clearance’—defined as combined clinical, endoscopic, and histological remission—has been proposed as an ultimate endpoint in treating UC.

Objective

To determine the rates of disease clearance in patients with mild‐to‐moderate UC treated with different doses of mesalazine granules as induction therapy.

Methods

In a post hoc analysis, data were pooled from four randomised, active‐controlled, phase 3 clinical trials in patients with mild‐to‐moderate UC receiving 8‐week induction therapy with mesalazine granules at daily doses of 1.5, 3.0 or 4.5 g. Rates of clinical, endoscopic, and histological remission were determined using stringent criteria and used to calculate rates of the composite endpoints of clinical plus endoscopic remission, endoscopic plus histological remission, and disease clearance (clinical plus endoscopic plus histological remission).

Results

A total of 860 patients were included in the analysis. Among the total population, 20.0% achieved disease clearance with mesalazine granules: 13.1% in patients receiving 1.5 g mesalazine granules/day, 21.8% in those receiving 3.0 g/day and 18.9% in those receiving 4.5 g/day. Among patients with moderate UC, 16.8% achieved disease clearance: 7.1% with 1.5 g/day, 18.8% with 3.0 g/day and 16.2% with 4.5 g/day.

Conclusion

Disease clearance, proposed to be predictive of improved long‐term outcomes, can be achieved in a clinically meaningful proportion of mild‐to‐moderate UC patients treated with mesalazine granules. A daily dose of 3.0 g appears optimal to reach this target.

Keywords: clinical remission, disease clearance, endoscopic remission, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, mesalazine, Ulcerative Colitis

Key summary.

Summarise the established knowledge on this subject

Mesalazine remains the mainstay treatment for patients with mild‐to‐moderate ulcerative colitis (UC).

As a long‐established effective therapy, few studies have been conducted to date on the ability of mesalazine treatment to achieve modern treatment targets.

The concept of disease clearance has recently been proposed as the ultimate treatment target for UC.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

Modern composite treatment targets can be achieved with mesalazine granule induction therapy.

Disease clearance was achieved by up to 21.8% of patients, including 18.8% of patients with moderate UC.

3.0 g/day appears to be the optimal dose for disease clearance.

INTRODUCTION

While the primary goal in ulcerative colitis (UC) treatment originally focused on resolving patients' symptoms, the past decade has seen the increasing use of treatment targets which incorporate more objective parameters in both routine practice and as endpoints in clinical trials. This shift has been spurred in large part by the advent of biologics in UC treatment, which has heralded the promise of improved long‐term prognoses in addition to acute flare management. Initial studies demonstrated that endoscopic remission or ‘endoscopic healing’—defined as the resolution of endoscopically visible disease activity—was associated with improved long‐term outcomes such as lower need for corticosteroids or colectomy. 1 As a result, the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Disease (STRIDE) committee in 2015 recommended a treat‐to‐target strategy incorporating not only clinical remission but also endoscopic remission for UC, 2 a state frequently termed ‘deep remission’. 3

More recently, evidence has been mounting that histological improvement may be an independent predictor of long‐term UC outcomes 4 and may even predict complications such as hospitalisation and corticosteroid use better than endoscopic remission. 5 Despite a dearth of validated histological indices, these findings have led many trialists and regulatory to incorporate composite endoscopic and histological remission as a mandatory endpoint. 6 , 7

This evolution in treatment targets culminated in the recent proposal of a ‘disease clearance’ concept for UC, which is currently defined as clinical remission plus endoscopic remission plus histological remission. 8 This state has been shown to confer long‐term absence of disease relapse and complications for other chronic inflammatory disorders, 9 and recent retrospective data suggest this may also apply to UC. 10 Despite current lack of prospective trial data, retrospective analyses suggest that the state of disease clearance is achievable for UC, albeit at low rates. 10

Although biologics and novel small molecules have received growing attention, mesalazine (5‐aminosalicylic acid [5‐ASA]) remains the gold standard in the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate UC. Indeed, 5‐ASA is recommended in multiple guidelines as first‐line therapy of various forms of mild and/or moderate UC. However, there is little information to date on the attainment of composite treatment goals in UC using 5‐ASA.

Here, we investigate rates of clinical plus endoscopic remission, endoscopic plus histological remission, and disease clearance achieved with mesalazine granules using a pooled post hoc analysis of four randomised phase 3 trials in patients with mild‐to‐moderate UC. These trials—SAG‐2, 11 SAG‐15, 12 SAG‐26 13 and BUC‐57 14 —tested the efficacy of mesalazine granules as induction therapy at different daily doses and versus alternative dosage forms or agents. Using harmonised criteria to evaluate clinical, endoscopic and histological outcomes among the trials allowed us to assemble an adequately uniform and robust patient population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial designs

This study is a pooled post hoc analysis of four prospective, randomised, double‐blind, phase 3 trials on induction therapy of mild‐to‐moderate UC using mesalazine granules (Salofalk® granules, Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH): SAG‐2, 11 SAG‐15, 12 SAG‐26 13 and BUC‐57. 14 In all four trials, mesalazine granules were administered orally in a delayed‐release formulation intended to target the drug to the colon. The studies compared dosages of mesalazine granules (1.5 vs. 3.0 vs. 4.5 g) (SAG‐2), mesalazine dosage forms (pellets vs. tablets) (SAG‐15), treatment schedules of mesalazine granules (1× vs. 3× per day) (SAG‐26), and mesalazine versus budesonide (BUC‐57). All trials were approved by the appropriate ethics committees and all patients provided written informed consent.

All four trials shared nearly identical inclusion criteria. The primary eligibility criteria were adults (18–75 years old) with UC confirmed by endoscopy and histology, with mild‐to‐moderate disease activity. This was variously defined as a Clinical Activity Index (CAI) score above 4, 13 6, 14 or between 6 and 12 11 , 12 as well as an Endoscopic Index (EI) score of ≥4 in all studies (both indexes according to Rachmilewitz 15 ). Patients with either a first attack or established disease were eligible. Key exclusion criteria included disease extent <15 cm from the anal verge, Crohn's disease, other forms of colitis, coeliac disease, malabsorption syndromes, infectious bowel diseases, abnormal renal and liver function, and immunosuppressive drugs within at least 1 month prior to baseline. All concomitant treatments for UC were to be stopped at baseline.

All patients in the respective intention‐to‐treat populations from each study who were randomised had active UC at baseline, and received at least one dose of mesalazine granules were included in the present post hoc analysis.

Endpoint evaluation

The four included studies used the same indexes to evaluate clinical, endoscopic and histological remission. To permit better comparison with contemporary measures and definitions of remission, including newer scores, we revised our prior definitions of clinical, endoscopic and histological remission to bring them more in line with current consensus, guidelines and regulatory guidance. 6 , 16 , 17 These new definitions necessitated re‐analysis of primary efficacy variables from the original publications.

Clinical efficacy was evaluated using the CAI, 15 a 23‐point index which is calculated as the sum of the scores of seven variables (number of weekly stools, bloody stools, abdominal pain, general well‐being, body temperature, extra‐intestinal manifestations and erythrocyte sedimentation rate/haemoglobin). The scores for amount of weekly stools, bloody stools, abdominal pain and general well‐being were based on data collected in patients' daily diaries during the 7 days preceding a study visit. For this post hoc analysis, clinical remission was defined more strictly as CAI ≤4 plus <18 stools/week plus absence of rectal bleeding. 18 This definition conforms to current requirements for clinical remission of normal stool frequency and no bloody stools. 17

Endoscopic remission was measured by local endoscopists using the EI, 15 a 12‐point index based on the worst affected colon segment. The scoring criteria were granularity, vascular pattern, mucosal vulnerability and mucosal integrity. For this post hoc analysis, endoscopic remission was re‐defined as EI ≤ 1. This allows only a faded/disturbed vascular pattern and excludes any granularity, friability, erosion or ulcers more in line with consensus definitions of endoscopic remission. 16 , 17

Histological analysis was performed by central reading using the Histological Index (HI) according to Riley, 19 a 4‐point index based on the most severely inflamed segment. For this post hoc analysis, histological remission was defined as HI ≤ 1. This denotes no ulceration, no acute or chronic inflammatory cells in the lamina propria/epithelium, no crypt abscesses, no mucin depletion, normal surface epithelial integrity, mild‐to‐moderate crypt architectural irregularities and no erosion, consistent with current consensus requirements for histological remission. 17

Disease clearance was defined as combined clinical, endoscopic and histological remission using the definitions described above. All endpoints were evaluated at week eight of treatment.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (up to version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc.).

For all patients as well as for patients within the moderately active subgroup, the proportions of patients achieving the pre‐specified endpoints were tabulated for each dose group. A last observation carried forward approach (LOCF) was used for all endpoints at week 8. Patients without a valid value at week 8 (LOCF) were excluded. p‐values were calculated to compare the incidences of different endpoints between daily dosage groups using Fisher's exact test. As all analyses were exploratory, no adjustments for multiplicity were performed.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 860 patients from four randomised clinical trials were included in the analysis. The number of patients from each study was as follows: 256 patients from study SAG‐2, 113 from SAG‐15, 345 from SAG‐26 and 146 from BUC‐57. Table 1 shows detailed demographic information and baseline characteristics for each dose group used in the analysis. These characteristics were comparable between all three dose groups, representing a conventional population of patients with mild‐to‐moderate UC. Mean patient age was 42.8 years (SD 13.7). The majority of patients (82.4%) had established disease for a median of 3.1 years since initial diagnosis. Roughly half of all patients had proctosigmoiditis (51.7%) followed by left‐sided UC (29.3%) and extensive colitis (19%).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (ITT population).

| Total daily dose of mesalazine granules | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 g (N = 145) | 3.0 g (N = 625) | 4.5 g (N = 90) | Total (N = 860) | |

| Female, n (%) | 74 (51) | 321 (51.4) | 45 (50) | 440 (51.2) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.3 (13.4) | 42.9 (13.7) | 43 (13.6) | 42.8 (13.7) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Current | 16 (11) | 57 (9.1) | 12 (13.3) | 85 (9.9) |

| Former | 23 (15.9) | 129 (20.6) | 28 (31.1) | 180 (20.9) |

| Never | 106 (73.1) | 439 (70.2) | 50 (55.6) | 595 (69.2) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Established diagnosis | 130 (89.7) | 501 (80.2) | 78 (86.7) | 709 (82.4) |

| New diagnosis | 15 (10.3) | 124 (19.8) | 12 (13.3) | 151 (17.6) |

| Disease course (in patients with established diagnosis), n (%) | ||||

| Continuous | 1 (0.8) | 28 (5.6) | 2 (2.6) | 31 (4.4) |

| Recurrent | 129 (99.2) | 473 (94.4) | 76 (97.4) | 678 (95.6) |

| Time since diagnosis (years), median (IQR) | 5.1 (1.1, 11.4) | 2.9 (0.3, 7.4) | 4.5 (1.3, 11) | 3.1 (0.5, 8.5) |

| Number of previous episodes (in patients with established diagnosis), mean (SD) | 6.8 (7.58) | 4.7 (5.7) | 6.8 (10.4) | 5.3 (6.8) |

| Localisation of UC, n (%) | ||||

| Proctosigmoiditis | 81 (55.9) | 320 (51.2) | 44 (48.9) | 445 (51.7) |

| Left‐sided UC | 45 (31) | 180 (28.8) | 27 (30) | 252 (29.3) |

| Extensive colitis | 19 (13.1) | 125 (20) | 19 (21.1) | 163 (19) |

| Clinical activity by CAI >8, n (%) | 42 (29) | 213 (34.1) | 37 (41.1) | 292 (34) |

| Clinical activity by CAI, mean (SD) | 7.7 (1.45) | 8 (1.9) | 8.3 (1.6) | 8 (1.8) |

| Endoscopic activity by EI, mean (SD) | 7.2 (1.8) | 7.6 (1.8) | 8.1 (2) | 7.6 (1.9) |

| Histological activity by HI, mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.6 (1) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.6 (1) |

Abbreviations: CAI, Clinical Activity Index; EI, Endoscopic Index; HI, Histological Index; IQR, interquartile range; ITT, intention‐to‐treat; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Endpoint analysis

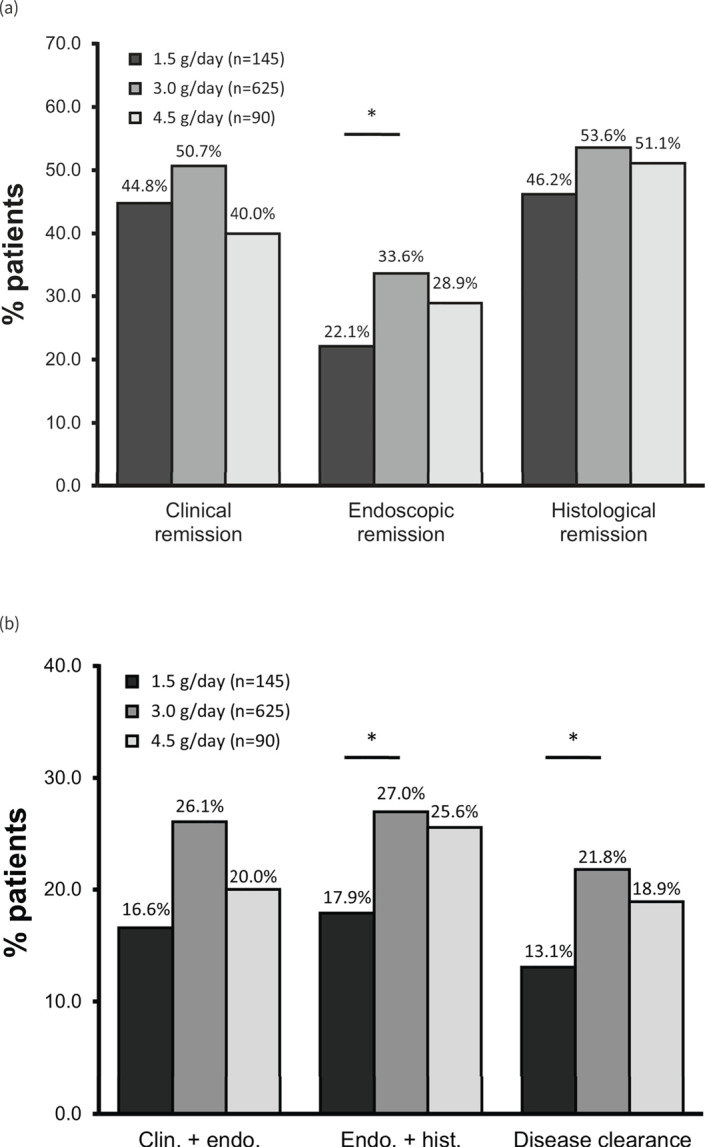

Figure 1 shows the achievement of the endpoints analysed in this study among all patients included. Overall, 48.6% of patients in the total analysis population achieved clinical remission with mesalazine granules (Figure 1a): 44.8% (65 of 145) with 1.5 g/day, 50.7% (317 of 625) with 3.0 g/day and 40.0% (36 of 90) with 4.5 g/day. Among the total population, 31.2% achieved endoscopic remission: 22.1% (32 of 145) with 1.5 g/day, 33.6% (210 of 625) with 3.0 g/day and 28.9% (26 of 90) with 4.5 g/day, with a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between 1.5 and 3.0 g/day. Finally, 52.1% achieved histological remission: 46.2% (67 of 145) in the 1.5 g/day group, 53.6% (335 of 625) in the 3.0 g/day group and 51.1% (46 of 90) in the 4.5 g/day group. [Correction added on 3 October 2023, after first online publication: In the preceding sentence, the value 55.1 has been changed to 51.1 in this version.]

FIGURE 1.

(a) Achievement of clinical, endoscopic and histological remission and (b) composite endpoints in patients with mild‐to‐moderate ulcerative colitis (ITT population). ‘Clin. + endo.’ = clinical + endoscopic remission; ‘Endo. + hist.’ = endoscopic + histological remission; ‘Disease clearance’ = clinical + endoscopic + histological remission (see Materials and methods for scoring criteria). *p < 0.05. ITT, intention‐to‐treat. [Correction added on 14 October 2023, after first online publication: Figure 1b has been updated.]

We then calculated the rates of composite endpoints reported to be associated with improved outcomes compared with the constituent endpoints alone. 3 , 20 Combined clinical plus endoscopic remission was achieved by 23.8% of the total population (Figure 1b): 16.6% (24 of 145) with 1.5 g/day, 26.1% (163 of 625) with 3.0 g/day and 20.0% (18 of 90) with 4.5 g/day, with a statistically significant difference between 1.5 and 3.0 g/day. Histological plus endoscopic remission was achieved by 25.3% of the total population: 17.9% (26 of 145) of patients receiving 1.5 g mesalazine/day, 27.0% (169 of 625) receiving 3.0 g/day and 25.6% (23 of 90) receiving 4.5 g/day, with a statistically significant difference between the 1.5 and 3.0 g groups.

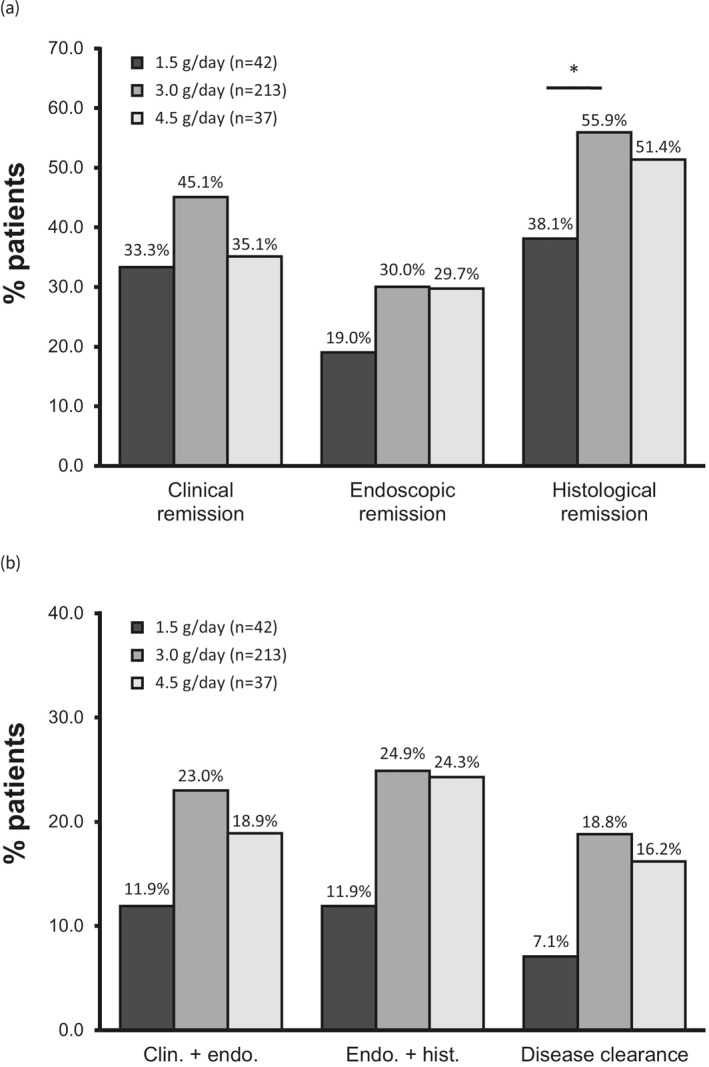

As the total population in the analysis included patients with both mild and moderate UC, we also calculated the rates of endpoint achievement among patients with moderate disease (n = 292), defined as a CAI greater than 8 (Figure 2). Among these patients, 42.1% achieved clinical remission (Figure 2a): 33.3% (14 of 42) with 1.5 g mesalazine granules/day, 45.1% (96 of 213) with 3.0 g/day and 35.1% (13 of 37) with 4.5 g/day. 28.4% achieved endoscopic remission: 19.0% (8 of 42) with 1.5 g/day, 30.0% (64 of 213) with 3.0 g/day and 29.7% (11 of 37) with 4.5 g/day. Finally, 52.7% achieved histological remission: 38.1% (16 of 42) in the 1.5 g/day group, 55.9% (119 of 213) in the 3.0 g/day group and 51.4% (19 of 37) in the 4.5 g/day group, with a statistically significant difference between 1.5 and 3.0 g/day.

FIGURE 2.

(a) Achievement of clinical, endoscopic and histological remission and (b) composite endpoints in ulcerative colitis patients with at least moderate (Clinical Activity Index >8) disease activity (ITT population). *p < 0.05. ITT, intention‐to‐treat.

Among patients with moderate UC, 20.9% achieved combined clinical plus endoscopic remission (Figure 2b): 11.9% (5 of 42) with 1.5 g mesalazine granules/day, 23.0% (49 of 213) with 3.0 g/day and 18.9% (7 of 37) with 4.5 g/day. The rate of combined endoscopic plus histological remission among patients with moderate UC was 22.9%: 11.9% (5 of 42) with 1.5 g/day, 24.9% (53 of 213) with 3.0 g/day and 24.3% (9 of 37) with 4.5 g/day.

Disease clearance

Disease clearance has prospectively been defined as combined clinical, endoscopic and histological remission. 8 Among the total population in the analysis, 20.0% of patients achieved disease clearance: 13.1% (19 of 145) of patients receiving 1.5 g mesalazine granules/day, 21.8% (136 of 625) of those receiving 3.0 g/day and 18.9% (17 of 90) of those receiving 4.5 g/day, with a statistically significant difference between 1.5 and 3.0 g/day. Among patients with moderate UC, 16.8% achieved disease clearance: 7.1% (3 of 42) with 1.5 g/day, 18.8% (40 of 213) with 3.0 g/day and 16.2% (6 of 37) with 4.5 g/day. Furthermore, an exploratory subgroup analysis revealed a 25.2% (38 of 151) rate of disease clearance for patients with new‐onset UC versus 18.9% (134 of 709) for patients with established disease.

DISCUSSION

In this post hoc analysis of four randomised controlled phase 3 trials, we show that stringent criteria for disease remission and composite treatment targets, including the emerging target of disease clearance, can be achieved in mild‐to‐moderate UC with oral mesalazine granules. These effects were robust and consistent across disease activity and mesalazine dosage, and also appear to be dose‐dependent, with 3.0 g per day likely the optimal dose. This finding is consistent with prior dose‐ranging studies on oral mesalazine granules, which also identified 3.0 g/day as the optimal dose for clinical improvement, which may be linked to mucosal metabolism. 11

Although biologics and novel small molecules have garnered considerable attention in UC research in recent years, mesalazine and other 5‐ASA drugs remain the backbone for the treatment of mild‐to‐moderate disease. 21 The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend 5‐ASA as the first‐line therapy for induction of remission in mild UC and as an effective option for moderate UC. 22 Similarly, the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines 23 consider oral 5‐ASA to be the standard therapy for inducing remission in mild‐to‐moderate UC.

At the same time, the introduction of new treatment options has raised the efficacy expected of all UC treatment modalities, resulting in more stringent definitions of fundamental endpoints such as clinical, endoscopic and histological remission. While this increase in stringency reflects an encouraging improvement in expectations for patient care, it also hampers comparisons with the historical literature. In particular, many of the key studies demonstrating the efficacy of mesalazine, including the studies included in this analysis, utilised assessment scales whose usage has since been overtaken by other measures. 24 While this is a testament to the proven efficacy of mesalazine, it also required us to re‐define remission criteria according to these legacy indexes more strictly in order to align them as closely as possible with contemporary definitions of remission (see Methods section for details).

The STRIDE II consensus 17 requires normalisation of stool frequency and absence of rectal bleeding for a definition of clinical remission. We operationalised these criteria as CAI ≤4 plus <18 stools/week plus absence of rectal bleeding, under which clinical remission was achieved by nearly half of all patients (45.1%) with moderate UC receiving 3.0 g/day mesalazine. Similarly, STRIDE II and other consensus guidelines 16 , 17 define endoscopic remission (or endoscopic healing) as a lack of significant inflammation during endoscopy. Our criteria of EI ≤ 1 implements this target by excluding all bleeding, erosion and ulcers, yielding promising rates of 30% endoscopic remission for patients with moderate UC receiving 3.0 g/day.

Evidence has also been mounting that histological remission may be an even better predictor of long‐term outcomes, including lower relapse rates, corticosteroid‐free survival and lower cancer risk. 5 , 25 , 26 Interestingly, histological remission appears to be independent of endoscopic remission, as patients with normal endoscopy may still have microscopic signs of disease and are more likely to have symptoms of UC than patients with histological remission. 27 , 28 We used a Riley HI 19 score of ≤1 to fulfil contemporary requirements for histological remission, resulting in an overall rate of histological remission of 53.6% with 3.0 g/day mesalazine granules.

Combined endoscopic and histological remission also increasingly represents a treatment target. 7 While sometimes termed ‘mucosal healing’, inconsistent usage of this term has led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to discourage its use altogether. 29 We found that composite endoscopic plus histological remission was achieved in an encouraging 24.9% of patients with moderate UC on 3.0 g mesalazine/day.

In light of the importance of histological remission for predicting long‐term outcomes, several experts have recently proposed that the concept of ‘disease clearance’—defined as combined clinical, endoscopic and histological remission—be applied to UC as the ultimate treatment target both in clinical trials and in routine practice. 8 , 30 Although prospective data is currently lacking, several studies have reported around 50% overlap between endoscopic remission and histological remission in patients with severe UC, 5 suggesting that disease clearance is a feasible target. Nonetheless, levels of disease clearance following initial induction therapy will likely remain low given the weak correlation between endoscopic and histological remission. In that context, the 18.8% rate of disease clearance among patients in our analysis with moderate UC receiving 3.0 g mesalazine/day appears very promising and solidifies its value as first‐line therapy in this population. Encouragingly, a recent retrospective cohort study has reported that patients achieving disease clearance have a significantly lower risk of UC‐related hospitalisation and surgery. 10 Interestingly, this study also reported an overall disease clearance rate of 22.1%.

Our study has several limitations. This analysis was not a prospective study with pre‐defined primary objectives, but a pooled post hoc analysis of studies that were structurally similar yet pursued different specific research questions. Accordingly, the sizes of the dosage groups also fluctuated, hindering robust statistical analyses. At the same time, any heterogeneity between the studies is likely to reduce the risk of unanticipated biases and therefore enhance the real‐world applicability of our findings. Finally, as discussed above, the included studies evaluated efficacy using indexes which are no longer as widely used.

Given the continuing importance of mesalazine in the first‐line treatment of mild‐to‐moderate UC, our results show that mesalazine granules as induction therapy can induce disease clearance in a clinically relevant percentage of patients. A daily dose of 3.0 g appears optimal to achieve this target. Prospective studies with disease clearance and long‐term outcomes as primary endpoints are needed to confirm these results and more precisely identify patient populations with the greatest benefits.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

These authors disclose the following: Wolfgang Kruis has received honoraria from Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH. Silke Meszaros, Sarah Wehrum, Roland Greinwald, Ralph Mueller and Tanju Nacak are employees of Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH. [Correction added on 09 August 2023, after first online publication: Sarah Wehrum’s disclosure has been added in this version.]

ETHICS APPROVAL

All included trials were approved by the National Ethics Committees of the participating countries.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Appropriate patient consent was obtained in the original trials included in this post hoc analysis. Details on patient consent can be found in the respective original publications.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

All included trials were registered as required as described in the respective original publications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Geoffrey Chase (Chase Biomedical Language Services) for writing assistance. This post hoc analysis was sponsored by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH. Funding details for the individual trials included in the analysis can be found in the respective original publications.

Kruis W, Meszaros S, Wehrum, S , Mueller R, Greinwald R, Nacak T. Mesalazine granules promote disease clearance in patients with mild‐to‐moderate ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2023;11(8):775–783. 10.1002/ueg2.12435

[Correction added on 3 October 2023, after first online publication: Figures 1 and 2 have been updated]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH, Group I. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population‐based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):412–422. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat‐to‐target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(9):1324–1338. 10.1038/ajg.2015.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zallot C, Peyrin‐Biroulet L. Deep remission in inflammatory bowel disease: looking beyond symptoms. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15(3):315. 10.1007/s11894-013-0315-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bryant RV, Winer S, Travis SP, Riddell RH. Systematic review: histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(12):1582–1597. 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, Walsh AJ, Thomas S, von Herbay A, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow‐up. Gut. 2016;65(3):408–414. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Administration FaD . Ulcerative colitis: clinical trial endpoints. Guidance for Industry; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ungaro R, Colombel JF, Lissoos T, Peyrin‐Biroulet L. A treat‐to‐target update in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):874–883. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Danese S, Roda G, Peyrin‐Biroulet L. Evolving therapeutic goals in ulcerative colitis: towards disease clearance. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(1):1–2. 10.1038/s41575-019-0211-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elewski BE, Puig L, Mordin M, Gilloteau I, Sherif B, Fox T, et al. Psoriasis patients with psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 response achieve greater health‐related quality‐of‐life improvements than those with PASI 75‐89 response: results from two phase 3 studies of secukinumab. J Dermatol Treat. 2017;28(6):492–499. 10.1080/09546634.2017.1294727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D'Amico F, Fiorino G, Solitano V, Massarini E, Guillo L, Allocca M, et al. Ulcerative colitis: impact of early disease clearance on long‐term outcomes – a multicenter cohort study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2022;10(7):775–782. 10.1002/ueg2.12288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kruis W, Bar‐Meir S, Feher J, Mickisch O, Mlitz H, Faszczyk M, et al. The optimal dose of 5‐aminosalicylic acid in active ulcerative colitis: a dose‐finding study with newly developed mesalamine. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1(1):36–43. 10.1053/jcgh.2003.50006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marakhouski Y, Fixa B, Holomán J, Hulek P, Lukas M, Bátovský M, et al. A double‐blind dose‐escalating trial comparing novel mesalazine pellets with mesalazine tablets in active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(2):133–140. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kruis W, Kiudelis G, Rácz I, Gorelov IA, Pokrotnieks J, Horynski M, et al. Once daily versus three times daily mesalazine granules in active ulcerative colitis: a double‐blind, double‐dummy, randomised, non‐inferiority trial. Gut. 2009;58(2):233–240. 10.1136/gut.2008.154302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gross V, Bunganic I, Belousova EA, Mikhailova TL, Kupcinskas L, Kiudelis G, et al. 3g mesalazine granules are superior to 9mg budesonide for achieving remission in active ulcerative colitis: a double‐blind, double‐dummy, randomised trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(2):129–138. 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5‐aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. BMJ. 1989;298(6666):82–86. 10.1136/bmj.298.6666.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro‐de Acosta M, et al. Third European evidence‐based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra‐intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo‐anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(6):649–670. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, et al. STRIDE‐II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat‐to‐target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1570–1583. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dignass A, Schnabel R, Romatowski J, Pavlenko V, Dorofeyev A, Derova J, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel high‐dose mesalazine tablet in mild to moderate active ulcerative colitis: a double‐blind, multicentre, randomised trial. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(1):138–147. 10.1177/2050640617703842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Dutt S, Herd ME. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: what does it mean? Gut. 1991;32(2):174–178. 10.1136/gut.32.2.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, Esser D, Wang Y, Lang Y, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long‐term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(4):1194–1201. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Le Berre C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Danese S, Singh S, Peyrin‐Biroulet L. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease have similar burden and goals for treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(1):14–23. 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1–s106. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caron B, Jairath V, D'Amico F, Paridaens K, Magro F, Danese S, et al. Definition of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis in clinical trials: a systematic literature review. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2022;10(8):854–867. 10.1002/ueg2.12283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Bressenot A, Kampman W. Histologic remission: the ultimate therapeutic goal in ulcerative colitis? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(6):929–934.e2. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rath T, Atreya R, Neurath MF. Is histological healing a feasible endpoint in ulcerative colitis? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(6):665–674. 10.1080/17474124.2021.1880892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolff S, Terheggen G, Mueller R, Greinwald R, Franklin J, Kruis W. Are endoscopic endpoints reliable in therapeutic trials of ulcerative colitis? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(12):2611–2615. 10.1097/01.mib.0000437044.43961.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaneshiro M, Takenaka K, Suzuki K, Fujii T, Hibiya S, Kawamoto A, et al. Pancolonic endoscopic and histologic evaluation for relapse prediction in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53(8):900–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Administration FaD . Ulcerative colitis: developing drugs for treatment; 2022.

- 30. Dal Buono A, Roda G, Argollo M, Zacharopoulou E, Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Danese S. Treat to target or ‘treat to clear’ in inflammatory bowel diseases: one step further? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14(9):807–817. 10.1080/17474124.2020.1804361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.