Abstract

Sanfetrinem is a trinem β-lactam which can be administered orally as a hexatil ester. We examined whether its β-lactamase interactions resembled those of the available carbapenems, i.e., stable to AmpC and extended-spectrum β-lactamases but labile to class B and functional group 2f enzymes. The comparator drugs were imipenem, oral cephalosporins, and amoxicillin. MICs were determined for β-lactamase expression variants, and hydrolysis was examined directly with representative enzymes. Sanfetrinem was a weak inducer of AmpC β-lactamases below the MIC and had slight lability, with a kcat of 0.00033 s−1 for the Enterobacter cloacae enzyme. Its MICs for AmpC-derepressed E. cloacae and Citrobacter freundii were 4 to 8 μg/ml, compared with MICs of 0.12 to 2 μg/ml for AmpC-inducible and -basal strains; MICs for AmpC-derepressed Serratia marcescens and Morganella morganii were not raised. Cefixime and cefpodoxime were more labile than sanfetrinem to the E. cloacae AmpC enzyme, and AmpC-derepressed mutants showed much greater resistance; imipenem was more stable and retained full activity against derepressed mutants. Like imipenem, sanfetrinem was stable to TEM-1 and TEM-10 enzymes and retained full activity against isolates and transconjugants with various extended-spectrum TEM and SHV enzymes, whereas these organisms were resistant to cefixime and cefpodoxime. Sanfetrinem, like imipenem and cefixime but unlike cefpodoxime, also retained activity against Proteus vulgaris and Klebsiella oxytoca strains that hyperproduced potent chromosomal class A β-lactamases. Functional group 2f enzymes, including Sme-1, NMC-A, and an unnamed enzyme from Acinetobacter spp., increased the sanfetrinem MICs by up to 64-fold. These enzymes also compromised the activities of imipenem and amoxicillin but not those of the cephalosporins. The hydrolysis of sanfetrinem was examined with a purified Sme-1 enzyme, and biphasic kinetics were found. Finally, zinc β-lactamases, including IMP-1 and the L1 enzyme of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, conferred resistance to sanfetrinem and all other β-lactams tested, and hydrolysis was confirmed with the IMP-1 enzyme. We conclude that sanfetrinem has β-lactamase interactions similar to those of the available carbapenems except that it is a weaker inducer of AmpC types, with some tendency to select derepressed mutants, unlike imipenem and meropenem.

Carbapenems evade many β-lactamases that compromise other β-lactams: in particular, imipenem, meropenem, and biapenem are stable to extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) (3, 16), and the AmpC β-lactamases only confer resistance when they are hyperproduced in exceptionally impermeable strains (5, 16). Nevertheless, β-lactamase-mediated resistance to carbapenems does occur, and this is mostly caused by zinc (class B) enzymes. Such β-lactamases are chromosomal in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Flavobacterium odoratum, some Aeromonas spp., and in a few Bacteroides fragilis isolates (10, 17, 29); additionally, a carbapenem-hydrolyzing zinc β-lactamase, IMP-1, has become plasmid mediated in Japan, where it has spread in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, and Klebsiella spp. (24, 32). Carbapenem-hydrolyzing activity also occurs in three closely related class A enzymes (Sme-1, NMC-A, and IMI-1) (23, 30, 36), which were recorded as chromosomal in tiny numbers of S. marcescens and Enterobacter cloacae isolates, most of which were collected before carbapenems entered clinical use. Finally, carbapenem resistance is emerging in Acinetobacter spp., where it is most often mediated by functional group 2f β-lactamases (1, 26) but where it is occasionally mediated by zinc-dependent enzymes (27) or β-lactamase-independent mechanisms (33).

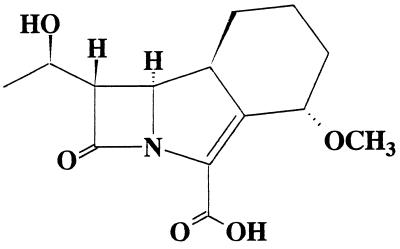

Trinems (previously tribactams) have a carbapenem-related structure but with a cyclohexane ring attached across carbons 1 and 2 (Fig. 1). Sanfetrinem, which is the first member of the family to be developed, can be administered orally as a hexatil ester. In the present study we have compared its β-lactamase interactions with those of imipenem and various oral β-lactams.

FIG. 1.

Structure of sanfetrinem.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Twenty-one chromosomal β-lactamase expression mutant series of Citrobacter freundii, E. cloacae, Morganella morganii, S. marcescens, S. maltophilia, and Proteus vulgaris were tested. Their derivation was described previously (2, 33–35). Most series comprised a β-lactamase-inducible isolate and its β-lactamase-derepressed and -basal mutants, but some lacked inducible parent strains, having been derived from derepressed isolates. The derepressed mutants were spontaneous variants of the inducible strains selected on cefotaxime-containing agar; the basal mutants were derived from derepressed organisms by mutagenesis with ethyl methane sulfonate or with N-methyl N-nitro N-nitrosoguanidine. The S. maltophilia mutants mostly had identical modes of expression of the L1 and L2 enzymes, which are coregulated (2), but one mutant of strain 10257 was basal for the L1 enzyme while it remained inducible for the L2 enzyme. Transconjugants of Escherichia coli with plasmid-mediated β-lactamases were as described by Livermore and Corkill (18) and were prepared by broth or plate mating. Aside from the S. maltophilia mutants, the organisms with carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases comprised S. marcescens S6 with the Sme-1 enzyme (36), S. marcescens 487 with an uncharacterized enzyme, Acinetobacter sp. strains BAHCT 3 and BAHCT 15 with an unnamed functional group 2f enzyme (1, 3), and P. aeruginosa 101/1477 with the IMP-1 enzyme. The 220 Klebsiella isolates with extended-spectrum β-lactamases were from a European survey conducted in 1994 and were collected from 23 hospitals (20); Klebsiella isolates with AmpC β-lactamase (n = 5) and a Klebsiella oxytoca strain that hyperproduced the K1 enzyme (n = 19) were also from that study.

Antibiotics and reagents.

Amoxicillin was from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), cefixime was from Wyeth (Taplow, United Kingdom), cefpodoxime was from Roussel (Uxbridge, United Kingdom), imipenem was from Merck Sharp & Dohme (Hoddesdon, United Kingdom), nitrocefin was from BBL (Cockeysville, Md.), and sanfetrinem was from Glaxo S.P.A. (Verona, Italy). Solutions were prepared on the day of use. Mueller-Hinton II media were from BBL. The other chemicals and reagents were from Sigma.

β-Lactamase extraction.

Cultures were grown overnight at 37°C with continuous shaking in nutrient broth and were then diluted 10-fold in fresh warm broth and incubated for a further 5 h. Subsequently, the cells were harvested at 5,000 × g and 37°C for 15 min, washed once in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and disrupted by two or three cycles of freezing and thawing. Debris was removed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g and 4°C for 45 min.

Purification of E. cloacae AmpC enzyme.

A crude extract, prepared as described above, was applied to a carboxymethyl Sephadex C-50 (Pharmacia, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) column (40 cm by 2.6 cm in diameter) equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). This column was washed overnight with the same buffer and then eluted with 600 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing a linear gradient of from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. The fractions with the greatest activity against cephaloridine were dialyzed against 5 liters of 20 mM triethanolamine (pH 7.0) containing 0.5 M NaCl and were then loaded on a phenylboronic acid-agarose column (20 cm by 2 cm in diameter), prepared as described by Cartwright and Waley (4), and equilibrated in 20 mM triethanolamine (pH 7.0) containing 0.5 M NaCl. This column was washed with 5 volumes of equilibration buffer, and then elution was conducted with 0.5 M NaCl–0.5 M sodium borate (pH 7.0). The fractions with the highest activity were extensively dialyzed against 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to eliminate the borate and were then stored at −20°C.

Purification of TEM-1 and TEM-10 enzymes.

The TEM-1 and TEM-10 enzymes were purified from crude extracts by two anion exchanges and one gel filtration. A DEAE Sephadex A50 column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8) (TEM-1) or 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) (TEM-10) was used for the first anion exchange. After overnight washing with the equilibration buffer, the enzyme was eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8 [TEM-1] or pH 7.0 [TEM-10]) containing a linear gradient of from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. The eluted fractions were dialyzed against 5 liters of 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and were then applied to a 16/10 Hi-load Q-Sepharose high-performance column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with the same buffer. This column was washed with 3 volumes of equilibration buffer, and then elution with a 0 to 0.5 M salt gradient was conducted. The most active fractions were subjected to gel filtration on a 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

Purification of Sme-1 enzyme.

The crude extract was applied to a carboxymethyl Sephadex C-50 (Pharmacia) column equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.2). This column was washed overnight with the same buffer, and then elution was conducted with 500 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.2) containing a linear gradient of from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. The fractions with the greatest activity against imipenem were dialyzed against 5 liters of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8.2) and were loaded on to a 16/10 S-Sepharose high-performance column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with the same buffer. This was washed with 60 ml of equilibration buffer, and then the enzyme was eluted with a 0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient and further purified by gel filtration on a 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

Purification of IMP-1 enzyme.

The crude extract was applied to a carboxymethyl Sephadex C-50 (Pharmacia) column (40 cm by 2.6 cm in diameter) equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 100 μM ZnCl2. The column was washed overnight with the same buffer, and then elution was conducted with 500 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 100 μM ZnCl2 and a linear gradient of from 0 to 0.5 M NaCl. The fractions showing the greatest activity were dialyzed against 5 liters of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 100 μM ZnCl2 and loaded on to a 16/10 S-Sepharose high-performance column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with the same buffer. After washing with 5 volumes of equilibration buffer, the enzyme was eluted with a 0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient.

The purity and molecular weights of all the enzymes were examined on the sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system of Hancock and Carey (11), run with the buffers of Lugtenberg et al. (22).

β-Lactamase kinetics.

Hydrolysis was monitored by UV spectrophotometry at 37°C with antibiotic solutions in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The buffer was supplemented with 100 μM ZnCl2 for assays with the IMP-1 enzyme. Wavelengths were as follows: for amoxicillin, 263 nm; for cefixime and cefpodoxime, 260 nm; for imipenem, 297 nm; and for sanfetrinem, 270 nm. kcat and Km values were calculated from Hanes plots of initial velocity data.

Susceptibility tests.

The MICs were determined by inoculating ca. 5 × 104 CFU/ml from overnight nutrient broth cultures onto Mueller-Hinton II agar plates containing doubling dilutions of antibiotics. The MICs were read after overnight incubation at 37°C.

Induction assays for AmpC β-lactamases.

β-Lactamase induction assays were performed by exposing logarithmic-phase bacteria in Mueller-Hinton II broth (Unipath) to β-lactams at 0.1, 0.25, 1, and 2 times the MICs for 4 h. The assay substrate was 10 mM cephaloridine in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and the assays were performed at 37°C in 1-mm-light-path cuvettes. Induction ratios were calculated as β-lactamase activity per milligram of protein in induced cells: β-lactamase activity per milligram of protein in uninduced cells. Protein concentrations were assayed by the method of Lowry et al. (21).

Selection of resistant mutants.

Selection studies were performed for five strains each of E. cloacae, C. freundii, M. morganii, and S. marcescens by plating 108 to 109 CFU/ml from overnight nutrient broth cultures onto Mueller-Hinton II agar containing sanfetrinem at 2, 4, 8, and 16 times the MIC. None of the strains had other β-lactamases besides inducible AmpC. Mutants were tested for derepression of AmpC by drop tests with nitrocefin and nitrocefin plus cloxacillin (19). Colonies that gave swift nitrocefin reactions that were completely inhibited by 0.1 mM cloxacillin were considered to be derepressed.

RESULTS

Hydrolysis of sanfetrinem and comparators.

The AmpC enzyme of E. cloacae 684-con had only marginal activity against sanfetrinem, with a kcat of 0.00033 s−1, compared to a kcat of 25 s−1 for amoxicillin and a kcat of 8 s−1 for cefpodoxime (Table 1). This enzyme had unusual kinetics against cefixime: at drug concentrations of between 0.01 and 1 mM the progress curve was sigmoidal, with initial acceleration and subsequent deceleration. No AmpC activity was seen against imipenem. Neither the TEM-1 nor the TEM-10 enzyme had detectable activity against sanfetrinem or imipenem, whereas amoxicillin was readily hydrolyzed, with kcat values of 2,360 and 31 s−1 for TEM-1 and TEM-10, respectively. The TEM-1 enzyme was unable to hydrolyze cefixime, whereas TEM-10 showed sigmoidal kinetics similar to those of the AmpC enzyme. Cefpodoxime was readily hydrolyzed by both TEM-1 and TEM-10 enzymes: with TEM-1 the hydrolysis rate was proportional to the substrate concentration between 10 and 1,000 μM, implying a very high Km, whereas a measurable Km (100 μM) was found for TEM-10. The Sme-1 enzyme hydrolyzed sanfetrinem, imipenem, and amoxicillin but lacked discernible activity against cefixime and cefpodoxime. Its kinetics for sanfetrinem were biphasic, with the rate declining more rapidly than could be explained by substrate depletion. This behavior was analyzed with the program of de Meester et al. (9), which revealed a kcat of 11 s−1 in the fast phase and 1.2 s−1 in the slow phase. The kinetics for the other substrates were linear. The IMP-1 enzyme readily hydrolyzed all the compounds tested, but sanfetrinem was the weakest substrate in terms of both kcat and kcat/Km.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic constants of β-lactamases for sanfetrinem and comparator drugs

| Antibiotic | Sme-1

|

IMP-1

|

TEM-1

|

TEM-10

|

AmpC

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | |

| Sanfetrinem | 11 (NLKa) (I) | 3.3 (I) | 1.6 | 24 | <0.0005 | <0.003 | 0.00033 | |||

| 1.2 (NLK) (S)b | 2.8 (S) | |||||||||

| Imipenem | 66.2 | 77 | 106.3 | 87 | <0.0005 | <0.003 | <0.0002 | |||

| Amoxicillin | 247 | 37 | 5.7 | 342 | 2360 | 149 | 31 | 28 | 25 | 10 |

| Cefixime | <0.007 | 20.5 | 990 | <0.0005 | 16 (NLKc) | 10 (NLKc) | ||||

| Cefpodoxime | 0.007 | 73.8 | 131 | 3.15 (NLKd) | 21 | 100 | 8 | 2 | ||

NLK, nonlinear kinetics.

Biphasic kinetics, analyzed in detail by the program of de Meester et al. (9). I, initial rate; S, steady-state rate.

Sigmoidal reaction curves, as described in the text; the kcat values are turnover rates with 0.1 mM substrate.

Linear relationship between hydrolysis rate and substrate concentration. The kcat value is the turnover rate with 1 mM substrate.

MICs for chromosomal β-lactamase inducibility mutants.

The MICs for three chromosomal β-lactamase expression mutant series each of C. freundii, E. cloacae, M. morganii, S. marcescens, P. vulgaris, and S. maltophilia are presented in Table 2. Quantitative details about the β-lactamase expression of these reference mutants have been published previously, together with full details of their derivation and provenance (2, 33–35). Briefly, the organisms with unsuffixed numbers and those with the suffix ind were the β-lactamase-inducible parent strains; those with numbers and the suffix con were their AmpC derepressed mutants with copious levels of β-lactamase production irrespective of induction; and those with numbers and the suffix def were their AmpC-basal mutants, which produced only a trace level of enzyme, irrespective of the presence of inducers. For species with class C β-lactamases (i.e., C. freundii, E. cloacae, M. morganii, and S. marcescens), the MICs of sanfetrinem were consistently below 8 μg/ml, irrespective of the mode of β-lactamase expression. In the case of the E. cloacae and C. freundii series, the AmpC-derepressed mutants were consistently less susceptible (although not always significantly so) than both the inducible parent strains and the AmpC-basal mutants. By contrast, the MICs of the trinem generally varied twofold or less between the AmpC-inducible, -basal, and -derepressed organisms in the M. morganii and S. marcescens series, although the M. morganii M6 series was a minor exception, with a fourfold MIC variation in the MICs for variants with the different AmpC expression phenotypes. The MICs of cefixime and cefpodoxime for derepressed mutants of all four species were high (8 to >128 μg/ml), whereas the β-lactamase-inducible and -basal organisms were equally susceptible. The MICs of imipenem were independent of AmpC expression for all species and were always less than 1 μg/ml, whereas amoxicillin was active only against AmpC-basal mutants, while AmpC-inducible and -derepressed mutants were highly resistant. P. vulgaris has a chromosomal class A β-lactamase rather than a class C type (3, 35). This conferred no protection against sanfetrinem, imipenem, or cefixime, regardless of its mode of expression, but protected it against cefpodoxime when it was derepressed and against amoxicillin when it was inducible or derepressed (Table 2). Inducible or derepressed expression of the L1 and L2 enzymes conferred protection against all five compounds (MICs, 64 μg/ml) in S. maltophilia, whereas the L1- and L2-basal mutants were more susceptible. Increased susceptibility to all five drugs was also seen for the mutant of strain NCTC 10257 that was basal for the L1 enzyme but inducible for the L2 enzyme, indicating that the L1 enzyme is the primary source of resistance.

TABLE 2.

MICs of sanfetrinem and comparator drugs for β-lactamase inducibility mutantsa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanfetrinem | Imipenem | Amoxicillin | Cefixime | Cefpodoxime | |

| C. freundii | |||||

| C 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 512 | 2 | 4 |

| C 2-con | 4 | 0.25 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| C 2-def | 0.25 | 0.12 | 32 | 64 | 16 |

| C 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 256 | 1 | 2 |

| C 4-con | 2 | 0.25 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| C 4-def | 0.5 | 0.25 | 128 | 4 | 8 |

| C 10 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 64 | 1 | 1 |

| C 10-con | 2 | 0.25 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| C 10-def | 0.12 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| C 12 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 64 | 0.5 | 1 |

| C 12-con | 4 | 0.25 | >512 | 128 | >128 |

| C 12-def | 0.12 | 0.06 | >512 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| E. cloacae | |||||

| 84-con | 8 | 0.5 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| 84-def | 0.5 | 0.25 | 256 | 64 | 64 |

| 100-con | 0.5 | 0.12 | 512 | >128 | >128 |

| 100-def | 0.25 | 0.25 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 684 | 2 | 0.25 | >512 | 4 | 8 |

| 684-con | 4 | 0.25 | 512 | >128 | >128 |

| 684-def | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| M. morganii | |||||

| M 1 | 1 | 1 | 512 | 0.5 | 4 |

| M 1-con | 1 | 1 | >512 | 32 | 64 |

| M 1-def | 0.5 | 1 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| M 6 | 0.5 | 1 | 512 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| M 6-con | 0.5 | 1 | >512 | 16 | 64 |

| M 6-def | 0.12 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| S. marcescens | |||||

| S 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 128 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S 2-con | 2 | 0.5 | 256 | 8 | 16 |

| S 2-def | 1 | 0.5 | 128 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S 7 | 1 | 0.5 | 128 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| S 7-con | 2 | 1 | 256 | 32 | 64 |

| S 7-def | 2 | 0.5 | 128 | 0.25 | 1 |

| P. vulgaris | |||||

| Va1 | 0.12 | 0.5 | >512 | ≤0.015 | 0.25 |

| Va1-con | 0.12 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.06 | 8 |

| Va1-def | 0.06 | 0.12 | 2 | ≤0.015 | 0.06 |

| V 2 | 0.12 | 0.25 | >512 | ≤0.015 | 0.25 |

| V 2-con | 0.12 | 0.25 | >512 | ≤0.015 | 2 |

| V 2-def | 0.12 | 0.25 | 16 | ≤0.015 | 0.12 |

| V2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | >512 | 0.015 | 0.25 |

| V2-con | 0.12 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.06 | 8 |

| V2-def | 0.12 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.015 | 0.06 |

| V3 | 0.06 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.015 | 0.25 |

| V3-con | 0.06 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.015 | 2 |

| V3-def | 0.06 | 0.25 | 16 | 0.015 | 0.12 |

| S. maltophilia | |||||

| 10257 L1, L2 ind | >64 | >64 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| 10257 L1, L2 con | >64 | >64 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| 10257 L1, L2 def | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 10257 L1 def, L2 ind | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 10499 L1, L2 ind | >64 | >64 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| 10499 L1, L2 con | >64 | >64 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| 10499 L1, L2 def | 4 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 8 |

Organisms indicated by unsuffixed numbers and those with the suffix ind were inducible for the chromosomal β-lactamases, those indicated by numbers and the suffix con were derepressed for the enzymes, and those indicated by numbers and the suffix def were basal for these enzymes. Full details of the strains and their β-lactamase expression characteristics are given elsewhere (2, 33–35).

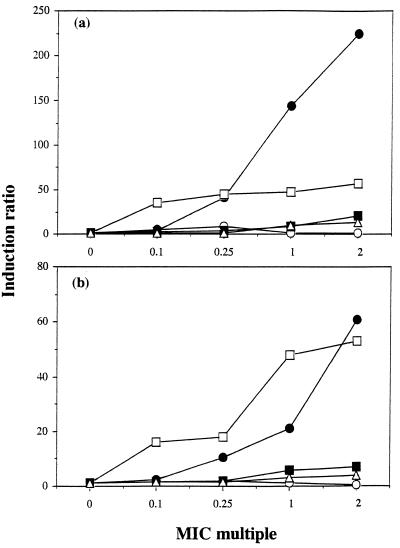

Induction of AmpC β-lactamases.

The β-lactamase inducer power of sanfetrinem and its comparators was assayed for E. cloacae 684 and C. freundii C2 (Fig. 2). Sanfetrinem, cefixime, and cefpodoxime were weak inducers, giving a maximum of 20-fold induction at two times the MIC. Conversely, imipenem and amoxicillin at one to two times the MIC gave up to 225-fold induction.

FIG. 2.

Induction of AmpC β-lactamases in E. cloacae 684 (a) and C. freundii (b). Data are for sanfetrinem (○), imipenem (•), amoxicillin (□), cefixime (▪), and cefpodoxime (▵).

Selection of resistant mutants by sanfetrinem.

Selection experiments were performed with five AmpC-inducible strains each of E. cloacae, C. freundii, M. morganii, and S. marcescens. Mutants resistant to sanfetrinem at two times the MIC were consistently obtained at frequencies of ca. 10−7 (Table 3). Most of the E. cloacae, C. freundii, and M. morganii strains also gave mutants resistant to the drug at four times the MIC, but only one S. marcescens strain did so. Mutants resistant to the drug at 8 times the MIC were selected only from two C. freundii strains, and no resistant mutants were selected with sanfetrinem at 16 times the MIC. Most mutants except those from S. marcescens 999 gave strong nitrocefin reactions (<30 s for a strong reaction) that were completely inhibited by 0.1 mM cloxacillin. This behavior suggested derepression of AmpC (19). The parent strains gave slow reactions with nitrocefin (>5 min for a red color), and these were completely inhibited by cloxacillin. A few mutants, including all those selected from S. marcescens 999, did not give strong nitrocefin reactions, and it is likely that they owed their behavior to some combination of impermeability or increased efflux.

TABLE 3.

Selection of resistant mutants by sanfetrinem

| Isolate | MIC (μg/ml) | Two times the MIC

|

Four times the MIC

|

Eight times the MIC

|

Mutation frequency at 16 times the MIC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation frequency | No. derepressed/no. tested | Mutation frequency | No. derepressed/no. tested | Mutation frequency | No. derepressed/no. tested | |||

| E. cloacae | ||||||||

| 238 | 0.5 | 1 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| 467 | 0.5 | 7 × 10−7 | 8/10 | 1.6 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| 751 | 0.5 | 2.8 × 10−6 | 10/10 | 1.2 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| 206 | 2 | 9 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| 684 | 2 | 1.4 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| C. freundii | ||||||||

| C10 | 0.25 | 5 × 10−7 | 8/10 | 7.3 × 10−8 | 10/10 | 6.6 × 10−9 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 |

| C12 | 0.25 | 7.9 × 10−7 | 4/10 | 4.4 × 10−7 | 8/10 | 1.1 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 |

| 722 | 0.5 | 5.2 × 10−7 | 6/10 | 4.6 × 10−8 | 8/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| C2 | 1 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 10/10 | 4.7 × 10−8 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| C4 | 1 | 3.3 × 10−8 | 5/5 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| M. morganii | ||||||||

| M6 | 0.5 | 3 × 10−7 | 10/10 | 5 × 10−8 | 9/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| M1 | 1 | 2.5 × 10−7 | 10/10 | 6 × 10−8 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| 8 | 1 | 2.2 × 10−7 | 10/10 | 8 × 10−9 | 2/2 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| 11 | 1 | 6.5 × 10−7 | 10/10 | 3.2 × 10−8 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| 276 | 1 | 1.3 × 10−7 | 10/10 | 3.3 × 10−8 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| S. marcescens | ||||||||

| 999 | 1 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 0/10 | 1.1 × 10−7 | 0/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | |

| 951 | 2 | 4.6 × 10−7 | 6/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| S2 | 2 | 3.3 × 10−8 | 7/7 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| S7 | 2 | 1.3 × 10−7 | 10/10 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

| 834 | 4 | 9.4 × 10−9 | 3/3 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | <1 × 10−9 | ||

MICs for E. coli transconjugants with plasmid-mediated β-lactamases.

The MICs for E. coli transconjugants with various β-lactamases are presented in Table 4. Substantial protection against sanfetrinem (MIC increases of 16- to 64-fold) was given only by the NMC-A and IMP-1 enzymes; slight protection (up to 4-fold increases in the MIC) was also given by the TEM-6, TEM-9, TEM-10, SHV-5, OXA-3, OXA-5, and OXA-7 β-lactamases. All the transconjugants acquired resistance to amoxicillin; those with the TEM-3, TEM-6, TEM-9, TEM-10, SHV-4, SHV-5, OXA-5, and PER-1 enzymes acquired resistance to cefixime and cefpodoxime; the SHV-2 and SHV-3 enzymes conferred significant resistance to cefpodoxime but not cefixime. Production of the NMC-A and IMP-1 β-lactamases conferred two- and eightfold increases in the imipenem MICs, respectively, although neither enzyme conferred resistance relative to the low breakpoint of 4 μg/ml.

TABLE 4.

MICs for E. coli transconjugants with plasmid-mediated β-lactamases

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanfetrinem | Imipenem | Amoxicillin | Cefixime | Cefpodoxime | |

| J 53-1 R− | 0.5 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| J 53-2 R− | 1 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| J 62-1 R− | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 62 TEM-1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 62 TEM-2 | 1 | 0.12 | >512 | 0.12 | 0.5 |

| J 62 TEM-3a | 1 | 0.12 | >512 | 8 | 32 |

| J 53 TEM-6a | 2 | 0.25 | >512 | 8 | 16 |

| J 53 TEM-9a | 2 | 0.25 | >512 | 16 | 32 |

| J 53 TEM-10a | 2 | 0.25 | >512 | 8 | 32 |

| J 53 HMS-1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 53 SHV-1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| J 53 SHV-2a | 0.5 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.5 | 8 |

| J 53 SHV-3a | 0.12 | 0.12 | >512 | 0.25 | 8 |

| J 53 SHV-4a | 1 | 0.5 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| J 53 SHV-5a | 4 | 0.25 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| J 53 PSE-4 | 1 | 0.5 | >512 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 53 OXA-1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.25 | 2 |

| J 53 OXA-2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 53 OXA-3 | 2 | 0.25 | 256 | 0.5 | 1 |

| J 53 OXA-4 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 256 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 53 OXA-5 | 4 | 0.25 | >512 | 4 | 16 |

| J 53 OXA-7 | 4 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.5 | 2 |

| J 62 OXA-10 | 1 | 0.5 | 512 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| J 53 LXA-1 | 1 | 0.25 | 256 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| J 53 PER-1a | 0.25 | 0.25 | >512 | >128 | 128 |

| Jm83 R− | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Jm109 NMC-Ab | >16 | 0.5 | 256 | 0.25 | 1 |

| DH5-α | 0.25 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| DH5-α IMP-1b | 16 | 1 | 512 | 128 | >128 |

ESBL producer.

Producers of enzymes active against carbapenems.

MICs for Klebsiella isolates with ESBLs and other β-lactamases.

Two hundred twenty Klebsiella isolates with ESBLs were tested (Table 5). These were from patients in 23 intensive care units in southern and western Europe (20). The MICs of sanfetrinem and imipenem had unimodal distributions, with ranges of 0.12 to 8 and 0.06 to 1 μg/ml, respectively, and with modes of 1 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. The MIC distribution of cefixime was wide and unclustered, whereas that of cefpodoxime was wide and bimodal, with peaks at 0.25 and 16 μg/ml. All the ESBL producers were highly resistant to amoxicillin. A strong correlation (r = 0.77) existed between the log MICs of cefixime and cefpodoxime but not between those of other pairs of antimicrobial agents.

TABLE 5.

Distributions of MICs of sanfetrinem and comparator drugs for klebsiellae with β-lactamase-mediated resistance

| Strain group and drug | No. of isolates for which the MIC (μg/ml) was as follows:

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.008 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1,024 | ≥2,048 | |

| ESBL producers (n = 220) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sanfetrinem | 1 | 11 | 36 | 96 | 58 | 16 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Imipenem | 15 | 112 | 63 | 20 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| Cefixime | 6 | 12 | 5 | 18 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 16 | 14 | 36 | 24 | 22 | 7 | |||||

| Cefpodoxime | 1 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 25 | 48 | 46 | 33 | 13 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| Amoxicillin | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 199 | ||||||||||||||

| AmpC β-lactamase producers (n = 5) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sanfetrinem | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Imipenem | 3 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cefixime | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Cefpodoxime | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| K1 β-lactamase producers (n = 19) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sanfetrinem | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Imipenem | 7 | 10 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cefixime | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| Cefpodoxime | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||

Five further wild-type klebsiellae had AmpC enzymes, and 20 K. oxytoca isolates hyperproduced the K1 β-lactamase. For isolates with the AmpC enzyme (Table 5), the MICs of sanfetrinem and imipenem remained low (4 μg/ml), but resistance to cefixime and cefpodoxime (MICs, 16 to 128 μg/ml), as well as to amoxicillin, was apparent. Hyperproducers of the K1 enzyme (Table 5) were consistently susceptible to sanfetrinem (MIC, ≤4 μg/ml), imipenem (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml), and cefixime (MICs, 0.008 to 1 μg/ml), but they were more resistant than typical klebsiellae to cefpodoxime (MICs, 0.5 to 16 μg/ml) and were highly resistant to amoxicillin.

MICs for isolates with carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases.

S. marcescens S6 with Sme-1 and S. marcescens 487 with an uncharacterized enzyme were resistant to sanfetrinem and imipenem (MICs, 64 μg/ml). These were also resistant to amoxicillin (Table 6), but the MICs of cefixime and cefpodoxime were 1 μg/ml or less, which were no higher than those for AmpC-inducible strains without carbapenem-hydrolyzing activity (Table 2). Acinetobacter sp. strains BAHCT 3 and BAHCT 15, with an unsequenced functional group 2f enzyme (1), were resistant to all β-lactams (Table 6), but the MICs of sanfetrinem and imipenem for these strains were only 8 μg/ml, whereas those of cefixime and cefpodoxime were 128 μg/ml.

TABLE 6.

MICs of sanfetrinem and comparator drugs for isolates that produced enzymes capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems

| Strain (enzyme) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanfetrinem | Imipenem | Amoxicillin | Cefixime | Cefpodoxime | |

| S. marcescens | |||||

| S6 (Sme-1) | >64 | 64 | 512 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 487 (unknown) | >64 | >64 | >512 | 0.5 | 1 |

| P. aeruginosa 101/1477 (IMP-1) | >64 | >64 | >512 | >128 | >128 |

| Acinetobacter sp., strain BAHCT 15 (functional group 2f)a | 8 | 8 | >512 | 128 | 128 |

Identical MICs were found for isolate BAHCT 3.

DISCUSSION

We examined the interactions of sanfetrinem with representative class A, B, C, and D β-lactamases. The studies aimed to determine whether sanfetrinem shared the stability of imipenem and meropenem to AmpC and ESBLs and to determine whether sanfetrinem, like imipenem and meropenem, is inactivated by zinc β-lactamases and functional group 2f enzymes. These topics were primarily investigated by determining the MICs for predictor panels comprising β-lactamase expression variants; in addition, we undertook hydrolysis assays with five β-lactamases. E. cloacae AmpC was tested as a representative class C enzyme, TEM-1 was tested as the most widespread class A enzyme, TEM-10 was tested as a representative class A ESBL, Sme-1 was tested as a 2f enzyme, and IMP-1 was tested as the class B (zinc) enzyme currently posing the greatest concern. Induction assays and mutant selection studies were performed with AmpC producers. The comparator drugs were imipenem, as a reference carbapenem; cefixime and cefpodoxime, as oral expanded-spectrum cephalosporins likely to be used in settings similar to those in which sanfetrinem will be used; and amoxicillin, as a long-established oral penicillin with major β-lactamase lability.

At concentrations below its MIC, sanfetrinem was a weak inducer of AmpC enzymes (Fig. 2). Susceptibility tests reflected this behavior and the slight lability of sanfetrinem to the enzyme; thus, MICs for AmpC-derepressed E. cloacae and C. freundii were higher than those for the isogenic β-lactamase-inducible and -basal organisms (Table 2). Moreover, sanfetrinem tended to select derepressed mutants from inducible populations (Table 3). This pattern of behavior is in contrast to those of imipenem and meropenem, which are stable to enterobacterial AmpC enzymes and which retain full activity against derepressed mutants and so do not select this mode of resistance (7, 15). Nevertheless, none of the derepressed organisms was resistant to sanfetrinem at 8 μg/ml, and to this extent, the behavior of the trinem resembled those of cefepime and cefpirome, for which the MICs for AmpC derepressed mutants are raised but rarely exceed the breakpoint (6, 12). This retention of activity against derepressed strains is in contrast to the situation for expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, represented here by cefixime and cefpodoxime, in which derepression gives considerable resistance. The expanded-spectrum cephalosporins consequently have strong selectivities for derepressed mutants (8, 15). The kcat values of AmpC for cefpodoxime (8 s−1) and cefixime (10 s−1) were higher than that for sanfetrinem (0.00033 s−1), underlining the enzyme’s greater ability to confer resistance to the cephalosporins than to the trinem.

Sanfetrinem retained full activity against ESBL-producing transconjugants and wild types, as did imipenem. Moreover, both compounds were stable to TEM-1 and TEM-10 enzymes. By contrast, most ESBLs conferred resistance to cefixime, and all conferred resistance to cefpodoxime. The ability of TEM-10 β-lactamase to confer resistance to both cephalosporins correlated with strong hydrolytic activity (Table 1); the TEM-1 enzyme also hydrolyzed cefpodoxime rapidly, but its catalytic efficiency was reduced by an exceptionally high Km, probably explaining why it failed to confer resistance (Table 4).

Sanfetrinem lost activity against strains producing zinc-dependent and group 2f enzymes including (i) E. coli transconjugants and wild-type members of the family Enterobacteriaceae with NMC-A, Sme-1, and IMP-1 enzymes (Table 4 and 6); (ii) Acinetobacter isolates with a novel functional 2f enzyme (Table 6); and (iii) S. maltophilia strains with an inducible or derepressed L1 enzyme (Table 2). In vitro, sanfetrinem was hydrolyzed by carbapenemases belonging to class A (Sme-1) or B (IMP-1). Hydrolysis by the Sme-1 enzyme was biphasic, implying isomerization of the Michaelis complex or the acyl enzyme to a less rapidly productive form (13, 14). Such kinetics might be expected to reduce efficiency, but the producer strain was substantially resistant to the trinem (Table 6). In the case of the IMP-1 enzyme, the hydrolysis of sanfetrinem was linear but was much slower than that of imipenem. Nevertheless, the IMP-1 enzyme conferred greater resistance to sanfetrinem than imipenem, perhaps because imipenem is a faster permeant. IMP-1 also attacked and gave resistance to all the other β-lactams tested, whereas Sme-1 neither detectably hydrolyzed nor gave resistance to cefixime and cefpodoxime. Previous data indicate that other oxyimino aminothiazolyl cephalosporins are stable to the Sme-1 enzyme (36).

A peripheral aspect deserving comment was the sigmoidal hydrolysis kinetics for cefixime with AmpC and TEM-10 enzymes. Nonlinear kinetics are common for β-lactamases and are mostly explained by isomerization of the enzyme or of an enzyme-substrate complex (13, 14, 25, 28), but the sigmoidal kinetics are exceptional and further investigation is needed before a definitive mechanism can be proposed.

In summary, we found that sanfetrinem shared imipenem’s stability to ESBLs; on the other hand, it was slightly more labile to AmpC types of enzymes and tended to select derepressed mutants from inducible populations. Nevertheless, at 8 mg/liter it retained activity against these mutants, and selection should not be a greater problem for sanfetrinem than for cefepime and cefpirome, which show behaviors similar to that of sanfetrinem. Allowing that organisms with potent β-lactamases are increasingly seen in nursing homes (31), where potent oral antibiotics are likely to be heavily used, these distinctions from the behaviors of oral penicillins and cephalosporins may be significant advantages. Nevertheless, sanfetrinem remained labile to carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases belonging to functional group 2f and molecular class B, and great care should be taken to ensure that inappropriate community use does not exacerbate the spread of these enzymes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Glaxo S.P.A. Verona for support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afzal-Shah, M., F. Danel, G. S. Babini, and D. M. Livermore. Unpublished data.

- 2.Akova M, Bonfiglio G, Livermore D M. Susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics of Xanthomonas maltophilia mutants with high- and low-level constitutive expression of L-1 and L-2 β-lactamases. J Med Microbiol. 1991;35:208–213. doi: 10.1099/00222615-35-4-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification of β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartwright S J, Waley S G. Purification of β-lactamases by affinity chromatography on phenylboronic acid-agarose. Biochem J. 1984;221:505–512. doi: 10.1042/bj2210505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charrel R N, Pages J M, De Micco P, Mallea M. Prevalence of outer membrane protein alteration in β-lactam antibiotic-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2854–2858. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, H. Y., and D. M. Livermore. 1993. Comparative activity of cefepime against chromosomal β-lactamase inducibility mutants of gram-negative bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32(Suppl. B):63–74.

- 7.Chen H Y, Livermore D M. Comparative in-vitro activity of biapenem against enterobacteria with β-lactamase-mediated antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:453–464. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow J V, Fine M J, Shales D M, Quinn J P, Hooper D C, Johnson M P, Ramphal R, Wagener M M, Miyashiro D K, Yu V L. Enterobacter bacteremia: clinical features and emergence of antibiotic resistance during therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:585–590. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-8-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Meester F, Joris B, Reckinger G, Bellefroid-Bourguignon C, Frere J M, Waley S G. Automated analysis of enzyme inactivation phenomena. Application to β-lactamases and dd-peptidases. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:2393–2403. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felici A, Perilli M, Segatore B, Franceschini N, Setacci D, Oratore A, Stefani S, Galleni M, Amicosante G. Interactions of biapenem with active-site serine and metallo-β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1300–1305. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock R E, Carey A M. Outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: heat- and 2-mercaptoethanol-modifiable proteins. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:902–910. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.902-910.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hancock, R. E. W., and F. Bellido. 1992. Factors involved in the enhanced efficacy against gram-negative bacteria of fourth-generation cephalosporins. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29(Suppl. A):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kiener P A, Knott-Hunziker V, Petursson S, Waley S G. Mechanism of substrate-induced inactivation of β-lactamase I. Eur J Biochem. 1980;109:575–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledent P, Raquet X, Joris B, Van Beeumen J, Frere J M. A comparative study of class-D β-lactamases. Biochem J. 1993;292:555–562. doi: 10.1042/bj2920555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livermore D M. Clinical significance of β-lactamase induction and stable derepression in gram-negative rods. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987;6:439–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02013107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livermore D M. Acquired carbapenemases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:673–676. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livermore D M, Corkill J E. Effects of CO2 and pH on inhibition of TEM-1 and other β-lactamases by penicillanic acid sulfones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1870–1876. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livermore D M, Williams J D. β-Lactams: mode of action and mechanism of bacterial resistance. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1996. pp. 502–577. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livermore D M, Yuan M. Antibiotic resistance and production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases amongst Klebsiella spp. from intensive care units in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:409–424. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O H, Roseborough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lugtenberg B, Meijers J, Peters R, van der Hoek P, van Alphen L. Electrophoretic resolution of the “major outer membrane protein” of Escherichia coli K12 into four bands. FEBS Letts. 1975;58:254–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordmann P, Mariotte S, Naas T, Labia R, Nicolas M-H. Biochemical properties of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae and cloning of the gene into Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:939–946. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osano E, Arakawa Y, Wacharotayankun R, Ohta M, Horii T, Ito H, Yoshimura F, Kato N. Molecular characterization of an enterobacterial metallo-β-lactamase found in a clinical isolate of Serratia marcescens that shows imipenem resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:71–78. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page M G P. The kinetics of non-stoichiometric bursts of β-lactam hydrolysis catalysed by class C β-lactamase. Biochem J. 1993;295:295–304. doi: 10.1042/bj2950295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paton R, Miles R S, Hood J, Amyes S G B. ARI-1: β-lactamase-mediated resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1993;2:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(93)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez A N, Bonet I B, Robledo E H, Abascal R S, Plous C V. Metallo-β-lactamase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Med Sci Res. 1996;24:315–317. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persaud K C, Pain R H, Virden R. Reversible deactivation of β-lactamase by quinacillin. Extent of the conformational change in the isolated transitory complex. Biochem J. 1986;237:723–730. doi: 10.1042/bj2370723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen B A, Bush K. Carbapenem hydrolyzing β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:223–232. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmussen B A, Bush K, Keeney D, Yang Y, Hare R, O’Gara C, Medeiros A A. Characterization of IMI-1 β-lactamase, a novel class A carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme from Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2080–2086. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schiappa D A, Hayden M K, Matushek M G, Hasheni F N, Sullivan J, Smith K Y, Miyashiro D, Quinn J P, Weinstein R A, Trenholme G M. Ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli blood stream infection: a case-control and molecular epidemiologic investigation. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:529–536. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senda K, Arakawa Y, Nakashima K, Ito H, Ichiyama S, Shimokata K, Kato N, Ohta M. Multifocal outbreaks of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant to broad-spectrum β-lactams, including carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:349–353. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urban C, Go E, Mariano M, Rahal J J. Interaction of sulbactam, clavulanic acid and tazobactam with penicillin-binding proteins of imipenem-resistant and -susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;125:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y, Livermore D M. Activity of temocillin and other penicillins against β-lactamase-inducible and -stably derepressed enterobacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22:299–306. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Livermore D M. Chromosomal β-lactamase expression and resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Proteus vulgaris and Morganella morganii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1385–1391. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Y, Livermore D M, Williams R J. Chromosomal β-lactamase expression and antibiotic resistance in Enterobacter cloacae. J Med Microbiol. 1988;25:221–233. doi: 10.1099/00222615-25-3-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]