Abstract

Background

An estimated 260,000 children under the age of 15 years acquired HIV infection in 2012. As much as 42% of mother‐to‐child transmission is related to breastfeeding. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for mothers or infants has the potential to prevent mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV through breast milk.

Objectives

To determine which antiretroviral prophylactic regimens are efficacious and safe for reducing mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV through breastfeeding and thereby avert child morbidity and mortality.

Search methods

Using Cochrane Collaboration search methods in conjunction with appropriate search terms, we identified relevant studies from January 1, 1994 to January 14, 2014 by searching databases including Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE and PubMed, LILACS, and Web of Science/Web of Social Science.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials in which HIV‐infected mothers breastfed their infants, and in which the mothers used antiretroviral prophylaxis while breastfeeding their children or their children received antiretroviral prophylaxis for at least four weeks while breastfeeding, were included.

Data collection and analysis

Abstracts of all trials identified were examined independently by two authors. We identified 15,922 references and examined 81 in detail. Data were abstracted independently using a standardized form.

Main results

Seven RCTs were included in the review.

One trial compared triple antiretroviral prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding with short antiretroviral prophylaxis to given to the mother to prevent mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. At 12 months, the risks of HIV transmission, and of HIV transmission or death, were lower, but there was no difference in infant mortality alone in the triple arm versus the short arm. Using the GRADE methodology, evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally low to moderate.

One trial compared six months of breastfeeding using zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir/ritonavir versus zidovudine, lamivudine, and abacavir from 26‐34 weeks gestation. At six months, there was no difference in risk of infant HIV infection, infant death, or infant HIV infection or death between the two groups. Evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally very low to low.

One trial of single dose nevirapine versus six weeks of infant zidovudine found the risk of HIV infection at 12 weeks to be greater in the zidovudine arm than in the single dose nevirapine arm. Evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally very low.

One multi‐country trial compared single dose nevirapine and six weeks of infant nevirapine. After 12 months, infants in the extended nevirapine group had a lower risk of infant mortality compared with the control. There was no difference in the risk of HIV infection or death or in HIV transmission alone in the extended nevirapine group compared with the control. Evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally low to moderate.

One trial compared single dose nevirapine plus one week zidovudine; the control regimen plus nevirapine up to 14 weeks; or the control regimen with dual prophylaxis up to 14 weeks. At 24 months, the extended nevirapine regimen group had a lower risk of HIV transmission and of HIV transmission or death vs. the control. There was no difference in infant mortality alone. Compared with controls, the dual prophylaxis group had a lower risk of HIV transmission and of HIV transmission or death, but no difference in infant mortality alone. There was no difference in these outcomes between the two intervention arms. Evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally moderate to high.

One trial compared six weeks of nevirapine with six months of nevirapine. Among infants of mothers not using highly active antiretroviral therapy, there was no difference in risk of HIV infection among the six month nevirapine group versus the six week nevirapine group. Evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally low to moderate.

One trial compared a maternal triple‐drug antiretroviral regimen, infant nevirapine, or neither intervention. Infants in the maternal prophylaxis arm were at lower risk for HIV, and HIV infection or death when compared with the control group. There was no difference in the risk of infant mortality alone. Infants with extended prophylaxis had a lower risk of HIV infection and of HIV infection or death versus the control group infants. There was no difference in the risk of infant mortality alone in the extended infant nevirapine group versus the control. There was no difference in HIV infection, infant mortality, and HIV infection or death between the maternal and extended infant prophylaxis groups. Evidence quality for outcomes in this trial was generally low to moderate.

Authors' conclusions

Antiretroviral prophylaxis, whether used by the HIV‐infected mother or the HIV‐exposed infant while breastfeeding, is efficacious in preventing mother‐to‐child transmission of HIV. Further research is needed regarding maternal resistance and response to subsequent antiretroviral therapy after maternal prophylaxis. An ongoing trial (IMPAACT 1077BF) compares the efficacy and safety of maternal triple antiretroviral prophylaxis versus daily infant nevirapine for prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission through breastfeeding.

Plain language summary

Using antiretroviral medication to prevent transmission of HIV from mother‐to‐child during breastfeeding

Worldwide, the primary cause of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in children is mother‐to‐child transmission (MTCT). MTCT of HIV can occur during pregnancy, around the time of delivery, or through breastfeeding. Great strides have been made in reducing MTCT during pregnancy and around the time of delivery. However, without intervention, a significant proportion of children born to HIV–infected mothers acquire HIV through breastfeeding.

Where affordable, feasible, acceptable, sustainable, and safe (AFASS) alternatives to breast milk are available, it is recommended that HIV‐infected mothers do not breastfeed. However, for a substantial number of HIV‐infected women in the developing world, complete avoidance of breastfeeding is not AFASS. These mothers are counseled to practice exclusive breastfeeding (giving a child only breast milk and no additional food, water, or other fluids). Provision of antiretrovirals (ARVs) either to the mother or to the child during breastfeeding represent potential interventions to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to breastfeeding children. This review explores the available evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of ARV prophylaxis regimens to reduce breast milk transmission of HIV.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks compared to sdNVP plus ZDV (1week) for prevention of breastfeeding transmission.

| An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks compared to sdNVP plus ZDV (1week) for prevention of breastfeeding transmission | ||||||

| Patient or population: Breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers Settings: Malawi (PEPI trial) Intervention: An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks1 Comparison: sdNVP plus ZDV (1week)2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SdNVP plus ZDV (1week) | An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks | |||||

| HIV Transmission at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 98 per 10003 | 56 per 1000 (41 to 75)3 | HR 0.56 (0.41 to 0.76)4 | 2019 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5,6,7,8 | |

| Infant Mortality at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 71 per 10003 | 51 per 1000 (36 to 74)3 | HR 0.72 (0.5 to 1.05)9 | 2019 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5,6,8 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 168 per 10003,10 | 120 per 1000 (97 to 148)3,10 | HR 0.69 (0.55 to 0.87)4 | 2019 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high5,6,7,10 | |

| HIV Transmission at 24 months among those uninfected at birth11 Follow‐up: 24 months | 156 per 100012 | 97 per 1000 (75 to 124)12 | HR 0.60 (0.46 to 0.78) | 1129 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate8 | |

| Infant Mortality at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 165 per 100012 | 125 per 1000 (93 to 167)12 | HR 0.74 (0.54 to 1.01) | 1266 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate8 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 24 months among those uninfected at birth11 Follow‐up: 24 months | 242 per 100012 | 179 per 1000 (149 to 215)12 | HR 0.71 (0.58 to 0.87) | 1129 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate8 | |

| Infants with possible related Severe Adverse Events ‐ 24 months11 Follow‐up: 24 months | 43 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (30 to 68) | RR 1.06 (0.7 to 1.59) | 2019 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low8 | |

| Infants with Probably Related Severe Adverse Events11 Follow‐up: 24 months | 2 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (1 to 29) | RR 2.96 (0.6 to 14.64) | 2019 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low8 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Extended NVP prophylaxis included oral dose of nevirapine (2mg/kg) once daily during week 2, then 4mg/kg once daily during weeks 3‐14. 2 All infants received single oral dose of nevirapine (2mg/kg) plus oral zidovudine (4mg/kg) for 1 week. All mothers received intrapartum single dose nevirapine (except late presenters whose HIV infection was not identified until after they gave birth). 3 "Primary Analysis" denominator used. The primary analysis denominator includes all infants who were randomized to study arms with the exception of those infants who were determined to be HIV infected at birth and those with indeterminate results at birth. 4 Relative estimate of effect reported is hazard ratio presented in manuscript. Authors state that hazard ratios were adjusted for study group and other covariates that were considered to have biological or epidemiological importance. 5 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 6 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 7 As reviewed in Read JS. Diagnosis of HIV‐1 Infection in Children Younger Than 18 Months in the United States. Am Acad Ped 2007:120(6); e1547‐e1562, the sensitivity of DNA PCR for diagnosis of HIV in infants before 30 days is generally significantly less than 100%. For this reason, a baseline window of 4‐6 weeks is recommended to ensure that all in utero and intrapartum transmissions are captured. This study did not use 4‐6 weeks as baseline and as such may include some intrapartum transmissions. While there may be misclassification of timing of infection, there is no reason to believe that it would be differential across study arms. 8 Small number of events 9 Hazard Ratio was estimated using a log‐rank analysis. 10 Raw data for infant "HIV transmission or death" at 9 months was not provided by the study authors, so numerator was calculated as follows: [infant mortality at 9m + HIV transmission at 9m]. It is possible that some infants that died by 9 months may have tested positive for HIV prior to death and may have been double counted in the numerator. However the Hazard Ratio reported here from text already accounts for this. 11 Numerators from Taha manuscript 12 Calculated from rate of event times number at risk at 24 months

Summary of findings 2. An extended NVP plus ZDV regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks compared to sdNVP plus ZDV (1 week) for prevention of breastfeeding transmission.

| An extended NVP plus ZDV regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks compared to sdNVP plus ZDV (1 week) for prevention of breastfeeding transmission | ||||||

| Patient or population: Breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers Settings: Malawi (PEPI trial) Intervention: An extended NVP plus ZDV regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks1 Comparison: sdNVP plus ZDV (1 week) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SdNVP plus ZDV (1 week) | An extended NVP plus ZDV regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks | |||||

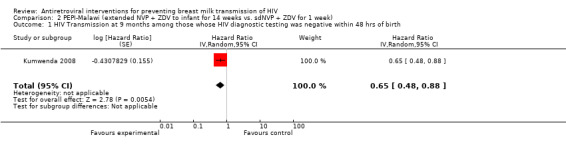

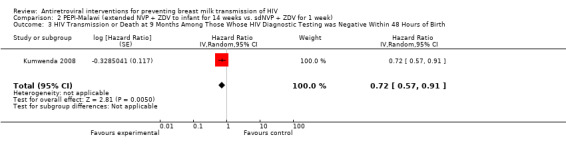

| HIV Transmission at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 98 per 1000 | 65 per 1000 (48 to 87) | HR 0.65 (0.48 to 0.88) | 2000 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Infant Mortality at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 71 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (33 to 68) | HR 0.66 (0.46 to 0.96) | 2000 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 168 per 1000 | 124 per 1000 (100 to 153) | HR 0.72 (0.57 to 0.9) | 2000 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| HIV Transmission at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 156 per 10003 | 104 per 1000 (81 to 134)3 | HR 0.65 (0.5 to 0.85) | 1123 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Infant Mortality at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 165 per 10003 | 123 per 1000 (91 to 165)3 | HR 0.73 (0.53 to 1) | 1207 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 242 per 10003 | 183 per 1000 (153 to 221)3 | HR 0.73 (0.6 to 0.9) | 1123 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Infants with any Severe Adverse Events Follow‐up: 24 months | 43 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (52 to 108) | RR 1.75 (1.22 to 2.53) | 2000 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| Infants with Probably Related Severe Adverse Events Follow‐up: 24 months | 2 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (1 to 30) | RR 3.02 (0.61 to 14.92) | 2000 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Extended NVP prophylaxis included oral dose of nevirapine (2mg/kg) once daily during week 2, then 4mg/kg once daily during weeks 3‐14. Extended ZDV prophylaxis included oral zidovudine (4mg/kg) twice daily during weeks 2‐5, 4mg/kg three times daily during weeks 6‐8, and 6mg/kg three times daily during weeks 9‐14. 2 Small number of events. 3 Calculated from rate of event times number at risk at 24 months

Summary of findings 3. An extended NVP plus ZDV dual regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks compared to an extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks.

| An extended NVP plus ZDV dual regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks compared to an extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks | ||||||

| Patient or population: Breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers1 Settings: Malawi (PEPI trial) Intervention: An extended NVP plus ZDV dual regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks2 Comparison: An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| An extended NVP plus ZDV dual regimen administered to infants for 14 weeks | ||||||

| HIV Transmission at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 50 per 1000 | 61 per 1000 (42 to 89) | HR 1.23 (0.83 to 1.81) | 2013 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Infant Mortality at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 54 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (33 to 73) | HR 0.91 (0.61 to 1.36) | 2013 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| HIV Transmission at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 108 per 10004 | 112 per 1000 (78 to 159)4 | HR 1.04 (0.71 to 1.51) | 1122 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 9 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 48 hours of birth Follow‐up: 9 months | 104 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (86 to 147) | HR 1.09 (0.82 to 1.44) | 2013 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Infant Mortality at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 128 per 10004 | 117 per 1000 (80 to 169)4 | HR 0.91 (0.61 to 1.36) | 1273 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 24 months among those uninfected at birth Follow‐up: 24 months | 199 per 1000 | 199 per 1000 (153 to 257) | HR 1.00 (0.75 to 1.34) | 1122 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Infants with any Severe Adverse Events Follow‐up: 24 | 45 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (53 to 107) | RR 1.66 (1.16 to 2.37) | 2013 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| Infants with Probably Related Severe Adverse Events Follow‐up: 24 months | 6 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (2 to 19) | RR 1.02 (0.33 to 3.15) | 2013 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The aim of the trial was to determine whether extended prophylaxis of infants with nevirapine or with nevirapine plus zidovudine until the age of 14 weeks would decrease the rate of HIV‐1 infection, as compared with single‐dose nevirapine combined with 1 week of zidovudine. The trial was not designed to compare the 2 extended dose regimens. 2 Extended NVP prophylaxis included oral dose of nevirapine (2mg/kg) once daily during week 2, then 4mg/kg once daily during weeks 3‐14. Extended ZDV prophylaxis included oral zidovudine (4mg/kg) twice daily during weeks 2‐5, 4mg/kg three times daily during weeks 6‐8, and 6mg/kg three times daily during weeks 9‐14. 3 Small number of events. 4 Calculated from rate of event times number at risk at 24 months

Summary of findings 4. An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 6 weeks compared to sdNVP for prevention of breastfeeding transmission.

| an extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 6 weeks compared to sdNVP for prevention of breastfeeding transmission | ||||||

| Patient or population: Breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers Settings: Ethiopia, India, Uganda (SWEN trial) Intervention: An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 6 weeks1 Comparison: sdNVP2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| SdNVP | An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 6 weeks | |||||

| HIV Transmission at 6 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 7 days of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 88 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (50 to 94) | RR 0.78 (0.57 to 1.07) | 1887 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Infant Mortality at 6 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 7 days of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 38 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (10 to 32) | RR 0.47 (0.26 to 0.84) | 1887 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 6 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 7 days of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 115 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (62 to 109) | RR 0.72 (0.54 to 0.95) | 1887 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Genotypic Resistance to NVP among Ugandan infants HIV‐infected at 6 weeks ViroSeq | 500 per 1000 | 840 per 1000 (545 to 1000) | RR 1.68 (1.09 to 2.6) | 49 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| Persistance of Genotypic Resistance to NVP at 6 months among Ugandan infants found to be resistant at 6 weeks ViroSeq | 167 per 1000 | 730 per 1000 (175 to 1000) | RR 4.38 (1.05 to 18.28) | 13 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| Genotypic Resistance to NVP among Indian infants HIV‐infected in utero or through peripartum/early‐breastfeeding transmission Standard Population Sequencing | 379 per 1000 | 918 per 1000 (558 to 1000) | RR 2.42 (1.47 to 3.97) | 41 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| Genotypic Resistance to NVP among Indian infants HIV‐infected through late breastfeeding Standard Population Sequencing | 150 per 1000 | 154 per 1000 (30 to 799) | RR 1.03 (0.2 to 5.33) | 33 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| HIV Transmission at 12 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 7 days of birth Follow‐up: 12 months | 104 per 1000 | 93 per 1000 (70 to 122) | RR 0.89 (0.67 to 1.17)4,5 | 1813 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| Infant Mortality at 12 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 7 days of birth Follow‐up: 12 months | 50 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (16 to 42)5 | RR 0.53 (0.32 to 0.85)5 | 2350 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 12 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 7 days of birth Follow‐up: 12 months | 135 per 1000 | 107 per 1000 (82 to 136) | RR 0.79 (0.61 to 1.01)4,5 | 1883 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The extended dose nevirapine regimen was initiated at day 8. The extended regimen consisted of 5mg daily NVP from days 8‐42 2 All mothers received 200mg NVP in labor and all infants received 2mg/kg NVP after birth. 3 Small number of events 4 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1. 5 Estimates are inverse variance‐weighted means of country‐specific risks and risk ratios given in the published text.

Summary of findings 5. An extended ZDV regimen administered to breastfeeding infants for 6 months for prevention of breastfeeding transmission.

| an extended ZDV regimen administered to breastfeeding infants for 6 months for prevention of breastfeeding transmission | ||||||

| Patient or population: breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers Settings: Botswana (Mashi trial) Intervention: an extended ZDV regimen administered to breastfeeding infants for 6 months1 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | An extended ZDV regimen administered to breastfeeding infants for 6 months | |||||

| HIV Transmission at 7 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative at one month after birth Follow‐up: 7 months | 5 per 10002,3 | 25 per 1000 (12 to 53)2,3 | HR 4.77 (2.22 to 10.24)4 | 1123 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6,7,8 | |

| Infant Mortality at 18 months Follow‐up: 18 months | 105 per 10009 | 78 per 1000 (53 to 113)9 | HR 0.73 (0.49 to 1.08)4 | 1179 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6,7,8,10 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 18 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative at one month after birth Follow‐up: 18 months | 91 per 10003,11 | 109 per 1000 (74 to 157)3,11 | HR 1.21 (0.81 to 1.8)4 | 1123 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6,7,8,10 | |

| Infants with Grade 3/4 Signs or Symptoms Follow‐up: 7 months | 169 per 10009 | 125 per 1000 (95 to 166)9 | RR 0.74 (0.56 to 0.98) | 1179 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,7,8,12,13 | |

| Infants with Grade 3/4 Laboratory Abnormalities Follow‐up: 7 months | 142 per 10009 | 242 per 1000 (189 to 308)9 | RR 1.70 (1.33 to 2.17) | 1179 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6,7,8,13 | |

| Infant with Toxicity Events leading to cessation of ZDV | 17 per 10009 | 94 per 1000 (48 to 182)9 | RR 5.53 (2.85 to 10.74) | 1179 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,7,8,12,14 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 In all infants, infant zidovudine syrup was administered twice a day at 4mg/kg from birth until 1 month of age. In the breastfeeding arm, infant zidovudine was administered three times a day at 4mg/kg from 1‐2 months of age, and three times a day at 6mg/kg from 2‐6 months of age (while still breastfeeding). 2 Numerator obtained by taking cumulative number of infants with HIV infection at 7 months minus those that were infected at 1 month 3 Denominator calculated by taking number of live births in each group minus the number of infants at with HIV infection at 1month 4 Hazard Ratio was estimated using a log‐rank analysis. 5 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 6 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 7 The control arm of this study randomized women to exclusively formula feed, with ZDV prophylaxis for 1 month. The control arm did not include breastfeeding infants, so the intervention (extended ZDV prophylaxis during breastfeeding) can not be compared to breastfeeding without ARV prophylaxis. 8 Small number of events. 9 Denominator represents number of live births 10 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1. 11 Numerator obtained by taking cumulative number of infants who had died or become HIV‐infected at 18 months minus those that were HIV‐infected at 1 month 12 This study was not blinded and this outcome was deemed possibly subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 13 The occurrence of any grade 3 (severe) or worse laboratory toxicities and clinical adverse events within infants’ first 7 months of life differed by group. The rates of grade 3 or higher signs or symptoms (17.6% vs 13.1%; P=.03) and of hospitalization (20.3% vs 15.6%; p=0.04) by 7 months were significantly higher among infants in the formula‐ fed group than in the breastfed plus zidovudine group. The rate of grade 3 or higher laboratory abnormality associated with zidovudine toxicity was significantly higher in the breastfed plus zidovudine group than in the formula‐fed group (24.7% vs 14.8%; p<0.001). 14 There were significantly higher rates of infants with toxicity events leading to cessation of ZDV in the breastfed plus zidovudine group that in the formula‐fed group (9.2% vs 1.7%; p=0.001).

Summary of findings 6. An extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers compared to an extended ZDV/3TC/ABC administered to mothers for prevention of breastfeeding transmission.

| an extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers compared to an extended ZDV/3TC/ABC administered to mothers for prevention of breastfeeding transmission | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV‐infected mothers and their breastfeeding infants Settings: Botswana (Mma Bana trial) Intervention: An extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers1 Comparison: An extended ZDV/3TC/ABC administered to mothers2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| An extended ZDV/3TC/ABC administered to mothers | An extended ZDV/3TC/LPV‐r regimen administered to mothers | |||||

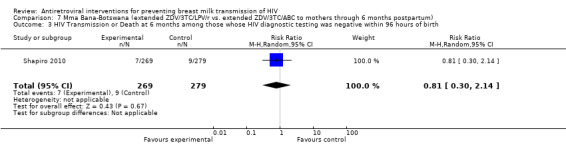

| HIV transmission at 6 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 96 hours of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 7 per 10003 | 2 per 1000 (0 to 31)3 | RR 0.21 (0.01 to 4.3) | 548 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5,6,7,8 | |

| Infant Mortality at 6 months Follow‐up: 6 months | 25 per 10009 | 26 per 1000 (9 to 73)9 | RR 1.05 (0.37 to 2.95) | 553 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5,7,8 | |

| HIV Transmission or Death at 6 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 96 hours of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 32 per 10003,10 | 26 per 1000 (10 to 69)3,10 | RR 0.81 (0.3 to 2.14) | 548 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5,6,7,8,10 | |

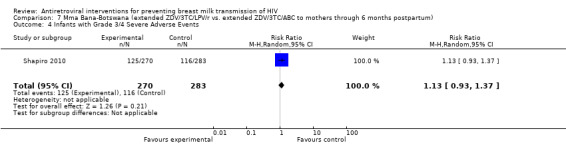

| Infants with Grade 3/4 Severe Adverse Events | 410 per 10009 | 463 per 1000 (381 to 562)9 | RR 1.13 (0.93 to 1.37) | 553 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,8,11 | |

| Maternal Mortality at 6 months Follow‐up: 6 months | 4 per 100012 | 1 per 1000 (0 to 30)12 | RR 0.35 (0.01 to 8.44) | 560 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5,7,8 | |

| Mothers with any Grade 3/4 Severe Adverse Event | 147 per 100012 | 116 per 1000 (75 to 178)12 | RR 0.79 (0.51 to 1.21) | 560 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,7,8,11 | |

| Mothers with Severe Adverse Events Requiring Treatment Modification | 25 per 100012 | 22 per 1000 (7 to 64)12 | RR 0.89 (0.3 to 2.61) | 560 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,7,8,11 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen was administered to mothers from 26‐34 weeks gestation through planned weaning by 6 months postpartum. 2 The extended ZDV/3TC/ABC regimen was administered to mothers from 26‐34 weeks gestation through planned weaning by 6 months postpartum. 3 Denominator= Number of live births‐HIV transmissions in utero. 4 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 5 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 6 As reviewed in Read JS. Diagnosis of HIV‐1 Infection in Children Younger Than 18 Months in the United States. Am Acad Ped 2007:120(6); e1547‐e1562, the sensitivity of DNA PCR for diagnosis of HIV in infants before 30 days is generally significantly less than 100%. For this reason, a baseline window of 4‐6 weeks is recommended to ensure that all in utero and intrapartum transmissions are captured. This study did not use 4‐6 weeks as baseline and as such may include some intrapartum transmissions. While there may be misclassification of timing of infection, there is no reason to believe that it would be differential across study arms. 7 Small number of events. 8 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1. 9 Denominator= Number of live births. 10 The composite measure of HIV transmission or Death at 6 months among those uninfected at birth was not provided by the study authors, and was calculated as follows: Numerator= [Infant mortality at 6m + (HIV transmission at 6 months‐HIV transmission in utero)]. 11 This study was not blinded and this outcome was deemed possibly subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 12 Denominator = Number of women enrolled

Summary of findings 7. An extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers compared to short course ZDV (intrapartum ZDV/3TC/sdNVP) for preventing breastfeeding transmission.

| an extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers compared to short course ZDV (intrapartum ZDV/3TC/sdNVP) for preventing breastfeeding transmission | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV‐infected mothers and their breastfeeding infants Settings: Burkina Faso, Kenya, South Africa (Kesho Bora trial) Intervention: An extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers1 Comparison: Short course ZDV (intrapartum ZDV/3TC/sdNVP)1 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Short course ZDV (intrapartum ZDV/3TC/sdNVP) | An extended ZDV/3TC/LPV/r regimen administered to mothers | |||||

| HIV transmission at 6 months among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 6 weeks after birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 43 per 10002 | 16 per 1000 (6 to 44)2 | HR 0.36 (0.13 to 1.02) | 597 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,5,6 | |

| HIV transmission at 12 months among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 6 weeks after birth Follow‐up: 12 months | 56 per 10002 | 23 per 1000 (9 to 54)2 | HR 0.40 (0.16 to 0.96) | 597 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,7,8 | |

| Infant Mortality at 6 months Follow‐up: 6 months | 41 per 10009 | 36 per 1000 (15 to 85)9 | HR 0.88 (0.36 to 2.11) | 624 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,5,6 | |

| Infant Mortality at 12 months Follow‐up: 12 months | 79 per 10009 | 74 per 1000 (39 to 141)9 | HR 0.94 (0.48 to 1.85) | 624 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,5,6,8 | |

| HIV transmission or Death at 6 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative at 6 weeks after birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 73 per 100010 | 45 per 1000 (22 to 89)10 | HR 0.61 (0.3 to 1.24) | 599 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4,5,6 | |

| HIV transmission or Death at 12 months among those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative at 6 weeks after birth Follow‐up: 12 months | 109 per 10002 | 58 per 1000 (32 to 102)2 | HR 0.52 (0.28 to 0.93) | 599 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3,4,7,8 | |

| Maternal Grade 3/4 Severe Adverse Events | 117 per 100011 | 139 per 1000 (97 to 198)11 | RR 1.19 (0.83 to 1.7) | 824 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,5,6,12,13 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Data are derived from author correspondence. 2 Denominator = Number of breastfed infants at risk at birth as reported by authors for 'HIV infections' ‐ number infected at 6 weeks. 3 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 4 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 5 Small number of events. 6 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1. 7 Very small number of events (n<100) and confidence interval approaches the default threshold of 1. 8 According to the authors, "the last baby was born in November 2008. The database used for the presented analyses was 31March09. At that date, 28% of the participants had not yet completed 12‐month follow‐up." 9 Denominator = Number of breastfed infants at risk at birth as reported by authors for 'deaths'. 10 Denominator = Number of breastfed infants at risk at birth as reported by authors for 'survival' ‐ number infected at 6 weeks. 11 Denominator= Number of women randomized to treatment arm. 12 Data for this outcome on the subset of mothers who ever breastfed was not reported by study authors. Numbers reported here are for the entire sample of women in the study. 13 Per ACTG 1992 Protocol Management Handbook, events of grade 3 or higher classify as "severe".

Summary of findings 8. An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks compared to 1 week of antiretroviral prophylaxis for transmission during breastfeeding.

| an extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks compared to 1 week of antiretroviral prophylaxis for transmission during breastfeeding | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV‐infected mothers and their breastfeeding infants Settings: Lilongwe, Malawi (BAN trial) Intervention: An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks1 Comparison: One week of antiretroviral prophylaxis2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| 1 week of antiretroviral prophylaxis | An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks | |||||

| HIV transmission at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 2 weeks after birth | 51 per 10003 | 26 per 1000 (15 to 45)3 | RR 0.52 (0.3 to 0.89) | 1435 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,7 | |

| Infant mortality at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 2 weeks after birth | 21 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (6 to 30) | RR 0.67 (0.31 to 1.45) | 1517 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5,6,8,9 | |

| HIV transmission or death at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic test was negative at 2 weeks Follow‐up: 28 weeks | 62 per 10003 | 38 per 1000 (23 to 59)3 | RR 0.61 (0.38 to 0.96) | 1435 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,7,10 | |

| Infants with Severe Adverse Events | 126 per 100011 | 140 per 1000 (108 to 1000)11 | RR 1.11 (0.86 to 8.45) | 1517 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6,8,12 | |

| Mothers with Severe Adverse Events | 21 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (25 to 84) | RR 2.19 (1.2 to 4) | 1517 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low7 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mothers initially received Combivir twice daily and NVP once daily for 2 weeks and twice‐daily thereafter until 28 weeks. NVP was replaced with twice‐daily nelfinavir, then twice‐daily lopinavir plus ritonavir because of FDA black‐box warnings (NVP) and availability, safety, and potency concerns (nelfinavir). 2 Mothers in labor and newborns received sdNVP. Mother received Combivir twice‐daily for 7 days. Infants received twice‐daily zidovudine and lamivudine. 3 Demonitor: initially randomized pairs minus infections at 2 weeks 4 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 5 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 6 As reviewed in Read JS. Diagnosis of HIV‐1 Infection in Children Younger Than 18 Months in the United States. Am Acad Ped 2007:120(6); e1547‐e1562, the sensitivity of DNA PCR for diagnosis of HIV in infants before 30 days is generally significantly less than 100%. For this reason, a baseline window of 4‐6 weeks is recommended to ensure that all in utero and intrapartum transmissions are captured. This study did not use 4‐6 weeks as baseline and as such may include some intrapartum transmissions. While there may be misclassification of timing of infection, there is no reason to believe that it would be differential across study arms. 7 Small number of events. 8 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1.0. 9 Very small number of events 10 Confidence interval approaches default threshold of 1.0. 11 Numerator: total percentage of SAEs times initially randomized pairs, as reported in Supplementary Appendix Table 5. 12 This study was not blinded and this outcome was deemed possibly subject to bias due to lack of blinding.

Summary of findings 9. An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks compared to 1 week of antiretroviral prophylaxis for preventing transmission during breastfeeding.

| An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks compared to 1 week of antiretroviral prophylaxis for preventing transmission during breastfeeding | ||||||

| Patient or population: Breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers Settings: Lilongwe, Malawi (BAN trial) Intervention: An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks1 Comparison: One week of antiretroviral prophylaxis2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| 1 week of antiretroviral prophylaxis | An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks | |||||

| HIV transmission at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 2 weeks after birth | 51 per 10003 | 15 per 1000 (8 to 28)3 | RR 0.29 (0.15 to 0.56) | 1447 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5,6,7 | |

| Infant mortality at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 2 weeks after birth | 21 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (6 to 28) | RR 0.62 (0.28 to 1.35) | 1520 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5,6,7,8 | |

| HIV transmission or death at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic test was negative at 2 weeks | 62 per 10003 | 23 per 1000 (14 to 40)3 | RR 0.38 (0.22 to 0.65) | 1447 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,9 | |

| Infants with Severe Adverse Events | 126 per 1000 | 157 per 1000 (122 to 202) | RR 1.25 (0.97 to 1.61) | 1520 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low9 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Infants received a daily dose of NVP, increasing from 10mg to 30mg over the 28 week period. 2 Mothers in labor and newborns received sdNVP. Mother received Combivir twice‐daily for 7 days. Infants received twice‐daily zidovudine and lamivudine. 3 Denominator: initially randomized pairs minus infections at 2 weeks 4 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 5 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 6 As reviewed in Read JS. Diagnosis of HIV‐1 Infection in Children Younger Than 18 Months in the United States. Am Acad Ped 2007:120(6); e1547‐e1562, the sensitivity of DNA PCR for diagnosis of HIV in infants before 30 days is generally significantly less than 100%. For this reason, a baseline window of 4‐6 weeks is recommended to ensure that all in utero and intrapartum transmissions are captured. This study did not use 4‐6 weeks as baseline and as such may include some intrapartum transmissions. While there may be misclassification of timing of infection, there is no reason to believe that it would be differential across study arms. 7 Very small number of events 8 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1.0. 9 Small number of events.

Summary of findings 10. A once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 months compared to a once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 weeks for prevention of breastfeeding transmission of HIV.

| A once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 months compared to a once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 weeks for prevention of breastfeeding transmission of HIV | ||||||

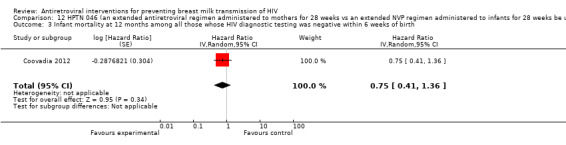

| Patient or population: Breastfeeding infants of HIV‐infected mothers Settings: South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe (HPTN 046 trial) Intervention: A once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 months1 Comparison: A once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 weeks2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| A once‐daily NVP regimen administered for 6 weeks | A once‐daily NVP regmined administered for 6 months | |||||

| HIV transmission at 12 months among infants whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth and whose mothers were not on HAART | 39 per 10003 | 25 per 1000 (13 to 49)4 | HR 0.65 (0.33 to 1.28) | 1078 (1 study5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| HIV transmission at 12 months among all infants whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth | 29 per 10007 | 19 per 1000 (10 to 37)7 | HR 0.66 (0.34 to 1.27) | 1512 (1 study5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| Infant mortality at 12 months among all those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth | 34 per 10007 | 26 per 1000 (14 to 46)7 | HR 0.75 (0.41 to 1.35) | 1522 (1 study5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| HIV transmission or death at 12 months among all infants whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth | 60 per 10007 | 40 per 1000 (26 to 63)7 | HR 0.66 (0.42 to 1.05) | 1522 (1 study5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | |

| Infants with Severe Adverse Events | 829 per 10008 | 829 per 1000 (788 to 871)8 | RR 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 1519 (1 study5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| HIV transmission at 6 months among infants whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth and whose mothers were not on HAART Follow‐up: 6 months | 33 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (6 to 30) | HR 0.41 (0.18 to 0.9) | 1078 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| HIV transmission at 6 months among all infants whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 24 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (5 to 24) | HR 0.46 (0.21 to 0.99) | 1512 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| Infant mortality at 6 months among all those whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 10 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (2 to 10) | HR 0.44 (0.21 to 0.95) | 1522 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| HIV transmission or death at 6 months among all infants whose HIV diagnostic testing was negative within 6 weeks of birth Follow‐up: 6 months | 31 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (12 to 41) | HR 0.70 (0.38 to 1.31) | 1522 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Randomly allocated infants started maskedstudy drug and continued a once‐daily dosing regimenuntil 6 months of age or until cessation of breastfeeding,whichever came first. The nevirapine dose was increasedwith age, ranging from 20 mg once‐daily after 6–8 weeksof age to 28 mg once‐daily after 5–6 months of age. 2 All infants received once‐daily open‐label nevirapine (10 mg/mL oral suspension) for the first 6 weeks of life, after which they were randomized. 3 Denominator is 539 non antiretroviral therapy plus 2 non‐HAART antiretroviral therapy. 4 Denominator is 537 no antiretroviral therapy plus 0 non‐HAART antiretroviral therapy 5 Randomized according to computer‐generatedpermutated block algorithms by site with random blocksizes. Because maternal receipt of anti retroviral drugs canaffect postnatal transmission, infants were stratified bymaternal antiretroviral treatment status at randomisation 6 Few events. 7 "Primary analysis" denominator 8 Infants with at least one adverse event

Summary of findings 11. An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks compared to an extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks for preventing transmission during breastfeeding.

| An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks compared to an extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks for preventing transmission during breastfeeding | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV‐infected mothers and their breastfeeding infants Settings: Lilongwe, Malawi (BAN trial) Intervention: An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks1 Comparison: An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks2 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| An extended NVP regimen administered to infants for 28 weeks | An extended antiretroviral regimen administered to mothers for 28 weeks | |||||

| HIV transmission at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 2 weeks after birth | 15 per 10003 | 26 per 1000 (13 to 53)3 | RR 1.78 (0.88 to 3.59) | 1618 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,7,8 | |

| Infant mortality at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic testing was negative at 2 weeks after birth | 13 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (6 to 32) | RR 1.09 (0.48 to 2.47) | 1701 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,7,8 | |

| HIV transmission or death at 28 weeks among those whose diagnostic test was negative at 2 weeks | 23 per 10003 | 37 per 1000 (21 to 66)3 | RR 1.60 (0.91 to 2.82) | 1618 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4,5,6,7,9 | |

| Infants with Severe Adverse Events | 157 per 100010 | 140 per 1000 (112 to 176)10 | RR 0.89 (0.71 to 1.12) | 1701 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6,7,11 | |

| Mothers with Severe Adverse Events | 16 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (25 to 84) | RR 2.80 (1.53 to 5.11) | 1701 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5,6,9,11 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mothers initially received Combivir twice daily and NVP once daily for 2 weeks and twice‐daily thereafter until 28 weeks. NVP was replaced with twice‐daily nelfinavir, then twice‐daily lopinavir plus ritonavir because of FDA black‐box warnings (NVP) and availability, safety, and potency concerns (nelfinavir). 2 Infants received a daily dose of NVP, increasing from 10mg to 30mg over the 28 week period. 3 Denominator: initially randomized pairs minus infections at 2 weeks 4 This study was not blinded, however this outcome was not deemed subject to bias associated with lack of blinding. 5 As a single study, no comparison study is available to evaluate inconsistency. 6 As reviewed in Read JS. Diagnosis of HIV‐1 Infection in Children Younger Than 18 Months in the United States. Am Acad Ped 2007:120(6); e1547‐e1562, the sensitivity of DNA PCR for diagnosis of HIV in infants before 30 days is generally significantly less than 100%. For this reason, a baseline window of 4‐6 weeks is recommended to ensure that all in utero and intrapartum transmissions are captured. This study did not use 4‐6 weeks as baseline and as such may include some intrapartum transmissions. While there may be misclassification of timing of infection, there is no reason to believe that it would be differential across study arms. 7 Confidence interval crosses the default threshold of 1.0. 8 Very small number of events 9 Small number of events. 10 Numerator: total percentage of SAEs times initially randomized pairs, as reported in Supplementary Appendix Table 5. 11 This study was not blinded and this outcome was deemed possibly subject to bias due to lack of blinding.

Background

By the end of 2012, approximately 35 million people worldwide were living with HIV or had the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). An estimated 260,000 children under the age of 15 years acquired HIV in 2012. However, ARV prophylaxis prevented the acquisition of HIV by an estimated 670,000 children in low and middle‐income countries from 2009 to 2012 (UNAIDS 2013).

MTCT of HIV can occur during three different time periods: antepartum, intrapartum, and postnatally through breastfeeding (De Cock 2000). In settings where breastfeeding is the norm, a significant proportion of MTCT of HIV occurs during breastfeeding. In an individual patient data meta‐analysis of over 3,000 mother‐infant pairs in sub‐Saharan Africa, up to 42% of MTCT of HIV was attributable to breastfeeding (BHITS 2004). Postpartum mothers appear to be at increased risk of incident infection, and thus transmission to the breastfeeding child (De Schacht 2014).

Identification of risk factors for breast milk transmission of HIV has led to the development of interventions to prevent such transmission (Read 2003). Because a longer exposure to breast milk from an HIV‐infected woman is associated with a greater risk of transmission, interventions to shorten the duration of exposure to breast milk have been evaluated: complete avoidance of breastfeeding and early weaning. Mixed breastfeeding, giving infants under the age of 6 months both breast milk and other liquids and/or foods, is associated with a greater risk of transmission. Therefore, avoidance of mixed breastfeeding (and encouragement of exclusive breastfeeding) has been considered to prevent breast milk transmission. Because greater maternal infectivity (e.g., higher maternal viral load in peripheral blood and in breast milk) is associated with a greater risk of breast milk transmission, maternal use of antiretrovirals during breastfeeding has been evaluated as an intervention to reduce transmission to the infant. Finally, improvement in infant defenses against infection with HIV (e.g., ARV prophylaxis to breastfeeding infants) has been assessed. In this review, we focus on the use of antiretroviral prophylaxis for breastfeeding HIV‐infected mothers or their infants to prevent MTCT of HIV through breast milk.

This review was one of a series of analyses prepared at the request of the World Health Organization (WHO) to inform the development of the 2010 prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission (PMTCT) guidelines. The 2010 guidelines (WHO 2010) reflect the findings in this review. Since the publication of the guidelines, this review has been updated with data published after 2009. However, the conclusions have not changed. WHO has subsequently released consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection, including for PMTCT (WHO 2013).

Objectives

The objective of the review is to assess the efficacy and safety of ARV prophylaxis that can be used by HIV‐infected women or given to their infants during breastfeeding to prevent MTCT of HIV.

The specific research questions are:

Mothers: What ARV prophylaxis regimen (and of what duration) should be given to HIV‐infected women to prevent MTCT of HIV through breastfeeding?

Infants: What ARV prophylaxis regimen (and of what duration) should be given to HIV‐exposed infants to prevent MTCT of HIV through breastfeeding?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

HIV‐infected, breastfeeding women and their infants.

Types of interventions

Any ARV prophylaxis for breastfeeding mothers during breastfeeding.

Any infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding lasting more than four weeks.

Types of outcome measures

Distinct outcomes related to HIV transmission, mortality, and drug safety were assessed for maternal and infant ARV regimens.

Primary outcomes

Maternal regimens

HIV‐free survival at six months and any other future time point among their children who were HIV‐uninfected at 4‐6 weeks of age.

HIV acquisition by 12 weeks, six months, 12 months, and 18 months among their children who were HIV‐uninfected at 4‐6 weeks of age.

Maternal severe adverse events (SAEs) including hepatotoxicity in women given NVP with CD4+ counts of 250‐350 cells/mm3 and >350 cells/mm3; renal toxicity with tenofovir, and all other SAEs.

Infant regimens

Mortality at six months, one year, two years and any other future time point among children who were HIV‐uninfected at 4‐6 weeks.

HIV‐free survival at six months and any other future time point among children who were HIV‐uninfected at 4‐6 weeks of age.

Infant acquired antiretroviral resistance.

Infant SAEs (e.g., anemia, neutropenia, other).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal regimens

Maternal mortality at one year, two years, and beyond.

Maternal response to subsequent antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Maternal antiretroviral resistance.

Maternal adherence.

Child mortality at one and two years and any future time point.

Child response to subsequent ART: clinical, virological, immunological.

Infant regimens

HIV acquisition by 12 weeks, six months, 12 months, and 18 months among children who were HIV‐uninfected at 4‐6 weeks of age.

Infant response to subsequent ART: clinical, virological, immunological.

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Group's methods, and searches were performed with the assistance of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Group. We devised a comprehensive, exhaustive search strategy in order to identify all relevant studies in all languages, published or unpublished (including those in press or in progress).

Electronic searches

Journal and trial databases

Electronic searches were undertaken using the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

EMBASE

Literatura Latino‐Americana e do Caribe em Ciencias da Saude (LILACS)

MEDLINE (via PubMed)

Web of Science/Web of Social Science.

With regard to the electronic literature search, the optimal, sensitive search strategy developed by The Cochrane Collaboration and detailed in the Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook (Higgins 2008) was used, in conjunction with search terms identified in Table 12, to identify relevant studies from January 1, 1994 to June 17, 2009. Additional searches were later undertaken through January 14, 2014. See Table 12 for our strategies in searching Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE and PubMed, LILACS, and Web of Science/Web of Social Science. The search strategy was iterative. There were no restrictions on language.

1. Searches.

| PMTCT searches |

| Publication Date from 1994/01/01 to 2014/01/14 |

|

PubMed: HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv‐1*[tw] OR hiv‐2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno‐deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune‐deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) AND (deficiency syndrome[tw])) AND randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR (placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR observational [tw] OR cohort studies [mh] OR case‐control studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR controll* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh]) AND (MOTHER‐TO‐CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MOTHER TO CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (ADULT TO CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (ADULT‐TO‐CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MATERNAL TO CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MATERNAL‐TO‐CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (VERTICAL TRANSMISSION) OR (DISEASE TRANSMISSION, VERTICAL) OR MTCT OR PMTCT OR (Infectious Disease Transmission, Vertical/prevention and control[Mesh] AND HIV Infections/prevention and control[Mesh]) OR (mother[tw] AND HIV Infections/prevention and control[Mesh]) OR ((infant[tw] OR baby[tw]) AND HIV Infections/prevention and control[Mesh]) |

|

EMBASE: (((('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp)) OR (('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp))) OR ((('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp)) OR (('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus infection'/exp)))) OR ((((('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp)) OR (('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp))) OR ((('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp)) OR (('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus'/exp OR 'human immunodeficiency virus'/exp))))) OR (hiv:ti OR hiv:ab) OR ('hiv‐1':ti OR 'hiv‐1':ab) OR ('hiv‐2':ti OR 'hiv‐2':ab) OR ('human immunodeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunodeficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immuno‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immuno‐deficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immunedeficiency virus':ti OR 'human immunedeficiency virus':ab) OR ('human immune‐deficiency virus':ti OR 'human immune‐deficiency virus':ab) OR ('acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immune‐deficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunedeficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immunodeficiency syndrome':ab) OR ('acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ti OR 'acquired immuno‐deficiency syndrome':ab) AND 'mother‐to‐child transmission' OR 'mother to child transmission' OR 'adult‐to‐child transmission' OR 'adult to child transmission' OR 'maternal‐to‐child transmission' OR 'maternal to child transmission' OR ('vertical transmission'/exp OR 'vertical transmission'/exp) OR ('vertical disease transmission' OR mtct OR pmtct OR 'perinatal transmission') AND [embase]/lim AND [1994‐2014]/py |

|

WEB OF SCIENCE, WEB OF SOCIAL SCIENCE: (TS=HIV OR TS=HIV/AIDS OR TS=AIDS) AND (TS=Mother‐to‐child transmission OR TS=vertical transmission OR TS=mother OR TS=infant OR TS=baby OR TS=perinatal OR TS=postnatal OR TS=prenatal OR TS=antenatal) AND Document Type=(Article OR Meeting Abstract OR Meeting Summary OR Meeting‐Abstract OR Proceedings Paper) Databases=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI Timespan=1994‐2014 |

|

LILACS: (HIV OR VIH OR AIDS OR SIDA OR HIV/AIDS) AND (mother‐to‐child OR PMTCT OR MTCT OR mother OR baby OR infant OR vertical) |

|

COCHRANE “CENTRAL”: (HIV INFECTIONS) OR HIV OR HIV OR HIV‐1* OR HIV‐2* OR HIV1 OR HIV2 OR (HIV INFECT*) OR (HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNEDEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR (HUMAN IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY VIRUS) OR ((HUMAN IMMUN*) AND (DEFICIENCY VIRUS)) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNEDEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNO‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR (ACQUIRED IMMUNE‐DEFICIENCY SYNDROME) OR ((ACQUIRED IMMUN*) AND (DEFICIENCY SYNDROME)) OR (VIRAL SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES) AND (MOTHER‐TO‐CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MOTHER TO CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (ADULT‐TO‐CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (ADULT TO CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MATERNAL‐TO‐CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MATERNAL TO CHILD TRANSMISSION) OR (MTCT OR PMTCT) OR (PERINATAL TRANSMISSION) OR (VERTICAL TRANSMISSION) OR (VERTICAL DISEASE TRANSMISSION) |

Conference abstracts

Abstracts from numerous relevant conferences, including the International AIDS Society (IAS) conferences (2007, 2009, 2011, 2013) and the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) (2008‐2013) were searched.

We searched the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) in an effort to identify ongoing trials.

Searching other resources

Contacting researchers in the field

Experts in the field of HIV prevention were contacted to locate any further studies or relevant conference proceedings not included in the databases to ensure that unpublished studies were included.

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all studies identified by the above methods and examined the bibliographies of any systematic reviews, meta‐analyses, or current guidelines we identified during the search process.

Data collection and analysis

Our data collection and analysis methodology was based on the guidelines set forth in the Cochrane Handbooks of Systematic Reviews (Higgins 2008). The titles, abstracts and descriptor terms of all downloaded material from the electronic searches were read and irrelevant reports discarded to create a pool of potentially eligible studies. Two authors independently inspected each citation (JM and JR, or JM and AB) to determine whether the full article should be acquired. If there was uncertainty, the full article was obtained.

Selection of studies

Two authors independently applied the exclusion criteria. Studies were reviewed for relevance based on study design, types of participants, exposures and outcome measures. Finally, where resolution was not possible because further information was necessary, attempts were made to contact authors to provide further clarification of data. The method of conflict resolution was by consensus.

Data extraction and management

JM, JR, and AB independently extracted the data using the standardized data extraction form. For each included study, the following characteristics were extracted:

Study details: citation, start and end dates, location, study design, and study description.

Assessment of risk of bias: study design, sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, loss to follow‐up, incomplete outcome data and other potential bias.

Participant details: study population eligibility (inclusion and exclusion) criteria, ages, population size, attrition rate, details of HIV diagnosis and disease and any clinical, immunologic or virologic staging or lab information.

Interventions details: drug dose, duration of therapy, comparison group.

Outcome measures: HIV infection status of the child, overall survival, and HIV‐free survival. When infant prophylaxis was administered, infant acquired drug resistance was also assessed. When maternal prophylaxis was administered, maternal mortality and severe adverse events were assessed.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool (Higgins 2008) for assessing risk of bias, we summarized the risk of bias in each study into a table.

For trials, the Cochrane tool assesses risk of bias in individual studies across six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other potential biases.

Sequence generation

Adequate: investigators described a random component in the sequence generation process, such as the use of random number table, coin tossing, card or envelope shuffling, etc.

Inadequate: investigators described a non‐random component in the sequence generation process, such as the use of odd or even date of birth, algorithm based on the day or date of birth, hospital, or clinic record number.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of the sequence generation process.

Allocation concealment

Adequate: participants and the investigators enrolling participants cannot foresee assignment (e.g., central allocation; or sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes).

Inadequate: participants and investigators enrolling participants can foresee upcoming assignment (e.g., an open random allocation schedule, a list of random numbers); or envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of the allocation concealment or the method not described.

Blinding

Adequate: blinding of the participants, key study personnel, and outcome assessor, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. No blinding in the situation where non‐blinding is not likely to introduce bias.

Inadequate: no blinding or incomplete blinding when the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of adequacy or otherwise of the blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Adequate: no missing outcome data, reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome, or missing outcome data balanced in number across groups.

Inadequate: reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in number across groups or reasons for missing data.

Unclear: insufficient reporting of attrition or exclusions.

Selective reporting

Adequate: a protocol is available which clearly states the primary outcome as the same as in the final trial report.

Inadequate: the primary outcome differs between the protocol and final trial report.

Unclear: no trial protocol is available or there is insufficient reporting to determine if selective reporting is present.

Other forms of bias

Adequate: there is no evidence of bias from other sources.

Inadequate: there is potential bias present from other sources (e.g., early stopping of trial, fraudulent activity, extreme baseline imbalance, or bias related to specific study design).

Unclear: insufficient information to permit judgment of adequacy or otherwise of other forms of bias.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgments about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Quality of evidence

We assessed the quality of evidence with the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008), defining the quality of evidence for each outcome as “the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the quantity of specific interest” (Higgins 2008). The quality rating across studies has four levels: high, moderate, low or very low. RCTs are initially categorized as high quality but can be downgraded; similarly, other types of controlled trials and observational studies are initially categorized as low quality but can be upgraded. Factors that decrease the quality of evidence include limitations in design, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, imprecision of results or high probability of publication bias. Factors that can increase the quality level of a body of evidence include a large magnitude of effect, if all plausible confounding would lead to an underestimation of effect and if there is a dose‐response gradient.

Measures of treatment effect

We used Review Manager 5 provided by the Cochrane Collaboration for statistical analysis and GRADEpro software (GRADEpro 2008) to produce GRADE Summary of Findings tables and GRADE evidence profiles.

We used hazard ratios (HRs) or risk ratios (RRs) as appropriate, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual infant.

Dealing with missing data

There were no missing data; we did not contact study authors.

Assessment of reporting biases

Using comprehensive search strategies, we minimized the likelihood of reporting biases. Our search included published and unpublished scientific articles, and covered many types of databases. It also included foreign language publications.

Data synthesis