Summary

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a relatively common and genetically heterogeneous structural birth defect associated with high mortality and morbidity. We describe eight unrelated families with an X-linked condition characterized by diaphragm defects, variable anterior body-wall anomalies, and/or facial dysmorphism. Using linkage analysis and exome or genome sequencing, we found that missense variants in plastin 3 (PLS3), a gene encoding an actin bundling protein, co-segregate with disease in all families. Loss-of-function variants in PLS3 have been previously associated with X-linked osteoporosis (MIM: 300910), so we used in silico protein modeling and a mouse model to address these seemingly disparate clinical phenotypes. The missense variants in individuals with CDH are located within the actin-binding domains of the protein but are not predicted to affect protein structure, whereas the variants in individuals with osteoporosis are predicted to result in loss of function. A mouse knockin model of a variant identified in one of the CDH-affected families, c.1497G>C (p.Trp499Cys), shows partial perinatal lethality and recapitulates the key findings of the human phenotype, including diaphragm and abdominal-wall defects. Both the mouse model and one adult human male with a CDH-associated PLS3 variant were observed to have increased rather than decreased bone mineral density. Together, these clinical and functional data in humans and mice reveal that specific missense variants affecting the actin-binding domains of PLS3 might have a gain-of-function effect and cause a Mendelian congenital disorder.

Keywords: PLS3, plastin; fimbrin; actin-binding protein; congenital diaphragmatic hernia; X-linked; abdominal hernia; umbilical hernia; omphalocele

In eight families where males are affected by congenital diaphragmatic hernia, we found variants in PLS3 on the X chromosome. This gene was initially associated with severe osteoporosis in males. Different molecular mechanisms are at play to explain that these two diseases are associated with the same gene.

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a common structural birth defect occurring in 1 out of 3,000 live births in the United States. Anatomically, CDH is characterized by incomplete formation or muscularization of the developing diaphragm, the most important respiratory muscle, together with lung hypoplasia. It is a severe birth defect with an estimated mortality of 20%–50% despite advanced medical and surgical care. The most frequent and severe clinical complications are neonatal respiratory distress and hypertension of the pulmonary circulation, both of which can be refractory to standard treatments. Symptomatic infants with CDH require surgical intervention and often need extended stays in neonatal intensive care units and multiple invasive procedures, including the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Among survivors, respiratory complications, neurodevelopmental deficits, and feeding difficulties requiring life-long medical attention are common.1

The genetic causes of CDH, like other structural birth defects, are highly heterogeneous.1,2 The most frequently identified genetic causes of sporadic CDH are recurrent chromosome abnormalities1,2,3,4 and deleterious de novo single-gene variants.5,6,7,8 Familial CDH is thought to be rare because of the historically high morbidity and mortality in affected individuals, especially in syndromic forms, which affect reproductive fitness. However, studies of familial cases have revealed important human CDH-contributing loci.9,10,11 Several lines of evidence suggest the existence of X-linked loci for CDH: kindreds showing a pattern consistent with X-linked inheritance, a slightly increased male-to-female ratio among affected individuals,12,13 and the occurrence of diaphragmatic defects in several X-linked syndromic conditions.1,2

We describe eight unrelated families with inherited or de novo missense variants in the X-linked gene PLS3, which encodes plastin 3 (also known as T-plastin), an actin-bundling protein. The actin cytoskeleton is a dynamic network that is important for multiple cellular processes in eukaryotes. Actin structures have distinct intracellular localization and are bound to different actin cross-linking proteins, among which are actin-bundling proteins of the plastin family.14,15 PLS3 encodes one of the three vertebrate plastin proteins, which bundle together adjacent actin filaments in a calcium-responsive manner. Plastin proteins contain an N-terminal calcium-binding region and two C-terminal actin-binding domains, which are each composed of two calponin homology domains. Each actin-binding domain binds to adjacent actin filaments, thereby linking them into bundles16 forming specialized actin structures, such as stress fibers, filopodia, lamellipodia, and microvilli.15 Plastin proteins play important roles in a wide array of cellular processes and have been implicated in multiple human diseases.15,17

Loss-of-function (LoF) variants and deletions in PLS3 have been reported previously in families with X-linked osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures (MIM: 300910).17,18,19 Affected males present with childhood osteoporosis and fractures of the axial and appendicular skeleton, whereas the bone phenotype in carrier females ranges from normal bone density to early-onset osteoporosis.18 The CDH-associated PLS3 variants all affect residues in the actin-binding domains of the protein. In contrast to osteoporosis-associated PLS3 variants, which are predicted to result in LoF,17 CDH-associated PLS3 variants are predicted to alter actin binding without causing major conformational changes in the protein in silico. We also generated a knockin mouse model of one of our study’s variants (c.1497G>C [p.Trp499Cys]) that showed variable perinatal lethality, diaphragm and abdominal-wall defects, and increased bone mineral density. These data support a pathophysiologic mechanism leading to CDH and/or anterior body-wall anomalies with nearly complete penetrance in male probands and variable expressivity in female carriers.

Material and methods

Clinical recruitment

Family 1 was referred to the National Reference Center for Rare Diseases of the Lille University Hospital (Lille, France). Families 2–4 were enrolled in the Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital CDH study (Boston, MA, USA) in accordance with the Partners Human Research Committee and Boston Children’s Hospital clinical investigation standards (protocols 2000P000372 and 05-07-105R, respectively). Families 5 and 6 were recruited to the Diaphragmatic Hernia Research & Exploration, Advancing Molecular Science (DHREAMS) study in accordance with the institutional review boards (IRBs) at each participating institution and the Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) IRB. Families 7 and 8 were recruited at Baylor College of Medicine according to standards of IRB protocol H-13046. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants in accordance with the local IRB protocol, and specific consent for photography was obtained where applicable. Collaboration between investigators was aided by GeneMatcher.20 Detailed clinical data collection was performed by chart review and, where possible, physical examination by members of the study staff.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from peripheral-blood samples in EDTA with the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue was processed with the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Extracted DNA was quantitated with the Quant-iT Picogreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Next-generation sequencing

Chromosome X exome sequencing was performed at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in family 1 as described previously.21 Whole-exome sequencing (WES) for families 2–4 was performed at the University of Washington Department of Genome Sciences as described previously.6 Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) for families 5 and 6 was processed at the Broad Institute Genomic Services as described previously.22 WES for families 7 and 8 was performed at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center with an Illumina dual indexed, paired-end pre-capture library per the manufacturer’s protocol with modifications (https://www.illumina.com/techniques/sequencing/ngs-library-prep/multiplexing/unique-dual-indexes.html). Libraries were pooled and hybridized to the HGSC VCRome 2.1 plus custom Spike-In design according to NimbleGen’s protocol with minor revisions.23 Paired-end sequencing was performed with the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform. The sample achieved 98% of the targeted exome bases covered to a depth of 20× or greater and had a sequencing yield of 13.2 Gb. Illumina sequence analysis was performed with the HGSC HgV analysis pipeline, which moves data through various analysis tools from the initial sequence generation on the instrument to annotated variant calls (SNPs and intra-read indels).24,25 In parallel to the exome workflow, a SNP Trace panel was generated for a final quality assessment. This included orthogonal confirmation of sample identity and purity via the Error Rate in Sequencing (ERIS) pipeline developed at the BCM-HGSC. Using an “e-GenoTyping” approach, ERIS screens all sequence reads for exact matches to probe sequences defined by the variant and position of interest. A successfully sequenced sample must meet the quality-control metrics of >90% ERIS SNP array concordance and <5% ERIS average contamination rate.

WES and WGS data were processed with GATK Best Practice v4.0. in previously described pipelines.6,7,22 WES interpretation was performed with Seqr (https://seqr.broadinstitute.org/) and/or GEMINI: Integrative Exploration of Genetic Variation and Genome Annotations.26 The following quality filters were used for analysis of both WES and WGS: genotype quality (GQ) > 20, allelic balance (AB) > 25, coding variants with predicted moderate to high impact (including LoF variants [frameshift, nonsense, essential splice site, and in-frame indel] and missense variants with CADD scores > 20),27 and allele frequency < 0.01% in the control population database gnomAD, including any of their subpopulations.28 All rare missense variants were reviewed individually regardless of algorithm predictions of deleterious effect. All reported variants were visualized manually with the Integrative Genome Viewer (IGV; http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv) and validated by Sanger sequencing.

Protein modeling

Structural modeling is based on the N-terminal actin-crosslinking domain structure from human plastin 3 obtained by X-ray diffraction (PDB: 1AOA),29 on the actin-crosslinking core of Arabidopsis fimbrin (PDB: 1PXY) obtained by X-ray diffraction,30 and on the fourth CH domain from human plastin 3 (PDB: IWJC) obtained by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (PDB: 1WJO). Data files can be downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/).

Generation of Pls3 mouse model

All research involving animals complied with protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committees of the Jackson Laboratory and Massachusetts General Hospital. Pls3 mutant mice, containing either the p.Trp499Cys substitution (Pls3em1Bult, referred to as Pls3W499C) or a 14 bp deletion (Pls3em2Bult, referred to as Pls314bpdel) were generated at the Jackson Laboratory. To introduce a Pls3 variant encoding p.Trp499Cys into the mouse genome, we designed S. pyogenes Cas9 gene-editing reagents by using the Benchling software tool (https://www.benchling.com/) to target Pls3 tryptophan codon 499 (transcript ID Pls3-201, ENMUST00000033547). The introduction of a C>G variant at mouse chrX:75793603 (positive strand, GRCm38/mm10) results in a change in codon from tryptophan (TGG) to cysteine (TGC) on the negative strand. A single guide RNA (gRNA) sequence (CCTTGACCTTGGCTGTAGTC) was ordered as an ALT-R crRNA and hybridized with ALT-R tracRNA (IDT, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). A single-stranded oligonucleotide donor to introduce the p.Trp499Cys variant (variant underlined: 5′ AATATACTAAGGGTGAATTCCTATATGCATATTACTCTGACGCTTCCATAGCCAATACTGTGCACGATACCTTCTCATCAGCTGGCAGACTACAGCCAAGGTCAAGGTAGGGTTGCCATCGTTCAGGT-3′) was synthesized as an EXTREmer by Eurofins Genomics (USA). Fertilized mouse embryos were generated by natural mating following superovulation of C57BL/6J females and cultured as described previously.31 Guide RNA, Cas9 protein (IDT), and donor oligos were introduced into C57BL/6J single-cell zygotes by electroporation as previously described.31 Manipulated embryos were immediately transferred into pseudopregnant female mice in order to yield live-born pups. Pls3W499C and Pls314bpdel mice were obtained from the same electroporation experiment as a consequence of different zygotes utilizing different mechanisms of DNA repair. The Pls314bpdel line resulted from a non-homologous end-joining event but was characterized as a useful LoF comparison allele. We backcrossed both Pls3W499C and Pls314bpdel mice to the parental C57BL/6J strain for three generations to demonstrate that their phenotypes segregated with their genotypes.

Pls3 mice were genotyped by PCR with the primers listed in the supplemental information. DNA was isolated from tissues obtained by either ear notching or tail tipping via the HotSHOT method.32 Each 20 mL PCR consisted of 1 mL of DNA, 1 mL of each genotyping primer, 4 mL of 5M betaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 4 mL of 5× Phusion buffer (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA), 2 mL of dNTP mix (10 mM of each dNTP; Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and 0.2 mL of Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA). Reactions were amplified by 28 cycles of PCR with an annealing temperature of 61°C and visualized by electrophoresis on a 1.8% agarose gel. For animals from the Pls3 colonies, PCR reactions were purified with MagBio High Prep PCR magnetic beads (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and subsequently analyzed by Sanger sequencing using primer 9064 (see the supplemental information for primer details). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were generated as described previously.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted from cultured cells or whole embryos according to the standard protocol of a Qiagen RNeasy micro kit. RNA was then reverse transcribed according to the standard protocol of a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was diluted 1:10 in RNase- and DNase-free water and used for 10 μL qPCRs using SYBR Green (Millipore Sigma) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Reactions were run on a 384-well plate on a QuantStudio ViiA7 (Life Technologies) using the standard SYBR Green program. Gene expression levels were normalized against those of Gapdh, and fold changes were calculated via the 2−ΔΔCt method,33 where the expression levels from wild-type cells or embryos were set to 1. All primer sequences are listed in the supplemental information.

Analysis of mouse diaphragm

Mice were collected at embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5; embryos) or postnatal day 0 (P0; neonates), fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C, and dissected for gross visualization of the body wall, diaphragm, and lungs. Photographs were taken with a Nikon AZ100 microscope. Diaphragm phenotypes were scored from photographs of E18.5 or P0 diaphragms, and the investigator was blinded to the genotypes of the animals during the data collection. Abnormalities of the anterior portion of the muscularized diaphragm in mutant mice were quantified by ImageJ via measurement of the distance between the margins of the anterior muscles and normalization to the width of the entire diaphragm at its widest point. Data were visualized in Microsoft Excel with a box-and-whisker plot, and statistical significance was ascertained with a Student’s t test.

Whole-mount staining of the mouse body wall

P0 pups were euthanized and fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. After fixation, the skin was removed under a dissection microscope in 1× PBS. Samples were bleached for 2 h at room temperature in Dent’s bleach (1:2 30% H2O2:Dent’s fix), washed three times in methanol, and stored for 2 weeks in Dent’s fix (1:4 DMSO:methanol) at 4°C. Samples were then washed in PBS, incubated for 1 h in PBS at 65°C, blocked for 1 h in 5% serum and 20% DMSO, and incubated in alkaline phosphatase-conjugated mouse IgG1 antibody to My32 (Sigma #A4335) for 48 h. Staining was then detected with a 1:1 NTMT:NBT/BCIP Substrate Solution (ThermoFisher #34042) for 40 min at room temperature. Images were taken on a Leica M125 stereo microscope. Distances between stained oblique muscles were measured with Adobe Photoshop. Mean distances between stained oblique muscles were compared via Welch’s t test.

Mouse bone densitometry

Wild-type C57BL/6J (the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA; stock 000664), Pls3W499C KI, and Pls314bpdel mice were analyzed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) at 3 and 15 months of age with an UltraFocus scanner (Faxitron, Tuscon, AZ, USA). For this procedure, mice were weighed and anesthetized with continuous inhalation of isofluorane, and four sets of images were acquired at low and high energy. Collected data were analyzed by VisionDXA software (according to the body-minus-head protocol) and reported as total body weight (g), total tissue mass (g), lean tissue mass (g), fat mass (g), percentage of body weight as fat, total body area (cm2), total bone area (cm2), bone mineral content (g), and bone mineral density (g/cm2).

Results

Clinical descriptions

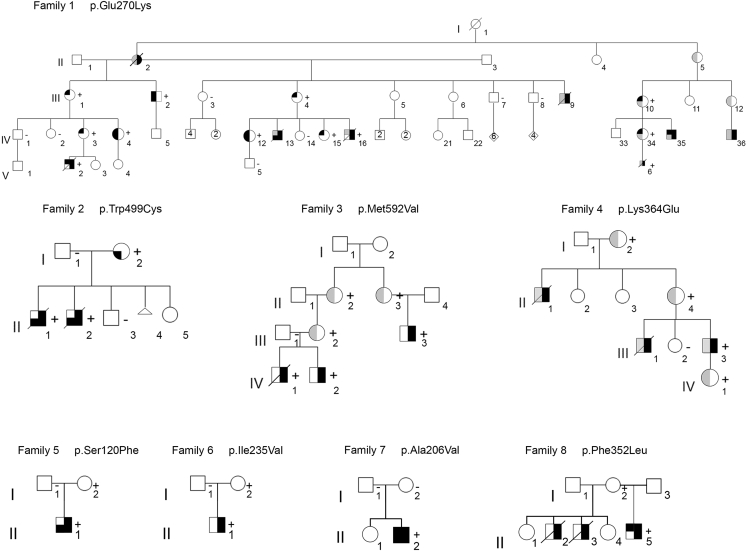

Pedigrees are shown in Figure 1, and clinical details are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome pedigrees

Pedigrees of families 1–8 show an inheritance pattern compatible with X-linked transmission of diaphragmatic defects with or without body-wall defects and hypertelorism. Family members with PLS3 variants confirmed by Sanger sequencing are indicated with a plus sign (+); the minus sign (−) indicates the reference allele. DNA was not available for variant confirmation in every obligate carrier. Symbol nomenclature for confirmed or inferred carriers:  , congenital diaphragmatic hernia;

, congenital diaphragmatic hernia;  , hypertelorism;

, hypertelorism;  , abdominal-wall defect. Colors: black, feature present; gray, undetermined; white, sign absent.

, abdominal-wall defect. Colors: black, feature present; gray, undetermined; white, sign absent.

Table 1.

Clinical information for affected individuals

| Individual | Sex | Diaphragm defect type | Body-wall defect | Dysmorphic features | Neurodevelopmental features | Other features | Alive or deceased | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1-II.2 | F | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | NA | NA | deceased | NT |

| F1-III.1 | F | − | − | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-III.2 | M | − | supraumbilical abdominal hernia | hypertelorism | − | high bone densitometry, genu valgum | alive | + |

| F1-III.4 | F | − | − | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-III.9 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | NA | NA | deceased | NT |

| F1-III.10 | F | − | NA | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-IV.3 | F | − | − | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-IV.4 | F | − | supraumbilical abdominal hernia | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-IV.12 | F | − | supraumbilical abdominal hernia | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-IV.13 | M | left CDH | omphalocele | NA | NA | dextrocardia | deceased | NT |

| F1-IV.15 | F | − | − | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-IV.16 | M | diaphragm agenesis | − | NA | neonatal seizures | bilateral renal pelvis dilation | deceased | + |

| F1-IV.34 | F | − | NA | hypertelorism | − | − | alive | + |

| F1-IV.35 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | hypertelorism | intellectual disability | − | alive | NT |

| F1-IV.36 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | intellectual disability | − | alive | NT |

| F1-V.2 | M | left diaphragm agenesis | − | hypertelorism | hypotonia | left lung segmentation defect, bicuspid aortic valve, two choroid cysts | deceased | + |

| F1-V.6 | M | left diaphragm agenesis | NA | NA | NA | cystic hygroma, left lung segmentation defect | deceased (termination of pregnancy) | + |

| F2-I.2 | F | − | umbilical hernia | − | − | − | alive | + |

| F2-II.1 | M | left posterolateral CDH | supraumbilical abdominal muscle deficiency, cleft sternum | NA | NA | hypoplasia of corpus callosum | deceased | + |

| F2-II.2 | M | left diaphragm agenesis | supraumbilical abdominal muscle deficiency | NA | NA | − | deceased | + |

| F3-III.3 | M | left posterolateral CDH | − | − | unknown | − | alive | + |

| F3-IV.1 | M | left posterolateral CDH | − | NA | NA | − | deceased | + |

| F3-IV.2 | M | left posterolateral CDH | − | − | unknown | hydronephrosis with ureteral abnormality | alive | + |

| F4-II.1 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | NA | NA | deceased | NT |

| F4-III.1 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | NA | NA | deceased | NT |

| F4-III.3 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | − | NA | alive | + |

| F5-II.1 | M | right CDH | absence of right-sided internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles | − | − | − | alive | + |

| F6-II.1 | M | diaphragm eventration | − | − | − | − | alive | + |

| F7-II.2 | M | bilateral ventral CDH with hernia sacs | epigastric skin-covered abdominal-wall defect | hypertelorism, prominent forehead, broad flattened nasal bridge, downslanting palpebral fissures, low-set ears, micrognathia, anteverted nares | − | membranous ventricular septal defect, atrial septal defect, hydronephrosis, unilateral cryptorchidism, unilateral inguinal hernia | alive | + |

| F8-II.2 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | NA | NA | deceased | NT |

| F8-II.3 | M | CDH (unspecified) | NA | NA | NA | NA | deceased | NT |

| F8-II.5 | M | left CDH with hernia sac | none | hypertelorism, low-set right ear, short nose with wide nasal root, downslanting palpebral fissures, widely spaced teeth, high arched palate | intermittent horizontal nystagmus, dilation of lateral ventricles, speech delay, intellectual disability, autism, complex partial seizures | corneal pannus, sensory neural hearing loss, malocclusion, two-vessel umbilical cord | alive | + |

M, male; F, female; NA, not assessed (for body-wall defects, dysmorphic features, or other features) or not applicable (for neurodevelopmental phenotype in deceased individuals); −, feature absent; +, genotype positive for familial PLS3 variant; NT, not tested.

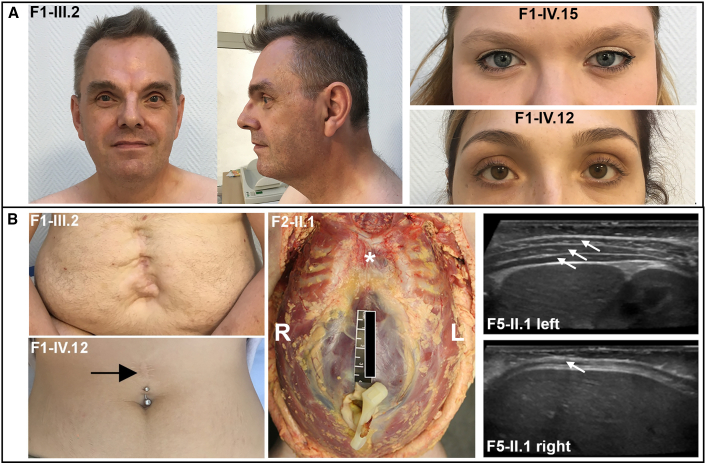

Family 1 is a large family of European ancestry and includes eight affected males and several more mildly affected females. Most affected males died because of diaphragm defects, and one pregnancy was terminated (F1-V.6); however, three affected males survived to adulthood. Additionally, one female family member (F1-II.2) presented with a mild form of CDH that was surgically repaired at age 18 years, and she then lived in good health until 66 years. All surviving affected males and carrier females were noted to have distinct facial features, which include hypertelorism (Figure 2A). Only one affected male from this family did not present with CDH (F1-III.2). This individual had an extensive supraumbilical abdominal hernia that was surgically repaired shortly after birth (Figure 2B). Supraumbilical hernia was also a frequent finding in carrier females (Figure 2B; Table 1). Among the three males who survived to adulthood, the one without CDH had no neurodevelopmental findings, whereas two with CDH had intellectual disability (F1-IV.35 and F1-IV.36). In both cases, the possibility that the intellectual disability was related to neonatal hypoxia-ischemia could not be ruled out. No frequent fractures were observed in the family.

Figure 2.

Facial features and body-wall defects in PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome

(A) Photographs of one affected male and two carrier females from family 1 show hypertelorism.

(B) Anterior body-wall defects observed in affected individuals: (from left to right) surgically corrected large supraumbilical hernia in one male and one female (black arrow) from family 1, supraumbilical muscle deficiency and clefting of the sternum (∗) revealed at the autopsy of an affected male from family 2 (R, right; L, left), and ultrasound images demonstrating congenital hypoplasia or absence of the abdominal-wall musculature on the right side in the affected male from family 5 (compare arrows showing three normal muscle layers on the left and only one muscle layer on the right).

Family 2 is a kindred of European ancestry and includes two affected male siblings born at 36 and 39 weeks of gestation. Both died in the neonatal period with severe malformations that included left-sided posterior CDH in one sibling and complete absence of the left hemidiaphragm in the other, plus a large anterior body-wall defect in both siblings. The body-wall defect consisted of supraumbilical muscle deficiency in both cases and more extensive clefting of the sternum in individual F2-II.1 (Figure 2B). Hypoplasia of the corpus callosum was noted at autopsy in individual II.1, but this was not present in II.2. The mother (F2-I.2) was born with an umbilical hernia that resolved over time without surgical repair and then subsequently recurred as an epigastric abdominal-wall defect after pregnancy. She did not have the same facial features identified in the adult females in family 1, and her inter-pupillary distance was just above the mean for individuals of European ancestry. Chromosome X inactivation studies were performed in a peripheral blood sample from the mother via HpaII digestion at a polymorphic locus in androgen receptor (AR) and showed a random inactivation pattern (data not shown).

Family 3 is of European ancestry and has three affected males (two siblings and one maternal first cousin), all of whom had left-sided posterolateral diaphragm defects. Among the siblings, one (F3-IV.2) underwent additional surgical repair of a ureteral abnormality causing hydronephrosis. Additional anomalies, including body-wall defects, or dysmorphic features were not reported in the affected individuals, and neurodevelopmental outcomes for the survivors are not available.

Family 4 is of European ancestry and has three affected male individuals. Beyond reported surgical repair for CDH, limited phenotypic information is available for the proband (F4-III.3) and his brother (F4-III.1) and maternal uncle (F4-II.1), the latter two of whom are both deceased. Neurodevelopmental or cognitive concerns were not reported for the proband. The proband’s mother and daughter are obligate carriers and are not known to be affected by diaphragmatic defects or any other structural birth defect.

We identified families 5 and 6, each containing one affected male, by screening for PLS3 variants in WGS and WES data from a cohort of 735 CDH-affected individuals and their unaffected parents recruited into the CDH genetics studies of DHREAMS and Boston Children’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital.7 The proband in family 5 is a male of European ancestry and presented with right-sided CDH and outpouching of the right side of the abdominal wall, which had been evident from birth. Abdominal ultrasound performed at 6 months of age showed congenital absence of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles (Figure 2B). The abdominal-wall defect was still noted to be present at follow up at 3 years of age. The proband in family 6 is a male of European ancestry and had a diaphragmatic eventration that required surgical repair followed by re-herniation and no reported body-wall defects. Dysmorphic facial features and significant developmental delays were not noted in either of these probands, and there was also no family history of CDH or other birth defects.

We identified families 7 and 8 by screening for PLS3 variants in WES data from a cohort of individuals recruited into the CDH genetics research study at Baylor College of Medicine. The male proband in family 7 (F7-II.2) is of Hispanic ancestry. He underwent repair of bilateral ventral diaphragmatic hernias, both covered by a hernia sac. He also had a large skin-covered epigastric abdominal-wall defect that had been surgically repaired. His history was also notable for a membranous ventricular septal defect, an atrial septal defect, bilateral hydronephrosis, a right undescended testis, and a right inguinal hernia. Dysmorphisms noted at birth included a prominent forehead, hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, a broad flattened nasal bridge, anteverted nares, low-set ears, micrognathia, a sacral dimple with a hair tuft, and bilateral hypoplastic first toenails. At his most recent follow-up exam at age 16 years, there were no neurodevelopmental concerns (see supplemental note).

Family 8 is of European ancestry and has three affected males. The proband (F8-II.5) had a left-sided posterolateral CDH covered by a hernia sac that had been surgically repaired and a neurodevelopmental disorder (see supplemental note). Other notable findings included a two-vessel umbilical cord, left-sided grade 3 vesicoureteral reflux, intermittent horizontal nystagmus, corneal pannus, and facial dysmorphisms, including hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, a low-set right ear, a short nose with a wide nasal root, widely spaced teeth, and a high arched palate. He had delays in speech development and was later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. At age 6, he was diagnosed with complex partial seizures. A brain MRI showed enlarged lateral ventricles. The proband had two maternal half-brothers (F8-II.2 and F8-II.3) who died in infancy from left-sided CDH. Samples from these individuals were not available for genetic testing. The family history is also notable for other neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the mother and a sensory integration disorder and ADHD in a maternal half-sister.

Genetic studies

Linkage analysis was performed on members of family 1. A logarithm of the odds (LOD) score above 3, indicating positive association with diaphragmatic defects, was obtained for a 3 Mb region on chromosome band Xq23 at chrX:113,889,739–116,906,942 (hg19) (Figure S1). The region includes PLS3, as well as eight other protein-coding genes and several non-coding transcripts.

Chromosome X exome sequencing (family 1), WES (families 2–4, 7, and 8), or WGS (families 5 and 6) identified PLS3 missense sequence variants that were either maternally inherited (in families 1–6 and 8) or de novo (in family 7) (Table 2). In the familial cases, they segregated with the diaphragmatic phenotype and were absent from unaffected male siblings. All variants were validated by Sanger sequencing. Significant chromosome anomalies and copy-number variants were excluded in all probands with clinical or research chromosome microarray analysis. Except for in family 8, no other rare coding candidate variants segregating with the affected individuals were identified. The proband in family 8 carried two additional rare coding variants of uncertain significance in addition to the PLS3 variant: a non-maternally inherited c.52G>C (p.Gly18Arg) variant in SMARCA2 (GenBank: NM_003070) and a maternally inherited c.133G>A (p.Gly45Ser) in SYP (GenBank: NM_003179). A paternal sample was not available for sequencing in this family. SMARCA2 and SYP are both linked to neurodevelopmental phenotypes,34,35 so it is possible that these variants contribute to this individual’s neurological features, which are more severe than those in the other individuals in this report. However, neither SMARCA2 nor SYP has been linked to diaphragm or body-wall defects, and therefore, in combination with the family history consistent with X-linked inheritance, the PLS3 variant best explains the observed clinical phenotype in this proband.

Table 2.

Details of CDH-associated PLS3 variants

| Family | Inheritance | Variant position (GRCh38) | cDNA variant | Protein variant | Allele frequency (gnomAD v2.1) | CADD score (v1.6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | maternal | chrX:115636895G>A | c.808G>A | p.Glu270Lys | 0 | 31 |

| 2 | maternal | chrX:115646521G>C | c.1497G>C | p.Trp499Cys | 0 | 32 |

| 3 | maternal | chrX:115649442A>G | c.1774A>G | p.Met592Val | 0 | 21.8 |

| 4 | maternal | chrX:115643415A>G | c.1090A>G | p.Lys364Glu | 0 | 27.4 |

| 5 | maternal | chrX:115629319C>T | c.359C>T | p.Ser120Phe | 0 | 26.2 |

| 6 | maternal | chrX:115635001A>G | c.703A>G | p.Ile235Val | 0 | 24.8 |

| 7 | de novo | chrX:115634915C>T | c.617C>T | p.Ala206Val | 0 | 25.4 |

| 8 | maternal | chrX:115643379T>C | c.1054T>C | p.Phe352Leu | 0 | 27.8 |

Variant descriptions are provided for the canonical transcript ENST00000420625.2 or GenBank: NM_005032.

All eight PLS3 variants are absent from large population databases (e.g., gnomAD28), alter conserved residues, and are predicted to be pathogenic by in silico algorithms (e.g., CADD27) (Table 2).

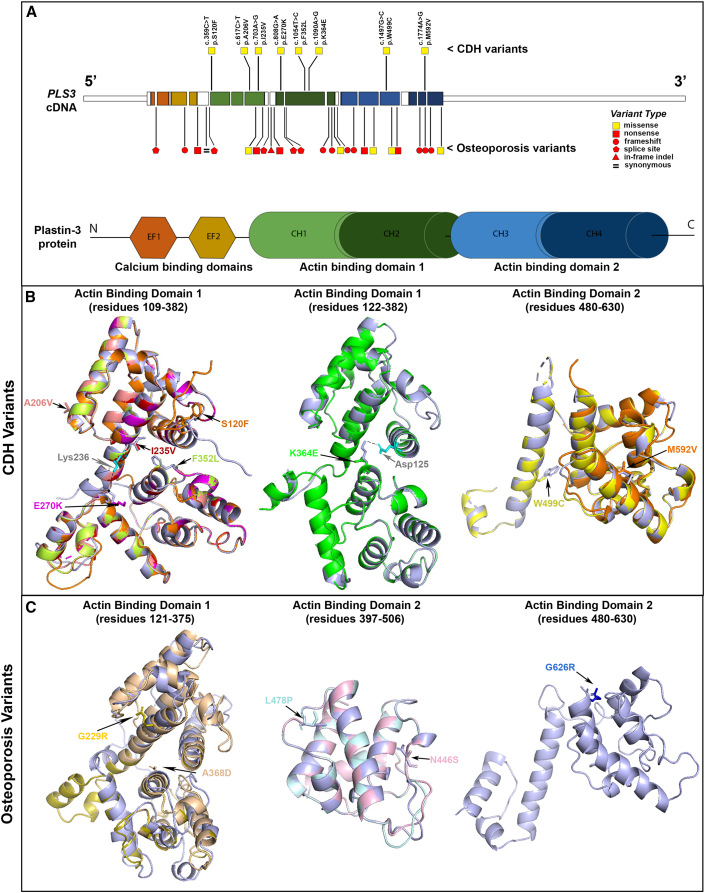

Protein modeling

We used structural modeling of 3D interactions of actin-bundling proteins to address the potential effects of the identified missense variants (Figure 3). PLS3 is characterized by an N-terminal headpiece and two C-terminal actin-binding domains (ABD1 and ABD2), formed by tandem pairs of calponin-homology (CH1–CH4) subdomains.16 All eight variants identified in families with CDH affect residues in ABD1 or ABD2, and none of them are predicted to cause a conformational change in the protein (Figure 3B). The Glu270 and Trp499 residues affected in families 1 and 2, respectively, are contained in the core residues involved in actin binding (actin-binding sites [ABSs]).36,37 The c.808G>A (p.Glu270Lys) variant (family 1) is predicted to disrupt the bond between Gly270 and Lys236 (Figure 3B, magenta), which has been shown to be necessary for binding with F-actin.29 The c.1497G>C (p.Trp499Cys) change (family 2) in the ABD2 domain is predicted to affect the hydrophobic core of the ABS (Figure 3B, yellow). The Met592 residue (family 3) is also part of the ABD2 domain (Figure 3B, orange); however, it does not map to any of the characterized ABSs, and therefore the consequences of the c.1774A>G (p.Met592Val) variant cannot be inferred by structural modeling alone. The c.1090A>G (p.Lys364Glu) variant (family 4) is predicted to cause loss of the hydrogen bond between Lys364 and the Asp125 residue located in the ABS of ABD1 (Figure 3B, green). The c.359C>T (p.Ser120Phe) (family 5), c.703A>G (p. Ile235Val) (family 6), c.617C>T (p.Ala206Val) (family 7), and c.1054T>C (p.Phe352Leu) (family 8) variants are all located at the actin-binding interface of ABD1 (Figure 3B) and, given their locations, might also alter actin binding.

Figure 3.

Structural modeling of human PLS3 variants

(A) Locations and types of PLS3 variants in individuals with CDH and X-linked osteoporosis. The cDNA structure for the canonical PLS3 transcript ENST00000420625.2 or GenBank: NM_005032 is shown at the top, and the color-coded exons depicting the corresponding domains of the Plastin-3 protein are shown at the bottom. The CDH variants are depicted above the cDNA, and the osteoporosis variants16 are depicted below the cDNA. Yellow squares indicate missense variants, and red shapes indicate LoF variants (square, nonsense; circle, frameshift; pentagon, essential splice site; triangle: in-frame indel). The Plastin-3 protein image shows the following domain types: EF, EF-hand domain; CH, Calponin-homology domain.

(B) Predicted PLS3 actin-binding domain protein structures for CDH-associated variants. In these images, the predicted structures of each of the eight variant Plastin-3 proteins (multiple colors) are overlaid on the structure of the native (wild-type) Plastin-3 (lavender). The amino acid alterations are written in the same color as the corresponding protein structure. The overlaid structures demonstrate that none of the CDH variants are predicted to cause a major alteration of protein structure. The dotted lines indicate salt bridges between Lys236 and Glu270 (left) and Asp125 and Lys364 (middle) of the wild-type protein.

(C) Predicted PLS3 actin-binding domain protein structures for osteoporosis-associated missense variants. The predicted structures of five PLS3 variants (yellow, peach, pale blue, pale pink, and blue) are overlaid on the structure of the native protein (lavender), showing that most osteoporosis variants are predicted to cause a major change in protein structure.

Structural modeling was also performed on five missense variants previously linked to osteoporosis.38,39,40,41 The c.685G>A (p.Gly229Arg) and c.1103C>A (p.Ala368Asp) variants alter the conformation of ABD1 with a high deviation value (3,325 Å) (Figure 3C, yellow and peach, respectively). The c.1433T>C (p.Leu478Pro) variant is predicted to be responsible for major alteration of the ABD2 structure given that the proline substitution precludes hydrogen bonding with the adjacent amino acid (Figure 3C, pale blue). Finally, the c.1337A>G (p.Asn446Ser) and c.1876G>A (p.Gly626Arg) substitutions, also in ABD2, show the same topology and the same conformation (Figure 3C, pale pink and blue, respectively). However, conformational changes can be obscured by the fact that the predicted model is not built with the native structure but with a homologous model with a sequence identity superior to 30%. These findings support a model in which osteoporosis-associated missense variants might be responsible for LoF by major alterations in protein structure, whereas CDH-associated missense variants do not alter protein conformation but are instead responsible for specific alteration of actin binding.

Analyses of Pls3 developmental expression

To assist in understanding the role of PLS3 during embryogenesis, we investigated the expression pattern of Pls3 mRNA in mouse embryos during critical times of diaphragm, lung, and body-wall development. In situ hybridizations showed a complex staining pattern in mouse embryos, demonstrating that this gene is regulated in a tissue-specific manner during embryonic development (Figure S2). At E12.5 or E13.5, Pls3 expression was observed in multiple tissues, including the diaphragm, lung mesenchyme, and growing edges of the body wall. Cell-type-specific expression in the developing diaphragm was assessed by RT-PCR of cells cultured from the pleuroperitoneal folds (PPFs) of E13.5 wild-type mice, as described previously.42 Pls3 expression was robust in PPF culture conditions that enrich for both diaphragm fibroblasts and muscle (Figure S2), and expression was also present in both fibroblast (NIH-3T3) and muscle (C2C12) cell lines (Figure S2). These data confirm the expression of Pls3 in the developing diaphragm but are not able to delineate a cell-type-specific expression pattern.

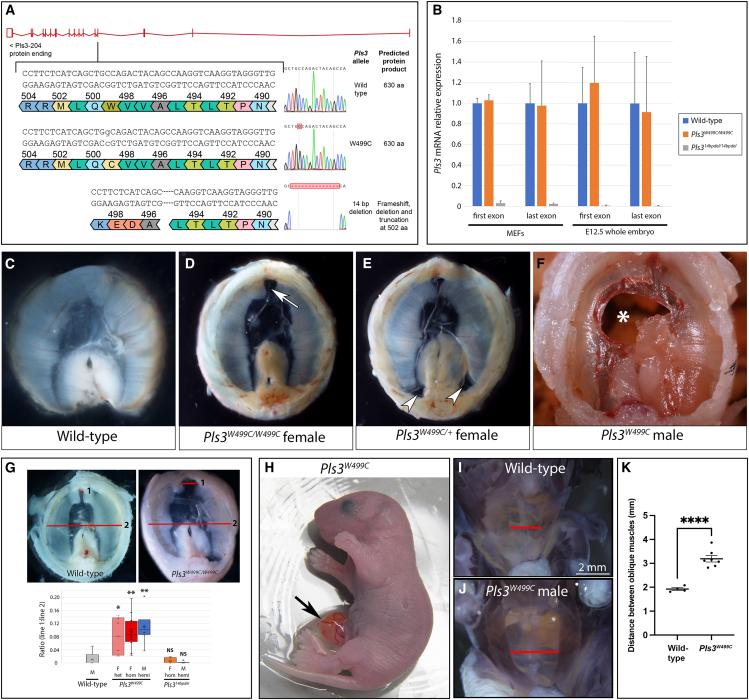

Mouse model of the PLS3 p.Trp499Cys variant

To model the effect of one human CDH-associated variant in vivo, we generated a knockin mouse model, Pls3W499C, expressing the p.Trp499Cys missense variant observed in family 2. Another line, Pls314bpdel, in which the Pls3 variant is predicted to cause a frameshift, was also generated by an alternative DNA-repair mechanism within the same germline-targeting experiment (Figure 4A). Pls3 mRNA levels in Pls3W499C MEFs and E12.5 whole embryos did not differ significantly from wild-type levels (Figure 4B). Pls314bpdel MEFs and embryos showed almost undetectable Pls3 mRNA levels (Figure 4B), indicating that the frameshift variant causes nonsense-mediated decay, and these mice were thus used as a LoF comparison with the Pls3W499C mice.

Figure 4.

Pls3 knockin mouse model

(A) Targeting strategy for Pls3W499C knockin and Pls314bpdel mice, including Sanger sequencing traces. The knockin results in a single amino acid substitution at position 499. The 14 bp deletion results in a deletion and frameshift, predicted to truncate the protein at 502 aa.

(B) Quantitative RT-PCR for Pls3 in MEFs and E12.5 whole embryos from wild-type females (blue), Pls3W499C/W499C females (orange), and Pls314bpdel/14bpdel females (gray). Primers were designed to amplify the first and last exon of Pls3, upstream and downstream of the target site, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of three independent experiments.

(C–F) Images of the diaphragms dissected from E18.5 or P0 wild-type and Pls3W499C mutant mice. Abnormalities seen in the knockin mice include anterior (arrow in D) or posterolateral (arrows in E) amuscular regions and complete holes in the diaphragm (asterisk [∗] in F).

(G) We quantified the anterior diaphragm muscle defect in the mouse models by calculating the ratio between lines 1 and 2 in the example images and visualized it in a box-and-whisker plot depicting data quartiles. Compared with wild-type males, both male and female Pls3W499C mutant mice showed widening of the anterior amuscular space, but male and female Pls314bpdel mutants did not. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

(H) Omphalocele (arrow) in a Pls3W499C mutant at P0.

(I and J) Whole-mount myosin staining to visualize the body-wall musculature in wild-type (I) and Pls3W499C mutants (J) at P0. Red bars show the distance between the external oblique muscles.

(K) Quantification of the distance between the external oblique muscles shows a statistically significant increase in the Pls3W499C knockin compared with controls. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean, centered on the mean of each genotype.

Pls3W499C mice were found at the expected genotype ratios during late gestation, but significantly fewer hemizygous males and homozygous females survived to weaning, and most affected pups died within the first 2 days after birth. In contrast, the Pls314bpdel mice were viable and fertile, consistent with another published Pls3 knockout model.43 The Pls3W499C mutants displayed several phenotypes at late gestation and neonatal time points, including diaphragm abnormalities and anterior body-wall defects, both with reduced penetrance. The diaphragm defects included amuscular diaphragm regions that would typically be well muscularized, particularly at the posterolateral edge and the anterior region adjacent to the sternum (Figures 4C–4E and 4G; Table 3). These amuscular regions had a thin layer of connective tissue reminiscent of a sac-type hernia observed in humans. Less common complete holes in the diaphragm with herniation of the liver were also observed (Figure 4F; Table 3). The abdominal-wall defects included midline protrusion of the intestine into a sac at the site of the umbilicus, similar to omphalocele, in a subset of mutant animals (Figure 4H). All mutants showed thinning of the abdominal-wall muscles with widening of the space between the external oblique muscles (Figures 4I–4K). Neither diaphragm nor abdominal-wall defects were observed in the Pls314bpdel mice (Figure 4G; Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of diaphragm phenotypes in Pls3 mouse models (E18.5–P0)

|

Genotype |

Sex | n | Percentage abnormal |

Type of diaphragm defect |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior amuscular region | Posterolateral amuscular region | Hole in diaphragm with liver herniation | ||||

| Wild-type | M | 5 | 0% | − | − | − |

| Pls3W499C/+ | F | 6 | 50% | 3/6 | − | − |

| Pls3W499C/W499C | F | 16 | 87.5% | 14/16 | 6/16 | 1/16 |

| Pls3W499C | M | 6 | 83.3% | 5/6 | 3/6 | 1/6 |

| Pls314bpdel/14bpdel | F | 6 | 0% | − | − | − |

| Pls314bpdel | M | 6 | 0% | − | − | − |

M, male; F, female; −, feature absent.

We also examined the lungs of Pls3W499C mice because primary defects of the lung mesenchyme are believed to be linked to CDH-associated pulmonary hypoplasia,44,45 but we did not observe any major anomalies in the lung structure or cellular markers (data not shown). MEFs from the Pls3W499C knockin mice were assessed for structural differences in the actin cytoskeleton by fluorescent phalloidin staining, but these studies did not show any reproducible or quantifiable differences (data not shown). Wound-healing assays were also performed on both MEFs and human fibroblasts derived from an individual in family 1, but these did not show any significant changes in cell migration (Figure S3).

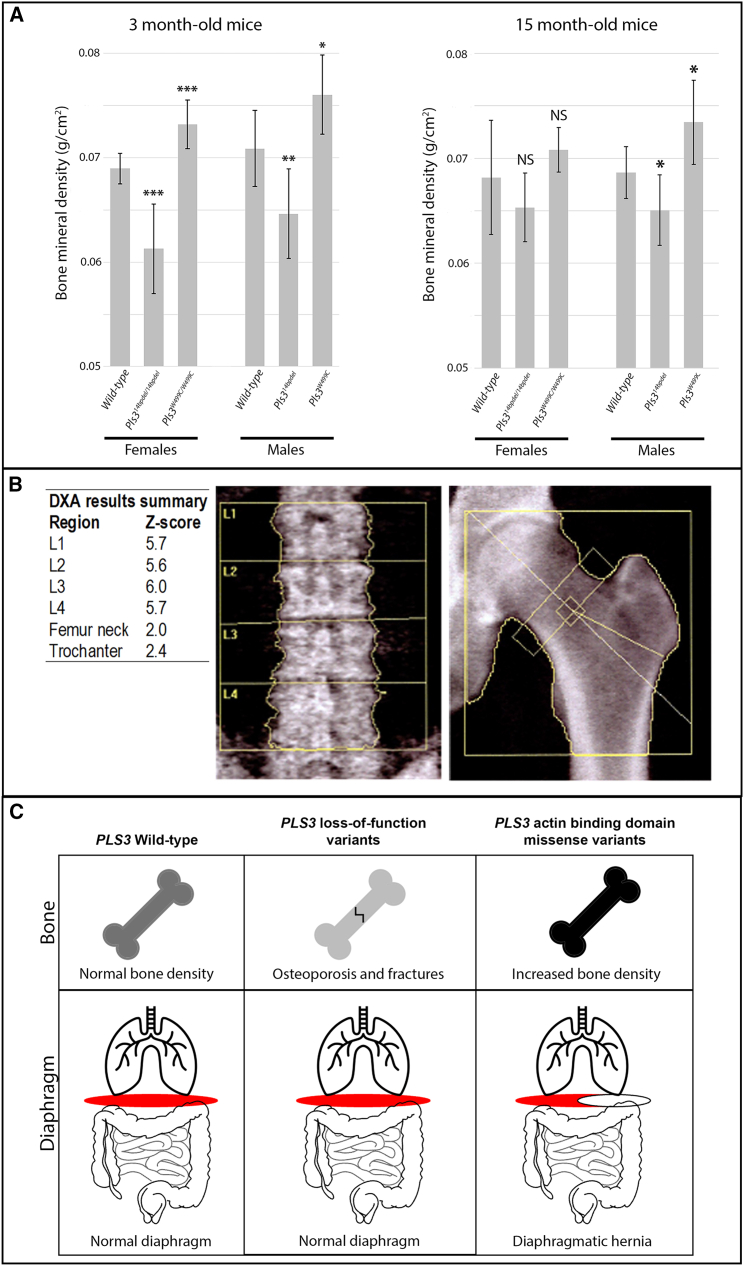

Bone-density studies in mouse and human

To determine the effect of the p.Trp499Cys variant on bone density in mice, we performed DEXA scans on surviving homozygous female and hemizygous male knockin mice (Figure 5A). Compared with age- and sex-matched wild-type control mice, the Pls3W499C knockin mice showed increased bone mineral density at 3 months of age. In contrast, the LoF Pls314bpdel mice showed lower bone mineral density than controls (Figure 5A). A trend toward increased bone mineral density remained in aged Pls3W499C knockin mice (15 months), although the difference was less pronounced than it was in the younger mice (Figure 5A). The body weight and tissue mass of the Pls3W499C and Pls314bpdel mice did not differ significantly from those of age- and sex-matched wild-type controls at either time point (Figure S4).

Figure 5.

Bone-density studies in Pls3 mouse models and humans

(A) Bone-densitometry studies of 3- and 15-month-old Pls314bpdel and Pls3W499C mice compared with age- and sex-matched controls. Bone mineral density values are shown for 3-month-old wild-type females (n = 8), Pls314bpdel homozygous females (n = 7), Pls3W499C homozygous females (n = 6), wild-type males (n = 8), Pls314bpdel hemizygous males (n = 8), and Pls3W499C hemizygous males (n = 8) and for 15-month-old wild-type females (n = 11), Pls314bpdel homozygous females (n = 8), Pls3W499C homozygous females (n = 8), wild-type males (n = 8), Pls314bpdel hemizygous males (n = 8), and Pls3W499C hemizygous males (n = 8). p Values compared with sex-matched controls: ∗p < 0.02, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.002; NS, not significant. Error bars indicate one standard deviation of the mean.

(B) Bone densitometry performed for an affected male from family 1 (F1-III.2) at the age of 51 years. DEXA measured on the left hip and lumbar vertebrae shows increased bone mineral density.

(C) Model to explain the differential effects of PLS3 variant classes on bone and the diaphragm. LoF variants cause osteoporosis and fractures with no effect on diaphragm development. In contrast, missense variants in the actin-binding domain cause increased bone density and diaphragmatic defects.

We investigated bone mineralization in one male proband of family 1 (F1-III.2, age 51) with DEXA, which showed increased bone mineral density with DEXA measurements on the left hip (Z score = +2, T score = +1.2) and lumbar vertebrae (Z score = +5.8, T score = +5.4) (Figure 5B; Table S1). This individual has a history of only one fracture: an open tibial fracture at age 55 after a major trauma. Spinal X-rays performed at age 50 showed no vertebral compression fractures, and phosphocalcic biology was normal. No significant fracture history was reported for any of the affected individuals in any of the eight families.

Discussion

The human and mouse data in this study show that missense variants affecting the actin-binding domains of PLS3 are associated with a congenital disorder characterized by diaphragm defects and variable anterior body-wall defects, for which we propose the name “PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome.” The co-occurrence of diaphragm and ventral body-wall defects is reminiscent of a pattern of malformations affecting the embryonic midline that has been recognized since the 1950s, described by others as pentalogy of Cantrell46 and thoracoabdominal syndrome (THAS; MIM: 313850).47 We identified some commonalities and differences between PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome and these malformation syndromes. Several minor features of THAS, including cardiac defects, cystic hygroma, and hydronephrosis, were each seen in a minority of the individuals we describe with PLS3 variants. The diaphragm defects in the individuals with PLS3 variants are predominantly posterolateral, thus differing from the ventral diaphragm defects described in most cases of pentalogy of Cantrell and THAS. Whereas pentalogy of Cantrell is typically sporadic, THAS has been reported in families consistent with X-linked inheritance.47,48,49 Linkage studies in one family mapped a candidate locus to a different X chromosome region (Xq27) that does not contain PLS3.48 It is therefore likely that variants in several different genes can result in overlapping patterns of malformations.

The Pls3W499C knockin mouse model displayed several types of diaphragm defects, including both anterior and posterolateral amuscular regions, as well as less common complete holes in the diaphragm. In contrast, affected humans displayed primarily posterolateral hernias that manifested as complete holes in the diaphragm with herniation of the abdominal contents. It is notable that sac-type hernias or eventrations were found in at least three individuals, resembling the defects in the mice where a thin connective tissue layer remained. As additional affected individuals are identified, it will be interesting to ascertain whether sac-type hernias or eventrations are more common in PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome than other causes of diaphragm defects. The observed differences in the diaphragm phenotypes between mice and humans could be due to species-specific factors. It is also likely that subtle anterior muscle diaphragm defects, as seen in mice, would be asymptomatic in humans and thus not come to clinical attention.

LoF variants in PLS3 have been described in multiple families to cause X-linked osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures (MIM: 300910).18 LoF of Pls3 in mice also recapitulates the human osteoporosis phenotype.43 Synthesizing the available data, we propose a model (Figure 5C) that explains the effects of different PLS3 variant types on human disease. LoF causes osteoporosis and fractures but has no effect on diaphragm or body-wall development. In contrast, the missense variants that we describe as affecting the actin-binding domain cause increased bone mineral density and have deleterious effects on diaphragm and body-wall development.

Nearly all osteoporosis-related human variants in PLS3 result in protein truncation or abnormal splicing,17 and the few missense and in-frame insertion variants in this disorder render the protein either hyporesponsive or hyperresponsive to calcium or completely disrupt the actin-binding ability in vitro.50 Therefore, LoF or abnormal calcium responsiveness is the major mechanism in osteoporosis, and the results of our in silico modeling for missense osteoporosis variants are consistent with this. In contrast, we hypothesize that CDH-associated PLS3 variants affect actin cytoskeletal dynamics without causing a major change in protein structure and that these cellular functions of PLS3 underlie the anomalies seen in the affected individuals.

The observation of increased bone mineral density in the Pls3W499C knockin mouse model and an affected male from family 1 suggests that these variants might have a gain-of-function effect, at least in bone. A gain-of-function model is also supported by data on the homologous yeast protein, fimbrin, encoded by SAC6. The yeast sac6 suppressor variant p.Trp514Cys (orthologous to the p.Trp499Cys variant identified in family 2) results in a stronger interaction with actin than the wild type does.51 These yeast data also support the pathogenicity of the human p.Trp499Cys variant specifically. Overexpressing wild-type Pls3 in mice by using a transgenic system results in increased bone mineral density but no major congenital anomalies,43 and approximately 5% of the human population also over-expresses PLS3 without any apparent clinical consequences.18 Given these observations, as well as our finding that Pls3W499C knockin mice show Pls3 expression levels equal to those of the wild type, we hypothesize that an abnormal plastin-actin interaction, rather than altered expression levels, is the most likely explanation for the diaphragm and body-wall defects.

Although the precise cellular and biochemical mechanisms by which PLS3 variants result in congenital anomalies remain uncertain, we can formulate some hypotheses. The plastin family of actin bundling proteins has been shown to play multiple diverse cellular roles, including regulation of cell shape, motility, adhesion, endocytosis, vesicle trafficking, and organization of specialized cellular structures, such as microvilli.14,15,17 Pls3 is expressed in multiple tissues during embryonic development, including structures and time points that are critical for the congenital anomalies that are observed. Development of the diaphragm requires complex cellular processes, including migration and differentiation of transient developmental structures, including the pleuroperitoneal folds that form the diaphragm’s connective tissue and central tendon, as well as skeletal muscle precursors derived from the somites.52,53 Cell migration processes are also likely to be critical for the development of the abdominal wall.54 Plastin 3 has been hypothesized to be important for promoting the migration of cells across gaps in the extracellular matrix by stabilizing cellular membrane protrusions.55 Although we were unable to quantify a defect in the actin cytoskeleton or cell migration in cultured cells derived from the Pls3W499C knockin mice, it is possible that the role of Pls3 depends on the developmental context, and its effects might not be identified easily by simple cell-culture models.

This report adds to a body of evidence supporting important roles for PLS3 in multiple tissue types and disease processes.17 In addition to displaying the cardinal findings of diaphragm and body-wall defects, individuals in three families described here also showed dysmorphic facial features, of which hypertelorism was a common finding. It is therefore possible that this syndrome contains a distinctive facial gestalt. Facial dysmorphism, including hypertelorism, has also been described in a subset of individuals with PLS3-associated osteoporosis.39,40,56 A zebrafish plastin 3 knockdown model showed deformation of muscle tissue and craniofacial malformations.18 These observations provide additional support for a role for PLS3 in craniofacial morphogenesis. Although diaphragmatic or abdominal-wall defects are not reported in most individuals carrying osteoporosis-associated variants, some show evidence of muscle and connective-tissue alteration, including blue sclerae, joint laxity, and even muscle weakness.18,56,57 Other minor features are present in our cohort (Table 1) and have been reported in some individuals with osteoporosis-associated variants,18,39,56 although no specific pattern has yet emerged to establish a firm link with PLS3. Of the surviving individuals with PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome for whom we had detailed clinical follow-up, only two adult males in family 1 and the proband in family 8 had neurodevelopmental concerns. In these cases, additional environmental or genetic factors contributing to the neurodevelopmental phenotype could not be ruled out. Thus, neurodevelopmental features do not appear to be a major finding in either PLS3 osteoporosis or PLS3 congenital anomaly syndrome.

Together, our results in both humans and mice show that CDH-associated PLS3 variants cause a syndrome distinct from that caused by the LoF variants identified in individuals with osteoporosis. We hypothesize that these missense variants affect the plastin-actin interaction in a way that affects critical cellular processes during development. The effect of the variants in the diaphragm and body wall might be gain of function, akin to their apparent effect in bone. In the future, detailed biochemical experiments will be helpful for quantifying the effects of these different classes of human variants on PLS3 function in actin binding and calcium responsiveness. Furthermore, research into the effects of variants in the actin-binding domain on cellular processes during development should shed additional light on the mechanism of the congenital anomalies seen in these individuals. These findings have implications for clinical diagnosis and, potentially, therapeutic strategies for both congenital anomalies and bone diseases.

Data and code availability

WES data from families 2–4 has been deposited into the NIH National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database of Genome & Phenotypes (dbGAP: phs000693.v6.p2). WES data from families 7 and 8 will be deposited into NHGRI Genomic Data Science Analysis, Visualization, and Informatics Lab-space (AnVIL). WGS data for families 5 and 6 has been deposited into the data repository of the NICHD Gabriella Miller Kid’s First (GMKF) Program and into dbGAP: phs001110.v2.p1. Chromosome X exome sequencing VCF (variant call format) data for family 1 are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, http://www.nichd.nih.gov) grants 2P01HD068250 (P.K.D.), R01 HD057036 (W.K.C.), and R01 HD098458 (D.A.S.); by National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) grant UM1 HG006542 (J.R.L); and by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grant R35NS105078 (J.R.L.). Sequencing services were partially funded by US federal government contract number HHSN268201100037C to the University of Washington Northwest Genomics Center and by Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program grants X01 HL132366, X01 HL136998, and X01 HL140543 (W.K.C.).

We are grateful to Eric Liao, MD, PhD, for important experiments in the zebrafish model and for discussion that provided insight into the different effects of LoF variants in PLS3. Christine Wooley (the Jackson Laboratory Center for Biometric Analysis) performed the DEXA assay on the laboratory mice. We also acknowledge Dr. Stefan Haas (Department of Computational Molecular Biology of the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics) for computational work on the exome data from family 1.

Declaration of interests

M.L. is currently an employee of, and holds equity in, Illumina Inc. J.R.L. has stock ownership in 23andMe and is a paid consultant for Genome International.

Published: September 25, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.09.002.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Longoni M., Pober B.R., High F.A. In: GeneReviews. Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., Wallace S.E., Bean L.J.H., Mirzaa G., Amemiya A., editors. 1993. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia overview. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu L., Hernan R.R., Wynn J., Chung W.K. The influence of genetics in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin. Perinatol. 2020;44 doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu Q., High F.A., Zhang C., Cerveira E., Russell M.K., Longoni M., Joy M.P., Ryan M., Mil-Homens A., Bellfy L., et al. Systematic analysis of copy number variation associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:5247–5252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714885115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu L., Wynn J., Ma L., Guha S., Mychaliska G.B., Crombleholme T.M., Azarow K.S., Lim F.Y., Chung D.H., Potoka D., et al. De novo copy number variants are associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Med. Genet. 2012;49:650–659. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu L., Sawle A.D., Wynn J., Aspelund G., Stolar C.J., Arkovitz M.S., Potoka D., Azarow K.S., Mychaliska G.B., Shen Y., Chung W.K. Increased burden of de novo predicted deleterious variants in complex congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:4764–4773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longoni M., High F.A., Qi H., Joy M.P., Hila R., Coletti C.M., Wynn J., Loscertales M., Shan L., Bult C.J., et al. Genome-wide enrichment of damaging de novo variants in patients with isolated and complex congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum. Genet. 2017;136:679–691. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1774-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qi H., Yu L., Zhou X., Wynn J., Zhao H., Guo Y., Zhu N., Kitaygorodsky A., Hernan R., Aspelund G., et al. De novo variants in congenital diaphragmatic hernia identify MYRF as a new syndrome and reveal genetic overlaps with other developmental disorders. PLoS Genet. 2018;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao L., Xu L., Yu L., Wynn J., Hernan R., Zhou X., Farkouh-Karoleski C., Krishnan U.S., Khlevner J., De A., et al. Rare and de novo variants in 827 congenital diaphragmatic hernia probands implicate LONP1 as candidate risk gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021;108:1964–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kantarci S., Al-Gazali L., Hill R.S., Donnai D., Black G.C.M., Bieth E., Chassaing N., Lacombe D., Devriendt K., Teebi A., et al. Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:957–959. doi: 10.1038/ng2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu L., Wynn J., Cheung Y.H., Shen Y., Mychaliska G.B., Crombleholme T.M., Azarow K.S., Lim F.Y., Chung D.H., Potoka D., et al. Variants in GATA4 are a rare cause of familial and sporadic congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Hum. Genet. 2013;132:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1249-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longoni M., Russell M.K., High F.A., Darvishi K., Maalouf F.I., Kashani A., Tracy A.A., Coletti C.M., Loscertales M., Lage K., et al. Prevalence and penetrance of ZFPM2 mutations and deletions causing congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Clin. Genet. 2015;87:362–367. doi: 10.1111/cge.12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGivern M.R., Best K.E., Rankin J., Wellesley D., Greenlees R., Addor M.C., Arriola L., de Walle H., Barisic I., Beres J., et al. Epidemiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F137–F144. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanmugam H., Brunelli L., Botto L.D., Krikov S., Feldkamp M.L. Epidemiology and prognosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based cohort study in Utah. Birth Defects Res. 2017;109:1451–1459. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delanote V., Vandekerckhove J., Gettemans J. Plastins: versatile modulators of actin organization in (patho)physiological cellular processes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005;26:769–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shinomiya H. Plastin family of actin-bundling proteins: its functions in leukocytes, neurons, intestines, and cancer. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/213492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volkmann N., DeRosier D., Matsudaira P., Hanein D. An atomic model of actin filaments cross-linked by fimbrin and its implications for bundle assembly and function. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:947–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff L., Strathmann E.A., Müller I., Mählich D., Veltman C., Niehoff A., Wirth B. Plastin 3 in health and disease: a matter of balance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021;78:5275–5301. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03843-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dijk F.S., Zillikens M.C., Micha D., Riessland M., Marcelis C.L.M., de Die-Smulders C.E., Milbradt J., Franken A.A., Harsevoort A.J., Lichtenbelt K.D., et al. PLS3 mutations in X-linked osteoporosis with fractures. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1529–1536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apperley L.J., Albaba S., Dharmaraj P., Balasubramanian M. PLS3 whole gene deletion as a cause of X-linked osteoporosis: clinical report with review of published PLS3 literature. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2023;32:43–47. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobreira N., Schiettecatte F., Valle D., Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:928–930. doi: 10.1002/humu.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu H., Haas S.A., Chelly J., Van Esch H., Raynaud M., de Brouwer A.P.M., Weinert S., Froyen G., Frints S.G.M., Laumonnier F., et al. X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:133–148. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiao L., Wynn J., Yu L., Hernan R., Zhou X., Duron V., Aspelund G., Farkouh-Karoleski C., Zygumunt A., Krishnan U.S., et al. Likely damaging de novo variants in congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients are associated with worse clinical outcomes. Genet. Med. 2020;22:2020–2028. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0908-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Challis D., Yu J., Evani U.S., Jackson A.R., Paithankar S., Coarfa C., Milosavljevic A., Gibbs R.A., Yu F. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinf. 2012;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reid J.G., Carroll A., Veeraraghavan N., Dahdouli M., Sundquist A., English A., Bainbridge M., White S., Salerno W., Buhay C., et al. Launching genomics into the cloud: deployment of Mercury, a next generation sequence analysis pipeline. BMC Bioinf. 2014;15:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karaca E., Harel T., Pehlivan D., Jhangiani S.N., Gambin T., Coban Akdemir Z., Gonzaga-Jauregui C., Erdin S., Bayram Y., Campbell I.M., et al. Genes that affect brain structure and function identified by rare variant analyses of Mendelian neurologic disease. Neuron. 2015;88:499–513. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paila U., Chapman B.A., Kirchner R., Quinlan A.R. GEMINI: integrative exploration of genetic variation and genome annotations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rentzsch P., Schubach M., Shendure J., Kircher M. CADD-Splice—improving genome-wide variant effect prediction using deep learning-derived splice scores. Genome Med. 2021;13:31. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00835-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alföldi J., Wang Q., Collins R.L., Laricchia K.M., Ganna A., Birnbaum D.P., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldsmith S.C., Pokala N., Matsudaira P., Almo S.C. Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic analysis of the N-terminal actin binding domain of human fimbrin. Proteins. 1997;28:452–453. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199707)28:3<452::aid-prot13>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein M.G., Shi W., Ramagopal U., Tseng Y., Wirtz D., Kovar D.R., Staiger C.J., Almo S.C. Structure of the actin crosslinking core of fimbrin. Structure. 2004;12:999–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin W., Dion S.L., Kutny P.M., Zhang Y., Cheng A.W., Jillette N.L., Malhotra A., Geurts A.M., Chen Y.G., Wang H. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in mice by zygote electroporation of nuclease. Genetics. 2015;200:423–430. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.176594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truett G.E., Heeger P., Mynatt R.L., Truett A.A., Walker J.A., Warman M.L. Preparation of PCR-quality mouse genomic DNA with hot sodium hydroxide and tris (HotSHOT) Biotechniques. 2000;29:52–54. doi: 10.2144/00291bm09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappuccio G., Sayou C., Tanno P.L., Tisserant E., Bruel A.L., Kennani S.E., Sá J., Low K.J., Dias C., Havlovicová M., et al. De novo SMARCA2 variants clustered outside the helicase domain cause a new recognizable syndrome with intellectual disability and blepharophimosis distinct from Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome. Genet. Med. 2020;22:1838–1850. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-0898-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarpey P.S., Smith R., Pleasance E., Whibley A., Edkins S., Hardy C., O'Meara S., Latimer C., Dicks E., Menzies A., et al. A systematic, large-scale resequencing screen of X-chromosome coding exons in mental retardation. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:535–543. doi: 10.1038/ng.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bresnick A.R., Janmey P.A., Condeelis J. Evidence that a 27-residue sequence is the actin-binding site of ABP-120. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:12989–12993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine B.A., Moir A.J., Patchell V.B., Perry S.V. Binding sites involved in the interaction of actin with the N-terminal region of dystrophin. FEBS Lett. 1992;298:44–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80019-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fahiminiya S., Majewski J., Al-Jallad H., Moffatt P., Mort J., Glorieux F.H., Roschger P., Klaushofer K., Rauch F. Osteoporosis caused by mutations in PLS3: clinical and bone tissue characteristics. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29:1805–1814. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kämpe A.J., Costantini A., Mäkitie R.E., Jäntti N., Valta H., Mäyränpää M., Kröger H., Pekkinen M., Taylan F., Jiao H., Mäkitie O. PLS3 sequencing in childhood-onset primary osteoporosis identifies two novel disease-causing variants. Osteoporos. Int. 2017;28:3023–3032. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4150-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishi E., Masuda K., Arakawa M., Kawame H., Kosho T., Kitahara M., Kubota N., Hidaka E., Katoh Y., Shirahige K., Izumi K. Exome sequencing-based identification of mutations in non-syndromic genes among individuals with apparently syndromic features. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2016;170:2889–2894. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brlek P., Antičević D., Molnar V., Matišić V., Robinson K., Aradhya S., Krpan D., Primorac D. X-linked osteogenesis imperfecta possibly caused by a novel variant in PLS3. Genes. 2021;12:1851. doi: 10.3390/genes12121851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bogenschutz E.L., Sefton E.M., Kardon G. Cell culture system to assay candidate genes and molecular pathways implicated in congenital diaphragmatic hernias. Dev. Biol. 2020;467:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2020.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neugebauer J., Heilig J., Hosseinibarkooie S., Ross B.C., Mendoza-Ferreira N., Nolte F., Peters M., Hölker I., Hupperich K., Tschanz T., et al. Plastin 3 influences bone homeostasis through regulation of osteoclast activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:4249–4262. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keijzer R., Liu J., Deimling J., Tibboel D., Post M. Dual-hit hypothesis explains pulmonary hypoplasia in the nitrofen model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donahoe P.K., Longoni M., High F.A. Polygenic causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia produce common lung pathologies. Am. J. Pathol. 2016;186:2532–2543. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cantrell J.R., Haller J.A., Ravitch M.M. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1958;107:602–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carmi R., Barbash A., Mares A.J. The thoracoabdominal syndrome (TAS): a new X-linked dominant disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1990;36:109–114. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320360122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parvari R., Carmi R., Weissenbach J., Pilia G., Mumm S., Weinstein Y. Refined genetic mapping of X-linked thoracoabdominal syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;61:401–402. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960202)61:4<401::AID-AJMG18>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parvari R., Weinstein Y., Ehrlich S., Steinitz M., Carmi R. Linkage localization of the thoraco-abdominal syndrome (TAS) gene to Xq25-26. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1994;49:431–434. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320490416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwebach C.L., Kudryashova E., Zheng W., Orchard M., Smith H., Runyan L.A., Egelman E.H., Kudryashov D.S. Osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in plastin 3 lead to impaired calcium regulation of actin bundling. Bone Res. 2020;8:21. doi: 10.1038/s41413-020-0095-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brower S.M., Honts J.E., Adams A.E. Genetic analysis of the fimbrin-actin binding interaction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1995;140:91–101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merrell A.J., Kardon G. Development of the diaphragm -- a skeletal muscle essential for mammalian respiration. FEBS J. 2013;280:4026–4035. doi: 10.1111/febs.12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merrell A.J., Ellis B.J., Fox Z.D., Lawson J.A., Weiss J.A., Kardon G. Muscle connective tissue controls development of the diaphragm and is a source of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:496–504. doi: 10.1038/ng.3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan F.A., Hashmi A., Islam S. Insights into embryology and development of omphalocele. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2019;28:80–83. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garbett D., Bisaria A., Yang C., McCarthy D.G., Hayer A., Moerner W.E., Svitkina T.M., Meyer T. T-Plastin reinforces membrane protrusions to bridge matrix gaps during cell migration. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4818. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18586-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Costantini A., Krallis P.Ν., Kämpe A., Karavitakis E.M., Taylan F., Mäkitie O., Doulgeraki A. A novel frameshift deletion in PLS3 causing severe primary osteoporosis. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;63:923–926. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kämpe A.J., Costantini A., Levy-Shraga Y., Zeitlin L., Roschger P., Taylan F., Lindstrand A., Paschalis E.P., Gamsjaeger S., Raas-Rothschild A., et al. PLS3 deletions lead to severe spinal osteoporosis and disturbed bone matrix mineralization. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017;32:2394–2404. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

WES data from families 2–4 has been deposited into the NIH National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database of Genome & Phenotypes (dbGAP: phs000693.v6.p2). WES data from families 7 and 8 will be deposited into NHGRI Genomic Data Science Analysis, Visualization, and Informatics Lab-space (AnVIL). WGS data for families 5 and 6 has been deposited into the data repository of the NICHD Gabriella Miller Kid’s First (GMKF) Program and into dbGAP: phs001110.v2.p1. Chromosome X exome sequencing VCF (variant call format) data for family 1 are available from the authors upon request.