Abstract

The rise of multi-drug-resistant bacteria that cannot be treated with traditional antibiotics has prompted the search for alternatives to combat bacterial infections. Endolysins, which are bacteriophage-derived peptidoglycan hydrolases, are attractive tools in this fight. Several studies have already demonstrated the efficacy of endolysins in targeting bacterial infections. Endolysins encoded by bacteriophages that infect Gram-positive bacteria typically possess an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal cell-wall binding domain (CWBD). In this study, we have uncovered the molecular mechanisms that underlie formation of a homodimer of Cpl-1, an endolysin that targets Streptococcus pneumoniae. Here, we use site-directed mutagenesis, analytical size exclusion chromatography, and analytical ultracentrifugation to disprove a previous suggestion that three residues at the N-terminus of the CWBD are involved in the formation of a Cpl-1 dimer in the presence of choline in solution. We conclusively show that the C-terminal tail region of Cpl-1 is involved in formation of the dimer. Alanine scanning mutagenesis generated various tail mutant constructs that allowed identification of key residues that mediate Cpl-1 dimer formation. Finally, our results allowed identification of a consensus sequence (FxxEPDGLIT) required for choline-dependent dimer formation—a sequence that occurs frequently in pneumococcal autolysins and endolysins. These findings shed light on the mechanisms of Cpl-1 and related enzymes and can be used to inform future engineering efforts for their therapeutic development against S. pneumoniae.

Keywords: endolysin, Cpl-1, pneumococcus, bacteriophage, antibiotic resistance, cell wall hydrolase

Graphical Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is included in the global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria identified by the World Health Organization (WHO), which require new drugs to be researched and developed.1 Despite the successful global launch of pneumococcal vaccines, the rate of invasive pneumococcal disease is still high in children under 5 years old and in adults aged over 50,2–4 with almost 750,000 deaths in children under the age of 5 in 2019 alone.5,6 Pneumococcal infections can range from simple otitis media or respiratory tract infections to invasive bloodstream infections or meningitis.7 Complicating the management of pneumococcal disease is the remarkable variability among S. pneumoniae strains, with at least 100 capsular serotypes identified to date,8,9 whereas the available vaccines target just a fraction of these serotypes. Furthermore, there has been an increase in antibiotic-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae.10–12 High rates of resistance for several antimicrobials such as penicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and erythromycin have been reported.13,14 Thus, the widespread distribution of antibiotic-resistance genes in bacteria compels us to the post-antibiotic era and makes development of alternative antimicrobial agents one of the highest global priorities for aggressive biological, pharmaceutical, and medical investigations.15

The use of endolysins (also termed enzybiotics), which are bacteriophage-encoded peptidoglycan hydrolases, provides an alternative to small molecule antibiotics.16,17 Endolysins and holins are produced by the invading bacteriophage to lyse the host cell and permit the release of new bacteriophage virions. Endolysins can also be applied exogenously and are alone capable of destroying the Gram-positive bacterial peptidoglycan both rapidly and specifically.18–20 Endolysins derived from bacteriophage that infect Gram-positive bacteria share a similar modular structure with one or more N-terminal catalytic domains (CDs) and a C-terminal cell-wall binding domain (CWBD).17,21–23 The CDs carry the catalytic activity of cleaving various bonds of the peptidoglycan. The CWBDs bind to specific substrates, which are usually carbohydrates or teichoic acids attached to the host peptidoglycan,24 thus providing host specificity.

S. pneumoniae has a unique nutritional requirement for choline and displays this moiety on its wall teichoic acids. Not surprisingly, pneumococcal endolysins and autolysins contain choline binding repeats (CBRs) within their CWBD that bind to the teichoic acids via phosphocholine and, as such, lend specificity of these enzymes to pneumococci and other choline-displaying organisms. Pal is the endolysin from the pneumococcal Dp-1 bacteriophage and contains an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase CD and a CWBD comprising six CBRs followed by a short (17 amino acid) C-terminal tail region.25 Another pneumococcal endolysin, Cpl-1, is derived from the Cp-1 bacteriophage and possesses an N-acetylmuramidase (lysozyme) CD and a CWBD containing six CBRs and a 16 amino acid C-terminal tail.26 Various in vivo studies investigated the potential therapeutic efficacy of Pal and Cpl-1. For example, Pal was shown to reduce S. pneumoniae to undetectable levels in a mouse nasopharyngeal colonization model,27 while Cpl-1 was shown to be effective in killing S. pneumoniae in a mouse otitis media model,28 in a mouse intravenous pneumococcal bacteremia model,29 in a rat endocarditis model, and in a mouse pneumonia model.30

Similar to endolysins, pneumococcal-encoded autolysins also adopt modular structures with a CD and a CWBD that contains CBRs. LytA is one such autolysin that hydrolyzes the pneumococcal cell wall at the end of the stationary growth phase.31 The crystal structure of full-length LytA, containing an N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine “amidase” CD and a CWBD that contains six CBRs, each comprising a β-hairpin, has been published (PDB code: 4X36).32 Notably, LytA forms a dimer in solution in the presence of choline.33 The structure shows this dimerization occurs through a C-terminal β-hairpin 5 and β-hairpin 6 of the last CBR.34 This dimer structure is known as the “tail-to-tail” association of two monomers. The LytA dimer interface is governed by interactions of hydrophobic and aromatic residues. Various LytA truncations have been produced to investigate the importance of the CBRs and the C-terminal tail.35 Constructs lacking the last ~11 amino acids do not form a dimer in the presence of choline and display a significant decrease in catalytic activity.35,36

It has long been known that the Cpl-1 and Pal endolysins also form homodimers upon binding choline in solution, although the molecular mechanisms involved in the dimerization have remained elusive.37,38 Buey et al. modeled the three-dimensional structure of Cpl-1 in solution in its free as well as in its choline-bound states. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was used in combination with the high-resolution three-dimensional crystal structure of the monomer (PDB code: 1H09) to model a solution dimer of Cpl-1.39 Based on these results, the authors hypothesized the dimer interface involves three aromatic residues, Trp210, Phe218, and Tyr238, located at the N-terminus of the CWBD. This “head-to-head” association model of the Cpl-1 dimer contrasts with the C-terminal “tail-to-tail” association observed in the experimental dimer structure of LytA.34 The “head-to-head” interpretation of the Cpl-1 SAXS envelope also disagrees with the recent SAXS-based interpretation of the homologous Pal protein, despite the similar shapes of the two envelops,40 underscoring the inherently low resolution of the SAXS method. Lastly, Resch et al. hypothesized that the Cpl-1 C-terminus mediates dimer formation and constructed a homodimer by introducing cysteine residues at the C-terminal end. The dimer stabilization by disulfide bond formation increased anti-pneumococcal activity and bioavailability in blood.41 Thus, there is ambiguity on the precise nature and location of Cpl-1 dimer formation upon binding choline. In this manuscript, we dissect the molecular mechanisms governing formation of the Cpl-1 dimer and conclusively identified the exact residue(s) required for dimer formation.

RESULTS

The N-Terminus of the CWBD Is Not Involved in Cpl-1 Dimerization but Is Required for Catalytic Activity.

A Superose 12 analytical size exclusion column showed that Cpl-1 forms dimers in the presence of choline, consistent with the published data,37 (Figure 1A). A clear shift in the peak is visible when comparing Cpl-1 alone (light blue curve) to Cpl-1 in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride (dark blue curve). Monomeric Cpl-1 (39.8 kDa, inclusive of a 6X His tag) migrated between the 17 and 44 kDa molecular mass standards while the dimer in choline co-migrated with the 158 kDa molecular mass maker (standards shown in gray), which suggests an extended conformation of the dimer, consistent with previous studies. Buey et al. proposed that dimer formation of Cpl-1 in the presence of choline occurs via three aromatic residues: Trp210, Phe218, and Tyr238.39 To probe these residues, we prepared three individual single alanine mutants (W210A, F218A, and Y238A), three double mutants (W210A:F218A, W210A:Y238A, and F218A:Y238A), and a triple mutant (W210A:F218A:Y238A, referred to as WFY). Six of these mutants were produced and purified to homogeneity, while one of the double mutants (W210A:Y238A) was insoluble. All three single mutants, both soluble double mutants, and the WFY mutant were able to form dimers in the presence of 50 mM choline. The WFY mutant data are shown in Figure 1B. These data refute the Buey et al. hypothesis and suggest other residues are likely involved in the formation of Cpl-1 dimers upon binding choline.

Figure 1. Size exclusion chromatography and cellular activity of wild-type Cpl-1 and the N-terminal CBR W210A:F218A:Y238A triple mutant.

(A) Wild-type full-length Cpl-1 was applied to a Superose 12 analytical size exclusion column in the presence or absence of 50 mM choline chloride. Cpl-1 formed dimers with 50 mM choline chloride (dark blue curve) but was a monomer in PBS with no choline chloride (light blue curve). Standards (gray curve) are 670, 158, 44, 17, and 1.35 kDa. (B) The Cpl-1 W210A:F218A:Y238A (WFY) triple mutant was applied to a Superose 12 column in the presence and absence of 50 mM choline chloride. The triple mutant formed a dimer in the presence of choline (orange curve) and eluted at the same volume as the choline-containing wild-type Cpl-1 sample (dark blue curve). The yellow curve corresponds to the WFY triple mutant in PBS with no choline chloride. (C) Fluorescence microscopy of S. pneumoniae strains DCC1811 (serotype 11) or R36A (capsule-free) when treated with a fluorescent derivative of the Cpl-1 CWBD or the Cpl-1 WFY triple mutant CWBD. Scale bar: 0.5 μm. (D) Cpl-1 WFY mutant displays loss of bactericidal activity against S. pneumoniae DCC1811. Experiments were done in triplicate, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. Asterisks represent level of significance (P < 0.0005) between Cpl-1 and Cpl-1 WFY mutant.

To investigate whether the WFY mutant can bind to the bacterial surface, the CWBDs (residues 200–339) of both wild-type Cpl-1 and its WFY mutant were produced and labeled with AlexaFluor-555. Fluorescence microscopy showed both CWBDs bound with equal intensity to the surface of S. pneumoniae DCC1811, a serotype 11 strain, and R36A, a capsule-free strain (Figure 1C). Yet, a S. pneumoniae DCC1811 lysis assay showed that the Cpl-1 WFY mutant had reduced lytic activity (P < 0.0005) with a reported killing of ~0.2 log unit at 100 μg/mL whereas the wild-type Cpl-1 at the same concentration reduced the number of surviving bacteria by ~4 log units (Figure 1D). Taken together, the results show that none of the single, double, or WFY mutants affected the ability of Cpl-1 to form dimers in the presence of choline or to bind the pneumococcal surface. However, there is a noted defect in antimicrobial activity of the WFY mutant. Whether this defect induces structural changes, which in turn affect catalytic activity, is unknown and requires further investigation.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation and Antimicrobial Activity of Cpl-1 16-Residue C-Terminal Deletion Mutant.

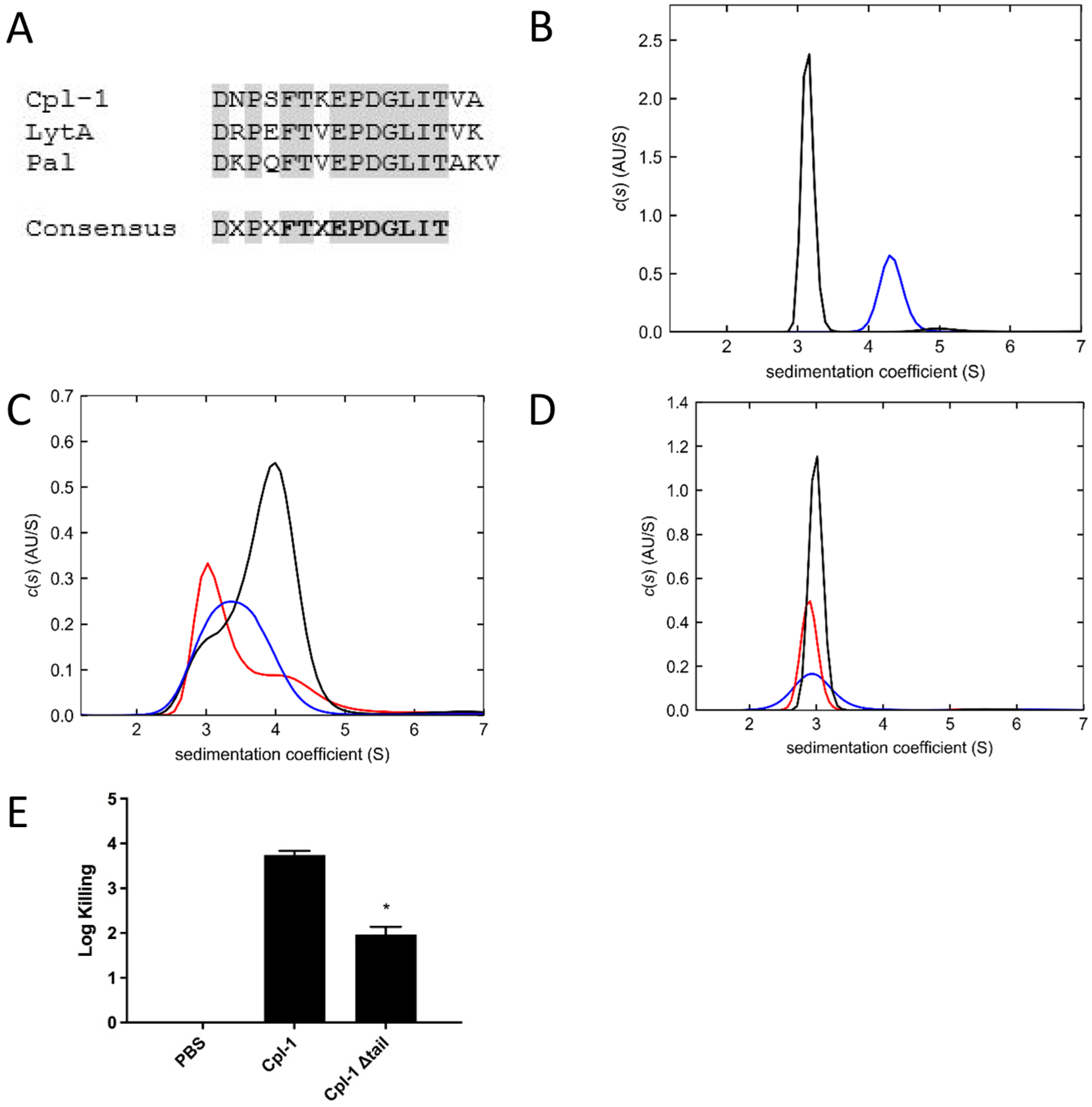

Because Cpl-1 dimer formation via the N-terminus of the CWBD (i.e., the head-to-head model) can be ruled out, we speculate that the dimer interface is mediated by the C-terminal tail region of the protein by analogy to the LytA mode of dimerization (i.e., the tail-to-tail model). The crystal structure of Cpl-1 (PDB code: 1H09) shows that the CWBD comprises two regions, CI and CII.42 The CI region contains the first four CBRs while the CII contains the remaining two CBRs followed by a 16 amino acid C-terminal tail. Markedly, the C-terminal tails of Cpl-1, LytA, and Pal share high sequence identity (Figure 2A). To test this hypothesis, a Cpl-1 deletion mutant was produced, Δtail, which lacks only the 16 C-terminal residues (residues 324–339). Analytical size exclusion experiments measured formation of dimers in the presence of 50 mM choline. However, despite being a pure protein, this mutant displayed multiple retarded peaks on chromatograms, suggesting possible interactions with the column matrix. The same matrix interaction phenomenon was reported previously for C-terminal truncations of LytA.36 Therefore, analytical ultracentrifugation was employed to circumvent the matrix effect.

Figure 2. Analytical ultracentrifugation of Cpl-1 and Cpl-1 Δtail.

(A) C-terminal tail sequence alignment of Cpl-1, LytA, and Pal shows a consensus sequence (gray boxes). Residues in bold indicate consensus sequence after comparing to 76 novel putative endolysins. (B) The c(s) distributions of 14.3 μM Cpl-1 in PBS (black) and 7.5 μM Cpl-1 in PBS plus 50 mM choline (blue) show dimer formation only in the presence of choline. (C) The c(s) distributions of Cpl-1 Δtail in PBS at different concentrations: 10.7 μM (blue), 11.2 μM (red), and 17.8 μM (black). (D) The c(s) distributions of Cpl-1 Δtail at different concentrations in PBS plus 50 mM choline: 4.5 μM (blue), 5.6 μM (red), and 9 μM (black). (E) The Cpl-1 Δtail mutant displays reduced lytic activity compared to wild-type Cpl-1 on S. pneumoniae DCC1811. Data is represented as log-fold killing compared to untreated PBS control. Experiments were done in triplicate, and the error bars represent the standard deviations. Asterisks indicate level of significance (P < 0.05) between Cpl-1 and Cpl-1 Δtail data.

Sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments were conducted in PBS or PBS supplemented with 50 mM choline chloride. In PBS alone, the Cpl-1 wild-type protein had an experimental weight-average sedimentation coefficient of 3.1S with a MWapp of 40 kDa, consistent with its monomeric mass (Figure 2B). In PBS with 50 mM choline chloride, wild-type Cpl-1 sedimented as a single species of 4.4S, with a MWapp of ~76 kDa, suggesting formation of a stable dimer. By contrast, the SV analyses of Cpl-1 Δtail protein in the absence of choline chloride displayed broad sedimentation boundaries with shifting peaks between monomeric 3.1S and dimeric 4.3S forms at all three protein concentrations examined (Figure 2C), indicative of a reversible monomer–dimer equilibrium. In the presence of 50 mM choline chloride, the Cpl-1 Δtail protein exists only as a monomeric 3.0S species (Figure 2D) with a MWapp of 33 kDa at each of three tested concentrations. Although these results prove that the C-terminal 16 residues of Cpl-1 are required for dimer formation in the presence of choline, it remains unclear why the Cpl-1 Δtail protein forms transient interactions in the absence of choline.

Log-fold killing assays were also performed with the Cpl-1 Δtail mutant to determine the effect of the deletion on antimicrobial activity. The Cpl-1 Δtail mutant had significantly lower activity compared with the wild-type Cpl-1 (P < 0.05). In a 1 h log-fold killing experiment, the Δtail mutant caused a ~2 log units decrease in colony forming units (CFUs) of S. pneumoniae strain DCC1811, whereas wild-type Cpl-1 killed the bacteria more efficiently and reduced the CFUs by ~4 log units (Figure 2E).

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis of the Cpl-1 Tail.

To pinpoint the exact residue(s) involved in the formation of the Cpl-1 dimer, five triple-alanine point mutants were made along the 16 amino acid C-terminal Cpl-1 sequence (DNP·SFT· KEP·DGL·ITV·A). All but the ITV construct, which was insoluble, were purified and analyzed on a Superose 12 column in PBS or PBS supplemented with 50 mM choline chloride. The DNP→AAA and KEP→AAA mutants retained the ability of the wild-type protein to form dimers in the presence of choline (Figure 3A). In contrast, the SFT→AAA and DGL→AAA mutants did not form dimers (Figure 3B). The chromatograms for both the SFT mutant (red curve) and the DGL mutant (gray curve) in the presence of choline superimpose with the peak for wild-type Cpl-1 (light blue) in the absence of choline, clearly demonstrating that these mutants do not form dimers. Taken together, the data obtained for the Cpl-1 Δtail mutant and the triple-alanine mutants establish the critical role that the 16 C-terminal residues play in choline-bound Cpl-1 dimer formation, supporting the tail-to-tail association model. Furthermore, both the SFT and DGL triple-alanine mutants displayed reduced lytic activity compared to wild-type Cpl-1, suggesting formation of the dimer is required for full lytic activity (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Size exclusion chromatography of Cpl-1 tail alanine scanning mutagenesis.

(A) The Cpl-1 DNP→AAA mutant was analyzed by a Superose 12 column in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride. This mutant formed dimers in the presence of choline (green curve). The KEP→AAA mutant also formed dimers in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride (brown curve). Both mutants eluted at the same volume as wild-type Cpl-1 in choline (dark blue curve). The light blue curve represents wild-type Cpl-1 in PBS. (B) The Cpl-1 SFT→AAA mutant was analyzed by a Superose 12 column in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride and did not form dimers (red curve). Likewise, the DGL→AAA mutant also did not form dimers in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride (gray curve). Both these mutants eluted at the same volume as wild-type Cpl-1in PBS (light blue curve). Wild-type Cpl-1 in PBS with 50 mM choline chloride is shown as the dark blue curve. (C) All four of the alanine scanning mutants display lytic activity as measured by a log-fold killing assay. The SFT→AAA mutant had significantly reduced lytic activity compared to wild-type Cpl-1, as did the DGL→AAA mutant. The DNP→AAA and KEP→AAA mutants displayed similar lytic activity to wild-type Cpl-1. Asterisks represent level of significance (P < 0.05) between mutant proteins and wild-type Cpl-1. (D) The Cpl-1 F328A mutant was analyzed on the Superose 12 column and did not form a dimer in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride (gold curve), similar to the SFT→AAA mutant (red curve). Wild-type Cpl-1 with (dark blue) and without (light blue) choline chloride are shown for comparison purposes.

The full-length crystal structure of LytA (PDB code: 4X36), containing the tail-to-tail association, reveals an overall “V”-shaped dimer formed along a 2-fold crystallographic axis (Figure 4A,C). Lacking a dimer structure for Cpl-1, the artificial intelligence (AI) program AlphaFold243 was used to model a Cpl-1 dimer. The prediction was performed with ColabFold-multimer44 using MMseq245 with the paired sequence default option and no template. The best ranked model is shown (Figure 4B,D), which has a pLDDT = 90.8, ptmscore = 0.41, and iptm = 0.389. Although the iptm value is low, the same interface for Cpl-1 was generated by AlphaFold2 as that of LytA. All five AlphaFold2 Cpl-1 models exhibit the same tail-to-tail dimer interface and differ mainly by the conformation of the CD-CWBD linker, yielding different orientations between the two domains. Nevertheless, all five models possess an overall “M” shape in contrast to the “V”-shaped LytA. Notably, specific to the C-terminal tail regions, π-stacking is observed between the side chains of Phe307 of each LytA monomer (Figure 4E). The corresponding Cpl-1 residue, Phe328, in the AlphaFold2 model exhibits the same π-stacking (Figure 4F). The Cpl-1 SFT→AAA triple mutant containing Phe328 failed to form dimers in the presence of choline (Figure 3B). To confirm that Phe328 plays a critical role in dimerization, a single site Cpl-1 mutant, F328A, was made. This mutant likewise was unable to form dimers in the presence of choline as monitored by analytical size exclusion chromatography (Figure 3D). Moreover, the F328A mutant retained bacteriolytic activity against pneumococci, albeit diminished compared to wild-type Cpl-1 (Figure S1). Nonetheless, this further supports our triple-alanine scanning mutagenesis results indicating that Cpl-1 monomers are active but formation of a dimer is necessary for full bacteriolytic activity. While other residues in the C-terminal β-hairpin, specifically those in the DGL→AAA mutation, may also contribute to the dimeric state stability, the Phe328 mutant proves that the Cpl-1 dimerization is mediated by the C-terminus of the CWBD rather than the N-terminus. Thus, the sequence homology between LytA and Cpl-1 is also manifested in the common tail-to-tail mode of dimerization of the two proteins.

Figure 4. Comparison between the dimers of LytA crystal structure (PDB code: 4X36) and the model of Cpl-1 generated using the AI program AlphaFold2.

LytA monomers are colored green and cyan (A, C, E), and those of Cpl-1 are colored lavender and light blue (B, D, F). Domain labels are abbreviated as CD (the N-terminal catalytic domain) and CWBD (the C-terminal choline binding domain). Panels A and B show the dimers along the 2-fold symmetry axis in cartoon and molecular surface representations. Panels C and D show the dimer perpendicular to the 2-fold symmetry axis with the same representation as in A and B. Panels E and F show a close-up of the dimer interface perpendicular to the 2-fold symmetry axis, highlighting the interacting Phe307 pair in LytA and the equivalent Cpl-1 Phe328 pair that was mutated in this study.

Cpl-1 Dimerization Depends on Choline Concentration.

The dependence of Cpl-1 dimerization on choline concentration was analyzed by analytical size exclusion chromatography. As seen in Figure 5A, Cpl-1 remains a monomer in the presence of 1 mM choline (green curve). At 10 mM choline, Cpl-1 exists predominantly as a dimer (yellow curve). However, at 5 mM choline, Cpl-1 exists in an equilibrium state between a monomer and a dimer (purple curve). These results suggest an apparent KD value of ~5 mM, which is consistent with the previously reported value of 3.6 mM.37

Figure 5. Choline concentration-dependent formation of Cpl-1 dimers.

(A) Cpl-1 (1.5 mg/mL) was analyzed by Superose 12 analytical size exclusion chromatography in the presence of 1 Mm (green curve), 5 mM (purple curve), or 10 mM (yellow curve) choline chloride. (B) Similar parameters as in A, but Cpl-1 (1.3 mg/mL) in phosphocholine calcium chloride tetrahydrate was used in place of choline chloride at 1 mM (green curve), 5 mM (purple curve), and 10 mM (yellow curve) concentrations.

Choline chloride is considered and used as a proxy for the pneumococcal teichoic acid; however, choline is actually incorporated into the pneumococcal lipoteichoic and wall teichoic acids as phosphocholine.46 Therefore, we measured the binding affinity for Cpl-1 in phosphocholine to compare to choline and were unable to detect a difference between the two. As with choline, Cpl-1 is a monomer in the presence of 1 mM phosphocholine (green curve) and a dimer in 10 mM phosphocholine (yellow curve), and exists in equilibrium between a monomer and dimer in the presence of 5 mM phosphocholine (purple curve) (Figure 5B).

Conserved C-Terminal β-Hairpin Sequence Identifies Pneumococcal Endolysins That Likely Function as Dimers.

The 16 C-terminal amino acid sequences of the pneumococcal CWBDs, which we refer to as the “tail”, are conserved between LytA, Cpl-1, and Pal (Figure 2A), and all three enzymes form dimers in the presence of choline.33,37,38 LytA and Pal have previously been shown to employ a tail-to-tail interaction between two monomers upon choline binding,34,40 and here we confirm that Cpl-1 dimerization is also mediated by the tail. The C-terminal tail of these three enzymes contains a consensus sequence (DxPxFTxEPDGLIT), which can be used to identify putative pneumococcal cell wall hydrolases (i.e., autolysins and endolysins) and to predict their propensity to form dimers in the presence of choline. Recently, Fernandez-Ruiz et al. collated the sequences of 200,000 uncultured viruses and predicted that this collection contains 2,628 novel putative endolysins.47 We further screened these endolysins for the presence of the preliminary pneumococcal CWBD tail consensus sequence, DxPxFTxEPDGLIT, and identified 76 matches that had the exact consensus sequence of FxxEPDGLIT (Figure 2A, bold sequences), all located 2 to 13 residues away from the C-termini (Table S1). Sequence analysis using HMMSCAN, which is part of the HMMER suite,48,49 and clustering based on Pfam families50,51 revealed that 73 of the 76 proteins contain typical autolysin and endolysin CDs, including the Amidase Family 2 and Amidase Family 5 domains and, to a lesser extent, the cysteine, histidine-dependent amidohydrolases/peptidase (CHAP) and glycoside hydrolase family 25 (GH_25) catalytic domains (Figure 6A). The remaining three protein sequences do not contain CDs or other secondary domains but rather are standalone CWBDs.

Figure 6. Novel endolysins identified by the consensus sequence form a dimer in the presence of choline.

(A) Classes of CD domains of the 76 identified putative endolysins with the C-terminal β-hairpin consensus sequence. (B) Dimerization status of SP-CHAP on the Superose 12 column. The protein forms a dimer in the presence of 50 mM choline (orange curve). (C) SP-Amidase forms a dimer in the presence of 50 mM choline (orange curve). (D) SP-GH25 forms a dimer in the presence of 50 mM choline (orange curve). For panels B−D, the blue curves represent the respective proteins analyzed in PBS without choline chloride.

To support the sequence analysis results, we randomly selected three representative CDs from the 76 putative endolysins bearing the conserved sequence motif (SRS numbers correspond to sequence IDs listed in Table S1): SRS019125, containing a CHAP CD and renamed SP-CHAP here; SRS017713, containing an Amidase-2 CD and renamed SP-Amidase here; and SRS018591, containing a GH_25 CD and renamed SP-GH25 here. All three putative endolysins were cloned, expressed, purified, and evaluated for dimer formation in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride by analytical size exclusion chromatography. As seen in Figure 6B, SP-CHAP is a monomer in the absence of choline chloride (blue curve) and forms a dimer in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride (orange curve). Similarly, in Figure 6C,D, both SP-Amidase and SP-GH25, respectively, form dimers in the presence of 50 mM choline chloride. Taken together, the data suggests that most autolysins and endolysins that target the pneumococcal surface have evolved a widespread and conserved mechanism whereby these enzymes form dimers through their C-terminal tails upon binding a choline entity on the bacterial surface.

DISCUSSION

It has been well established that LytA, Cpl-1, and Pal form dimers upon binding choline in solution, and they presumably also dimerize on the pneumococcal surface that displays choline-containing wall teichoic acids.33,37,38 The LytA tail-to-tail mechanism of choline-dependent dimer formation is substantiated by several crystal structures. However, the head-to-head model proposed for Cpl-1 was based on fitting the crystal structure of a choline-free monomeric protein into a SAXS envelope generated in the presence of choline, and the subsequent identification of aromatic residues that potentially formed a non-canonical choline-binding site.39 However, the authors did not confirm that the three aromatic residues on the non-canonical N-terminal β-hairpin are required for dimer formation, nor did they pursue a tail-to-tail interaction hypothesis. Additionally, a crystal structure is a static image of one particular crystal packing arrangement, which may not represent a protein in solution, and the pitfalls of fitting the structure of multi-domain, flexible proteins into a rough SAXS envelope are well documented.52 In contrast, we provide here biophysical evidence, supported by mutagenesis studies, that both disprove the head-to-head model and support the tail-to-tail dimer model of Cpl-1 in the presence of choline.

We have shown that Cpl-1 binds choline with millimolar affinity (Figure 5A), consistent with earlier reports based on circular dichroism studies.37 We also show that Cpl-1 exhibits similar affinity toward phosphocholine, which more closely resembles the native choline in the pneumococcal wall teichoic acids (Figure 5B). However, endolysin CWBDs are generally thought to bind the bacterial surface with much higher affinity than millimolar. Bacillus endolysins bind cell wall polysaccharides with micromolar affinity,53,54 whereas Listeria endolysins bind cell wall polysaccharides with nano-to picomolar affinities.55,56 The discrepancy in binding affinity may be attributable to several factors. First, given that Cpl-1 is predicted to possess five choline binding sites, an avidity effect may increase the apparent low affinity for the pneumococcal surface.57 A similar hypothesis has been developed for PlyCB, the CWBD of the PlyC endolysin that contains eight binding sites.58 A second, and even more likely hypothesis, is that other components of the teichoic acid or moieties on the peptidoglycan itself may be necessary for high-affinity binding, as suggested recently for other pneumococcal choline-binding proteins.59

There is growing evidence that endolysins and other cell wall hydrolases form multimeric structures more often than previously thought. PlyC, an endolysin from the streptococcal C1 phage, is comprised of two independently expressed subunits: PlyCA, which is the catalytic domain (i.e., CD), and PlyCB, the cell-wall binding domain (CWBD). In solution, PlyC multimerizes into eight PlyCB subunits associated with one PlyCA subunit.16 Clostridial endolysins have also been shown to form multimers in solution. Recently, LysB, an endolysin from the prophage of Clostridium botulinum E3 strain Alaska E43, was shown to form a homodimer in solution.60 Endolysin CTP1L that targets Clostridium tyrobu-tyricum, endolysin CS74L that targets Clostridium sporogenes, and endolysin CD27L that targets Clostridium difficile also form multimers. However, these enzymes exist as hetero-tetramers composed of two full-length proteins (i.e., analogs of CD and CWBD) and two individual CWBDs generated by in-frame, internal translation start sites (iTSS) at the beginning of the CWBD coding sequence.61 Endolysins obtained from phages that infect Enterococcus have also been shown to form multimers. Endolysin Lys170 that displays lytic activity on Enterococcus faecalis was shown to form a heterotetramer in solution, wherein a full-length protein interacts with three individually expressed CWBDs, which are also generated by an iTSS.62 Similarly, the enterococcal endolysin LysIME-EF1 forms a holoenzyme with a 1:3 stoichiometric ratio of full-length protein to CWBD.63 Gp2 (LysA) from mycobacteriophage Ms6 lacks an identifiable CWBD, but a truncated version of its CD forms a heterodimer with the full-length protein.64 Likewise, a truncated version of the staphylococcal phage 2638A endolysin ORF007 containing one of two CDs and a CWBD forms a heterodimer with the full-length protein.65 Lastly, Pinto et al. recently performed a bioinformatics search of iTSS sites in putative endolysins and experimentally confirmed at least four new multimeric endolysins, including LysP7951, which adopts a 1:5 CD:CWBD stoichiometry.66 All of the above enzymes fold into their multimeric state at the level of protein translation. Only the pneumococcal enzymes (i.e., Cpl-1, Pal, and LytA) are produced and purified as monomers and require binding to a ligand mimetic of epitopes on the bacterial surface to induce multimerization.

Given the modular nature of endolysin CD and CWBD domains,67 bioengineering and chimeragenesis studies have begun to dominate the endolysin field in recent years. Engineering is beneficial in that the natural bacteriolytic activity of endolysins can be improved by mixing and matching different domains. Domain addition, deletion, mutagenesis, and peptide fusion are just some of the various approaches being currently employed. A recent review by Sao-Jose68 summarizes the generation of several chimeric endolysins along with their benefits compared to the parental enzyme. To this end, knowledge of the dimerization mechanism and the Cpl-1 consensus sequence can have important implications when considering engineering approaches focused on pneumococcal CWBDs. As an example, ClyJ is a chimera containing a CHAP CD derived from PlyCA and a CWBD derived from gp20, which shares a high degree of similarity with that of LytA and is comprised of several CBRs.69 ClyJ was further engineered by modifying the linker sequence between the CD and CWBD to create ClyJ-3, which possesses higher antimicrobial activity than ClyJ, presumably due to differences in linker flexibility.70 As expected, both ClyJ and ClyJ-3 form dimers in the presence of choline. ClyJ-3 was subsequently engineered to truncate the C-terminal tail, yielding ClyJ-3m, which lacks the ability to form a dimer in the presence of choline.71 Surprisingly, this monomeric enzyme has higher lytic activity on S. pneumoniae in vitro and in vivo than either ClyJ-3 and Cpl-1. These data contrast with LytA deletion studies where activity was dramatically reduced with C-terminal deletions,35,36 as well as our own studies deleting the tail region of Cpl-1 (Figure 2E). Also in contrast to the monomeric ClyJ-3m results, Resch et al.41 constructed a Cpl-1 pre-formed dimer by introducing cysteine residues at the start of the C-terminal β-hairpin of the protein. This pre-formed dimer displayed an increased bactericidal activity against S. pneumoniae and also an increased bioavailability by decreasing renal clearance when tested in an in vivo mouse model.

We have proven that Cpl-1 forms a homodimer through interactions with residues in the C-terminal tail in the presence of choline, and we highlighted the consensus motif in this region that is widespread and can be used to predict formation of a dimer in pneumococcal cell wall hydrolases, including both pneumococcal autolysins and bacteriophage endolysins. Nonetheless, the molecular mechanisms that potentiate a signal from the choline binding sites to the tail regions that induces dimer formation is yet to be determined. This knowledge will inform future engineering efforts.

CONCLUSION

S. pneumoniae infections are increasingly associated with antimicrobial resistance. Despite the availability of vaccines, the sheer capsular diversity among S. pneumoniae strains enables them to evade treatment. Endolysins have shown promise in treating Gram-positive bacterial infections. In the present study, we identify the dimerization mechanism for the pneumococcal endolysin Cpl-1 in the presence of choline. We disprove a previous hypothesis that suggested Cpl-1 dimer formation occurs at the N-terminus of its binding domain and subsequently show that its C-terminal tail is involved in formation of the dimer. Using AlphaFold2 modeling combined with experimental mutagenesis studies, we establish residue Phe328 as crucial to formation of the Cpl-1 dimer in the presence of choline. In addition, we identify a consensus sequence required for choline-dependent dimer formation, one that is frequently observed in pneumococcal endolysins and autolysins. Our findings illustrate the molecular mechanisms involved in dimer formation which can help guide future engineering approaches for endolysins targeting S. pneumoniae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this work were routinely grown at 37 °C unless otherwise noted. S. pneumoniae DCC1811, a serotype-11-capsulated strain,72 or S. pneumoniae R36A, a capsule-free strain,73 was grown with 5% CO2 in Todd Hewitt Broth supplemented with 1% yeast extract (THY) without shaking, or on THY plates. Escherichia coli DH5α and BL21 (DE3) strains were grown in Lysogeny Broth (LB) or on LB plates supplemented with ampicillin or kanamycin.

Cloning and Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

The Cpl-1 used in this study was codon-optimized and synthesized (GeneArt). The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. A 6X-His tag was added to the C-terminal end of each protein. The Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from New England Biolabs was used to generate all point mutants, and the manufacturer’s instructions were followed for all steps. Resulting mutants were confirmed by sequencing (Psomagen) before being transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein expression. The pBAD24 and pET28a plasmids were used for protein expression. The ApE program (University of Utah) was used for DNA sequence analysis and manipulations.

Table 1.

Primers

| Primer Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Cpl1 W210A Fwd | 5’- CAAGGGGTGGGCGTTCAGACGAA-3’ |

| Cpl1 W210A Rev | 5’- CTGTCTTGTTTCCACGTTCCAGC-3’ |

| Cpl1 F218A Fwd | 5’- CAATGGCAGTGCGCCTTATAATA-3’ |

| Cpl1 F218A Rev | 5’- TTTCGTCTGAACCACCACCCCTT-3’ |

| Cpl1 Y238A Fwd | 5’- TAGTAAAGGAGCGTGCTTAACGA-3’ |

| Cpl1 Y238A Rev | 5’- TCGAAGTAGTACCACACACCACC-3’ |

| Cpl1 W210A:F218A Fwd | 5’- CAATGGCAGTGCGCCTTATAATAAATGGGAAAAAATC-3’ |

| Cpl1 W210A:F218A Rev | 5’- TTTCGTCTGAACGCCCACCCCTT-3’ |

| Cpl1 W210A:Y238A Fwd | 5’- CAAGGGGTGGGCGTTCAGACGAAAC-3’ |

| Cpl1 W210A:Y238A Rev | 5’- CTGTCTTGTTTCCACGTTC-3’ |

| Cpl1 F218A:Y238A Fwd | 5’- TAGTAAAGGAGCGTGCTTAACGAGCGAATG- 3’ |

| Cpl1 F218A:Y238A Rev | 5’- TCGAAGTAGTACCACACAC- 3’ |

| Cpl1 WFY Fwd | 5’- TAGTAAAGGAGCGTGCTTAACGAGCGAATG-3’ |

| Cpl1 WFY Rev | 5’- TCGAAGTAGTACCACACAC-3’ |

| Cpl1 WFY CBD Fwd | 5’- TAAGAAGGAGATATACCATGGGAACGTGGAAACAAGACAG-3’ |

| Cpl1 WFY CBD Rev | 5’- CAGCTTCCTTTCGGGCTTTGTTAATGGTGATGATGATGATGTG-3’ |

| Cpl1 DNP→AAA Fwd | 5’- GGCGAGTTTCACGAAAGAACCAGAC-3’ |

| Cpl1 DNP to AAA Rev | 5’- GCCGCTGCAAGCTCTCCGTTTGT-3’ |

| Cpl1 SFT→AAA Fwd | 5’- GGCGAAAGAACCAGACGGGCTT-3’ |

| Cpl1 SFT→AAA Rev | 5’- GCCGCTGGATTGTCTGCAAGCTC-3’ |

| Cpl1 KEP→AAA Fwd | 5’- GGCGGACGGGCTTATAACCGTAG-3’ |

| Cpl1 KEP→AAA Rev | 5’- GCCGCCGTGAAACTTGGATTGTCTG-3’ |

| Cpl1 DGL→AAA Fwd | 5’- GGCGATAACCGTAGCACATCATC-3’ |

| Cpl1 DGL→AAA Rev | 5’- GCCGCTGGTTCTTTCGTGAAACTTG-3’ |

| Cpl1 ITV→AAA Fwd | 5’- GGCGGCACATCATCATCATCACC-3’ |

| Cpl1 ITV→AAA Rev | 5’- GCCGCAAGCCCGTCTGGTTCTTT-3’ |

| Cpl1 F328A Fwd | 5’- CAATCCAAGTGCGACGAAAGAACCAGAC-3’ |

| Cpl1 F328A Rev | 5’- TCTGCAAGCTCTCCGTTT-3’ |

Protein Expression and Purification.

Overnight cultures of E. coli BL21 (DE3) containing the plasmid of interest were sub-cultured 1:100 into 1.5 L LB containing antibiotic for plasmid maintenance and grown at 37 °C in baffled flasks to an OD600 = 1. The LB was supplemented with either 100 μg/mL ampicillin for constructs using the pBAD24 vector or 50 μg/mL kanamycin for constructs using the pET28a vector. Expression was induced while cells were in mid-log phase with 0.25% arabinose overnight at 18 °C for constructs in pBAD24 or 10 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for those in the pET28a vector. Cells were harvested (5,000×g, 15 min, 4 °C), resuspended in 20 mL of lysis buffer (PBS, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.4), and disrupted by freeze–thawing (−80 to 4 °C). This was followed by sonication on ice (power level 6 and duty cycle 30%). Insoluble cell debris was centrifuged (12,000×g, 1 h, 4 °C), and the cell lysate containing the 6X-His-tagged protein was loaded onto Ni-NTA resin (HisPur Ni-NTA Resin, Thermo Scientific) in a gravity flow column and eluted in 4 mL fractions using an imidazole step gradient in PBS buffer (20 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, 250 mM, and 500 mM imidazole). Protein purity was analyzed on SDS-PAGE gel. Where further purification was necessary, samples were applied to a Sephacryl S-200 size exclusion column (Cytiva). Protein samples were pooled and concentrated using a protein concentrator with the appropriate molecular weight cutoff (Amicon Ultra 15 mL centrifugal filters, Millipore Sigma).

Microbiology and Lytic Assays.

Antimicrobial activity was quantified by means of colony forming unit (CFU) counting as previously described.74 Briefly, sterile protein at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL was mixed with 100 μL of stationary-phase S. pneumoniae in PBS in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, five 10-fold dilutions in PBS were made, and 10 μL from each dilution was plated on THY agar plates, air-dried, and placed in a 37 °C incubator overnight. The remaining CFUs were counted, and the data was reported as the log-fold killing compared to the untreated control. Each CFU counting assay was performed in triplicate on three separate days.

Analytical Size Exclusion.

Cpl-1 and its mutants were subjected to analytical size exclusion chromatography on a Superose 12 column (GE Healthcare) as previously described.16 The column was calibrated with size exclusion standards (Bio-Rad) and equilibrated with either PBS or PBS supplemented with choline chloride at indicated concentrations for two column volumes (CV) before loading protein sample. 500 μL of a 1.5 mg/mL protein sample was loaded onto the column for each run, and the sample was eluted for 1.5 CV. Alternatively, phosphocholine chloride calcium salt tetrahydrate was used in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4) with 150 mM NaCl because it was insoluble in PBS.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation.

Sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments were performed using a ProteomeLab Beckman XL-A with an absorbance optical system and a 4-hole An60-Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter). For SV, 380 μL protein in PBS, pH 7.4, and 400 μL buffer were loaded into the sample and reference sectors of the dual-sector charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces. The samples in PBS ± 50 mM choline chloride were equilibrated overnight at 20 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 50 krpm, and the absorbance data for 4.5–17.8 μM proteins were collected at 280 nm. Absorbance signal was monitored in a continuous mode with a step size of 0.003 cm and a single reading per step. Sedimentation coefficients were analyzed from SV profiles using the program SEDFIT.75 The continuous c(s) distributions were calculated assuming a direct sedimentation boundary model with maximum entry regularization at a confidence level of 1 standard deviation.

Fluorescence-Labeling of Proteins.

Purified proteins were reacted with the carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester of AlexaFluor-555 (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Unreacted dye was removed from labeled protein by application to a 5 mL HiTrap desalting column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with PBS.

Cell Wall Binding Assays and Fluorescence Microscopy.

An overnight culture of S. pneumoniae DCC1811 or S. pneumoniae R36A was centrifuged and mixed with the AlexaFluor-555 labeled Cpl-1 CWBD or the WFY Cpl-1 triple mutant CWBD and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The cells were centrifuged, washed in PBS, and then visualized by fluorescence microscopy with an exposure time of 200 ms. An Eclipse 80i epifluorescent microscope workstation (Nikon) with an X-Cite 120 illuminator (EXFO) and an Infinity 3 camera (Teledyne Lumenera) was used. Infinity Analyze 7 software was used for image acquisition and analysis.

Bioinformatics and Discovery of Novel Enzymes.

Recently, Fernandez-Ruiz et al. conducted a bioinformatics pipeline to identify novel endolysins from nearly 200,000 uncultured viruses, in which they discovered 2,628 putative endolysins.47 All putative endolysins were scanned, and 76 were identified that contained the consensus sequence (FxxEPDGLIT), with almost all occurring at the C-terminus (Table S1). Three proteins were picked at random for further study based on the type of CD they possessed and their percent identity to Cpl-1, Pal, and LytA. These three enzymes were synthesized (GeneArt), subcloned into pBAD24 vectors, expressed, and purified. They were then tested for formation of dimers in the presence of choline by analytical size exclusion chromatography as described above.

Statistical Analysis.

Experimental data are presented as means ± standard error of means. Student’s t tests were performed for the statistical analysis. P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Zvi Kelman for helpful discussions. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID R01AI168313 to D.C.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00627.

Bactericidal activity of Cpl-1 F328A against S. pneumoniae DCC1811 (Figure S1); 76 putative endolysins containing the C-terminal tail consensus sequence (Table S1) (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.2c00627

Contributor Information

Adit B. Alreja, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA; Biological Sciences Graduate Program - Molecular and Cellular Biology Concentration, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA

Sara B. Linden, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA

Harrison R. Lee, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA

Kinlin L. Chao, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA

Osnat Herzberg, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA; Department of Biochemistry and Chemistry, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA.

Daniel C. Nelson, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA; Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA

REFERENCES

- (1).Tacconelli E; Carrara E; Savoldi A; Harbarth S; Mendelson M; Monnet DL; Pulcini C; Kahlmeter G; Kluytmans J; Carmeli Y; Ouellette M; Outterson K; Patel J; Cavaleri M; Cox EM; Houchens CR; Grayson ML; Hansen P; Singh N; Theuretzbacher U; Magrini N; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis 2018, 18 (3), 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Durando P; Faust SN; Fletcher M; Krizova P; Torres A; Welte T Experience with pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (conjugated to CRM197 carrier protein) in children and adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect 2013, 19 (Suppl 1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).WHO Immunization. Vaccines and Biologicals. https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/pneumonia (accessed 7 March 2022).

- (4).CDC. Global Pneumococcal Disease and Vaccination 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/global.html (accessed 7 March 2022).

- (5).WHO. Pneumonia Fact Sheet, WHO, 11 Nov 2021. [Google Scholar]

- (6).WHO. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants and children under 5 years of age: WHO position paper, WHO, 22 Feb 2019; pp 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Shenoy AT; Orihuela CJ Anatomical site-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence determinants. Pneumonia 2016, 8, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Steel HC; Cockeran R; Anderson R; Feldman C Overview of community-acquired pneumonia and the role of inflammatory mechanisms in the immunopathogenesis of severe pneumococcal disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 490346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ganaie F; Saad JS; McGee L; van Tonder AJ; Bentley SD; Lo SW; Gladstone RA; Turner P; Keenan JD; Breiman RF; Nahm MH A New Pneumococcal Capsule Type, 10D, is the 100th Serotype and Has a Large cps Fragment from an Oral Streptococcus. mBio 2020, 11 (3), 937–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Butler JC; Hofman J; Cetron MS; Elliott JA; Facklam RR; Breiman RF The continued emergence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Pneumococcal Sentinel Surveillance System. J. Infect. Dis 1996, 174 (5), 986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Atlanta, GA, December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Song JY; Nahm MH; Moseley MA Clinical implications of pneumococcal serotypes: invasive disease potential, clinical presentations, and antibiotic resistance. J. Korean Med. Sci 2013, 28 (1), 4–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Doern GV; Richter SS; Miller A; Miller N; Rice C; Heilmann K; Beekmann S Antimicrobial resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: have we begun to turn the corner on resistance to certain antimicrobial classes? Clin. Infect. Dis 2005, 41 (2), 139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Cillóniz C; Garcia-Vidal C; Ceccato A; Torres A Antimicrobial Resistance Among Streptococcus pneumoniae. In Antimicrobial Resistance in the 21st Century (Emerging Infectious Diseases of the 21st Century); Fong IW, Shales D, Drlica K, Eds.; Springer, Cham, 2018; pp 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Veiga-Crespo P; Ageitos JM; Poza M; Villa TG Enzybiotics: a look to the future, recalling the past. J. Pharm. Sci 2007, 96 (8), 1917–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Nelson D; Schuch R; Chahales P; Zhu S; Fischetti VA PlyC: a multimeric bacteriophage lysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103 (28), 10765–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Fischetti VA Bacteriophage endolysins: a novel anti-infective to control Gram-positive pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol 2010, 300 (6), 357–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Fischetti VA Using phage lytic enzymes to control pathogenic bacteria. BMC Oral Health 2006, 6 (Suppl 1), S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Linden SB; Alreja AB; Nelson DC Application of bacteriophage-derived endolysins to combat streptococcal disease: current state and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2021, 68, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Roach DR; Donovan DM Antimicrobial bacteriophage-derived proteins and therapeutic applications. Bacteriophage 2015, 5 (3), e1062590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ajuebor J; McAuliffe O; O’Mahony J; Ross RP; Hill C; Coffey A Bacteriophage endolysins and their applications. Sci. Prog 2016, 99 (2), 183–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fischetti VA Bacteriophage lytic enzymes: novel anti-infectives. Trends Microbiol. 2005, 13 (10), 491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Loessner MJ Bacteriophage endolysins–current state of research and applications. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 2005, 8 (4), 480–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fischetti VA Bacteriophage lysins as effective antibacterials. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 2008, 11 (5), 393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Garcia P; Mendez E; Garcia E; Ronda C; Lopez R Biochemical characterization of a murein hydrolase induced by bacteriophage Dp-1 in Streptococcus pneumoniae: comparative study between bacteriophage-associated lysin and the host amidase. J. Bacteriol 1984, 159 (2), 793–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Garcia JL; Garcia E; Arraras A; Garcia P; Ronda C; Lopez R Cloning, purification, and biochemical characterization of the pneumococcal bacteriophage Cp-1 lysin. J. Virol 1987, 61 (8), 2573–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Loeffler JM; Nelson D; Fischetti VA Rapid killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a bacteriophage cell wall hydrolase. Science 2001, 294 (5549), 2170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).McCullers JA; Karlstrom A; Iverson AR; Loeffler JM; Fischetti VA Novel strategy to prevent otitis media caused by colonizing Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3 (3), e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Loeffler JM; Djurkovic S; Fischetti VA Phage lytic enzyme Cpl-1 as a novel antimicrobial for pneumococcal bacteremia. Infect. Immun 2003, 71 (11), 6199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Doehn JM; Fischer K; Reppe K; Gutbier B; Tschernig T; Hocke AC; Fischetti VA; Loffler J; Suttorp N; Hippenstiel S; Witzenrath M Delivery of the endolysin Cpl-1 by inhalation rescues mice with fatal pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2013, 68 (9), 2111–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Howard LV; Gooder H Specificity of the autolysin of Streptococcus (Diplococcus) pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol 1974, 117 (2), 796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Li Q; Cheng W; Morlot C; Bai XH; Jiang YL; Wang W; Roper DI; Vernet T; Dong YH; Chen Y; Zhou CZ Fulllength structure of the major autolysin LytA. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 2015, 71 (Pt 6), 1373–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Usobiaga P; Medrano FJ; Gasset M; Garcia JL; Saiz JL; Rivas G; Laynez J; Menendez M Structural organization of the major autolysin from Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem 1996, 271 (12), 6832–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fernandez-Tornero C; Garcia E; Lopez R; Gimenez-Gallego G; Romero A Two new crystal forms of the choline-binding domain of the major pneumococcal autolysin: insights into the dynamics of the active homodimer. J. Mol. Biol 2002, 321 (1), 163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Garcia JL; Diaz E; Romero A; Garcia P Carboxy-terminal deletion analysis of the major pneumococcal autolysin. J. Bacteriol 1994, 176 (13), 4066–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Varea J; Saiz JL; Lopez-Zumel C; Monterroso B; Medrano FJ; Arrondo JL; Iloro I; Laynez J; Garcia JL; Menendez M Do sequence repeats play an equivalent role in the choline-binding module of pneumococcal LytA amidase? J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275 (35), 26842–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Monterroso B; Saiz JL; Garcia P; Garcia JL; Menendez M Insights into the structure-function relationships of pneumococcal cell wall lysozymes, LytC and Cpl-1. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283 (42), 28618–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Varea J; Monterroso B; Saiz JL; Lopez-Zumel C; Garcia JL; Laynez J; Garcia P; Menendez M Structural and thermodynamic characterization of Pal, a phage natural chimeric lysin active against pneumococci. J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279 (42), 43697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Buey RM; Monterroso B; Menendez M; Diakun G; Chacon P; Hermoso JA; Diaz JF Insights into molecular plasticity of choline binding proteins (pneumococcal surface proteins) by SAXS. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 365 (2), 411–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gallego-Paramo C; Hernandez-Ortiz N; Buey RM; Rico-Lastres P; Garcia G; Diaz JF; Garcia P; Menendez M Structural and functional insights Into Skl and Pal endolysins, two cysteine-amidases with anti-pneumococcal activity. Dithiothreitol (DTT) effect on lytic activity. Front. Microbiol 2021, 12, 740914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Resch G; Moreillon P; Fischetti VA A stable phage lysin (Cpl-1) dimer with increased antipneumococcal activity and decreased plasma clearance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2011, 38 (6), 516–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hermoso JA; Monterroso B; Albert A; Galan B; Ahrazem O; Garcia P; Martinez-Ripoll M; Garcia JL; Menendez M Structural basis for selective recognition of pneumococcal cell wall by modular endolysin from phage Cp-1. Structure 2003, 11 (10), 1239–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Jumper J; Evans R; Pritzel A; Green T; Figurnov M; Ronneberger O; Tunyasuvunakool K; Bates R; Zidek A; Potapenko A; Bridgland A; Meyer C; Kohl SAA; Ballard AJ; Cowie A; Romera-Paredes B; Nikolov S; Jain R; Adler J; Back T; Petersen S; Reiman D; Clancy E; Zielinski M; Steinegger M; Pacholska M; Berghammer T; Bodenstein S; Silver D; Vinyals O; Senior AW; Kavukcuoglu K; Kohli P; Hassabis D Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596 (7873), 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Mirdita M; Schutze K; Moriwaki Y; Heo L; Ovchinnikov S; Steinegger M ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19 (6), 679–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Steinegger M; Soding J MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol 2017, 35 (11), 1026–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Fischer W Phosphocholine of pneumococcal teichoic acids: role in bacterial physiology and pneumococcal infection. Res. Microbiol 2000, 151 (6), 421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Fernandez-Ruiz I; Coutinho FH; Rodriguez-Valera F Thousands of novel endolysins discovered in uncultured phage genomes. Front. Microbiol 2018, 9, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Finn RD; Clements J; Eddy SR HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Web Server issue), W29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Potter SC; Luciani A; Eddy SR; Park Y; Lopez R; Finn RD HMMER web server: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (W1), W200–W204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Finn RD; Bateman A; Clements J; Coggill P; Eberhardt RY; Eddy SR; Heger A; Hetherington K; Holm L; Mistry J; Sonnhammer EL; Tate J; Punta M Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42 (Database issue), D222–D230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Mistry J; Chuguransky S; Williams L; Qureshi M; Salazar GA; Sonnhammer ELL; Tosatto SCE; Paladin L; Raj S; Richardson LJ; Finn RD; Bateman A Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (D1), D412–D419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Kikhney AG; Svergun DI A practical guide to small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) of flexible and intrinsically disordered proteins. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589 (19 Pt A), 2570–2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Ganguly J; Low LY; Kamal N; Saile E; Forsberg LS; Gutierrez-Sanchez G; Hoffmaster AR; Liddington R; Quinn CP; Carlson RW; Kannenberg EL The secondary cell wall polysaccharide of Bacillus anthracis provides the specific binding ligand for the C-terminal cell wall-binding domain of two phage endolysins, PlyL and PlyG. Glycobiology 2013, 23 (7), 820–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Mo KF; Li X; Li H; Low LY; Quinn CP; Boons GJ Endolysins of Bacillus anthracis bacteriophages recognize unique carbohydrate epitopes of vegetative cell wall polysaccharides with high affinity and selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (37), 15556–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Loessner MJ; Kramer K; Ebel F; Scherer S C-terminal domains of Listeria monocytogenes bacteriophage murein hydrolases determine specific recognition and high-affinity binding to bacterial cell wall carbohydrates. Mol. Microbiol 2002, 44 (2), 335–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Schmelcher M; Shabarova T; Eugster MR; Eichenseher F; Tchang VS; Banz M; Loessner MJ Rapid multiplex detection and differentiation of Listeria cells by use of fluorescent phage endolysin cell wall binding domains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2010, 76 (17), 5745–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Roig-Molina E; Sanchez-Angulo M; Seele J; Garcia-Asencio F; Nau R; Sanz JM; Maestro B Searching for Antipneumococcal Targets: Choline-Binding Modules as Phagocytosis Enhancers. ACS Infect. Dis 2020, 6 (5), 954–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Broendum SS; Williams DE; Hayes BK; Kraus F; Fodor J; Clifton BE; Geert Volbeda A; Codee JDC; Riley BT; Drinkwater N; Farrow KA; Tsyganov K; Heselpoth RD; Nelson DC; Jackson CJ; Buckle AM; McGowan S High avidity drives the interaction between the streptococcal C1 phage endolysin, PlyC, with the cell surface carbohydrates of Group A Streptococcus. Mol. Microbiol 2021, 116 (2), 397–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Perez-Dorado I; Gonzalez A; Morales M; Sanles R; Striker W; Vollmer W; Mobashery S; Garcia JL; Martinez-Ripoll M; Garcia P; Hermoso JA Insights into pneumococcal fratricide from the crystal structures of the modular killing factor LytC. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2010, 17 (5), 576–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Morzywolek A; Plotka M; Kaczorowska AK; Szadkowska M; Kozlowski LP; Wyrzykowski D; Makowska J; Waters JJ; Swift SM; Donovan DM; Kaczorowski T Novel lytic enzyme of prophage origin from Clostridium botulinum E3 strain Alaska E43 with bactericidal activity against clostridial cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2021, 22 (17), 9536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Dunne M; Leicht S; Krichel B; Mertens HD; Thompson A; Krijgsveld J; Svergun DI; Gomez-Torres N; Garde S; Uetrecht C; Narbad A; Mayer MJ; Meijers R Crystal structure of the CTP1L endolysin reveals how its activity is regulated by a secondary translation product. J. Biol. Chem 2016, 291 (10), 4882–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Proenca D; Velours C; Leandro C; Garcia M; Pimentel M; Sao-Jose C A two-component, multimeric endolysin encoded by a single gene. Mol. Microbiol 2015, 95 (5), 739–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Zhou B; Zhen X; Zhou H; Zhao F; Fan C; Perculija V; Tong Y; Mi Z; Ouyang S Structural and functional insights into a novel two-component endolysin encoded by a single gene in Enterococcus faecalis phage. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16 (3), e1008394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Catalao MJ; Gil F; Moniz-Pereira J; Pimentel M The endolysin-binding domain encompasses the N-terminal region of the mycobacteriophage Ms6 Gp1 chaperone. J. Bacteriol 2011, 193 (18), 5002–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Abaev I; Foster-Frey J; Korobova O; Shishkova N; Kiseleva N; Kopylov P; Pryamchuk S; Schmelcher M; Becker SC; Donovan DM Staphylococcal phage 2638A endolysin is lytic for Staphylococcus aureus and harbors an inter-lytic-domain secondary translational start site. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2013, 97 (8), 3449–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Pinto D; Goncalo R; Louro M; Silva MS; Hernandez G; Cordeiro TN; Cordeiro C; Sao-Jose C On the occurrence and multimerization of two-polypeptide phage endolysins encoded in single genes. Microbiol. Spectr 2022, 10 (4), No. e0103722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Garcia E; Garcia JL; Garcia P; Arraras A; Sanchez-Puelles JM; Lopez R Molecular evolution of lytic enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1988, 85 (3), 914–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Sao-Jose C Engineering of phage-derived lytic enzymes: Improving their potential as antimicrobials. Antibiotics (Basel) 2018, 7 (2), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Yang H; Gong Y; Zhang H; Etobayeva I; Miernikiewicz P; Luo D; Li X; Zhang X; Dabrowska K; Nelson DC; He J; Wei H ClyJ Is a novel pneumococcal chimeric lysin with a cysteine- and histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase catalytic domain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2019, 63 (4), e02043–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Yang H; Luo D; Etobayeva I; Li X; Gong Y; Wang S; Li Q; Xu P; Yin W; He J; Nelson DC; Wei H Linker editing of pneumococcal lysin ClyJ conveys improved bactericidal activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2020, 64 (2), e01610–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Luo D; Huang L; Gondil VS; Zhou W; Yang W; Jia M; Hu S; He J; Yang H; Wei H A choline-recognizing monomeric lysin, ClyJ-3m, shows elevated activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2020, 64 (12), 311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Sa-Leao R; Tomasz A; Sanches IS; Nunes S; Alves CR; Avo AB; Saldanha J; Kristinsson KG; de Lencastre H Genetic diversity and clonal patterns among antibiotic-susceptible and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizing children: day care centers as autonomous epidemiological units. J. Clin. Microbiol 2000, 38 (11), 4137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Avery OT; Macleod CM; McCarty M Studies on the Chemical Nature of the Substance Inducing Transformation of Pneumococcal Types: Induction of Transformation by a Desoxyribonucleic Acid Fraction Isolated from Pneumococcus Type Iii. J. Exp. Med 1944, 79 (2), 137–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Nelson DC; Schmelcher M; Rodriguez-Rubio L; Klumpp J; Pritchard DG; Dong S; Donovan DM Endolysins as antimicrobials. Adv. Virus Res 2012, 83, 299–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Brown PH; Schuck P Macromolecular size-and-shape distributions by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation. Biophys. J 2006, 90 (12), 4651–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.