Summary box.

There is an emerging awareness that governments must strike a fair balance between protecting and promoting public health on one side and individual human rights on the other.

Human rights could smoothly be integrated into the COVID-19 measures’ decision process.

Such integration will ask for human rights awareness, knowledge and accessibility.

Governments are responsible for fulfilling human rights, and thus also for introducing the right tools for decision-makers and implementers.

An easy to use human rights assessment as presented in this article could be an integral part of introducing and scaling back COVID-19 measures.

Introduction

States across the world employ far-reaching measures to handle the corona virus outbreak. Time and resources are limited, and there is immense pressure to introduce effective measures and to scale them back at the appropriate time. When making these decisions, many states strive to uphold acceptable governance standards.

Universal human rights provide limits for the exercise of state authority. The human rights framework is complex and not readily accessible to anyone not specialised in human rights law. However, it is paramount that human rights are respected in the current situation. This article provides a basic how-to guide for the assessment and operationalisation of human rights for COVID-19 measures.

Human rights treaties by organisations such as the United Nations, the African Union, the Organization of American States and the Council of Europe build upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and provide well established and accepted legal boundaries for use of state power, applicable of course also when implementing virus mitigation measures.1 Human rights are legally binding on State Parties through international treaties and domestic legislation. State institutions and individuals acting on behalf of the state have a duty to respect, protect and fulfil human rights. This includes a parliament passing legislation, a public hospital deciding who should receive healthcare or a medical doctor providing care in a public institution for the elderly.

Core human rights norms

First and foremost is the duty to respect, protect and fulfil the right to life, including basic healthcare. States that do not implement measures against communicable diseases, like disease control, will be in violation of this human rights duty. The same is the case for access to water, sanitation and hygiene, which are necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19.2 States must balance their use of resources and the COVID-19 measures with that of addressing other health issues. Patients with cancer, malaria, diabetes, tuberculosis or cardiovascular diseases have the same level of human rights protection as patients suffering from COVID-19. While the room for manoeuvre is larger in high-income countries than in low-income and middle-income countries, the human rights guidance will be the same.3 4

While promoting the right to life and health, states must align these measures with other human rights obligations, especially civil and political rights. The right to privacy, freedom of movement and other fundamental human rights have to be respected as far as possible.

Civil and political rights can be limited by state authorities.5 Three requirements must be met: the measure must (1) be provided by law; (2) serve a legitimate aim, for instance protection of health and safety; and (3) be necessary in a democratic society. In addition, the measure must be proportional compared with the aims, it must be effective, as unintrusive as possible and mitigating actions must be considered. A ‘pressing social need’ and ‘relevant and sufficient’ reasons are often mentioned as conditions.5

Discrimination constitutes another threshold. Discrimination in this regard is unjust differential treatment based on gender, ethnicity, national origin, religion, age or other personal characteristics, resulting in better or worse treatment of specific groups compared with the population at large. There is emerging evidence that ethnic minorities run a larger risk of COVID-19 mortality, which may justify proactive measures for specific groups in society.6

Prioritisation

As COVID-19 puts a strain on the healthcare system, prioritisation becomes increasingly challenging, as evidenced for instance in Italy.7 When two patients’ lives can be saved by the use of a ventilator, and you only have one ventilator available, who will get it? And should the neonatal intensive care unit or the infectious disease unit be given priority to your limited supply of personal protective equipment? Should you direct sparse medical resources towards fighting COVID-19 or measles outbreaks, as in Democratic Republic in Congo? Medical personnel are trained in making such decisions, but the increased strain of a pandemic makes the prioritisations more difficult. Access to information and research from similar situations, adapted to the local context, are crucial.8 States apply different prioritisation criteria, and applying the criteria during a pandemic may cause moral distress. Nevertheless, a choice needs to be made as to who gets the limited resources.

The human rights guidance is that such decisions should be based on accessible information and medical knowledge; the reasons for the prioritisation must be relevant and sufficient; and the balancing of interests should be done with due respect to equality and non-discrimination. Similar situations arise inter alia with suspension of immunisation programmes, rationing of medicines, postponement of elective surgeries and access to palliative care.

Tracing and surveillance

Several countries including South Korea, Singapore and Israel have an effort to gain better overview and thus better informed measures, instigated location and contact tracing of confirmed cases with the use of intelligence tracking tools, mobile phone locations, CCTV footage and/or credit card transactions.9 Potentially intimidating details about people’s lives and whereabouts have been revealed in the process, raising privacy concerns.10 Therefore, several states have been hesitant to employ such measures, leading to a lack of disease outbreak data and lack of contact notification.

Recognising the need, private companies such as Google and Apple have developed an interface to support such apps.9 Geolocation data are notoriously difficult to anonymise, and there is a risk that individuals may be identified, as some were in South Korea.10 This poses a risk for stigma and discrimination. Strict purpose limitation must be upheld, ensuring that the data are not exploited by states for other purposes than virus tracing, for instance law enforcement or immigration. Only data strictly necessary should be collected, and the data must be deleted once the purpose is achieved. However, temporary use of an app to trace the outbreak and contacts is permissible from a human rights perspective if the state considers the measure effective, proportional and necessary; ensures a legal basis and adequate safeguards for the measure; and implements the measure as unintrusively with regard to the right to privacy as feasible.

Quarantine, isolation and travel bans

To limit the outbreak and avoid undue pressure on the healthcare system, close to every country in the world have imposed restrictions on the freedom of movement through quarantine, isolation and travel bans. In China, 760 million people were in residential lockdown as a measure to contain the virus.11 In poorer countries, such measures are not—and cannot be—implemented with the same scrutiny.12

Such limitations can be justifiable, depending on the context: quarantine might be relevant for big cities but not so in rural areas, and isolation might have unproportionally negative health effects for some individuals.13 In low-income countries, the population is younger, the healthcare system already overwhelmed and the financial consequences of a lockdown may be catastrophical.4 12 Realism must be taken into account: will the population at large respect the measures or will the measures de facto be ineffective? Are there less intrusive options available? When limiting the freedom of movement, the measures cannot be broader than necessary, they cannot be discriminatory and those affected must have a right to a judicial remedy.

Adapting measures to the current situation

While introducing measures to fight the pandemic asks for a human rights assessment, state authorities also have an obligation to adjust the measures to the current situation. Even if quarantine and the use of geolocation data are acceptable measures in the early development of the pandemic, positive changes in the morbidity and mortality rates imply that such invasive measures must be customised accordingly or terminated. Hence, continuous, transparent and knowledge-based evaluation is needed.

The specific human rights norms, such as on the right to life and the freedom of movement, are pieces in an interrelated, interdependent and indivisible system. One implication of this is that rights and freedoms need to be balanced in a holistic perspective: if electronic tracing limiting the right to privacy allows for less-restrictive limitations to the freedom of movement, the measure might be acceptable in a human rights perspective. Another implication is that the evidence-based decisions regarding COVID-19 measures must include a wider spectre of arguments than the ones related to public health only. The overall aim is a proportionate response limited to strictly necessary measures.

The existing global framework for sustainable measures

Legal and ethical norms go hand in hand: similar norms are found in guidelines for health personnel, such as the Physician’s Pledge, and in governing public health documents, for instance the International Health Regulations.14 15

Human rights are not toothless and vague recommendations, but hard law. National courts will apply human rights law when deciding on cases, while international courts will build on human rights as part of the international law regime. In addition, there will be institutions with political powers, such as ombudsmen on the domestic level and human rights treaty bodies and organs (like the UN General Assembly and the UN Human Rights Council) on the international level giving recommendations and comments. On top of this, there are numerous civil society organisations engaged in human rights issues, both on the domestic and the international plane. Governments that do not respect and protect human rights, might thus be targeted not only by lawsuits but also by political pressure and naming and shaming from national and international bodies and organisations.

Conclusion

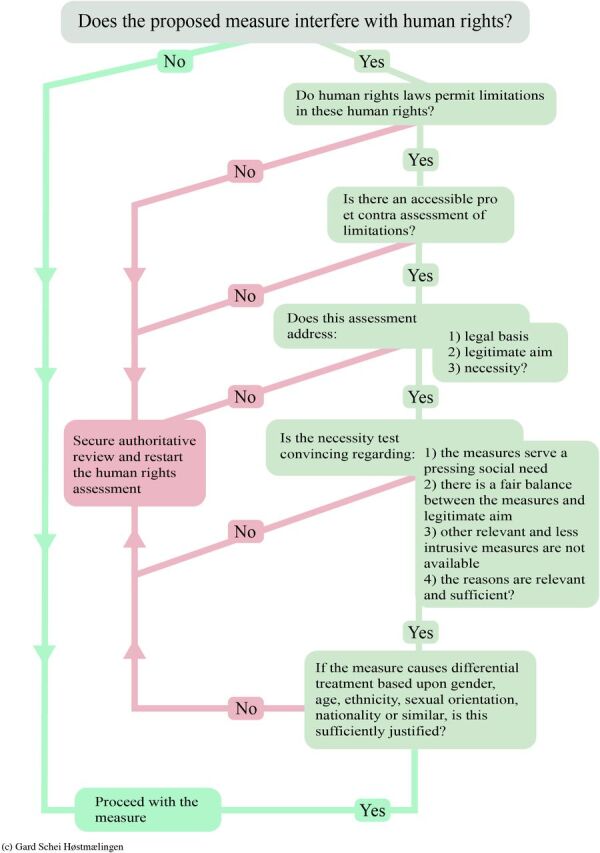

The challenge might not be willingness, but knowing how to apply human rights to the assessment of the COVID-19 measures. Figure 1 presents a tool to assess and navigate the interplay between the paradigmatic types of disease control discussed here and the protection and promotion of human rights of affected individuals. By following the steps in figure 1 and using the explanation above as a guide, a basic human rights assessment of the measures is achieved.

Figure 1.

Decision tree for disease control and human rights assessment.

COVID-19 measures that respect, protect and fulfil human rights are the only sustainable measures in the long run, from a legal, democratic and medical point of view.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @HeidiBBentzen

Collaborators: Gard Schei Hostmaelingen

Contributors: Both authors have contributed on an equal basis to the planning, conduct and reporting of the work.

Funding: NH receives funding from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the Clinical Effectiveness Research Group. HBB receives funding from The Research Council of Norway, project 'Legal Regulation of Information Processing relating to Personalised Cancer Medicine', grant number 238999, and from NordForsk, project 'Governance of Health Data in Cyberspace', grant number 81105.

Disclaimer: Neither of the funders had any role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Høstmælingen receives funding from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the Clinical Effectiveness Research Group. Neither of the funders had any role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Høstmælingen declares that he has no conflict of interest. Bentzen receives funding from The Research Council of Norway, project 'Legal Regulation of Information Processing relating to Personalized Cancer Medicine', grant number 238999, and from NordForsk, project 'Governance of Health Data in Cyberspace', grant number 81105. Neither of the funders had any role in study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Bentzen declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: There are no data in this work.

References

- 1.The Bill of Human Rights: UN General Assembly, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 10 December 1948, 217 A (III), UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations Treaty Series, vol. 993, p. 3, and UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171.

- 2. Singh L, Singh NS, Nezafat Maldonado B, et al. What does ‘leave no one behind’ mean for humanitarian crises-affected populations in the COVID-19 pandemic? BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002540. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inter-Agency Standing Committee . Interim guidance on public health and social measures for COVID-10 preparedness and response operations in low capacity and humanitarian settings, 2020. Available: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/health/interim-guidance-public-health-and-social-measures-covid-19-preparedness-and-response-0

- 4. Mehtar S, Preiser W, Lakhe NA, et al. Limiting the spread of COVID-19 in Africa: one size mitigation strategies do not fit all countries. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e881–3. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30212-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Siracusa principles on the limitation and Derogation provisions in the International covenant on civil and political rights, Annex, UN doc E/CN.4/1985/4.

- 6. Kirby T. Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:547–8. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30228-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy - Ethics, Logistics, and Therapeutics on the Epidemic's Front Line. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1873–5. 10.1056/NEJMp2005492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), African Union Commission . Recommendations for stepwise response to COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://africacdc.org/download/recommendations-for-stepwise-response-to-covid-19/

- 9. Morley J, Cowls J, Taddeo M, et al. Ethical guidelines for COVID-19 tracing apps. Nature 2020;582:29–31. 10.1038/d41586-020-01578-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zastrow M. South Korea is reporting intimate details of COVID-19 cases: has it helped? Nature 2020;18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00740-y. [Epub ahead of print: 18 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cyranoski D. What China's coronavirus response can teach the rest of the world. Nature 2020;579:479–80. 10.1038/d41586-020-00741-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnett-Howell Z, Mobarak AM. Should low-income countries impose the same social distancing guidelines as Europe and North America to halt the spread of COVID-19? Yale university, 2020. Available: https://som.yale.edu/sites/default/files/mushifiq-howell-v2.pdf

- 13. Glassman A, Chalkidou K, Sullivan R. Does one size fit all? Realistic alternatives for COVID-19 response in low-income countries. Center for Global Development, 2020. Available: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/does-one-size-fit-all-realistic-alternatives-covid-19-response-low-income-countries

- 14. World Medical Association . Declaration of Geneva, 2017. Available: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/ [Accessed Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. International Health Regulations . Adopted by the world Health organization in Geneva 23 may 2005, entry into force 15 June 2007, UNTS 2509 (P 79), 2005. Available: https://www.who.int/ihr/publications/978924150496/en/ [Accessed Apr 2020].